- 1Hunter New England Population Health, Hunter New England Area Health Service, Newcastle, NSW, Australia

- 2School of Medicine and Public Health, The University of Newcastle, Newcastle, NSW, Australia

- 3Priority Research Centre for Health Behaviour, The University of Newcastle, Newcastle, NSW, Australia

- 4Hunter Medical Research Institute, New Lambton Heights, Newcastle, NSW, Australia

- 5Center for Mental Health Services Research, Brown School, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO, United States

- 6Division of Infectious Diseases, John T. Milliken Department of Medicine, Washington University School of Medicine, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO, United States

- 7Center for Dissemination and Implementation, Institute for Public Health, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO, United States

- 8Department of Sociomedical Sciences, Columbia University, Mailman School of Public Health, New York, NY, United States

- 9Women's College Hospital Institute for Health System Solutions and Virtual Care, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 10Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 11Department of Obstetrics, Gynaecology and Reproductive Biology, College of Human Medicine, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, United States

- 12School of Health Science, Swinburne University of Technology, Hawthorn, VIC, Australia

- 13Department of Psychology, Eastern Michigan University, Ypsilanti, MI, United States

Background: Sustainability science is an emerging area within implementation science. There is limited evidence regarding strategies to best support the continued delivery and sustained impact of evidence-based interventions (EBIs). To build such evidence, clear definitions, and ways to operationalize strategies specific and/or relevant to sustainment are required. Taxonomies and compilations such as the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) were developed to describe and organize implementation strategies. This study aimed to adapt, refine, and extend the ERIC compilation to incorporate an explicit focus on sustainment. We also sought to classify the specific phase(s) of implementation when the ERIC strategies could be considered and applied.

Methods: We used a two-phase iterative approach to adapt the ERIC. This involved: (1) adapting through consensus (ERIC strategies were mapped against barriers to sustainment as identified via the literature to identify if existing implementation strategies were sufficient to address sustainment, needed wording changes, or if new strategies were required) and; (2) preliminary application of this sustainment-explicit ERIC glossary (strategies described in published sustainment interventions were coded against the glossary to identify if any further amendments were needed). All team members independently reviewed changes and provided feedback for subsequent iterations until consensus was reached. Following this, and utilizing the same consensus process, the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation and Sustainment (EPIS) Framework was applied to identify when each strategy may be best employed across phases.

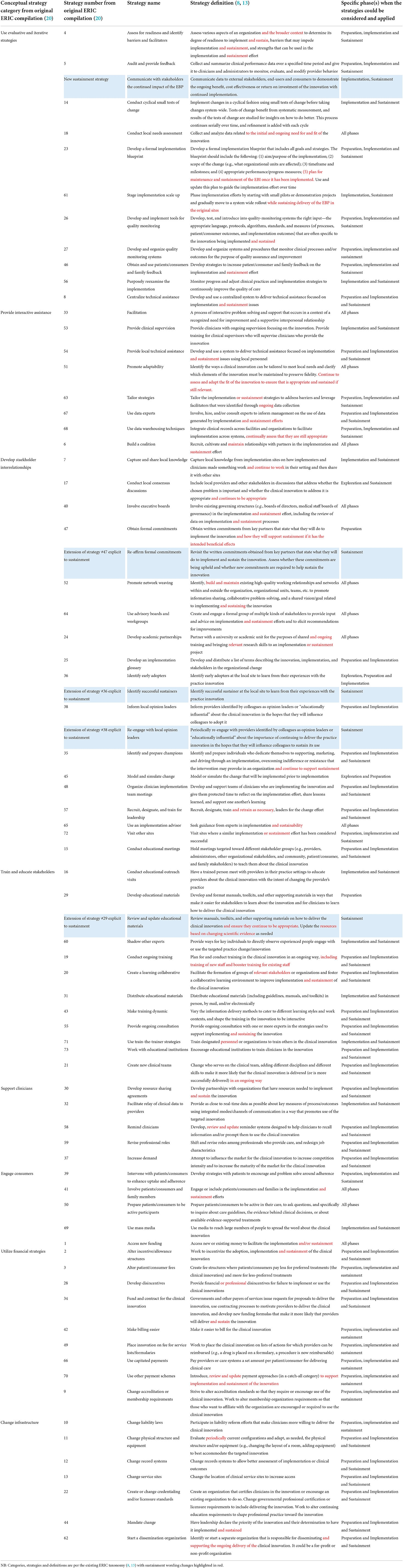

Results: Surface level changes were made to the definitions of 41 of the 73 ERIC strategies to explicitly address sustainment. Four additional strategies received deeper changes in their definitions. One new strategy was identified: Communicate with stakeholders the continued impact of the evidence-based practice. Application of the EPIS identified that at least three-quarters of strategies should be considered during preparation and implementation phases as they are likely to impact sustainment.

Conclusion: A sustainment-explicit ERIC glossary is provided to help researchers and practitioners develop, test, or apply strategies to improve the sustainment of EBIs in real-world settings. Whilst most ERIC strategies only needed minor changes, their impact on sustainment needs to be tested empirically which may require significant refinement or additions in the future.

