- 1Program in Occupational Therapy, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO, United States

- 2Department of Neurology, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO, United States

- 3Department of Psychiatry, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO, United States

Background: Although goal setting and goal management (GSGM) is a key component of chronic disease management and rehabilitation practice, there is currently no widely used evidence-based intervention system available. This paper describes the theoretical underpinnings and development of a new intervention called MyGoals. MyGoals is designed to guide occupational therapy (OT) practitioners to implement theory-based, client-engaged GSGM for adults with chronic conditions in community-based OT rehabilitation settings.

Methods: We first developed a planning team with two adults with chronic conditions, two clinicians, and two researchers. As a collaborative team, we co-developed MyGoals by following Intervention Mapping (IM) steps 1–4 and incorporating community-based participatory research principles to ensure equitable, ecologically valid, and effective intervention development. In the first step, the planning team conducted a discussion-based needs assessment and a systematic review of current GSGM practice to develop a logic model of the problem. In the second step, the planning team identified performance objectives, intervention target personal determinants, and change objectives, and created a logic model of change and matrics of change objectives. In the third step, the planning team designed MyGoals. Lastly, in the fourth step, the planning team produced, pilot-tested, and refined MyGoals.

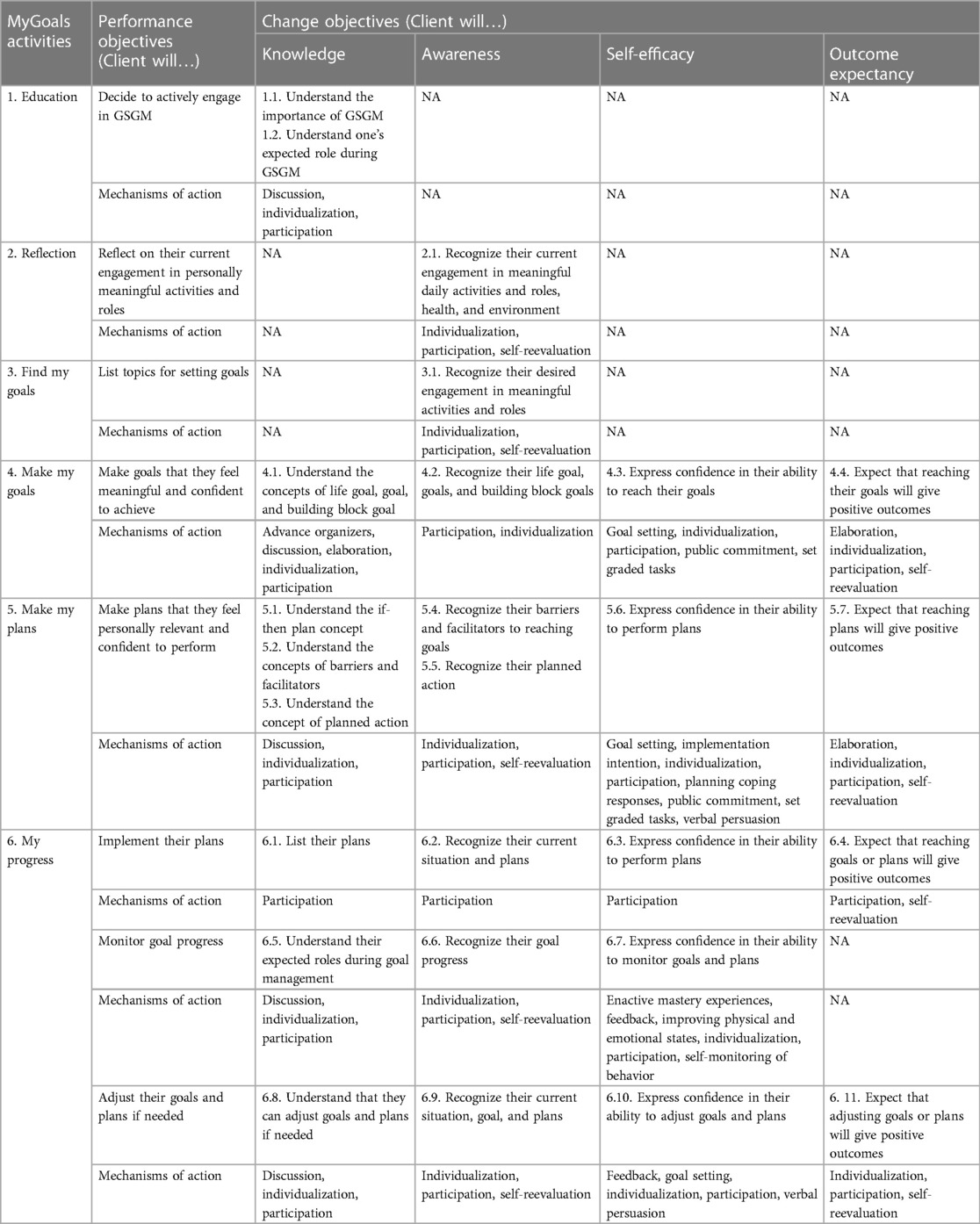

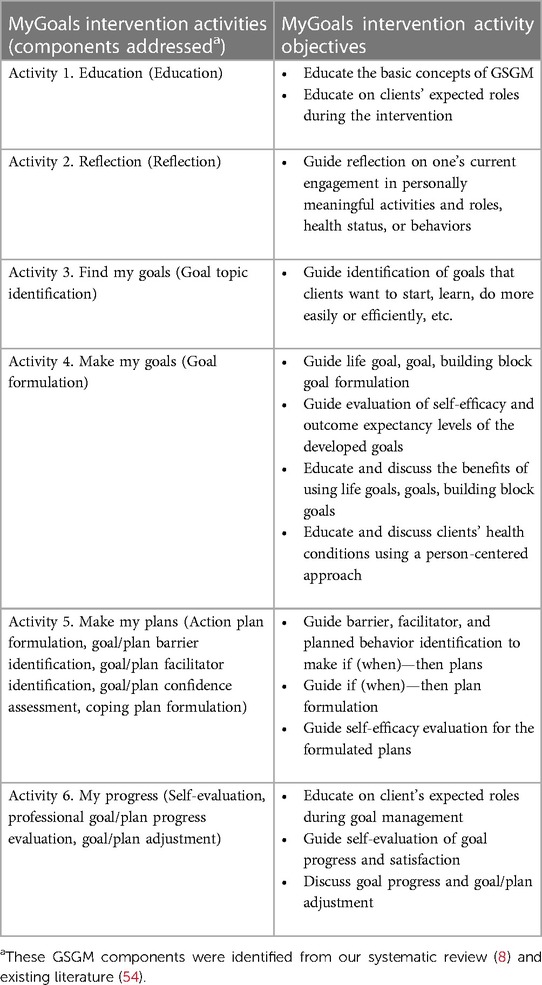

Results: The ultimate goal of the MyGoals intervention is to enable clients to achieve personally meaningful rehabilitation goals. The planning team identified four target determinants (e.g., self-efficacy), six intervention activities (e.g., Education, Reflection, Find My Goals, Make My Goals, Make My Plans, My Progress), eight performance objectives (e.g., List potential goals), and 26 change objectives (e.g., Understand the importance of GSGM). Two pilot tests indicated that MyGoals is feasible for clients and identified areas for improvement. Based on the feedback, minor refinements were made to the MyGoals intervention materials.

Conclusions: We completed rigorous and collaborative IM to develop MyGoals. Establishing the theoretical and developmental foundation for MyGoals sets the groundwork for high-quality, evidence-based GSGM. Future studies on effectiveness and implementation are necessary to refine, translate, and scale MyGoals in rehabilitation practice.

Introduction

Goal setting and goal management (GSGM) is a fundamental rehabilitation practice in which clients and clinicians collaboratively establish goals, develop plans, evaluate goal progress and achievement, and adjust goals and plans (1–4). The goal setting process includes evaluating clients’ values, assessing current and desired functioning, setting goals, and making plans. Meanwhile, the goal management process involves evaluating goal progress and achievement, as well as adjusting goals and plans as needed. Throughout GSGM, clients and clinicians develop an understanding of client-related factors (e.g., clients’ needs, health conditions, and environment), enhance their working relationship, and make shared goals and plans (2, 5–7). The established goals and plans provide clients and clinicians with a mutual direction for treatment, and thus can promote person-centered rehabilitation implementation (5).

