- 1Department of Health Information Management, School of Health Management and Information Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

- 2Gastrointestinal and Liver Diseases Research Center, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Background: Electronic Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (ePROMs) have emerged as valuable tools in cancer care, facilitating the comprehensive assessment of patients’ physical, psychological, and social well-being. This study synthesizes literature on the utilization of ePROMs in oncology, highlighting the diverse array of measurement instruments and questionnaires employed in cancer patient assessments. By comprehensively analyzing existing research, this study provides insights into the landscape of ePROMs, informs future research directions, and aims to optimize patient-centred oncology care through the strategic integration of ePROMs into clinical practice.

Methods: A systematic review was conducted by searching peer-reviewed articles published in academic journals without time limitations up to 2024. The search was performed across multiple electronic databases, including PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science, using predefined search terms related to cancer, measurement instruments, and patient assessment. The selected articles underwent a rigorous quality assessment using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT).

Results: The review of 85 studies revealed a diverse range of measurement instruments and questionnaires utilized in cancer patient assessments. Prominent instruments such as the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30) and the Patient Reported Outcome-Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE) were frequently referenced across multiple studies. Additionally, other instruments identified included generic health-related quality of life measures and disease-specific assessments tailored to particular cancer types. The findings indicated the importance of utilizing a variety of measurement tools to comprehensively assess the multifaceted needs and experiences of cancer patients.

Conclusion: Our systematic review provides a comprehensive examination of the varied tools and ePROMs employed in cancer care, accentuating the perpetual requirement for development and validation. Prominent instruments like the EORTC QLQ-C30 and PRO-CTCAE are underscored, emphasizing the necessity for a thorough assessment to meet the multifaceted needs of patients. Looking ahead, scholarly endeavours should prioritize the enhancement of existing tools and the creation of novel measures to adeptly address the evolving demands of cancer patients across heterogeneous settings and populations.

Introduction

Cancer care involves a complex and multifaceted approach, encompassing diagnosis, treatment, and supportive care interventions aimed at enhancing patient outcomes and quality of life. Within the landscape of cancer care, the selection and application of appropriate assessment tools are pivotal in ensuring the accuracy, reliability, and validity of patient symptom evaluations. In oncology, effectively managing symptoms related to both the disease and treatment toxicity is paramount for improving patients’ quality of life (QoL). However, under-detection and under-reporting of symptoms can hinder optimal supportive care delivery. Symptom monitoring through Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) offers an evidence-based solution to bridge the gap between clinician recognition and patient self-reporting (1). PROs offer an evidence-based solution to bridge the gap between clinician recognition and patient self-reporting, allowing for a comprehensive assessment of physical, psychological, and social well-being. PROs play a crucial role in modern oncology care, allowing patients to directly report on their health status without interpretation by clinicians (2, 3).

The emergence of electronic Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (ePROMs) represents a promising advancement, with digital solutions showing significant benefits in improving satisfaction, treatment adherence, symptom control, and overall clinical outcomes (2–4). Interest in integrating ePROMs into regular cancer care has grown, driven by a desire to enhance health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and other patient-centred outcomes (5). Dedicated tools known as Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs), such as questionnaires or standardized interview schedules, facilitate the collection of PROs and promote communication between patients and clinicians (1). These tools serve as invaluable instruments in capturing the complex interplay of disease burden, treatment efficacy, and patient-reported experiences, thereby informing tailored interventions and optimizing the delivery of patient-centred care (6, 7).

ePROM questionnaires provide standardized instruments for eliciting patient-reported information across diverse domains, such as symptomatology, functional status, and treatment satisfaction, thereby supplying clinicians and researchers with structured data to inform clinical decision-making and research endeavours. They can facilitate data collection, management, and analysis, streamlining the process of patient assessment and enabling real-time monitoring of symptoms and treatment outcomes (8) ePROMs have been utilized in questionnaires to gather information from patients, who consistently report that ePROMs are easy to comprehend, timely to fill out, and enhance communication with their oncology team. Clinicians also find that ePROMs help communication with patients, increase patient engagement in consultations, and alter clinical decision-making (5, 9).

Recent studies highlight the positive impact of ePROM interventions, offering features like remote symptom reporting and real-time clinician feedback (5). Moreover, ePROMs have shown promising benefits in improving communication, symptom control, prolonging survival, and reducing hospital admissions and emergency department visits (10). A systematic review by Warnecke et al. found that ePROMs improve the assessment of underrated physical and psychological symptom burdens among oncological patients, highlighting their potential to enhance patient-centred care. However, further research is needed to fully understand their clinical utility and address the challenges associated with their implementation (11, 12).

ePROMs have the potential to significantly enhance patient-centred cancer care by improving symptom assessment, communication, and patient engagement. The use of electronic platforms and mobile technologies enables remote data collection, enhancing accessibility, convenience, and patient engagement while minimizing logistical barriers associated with traditional paper-based assessments. Addressing these challenges requires a comprehensive approach that encompasses technological Despite the evident advantages of ePROMs, their widespread adoption and implementation present notable challenges, such as technological barriers, health literacy disparities, and concerns regarding data security, privacy, and confidentiality innovation, healthcare policy reform, and patient education initiatives to improve the equitable and ethical integration of assessment tools in cancer care. This systematic review aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of the landscape of assessment tools, questionnaires, and ePROMs utilized in cancer care, informing future research directions, clinical practice guidelines, and policy initiatives aimed at optimizing patient-centred oncology care.

To guide this analysis, the research questions for our systematic review are formulated as follows:

RQ1. What are the existing ePROMs utilized in cancer care?

RQ2. What are the key characteristics and functionalities of ePROMs used in cancer care, and how do they vary across different measurement tools?

These research questions will facilitate a systematic evaluation of the effectiveness of ePROMs in cancer care and help identify optimal strategies for their successful implementation and broader adoption.

