94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Health Serv., 31 October 2022

Sec. Implementation Science

Volume 2 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/frhs.2022.1004805

This article is part of the Research TopicSustaining the Implementation of Evidence-Based Interventions in Clinical and Community SettingsView all 15 articles

Asya Agulnik1*

Asya Agulnik1* Gabriella Schmidt-Grimminger2

Gabriella Schmidt-Grimminger2 Gia Ferrara1

Gia Ferrara1 Maria Puerto-Torres1

Maria Puerto-Torres1 Srinithya R. Gillipelli3

Srinithya R. Gillipelli3 Paul Elish4

Paul Elish4 Hilmarie Muniz-Talavera1

Hilmarie Muniz-Talavera1 Alejandra Gonzalez-Ruiz1

Alejandra Gonzalez-Ruiz1 Miriam Armenta5

Miriam Armenta5 Camila Barra6

Camila Barra6 Rosdali Diaz-Coronado7

Rosdali Diaz-Coronado7 Cinthia Hernandez8

Cinthia Hernandez8 Susana Juarez9

Susana Juarez9 Jose de Jesus Loeza10

Jose de Jesus Loeza10 Alejandra Mendez11

Alejandra Mendez11 Erika Montalvo12

Erika Montalvo12 Eulalia Penafiel13

Eulalia Penafiel13 Estuardo Pineda14

Estuardo Pineda14 Dylan E. Graetz1

Dylan E. Graetz1 Virginia McKay2

Virginia McKay2Background: Sustainability, or continued use of evidence-based interventions for long-term patient benefit, is the least studied aspect of implementation science. In this study, we evaluate sustainability of a Pediatric Early Warning System (PEWS), an evidence-based intervention to improve early identification of clinical deterioration in hospitalized children, in low-resource settings using the Clinical Capacity for Sustainability Framework (CCS).

Methods: We conducted a secondary analysis of a qualitative study to identify barriers and enablers to PEWS implementation. Semi-structured interviews with PEWS implementation leaders and hospital directors at 5 Latin American pediatric oncology centers sustaining PEWS were conducted virtually in Spanish from June to August 2020. Interviews were recorded, professionally transcribed, and translated into English. Exploratory thematic content analysis yielded staff perceptions on PEWS sustainability. Coded segments were analyzed to identify participant perception about the current state and importance of sustaining PEWS, as well as sustainability successes and challenges. Identified sustainability determinants were mapped to the CCS to evaluate its applicability.

Results: We interviewed 71 staff including physicians (45%), nurses (45%), and administrators (10%). Participants emphasized the importance of sustaining PEWS for continued patient benefits. Identified sustainability determinants included supportive leadership encouraging ongoing interest in PEWS, beneficial patient outcomes enhancing perceived value of PEWS, integrating PEWS into the routine of patient care, ongoing staff turnover creating training challenges, adequate material resources to promote PEWS use, and the COVID-19 pandemic. While most identified factors mapped to the CCS, COVID-19 emerged as an additional external sustainability challenge. Together, these challenges resulted in multiple impacts on PEWS sustainment, ranging from a small reduction in PEWS quality to complete disruption of PEWS use and subsequent loss of benefits to patients. Participants described several innovative strategies to address identified challenges and promote PEWS sustainability.

Conclusion: This study describes clinician perspectives on sustainable implementation of evidence-based interventions in low-resource settings, including sustainability determinants and potential sustainability strategies. Identified factors mapped well to the CCS, however, external factors, such as the COVID pandemic, may additionally impact sustainability. This work highlights an urgent need for theoretically-driven, empirically-informed strategies to support sustainable implementation of evidence-based interventions in settings of all resource-levels.

Much of implementation science focuses on adopting and implementing evidence-based interventions, and sustainability, or the ongoing use of an evidence-based practice resulting in maintained patient benefits, is the least studied phase of the implementation continuum (1, 2). Ideally, interventions should be sustained unless they are no longer effective or more effective interventions become available (3–5). Many interventions are abandoned when they should be continued, often when external support, such as grant funding or collaborative assistance, is removed (6–9). Implementing interventions is costly, and if interventions are not sustained, then initial investments are lost (10, 11). Most importantly, evidence-based interventions that are not sustained cannot provide continued health benefits to patients.

The current body of scientific literature focuses primarily on conceptualizing and theorizing sustainability in health (11, 12). Sustainability follows successful implementation, typically after external support for an intervention has been withdrawn (13). Similar to contextual factors that impact implementation, a general consensus within the literature establishes the relationship between the immediate context where interventions are implemented and the likelihood of intervention sustainability (12). However, factors impacting the initial implementation of evidence-based interventions are likely not the same as those impacting long-term sustainability. For instance, staff turnover may not impact initial implementation, but is often discussed as a barrier to sustainability.

While there are several conceptual frameworks identifying sustainability determinants, few have guided empiric examinations. The Clinical Capacity for Sustainability Framework (CCS) characterizes the resources needed to successfully sustain an intervention that represent the most proximal contextual determinants influencing intervention sustainment and continued patient benefit (10, 14, 15). Briefly, clinical capacity for sustainability includes engaged staff, leadership and stakeholders, organizational readiness, workflow integration, implementation and training, and monitoring and evaluation (14, 15). This framework was empirically developed, and has subsequently been leveraged to inform measures and tools to assess and plan for intervention sustainability (16).

Sustainable implementation is particularly important in low-resource settings, where resources available for implementation are limited. Low-resource settings experience disproportionate burden of poor health outcomes, making sustainable implementation of evidence-based interventions particularly crucial. However, there are limited examinations of sustainability in these settings; a recent review of determinants of hospital interventions sustainability did not include a single study from a low-income country (17).

