94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Environ. Econ., 17 March 2023

Sec. Economics of Climate Change

Volume 2 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/frevc.2023.1110214

This article is part of the Research TopicOne Ocean, One Climate, One Future: Environmental EconomicsView all 6 articles

The ocean plays a fundamental role in the human wellbeing and development. Therefore, it is vital to preserve and restore the marine ecosystem services that are being damage through climate change and anthropic activities, even more in countries such as the Maldives that has been classified under a high degree of exposure and vulnerability. The purpose of this article is to provide an overview of the problems facing coral reefs in the Maldives through relevant scientific insights; outline the importance of reef conservation in this area, given their ecosystem services; and briefly discuss policies and mitigation plans for reef conservation in the Maldives against anthropic activities and climate change, including potential funding sources and how best to engage with local communities and other stakeholders in this effort. This will help to achieve several SDGs.

In recent years, climate change and anthropic activities have been shown to affect many biological marine ecosystems and their services detrimentally (Claudet et al., 2020). The mitigation of climate and anthropic impacts has never been more imperative, especially for countries like the Maldives whose vulnerability to climate change impacts paired with a long-standing dependency to marine ecosystem services threaten their economies, wellbeing and livelihoods. Mitigation has been defined as an anthropic intervention to decrease the sources of greenhouse gases (GHGs) or improve their sinks (IPCC, 2014). Given the high biomass and biodiversity of corals that can be observed in the EEZ of the Maldives, this country is defined as a coral reef province (Naseer and Hatcher, 2004), which therefore requires reliable plans and policies to assist in safeguarding its marine resources with an understanding of the needs of future generations. Coral reefs in the Maldives have a particularly important role in the livelihood and welfare of its people as a key resource in the economy through tourism and activities. And yet, the Maldivian corals remain poorly known as underdeveloped systems of data collection and analyses fail to fully highlight the underlying value of existing resources and the challenges associated with safeguarding them (Mukhjerjee and Chakraborty, 2013; Schoenaker et al., 2015; Radovanović and Lior, 2017). This article therefore aims to showcase points of view from different experts and fields on the importance of preserving and restoring the coral reefs in The Maldives.

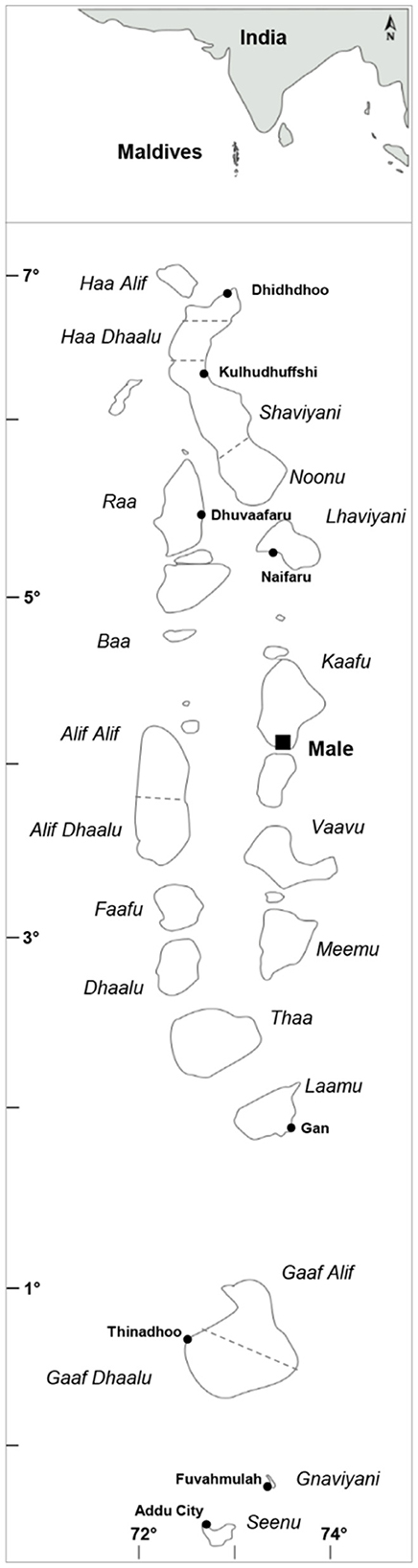

The Republic of Maldives is an archipelagic state composed of 1,192 coralline islands located in the Indian Ocean, south-west of India and Sri Lanka. The small island nation, with its capital in Malé, extends for 860 km in longitude, from the Ihavandippolu Atoll in the northern hemisphere (7°06′54″N), to the southernmost atolls, Fuvahmulah and Addu, lying just under the equator (0°42′24″S). The islands, grouped into 20 atoll-systems for administrative purposes (Zubair et al., 2011), sit on top of two parallel submerged ridges with an average altitude of 1.5 m and no point higher than 2.3 m above mean sea level (Di Fiore et al., 2020). The islands are geographically fragmented over a total area of 115.300 km2 (Maldives National Bureau of Statistics, 2020), but the land area only accounts for roughly 298 km2 (Kothari and Arnall, 2017). The majority of the islands have a land area between 0.5 and 1 km2 (Domroes, 2001), with no island larger than 10 km2 (Stojanov et al., 2017).

Around 62% of the total resident population of the Maldives, estimated at around 530,953 individuals (World Bank, 2020a), is scattered throughout the country from central to peripheral islands. Numbers vary across atolls with a small population (between 1,000 and 4,500 inhabitants) to much fewer inhabited islands and atolls with over 15,000 inhabitants (Malatesta and Di Friedberg, 2017). In contrast, the remaining 38% of the population lives in the capital island of Malé, in a surface area of <2 km2 (Maldives National Bureau of Statistics, 2020). The urban center of the island, one of the most densely populated in the world, has a population density over 39,000 inhabitants/km2 and is expected to continue growing with increased urbanization (Bisaro et al., 2020). Indeed, the Greater Malé Region attracts communities from remote islands, owing to its wider access to both infrastructure and economic opportunities (MEE, 2016). To date, 187 islands are inhabited, 145 are resorts islands, structured following the so-called “One island, one resort” model, and the remaining islands are dedicated to airports, plantations, industrial and agricultural activities, garbage storage and prisons, or remain uninhabited (dell'Agnese, 2019).

The Maldivian atoll ecosystems include a great variety of habitats, such as extensive shallow and deep lagoons, deep slopes, sandy beaches, and limited mangrove and seagrass areas. However, the Maldives are known across the globe to be an historical archetype of a coral reef province (Naseer and Hatcher, 2004). Coral reefs in the Indian Ocean, where the Maldives are situated, make up about 11% of the global reef area (Burke et al., 2011). The Maldivian reefs cover an area of ~4,500 km2, comprised of 2,041 distinct coral reefs (Naseer and Hatcher, 2004), corresponding to nearly 5% of the world's reefs and representing the 7th largest coral reef system in the world in terms of area covered (Spalding et al., 2001).

Maldivian reefs are known for the diversity of life forms that they host, despite vast knowledge gaps on the biodiversity they sustain. The major actors in coral reef ecosystems are usually stony corals, which are colonial animals able to build a skeletal structure made of calcium carbonate. The Maldives hosts some 300 species of reef building corals (Pichon and Benzoni, 2007) that support the incredible biodiversity of organisms living in Maldivian waters. The Maldives accounts for a total of 1,100 species of demersal and epipelagic fish, including sharks, 5 species of marine turtles and 20 species of whales and dolphins (Frazier et al., 1984; Anderson, 2005; Ali and Shimal, 2016). The majority of species are invertebrates, including 400 species of mollusks, 120 species of copepods, 15 species of amphipods, over 145 species of crabs and 48 species of shrimps (Convention on Biological Diversity). This census of species is subject to change as these species are often cryptic, morphologically very simple and difficult to study from a taxonomical point of view (Montano et al., 2015a,b; Maggioni et al., 2016, 2017a,b, 2021; Seveso et al., 2020).

