- Division of Public Health, ICMR-Regional Medical Research Centre, Bhubaneswar, India

Introduction: Cataracts are the leading cause of blindness among older people, but they can be treated with corrective surgery. India boasts the oldest blindness control programme in the world. We aimed to assess the prevalence of cataract surgery, and we compared the determinants of undergoing cataract surgery and identified the unmet needs for cataract surgery among older adults in India.

Methods: We included 52,380 individuals aged ≥50 years from the Longitudinal Ageing Study in India, wave-1. The primary outcome measures of our study were the prevalence of cataract surgery and the unmet need for cataract surgery. Multivariate analysis was executed to investigate the association between socio-demographic variables and outcomes, expressing the results as adjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results: The overall prevalence of cataracts was 14.85%. The coverage of cataract surgery was 76.95%, with 23% having unmet needs for cataract surgery. Notably, cataract surgery coverage was higher at 78.30% (95% CI: 76.88–79.48) among participants aged 66–80 years, while the percentage of those who did not undergo cataract surgery was higher at 24.62% (95% CI: 23.09–26.20) among participants aged 50–60 years. The most deprived group had a higher odds ratio [adjusted odds ratio: 1.20 (95% CI: 1.00–1.44)] (p < 0.05) of having unmet needs for cataract surgery.

Conclusions: There is a considerable burden of age-related cataracts in India. While the coverage of cataract surgery is high, the unmet need for cataract surgery cannot be overlooked. The existing blindness control programme has contributed significantly to increasing the coverage of cataract surgery, but it still needs to be strengthened, especially to reach the most deprived sections of society.

Introduction

Vision is among the most vital senses of humans, which utilizes over 30% of the brain’s capacity for processing information (1). Consequently, the fear of vision loss ranks the highest among all possible disabilities (1, 2). Cataracts are the leading cause of curable blindness worldwide (3). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), as of 20121, there are an estimated 2.2 billion individuals living with near or distant visual impairment (4). Approximately 1 billion people suffer from moderate or severe distance visual impairment, with almost 94 million diagnosed with cataracts (4). Cataracts were responsible for 45% of global blindness in 2020 (4–6). In addition, cataracts are recognized as the second most common cause of moderate and severe vision impairment (MSVI) (7).

Cataracts may be congenital, secondary to trauma, or drug-induced, but the most common presentation is as age-related disease (3). Age-associated cataracts are mainly caused by the opacification of the lens due to oxidative damage (3). This form of blindness is associated with considerable disability and excess mortality, hampering the social and economic growth of the individual (8). Surgery is the most successful and least complicated treatment, leading to direct improvements in visual acuity and activities of daily living (ADL) along with decreased cataract-related morbidity and mortality (3). However, the distribution of cataracts is grossly uneven in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) compared to high-income countries (HICs), with LMICs contributing 90% and HICs contributing 50% of all blindness (1, 8). LMICs contribute 90% of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) due to cataracts, thus creating gross inequalities in the burden of cataracts (8).

More than 90% of individuals with visual impairment caused by cataracts live in LMICs (9–13). The prevalence of cataracts is increasing among LMICs, attributed to their rapid ageing population (8). For instance, data from India's 2011 census indicated that the proportion of individuals aged 60 years and above was around 8.6% of the total population (14). This percentage has been consistently on the rise due to declining birth rates and advancements in healthcare, contributing to extended life expectancy. Projections suggest that this demographics will further increase to 19.5% of the total population, reaching approximately 319 million by 2050 (15). More than half of the people experiencing blindness due to cataracts remain unreported due to lack of medical facilities in the vicinity, higher cost, gender bias, lack of awareness about available treatments, and fear of surgery (15). Effects of cataracts are not only confined to visual deficit but also to functional and psychological disability, which significantly reduces health-related quality of life (HRQoL) (16). India was the first country to start a blindness control programme in the world with the National Programme for Control of Blindness and Visual Impairment in 1976. The programme aimed to reduce blindness and visual impairment through various interventions, including medical treatment, surgeries, and awareness campaigns. It is worth noting that the specific types of cataract surgeries performed under this programme include manual small incision cataract surgery (MSICS) and phacoemulsification. According to the National Blind Visual Impairment Survey 2019, the coverage for cataract surgery among blind individuals and visually impaired people was 93.2% and 74.0% in India, respectively (17). As India has one of the oldest blindness control programmes, it is pertinent to determine the factors associated with undergoing cataract surgery and compare them with those who did not opt for corrective surgery. The evidence generated can further help reduce the unmet needs for cataract surgery by informing existing programmes and guiding future policies. Hence, this study was conducted with the objective of estimating the prevalence of cataracts among adults aged ≥50 years in India using data from the Longitudinal Aging Study in India (LASI), wave-1. Further, we compared the determinants of undergoing cataract surgery and the unmet needs for cataract surgery among older adults in India.

