94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Behav. Econ. , 09 May 2024

Sec. Behavioral Microfoundations

Volume 3 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/frbhe.2024.1385609

This article is part of the Research Topic Psychology of Financial Management View all 11 articles

In countries where Christmas is celebrated, people are under pressure in the pre-Christmas period to spend on gift giving and socializing. In two surveys we investigated the role of the meaning of Christmas and other psychological factors in predicting propensity to spend and to borrow at Christmas (UK, N = 190; Norway, N = 234). Factor analysis identified three components of the meaning of Christmas: financial concerns, indulgence, and social aspects. In both surveys: (1) experienced financial hardship predicted lower propensity to spend and greater propensity to borrow; (2) more proactive money management practices predicted lower propensity to borrow; (3) material values predicted both propensity to spend and propensity to borrow; and (4) seeing Christmas as a time for indulgence, experiencing more negative affect, or less positive affect, predicted greater propensity to spend. Additionally: (1) in the UK survey, participants who said that lately they had been feeling more negative (more angry, sad etc.) had a greater propensity to borrow; and (2) in the Norway survey, an obligation gift motivation predicted propensity to spend. The findings show that in addition to experienced financial hardship and proactive money management practices, the psychological factors of material values, affect, and gift motivation play significant roles in propensity to spend and/or borrow at this time of high pressure. We discuss implications for theory and financial interventions.

In countries where Christmas is celebrated, including the UK and Norway, people are under pressure, in the weeks and months preceding it, to spend on gift giving and socializing (e.g., Belk, 1993). This practice may be unsustainable in many ways, encouraging both overconsumption of resources and overspending of money. Christmas spending may be accomplished with existing resources, or by using credit facilities such as credit cards or personal loans. The Deloitte (2018) Christmas survey found that British people intended to spend the most out of the European countries surveyed that year, 38.6 percent more than the European average, and their reported actual spending in 2018 was 41.4 percent above the European average (Deloitte, 2019). Virke, the Federation of Norwegian Enterprise, estimated that Norwegians would use NOK 12,500 more in December 2023 than in the rest of the year because of Christmas related shopping (Virke, 2023), which represents 27 percent higher sales for retailers than in the rest of the year. According to a survey conducted by the Norwegian debt collection agency, Lindorff, in 2019, one out of three respondents say they spend more than they can afford on Christmas shopping (Intrum, 2019).

The broad aim of our research is to understand the recurrent social and emotional pressures that people experience when making financial decisions and how these pressures affect behavioral intentions at a time of high expense such as the pre-Christmas period, potentially creating or exacerbating financial hardship post-Christmas. In particular, we aim to identify key psychological predictors of propensity to spend and borrow at this time of high pressure, over and above demographic and practical financial variables.

We present the findings from two surveys conducted before Christmas, one in the UK (N = 190) and the other in Norway (N = 234). The UK pre-Christmas survey was part of a more extensive UK project that was preceded by an interview study and followed by a post-Christmas survey1. The interview study (N = 20) was designed and conducted according to an adapted mental models protocol (Morgan et al., 2002; Downs et al., 2008) with the aim of characterizing people's mental models about Christmas and related financial matters. Some of the findings are reported in McNair et al. (2015), and others of concern to this study are reported in Appendix 1. The interviews were used to construct scale items in respondents' own words for the pre-Christmas surveys presented here. The final scales assessed three aspects of what Christmas means to people (financial concerns, indulgence, and social) and two outcome variables, propensity to spend, and propensity to borrow at Christmas (see below and Appendix 1). Similar to the present study, the post-Christmas survey aimed to identify significant psychological predictors of reported spending and borrowing behavior at Christmas after controlling for demographic and practical financial variables. As McNair et al. (2016) report, the main findings were that external locus of control and spendthrift tendency were associated with reported spending, and external locus of control, emotional coping style and denial coping style were associated with reported borrowing behavior.

The results of the UK pre-Christmas survey we report here complement the results reported in McNair et al. (2016) by investigating propensity to spend and borrow, assessed before Christmas, and by investigating different psychological predictors. To achieve this substantive aim, the survey's methodological aim was to construct, and assess the psychometric properties of, new scales to measure the three aspects of the meaning of Christmas, propensity to spend, and propensity to borrow at Christmas. The Norway pre-Christmas survey was conducted to assess the external validity of the UK survey findings, in particular, by evaluating the above-mentioned scales, and to assess the robustness of the psychological predictors of propensity to spend and borrow at Christmas identified in the UK survey. In addition, the Norway survey investigated the role of another potentially important psychological predictor, gift motivation.

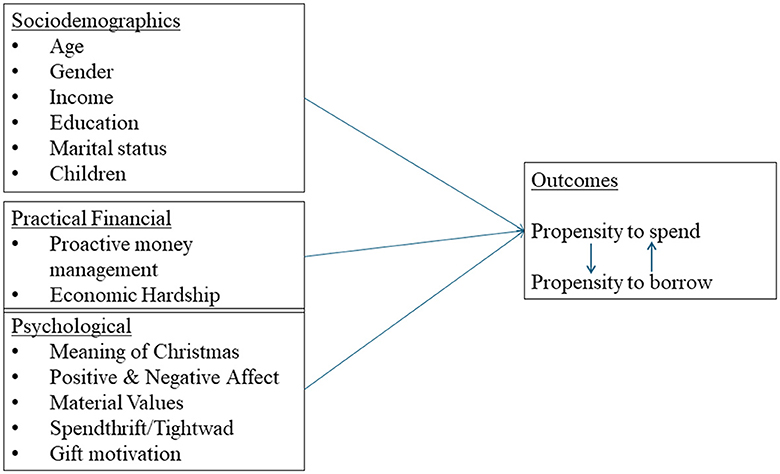

Figure 1 presents the theoretical framework underlying the research presented. The boxes to the left present the three sets of predictors (sociodemographic, practical financial, and psychological) of the outcome variables (propensity to spend, and propensity to borrow at Christmas) in the box to the right of the figure.

