- 1Technical University of Munich, TUM School of Management, Munich, Germany

- 2Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, United States

Introduction: As life expectancy and expected years in retirement rise and family structures change, the need for personal financial protections, such as long term care (LTC) insurance, in managing financial risks associated with later life is expected to increase. Roughly half of American households are at risk of not being able to maintain their present standards of living post-retirement. Because both public and private health insurance programs typically do not cover LTC needs, which are associated with significant costs, the potential demand for LTC further exacerbates the retirement savings crisis.

Methods: Using an original survey experiment, in this high-powered study (N = 1,450), we examine the impact of a 2×3 framing intervention on participants' attitudes, emotions, and behavioral intentions toward LTC insurance.

Results: Results indicated that direct framing effects were present for people's reported emotions: those who received a loss frame (compared to a gain frame) were more likely to report anxiety-related emotions, and those who were exposed to a care choice narrative frame (compared to a family or a financial frame) were more likely to report calmness-related emotions. There were no significant interaction effects between loss/gain and narrative frames. A mediation analysis suggested that the framing impacts acted through these two different emotional pathways to yield more positive attitudes toward and behavioral intentions around LTC.

Implications: The study results underscore the need to examine how different frames affect emotional arousal as a potential pathway to impacting attitudes and behaviors. We found that both a loss framing and a narrative framing, operating through different emotional pathways, have the potential to be helpful to nudge people to hedge against a financial risk associated with older age.

Introduction

One of the risks that may accompany aging is the development of acute or chronic health conditions, including dementia, that require professional caregiving or other supportive services. It is estimated in the U.S. that seventy percent of people age 65 and older will need some form of long term care (LTC) at some point (Johnson, 2019). Such care costs are often expensive; AARP estimated that out-of-pocket LTC expenses total $140,000 on average, although costs vary by geographic location and the extent and nature of care needed (Stark and Fedele, 2018). Further, there is limited to no coverage available for LTC expenses from private health insurers, Medicare, or Medicaid (Johnson, 2019). Many older adults who do require LTC receive it from family or friends, in part due to the high costs of paying for care (Johnson and Wang, 2019). Yet the need for paid care may increase in the future as the relative availability of family caregivers is forecast to decline due to population aging and changes in family structures (Redfoot et al., 2013). Research suggests that over half of middle-income older adults will lack the financial resources to pay for their future care and housing needs, ultimately threatening their ability to live independently (Pearson et al., 2019). As a result, should they or another family member such as a spouse have a need for LTC, individuals face substantial risks to their financial security.

There are financial products—notably LTC insurance—available in the financial marketplace that people can purchase to hedge against their potential future LTC needs and to protect their savings. But the decision to purchase such insurance is made under great uncertainty. When people need to decide as young adults or in midlife to purchase LTC insurance (when the rates are relatively less expensive and the products are more accessible), they are uncertain whether they will actually need or use the product in the future. Belbase et al. (2021) calculated that people's needs for LTC and its associated costs are not evenly distributed across the population, estimating that about one in four individuals will have “the type of severe needs that most people dread,” but that 17% will have no need for LTC (Belbase et al., 2021). The remaining individuals will have some degree of LTC needs, but these will vary in duration and intensity. While some people with heritable conditions, such as Huntington's disease, may have some sense of their potential future LTC needs, most people will not know the duration and intensity—and thus the associated costs—of their future care needs.

Despite the rationale for purchasing private insurance to cover care costs associated with late-in-life health risks, the uptake of LTC insurance is lower than predicted by standard economic theory, with only 3%−4% of Americans aged 50 and older holding a LTC insurance policy (Rau and Aleccia, 2023). Given financial risks that individuals may face around their potential future care needs, the importance of effective interventions to financially protect against unforeseen LTC costs, such as through LTC insurance uptake, becomes apparent. In this study, we examine how different message framings, which have been shown to be effective in influencing people's attitudes and intensions around a variety of different decisions (e.g., Gallagher and Updegraff, 2012; Gilovich and Griffin, 2010; Keller and Lehmann, 2008), affect people's attitudes and purchase intentions around LTC insurance.

Messages can be framed in different ways, for instance, gain/loss frames are common in the literature (O'Keefe and Jensen, 2007, 2009; Rothman et al., 2006). In the context of LTC insurance, the purchase of insurance can be framed either as the chance of gaining a positive outcome or preventing a loss. Beyond that, message framing also can refer to the “narrative packaging of an issue, which highlights some elements as central to the issue and relegates other elements to the periphery” (Krosnick et al., 2010, p. 1310). Often, the effect of framing can operate through emotions and while emotions play a significant role in decision-making processes (Brighetti et al., 2014; Loewenstein, 2000; Rustichini, 2005), they have mainly been neglected in traditional research on decision-making, and there exists a particular research gap on the role of emotions in insurance decisions (Brighetti et al., 2014; Buzatu, 2013). In order to understand how to increase the uptake of LTC insurance, there is a need for research focusing on the role of emotions when thinking about and planning for potential future LTC needs and costs. We address this important research need by conducting an online experiment with a sample of 1,450 individuals who are in the target market for LTC insurance. Our results show two pathways through which attitudes and intentions toward LTC insurance can be improved. First, we find that a framing intervention can effectively induce anxiety, which is associated with positive attitudes and intentions toward LTC insurance. Additionally, we find that narrative framing can effectively induce feeling of calmness, which are also associated with positive LTC insurance attitudes and intensions. Our study results suggest that both the framing and content of interventions, through different emotional pathways, have the potential to be helpful for employers already offering optional LTC insurance benefits and for policymakers wishing to nudge people to hedge against a financial risk associated with older age.

Message framing interventions

Message framing effects, which “involve instances in which choices are influenced by different descriptions of the same objective information,” (Gilovich and Griffin, 2010, p. 575) grew out of Prospect Theory (Kahneman and Tversky, 1979; Tversky and Kahneman, 1981) as a key means to understand how—and why—people make different decisions and social judgments. One of the most widely and commonly used applications of this work has been to frame messages in terms of gains (when people are more likely to respond with risk aversion) or losses (when people are more likely to be risk seeking; Gilovich and Griffin, 2010). In short, messages are often constructed to highlight either the benefits of making a given choice or adopting a specific behavior (i.e., a gain-frame) or the negative consequences of making (or failing to make) a particular choice or failing to adopt a specific behavior (i.e., a loss-frame).

Yet message framing need not be limited simply to variations on gain and loss frames (e.g., endowment effects, temporal framing, narrow framing). Beyond the definition of frames as providing identical objective information, other lines of research build on work by Gamson and colleagues (e.g., Gamson and Lasch, 1983; Gamson and Modigliani, 1989) to explore how the “narrative packaging of an issue, which highlights some elements as central to the issue and relegates other elements to the periphery” (Krosnick et al., 2010, p. 1310) affects people's judgment and decisions (see also Druckman and McDermott, 2008; Leeper and Slothuus, 2020). For example, Nelson and Kinder (1996) examine how different narrative frames around spending on anti-poverty programs, AIDS funding, and affirmative action affect people's attitudes; more recently, Culpepper et al. (2024) conducted an experiment to explore how a narrative frame around the “economy being rigged” affected people's attitudes toward redistribution. Beyond that, Bauer et al. (2022) reported that in two large field experiments with 226,946 and 257,433 pension fund participants, peer-information statements were not effective in increasing the look-up rate of pension information, but financial incentives were.

The model for understanding framing effects on people's attitudes has often been treated as a direct one: people are exposed to a particular framing of a problem or issue, and their judgments and behaviors are shaped by these. Yet while this direct effect of frame on output may be present, the relationship between the information people receive and their subsequent decisions is often more complex, with emotions playing a significant role in decision-making processes (Brighetti et al., 2014; Lerner et al., 2015; Loewenstein, 2000; Rustichini, 2005). In the context of research around framing effects, emotions have been found to serve as mediators. For example, Nabi et al. (2018) found that hope and fear emotions mediated the impacts of gain and loss messages on attitudes and advocacy behaviors related to climate change. People exposed to a gain frame were more likely to report feeling hope, which in turn directly affected attitudes and behavior; those exposed to a loss frame were more likely to report fear, which in turn affected attitudes but did not directly affect behavior. In a different study that employed a narrative framing experiment around populist rhetoric and attitudes, Demasi et al. (2024) found a small mediation effect of negative (but not positive) emotions on populist attitudes for participants exposed to an injustice frame. However, when people were primed with an elaboration task ahead of exposure to the message, these mediation effects of negative (but not positive) emotions were amplified.