Methods

Overview of data

This study used data from LASI, wave-1, conducted from April 2017 to December 2018. LASI is a nationally representative study conducted in collaboration with the Harvard T.S. Chan School of Public Health, the International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS), and the University of Southern California under the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. This study was implemented to understand the social and health challenges faced by older adults aged ≥45 years in India. Data were collected from all the states and union territories except Sikkim. Detailed information on LASI can be obtained from the website of the International Institute of Population Sciences, Mumbai (18).

Sample size and participants

A total of 72,250 individuals aged ≥45 years and their spouses (irrespective of age) were surveyed by LASI. We excluded participants aged <50 years in the purview of our objective. The final sample size comprised 52,380 individuals aged ≥50 years, who were included in the present study.

Independent variables

The variables for the present study were derived from the individual survey schedule of LASI. We used variables from the socio-demographic section, such as age, sex, residence, caste, education, occupation, marital status, wealth index, and regions of India. Age was classified into three groups: 50–65, 66–80, and ≥80 years. The sex of the participants was reported as male or female based on the observation. The residence was classified as rural and urban. The caste of participants was categorized into four groups, i.e., scheduled caste, scheduled tribe, other backward classes, and “others,” which included merging responses such as “none of them” and “no caste/tribe.” Education status was grouped as follows: no formal education, primary (less than primary, primary. and middle school), secondary (secondary and higher secondary), and higher (diploma, graduate, postgraduate, and professional degree). Occupation was stratified into three categories: never worked, currently working, and currently not working; this classification was based on questions “Have you ever worked for at least 3 months during your lifetime?” and “Are you currently working?”. Marital status was classified into two groups: “living with a partner” for those who responded being currently married or in a live-in relationship, while those who indicated being “widowed, divorced, separated, deserted, or never married” were grouped as “living without a partner.” The wealth index was grouped as most deprived (2–4), and the most affluent based on the monthly per capita expenditure (MPCE) (19). The region was categorized into six zones: east, west, south, north, northeast, and central.

Outcome variables

The primary outcome measures of the study were the participants who had cataract surgery and those who did not. In the LASI individual questionnaire, the participants were asked, “Have you ever been diagnosed with any eye or vision problem or condition, including ordinary near sightedness or farsightedness?”; those who responded “yes” were further asked, “With which problem or condition were you diagnosed?”. Participants who self-reported “cataract” were considered to have the condition. They were then asked, “Have you ever undergone any treatment or corrective surgery for an eye problem or condition?”; those who responded “yes” and also mentioned the type of surgery were considered as having undergone surgery for cataracts. Those who responded “no” were considered as not having undergone cataract surgery (Figure 1).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using STATA version 16.0 (STATA Corp., TX, USA). Mean and standard deviation were used to report continuous variables such as age. Frequency and proportion (%) were tabulated for all socio-demographic variables alongside the outcome variable, i.e., cataract surgery. All weighted proportions were reported along with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) as a measure of uncertainty. We used binary logistic regression to assess the strength of association (odds ratio, OR) between various socio-demographic characteristics and the outcome variables. The variables with p-values less than 0.05 were considered significant and further included in the multivariable logistic regression model. This association was expressed as an adjusted odds ratio (AOR) with a 95% CI. Survey weights were considered in the analysis to compensate for complex survey designs. The variance inflation factor (VIF) was calculated to observe multicollinearity in the regression models.

Ethical considerations

Because this study is a secondary analysis of data collected from LASI, it does not require any ethical approval. The original LASI study obtained ethics clearance from IIPS, Mumbai and the Indian Council of Medical Research, New Delhi. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their participation in the original LASI study.

