- 1Department of Physical Therapy, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 2March of Dimes Canada, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 3Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, ON, Canada

- 4Department of Occupational Science and Occupational Therapy, Centre for Practice Changing Research, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 5The KITE Research Institute, University Health Network, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 6BioMedical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John’s, NL, Canada

Background: Community-based exercise programs delivered through healthcare-community partnerships (CBEP-HCPs) are beneficial to individuals with balance and mobility limitations. For the community to benefit, however, these programs must be sustained over time.

Purpose: To identify conditions influencing the sustainability of CBEP-HCPs for people with balance and mobility limitations and strategies used to promote sustainability based on experiences of program providers, exercise participants, and caregivers.

Methods: Using a qualitative collective case study design, we invited stakeholders (program providers, exercise participants, and caregivers) from sites that had been running a CBEP-HCP for people with balance and mobility limitations for ≥4 years; and sites where the CBEP-HCP had been discontinued, to participate. We used two sustainability models to inform development of interview guides and data analysis. Qualitative data from each site were integrated using a narrative approach to foster deeper understanding of within-organization experiences.

Results: Twenty-nine individuals from 4 sustained and 4 discontinued sites in Ontario (n = 6) and British Columbia (n = 2), Canada, participated. Sites with sustained programs were characterized by conditions such as need for the program in the community, presence of secure funding or cost recovery mechanisms, presence of community partners, availability of experienced and motivated instructors, and the capacity to allocate resources towards program marketing and participant recruitment. For sites where programs discontinued, diminished participation and/or enrollment and an inability to allocate sufficient financial, human, and logistical resources towards the program affected program continuity. Participants from discontinued sites also identified issues such as staff with low motivation and limited experience, and presence of competing programs within the organization or the community. Staff associated the absence of referral pathways, insufficient community awareness of the program, and the inability to recover program cost due to poor participation, with program discontinuation.

Conclusion: Sustainability of CBEP-HCPs for people with balance and mobility limitations is influenced by conditions that exist during program implementation and delivery, including the need for the program in the community, and organization and community capacity to bear the program's financial and resource requirements. Complex interactions among these factors, in addition to strategies employed by program staff to promote sustainability, influence program sustainability.

Introduction

Over the past decade, community-based exercise programs (CBEPs) have emerged to meet the demand for accessible and supervised exercise programs for individuals with balance and mobility limitations within their own communities (1). For people with stroke, participating in CBEPs has the potential to improve balance, mobility and functional independence, and reduce the risk of a recurrent stroke and secondary complications related to a sedentary lifestyle (2–4).

Not all CBEPs are informed by research evidence. CBEPs that integrate a novel healthcare-community partnership (CBEP-HCP) take advantage of complementary missions, infrastructure, and expertise of healthcare and recreation organizations to deliver an evidence-informed community-based exercise program (5). In this model, a healthcare partner (e.g., physical therapist, kinesiologist) is engaged to train and support fitness instructors to deliver a task-oriented exercise program targeting balance and mobility in community settings (5). Globally, various models of CBEP-HCP deliver programs to people with stroke such as the Adapted Physical Activity Program (6–8), a cycling program (9), Fit For Function (10), Fitness and Mobility Exercise (FAME) (11–13), Graded Repetitive Arm Supplementary Program (GRASP) (14), Neurological Exercise Training (NExT) (15), Together in Movement and Exercise (TIME™) (1, 5, 16), and Rehabilitation Training (ReTrain) (17).

Effective programs must be sustained to ensure continued access and benefit for community-dwelling people with balance and mobility limitations (18–21). Not all programs, however, are successful in the longer term and, in most cases, the reasons for discontinuation are not reported (22). Understanding factors that contribute to the success or failure of CBEP-HCPs is critical to ensuring future success.

The elements of program sustainability can be narrowed down to three domains: factors that exist within the organization implementing the program; factors that exist outside of the organization (broader community); and program features. Shediac–Rizkallah and Bone (23) proposed that exploring these three groups of factors allows for broad and open interpretation of sustainability. Using this model, Mancini and Marek (24) created a program sustainability index which identifies the individual factors within these three silos. Thus, combining the Shediac–Rizkallah and Bone (23) and the Mancini and Marek (24) models provides a structure enabling the exploration of factors governing sustainability at broader and granular levels.

In previous research, factors contributing to the sustainability of government- or research–funded health initiatives in the areas of mental health (25), cancer screening (26), substance abuse (27), smoking cessation (28), nutrition (29), and health promotion (29, 30), have been examined. Little attention has been paid to the sustainability of CBEP-HCPs in real world settings. Therefore, the primary objective of this study was to identify conditions influencing the sustainability of CBEP-HCPs and strategies implemented to promote sustainability based on experiences of users involved in program implementation and delivery, and exercise participants and their caregivers. A secondary objective was to develop a checklist of questions to aid organizations with sustaining CBEP-HCPs.

Materials and methods

Study design

We used a qualitative collective case study design to understand the experiences of key stakeholders involved with sites that sustained or discontinued a licensed CBEP-HCP called the Together in Movement and Exercise (TIME™) program (31). A case study approach is well-suited to study program sustainability as it permits in-depth exploration of a complex issue within a real-life context (32). We chose a collective case study design as it involves examination of multiple cases at a time to generate a broad understanding of the variation in experiences across “cases” (33). We used the Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) (34) to guide reporting. The University of Toronto health sciences research ethics board approved the study protocol.

Case selection

We selected the TIME™ program for the exploration of sustainability as developers have maintained records of program implementation, delivery and discontinuation. Following a demonstration of safety, feasibility, and potential benefit (5), the TIME™ program was adopted by more than 50 sites across Canada. Between 2008 and 2017, however, at least 15 centres discontinued the TIME™ program (personal communication with TIME™ program developers) for reasons that were not well understood.

Together in movement and exercise (TIME™) exercise program

The TIME™ program is a task-oriented, group exercise program designed to improve independence in everyday functioning among individuals with balance and mobility limitations (5). Trained fitness instructors, who are supported by healthcare partners [typically physical therapists (35)] and volunteers, deliver the program. The program relies on a partnership between a community organization that hosts the program and provides the resources (e.g., instructors, space, equipment, volunteers) and a healthcare partner (from a local hospital or community practice) who visits classes and serves as a resource for the instructors and supports participant enrollment directly by referring participants, or by creating referral pathways from local sources of participants (5, 22, 35). Other individuals involved in program implementation and delivery include recreation managers who are involved in decisions about whether or not to implement a program in the organization and program coordinators who oversee the program planning and allocation of resources. In some organizations the same individual may fulfil these roles (36).

Sampling and eligibility

The sampling frame consisted of a list of 52 sites with a license to offer the TIME™ program, including 37 sites currently offering the TIME™ program, and 15 sites that had discontinued the TIME™ program (as of April 2019). In consultation with TIME™ developers and members of the Canadian Advisory Collaborative for TIME™ (CAN-ACT), we developed a list of 8 sustained programs that had been running for at least 4 years and whose team would be potentially willing to share their experiences. Examining multiple cases spanning the spectrum of organizational identities, priorities and experiences was expected to provide a better understanding of the drivers and barriers of CBEP-HCP program sustainability. Similarly, we created a list of 8 discontinued programs where individuals who were involved with the program were still available and would potentially be willing to share their experiences. Each case was selected for its similarities or differences with respect to the outcome of interest (i.e., program sustainability) – ensuring theoretical replication, where the outcomes are contradictory (failed vs. successful sites) (33). Such comparative case studies are used to identify how features within the context influence the success of programs (33, 37).

