95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Rehabil. Sci. , 09 December 2022

Sec. Strengthening Rehabilitation in Health Systems

Volume 3 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fresc.2022.999973

This article is part of the Research Topic Leadership in Teamwork: Enhancing Rehabilitation Medicine Best Practice View all 6 articles

Gillian King1*

Gillian King1* Laura R. Bowman2

Laura R. Bowman2 C. J. Curran3

C. J. Curran3 Anna Oh3

Anna Oh3 Laura Thompson2

Laura Thompson2 Carolyn McDougall2

Carolyn McDougall2 Dolly Menna-Dack3

Dolly Menna-Dack3 Laura Howson-Strong2

Laura Howson-Strong2

Aims: The aim was to describe an innovative initiative that took place in a pediatric rehabilitation hospital. The goal of this organization-wide strategic initiative, called the Transition Strategy, was to improve service delivery to children/youth with disabilities and their families at times of life transition. The research question was: What are the key elements that have contributed to the success of the Strategy, from the perspective of team members? The objectives were to describe: (a) the guiding principles underlying team functioning and team practices, (b) key enablers of positive team functioning, (c) the nature of effective team practices, and (d) lessons learned.

Methods: A holistic descriptive case study was conducted, utilizing historical documents, tracked outcome data, and the experiences and insights of multidisciplinary team members (the authors). Reflecting an insiders' perspective, the impressions of team members were key sources of data. The perspectives of team members were used to generate key teamwork principles, enablers of team functioning, team practices, and key learnings.

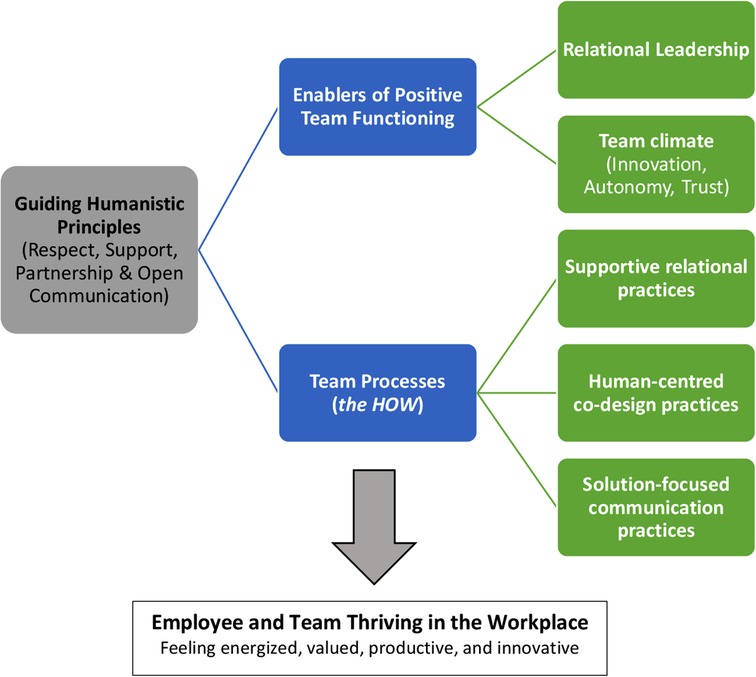

Findings and Discussion: Team members identified four guiding humanistic principles (respect, support, partnership, and open communication). These principles underpinned three novel practices that contributed to team effectiveness in the eyes of team members: supportive relational practices, human-centered co-design, and solution-focused communication. Key enablers were the relational style of leadership, and a team climate of innovation, autonomy, and trust, supported by the organizational vision. This team climate fostered a sense of psychological safety, thereby encouraging both experimentation and learning from failure.

Conclusions: This article provides information for other healthcare organizations interested in understanding the Strategy's value and its implementation. It provides a practical example of how to adopt a humanistic approach to health care, leading to both innovative service development and thriving among team members.

“Fallen through the cracks”, “left stranded”, and “lost in the system”: These metaphors describe the demoralizing state of affairs experienced by many youth with disabilities as they transition to adulthood (1–3). They also indicate the widespread need for an initiative or approach to address the shortcomings of the healthcare system, as it often fails to address the needs and aspirations of children and youth with disabilities, particularly at times of transition such as from post-secondary education to adult roles (4).

Transition is a complex and multifaceted process requiring partnerships among young people, their families, service providers, and healthcare organizations and systems (5). Since transitions are often challenging for youth with disabilities and their families, innovative organizational initiatives are needed to address issues arising during transitions to adult roles and adult healthcare systems. Accordingly, this article describes the principles and practices of an organization-wide strategy (the Transition Strategy), which was designed to provide evidence-informed services to support children and youth with disabilities at times of transition and to foster meaningful experiences and meaningful lives (6). In this descriptive case study, eight members of the Transition Strategy reflected on their experiences and, guided by Mathieu et al.'s model of factors influencing team effectiveness (7), identified the key team principles and practices that supported the Strategy's functioning, achievements, and outputs.

