94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Health Serv., 07 February 2024

Sec. Implementation Science

Volume 4 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/frhs.2024.1305955

This article is part of the Research TopicAdvancements and Challenges in Implementation Science: 2023View all 12 articles

Patricia J. van der Laag1*

Patricia J. van der Laag1* Berber G. Dorhout2,3

Berber G. Dorhout2,3 Aaron A. Heeren2

Aaron A. Heeren2 Cindy Veenhof2,4,5

Cindy Veenhof2,4,5 Di-Janne J. A. Barten2,4

Di-Janne J. A. Barten2,4 Lisette Schoonhoven1,6

Lisette Schoonhoven1,6

Background: To date, implementation strategies reported in the literature are commonly poorly described and take the implementation context insufficiently into account. To unravel the black box of implementation strategy development, insight is needed into effective theory-based and practical-informed strategies. The current study aims to describe the stepwise development of a practical-informed and theory-based implementation strategy bundle to implement ProMuscle, a nutrition and exercise intervention for community-dwelling older adults, in multiple settings in primary care.

Methods: The first four steps of Implementation Mapping were adopted to develop appropriate implementation strategies. First, previously identified barriers to implementation were categorized into the constructs of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR). Second, the CFIR-ERIC matching tool linked barriers to existing implementation strategies. Behavioral change strategies were added from the literature where necessary. Third, evidence for implementation strategies was sought. Fourth, in codesign with involved healthcare professionals and implementation experts, implementation strategies were operationalized to practical implementation activities following the guidance provided by Proctor et al. These practical implementation activities were processed into an implementation toolbox, which can be tailored to a specific context and presents prioritized implementation activities in a chronological order.

Results: A previous study identified and categorized a total of 654 barriers for the implementation of a combined lifestyle intervention within the CFIR framework. Subsequently, the barriers were linked to 40 strategies. Due to the fact that many strategies impacted multiple barriers, seven overarching themes emerged based on the strategies: assessing the context, network internally, network externally, costs, knowledge, champions, and patient needs and resources. Codesign sessions with professionals and implementation experts resulted in the development of supported and tangible implementation activities for the final 20 strategies. The implementation activities were processed into a web-based implementation toolbox, which allows healthcare professionals to tailor the implementation activities to their specific context and guides healthcare professionals to prioritize implementation activities chronologically during their implementation.

Conclusion: A theory-based approach in combination with codesign sessions with stakeholders is a usable Implementation Strategy Mapping Method for developing a practical implementation strategy bundle to implement ProMuscle across multiple settings in primary care. The next step involves evaluating the developed implementation strategies, including the implementation toolbox, to assess their impact on the implementation and adoption of ProMuscle.

Implementation science focuses on translating evidence-based programs (EBPs) into practice (1). Methods or techniques that are employed to overcome barriers and enhance the adoption, implementation, sustainment, and scale-up of such EBPs are called implementation strategies (2). Implementation strategies are designed to target barriers at different levels, such as the intervention, recipient, organizational, policy, and professional levels (3). Numerous studies describe theories and taxonomies and present implementation strategies tailored to specific levels (3). Evidence-based, detailed implementation strategies are crucial for the successful implementation of EBPs in daily practice (4). However, most studies lack an adequate description of the strategies and how to match them to barriers, which makes it difficult to select optimal strategies and to understand whether and how strategies could be effective for overcoming barriers and supporting the implementation of EBPs (1, 5).

Notably, it is not expected that every setting has similar barriers for implementation; instead, various combinations of barriers are likely to emerge, which may change over time (6, 7). The lack of guidance makes it challenging to translate the strategies to specific contexts for different EBPs (5, 8). Selecting appropriate implementation strategies and mapping and tailoring them to address the barriers in the specific context require a systematic approach. Using an Implementation Strategy Mapping Method encompasses the implementation practice and results in transparent strategies; this enables researchers or implementers to assess whether the developed strategies align with their specific context.

Today, several Implementation Strategy Mapping Methods guide the process of selecting and developing implementation strategies (8), each containing three general steps. First, determinants that could facilitate or hamper the implementation of an EBP within the local context should be assessed. Second, change methods (e.g., behavioral, organizational, or system change) to address these determinants must be identified. At last, implementation strategies need to be developed or selected that incorporate these change methods (5).

One of the most frequently used Implementation Strategy Mapping Methods is “Implementation Mapping” (9). Implementation Mapping, described by Fernandez et al. (9), addresses the need for a theory-based method to influence determinants for implementation. Nowadays, Implementation Mapping is widely used in implementation science for selecting and developing implementation strategies. Implementation Mapping describes five tasks to select, develop, execute, and evaluate strategies based on existing theory to enhance the alignment between context and implementation (9). The tasks are iterative, involving continual revisiting of previous steps throughout the process to ensure all adopters and implementers, outcomes, determinants, and objectives are addressed.

To enhance the alignment of implementation strategies with the context of EBP implementation, Fernandez (9) emphasized the need to engage stakeholders in a collaborative process at each step of Implementation Mapping (9). The context in which an intervention is implemented plays a significant role in deciding whether a strategy will be effective. Moreover, strategies that align with the context will contribute to improved implementation and adoption of an EBP (1, 10), achieving more contextually adapted strategies. The experiences of stakeholders can complement implementation science expertise and provide valuable information for identifying implementation challenges and developing possible ways to target these challenges. There are different ways to engage stakeholders in the development of implementation strategies. Codesign is a method that seeks to optimize the alignment of implementation strategies with the context. Codesign involves the collaboration of both trained and untrained individuals in the creative design and development process (1).

In the literature, there are hardly any studies that fully and systematically describe the selection and development of implementation strategies following the crucial steps of an Implementation Strategy Mapping Method, including attention to stakeholder engagement in the identification of barriers and in the selection and development of implementation strategies (11). With this study, we aimed to provide a transparent description of the strategy development process for implementing a combined lifestyle intervention across multiple settings in primary care following Implementation Mapping as an Implementation Strategy Mapping Method, ensuring attention to specific contexts by engaging relevant stakeholders throughout the process.

The combined lifestyle intervention is called ProMuscle, which aims to maintain the independence of older adults. ProMuscle is a 12-week program that combines resistance exercise training with dietary consultations to increase the daily protein intake. Over the years, ProMuscle has undergone further development and has shown promising effects on physical functioning, strength, and muscle mass among community-dwelling older adults (12). Given the rapid aging of the population, the implementation of combined lifestyle interventions like ProMuscle holds significant potential in contributing to the maintenance of physical independence among older individuals. Ultimately, this could have a positive effect on the prevalence of chronic diseases and reduce healthcare costs.

Therefore, the current study aims to develop implementation strategies using codesign sessions with relevant stakeholders to facilitate the implementation and adoption of ProMuscle across multiple settings in primary care.

A qualitative inductive, codesign approach was used to develop theory-based and practical-informed strategies that could align with different contexts. The reporting of this study adheres to the Standard for Reporting Implementation Studies (StaRI) checklist (13).