The global burden of pediatric cancer is disproportionately shifted to low- and middle-income countries, which bear over 90% of childhood cancer cases (18), with a dismal survival rate of ~20% (19). Hospitals in low-resource settings frequently lack adequate infrastructure and staffing to deliver needed supportive care during cancer treatment (20–23), resulting in late identification of clinical deterioration due to treatment toxicity and high rates of preventable deaths (24–26). To more rapidly identify clinical deterioration, many hospitals use pediatric early warning systems (PEWS), which are nursing-administered bedside clinical acuity scoring tools associated with escalation algorithms (27). PEWS accurately predict the need for pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) transfer in pediatric oncology patients in high-resource hospitals (28–31). Escala de Valoración de Alerta Temprana (EVAT) is a valid Spanish-language PEWS adapted for low-resource settings (32–35), with implementation resulting in a 27% reduction in clinical deterioration events, optimized PICU utilization (33), improved interdisciplinary and family communication, provider empowerment and perceived quality of care (36–39), and an annual cost-savings of over US$350,000 (40).

Proyecto EVAT is a quality improvement collaborative of pediatric oncology centers in Latin America which has supported PEWS implementation in over 40 low-resource hospitals (41), with preliminary results showing improvements in patient outcomes (42–47). Recent work by our team identified multiple barriers to PEWS implementation among centers participating in Proyecto EVAT, with many of these barriers converted to enablers by local implementation teams during the implementation process (48). This work, however, focused primarily on PEWS adoption and implementation, and didn't evaluate factors contributing to PEWS sustainability in participating centers. In this paper, we conduct a secondary analysis of this study using the CSS to evaluate staff perspectives on successes and challenges sustaining PEWS in these low-resource hospitals. We then discuss the utility of the CCS and make recommendations on its use to understand sustainability in real-world clinical settings. Finally, we explore innovative strategies used by hospitals to improve their capacity to sustain PEWS.

This is a secondary analysis of a study designed to evaluate barriers and enablers to PEWS implementation in low-resource hospitals. This study was approved by the St. Jude Children's Research Hospital (St. Jude) institutional review board as minimal risk; additional approvals were obtained locally at participating centers as needed. As an exempt minimal risk study, written consent was waived, and verbal consent was obtained prior to the start of each interview. The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) guidelines were used for rigor of qualitative reporting (49). A detailed description of study methods have been previously described, and are briefly summarized below (48).

Centers participating in Proyecto EVAT who had completed PEWS implementation prior to March 2020 (the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in Latin America) were recruited to this study. All Proyecto EVAT centers self-identify as resource-limited due to a range of limitations in staff and material resources needed for childhood cancer care. Of 23 centers meeting these criteria, hospitals were purposefully selected based on time required for PEWS implementation, including 3 ‘fast' implementing centers (3–4 months between pilot start and implementation completion) and 2 ‘slow' implementors (10–12 months). At the time of this study, these centers had been sustaining PEWS for 8 to 23 months (see Supplementary Table 1 for center characteristics). At each participating center, a study lead identified 10–15 participants who were involved in PEWS implementation (PEWS implementation leaders, hospital directors and administrators, and others indirectly involved in implementation).

To study barriers and enablers of PEWS implementation, an interview guide was developed using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) (50, 51) with adaptations for low-resource settings (52) (Supplementary Figure 1). This interview guide was translated to Spanish and iteratively edited by bilingual members of the study team, then piloted among 3 individuals at non-participating centers but representative of the target participants. Interviews were conducted in Spanish via videoconference by bilingual members of the study team (SRG and PE) from June to August 2020. Interviewers were not previously known to the participants and were not involved in PEWS implementation. Interviews were audio recorded, transcribed, translated, and de-identified prior to analysis.

For the primary study on barriers and enablers to PEWS implementation, a codebook was originally developed using a priori codes from the CFIR and novel codes derived through iterative review of 9 transcripts by two investigators (AA and GF). The transcripts were independently coded using MAXQDA (VERBI Software GmbH) by two investigators (AA and GF), with a third investigator resolving discrepancies (DEG), achieving a kappa of 0.8 to 0.9. “Sustainability” was identified as an inductive theme during this this primary analysis, defined as “the perceived likelihood of continued use of PEWS and activities for the continued achievement of the desired outcomes on patient care, any mention of sustainability or sustainment of use in the long-term, including it becoming part of 'routine' or 'practice' at the hospital.”

Secondary analysis for this study focused on exploring participant perspectives on PEWS sustainability at their centers, including challenges and successes. Three investigators (AA, GSG, VM) conducted thematic content analysis of segments coded as sustainability, with iterative review of transcripts and constant comparative analysis of themes by center. Segments originally coded for sustainability were analyzed to identify participant perception about the importance of PEWS sustainability, factors contributing to sustainability successes and challenges (determinants), and overall evaluation PEWS sustainability at each center at the time of the study.

Identified themes regarding sustainability determinants were then mapped to the CCS, (14, 15) which describes clinical capacity for sustainability within 7 domains: (1) engaged staff and leadership—frontline and administrative staff who are supportive of the intervention; (2) engaged stakeholders—other individuals, such as patients or parents, who are supportive of the intervention; (3) organizational readiness—organizational internal support and the resources needed to effectively manage the intervention; (4) workflow integration—how well the intervention fits into work that is done or will be done; (5) implementation and training—the process of implementing and training to deliver and maintain an intervention; (6) monitoring and evaluation—a process to evaluate the intervention to determine its effectiveness; and (7) outcomes and effectiveness—using monitoring and evaluation to determine outcomes for clinicians or patients.

Examples of how centers overcame challenges to successfully sustain PEWS were then further explored as potential sustainability strategies.

Among 5 pediatric oncology centers, 71 staff including physicians (45%), nurses (45%), and administrators (10%) were interviewed. Of these, 39 (54.9%) were implementation leaders and 21 (29.6%) hospital directors. Characteristics of study participants can be found in Table 1. Sixty-four interviews (90%) mentioned PEWS sustainability; analysis explored participant perceptions of sustainability, determinants that influenced sustainability, and innovative strategies used by participating centers to enhance capacity and PEWS sustainability.