The context for this work was a Canadian pediatric rehabilitation hospital that is also an academic health science centre, meaning that it promotes the integration of research, clinical, and educational activities to achieve evidence-informed decision making and optimal client care (8). The Transition Strategy was a five-year, donor-funded initiative that aimed to explore, understand, and take action to promote participation and well-being for young people with disabilities. The Strategy adopted an innovative focus on the process of transition, addressing the psychosocial aspects of growing into adulthood through the design of youth and family interventions informed by a humanistic approach and life course perspective (6, 9, 10). Beyond the impact on children, youth, and families, the Strategy aimed to have an impact on the pediatric rehabilitation healthcare system by changing engrained practices.

The vision of the Strategy was to create a sustainable systems-wide model that “re-thinks rehabilitation” by moving from a deficit-oriented to strengths-based approach to transition programming (11–13). From this perspective, “successful transitions” refer to outcomes such as self-efficacy, self-determination, adaptation, and resiliency (14), rather than just a successful medical handover from pediatric to adult services. The Strategy's strategic goals were to improve existing transition services, and design new evidence-informed programs in partnership with children/youth, families, and community organizations, thereby building child, family, and organizational capacity. The objectives were to co-create a common Strategy vision and ensure every client has access to personalized services as well as a transition plan. Given the hospital's status as an academic health science centre, the Strategy had both research and clinical goals. These joint goals reflected an integrated knowledge translation strategy, where program design and delivery are research-informed, and research findings and recommendations are readily translated into clinical practice (8, 15).

Our thinking about the Transition Strategy was guided by complex adaptive systems theory (16), which has been applied to healthcare organizations and systems. Key features of complex adaptive systems include multiple intersecting parts, an evolving, self-organizing nature, and simple rules that encourage creativity and innovation (17, 18).

In the following section, we briefly review current literature on an organizational team model that specifies mechanisms of team functioning, shared leadership, and thriving at work. These key concepts emerged from and informed team members' discussions and reflections on their experiences in the Transition Strategy.

There is a vast literature on effective team functioning and models of teamwork in various fields, including organizational management and health care. Our case study was guided by Mathieu et al.'s (7) model of organizational teams. This model views teams as dynamic, multilevel, complex systems, which aligns with our view of the Strategy as a complex adaptive system. Mathieu et al.'s review of the last decade of research on team effectiveness used an input-mechanism-output model, emphasizing compositional features of teams (i.e., the combination of members' characteristics), structural features (e.g., task scope and complexity, team interdependence), and mediating mechanisms.

Our interest was primarily in mediating mechanisms, defined as team members' affect, behavior, and cognitions (19). Mediating mechanisms include team processes, which refer to the interdependent activities that organize task work to achieve collective goals (7, 20). Other mediating mechanisms are considered to be emergent states, including team cohesion, trust, and team climate (e.g., innovation climate and psychological safety climate). Mathieu et al. (7) have called for more research on teams as fluid entities operating in dynamic situations, and for more research on emergent states.

In Mathieu et al.'s (7) model, shared leadership is both a structural team feature and a mediating mechanism. Shared leadership is a dynamic and emergent phenomenon, where team members share leadership roles and influence (21). Meta-analyses have shown a positive relationship between shared leadership and team performance (21). Relational leadership is one form of shared leadership, referring to a leadership model emphasizing social processes of co-construction, through which team collaboration and change emerge (22). From this perspective, leadership is a relational practice involving co-creation and co-production (23, 24), where there is a focus on communication, caring, and thriving in the workplace. Relational leadership is considered to be essential for dealing with complex issues, such as the design of transition services, where sustainability is a desired outcome along with individual well-being, organizational flourishing, and social change (23).

As discussed by Mathieu et al. (7), effective teams produce tangible outputs/products and provide team members with valuable experience and new learning (7), which can contribute to a sense of thriving in the workplace. “Thriving” refers to feeling energized, valued, and productive through dynamic connections with others in the workplace (25), and is associated with supportive coworker and leadership behavior, and perceived organizational support (26). As well, perceptions of trust, autonomy, meaning, and a positive work environment have been found to be associated with team performance, team members' confidence, work engagement, innovation, and the sustainability of an innovation (27). Positive workplace practices such as respect, support, and a sense of meaning are associated with a positive team climate and a climate of innovation (28). Thus, to summarize, thriving in the workplace is related to the relationships that exist among team members, as well as the support of leadership and a team climate of innovation.

Our research question was: From the perspective of team members, what are the key elements that have contributed to the success of the Strategy? The specific objectives were to describe: (a) guiding principles underlying team functioning and team practices, (b) key enablers of positive team functioning, (c) the nature of effective team practices, and (d) lessons learned. These teamwork principles, enablers, team practices, and lessons learned can provide direction for others on how to co-design a successful innovation and encourage a sense of thriving among team members.

The case under study was the Transition Strategy. We adopted Yin's (29) definition of a case study as an investigation of a contemporary phenomenon within its real life context. Case studies are appropriate when there is an interest in understanding how a complex real-life phenomenon occurs (29–31), particularly when the phenomenon and important contextual variables are not well understood (32), which is the case for the Transition Strategy. We adopted a descriptive case study approach, which involves describing the case, the sources and methods of data collection, and the findings (29). Ethical approval was not required for this study, as it was seen as a quality assessment.