This study is part of the PUMP-fit study, which is centered on implementing ProMuscle in the Netherlands. The primary objective of the PUMP-fit study is to increase the adoption of ProMuscle by selecting and evaluating theory-based, context-tailored implementation strategies. This study was conducted in the Region Foodvalley in the Netherlands. The Region Foodvalley is a collaboration between eight municipalities, local healthcare organizations, universities, and research institutes. Its target is to provide a better nutritional environment for the residents of the region. Within the Region Foodvalley, more than 200 healthcare professionals (HCPs; including physiotherapists and dieticians) work within primary care settings across eight municipalities.

The implementation strategies were developed for, and in codesign with, these professionals because they are the target population for implementing ProMuscle in primary care.

Physiotherapists and dieticians working in the Region Foodvalley were recruited through various channels, including the interest list of the PUMP-fit study, social media announcements, calls for participation in newsletters of professionals’ associations, and local initiatives. Healthcare professionals were included if they were physiotherapists or dieticians involved in treating older adults within primary care.

Moreover, implementation experts from the Netherlands were personally invited to participate in this study. Specifically, their involvement aimed to provide input on the conceptualization of implementation strategies.

Codesign studies share similarities with focus group studies in qualitative research, as high-quality interactive discussions among the cocreators are pivotal for a successful process. Although qualitative research lacks existing rules regarding recommended sample sizes, recommendations have been made to recruit cohorts of 6–12 participants for focus group studies (14). Considering these factors, a recommendation of 10–12 participants for the codesign process is advised, which may also account for dropouts due to the process being conducted over multiple sessions.

In this study, the Implementation Strategy Mapping Method, “Implementation Mapping”, was adopted (9). As this study aims to describe the development of implementation strategies, the first four of the five steps of Implementation Mapping were followed. Due to the variations in primary care settings across the Netherlands, it is expected that the context in which ProMuscle is implemented will present diverse contextual determinants; hence, it is anticipated that the implementation strategies will vary for each setting. Therefore, the involvement of various stakeholders during the whole process was perceived as an essential step to align the strategies with the context. Stakeholder involvement was incorporated in various ways into these steps. The procedures for each step are described below.

A preliminary aspect of the PUMP-fit study was the identification of barriers and facilitators of the implementation of a combined lifestyle intervention. Determinants influencing the implementation of ProMuscle in community care were identified by a recently performed scoping review; detailed descriptions of these determinants can be found elsewhere (15). In short, a literature review, including stakeholder consultation, was conducted to identify determinants influencing the implementation of combined lifestyle interventions for community-dwelling older adults. The identified barriers were categorized into the constructs of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) (16). The CFIR consolidates implementation determinants from various implementation theories and comprises five major domains (namely, intervention characteristics, outer setting, inner setting, characteristics of individuals, and process) made up of 39 constructs that influence the implementation of innovations into practice. Eventually, to validate the identified barriers and facilitators in the literature, 19 relevant stakeholders were consulted. During (group) interviews, 13 physiotherapists, 3 dieticians, and 3 community-dwelling older adults were asked about determinants for implementation, eventually prioritizing the identified barriers.

In addition to mapping and prioritizing the determinants described by Implementation Mapping, relevant implementation models addressing behavioral change (17, 18), organizational change (19), and implementation effectiveness (20) were consulted to establish links between the emerged CFIR constructs and the underlying theoretical constructs. By linking determinants to theoretical constructs, relevant theories were identified, allowing for the adoption of uniform definitions. Eventually, this linking of determinants to underlying constructs provides further direction for justifying possible strategies, which is part of the next steps (21).

Two methods were used to link the identified barriers to implementation strategies. First, existing taxonomies, models, and theories described in the literature were studied to select implementation strategies. After that, stakeholders were consulted to contribute to the development of additional strategies.

The first taxonomy used to select strategies was the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) taxonomy (22). The ERIC taxonomy is a widely used compilation of 73 implementation strategies consisting of definitions sourced from a wide range of implementation experts. To link the identified barriers to possible implementation strategies, the CFIR-ERIC Matching Tool was used (5). The CFIR-ERIC Matching Tool was developed in collaboration with implementation experts (5). These experts rated the importance and feasibility of compiling 73 implementation strategies to barriers categorized by the CFIR framework (5). The tool allows users to select the identified CFIR determinants. Hereafter, a list of relevant strategies is presented per identified determinant for implementation. For each strategy, the tool provides the percentage of experts who ranked that particular strategy in their top seven. This percentage can be interpreted at two levels of endorsed strategies, namely, Level 1 endorsed ERIC strategies (i.e., more than 50% of the experts ranked this as one of their top seven strategies for that barrier) and Level 2 endorsed ERIC strategies (i.e., between 20% and 50% of the experts ranked this as one of their top seven strategies for that barrier) (5, 23). The research group determined that, for the continuation of this study, the top three strategies with the highest agreement or three strategies with an agreement higher than 50% would be used.

Although the CFIR-ERIC Matching Tool provides a convenient global overview of appropriate implementation strategies, the ERIC taxonomy is not exhaustive, and additional efforts are needed to do justice to all identified barriers (24). The research group hypothesized that some barriers might be rooted in the specific behavior of healthcare professionals or older adults receiving the intervention and that these aspects were underrepresented in the ERIC taxonomy. Therefore, an additional literature search was conducted to incorporate behavioral change strategies. Implementation taxonomies and theories, including the taxonomy of Kok et al. (25), Greenhalgh et al. (26), and the Theoretical Domain Framework (17), were consulted to identify implementation strategies targeting behavior.

In addition to selecting implementation strategies based on taxonomies and theories described in the literature, input from involved healthcare professionals was retrieved during two codesign sessions. Codesign sessions were scheduled with 10 healthcare professionals (physiotherapists and dieticians). In total, two 90-min online (due to the COVID restrictions) codesign sessions with healthcare professionals were held. At the beginning of the sessions, healthcare professionals were informed about ProMuscle through a short presentation. Under the supervision of a researcher, healthcare professionals discussed possible effective strategies to overcome barriers for implementing ProMuscle. To obtain full objectivity, healthcare professionals were unaware of the implementation strategies identified from the literature. In the end, if strategies from the literature were not mentioned by healthcare professionals, the researcher would propose them to the healthcare professionals to explore whether they could also be considered effective strategies.

The strategies retrieved from both the literature and codesign sessions were described in a matrix. Where possible, the research group matched the strategies proposed by healthcare professionals to those from the literature and combined them into the matrix. The strategies that remained and could not be combined with the strategies from the literature were treated as new and added to the matrix.

Proctor et al. stated that providing theoretical justification for implementation strategies can address their potential working mechanisms, giving insight into how and why a strategy might facilitate change (2). Theoretical justification can take various forms: empirical, theory-based, and pragmatic (2).

Empirical evidence is considered evidence from research or an individual’s knowledge and experience with strategies that have been proven effective.

Theory-based evidence refers to the theoretical knowledge gained in a research field or concerning a specific subject.