Participant perceptions on PEWS sustainability are described in Table 2. While all participants valued sustaining PEWS, staff from different centers described a range of PEWS sustainability, ranging from use only in pediatric oncology patients and limited infrastructure to maintain PEWS, to extensive use in multiple units and a robust infrastructure for PEWS maintenance.

Staff from all centers recognized the importance of sustaining PEWS after implementation to continue patient benefit: “It's something that should be permanent because the benefits are many. And the benefits are for the patients, that's why we are here” (Nurse, Xalapa). Similarly, positive outcomes from PEWS reinforced staff participation in its continued use: “this is a tool that has allowed us to give a favorable help to the patients, it's something sustainable that, something that makes us participate, and go beyond the normal evaluation of the patient” (Physician, San Salvador). Participants also recognized that sustainability isn't automatic and requires ongoing work from the leadership team: “Still, I think we need to keep working because it's not like we already implemented it and now it works alone.” (ICU Physician, Lima)

Despite the strong desire for PEWS sustainability, participants at different centers described variable degrees of ongoing PEWS use at their hospitals at the time of the study. While some centers felt confident about sustaining PEWS: “Despite everything, EVAT has been working exactly the same, we haven't let that affect our project.” (Nurse, Cuenca), others felt they were “just surviving: “I think [PEWS] is not 100% like we used to be before…but we are surviving.” (Nurse, Lima). Some participants voiced concerns that PEWS was not being sustained, reducing patient benefits: “This year unfortunately we've returned with the sudden deaths, so we didn't learn from the mistakes.” (Nurse, Xalapa). These descriptions of the degree of PEWS sustainability were consistent among participants from a given center, including both implementation leaders and hospital directors, allowing for classification of high-sustainability (Cuenca, San Salvador), medium-sustainability (Lima), and low-sustainability (Xalapa, San Luis Potosi). Table 2 provides more examples of staff perception of the degree of PEWS sustainability at their hospitals.

Six themes regarding determinants influencing PEWS sustainability emerged in our analysis: (1) supportive leadership encouraging ongoing interest in PEWS, (2) beneficial patient outcomes enhancing perceived value of PEWS among staff, (3) integrating PEWS into the workflow for routine patient care, (4) ongoing staff turnover creating training challenges, (5) adequate material resource to promote PEWS use, and (6) COVID-19 as an external stressor. Themes and example quotes can be found on Table 3.

The importance of leadership support was one of the most prominent themes that participants felt influenced the sustainability of PEWS: “If we don't have the support of the authorities, it's more difficult to apply a project like this.” (Physician, Lima) Common types of support included providing financing, equipment needed to use PEWS, and staff acknowledgment for their work. Leadership helped ensure staff were able to maintain expertise needed for PEWS sustainment: “[The leadership] support us in everything, permissions to travel, the courses, … and also to continue with the project.” (Physician, Xalapa). Some hospital directors also approved new institutional policies that helped further codify PEWS as the standard of care: “I was informed that the nursing PEWS guide is ready to be signed, because our managing documents need the signature of our institutional chief.” (Nurse, Lima)

Participants at all centers emphasized that the clear benefit of PEWS encouraged staff to continue using it in patient care: “we didn't expect to have this much motivation… but the project turned out to be so useful that we never imagined to evaluate the patients in the correct way and to identify their deterioration in an early way.” (Nurse, Cuenca). Many participants were initially skeptical about their centers' ability to implement PEWS, and the sense of accomplishment from successful implementation resulting in measurable outcomes further encouraged staff to continue PEWS: “we had good statistics, …we felt victorious.” (Nurse, San Salvador). Similarly, support from authorities was often obtained through demonstrating the positive benefits of PEWS: “I think the sustainability of the project will depend on our results, so the authorities continue with this and support us.” (Physician, Lima)

At several centers, PEWS became the standard of care for both nursing and physician staff: “Now it [PEWS] is already part of our routine and part of us.” (Physician, Cuenca). Initially, both nurses and physicians were wary of change and resisted using PEWS: “At the beginning, the barriers we had were nursing staff because it's difficult to change the working style of people who have been here for 15 or 20 years.” (Physician, Lima). After a few months, however, staff were finding PEWS protocols easy to follow: “we learned a lot from that [pilot] and we got to see our mistakes. … then it started to flow. So, right now it is very easy, it's part of what you do and they even memorized it.” (Physician, San Louis Potosi). Interventions that promoted integration of PEWS into routine patient care included institutional policies and continuous training. The ability to permanently integrate PEWS into the hospital routine was seen as unique compared to other initiatives: “The goal is to be able to reset the staff's thinking and say this is not temporary like all the other things we've had, this is permanent, this is something that should stay in our everyday work.” (Nurse, Xalapa)

Staff turnover in centers trying to sustain PEWS created training challenges as new staff, unfamiliar with PEWS, joined the team. This theme emerged as one of the greatest barriers to sustaining PEWS. Rotation of experienced staff after PEWS implementation required additional training, which was challenging: “[the staff] were not the same we trained in the pilot… they would change people without the right skills so we had to invest time with them and explain how to take the vital signs. That implied more effort… that was the biggest barrier related to the staff.” (Nurse, San Salvador). In academic hospitals, frequent rotation of clinical trainees was an additional barrier: “It gives us uncertainty to be monitoring these people because the rotation in the service is just for 3 months… these people leave and new people come in and we must start all over again. And that has brought severe consequences to the PEWS project.” (Quality Improvement Staff, Xalapa). Changes in hospital leadership were also problematic, requiring extra effort by the PEWS team to convince them of the importance of sustaining this initiative: “We haven't been able to meet with the general director, to it's the most important part because they can help us maintain it.” (Nurse, Xalapa)