Case study protocols capture the study design, objectives, data sources, and data analysis procedures (29). As shown in our protocol (Figure 1), we took a holistic descriptive case study approach (29), using a single case to describe a unique phenomenon as a unit in a real-life context. As well, the case study was intrinsic—selected on its own merits, given the uniqueness of the Strategy (31). Similar to Di Pelino and colleagues (33), the perspectives of team members constituted the units of analysis (34), and the data consisted of their own direct first-hand experience in implementing the Strategy, as well as feedback they had received from other stakeholders and end users, including parents and youth who were receiving transition services.. Thus, the impressions of team members (the authors of this paper), who had clinical and research roles, were key sources of data (31). The perspective taken was that of the “insider”—an “emic” perspective that reflects an ethnographic approach (35).

As shown in the study protocol (Figure 1), the experiences and insights of team members were captured in minutes and meeting notes. Team members discussed team functioning, core practices, and lessons learned at retreats, monthly clinical-research team meetings, and at the end of project implementation, when the idea arose about writing an article to share our experiences and insights with others. Team members’ understanding of the implementation of the Transition Strategy was also informed by feedback they received from other clinicians implementing the Strategy, parents and youth receiving the services and engaged in advisory roles, and other organizational colleagues and upper management. This feedback came to the team from various discussions, through email, and from quality assurance surveys evaluating new programs.

Case studies routinely use multiple sources of data (29). As shown in Figure 1, although the experiences and insights of the team members were the primary sources of data, we also utilized historical documents (strategic planning documents, operational plans, meeting minutes, and other organizational documents) and tracked output information (from annual accountability reports, the organizational decision support system, and as collected by Strategy research personnel).

The data analysis involved team discussion, critical reflection, and consensus regarding principles, practices, and enablers of the Strategy, as well as lessons learned. We began with a reflective stance, taking an inductive approach to our process. In addition, published literature on team functioning, including Mathieu's model of factors influencing team effectiveness (7), was also used to reflect on enablers and outcomes.

First, the perspectives of team members were used to generate key teamwork principles, enablers of team functioning, team practices, and key learnings. The first author, who is a researcher, developed the initial principles and practices based on key themes that arose repeatedly in discussions held at retreats, team meetings, and meetings held to draft this paper. Other authors wrote sections of text describing features and insights gained from the Strategy stream in which they were most involved. Consensus on key insights was achieved through discussion and reflection over monthly meetings held over a 6-month period, as the article was drafted. As the team generated ideas about thriving and relational leadership, research team members brought relevant literature to the full team for discussion. There were multiple check-ins, as team members read drafts of the article, to ensure the written representation fit their understanding of events and experiences.

Thus, team members critically reflected on their experiences over a period of prolonged engagement, which contributes to the trustworthiness of case study research (30). Triangulation among team and the use of multiple sources of data also serve to enhance credibility (36). Team members can be considered key informants, as they had been involved with the Strategy since its inception, and were able to report on clinical, client/family, and organizational perspectives.

Here we consider the structure and outputs of the Transition Strategy. It is important to provide evidence of successful clinical and research outputs to justify the assertion that the Strategy was indeed an effective innovation.

The Transition Strategy was overseen by a steering committee co-led by a director and a family leader (a parent of a child with a disability). This committee included Strategy team members, family leaders and youth leaders, executive sponsors, community partners from the adult sector, and physicians. Team members were seconded from other roles in the organization based on their expertise, attitudes, drive, and passion, as well as their ability to build community partnerships, collaborate in interprofessional teams, and function as systems-level change agents.

An initial planning retreat led to the formation of five strategy streams for the development of evidence-informed services and the co-discovery of knowledge: Bridging to Adulthood (which builds innovative services and strong community partnerships to support youth transitioning to adult roles and settings), Employment Participation (services designed to promote participation in a range of typical early employment experiences), Starting Early (providing services, information sharing, and connections to support families and their young children in their first and early life transitions), Youth Engagement (providing leadership development and paid employment opportunities for youth with disabilities), and Solution-focused Coaching (a cross-cutting stream informing all the others). A co-design approach, reflecting relational leadership (22), was taken to identify this set of service streams.

The Strategy's annual goals are presented in Figure 2. These goals built upon the knowledge, connections, and practices developed in the preceding years to establish, implement, embed, and then sustain the learning achieved over time. The first year focused on establishing and grounding the Strategy to set the Strategy streams up for success. Years two and three focused on the development of new services built on transition best practices, along with the standardization of tools and procedures to facilitate transitions and evaluate the Strategy's success and impact. The final two years focused on spreading the established practices across and beyond the organization and finding ways to sustain these changes by embedding them in existing systems or proposing new teams, processes, or systems.

