- The Rural Institute for Inclusive Communities, University of Montana, Missoula, MT, United States

It is very difficult to find and keep workers to provide home-based care for disabled people, especially in rural places. There is a tension between the rights of disabled people and the rights of home-based personal care workers. In this brief review, we explore the intersections of historical and social forces that shaped federal-level policies for both disability rights and the rights of personal care workers, as well as the current state of the policies. This paper provides a narrow focus on federal policies relevant to both groups, while also considering how the urbancentric nature of advocacy and policymaking has failed to address important issues experienced by rural people. In addition to briefly reviewing relevant federal policies, we also explore sources of support and resistance and how urbanormativity, ableism, and sexism intersect to influence how the needs of people with disabilities and their personal care workers are conceptualized and addressed. We conclude with recommendations for how to better address the needs of rural people with disabilities using home-based personal care services and the workers who provide them.

Introduction

Personal Assistance Services, as part of Home and Community-Based Services funded through Medicaid, are critical for disabled people1 to live, work, and recreate in their homes and communities (1). As part of these services, personal care attendants (PCAs—also referred to as personal care aides, personal attendants, and personal assistance service workers) come to disabled peoples' homes to assist them with tasks of daily living such as getting in and out of bed, toileting, meal preparation, housekeeping, transportation, and running errands. Distinct from home healthcare workers, who provide skilled nursing care, PCAs provide more basic care and, in most cases, are not required to have formal training. These services are clearly vital for the wellbeing of people with disabilities. Despite personal assistance services being among the fastest-growing employment sectors (2), these low-wage, low-status jobs are difficult to fill and maintain with qualified people, especially in rural places (3). Personal assistance care in rural areas is burdensome both for disabled people and PCA workers: many people with self-care disabilities live in places where personal care attendants are in short supply (4) and the unpaid commuting “windshield time” required in rural areas limits worker availability and adds mileage costs (5). PCA positions rarely come with benefits and often require workers to combine several clients to reach full-time status and earnings (6). Many of the positions are also physically demanding and PCAs experience high rates of injury and disability (7). Finally, like many care work positions, the vast majority of these jobs are occupied by women, women of color, and immigrants (4), who often face more exploitation than other workers. Despite the intertwined relationships that exist between the disabled people needing services and the workers providing them, advocates for these groups have not historically worked together to fight for protections and rights for both groups. This paper is a brief introduction to how the movements for disability rights and workers' rights evolved over the twentieth century, with a narrow focus on relevant federal policies. We recognize that these programs are executed and managed by states and that state implementation is heterogeneous. Given the brief nature of this focused mini-review, we are unable to speak to these between-state differences or the conflicts that have arisen due to the complexities of implementing federal policies at the state level, sometimes without additional federal support.

The disagreement regarding what policies are needed is embedded in the seemingly-competing goals of protecting both the “choice and control” (8) of disabled people and the labor policies needed to protect and promote workers' rights. On the side of protecting disabled people's autonomy, rural disability advocates recognized their unique needs were not always included in the dominant, urban-based movement for disability rights. This led to the formation of the Association of Programs for Rural Independent Living (9). However, there has been little organized support for rural PCAs. The goal of concurrently promoting and protecting both parties has historically been impeded by a belief among some disability rights advocates that if workers' rights and statuses are elevated, the autonomy of, and access to care for, people with disabilities will be demoted (10). To further understand the challenges of elevating and protecting both disabled people and workers, especially those living and working in rural areas, this paper (1) provides an overview of intersecting policies implemented since the 1930s, (2) considers the sources of supports and resistance in both movements, and (3) highlights the intersections of urbanormativity, ableism, and sexism in shaping policies and practices. This paper ends with a discussion of the current emerging opportunities in addressing the needs of both rural consumers and workers.