Results

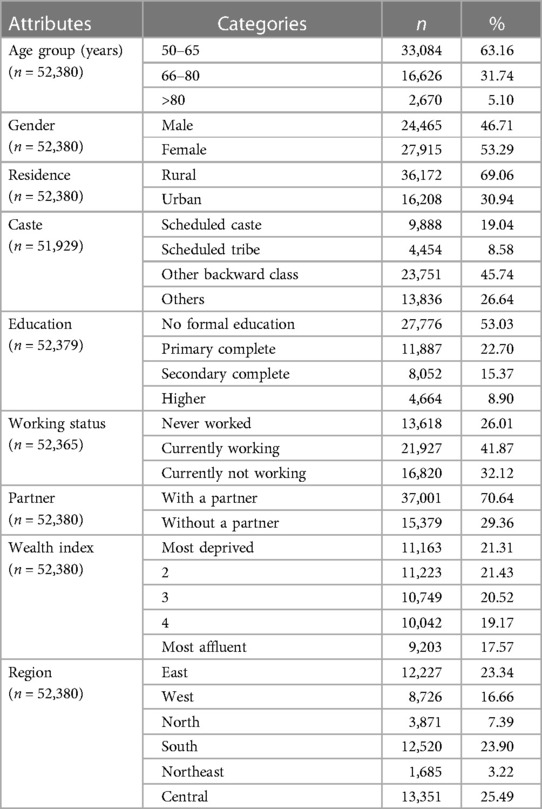

The average age of the participants was 63.4 ± 9.57 years, ranging from 50 to 116 years. Most participants (63.16%) belonged to the 50–65 year category. Almost half of the participants (53.29%) were women. Almost two-thirds of the population resided in rural areas. The detailed socio-demographic characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1. The gender-wise stratified socio-demographic characteristics of the study population are presented in Supplementary Table S1.

Prevalence of cataracts and cataract surgery

The overall prevalence of cataracts among the study participants was 14.85%. Among those with cataracts, 76.95% had undergone corrective surgery, while 23% had not undergone surgery.