Outputs from the Strategy's activities are summarized in Table 1. Partnership/ collaboration activities led to the development of 32 new partnerships with external organizations, along with 23 new capacity building efforts developed in partnership with these organizations. More than 2,325 clients received clinical services, and 18 new or expanded programs were offered, along with 17 types of transition pop-up events (described later). Over 1,800 staff (internal and external) received training in solution-focused coaching and principles of solution-focused communication, and 23 student placements were offered, in addition to workshops and interprofessional education sessions. To date, research and program evaluation outputs included 49 conference presentations and 9 peer-reviewed journal publications. For example, a recent publication concerned pathways to employment for youth with disabilities (37).

Figure 3 visually represents the Strategy's principles, key enablers of positive team functioning, and the team practices considered crucial to team functioning. As shown in this figure, the guiding humanistic principles were respect, support, partnership, and open communication. Team members valued genuine partnerships and collaboration, as well as an environment characterized by trust and respect. These humanistic values align with humanocracy theory, which highlights the importance of human values and principles in the workplace (e.g., the satisfaction of human needs through respect, and having control, support, and the opportunity to engage in challenging work in a safe environment) (38). Humanocracy theory emphasizes that management can be people-centered (38), reflecting the widely adopted philosophy of client/family-centered care in pediatric rehabilitation (39). This correspondence between how one is treated by colleagues and leadership, and how one works with others clinically, has been called “parallel processes” (40).

Figure 3. Guiding principles underlying team functioning and team practices in the Transition Strategy.

Parallel processes refer to features that are common to effective relationships both among managers and staff, and between service providers and clients (40). The common features of all forms of effective relationships include engagement through listening and attending, good communication, empowerment, and strength-building (40). Thus, both client-practitioner and practitioner-organization relationships play a fundamental role in supporting effective service provision (11). The idea of parallel organizational management and clinical processes serves to connect the ideas of team thriving and transformation of services: teams thrive when humanistic principles are adopted, and their thriving contributes to the development of innovative services and offerings.

The team identified two main enablers of positive team functioning, with the first being the relational leadership style of the Strategy director. The director displayed a shared leadership approach, in which leadership roles are shared both formally assigned and informally adopted and encouraged (41). Kurucz et al. (42) has described leadership as a process of social engagement and the formal leader as someone who helps others collectively redefine what is seen as valuable, in light of various challenges. Leader inclusiveness promotes psychological safety and sets the stage for organizational learning (43).

Second, a team climate of innovation, autonomy, and trust, reflecting the broader organizational culture, was viewed as a key enabler of the Strategy's success, as it allowed team members to experience a sense of psychological safety. High quality relationships in the workplace foster psychological safety, which, in turn, is related to learning behaviors in organizations (44). Having shared goals, shared knowledge, and mutual respect foster psychological safety and enable team members to engage in learning from failure (45). Seeing failure as a chance to learn reflects the Strategy's humanistic and strengths-based perspective, and the effective practices adopted by the team.

Here we consider supportive relational practices, human-centered co-design, and solution-focused communication, as shown in Figure 3. Each of these practices reflects a relational leadership model (23) and a team climate characterized by innovation and psychological safety (44). Table 2 provides examples of Transition Strategy models and programs that illustrate each of these practices, along with evidence of their impact.

The hospital has a culture of innovation, which is exemplified and promoted by the senior leadership. Ideas are welcomed, space and time are allowed for the exploration of ideas, and guidance is provided at key moments. In this regard, members of the Strategy experienced many challenges together, such as developing programs that were considered to be unfeasible by the steering committee and other key stakeholders. Some of these instances were viewed, in hindsight, as positive learning experiences.

Team members felt able to engage in lively debate on various issues. Despite opposing views, there was a team atmosphere of respect and a safe working environment in which team members could actively engage through “transparent and respectful conversation”. Free exploration of ideas promoted ongoing innovation. For example, prompted by the COVID-19 pandemic, virtual programming was adopted but, as the pandemic wore on, it became apparent that families felt “virtual fatigue”. Team members adjusted their approach by offering hybrid services (a combined virtual and face-to-face approach), offering workshops on an individual basis, embedding workshop knowledge in other hospital initiatives (e.g., parent support networks, webinars), and sharing content through YouTube videos for families. This example illustrates the ability of team members to identify issues, brainstorm, and innovate in a supportive team environment, and to quickly move from what does not work to better solutions.

Another example, dealing with Project SEARCH, is presented in Table 2. Project SEARCH is an example of an innovative program aligned with the team's mandate. This project is an internationally adopted “best practice” transition-to-work model for students with developmental disabilities, which provides supported work experiences, life skills training, and employment planning (46). Inter-agency collaboration is a key ingredient of the model (47). Annually, up to 75% of Project SEARCH graduates transition to employment (46, 48).

Human-Centered Design (HCD) refers to principles and methods that aim to create innovative solutions tailored to the needs and preferences of the end user (49). HCD has been employed in business organizations to collaboratively solve complex problems and drive service innovation, and has been implemented in a variety of healthcare settings, including disease management and health education (50). To date, HCD has been used to co-design transition support services concerning hospital discharge/transfer of care and to create standardized products/tools (51, 52), but not to design innovative procedures or strategies.