Changing Policies Since the 1930s

While advocacy for disability rights has been formally happening for more than 150 years, advocacy at the national level for supports specific to being able to receive the care and services needed to stay in one's community and home have only come about more recently (11). The earliest policies focused on “protecting” non-disabled citizens from being exposed to people with disabilities (e.g., ugly laws). Many of these policies led to the hiding away of disabled individuals and kept them out of the labor market, with the exception of venues like “freak shows.” People with disabilities have been incredibly marginalized throughout history, including being primary targets of the Eugenics movement. It is estimated that 60,000 disabled people in the United States were subject to forced sterilization during this period; worldwide, the number is over a half of a million (12, 13). Slowly, US policies have evolved to support greater integration of disabled people into society. However, policy nuances have resulted in less progress for disabled people in rural places. For example, employment provisions within the Americans with Disabilities Act (14) applied only to businesses that employed more than 15 people. Given employers in rural areas tend to be small businesses with fewer than 15 employees, rural disabled people benefit less from this policy than their urban counterparts (15).

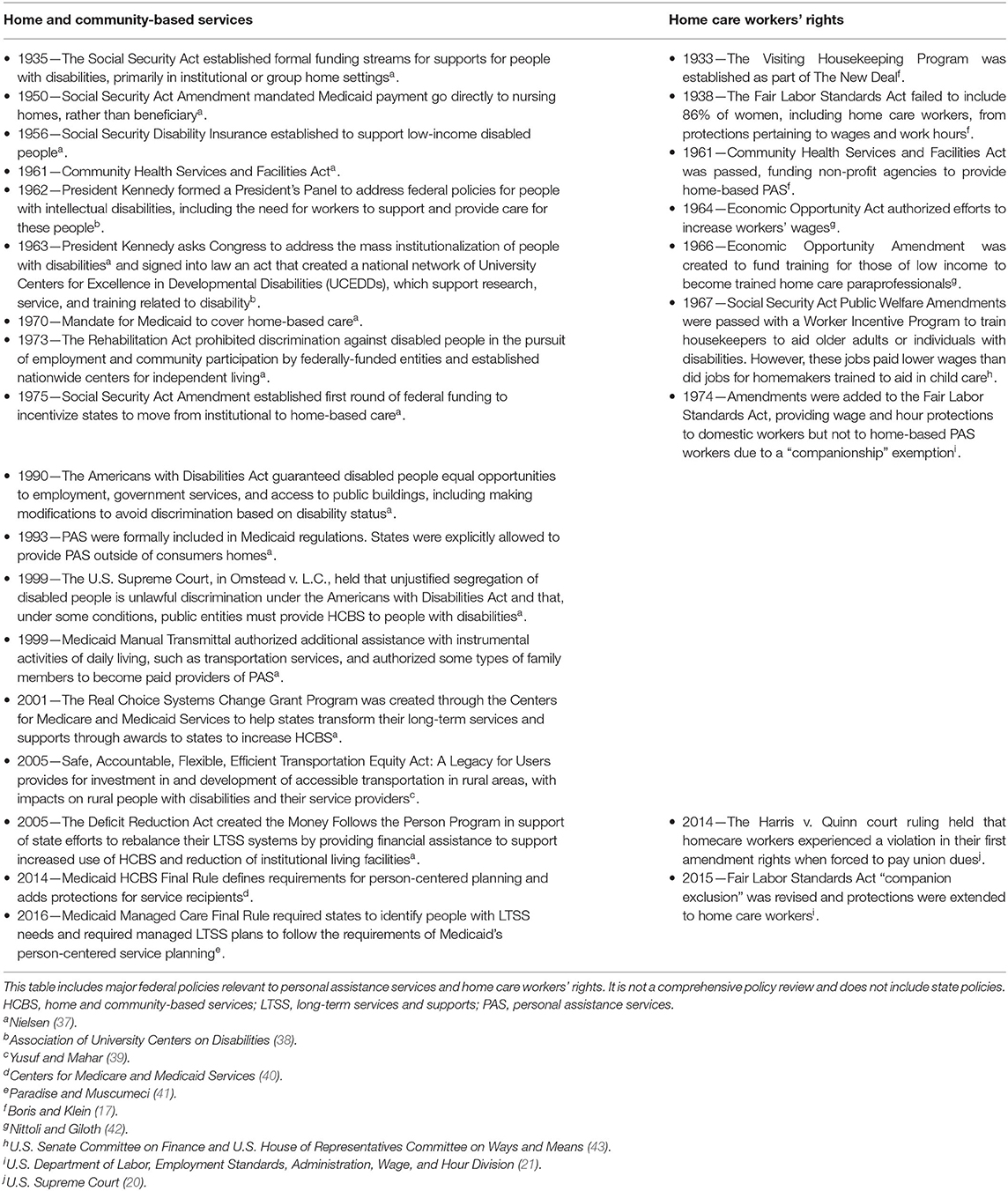

Table 1 is a very brief overview of some of the key federal-policy-related events that impacted both the evolution of policies related to personal assistance services and home care workers' rights. For both people with disabilities and PCAs, the federal government's response to the Great Depression was a turning point, bringing some of the inequities and challenges faced by both groups to light. The Social Security Act (16) established formal federal funding (distributed to the states) for supporting people with disabilities, primarily in institutional or group living situations (10). Similarly, under the Roosevelt administration, the Visiting Housekeeping Program was established as part of The New Deal (17). This program put women, including many women of color, to work in other people's homes. Training centers for these programs were primarily located in urban centers, likely drawing labor-seeking women from the countryside. Despite the important gains made in passing the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 to protect workers from the most harsh and unsafe working conditions and to limit the standard work week, 86% of working women, including PCAs, were not included in the protections (17).

Table 1. Evolution of federal policies related to personal assistance services and home care workers' rights.

After a period of national focus on war efforts following the New Deal policies, changes for disability rights picked up again in the 1950s, but policy implementation impacting the work of PCAs stayed fairly mute until the 1974 amendment to the Fair Labor Standards Act. This amendment explicitly excluded domestic workers (including PCAs) from protections, designating their work “companionship services.” During the 1950s, disability rights advocates gained ground in securing funding for basic living needs via Social Security Disability Insurance in 1956. Later advocacy by disability rights