Introduction

Over the last two decades, research investment in, and application of, implementation science theories, frameworks and methods has resulted in significant improvements in the initial implementation of evidence-based interventions (EBIs) in both clinical and community settings (1–3). Key to advancing the field has been the concerted efforts, particularly in the last few years, to identify effective implementation strategies (and the mechanisms through which they operate) (4–7). Implementation strategies are “methods or techniques used to improve the adoption, implementation, sustainment and scale-up of interventions.” (3, 8), Systematic reviews of implementation trials have assessed the impact implementation strategies have had on the adoption and implementation of EBIs in real world settings (2, 3, 9–11).

Poor and inconsistent reporting of implementation strategies has been a longstanding issue for the field (8). Historically, the language used to define implementation strategies has been inconsistent and highly variable (12, 13), with different terms used to describe the same strategy or the same terms being used to define different strategies (13, 14). Consequently, descriptions of implementation strategies have lacked the necessary detail required for an adequate understanding of the exact nature, function, and make-up of an implementation intervention (i.e., combination of one or more implementation strategies used to support the delivery of an evidence-based practice, program or intervention) (12, 14–16). Such information is essential for scientific advancement, as it allows for replication in advancing the science and improvements of previous research, as well as for scale-up and translation of effective strategies into practice beyond the initial site (14). These inconsistencies make it difficult to identify core functions of the implementation intervention or the implementation strategies, to synthesize research findings, and ultimately identify the active components of a particular implementation intervention. This problem is especially true for complex, multicomponent implementation interventions such as those typically employed in clinical and public health (14).

The introduction and application of taxonomies or compilations of implementation strategies and behavior change techniques is one approach that has been used to address such issues (12, 13, 17–20). Compilations standardize the naming and definitions of implementation strategies, enabling implementation interventions to be described in a consistent manner. A number of implementation-specific taxonomies and compilations have been developed to standardize and clarify the classification and reporting of implementation strategies (8, 11, 13, 17–19). The Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) compilation (8, 13) has been widely used in health and public health and has provided much-needed common terminology for implementation strategies. Developed and refined by implementation experts, the compilation shows high face validity and consists of 73 strategies grouped into nine categories (see Table 1) (21).

Table 1. Sustainment-explicit expert recommendations for implementing change (ERIC) (8–13) glossary.

Sustainability research has been identified as a priority area within implementation science (8). Sustainability has been defined as “(1) after a defined period of time, (2) the program, clinical intervention, and/or implementation strategies continue to be delivered and/or (3) individual behavior change (i.e., clinician, patient) is maintained; (4) the program and individual behavior change may evolve or adapt while (5) continuing to produce benefits for individuals/systems” (22). A 2020 review by Moullin et al. (23) did however highlight that a number of other conceptual distinctions have been made in the field, particularly in relation to sustainment that is the “sustained use of an EBI” vs. sustainability the “sustained benefits of an EBI.” The sustainment of EBIs is critical as premature ceasing of EBIs may mean that the potential public health and clinical healthcare benefits cease or may not be achieved (24). Additionally, if EBIs are not sustained there is a significant waste of public health and clinical resources utilized for initial implementation which may have implications for reducing trust of research/academic institutions (24–26).

Whilst there is growing research focused on sustainment as an outcome (27) including consideration of specific factors (24, 27–31) associated with sustainment that may be distinct from those that matter for implementation (32, 33) the field is bereft of evidence of the most effective strategies to support the sustainment of EBIs (24, 27). A 2019 review of strategies used to sustain public health interventions identified only six studies that purposefully set out to sustain an EBI (27). Overall only nine sustainment strategies were reported with “ongoing funding,” “booster training,” “supervision and feedback” being the most frequently reported. However, there was insufficient evidence to determine the effectiveness of any one strategy in impacting sustainment. The review reported that most strategies were inadequately described providing very little detail which would enable replication. Such vague and incomplete descriptions of strategies is a limitation of the current evidence base, and highlights the need for a compilation that adequately addresses strategies that support sustainment to ensure they are consistently defined and reported. The review also emphasized the importance of sustainment being considered from the outset of a project and the need for identifying sustainment-focused strategies during the planning of an EBI. Furthermore, strategies relevant to early phases of the initial implementation process are also likely to hold relevance and lay the foundation for longer-term sustainment. However, there is currently no guidance on which strategies should be enacted, and at which phases, to best sustain an EBI.

Given that there are existing compilations for implementation strategies, it is possible that they could be extended or clarified to specifically address sustainment. However key to designing future interventions is the selection of strategies which best addresses the contextual determinants i.e., the barriers and facilitators that impede or promote (4) the sustainment of EBIs (34). While there may be some overlap with the barriers and facilitators to adoption, implementation, and sustainment of EBIs (e.g., organizational culture and resources), it is likely that there are also barriers and facilitators to sustainment of EBIs (e.g., changes in socio-political environment and funding structures) that may be distinct (35). Existing compilations may therefore be lacking in identifying and describing strategies that are specific to and necessary for sustaining an EBI. It is however acknowledged that the sustainment of an EBI is inextricably impacted by strategies selected during the previous adoption and or implementation phases (36, 37). For example, the sustainment of an EBI may be hindered if the adoption and implementation phase has relied on researchers to deliver the intervention, without consideration given to the infrastructure needed to deliver the EBI once research funding ends. Therefore, strategies for the sustainment of EBIs should be considered and planned for in unison with strategies for implementation for any progress to be made in this area. To do this compilations of implementation strategies could specifically incorporate issues relevant to sustainment. This may include updating existing implementation strategies to directly address sustainment or including new strategies that target sustainment-specific barriers and facilitators. Furthermore, whilst frameworks such as the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) (38) are useful to identify what factors may influence sustainment they do not address how or when change needs to occur (39). Therefore if we are to plan for sustainment at the beginning of implementation efforts, as has been recommended (36), direction on which strategies need to be employed during which phase of the implementation process is needed.

