- 1Suicide Prevention, Orygen, Parkville, VIC, Australia

- 2Centre for Youth Mental Health, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, Australia

- 3Violet Vines Marshman Research Centre, La Trobe Rural Health School, La Trobe University, Flora Hill, VIC, Australia

Introduction: Concerns exist about the relationship between social media and youth self-harm and suicide. Study aims were to examine the extent to which young people and suicide prevention professionals agreed on: (1) the utility of actions that social media companies currently take in response to self-harm and suicide-related content; and (2) further steps that the social media industry and policymakers could take to improve online safety.

Methods: This was a cross-sectional survey study nested within a larger Delphi expert consensus study. A systematic search of peer-reviewed and grey literature and roundtables with social media companies, policymakers, and young people informed the questionnaire development. Two expert panels were developed to participate in the overarching Delphi study, one of young people and one of suicide prevention experts; of them 43 young people and 23 professionals participated in the current study. The proportion of participants “strongly agreeing”, “somewhat agreeing”, “neither agreeing nor disagreeing”, and “somewhat disagreeing” or “strongly disagreeing” for each item were calculated; items that achieved =>80% of agreement from both panels were strongly endorsed.

Results: There was limited consensus across the two groups regarding the utility of the safety strategies currently employed by companies. However, both groups largely agreed that self-harm and suicide-related content should be restricted. Both groups also agreed that companies should have clear policies covering content promoting self-harm or suicide, graphic depictions of self-harm or suicide, and games, pacts and hoaxes. There was moderate agreement that companies should use artificial intelligence to send resources to users at risk. Just over half of professionals and just under half of young people agreed that social media companies should be regulated by government. There was strong support for governments to require schools to educate students on safe online communication. There was also strong support for international collaboration to better coordinate efforts.

Discussion: Study findings reflect the complexity associated with trying to minimise the risks of communicating online about self-harm or suicide whilst capitalising on the benefits. However, a clear message was the need for better collaboration between policymakers and the social media industry and between government and its international counterparts

Introduction

Suicide is the fourth leading cause of death among young people worldwide (1), and the leading cause of death in many countries including Australia (2–4). Self-harm (defined here as an act of deliberate self-injury or self-poisoning, irrespective of motive or suicidal intent) (5) is also prevalent among young people (6, 7) and is a key risk factor for future suicide (8).

Although the reasons for self-harm and suicide are complex, there is concern about the role social media plays in introducing or exacerbating psychological distress among young people (9, 10). There are also fears regarding the potential for certain types of content, for example, graphic imagery and livestreams of self-harm and suicidal acts, to cause distress and lead to imitative behaviour among others (11). However, social media is popular among young people and our work has identified several potential benefits (12). For example, it allows young people to feel a sense of community, to seek help for themselves and to help others, and to grieve for people who have died by suicide. Additional benefits include its accessibility, non-stigmatizing nature, and capacity to deliver highly personalized content directly to a user's feed (12, 13). While this work highlights the potential for social media to be a useful tool for suicide prevention, we need to identify ways to minimize the risks associated with social media without simultaneously diminishing the benefits.

Potential levers for creating and maintaining a safe and healthy online environment for users include educational approaches, whereby users are provided with the information to keep themselves and their peers safe online; policy approaches, whereby governments develop and implement legislation to support online safety; and industry self-regulation, whereby the social media industry takes responsibility for maximising safety on its platforms (14).

Progress is being made in each of these areas. For example, the #chatsafe program, comprising evidence-informed guidelines plus social media content, is an example of an educational approach that has been shown to better equip young people to communicate safely online about suicide (12, 15, 16). Although important, many would argue that the onus should not be placed on young people alone to keep themselves safe online. Therefore, additional approaches are required.

Governments in several countries have taken steps towards developing policies designed to regulate the social media industry. For example, the United Kingdom (UK) (17), Australia (18), and the United States of America (USA) (19, 20) have all introduced legislation designed to regulate the social media industry. Though these are broad-brush approaches, they provide guidance to platforms on operating safely and impose fines and penalties on companies that do not comply. However, the rapid evolution of social media, together with the lengthy process of passing legislation, means we cannot rely on legislation alone. Further, restrictions imposed in one country does not necessarily prevent distressing information spreading among young people elsewhere.

Finally, the social media industry has also taken steps to improve user safety on their platforms. For example, many platforms have appointed safety advisory boards and developed safety functions that help users control the type of content they view and interact with (14). However, little is known about either the acceptability or perceived utility of these measures among young people. To the best of our knowledge, only one study, conducted by The Samaritans in the UK has examined this. This study was a cross sectional survey of 5,294 people living in the UK (87% of whom had a history of self-harm) and found that more than 75% of the sample had viewed self-harm content online before the age of 14 years (11). Of those who encountered self-harm and suicide-related content, 83% reported that they had not intentionally searched for it; many reported that it worsened their mood, and over three quarters reported that they self-harmed in similar, or a more severe way, after exposure to the content. Despite mixed findings related to the efficacy of trigger warnings (21), study participants reported that a specific content warning (as opposed to a generic one) would have been helpful. Overall, participants were largely in favour of having more control over the content that they see, such as the ability to mute certain types of content or block other users.

Each of these approaches are in their infancy, and it is unlikely that one approach alone will be sufficient to create and maintain safe online environments. Further, questions remain as to how helpful young people and suicide prevention professionals consider existing approaches to be, and what additional steps they believe could be taken by the social media industry and policymakers.

Aims

The aim of this study was to examine what young people and suicide prevention professionals believed that the social media industry and policymakers should do to create and maintain safer online environments in relation to communication about self-harm and suicide. An additional aim was to seek the views of participants on some of the actions that social media companies are already taking in response to self-harm and suicide-related content.

Methods

Study design

This was a cross sectional survey. It was nested within a larger Delphi expert consensus study (reported elsewhere) that was conducted to update and expand the original #chatsafe guidelines (16) and involved: (1) a systematic search of peer-reviewed and grey literature; (2) roundtables with social media companies, policymakers, and young people; (3) questionnaire development; (4) expert panel formation; (5) data collection and analysis; and (6) guideline development.

The study received approval from The University of Melbourne Human Research Ethics Committee (ID: 22728).

Systematic search of the literature

Sources published in the peer-reviewed or grey literature were eligible for inclusion if they focused on: (1) self-harm or suicide; (2) social media or other online environments; and (3) the nature of online communication about self-harm or suicide. Peer-reviewed articles had to be written in English, French, Spanish, or Russian (i.e., the languages spoken by the research team) to be included. Grey literature had to be written in English.

For the peer-reviewed literature search, CINAHL, EMBASE, ERIC, Medline, PsycINFO, and Scopus were searched for studies published between 1 January 2000 and 4 November 2021. The grey literature search involved three components. First, the following databases were searched: APAIS-Health, Australian Policy Online, and ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global (PQDT). Second, the first ten pages (i.e., up to the first 100 results) of google.com, google.com.au, google.ca, google.co.nz, and google.co.uk were searched. Finally, the “help centers” or equivalent of Ask FM, Clubhouse, Deviant Art, Discord, Facebook, Instagram, Pinterest, Quora, Snapchat, TikTok, Tumblr, Twitch, Twitter, WhatsApp, and YouTube were searched and screened. The full search strategy has been published elsewhere (22).