activists against institutionalization, and in favor of home-based services, resulted in amendments to the Social Security Act and new mandates throughout the 1960s and 1970s (see Table 1). During this time, however, there was little policy formation around the rights and working conditions of PCAs. Additionally, implementation of policies related to home-based services was slow, in part due to the growing power and influence of the nursing home industry (10). Though not perfect, formal programming and some fiscal supports were established during the 1960s and 1970s to meet federal mandates that Medicaid funding be used to support disabled people in their homes, rather than only in institutions. This would not become the Home and Community-Based Services program until 1983 when Congress added section 1915(c) to the Social Security Act (17), but these pieces of federal legislation and related policies provided important foundational support for today's systems.

From the 1990s to present, policy changes have led to substantial advances in conceptualizing disability and associated civil rights for disabled people (see Table 1), such as the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, having Personal Assistance Services formally included in Medicaid Regulations in 1993 (17), the Olmstead decision by the Supreme Court in 1999 (18), and the development and evaluation of the Money Follows the Person Program of 2005 (19). Policies in support of workers' rights have expanded to include First Amendment Rights protections for PCAs (20) and the 2015 removal of the 1974 companionship exception from the Fair Labor Standards Act (21). To follow is a brief discussion of some of the people, organizations, and industries involved in supporting and resisting changes for disabled people and PCAs.

Sources of Support and Resistance

On the surface, home-based services for people with disabilities received public support. For instance, social reformers Reverend Louis Dwight and Dorothea Dix were among the first advocates to publicly criticize the deplorable living conditions of institutionalized individuals in the mid to late 1800s (22). As public consciousness about dignity of life for disabled people was elevated, it seems very few believed disabled people should be living in such conditions. It is notable that these institutions were largely operated in rural locations in the United States and hidden away from urban centers. These institutions provided jobs and economic support in many rural communities. However, this commodification of care for disabled residents attracted for-profit companies into the industry (15). The movement to deinstitutionalize disabled people did not really take hold until the 1950s, following the foundational policies established in the amendments to the Social Security Act (23). Societal events leading up to these changes included the widespread effects of polio outbreaks in 1916 and between 1949 and 1952 leading to higher rates of disability (24) and the presidential election of Franklin D. Roosevelt (who used a wheelchair), which helped shift the ways in which Americans thought about physical and mobility-related disabilities. Although deinstitutionalization of disabled people eradicated many residential institutions, nursing homes—which are also disproportionately concentrated in rural places—have in some ways taken their places (15).