The last decades have witnessed a continuous decline of coral reefs around the world. Only twenty-five states have jurisdiction in most of the world's warm-water coral reef ecosystems, however threats to these ecosystems trespass geographic barriers in several of these states and continue to increase. Exploitative uses of the ocean such as intense fisheries, coral and sand mining, and non-exploitative but damaging reef uses such as anchoring on reefs (Shareef, 2010) have resulted in a loss of topographic complexity and species diversity, leaving behind an unconsolidated substrate, which is only subject to further erosion. Coastal zones have undergone changes through the addition of hard structures such as seawalls, breakwaters and jetties, which have become the standard in many inhabited islands, as a direct consequence of the advance of human settlements toward beaches. This expansion has led to increased land reclamation, the creation of artificial islands and of new touristic resorts, which in turn introduce new risks linked to plastic pollution and emerging contaminants (Fallati et al., 2017; Saliu et al., 2018, 2022; Duvat, 2020; Montano et al., 2020; Pancrazi et al., 2020; Rizzi et al., 2020; Galli et al., 2021). Research indicates that coral reefs can effectively protect coastlines from tropical cyclones and other large wave impacts.1 “Restored reefs could reduce wave energy immediately, becoming more valuable through the years as they grow, keeping pace with rising sea levels. While reducing risk, coral reefs also support biodiversity, improve water quality, and support fisheries and tourism.”2 This is of relevance to the Maldives, as about over 80 per cent of the land area is <1 m above mean sea level, so it is particularly at risk from future sea level rise.

In the Maldives specifically, multiple stressors are affecting coral reef communities, resulting in a rapid decrease in diversity, area coverage and ecological interactions in reef ecosystems. The Maldivian reefs have been among the most affected areas in the world by climate change, thermal stressors, and related coral bleaching episodes with 60–100% coral mortality reported after the event of 1998 (Zahir et al., 2010), followed by another bleaching event in 2010 (Tkachenko, 2012, 2015). The more recent event in 2015–2016 is to date considered the longest and most widespread global coral bleaching event (Hughes et al., 2018a,b,c; Sully et al., 2019). The Maldivian reefs were severely affected: sea surface temperatures peaked from late April to mid-May 2016 with recorded temperatures over 32°C. The overall percentage of bleached corals was recorded at around 75%, including corals sitting as far as 15 m depth (Ibrahim et al., 2017; Perry and Morgan, 2017). Other stressors also include an increased recurrence of different epizootic disease caused by fungi, protozoa and bacteria (Montano et al., 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015c; Seveso et al., 2012, 2015), as well as by the anomalous outbreaks of corallivorous organisms that feed on corals, such as the crown-of-thorns seastar Acanthaster species and the cushion star Culcita species (Saponari et al., 2014, 2018; Montalbetti et al., 2019, 2022).

The marine environment has always been fundamental to societal welfare and development in the Maldives (Collins, 2013). Coral reefs began to be used for building purposes in the 1970s to offer natural coastal protection and fisheries opportunities (Lam et al., 2019). This period saw the advent of tourism, which quickly became the economic sector with the highest growth rate, due in part to significant developments in island infrastructure that made tourism the country's main industry (Collins, 2013; WTO, 2019). Since 2015, the service sector has accounted for about 75% of the country's GDP (Maldives National Bureau of Statistics, 2020). Indeed, the Maldives' economy has grown fast since the 1970s, with a GDP which were among the lowest in the world and yet reached the level of upper-middle-income countries in the 2010s (Encyclopædia Britannica, 2020). However, tourism has been seriously affected by COVID-19, with the hotel occupancy rate falling from 73% in January 2020 (pre pandemic) to 69% in February, 36% in March, 4% in April, 5.2% in May and 2.5% in June (Maldives Ministry of Tourism, 2021). Consequently, in the first quarter of 2020, tourism revenues fell by 23.4%, and GDP contracted by 5.9% (World Bank, 2020b). While real GDP growth rebounded to 37% in 2021, it will likely remain below 2019 levels until 2023. It is projected that even if long and medium-term tourism stays strong, visitor arrivals will not return to pre-pandemic levels until 2023. Extra financial aid will be difficult to get due to the pandemic's global impact (World Bank, 2020b).

While coral reefs are a major factor in the Maldives' appeal as a tourist destination, coral mining has resulted in massive degradation of shallow reef-flat areas, with important negative impacts on coastal protection. This has called for the launch of monitoring programs (Dryden et al., 2020), carried out by the Ministry of Fisheries and Agriculture which is mandated with an aspect of environmental management expressly associated with marine resources and fisheries. The majority of the work related to marine resources, fisheries, monitoring, and research on reef health is carried out by the Marine Research Center, which in turn is regulated by the Ministry of Fisheries (Jaleel, 2013). To promote sustainable tourism the Maldives is (1) diversifying the products from tourism offered by the Maldives; (2) increasing the benefits of tourism accruing to local communities; (3) increasing the number of Maldivians employed in the tourism sector, (4) strengthening regulatory frameworks governing the tourism industry and the monitoring capacity of relevant institutions; and (5) achieving sustainable growth in the guesthouse tourism sector (SAP, 2019).

In 1978, the Maldives became a member of the World Bank, which has brought support for the implementation of 32 sustainable projects, requiring US$295 million. The partnership aimed to help the country achieve more sustainable and inclusive growth, and improve the use of natural, human, and financial capital (World Bank, 2020a). Moreover, since 1983, the IFC has invested over US$157 million in the Maldives (World Bank, 2020a). The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is providing financing solutions, publishing research on economic implications of climate change and providing policy advice to help member countries capture the opportunities of low-carbon, resilient growth. The Fund is also offering data analytics including through a Climate Change Indicators Dashboard, capacity development to help member countries address climate change challenges. Maldivian government continues to look for different ways to increase its private and public resources available for climate action. To this end, partnerships with the private sector, civil society, philanthropists, and local governments must secure climate finance—through annual budget increases and new budgetary contributions, local contributions, and Public Sector Investment Program allocations. Additionally, the Maldivian government through the establishment of a National Climate Change Trust Fund continues its efforts to attract climate finance through investments in projects, providing loans and innovating their financing mechanisms to increase low-emission and resilience development programs. The National Strategic Framework will be updated every 5 years to attract international climate finance, by prioritizing areas for donor support and establishing a system to track private and public climate finance flows. In order to finance investments in climate actions, the Maldivian government will also continue allocations from the Maldives Green Fund, among others, creating incentives for different stakeholders to invest in green development (MEE, 2020).

The cost of coral reefs restoration is high; it can range anywhere from US$11,717/ha to US$2,879,773/ha (Bayraktarov et al., 2016; Hein et al., 2018). Coral reefs protection can be financed in several ways: governments that provide financial support through direct government expenditures, market regulation, pollution credits and taxes, subsidies and fiscal policies (Iyer et al., 2018), can be paired with fees and taxation systems directed at users to generate resources for protected areas. Fees and taxation systems are methods to charge users of natural resources for the management costs of those resources (Iyer et al., 2018). The Maldives use a green tax, levied on tourists staying at resorts, hotels, or on vessels. The green tax is used in diverse projects like the Maldives Clean Environmental Project as well as for island sanitation, the establishment of sewage systems and the construction of regional laboratories for water research. This total green tax revenue between January and November 2020 amounted to around US$21 million (Figure 1). Alternatively, debt-for-nature swaps can create very targeted funding for conservation (Iyer et al., 2018), defined by Quintela et al. (2003) as “a multiple-party transaction in which the sovereign debt of a country is forgiven or partially forgiven by its debtors, in exchange for certain commitments to biodiversity conservation by the indebted country.” The debt is usually owed in hard currency and the creditors tend to be mature economies. For biodiversity offsets and insurance schemes, technical capacity and expertise are needed, thus requiring more time and resources.