Round table consultations

Six roundtable consultations were conducted between June and August 2022: three with social media companies (n = 7), two with policymakers from the Australian federal government (n = 14), and one with young people (n = 7). Discussions focused on: (1) the challenges associated with online communication about self-harm and suicide; (2) what more (if anything) social media platforms and policymakers could be doing to keep young people safe online; (3) the extent to which online safety is the responsibility of government, platforms and/or individuals. Each session was audio recorded, transcribed and potential action items were extracted for inclusion in the questionnaire—see below.

Questionnaire development

Statements extracted from 149 peer-reviewed articles, 52 grey literature sources, and the roundtables formed the basis of the current questionnaire. Participants were informed that these items were designed to identify what actions participants thought that the social media industry and policymakers could be doing to improve online safety.

There were 158 survey non-forced response items in this section of the survey (See Supplementary File 1). Examples include: “Social media companies should provide clear policies on safe and unsafe online behaviour in relation to suicide / self-harm”; “Government should create a rating system of social media companies against a set of safety standards”. Participants were asked to rate the extent to which they agreed with items on a 5-point Likert scale, with 1 being strongly disagree and 5 being strongly agree. Participants were also asked to indicate how social media companies should manage graphic or potentially unsafe content. For these 10-items participants responded using one of the following five response options: “remove”, “shadow ban”, “allow users to view content but disable interactions”, “restrict”, and “unsure”.

Participants and recruitment

Two expert panels were recruited. One comprised suicide prevention professionals identified via the literature search and one comprised young people recruited via social media advertisements.

Professionals were invited to take part via email and were eligible for inclusion if they were: (1) aged at least 18 years; (2) an expert on self-harm or suicide (e.g., research, teach, or treat self-harm or suicide; and had published research on self-harm or suicide and social media, or contributed to guidelines on communication about self-harm or suicide); and (3) were proficient in English. Young people were recruited via Instagram advertisements and were eligible for inclusion if they: (1) were aged between 15 and 25 years inclusive; (2) lived in Australia; (3) were proficient in English; and (4) had seen, communicated about, or wanted to communicate online about self-harm or suicide.

Data analysis

Data were analysed in Microsoft Excel. The proportion of participants “strongly agreeing”, “somewhat agreeing”, “neither agreeing nor disagreeing”, and “somewhat disagreeing” or “strongly disagreeing” for each item were calculated for both professionals and young people separately. We used a similar approach to the Delphi consensus study in the current analysis. Specifically, items that achieved =>80% of agreement from both panels (either “somewhat” or “strongly”) were considered to be strongly endorsed and steps that should be taken, items that received an agreement level (either “somewhat” or “strongly”) between 70 and 79.99% were considered moderately endorsed and steps worth considering. If an item received agreement (either “somewhat” or “strongly”) from less than 70% of either panel, it was considered to have low endorsement and to unnecessary at this time. In cases where there was large discrepancy in endorsement (e.g., 50% of one group and 70% of the other group agreed with the item) the lowest score was taken as the level of endorsement. This approach allowed us to identify key actions that were considered a priority for social media companies and policymakers by both professionals and young people. For the 10 items that asked participants to rate how social media companies should manage graphic or potentially unsafe content, the proportion of agreement for each of the five response options (e.g., “remove”, “shadow ban”, “allow users to view content but disable interactions”, “restrict”, and “unsure”) was reported and any major discrepancies between panels were noted in the results.

Results

Sample characteristics

Forty-three young people responded to this survey. The mean age of youth participants was 21.30 years (SD = 2.54, range = 17–25). Seventy-two per cent identified as female, 20.9% as transgender or gender diverse, and 7.0% as male. Just under one half identified as LGBTIQA + (48.8%), and almost one-quarter came from a culturally or linguistically diverse background (23.3%). Most had their own lived experience of self-harm or suicide (81.4%), and/or had supported someone who was self-harming or suicidal (65.1%); 16.3% were bereaved by suicide.

Twenty-three professionals responded to the survey. They included PhD students (17.4%), postdoctoral researchers or lecturers (26.1%), professorial staff (43.5%); 8.7% were in roles such as research advisors or funders. One participant did not report their role. Almost one fifth also worked as clinicians (17.4%). They resided in a variety of countries including Australia (26.1%), UK (17.39%), USA (13.0%), and 4.4% each from Austria, Canada, China, Estonia, France, Germany, Ghana, Hong Kong, New Zealand, South Africa, and Spain.

Key findings

The results presented below are broken down as follows: (1) actions that the social media industry should take in terms of enhancing safety policies, responding to self-harm and suicide-related content, and staffing; and (2) actions that policymakers should take, including better industry regulation, educational programs, and future collaboration and investment.

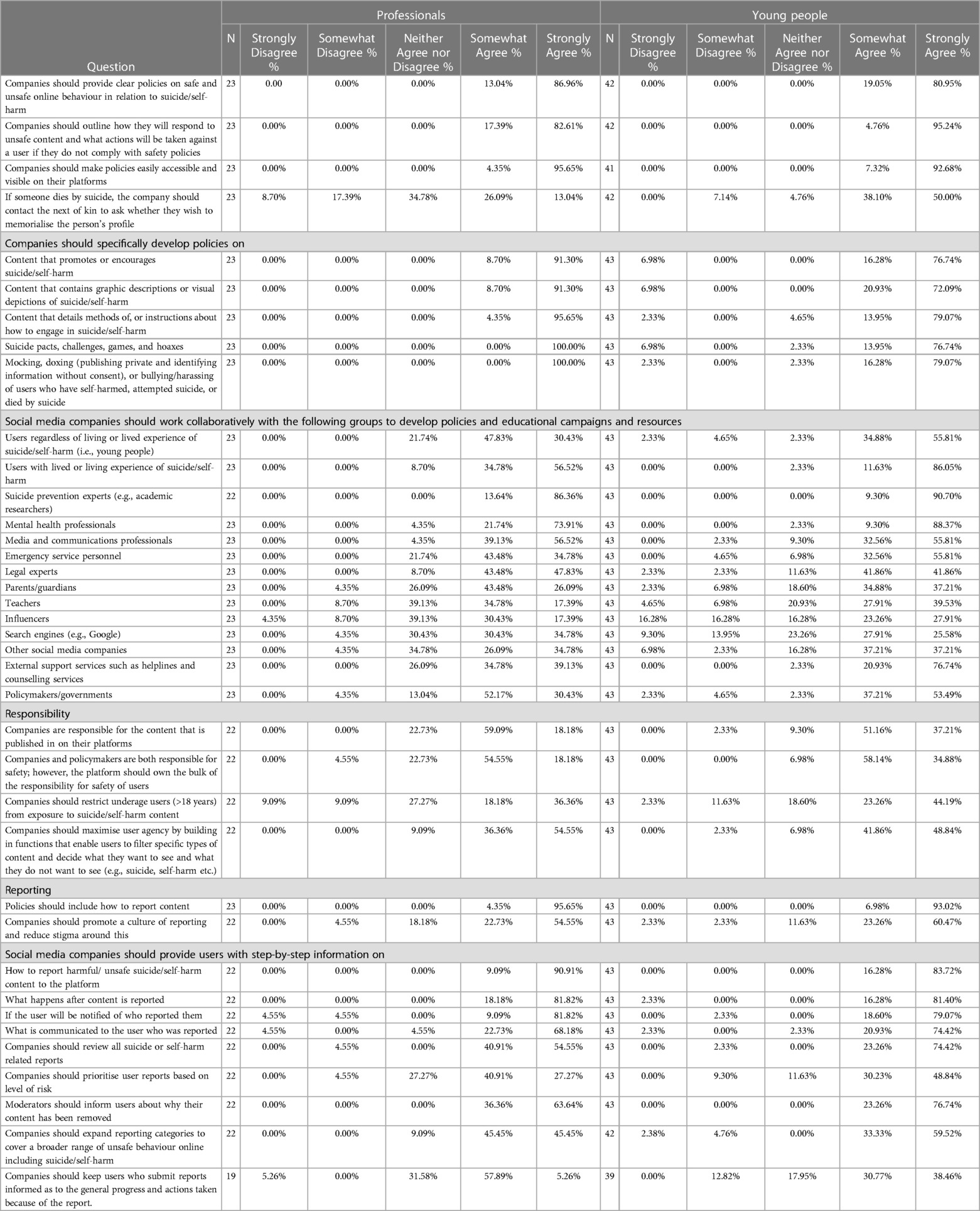

Actions the social media industry should take policies, responsibility and reporting