Methods

Study design

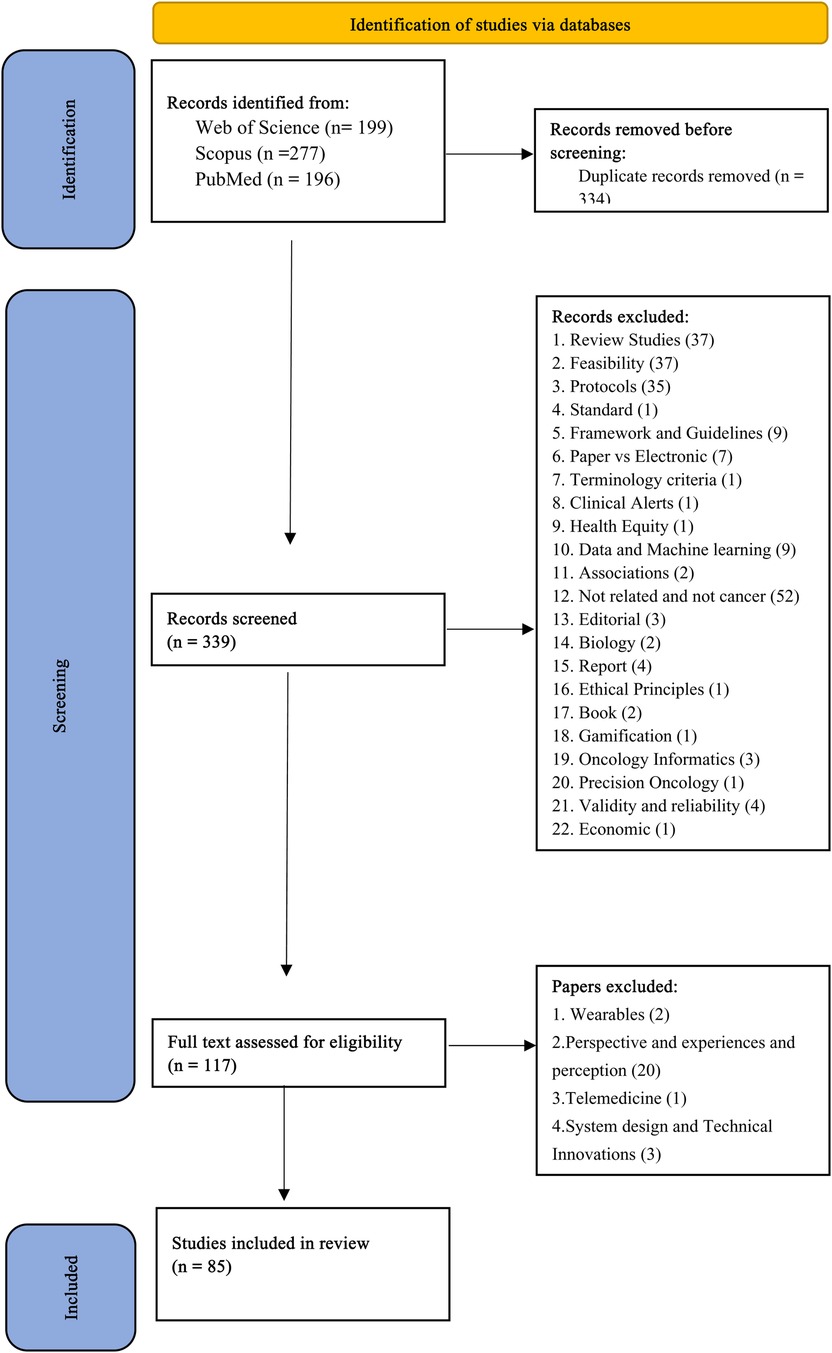

We conducted a systematic review and addressed all research articles focusing on the utilization of ePROM and their potential for patient-centred solutions in cancer care. The final report follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines for reporting systematic reviews. Our study encompasses several key steps including search strategy, inclusion and exclusion criteria, study selection, quality appraisal, and data extraction and synthesis to ensure a comprehensive and rigorous analysis of the available literature (13).

Search strategy

We searched for articles published in electronic databases up to 2024, using three databases: Scopus, Web of Science and PubMed review. The searches used the following keywords and medical subject heading (MeSH) terms in various combinations. We derived two broad themes that were then combined with the Boolean operators “AND” and “OR”. The first theme in Mesh “electronic Patient Reported Outcomes” was created by the Boolean operator “OR” to combine text words (“electronic Patient-Self Reporting”, OR “electronic Patient Reported Measures”). The second theme “Cancer” was the broad aspect created for the search strategy. Additionally, a backward snowball search will be employed to ensure comprehensive coverage of relevant articles (See Appendix Table A1).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included papers based on eligibility criteria with the following characteristics: (1) published in English, (2) papers related to electronic patient-reported outcomes, electronic patient-reported measures, and electronic self-reporting (3) articles with various research types like quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods, (4) Studies assessing quality of life, symptoms, psychological well-being, treatment satisfaction, or other relevant outcomes in cancer patients.

We excluded studies that were inaccessible in full text, studies exclusively focused on technical infrastructure, and those emphasizing paper-based or manual Patient Reported Outcome (PRO) versions, books, protocols, standards, framework and guidelines, conference proceedings, dissertations, conference abstracts, reviews, short reports, posters, newspapers, editorials and commentary. Furthermore, unrelated subjects were excluded such as feasibility, paper vs. electronic systems, terminology criteria, clinical alerts, health equity, perspective, experiences, and perception, data and machine learning, models, associations, not related and not cancer, editorial, biology, telemedicine, ethical principles, wearables, gamification, system design and technical innovations, oncology informatics, precision oncology, validity and reliability, economic. We also excluded studies lacking indicators or outcomes for cancer, not using the system as the intervention tool.

Study selection

Three investigators independently reviewed papers based on titles and abstracts in alignment with the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Irrelevant studies were removed at this stage. One reviewer (HS) conducted the data extraction, while two other reviewers (MA, SN) rechecked the accuracy of the results. All researchers then read and reviewed the full texts to make final inclusion decisions.

Quality appraisal

The selected articles underwent a rigorous quality assessment using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), comprising components for qualitative, quantitative (clinical trials), quantitative (non-clinical trials), descriptive, and mixed methods, incorporating 25 questions. Each affirmative response contributes to a 25% score. Articles surpassing the average in the number of positive responses or fully specified items are categorized as high quality. Those with positive responses ranging from 25% to 50% are classified as medium quality, while those falling below 25% are considered low quality. Following full-text screening and quality appraisal, a total of 85 articles met the inclusion criteria.

Data extraction and synthesis

An initial data extraction form was developed at this stage of the review. Data elements were extracted from each article that was organized into two sections: general items (author, year, country/state, objective, and participants) and specific items (system tools & metrics, cancer type and type of treatment). The selected papers were summarized in the final step of our methodology and important factors were identified. Thus, the statistical results of systematic reviews were described for outcomes reported in the studies. Subsequently, data extracted from these pertinent articles will undergo thorough narrative analysis and be presented in organized tables and diagrams (See Appendix Table A2).

Result

In our systematic review, we identified 672 papers, out of which 85 academic papers were included in our systematic review, providing a comprehensive exploration of electronic patient-reported outcome measures for cancer care. We present the key findings regarding the characteristics of the included studies, measurements, and their use as revealed in our systematic review (See Figure 1).

Characteristics of included studies

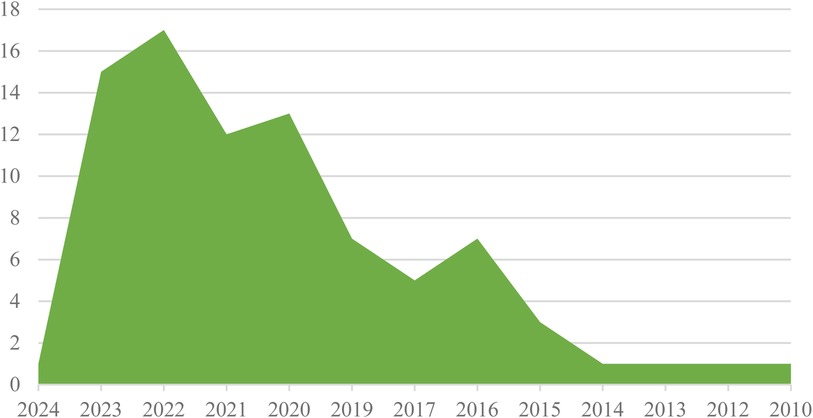

The distribution of articles about electronic patient-reported outcome measures in cancer by year indicates that the majority of publications were from the years 2022 and 2023, with 17 and 15 contributions, respectively. Additionally, there were 12 publications from 2021, 13 from 2020, 7 from 2019, 7 from 2016, 5 from 2017, 3 from 2015, and 1 publication each from 2024, 2014, 2013, 2012, and 2010 (See Figure 2).