Participants at all centers mentioned the need for ongoing availability of economic support to provide material resources, such as vital sign equipment and other supplies, to facilitate ongoing PEWS use: “So, you need to see both the operative and the economic part to make them sustainable in time.” (Nurse, San Salvador). Lack of needed material resources, or organizational capacity, was seen as a barrier to sustainability: “Finance… to get materials…is a barrier to keep the project working.” (Nurse, San Salvador) Centers that were able to obtain necessary material resources, despite initial challenges, reported this facilitated continued PEWS use: “We had a situation with the electromedical equipment, it didn't come, they it came damaged, but once we had the chance…we started and once we did it we never stopped.” (Nurse, Xalapa)

During the COVID-19 pandemic, additional barriers to PEWS sustainability emerged. While some centers were able to sustain PEWS despite COVID-19, others struggled. Most centers experienced staffing shortages that increased the nurse-to-patient ratios: “our workload has doubled… the nursing staff has been reduced” (Nurse, San Louis Potosi) and created additional challenges training new staff: “COVID came … and a lot of nurses got medical leave and they sent us new staff and they were not trained so it turned out very difficult” (Physician, San Louis Potosi). Centers already struggling with material and financial resources before COVID-19 experienced greater resource challenges: “We always need resources; this country is poorer than it used to be… our needs have increased a lot, and we always need material resources and economic resources” (Physician, Cuenca). Physicians from hospitals with difficulties sustaining PEWS frequently mentioned a lack leadership support as PEWS was less prioritized compared to other needs during the pandemic.

Despite these barriers, participants at some centers reported little change in the quality of care provided during the pandemic: “I think that despite of the pandemic, quality is the same” (Physician, Xalapa). For centers sustaining PEWS, staff noted they were able to isolate patients and transfer patients to the ICU or the COVID unit faster: “I think it's a tool that helped us with the pandemic too, if we had it before, the entire hospital would have had this advantage that we have in oncology” (Physician, San Salvador). Organizational readiness and adaptability helped some centers sustain PEWS despite the challenges of the pandemic: “COVID is another thing. It does influence, but [PEWS] is still working, it's being applied, it has been just an adjustment we had to do against this situation” (Physician, Xalapa).

PEWS implementation leaders at all centers used multiple strategies to overcome challenges to sustainability, including multidisciplinary staff engagement, education and training, and maintenance of adequate supplies needed for PEWS (Table 4). The majority of identified sustainability strategies were described by participants at high-sustainability (Cuenca, San Salvador) and medium-sustainability (Lima) centers.

Throughout the planning and early implementation process, PEWS leaders brought together a multidisciplinary team to engage a variety of staff and position PEWS for long-term sustainment: “The greatest strength of PEWS in our institution is that it has been a team, nurses, doctors, and intensivists” (Nurse, Lima). Taking a more multidisciplinary approach positively influenced PEWS sustainability through staff and leadership collaboration. Another method of staff engagement that promoted stainability was creating institutional policies: “we took it as policy of the institution and the nursing system… this has facilitated a lot” (Physician, Lima). The third strategy used was voluntary participation that generated interest for the program in a more diffuse, non-directive manner: “First we asked for volunteers …the one who didn't want to participate were not forced to, but once we had the support of the chiefs, it was part of our daily work and that's how we managed the whole team to participate” (Physician, Lima). If some staff continued to have poor performance using PEWS, leadership would intervene: “the chief would call her and ask her what was happening, if you don't like pediatrics, then you just move” (ICU Physician, Xalapa).

During implementation, PEWS leaders used strategies focused on education and training to create the groundwork to sustain PEWS. Some centers held trainings during work hours as an incentive to participate: “When we proposed the training for the staff, the directors had no problem to program hospital time for the colleagues.” (Nurse, San Salvador). Others used group trainings to share PEWS pilot results and allow team members to learn from each other and increase self-efficacy: “We show the results for how many red [PEWS] were treated; how many went to the intensive care unit. So, showing the results and give the feedbacks with the nurses, the fact that they are part of the results gives them great amount of gratification, and I think now they come voluntarily, with better mood, because they feel they are part of the results and the progress.” (ICU Physician, Cuenca). Ongoing refreshers, or re-training, allowed staff to continuously improve PEWS use, promoting sustainability: “We have given reinforce for some people that make some mistakes… to maintain our error margin the lowest possible.” (Nurse, San Salvador) Many participants mentioned the importance of continuous training to sustain PEWS: “Just one training isn't enough but several trainings that leads to a continuous training.” (Physician, Cuenca)

Obtaining a continuous supply of materials necessary for PEWS was another strategy to promote sustainability. Nursing documentation was permanently changed to facilitate ongoing PEWS use: “We have a sheet for collecting data, the vital signs, which is part of the clinical record. That cannot be removed until someone decides to change that sheet.” (Nurse, Lima) Widely available PEWS materials engaged staff in the program and PEWS educational materials were distributed to promote PEWS use: “it should have high acceptance because we took PEWS to the entire hospital, we posted posters, logos, in the management documents, boards, pins, we would change the PEWS boards constantly” (Nurse, Lima). While most centers obtained supplies necessary for PEWS from their hospital leadership or affiliated foundations, limited resources meant staff would sometimes buy their own supplies to continue using PEWS: “nurses… would go and buy them [oximeters], because that made their work easier” (ICU Physician, Xalapa). All participants, including clinical staff and hospital directors, recognized the need for ongoing availability of material resources to sustain PEWS: “We use to the maximum and avoid waste and splurge of supplies; we have to be practical to use our resources so we can keep the project going.” (Physician, Cuenca)

Sustainability, or the continued use of an evidence-based intervention resulting in maintained beneficial patient outcomes, is considered one of the most significant translation research problems and the least studied phase of the implementation continuum (1, 2). This study presents empiric evidence about staff perspectives on sustainability of an evidence-based intervention, PEWS, in low-resource clinical settings. We demonstrate that both clinical staff and hospital leadership identify the need to sustain effective interventions. The perceived sustainability of PEWS, however, varied across centers, ranging from high- to low-sustainability. Participants identified multiple challenges to sustainability across all hospitals and, particularly in high- and medium-sustainability hospitals, described several creative solutions leveraged as strategies to promote PEWS sustainability in these settings.