Table 1 presents the views of both young people and suicide prevention professionals with regards to the development and implementation of safety policies, where responsibility for online safety lies, and reporting. Both professionals and young people agreed that companies should have clear and accessible policies that cover content promoting or encouraging self-harm or suicide, graphic depictions of self-harm or suicide, and games, pacts and hoaxes. Participants agreed that policies should be developed in collaboration with platform users (both with and without lived experience), suicide prevention and mental health professionals, legal and communications professionals, other industry professionals and policymakers. There was also strong agreement that social media companies hold responsibility for the content posted on their platforms and that they should maximise user agency by enabling users to control the type of content that they see.

In terms of reporting, participants believed companies should promote a culture of reporting content that violates their policies, should review all self-harm or suicide related reports, and if content is removed they should explain to users why this is the case. There was strong agreement that companies should expand reporting categories to cover a broader range of content.

Managing and responding to self-harm and suicide-related content

Table 2 presents the views of participants with regards to the ways in which platforms should manage and respond to self-harm and suicide-related content.

There was moderate agreement that companies should use artificial intelligence (AI) to send helpful resources to users at risk, though less agreement on whether companies should use AI to intervene where risk was detected. There was strong agreement that companies should not allow self-harm or suicide content to appear in people's “suggested content”. There was also strong agreement that all companies should have a clearly accessible safety centre that contains evidence-based information and links to support services. Professionals and young people agreed that companies should restrict access to content that could be harmful to others and that membership of a platform should be paused if individuals repeatedly breach safety policies.

There was strong agreement that social media companies should provide content warnings for potentially harmful self-harm or suicide-related content and for content with self-harm or suicide-related hashtags. These should include information about why the content warning exists plus links to resources. There was weaker agreement with how livestreams of self-harm or suicidal acts should be managed, although >50% of both groups agreed that the stream should be removed by platforms immediately. There was strong agreement that platforms should send resources and links to support services to both the person posting the livestream and viewers, and the livestream should be reported to emergency services. However, there was low endorsement of platforms contacting law enforcement more broadly if a user appeared to be at risk of suicide. (37% of young people and 18% of professionals). Finally, there was strong agreement that platforms should actively promote helpful content such as messages that encourage help-seeking plus stories of hope and recovery.

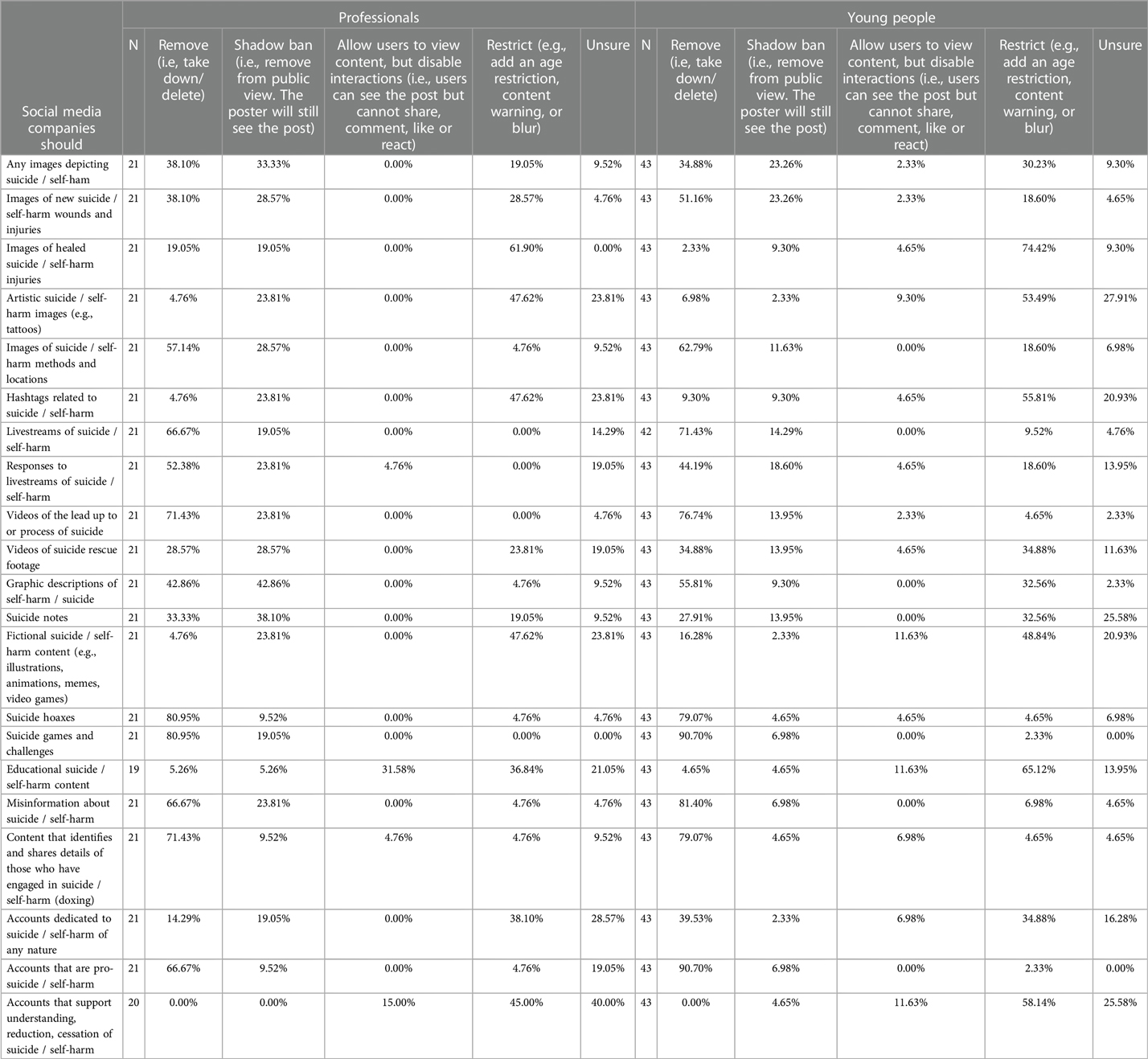

Table 3 presents participants’ views on some of the safety strategies currently employed by social media companies. There was less consensus across the two groups for most of the items listed in Table 3, however for the most part the two groups did agree that access to the types of content listed should be restricted in some way. That said, >50% of both groups agreed that images of self-harm or suicide methods and locations should be removed, >60% agreed that livestreams should be removed and >70% agreed that videos depicting preparations for suicide should be removed. Around 80% of both groups agreed that content relating to suicide hoaxes, games and challenges should be removed. For several types of content, almost a quarter of participants stated they were unsure what social media companies should do.