The team embraced HCD principles from IDEO.org (“design thinking”) as a foundation for program development and refinement, as these principles reflected the team's humanistic perspective and relational leadership approach. They used a five-stage HCD process developed by the Stanford d.school (a design thinking institute based at Stanford University): (1) empathizing with and understanding the needs of the users (empathy); (2) constructing a point of view based on the needs and insights of the users (define); (3) brainstorming ideas and generating creative solutions (idea); (4) building a physical representation of the ideas (prototype); and (5) testing ideas for feedback and iteration (test).

Over 100 individuals participated in the co-design process, including stakeholders, service providers, adult sector partners, and youth and families with lived experience. The following HCD principles were adopted: (a) assuming a beginner's mindset (a stance of curiosity), (b) approaching interactions with empathy, (c) co-creating ideas and prototypes (i.e., valuing lived experience and adopting a participatory stance), and (d) engaging in an iterative process, based on recognition that plans need to be flexible with respect to implementation (49). Co-creation is non-linear, iterative, and exciting; it is associated with the belief that solutions are emergent, and that it is alright to “not know”. One specific example, dealing with the creation of a new “Transition Pop-Ups” service delivery model, is presented in Table 2.

SF communication refers to a set of practices based on humanistic principles, where listening and communication are considered central to client-provider and team member relationships, client/family-centered care (39), and effective service delivery (53–55). As a result of the Strategy, training in SF communication took place across the hospital. This training facilitated knowledge and confidence in using SF coaching techniques, and provided a common framework for collaborative solution-finding among teams across the organization (56, 57). A research study indicated that the training led to greater use of strengths-based language in clinical documentation, strengths-based initial assessments and intake interviews, and strengths-based activities in programs for both youth and family members (56, 57). Table 2 provides an example of the use of SF communication in the design of workshops in the Starting Early stream.

Here we discuss two key learnings that reflect the Strategy's humanistic principles and practices. The first was recognizing the value of embracing the inherent messiness of the process involved in designing new services, as well as the inherent messiness of transitions themselves. Embracing this messiness and uncertainty was seen as a key ingredient for healthy and “real” transitions, which, by their very nature, are stressful and highly individual. Given the widespread use of transition guides and skills checklists that are intended to make things “easier” for the healthcare system, it can be argued that the system paradoxically oversimplifies and overcomplicates transitions by not specifically adopting a client-centered perspective, even though this is often espoused. A client-centered perspective requires understanding the highly personal nature of a given youth's transition needs, resources, and supports. The Strategy team struck a balance between systematizing (for equity) and individualizing (for client-centeredness and humanism) by recognizing the real-world messiness of transitions and by listening to clients mindfully and authentically (58), in ways that validate their experiences and foster hope and resiliency.

The second key learning was the value of the Strategy for the organization, clients and families, and team members themselves. On an organizational level, the complement of clinical programs increased due to the efforts of the Strategy. New initiatives were developed in partnership with other service organizations or were adopted in other parts of the hospital, indicating the integration and sustainability of the offered services. One noteworthy example of sustainability and spread is the Solution-focused Coaching stream, which is now embedded hospital-wide and is part of the foundational training for all new staff members. Another example is Project SEARCH, which launched as a transition initiative but is now recognized as a key element of the organization's human resources function.

The value of the Strategy for clients/families can be seen in the “best practice” of supporting families from their first contact with the hospital and throughout their journey to adult systems and adult roles. Transition-related skills are seen as life-long capacities that develop over time within the family and real-world environment (6). Trained family leaders are now available at the hospital to provide information and support regarding strategies, resources, and connections to peer mentors and community agencies, in order to ease the transition journey.

Last, the value for team members was demonstrated by their commitment and ongoing engagement. They had rich learning experiences contributing to their personal and professional growth and sense of thriving in the workplace. By being open to the needs and hopes of clients/families, team members felt they were guided and led by families in essential ways, reflecting the notion of client/family-centered care. Through the integrated knowledge translation approach adopted in the Strategy, team members came to value research more highly and were in an ideal situation to integrate findings into practice in immediate ways.

This article adopted an insider perspective to conduct a case study of the Transition Strategy, a five-year donor funded initiative that viewed transitions from a strength-oriented, systems perspective. The aim was to uncover and describe the key elements contributing to the success of the Strategy in the eyes of team members, who were the authors. Guiding principles underlying the functioning of the team were considered to be respect, support, partnership, and open communication, which align with principles identified in the literature on client/family-centered care (39). Key enablers were the Director's relational leadership style and the team climate, which contributed to a sense of psychological safety, trust, and thriving in the workplace. Several innovative team practices were identified, including supportive relational practices, human-centered co-design, and solution-focused communication. These practices reflect standardized processes generated by the team to enhance their effectiveness. Two key lessons learned were the inherent messiness of the transition process, which therefore requires an individualized approach, and the value of the Strategy for the many stakeholder groups involved with the initiative. Thus, this article provided an in-depth description of the variables that, in the eyes of team members, were responsible for team outputs and service transformation (attesting to the effectiveness of the Strategy), and members' sense of thriving in the workplace.