While there are several frameworks and approaches that emphasize a person-centered, collaborative approach, such as SMART rehabilitation goals and MEANING, current GSGM in rehabilitation practice remains suboptimal, primarily due to two major practice gaps (8–13). These include limited implementation of theory-based intervention components and poor client engagement in the intervention (8). Most interventions do not fully incorporate all essential theory-based GSGM components (8). Components related to coping planning, goal monitoring, goal evaluation, and goal adjustment are particularly under-utilized in current practice even though they are likely as important as other frequently used components such as goal formulation (8).

Achieving active client engagement in GSGM is another major challenge in practice (8, 14, 15). Active client engagement in GSGM may promote better outcomes such as a better sense of ownership of rehabilitation care, quality of life, self-reported emotional status, and self-efficacy (5, 16). However, current practice does not facilitate active client engagement (8). Clinicians often fail to enable clients to participate actively in GSGM (17, 18). This is not because clinicians do not have the knowledge, but rather because they have difficulty translating their knowledge into practice (17). We need a new practical and effective system to address these research-practice gaps by guiding clinicians to implement high-quality GSGM (8, 18–20).

Developing evidence-based interventions requires a systematic approach that includes a review of literature and theories, collaboration with community partners such as clients and practitioners, implementation strategy development, and intervention adaptation and evaluation (21). In rehabilitation, especially in occupational therapy (OT), there have been challenges in establishing ecologically valid evidence-based interventions. This is due to inadequate identification and description of intervention components and mechanisms, as well as insufficient consideration of the preferences and needs of target clients and practitioners (22–25).

To address these limitations, the use of a theory-based, collaborative approach such as Intervention Mapping (IM) and community-based participatory research principles is actively advocated for the development of interventions (21, 24–27). A growing number of studies have began to utilize IM with community-based participatory research in developing interventions across various fields and contexts (28–30). However, despite their potential, there are few GSGM interventions that utilize these approaches in their development. To address this gap, we developed a new system to guide theory-based, client-engaged GSGM, called MyGoals. MyGoals is designed to support practitioners to implement comprehensive, client-engaging GSGM for adults with chronic conditions in community-based rehabilitation using six intervention activities.

In this paper, we describe the developmental process and detail the theoretical background of MyGoals using IM in collaboration with two adults with chronic conditions, two clinicians, and the research team (21, 27). We elaborate on MyGoals’ logic model of the problem, logic model of change, matrix of change, mechanisms of action, intervention targets, active ingredients, production, and refinement. In its current initial developmental stage, MyGoals is designed primarily for implementation in an OT context. However, the long-term goal of this development is to translate this new intervention into broader rehabilitation practice, with additional work to ensure its clinical utility and generalizability.