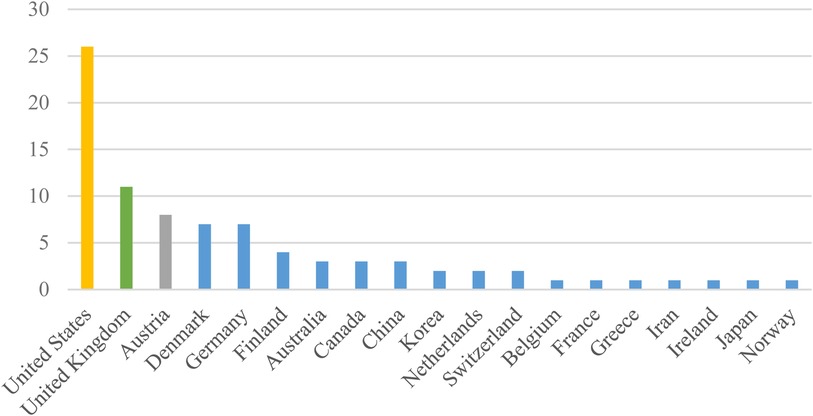

According to Figure 3, the United States emerged as the leading source of publications, followed by the United Kingdom in second place and Austria in third. Additionally, Belgium, France, Greece, Iran, Ireland, Japan, and Norway each made a single contribution.

Type of cancers

The type and frequency of cancer within the ePROM study are indicated in Figure 4. This figure highlights the prevalence of various malignancies across the studies. A total of 32 different types of cancer were identified, with breast cancer emerging as the most frequently studied.

Type of cancer treatments

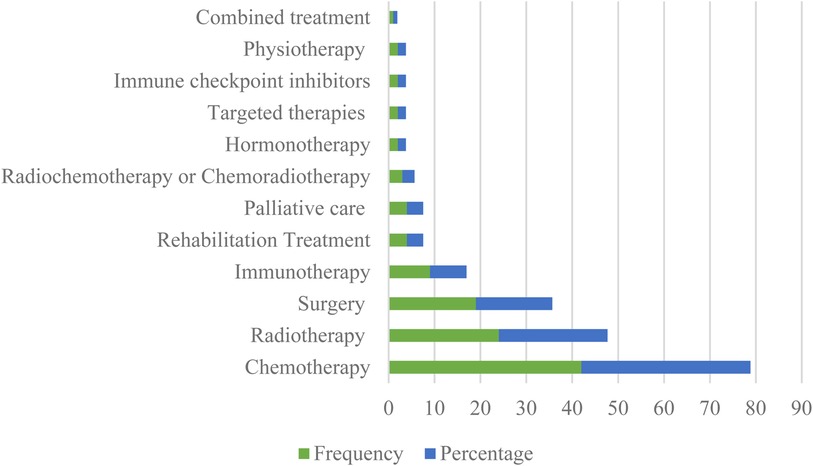

The evaluation of ePROM according to the type of cancer treatment is shown in Figure 5. In terms of the types of treatments, 114 treatments had been found and chemotherapy was the most commonly reported treatment, followed by radiotherapy and surgery.

Figure 5. Frequency distribution of studies about ePROM in cancer according to the type of treatments.

ePRO questionnaires and measures

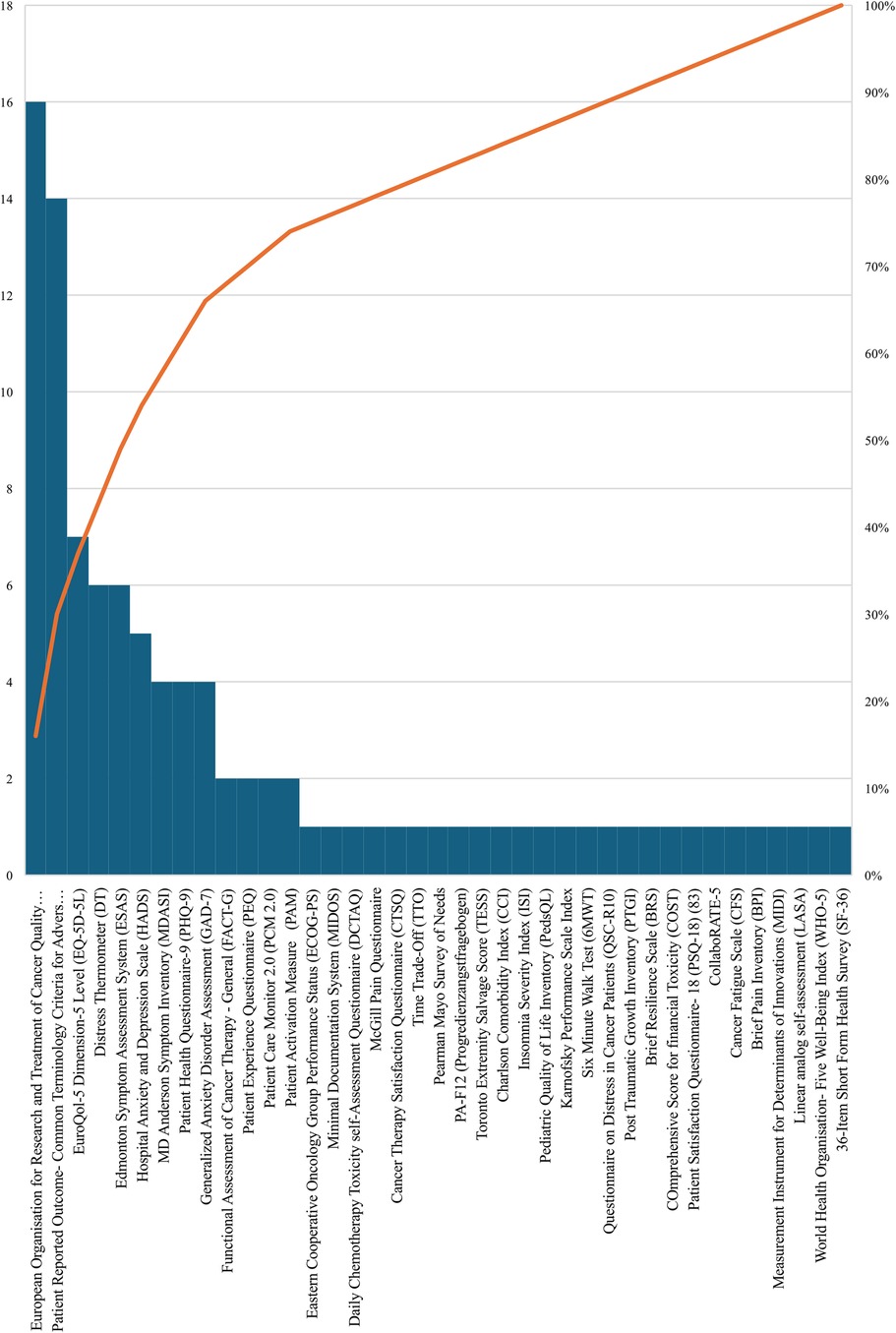

This systematic review identified a diverse range of tools, questionnaires and measurements designed to capture patients’ symptoms and outcomes in ePRO in cancer. According to Figure 6, the most frequently referenced measurements were the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30) contributing valuable insights into the physical, psychological, and social functions of cancer patients (14–29) and the Patient Reported Outcome-Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE) (29–42), providing a comprehensive approach to monitoring symptoms associated with various cancer treatments, each cited in 16 and 14 studies across different cancer types and treatment modalities, respectively.

Among other instruments, the EuroQol-5 Dimension-5 Level (EQ-5D-5l) was cited 7 times, providing significant perspectives on patients’ health status across multiple dimensions (43–49), followed by the Distress Thermometer (DT) (45, 48, 50–53) which provides a succinct yet powerful means for patients to express and quantify emotional distress levels on an 11-point Likert-type scale and the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS), tailored for advanced cancer patients to express the intensity of symptoms like pain, fatigue, and anxiety, each referenced 6 times (50–55). Furthermore, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) is cited 5 times and categorizing scores into varying levels of anxiety and depression (23, 44, 45, 56, 57), while, the MD Anderson Symptom Inventory (MDASI) is referenced 4 times (44, 45, 47, 58), providing a comprehensive patient-reported outcome measure, investigating into the severity of multiple symptoms impacting cancer patients’ daily lives. Additionally, both the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) (11, 45, 55, 59) and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Assessment (GAD-7) (11, 34, 55, 59) are each mentioned 4 times. Finally, the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy - General (FACT-G) (25, 58), the Patient Experience Questionnaire (PEQ) (16, 17), Patient Care Monitor 2.0 (PCM 2.0) (58, 60) and the Patient Activation Measure (PAM) (43, 61) are each referenced 2 times in our study. Table 1 shows a summary of ePRO instruments in oncology and their usage.