In the context of LTC insurance in particular research utilizing message framing has been limited (e.g., Gottlieb and Mitchell, 2020), but there is previous research on insurance to suggest that people's tolerance for loss aversion may affect their insurance preferences. For example, Hwang (2021) discovered a negative correlation between loss aversion and life insurance demand, while both Burnett and Palmer (1984) and Eling et al. (2021) found positive correlations between risk-seeking behavior and life insurance purchases. Eling et al. (2021) also explored the connection between preferences and LTC insurance purchases, finding that people who were more willing to take financial risks were also more likely to have LTC insurance. In considering their results, Eling et al. (2021) suggest that Prospect Theory frameworks should be considered in the context of understanding people's LTC insurance preferences, but they also note that researchers may need to develop a better understanding of people's conceptions of LTC insurance itself: do they view LTC insurance as a risk mitigation strategy or tool, or do they view it as a risky product?

Yet in the context of decisions and advertisements related to different kinds of financial choices and insurance, the effectiveness of loss or gain frames appears not to be constant but to be contingent on different factors. For example, in a field experiment with younger participants (ages 25–49), Blanchard and Trudel (2023) found that temporal considerations impacted framing effects: gain-framed messages were more effective in eliciting clicks on life insurance advertisements than loss-framed messages, unless the message emphasized immediate benefits. In contrast, in a series of studies looking at people's willingness to acquire information about their pensions, Eberhardt et al. (2021) found that prevention-oriented (i.e., loss) frames were more effective.

Further complicating framing around LTC insurance decisions is the multifaceted context of LTC planning itself. In a qualitative focus group study conducted by Ashebir et al. (2022) exploring how people consider and plan for future LTC needs and the role of LTC insurance, participants highlighted LTC costs, family considerations, and the type and quality of future care they could receive as important factors when making decisions about their future LTC needs. As such, it is possible that different narrative message framings of LTC may elicit different emotions or lead to different behavioral outcomes, particularly in combination with a gain/loss framing. For example, a gain frame may be more effective when highlighting the effects of LTC needs on other family members, while a loss frame may be more impactful on attitudes when highlighting the costs of LTC. While more research is needed on how message framing influences LTC insurance decisions, it is also important to examine whether and how the effectiveness of gain or loss-frames may interact with different LTC narrative frames highlighted within a message.

Considering previous mixed results on gain and loss frames and because different narrative frames of LTC planning may be more or less powerful in eliciting different emotional responses, attitudes, and behavioral intentions toward LTC, we propose the following exploratory analysis:

Exploratory analysis 1: Are there differences in how different narrative frames impact people's emotional responses, attitudes, and behavioral intentions toward LTC? Are different narrative frames in combination with loss or gain frames more or less powerful?

The role of emotions

There exists a particular research gap on the role of emotions in insurance decisions (Brighetti et al., 2014; Buzatu, 2013; Loewenstein, 2000). Traditional research on insurance demand has primarily focused on individual preferences, contract design, and decision framing. Emotions such as regret and disappointment have been integrated into economic calculations, but the potential impacts of a broader spectrum of emotions have only recently begun to be explored. Two recent studies examined the relationship between an individual's emotional state and their decision to purchase insurance (Biener et al., 2020; Yan et al., 2020). For instance, in an experiment simulating a terrorist attack, Yan et al. (2020) found that the emotion elicited by these attacks (fear vs. anger) influenced participants' willingness to pay for private insurance or public spending to reduce the risk of such an attack. Similarly, Biener et al. (2020) found that participants' fear for their privacy affected their willingness to pay for insurance; people were only willing to give up part of their privacy (by using activity trackers) in return for a substantial reduction in their insurance premium, which would make the insurance unprofitable for insurers. These findings suggest that emotions can significantly affect individuals' perception of risks (Prietzel, 2020; Wake et al., 2020) and subsequent insurance decisions. If subjective probabilities are affected by emotion, as previously argued (Leith and Baumeister, 1996; Wright and Bower, 1992), then the subjective assessment of a risk event may be increased by negative emotions such as fear or anxiety and decreased by positive emotions such as calmness.

Examining the role of emotions in the context of insurance decision-making can deepen the understanding of how framing affects emotional reactions and how these emotions may mediate people's choices. Considering the common notion that fear and anxiety increase risk estimations and decrease risk-taking (Wake et al., 2020), which should factor into LTC insurance uptake, we suggest the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1a. Increased anxiety-related emotions mediate the effect of a loss frame on attitudes and behavioral intentions toward LTC insurance.

Hypothesis 1b. Increased calmness-related emotions mediate the effect of a gain frame on attitudes and behavioral intentions toward LTC insurance.

Methods

Procedure

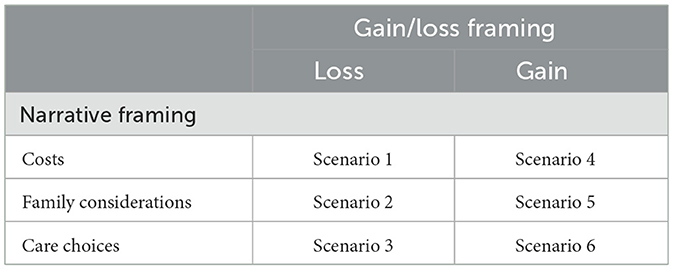

The study was designed as an online survey experiment collected via the Dialsmith platform. Approximately halfway through the survey, participants were randomly assigned to view one of six videos depicting a version of a fictional conversation between a financial advisor and a client about LTC insurance; during the video they were asked to continuously respond positively or negatively to the content using a slider bar on the video. All videos began with an identical opening where the financial advisor introduced the concept of LTC planning by giving the client information on the prevalence of LTC needs and what exactly LTC insurance typically covers. After being prompted for more information about LTC insurance by the client, the content across videos diverges. Based on message framing literature, the videos portray either a gain (three videos) or loss frame (three videos) when the advisor discusses LTC insurance. For example, survey respondents receiving a loss frame would hear the advisor focus on how unprepared the client would be for a LTC event without LTC insurance. In the gain frame, the advisor focuses on how LTC insurance would help the clients feel more prepared if a LTC event were to occur. Additionally, each of the videos focused on one of three narrative frames or content domains identified as salient in LTC planning decisions (Ashebir et al., 2024) including, cost (two videos), family considerations (two videos), and care choice (two videos). Overall, the six videos captured unique combinations of a gain/loss message frame as well as narrative framing to yield a 3 × 2 design (see Table 1). All videos concluded with an identical set of lines ending the conversation. Opening and closing scripts for the videos and the timing of frame presentation were identical across all videos, as the order information is presenting during financial conversations has been show to influence observer attitudes and perceptions (Agnew et al., 2018). Video length ranged from 3 min and 57 s to 4 min and 22 s. Video scripts were reviewed by financial professionals for accuracy; the scripts for each condition are available in Appendix A. All videos were filmed from the point of view of a client having a conversation with a financial advisor who sat at a desk across from them. The financial advisor for all videos was a Black man, and although an image of the client was never shown, client verbal responses to the financial advisor were delivered by a female client voice. All videos were filmed using the same set on the same day to ensure as much consistency as possible. This study was approved by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology's Committee on the Use of Humans as Experimental Subjects.