Materials and methods

MyGoals Intervention Mapping (IM) conceptual model

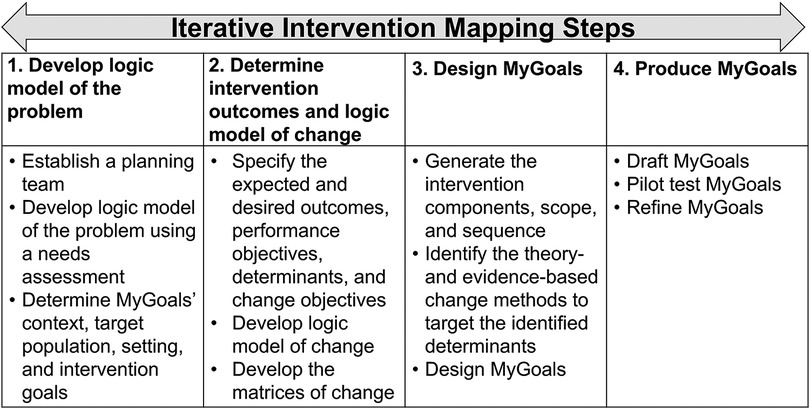

IM is a set of six iterative tasks to guide the identification of behavior determinants, mechanisms of action, intervention strategies, active intervention ingredients, and outcomes to develop theory-based interventions (21). IM includes the following tasks: (1) Developing a logic model of the problem to identify the target health problems and understand the behavioral and environmental factors, as well as personal determinants (e.g., self-efficacy, knowledge), that lead to the identified health problem, (2) Creating a logic model of change to determine the desired health outcomes and describe which behavioral and environmental factors and personal determinants need to be addressed to achieve these outcomes, (3) Designing the intervention, which includes determining its dose, components, delivery methods, materials, and other aspects, (4) Producing the intervention, (5) Planning intervention implementation by developing strategies to deliver the intervention, and (6) Evaluating the intervention based on the logic model of change (21). Theories, models, and frameworks play central roles across IM steps to develop theory-based interventions. Each IM step provides a guide on how to use theories, models, and frameworks to determine intervention target behaviors, goals, components, approaches, mechanisms of action, and others. The working conceptual model of MyGoals IM is illustrated in Figure 1 and detailed in the below paragraphs. The findings from IM steps 5 and 6 are published elsewhere (31–33).

IM step 1. Logic model of the problem

The first step involves establishing a planning team and developing a logic model of the problem (21). The planning team was developed, including two adults with chronic conditions (MyGoals target clients), two clinicians, and the research team. Although the size of the planning team is not particularly large, we chose the current size to gain in-depth perspectives from each individual member. Furthermore, since we planned to incorporate extensive literature and theories, this team size was deemed appropriate, especially when considering logistical limitations. For instance, a larger team size would require more time commitment from members to accommodate all perspectives.

Given the small number of planning team members, we decided not to report detailed demographic information to avoid the potential identification of any individual. The median age of two client participants was 73.5 years old (SD = 10.6), and they were male and female. All planning team members self-identified as non-Hispanic or Latino and either Asian, Black or African American, or White. Every member had at least a high school degree. The diagnoses among client members included Parkinson's disease, cancer, and diabetes. Clinicians were OT practitioners employed in community-based practice settings. The median years of professional working experience for the clinicians was 10 (SD = 4.2). We completed a discussion-based needs assessment and a systematic review of current GSGM practice to identify health problems, determinants, behavior problems, and essential GSGM intervention components (8). Based on these findings, the team developed the logic model of the problem and clarification of MyGoals intervention context, target population, setting, and intervention goals.

IM step 2. Logic model of change

The second step involves developing the logic model of change with the expected behavior outcomes, performance objectives, personal determinants, and matrices of change objectives by using the IM guided questions (e.g., “What do clients need to do to achieve their personally meaningful goals?”) (21). We drafted performance objectives and compared them with essential GSGM components that we identified from the aforementioned systematic review (8) to determine how these objectives can be incorporated into MyGoals. Then we reviewed the literature, brainstormed potential determinants, and selected key determinants for each performance objective. We also developed change objectives to define desired changes at the personal determinant level. Combining all findings from the second step, we developed the MyGoals Logic Model of Change and the matrices of change objectives.

IM step 3. Intervention theories, approaches, and design

The third step involves generating the intervention components, scope, and sequence, selecting theory- and evidence-based behavior change methods, and designing a practical intervention that satisfies the parameters of effectiveness (21). Based on the findings from the previous steps, we determined the intervention components, scope, and sequence and theory- and evidence-based change methods to target the identified determinants using Social Cognitive Theory (34–37), Self-Determination Theory (38, 39), The Theory Of Intentional Action Control (40–42), and A Taxonomy Of Behaviour Change Methods (43).

IM step 4. Intervention manual, manual, instructions, scripts, supplements

The fourth step involves MyGoals production, evaluation, and refinement (21). We drafted the MyGoals manual, instructions, scripts, supplements, and client worksheets (see example in Supplementary File S1). The materials are designed to provide structure and support and to enable clinicians to implement MyGoals in their practice without significant modifications; however, they are not meant to be prescriptive. Rather, MyGoals is designed with flexibility in its delivery (e.g., time allocated for each activity, streamlining of activities) depending on practice setting, clients, etc.

Two rounds of in-person MyGoals pilot evaluations were completed with the planning team members. The OT-client planning team dyad completed two in-person sessions (1st session: complete MyGoals activity 1. Education—5. Make My Plan and 2nd session: Complete MyGoals activity 6. My Progress). After the pilot evaluation, the planning team discussed and identified areas for improvement, and then revised the developed materials.

Results

IM step 1. Logic model of the problem

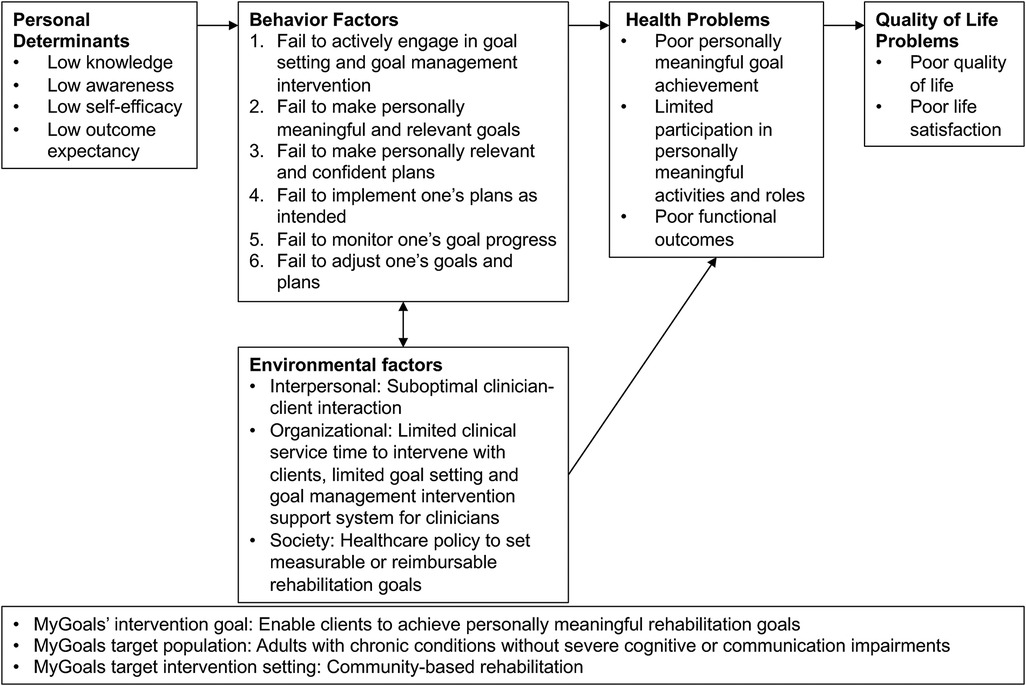

The overall goal of the MyGoals intervention was identified as enabling clients to achieve personally meaningful rehabilitation goals. The target population for MyGoals was adults with chronic conditions who do not have severe cognitive and communication impairments, and the setting was community-based rehabilitation. We specified poor goal achievement as a primary health issue that MyGoals was designed to address, as illustrated in the MyGoals Logic Model of the Problem (Figure 2). Subsequently, we identified specific behavioral and environmental factors, as well as personal determinants, that correlate with poor goal achievement within the target population.