Table 2 provides a summary of disease-specific ePRO instruments in oncology and their usage. According to Table 2, our systematic review further highlighted the application of disease-specific instruments, Among these, the Quality of Life Questionnaire-Head and Neck 35 (QLQ-H&N35) was referenced in two studies (40, 66), indicating its relevance in assessing health-related quality of life in head-and-neck cancer patients. Similarly, the Quality of Life Questionnaire-Breast 23 (QLQ-BR23) European Organisation for Research appeared in two studies, emphasizing its importance in evaluating various aspects related to breast cancer, such as body image and systemic therapy side effects (16, 17). Another measurement in brain cancer was the EORTC QLQ-BN20 questionnaire (n = 1) for assessing the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in brain cancer patients extracted from EORTIC QLQ to evaluate the quality of life of cancer patients (43). Additionally, the FACT-Melanoma (FACT-M) (49) and Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—Ovary (Fact-O) (57) instruments were each cited in one study, showcasing their utility in assessing melanoma and ovarian cancer-specific factors, respectively. Moreover, the FACT-B (Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—Breast) (60), European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Ovarian Cancer 28 (EORTC QLQ-OV28) (61), and European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Colorectal 29 (EORTC QLQ-CR29) (61) were each referenced once, highlighting their role in evaluating health-related quality of life in breast, ovarian, and colorectal cancer patients, respectively. In terms of prostate cancer, the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC) and 8-item Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Advanced Prostate Symptom Index (FAPSI) have been used in monitoring prostate cancer (67).

This comprehensive analysis not only shows the prevalence of specific instruments but also indicates the diverse dimensions of patients’ experiences and outcomes that researchers aim to capture in cancer-related studies. The significant use of these tools contributes to a complete understanding of the impact of cancer and its treatment on patients’ well-being, informing tailored interventions and improving the quality of care.

Discussion

In our study, we conducted a systematic review aimed at synthesizing literature into the landscape of ePROMs and optimising patient-centred oncology care. Additionally, a distribution analysis by year indicates a majority of publications from 2022 to 2023, with the United States as the leading source. Breast cancer emerges as the most frequent cancer, with chemotherapy being the primary treatment. This study explored the electronic Patient Reported Outcomes (ePRO) measurement tools and metrics in cancer care, aiming to provide a comprehensive analysis for future research and clinical practice guidelines.

Our findings emphasize the importance of using a broad set of tools to comprehensively assess the needs and experiences of cancer patients, indicating the necessity of personalizing assessments to accurately record the multidimensional impact of cancer diagnosis and treatment on patients’ quality of life and well-being. This study identifies differences, similarities, and implications for advancing cancer patient-centered care through a comparative analysis with existing studies.

Additionally, a wide range of other instruments were identified, including generic health-related quality of life measures such as the EuroQol-5 Dimension-5 Level (EQ-5D-5l) and disease-specific modules such as the Quality of Life Questionnaire-Head and Neck 35 (QLQ-H&N35) and Quality of Life Questionnaire-Breast 23 (QLQ-BR23). The European Organization for Research and Treatment Quality of Life Test (EORTC QLQ-C30) emerges as the most widely used measure, alongside other significant tools such as PRO-CTCAE, EQ-5D-5l, DT, ESAS, HADS, and MDASI, in evaluating cancer patients. These instruments encompassed domains such as physical functioning, symptoms, psychological distress, and treatment satisfaction, providing a comprehensive evaluation of cancer patients’ experiences. This study is aligned with Samit et al.'s study, which highlights the use of an electronic patient-reported outcome measurement system to improve distress management in oncology (60). Our study explores important tools like EORTC QLQ-C30 and PRO-CTCAE as reference instruments, emphasizing the multidimensional aspects of patients’ outcomes.

Tang et al.'s comparative effectiveness study on patient-reported outcome assessment methods in cancer care complements our work by focusing on improving patient outcomes (45). While our study identifies types of tools and metrics for measuring ePROs in cancer and describes different tools, it contributes to understanding electronic measurement in cancer care. Consistent with Lee et al.'s emphasis on technological approaches like ePRO in enhancing patient participation and treatment monitoring (68) and Wagner et al.'s focus on bringing Patient Reported Outcome Measures to practice for symptom screening in ambulatory cancer care (69), our study indicates the role of technology and the use of ePROs in advancing patient-centered care and symptom monitoring in oncology.

A diverse array of studies further enriches the discourse by exploring varied contexts and interventions related to ePROM implementation. Studies by Patt et al. (70) and Harper et al. (54) delve into the impact of ePROs on adverse events, cost of care, and symptom severity, providing valuable insights into the economic and clinical implications of ePRO integration across different cancer types and treatment modalities. In addition, Gressel et al. utilized the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®) to increase referral to ancillary support services for severely symptomatic patients with gynecologic cancer (71). Moreover, investigations into the comparative effectiveness of ePROs against traditional assessment methods, as demonstrated by Warnecke et al. (11) and Moradian et al. (36), elucidate the potential advantages of leveraging technology in symptom management, treatment monitoring, and survivorship care.

In conclusion, our study contributes to a significant understanding of measurement instruments and ePRO measures in cancer care, drawing parallels with existing research to highlight key insights and implications for advancing patient-centered oncology care. By synthesizing diverse perspectives and methodologies, we aim to inform future research, clinical practice, and policy initiatives aimed at optimizing patient outcomes in oncology. Through interdisciplinary collaboration, innovative technology solutions, and patient-centered approaches, we advocate for evidence-based, holistic oncology practice, highlighting the importance of continued research and innovation in leveraging electronic patient-reported outcome (ePRO) measures to enhance cancer care delivery and patient outcomes.

Limitations

While this study offers valuable insights into electronic patient-reported outcome measures (ePROMs) in cancer care, it is important to acknowledge certain limitations. Firstly, the rapidly evolving nature of healthcare technology raises concerns about the relevance of our findings over time. Additionally, the subjective nature of tool selection across different healthcare settings introduces potential biases in our analysis. The scope of our review may also overlook niche instruments, highlighting the need for further exploration in future studies. Moreover, our survey was limited to published papers from three main databases, suggesting that this study serves as a foundational landscape for prospective research endeavours.

Secondly, while our review included the impact of ePROMs, we did not explore documents related to other technological advancements such as artificial intelligence and wearables. This represents a potential gap in our research that warrants consideration in future investigations. Thirdly, our study excluded other types of papers such as opinion pieces, editorials, and viewpoints, as well as publications in languages other than English. This may have limited the breadth of perspectives included in our analysis. Additionally, we did not solely focus on feasibility studies or patient perspective and experience tests, which could provide valuable insights into the practical implementation and user experience of ePROMs in cancer care. These considerations should be addressed in future research to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the role of technology in improving patient outcomes in oncology.

Implications

Our study presents several significant implications for both research and clinical practice in oncology. Firstly, the study underscores the pivotal role of electronic patient-reported outcome measures (ePROMs) in improving patient assessment accuracy and advancing patient-centered care delivery within oncology practice. By employing a diverse range of measurement tools tailored to different aspects of cancer care, healthcare providers can gain deeper insights into patients’ needs and experiences, enabling personalized care strategies that address individual patient concerns more effectively.