Pragmatic justification is derived from clinical expertise, experiences, or the needs of relevant stakeholders concerning overcoming barriers. Although pragmatic evidence does not provide empirical or theoretical evidence for strategies, it can provide insights into the rationale for identifying factors that should be addressed and how strategies could address them (2, 27). In the context of the present study, the research group sought evidence for the identified implementation strategies in scientific literature. The literature that described theories and taxonomies linking specific implementation determinants to strategies was used. First, studies that investigated individual strategies were sought in the database of EPOC and implementation science journals. If the effectiveness of specific strategies was not examined in the literature, theory-based justification was sought in existing theories for the underlying constructs identified in step 1. Also, studies reporting implementation strategies in similar contexts were consulted.

In addition to seeking empirical evidence and theoretical justification, we aimed to derive pragmatic justification during the codesign sessions with healthcare professionals. Healthcare professionals discussed possible effective strategies to overcome barriers for implementing ProMuscle and provided insights into the effectiveness of the strategies based on their clinical expertise and needs. Also, pragmatic justification for the strategies was obtained during meetings with implementation experts and researchers, as well as through interviews with older adults, drawing on their experiences and needs.

The next step in developing appropriate implementation strategies involves operationalizing the implementation activities in full detail. The literature emphasizes the needs and challenges of specifying and reporting implementation strategies (2). Guided by the recommendations for specifying and reporting implementation strategies outlined by Proctor et al. (2), the operationalization of the implementation strategies considered seven dimensions: actor, action, action targets, temporality, dose, implementation outcomes addressed, and theoretical justification. These dimensions should be fully described to facilitate measurement and reproducibility.

With respect to the current study, a matrix was developed to describe all seven dimensions of each proposed implementation strategy.

For this step, codesign with stakeholders was established in an iterative way through consensus meetings with the research team, meetings with two implementation experts, and interactive work sessions with healthcare professionals, including physiotherapists and dieticians. During two 90-min codesign sessions, healthcare professionals were divided into groups. Across the sessions, five groups worked with themes containing several overlapping strategies to make sure all strategies had been covered and to limit workload per codesign session.

The matrix was continuously supplemented with input from healthcare professionals, implementation experts, and research groups during the sessions, resulting in a complete matrix that incorporated input from stakeholders and the literature.

To meet the needs of professionals, implementation materials, in the form of an implementation toolbox, were developed (Implementation Mapping step 4). It was important to create a practical tool to assist healthcare professionals and provide them with the ability to tailor the implementation strategies to their specific context. As mentioned earlier, the research group was aware of the different settings in which ProMuscle would be implemented, consequently leading to different contexts and barriers.

During the development of the implementation toolbox, the research group consulted 1 implementation expert and 10 professionals to create a practical tool for healthcare professionals implementing ProMuscle. The described implementation activities were presented to an implementation expert. Also, based on the experiences of the experts, the most practical way to present the activities in an online platform was discussed. Moreover, the presentation of the tool was designed to be user-friendly and inviting for professionals to use it.

The research team, along with Dutch implementation experts (n = 2) and HCPs, i.e., physiotherapists (n = 8) and dieticians (n = 2) working in the Region Foodvalley, participated in the interactive codesign sessions to provide input for the development of implementation strategies. Table 1 presents the participation of stakeholders across each step.

Table 1. Participants of the codesign sessions presented for all four steps of the chosen Implementation Strategy Mapping Method.

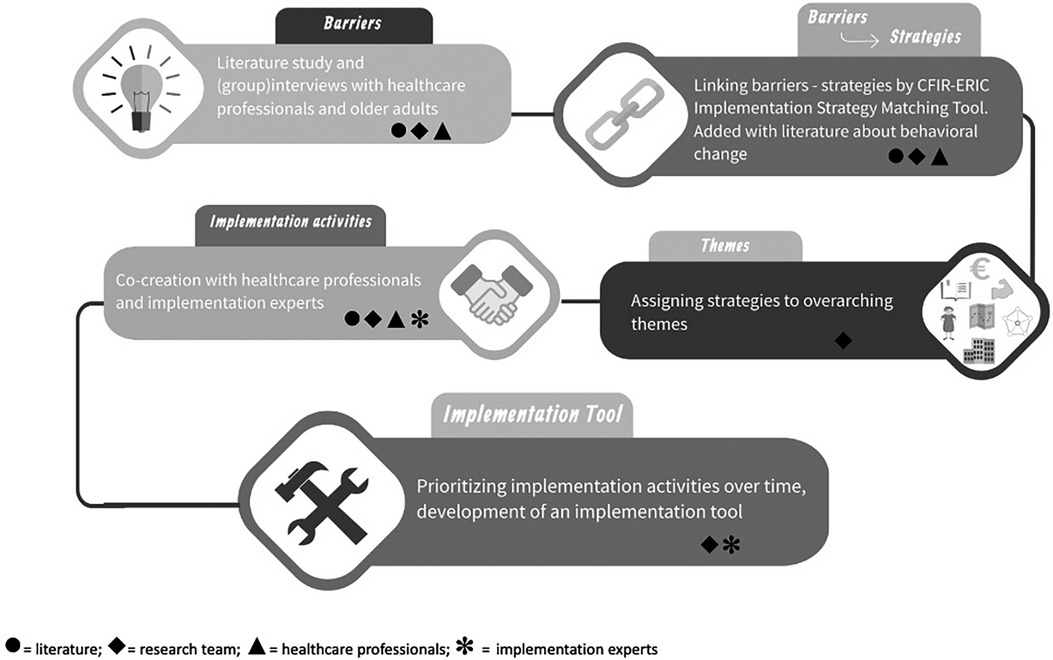

Implementation strategies for facilitating the implementation of ProMuscle in primary care were selected, described, and operationalized using four adapted steps of Implementation Mapping. In all four steps, different ways to engage stakeholders were included, as presented in the following. Figure 1 visualize the steps including the methods used to retrieve input and the involved stakeholders. Because of the fact that ProMuscle will be implemented in multiple settings, a significant number of barriers and linking strategies emerged. Therefore, an extra step, assigning strategies to themes, was added to step 2 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flowchart development implementation strategy bundle and implementation toolbox, including methods used to retrieve input.