Participants

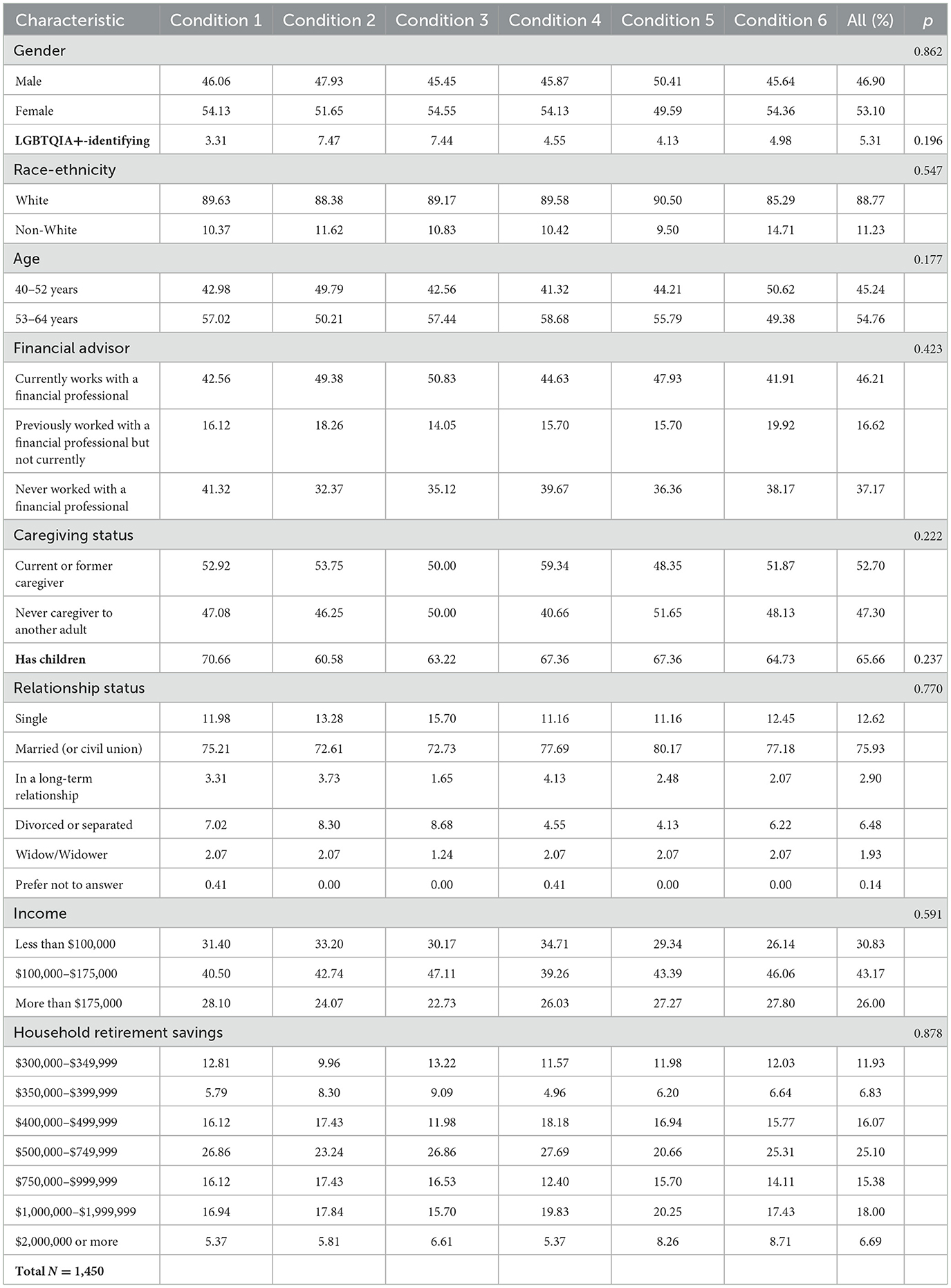

A total of 1,450 individuals in the target audience for LTC insurance but who did not at the time of the study possess an insurance policy or other kind of financial product that had LTC benefits completed the survey. Eligible respondents had to report having at least $300,000 in a dedicated retirement savings account as well as a minimum of $50,000 in liquid assets (outside of any retirement savings or home equity), as LTC customers typically have higher incomes and levels of liquid assets relative to the general population (Lifeplans Inc, 2017). Neither participants nor anyone in their immediate family or household could work for a financial services company, bank, or as a financial advisor or insurance agent. The sample was stratified by age (born 1958–1970 or 1971–1982) and gender. Sample demographics are described in Table 2. Randomization checks revealed no significant differences across the conditions in key demographic variables, such as age [F(1, 1, 448) = 1.44, p = 0.230], gender distribution [χ2(5) = 1.91, p = 0.861], or other baseline characteristics.

Measures

All emotion measures and the dependent attitude and intention variables were elicited after the video intervention.

Emotion variables

Emotion levels were measured by asking participants to what extent they felt a series of emotions when thinking about an “insurance policy that provides long-term care benefits.” Response options were on a 1–7 scale, with 1 anchored at “not at all” and 7 at “extremely.” After a factor analysis indicating two global factors, two composite scores were created, one for calmness-related and one for anxiety-related emotions. Four negative emotions (fearful, anxious, worried, and nervous) were combined to capture an overall score of an individual's anxiety-related emotions (Cronbach's α = 0.92) with higher scores reflecting higher levels of anxiety. Four positive emotions (optimistic, confident, comfortable, and calm) were combined to capture an overall score of an individual's calmness-related emotions (Cronbach's α = 0.89), with higher scores reflecting higher levels of calmness. In the emotions literature, it is not uncommon to create global variables to capture the variety of emotions expressed by participants, as there is value in using a scale rather than single items (Watson and Tellegen, 1985; Watson et al., 1988).

Perceived importance

Perceived importance was measured using the survey question, “How important do you think it is to have an insurance policy that provides long-term care benefits for you?” using a 6-point agreement scale.

Interest in learning more about long-term care insurance

Interest in learning more about long-term care insurance was assessed via the survey question, “How interested or uninterested are you in learning more about an insurance policy that provides long-term care benefits?” Participants selected from a 6-point interest Likert scale from “very uninterested” to “very interested.”

Behavioral intention to purchase long-term care insurance

Behavioral intention to purchase a long-term care insurance was measured using the survey question, “How likely or unlikely are you to purchase an insurance policy that provides long-term care benefits within the next 2 years for yourself?” Participants selected from a 6-point likelihood Likert scale from “extremely unlikely” to “extremely likely.”

Results

Data preparation and preliminary analyses

Following the American Psychological Association (APA) Task Force on Statistical Inference guidelines (Wilkinson, 1999), graphical checks for statistical prerequisites were conducted. Graphical checks of the variables' histograms and Q-Q-Plots showed that an adequate distribution was obtained except for negative emotions, which were right-skewed, such that the majority of respondents scored low on negative emotions. Nevertheless, given the large sample size in this study and the Central Limit Theorem, we included the unchanged variable in the analyses. Additionally, randomization checks indicated successful randomization across conditions (see Table 2). Moreover, Levene's tests showed that the assumption of homogeneity of variances was met; running all analyses with standard errors corrected for heteroscedasticity did not change the results (see Levene's test results in Appendix C).