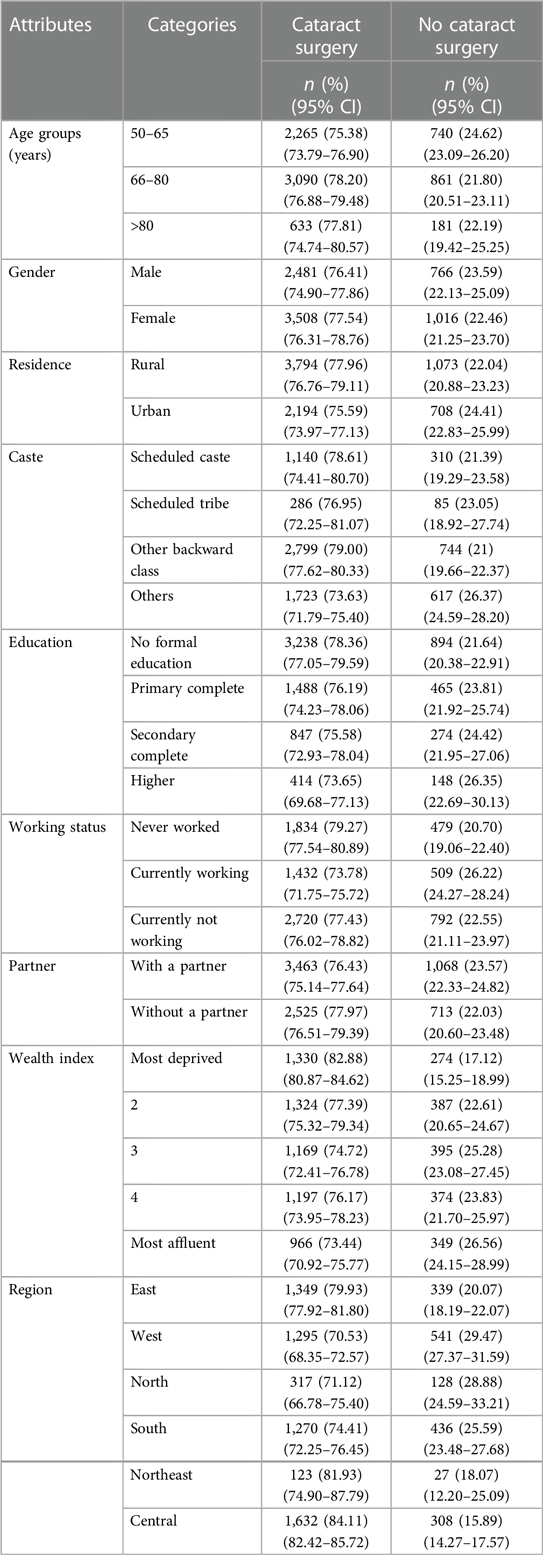

Table 2 presents the distribution of participants who underwent cataract surgery and those who did not across various socio-demographic characteristics. The coverage of cataract surgery was higher (78.30%, 95% CI: 76.88–79.48) among participants aged 66–80 years, whereas younger participants aged 50–65 years had a higher proportion (24.62%, 95% CI: 23.09–26.20) of not undergoing corrective surgery. A higher (77.54%, 95% CI: 76.31–78.76) number of women had cataract surgery compared to men, while cataract surgery was less preferred (23.59%, 95% CI: 22.13–25.09) by men. Participants residing in rural areas had a higher coverage of (77.96%, 95% CI: 76.76–79.11) cataract surgery, whereas those in urban areas had a higher unmet need for cataract surgery. The highest unmet need for cataract surgery was observed among participants with the highest level of education (26.35%, 95% CI: 22.69–30.13), while respondents with no formal education (78.36%, 95% CI: 77.05–79.59) had undergone more cataract surgeries. The coverage for cataract surgery decreased with an increase in wealth, i.e., the most deprived group (82.88%, 95% CI: 80.87–84.62) had the highest number of cataract surgeries, while this group had the lowest (17.12%, 95% CI: 15.25–18.99) unmet need of cataract surgery. The prevalence of cataract surgery was higher in the central region (84.11%, 95% CI: 82.42–85.72), while the west (29.47%, 95% CI: 27.37–31.59) region had more unmet need for cataract surgery. The gender-wise stratified distribution of participants who underwent cataract surgery across various socio-demographic characteristics is presented in Supplementary Table S2.

Table 2. Distribution of participants who had cataract surgery and those who did not across various socio-demographic attributes.