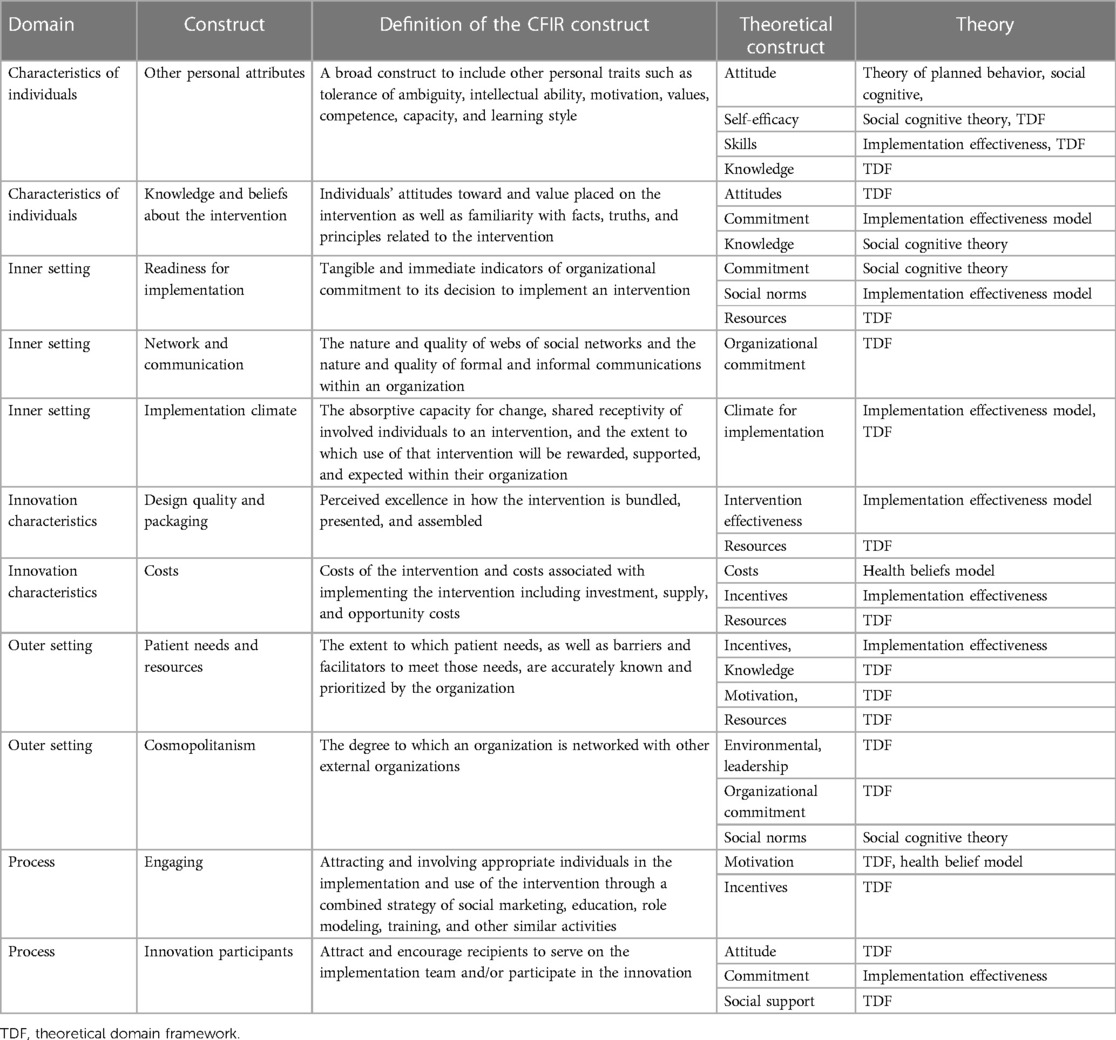

In a previous study (15), determinants influencing the implementation of combined lifestyle interventions were identified through a literature review and interviews with relevant stakeholders. A total of 654 determinants were identified, representing all CFIR domains, that could influence the implementation of combined lifestyle interventions similar to ProMuscle (15). Relevant stakeholders like physiotherapists and dieticians validated and prioritized these determinants during interviews. This resulted in 10 main barriers for the implementation of a combined lifestyle intervention in primary care. The top 10 most common determinants are as follows: “other personal attributes,” “knowledge and beliefs about the intervention,” “readiness for implementation,” “network and communication,” “implementation climate,” “design quality and packaging,” “costs,” “patient needs and resources,” “cosmopolitanism,” and “engaging” (Table 2).

Table 2. Identified determinants influencing the implementation of combined lifestyle interventions linked to theoretical constructs.

These determinants were linked to theoretical constructs. Some theoretical constructs were similar for multiple determinants. Moreover, most determinants could be linked to multiple theoretical constructs. Table 2 presents all 10 determinants with underlying constructs. The models used to link the determinants to constructs were the theoretical domain framework (17), implementation effectiveness model (28), health belief model (29), and social cognitive theory (30).

The selected constructs from CFIR in the previous step were entered in the CFIR-ERIC Matching Tool, and this method resulted in multiple strategies advised for the specific determinants. The initial step involves excluding strategies deemed not applicable because they did not align with the context for implementing ProMuscle. For example, the strategy to make billing easier was a level 2 endorsed strategy for the construct “costs.” However, the combined lifestyle intervention ProMuscle is not reimbursed, and recipients are required to pay for participation. Therefore, the research group decided that this strategy would not be suitable for implementation in this phase. However, if ProMuscle were to be reimbursed, this strategy could be considered and added to the strategy bundle if deemed necessary.

For constructs “patient needs and resources,” “engaging,” and “other personal attributes,” the CFIR-ERIC strategy matching tool did not yield (appropriate) strategies to align with the context. In the end, this step resulted in 40 appropriate implementation strategies. Of the 40 strategies, 32 were retrieved from the ERIC taxonomy (22), 5 from the TDF, and 2 from the taxonomy of Kok et al. (25).