The nursing home industry, with strong lobbying abilities, resisted home-based services (10) and won most of the policy battles, garnering Congressional support in amendments to the Social Security Act until the 1970s when it was mandated that nursing home-level care for people with disabilities on Medicaid must be covered in-home, if a disabled person chooses in-home care. However, the systems to accommodate these choices would be long in the making. The nursing home industry also played a role in the continued exclusion of home-based PCAs from federally protected workers' rights, arguing they could not afford to adhere to the protections for their institutional-based workers who were also excluded (17). Instead, PCAs in the US were subject to unjust working conditions such not being able to receive phone calls or spend time with friends if they lived with the person for whom they provided services and unclear limits on how many hours they were allowed or required to work (25). Additionally, international workers' rights were not protected to ensure a pathway to achieving immigration status, and they were instead faced with having to comply with their employer or risk deportation (25).

Home care worker unions such as the Service Employees International Union grew exponentially during the last 20 years. This led to many key protections for unionized workers in select states (26). However, supporters of home care workers' rights have experienced setbacks to their efforts to improve working conditions and wages in recent years. In 2018, the U.S. Supreme Court prohibited home care workers unions from charging non-members fees. The following year, in 2019, a Medicaid policy change barred home healthcare aides working for Medicaid-funded facilities and agencies from having union dues automatically deducted from their pay checks (27). The inability to more easily pay union dues has led to less union membership, fewer resources, and less collective bargaining power. Perhaps due to the incredible harsh and negative impacts of worker shortages during the COVID-19 pandemic (28), there has been recent momentum in disability rights advocates joining forces with workers' rights advocates to fight for better compensation and work conditions.

Intersections of Urbanormativity, Ableism, and Sexism

With more awareness and support, the Independent Living Movement took hold in the mid-twentieth century and was intimately tied to other civil rights movements. With a mantra of “nothing about us without us” to acknowledge the long paternalistic history of making decisions about disabled bodies for people with disabilities rather than with them (26), disability rights advocates continue to fight for justice and equity today.

Like many other social justice events, disability advocacy has largely taken place in urban areas [e.g., (28)]. With the exception of work done by the fairly small organization, the Association of Programs for Rural Independent Living, the Independent Living Movement has been fairly urbancentric with most activity happening on university campuses and in cities (8), making it difficult for rural disabled people to participate.

Given the urban focus of the Independent Living Movement, it is perhaps unsurprising rural-specific issues related to receiving personal assistance services have neither been sufficiently addressed nor researched thoroughly. Furthermore, in rural places, lack of affordable and accessible housing and limited availability of PCAs has led to unjust institutionalization of disabled people in nursing homes (15). Next, we briefly explore how ableism and sexism have played a role in the evolution of these policies influencing rural care work and those who need services.

From the beginning, there has been resistance to financially supporting people with disabilities at adequate levels. Some of this resistance is embedded in a cultural belief in rugged independence and self-sufficiency, which is more prevalent among rural citizens (11). Our country has a long history of having a weak safety net that is slow to kick in and quick to be pulled back (29). The evolving medical field and technology provided decision makers with new tools to determine who was “deserving” and “undeserving” of community living and services, as evidenced by the strict and extremely complex protocols established to determine eligibility for Social Security Disability Insurance (10). All of this, in addition to employment-based health benefits, contributes to keeping workers tied to the labor market.

The Visiting Housekeeping Program served as a catalyst for propelling PCAs toward a more formalized and professionalized occupation. However, it was met with resistance from the Southern textiles and manufacturing industry leaders because they argued that as they were getting back on their feet, they could not compete with subsidized wages provided by the government (17). This intersected with the restriction that only one person per family could be supported by Worker Progress Administration programs (which included the Visiting Housekeeping Program), which favored men (17). Finally, because care in the home was seen as less valuable than other labor, it was difficult for workers' rights advocates to gain any momentum toward better compensation and work conditions. This particular belief also helped fuel the resistance to workers' rights among people with disabilities who desired high degrees of autonomy and control in organizing their daily lives and services (30).

In terms of workers' rights, women in families with individuals with disabilities were historically and continue to be expected to provide family care for free, saving the government billions of dollars (31). In fact, currently 80% of care provided to people with disabilities and older adults is unpaid. Despite the majority of women being in the workforce by the late 1970s, family caregiving continues to be a social expectation, placing incredible burdens on many women (32). Even after the advent of Home and Community-Based Services, many states did not allow spouses or parents to be paid for providing care (33). These types of rules made it extremely hard for rural people needing services to find workers in their communities (4). However, today there is more momentum for creating better supports than has been seen for many, many years.