Sites were considered eligible if they held a valid license from the University Health Network (Toronto, Canada) to run the TIME™ program, and fitness instructors that had been trained to deliver the TIME™ program. A sustained site had to meet the following additional criteria: currently offering or delivering the TIME™ program; have a healthcare partner; have delivered the TIME™ program at least once per year for the past four years; and intend to offer the TIME™ program for the next two years. A discontinued site had to meet the following criteria: have delivered at least one TIME™ program; discontinued offering the TIME™ program; have no plans to resume offering the TIME™ program.

Participant eligibility and recruitment

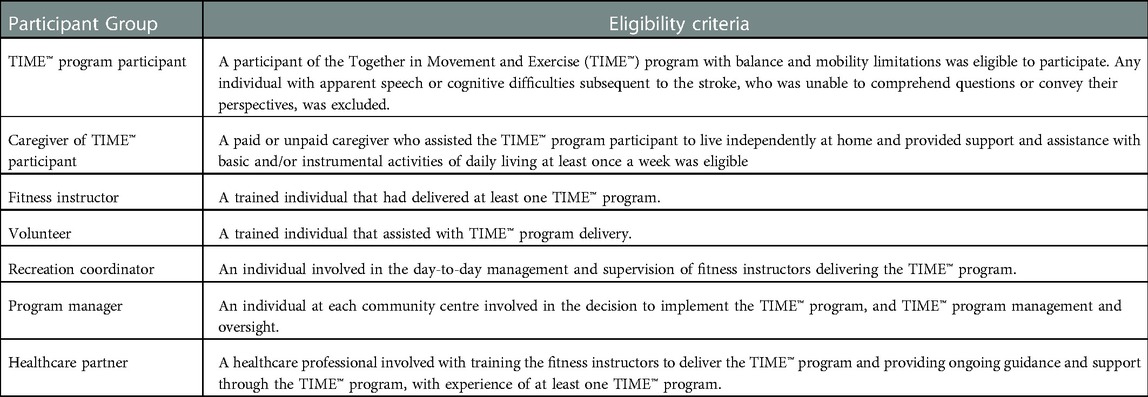

Information regarding the organization, its priorities, resources, and the processes involved can be best obtained from stakeholders involved in the organization, program delivery and program utilization (38). In the case of the TIME™ program, stakeholders included program managers, coordinators, instructors, volunteers, healthcare partners, program participants and their caregivers. Within each site, we aimed to recruit at least one participant for each stakeholder group based on the eligibility criteria detailed in Table 1. Use of a qualitative approach involving interviews with these stakeholders allowed us to obtain a detailed account of their experiences with the program for each case (site) (39, 40).

Sites were recruited via emails to the recreation manager or program coordinator. In sites where managers/coordinators agreed to participate, they were asked to identify and connect the lead researcher (GA) with at least one individual who was involved with the program as an instructor, healthcare partner, participant, caregiver, and volunteer, and expressed interest in knowing more about the study. The lead researcher contacted interested participants via telephone and obtained verbal informed consent from individuals who agreed to participate.

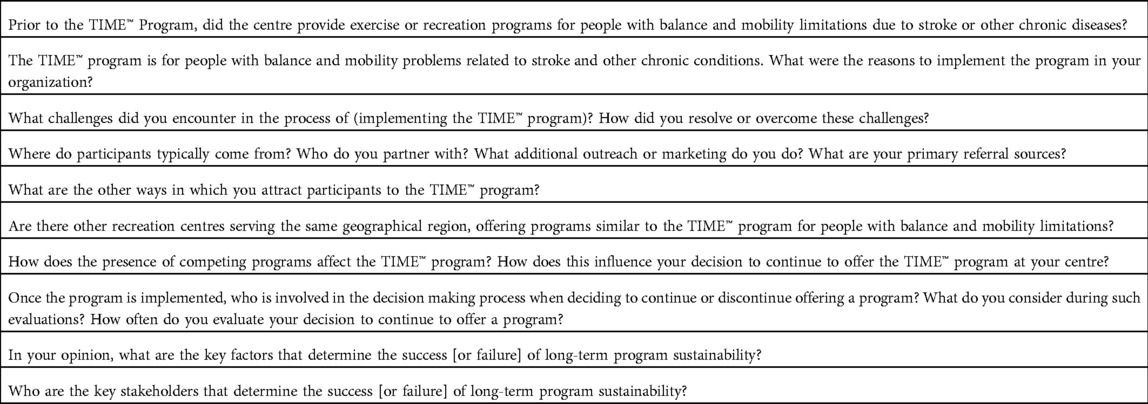

Data collection

Sustainability models by Shediac–Rizkallah and Bone (23) and Mancini and Marek (24) were used to develop interview guides tailored to each group. In keeping with the models, the interview guide included questions to explore the outer and inner contexts, and the influences of the program design on program implementation. For the purpose of this study, the inner context for the program was determined by the organizational and managerial structures and processes that support or pose challenges to program continuity. The outer setting included the community at large that was served by the program and is influenced by the political, economic and social environment within which the program functioned. Finally, the program design constituted human, logistical, and financial resources utilized and made available to the program for set-up, delivery, and continuation as well as the plan of action executed to implement the program. Table 2 presents sample interview questions. The interview guide was pilot tested with a fitness instructor with previous experience delivering the TIME™ program, and a previous participant of the TIME™ program. A single interviewer (GA), a cis-gender female physical therapy researcher with a PhD in rehabilitation science, 8 years of experience in stroke-related research, and 2 years of experience with qualitative research, completed one-on-one semi-structured interviews by telephone. Prior to beginning the recording, the interviewer shared their background, experience, and their academic interest in understanding program sustainability. The interviewer was unknown to the participants prior to the study. The participants attended the interview from their homes while the interviewer conducted the interview from a private workspace. Interviews lasted 45–60 min. Interviews were audio-recorded and professionally transcribed. The lead researcher (GA) and a trained research assistant (RA) verified transcripts for accuracy by comparing them to the audio-recordings.

Data analysis

De-identified transcripts were analyzed using a directed content analysis approach (41) and included deductive and inductive coding. The lead researcher (GA) developed a codebook a priori, which was reviewed by two members of the research team (NMS, JIC), based on the primary objective and the factors described in the two sustainability models. Two researchers (GA, NMS) independently reviewed and coded transcripts from one site and met to discuss codes. Based on this review, new codes were developed to capture information that could not be coded using existing codes based on the sustainability frameworks (codebook available on request). Then the lead researcher (GA) and the RA coded the remaining transcripts using NVivo 12. Data for each site were analyzed separately to develop case summaries. First, the lead researcher reviewed node reports and created within-site summaries that outlined the context of the setting, the mechanisms by which the program was implemented, and the description of how the sites continued to deliver the program or conditions that ultimately led to program discontinuation. Second, members of the research team (GA, NMS, IDG) met to review case summaries and discuss emerging themes and key concepts. Third, the lead researcher compared and contrasted the case summaries within the sustained and discontinued categories, and then across all cases. Conditions identified as influencing sustainability and actions taken to resolve challenges and ensure sustainability were compared across sustained and discontinued cases. An inductive approach was used to identify overlap in conditions and strategies across the sites. Finally, based on the recommendations and reflections of the study participants, the team created a list of questions that existing and new programs can use to guide program implementation and sustainability planning.