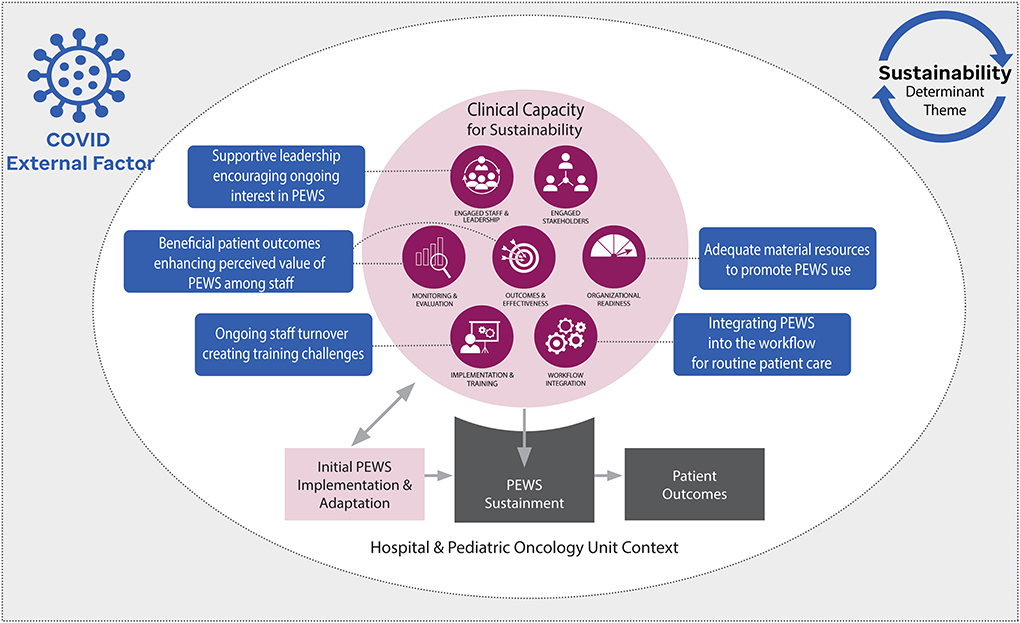

One goal of this study was to evaluate the CCS for conceptualizing sustainability determinants, or factors that served to promote or challenge PEWS sustainability, in a real-world setting. Participant perspectives on the need for ongoing PEWS use (sustainment) to maintain beneficial patient outcomes is consistent with the CCS (5). Similarly, identified sustainability determinants mapped well to the CCS capacity domains (Figure 1) (14, 15), suggesting this model's applicability to these real-world clinical settings. Importantly, identified themes were often interlinked across multiple CCS domains. For example, measuring the impact of PEWS (monitoring and evaluation) was important to demonstrate its benefits to patient outcomes (outcomes and effectiveness), which in turn promoted staff and leadership interest in sustaining PEWS (engaged staff and leadership), including assuring ongoing availability of equipment necessary for PEWS use (organizational readiness). While the CCS suggests discrete capacity domains, this analysis also provides empiric evidence for interaction between determinants indicating that building capacity within one domain is also likely to impact capacity in others. Our team recently integrated serial assessment of clinical capacity for sustainability into the Proyecto EVAT implementation process, with preliminary results suggesting that clinical capacity for sustainability increased over time using PEWS (53). These findings, and the applicability of the CCS, need to be further explored in future work.

Figure 1. Modified clinical capacity sustainability framework (CCS) describing identified themes. The seven domains of clinical capacity for sustainability are represented in dark purple. Our conceptual model posits that clinical capacity for sustainability is initially developed during the implementation process to better support use of the evidence-based intervention, a Pediatric Early Warning System (PEWS). During this time, PEWS may also be adapted to fit existing capacity. Following implementation, clinical capacity for sustainability impacts ongoing use of PEWS (sustainment), ultimately determining the long-term impact on patient outcomes. The blue boxes represent identified sustainability determinant themes as they map to the domains of the CCS. The COVID-19 pandemic was also identified as an external factor that disrupted clinical capacity, ultimately impacting PEWS sustainability at some centers.

Our results also demonstrated that external factors that impact clinical capacity, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, subsequently have a strong influence on sustainability. While the CCS is intended to assess the inner clinical context where interventions are sustained, it may be valuable for practitioners and researchers to be mindful of how external factors like epidemics, political instability, extreme weather incidents, or financial crises might impact internal capacity and whether these impacts are expected to be short-term or long lasting. In alignment with our results, the sustainability literature suggests that maintenance is possible during smaller, more short-term disruptions, but long-term challenges may require adaptation to ensure intervention sustainment (15). More work is needed to better understand upstream, external drivers of clinical capacity to more accurately identify modifiable factors that promote sustainability. Similarly, large-scale prospective studies are needed to quantitatively understand the relationship between capacity factors and sustainability over time.

Another important outcome of our analysis was the identification of several innovative strategies used by local implementation leaders to modify capacity determinants and improve PEWS sustainability in their settings. Thus far, the field of implementation science has focused primarily on conceptualizing and theorizing sustainability in health (11, 12), with a notable lack of empirically-informed sustainability strategies (11). While some determinants of sustainability are similar to those of implementation (e.g., leadership buy-in), others are unique (e.g., staff turnover creating training challenges), and thus require dedicated sustainability strategies (13). This study addresses this knowledge gap by identifying multiple potential strategies to promote intervention sustainability in low-resource hospitals, representing “practice-based evidence” of how to overcome capacity challenges in these settings. More work, however, is needed to better understand best practices for addressing sustainability determinants. Future prospective studies informed by the CCS should more comprehensively identify sustainability determinants and develop empirically-informed sustainability strategies that can be further evaluated using research designs better able to determine their effects on intervention sustainment.