Staffing and training

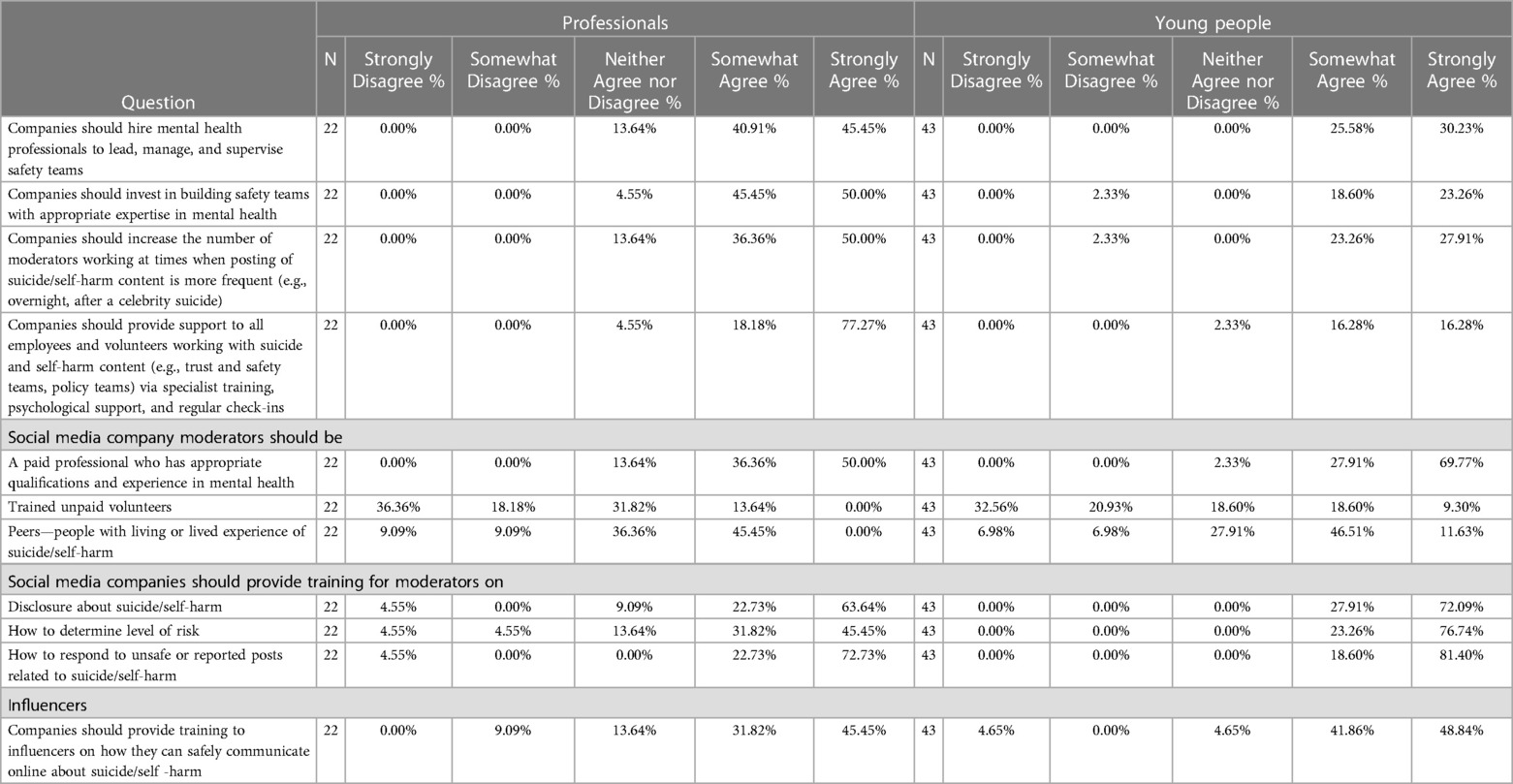

There was strong agreement that social media companies should have safety teams and paid content moderators with appropriate qualifications and experience. Moderators (and other staff who encounter self-harm and suicide-related content) should receive training and ongoing support. Companies should also provide training to influencers or content creators, on how to communicate safely about self-harm and suicide. See Table 4.