Self-efficacy is a key determinant that has shown positive associations with goal-directed behavior (44, 45). Social Cognitive Theory suggests that people with lower self-efficacy are less likely to actively commit and persist in their goals (36, 37, 46). Outcome expectancy is another important determinant from Social Cognitive Theory that can drive goal-directed behavior (34, 35, 47). People evaluate the potential positive and negative outcomes of their goals and then develop intentions to act or not act on their goals (34, 35, 47). Thus, when people do not have an adequate level of positive outcome expectancy for their goals, they are less likely to take goal-directed behavior (48, 49). Inadequate knowledge of GSGM concepts and expected roles during GSGM can lead to poor engagement in the intervention or limit goal-directed behaviors, which can result in poor goal achievement (50). Lastly, poor awareness about oneself can hinder the development of personally meaningful goals and goal achievement (51–53).

Through our systematic review of the current GSGM literature, we identified 12 essential components of GSGM: education, reflection, goal exploration, goal formulation, action planning formulation, goal/plan barrier identification, goal/plan facilitator identification, goal/plan confidence evaluation, coping planning formulation, evaluation, self-evaluation, and goal/plan adjustment (8). Details about these components are outlined in the Step 3 results below.

IM step 2. Logic model of change

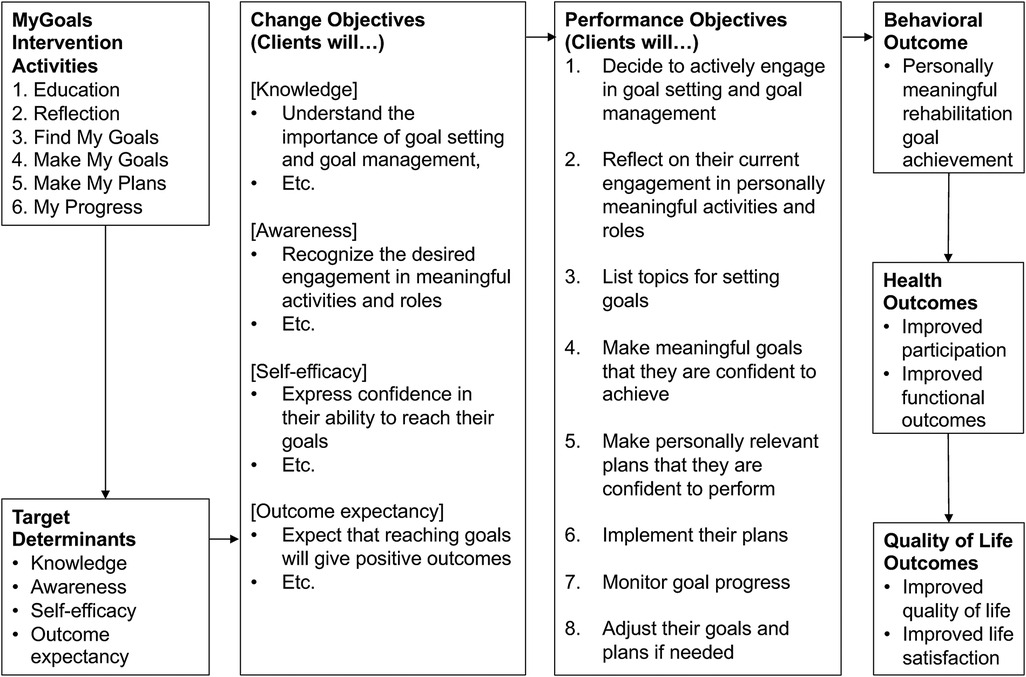

We developed the MyGoals Logic Model of Change (Figure 3) and the matrices of change objectives (Table 1). In Figure 3, we outlined the performance and change objectives necessary for clients to achieve the identified behavioral outcome of MyGoals (i.e., personally meaningful rehabilitation goal achievement). Further details about change and performance objectives, as well as determinants (intervention targets) of MyGoals, are described in Table 1.

For instance, to achieve the performance objective of deciding to actively engage in GSGM, clients should gain knowledge (i.e., determinant). Specifically, they need to achieve two knowledge-related change objectives including understanding the importance of GSGM and understanding one’s expected role during GSGM. By achieving these two change objectives, clients become more likely to achieve the performance objective.

IM step 3. Intervention theories, approaches, and design

To address all 12 identified GSGM components, we developed six MyGoals activities (Table 2). Table 2 describes how each MyGoals activity addresses the GSGM components idenfied in step 1 and its corresponding objectives. After completing step 3, we iteratively refined the matrics of change objectives by using the six MyGoals activities as outlined in Table 1.