This article has several limitations. Foremost, aside from personal anecdotes, we do not know the wider impact of the Strategy on clients and families. We did not conduct formal interviews with key informants; rather, we adopted an “insider” perspective where key informants were authors who collaboratively contributed their experiences and insights to this paper. Nonetheless, this article provides other organizations with a vision, starting point (key principles, enablers, and practices), and initial evidence for the utility of an organization-wide strategy with a focus on transforming services for young people with disabilities and their families, which has had the concomitant benefit of facilitating team members' sense of thriving in the workplace. There are important teamwork and leadership implications for others interested in implementing a similar initiative in health care, whether it be about transitions or another important gap concerning needs or issues in service delivery.

This article has implications for both public and private healthcare organizations. The principles, enablers, team practices, and lessons learned can be informative for others seeking to develop a strategic initiative that relies on the effective functioning of a team. In addition, interested organizations can use the Strategy's operational plans for guidance in how to set milestones for an organizational initiative. The annual operational goals were to establish the streams of the Strategy, to implement and evaluate new services and standardize tools and procedures, to spread established practices within the organization and beyond, and to sustain these changes by embedding them in existing or newly created processes or systems. This general process of establish, implement and evaluate, embed, and then sustain can be used by other organizations to develop milestones for similar initiatives that aim to improve service design and delivery on a system-wide level.

From a leadership perspective, one key take-away message is that a coordinated and directed initiative, operating in accordance with a humanistic philosophy, can develop innovative programs and facilitate learning among team members. Health care can be potentially humanized through strategic initiatives that build strong, flexible, interprofessional teams involving multiple stakeholders and partners. A team that thrives interpersonally, psychosocially, and practically can provide an ideal environment for the design of services that provide optimal client care. It should also be noted that the Strategy took place in a relatively ideal organizational situation, with ample funding and positive, ongoing relationships with partnering organizations. From the start, team members had many practical foundations in place, including expertise and established working relationships. As well, they were receptive to a relational model of leadership, and had a strong commitment to the Strategy. Thus, the present findings may not directly translate into other publicly funded organizational environments.

This case study of a workplace team brought together to design, deliver, and evaluate a suite of evidence-informed, transitions-oriented services has shown the value of humanistic principles and relational leadership, as well as supportive relational practices, human-centered co-design practices, and solution-focused communication practices. Our hope is that others can learn from and be inspired by the guiding principles and team practices that embodied the learning experiences of team members and contributed to their sense of thriving in the workplace.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

The first author led the conceptualization and writing of the article. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Gillian King holds the Canada Research Chair in Optimal Care for Children with Disabilities, funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. This chair is supported by matching funds from the Kimel Family Opportunities Fund through the Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital Foundation.

We express our gratitude to all members of the Transition Strategy team, the Holland Bloorview Foundation (including Sandra Hawken, President and CEO), the generous individuals who funded the initiative, Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital (including Julia Hanigsberg, President and CEO, and Diane Savage, Vice-President of Experience and Transformation), and the Transition Strategy steering committee. We also extend thanks to the Ministry of Health and Long Term Care's Business Innovation Office, for their input around human-centered design, and the Rotman NeXus Consulting Group. Many thanks to the clients and families who shared their perspectives and input on needs and services.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Lugasi T, Achille M, Stevenson M. Patients’ perspective on factors that facilitate transition from child-centered to adult-centered health care: a theory integrated metasummary of quantitative and qualitative studies. J Adolesc Health. (2011) 48(5):429–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.10.016

2. Stewart D. Transition to adult services for young people with disabilities: current evidence to guide future research. Dev Med Child Neurol. (2009) 51:169–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2009.03419.x

3. Young NL, Barden WS, Mills WA, Burke TA, Law M, Boydell K. Transition to adult-oriented health care: perspectives of youth and adults with complex physical disabilities. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. (2009) 29(4):345–61. doi: 10.3109/01942630903245994

4. Bethell CD, Newacheck PW, Fine A, Strickland BB, Antonelli RC, Wilhelm CL, et al. Optimizing health and health care systems for children with special health care needs using the life course perspective. Matern Child Health J. (2014) 18(2):467–77. doi: 10.1007/s10995-013-1371-1

5. Heath G, Farre A, Shaw K. Parenting a child with chronic illness as they transition into adulthood: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of parents’ experiences. Patient Educ Couns. (2017) 100(1):76–92. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.08.011

6. King G, Imms C, Stewart D, Freeman M, Nguyen T. A transactional framework for pediatric rehabilitation: shifting the focus to situated contexts, transactional processes, and adaptive developmental outcomes. Disabil Rehabil. (2018) 40(15):1829–41. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2017.1309583

7. Mathieu JE, Gallagher PT, Domingo MA, Klock EA. Embracing complexity: reviewing the past decade of team effectiveness research. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav. (2019) 6:17–46. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012218-015106

8. King G, Thomson N, Rothstein MG, Kingsnorth S, Parker K. Integrating research, clinical care, and education in academic health science centers: an organizational model of collaborative workplace learning. J Health Organ Manag. (2016) 30(7):1140–60. doi: 10.1108/JHOM-11-2015-0177

9. Halfon N, Larson K, Lu M, Tullis E, Russ S. Lifecourse health development: past, present and future. Matern Child Health J. (2014) 18(2):344–65. doi: 10.1007/s10995-013-1346-2

10. Sameroff A. A unified theory of development: a dialectic integration of nature and nurture. Child Dev. (2010) 81(1):6–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01378.x

11. King G. A relational goal-oriented model of optimal service delivery to children and families. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. (2009) 29(4):384–408. doi: 10.3109/01942630903222118

12. Bertolino B, O'Hanlon WH. Collaborative, competency-based counseling and therapy. Boston MASS: Allyn and Bacon (2002).