This study has several limitations. The data for this analysis was collected from only 5 Proyecto EVAT centers, which currently represents over 40 hospitals in Latin America with successful PEWS implementation. The identified sustainability determinants and proposed sustainability strategies may not be generalizable to other settings or interventions. Participating centers, however, were purposefully sampled to represent a diversity of regions, hospital organizations, and implementation challenges, and we believe these findings provide important empiric evidence describing intervention sustainability in a variety of low-resource clinical settings. As a secondary analysis, this study mapped identified sustainability determinants to the CCS, however, this framework did not inform the original study design, interview guide, or analysis. The interviews were thus focused primarily on exploring PEWS implementation rather than sustainability and participant discussions of sustainability were spontaneous and not informed by the CCS. One advantage of this analysis is potentially less social desirability bias, as participants were not directly asked about the sustainability of PEWS at their centers. The findings thus describe how sustainability is conceptualized and valued by clinical staff and hospital directors in real-world settings. These findings, however, are likely not inclusive of all possible sustainability determinants or potential strategies, and, as a secondary analysis, important details regarding when, how, and by whom sustainability strategies should be used. A dedicated exploration of these questions should be the focus of future work.

This study describes hospital staff perspectives on the need for sustainable implementation of evidence-based interventions in low-resource hospitals, including identification of sustainability determinants and potential sustainability strategies. Identified determinants mapped well to the CCS, however, external factors, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, may additionally impact clinical capacity for sustainability. This work highlights an urgent need for rigorous development of theoretically-driven, empirically-informed strategies to support sustainable implementation of evidence-based interventions in a range of clinical settings and resource-levels. Future work must focus on integrating strategies informed by the CCS in the planning and early implementation process to support maintained use of effective evidence-based interventions and achieve long-term beneficial patient outcomes.

The raw, de-identified data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by St. Jude Children's Research Hospital (St. Jude) Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

AA and GS-G were responsible for the analyses. All authors except GS-G and VM were responsible for data collection and reporting. AA and VM were responsible for drafting the introduction, methods, and discussion sections of the manuscript. GS-G was responsible for drafting the results section of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved that final manuscript draft.

The current work was supported by a pilot award provided by the St. Jude Children's Research Hospital and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC), as well as a pilot award provided by the National Cancer Institute grant number P50CA244431 awarded to Colditz and Brownson. Agulnik was funded by the Conquer Cancer Foundation Global Oncology Young Investigator Award for this work. These funders were not involved in the design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

We thank the PEWS implementation team at all Proyecto EVAT centers, including those who participated in this study, as well as the Proyecto EVAT Steering Committee for oversight of this work.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frhs.2022.1004805/full#supplementary-material

1. Proctor E, Luke D, Calhoun A, McMillen C, Brownson R, McCrary S, et al. Sustainability of evidence-based healthcare: research agenda, methodological advances, and infrastructure support. Implementation Sci. (2015) 10:88. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0274-5

2. Braithwaite J, Ludlow K, Testa L, Herkes J, Augustsson H, Lamprell G, et al. Built to last? The sustainability of healthcare system improvements, programmes and interventions: a systematic integrative review. BMJ Open. (2020) 10:e036453. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-036453

3. McKay VR, Morshed AB, Brownson RC, Proctor EK, Prusaczyk B. Letting go: conceptualizing intervention de-implementation in public health and social service settings. Am J Community Psychol. (2018) 62:189–202. doi: 10.1002/ajcp.12258

4. Brownson RC, Allen P, Jacob RR, Harris JK, Duggan K, Hipp PR, et al. Understanding mis-implementation in public Health practice. Am J Prev Med. (2015) 48:543–51. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.11.015

5. Shelton RC, Cooper BR, Stirman SW. The sustainability of evidence-based interventions and practices in public health and health care. Annu Rev Public Health. (2018) 39:55–76. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-014731

6. Freedman AM, Kuester SA, Jernigan J. Evaluating public health resources: what happens when funding disappears? Preventing Chronic Disease. (2013) 10:E190. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.130130

7. Wiltsey Stirman S, Kimberly J, Cook N, Calloway A, Castro F, Charns M. The sustainability of new programs and innovations: a review of the empirical literature and recommendations for future research. Implement Sci IS. (2012) 7:17. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-17

8. Hailemariam M, Bustos T, Montgomery B, Barajas R, Evans LB, Drahota A. Evidence-based intervention sustainability strategies: a systematic review. Implement Sci. (2019) 14:57. doi: 10.1186/s13012-019-0910-6

9. Schechter S, Jaladanki S, Rodean J, Jennings B, Genies M, Cabana MD, et al. Sustainability of paediatric asthma care quality in community hospitals after ending a national quality improvement collaborative. BMJ Qual Saf. (2021) 30:876–83. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2020-012292

10. Gruen RL, Elliott JH, Nolan ML, Lawton PD, Parkhill A, McLaren CJ, et al. Sustainability science: an integrated approach for health-programme planning. Lancet. (2008) 372:1579–89. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61659-1

11. Lennox L, Maher L, Reed J. Navigating the sustainability landscape: a systematic review of sustainability approaches in healthcare. Implement Sci. (2018) 13:27. doi: 10.1186/s13012-017-0707-4

12. Birken SA, Haines ER, Hwang S, Chambers DA, Bunger AC, Nilsen P. Advancing understanding and identifying strategies for sustaining evidence-based practices: a review of reviews. Implement Sci. (2020) 15:88. doi: 10.1186/s13012-020-01040-9

13. Pluye P, Potvin L, Denis J-L. Making public health programs last: conceptualizing sustainability. Eval Program Plann. (2004) 27:121–33. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2004.01.001

14. Schell S, Luke D, Schooley M, Elliott M, Herbers S, Mueller N, et al. Public health program capacity for sustainability: a new framework. Implement Sci. (2013) 8:15. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-15