Discussion

This paper highlights the complex social justice issues that arise when trying to elevate the needs of different groups that, at first, appear to have competing goals. This becomes even more complicated when we turn our attention toward the implications in rural places. The gains made by people with disabilities to have services that enable them to live, work, and recreate in community necessitate the commodification of other people's labor. In some cases, this means the autonomy of disabled people appears to be in conflict with the autonomy of workers, a conflict that is subsumed by a system that does not adequately support either group. For rural people with disabilities, current policies do not address the additional burden of rurality, including a lack of local workers (especially when spouses or parents are excluded from being paid caregivers), additional costs related to the lack of accessible, public transportation (34). For the workers who provide these essential services, workers' rights advocacy also has not addressed the additional burdens of “windshield time,” car maintenance, and the costs of providing care in less accessible homes and communities with fewer services, for lower wages compared to what they can earn providing care in urban places (35).

Based on this review and the growing interest in finding ways to better support both people with disabilities and PCAs, we recommend organizations doing research in home-based services—such as the AARP Public Policy Institute—consider adding rural components to their very useful Long-Term Services and Supports Scorecard analyses (36). Topics to consider include adjustment of wages to better compensate rural workers, better compensation for vehicles and mileage, and incentivizing individuals in rural places to become PCAs. It is also recommended these organizations employ staff knowledgeable in the unique history of, and issues faced by, rural disabled people and service providers. We also recommend including rural voices of people with disabilities and PCAs in relevant policy discussions and decisions. Finally, in advocacy work, we encourage social justice advocates to consider making room at the table for rural people impacted by these issues in ways that do not exacerbate the burden of participation faced by many rural people (e.g., driving long distances to participate in advocacy events).

Author Contributions

Idea for the paper was by RS. Writing, critical review of the paper, suggested edits, revisions, and responses to reviewers were distributed evenly between RS, KS, and GM. Final edits were done by KS and GM. All authors contributed to the article and approved the resubmitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the Research and Training Center on Disability in Rural Communities (RTC:Rural) under a grant from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR; grant number 90RTCP0002), which was a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

Author Disclaimer

The research does not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, or HHS and one should not assume endorsement by the federal government.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Billy Altom for his consultation on rural disability history and Ashley Tamez Trautman for her feedback on an earlier version of this paper.

Footnotes

1. ^The terms disabled people (identity first language) and people with disabilities (person first language) are used interchangeably to reflect the current preferences of advocates in the disability rights field.

References

1. Kaye HS, Harrington C. Long-term services and supports in the community: Toward a research agenda. Disabil Health J. (2015) 8:3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2014.09.003

2. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Home Health and Personal Care Aides: Occupational Outlook Handbook. (2021). Available online at: https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/home-health-aides-and-personal-care-aides.htm (accessed September 22, 2021).

3. Siconolfi D, Shih RA, Friedman EM, Kotzias VI, Ahluwalia SC, Phillips JL, et al. Rural-urban disparities in access to home- and community-based services and supports: stakeholder perspectives from 14 states. J Am Med Direct Assoc. (2019) 20:503–8.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.01.120

4. Greiman L, Sage R, Chapman S, Wagner L, Bates T, Lissau A. Personal Care Assistance in Rural America. Missoula, MT; San Francisco, CA: University of Montana, Rural Institute University of California San Francisco, Health Workforce Research Center (2021). Available online at: https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/836efdf9752d4f1c8d101181d7735c04 (accessed June 26, 2021).

5. Strong Towns. The Bottom-Up Revolution Is… Helping Rural Residents with Disabilities to Thrive. Strong Towns (2022). Available online at: https://www.strongtowns.org/journal/2022/1/6/billy-altom-bottom-up (accessed February 9, 2022).

6. Kim JJ. Personal care aides as household employees and independent contractors: Estimating the size and job characteristics of the workforce. Innovat Aging. (2021) 6:igab049. doi: 10.1093/geroni/igab049

7. Jang Y, Lee AA, Zadrozny M, Bae S-H, Kim MT, Marti NC. Determinants of job satisfaction and turnover intent in home health workers: the role of job demands and resources. J Appl Gerontol. (2017) 36:56–70. doi: 10.1177/0733464815586059

8. DeJong G. Independent living: from social movement to analytic paradigm. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. (1979) 60:435–46.