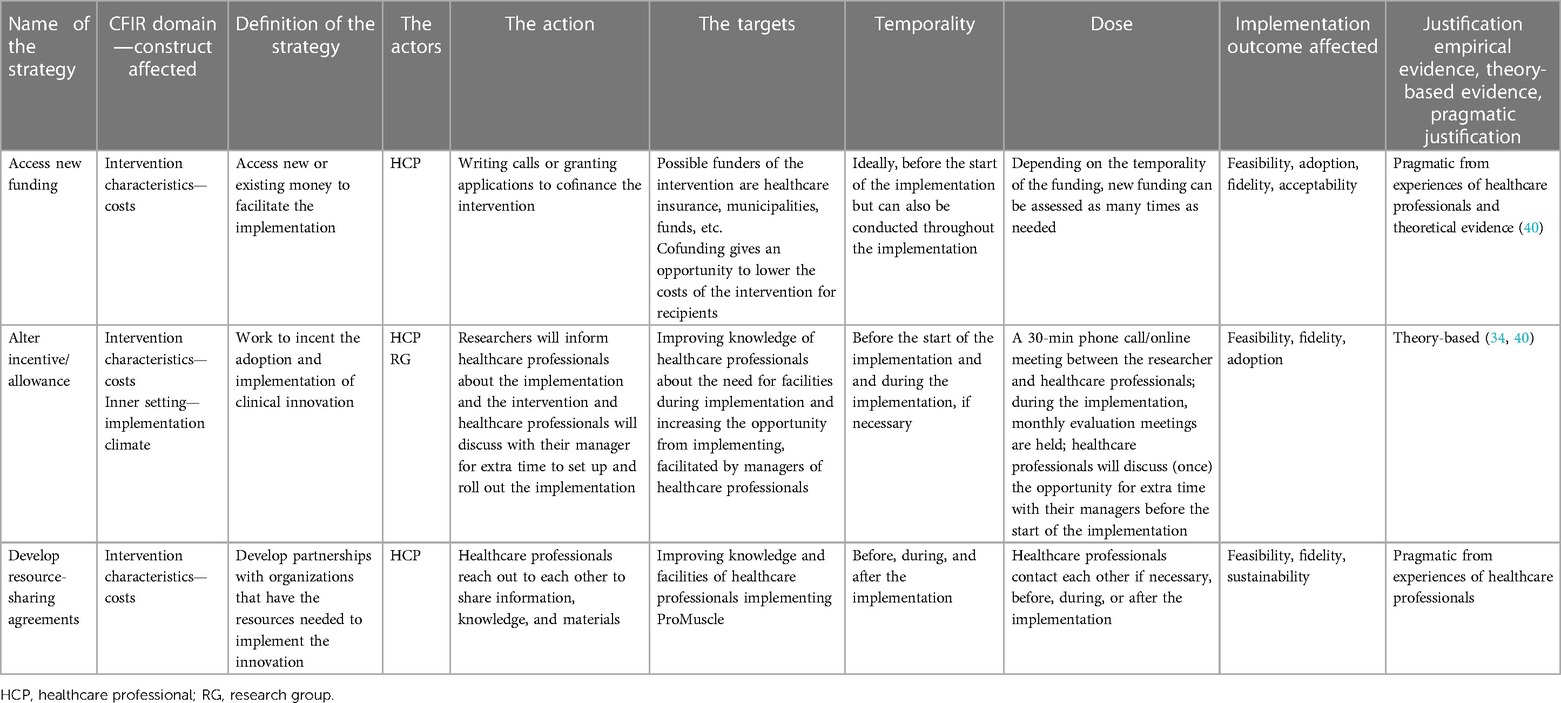

In addition, the input from healthcare professionals and implementation experts during the codesign sessions was mostly practical and was not specifically linked to implementation strategies as described in the literature and the ERIC taxonomy. The activities proposed by healthcare professionals align with the action dimension, according to Proctor et al. (2), for most of the strategies that were found in the literature (as presented in Table 3).

For the strategies derived from the literature that were not mentioned by healthcare professionals, the researchers asked whether the remaining strategies could be effective or not. Three strategies that appeared in the literature but were not mentioned by healthcare professionals were “conduct local need assessment,” “assess for readiness and identify barriers and facilitators,” and “develop academic partnerships.” Because the healthcare professionals were not experienced in implementation science, and likely had insufficient awareness for assessing the context (needs, barriers, and facilitators), the research group decided to elaborate on these strategies anyway. Moreover, the three strategies were classified as level 1 strategies according to the CFIR-ERIC Matching Tool.

To illustrate the elaboration of this step, in the following box (Box 1), we present how the construct “costs” within the domain intervention characteristics was linked to implementation strategies.

The literature search and consultation with healthcare professionals revealed a great number of strategies. During consultation with the research group, it was noticed that some implementation strategies were applicable to multiple determinants. Therefore, it was hypothesized that some strategies would affect multiple barriers. In addition, the large number of strategies could burden healthcare professionals (31). As a result, the research group aimed to identify overarching themes within the strategies and introduced an extra step within the adopted version of Implementation Mapping. A total of four consensus meetings were conducted with the research group to provide an overview, create overarching themes, and assign strategies to the themes. Ultimately, 20 unique strategies were assigned to 7 overarching themes: assessing the context, network internally, network externally, costs, knowledge, champions, and patient needs and resources. Table 3 presents the seven themes, providing a complete overview of strategies derived from the literature and input from healthcare professionals, along with the constructs to which these strategies were linked. Appendix A provides a description of the constructs that eventually fell under the themes. Box 2 presents the description of the theme costs.

Eventually, this third step resulted in justification for every strategy, which is extensively described in Appendix B. Empirical evidence was found for activities within the following strategies: “assess for readiness and identify barriers and facilitators” (32, 33), “build a coalition” (34), “conduct ongoing training” (35), “conduct educational meetings” (34, 36), and “intervene with patients and consumers to enhance uptake and adherence” (35). Most strategies could be justified by underlying theoretical constructs or models mostly based on organizational change (19, 20, 37), system change (34, 38–40), and behavior change (17, 25, 41, 42). Also, during the codesign sessions, healthcare professionals and implementation experts provided pragmatic evidence from their own experience with implementation, as well as based on their needs. In previous research, older adults were interviewed, which resulted in pragmatic evidence for implementation strategies concerning the strategies in theme “Patient needs and resources”.

To illustrate the improved methodology of developing implementation strategies, the theme costs will be described in detail in Box 3. For a complete description of all strategies, including the evidence for each strategy, see Appendix B.

The research group translated the retrieved strategies into Dutch and provided global information about the strategies to further operationalize them during the codesign sessions.

The first group of healthcare professionals worked with theme costs, and the second group worked with themes process, intervention, and knowledge. The third group worked with themes network internally, network externally, and patient needs and resources. The fourth group worked with theme knowledge. A fifth group consisting of dieticians was considered a validation group because the other four groups consisted of physiotherapists. The group of dieticians checked whether they agreed with the proposed activities and were asked if they missed specific activities.

Healthcare professionals provided additional and practical input concerning the “actors,” “action,” “dose,” and “justification” dimensions, according to Proctor et al. (2).

The research group complemented the specification with input from the literature. Input from the literature, research groups, and healthcare professionals resulted in fully detailed implementation strategies for all seven themes. A complete description of the strategies for theme costs is presented in Table 4. For the remaining themes, the strategies are described in Appendix B.

Table 4. Description of strategies concerning the theme costs following the recommendation of Proctor et al. (2).

Themes Assessing the context and champions were seen as important for all other themes. Therefore, the strategies assigned to these themes were considered obligatory to start the implementation.

The research group consulted multiple implementation experts and professionals to create a practical tool for healthcare professionals implementing ProMuscle. Implementation experts mentioned that it was important for the tool to be easy to use. It should not take much time to understand the tool. They emphasized the importance of providing an overview where professionals should not have to perform extensive scrolling. Also, the implementation activities should be presented in chronological order, rather than by theme.

Therefore, the research team assigned every implementation activity to a specific time frame. The activities could be assigned to one or more time frames. The following time frames were used: 8–6 weeks preimplementation, 6–4 weeks preimplementation, 4–0 weeks preimplementation, implementation, and sustainment. This resulted in an online implementation toolbox in which implementation actions are chronologically described and bundled per theme. In this way, healthcare professionals are free to choose which theme would apply to their specific context. Moreover, a function was built to check whether actions were conducted and to add remarks.

The four steps resulted in a full description of 20 strategies, divided over 7 overarching themes. A complete description of all 20 strategies and the barriers they address is presented in Appendix B. The theory-based and practical implementation activities were added to a web-based implementation tool. Figure 1 presents an overview of the conducted steps and the methods used to retrieve input. As shown in Figure 1, the steps of Implementation Mapping were slightly changed, and an extra step (themes) was added. Moreover, in every step, relevant stakeholders provided input to provide an implementation strategy bundle for healthcare professionals that can be tailored to their specific contexts, and added this bundle in an online toolbox.