Figure 1. Map of the Republic of Maldives showing its geographical position (upper panel) and a focus on its atolls (bottom panel). The 26 geographic atolls of the Maldives are here grouped and represented into 20 atoll-systems for administrative purposes. The names of the atolls are written in italics, while the names of the main cities are written in bold.

The Maldivian government has developed various programmes and agreements to protect and conserve marine ecosystems. In the area of fisheries, the government has implemented a shortterm plan for the period 2019–2024, the Maldives Sustainable Fisheries Resources Development Project, which aims to improve fisheries management at the national and regional levels. In addition, the Maldives Fisheries Blue Economy Development Project, the Maldives National Action Plan to Prevent, Deter and Eliminate Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing (NPOA-IUU) and the National Fisheries and Agriculture Policy 2019–2029 are currently underway, which aims to enhance environmental resilience, value chain coordination, food security and nutrition, community empowerment, research, education and technology, institutional support and national and inter-sectoral partnership. All these pillars are based on the UN SDG's and the UN Decade for Marine Science (2021–2030) (Melina and Santoro, 2021; Ministry of Fisheries, 2023).

In the field of reefs, the Maldives Marine Research Institute (MMRI) is responsible for officially monitoring the condition of the country's coral reefs. The MMRI has two main programmes, the National Coral Reef Monitoring Programme (1998) and the National Coral Reef Restoration and Rehabilitation Programme, which was launched in 2019. The MMRI also cooperates with the Environmental Protection Agency and international agencies in coral reef monitoring and research (International Coral Reef Initiative (ICRI), 2021).

The Maldives also receives support from the Global Fund Coral Reef and is part of the Commonwealth Blue Charter, which seeks improvements in coral reef protection and restoration, mangrove ecosystems and livelihoods, marine protected areas, ocean acidification, ocean and climate change, ocean observing, sustainable aquaculture, sustainable blue economy, and sustainable coastal fisheries (The Commonwealth Blue Chart, 2018).

The Global Fund for Coral Reef (GFCR) is a 10-year financial instrument created specifically for the restoration and protection of coral reef ecosystems. It is supported by the Conservation Finance Alliance (CFA), which is an investment and development plan. The GFCR acts as an investment facilitator to provide funds that improve the resilience of coral reefs and the livelihoods of local communities. Grants provided by the GFCR aim to launch projects that can have positive environmental and socio-economic impacts. In parallel, the investments provided by the GFCR are managed by BNP Paribas and supported by the blue economy expertise of Althelia Funds (Mirova/Natixis). Currently, about $125 million is provided by donors, almost $375 million to partner funds and between $2 and $3 billion from global private and public financial instruments (Global Funds for Coral Reefs (GFCR), 2021).

In addition, the Maldives participates in other international agreements such as the 15th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity, the Cartagena Protocol, the Kyoto Protocol, the Nagoya Protocol on Access and Benefit-sharing, the Paris Agreement, the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty, UNCLOS, among others (Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), 2022; Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), 2022).

One possible mechanism to support coral reef conservation that is popular among decision makers is based on payments for ecosystem services (PES). PES is defined as the payment that an ecosystem services owner (a landowner or community, for example) will receive to protect a specific ecosystem service, thereby supporting human wellbeing from both a socio-economic and ecological perspective (Costanza et al., 2017). This means that the coastal protection and maintenance of natural habitats and biodiversity (including fish stock) that are naturally provided by coral reefs potentially hold financial benefits for local communities. However, this approach has to be implemented with great care because, as Braat and de Groot (2012) explains, some advocates argue that “it is analytically more appropriate to conceptualize payments for ecosystem services as incentives for collective action rather than as quasi-perfect market transactions to solve market failures.” Alternative sources of funding for such ecosystem services include conservation trust funds that can provide targeted financial support for specific ecosystems (UN Environment, 2019). The Global Fund Coral Reef (GFCR) is a 10-year financial instrument specifically created to restore and protect coral reefs ecosystems. It is supported by the Conservation Finance Alliance (CFA), which is an investment and development plan. The GFCR acts as an investment link to bring funds for improved resilience of coral reefs and livelihoods of local communities, by providing grants for projects that can have both positive environmental and socio-economical impacts. The investments provided by the GFCR are managed by BNP Paribas and supported by blue economy expertise from Althelia Funds (Mirova/Natixis). There are currently around $125 million provided by donors, near $375 million in partner assets and between $2 and $3 billion unlocked from global private and public financial instruments (Global Funds for Coral Reefs (GFCR), 2021).

The relationship between education—social perception—valuation of ES must be carefully considered to develop a better approach for realistic valuation of nature. This approach is still a long way from being achieved coherently and productively but can be considered a valuable tool to mitigate climate change impacts and contribute to conservation. The participation of institutions will be vital to ensure biodiversity conservation and the sustainable use of ES in the long-term (TEEB Foundations, 2010). Furthermore, decision-makers must understand the complex interrelations between social, cultural, and economic factors and values. Policymakers and stakeholders can promote integrated coastal zone management with shared benefits and increased knowledge and research. New financial tools and mechanisms can help states gain access to additional resources to fill the capacity gap. The need to diversify and increase funding for coral reefs could fuel the implementation of a mechanism specifically for coral reef ecosystems conservation for the benefit of society alongside biodiversity.

The Maldivian Constitution states specifically in its Article 22 that “the State has a fundamental duty to protect and preserve the natural environment, biodiversity, resources and beauty of the country for the benefit of present and future generations.” In addition, Article 67(h) states that “the Executive has the duty to prevent and protect the natural environment, biodiversity, resources and beauty of the country and to abstain from all forms of pollution and ecological degradation,” (Constitution of the Republic of Maldives, 2008; Dhunya et al., 2017). The Maldives has considerable scope for adaptive capacity, being part of The Commonwealth Blue Charter, which defends coral reef restoration and protection as well as approaches to sustainable blue economies and coastal fisheries (The Commonwealth Blue Chart, 2018). Since the launch of a sea wall project around the capital Malé in September 1988, the government has implemented several projects aimed at adapting to environmental threats. Frontier analysis based on the positive relationship between the adaptation index and income levels suggests that distance to the frontier is large for the Maldives, among several countries (International Monetary Fund (IMF), 2021). The green and adaptive infrastructure gap in the country is threatening both climate mitigation (renewables and nature preservation) and adaptation (coastal protection, water and waste management and resilient infrastructure).

Marine protected areas are among the most useful tools to reduce human pressures on coral reefs and restore their natural functions (Dryden et al., 2020). The Maldives have proposed to transform a vast part of the country as a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve to protect diverse key ecosystems and the related ecosystem services which can support the sustainable development of the Maldivian economy (Dryden et al., 2020)3. Yet, the marine area with currently implemented protection in 2022 covers < 1% (614 km 2) of the country's 920,739 km2 exclusive economic zone (EEZ) (Table 1).

The Government of the Maldives and the Blue Prosperity Coalition is in 5-year a partnership to protect the ocean and its resources in order to build a sustainable community and economy, and while preserving the environment (Healthy oceans|Noo Raajje|Maldives). “The program will also promote the advancement of Maldivian ocean science and stewardship through research, education, capacity building, and outreach, including collaborating with and providing support to local scientists and civil society.”

“The Noo Raajje initiative aims to:

• safeguard ocean resources and restore coral ecosystem health,

• sustainably grow ocean industries,

• strengthen the Maldives' position in managing shared Indian Ocean tuna stocks, and

• protect at least twenty percent of Maldivian waters.”

• “The 2020 Maldives Coral Reef Assessment Report provides the results from the 2020 expedition, which surveyed the coral reefs and fish populations across the northern and central atolls of the Maldives.

• The results of the assessment suggest that overall, Maldivian reefs have the capacity to recover following warming events, but local stressors may impact reef health at the local scale.

• The assessment is based on two expeditions of the northern and central atolls, carried out in January and February 2020.”