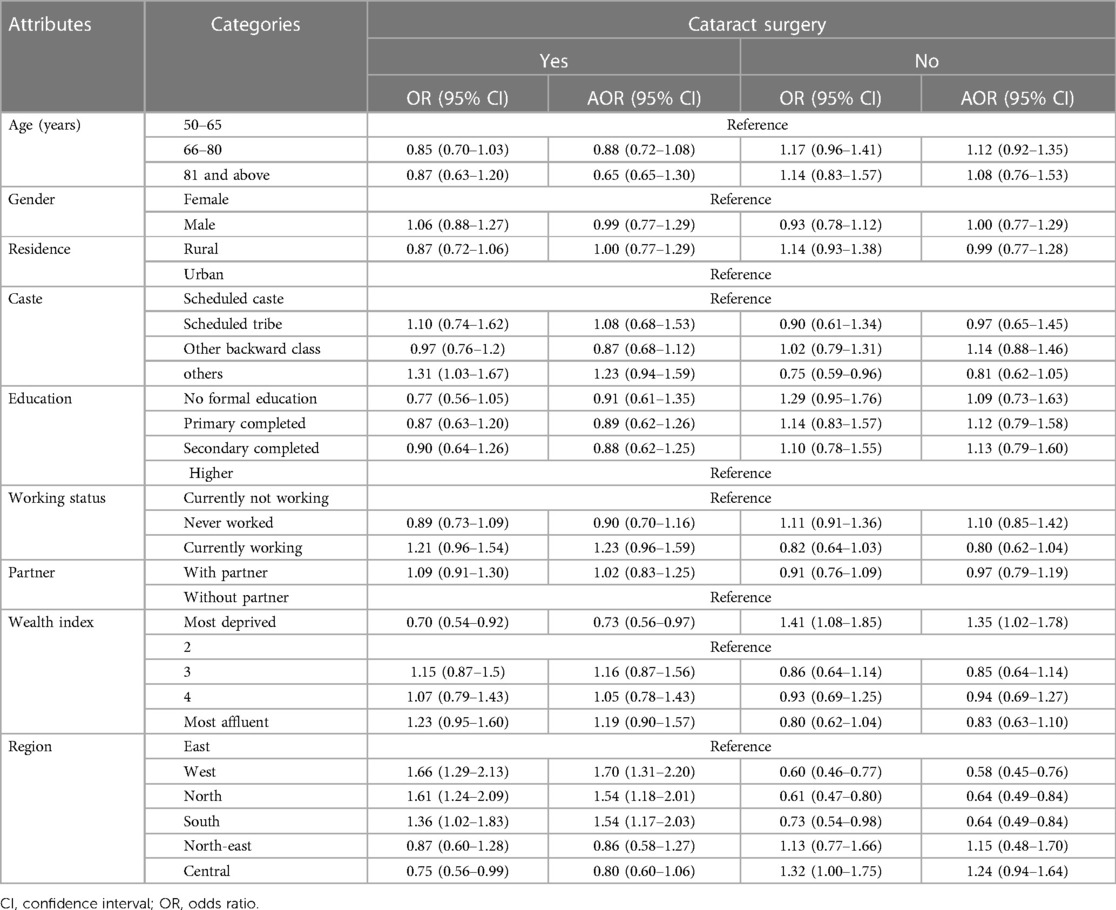

Table 3 presents the association of various socio-demographic characteristics with outcome variables, i.e., underwent cataract surgery and did not undergo cataract surgery. The univariable association showed that other caste (OR: 1.31, 1.03–1.67) and region were associated with having cataract surgery, whereas being in the most deprived group (OR: 1.42, 1.08–1.85) had a significant association with not undergoing cataract surgery. The multivariable regression model revealed that west (AOR: 1.70, 1.31–2.20), north (AOR: 1.54, 1.18–2.01), and south (AOR: 1.54, 1.17–2.03) regions were significantly associated with having cataract surgery. The determinant of not undergoing cataract surgery was being from the most deprived group (AOR: 1.35, 1.02–1.78). However, we did not find any association between different age groups, gender, residence, education, working status, and partner status in both univariable and multivariable analyses. We observed a VIF of 1.3, indicating that there was no multicollinearity in the existing regression model. The detailed VIF value for each of the variables is mentioned in Supplementary Table S3.

Table 3. Association between various socio-demographic attributes and cataract surgery done and not done.

Discussion

People aged 50 years and above represent around 13% of the total Indian population (14). This study provides novel insights into the prevalence of cataracts, coverage of cataract surgery, and unmet needs among a nationally representative sample of participants aged 50 years and above, which is important for the programme. We observed a high coverage of cataract surgery and a lower unmet need among the study participants.

Age-related cataracts are the leading cause of visual impairment and blindness, requiring timely intervention in the form of surgery (19). Our analysis reveals that participants aged 66–80 years had a higher prevalence of cataract surgery, followed by respondents aged >80 years. Our findings are consistent with the results of a similar study conducted among a representative Finnish population, which showed a relatively higher coverage of cataract surgery with increasing age (20). The proportion of unmet surgical need, however, was greater (39.1%) in previous geriatric population studies carried out by Wasekar and Lavangare in Mumbai and Vimalraj et al. in Kerala (21, 22). Moreover, shorter operating times, availability of more efficient anaesthesia, and a trend of daycare surgery have made cataract surgery a minor surgical procedure. Nonetheless, we observed that participants aged 50–65 years had the highest unmet needs for cataract surgery. A probable reason for this could be that people in this age group do not seek medical intervention until the disease progresses to an advanced stage. Although there were variations in the coverage of cataract surgery and unmet needs, no significant difference was observed between the age groups in both categories. This reflects the awareness among the masses, which has been a cumulative effect of the ongoing blindness control programme.

We observed that women had a higher coverage and lower unmet needs for cataract surgery. However, our findings contradict previous reports that show a lower coverage of cataract surgery among women (20–25). Nonetheless, our findings do not show a significant association between gender and outcome variables. Interestingly, no significant association was observed across urban and rural residents in accessing cataract surgery. In addition, contrary to prior studies, we found that rural residents had higher coverage and fewer unmet needs for cataract surgery than urban residents (26). However, multiple barriers contribute to urban–rural disparities in accessing healthcare facilities, including lack of financial resources, availability of healthcare setups, geographical location, unavailability of human resources, and civic amenities (15, 27). Still, a higher coverage indicates the strength of India's existing National Programme for Control of Blindness, which aims to prevent visual disability by providing free camps with free diagnostics and treatment services for cataract surgery. The various steps taken to reduce the burden of unmet need for cataract surgery include organization of mass surgery camps and awareness campaigns through various Information, Education, and Communication (IEC) activities in the community. In addition, the decentralization of government healthcare facilities, along with recent efforts to strengthen primary care by establishing Health and Wellness Centres, has helped in reducing this disparity (27). Similar findings were reported by Nathenetel et al. and Madaki et al. in Nigeria, where cataract surgery coverage showed a slight improvement (28, 29).