15. Chambers DA, Glasgow RE, Stange KC. The dynamic sustainability framework: addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implement Sci. (2013) 8:117. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-117

16. Malone S, Prewitt K, Hackett R, Lin JC, McKay V, Walsh-Bailey C, et al. The clinical sustainability assessment tool: measuring organizational capacity to promote sustainability in healthcare. Implement Sci Commun. (2021) 2:77. doi: 10.1186/s43058-021-00181-2

17. Cowie J, Nicoll A, Dimova ED, Campbell P, Duncan EA. The barriers and facilitators influencing the sustainability of hospital-based interventions: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. (2020) 20:588. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05434-9

18. Ward ZJ, Yeh JM, Bhakta N, Frazier AL, Atun R. Estimating the total incidence of global childhood cancer: a simulation-based analysis. Lancet Oncol. (2019) 20:483–93. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30909-4

19. Ward ZJ, Yeh JM, Bhakta N, Frazier AL, Girardi F, Atun R. Global childhood cancer survival estimates and priority-setting: a simulation-based analysis. Lancet Oncol. (2019) 20:972–83. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30273-6

20. Ceppi F, Antillon F, Pacheco C, Sullivan CE, Lam CG, Howard SC, et al. Supportive medical care for children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia in low- and middle-income countries. Expert Rev Hematol. (2015) 8:613–26. doi: 10.1586/17474086.2015.1049594

21. Duke T, Cheema B. Paediatric emergency and acute care in resource poor settings. J Paediatr Child Health. (2016) 52:221–6. doi: 10.1111/jpc.13105

22. Dray E, Mack R, Soberanis D, Rodriguez-Galindo C, Agulnik A. Beyond supportive care: a collaboration to improve the intensive care management of critically ill pediatric oncology patients in resource-limited settings. Pediatr Blood Cancer. (2017) 64(Suppl 3):229.

23. C Schell CO, Khalid K, Wharton-Smith A, Oliwa J, Sawe HR, Roy N, et al. Essential emergency and critical care: a consensus among global clinical experts. BMJ Global Health. (2021) 6:3191. doi: 10.1101/2021.03.18.21253191

24. Friedrich P, Ortiz R, Fuentes S, Gamboa Y, Ah Chu-Sanchez MS, Arambu IC, et al. Central American Association of Pediatric, and Oncologists, Barriers to effective treatment of pediatric solid tumors in middle-income countries: can we make sense of the spectrum of nonbiologic factors that influence outcomes? Cancer. (2014) 120:112–25. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28339

25. Rodriguez-Galindo C, Friedrich P, Morrissey L, Frazier L. Global challenges in pediatric oncology. Curr Opin Pediatr. (2013) 25:3–15. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e32835c1cbe

26. Agulnik A, Cárdenas A, Carrillo AK, Bulsara P, Garza M, Alfonso Carreras Y, et al. Clinical and organizational risk factors for mortality during deterioration events among pediatric oncology patients in Latin America: a multicenter prospective cohort. Cancer. (2021) 127:1668–78. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33411

27. Brown SR, Martinez Garcia D, Agulnik A. Scoping review of pediatric early warning systems (PEWS) in resource-limited and humanitarian settings. Front Ped. (2018) 6:410. doi: 10.3389/fped.2018.00410

28. Agulnik A, Forbes PW, Stenquist N, Rodriguez-Galindo C, Kleinman M. Validation of a pediatric early warning score in hospitalized pediatric oncology and hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients. Pediatr Crit Care Med. (2016) 17:e146–53. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000662

29. Dean NP, Fenix JB, Spaeder M, Levin A. Evaluation of a pediatric early warning score across different subspecialty patients. Pediatr Crit Care Med. (2017) 18:655–60. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000001176

30. Agulnik A, Gossett J, Carrillo AK, Kang G, Morrison RR. Abnormal vital signs predict critical deterioration in hospitalized pediatric hematology-oncology and post-hematopoietic cell transplant patients. Front Oncol. (2020) 10:354. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.00354

31. Agulnik A, Johnson S, Wilkes R, Faughnan L, Carrillo A, Morrison R. Impact of implementing a pediatric early warning system (PEWS) in a pediatric oncology hospital. Pediatric Quality & Safety. (2018) 3:e065. doi: 10.1097/pq9.0000000000000065

32. Agulnik A, Soberanis Vasquez DJ, García Ortiz JE, Mora Robles LN, Mack R, Antillón F, et al. Successful implementation of a pediatric early warning score in a resource-limited pediatric oncology hospital in guatemala. J Global Oncol. (2016) 3:3871. doi: 10.1200/JGO.2016.003871

33. Agulnik A, Mora Robles LN, Forbes PW, Soberanis Vasquez DJ, Mack R, Antillon-Klussmann F, et al. Improved outcomes after successful implementation of a pediatric early warning system (PEWS) in a resource-limited pediatric oncology hospital. Cancer. (2017) 123:2965–74. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30664

34. Agulnik A, Mendez Aceituno A, Mora Robles LN, Forbes PW, Soberanis Vasquez DJ, Mack R, et al. Validation of a pediatric early warning system for hospitalized pediatric oncology patients in a resource-limited setting. Cancer. (2017) 123:4903–13. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30951

35. Agulnik A, Nadkarni A, Mora Robles LN, Soberanis Vasquez DJ, Mack R, Antillon-Klussmann F, et al. Pediatric early warning systems aid in triage to intermediate versus intensive care for pediatric oncology patients in resource-limited hospitals. Pediatr Blood Cancer. (2018) 65:e27076. doi: 10.1002/pbc.27076

36. Graetz D, Kaye EC, Garza M, Ferrara G, Rodriguez M, Soberanis Vásquez DJ, et al. Qualitative study of pediatric early warning systems' impact on interdisciplinary communication in two pediatric oncology hospitals with varying resources. JCO Global Oncol. (2020) 6:1079–86. doi: 10.1200/GO.20.00163