9. Association of Programs for Rural Independent Living. Association of Programs for Rural Independent Living (n.d.). Available online at: https://www.april-rural.org/index.php/about-us (accessed February 13, 2021).

10. Iezzoni LI, Gallopyn N, Scales K. Historical mismatch between home-based care policies and laws governing home care workers. Health Affairs. (2019) 38:973–80A–E. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05494

11. Taylor S. Beasts of Burden: Animal and Disability Liberation. New York, NY: The New Press (2017). p. 272.

12. Roy A, Roy A, Roy M. The human rights of women with intellectual disability. J R Soc Med. (2012) 105:384–9. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2012.110303

13. Tilley E, Walmsley J, Earle S, Atkinson D. ‘The silence is roaring': sterilization, reproductive rights and women with intellectual disabilities. Disabil Soc. (2012) 27:413–26. doi: 10.1080/09687599.2012.654991

14. U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Fact Sheet: Disability Discrimination. (1997). Available online at: https://www.eeoc.gov/laws/guidance/fact-sheet-disability-discrimination (accessed April 8, 2022).

15. Seekins T, Ravesloot C, Riggles B, Enders A, Arnold N, Ipsen C, et al. The Future of Disability and Rehabilitation in Rural Communities. Missoula, MT: RTC: Rural, Rural Institute, University of Montana (Foundation Paper No. 3) (2011). p. 22.

16. The Social Security Act. (1935). Available online at: https://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=false&doc=68&page=transcript# (accessed December 22, 2021).

17. Boris E, Klein J. Caring for America: Home Health Workers in the Shadow of the Welfare State. Oxford University Press (2015). p. 318.

18. Olmstead v. L. C. Vol. 527, U.S. (1999). p. 581. Available online at: https://www.law.cornell.edu/supct/html/98-536.ZS.html (accessed July 17, 2018).

19. Money Follows the Person | Medicaid. Available online at: https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/long-term-services-supports/money-follows-person/index.html (accessed February 11, 2022).

20. U.S. Supreme Court. Harris et al. v. Quinn, Governor of Illinois, et al. U.S. Supreme Court (2014). Available online at: https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/13pdf/11-681_j426.PDFhttps://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/13pdf/11-681_j426.PDF (accessed February 11, 2022).

21. U.S. Department of Labor, Employment Standards, Administration, Wage, and Hour Division. Application of the Fair Labor Standards Act to Domestic Service. National Archives Federal Register (2001). Available online at: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2001/01/19/01-1590/application-of-the-fair-labor-standards-act-to-domestic-service (accessed February 11, 2022).

22. Minnesota's Governor's Council on Developmental Disabilities. Parallels in Time: A History of Developmental Disabilities. (2021). Available online at: https://mn.gov/mnddc/parallels/index.html (accessed December 8, 2021).

23. Torrey EF. Out of the Shadows: Confronting America's Mental Illness Crisis. Revised edition. New York, NY; Weinheim: Wiley (1998). p. 257.

24. Tucker J. No Lockdowns: The Terrifying Polio Pandemic of 1949-52 – AIER. Barrington, MA: American Institute for Economic Research (2020). Available online at: https://www.aier.org/article/no-lockdowns-the-terrifying-polio-pandemic-of-1949-52/ (accessed September 18, 2021).

25. Hondagneu-Sotelo P. Families on the frontier: from braceros in the fields to Braceras in the home. In: Suarez-Orozoco MM, Suarez-Orozoco C, Qin-Hilliard D, editors. The New Immigration: An Interdisciplinary Reader. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis (2005). p. 167–77.

26. Charlton JI. Nothing about Us without Us : Disability Oppression Empowerment. Quest Ebook Central - Reader. Berkley, CA: University of California Press; ProQuest Ebook Central (1998). Available online at: https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/msoumt/detail.action?docID=224299 (accessed February 14, 2020). doi: 10.1525/9780520925441

27. Quinton S. Unions, States Confront Trump Home Care Worker Rule. The PEW Institute (2019). Available online at: https://pew.org/2JDfNUB (accessed November 4, 2021).