Strategies to ensure methodological rigor

Trustworthiness was enhanced by the development of a detailed research protocol and maintenance of an audit trail that allowed for transparency of the methods used to arrive at the conclusion (42, 43). The use of multiple sources of data within each case to obtain a holistic perspective improves the credibility of findings. A detailed description of each individual case (i.e., “a thick description”) provides information regarding the context within which the results have been obtained allowing for transferability of findings to other organizations (43).

Results

Site and participant characteristics

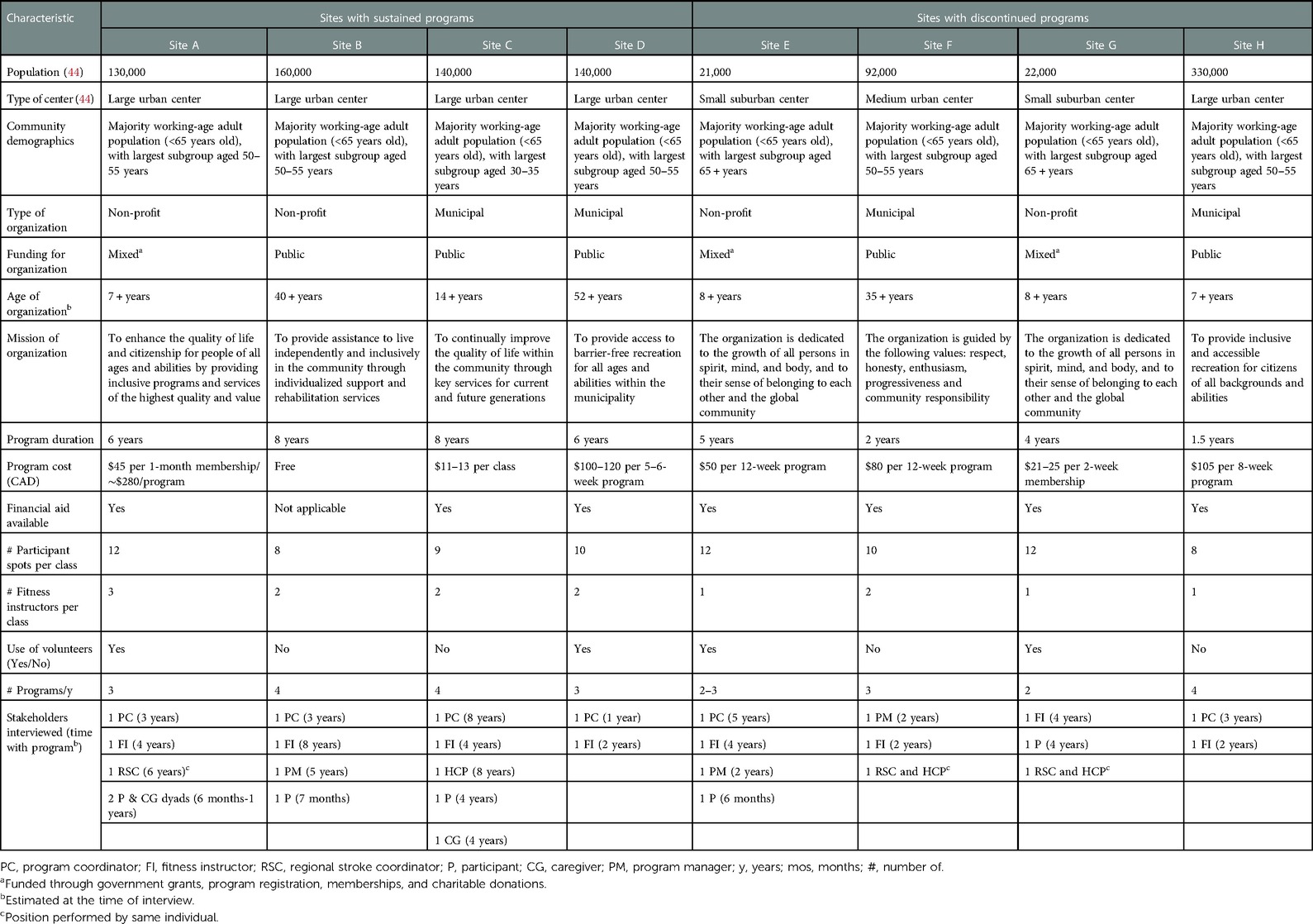

Twenty-eight individuals from programs at eight unique sites (four sustained and four discontinued; located in Ontario (n = 6) and British Columbia (n = 2)) participated in 27 interviews between April and August of 2019. Participants included 6 program coordinators, 8 fitness instructors, 3 program managers, 1 healthcare partner, 1 regional stroke coordinator/healthcare partner, 6 TIME™ participants, and 3 caregivers of TIME™ participants. Duration of participant involvement with the program ranged from 6 months to 8 years. Table 3 presents the characteristics of sites and participants.