Moreover, the implications of the study extend beyond clinical practice to research endeavours in oncology. By elucidating the various system tools, questionnaires, and ePRO measurements utilized in cancer patient assessment, the review provides valuable insights into methodological approaches. This knowledge empowers researchers to make informed decisions regarding the selection of appropriate tools tailored to assess specific domains of interest, ultimately contributing to the advancement of knowledge in oncology.

Finally, the findings emphasize the importance of ongoing innovation and refinement in tool development to meet the evolving needs of cancer patients. As the landscape of cancer care continues to evolve, there is a need for continuous improvement and adaptation of ePROMs to ensure their relevance and effectiveness. This underscores the importance of investing in research and development efforts aimed at enhancing the usability, accuracy, and relevance of ePROMs in oncology care.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our systematic review enhances our understanding of the complex array of system tools, questionnaires, and electronic patient-reported outcome (ePRO) measurements utilized in cancer care. By synthesizing existing literature, we offer valuable insights into the methodologies and technologies shaping oncology research and practice. Moving forward, sustained efforts in tool development, validation, and implementation are crucial for comprehensively assessing and addressing the multifaceted needs of cancer patients, ultimately improving the standard of care and patient outcomes. Our review identifies frequently referenced tools like the EORTC QLQ-C30 and PRO-CTCAE, alongside less commonly utilized instruments, providing a comprehensive overview of available assessment tools. By utilizing a variety of instruments that capture different dimensions of patients’ experiences, clinicians and researchers can enhance their understanding of cancer patients’ quality of life, symptom burden, psychological well-being, and treatment satisfaction. Future research should focus on validating and refining existing instruments while also developing new tools to meet the evolving needs of cancer patients across diverse settings and populations.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

HS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SN: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MAl: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. MAh: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank Iran University of Medical Sciences for supporting this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Meirte J, Hellemans N, Anthonissen M, Denteneer L, Maertens K, Moortgat P, et al. Benefits and disadvantages of electronic patient-reported outcome measures: systematic review. JMIR Perioper Med. (2020) 3(1):e15588. doi: 10.2196/15588

2. Di Maio M, Basch E, Denis F, Fallowfield LJ, Ganz PA, Howell D, et al. The role of patient-reported outcome measures in the continuum of cancer clinical care: ESMO clinical practice guideline⋆. Ann Oncol. (2022) 33(9):878–92. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2022.04.007

3. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Devices and Radiological Health. Guidance for industry: patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims: draft guidance. Health Qual Life Outcomes. (2006) 4(1):79. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-79

4. Basch E, Stover AM, Schrag D, Chung A, Jansen J, Henson S, et al. Clinical utility and user perceptions of a digital system for electronic patient-reported symptom monitoring during routine cancer care: findings from the PRO-TECT trial. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. (2020) 4:947–57. doi: 10.1200/CCI.20.00081

5. Valsecchi AA, Battista V, Terzolo S, Dionisio R, Lacidogna G, Marino D, et al. Adoption of electronic patient-reported outcomes in cancer clinical practice: the point of view of Italian patients. ESMO Real World Data Digit Oncol. (2024) 3:100025. doi: 10.1016/j.esmorw.2024.100025

6. Valsangkar N, Fernandez F, Khullar O. Patient reported outcomes: integration into clinical practices. J Thorac Dis. (2020) 12(11):6940–6. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2020.03.91

7. Elkefi S, Asan O. The impact of patient-centered care on cancer patients’ QOC, self-efficacy, and trust towards doctors: analysis of a national survey. J Patient Exp. (2023) 10:23743735231151533.36698621

8. Krzyszczyk P, Acevedo A, Davidoff EJ, Timmins LM, Marrero-Berrios I, Patel M, et al. The growing role of precision and personalized medicine for cancer treatment. Technology (Singap World Sci). (2018) 6(3-4):79–100.30713991

9. Payne A, Horne A, Bayman N, Blackhall F, Bostock L, Chan C, et al. Patient and clinician-reported experiences of using electronic patient reported outcome measures (ePROMs) as part of routine cancer care. J Patient Rep Outcomes. (2023) 7(1):42. doi: 10.1186/s41687-023-00544-4

10. Bennett AV, Jensen RE, Basch E. Electronic patient-reported outcome systems in oncology clinical practice. CA Cancer J Clin. (2012) 62(5):336–47. doi: 10.3322/caac.21150

11. Warnecke E, Salvador Comino MR, Kocol D, Hosters B, Wiesweg M, Bauer S, et al. Electronic patient-reported outcome measures (ePROMs) improve the assessment of underrated physical and psychological symptom burden among oncological inpatients. Cancers (Basel). (2023) 15(11):3029. doi: 10.3390/cancers15113029

12. Hughes J, Flood T. Patients’ experiences of engaging with electronic patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) after the completion of radiation therapy for breast cancer: a pilot service evaluation. J Med Radiat Sci. (2023) 70(4):424–35. doi: 10.1002/jmrs.711

13. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (Clinical Research ed). (2021) 372:n71.33782057

14. Riedl D, Lehmann J, Rothmund M, Dejaco D, Grote V, Fischer MJ, et al. Usability of electronic patient-reported outcome measures for older patients with cancer: secondary analysis of data from an observational single center study. J Med Internet Res. (2023) 25:e49476. doi: 10.2196/49476

15. Graf J, Sickenberger N, Brusniak K, Matthies LM, Deutsch TM, Simoes E, et al. Implementation of an electronic patient-reported outcome app for health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients: evaluation and acceptability analysis in a two-center prospective trial. J Med Internet Res. (2022) 24(2):e16128. doi: 10.2196/16128

16. Riis CL, Stie M, Bechmann T, Jensen PT, Coulter A, Möller S, et al. ePRO-based individual follow-up care for women treated for early breast cancer: impact on service use and workflows. J Cancer Surviv. (2021) 15(4):485–96. doi: 10.1007/s11764-020-00942-3

17. Riis CL, Jensen PT, Bechmann T, Möller S, Coulter A, Steffensen KD. Satisfaction with care and adherence to treatment when using patient reported outcomes to individualize follow-up care for women with early breast cancer—a pilot randomized controlled trial. Acta Oncol (Madr). (2020) 59(4):444–52. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2020.1717604

18. Kikawa Y, Hatachi Y, Rumpold G, Tokiwa M, Takebe S, Ogata T, et al. Evaluation of health-related quality of life via the computer-based health evaluation system (CHES) for Japanese metastatic breast cancer patients: a single-center pilot study. Breast Cancer. (2019) 26(2):255–9. doi: 10.1007/s12282-018-0905-1

19. Hartkopf AD, Graf J, Simoes E, Keilmann L, Sickenberger N, Gass P, et al. Electronic-based patient-reported outcomes: willingness, needs, and barriers in adjuvant and metastatic breast cancer patients. JMIR Cancer. (2017) 3(2):e11. doi: 10.2196/cancer.6996

20. Graf J, Simoes E, Wißlicen K, Rava L, Walter CB, Hartkopf A, et al. Willingness of patients with breast cancer in the adjuvant and metastatic setting to use electronic surveys (ePRO) depends on sociodemographic factors, health-related quality of life, disease status and computer skills. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. (2016) 76(5):535–41. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-105872

21. Wintner LM, Giesinger JM, Zabernigg A, Rumpold G, Sztankay M, Oberguggenberger AS, et al. Evaluation of electronic patient-reported outcome assessment with cancer patients in the hospital and at home. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. (2015) 15:110. doi: 10.1186/s12911-015-0230-y

22. Wintner LM, Giesinger JM, Zabernigg A, Sztankay M, Meraner V, Pall G, et al. Quality of life during chemotherapy in lung cancer patients: results across different treatment lines. Br J Cancer. (2013) 109(9):2301–8. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.585

23. Schougaard LM, Larsen LP, Jessen A, Sidenius P, Dorflinger L, de Thurah A, et al. Ambuflex: tele-patient-reported outcomes (telePRO) as the basis for follow-up in chronic and malignant diseases. Qual Life Res. (2016) 25(3):525–34. doi: 10.1007/s11136-015-1207-0

24. Mayrbäurl B, Giesinger JM, Burgstaller S, Piringer G, Holzner B, Thaler J. Quality of life across chemotherapy lines in patients with advanced colorectal cancer: a prospective single-center observational study. Support Care Cancer. (2016) 24(2):667–74. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2828-0

25. Holch P, Absolom KL, Henry AM, Walker K, Gibson A, Hudson E, et al. Online symptom monitoring during pelvic radiation therapy: randomized pilot trial of the eRAPID intervention. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol. (2023) 115(3):664–76.