Individuals with no formal education and those who never worked had a higher coverage of cataract surgery. This further strengthens our notion that the existing programme has been successful in reaching each stratum of society. However, we observed a significant association between unmet needs for cataract surgery and the most deprived quintile. This is consistent with the findings of another study, which showed a higher risk of developing cataracts among the most deprived people (20). This might be due to a lack of awareness, inability to pay, or other socio-cultural factors, which further need to be explored. To achieve the global WHO target of increasing coverage of cataract surgery by 30% by 2030 and achieving universal health coverage, the most disadvantaged group must also have egalitarian access to healthcare facilities (25).

Participants belonging to the west, north, and south regions were significantly associated with having cataract surgery, while no significant association for unmet needs for cataract surgery was observed. This points towards replicating the best practices adopted by these regions in other regions to achieve zero blindness. In addition, socio-cultural factors of patients, their health systems, and awareness play an important role in this uptake, which needs to be explored further. Moreover, a probable reason for the central and north-eastern zones to have fewer cataract surgeries may be due to disparities in health infrastructure, geographic remoteness, and differences among the participants studied, which can also impede access challenges (31, 32). Moreover, health-seeking behaviour also varies between the regions, which could also be a probable reason for this difference (33). An Iranian study also found that cataract surgery coverage is low due to low cost and other resources (30).

Implications for policy and practice

Our study shows a high coverage of corrective surgery for cataracts, reflecting the strength of our existing blindness control programme. However, to achieve the goals of VISION-2020, we need to focus on the most deprived strata of society by creating awareness among them regarding the importance of undergoing surgery. In addition, there is a need to build trust in publicly funded camps by assuring them of the quality of care during surgery and their safety. IEC activities and camps should aim for zero blindness. Middle-aged adults should be motivated to undergo surgery when advised. Regional differences should be addressed by adopting the best practices from regions or states that are performing well. This provides actionable guidance for shaping future programme strategies, emphasizing the importance of equitable access, awareness campaigns, early intervention, and replicating successful practices. Addressing regional disparities and focusing on the most deprived groups are keys to achieving the goals of initiatives like VISION-2020 and realizing universal health coverage.

Strengths and limitations

A major strength of this study is the use of a large nationally representative sample, making it the first study to generate nationwide evidence on the coverage of cataract surgery. However, our study was limited by self-reported cataract diagnosis, which might have undermined the true prevalence, with answers potentially subject to recall bias. Also, cataract diagnosis alone as a measure of unmet needs might overstate the actual surgical necessity as many cataracts may not require surgery immediately. However, assessing the stage of cataracts was beyond the scope of this study as adequate, pertinent data were not available. Given the fact that some cataracts may not require surgery but can proceed to an advanced stage, in the absence of data, our operational definition of “unmet need” may be the best estimate, although future studies should employ more refined clinical criteria to better assess the urgency and appropriateness of surgical intervention, ensuring a more accurate depiction of true unmet need. In addition, our study was also limited by the lack of a clear definition of the type of cataract surgery, as relevant data were not available. Hence, this study encompasses cataract surgery as any type of cataract surgery, such as MSICS or phacoemulsification.

Conclusion

Although there is a considerable burden of age-related cataracts in India, the coverage of cataract surgery is high. Nonetheless, the unmet needs for cataract surgery cannot be overlooked. The existing blindness control programme has contributed significantly to increasing the coverage of cataract surgery, but it still needs to be strengthened, especially to reach the most deprived sections of society. In addition, efforts to increase awareness should be continued, and regional differences should be managed by adopting the best practices of areas with higher coverage of corrective surgery.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in https://g2aging.org/?section=overviews&study=lasi.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by ICMR, New Delhi and IIPS, Mumbai. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

SD: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft. AS: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – original draft. SK: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Supervision, Writing – original draft. SP: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The authors declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Longitudinal Ageing Study in India (LASI) for assembling and publishing accurate, nationally representative data on a range of health, biomarkers, and healthcare utilization indicators for the population aged 45 years and older. The authors are also grateful to LASI's project partners, the International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS), the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health (HSPH), and the University of Southern California (USC).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frhs.2024.1365485/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Cursiefen C, Cordeiro F, Cunha-Vaz J, Wheeler-Schilling T, Scholl HPN. Unmet needs in ophthalmology: a European Vision Institute-consensus roadmap 2019–2025. Ophthalmic Res. (2019) 62(3):123–33. doi: 10.1159/000501374

2. Scott AW, Bressler NM, Ffolkes S, Wittenborn JS, Jorkasky J. Public attitudes about eye and vision health. JAMA Ophthalmol. (2016) 134(10):1111–8. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.2627

3. Crespeau H, Pantier C. Cataract surgery. Inter Bloc. (2017) 36(4):212–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bloc.2017.09.001

4. World Health Organization (WHO). Blindness and visual impairment (2021). Available online at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/blindness-and-visual-impairment (accessed September 26, 2023).