This research is still in its infancy, and there is an opportunity to establish the use of a compilation of sustainment strategies to allow for consistent reporting and, ultimately, empirical testing. As it is likely that sustainment strategies need to be considered during all phases of implementation, extending an existing compilation of implementation strategies that is already widely used, is likely to support the consideration of sustainment at appropriate phases of implementation and avoid unnecessary duplication. Thus, the aim of this study is to adapt, refine and extend an existing compilation of implementation strategies (ERIC) (13, 21) to explicitly incorporate sustainment, as well as specify the phases of implementation that such strategies are likely to be most salient according to the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation and Sustainment (EPIS) (40) framework.

Materials and methods

Adapting and extending the ERIC compilation to incorporate sustainment

A two-phase iterative approach to adapt the ERIC compilation to include sustainment was undertaken, based on procedures similar to those previously used in the development (41) or adaptation (42) of ERIC or other taxonomies. This involved:

Adapting and extending through consensus

Consistent with other approaches to developing and extending the ERIC compilation (13, 21, 42), we convened a team of 11 researchers, policy-makers, and practitioners (co-authors of this paper) from Australia, Canada and The United States, who undertook an iterative process of reviewing and adapting the current compilation to incorporate strategies specific to sustainment. For the purpose of this study we defined sustainment as “the sustained use or delivery of an intervention in practice following cessation of external implementation support” (26, 36). The team are experts in implementation and or sustainability science, and or health service delivery, and included two of the original authors of the ERIC compilation (BP and TW) an expert on the conceptual distinction of ERIC strategies (13, 21, 34). Both BP and TW have adapted the ERIC for specific contexts (42, 43). In order to adapt and extend the ERIC the following steps were undertaken.

Step 1: Barriers to sustainment

We first identified barriers to sustainment from existing studies. These nine publications (27–29, 44–49) were found through snowballing for literature of “barriers to sustainment” which a research assistant extracted into an excel spreadsheet.

Step 2: Mapping ERIC strategies to address key barriers

To help identify where wording changes may be needed or where additional strategies may need to be created two authors (AH and NN) independently mapped these barriers to existing ERIC strategies. Where the authors felt that a barrier could not be adequately linked to an existing ERIC strategy, they independently drafted proposed wording changes to an existing strategy or identified if a new strategy was needed. The two authors then met to discuss coding, suggested wording changes and or new strategies until they reached consensus. A third author (BP) then reviewed, provided feedback and then met with AH and NN to discuss revisions until consensus was reached.

Step 3: Iterative consensus process

Following completion of Step 2 all team members were asked to independently review the suggested wording changes and the proposed new strategies developed by AH, NN and BP. They were specifically asked to review and document any edits they believe should be made, or any disagreements they had with the current suggestions, along with detail of their reasoning. After each iteration AH and NN reviewed all feedback. Where there were instances of disagreement between authors they met to develop a proposed amendment and circulated this to all authors for their review. This process of review and updating by the entire team continued for three rounds until consensus was reached.

Preliminary application of the sustainment-explicit glossary

Following the above, the authors undertook a preliminary test of the application and logic of the sustainment-explicit ERIC glossary to determine its ease of application in the field of sustainment, and if any further adaptions or amendments were needed. As this is still an emerging field to identify potential trials which have employed sustainment strategies we reviewed the National Institutes of Health (NIH) database of trials funded in 2019. We also searched the table of contents of the leading implementation science journals, which included: Implementation Science, Implementation Science Communications, and Frontiers in Public Health for sustainment interventions published between 2018 and 2020. Overall, 12 trials or protocols were identified. As our goal was to check the logic of our proposed adaptation we randomly selected a small number of these studies (n = 6) to test the sustainment-explicit glossary. Two authors (AH and NN) independently coded the strategies described in those publications against those in the sustainment-explicit ERIC glossary. The authors then compared coding to identify areas of confusion, disagreement, or if any additional strategies emerged. This process was designed to identify where updates were needed to improve the content or wording of the glossary and ensure feasibility in its application. The final glossary was reviewed and agreed on by all authors involved.

Implementation phase and strategy utility

To help researchers and practitioners identify when they might consider employing each strategy, we categorized each strategy against the phase(s) of implementation according to the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation and Sustainment (EPIS) Framework (37). To complete this categorization, the same iterative process described above was followed. EPIS was selected as a guiding taxonomy, as it is a widely used and provides clear definitions for each phase. Definitions of the EPIS as defined by the developers (40) were provided to co-authors to help them code the ERIC strategy to the EPIS phase(s).

Results

The sustainment explicit ERIC glossary is presented in Table 1.