Actions policymakers should take

Regulation and legislation

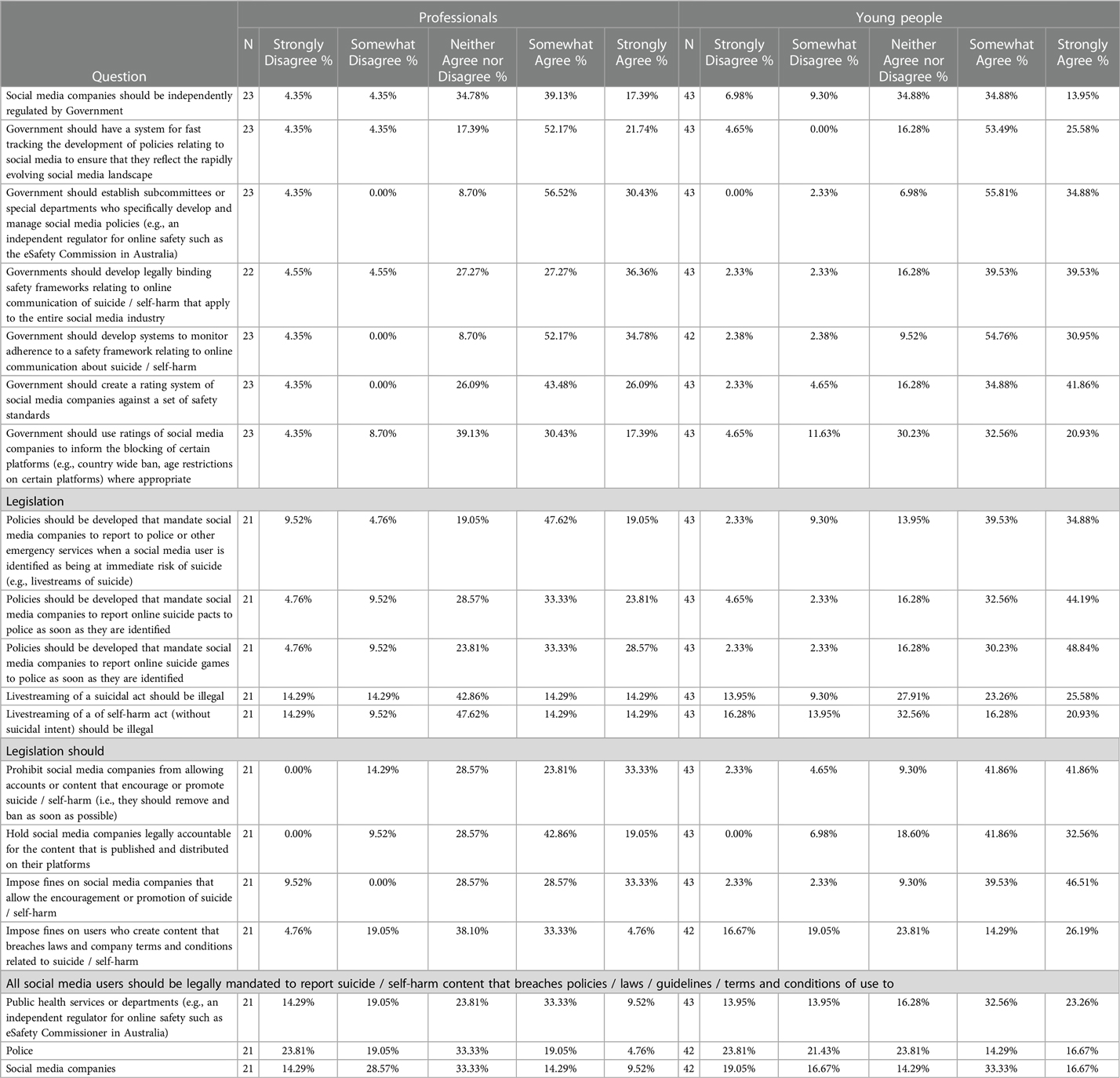

Just over half of professionals (56.52%) and just under half of young people (48.84%) agreed that social media companies should be independently regulated by government. However, there was recognition that policy development would need to be fast tracked to keep up with the rapidly evolving social media landscape. There was strong agreement regarding the need for a special department, or regulator, to manage social media policies and that systems should be developed to appropriately monitor adherence to them.

There was lower agreement between participants regarding the type of legislation that should be developed. However, young people strongly believed that legislation should be developed prohibiting social media companies from allowing accounts that encourage or promote self-harm or suicide and that fines should be imposed for breaching this policy. They moderately agreed that social media companies should be held legally accountable for content published on their platforms. See Table 5.

Education and awareness

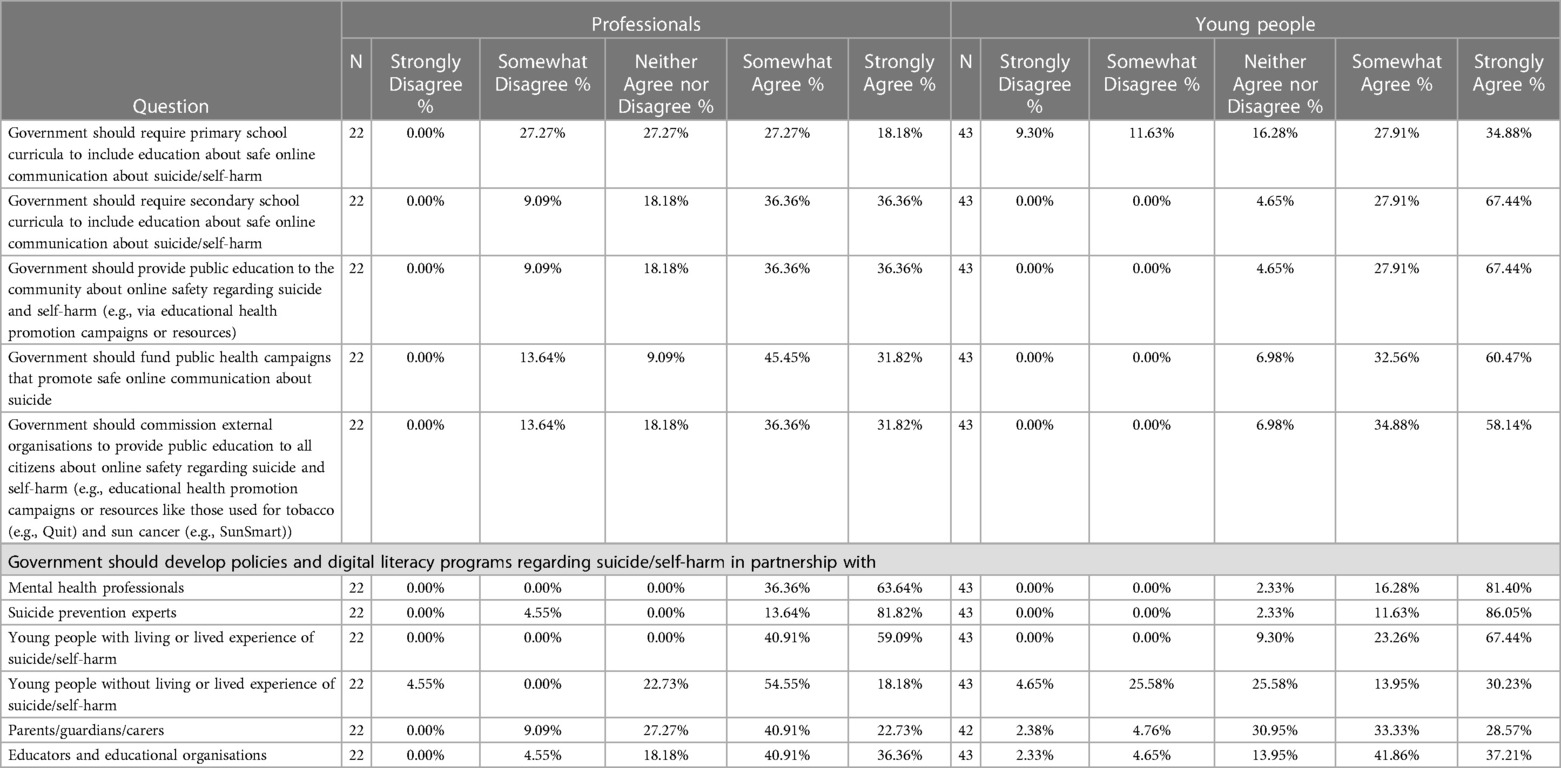

Table 6 shows that there was strong support for governments to require secondary schools to provide education regarding safe online communication about self-harm and suicide. There was also strong support for public education campaigns. Both groups agreed that educational programs and campaigns should be developed in partnership with young people with lived experience, mental health and suicide prevention experts, and educators.