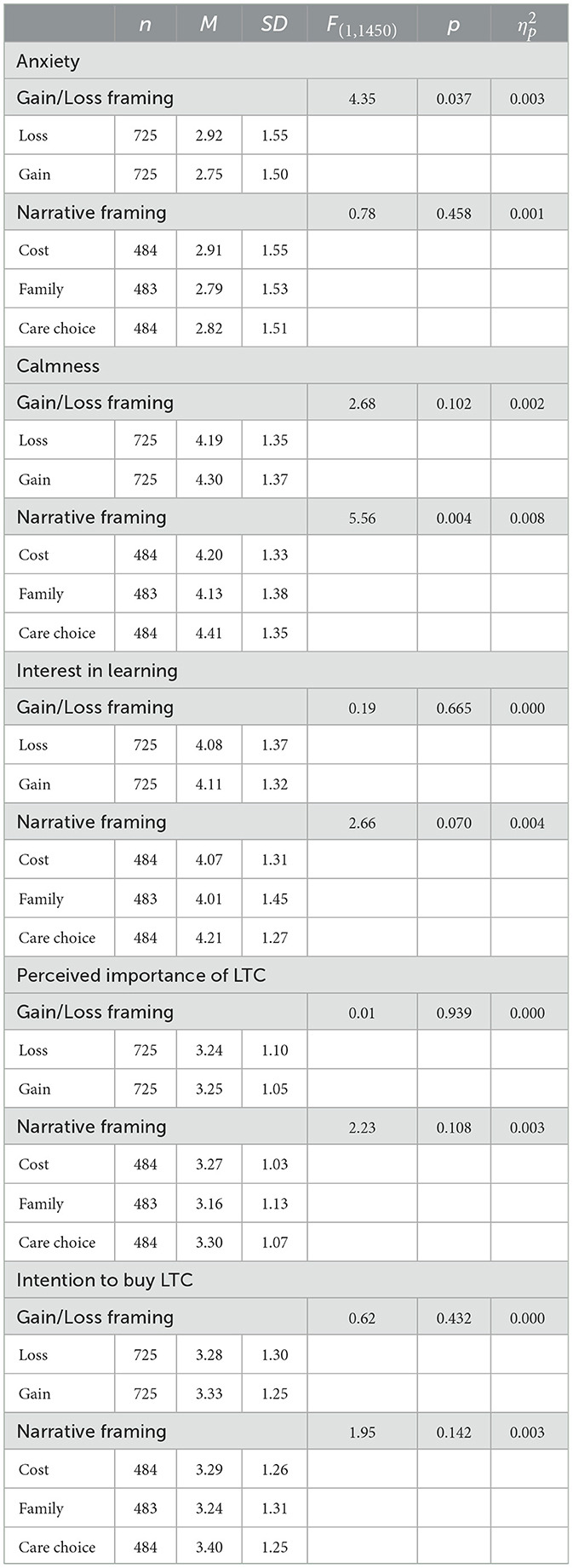

Exploratory analysis: framing effects

A series of univariate ANOVAs with an alpha-level of α = 0.05 were run for all dependent variables by loss/gain framing as well as by narrative framing (see Table 3). The interaction term between loss/gain framing and narrative framing did not yield significant results for any of the dependent variables (see Appendix C), and therefore, the six messaging conditions were pooled into two video sets for analysis: Two loss/gain framing conditions (3 loss vs. 3 gain) and three narrative framing conditions (2 care choice vs. 2 family vs. 2 cost). The explorative examination of narrative framing (cost, family considerations, or care choice) was informed by focus group feedback, which did not indicate a definitive preference or greater efficacy for any particular narrative frame. Subsequently, we conducted an exploratory analysis to determine if certain narrative frames had a more pronounced impact than others. Results of univariate ANOVAs examining loss/gain framing and narrative framing effects (Table 3) show that while neither loss/gain framing nor narrative framing had direct effects on perceived importance, interest in learning more about LTC, and LTC insurance purchase intension, loss framing did significantly affect reports of anxiety-related emotions (p = 0.037) while narrative framing significantly influenced reports of calmness (p = 0.004). Specifically, receiving the care choice framing resulted in significantly higher reports of calmness than for respondents who received the cost or family framing (see Table 3 and Appendix C). Because the care choice framing behaved in a distinct way compared to cost or family framings in our analyses, we combine cost and family into one framing for all subsequent mediation analysis.

Hypothesis testing: emotions mediation analyses

To test the impact of the indirect effects of framing on LTC attitudes empirically via the elicitation of different emotions, simple mediation analyses with anxiety-related and calmness-related emotions as meditators were conducted. Although there was no total effect of loss/gain framing or narrative framing on perceived importance, interest in learning more about LTC, and LTC insurance purchase intention, the analysis of indirect effects without a significant total effect is in line with others and prior recommendations (Hayes, 2009; Rucker et al., 2011). The mediation analyses were performed using Model 4 of the SPSS PROCESS Macro (Hayes, 2018) with loss/gain framing (coded: loss = −1, gain = 1) or narrative framing (coded: care choice = 1, cost and family consideration = −1) as the independent variable, the calmness emotion scale and anxiety emotion scale as mediators, and perceived importance, interest in learning more about LTC, and LTC insurance purchase intention as dependent variables (see Appendix B for mediation model). Regression weights and 95% confidence intervals were estimated using 5,000 bootstrap samples.

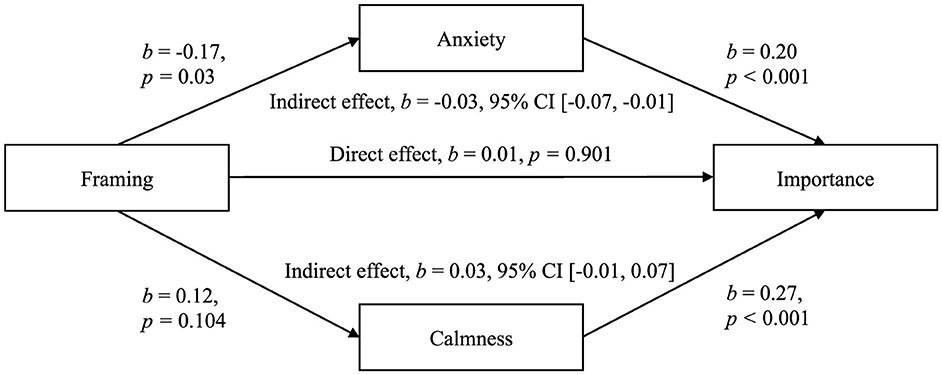

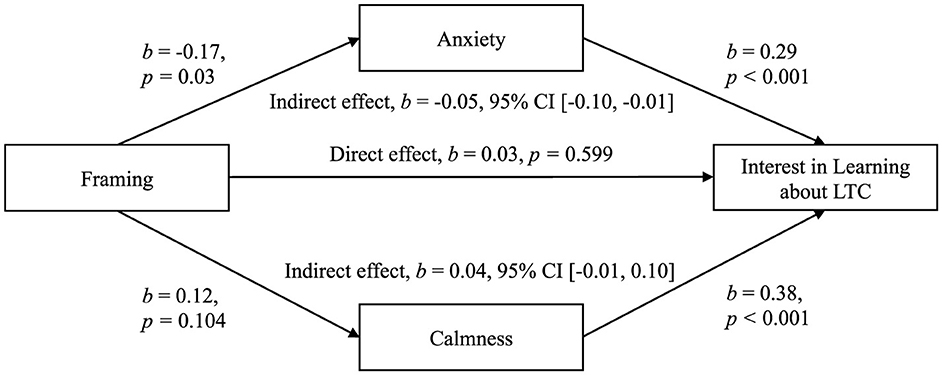

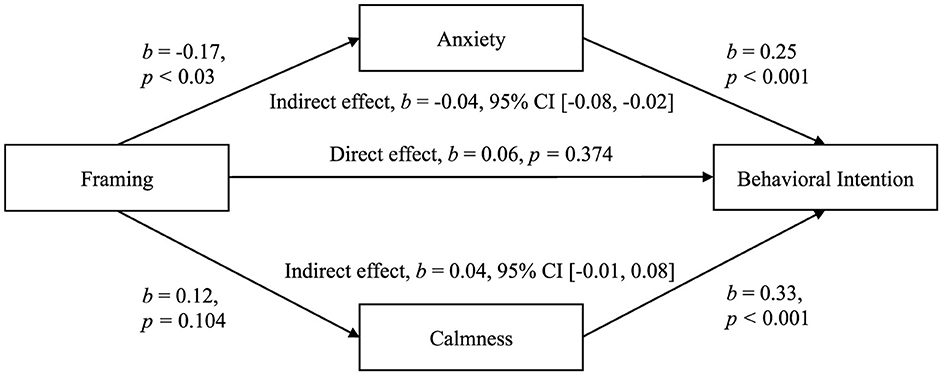

There were no significant direct effects of framing on perceived importance, interest in learning more about LTC, nor LTC insurance purchase intention, all bs < 0.1, all ps > 0.05. However, as Figures 1–3 illustrate, there were significant indirect effects of framing on perceived importance b = −0.03, 95% CI (−0.07, −0.01), interest in learning more about LTC b = −0.05, 95% CI (−0.10, −0.01), and LTC insurance purchase intention b = −0.04, 95% CI (−0.08, −0.02) mediated by anxiety-related emotions, but not by calmness-related emotions. In short, a loss framing was associated with higher perceived importance, interest in learning more about LTC, and LTC insurance purchase intention through higher anxiety-related emotions compared to a gain framing.