Adapting ERIC definitions

Of the 73 ERIC strategies, the definitions of 45 were amended to make sustainment more explicit. For the majority (n = 41) this involved minor surface level changes to include the words “sustainment” or “sustainability.” For example, the definition of “Centralized Technical Assistance” was changed to “develop and use a centralized system to deliver technical assistance focused on implementation and sustainment issues.” Other surface level changes to definitions were more elaborative. For example, the definition of “Promote Adaptability” was changed to “Identify the ways a clinical innovation can be tailored to meet local needs and clarify which elements of the innovation must be maintained to preserve fidelity. Continue to assess and adapt the fit of the innovation to ensure that it is appropriate and sustained if still relevant.”

The other four strategies where adaptations were made were identified as being in need of slightly deeper level adaptations. These deeper level adaptations were extensions of existing strategies and reflect changes made to the substance of the definition (42), to specifically encompass issues of sustainment, typically because the original definition more explicitly focused on the application of the strategy at an earlier phase of implementation. For example Obtain formal commitments (strategy 47) was defined as “Obtain written commitments from key partners that state what they will do to implement the innovation and how they will support sustainment if it has the intended beneficial effects” however it was acknowledged that this didn't accurately capture a key barrier to sustainment in regards to ongoing support or decisions around continuation. Accordingly Re-affirm formal commitments (an extension of strategy 47) was added which was defined as “Revisit the written commitments obtained from key partners that state what they will do to implement and sustain the innovation. Assess whether these commitments are being upheld and whether new commitments are required to help sustain the innovation.” The additional strategies are: Review and update educational materials (extension of strategy 29); Identify successful sustainers (extension of strategy 36); Re-engage with local opinion leaders (extension of strategy 38); Re-affirm formal commitments (extension of strategy 47). See Table 1 for the detailed definitions of these strategies.

Novel sustainment strategies

One new sustainment focused strategy was identified: Communicate with stakeholders the continued impact of the EBP. This strategy takes the information obtained from Audit and provide feedback and/or Develop and organize quality monitoring systems strategies and communicates data to external stakeholders, end-users, and consumers to demonstrate the ongoing benefit, cost effectiveness, or return on investment of the innovation with continued implementation. Conceptually, this strategy seems to fit within the ERIC Use evaluative and iterative strategies cluster (21).

Preliminary application of the sustainment-explicit ERIC glossary

Application of the sustainment-explicit ERIC identified wide variation in detail and language used to describe the specific strategies employed in the reviewed studies. Consequently, following the initial independent review by the two authors, a thorough discussion and joint application was undertaken to help identify any gaps or areas in need of improvement in the compilation. No new strategies were identified through the coding of published sustainment trials or manuscripts that needed to be considered for inclusion in the glossary. Minor wording changes were made to help clarify some of the strategies and how they relate to sustainment to ensure consistency in interpretation and application.

Implementation phase and strategy utility

Table 1 shows that the majority of strategies (n = 44) were identified as being relevant for consideration during three of the four phases of the EPIS Framework, with 43 of the 44 likely to be needed during preparation, implementation and sustainment phases. Only five strategies were identified as being only relevant during the sustainment phase, which were the four that received deeper levels of adaptation to focus on sustainment (noted above) as well as the novel strategy (also noted above). Thus, majority of existing ERIC strategies were viewed as relevant for more than one EPIS phase, including sustainment.

Discussion

This is one the first of studies to systematically evaluate an existing compilation of implementation strategies for their relevance for supporting the sustainment of evidence-based programs. The two-phase iterative approach resulted in superficial wording changes to the definitions of 41 of the 73 existing ERIC strategies, slightly deeper wording changes to four ERIC strategies, and the addition of one new strategy. The study also provides guidance to researchers and implementation support practitioners looking to design implementation or sustainment interventions by identifying the phase, according to EPIS framework, when the strategy may need to be considered and employed. It is hoped that a sustainment-explicit glossary based on an existing compilation of implementation strategies will encourage and support those undertaking implementation research to explicitly consider sustainment from the outset and to use a common language when planning and describing their research and practice.

Whilst others have adapted or applied the ERIC compilation to be relevant to a particular setting (42) or class of interventions (50), or to advance understanding of a particular subset of strategies (51), our sustainment-explicit ERIC glossary required minimal changes. We were able to include sustainment concepts by making no changes to strategy names, minimal modifications to definitions and identified only one new strategy. Our extensive mapping exercise of the ERIC strategies to known barriers and facilitators of sustainment from a broad range of studies in clinical and community settings (27–29, 44–49) and sustainability frameworks (24, 36, 52), ensured that we were adequately capturing strategies specific to addressing the main barriers to sustainment.

The preliminary application of the glossary further highlighted the lack of standardized reporting that is already emerging within the sustainment literature. Of the studies reviewed (n = 6), many of the strategies utilized were not adequately described in enough detail, or were hard to disentangle from other strategies, which would make it difficult for any future studies wishing to synthesize the effects of these strategies. To avoid the challenges that this has caused historically in the field of implementation science, we implore those planning, or currently undertaking, sustainment research to use consistent terminology to describe their chosen strategies, particularly when multiple strategies are used. Furthermore, as recommended by Michie and Johnston (53) for implementation interventions, we encourage trialists to describe these strategies with sufficient detail in terms of “what,” “who,” “when,” “where” and “how,” so these components of each strategy can be sufficiently understood and replicated by others. Frameworks such as those developed by Proctor et al. (8) or Presseau et al. (54) provide useful guidance for specifying this behavior (in the context of implementation and sustainment interventions) (1). If strategies addressing sustainment are consistently described in future research trials this will enable replication studies to be undertaken and study findings synthesized to identify effective strategies or combinations of strategies, and the optimal timing of their delivery, all of which will enhance the design of future sustainment interventions. Whilst the sustainment-explicit ERIC glossary captures all strategies previously identified (27), as evidence in the field continues to grow there may be a need for new strategies to be added. Therefore, this glossary will need to be continuously refined to maintain its utility in sustainment research.