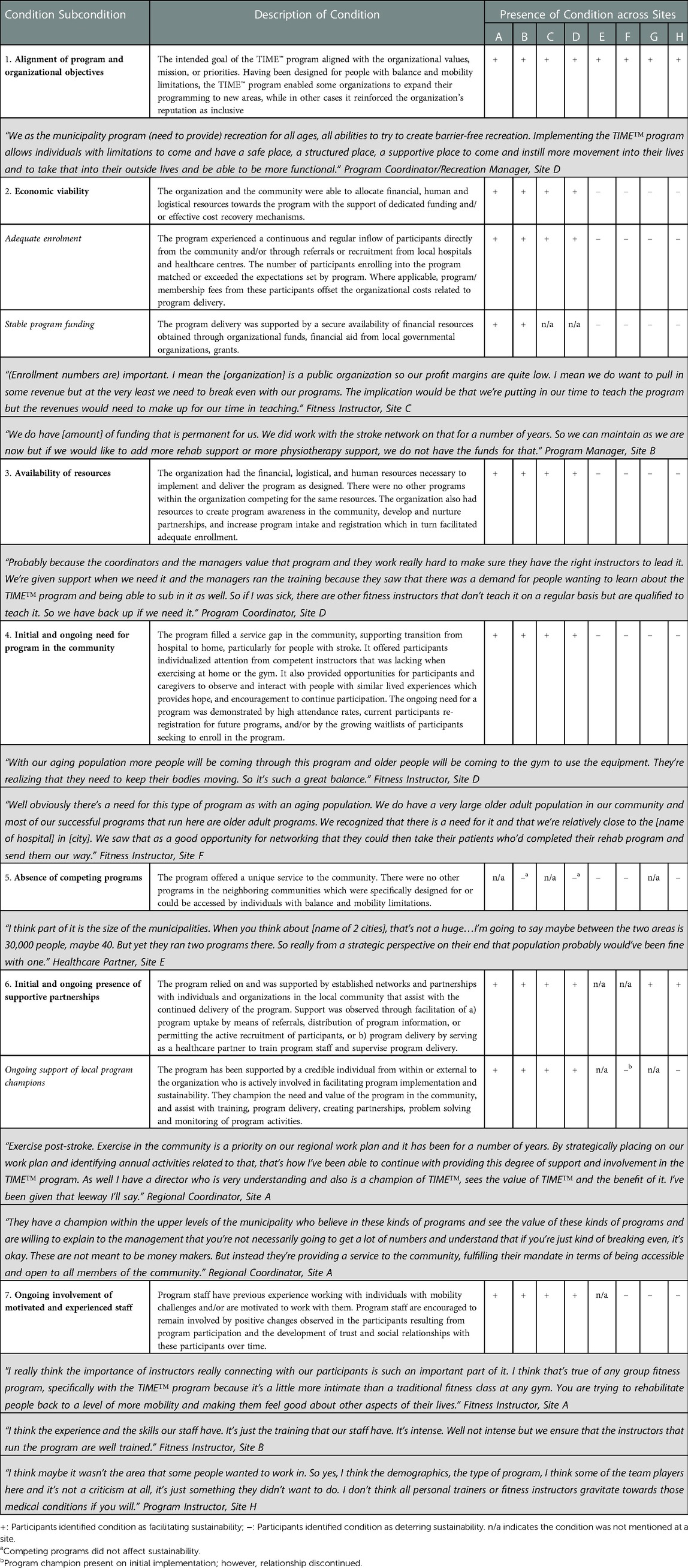

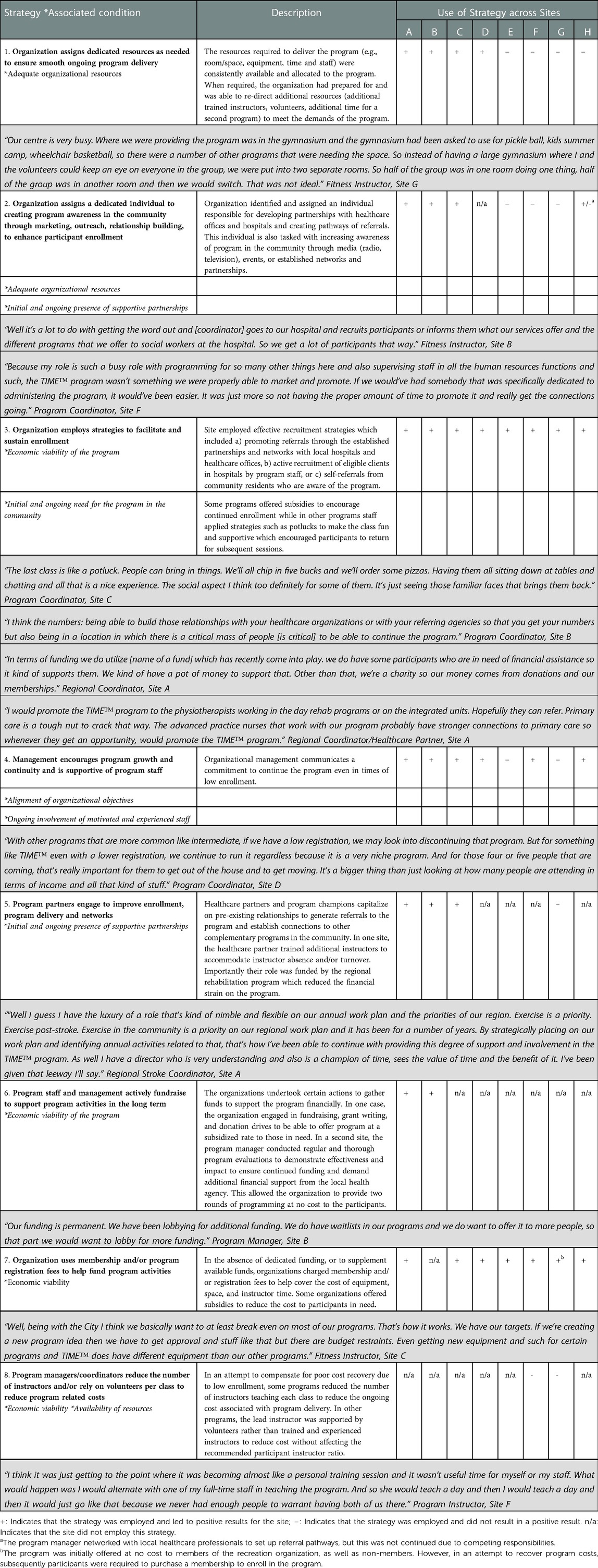

Based on the experiences of the participants from the sustained and discontinued programs, we identified 10 conditions that influenced the sustainability of the program. We defined conditions as the organizational, community and human factors that existed at the time of program implementation and delivery and influenced it either individually or through interaction. Table 4 describes each condition (and subcondition) with supporting quotes and the influence of each condition on sustainability at the sustained and discontinued sites.

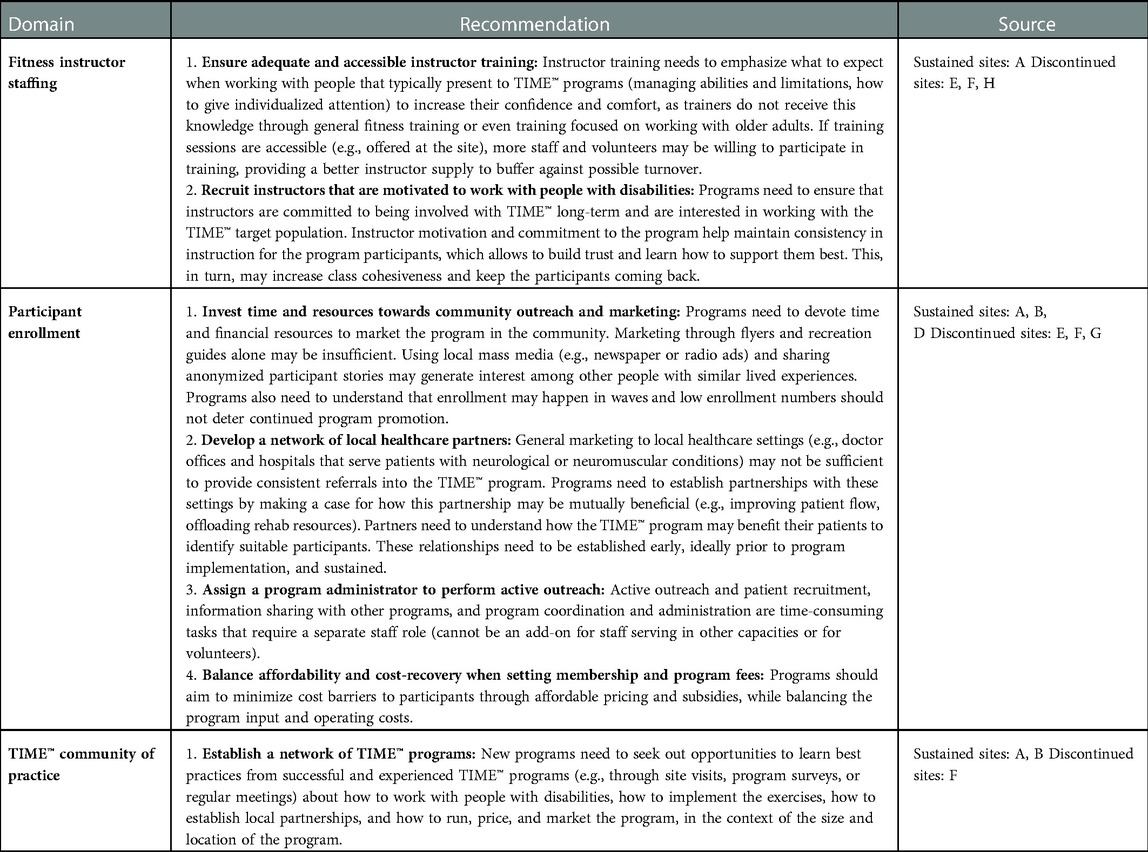

Recognizing the conditions that existed, program staff in some of the sites attempted to take actions to bolster the favorable conditions or resolve challenging conditions. We refer to these actions as strategies. With the sustained programs, the strategies employed were perceived to be effective in facilitating program continuity and sustainability. In contrast, in sites where program discontinued, staff efforts to influence sustainability failed to prevent discontinuation of the program. Table 5 describes the strategies with supporting quotes and the extent to which the strategies were employed at each site. Reflecting on their experiences, participants shared some recommendations on how other organizations can plan for sustainability that are summarized in Table 6.