Figure 1. Mediation model testing the indirect effect of gain/loss framing via anxiety- and calmness-related emotions on the perceived importance of LTC. Regression weights b with 95% bootstrap confidence intervals (CI) are displayed.

Figure 2. Mediation model testing the indirect effect of gain/loss framing via anxiety- and calmness-related emotions on interest in learning more about LTC. Regression weights b with 95% bootstrap confidence intervals (CI) are displayed.

Figure 3. Mediation model testing the indirect effect of gain/loss framing via anxiety- and calmness-related emotions on behavioral intention to purchase LTC insurance. Regression weights b with 95% bootstrap confidence intervals (CI) are displayed.

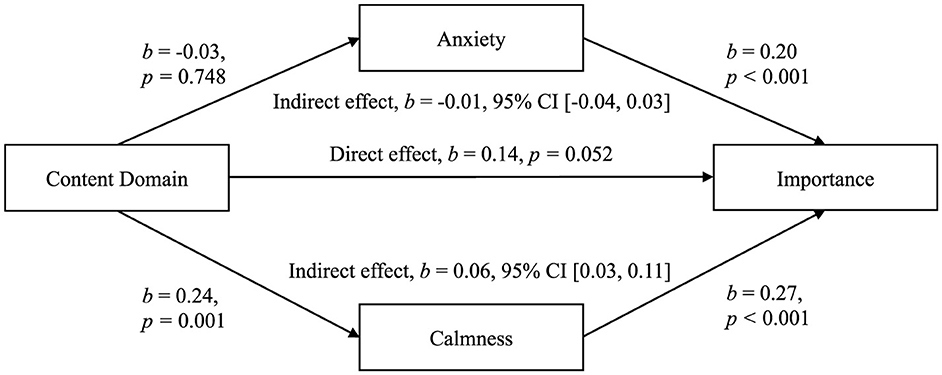

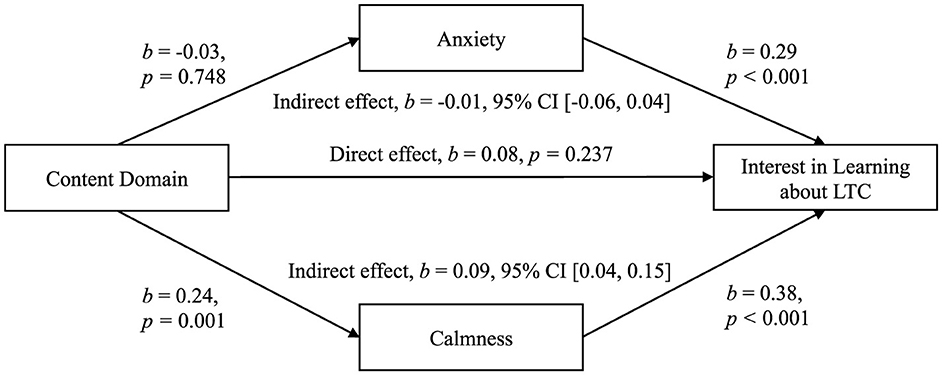

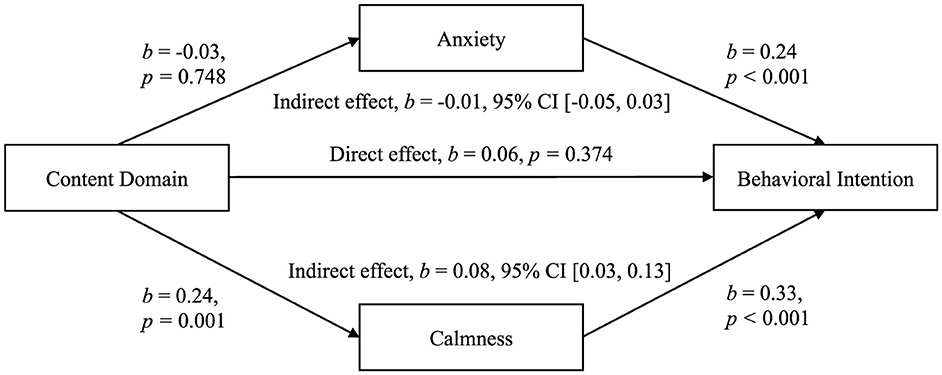

Similarly, there were no significant direct effects of narrative framing (care choice vs. family and cost) on perceived importance, interest in learning more about LTC, nor LTC insurance purchase intention, all bs < 0.2, 95%, all ps > 0.05. However, as Figures 4–6 illustrate, there were significant indirect effects of narrative framing on perceived importance b = 0.06, 95% CI (0.03, 0.11), interest in learning more about LTC b = 0.09, 95% CI (0.04, 0.15), and LTC insurance purchase intention b = 0.08, 95% CI (0.03, 0.13), mediated by calmness-related emotions. In short, a message focusing on care choices was associated with higher perceived importance, interest in learning more about LTC, and LTC insurance purchase intention through higher calmness-related emotions compared to messages focusing on family and cost aspects.

Figure 4. Mediation model testing the indirect effect of narrative framing via anxiety- and calmness-related emotions on the perceived importance of LTC. Regression weights b with 95% bootstrap confidence intervals (CI) are displayed.

Figure 5. Mediation model testing the indirect effect of narrative framing via anxiety- and calmness-related emotions on interest in learning more about LTC. Regression weights b with 95% bootstrap confidence intervals (CI) are displayed.

Figure 6. Mediation model testing the indirect effect of narrative framing via anxiety- and calmness-related emotions on behavioral intention to purchase LTC insurance. Regression weights b with 95% bootstrap confidence intervals (CI) are displayed.

Discussion

As the U.S. population ages and family structures change, the need for personal financial protections, such as LTC insurance, in managing risks associated with later life is expected to increase. The current uptake of LTC insurance, however, falls short of what economic forecasts suggest is needed. As people sometimes need a nudge to act in their own best long-term interest, message framing interventions can be deployed to encourage people to make better choices (e.g., Gallagher and Updegraff, 2012; Meyerowitz and Chaiken, 1987; O'Keefe and Jensen, 2007). Yet not all message framing interventions are equally successful across different kinds of decisions, and there is still much to be learned about how such effects function, including which types of frames and modes of communication are more effective. Despite the range of research on LTC insurance uptake, there is little evidence of effective interventions to increase uptake and no clear pattern about the attitudinal factors that support purchase. Thus, in this research, we examine both framing effects and the mediating role of emotions on attitudes and intentions toward LTC insurance. We developed an original message intervention that varies by loss/gain frame and narrative frame and assessed its effect in a randomized online experiment.

Results found two distinct pathways to induce positive attitudes and intensions toward LTC insurance. First, results indicated that a loss frame induced anxiety-related emotions which mediated the indirect effect of a loss frame on attitudes and behavioral intentions toward LTC insurance. Despite not increasing positive attitudes and intentions toward LTC insurance directly, the loss frame intervention was associated with increased perceived importance of LTC, interest in learning more about LTC, and the intention to buy LTC insurance indirectly via a mediated emotions pathway. Additionally, our exploratory analysis of different narrative frames suggested a second pathway through calmness-related emotions. Presenting participants with a care choice framing (regardless of loss or gain framing) elicited increased emotions of calmness, which again were associated with increased perceived importance of LTC, interest in learning more about LTC, and the intention to buy LTC insurance.