5. Bourne RRA, Steinmetz JD, Saylan M, Mersha AM, Weldemariam AH, Wondmeneh TG, et al. Causes of blindness and vision impairment in 2020 and trends over 30 years, and prevalence of avoidable blindness in relation to VISION 2020: the right to sight: an analysis for the global burden of disease study. Lancet Glob Heal. (2021) 9(2):e144–60. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30489-7

6. Khairallah M, Kahloun R, Bourne R, Limburg H, Flaxman SR, Jonas JB, et al. Number of people blind or visually impaired by cataract worldwide and in world regions, 1990 to 2010. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. (2015) 56(11):6762–9. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-17201

7. Wang W, Yan W, Fotis K, Prasad NM, Lansingh VC, Taylor HR, et al. Cataract surgical rate and socioeconomics: a global study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. (2016) 57(14):5872–81. doi: 10.1167/iovs.16-19894

8. Khanna R, Pujari S, Sangwan V. Cataract surgery in developing countries. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. (2011) 22(1):10–4. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e3283414f50

9. Ajibode H, Jagun O, Bodunde O, Fakolujo V. Assessment of barriers to surgical ophthalmic care in South-Western Nigeria. J West African Coll Surg. (2012) 2(4):38–50. 25453003. 4220483.

10. Jolley E, Virendrakumar B, Pente V, Baldwin M, Mailu E, Schmidt E. Evidence on cataract in low- and middle-income countries: an updated review of reviews using the evidence gap maps approach. Int Health. (2022) 14:I68–83. doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihab072

11. Aboobaker S, Courtright P. Barriers to cataract surgery in Africa: a systematic review. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. (2016) 23(1):145–9. doi: 10.4103/0974-9233.164615

12. Zhang XJ, Jhanji V, Leung CKS, Li EY, Liu Y, Zheng C, et al. Barriers for poor cataract surgery uptake among patients with operable cataract in a program of outreach screening and low-cost surgery in rural china. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. (2014) 21(3):153–60. doi: 10.3109/09286586.2014.903981

13. Lewallen S, Schmidt E, Jolley E, Lindfield R, Dean WH, Cook C, et al. Factors affecting cataract surgical coverage and outcomes: a retrospective cross-sectional study of eye health systems in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Ophthalmol. (2015) 15(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12886-015-0063-6

14. Census India. Population Composition (2011). p. 0–14. Available online at: https://censusindia.gov.in/vital_statistics/SRS_Report/9Chap 2—2011.pdf (accessed September 22, 2023).

15. Allen D, Vasavada A, Allen D. Clinical review cataract and surgery for cataract. BMJ. (2006) 333:128–32. doi: 10.1136/bmj.333.7559.128

16. Richter GM, Chung J, Azen SP, Varma R, Los Angeles Latino Eye Study Group. Prevalence of visually significant cataract and factors associated with unmet need for cataract surgery: Los Angeles Latino eye study. Ophthalmology. (2009) 116(12):2327–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.05.040

17. Dr Rajendra Prasad Centre for Opthalmic Science, AIIMS ND. National Blindness & Visual Impairment Survey India 2015–2019—A Summary Report. Available online at: https://npcbvi.gov.in/writeReadData/mainlinkFile/File341.pdf (accessed September 23, 2023).

18. Longitudinal Ageing Study in India (LASI). Available online at: https://www.iipsindia.ac.in/lasi (accessed March 29, 2023).

19. Bharati B, Sahu KS, Pati S. The burden of vision, hearing, and dual sensory impairment in older adults in India, and its impact on different aspects of life-findings from LASI wave 1. Aging Heal Res. (2022) 2:100062. doi: 10.1016/j.ahr.2022.100062

20. Purola PKM, Nättinen JE, Ojamo MUI, Koskinen SVP, Uusitalo HMT. Prevalence and 11-year incidence of cataract and cataract surgery and the effects of socio-demographic and lifestyle factors. Clin Ophthalmol. (2022) 16:1183–95. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S355191

21. Wasekar SA, Lavangare SR. Study of socio-demographic profile and cataract surgical coverage of geriatric cataract patients in a rural field practice area of a municipal tertiary care teaching hospital in Mumbai. India Natl J Res Community Med. (2019) 8(4):277. doi: 10.26727/NJRCM.2019.8.4.277-282

22. Vimalraj AN, Anitha A, Amal AV. Prevalence, barriers and gender inequalities in cataract surgical coverage in a rural village in South India. Eur J Mol Clin Med. (2022) 09(07):3123–32.