This paper describes the methodology of developing a theoretically justified and practically tailored implementation strategy bundle to implement a combined lifestyle intervention for community-dwelling older adults across multiple settings in primary care. The Implementation Strategy Mapping Method was guided by Implementation Mapping (9). Initially, the four steps of Implementation Mapping were followed. Because this study focuses on multiple settings in primary care and various contexts were explored, a great number of determinants for implementation emerged, which ultimately led to 40 linked implementation strategies. The addition of an extra step to the methodology was deemed necessary to provide structure to the array of implementation strategies. Moreover, the diverse collection of strategies could enable healthcare professionals to tailor their strategies according to their specific contexts.

Ultimately, the structural approach guided by Implementation Mapping and the embedded codesign with healthcare professionals and implementation experts led to the development of a practical and theory-informed strategy bundle. Through codesign, the strategies were tailored to the context in which they were supposed to be applied. The implementation toolbox serves as a guide for healthcare professionals, assisting them during the implementation and overcoming barriers related to their contexts.

A large number of implementation strategies, totaling 20, were described in detail and included in the final implementation toolbox for healthcare professionals who aim to implement a combined lifestyle intervention. The large proportion of strategies can be justified by the multiple determinants that were found as possible barriers for implementing a combined lifestyle intervention. For the implementation of a combined lifestyle intervention, determinants at multiple levels can affect the implementation results. Therefore, by including multiple strategies in the implementation toolbox, we can ensure that healthcare professionals can tailor strategies aligning with their specific contexts and can adjust them when encountering other barriers during the implementation process.

The inclusion of the extra step assigning strategies to overarching themes in the development of the implementation strategy was prompted by the perceived burden for healthcare professionals. Creating themes resulted in strategy bundles relating to the specific themes. Multiple studies present the development and use of multicomponent strategies (6, 7, 43, 44). Moreover, the use of multicomponent strategies is highlighted by Cooper et al. (45), where various combinations of strategies were found effective for sustaining the implementation of an EBP (4, 43). The wide use of multicomponent strategies in implementation science, and the ones that were investigated and found effective in different trial studies, is grounded in the understanding that implementation is often influenced not only by one determinant but by a combination of determinants.

Moreover, the context in which an intervention is implemented greatly influences the success of implementation (46). Therefore, as addressed by Nilsen et al. (46), the difference in contexts highlights the importance of tailoring the implementation to specific contexts. This is supported by a Cochrane review in which it was found that tailored implementation strategies were more effective than non-tailored strategies (47, 48).

Because this study described strategies for multiple barriers, an implementation plan can be tailored to the specific contexts in which the intervention is implemented (6). In addition, due to input from healthcare professionals, actions for the strategies are very practical and should be applicable to (mostly) every healthcare practice implementing ProMuscle. Also, determinants for all levels of implementation according to the CFIR were considered in developing the implementation toolbox. Therefore, tailoring an implementation plan to specific contexts should be possible.

This paper not only addresses the development but also gives a transparent and complete description of the developed implementation strategies. It is not entirely surprising that most studies lack a description of the selection and development of implementation strategies and stakeholder engagement; developing strategies following one of the Implementation Strategy Mapping Methods is very time-consuming. However, because the strategies are detailed and based on theory and practice, fellow implementers can use this overview of a strategy bundle (Appendix B) in similar implementation processes of combined lifestyle interventions. Future research should focus on the working mechanism (49) of the implementation strategies developed in this study. With the results of this study, knowledge about the strategies could be used to implement other combined lifestyle interventions for community-dwelling older adults. If the implementation toolbox is found effective, it can be more widely deployed, adjusted to other contexts, or investigated for other interventions.

A strength of this study is that an Implementation Strategy Mapping Method by way of Implementation Mapping (9) was used to guide the process of developing implementation strategies. Implementation Mapping is considered a powerful approach because of its collaborative nature (43), which is perceived as critical in implementation (50). In the case of ProMuscle, where multiple barriers were identified that could influence the implementation of a combined lifestyle intervention, it could be suggested that multiple strategies are needed. But also, that for every setting, different (combinations) of strategies are appropriate. Therefore, other Implementation Strategy Mapping Methods could also be used as guidance for the development of the implementation strategy bundle, for example concept mapping, focus groups or conjoint analysis (8). However, because of the novelty of the research area in implementation strategy development models, little is known about the effectiveness of the models regarding the adoption of the implemented intervention (8). Therefore, we used Implementation Mapping, the most well-known and widely used method that incorporates stakeholder input, and adjusted its steps to better align with the scope of our study (multiple settings).

Another strength is the incorporation of codesign with stakeholders during the identification of determinants and the development of the strategies. Codesign was a great contributor to tailor strategies to the specific context of implementing a combined lifestyle intervention in primary care (1). For developing implementation strategies to implement ProMuscle, it was hypothesized that codesign would be beneficial for the fidelity and feasibility of the strategies and the alignment with the context. Also, stakeholder engagement is an effective way to engage healthcare professionals in further implementation and involvement in the implementation trials (11). The codesign sessions were an organic and iterative process during all four steps. During the codesign sessions, healthcare professionals provided input on possible actions concerning the seven themes. These codesign sessions provided practical input, and all proposed activities could be linked to implementation strategies suggested by the CFIR-ERIC tool and other taxonomies. Moreover, the codesign sessions resulted in tailored implementation strategies for all seven themes. Finally, the correspondence between the results of the literature search and the codesign sessions suggests that the developed implementation strategies match the context in which ProMuscle will be implemented.

A limitation of this study was that the CFIR-ERIC Matching Tool was used to identify strategies for the potential barriers. Although the CFIR-ERIC tool is widely used in implementation science, it is based on the experiences of implementation researchers and not all strategies included in the tool are evaluated for their effectiveness (22). However, this limitation was partly resolved by the literature search conducted in step 3. Although little empirical evidence was found for individual strategies, the justification lies in the theory and models underpinning the strategies to overcome specific barriers when implementing a combined lifestyle intervention. Further research should investigate not only the link between determinants and strategies but also the effectiveness of the bundled implementation strategies.

The utilization of an Implementation Strategy Mapping Method, with an important role for codesign in each step, led to the development of theoretically justified and practical implementation strategies to support healthcare professionals to implement a combined lifestyle intervention for community dwelling older adults. A significant number of implementation strategies are fully described and can serve as a first overview for other implementers. The structural method, taking the context into account by incorporating codesign in all four steps, has resulted in a theoretically informed final product, an implementation toolbox. Therefore, the implementation toolbox could be a practical tool that can be tailored to an individual's context for healthcare professionals willing to implement a combined lifestyle intervention such as ProMuscle. Future research will focus on evaluating the implementation strategy bundle, including the implementation toolbox, regarding the implementation ProMuscle in primary care.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors without undue reservation.