“The 2021 Legal and Policy Framework Assessment Report describes how existing legal authorities contribute to ocean management in the Republic of the Maldives (the Maldives), outlining the legal foundation for developing an enforceable, comprehensive, and sustainably financed marine spatial plan and blue economy strategy.”

The Partnership Is also helping to build strategies for building sustainable fisheries and seafood markets.

Despite the strategies already proposed by the Maldivian government, new programmes should be created that focus on local participation and citizen science. To achieve this goal, the government should integrate environmental education into its main programmes and strengthen citizen science. In addition, a coordinated monitoring system for coral reefs should be established, including not only private stakeholders and NGO's, also, add state institutions and local professionals and experts. In this manner, all information collected through monitoring could be made available in a unified information system. As a result, it would be easier for policy makers and stakeholders to develop new mechanisms and tools to improve coral reef management and conservation.

The Maldives is active in international climate fora and have shown early commitment to adaptation and mitigation plans for climate change. The number of scientific and technical assessments undertaken in the country since 1987 has reiterated the need for long-term adaptation to climate change (National Adaptation Programme of Action (NAPA), 2006)4. The country was a prominent player in the negotiations that led to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and was the first to sign the Kyoto Protocol to the UNFCCC. The Maldives submitted the First National Communication (FNC) to the UNFCCC in 2001 following the implementation of the Maldives Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Inventory and Vulnerability Assessment: A Climate Change Enabling Activity. The Maldives' strategy to reduce CO2, CH4 and N2O emissions was created under the influence of the 2006 IPCC Guidelines.

In 2006, the Maldives adopted the National Adaptation Program of Action (NAPA), which lays out a framework for action built around the complex relationship between sustainability and adaptation to climate change.5 The first NAPA was then used in that same year to communicate the most urgent and immediate adaptation needs of the Maldives, as stipulated under UNFCCC Decision 28/CP and supporting the sustainable development goals (SDGs). Various national mitigation and adaptation strategic plans and policies have been enacted since then.6

Since the adoption of NAPA, the Maldives have implemented various non-structural interventions and institutional reforms in support of climate adaptation7, which involved developing guidelines, operating frameworks and action plans to help guide current and/or future planning. These plans are quite granular in nature, invariably outlining sectoral action plans for each vulnerable sector. And yet, implementation is lacking as the Maldives have not enacted any regulations to directly address climate change nor do they have concrete financing plans. This implementation gap is particularly problematic for coral reef protection and restoration, despite a bleaching response program created and developed to guide different stakeholders in the assessment, detection and response to coral bleaching events in the Maldives. The plan would be implemented through an early warning system, an incident response plan and communications strategies, with the help of task forces, coast guards, the Environmental Protection Agency and the Marine Research Center (Marshall et al., 2017).

Although investing in adaptation infrastructure can yield high returns, it is fiscally costly. Financing large adaptation investment will challenge fiscal space in many countries, which have deteriorated due to the COVID-19 pandemic (International Monetary Fund (IMF), 2021). The Maldives featured among countries with high adaptation costs and limited fiscal space even before the COVID-19 (International Monetary Fund (IMF), 2021). With worsening of the growth-debt trade-off post pandemic, financing adaptation costs would require further strengthening of policies—domestic revenue mobilization, expenditure rationalization, a prioritization of adaptation investment, and/or mobilization of grant and concessional financing (International Monetary Fund (IMF), 2022).

The increased likelihood of adverse climate-change-related shocks calls for building climate-change resilient infrastructure in the Maldives. Building resilient infrastructure will yield dividends and cost-savings under worsened climate conditions. Fulfilling these infrastructure needs requires a comprehensive analysis of investment plans with respect to their degree of climate resilience, their impact on future economic prospects, and their funding costs and sources. Melina and Santoro (2021), calibrating a theoretical model for the Maldives, show that there is a significant dividend associated with building resilient infrastructure8. Under worsened climate conditions, the cumulative output gain from investing in more resilient technologies increases up to a factor of two. Firstly, building resilient infrastructure in the Maldives can halve the losses in terms in GDP (Table 2) at the trough triggered by a natural disaster. Investing in resilient infrastructure yields a dividend even before a disaster occurs, as its greater gross rate of return and durability imply that its net return is higher (the greater durability is captured by a smaller depreciation rate of resilient infrastructure relative to that of standard infrastructure). The additional tax pressure required for reconstruction in the case of standard infrastructure would be (politically) infeasible. The supplementary increase in tax revenues should be of the tune of 6–7 percentage points of GDP, in the aftermath of a shock. Secondly, financing public investment (in standard or adaptation infrastructure) with higher taxation would lead to a sacrifice in terms of GDP, and private consumption and investment in the ramp up of the investment effort9. Grant financing can reduce this cost or eliminate it if it covers the investment plan in full. Melina and Santoro (2021) also highlight that it is more financially convenient for donors to help build resilience prior to the occurrence of a natural disaster rather than helping to finance the reconstruction afterwards.

The World Bank noted that many strategies are “needed to explore potential financing for scaling nature action, including policy, debt, and non-debt instruments. There isn't a single financial instrument that can provide all the financing needed to plug the gap in nature or climate financing. Rather, a broad range of financial structures and investment types should be considered, of course paying close attention to debt-limits, implications on concessional resources, macro- and fiscal realities,” (World Bank, 2022).

Access to concessional climate finance remains a challenge, however. Authorities stated that there are very few projects that are under global climate funds because it is difficult to access these funds owing to the bureaucratic process and the need for scientific evidence to qualify as climate ready (F and D, 2021). Some of the main obstacles to timely access to global climate funds seem to be the lack of capacity to satisfy preconditions for climate finance, including provision of scientific evidence and involved paperwork. In this context, given that the Maldives has limited fiscal space, particularly post COVID-19, the authorities reiterated their request to the international community to step up cooperation efforts through financial assistance, capacity development, and facilitation of access to global climate finance and at concessional rates (F and D 2021).

Nations around the world can share common objectives for the sustainable management of marine ecosystems. They include (i) engaging in mitigation solutions to increased GHG concentrations in the atmosphere, while supporting adaptation in developing states and particularly SIDS; (ii) regulating and monitoring fish stock to maintain stocks under the targeted levels (science-based limits) while measuring, protecting and controlling adjacent ecosystems; (iii) leading integrated planning processes to avoid and decrease land-based sources of ocean pollution, emphasizing on waste treatment effectiveness; (iv) monitoring and controlling pollution from non-living resources, including shipping; and (v) integrating marine spatial planning and coastal zone management in physical reconstruction of the coastline (UN Environment, 2019). Policymakers must use both local knowledge systems in the field and ocean task forces driven by scientific knowledge to construct policy. International leadership is needed to ratify and implement international treaties, agreements and conventions (Stuchtey et al., 2020).

Coral reefs are classified as a priority and transboundary concern. However, the majority of coral reefs are under national jurisdiction and therefore challenging to characterize as global public goods even if they have the characteristics of common pool resources, despite being under threat from cumulative impacts of a range of human activities. It has been defined that shared concern, despite coral reefs not being a shared resource, can be the foundation for collective action, as outlined in the rationale of the Convention on Biological Diversity. In 2016, the United Nations Environment Assembly emphasized the need for protection of oceanic ecosystems through international cooperation, calling for an increase in governmental efforts to encourage financial and technical support from donors (UNEA, 2016; UN Environment, 2019). The idea of generating a supranational ocean agency was presented on the UNESCO program “Man and the Biosphere” (Bridgewater, 2016). This ocean agency can be generated by UN resolution or can be generated by founding groups that can stimulate other stakeholders to get involved (Stuchtey et al., 2020).

There has never been a more urgent need for national strategies coherently put together within a global vision for a resilient ocean, from coral reef ecosystems to the global climate system. Initiatives like the UN decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development (2021–2030) and the UN Decade of Ecosystem Restoration (2021–2030) present an opportunity for such structured action, including by aggregating funding related to coral reef management on local, national and international scales. Addressing financial and anthropogenic capacity challenges is now critical. Limited capacity is a central barrier to international reef-related commitments in different countries, particularly in SIDS (Small Island Developing States), less developed countries, and some developing countries (UN Environment, 2019).