Theoretical implications

The present study is among the first to investigate the effect of message framing interventions on attitudes, emotions, and intentions toward LTC insurance. Our findings extend research that suggests that financial decision-making can be improved by eliciting emotions, and our results indicate two emotional pathways to impact financial attitudes around long term planning via either increasing anxiety-related emotions or calmness-related emotions. Thus, our work also addresses a significant gap in understanding the role of emotions in long-term financial decision-making that have been overlooked by traditional economic theories. By elucidating the emotional drivers behind insurance decision-making, this research suggests potential pathways to increase the uptake of LTC insurance.

The results from this analysis not only integrate into previous research on framing interventions and emotions in economic decision making, but they are also consistent with research on stress (Folkman and Lazarus, 1985). Planning for a longer life is often associated with uncertainty and stress; Folkman and Lazarus's (1985) transactional model of stress and coping emphasizes the role of cognitive appraisals in determining an individual's response to stress. Primary (i.e., anticipatory) appraisals involve evaluating the significance of an event or situation to determine whether the event is perceived as irrelevant, benign-positive, or a threat (stressful) for an individual's wellbeing. Longevity, and the necessity to hedge against the risk of a long-term care event, can be perceived as a threat, potentially causing harm or loss in the future, should the individual lack the resources to meet the challenge. Threat appraisals are associated with emotions such as worry, fear, and anxiety, reflecting a belief that the individual may lack the necessary resources to overcome the stressor, corresponding to effects elicited by the loss framing. In contrast, if the individual feels they have the resources to meet the challenge, the stressor may be perceived as an opportunity for growth or gain. This appraisal is linked to emotions like confidence, hope, and eagerness, corresponding with the effects elicited by the narrative frame of having care choices.

The results from this study further align with Kahneman and Tversky's (1979) principle that losses often have a more significant impact than gains. The current research adds a nuanced perspective to this principle by demonstrating that framing effects need not always be simple direct ones, but that their effects may operate through an appraisal model and the emotions aroused by exposure to the frame. This is particularly insightful when juxtaposed with previous research showing a negative correlation between loss aversion and life insurance demand and a positive correlation between risk-seeking behavior and life insurance purchases (Burnett and Palmer, 1984; Hwang, 2021). Furthermore, Blanchard and Trudel (2023) found that for younger individuals, gain-framed messages might be more influential in life insurance contexts. Our research, therefore, contributes a critical dimension to understanding how message framing may affect people's insurance-related decisions via emotions aroused by cognitive appraisals, particularly in the less-explored area of LTC insurance. However, additional research is needed to validate these findings.

Additionally, we delve into the aspect of losses not only being perceived as more significant than gains but also perceived as more likely to occur. This perception aligns with observations about the propensity of losses to attract attention and be imagined, thereby influencing decision-making processes (Bilgin, 2012). Our study provides some support for this by showing that participants rated the importance of LTC insurance as more crucial when exposure to loss-framed messages led to greater reports of anxiety emotions. Wake et al. (2020) highlight the tendency of fear and anxiety to decrease risk-taking, which in our study was associated with increased interest in insurance uptake.

Furthermore, the current study contributes to work on how narrative frames can affect people's judgment and decisions (e.g., Druckman and McDermott, 2008; Gamson and Lasch, 1983; Gamson and Modigliani, 1989), in the case of LTC insurance suggesting a second emotional pathway through calmness-related emotions elicited by highlighting care choices rather than family considerations or costs. Narrative frames that foster calmness-related emotions could support people's feelings of being able to address longevity challenges and in turn make financial planning and hedging against future risks feel more manageable and less daunting. This approach is consistent with research showing that positive emotions can facilitate more thoughtful and deliberate decision-making (Fredrickson, 2001). Moreover, the findings contribute to the broader literature on narrative frames by demonstrating how highlighting specific aspects (e.g., care choices) as central to the target issue can be strategically used to elicit helpful emotions and influence attitudes and behaviors positively. Overall, the identification of distinctive negative and positive emotional pathways suggests that interventions could be tailored to different demographic groups, specific contexts, emotional states, or personality types, potentially increasing the overall effectiveness of efforts to promote LTC insurance.

Practical implications

Broadly, our study suggests that the impacts of different frames may not always be directly observed on people's attitudes, intentions, or behaviors, but that the effects may operate through indirect pathways. In this analysis, we examine the impact of exposure to different frames on people's emotional reactions, which in turn were associated with different dependent outcomes of interest. Policymakers and others interested in how framing may help nudge people's behaviors in certain ways (e.g., to support healthy behaviors, to support better long term financial planning, etc.) may want to ensure that they look not only for direct effects of frame exposure but also at how these impacts operate on outcomes via emotions and the cognitive appraisals that implicitly underlie these.

The results of this research may be used to inform interventions such as educational programs to help individuals better understand the financial risks of longevity and the benefits of insurance, as well as to develop strategies to address emotional barriers people may experience around insurance uptake. The results indicate that there are two potential pathways that may affect uptake of LTC insurance products.

First, the uptake of LTC insurance may be increased by emphasizing the potential risks and losses associated with not having coverage. This could involve tailoring marketing strategies to highlight the financial and emotional burdens that LTC costs can impose on individuals and their families if they are not insured. By focusing on loss framings and the negative emotions they elicit, insurers might better capture the attention of potential customers and motivate them to consider LTC insurance as a necessary part of retirement planning. Similarly, financial advisors and planners could incorporate loss framing into their discussions with clients about retirement planning and LTC preparation. By understanding that loss framing can induce a greater sense of urgency and concern, advisors might more effectively persuade clients to take action on LTC planning, including the purchase of insurance and other financial preparations for potential care needs.

Second, these findings suggest that the content or narrative framing of messages can also affect attitudes and behavioral intentions. LTC insurance presented through the lens of future care choices induced higher levels of calmness, in turn increasing positive attitudes and intentions toward LTC products. For financial professionals who do not wish to induce anxiety-related emotions in certain clients, this research shows that focusing on the wider array of care choices LTC insurance can provide for future care needs may also help clients be more receptive to LTC insurance products. These findings suggest that financial professionals hoping to discuss LTC insurance with clients could delve into the details of what options or choices of care people may have in the future, as this information may be less readily accessible or top-of-mind for clients when thinking about the implications of longevity.

Limitations and future research

While this study offers valuable insights into the relationship between gain and loss as well as narrative frames in the context of LTC insurance, there are limitations to its results as well as indications for future research. The frames in this study had no direct effects on people's attitudes and behavioral intentions but rather indirect effects via emotions elicited in reaction to the messages. In a future study, researchers should explore message variations further (including other variations in narrative frames) to determine if these could materialize into direct effects within the context of LTC insurance and to test the robustness of the mediated emotions pathways. Further, the observed effect sizes remain small, potentially limiting the practical significance of the present results. The small effect sizes observed in this study may reflect a conservative estimate, likely due to the passive nature of the intervention. Participants simply watched a pre-recorded video without the opportunity for interaction or real-time engagement, which may have dampened their emotional responses and, consequently, the impact on their attitudes and behavioral intentions. In contrast, if these framings were presented through interactive, real-time conversations with financial professionals, the effects on emotional arousal, perceived relevance, and behavioral intentions toward LTC insurance might have been stronger. Nevertheless, small effect sizes are rather common in framing studies (O'Keefe and Hoeken, 2021), as framing effects, by their nature, often involve subtle shifts in preferences or judgments rather than dramatic changes. The psychological mechanisms underlying framing effects, such as risk aversion in loss frames, are nuanced and can be easily overshadowed by other factors in decision-making processes. Yet small effect sizes can have practical significance, especially in high-stakes domains like health and financial wellbeing communication or policy-making, where slight shifts in public behavior or attitudes can have substantial impacts (Götz et al., 2022). In this case, even modest increases in LTC insurance uptake, when scaled across a large population, can lead to substantial enhancements in coverage, crucial for public health and policy aimed at better preparing for aging demographics. Adopting a relative approach for effect size interpretation, which assesses the significance of effects in relation to their costs and context, reinforces the importance of evaluating effect sizes within their broader implications (Götz et al., 2022; Primbs et al., 2023). Notably, the current message intervention is cost-effective, rendering even slight improvements valuable. Here even small effect sizes can offer a considerable return on investment by boosting insurance uptake with minimal expense, underscoring their practical significance despite their size. Moreover, small effect sizes can still contribute to theoretical advancements by revealing the complex interplay of factors influencing decision-making, e.g., the role of emotions on the effect of framing interventions to increase LTC insurance uptake. As Götz et al. (2022) argue, nuanced consideration of small effects can yield important theoretical insights that might be overlooked if such effects were dismissed outright due to their size. Understanding these subtle influences can refine psychological theories of decision-making, framing, and intervention science.