The studies involving humans were approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of UMC Utrecht. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

PL: Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. BD: Writing – review and editing. AH: Writing – review and editing. CV: Writing – review and editing. D-JB: Supervision, Writing – review and editing. LS: Writing – review and editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The research described in this paper was financially supported by a grant from the Regiodeal Foodvalley (162135).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Kirk JW, Nilsen P, Andersen O, Powell BJ, Tjørnhøj-Thomsen T, Bandholm T, et al. Co-designing implementation strategies for the WALK-Cph intervention in Denmark aimed at increasing mobility in acutely hospitalized older patients: a qualitative analysis of selected strategies and their justifications. BMC Health Serv Res. (2022) 22(1):1–16. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-07395-z

2. Proctor EK, Powell BJ, Mcmillen JC. Implementation Strategies: Recommendations for Specifying and Reporting (2013). Available online at: http://www.implementationscience.com/content/8/1/139

3. Leeman J, Birken SA, Powell BJ, Rohweder C, Shea CM. Beyond “implementation strategies”: classifying the full range of strategies used in implementation science and practice. Implement Sci. (2017) 12(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s13012-017-0657-x

4. Powell BJ, Beidas RS, Lewis CC, Aarons GA, McMillen JC, Proctor EK, et al. Methods to improve the selection and tailoring of implementation strategies. J Behav Health Serv Res. (2017) 44(2):177–94. doi: 10.1007/s11414-015-9475-6

5. Waltz TJ, Powell BJ, Fernández ME, Abadie B, Damschroder LJ. Choosing implementation strategies to address contextual barriers: diversity in recommendations and future directions. Implement Sci. (2019) 14(1):1–15. doi: 10.1186/s13012-019-0892-4

6. Bührmann L, Schuurmans J, Ruwaard J, Fleuren M, Etzelmüller A, Piera-Jiménez J, et al. Tailored implementation of internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy in the multinational context of the ImpleMentAll project: a study protocol for a stepped wedge cluster randomized trial. Trials. (2020) 21(1):1–15. doi: 10.1186/s13063-020-04686-4

7. Lowenstein M, Perrone J, Xiong RA, Snider CK, O’Donnell N, Hermann D, et al. Sustained implementation of a multicomponent strategy to increase emergency department-initiated interventions for opioid use disorder. Ann Emerg Med. (2022) 79(3):237–48. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2021.10.012

8. Sridhar A, Olesegun O, Drahota A. Identifying methods to select and tailor implementation strategies to context-specific determinants in child mental health settings: a scoping review. Glob Implement Res Appl. (2023) 3(2):212–29. doi: 10.1007/s43477-023-00086-3

9. Fernandez ME, ten Hoor GA, van Lieshout S, Rodriguez SA, Beidas RS, Parcel G, et al. Implementation mapping: using intervention mapping to develop implementation strategies. Front Public Health. (2019) 7:158.31275915

10. Powell BJ, Fernandez ME, Williams NJ, Aarons GA, Beidas RS, Lewis CC, et al. Enhancing the impact of implementation strategies in healthcare: a research agenda. Front Public Health. (2019) 7:3.30723713

11. Schultes MT, Albers B, Caci L, Nyantakyi E, Clack L. A modified implementation mapping methodology for evaluating and learning from existing implementation. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:836552. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.836552

12. van Dongen EJI, Haveman-Nies A, Doets EL, Dorhout BG, de Groot LCPGM. Effectiveness of a diet and resistance exercise intervention on muscle health in older adults: proMuscle in practice. J Am Med Dir Assoc. (2020) 21(8):1065–72.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.11.026

13. Pinnock H, Barwick M, Carpenter CR, Eldridge S, Grandes G, Griffiths CJ, et al. Standards for reporting implementation studies (StaRI): explanation and elaboration document. BMJ Open. (2017) 7(4):e013318. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013318

14. Leask CF, Sandlund M, Skelton DA, Altenburg TM, Cardon G, Chinapaw MJM, et al. Framework, principles and recommendations for utilising participatory methodologies in the co-creation and evaluation of public health interventions. Res Involv Engagem. (2019) 5(1):1–16. doi: 10.1186/s40900-018-0136-9

15. van der Laag PJ, Dorhout BG, Heeren AA, Veenhof C, Barten DJA, Schoonhoven L. Barriers and facilitators for implementation of a combined lifestyle intervention in community-dwelling older adults: a scoping review. Front Public Health. (2023) 11:1253267. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1253267

16. Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. (2009) 4(1):50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50

17. Michie S, Johnston M, Francis J, Hardeman W, Eccles M. From theory to intervention: mapping theoretically derived behavioural determinants to behaviour change techniques. Appl Psychol. (2008) 57(4):660–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00341.x

18. Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. (1991) 50(2):179–211. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

19. Weiner BJ. A theory of organizational readiness for change. Implement Sci. (2009) 4(1):67. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-67

20. Klein KJ, Conn AB, Sorra JS. Implementing computerized technology: an organizational analysis. J Appl Psychol. (2001) 86(5):811–24. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.86.5.811

21. Ruiter RAC, Crutzen R. Core processes: how to use evidence, theories, and research in planning behavior change interventions. Front Public Health. (2020) 8:247. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00247

22. Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, Damschroder LJ, Smith JL, Matthieu MM, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. (2015) 10(1). doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1

23. Shin MH, Montano ARL, Adjognon OL, Harvey KLL, Solimeo SL, Sullivan JL. Identification of implementation strategies using the CFIR-ERIC matching tool to mitigate barriers in a primary care model for older veterans. Gerontologist. (2023) 63(3):439–50. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnac157

24. Powell BJ, McMillen JC, Proctor EK, Carpenter CR, Griffey RT, Bunger AC, et al. A compilation of strategies for implementing clinical innovations in health and mental health. Med Care Res Rev. (2012) 69:123–57. doi: 10.1177/1077558711430690

25. Kok G, Gottlieb NH, Peters GJY, Mullen PD, Parcel GS, Ruiter RAC, et al. A taxonomy of behaviour change methods: an intervention mapping approach. Health Psychol Rev. (2016) 10(3):297–312. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2015.1077155

26. Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Bate P, Kyriakidou O, Macfarlane F, Peacock R. How to spread good ideas: a systematic review of the literature on diffusion, dissemination and sustainability of innovations in health service delivery and organisation. Report for the National Coordinating Centre for NHS Service Delivery and Organisation R D. NCCSDO (2004). p. 1–424.

27. Wensing M, Oxman A, Baker R, Godycki-Cwirko M, Flottorp S, Szecsenyi J, et al. Tailored implementation for chronic diseases (TICD): a project protocol. Implement Sci. (2011) 6(1):103. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-103

28. Klein KJ, Sorra JS. The challenge of innovation implementation. Acad Manage Rev. (1996) 21(4):1055–80. doi: 10.2307/259164

29. Rosenstock IM, Strecher VJ, Becker MH. Social learning theory and the health belief model. Health Educ Q. (1988) Summer 15(2):175–83. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500203

30. Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. (2004) 31:143–64. doi: 10.1177/1090198104263660

31. Haines ER, Dopp A, Lyon AR, Witteman HO, Bender M, Vaisson G, et al. Harmonizing evidence-based practice, implementation context, and implementation strategies with user-centered design: a case example in young adult cancer care. Implement Sci Commun. (2021) 2(1):45. doi: 10.1186/s43058-021-00147-4

32. Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC). EPOC Taxonomy. (2015). Available online at: epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-taxonomy. (cited August 29, 2021).