Our application of the EPIS Framework found that a large majority of strategies should be considered during the design and earlier phases of implementation. This is consistent with others who have advocated that implementation and sustainment are interconnected and therefore need to be planned for in advance (55–58). This is also supported by more recent sustainability frameworks such as the Dynamic Sustainability Framework or the RE-AIM extension for sustainment which posits sustainability is not “static,” but rather dynamic, impacted by the changing context in which the intervention is being delivered, the evolving scientific evidence, and the dynamic needs of a population. In a recent study the original developers of the ERIC assessed which strategies experts perceived as being most essential for implementation of three high priority mental health care practices in the US Department of Veteran Affairs (43). The authors found that experts consistently selected a similar set of ERIC strategies as essential for implementation success, regardless of type of EBI (43) or implementation phase. Again, this study highlights the interconnectedness of sustainment with the earlier phases of implementation, and how strategies can be perceived as relevant across the different implementation phases. Shelton et al. (36) suggests that in planning for sustainability, monitoring the reach, adoption, effectiveness and implementation of an EBI is essential to identify early on when challenges are arising and if and how strategies can be adapted, refined, or introduced to support the sustainment of the EBI and address health inequities that may be exacerbated over time.

Robust and valid frameworks or theories specific to sustainability such as the Dynamic Sustainability Framework (52) or the Integrated Sustainability Framework (24) should be employed alongside the sustainment-explicit ERIC glossary, when planning sustainment trials. These frameworks and theories will help identify issues specific to sustainment that should be addressed by any strategies being developed and evaluated (59). Unfortunately, a large proportion of sustainability research is not based on relevant theories, frameworks, or models and for those studies that have, there is wide variation and limited validity in the theories and frameworks commonly applied (59). There is significant need for sustainability research to evaluate the application of sustainability frameworks alongside a compilation such as ERIC (60). This is important if we are to identify how or why strategies impacting sustainment exert their effects (i.e., the mechanisms through which they work) (6). Once this is known we may improve the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of future interventions by keeping, strengthening, adding or removing strategies that target (or don't) mediators which lead to improvements in sustained implementation (5, 61).

There are several limitations to this study. First, unlike the methods used to develop the original ERIC compilation, we only had a small number of implementation and sustainability experts (n = 11) convened to specifically work on this project. Whilst we represented community and clinical perspectives from various countries to gain a broader perspective on this issue, a larger, more diverse, group of experts should further review and revise this glossary for use in sustainment-focused work. Second, we only tested the application of the glossary with a small number of studies. This was undertaken as to test the logic of the amendments; it was not designed to be an extensive application of the sustainment-explicit ERIC or to identify what strategies are being used in sustainment trials. Accordingly, this glossary has not been extensively tested, further application and review of this glossary is needed and welcomed and through its use, it may be evident that further updates are required. Finally, ongoing work is needed to assess the extent to which the sustainment-explicit ERIC glossary is relevant to low- and middle-income countries (62), as this study did not explicitly address this question.

Conclusions

The sustainment-explicit ERIC glossary addresses the need for explicit and clear definitions of strategies to be used in sustainment interventions. The application of relevant strategies during planning and implementation phases may subsequently enhance the evidence-base for the field, and ultimately the sustainment, spread and scale of interventions and improvements in our communities health (63). Future work is needed to empirically test the effectiveness of these strategies in sustaining EBIs in clinical and community settings.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

NN obtained funding for the study. NN, AH, BP, and LW conceived the study concept and developed the study design. NN and AH undertook initial adaptations of the ERIC and classification against EPIS. BP and TW provided expert advice as original developers of ERIC. RCS, CL, LW, MH, SY, RS, and MK advised on and undertook the adaption, extension, consensus process, and pilot testing of the tool. NN and AH developed the draft manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project is funded through the NHMRC as part of NN's Medical Research Future Fund (MRFF) Investigator Grant (GS2000053), BP is supported in part through the U.S. National Institutes of Health (K01MH113806, R01CA262325, P50CA19006, and P50MH126219) and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R13HS025632), RS is supported by an NHMRC Medical Research Future Fund (MRFF) Investigator Grant (G2000052), LW is supported by an NHMRC Investigator Grant (G1901360), and SY is supported by an ARC DECRA (G1600359). The funders had no role in the study design, conduct of the study, analysis, or dissemination of findings.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

EBI, Evidence Based Intervention; EBP, Evidence Based Practice; EPIS, Exploration, Preparation, Implementation and Sustainment; ERIC, Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change.