Collaboration and investment

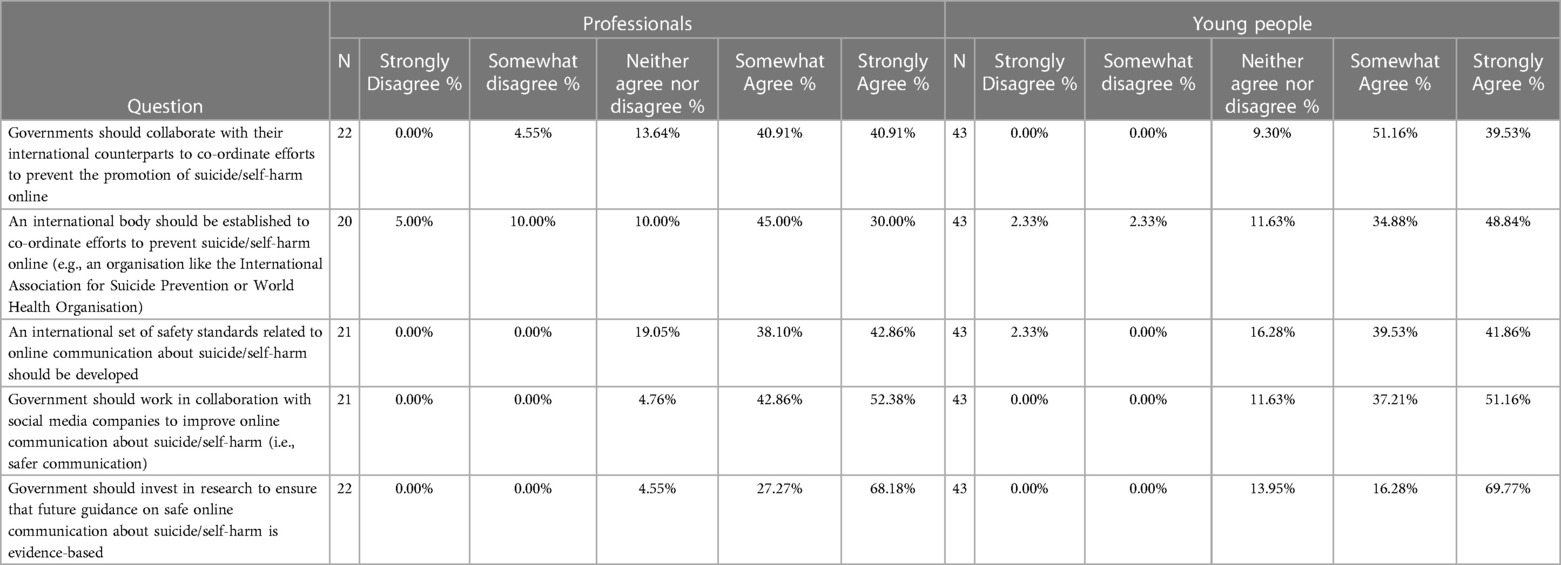

Table 7 presents the views of participants on the ways they believe government should collaborate with others and future investment. Both young people and professionals agreed that governments should collaborate with their international counterparts to coordinate efforts. They agreed that an international body should be established, that an international set of safety standards be developed, and that governments should work in collaboration with the social media industry to improve online safety.

Discussion

This paper reports on a cross sectional survey that examined the views of young people and suicide prevention professionals regarding the steps that both social media companies and policymakers should be taking to improve the safety of online communication about self-harm and suicide. It also sought the views of both groups of participants on some of the actions that social media companies are already taking in response to self-harm and suicide-related content.

Key findings and implications

Social media companies

There was strong agreement among participants about some of the more basic measures platforms should be taking to promote safety. For example, by developing and implementing robust safety policies covering self-harm and suicide, moderating potentially harmful content, and hosting safety centres. Similarly, there was strong agreement that safety and moderation teams should be led and staffed by people with appropriate training and experience and that all staff who encounter self-harm and suicide-related content receive appropriate training and support. Although most of the major companies already employ many of these strategies there seemed to be the view that policies should be broadened, made more visible, and their implementation could be strengthened. Further, not only are many of the strategies implemented platform-specific, most have not been tested empirically for either acceptability or effectiveness. Future research should consider ways of testing content-moderation functions to ensure that they meet the needs of social media users, and consider developmental and other differences among users.

There was agreement that platforms should provide content warnings for potentially harmful content including content containing self-harm or suicide-related hashtags. As noted above, there is mixed evidence regarding the efficacy of content warnings (11, 12) and in the overarching Delphi study (23) consensus was not reached about their inclusion. However, in the study conducted by the Samaritans (11), and the current study, participants believed these would be useful, particularly if they were specific to the subject matter and contained links to helpful resources. Again, meeting the needs of social media users is important here given that participants in this study felt that trigger warnings would be helpful despite the evidence suggesting that they can at times be harmful (21). There is a need for future research to test different features and delivery of trigger warnings, specific to self-harm and suicide, that help us understand when, for whom, and in what context, these safety features are helpful.

There was less endorsement regarding how platforms should manage livestreams of self-harm or suicide. All participants agreed that livestreams should be reported to emergency services and that both posters and viewers should be sent links to helpful resources. But there was no consensus regarding how long the livestream should be allowed to run and whether or not comments should be permitted. Managing livestreams appropriately is challenging. For example, allowing the livestream to transmit for a period of time and permitting others to comment, provides an opportunity for intervention. However, it also runs the risk of viewers being exposed to a live suicide act, which would be distressing and could potentially increase the risk of others engaging in similar acts (24, 25). It also violates most platforms' policies.

There was strong agreement that platforms should use their AI capabilities to promote helpful content such as psychoeducation about self-harm and suicide, plus messaging that encourages help-seeking and stories of hope and recovery. Just as certain types of self-harm and suicide-related content can be harmful to viewers, it is well established that stories of hope and recovery can be helpful (26, 27) and there was clear support for platforms to use their capabilities to promote this. There was moderate agreement that companies should use AI to proactively detect users at risk and send them helpful information and resources. However, risk can fluctuate rapidly and there is debate in the literature regarding the accuracy of risk prediction tools in general (28, 29). There is also concern regarding some of the ways the platforms use their algorithms to direct certain types of (potentially harmful) content to (often vulnerable) users (30–32) and respondents in the current study agreed that AI should not be used for this purpose. Therefore, using AI to detect and respond to people who may be at risk will likely present ethical challenges for companies. However, studies have demonstrated that risk can be detected, with some accuracy, using content posted on platforms such as Twitter and Reddit (33, 34) and participants in the current study appeared to be relatively comfortable with the idea of companies using this type of technology if it helps keeps young people safe. Therefore, perhaps using their AI in this way could be a next step for platforms providing no harm is done in the process.

There was moderate agreement that companies provide training to influencers on how to communicate safely about self-harm and suicide to their followers. Influencers have grown in number and popularity over recent years, with many having significant numbers of (often young) followers. While some companies do provide broad mental health training to some of their content creators (35), it is important that this extends to self-harm and suicide. The new #chatsafe guidelines provide some guidance for influencers (22), and whilst this is a step in the right direction, uptake by influencers is likely to be limited. As a result, it is also important that the companies themselves support the influencers on their platforms to communicate safely online about self-harm and suicide.

There was disagreement between the groups of participants on some items. A notable example was reporting users at risk of suicide to law enforcement. Indeed, some companies have policies that state that if a user is clearly at risk of suicide, law enforcement will be contacted (36). The fact that participants did not support this (except for livestream events as discussed above) may reflect the fact that in some countries suicide remains illegal (37) and that in others, first responders may be unlikely to respond in either a timely or compassionate manner (38). It may also be seen as somewhat heavy handed and a possible breach of privacy. However, it does mean that social media companies need to think carefully about how they respond to users who are expressing acute risk on their platforms and that tailored, country-specific responses are needed.

Policymakers

There was strong agreement for some measures such as the need for specific departments to develop policies relating to social media and to monitor their implementation by the companies. Arguably, in Australia, we are leading the way in this regard with the creation of the e-Safety Commission which plays an important role in bridging the gap between government and the social media industry, in providing public education, and in developing and monitoring adherence to safety standards. That said, the Commission's brief is far broader than self-harm and suicide and perhaps more could be done to strengthen work in this area.

There was strong support for international collaboration and moderate support for an international body to help support online safety efforts. International collaboration on this issue makes good sense. Rates of self-harm and suicide in young people are increasing in many parts of the world (39, 40) and social media companies are multi-national, therefore, more coordinated efforts including the development of international safety standards and cross-sector collaboration is a logical next step. It's possible that international bodies such as the World Health Organisation or the International Association for Suicide Prevention could play a role here.

In terms of other steps policymakers could be taking, there was strong agreement that government should support public health campaigns promoting safe online communication. There is some evidence regarding the effectiveness of public health campaigns for suicide prevention generally (41), but to the best of our knowledge, few campaigns exist specifically on this topic or that target young people. One exception may be the #chatsafe social media campaign that was tested in two separate studies and appeared to improve young people's perceived online safety when communicating about suicide and their willingness to intervene against suicide online (12, 42). However, these were relatively small pilot studies and more work is needed to robustly assess the effectiveness of such campaigns.