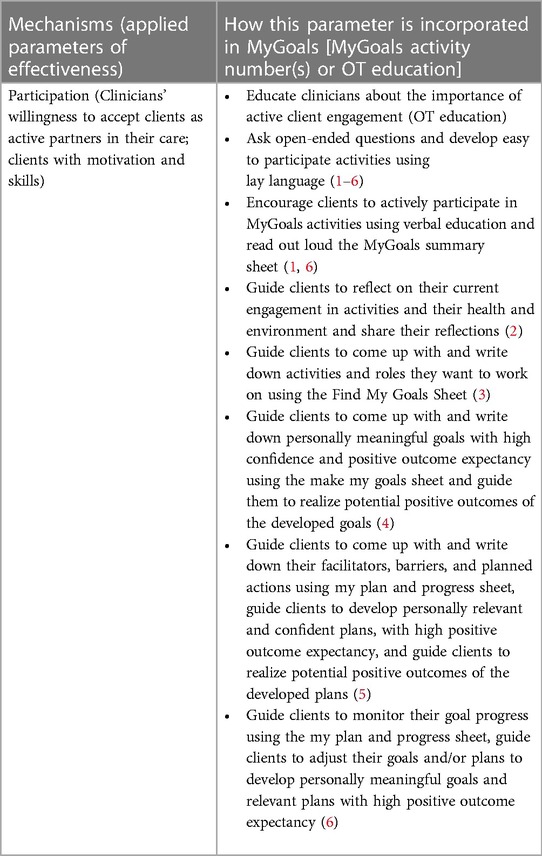

We identified theory- and evidence-based change methods to target the identified determinants using Social Cognitive Theory (34–37), Self-Determination Theory (38, 39), the theory of intentional action control (40–42), and the taxonomy of behaviour change methods as described in Supplementary File S2 (43). We further took into consideration the parameters for effectiveness based on Kok et al. (43) to activate the identified mechanisms of action in MyGoals as described in Table 3 and Supplementary File S2. For instance, as described in Table 3, participation (in the intervention) is known as an effective mechanism of action when clients want to and have the ability to participate in interventions and clinicians are willing to collaborate with clients as co-partners (43). Therefore, MyGoals provides clinicians with the educational resources to understand the importance of active client engagement and encourages them to foster a more open client-clinician partnership during interventions. MyGoals also incorporates various intervention strategies, such as open-ended questions, into the manual to support clinicians in promoting active client engagement. Additional details about this and other examples of mechanisms of action and parameters in MyGoals are provided in Table 3 and Supplementary File S2.

IM step 4. Intervention manual, manual, instructions, scripts, supplements

We drafted the MyGoals manual, instructions, scripts, supplements, and client worksheets. Supplementary File S1 includes an example of a MyGoals activity, Activity 4: Make My Goals, and a Case Study is included below to illustrate the entire process. For instance, Activity 4. Make My Goals is designed to enable clinicians to guide clients to first develop participation-based goals that are intrinsicly motivating as suggested by Self-Determination Theory (38, 39). Then clients make goals related to activity, health conditions, and body functions & structures that will support achievement of their participation-related goals. Activity 3. Make My Plans is designed to help clinicians guide clients to identify their goal facilitators and barriers. Identifying barriers and faciltators can help the client improve their awareness about their capacity and available resources to improve their competency as suggested by Self-Determination Theory (38, 39) and self-efficacy to achieve their goals as suggested by Social Cognitive Theory (34–37). Based on the identified factors, clients are guided to develop if-then plans informed by the theory of intentional action control (40–42).

The materials are designed to provide structure and support and to enable clinicians to implement MyGoals in their practice without significant modifications; however, they are not meant to be prescriptive. Rather, MyGoals is designed with flexibility in its delivery (e.g., time allocated for each activity, streamlining of activities) depending on practice setting, clients, etc.

After the pilot evaluation, we found that most parts of MyGoals seemed feasible from both clients’ and clinicians’ perspectives. We made several minor revisions based on our pilot testing. We added detailed explanations about different goal types to facilitate goal formulation. We also included a written summary of basic GSGM concepts and clients’ expected roles during the intervention. We made minor revisions to the scripts and instructions on the client worksheets to ensure that MyGoals uses lay language to facilitate the interactive client-OT conversation and client engagement throughout the MyGoals intervention.

Case study

We provide a brief case study to illustrate the application of MyGoals.

Kasey is a 55-year-old librarian who had a stroke one year ago, which resulted in mild right upper extremity impairment, mild depressive symptoms, and mild cognitive impairment. After intense inpatient rehabilitation, Kasey made a full recovery in her upper extremity and now lives independently in an apartment with their dog, Bella, and has returned to work. Prior to her stroke, Kasey had a physically and socially active lifestyle and enjoyed weekend hikes with Bella. However, since returning home and to work, Kasey notes moderate fatigue and a decrease in physical activity throughout the day, especially after work. She has stopped taking Bella for walks and meeting up with friends regularly. Kasey has also noticed mild forgetfulness, difficulty managing her daily routine, and difficulty focusing at work. In the past two weeks, Kasey has become concerned about whether she can continue to live independently at home, work, and stay healthy and has experienced increased feelings of depression and anxiety. Due to these concerns, Kasey was referred to a community-based OT for self-management.

• Activity 1. Education: Kasey learned about the importance of goal setting and goal management, as well as the importance of active engagement during the intervention, to make personally meaningful goals and realistic and relevant plans to achieve better participation and health. Kasey mentioned that she tends to feel overwhelmed when she needs to make a sudden decision or when things do not go as planned. Therefore, Kasey prefers to have a clear plan as well as a backup plan to better handle daily life activities.

• Activity 2. Reflection: Kasey reflected on her functions, including cognitive, emotional, and physical functions, as well as her engagement in meaningful activities. She identified exercise, walking her dog, being with friends, work, and reading as meaningful, enjoyable, and important activities. Among these, Kasey wanted to focus on exercise, walking the dog, and work during therapy.

• Activity 3. Find My Goal: Kasey made three potential goals: “exercise for 15 min every day,” “walk my dog,” and “work productively.” Kasey rated their importance as 9’s for the first and 7 for the last two (on a scale of 1–10, with higher scores indicating higher importance). Kasey decided to focus on the following goal for therapy: “walk my dog.”

• Activity 4. Make My Goal: Kasey chose to work on her goal of “walking my dog” because it helps her exercise, take care of Bella, and casually interact with friends and neighbors while walking. Kasey then specified the goal as follows: “I will walk Bella for 30 min every day after my breakfast.” She rated its importance as a 9 and positive outcome expectancy as a 10. Kasey also made a life goal of “having a physically and socially active life” and a building block goal of “better managing my energy and fatigue” to support achieving the goal. Kasey discussed how these goals were interrelated and could support better participation and health.