33. Rugs D, Hills HA, Moore KA, Peters RH. A community planning process for the implementation of evidence-based practice. Eval Program Plann. (2011) 34(1):29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2010.06.002

34. Sarkies MN, Bowles KA, Skinner EH, Haas R, Lane H, Haines TP. The effectiveness of research implementation strategies for promoting evidence-informed policy and management decisions in healthcare: a systematic review. Implement Sci. (2017) 12:132. doi: 10.1186/s13012-017-0662-0

35. Grimshaw JM, Thomas RE, Maclennan G, Fraser C. Effectiveness and efficiency of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies HTA health technology assessment NHS R&D HTA programme. Health Technol Assess (Rockv). (2004) 8:iii-72. doi: 10.3310/hta8060

36. Forsetlund L, O’Brien MA, Forsén L, Reinar LM, Okwen MP, Horsley T, et al. Continuing education meetings and workshops: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2021) 2021(9):CD003030. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003030.pub3

37. Chamberlain P, Price J, Reid J, Landsverk J. Cascading implementation of a foster and kinship parent intervention NIH public access. Child Welfare. (2008) 87:27–48.19402358

38. Liu W, Sidhu A, Beacom AM, Valente TW. Social network theory. In: The International Encyclopedia of Media Effects. (2017). Vol. 1. p. 1–12.

39. Scott Tindale R, Loyola University Chicago. Applied social psychology graduate program, society for the psychological study of social issues. Theory and research on small groups. New York: Springer Science+Business Media, Llc (2013). 195–8.

40. Dopp AR, Narcisse MR, Mundey P, Silovsky JF, Smith AB, Mandell D, et al. A scoping review of strategies for financing the implementation of evidence-based practices in behavioral health systems: state of the literature and future directions. Implement Res Pract. (2020) 1:263348952093998. doi: 10.1177/2633489520939980

41. Bartholomew K, Parcel GS, Kok G, Gottlieb NH, Fernández ME. Planning health promotion programs. San Francisco: John Wiley and Sons (2011).

42. Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. 5th edn. New York: Free Press (2003). p. 551. Available online at: https://books.google.nl/books?id=9U1K5LjUOwEC&redir_esc=y (cited July 1, 2019).

43. Ibekwe LN, Walker TJ, Ebunlomo E, Ricks KB, Prasad S, Savas LS, et al. Using implementation mapping to develop implementation strategies for the delivery of a cancer prevention and control phone navigation program: a collaboration with 2-1-1. Health Promot Pract. (2022) 23(1):86–97. doi: 10.1177/1524839920957979

44. Collier S, Semeere A, Byakwaga H, Laker-Oketta M, Chemtai L, Wagner AD, et al. A type III effectiveness-implementation hybrid evaluation of a multicomponent patient navigation strategy for advanced-stage Kaposi’s sarcoma: protocol. Implement Sci Commun. (2022) 3(1):50. doi: 10.1186/s43058-022-00281-7

45. Cooper BR, Hill LG, Parker L, Jenkins GJ, Shrestha G, Funaiole A. Using qualitative comparative analysis to uncover multiple pathways to program sustainment: implications for community-based youth substance misuse prevention. Implement Sci Commun. (2022) 3(1):55. doi: 10.1186/s43058-022-00303-4

46. Nilsen P, Bernhardsson S. Context matters in implementation science: a scoping review of determinant frameworks that describe contextual determinants for implementation outcomes. BMC Health Serv Res. (2019) 19:189. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4015-3

47. Wensing M. The tailored implementation in chronic diseases (TICD) project: introduction and main findings. Implement Sci. (2017) 12(1):5. doi: 10.1186/s13012-016-0536-x

48. Baker R, Camosso-Stefinovic J, Gillies C, Shaw EJ, Cheater F, Flottorp S, et al. Tailored interventions to address determinants of practice. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2015) 2015:CD005470. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008366.pub3

49. Lewis CC, Klasnja P, Powell BJ, Lyon AR, Tuzzio L, Jones S, et al. From classification to causality: advancing understanding of mechanisms of change in implementation science. Front Public Health. (2018) 6:136. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00136

50. Chambers DA, Glasgow RE, Stange KC. The dynamic sustainability framework: addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implement Sci. (2013) 8(1):117. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-117

Assessing the context: Conducting local needs assessment was described as a strategy for the internal and external contexts. In addition, assessing readiness and identifying barriers and facilitators were strategies that align with theme internal context.

Network internally: Building a coalition, promoting network weaving, and organizing implementation team meetings were strategies assigned to theme network internally. The theme reflects mostly on the CFIR construct network and communication. However, the construct readiness for implementation also aligns with the theme with the corresponding strategy, “build a coalition.”

Network externally: Cosmopolitanism, e.g., working with other organizations, is the only construct assigned to theme network externally. Strategies concerning network externally were relatively similar to those concerning network internally. However, it is executed in different levels of the context and focuses on building and enhancing external collaboration with stakeholders. Therefore, actions described for the strategies in theme network externally are different from those described for network internally.

Costs: Theme costs reflect mostly on the construct intervention characteristics. Also, construct implementation climate is related to this theme, as insufficient time (and money) for the implementation process itself was identified as a barrier to implementation.

Knowledge: Strategies concerning theme knowledge reflect multiple levels within the implementation. Actions related to knowledge, such as materials, are described for stakeholders, recipients of the intervention, and healthcare professionals delivering the intervention. The strategies in theme knowledge relate to constructs “knowledge and beliefs about the intervention,” “design quality and packaging,” “engaging,” and “other personal attributes.”

Champions: Theme champions was linked to one strategy, addressing three constructs. Within the description of the strategies, a champion is mostly named as an actor. Because champions were named as actors for a great number of strategies and were found to have a major role in implementation, the theme champions should be incorporated into the other themes.

Patient needs and resources: More strategies addressed patient needs compared to the other themes. Most strategies in this theme were derived from other literature works concerning behavioral change. Moreover, many healthcare professionals proposed strategies that could be integrated into the intervention, for example, setting goals and motivational interviewing.

Keywords: implementation, strategies, methodology, lifestyle intervention, older adults, codesign, Implementation Strategy Mapping Method, primary care

Citation: van der Laag PJ, Dorhout BG, Heeren AA, Veenhof C, Barten Di-Janne JA and Schoonhoven L (2024) Identification and development of implementation strategies: the important role of codesign. Front. Health Serv. 4:1305955. doi: 10.3389/frhs.2024.1305955

Received: 2 October 2023; Accepted: 12 January 2024;

Published: 7 February 2024.

Edited by:

Xiaolin Wei, University of Toronto, CanadaReviewed by:

Ucheoma Catherine Nwaozuru, Wake Forest University, United States© 2024 van der Laag, Dorhout, Heeren, Veenhof, Barten and Schoonhoven. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Patricia J. van der Laag cC5qLnZhbmRlcmxhYWctM0B1bWN1dHJlY2h0Lm5s

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.