13. Baldwin P, King G, Evans J, McDougall S, Tucker MA, Servais M. Solution-focused coaching in pediatric rehabilitation: an integrated model for practice. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. (2013) 33(4):467–83. doi: 10.3109/01942638.2013.784718

14. King G, Seko Y, Chiarello LA, Thompson L, Hartman L. Building blocks of resiliency: a transactional framework to guide research, service design, and practice in pediatric rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. (2020) 42(7):1031–40. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2018.1515266

15. Anaby D, Khetani M, Piskur B, van der Holst M, Bedell G, Schakel F, et al. Towards a paradigm shift in pediatric rehabilitation: accelerating the uptake of evidence on participation into routine clinical practice. Disabil Rehabil. (2022) 44(9):1746–57. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2021.1903102

16. Zimmerman B, Lindberg C, Plsek PE. Edgeware: Insights from complexity science for health care leaders. Irving, TX: VHA (1998).

17. Anderson RA, McDaniel RR Jr. Managing health care organizations: where professionalism meets complexity science. Health Care Manage Rev. (2000) 25(1):83–92. doi: 10.1097/00004010-200001000-00010

18. Chaffee MW, McNeill MM. A model of nursing as a complex adaptive system. Nurs Outlook. (2007) 55(5):232–41. e3. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2007.04.003

19. Salas E, Kozlowski SW, Chen G. A century of progress in industrial and organizational psychology: discoveries and the next century. J Appl Psychol. (2017) 102(3):589–98. doi: 10.1037/apl0000206

20. Marks MA, Mathieu JE, Zaccaro SJ. A temporally based framework and taxonomy of team processes. Academy of Management Review. (2001) 26(3):356–76. doi: 10.2307/259182

21. D’Innocenzo L, Mathieu JE, Kukenberger MR. A meta-analysis of different forms of shared leadership–team performance relations. J Manage. (2016) 42(7):1964–91. doi: 10.1177/0149206314525205

22. Uhl-Bien M. Relational leadership theory: exploring the social processes of leadership and organizing. Leadersh Q. (2006) 17:654–76. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2006.10.007

23. Nicholson J, Kurucz E. Relational leadership for sustainability: building an ethical framework from the moral theory of “ethics of care”. J Bus Ethics. (2019) 156(1):25–43. doi: 10.1007/s10551-017-3593-4

24. Fletcher JK. The relational practice of leadership. In: Uhl-Bien M, Ospina SM, editors. Advancing relational leadership: a dialogue among perspectives charlotte. NC: Information Age Publishing Inc. (2012). p. 83–106.

25. Spreitzer G, Sutcliffe K, Dutton J, Sonenshein S, Grant AM. A socially embedded model of thriving at work. Organization Science. (2005) 16(5):537–49. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1050.0153

26. Kleine AK, Rudolph CW, Zacher H. Thriving at work: a meta-analysis. J Organ Behav. (2019) 40(9-10):973–99. doi: 10.1002/job.2375

27. Geue PE. Positive practices in the workplace: impact on team climate, work engagement, and task performance. J Appl Behav Sci. (2018) 54(3):272–301. doi: 10.1177/0021886318773459

28. Cameron K, Mora C, Leutscher T, Calarco M. Effects of positive practices on organizational effectiveness. J Appl Behav Sci. (2011) 47(3):266–308. doi: 10.1177/0021886310395514

30. Baxter P, Jack S. Qualitative case study methodology: study design and implementation for novice researchers. Qual Rep. (2008) 13(4):544–59. doi: 10.46743/2160-3715/2008.1573

32. Ebneyamini S, Sadeghi Moghadam MR. Toward developing a framework for conducting case study research. Int J Qual Methods. (2018) 17(1):1–11. doi: 10.1177/1609406918817954

33. Di Pelino S, Lamarche L, Carr T, Datta J, Gaber J, Oliver D, et al. Lessons learned through two phases of developing and implementing a technology supporting integrated care: case study. JMIR Formative Research. (2022) 6(4):e34899. doi: 10.2196/34899

34. VanWynsberghe R, Khan S. Redefining case study. Int J Qual Methods. (2007) 6(2):80–94. doi: 10.1177/160940690700600208

35. Pozniak K, King G. Bringing an ethnographic sensibility to pediatric rehabiliation: contributions, and potential. In: Hayre CM, Muller D, Hackett P, editors. Rehabilitation in practice: ethnographic perspectives. London, UK: Springer Nature (2022). p. 97–115.

36. Patton MQ. Qualitative evaluation and research methods. 2nd ed Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications (1990).