• Activity 5. Make My Plan: Kasey identified three barriers to achieving her goal of walking Bella every day—feeling tired, forgetting to walk Bella, and concern about neighborhood safety while walking alone. After identifying the barriers, the OT educated Kasey about general fatigue management and energy conservation strategies. Then, the OT and Kasey discussed together which specific strategies would work best for Kasey and how to personalize these for Kasey's preferences, needs, and life situations to make personally relevant and realistic plans. After the education and discussion, to overcome the first and second barriers, Kasey identified a facilitator: walking right after breakfast because it is the most energizing time for her, and because having breakfast is a stable part of her morning routine. To overcome the last barrier, Kasey identified another facilitator: walking in the neighborhood during busy morning hours to ensure many neighbors are around for safety. Kasey made an if(when)-then plan to achieve their goal and rated their confidence in reaching it as 9 out of 10. The plan is as follows: “When I finish my breakfast, then I will walk Bella for 30 min in my neighborhood.”

• Activity 6. My Progresss: The following week, Kasey returned to therapy and discussed with the OT practitioner about what helped and prevented her from carrying out her plan. Kasey said having a specific action plan helps her feel less overwhelmed because she knows what needs to be done and how. At the same time, choosing the time as “after breakfast” instead of an exact time gave Kasey some flexibility in managing her time but also helped ensure she would not forget to take Bella for a walk since it happened every day. Additionally, because Kasey knew that there would be many neighbors out during morning hours, she felt more comfortable walking outside alone. Kasey mentioned that she sometimes feel too tired to walk for 30 min, and when this happens, she tends to give up. Kasey said having backup plan for tired days can be helpful to at least walk a little bit without giving up the routine. Kasey rated her performance and satisfaction with her goal progress both as 9’s and discussed whether she wanted to adjust her goals and plans. Kasey wanted to keep the original plan and added a backup plan for days when she feels extra tired. Thus, Kasey made the following coping plan: “If I feel too tired to walk for 30 min, I will walk Bella as much as I can.” Kasey rated her confidence in reaching this plan as a 9 and continued to work on her goal by using two plans.

Discussion

This paper provides the theoretical foundation, description, and development of a novel system designed to promote comprehensive and client-engaging GSGM. To our knowledge, this is first use of IM in developing GSGM for adults with chronic conditions in community-based rehabilitation. This offers important insights into the theoretical aspects and systematic development of MyGoals. It facilitates a thorough understanding of MyGoals and its implementation. Ultimatley, this work can produce quality evidence across contexts and contribute to the enhancement of high-quality GSGM practice implementation.

Theoretical implications

Rehabilitation interventions often do not specify the theoretical processes that enable clients to achieve the desired intervention outcomes (23). Such practice hinders the understanding, evaluation, and replication of rehabilitation interventions and their mechanisms, and ultimately delays in establishing evidence-based interventions (22, 23). We have provided the theoretical background of MyGoals intervention target constructs, approaches, activities, mechanisms of action, and parameters for effectiveness. We specified why and how MyGoals’ theoretical constructs such as self-efficacy are incorporated into the intervention. We also laid the groundwork to establish theory-based mechanisms of action for MyGoals by developing hypothesized processes by which the intervention enables clients to achieve the change and performance objectives to reach the ultimate intervention goal. This specification provides a rationale for each activity as well as the overall intervention.

MyGoals can be seen as a natural synthesis and advancement of existing GSGM frameworks and approaches. In creating MyGoals, our objective was to develop a concrete, practical intervention system that would support practitioners in translating evidence-based interventions into practice more effectively. Existing frameworks and approaches offer overarching principles on how GSGM should be conducted or focus on specific GSGM intervention components (e.g., goal attainment scaling, which emphasize making and reviewing goals without delving into planning) (4, 10, 13, 55). On the other hand, MyGoals integrates traditional and foundational principles, such as person-centeredness, thorough assessments of clients’ values and functions, and enhancement of client-practitioner collaborations, into a tangible intervention system with a strong emphasis on clinical utility. Leveraging an implementation science framework and a community-engaged approach allowed us to transform the core principles of existing frameworks into a practical, theory-driven GSGM intervention that holistically addresses GSGM components, from education to goal adjustment.

Future studies can evaluate the mechanisms of action to disentangle how each activity works at the determinant-, performance-, or activity levels, not simply how MyGoals works as a whole. This will permit precise optimization of individual activities to improve the intervention's efficacy and effectiveness overall. The information provided in this paper will allow us to build more generalizable knowledge to establish evidence-based GSGM.

Practice implications

MyGoals’ structured approach can support practitioners to easily implement theory-based GSGM components in practice and promote active client engagement during the intervention. In our needs assessment, clinicians expressed difficulties in using the existing GSGM tools in practice due to their lack of a structured approach and practical guidelines. MyGoals’ intervention activities, a detailed manual, clinician scripts, and a client worksheet can address this noted limitation in practice and support high-quality GSGM practice by providing concrete structured materials for practitioners.

We further enhanced the ecological validity of MyGoals by incorporating the perspectives of end-users including practitioners and clients into its development, which may improve its clinical utility. Indeed, we have conducted a feasibility study of MyGoals and found that clinicians consider MyGoals to be a feasible and promising tool to guide theory-based, client-engaging GSGM (33). Future studies will evaluate MyGoals’ effectiveness in supporting GSGM to promote person-centered OT rehabilitation and improve health in adults with chronic conditions. Additional work to validate MyGoals’ feasibility and effectiveness in other rehabilitation contexts is required.

Limitations

The clinician and client team members had limited time to work on this project. Therefore, the research team needed to design the overall research process and prepare all meeting materials such as discussion questions, educational materials, articles, and logic model drafts. However, by promoting interactive discussion, we ensured the active engagement of all team members. In the future, partners should be provided with additional protected time and resources to allow them to take a more active role in the research. However, to do this we need to develop effective strategies to promote community-engaged research given that not all research studies have extensive resources, especially in early developmental stages.

Conclusion

We provide in-depth information on the development of a new system, MyGoals, to support high-quality theory-based GSGM intervention implementation. IM successfully guided us in developing MyGoals through collaboration with clients and clinicians. Our systematic and theory-based intervention development and reporting will help other rehabilitation scientists and clinicians critically examine how our work can inform or be translated into their research and practice. Future studies are planned to evaluate the effectiveness of MyGoal in achieving better rehabilitation outcomes for adults with chronic conditions.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Washington University Institutional Review Board (IRB#: 202106038). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

EK: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding aquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Visualization. EF: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Methodology, Funding aquisition, Resources, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

This work was supported by the Program in Occupational Therapy, Washington University in St. Louis under Grant PhD dissertation funding for EK; NIH under Grant R21AG063974 (PI: EF).