26. Nordhausen T, Lampe K, Vordermark D, Holzner B, Al-Ali HK, Meyer G, et al. An implementation study of electronic assessment of patient-reported outcomes in inpatient radiation oncology. J Patient Rep Outcomes. (2022) 6(1):77. doi: 10.1186/s41687-022-00478-3

27. Hofer S, Hentschel L, Richter S, Blum V, Kramer M, Kasper B, et al. Electronic patient reported outcome (ePRO) measures in patients with soft tissue sarcoma (STS) receiving palliative treatment. Cancers (Basel). (2023) 15(4):1233. doi: 10.3390/cancers15041233

28. Zabernigg A, Giesinger JM, Pall G, Gamper EM, Gattringer K, Wintner LM, et al. Quality of life across chemotherapy lines in patients with cancers of the pancreas and biliary tract. BMC Cancer. (2012) 12:390. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-390

29. Cowan RA, Suidan RS, Andikyan V, Rezk YA, Einstein MH, Chang K, et al. Electronic patient-reported outcomes from home in patients recovering from major gynecologic cancer surgery: a prospective study measuring symptoms and health-related quality of life. Gynecol Oncol. (2016) 143(2):362–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.08.335

30. McMullan C, Hughes SE, Aiyegbusi OL, Calvert M. Usability testing of an electronic patient-reported outcome system linked to an electronic chemotherapy prescribing and patient management system for patients with cancer. Heliyon. (2023) 9(6):e16453. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e16453

31. Macanovic B, O'Reilly D, Harvey H, Hadi D, Cloherty M, O'Dea P, et al. A pilot project investigating the use of ONCOpatient®-an electronic patient-reported outcomes app for oncology patients. Digit Health. (2023) 9:20552076231185428. doi: 10.1177/20552076231185428

32. Rocque GB, Dent DAN, Ingram SA, Caston NE, Thigpen HB, Lalor FR, et al. Adaptation of remote symptom monitoring using electronic patient-reported outcomes for implementation in real-world settings. JCO Oncol Pract. (2022) 18(12):e1943–e52. doi: 10.1200/OP.22.00360

33. Patt D, Wilfong L, Hudson KE, Patel A, Books H, Pearson B, et al. Implementation of electronic patient-reported outcomes for symptom monitoring in a large multisite community oncology practice: dancing the Texas two-step through a pandemic. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. (2021) 5:615–21. doi: 10.1200/CCI.21.00063

34. Lapen K, Sabol C, Tin AL, Lynch K, Kassa A, Mabli X, et al. Development and pilot implementation of a remote monitoring system for acute toxicity using electronic patient-reported outcomes for patients undergoing radiation therapy for breast cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. (2021) 111(4):979–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2021.07.1692

35. Dickson NR, Beauchamp KD, Perry TS, Roush A, Goldschmidt D, Edwards ML, et al. Real-world use and clinical impact of an electronic patient-reported outcome tool in patients with solid tumors treated with immuno-oncology therapy. J Patient Rep Outcomes. (2024) 8(1):23. doi: 10.1186/s41687-024-00700-4

36. Moradian S, Ghasemi S, Boutorabi B, Sharifian Z, Dastjerdi F, Buick C, et al. Development of an eHealth tool for capturing and analyzing the immune-related adverse events (irAEs) in cancer treatment. Cancer Inform. (2023) 22:11769351231178587. doi: 10.1177/11769351231178587

37. Iivanainen S, Alanko T, Peltola K, Konkola T, Ekström J, Virtanen H, et al. ePROs in the follow-up of cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a retrospective study. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. (2019) 145(3):765–74. doi: 10.1007/s00432-018-02835-6

38. Helissey C, Parnot C, Rivière C, Duverger C, Schernberg A, Becherirat S, et al. Effectiveness of electronic patient reporting outcomes, by a digital telemonitoring platform, for prostate cancer care: the protecty study. Front Digit Health. (2023) 5:1104700. doi: 10.3389/fdgth.2023.1104700

39. Niska JR, Halyard MY, Tan AD, Atherton PJ, Patel SH, Sloan JA. Electronic patient-reported outcomes and toxicities during radiotherapy for head-and-neck cancer. Qual Life Res. (2017) 26(7):1721–31. doi: 10.1007/s11136-017-1528-2

40. Peltola MK, Lehikoinen JS, Sippola LT, Saarilahti K, Mäkitie AA. A novel digital patient-reported outcome platform for head and neck oncology patients-A pilot study. Clin Med Insights Ear Nose Throat. (2016) 9:1–6. doi: 10.4137/CMENT.S40219

41. Tolstrup LK, Bastholt L, Dieperink KB, Möller S, Zwisler AD, Pappot H. The use of patient-reported outcomes to detect adverse events in metastatic melanoma patients receiving immunotherapy: a randomized controlled pilot trial. J Patient Rep Outcomes. (2020) 4(1):88. doi: 10.1186/s41687-020-00255-0

42. Stormoen DR, Baeksted C, Taarnhøj GA, Johansen C, Pappot H. Patient reported outcomes interfering with daily activities in prostate cancer patients receiving antineoplastic treatment. Acta Oncol (Madr). (2021) 60(4):419–25. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2021.1881818

43. Gvozdanovic A, Jozsa F, Fersht N, Grover PJ, Kirby G, Kitchen N, et al. Integration of a personalised mobile health (mHealth) application into the care of patients with brain tumours: proof-of-concept study (IDEAL stage 1). BMJ Surg Interv Health Technol. (2022) 4(1):e000130.36579146

44. Zhang Y, Li Z, Pang Y, He Y, He S, Su Z, et al. Changes in patient-reported health Status in advanced cancer patients from a symptom management clinic: a longitudinal study conducted in China. J Oncol. (2022) 2022:7531545.36157227

45. Tang L, He Y, Pang Y, Su Z, Li J, Zhang Y, et al. Implementing symptom management follow-up using an electronic patient-reported outcome platform in outpatients with advanced cancer: longitudinal single-center prospective study. JMIR Form Res. (2022) 6(5):e21458. doi: 10.2196/21458

46. Convill J, Blackhall F, Yorke J, Faivre-Finn C, Gomes F. The role of electronic patient-reported outcome measures in assessing smoking Status and cessation for patients with lung cancer. Oncol Ther. (2022) 10(2):481–91. doi: 10.1007/s40487-022-00210-7

47. Williams LA, Whisenant MS, Mendoza TR, Peek AE, Malveaux D, Griffin DK, et al. Measuring symptom burden in patients with cancer during a pandemic: the MD anderson symptom inventory for COVID-19 (MDASI-COVID). J Patient Rep Outcomes. (2023) 7(1):48. doi: 10.1186/s41687-023-00591-x