28. Erkulwater JL. How the nation's largest minority became white: race politics and the disability rights movement, 1970–1980. J Policy History. (2018) 30:367–99. doi: 10.1017/S0898030618000143

30. Bagenstos SR. Disability rights and labor: Is this conflict really necessary? Indiana Law J. (2016) 92:277–98. Available online at: https://heinonline.org/hol-cgi-bin/get_pdf.cgi?handle=hein.journals/indana92§ion=9 (accessed December 7, 2021).

31. Chari AV, Engberg J, Ray K, Mehrotra A. The opportunity costs of informal elder-care in the United States: new estimates from the American Time Use Survey. Health Serv Res. (2014) 50:871–82. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12238

32. Hochschild AR. The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling, Updated with a New Preface. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press (2012). p. 335. doi: 10.1525/9780520951853

33. AARP the Commonwealth Fund the SCAN Foundation. Advancing Action, 2020: A State Scorecard on Long-Term Services and SUPPORTS for Older Adults, People with Physical Disabilities, and Family Caregivers. (2020). Available online at: http://www.longtermscorecard.org/2020-scorecard/preface (accessed December 8, 2021).

34. Sage R, Greiman L, Lissau A, Wagner L, Toivanen-Atilla K, Chapman S. “It's a Human Connection…”: Paid Caregiving in Rural America. ArcGIS StoryMaps (2021). Available online at: https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/7f914cf2023c491bb780bae845253162 (accessed March 19, 2022).

35. Sage RA. Qualitative perceptions of opportunity and job qualities in rural health care work. Online J Rural Nurs Health Care. (2016) 16:154–94. doi: 10.14574/ojrnhc.v16i1.382

36. Reinhard S, Houser A, Ujvari K, Gualtieri C, Harrell R, Lingamfelter P. Long-Term Services Supports State Scorecard 2020 Edition. Washington, DC: AARP Public Policy Institute (2020). Available online at: http://www.longtermscorecard.org/~/media/Microsite/Files/2020/LTSS%202020%20Reference%20Edition%20PDF%20923.pdf (accessed March 17, 2022).

38. Association of University Centers on Disabilities. AUCD History. (2018). Retrieved from: https://www.aucd.org/emergingleaders/Learn/About-AUCD (accessed February 18, 2022).

39. Yusuf J-E, Mahar K. Safe, accountable, flexible, efficient transportation equity act: a legacy for users. In: Encyclopedia of Transportation: Social Science and Policy. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. (2014). Available online at: http://sk.sagepub.com/reference/encyclopedia-of-transportation/n422.xml (accessed February 10, 2022).

40. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Fact Sheet: Home Community Based Services. (2014). Available online at: https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/home-and-community-based-services (accessed February 11, 2022).

41. Paradise J, Muscumeci M. CMS's Final Rule on Medicaid Managed Care: A Summary of Major Provisions. The Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured (2016). p. 20.

42. Nittoli JM, Giloth RP. New Careers Revisited: Paraprofessional Job Creation for Low-Income Communities. Social Policy (1998). Available online at: link.gale.com/apps/doc/A20575584/AONE?u=mtlib_1_1195&sid=googleScholar&xid=8b510b4e (accessed February 11, 2022).

43. U.S. Senate Committee on Finance and U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Ways and Means. Summary of Social Security Amendments of 1967. U.S. Government Printing Office (1967). Available online at: https://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/PrtSSSummary2.pdf (accessed February 11, 2022).

Keywords: disability, home care workers, policy, home-based services, community-based services

Citation: Sage R, Standley K and Mashinchi GM (2022) Intersections of Personal Assistance Services for Rural Disabled People and Home Care Workers' Rights. Front. Rehabilit. Sci. 3:876038. doi: 10.3389/fresc.2022.876038

Received: 15 February 2022; Accepted: 31 March 2022;

Published: 25 April 2022.

Edited by:

Jean P. Hall, University of Kansas, United StatesReviewed by:

Joseph Caldwell, Brandeis University, United StatesCopyright © 2022 Sage, Standley and Mashinchi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rayna Sage, cmF5bmEuc2FnZUB1bW9udGFuYS5lZHU=

Rayna Sage

Rayna Sage Krys Standley

Krys Standley Genna M. Mashinchi

Genna M. Mashinchi