As mentioned earlier, funding, international cooperation, local integration and stakeholder participation are urgently needed. Despite the programmes already in place, climate change and human activities make it imperative to accelerate technological support, policies, and tools to improve the protection, conservation, and management of coral reefs. Even though coral reefs are only a small part of the ocean and are only located in a few countries, the participation of all countries is crucial, as coral reef protection and management affects everyone directly and indirectly.

The Government of Maldives, the Waitt Institute, and City Facilitators have collaborated under the Healthy oceans|Noo Raajje|Maldives initiative, is helping. Positioning the Maldives as Global Blue Economy Leader: Phase 2 Blueprint 2. Blueprint 2, explores ways of leveraging pension funds and social housing as tools for sustainable economic development. It presents business cases as well as recommendations for structural changes and would help the Maldivian economy to diversify away from tourism toward:

• Natural capital—CO2 ecosystem service trading and Marine Protected area.

• Island Food—Vertical farming, Mariculture, Premium Branding and Value Addition to Fisheries.

• Clean Energy—Floating Solar and Electric Vehicles.

• Integrated Tourism—Wellness Tourism and Hospitality Academy.

Climate change and anthropic activities have been shown to affect many biological marine ecosystems and their services adversely, including coral reefs. While the exact biological and chemical impacts of climate change and ocean acidification on coral reefs remain unclear in the Maldives, multiple stressors, including epizootic disease, are affecting coral reef communities, resulting in a rapid decrease in diversity, area coverage and ecological interactions in reef ecosystems. The Maldivian reefs have been among the most affected areas in the world by climate change, thermal stressors, and related coral bleaching episodes with 60–100% coral mortality reported. Investing in coral reef restoration, would help to re-build resilience through preservation of biodiversity and secure ecosystem services supporting coastal protection, fisheries, food security, tourism, among others (Lam et al., 2019). Coordinated efforts from the government, organizations and all affected stakeholders are needed to improve conservation strategies toward facilitate the livelihoods and well-being of the Maldivian population. Therefore, a sustainable plan with shared benefits for all stakeholders paired with an updated set of regulations is needed in the different sectors impacted by coral reefs degradation. Long-term monitoring mechanisms for coral reef protection must rely on the active participation of local communities. The Maldivian government is currently implementing the SAP 2019–2023, which provides a central policy framework aiming to monitor progress in different sectoral areas in order to enhance the livelihoods and wellbeing in the country. This framework includes metrics of wellbeing across diverse sectors, such as blue economy, caring state, family dignity, good governance, and decentralization, involving topics like clean energy, fisheries and marine resources, tourism, health, education, sports, gender equality, public service reforms, among others. However, the pace of its implementation remains slow due to a lack of facilitating regulations and limited access to concessional climate finance; this framework and its underlying programs in the SAP should therefore adapt and morph into early warning systems, incident response plans and communications strategies. Some of the main obstacles to timely access to global climate funds appears to be the lack of capacity to satisfy preconditions for climate finance, including provision of scientific evidence and involved paperwork. Many strategies are needed to explore financing tools to scale-up nature action, including policy, debt, and non-debt instruments (World Bank, 2022) and debt-nature swaps could also be considered in the overall scheme. Alternative sources of funding for specific ecosystem services include conservation trust funds that can provide targeted financial support for specific ecosystems (UN Environment, 2019), such as the Global Fund for Coral Reef (GFCR), which is a 10-year financial instrument specifically created to restore and protect coral reefs ecosystems.

The ocean is the cornerstone of the human development of small island developing states (SIDS), making coral reefs the “rainforests of the sea,” able to provide benefits to millions of people worldwide (ORG, 2007; Mulhall, 2008; Mongbay, 2011). The Maldives' economic development relies heavily on the islands' ecosystems and particularly the coral reefs, which are under continuous exposure from climate change threats. It is imperative that these challenges are met urgently and managed sustainably which local communities, whose inclusion can change the perception of protected areas as unproductive to a productive national asset. Coral reefs are classified as a priority and transboundary concern, therefore this sustainable management priority is one of global concern and not restricted to Maldivian waters only. There is an urgent need to put together national strategies coherently within a global vision for a resilient ocean, from coral reef ecosystems to the global climate system. Initiatives like the UN decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development (2021–2030) and the UN Decade of Ecosystem Restoration (2021–2030) present an opportunity for such structured action, particularly as they aggregate funding related to coral reef management on local, national and international scales as financial and anthropogenic capacity challenges remain a major hurdle to effective conservation. Indeed, limited capacity is a central barrier to international reef-related commitments in different countries, particularly in SIDS (Small Island Developing States), less developed countries, and some developing countries (UN Environment, 2019). Multilateral organizations like the International Monetary Fund together with other Multilateral Development Banks are well placed to provide financial solutions and capacity development and scale up nature action by leveraging private sector participation. A globally relevant sustainable management of marine ecosystems should rely on (i) engaging in mitigation solutions to increased GHG concentrations in the atmosphere, while supporting adaptation in developing states and particularly SIDS; (ii) regulating and monitoring fish stock to maintain stocks under the targeted levels (science-based limits) while measuring, protecting and controlling adjacent ecosystems; (iii) leading integrated planning processes to avoid and decrease land-based sources of ocean pollution, emphasizing on waste treatment effectiveness; (iv) monitoring and controlling pollution from non-living resources, including shipping; and (v) integrating marine spatial planning and coastal zone management in physical reconstruction of the coastlines.

NH leaded the paper and contributed to it. RB, MC, and LL contributed to the different sections. JC helped to reorganize the paper and edited the scientific sections. DS contributed to the sections and checked the information about the Maldives. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frevc.2023.1110214/full#supplementary-material

CFA, conservation finance alliance; EEZ, exclusive economic zone; GDP, gross domestic product; GEF, global environmental fund; GFCR, the global fund for coral reef; GHGs, green house gases; GPI, genuine progress indicator; IMF, international monetary fund; IPBES, intergovernmental science-policy platform on biodiversity and ecosystem services; IPCC, intergovernmental panel on climate change; MEA, millennium ecosystem assessment; MEE, ministry of environment and energy; NAPA, national adaptation plan of action; PES, payment for ecosystem services; PIM, public investment management; PIMA TA, public investment management assessment—technical assistance; SAP, strategic action plan; SDGs, sustainable development goals; SIDS, small islands developing states; SLR, sea level rise; SST, sea surface temperature; TEEB, the economics of ecosystems and biodiversity foundations; UN, United Nations; UNDP, United Nations Development Programme; UNEA, United Nations Environment Assembly; UNESCO, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization; UNFCCC, United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change; WTO, World Trade Organization; WWF, World Wide Fund for Nature.

1. ^Arc Center of Excellence Coral Reef Studies 2018. Coral reefs protect coasts from severe storms. April.

2. ^Stanford Report 2014. Coral Reefs Provide Protection from Storms and Rising Sea Levels, Stanford Research Finds. The research was conducted by scientists from the University of Bologna, the Nature Conservancy, the U.S. Geological Survey, Stanford and the University of California, Santa Cruz.

3. ^There is three biosphere reserve in the Maldives: Baa Atoll Biosphere Reserve designated in 2011, Addu Atoll Biosphere Reserve designated in 2020, Fuvahmulah Biosphere Reserve designated in 2020.

4. ^The Government of Maldives. National Adaptation Programme of Action (NAPA).

5. ^NAPA was prepared with support from the Global Environment Facility (GEF) and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Preparations for this programme began in October 2004 and while the process was halted because of the South Asian tsunami of December 2004, a follow-up started again in February 2006. On mitigation, the Update of Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) of Maldives (2020) by the Ministry of Environment lays out plans to reduce 26 percent of emissions by 2030 and to strive to achieve net zero by 2030, if there is adequate international support and assistance. To achieve the emission reduction targets, the NDC sets forth ambitious plans to increase the share of renewable energy in the energy mix through various initiatives.