48. Geese F, Kaufmann S, Sivanathan M, Sairanen K, Klenke F, Krieg AH, et al. Exploring the potential of electronic patient-reported outcome measures to inform and assess care in sarcoma centers: a longitudinal multicenter pilot study. Cancer Nurs. (2023). doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000001248. [Epub ahead of print].37232529

49. Tolstrup LK, Pappot H, Bastholt L, Möller S, Dieperink KB. Impact of patient-reported outcomes on symptom monitoring during treatment with checkpoint inhibitors: health-related quality of life among melanoma patients in a randomized controlled trial. J Patient Rep Outcomes. (2022) 6(1):8. doi: 10.1186/s41687-022-00414-5

50. Brant JM, Hirschman KB, Keckler SL, Dudley WN, Stricker C. Patient and provider use of electronic care plans generated from patient-reported outcomes. Oncol Nurs Forum. (2019) 46(6):715–26. doi: 10.1188/19.ONF.715-726

51. Girgis A, Bamgboje-Ayodele A, Rincones O, Vinod SK, Avery S, Descallar J, et al. Stepping into the real world: a mixed-methods evaluation of the implementation of electronic patient reported outcomes in routine lung cancer care. J Patient Rep Outcomes. (2022) 6(1):70. doi: 10.1186/s41687-022-00475-6

52. Ayodele A, Avery S, Pearson J, Mak M, Smith K, Rincones O, et al. Adapting an integrated care pathway for implementing electronic patient reported outcomes assessment in routine oncology care: lessons learned from a case study. J Eval Clin Pract. (2022) 28(6):1072–83.35470525

53. Girgis A, Durcinoska I, Arnold A, Descallar J, Kaadan N, Koh E-S, et al. Web-based patient-reported outcome measures for personalized treatment and care (PROMPT-care): multicenter pragmatic nonrandomized trial. J Med Internet Res. (2020) 22(10):e19685. doi: 10.2196/19685

54. Harper A, Maseja N, Parkinson R, Pakseresht M, McKillop S, Henning JW, et al. Symptom severity and trajectories among adolescent and young adult patients with cancer. JNCI Cancer Spectr. (2023) 7(6):pkad049. doi: 10.1093/jncics/pkad049

55. Howell D, Rosberger Z, Mayer C, Faria R, Hamel M, Snider A, et al. Personalized symptom management: a quality improvement collaborative for implementation of patient reported outcomes (PROs) in ‘real-world’ oncology multisite practices. J Patient Rep Outcomes. (2020) 4(1):47. doi: 10.1186/s41687-020-00212-x

56. Licht T, Nickels A, Rumpold G, Holzner B, Riedl D. Evaluation by electronic patient-reported outcomes of cancer survivors’ needs and the efficacy of inpatient cancer rehabilitation in different tumor entities. Support Care Cancer. (2021) 29(10):5853–64. doi: 10.1007/s00520-021-06123-x

57. Hlubocky FJ, Daugherty CK, Peppercorn J, Young K, Wroblewski KE, Yamada SD, et al. Utilization of an electronic patient-reported outcome platform to evaluate the psychosocial and quality-of-life experience among a community sample of ovarian cancer survivors. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. (2022) 6:e2200035. doi: 10.1200/CCI.22.00035

58. Abernethy AP, Ahmad A, Zafar SY, Wheeler JL, Reese JB, Lyerly HK. Electronic patient-reported data capture as a foundation of rapid learning cancer care. Med Care. (2010) 48(6):S32–8. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181db53a4

59. Lee J, Jung JH, Kim WW, Kang B, Woo J, Rim H-D, et al. Short-term serial assessment of electronic patient-reported outcome for depression and anxiety in breast cancer. BMC Cancer. (2021) 21(1):1065. doi: 10.1186/s12885-021-08771-y

60. Smith SK, Rowe K, Abernethy AP. Use of an electronic patient-reported outcome measurement system to improve distress management in oncology. Palliat Support Care. (2014) 12(1):69–73. doi: 10.1017/S1478951513000345

61. Ravn S, Thaysen HV, Verwaal VJ, Seibæk L, Iversen LH. Cancer follow-up supported by patient-reported outcomes in patients undergoing intended curative complex surgery for advanced cancer. J Patient Rep Outcomes. (2021) 5(1):120. doi: 10.1186/s41687-021-00391-1

62. Judge MKM, Luedke R, Dyal BW, Ezenwa MO, Wilkie DJ. Clinical efficacy and implementation issues of an electronic pain reporting device among outpatients with cancer. Support Care Cancer. (2021) 29(9):5227–35. doi: 10.1007/s00520-021-06075-2

63. Riedl D, Licht T, Nickels A, Rothmund M, Rumpold G, Holzner B, et al. Large improvements in health-related quality of life and physical fitness during multidisciplinary inpatient rehabilitation for pediatric cancer survivors. Cancers (Basel). (2022) 14(19):4855. doi: 10.3390/cancers14194855

64. Sprave T, Pfaffenlehner M, Stoian R, Christofi E, Rühle A, Zöller D, et al. App-controlled treatment monitoring and support for patients with head and neck cancer undergoing radiotherapy: results from a prospective randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. (2023) 25:e46189. doi: 10.2196/46189

65. Schepers SA, Sint Nicolaas SM, Haverman L, Wensing M, van Meeteren AYN S, Veening MA, et al. Real-world implementation of electronic patient-reported outcomes in outpatient pediatric cancer care. Psychooncology. (2017) 26(7):951–9. doi: 10.1002/pon.4242

66. Pollom EL, Wang E, Bui TT, Ognibene G, von Eyben R, Divi V, et al. A prospective study of electronic quality of life assessment using tablet devices during and after treatment of head and neck cancers. Oral Oncol. (2015) 51(12):1132–7. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2015.10.003

67. Tran C, Dicker A, Leiby B, Gressen E, Williams N, Jim H. Utilizing digital health to collect electronic patient-reported outcomes in prostate cancer: single-arm pilot trial. J Med Internet Res. (2020) 22(3):e12689. doi: 10.2196/12689

68. Lee M, Kang D, Kim S, Lim J, Yoon J, Kim Y, et al. Who is more likely to adopt and comply with the electronic patient-reported outcome measure (ePROM) mobile application? A real-world study with cancer patients undergoing active treatment. Support Care Cancer. (2022) 30(1):659–68. doi: 10.1007/s00520-021-06473-6

69. Wagner LI, Schink J, Bass M, Patel S, Diaz MV, Rothrock N, et al. Bringing PROMIS to practice: brief and precise symptom screening in ambulatory cancer care. Cancer. (2015) 121(6):927–34. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29104

70. Patt DA, Patel AM, Bhardwaj A, Hudson KE, Christman A, Amondikar N, et al. Impact of remote symptom monitoring with electronic patient-reported outcomes on hospitalization, survival, and cost in community oncology practice: the Texas two-step study. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. (2023) 7:e2300182. doi: 10.1200/CCI.23.00182

71. Gressel GM, Dioun SM, Richley M, Lounsbury DW, Rapkin BD, Isani S, et al. Utilizing the patient reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS®) to increase referral to ancillary support services for severely symptomatic patients with gynecologic cancer. Gynecol Oncol. (2019) 152(3):509–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2018.10.042

72. Oldenburger E, Isebaert S, Coolbrandt A, Van Audenhove C, Haustermans K. The use of electronic patient reported outcomes in follow-up after palliative radiotherapy: a survey study in Belgium. PEC Innovation. (2023) 3:100243. doi: 10.1016/j.pecinn.2023.100243

73. Mohseni M, Ayatollahi H, Arefpour AM. Electronic patient-reported outcome (ePRO) application for patients with prostate cancer. PLoS One. (2023) 18(8):e0289974. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0289974