Further, the participants of the current study are relatively wealthy, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to broader populations, particularly those with lower socioeconomic status who are less likely to be target consumers for this particular financial product. Policymakers concerned with the effects of these findings on less affluent populations should interpret the results with caution, as the outcomes observed here may not apply equally to all economic groups. Furthermore, for this particular issue, the results might be more relevant for this subpopulation, and the conclusions drawn could be specific to this context. Future research could explore whether these results translate across different subpopulations, with an eye toward understanding how the frames might intersect with people's cognitive appraisals of the product. For example, people with fewer financial resources might experience more stress in response to any framing related to LTC insurance, but this might not be associated with changes in attitudes or behavioral intentions. Regardless, while this study's findings may be specific to a wealthier subpopulation, the general emotion pathways framework we explored opens a new direction for future empirical work. The mechanisms identified may still hold across different populations, and future research should aim to examine this framework in more diverse and representative samples and across different domains such as health.

Beyond these limitations, the video message interventions in this study were fairly short, lasting anywhere from 3 min and 57 s to 4 min and 22 s; in reality, financial professionals' conversations with clients about such products may last longer, include more nuance, and occur over multiple sessions. Future research should explore how the channels of communication—for example, video, written content, or conversation—may also intersect with message framing to affect people's attitudes and behavioral intentions. Additionally, survey respondents had no prior relationship with the financial advisor depicted in the videos. Future research could examine whether the strength and longevity of a relationship with a financial professional, should people use one, influence how different message framing is perceived. Other limitations of the research included that this work focused on the impacts of different framings on LTC insurance but did not investigate actual insurance uptake decisions; such a study would require further field research but would offer more definitive support for the impact of message framing on behavior. Finally, this analysis treated the key target audience for LTC insurance products homogeneously. Future work could explore whether there are heterogenous impacts of framing based on group membership, for example, by age, gender, and wealth levels, to develop a deeper understanding of the power and limits of message framing in the context of LTC insurance.

Conclusion

This high-powered study with a national sample examined whether a gain or loss frame or various narrative frames more effectively impacted participants' attitudes, emotions, and behavioral intentions toward LTC insurance. Experimental results indicate that a loss frame induced more anxiety and overall negative emotions, while a care choice narrative frame induced greater feelings of calmness among respondents. Mediation analyses further indicated significant indirect effects of the loss frame and care choice frame on the perceived importance, interest in learning more about LTC, and purchase intentions mediated by anxiety-related emotions and calmness-related emotions, respectively. The results suggest that there are two pathways to persuade individuals to financially plan for potential future long-term care events and that emotions play a crucial role in these decision-making and mechanisms.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The study was approved by Massachusetts Institute of Technology's Committee on the Use of Humans as Experimental Subjects. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Study participants provided their informed consent before participating in this study.

Author contributions

NB: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Formal analysis. SA: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Software, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. SB: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Software, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. LD'A: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Software, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. JC: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Investigation, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The authors declare that this study received funding from Massachusetts Mutual Life Insurance Company (MassMutual). The MIT AgeLab gratefully acknowledges that MassMutual created the experimental intervention videos based on scripts and input provided from the research team and provided financial support for data collection, but they had no role in analysis, interpretation of results, or the decision to submit the paper for publication. The authors thank Dr. Julie Miller for her role in the project's conceptualization and design of the interventions.

Acknowledgments

Grammarly was used for copyediting.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frbhe.2024.1393384/full#supplementary-material

References

Agnew, J. R., Bateman, H., Eckert, C., Iskhakov, F., Louviere, J., Thorp, S., et al. (2018). First impressions matter: an experimental investigation of online financial advice. Manag. Sci. 64, 288–307. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.2016.2590

Ashebir, S., Balmuth, A., Brady, S., D'Ambrosio, L., Felts, A., and Coughlin, J. (2024). 'I Haven't REally Thought About It' Consumer atitudes related to long-term care. J. Financ. Res. 37, 264–76.

Ashebir, S., Brady, S., Coughlin, J. F., D'Ambrosio, L., Miller, J., DiGangi, M., et al. (2022). Connecting with your next generation retiree clients about LTC planning. CLTC Digest Fall. 2022, 13–16.

Bauer, R., Eberhardt, I., and Smeets, P. (2022). A fistful of dollars: financial incentives, peer information, and retirement savings. Rev. Fin. Stud. 35, 2981–3020. doi: 10.1093/rfs/hhab088

Belbase, A., Chen, A., and Munnell, A. H. (2021). What Level of Long-Term Services and Supports Do Retirees Need? (21–10). Newton, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Biener, C., Eling, M., and Lehmann, M. (2020). Balancing the desire for privacy against the desire to hedge risk. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 180, 608–620. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2020.03.007

Bilgin, B. (2012). Losses loom more likely than gains: Propensity to imagine losses increases their subjective probability. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 118, 203–215. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2012.03.008

Blanchard, S. J., and Trudel, R. (2023). Life insurance, loss aversion, and temporal orientation: a field experiment and replication with young adults. Market. Lett. 1–13. doi: 10.1007/s11002-023-09712-4

Brighetti, G., Lucarelli, C., and Marinelli, N. (2014). Do emotions affect insurance demand? Rev. Behav. Fin. 6, 136–154. doi: 10.1108/RBF-04-2014-0027

Burnett, J., and Palmer, B. (1984). Examining life insurance ownership through demographic and psychographic characteristics. J. Risk Insur. 51, 453–467. doi: 10.2307/252479

Buzatu, C. (2013). The influence of behavioral factors on insurance decision – a Romanian approach. Procedia Econ. Financ. 6, 31–40. doi: 10.1016/S2212-5671(13)00110-X

Culpepper, P. D., Shandler, R., Jung, J. H., and Lee, T. (2024). “The economy is rigged”: inequality narratives, fairness, and support for redistribution in six countries. Comp. Polit. Stud. doi: 10.1177/00104140241252072

Demasi, C., McCoy, J., and Littvay, L. (2024). Influencing people's populist attitudes with rhetoric and emotions: an online experiment in the United States. Am. Behav. Sci. doi: 10.1177/00027642241240359

Druckman, J. N., and McDermott, R. (2008). Emotion and the framing of risky choice. Polit. Behav. 30, 297–321. doi: 10.1007/s11109-008-9056-y

Eberhardt, W., Brüggen, E., Post, T., and Hoet, C. (2021). Engagement behavior and financial well-being: the effect of message framing in online pension communication. Int. J. Res. Mark. 38, 448–471. doi: 10.1016/j.ijresmar.2020.11.002

Eling, M., Ghavibazoo, O., and Hanewald, K. (2021). Willingness to take financial risks and insurance holdings: a European survey. J. Behav. Exp. Econ. 95:101781. doi: 10.1016/j.socec.2021.101781

Folkman, S., and Lazarus, R. S. (1985). If it changes it must be a process: study of emotion and coping during three stages of a college examination. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 48:150. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.48.1.150

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am. Psychol. 56:218. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218

Gallagher, K. M., and Updegraff, J. A. (2012). Health message framing effects on attitudes, intentions, and behavior: a meta-analytic review. Ann. Behav. Med. 43, 101–116. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9308-7

Gamson, W. A., and Lasch, K. E. (1983). “Social welfare policy,” in Evaluating the Welfare State: Social and Political Perspectives, 397.