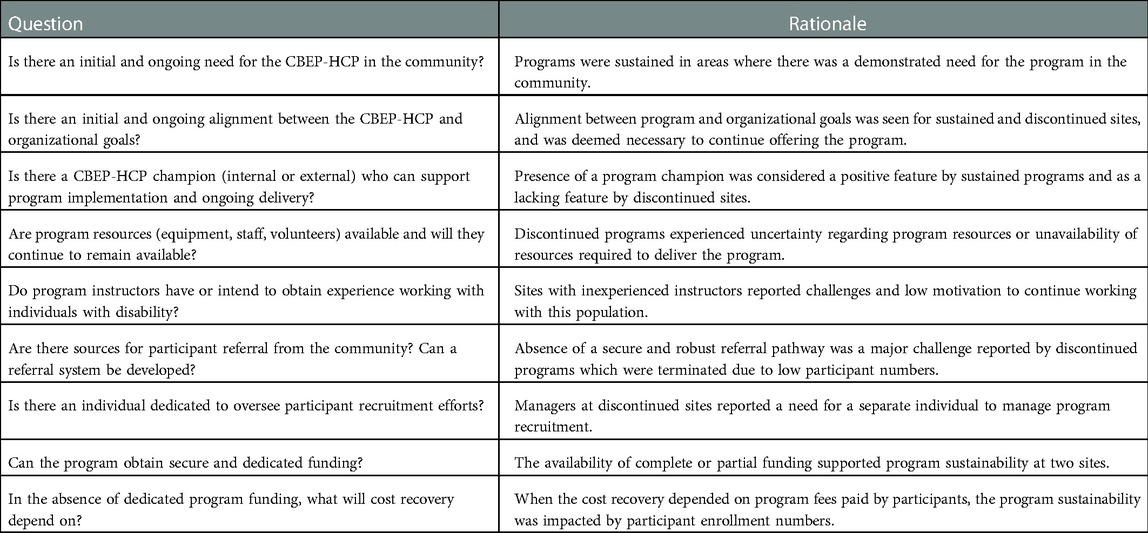

Based on the common conditions influencing program sustainability and the outcomes of the strategies employed by the sites where programs sustained and discontinued, we proposed a series of questions outlined in Table 7 that providers of new or existing programs may ask themselves to foresee challenges and create an environment conducive to program sustainability.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study of its kind to examine the sustainability of CBEP-HCPs that are implemented due to the interest of and initiatives of local organizational management, without guaranteed funding support from the program developers, researchers, local governments, or the healthcare system. Findings highlight factors that, individually and through complex interplays, contribute to the sustainability or discontinuation of a CBEP-HCP. Results suggest that the sustainability of an CBEP-HCP depends on the initial and continued presence of (1) alignment of program and organizational goals, (2) perceived need for program in the community, (3) presence of supportive partners and partnerships to create a referral pathway and increase awareness of program in the community, (4) presence of an experienced and motivated team of individuals involved in program implementation and delivery, and (5) organizational capacity, resources, and funding to support, promote and sustain the program.

The majority of existing research in the area of health program sustainability surround programs related to mental health, addiction, primary and acute care settings, discusses medical interventions or education programs. These programs are either led by researchers as a part of a research study or by government/local authorities as a part of health promotion programs and are supported by ear-marked funding (45). While the findings of this study align with previous research around sustainability of health programs in the community (45–48), the complex interplays we observed during case and cross-case analysis have not been discussed before for programs outside of the healthcare setting.

Factors influencing sustainability are interrelated and their influence can be modified by purposive action

Sustainability literature divides the factors influencing sustainability into certain sub-groups. Shediac–Rizkallah and Bone (23) model divided the factors broadly into elements within inner settings, outer settings, and program design factors; while more recent reviews such as by Lennox et al. (47) divided them into more distinctive categories such as initiative design and delivery, negotiating initiative process, people involved, resources, organizational setting, and the external environment. However, our study reveals that these factors are in fact not siloed. Rather, the sustainability of a program can be better explained by understanding the conditions created by interaction between these elements, as well as the dynamic influences of the actions taken by the program staff to boost positive elements and mitigate challenge.

Together the characteristics of the inner setting, outer setting and program design interact and influence each other to create an environment where a program thrives and grows or fails to achieve expectations and naturally discontinues or is terminated. For example, the environment for the sustained program can be described as one where the program staff support and encourage the allocation of resources towards a program for which there is an ongoing need in the community. The staff are in turn supported by partnerships and networks that provide ongoing assistance to program delivery. They employed strategies such as fundraising to financially support the program, building networks with a source of participants to promote referral, and providing subsidies to encourage participation.

With discontinued programs, challenging conditions were aggravated by unsuccessful strategies. For example, poor program enrollment due to the presence of competing programs led to reduced motivation among program staff and poor cost recovery. Strategies such as program promotion or reducing number of staff to minimize costs were not sufficient to revive the program and led to program termination. Authors (49, 50) have previously discussed the interaction of these factors but this is the first study to demonstrate the nature of the interaction and the resulting impact of program sustainability in real-world cases.

Our study also expanded on the descriptions (45) of some of the factors thought to influence sustainability from a community-based exercise program perspective. In the case of CBEP-HCPs like the TIME™ program, which are designed for a specific sub-group of individuals, program need is not only reflected in the enrollment of new participants but also the reenrollment of existing participants. In this case, the ability to remain involved for a prolonged period is important to the participants who often require long-term participation to make and maintain health gains and prevent deconditioning. From an organizational standpoint, need for the program in the community also includes the absence of competing programs and the ability of the program to add value (51, 52) – either through alignment with the organizational vision or by creating opportunities to expand their client base.

The need for the program must be complemented by a pathway that connects those who need the program to the program. Both sustained and discontinued programs underscored the need for secure and consistent sources that can refer participants to the program, and for an individual who is responsible for developing networks with these sources of potential participants. For this role, three of the four sustained programs relied on a program staff (healthcare partner, or program coordinator) who had connections and experience in both healthcare and community setting and were able to bridge the gap between the two. Referred to as a boundary spanner (53), these individuals use their connections and presence within both settings to increase awareness of program presence among healthcare professionals and potential participants. When facilitated by an individual in a boundary spanning role, there is an increase in the referrals from important, long-standing sources of clients such as hospitals, community healthcare centres (54, 55) compared to advertisements or marketing. When present, program champions - individuals who believe in and support the program and its potential for impact-helped to increase organizational, and community buy-in for the program, support training, aid in resolving challenges and maintain motivation (56, 57).