There was moderate agreement that governments should require secondary school curricula to include education about safe online communication about self-harm and suicide and mixed views regarding primary schools. School curricula are already crowded, but schools are an obvious place to provide education to young people about online safety and an acceptable setting for suicide prevention activities (43). As such, it stands to reason that at least some degree of education regarding online safety when communicating online about self-harm and suicide could be a useful addition to school curricula. It may also be useful for this type of education to extend beyond students and to include both educators and parents/carers.

Somewhat surprisingly, there were mixed views regarding blanket regulation of the platforms by government, and legislation making certain types of content posted by users illegal. That said, there was some support (particularly from young people) for legislation prohibiting companies from allowing accounts that promote or encourage self-harm or suicide and that would hold companies accountable for content posted on their platforms.

Limitations and strengths

This was by no means a large-scale representative survey; nor was it intended to be. Rather, the survey items were nested within a larger Delphi study, the main purpose of which was to inform the development of new #chatsafe guidelines. As such, the study findings cannot be generalised beyond the study population and a larger, representative survey is warranted. However, the fact that the survey was nested in the Delphi study is also a strength, as the survey was based on a robust review of the literature plus consultations with key stakeholders, including young people, policymakers, and representatives from social media companies. A further limitation was the uneven distribution of the two panels with more than twice as many young people as professionals, although the level of engagement from young people may also be considered a strength. Additionally, the youth panel comprised only young people from Australia. This was a deliberate decision to facilitate safety management during the study, but it further limits generalisability.

Conclusions

This study examined the views of young people and suicide prevention professionals about the steps that social media companies and policymakers should take to improve online safety when it comes to self-harm and suicide. Although many of the strategies identified are already being implemented, at least to a certain extent, it is clear that more could be done.

Our findings reflect the complexity associated with trying to achieve a balance that minimises the risks of communicating online about self-harm or suicide (i.e., exposure to harmful content) whilst capitalising on some of the benefits (i.e., opportunities for intervention). Indeed, much of our work, and that of others has demonstrated that online communication about self-harm and suicide is both complex and nuanced, and content, or decisions, that may be helpful for some may be harmful for others (13, 44). With such a large user base (Meta's platforms currently have around 3.9 billion (45) users and TikTok has 755 million (46)), even small changes to their policies and practices can have a significant impact on suicide prevention efforts worldwide.

A clear message was the need for better collaboration between policymakers and the social media industry and between government and its international counterparts. To the best of our knowledge, no national or international suicide prevention policies include recommendations relating to online safety and to date there is no international body coordinating efforts in this area. In our view addressing these gaps would help to create safer online environments and would help make inroads into reducing self-harm and suicide among young people.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because Ethical approval does not allow for sharing of data due to the vulnerable participant population. Requests to access the datasets should be directed toam8ucm9iaW5zb25Ab3J5Z2VuLm9yZy5hdQ==.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by The University of Melbourne Human Research Ethics Committee (ID: 22728). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

JR: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PT: Investigation, Writing – original draft. SM: Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HR: Writing – review & editing. RB: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. ML: Project administration, Writing – original draft. LH: Investigation, Writing – original draft. LL: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The #chatsafe project receives funding from the Commonwealth Department of Health under the National Suicide Prevention Leadership and Support Program. JR is funded by a National Health and Medical Research Council Investigator Grant (ID2008460) and a Dame Kate Campbell Fellowship from the University of Melbourne. LLS is funded by a Suicide Prevention Australia Postdoctoral Fellowship.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all panel members for their participation.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frcha.2023.1274263/full#supplementary-material

References

1. World Health Organisation. Suicide: WHO; (2021). Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide

2. World Health Organisation. Suicide: one person dies every 40 s: WHO; (2019). Available at: https://www.who.int/news/item/09-09-2019-suicide-one-person-dies-every-40-seconds

3. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Causes of Death, Australia. Australian Government; (2021). Available at: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/causes-death/causes-death-australia/latest-release

4. Glenn CR, Kleiman EM, Kellerman J, Pollak O, Cha CB, Esposito EC, et al. Annual research review: a meta-analytic review of worldwide suicide rates in adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2020) 61(3):294–308. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13106

5. Hawton K, Harriss L, Hall S, Simkin S, Bale E, Bond A. Deliberate self-harm in Oxford, 1990-2000: a time of change in patient characteristics. Psychol Med. (2003) 33(6):987–95. doi: 10.1017/S0033291703007943

6. McMahon EM, Hemming L, Robinson J, Griffin E. Editorial: suicide and self harm in young people. Front Psychiatry. (2023) 13:1–4. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.1120396

7. McManus S, Gunnell D, Cooper C, Bebbington PE, Howard LM, Brugha T, et al. Prevalence of non-suicidal self-harm and service contact in England, 2000–14: repeated cross-sectional surveys of the general population. Lancet Psychiatry. (2019) 6(7):573–81. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30188-9

8. Victor SE, Klonsky ED. Correlates of suicide attempts among self-injurers: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. (2014) 34(4):282–97. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2014.03.005

9. Hampton MD. Social media safety: who is responsible: teens, parents, or tech corporations? J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. (2023) 29(3):10783903231168090. doi: 10.1177/10783903231168090

10. Memon AM, Sharma SG, Mohite SS, Jain S. The role of online social networking on deliberate self-harm and suicidality in adolescents: a systematized review of literature. Indian J Psychiatry. (2018) 60(4):384–92. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_414_17

11. Samaritans. How social media users experience self-harm and suicide content: Samaritans; (2023). Available at: https://media.samaritans.org/documents/Samaritans_How_social_media_users_experience_self-harm_and_suicide_content_WEB_v3.pdf

12. La Sala L, Teh Z, Lamblin M, Rajaram G, Rice S, Hill NTM, et al. Can a social media intervention improve online communication about suicide? A feasibility study examining the acceptability and potential impact of the #chatsafe campaign. PLoS One. (2021) 16(6):e0253278. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0253278

13. Lavis A, Winter R. #Online harms or benefits? An ethnographic analysis of the positives and negatives of peer-support around self-harm on social media. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2020) 61(8):842–54. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13245

14. Robinson J, La Sala L, Battersby-Coulter R. Safely navigating the terrain: keeping young people safe online. In: House CBA, editors. Social media and mental health. Melbourne: Cambridge University Press (2023). p. 1–10.

15. Thorn P, Hill NTM, Lamblin M, Teh Z, Battersby-Coulter R, Rice S, et al. Developing a suicide prevention social media campaign with young people (the #chatsafe project): co-design approach. JMIR Ment Health. (2020) 7(5):e17520. doi: 10.2196/17520

16. Robinson J, Hill NTM, Thorn P, Battersby R, Teh Z, Reavley NJ, et al. The #chatsafe project. Developing guidelines to help young people communicate safely about suicide on social media: a delphi study. PLoS One. (2018) 13(11):e0206584. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0206584

17. Government UK. A guide to the Online Safety Bill: United Kingdom Government (2022). Available at: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/a-guide-to-the-online-safety-bill

18. Australian Government. Online Safety Act 2021: Australian Government (2021). Available at: https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2021A00076

19. Government US. Children’s Online Privacy Protection Rule (“COPPA”): United States Government (1998). Available at: https://www.ftc.gov/legal-library/browse/rules/childrens-online-privacy-protection-rule-coppa

20. Government US. S.3663 — 117th Congress (2021-2022): United States Government (2022). Available at: https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/senate-bill/3663/text

21. Bridgland V, Jones P, Bellet B. A Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Trigger Warnings, Content Warnings, and Content Notes (2022).