Acknowledgment

We thank all participants whose invaluable contributions made this research possible. This work was completed as part of the PhD dissertation of EK.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fresc.2023.1274191/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Wade DT. What is rehabilitation? An empirical investigation leading to an evidence-based description. Clin Rehabil. (2020) 34(5):571–83. doi: 10.1177/0269215520905112

2. Wade DT. Goal setting in rehabilitation: An overview of what, why and how. London, England: SAGE Publications Sage UK (2009).

3. Playford ED, Siegert R, Levack W, Freeman J. Areas of consensus and controversy about goal setting in rehabilitation: a conference report. Clin Rehabil. (2009) 23(4):334–44. doi: 10.1177/0269215509103506

4. Wade DT. Describing rehabilitation interventions. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Sage CA (2005).

5. Levack WM, Weatherall M, Hay-Smith EJ, Dean SG, McPherson K, Siegert RJ. Goal setting and strategies to enhance goal pursuit for adults with acquired disability participating in rehabilitation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2015) 2015(7):Cd009727. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009727.pub2

6. Levack W, Siegert RJ. Challenges in theory, practice and evidence. Rehabil Goal Setting Theory Pract Evid. (2014):3–20.

7. Wade DT. Goal planning in stroke rehabilitation: evidence. Top Stroke Rehabil. (1999) 6(2):37–42. doi: 10.1310/FMYJ-RKG1-YANB-WXRH

8. Kang E, Kim MY, Lipsey KL, Foster ER. Person-centered goal setting: a systematic review of intervention components and level of active engagement in rehabilitation goal-setting interventions. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. (2022) 103(1):121–30.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2021.06.025

9. McPherson KM, Kayes NM, Kersten P. MEANING as a smarter approach to goals in rehabilitation. Rehabil Goal Setting Theory Pract Evid. (2014):105–19.

10. Bovend'Eerdt TJ, Botell RE, Wade DT. Writing SMART rehabilitation goals and achieving goal attainment scaling: a practical guide. Clin Rehabil. (2009) 23(4):352–61. doi: 10.1177/0269215508101741

11. Rauch A, Cieza A, Stucki G. How to apply the international classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF) for rehabilitation management in clinical practice. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. (2008) 44(3):329–42.18762742

12. Allied Health Professions' Office of Queensland. Community rehabilitation learner guide support community access and participation. the State of Queensland (Queensland Health) (2017). Available from: https://www.health.qld.gov.au/ahwac/html/ahassist-modules (Accessed November 27, 2023).

13. World Health Organization. How to use the ICF: A practical manual for using the international classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF). Geneva: WHO (2013).

14. Holliday RC, Antoun M, Playford ED. A survey of goal-setting methods used in rehabilitation. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. (2005) 19(3):227–31. doi: 10.1177/1545968305279206

15. Plant S, Tyson SF. A multicentre study of how goal-setting is practised during inpatient stroke rehabilitation. Clin Rehabil. (2018) 32(2):263–72. doi: 10.1177/0269215517719485

16. Turner-Stokes L, Rose H, Ashford S, Singer B. Patient engagement and satisfaction with goal planning: impact on outcome from rehabilitation. Intern J Ther Rehabil. (2015) 22(5):210–6. doi: 10.12968/ijtr.2015.22.5.210

17. Cameron LJ, Somerville LM, Naismith CE, Watterson D, Maric V, Lannin NA. A qualitative investigation into the patient-centered goal-setting practices of allied health clinicians working in rehabilitation. Clin Rehabil. (2018) 32(6):827–40. doi: 10.1177/0269215517752488

18. Rosewilliam S, Sintler C, Pandyan AD, Skelton J, Roskell CA. Is the practice of goal-setting for patients in acute stroke care patient-centred and what factors influence this? A qualitative study. Clin Rehabil. (2016) 30(5):508–19. doi: 10.1177/0269215515584167

19. Parsons JGM, Plant SE, Slark J, Tyson SF. How active are patients in setting goals during rehabilitation after stroke? A qualitative study of clinician perceptions. Disabil Rehabil. (2018) 40(3):309–16. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2016.1253115

20. Stevens A, Beurskens A, Köke A, van der Weijden T. The use of patient-specific measurement instruments in the process of goal-setting: a systematic review of available instruments and their feasibility. Clin Rehabil. (2013) 27(11):1005–19. doi: 10.1177/0269215513490178

21. Fernandez ME, Ruiter RAC, Markham CM, Kok G. Intervention mapping: theory- and evidence-based health promotion program planning: perspective and examples. Front Public Health. (2019) 7:209. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00209

22. Whyte J, Hart T. It’s more than a black box; it’s a Russian doll: defining rehabilitation treatments. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. (2003) 82(8):639–52. doi: 10.1097/01.PHM.0000078200.61840.2D

23. Dijkers MP. Reporting on interventions: issues and guidelines for rehabilitation researchers. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. (2015) 96(6):1170–80. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2015.01.017

24. Haywood C, Martinez G, Pyatak EA, Carandang K. Engaging patient stakeholders in planning, implementing, and disseminating occupational therapy research. Am J Occup Ther. (2019) 73(1):7301090010p1–p9. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2019.731001

25. Backman CL, Davidson E, Martini R. Advancing patient and community engagement in occupational therapy research. Can J Occup Ther. (2022) 89(1):4–12. doi: 10.1177/00084174211072646

26. Levack WM, Dean SG, McPherson KM, Siegert RJ. Evidence-based goal setting: cultivating the science of rehabilitation. Rehab Goal Setting Theory Pract Evid. (2014):21–44.

27. Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA. Introduction to methods for community-based participatory research for health. In: Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, editors. Methods in community-based participatory research for health. San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated (2013). p. 1–38.