6. ^(i) Climate Change Emergency (2021), (ii) Nationally determined Contribution (NDC) 2020, (iii) Strategic Action Plan (2019–2023) (2019), (iv) Maldives Climate Change Policy Framework (MCCPF) (2015), (v) Disaster Management Act (2007), and (vi) National Adaptation Program of Action (2006).

7. ^On mitigation, the Maldives recently adopted the Climate Emergency Act, adopted (29th April 2021). It provides a complete framework for Maldives' ambitious plan to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2030. The Act mandates to submit the subsequent year's national carbon budget to the Parliament for approval 3 months before the end of each year.

8. ^Melina and Santoro (2021).

9. ^The Maldives Monetary Authority (MMA) has recently joined IFC's Sustainable Banking Network (SBN, January 2021). The primary objective was to formulate a National Sustainable Financing Framework with a clear roadmap to support broad based adoption of sustainable finance policies, including both improved environment and social risk management by financial institutions.

Ali, K., Shimal, M. (2016). Review of the Status of Marine Turtles in the Maldives. Kochi: Marine Research Centre, Ministry of Fisheries and Agriculture.

Bayraktarov, E., Saunders, M. I., Abdullah, S., Mills, M., Beher, J., Possingham, H. P., et al. (2016). The cost and feasibility of marine coastal restoration. Ecol. Appl. 26, 1055–1074. doi: 10.1890/15-1077

Bisaro, A., de Bel, M., Hinkel, J., Kok, S., and Bouwer, L. M. (2020). Leveraging public adaptation finance through urban land reclamation: cases from Germany, the Netherlands and the Maldives. Clim. Change 160, 671–689. doi: 10.1007/s10584-019-02507-5

Braat, L. C., and de Groot, R. (2012). The ecosystem services agenda: bridging the worlds of natural science and economics, conservation and development, and public and private policy. Ecosyst. Serv. 1, 4–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2012.07.011

Bridgewater, P. (2016). The man and biosphere programme of UNESCO: rambunctious child of the sixties, but was the promise fulfilled? Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 19, 1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2015.08.009

Burke, L., Reytar, K., Spalding, M., and Perry, A. (2011). Reefs at Risk Revisited. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute, 114.

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) (2022). The World Factbook: Maldives. Environment-International Agreements. Washington, DC: Central Intelligence Agency. Available online at: https://www.cia.gov/the-worldfactbook/countries/maldives/#environment (accessed January 7, 2023).

Claudet, J., Bopp, L., Cheung, W. W. L., Devillers, R., Escobar-Briones, E., Haugan, P., et al. (2020). A roadmap for using the UN decade of ocean science for sustainable development in support of science, policy, and action. One Earth 2, 34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.oneear.2019.10.012

Collins, N. (2013). Advocacy for Marine Management: Contributions to a Policy Advocacy Initiative in the Maldives. Lutz: Capstone Collection.

Constitution of the Republic of Maldives (2008). Refworld. Seoul: Constitution of the Republic of Maldives. Available online at: https://hwww.refworld.org/docid/48a971452.html (accessed February 26, 2022).

Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) (2022). Country Profiles: The Maldives. New York, NY: Convention on Biological Diversity. Available online at: https://www.cbd.int/countries/?country=mv (accessed January 7, 2023).

Costanza, R., De Groot, R., Braat, L., Kubiszewski, I., Fioramonti, L., Sutton, P., et al. (2017). Twenty years of ecosystem services: How far have we come and how far do we still need to go? Ecosyst. Serv. 28, 1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2017.09.008

dell'Agnese, E. (2019). ‘Islands within Islands?' The Maldivian resort, between segregation and integration. Tour. Enclaves 21, 749–765. doi: 10.1080/14616688.2018.1505941

Dhunya, A., Huang, Q., and Aslam, A. (2017). Coastal habitats of Maldives: status, trends, threats, and potential conservation strategies. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res. 8, 47–62. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Aminath-Dhunya/publication/337673624_Coastal_Habitats_of_Maldives_Status_Trends_Threats_and_potential_conservation_Strategies/links/5f3fe6d1458515b7293a0a11/Coastal-Habitats-of-Maldives-Status-Trends-Threats-and-potential-conservation-Strategies.pdf

Di Fiore, V., Punzo, M., Cavuoto, G., Galli, P., Mazzola, S., Pelosi, N., et al. (2020). Geophysical approach to study the potential ocean wave-induced liquefaction: an example at Magoodhoo Island (Faafu Atoll, Maldives, Indian Ocean). Mar. Geophys. Res. 41, 1–19. doi: 10.1007/s11001-020-09408-8

Domroes, M. (2001). Conceptualising state-controlled resort island for an environment-friendly development of tourism: the Maldivian experience. Singap. J. Trop. Geogr. 22, 122–137. doi: 10.1111/1467-9493.00098

Dryden, C., Basheer, A., Grimsditch, G., Musthaq, A., Newman, S., Shan, A., et al. (2020). A Rapid Assessment of Natural Environments in the Maldives. Gland: IUCN and Government of Maldives.

Duvat, V. K. (2020). Human-driven atoll island expansion in the Maldives. Anthropocene 32, 100265. doi: 10.1016/j.ancene.2020.100265

Encyclopædia Britannica. (2020). Maldives. The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. Chicago: Encyclopaedia Britannica. Available online at: http://www.britannica.com/place/ (accessed February 7, 2023).

Fallati, L., Savini, A., Sterlacchini, S., and Galli, P. (2017). Land use and land cover (LULC) of the Republic of the Maldives: first national map and LULC change analysis using remote-sensing data. Environ. Monit. Assess. 189, 1–15. doi: 10.1007/s10661-017-6120-2

Frazier, J., Salas, S., and Didi, N. T. H. (1984). Marine Turtles in the Maldive Archipelago. Malé: Ministry of Fisheries and Agriculture, 53.

Galli, P., Montano, S., Seveso, D., and Maggioni, D. (2021). “Coral reef biodiversity of the Maldives,” in Atoll of the Maldives: Nissology and Geography, eds S. Malatesta, M. di Friedberg, S. Zubair, D. Bowen, M. Mohamed (Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers), 196.

Global Edge (2023). Maldives: Economy. Michigan: Michigan State University. Available online at: https://globaledge.msu.edu/countries/maldives/economy#source_1 (accessed January 6th 2023).

Global Funds for Coral Reefs (GFCR). (2021). Mobilising Effective Reef Conservation Efforts. Bahamas: Global Funds for Coral Reefs. Available online at: https://globalfundcoralreefs.org/ (accessed February 7, 2023).

Hein, M., Couture, F., and Scott, C. M. (2018). “Ecotourism and coral reef restoration,” in Coral Reefs: Tourism, Conservation and Management (New York, NY: Routledge). doi: 10.4324/9781315537320-10

Hughes, T. P., Anderson, K. D., Connolly, S. R., Heron, S. F., Kerry, J. T., Lough, J. M., et al. (2018a). Spatial and temporal patterns of mass bleaching of corals in the Anthropocene. Science 359, 80–83. doi: 10.1126/science.aan8048

Hughes, T. P., Kerry, J. T., Baird, A. H., Connolly, S. R., Dietzel, A., Eakin, C. M., et al. (2018c). Global warming transforms coral reef assemblages. Nature 556, 492–496. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0041-2

Hughes, T. P., Kerry, J. T., and Simpson, T. (2018b). Large-scale bleaching of corals on the Great Barrier Reef. Ecology 99, 2092. doi: 10.1002/ecy.2092

Ibrahim, N., Mohamed, M., Basheer, A., Ismail, H., Nistharan, F., Schmidt, A., et al. (2017). Status of Coral Bleaching in the Maldives in 2016. Malé: Marine Research Centre.