Results showed that for a program that involves long-term clients, having experienced and motivated instructors facilitates participant retention. Participants, especially individuals with disabilities, rely on developing long-standing associations with instructors who become aware of the participants’ needs and abilities, and can develop a sense of trust over time (58). Experienced and motivated instructors are also important from a program delivery standpoint as not many instructors have experience and willingness to work with clients who are at a risk for falls or have disabilities (22, 58, 59). As seen in the sustained programs, their commitment to affect positive change motivates them to remain involved in the program thereby reduces staff turnover and costs associated with training and employing new instructors. Similarly, as was reflective in the sustained and discontinued programs, the capacity to allocate supportive resources (volunteers, appropriate space, and equipment) is important to keep the instructors engaged and motivated.

Resource availability is inextricably connected to the availability of funds to support program implementation and delivery. Funding is a complex factor as it depends on the type of organization (private vs. municipal vs. charity), their business model (for-profit vs. not-for-profit), their source of funds (fee-for-service, donations, federal grants etc.), and the assurance of ongoing availability funds for the program. As seen in this study, the availability of ear-marked funding for the program provided a secure foundation for two sustained programs allowing them to engage more staff, offer incentives for participation, and dedicate resources towards the program. The importance of financial support for sustainability while not novel, assumes greater significance when program implementation is initiated at grassroot levels rather than those driven by academic research or government initiatives. Organizations can benefit from resources that indicate the costs involved in program implementation to help with planning for program implementation and continued delivery (60).

The need to plan for sustainability

The ultimate aim of program sustainability is to ensure that the health benefits to the target population are maintained and that the program is continually accessible to existing and new participants. In the absence of other alternatives, discontinuation of effective programs may result in participants discontinuing engaging in exercises due to a fear or adverse effects, or lack of knowledge of how to exercise safely when experiencing balance and mobility limitations (59, 61). The resulting sedentary lifestyle may cause loss of improvements, deterioration in health, and other secondary complications (62–64).

This study demonstrates that program sustainability cannot be guaranteed by the mere presence of positive factors. It depends on the conditions surrounding the program at the time as well as the strategies employed by the program staff to promote positive influences and overcome challenges. These conditions may change over time. Some authors (46, 65) argue that innovations often go through phases of relative stability interspersed with periods of adaptation. For example, program need may be affected by the emergence of a new competing program, or changes in the demographic composition of the community or priorities of the organization/local community.

It is important to note that the discontinued programs did not anticipate challenges at the time of implementation. Regular monitoring of the conditions surrounding the program could allow program staff to prospectively engage corrective strategies when required. Bodkin and Hakami (45) suggest that challenges and opportunities can be identified through SWOT (strength, weakness, opportunities and threats) analyses. An assessment of the environment and the local context surrounding the implementation will reflect what the needs are, what challenges are specific to the local context, and if the needs are already met. If program delivery can be adapted to the needs, then the organization can avoid program discontinuation.

Studies on program sustainability recommended that planning for sustainability should begin early in a program's life cycle (66, 67). Asking questions such as the ones listed in Table 7 will help the planning team foresee and prepare for challenges or barriers. Understanding the experiencing of different organizations may serve as valuable lessons or examples for other teams considering implementing or re-designing a CBEP-HCP. Similarly, existing and future programs could benefit from the development of a community of practice of CBEP-HCPs where program staff could share experiences, resolve challenges and provide support to each other to promote program sustainability, growth and expansion. Future research should focus on identifying potential solutions to the key challenges of recruitment, program funding, and creating supporting partnerships.

Limitations and considerations

The sites that participated in this study reflect the heterogeneity of the recreation centres in the community including sites run by the local government/municipality, as well as private, for-profit and not-for-profit organizations. All the programs in this study, however, were located in urban or sub-urban centres; the experience of programs in rural centres is missing. This is important as the priorities and needs of rural centres and the resources available may be unique. The participating sites also belonged to two provinces in Canada: Ontario and British Columbia. The outcomes of programs implemented in other provinces may differ based on their priorities and the resources available to them. These factors may impact the transferability of the findings to other regions.

Conclusion

Sustainability of CBEP-HCPs for people with balance and mobility limitations is influenced by a complex interaction of conditions surrounding the program and the actions taken by the individuals involved in program implementation and delivery. Understanding what the conditions are and how they interact before implementing the program can stimulate corrective actions, where required, to prevent discontinuation of effective CBEP-HCPs for people with balance and mobility limitations.

Data availability statement

Data are not available as participants did not consent to data sharing. Enquiries should be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the University of Toronto health sciences research ethics board. Individuals provided verbal informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

GA: designed the original study in consultation with IDG, JIC, MP, and NMS. GA: collected and analyzed the data in consultation with IDG, JIC, and NMS. GA: drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This project was funded by Brain Canada and the Heart and Stroke Foundation Canadian Partnership for Stroke Recovery. NMS held a Heart and Stroke Foundation Mid-Career Investigator Award and the Toronto Rehabilitation Institute Chair at the University of Toronto to complete this work.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dominika Bhatia, Margot Catizzone, Diane Tse, and Jo-Anne Howe for their contribution to this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Merali S, Cameron JI, Barclay R, Salbach NM. Characterising community exercise programmes delivered by fitness instructors for people with neurological conditions: a scoping review. Health Soc Care Community. (2016) 24(6):e101–16. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12282

2. Billinger SA, Boyne P, Coughenour E, Dunning K, Mattlage A. Does aerobic exercise and the FITT principle fit into stroke recovery? Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. (2015) 15(2):519. doi: 10.1007/s11910-014-0519-8

3. Deijle IA, Van Schaik SM, Van Wegen EEH, Weinstein HC, Kwakkel G, Van den Berg-Vos RM. Lifestyle interventions to prevent cardiovascular events after stroke and transient ischemic attack: systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke. (2017) 48(1):174–9. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.013794

4. Galloway M, Marsden DL, Callister R, Erickson KI, Nilsson M, English C. What is the dose-response relationship between exercise and cardiorespiratory fitness after stroke? A systematic review. Phys Ther. (2019) 99(7):821–32. doi: 10.1093/ptj/pzz038

5. Salbach NM, Howe JA, Brunton K, Salisbury K, Bodiam L. Partnering to increase access to community exercise programs for people with stroke, acquired brain injury, and multiple sclerosis. J Phys Act Health. (2014) 11(4):838–45. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2012-0183

6. Stuart M, Benvenuti F, Macko R, Taviani A, Segenni L, Mayer F, et al. Community-based adaptive physical activity program for chronic stroke: feasibility, safety, and efficacy of the empoli model. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. (2009) 23(7):726–34. doi: 10.1177/1545968309332734

7. Stuart M, Dromerick AW, Macko R, Benvenuti F, Beamer B, Sorkin J, et al. Adaptive physical activity for stroke: an early-stage randomized controlled trial in the United States. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. (2019) 33(8):668–80. doi: 10.1177/1545968319862562