References

1. Wolfenden L, Foy R, Presseau J, Grimshaw JM, Ivers NM, Powell BJ, et al. Designing and undertaking randomised implementation trials: guide for researchers. BMJ. (2021) 372:m3721. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3721

2. Barnes C, McCrabb S, Stacey F, Nathan N, Yoong SL, Grady A, et al. Improving implementation of school-based healthy eating and physical activity policies, practices, and programs: a systematic review. Transl Behav Med. (2021) 11:1365–410. doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibab037

3. Powell BJ, Fernandez ME, Williams NJ, Aarons GA, Beidas RS, Lewis CC, et al. Enhancing the impact of implementation strategies in healthcare: a research agenda. Front Public Health. (2019) 7:3. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00003

4. Lewis CC, Boyd MR, Walsh-Bailey C, Lyon AR, Beidas R, Mittman B, et al. A systematic review of empirical studies examining mechanisms of implementation in health. Implement Sci. (2020) 15:21. doi: 10.1186/s13012-020-00983-3

5. Lee H, Hall A, Nathan N, Reilly KL, Seward K, Williams CM, et al. Mechanisms of implementing public health interventions: a pooled causal mediation analysis of randomised trials. Implement Sci. (2018) 13:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s13012-018-0734-9

6. Lewis CC, Powell BJ, Brewer SK, Nguyen AM, Schriger SH, Vejnoska SF, et al. Advancing mechanisms of implementation to accelerate sustainable evidence-based practice integration: protocol for generating a research agenda. BMJ Open. (2021) 11:e053474. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-053474

7. Geng EH, Baumann AA, Powell BJ. Mechanism mapping to advance research on implementation strategies. PLoS Med. (2022) 19:e1003918. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003918

8. Proctor EK, Powell BJ, McMillen JC. Implementation strategies: recommendations for specifying and reporting. Implement Sci. (2013) 8:139. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-139

9. Wolfenden L, Goldman S, Stacey FG, Grady A, Kingsland M, Williams CM, et al. Strategies to improve the implementation of workplace-based policies or practices targeting tobacco, alcohol, diet, physical activity and obesity. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. (2018) 11:CD012439. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012439.pub2

10. Wolfenden L, Jones J, Williams CM, Finch M, Wyse RJ, Kingsland M, et al. Strategies to improve the implementation of healthy eating, physical activity and obesity prevention policies, practices or programmes within childcare services. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2016) 10:Cd011779. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011779.pub2

11. Effective Practice Organisation of Care (EPOC). EPOC Taxonomy. (2015). Available online at: http://www.epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-taxonomy (accessed December 15, 2021).

12. Mazza D, Bairstow HP, Buchan Chakraborty SP, Van Hecke O, Grech C, et al. Refining a taxonomy for guideline implementation: results of an exercise in abstract classification. Implement Sci. (2013) 8:32. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-32

13. Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, Damschroder LJ, Smith JL, Matthieu MM, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. (2015) 10:21. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1

14. Michie S, Fixsen D, Grimshaw JM, Eccles MP. Specifying and reporting complex behaviour change interventions: the need for a scientific method. Implement Sci. (2009) 4:40. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-40

15. Lengnick-Hall R, Stadnick NA, Dickson KS, Moullin JC, Aarons GA. Forms and functions of bridging factors: specifying the dynamic links between outer and inner contexts during implementation and sustainment. Implement Sci. (2021) 16:34. doi: 10.1186/s13012-021-01099-y

16. McIntyre SA, Francis JJ, Gould NJ, Lorencatto F. The use of theory in process evaluations conducted alongside randomized trials of implementation interventions: a systematic review. Transl Behav Med. (2020) 10:168–78. doi: 10.1093/tbm/iby110

17. Slaughter SE, Zimmermann GL, Nuspl M, Hanson HM, Albrecht L, Esmail R, et al. Classification schemes for knowledge translation interventions: a practical resource for researchers. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2017) 17:161. doi: 10.1186/s12874-017-0441-2

18. Kok G, Gottlieb NH, Peters GJ, Mullen PD, Parcel GS, Ruiter RA, et al. A taxonomy of behaviour change methods: an Intervention Mapping approach. Health Psychol Rev. (2016) 10:297–312. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2015.1077155

19. Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, Abraham C, Francis J, Hardeman W, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med. (2013) 46:81–95. doi: 10.1007/s12160-013-9486-6

20. McHugh S, Presseau J, Luecking CT, Powell BJ. Examining the complementarity between the ERIC compilation of implementation strategies and the behaviour change technique taxonomy: a qualitative analysis. Implementat Sci. (2022) 17:56. doi: 10.1186/s13012-022-01227-2

21. Waltz TJ, Powell BJ, Matthieu MM, Damschroder LJ, Chinman MJ, Smith JL, et al. Use of concept mapping to characterize relationships among implementation strategies and assess their feasibility and importance: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) study. Implement Sci. (2015) 10:109. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0295-0

22. Moore JE, Mascarenhas A, Bain J, Straus SE. Developing a comprehensive definition of sustainability. Implement Sci. (2017) 12:110. doi: 10.1186/s13012-017-0637-1

23. Moullin JC, Sklar M, Green A, Dickson KS, Stadnick NA, Reeder K, et al. Advancing the pragmatic measurement of sustainment: a narrative review of measures. Implement Sci Commun. (2020) 1:76. doi: 10.1186/s43058-020-00068-8

24. Shelton RC, Cooper BR, Stirman SW. The sustainability of evidence-based interventions and practices in public health and health care. Annu Rev Public Health. (2018) 39:55–76. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-014731