International Coral Reef Initiative (ICRI) (2021). Maldives: National Coral Reef Initiative. Barbados: International Coral Reef Initiative. Available online at: https://icriforum.org/members/maldives/ (accessed January 7th, 2023).

International Monetary Fund (IMF) Finance and Development. (2021). No Higher Ground. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2022). IMF Staff Concludes Visit to the Maldives. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

IPCC (2014). “Annex II: Glossary [Mach, K.J., S. Planton and C. von Stechow (eds.)],” in Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, R.K. Pachauri and L.A. Meyer (eds.)] (Geneva: IPCC), 117-130.

Iyer, V., Mathias, K., Meyers, D., Victurine, R., and Walsh, M. (2018). Finance Tools for Coral Reef Conservation: A Guide. Available online at: https://www.icriforum.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/50+Reefs+Finance+Guide.pdf (accessed Februrary 7, 2023).

Jaleel, A. (2013). The status of the coral reefs and the management approaches: the case of the Maldives. Ocean Coast. Manag. 82, 104e118. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2013.05.009

Kothari, U., and Arnall, A. (2017). Contestation over an island imaginary landscape: the management and maintenance of touristic nature. Environ. Plan. A 49, 980–998. doi: 10.1177/0308518X16685884

Lam, V. W. Y., Chavanich, S., Djoundourian, S., Dupont, S., Gaill, F., Holzer, G., et al. (2019). Dealing with the effects of ocean acidification on coral reefs in the Indian Ocean and Asia. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 28, 100560. doi: 10.1016/j.rsma.2019.100560

Maggioni, D., Galli, P., Berumen, M. L., Arrigoni, R., Seveso, D., and Montano, S. (2017b). Astrocoryne cabela, gen. nov. et sp. nov. (Hydrozoa: Sphaerocorynidae), a new sponge-associated hydrozoan. Invert. Syst. 31, 734–746. doi: 10.1071/IS16091

Maggioni, D., Montano, S., Seveso, D., and Galli, P. (2016). Molecular evidence for cryptic species in Pteroclava krempfi (Hydrozoa, Cladocorynidae) living in association with alcyonaceans. Syst. Biodiv. 14, 484–493. doi: 10.1080/14772000.2016.1170735

Maggioni, D., Puce, S., Galli, P., Seveso, D., and Montano, S. (2017a). Description of Turritopsoides marhei sp. nov. (Hydrozoa, Anthoathecata) from the Maldives and its phylogenetic position. Mar. Biol. Res. 13, 983–992. doi: 10.1080/17451000.2017.1317813

Maggioni, D., Schuchert, P., Arrigoni, R., Hoeksema, B. W., Huang, D., Strona, G., et al. (2021). Integrative systematics illuminates the relationships in two sponge-associated hydrozoan families (Capitata: Sphaerocorynidae and Zancleopsidae). Contr. Zool. 90, 487-525. doi: 10.1163/18759866-bja10023

Malatesta, S., and Di Friedberg, M. S. (2017). Environmental policy and climate change vulnerability in the Maldives: from the 'lexicon of risk' to social response to change. Island Stud. J. 12, 53–70. doi: 10.24043/isj.5

Maldives Ministry of Tourism (2021). Tourism Yearbook. Republic of Maldives. Tourism Research and Statistics Section. Malé. Available online at https://www.tourism.gov.mv/dms/document/2f11c02edec48b0fa37014122e7c39e6.pdf (accessed November 7, 2022).

Maldives National Bureau of Statistics (2020). Monthly Economic Indicators. Malé: Ministry of Tourism, Ministry of Fisheries, Marine Resources and Agriculture, Ministry of Finance, Maldives Monetary Authority, Maldives Customs Service, Maldives Airports Company Limited, Communication Authority of Maldives, World Bank Database. Available online at: https://www.finance.gov.mv/public/attachments/411cq33lXEkl16Vu06xvK9B10X9igdvazAi3W9nO.pdf (accessed February 7, 2023).

Marshall, P., Abdulla, A., Ibrahim, N., Naeem, R., Basheer, A. (2017). Maldives Coral Bleaching Response Plan 2017. Malé: Marine Research Centre.

MEE (2016). Second National Communication of Maldives to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Washington, DC: Ministry of Environment and Energy.

MEE (2020). Update of Nationally Determined Contribution of Maldives. Washington, DC: Ministry of Environment and Energy.

Melina, M. G., Santoro, M. (2021). Enhancing Resilience to Climate Change in the Maldives. IMF Working Paper No. 2021/096. doi: 10.5089/9781513582443.001

Ministry of Fisheries Marine Resources, Agriculture. (2023). Projects. “Blue Economy” Development Project in the Maldivian Fisheries Sector/Sustainable Fisheries Resources Development Project. Male: Ministry of Fisheries, Marine Resources and Agriculture. Available online at: https://www.gov.mv/en/organisations/ministry-of-fisheries-marine-resourcesand-agriculture (accessed January 7th, 2023).

Montalbetti, E., Fallati, L., Casartelli, M., Maggioni, D., Montano, S., Galli, P., et al. (2022). Reef complexity influences distribution and habitat choice of the corallivorous seastar Culcita schmideliana in the Maldives. Coral Reefs 41, 253–264. doi: 10.1007/s00338-022-02230-1

Montalbetti, E., Saponari, L., Montano, S., Maggioni, D., Dehnert, I., Galli, P., et al. (2019). New insights into the ecology and corallivory of Culcita sp. (Echinodermata: Asteroidea) in the Republic of Maldives. Hydrobiologia 827, 353–365. doi: 10.1007/s10750-018-3786-6

Montano, S., Arrigoni, R., Pica, D., Maggioni, D., Puce, S. (2015a). New insights into the symbiosis between Zanclea (Cnidaria, Hydrozoa) and scleractinians. Zool. Scrip. 44, 92–105. doi: 10.1111/zsc.12081

Montano, S., Maggioni, D., Arrigoni, R., Seveso, D., Puce, S., and Galli, P. (2015b). The hidden diversity of Zanclea associated with scleractinians revealed by molecular data. PLoS ONE 10, e0133084. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133084

Montano, S., Seveso, D., Maggioni, D., Galli, P., Corsarini, S., and Saliu, F. (2020). Spatial variability of phthalates contamination in the reef-building corals Porites lutea, Pocillopora verrucosa and Pavona varians. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 155, 111117. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2020.111117

Montano, S., Strona, G., Seveso, D., and Galli, P. (2012). First report of coral diseases in the Republic of Maldives. Dis. Aquat. Org. 101, 159–165. doi: 10.3354/dao02515

Montano, S., Strona, G., Seveso, D., and Galli, P. (2013). Prevalence, host range, and spatial distribution of black band disease in the Maldivian Archipelago. Dis. Aquat. Org. 105, 65–74. doi: 10.3354/dao02608

Montano, S., Strona, G., Seveso, D., Maggioni, D., and Galli, P. (2014). Slow progression of black band disease in Goniopora cf. columna colonies may promote its persistence in a coral community. Mar. Biodiv. 45, 857–860. doi: 10.1007/s12526-014-0273-9

Montano, S., Strona, G., Seveso, D., Maggioni, D., Galli, P. (2015c). Widespread occurrence of coral diseases in the central Maldives. Mar. Freshw. Res. 67, 1253–1262. doi: 10.1071/MF14373

Mukhjerjee, S., and Chakraborty, D. (2013). Is environmental sustainability influenced by socioeconomic and sociopolitical factors? Cross-country empirical evidence. Sustain. Dev. 21, 353–371. doi: 10.1002/sd.502

Mulhall, M. (2008). Saving the rainforests of the sea: an analysis of international efforts to conserve coral reefs. Duke Environ. Law Policy Forum 19, 321e351. Available online at: https://scholarship.law.duke.edu/delpf/vol19/iss2/6

Naseer, A., and Hatcher, B. (2004). Inventory of the Maldives' coral reefs using morphometrics generated from Landsat ETM+ imagery. Coral Reefs 23, 161–168. doi: 10.1007/s00338-003-0366-6

National Adaptation Programme of Action (NAPA). (2006). The Government of Maldives. Bangladesh: National Adaptation Programme of Action.