22. Robinson J, Thorn P, McKay S, Hemming L, Battersby-Coulter R, Cooper C, et al. #chatsafe 2.0: Updated guidelines to support young people to safely communicate online about self-harm and suicide. A Delphi study [Manuscript submitted for publication]. 2023.

23. Thorn P, McKay S, Hemming L, Reavley N, La Sala L, Sabo A, et al. #chatsafe: A young person’s guide to communicating safely online about self-harm and suicide. Edition two. Orygen; 2023. Available at: https://www.orygen.org.au/chatsafe

24. Shoib S, Chandradasa M, Nahidi M, Amanda TW, Khan S, Saeed F, et al. Facebook and suicidal behaviour: user experiences of suicide notes, live-streaming, grieving and preventive strategies—a scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19(20):13001. doi: 10.3390/ijerph192013001

25. Cohen-Almagor R, Lehman-Wilzig S. Digital promotion of suicide: a platform-level ethical analysis. J Media Ethics. (2022) 37(2):108–27. doi: 10.1080/23736992.2022.2057994

26. Niederkrotenthaler T, Voracek M, Herberth A, Till B, Strauss M, Etzersdorfer E, et al. Role of media reports in completed and prevented suicide: werther v. Papageno effects. Br J Psychiatry. (2010) 197(3):234–43. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.074633

27. Domaradzki J. The werther effect, the papageno effect or no effect? A literature review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18(5):1–20. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18052396

28. Nock MK, Millner AJ, Ross EL, Kennedy CJ, Al-Suwaidi M, Barak-Corren Y, et al. Prediction of suicide attempts using clinician assessment, patient self-report, and electronic health records. JAMA Network Open. (2022) 5(1):e2144373-e. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.44373

29. Large MM. The role of prediction in suicide prevention. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. (2018) 20(3):197–205. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2018.20.3/mlarge

30. Little O, Richards A. TikTok’s algorithm leads users from transphobic videos to far-right rabbit holes: Media matters; 2021. Available at: https://www.mediamatters.org/tiktok/tiktoks-algorithm-leads-users-transphobic-videos-far-right-rabbit-holes (updated 10 May 2021).

31. Weimann G, Masri N. Research note: spreading hate on TikTok. Stud Confl Terror. (2023) 46(5):752–65. doi: 10.1080/1057610X.2020.1780027

32. Saurwein F, Spencer-Smith CJM. Automated trouble: the role of algorithmic selection in harms on social media platforms. Media Commun. (2021) 9(4):222–33. doi: 10.17645/mac.v9i4.4062

33. Aldhyani THH, Alsubari SN, Alshebami AS, Alkahtani H, Ahmed ZAT. Detecting and analyzing suicidal ideation on social media using deep learning and machine learning models. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19(19):1–16. doi: 10.3390/ijerph191912635

34. Roy A, Nikolitch K, McGinn R, Jinah S, Klement W, Kaminsky ZA. A machine learning approach predicts future risk to suicidal ideation from social media data. npj Digit Med. (2020) 3(1):78. doi: 10.1038/s41746-020-0287-6

35. Ruiz R. Inside the program teaching influencers to talk about mental health: Why social media stars are taking this mental health education course. New York City, NY: Mashable (2020).

36. Meta. How Meta works with law enforcement: Meta; (2022). Available at: https://transparency.fb.com/en-gb/policies/improving/working-with-law-enforcement/ (updated 19 January 2022).

37. Mishara BL, Weisstub DN. The legal status of suicide: a global review. Int J Law Psychiatry. (2016) 44:54–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2015.08.032

38. Robinson J, Teh Z, Lamblin M, Hill NTM, La Sala L, Thorn P. Globalization of the #chatsafe guidelines: using social media for youth suicide prevention. Early Interv Psychiatry. (2021) 15(5):1409–13. doi: 10.1111/eip.13044

39. Gillies D, Christou MA, Dixon AC, Featherston OJ, Rapti I, Garcia-Anguita A, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of self-harm in adolescents: meta-analyses of community-based studies 1990-2015. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2018) 57(10):733–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2018.06.018

40. Griffin E, McMahon E, McNicholas F, Corcoran P, Perry IJ, Arensman E. Increasing rates of self-harm among children, adolescents and young adults: a 10-year national registry study 2007-2016. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2018) 53(7):663–71. doi: 10.1007/s00127-018-1522-1

41. Pirkis J, Rossetto A, Nicholas A, Ftanou M, Robinson J, Reavley N. Suicide prevention media campaigns: a systematic literature review. Health Commun. (2019) 34(4):402–14. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2017.1405484

42. La Sala L, Pirkis J, Cooper C, Hill NTM, Lamblin M, Rajaram G, et al. Acceptability and potential impact of the #chatsafe suicide postvention response among young people who have been exposed to suicide: pilot study. JMIR Hum Factors. (2023) 10:1–16. doi: 10.2196/44535

43. Robinson J, Cox G, Malone A, Williamson M, Baldwin G, Fletcher K, et al. A systematic review of school-based interventions aimed at preventing, treating, and responding to suicide- related behavior in young people. Crisis. (2013) 34(3):164–82. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000168

44. Thorn P, La Sala L, Hetrick S, Rice S, Lamblin M, Robinson J. Motivations and perceived harms and benefits of online communication about self-harm: an interview study with young people. Digit Health. (2023) 9:1–13. doi: 10.1177/20552076231176689

45. Shvartsman D. Facebook: The Leading Social Platform of Our Times (2023). Available at: https://www.investing.com/academy/statistics/facebook-meta-facts/#:∼:text=More%20than%2077%25%20of%20Internet,at%20least%20one%20Meta%20platform.: Investing.com (updated 28 April 2023).

46. Yuen M. TikTok users worldwide (2020-2025): Insider Intelligence (2023). Available at: https://www.insiderintelligence.com/charts/global-tiktok-user-stats/ (updated 24 April 2023).

Keywords: suicide, self-harm, social media, young people, survey

Citation: Robinson J, Thorn P, McKay S, Richards H, Battersby-Coulter R, Lamblin M, Hemming L and La Sala L (2023) The steps that young people and suicide prevention professionals think the social media industry and policymakers should take to improve online safety. A nested cross-sectional study within a Delphi consensus approach. Front. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2:1274263. doi: 10.3389/frcha.2023.1274263

Received: 8 August 2023; Accepted: 23 November 2023;

Published: 15 December 2023.

Edited by:

Jennifer Chopra, Liverpool John Moores University, United KingdomReviewed by:

Matt Dobbertin, Boys Town National Research Hospital, United StatesClaire Hanlon, Liverpool John Moores University, United Kingdom

© 2023 Robinson, Thorn, Mckay, Richards, Battersby-Coulter, Lamblin, Hemming and La Sala. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jo Robinson Sm8ucm9iaW5zb25Ab3J5Z2VuLm9yZy5hdQ==

Jo Robinson

Jo Robinson Pinar Thorn1,2

Pinar Thorn1,2 Hannah Richards

Hannah Richards Louise La Sala

Louise La Sala