25. Wiltsey Stirman S, Kimberly J, Cook N, Calloway A, Castro F, Charns M. The sustainability of new programs and innovations: a review of the empirical literature and recommendations for future research. Implement Sci. (2012) 7:17. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-17

26. Scheirer MA, Dearing JW. An agenda for research on the sustainability of public health programs. Am J Public Health. (2011) 101:2059–67. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300193

27. Hailemariam M, Bustos T, Montgomery B, Barajas R, Evans LB, Drahota A. Evidence-based intervention sustainability strategies: a systematic review. Implementat Sci. (2019) 14:57. doi: 10.1186/s13012-019-0910-6

28. Shoesmith A, Hall A, Wolfenden L, Shelton RC, Powell BJ, Brown H, et al. Barriers and facilitators influencing the sustainment of health behaviour interventions in schools and childcare services: a systematic review. Implement Sci. (2021) 16:62. doi: 10.1186/s13012-021-01134-y

29. Cowie J, Nicoll A, Dimova ED, Campbell P, Duncan EA. The barriers and facilitators influencing the sustainability of hospital-based interventions: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. (2020) 20:588. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05434-9

30. Hodge LM, Turner KM. Sustained implementation of evidence-based programs in disadvantaged communities: a conceptual framework of supporting factors. Am J Community Psychol. (2016) 58:192–210. doi: 10.1002/ajcp.12082

31. Hall A, Shoesmith A, Shelton RC, Lane C, Wolfenden L, Nathan N. Adaptation and Validation of the Program Sustainability Assessment Tool (PSAT) for Use in the Elementary School Setting. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:11414. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182111414

32. McFadyen T, Wolfenden L, Kingsland M, Tindall J, Sherker S, Heaton R, et al. Sustaining the implementation of alcohol management practices by community sports clubs: a randomised control trial. BMC Public Health. (2019) 19:1660. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7974-8

33. Nathan N, Hall A, McCarthy N, Sutherland R, Wiggers J, Bauman AE, et al. Multi-strategy intervention increases school implementation and maintenance of a mandatory physical activity policy: outcomes of a cluster randomised controlled trial. Br J Sports Med. (2022) 56:385–93. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2020-103764

34. Waltz TJ, Powell BJ, Fernández ME, Abadie B, Damschroder LJ. Choosing implementation strategies to address contextual barriers: diversity in recommendations and future directions. Implementat Sci. (2019) 14:42. doi: 10.1186/s13012-019-0892-4

35. Shelton RC, Dunston SK, Leoce N, Jandorf L, Thompson HS, Crookes DM, et al. Predictors of activity level and retention among African American lay health advisors (LHAs) from The National Witness Project: Implications for the implementation and sustainability of community-based LHA programs from a longitudinal study. Implement Sci. (2016) 11:41. doi: 10.1186/s13012-016-0403-9

36. Shelton RC, Chambers DA, Glasgow RE. An Extension of RE-AIM to enhance sustainability: addressing dynamic context and promoting health equity over time. Front Public Health. (2020) 8:134. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00134

37. Aarons GA, Hurlburt M, Horwitz SM. Advancing a Conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Adm Policy Ment Health. (2011) 38:4–23. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0327-7

38. Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. (2009) 4:50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50

39. Nilsen P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement Sci. (2015) 10:53. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0242-0

40. The EPIS Framework Website. (2016). Available online at: https://episframework.com/what-is-epis (accessed August 09, 2022).

41. Michie S, Ashford S, Sniehotta FF, Dombrowski SU, Bishop A, French DP, et al. refined taxonomy of behaviour change techniques to help people change their physical activity and healthy eating behaviours: the CALO-RE taxonomy. Psychol Health. (2011) 26:1479–98. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2010.540664

42. Cook CR, Lyon AR, Locke J, Waltz T, Powell BJ. Adapting a Compilation of Implementation Strategies to Advance School-Based Implementation Research and Practice. Prev Sci. (2019) 20:914–35. doi: 10.1007/s11121-019-01017-1

43. Waltz TJ, Powell BJ, Matthieu MM, Smith JL, Damschroder LJ, Chinman MJ, et al. Consensus on strategies for implementing high priority mental health care practices within the US department of veterans affairs. Implement Res Pract. (2021) 2:26334895211004607. doi: 10.1177/26334895211004607

44. Cassar S, Salmon J, Timperio A, Naylor PJ, van Nassau F, Contardo Ayala AM, et al. Adoption, implementation and sustainability of school-based physical activity and sedentary behaviour interventions in real-world settings: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. (2019) 16:120. doi: 10.1186/s12966-019-0876-4

45. Herlitz L, MacIntyre H, Osborn T, Bonell C. The sustainability of public health interventions in schools: a systematic review. Implementat Sci. (2020) 15:4. doi: 10.1186/s13012-019-0961-8

46. Bodkin A, Hakimi S. Sustainable by design: a systematic review of factors for health promotion program sustainability. BMC Public Health. (2020) 20:964–964. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09091-9

47. Acosta J, Chinman M, Ebener PA, Malone PS, Cannon JS, D'Amico EJ. Sustaining an Evidence-Based Program Over Time: Moderators of Sustainability and the Role of the Getting to Outcomes® Implementation Support Intervention. Prev Sci. (2020) 21:807–19. doi: 10.1007/s11121-020-01118-2