ORG (2007). Coral Reefs: Rainforests of the Sea. O.R.G. Educational Films. Poway: Ocean Research Group. Available online at: http://www.oceanicresearch.org/education/films/crrainspt.html (accessed February 7, 2023).

Pancrazi, I., Ahmed, H., Cerrano, C., and Montefalcone, M. (2020). Synergic effect of global thermal anomalies and local dredging activities on coral reefs of the Maldives. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 160, 111585. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2020.111585

Perry, C. T., and Morgan, K. M. (2017). Bleaching drives collapse in reef carbonate budgets and reef growth potential on southern Maldives reefs. Nature 7, 40581. doi: 10.1038/srep40581

Pichon, M., and Benzoni, F. (2007). Taxonomic re-appraisal of zooxanthellate Scleractinian Corals in the Maldive Archipelago. Zootaxa 1441, 21–33. doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.1441.1.2

Quintela, C., Thomas, L., and Robin, S., on behalf of the Conservation Finance Alliance. (2003). “Proceedings of the workshop stream, building a secure financial future: finance and resources,” in Proceedings of the Vth IUCN World Parks Congress (Durban: Conservation Finance Alliance).

Radovanović, M., and Lior, N. (2017). Sustainable economic–environmental planning in Southeast Europe: beyond-GDP and climate change emphases sustainable development. Sust. Dev. 25, 508–594. doi: 10.1002/sd.1679

Rizzi, C., Seveso, D., Galli, P., and Villa, S. (2020). First record of emerging contaminants in sponges of an inhabited island in the Maldives. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 156, 111273. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2020.111273

Saliu, F., Biale, G., Raguso, C., La Nasa, J., Degano, I., Seveso, D., et al. (2022). Detection of plastic particles in marine sponges by a combined infrared micro-spectroscopy and pyrolysis-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry approach. Sci. Total Environ. 819, 152965. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.152965

Saliu, F., Montano, S., Garavaglia, M. G., Lasagni, M., Seveso, D., and Galli, P. (2018). Microplastic and charred microplastic in the Faafu Atoll, Maldives. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 136, 464–471. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.09.023

Saponari, L., Montalbetti, E., Galli, P., Strona, G., Seveso, D., Dehnert, I., et al. (2018). Monitoring and assessing a 2-year outbreak of the corallivorous seastar Acanthaster planci in Ari Atoll, Republic of Maldives. Environ. Monit. Assess. 190, 1–12. doi: 10.1007/s10661-018-6661-z

Saponari, L., Montano, S., Seveso, D., and Galli, P. (2014). The occurrence of an Acanthaster planci outbreak in Ari Atoll, Maldives. Mar. Biodiv. 45, 599–600. doi: 10.1007/s12526-014-0276-6

Schoenaker, R., Hoekstra, R., and Smits, J. P. (2015). Comparison of measurement systems for sustainable development at the national level. Sustain. Dev. 23, 285–300. doi: 10.1002/sd.1585

Seveso, D., Arrigoni, R., Montano, S., Maggioni, D., Orlandi, I., Berumen, M. L., et al. (2020). Investigating the heat shock protein response involved in coral bleaching across scleractinian species in the central Red Sea. Coral Reefs 39, 85–98. doi: 10.1007/s00338-019-01878-6

Seveso, D., Montano, S., Reggente, M. A. L., Orlandi, I., Galli, P., and Vai, M. (2015). Modulation of Hsp60 in response to coral brown band disease. Dis. Aquat. Org. 115, 15–23. doi: 10.3354/dao02871

Seveso, D., Montano, S., Strona, G., Orlandi, I., Vai, M., and Galli, P. (2012). Up-regulation of Hsp60 in response to skeleton eroding band disease but not by algal overgrowth in the scleractinian coral Acropora muricata. Mar. Environ. Res. 78, 34–39. doi: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2012.03.008

Shareef, A. (2010). Fourth National Report to the Convention on Biological Diversity Maldives. Malè: Ministry of Housing and Environment.

Spalding, M. D., Ravilious, C., and Green, E. P. (2001). World Atlas of Coral Reefs. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Stojanov, R., DuŽí, B., Kelman, I., Němec, D., and Procházka, D. (2017). Local perceptions of climate change impacts and migration patterns in Malé, Maldives. Geogr. J. 183, 370–385. doi: 10.1111/geoj.12177

Stuchtey, M., Vincent, A., Merkl, A., Bucher, M., Haugan, P. M., Lubchenco, J., et al. (2020). “Ocean solutions that benefit people, nature and the economy,” in High Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy (Washington, DC: World Resources Institute). Available online at: www.oceanpanel.org/ocean-solutions (accessed February 7, 2023).

Sully, S., Burkepile, D. E., Donovan, M. K., Hodgson, G., and van Woesik, R. (2019). A global analysis of coral bleaching over the past two decades. Nat. Commun. 10, 1–5. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09238-2

TEEB Foundations (2010). The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity: Ecological and Economic Foundations. London: Earthscan.

The Commonwealth Blue Chart. (2018). Shared Values, Shared Ocean: A Commonwealth Commitment to Work Together to Protect and Manage Our Ocean. Edmonton: The Commonwealth Blue Chart.

Tkachenko, K. S. (2012). The northernmost coral frontier of the Maldives: the coral reefs of Ihavandippolu atoll under long-term environmental change. Mar. Environ. Res. 82, 40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2012.09.004

Tkachenko, K. S. (2015). Impact of repetitive thermal anomalies on survival and development of mass reef-building corals in the Maldives. Mar. Ecol. 36, 292–304. doi: 10.1111/maec.12138

UN Environment (2019). Analysis of Policies Related to the Protection of Coral Reefs-Analysis of Global and Regional Policy Instruments and Governance Mechanisms Related to the Protection and Sustainable Management of Coral Reefs. Nairobi: United Nations Environment Programme.

UNEA (2016). Sustainable Coral Reefs Management. New Guinea: UNEP/EA. Available online at: https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/11187/K1607234_UNEPEA2_RES12E.pd%20f?sequence=1andisAllowed=y (accessed February 7, 2023).

World Bank (2020a). The World Bank in Maldives. Geneva: World Bank. Available online at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/maldives/overview (accessed February 7, 2023).

World Bank (2020b). Population, Total: Maldives. Geneva: World Bank. Available online at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL?locations=MV (accessed February 7, 2023).

World Bank (2022). Maldives: Mobilizing Finance for Nature and Climate Resilience Workshop. Geneva: World Bank.

Zahir, H., Norman, Q., and Cargilia, N. (2010). Assessment of Maldivian Coral Reefs in 2009 After Natural Disaster. Malé: Republic of Maldives: Marine Research Centre, Ministry of Fisheries and Agriculture.

Keywords: coral reefs, climate change, mitigation, GDP, environmental plans and strategies

Citation: Hilmi N, Basu R, Crisóstomo M, Lebleu L, Claudet J and Seveso D (2023) The pressures and opportunities for coral reef preservation and restoration in the Maldives. Front. Environ. Econ. 2:1110214. doi: 10.3389/frevc.2023.1110214

Received: 28 November 2022; Accepted: 08 February 2023;

Published: 17 March 2023.

Edited by:

Helena Vieira, University of Aveiro, PortugalReviewed by:

Jesús Ernesto Arias González, National Polytechnic Institute of Mexico (CINVESTAV), MexicoCopyright © 2023 Hilmi, Basu, Crisóstomo, Lebleu, Claudet and Seveso. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nathalie Hilmi, aGlsbWlAY2VudHJlc2NpZW50aWZpcXVlLm1j

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.