8. Duret C, Breuckmann P, Louchart M, Kyereme F, Pepin M, Koeppel T. Adapted physical activity in community-dwelling adults with neurological disorders: design and outcomes of a fitness-center based program. Disabil Rehabil. (2022) 44(4):536–41. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2020.1771439

9. Kerr A, Cummings J, Barber M, McKeown M, Rowe P, Mead G, et al. Community cycling exercise for stroke survivors is feasible and acceptable. Top Stroke Rehabil. (2019) 26(7):485–90. doi: 10.1080/10749357.2019.1642653

10. Richardson J, Tang A, Guyatt G, Thabane L, Xie F, Sahlas D, et al. FIT for FUNCTION: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. (2018) 19(1):39. doi: 10.1186/s13063-017-2416-3

11. Marigold DS, Eng JJ, Dawson AS, Inglis JT, Harris JE, Gylfadottir S. Exercise leads to faster postural reflexes, improved balance and mobility, and fewer falls in older persons with chronic stroke: exercise in older adults with stroke. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2005) 53(3):416–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53158.x

12. Pang MYC, Eng JJ, Dawson AS, McKay HA, Harris JE. A community-based fitness and mobility exercise program for older adults with chronic stroke: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2005) 53(10):1667–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53521.x

13. Eng JJ, Chu KS, Kim CM, Dawson AS, Carswell A, Hepburn KE. A community-based group exercise program for persons with chronic stroke. Med Sci Sports Exerc. (2003) 35(8):1271–8. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000079079.58477.0B

14. Yang CL, Bird ML, Eng JJ. Implementation and evaluation of the Graded Repetitive Arm Supplementary Program (GRASP) for people with stroke in a real world community setting: case report. Phys Ther. (2021) 101(3):pzab008. doi: 10.1093/ptj/pzab008

15. Regan EW, Handlery R, Liuzzo DM, Stewart JC, Burke AR, Hainline GM, et al. The Neurological Exercise Training (NExT) program: a pilot study of a community exercise program for survivors of stroke. Disabil Health J. (2019) 12(3):528–32. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2019.03.003

16. Merali S, Cameron JI, Barclay R, Salbach NM. Experiences of people with stroke and multiple sclerosis and caregivers of a community exercise programme involving a healthcare-recreation partnership. Disabil Rehabil. (2020) 42(9):1220–6. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2018.1519042

17. Dean SG, Poltawski L, Forster A, Taylor RS, Spencer A, James M, et al. Community-based rehabilitation training after stroke: results of a pilot randomised controlled trial (ReTrain) investigating acceptability and feasibility. BMJ Open. (2018) 8(2):e018409. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018409

18. Pluye P, Potvin L, Denis JL, Pelletier J. Program sustainability: focus on organizational routines. Health Promot Int. (2004) 19(4):489–500. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dah411

19. Manfredi C, Crittenden K, Cho YI, Engler J, Warnecke R. Maintenance of a smoking cessation program in public health clinics beyond the experimental evaluation period. Public Health Rep. (2001) 116(Suppl 1):120–35. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.s1.120

20. Minkler M, Vásquez VB, Warner JR, Steussey H, Facente S. Sowing the seeds for sustainable change: a community-based participatory research partnership for health promotion in Indiana, USA and its aftermath. Health Promot Int. (2006) 21(4):293–300. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dal025

21. Hanson HM, Salmoni AW. Stakeholders’ perceptions of programme sustainability: findings from a community-based fall prevention programme. Public Health. (2011) 125(8):525–32. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2011.03.003

22. Salbach NM, Howe JA, Baldry D, Merali S, Munce SEP. Considerations for expanding community exercise programs incorporating a healthcare-recreation partnership for people with balance and mobility limitations: a mixed methods evaluation. BMC Res Notes. (2018) 11(1):214. doi: 10.1186/s13104-018-3313-x

23. Shediac-Rizkallah MC, Bone LR. Planning for the sustainability of community-based health programs: conceptual frameworks and future directions for research, practice and policy. Health Educ Res. (1998) 13(1):87–108. doi: 10.1093/her/13.1.87

24. Mancini JA, Marek LI. Sustaining community-based programs for families: conceptualization and measurement*. Fam Relat. (2004) 53(4):339–47. doi: 10.1111/j.0197-6664.2004.00040.x

25. Glaser EM. Durability of innovations in human service organizations: a case-study analysis. Knowledge. (1981) 3(2):167–85. doi: 10.1177/107554708100300204

26. Shediac-Rizkallah MC, Scheirer M, Cassady C. Sustainability of the coordinated breast cancer screening program. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University School of Hygiene and Public Health (1997).

27. Paine-Andrews A, Fisher J, Campuzano M, Fawcett S, Berkley-Patton J. Promoting sustainability of community health initiatives: an empirical case study. Health Promot Pract. (2000) 1:249–58. doi: 10.1177/152483990000100311

28. Lichtenstein E, Thompson B, Nettekoven L, Corbett K. Durability of tobacco control activities in 11 north American communities: life after the community intervention trial for smoking cessation (COMMIT). Health Educ Res. (1996) 11(4):527–34. doi: 10.1093/her/11.4.527

29. Elder JP, Campbell NR, Candelaria JI, Talavera GA, Mayer JA, Moreno C, et al. Project Salsa: development and institutionalization of a nutritional health promotion project in a Latino community. Am J Health Promot AJHP. (1998) 12(6):391–401. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-12.6.391

30. Bracht N, Finnegan JR, Rissel C, Weisbrod R, Gleason J, Corbett J, et al. Community ownership and program continuation following a health demonstration project. Health Educ Res. (1994) 9(2):243–55. doi: 10.1093/her/9.2.243

31. Together in movement and exercise. Available at: https://www.uhn.ca/TorontoRehab/Clinics/TIME

32. Flyvbjerg B. Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Sosiol Tidsskr. (2004) 12(2):117–42. doi: 10.18261/ISSN1504-2928-2004-02-02

33. Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, Huby G, Avery A, Sheikh A. The case study approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2011) 11:100. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-100

34. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. (2007) 19(6):349–57. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

35. Alsbury-Nealy K, Colquhoun H, Jaglal SB, Munce S, Salbach NM. Referrals from healthcare professionals to community-based exercise programs targeting people with balance and mobility limitations: an interviewer-administered survey. Physiother Can. (2022). doi: 10.3138/ptc-2022-0069. [Epub ahead of print]

36. Skrastins O, Tsotsos S, Aqeel H, Qiang A, Renton J, Howe JA, et al. Fitness coordinators’ and fitness instructors’ perspectives on implementing a task-oriented community exercise program within a healthcare-recreation partnership for people with balance and mobility limitations: a qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil. (2020) 42(19):2687–95. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2019.1570357

37. Zucker DM. How to do case study research. Teaching Res Soc Sci. (2009) 2. Available from: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/nursing_faculty_pubs/2.

38. Concannon TW, Grant S, Welch V, Petkovic J, Selby J, Crowe S, et al. Practical guidance for involving stakeholders in health research. J Gen Intern Med. (2019) 34(3):458–63. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4738-6

39. Melder A, Burns P, Mcloughlin I, Teede H. Examining “institutional entrepreneurship” in healthcare redesign and improvement through comparative case study research: a study protocol. BMJ Open. (2018) 8(8):e020807. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020807

40. Goodrick D. Comparative case studies, methodological briefs: Impact evaluation 9. Florence: UNICEF, Office of Research (2014).

41. Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. (2008) 62(1):107–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

42. Carcary M. The research audit trail: methodological guidance for application in practice. Electron J Bus Res Methods. (2020) 18(2). doi: 10.34190/JBRM.18.2.008

43. Curtin M, Fossey E. Appraising the trustworthiness of qualitative studies: guidelines for occupational therapists. Aust Occup Ther J. (2007) 54(2):88–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1630.2007.00661.x

44. Statistics Canada. Available at: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/details/page.cfm?Lang=E&Geo1=POPC&Code1=0904&Geo2=PR&Code2=35&SearchText=Sudbury&SearchType=Begins&SearchPR=01&B1=All&GeoLevel=PR&GeoCode=0904&TABID=1&type=0.

45. Bodkin A, Hakimi S. Sustainable by design: a systematic review of factors for health promotion program sustainability. BMC Public Health. (2020) 20(1):964. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09091-9

46. Hailemariam M, Bustos T, Montgomery B, Barajas R, Evans LB, Drahota A. Evidence-based intervention sustainability strategies: a systematic review. Implement Sci. (2019) 14(1):57. doi: 10.1186/s13012-019-0910-6

47. Lennox L, Maher L, Reed J. Navigating the sustainability landscape: a systematic review of sustainability approaches in healthcare. Implement Sci. (2018) 13(1):27. doi: 10.1186/s13012-017-0707-4

48. Whelan J, Love P, Pettman T, Doyle J, Booth S, Smith E, et al. Cochrane update: predicting sustainability of intervention effects in public health evidence: identifying key elements to provide guidance. J Public Health Oxf Engl. (2014) 36(2):347–51. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdu027

49. Gruen RL, Elliott JH, Nolan ML, Lawton PD, Parkhill A, McLaren CJ, et al. Sustainability science: an integrated approach for health-programme planning. Lancet. (2008) 372(9649):1579–89. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61659-1

50. Wiltsey Stirman S, Kimberly J, Cook N, Calloway A, Castro F, Charns M. The sustainability of new programs and innovations: a review of the empirical literature and recommendations for future research. Implement Sci. (2012) 7(1):17. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-17

51. Proctor E, Luke D, Calhoun A, McMillen C, Brownson R, McCrary S, et al. Sustainability of evidence-based healthcare: research agenda, methodological advances, and infrastructure support. Implement Sci. (2015) 10(1):88. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0274-5

52. Aravind G, Bashir K, Cameron JI, Howe JA, Jaglal SB, Bayley MT, et al. Community-based exercise programs incorporating healthcare-community partnerships to improve function post-stroke: feasibility of a 2-group randomized controlled trial. Pilot Feasibility Stud. (2022) 8(1):88. doi: 10.1186/s40814-022-01037-9

53. Goodrich KA, Sjostrom KD, Vaughan C, Nichols L, Bednarek A, Lemos MC. Who are boundary spanners and how can we support them in making knowledge more actionable in sustainability fields? Curr Opin Environ Sustain. (2020) 42:45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2020.01.001

54. Etz RS, Cohen DJ, Woolf SH, Holtrop JS, Donahue KE, Isaacson NF, et al. Bridging primary care practices and communities to promote healthy behaviors. Am J Prev Med. (2008) 35(5):S390–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.08.008

55. Krist AH, Shenson D, Woolf SH, Bradley C, Liaw WR, Rothemich SF, et al. Clinical and community delivery systems for preventive care. Am J Prev Med. (2013) 45(4):508–16. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.06.008

56. Miech EJ, Rattray NA, Flanagan ME, Damschroder L, Schmid AA, Damush TM. Inside help: an integrative review of champions in healthcare-related implementation. SAGE Open Med. (2018) 6:2050312118773261. doi: 10.1177/2050312118773261

57. Alsbury-Nealy K, Scodras S, Munce S, Colquhoun H, Jaglal SB, Salbach NM. Models for establishing linkages between healthcare and community: a scoping review. Health Soc Care Community. (2022) 30(6):e3904–20. doi: 10.1111/hsc.14096

58. Nikolajsen H, Sandal LF, Juhl CB, Troelsen J, Juul-Kristensen B. Barriers to, and facilitators of, exercising in fitness centres among adults with and without physical disabilities: a scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18(14):7341. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18147341

59. Rimmer JH, Wang E, Smith D. Barriers associated with exercise and community access for individuals with stroke. J Rehabil Res Dev. (2008) 45(2):315–22. doi: 10.1682/JRRD.2007.02.0042

60. Aravind G, Bashir K, Cameron JI, Bayley MT, Teasell RW, Howe JA, et al. Experiences of recreation and healthcare managers and providers with first-time implementation of a community-based exercise program for people post-stroke: a theory-based qualitative study and cost analysis (in review). Front Rehabil Sci. (2022) 2022. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2007.02.0042

61. Billinger SA, Arena R, Bernhardt J, Eng JJ, Franklin BA, Johnson CM, et al. Physical activity and exercise recommendations for stroke survivors: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American heart association/American stroke association. Stroke. (2014) 45(8):2532–53. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000022

62. US Department of Health and Human Services. 2018 Physical activity guidelines advisory committee. 2018 Physical activity guidelines advisory committee scientific report (2018).

63. Biswas A, Oh PI, Faulkner GE, Bajaj RR, Silver MA, Mitchell MS, et al. Sedentary time and its association with risk for disease incidence, mortality, and hospitalization in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. (2015) 162(2):123–32. doi: 10.7326/M14-1651

64. Saunders DH, Mead GE, Fitzsimons C, Kelly P, van Wijck F, Verschuren O, et al. Interventions for reducing sedentary behaviour in people with stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 6(6):CD012996. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012996.pub2.34184251

65. Tushman ML, Newman WH, Romanelli E. Convergence and upheaval: managing the unsteady pace of organizational evolution. Calif Manage Rev. (1986) 29(1):29–44. doi: 10.2307/41165225

66. Scheirer MA. Is sustainability possible? A review and commentary on empirical studies of program sustainability. Am J Eval. (2005) 26(3):320–47. doi: 10.1177/1098214005278752

Keywords: community exercise, balance, mobility, implementation, sustainability, case study, healthcare-community partnerships, qualitative research

Citation: Aravind G, Graham ID, Cameron JI, Ploughman M and Salbach NM (2023) Conditions and strategies influencing sustainability of a community-based exercise program incorporating a healthcare-community partnership for people with balance and mobility limitations in Canada: A collective case study of the Together in Movement and Exercise (TIME™) program. Front. Rehabil. Sci. 4:1064266. doi: 10.3389/fresc.2023.1064266

Received: 8 October 2022; Accepted: 25 January 2023;

Published: 27 February 2023.

Edited by:

Ada Leung, University of Alberta, CanadaReviewed by:

Zhuoying Qiu, China Rehabilitation Research Center/WHO Collaborating Center for Family International Classifications, ChinaNatalia Sharashkina, Pirogov Russian National Research Medical University, Russia

Elizabeth Regan, University of South Carolina, United States

© 2023 Aravind, Graham, Cameron, Ploughman and Salbach. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nancy M. Salbach nancy.salbach@utoronto.ca

Specialty Section: This article was submitted to Translational Research in Rehabilitation, a section of the journal Frontiers in Rehabilitation Sciences

Gayatri Aravind

Gayatri Aravind