48. Popowich AD, Mushquash AR, Pearson E, Schmidt F, Mushquash CJ. Barriers and facilitators affecting the sustainability of dialectical behaviour therapy programmes: a qualitative study of clinician perspectives. Couns Psychother Res. (2020) 20:68–80. doi: 10.1002/capr.12250

49. Hunter SB, Felician M, Dopp AR, Godley SH, Pham C, Bouskill K, et al. What influences evidence-based treatment sustainment after implementation support ends? A mixed method study of the adolescent-community reinforcement approach. J Substance Abuse Treat. (2020) 113:107999. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2020.107999

50. Graham AK, Lattie EG, Powell BJ, Lyon AR, Smith JD, Schueller SM, et al. Implementation strategies for digital mental health interventions in health care settings. Am Psychol. (2020) 75:1080–92. doi: 10.1037/amp0000686

51. Dopp AR, Narcisse MR, Mundey P, Silovsky JF, Smith AB, Mandell D, et al. A scoping review of strategies for financing the implementation of evidence-based practices in behavioral health systems: State of the literature and future directions. Implementat Res Pract. (2020) 1:2633489520939980. doi: 10.1177/2633489520939980

52. Chambers DA, Glasgow RE, Stange KC. The dynamic sustainability framework: addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implement Sci. (2013) 8:117. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-117

53. Michie S, Johnston M. Changing clinical behaviour by making guidelines specific. BMJ. (2004) 328:343–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7435.343

54. Presseau J, McCleary N, Lorencatto F, Patey AM, Grimshaw JM, Francis JJ. Action, actor, context, target, time (AACTT): a framework for specifying behaviour. Implement Sci. (2019) 14:102. doi: 10.1186/s13012-019-0951-x

55. Pluye P, Potvin L, Denis JL. Making public health programs last: conceptualizing sustainability. Eval Program Plann. (2004) 27:121–33. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2004.01.001

56. Walugembe DR, Sibbald S, Le Ber MJ, Kothari A. Sustainability of public health interventions: where are the gaps? Health Res Policy Syst. (2019) 17:8. doi: 10.1186/s12961-018-0405-y

57. Alidina S, Zanial N, Meara JG, Barash D, Buberwa L, Chirangi B, et al. Applying the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment (EPIS) Framework to Safe Surgery 2020 Implementation in Tanzania's Lake Zone. J Am Coll Surg. (2021) 233:177–191.e175. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2021.04.006

58. Becan JE, Bartkowski JP, Knight DK, Wiley TRA, DiClemente R, Ducharme L, et al. A model for rigorously applying the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment (EPIS) framework in the design and measurement of a large scale collaborative multi-site study. Health Justice. (2018) 6:9–9. doi: 10.1186/s40352-018-0068-3

59. Birken SA, Haines ER, Hwang S, Chambers DA, Bunger AC, Nilsen P. Advancing understanding and identifying strategies for sustaining evidence-based practices: a review of reviews. Implement Sci. (2020) 15:88. doi: 10.1186/s13012-020-01040-9

60. Shelton RC, Lee M, Brotzman LE, Wolfenden L, Nathan N, Wainberg ML. What Is Dissemination and Implementation Science?: An Introduction and Opportunities to Advance Behavioral Medicine and Public Health Globally. Int J Behav Med. (2020) 27:3–20. doi: 10.1007/s12529-020-09848-x

61. Wolfenden L, Bolsewicz K, Grady A, McCrabb S, Kingsland M, Wiggers J, et al. Optimisation: defining and exploring a concept to enhance the impact of public health initiatives. Health Res Policy Syst. (2019) 17:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12961-019-0502-6

62. Brownson RC, Kumanyika SK, Kreuter MW, Haire-Joshu D. Implementation science should give higher priority to health equity. Implement Sci. (2021) 16:28. doi: 10.1186/s13012-021-01097-0

Keywords: sustainability, sustainment, implementation strategies, mechanisms, design and tailoring, implementation science

Citation: Nathan N, Powell BJ, Shelton RC, Laur CV, Wolfenden L, Hailemariam M, Yoong SL, Sutherland R, Kingsland M, Waltz TJ and Hall A (2022) Do the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) strategies adequately address sustainment? Front. Health Serv. 2:905909. doi: 10.3389/frhs.2022.905909

Received: 28 March 2022; Accepted: 30 September 2022;

Published: 03 November 2022.

Edited by:

Erin P. Finley, United States Department of Veterans Affairs, United StatesReviewed by:

Jennifer Sullivan, Brown University, United StatesThomas von Lengerke, Hannover Medical School, Germany

Copyright © 2022 Nathan, Powell, Shelton, Laur, Wolfenden, Hailemariam, Yoong, Sutherland, Kingsland, Waltz and Hall. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nicole Nathan, Tmljb2xlLk5hdGhhbkBoZWFsdGgubnN3Lmdvdi5hdQ==

Nicole Nathan

Nicole Nathan Byron J. Powell

Byron J. Powell Rachel C. Shelton

Rachel C. Shelton Celia V. Laur

Celia V. Laur Luke Wolfenden1,2,3,4

Luke Wolfenden1,2,3,4 Maji Hailemariam

Maji Hailemariam Rachel Sutherland

Rachel Sutherland