23. Van Zon SK, Reijneveld SA, Mendes de Leon CF, Bültmann U. The impact of low education and poor health on unemployment varies by work life stage. Int J Public Health. (2017) 62(9):997–1006. doi: 10.1007/s00038-017-0972-7

24. Yin Q, Hu A, Liang Y, Zhang J, He M, Lam DSC, et al. A two-site, population-based study of barriers to cataract surgery in rural China. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. (2009) 50(3):1069–75. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2783

25. Chen X, Orom H, Hay JL, Waters EA, Schofield E, Li Y, et al. Differences in rural and urban health information access and use. J Rural Heal. (2019) 35(3):405–17. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12335

26. Nirmalan PK, Thulasiraj RD, Maneksha V, Rahmathullah R, Ramakrishnan R, Padmavathi A, et al. A population based eye survey of older adults in Tirunelveli district of south India: blindness, cataract surgery, and visual outcomes. Br J Ophthalmol. (2002) 86:505–12. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.5.505

27. Global eye care targets endorsed by Member States at the 74th World Health Assembly (2021). Available online at: https://www.who.int/news/item/27-05-2021-global-eye-care-targets-endorsed-by-member-states-at-the-74th-world-health-assembly (accessed September 22, 2023).

28. Nathaniel GI, Eze UA, Adio AO. Vision 2020 – The right to sight: how much has been achieved in Nigeria? And what next? Niger J Med. (2022) 31(3):366–70. doi: 10.4103/NJM.NJM_187_21

29. Madaki S, Babanini A, Habib S. Cataract surgical coverage and visual outcome using RAAB in Birnin Gwari local government area, north west Nigeria. Niger J Basic Clin Sci. (2020) 17(2):91. doi: 10.4103/njbcs.njbcs_7_20

30. Mohammadi SF, Ashrafi E, Mohazzab-Torabi S, Delshad-Aghdam H, Katibeh M. Cataract surgical coverage in Kurdistan, Iran. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. (2021) 16(4):700–1. doi: 10.18502/JOVR.V16I4.9763

31. Das R, Sengupta B, Debnath A, Bhattacharjya H. Cataract and associated factors among OPD attendees in a teaching institute of North East India: a baseline observation. J Family Med Prim Care. (2021) 10(9):3223. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_2493_20

32. Nangia V, Jonas JB, Gupta R, Khare A, Sinha A. Prevalence of cataract surgery and postoperative visual outcome in rural central India: central India eye and medical study. J Cataract Refract Surg. (2011) 37(11):1932–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2011.08.020

Keywords: cataract, surgery, older adults, LASI, unmet needs

Citation: Das S, Sinha A, Kanungo S and Pati S (2024) Decline in unmet needs for cataract surgery among the ageing population in India: findings from LASI, wave-1. Front. Health Serv. 4:1365485. doi: 10.3389/frhs.2024.1365485

Received: 4 January 2024; Accepted: 23 February 2024;

Published: 19 March 2024.

Edited by:

Yifan Xiang, Buck Institute for Research on Aging, United StatesReviewed by:

Hang Xie, Sun Yat-sen University, ChinaBing Li, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (DOE), United States

© 2024 Das, Sinha, Kanungo and Pati. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Srikanta Kanungo c3Jpa2FudGFrMTA5QGdtYWlsLmNvbQ== Sanghamitra Pati ZHJzYW5naGFtaXRyYTEyQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

†ORCID Sasmita Das orcid.org/0000-0002-0381-3256 Abhinav Sinha orcid.org/0000-0001-7702-3671 Srikanta Kanungo orcid.org/0000-0001-5647-0122 Sanghamitra Pati orcid.org/0000-0002-7717-5592

Sasmita Das†

Sasmita Das† Abhinav Sinha

Abhinav Sinha Srikanta Kanungo

Srikanta Kanungo Sanghamitra Pati

Sanghamitra Pati