74. Zhang L, Zhang X, Shen L, Zhu D, Ma S, Cong L. Efficiency of electronic health record assessment of patient-reported outcomes after cancer immunotherapy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. (2022) 5(3):e224427. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.4427

75. Wickline M, Wolpin S, Cho S, Tomashek H, Louca T, Frisk T, et al. Usability and acceptability of the electronic self-assessment and care (eSAC) program in advanced ovarian cancer: a mixed methods study. Gynecol Oncol. (2022) 167(2):239–46.36150917

76. Daly B, Nicholas K, Flynn J, Silva N, Panageas K, Mao JJ, et al. Analysis of a remote monitoring program for symptoms among adults with cancer receiving antineoplastic therapy. JAMA Netw Open. (2022) 5(3):e221078. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.1078

77. Boeke S, Hauth F, Fischer SG, Lautenbacher H, Bizu V, Zips D, et al. Acceptance of physical activity monitoring in cancer patients during radiotherapy, the GIROfit phase 2 pilot trial. Tech Innov Patient Support Radiat Oncol. (2022) 22:16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.tipsro.2022.03.004

78. Takala L, Kuusinen T-E, Skyttä T, Kellokumpu-Lehtinen P-L, Bärlund M. Electronic patient-reported outcomes during breast cancer adjuvant radiotherapy. Clin Breast Cancer. (2021) 21(3):e252–e70. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2020.10.004

79. Strachna O, Cohen MA, Allison MM, Pfister DG, Lee NY, Wong RJ, et al. Case study of the integration of electronic patient-reported outcomes as standard of care in a head and neck oncology practice: obstacles and opportunities. Cancer. (2021) 127(3):359–71. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33272

80. Peltola MK, Poikonen-Saksela P, Mattson J, Parkkari T. A novel digital patient-reported outcome platform (noona) for clinical use in patients with cancer: pilot study assessing suitability. JMIR Form Res. (2021) 5(5):e16156. doi: 10.2196/16156

81. Generalova O, Roy M, Hall E, Shah SA, Cunanan K, Fardeen T, et al. Implementation of a cloud-based electronic patient-reported outcome (ePRO) platform in patients with advanced cancer. J Patient Rep Outcomes. (2021) 5(1):91. doi: 10.1186/s41687-021-00358-2

82. Doolin JW, Berry JL, Forbath NS, Tocci NX, Dechen T, Li S, et al. Implementing electronic patient-reported outcomes for patients with new oral chemotherapy prescriptions at an academic site and a community site. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. (2021) 5:631–40. doi: 10.1200/CCI.20.00191

83. Absolom K, Warrington L, Hudson E, Hewison J, Morris C, Holch P, et al. Phase III randomized controlled trial of eRAPID: eHealth intervention during chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. (2021) 39(7):734–47. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.02015

84. Zylla DM, Gilmore GE, Steele GL, Eklund JP, Wood CM, Stover AM, et al. Collection of electronic patient-reported symptoms in patients with advanced cancer using epic MyChart surveys. Support Care Cancer. (2020) 28(7):3153–63. doi: 10.1007/s00520-019-05109-0

85. Sandhu S, King Z, Wong M, Bissell S, Sperling J, Gray M, et al. Implementation of electronic patient-reported outcomes in routine cancer care at an academic center: identifying opportunities and challenges. JCO Oncol Pract. (2020) 16(11):e1255–e63. doi: 10.1200/OP.20.00357

86. Richards HS, Blazeby JM, Portal A, Harding R, Reed T, Lander T, et al. A real-time electronic symptom monitoring system for patients after discharge following surgery: a pilot study in cancer-related surgery. BMC Cancer. (2020) 20(1):543. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-07027-5

87. Mowlem FD, Sanderson B, Platko JV, Byrom B. Optimizing electronic capture of patient-reported outcome measures in oncology clinical trials: lessons learned from a qualitative study. J Comp Eff Res. (2020) 9(17):1195–204. doi: 10.2217/cer-2020-0143

88. Karamanidou C, Maramis C, Stamatopoulos K, Koutkias V. Development of a ePRO-based palliative care intervention for cancer patients: a participatory design approach. Stud Health Technol Inform. (2020) 270:941–5.32570520

89. Dronkers EAC, Baatenburg de Jong RJ, van der Poel EF, Sewnaik A, Offerman MPJ. Keys to successful implementation of routine symptom monitoring in head and neck oncology with “healthcare monitor” and patients’ perspectives of quality of care. Head Neck. (2020) 42(12):3590–600. doi: 10.1002/hed.26425

90. Biran N, Anthony Kouyaté R, Yucel E, McGovern GE, Schoenthaler AM, Durling OG, et al. Adaptation and evaluation of a symptom-monitoring digital health intervention for patients with relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma: pilot mixed-methods implementation study. JMIR Form Res. (2020) 4(11):e18982. doi: 10.2196/18982

91. Warrington L, Absolom K, Holch P, Gibson A, Clayton B, Velikova G. Online tool for monitoring adverse events in patients with cancer during treatment (eRAPID): field testing in a clinical setting. BMJ Open. (2019) 9(1):e025185. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025185

92. Krogstad H, Sundt-Hansen SM, Hjermstad MJ, Hågensen LÅ, Kaasa S, Loge JH, et al. Usability testing of EirV3—a computer-based tool for patient-reported outcome measures in cancer. Support Care Cancer. (2019) 27(5):1835–44. doi: 10.1007/s00520-018-4435-3

93. Avery KNL, Richards HS, Portal A, Reed T, Harding R, Carter R, et al. Developing a real-time electronic symptom monitoring system for patients after discharge following cancer-related surgery. BMC Cancer. (2019) 19(1):463. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-5657-6

94. Lucas SM, Kim T-K, Ghani KR, Miller DC, Linsell S, Starr J, et al. Establishment of a web-based system for collection of patient-reported outcomes after radical prostatectomy in a statewide quality improvement collaborative. Urology. (2017) 107:96–102. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2017.04.058

95. Holch P, Warrington L, Bamforth LCA, Keding A, Ziegler LE, Absolom K, et al. Development of an integrated electronic platform for patient self-report and management of adverse events during cancer treatment. Ann Oncol. (2017) 28(9):2305–11. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx317

96. Absolom K, Holch P, Warrington L, Samy F, Hulme C, Hewison J, et al. Electronic patient self-reporting of adverse-events: patient information and aDvice (eRAPID): a randomised controlled trial in systemic cancer treatment. BMC Cancer. (2017) 17(1):318. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3303-8

97. Duregger K, Hayn D, Nitzlnader M, Kropf M, Falgenhauer M, Ladenstein R, et al. Electronic patient reported outcomes in paediatric oncology—applying Mobile and near field communication technology. Stud Health Technol Inform. (2016) 223:281–8.27139415

Appendix

Keywords: electronic patient-reported outcome measures, ePROMs, cancer care, measurement instruments, patient assessment

Citation: Salmani H, Nasiri S, Alemrajabi M and Ahmadi M (2024) Advancing patient-centered cancer care: a systematic review of electronic patient-reported outcome measures. Front. Rehabil. Sci. 5:1427712. doi: 10.3389/fresc.2024.1427712

Received: 8 May 2024; Accepted: 12 September 2024;

Published: 25 September 2024.

Edited by:

Saeid Shahraz, Tufts Medical Center, United StatesReviewed by:

Annemarie L. Lee, Monash University, AustraliaSuleman Atique, Norwegian University of Life Sciences, Norway

Copyright: © 2024 Salmani, Nasiri, Alemrajabi and Ahmadi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Maryam Ahmadi, YWhtYWRpLm1AaXVtcy5hYy5pcg==

Hosna Salmani

Hosna Salmani Somayeh Nasiri1

Somayeh Nasiri1