37. Bowman LR, McDougall C, D’Alessandro D, Campbell J, Curran CJ. The creation and implementation of an employment participation pathway for youth with disabilities. Disabil Rehabil. (2022) doi: 10.1080/09638288.2022.2140846. [Epub ahead of print]

38. Aldridge MJ, Macy HJ, Walz T. Beyond management: humanizing the administrative process. Iowa City, IA: University of Iowa (1982).

39. Rosenbaum P, King S, Law M, King G, Evans J. Family-centred service: a conceptual framework and research review. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. (1998) 18(1):1–20. doi: 10.1300/J006v18n01_01

40. Moore T. Parallel processes: common features of effective parenting, human services, management and government. Adelaide, Australia: Early Childhood Intervention Australia (2006).

41. Pearce C, Conger J. Shared leadership: reframing the hows and whys of leadership. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage (2003).

42. Kurucz EC, Colbert BA, Wheeler D. Reconstructing value: leadership skills for a sustainable world. Toronto: University of Toronto Press (2013).

43. Nembhard IM, Edmondson AC. Psychological safety: a foundation for speaking up, collaboration, and experimentation in organizations. In: Cameron KS, Spreitzer GM, editors. The Oxford handbook of positive organizational scholarship. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press (2012). p. 490–503.

44. Carmeli A, Brueller D, Dutton JE. Learning behaviours in the workplace: the role of high-quality interpersonal relationships and psychological safety. Syst Res Behav Sci. (2009) 26(1):81–98. doi: 10.1002/sres.932

45. Carmeli A, Gittell JH. High-quality relationships, psychological safety, and learning from failures in work organizations. J Organ Behav. (2009) 30(6):709–29. doi: 10.1002/job.565

46. Christensen J, Hetherington S, Daston M, Riehle E. Longitudinal outcomes of project SEARCH in upstate New York. J Vocat Rehabil. (2015) 42(3):247–55. doi: 10.3233/JVR-150746

47. Rutkowski S, Daston M, Van Kuiken D, Riehle E. Project SEARCH: a demand-side model of high school transition. J Vocat Rehabil. (2006) 25(2):85–96.

48. Wehman P, Schall C, McDonough J, Sima A, Brooke A, Ham W, et al. Competitive employment for transition-aged youth with significant impact from autism: a multi-site randomized clinical trial. J Autism Dev Disord. (2020) 50:1882–97. doi: 10.1007/s10803-019-03940-2

49. Innovation Design Engineering Organization. The field guide to human centered design 2015 [Available from: https://www.ideo.com/post/design-kit].

50. Bazzano AN, Martin J, Hicks E, Faughnan M, Murphy L. Human-centred design in global health: a scoping review of applications and contexts. PloS one. (2017) 12(11):e0186744. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186744

51. Hopkins IG, Dunn K, Bourgeois F, Rogers J, Chiang VW. From development to implementation—a smartphone and email-based discharge follow-up program for pediatric patients after hospital discharge. Healthcare. (2016) 4(2):109–15. doi: 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2015.11.003

52. Pascual KJ, Vlasova E, Lockett KJ, Richardson J, Yochelson M. Evaluating the impact of personalized stroke management tool kits on patient experience and stroke recovery. J Patient Exp. (2018) 5(4):244–9. doi: 10.1177/2374373517750416

53. McKenna L, Brown T, Oliaro L, Williams B, Williams A. Listening in health care. In: Worthington DL, Bodie GD, editors. The handbook of listening. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons (2020). p. 373–83.

54. Paxino J, Denniston C, Woodward-Kron R, Molloy E. Communication in interprofessional rehabilitation teams: a scoping review. Disabil Rehabil. (2022) 44(13):3252–69. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2020.1836271

55. King G. Central yet overlooked: engaged and person-centred listening in rehabilitation and healthcare conversations. Disabil Rehabil. (2021) doi: 10.1080/09638288.2021.1982026. [Epub ahead of print]

56. Seko Y, King G, Keenan S, Maxwell J, Oh A, Curran CJ. Impact of solution-focused coaching training on pediatric rehabilitation specialists: a longitudinal evaluation study. J Interprof Care. (2020) 34(4):481–92. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2019.1685477

Keywords: parallel principles, relational practice, co-design, solution-focused communication, humanism, teamwork, shared leadership

Citation: King G, Bowman LR, Curran CJ, Oh A, Thompson L, McDougall C, Menna-Dack D and Howson-Strong L (2022) A case study of a strategic initiative in pediatric rehabilitation transition services: An insiders' perspective on team principles and practices. Front. Rehabilit. Sci. 3:999973. doi: 10.3389/fresc.2022.999973

Received: 21 July 2022; Accepted: 21 November 2022;

Published: 9 December 2022.

Edited by:

Christine Mac Donell, CARF International, United States© 2022 King, Bowman, Curran, Oh, Thompson, McDougall, Menna-Dack and Howson-Strong. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gillian King Z2tpbmcyN0B1d28uY2E=

Specialty Section: This article was submitted to Strengthening Rehabilitation in Health Systems, a section of the journal Frontiers in Rehabilitation Sciences

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.