28. Guzman-Tordecilla DN, Lucumi D, Peña M. Using an intervention mapping approach to develop a program for preventing high blood pressure in a marginalized Afro-Colombian population: a community-based participatory research. J Prev. (2022) 43(2):209–24. doi: 10.1007/s10935-022-00668-1

29. Byrd TL, Wilson KM, Smith JL, Heckert A, Orians CE, Vernon SW, et al. Using intervention mapping as a participatory strategy: development of a cervical cancer screening intervention for hispanic women. Health Educ Behav. (2012) 39(5):603–11. doi: 10.1177/1090198111426452

30. Perry CK, McCalmont JC, Ward JP, Menelas HK, Jackson C, De Witz JR, et al. Mujeres fuertes y corazones saludables: adaptation of the StrongWomen-healthy hearts program for rural latinas using an intervention mapping approach. BMC Public Health. (2017) 17(1):982. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4842-2

31. Kang E, Foster ER. Use of implementation mapping with community-based participatory research: development of implementation strategies of a new goal setting and goal management intervention system. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:834473. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.834473

32. Kang E, Chen J, Foster ER. Feasibility, client-engagement, and person-centeredness of telehealth goal setting and goal management intervention. OTJR Occup Particip Health. (2023) 43(3):408–16. doi: 10.1177/15394492231172930

33. Kang E. Goal setting and goal management for chronic conditions: intervention and implementation strategies. St. Louis, MO: Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis (2023).

34. Bandura A. Social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective. Annu Rev Psychol. (2001) 52:1–26. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1

35. Bandura A, Freeman WH, Lightsey R. Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. J Cogn Psychother. (1999). 13(2). doi: 10.1891/0889-8391.13.2.158

36. Bandura A. Human agency in social cognitive theory. Am Psychol. (1989) 44(9):1175–84. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.44.9.1175

37. Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. (1977) 84(2):191–215. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

38. Deci EL, Ryan RM. The” what” and” why” of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol Inq. (2000) 11(4):227–68. doi: 10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

39. Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. (2000) 55(1):68. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

40. Bieleke M, Keller L, Gollwitzer PM. If-then planning. Eur Rev Soc Psychol. (2021) 32(1):88–102. doi: 10.1080/10463283.2020.1808936

41. Gollwitzer PM. Goal achievement: the role of intentions. Eur Rev Soc Psychol. (1993) 4(1):141–85. doi: 10.1080/14792779343000059

42. Gollwitzer PM. Implementation intentions: strong effects of simple plans. Am Psychol. (1999) 54(7):493. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.54.7.493

43. Kok G, Gottlieb NH, Peters GJ, Mullen PD, Parcel GS, Ruiter RA, et al. A taxonomy of behaviour change methods: an intervention mapping approach. Health Psychol Rev. (2016) 10(3):297–312. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2015.1077155

44. Young MD, Plotnikoff RC, Collins CE, Callister R, Morgan PJ. Social cognitive theory and physical activity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. (2014) 15(12):983–95. doi: 10.1111/obr.12225

45. Selzler AM, Moore V, Habash R, Ellerton L, Lenton E, Goldstein R, et al. The relationship between self-efficacy, functional exercise capacity and physical activity in people with COPD: a systematic review and meta-analyses. COPD. (2020) 17(4):452–61. doi: 10.1080/15412555.2020.1782866

46. Lippke S. Self-efficacy. In: Zeigler-Hill V, Shackelford TK, editors. Encyclopedia of personality and individual differences. Cham: Springer International Publishing (2020). p. 4713–9.

47. Fasbender U. Outcome expectancies. In: Zeigler-Hill V, Shackelford TK, editors. Encyclopedia of personality and individual differences. Cham: Springer International Publishing (2020). p. 3377–9.

48. Schwarzer R, Luszczynska A. Self-efficacy and outcome expectancies. In: Benyamini Y, Johnston M, Karademas EC, editors. Assessment in health psychology. Hogrefe Publishing. (2016). p. 31–44.27819459

49. Schwarzer R, Lippke S, Luszczynska A. Mechanisms of health behavior change in persons with chronic illness or disability: the health action process approach (HAPA). Rehabil Psychol. (2011) 56(3):161. doi: 10.1037/a0024509

50. Holliday RC, Ballinger C, Playford ED. Goal setting in neurological rehabilitation: patients’ perspectives. Disabil Rehabil. (2007) 29(5):389–94. doi: 10.1080/09638280600841117

51. Fischer S, Gauggel S, Trexler LE. Awareness of activity limitations, goal setting and rehabilitation outcome in patients with brain injuries. Brain Inj. (2004) 18(6):547–62. doi: 10.1080/02699050310001645793

52. Toglia JP. The dynamic interactional model of cognition in cognitive rehabilitation. In: Katz N, editor. Cognition, occupation, and participation across the life span: neuroscience, neurorehabilitation, and models of intervention in occupational therapy. American Occupational Therapy Association. (2011). p. 161–201.

53. Toglia J, Foster E. Goal setting and measuring functional outcomes. In: Toglia J, Foster E, editors. The multicontext approach to cognitive rehabilitation: a metacognitive strategy intervention to optimize functional cognition. Columbus, OH: Gatekeeper Press (2021). p. 163–75.

54. Lenzen SA, Daniëls R, van Bokhoven MA, van der Weijden T, Beurskens A. Disentangling self-management goal setting and action planning: a scoping review. PloS One. (2017) 12(11):e0188822. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0188822

Keywords: goals, patient care planning, intervention mapping, chronic conditions, occupational therapy, community-based participatory research, translational research

Citation: Kang E and Foster ER (2024) Development of a goal setting and goal management system: Intervention Mapping. Front. Rehabil. Sci. 4:1274191. doi: 10.3389/fresc.2023.1274191

Received: 7 August 2023; Accepted: 13 November 2023;

Published: 8 January 2024.

Edited by:

Jill Campbell Stewart, University of South Carolina, United StatesReviewed by:

Jaana Paltamaa, JAMK University of Applied Sciences, FinlandAlexandra Borstad, The College of St. Scholastica, United States

© 2024 Kang and Foster. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Eunyoung Kang ZXVueW91bmcua2FuZ0B1dGgudG1jLmVkdQ==

†Present Address: Eunyoung Kang, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Institute for Implementation Science, University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston, TX, United States

Eunyoung Kang

Eunyoung Kang Erin R. Foster

Erin R. Foster