Gamson, W. A., and Modigliani, A. (1989). Media discourse and public opinion on nuclear power: a constructionist approach. Am. J. Sociol. 95, 1–37. doi: 10.1086/229213

Gilovich, T. D., and Griffin, D. W. (2010). “Judgment and decision making,” in Handbook of Social Psychology, 5th Edn, eds. S. T. Fiske, D. T. Gilbert, and G. Lindzey (John Wiley & Sons, Inc.), 542–588. doi: 10.1002/9780470561119.socpsy001015

Gottlieb, D., and Mitchell, O. S. (2020). Narrow framing and long-term care insurance. J. Risk Insur. 87, 861–893. doi: 10.1111/jori.12290

Götz, F. M., Gosling, S. D., and Rentfrow, P. J. (2022). Small effects: the indispensable foundation for a cumulative psychological science. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 17, 205–215. doi: 10.1177/1745691620984483

Hayes, A. F. (2009). Beyond Baron and Kenny: statistical mediation analysis in the new Millennium. Commun. Monogr. 76, 408–420. doi: 10.1080/03637750903310360

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Commun. Monogr. 85, 4–40.

Hwang, I. D. (2021). Prospect theory and insurance demand: empirical evidence on the role of loss aversion. J. Behav. Exp. Econ. 95:101764. doi: 10.1016/j.socec.2021.101764

Johnson, R. (2019). What Is the Lifetime Risk of Needing and Receiving Long-Term Services and Supports. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. Available at: https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/migrated_legacy_files//188046/LifetimeRisk.pdf (accessed February 26, 2024).

Johnson, R., and Wang, C. X. (2019). How Many Older Adults Can Afford To Purchase Home Care? Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation.

Kahneman, D., and Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica 47:263. doi: 10.2307/1914185

Keller, P. A., and Lehmann, D. R. (2008). Designing effective health communications: a meta-analysis. J. Public Policy Mark. 27, 117–130. doi: 10.1509/jppm.27.2.117

Krosnick, J. A., Visser, P. S., and Harder, J. (2010). The psychological underpinnings of political behavior. Handb. Soc. Psychol. 2, 1288–1342. doi: 10.1002/9780470561119.socpsy002034

Leeper, T. J., and Slothuus, R. (2020). “How the news media persuades: framing effects and beyond,” in The Oxford Handbook of Electoral Persuasion, Oxford Handbooks, eds. E. Suhay, B. Grofman, and A. H. Trechsel (Oxford Academic). doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190860806.013.4

Leith, K. P., and Baumeister, R. F. (1996). Why do bad moods increase self-defeating behavior? Emotion, risk taking, and self-regulation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 71, 1250–1267. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.71.6.1250

Lerner, J. S., Li, Y., Valdesolo, P., and Kassam, K. S. (2015). Emotion and decision making. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 66, 799–823. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115043

Lifeplans Inc (2017). Who Buys Long-Term Care Insurance Twenty-Five Years of Study of Buyers and Non-Buyers in 2015–2016. Available at: https://www.ahip.org/documents/LifePlans_LTC_2016_1.5.17.pdf (accessed February 26, 2024).

Loewenstein, G. (2000). Emotions in economic theory and economic behavior. Am. Econ. Rev. 90, 426–432. doi: 10.1257/aer.90.2.426

Meyerowitz, B. E., and Chaiken, S. (1987). The effect of message framing on breast self-examination attitudes, intentions, and behavior. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 52:500.

Nabi, R. L., Gustafson, A., and Jensen, R. (2018). Framing climate change: exploring the role of emotion in generating advocacy behavior. Sci. Commun. 40, 442–468. doi: 10.1177/1075547018776019

Nelson, T. E., and Kinder, D. R. (1996). Issue frames and group-centrism in American public opinion. J. Polit. 58, 1055–1078. doi: 10.2307/2960149

O'Keefe, D. J., and Hoeken, H. (2021). Message design choices don't make much difference to persuasiveness and can't be counted on—not even when moderating conditions are specified. Front. Psychol. 12:664160. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.664160

O'Keefe, D. J., and Jensen, J. D. (2007). The relative persuasiveness of gain-framed and loss-framed messages for encouraging disease prevention behaviors: a meta-analytic review. J. Health Commun. 12, 623–644. doi: 10.1080/10810730701615198

O'Keefe, D. J., and Jensen, J. D. (2009). The relative persuasiveness of gain-framed and loss-framed messages for encouraging disease detection behaviors: a meta-analytic review. J. Commun. 59, 296–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2009.01417.x

Pearson, C. F., Quinn, C. C., Loganathan, S., Datta, A. R., Mace, B. B., Grabowski, D. C., et al. (2019). The forgotten middle: many middle-income seniors will have insufficient resources for housing and health care. Health Affairs 38:5233. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05233

Prietzel, T. T. (2020). The effect of emotion on risky decision making in the context of prospect theory: a comprehensive literature review. Manag. Rev. Q. 70, 313–353. doi: 10.1007/s11301-019-00169-2

Primbs, M. A., Pennington, C. R., Lakens, D., Silan, M. A. A., Lieck, D. S. N., Forscher, P. S., et al. (2023). Are small effects the indispensable foundation for a cumulative psychological science? A reply to Götz et al. (2022). Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 18, 508–512. doi: 10.1177/17456916221100420

Rau, J., and Aleccia, J. (2023). Why Long-Term Care Insurance Falls Short for So Many—The New York Times. The New York Times.

Redfoot, D., Feinberg, L., and Houser, A. (2013). The Aging of the Baby Boom and the Growing Care Gap: A Look at Future Declines in the Availability of Family Caregivers. Washington, DC: AARP Public Policy Institute.

Rothman, A. J., Bartels, R. D., Wlaschin, J., and Salovey, P. (2006). The strategic use of gain- and loss-framed messages to promote healthy behavior: how theory can inform practice. J. Commun. 56(suppl_1), S202–S220. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00290.x

Rucker, D. D., Preacher, K. J., Tormala, Z. L., and Petty, R. E. (2011). Mediation analysis in social psychology: current practices and new recommendations. Soc. Pers. Psychol. Compass 5, 359–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00355.x

Rustichini, A. (2005). Emotion and reason in making decisions. Science 310, 1624–1625. doi: 10.1126/science.1122179

Stark, E., and Fedele, J. (2018). 5 Things You Should Know About Long-Term Care Insurance. Washington, DC: AARP Bulletin.

Tversky, A., and Kahneman, D. (1981). The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science 211, 453–458. doi: 10.1126/science.7455683

Wake, S., Wormwood, J., and Satpute, A. B. (2020). The influence of fear on risk taking: a meta-analysis. Cogn. Emot. 34, 1143–1159. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2020.1731428

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., and Carey, G. (1988). Positive and negative affectivity and their relation to anxiety and depressive disorders. J. Abnormal Psychol. 97:346.

Watson, D., and Tellegen, A. (1985). Toward a consensual structure of mood. Psychol. Bull. 98, 219–2 35. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.219

Wilkinson, L. (1999). Statistical methods in psychology journals: guidelines and explanations. Am. Psychol. 54, 594–604. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.54.8.594

Wright, W. F., and Bower, G. H. (1992). Mood effects on subjective probability assessment. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 52, 276–291. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(92)90039-A

Keywords: framing, framing intervention, financial planning, emotions, insurance decisions, anxiety, calmness, decision-making

Citation: Born N, Ashebir S, Brady S, D'Ambrosio L and Coughlin J (2024) The emotional path to influencing decision-making: harnessing emotions for better financial choices. Front. Behav. Econ. 3:1393384. doi: 10.3389/frbhe.2024.1393384

Received: 29 February 2024; Accepted: 26 September 2024;

Published: 06 December 2024.

Edited by:

Thomas Post, Maastricht University, NetherlandsReviewed by:

Adriaan Kalwij, Utrecht University, NetherlandsJudith Avrahami, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel

Inka Eberhardt Hiabu, Copenhagen Business School, Denmark

Copyright © 2024 Born, Ashebir, Brady, D'Ambrosio and Coughlin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nadja Born, bmJvcm5AbWl0LmVkdQ==

Nadja Born

Nadja Born Sophia Ashebir

Sophia Ashebir Samantha Brady

Samantha Brady Lisa D'Ambrosio

Lisa D'Ambrosio Joseph Coughlin

Joseph Coughlin