37. Graetz DE, Giannars E, Kaye EC, Garza M, Ferrara G, Rodriguez M, et al. Clinician emotions surrounding pediatric oncology patient deterioration. Front Oncol. (2021) 11:626457. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.626457

38. Garza M, Graetz DE, Kaye EC, Ferrara G, Rodriguez M, Soberanis Vasquez DJ, et al. Impact of PEWS on perceived quality of care during deterioration in children with cancer hospitalized in different resource-settings. Front Oncol. (2021) 11:51. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.660051

39. Gillipelli SR, Kaye EC, Garza M, Ferrara G, Rodriguez M, Soberanis Vasquez DJ, et al. Pediatric Early Warning Systems (PEWS) improve provider-family communication from the provider perspective in pediatric cancer patients experiencing clinical deterioration. Cancer Med. (2022) 54:5210. doi: 10.1002/cam4.5210

40. Agulnik A, Antillon-Klussmann F, Soberanis Vasquez DJ, Arango R, Moran E, Lopez V, et al. Cost-benefit analysis of implementing a pediatric early warning system at a pediatric oncology hospital in a low-middle income country. Cancer. (2019) 125:4052–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32436

41. Agulnik A, Gonzalez Ruiz A, Muniz-Talavera H, Carrillo AK, Cárdenas A, Puerto-Torres MF, et al. Model for regional collaboration: Successful strategy to implement a pediatric early warning system in 36 pediatric oncology centers in Latin America. Cancer. (2022). doi: 10.1002/cncr.34427. [Epub ahead of print].

42. Martinez A, Baltazar M, Loera A, Rivera R, Aguilera M, Garza M, et al. Addressing barriers to successful implementation of a pediatric early warning system (PEWS) at a pediatric oncology unit in a general hospital in Mexico. Pediatr Blood Cancer. (2019) 66(Suppl 4):S533–4.

43. Rivera J, Hernández C, Mata V, Espinoza S, Nuñez M, Perez Y, et al. Improvement of clinical indicators in hospitalized pediatric oncology patients following implementation of a pediatric early warning score system. Pediatr Blood Cancer. (2019) 66(Suppl 4):s536–7.

44. Vergara P, Saez S, Palma J, Soberanis D, Agulnik A. Implementation of a pediatric early warning system in pediatric patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in Latin America. Pediatr Blood Cancer. (2017) 64(Suppl 3):S24.

45. Diaz-Coronado R, Pascual Morales C, Rios Lopez L, Morales Rivas R, Muniz-Talavera H, et al. Reduce mortality in children with cancer after implementation of a pediatric early warning system (PEWS): a multicenter study in Peru. Pediatric Blood Cancer. (2021) 68:S52–3.

46. Fing E, Tinoco R, Paniagua F, Marquez G, Talavera HM, Agulnik A. Decrease in mortality is observed after implementing a pediatric early warning system in a pediatric oncology unit of the general hospital of Celaya, Mexico. Pediatric Blood Cancer. (2021) 68:S327–8.

47. Mirochnick E, Graetz DE, Ferrara G, Puerto Torres M, Gillipelli S, Elish P, et al. Multilevel impacts of a pediatric early warning system in resource-limited pediatric oncology hospitals. Front Oncol. (2022) 12:8224. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.1018224

48. Agulnik A, Ferrara G, Puerto-Torres M, Gillipelli SR, Elish P, Muniz-Talavera H, et al. Assessment of barriers and enablers to implementation of a pediatric early warning system in resource-limited settings. JAMA Netw Open. (2022) 5:e221547. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.1547

49. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. (2007) 19:349–57. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

50. Damschroder LJ. Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR). Available online at: https://cfirguide.org/ (accessed October 19, 2022).

51. Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci IS. (2009) 4:50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50

52. Means AR, Kemp CG, Gwayi-Chore MC, Gimbel S, Soi C, Sherr K, et al. Evaluating and optimizing the consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR) for use in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Implement Sci IS. (2020) 15:17. doi: 10.1186/s13012-020-0977-0

53. Agulnik A, Malone S, Puerto-Torres M, Gonzalez-Ruiz A, Vedaraju Y, Wang H, et al. Reliability and validity of a Spanish-language measure assessing clinical capacity to sustain paediatric early warning systems (PEWS) in resource-limited hospitals. BMJ Open. (2021) 11:e053116. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-053116

Keywords: sustainability, pediatric early warning systems (PEWS), resource-limited settings (RLS), pediatric oncology, global health, implementation science (MeSH)

Citation: Agulnik A, Schmidt-Grimminger G, Ferrara G, Puerto-Torres M, Gillipelli SR, Elish P, Muniz-Talavera H, Gonzalez-Ruiz A, Armenta M, Barra C, Diaz-Coronado R, Hernandez C, Juarez S, Loeza JdJ, Mendez A, Montalvo E, Penafiel E, Pineda E, Graetz DE and McKay V (2022) Challenges to sustainability of pediatric early warning systems (PEWS) in low-resource hospitals in Latin America. Front. Health Serv. 2:1004805. doi: 10.3389/frhs.2022.1004805

Received: 27 July 2022; Accepted: 10 October 2022;

Published: 31 October 2022.

Edited by:

Nicole Nathan, The University of Newcastle, AustraliaReviewed by:

Emma Doherty, The University of Newcastle, AustraliaCopyright © 2022 Agulnik, Schmidt-Grimminger, Ferrara, Puerto-Torres, Gillipelli, Elish, Muniz-Talavera, Gonzalez-Ruiz, Armenta, Barra, Diaz-Coronado, Hernandez, Juarez, Loeza, Mendez, Montalvo, Penafiel, Pineda, Graetz and McKay. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Asya Agulnik, YXN5YS5hZ3VsbmlrQHN0anVkZS5vcmc=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.