Figure 1. Sociodemographic, practical financial and psychological predictors of outcome variables propensity to spend and propensity to borrow at Christmas.

Clearly, certain demographic variables, including age, gender, and family composition, are likely to be significant predictors of propensity to spend and borrow at Christmas (Allgood and Walstad, 2013; Davies et al., 2019) as well as practical financial variables such as economic hardship and money management practices. Economic hardship has been assessed by various indicators, including insufficient income to meet basic needs, expenditure cutbacks and failing to meet on-going financial commitments such as rent, utility bills, mortgage or consumer credit repayments (Loibl, 2017; Bourova et al., 2019). We expect the experience of economic hardship to be associated with lower propensity to spend and higher propensity to borrow, since borrowing and cutting back on expenditure are frequently observed means of coping with economic hardship (Silinskas et al., 2021). In addition, we expect people who manage their finances more proactively to have lower propensity to spend and borrow, since previous research has found such associations with respect to spending and borrowing (Garðarsdóttir and Dittmar, 2012).

However, our main research questions concern the extent to which certain psychological variables are significant predictors of propensity to spend at Christmas and propensity to borrow at Christmas, after controlling for demographic and practical financial factors. First, as mentioned, we explore the extent to which aspects of the meaning of Christmas predict these variables. Although the influence of the meaning of Christmas on propensity to spend and borrow at Christmas has not previously been investigated, we speculated that financial concerns might be negatively associated with propensity to spend and positively associated with propensity to borrow, while Christmas as a time of indulgence and socializing might be associated positively with both propensity to spend and to borrow.

We also investigate the relationship between certain other psychological variables and propensity to spend and borrow at Christmas. Ideally, consumers should manage Christmas spending in a rational way, and make spending decisions based on a budget that takes future income and expenses into account, thereby maximizing goal achievements within the set budget. However, given the high pressure to spend at Christmas, the emotional stress involved (Sherry et al., 1993; McNair et al., 2016) and the changes in consumption patterns around Christmas (Phillips et al., 2004) there is reason to expect that psychological factors may have considerable impact on spending decisions, such that people spend more than an economic model based on rational decision makers would predict. We therefore investigate the extent to which four psychological variables, that previous research has identified as being associated with spending and borrowing, predict the propensity to spend and borrow at Christmas: material values (Garðarsdóttir and Dittmar, 2012); the spendthrift-tightwad dimension (Rick et al., 2008); positive and negative affect (Watson et al., 1988); and three facets of gift motivation (Wolfinbarger and Yale, 1993).

With respect to material values (Richins and Dawson, 1992), several previous studies have looked at the value that a consumer places on the acquisition and possession of material goods in Christmas celebrations. Belk (1993) described how materialism and commercialism have steadily become more salient characteristics of Christmas celebrations so that consumption, through gift giving, social events and decoration, has become a key ingredient. Gift giving is a Christmas ritual associated with the building and strengthening of social relationships, which brings many consumers happiness (Givi et al., 2023). However, research has also shown that gift giving may have a dark side and cause anxiety (Sherry et al., 1993). For example, Wooten (2000) found that many consumers see gift giving as a form of identity presentation and worry about how their gifts will be perceived by the receivers, which in turn may lead to overspending on gifts. Otnes et al. (1993) found that some receivers are perceived as “difficult” and may cause gift givers to fear embarrassment if they fail to fulfill their expectations. This may also cause gift givers to overspend. It is likely that worries about the receivers' reactions to a gift may be stronger among materialistic consumers.

Building on the research of Garðarsdóttir and Dittmar (2012), who found material values to predict overspending and debt levels, and of Watson (2003) who found that highly materialistic people were more likely to see themselves as spenders and have positive attitudes toward borrowing, we investigate whether material values also predict the propensity to spend and borrow at Christmas. In line with these findings, we expect higher scores on material values to be associated with higher propensity to spend and higher propensity to borrow at Christmas.

The tightwad-spendthrift dimension, which was introduced by Rick et al. (2008) expresses an individual's feeling of pleasure or pain while spending and was found to heavily influence spending and credit behavior. Tightwads typically spend less than they would like in order to avoid the pain of paying. Spendthrifts, on the other hand, don't feel the same pain while paying, and typically spend more than they ideally would prefer to spend and are more likely to use credit. Although the tightwad-spendthrift dimension has not been linked to spending and borrowing at Christmas in previous research except in McNair et al. (2016), we include it here since it may be a factor that may strengthen or reduce the expected effect of materialism (Nepomuceno and Laroche, 2015). We expect tightwaddism to predict lower propensity to spend and borrow at Christmas, while spendthriftiness will have the opposite effect.

With respect to affect, previous research has shown that Christmas celebrations may be both positively and negatively associated with affective wellbeing. For example, Kasser and Sheldon (2002) and Mutz (2016) found that Christmas celebrations based on material values are negatively related to wellbeing. This is in line with the findings from the meta-analysis of Dittmar et al. (2014) that materialism is associated with lower levels of positive affect and higher levels of negative affect and anxiety. The tradition of exchanging gifts at Christmas may also affect emotions, both in a positive (e.g., Pillai and Krishnakumar, 2019) and negative (e.g., Sherry et al., 1993) way. Finally, previous research shows that Christmas celebrations, for some, may have a negative impact on physical (e.g., Keatinge and Donaldson, 2004) as well as mental health (Velamoor et al., 1999; Bergen and Hawton, 2007). Hence, there is likely to be high variation in emotions between consumers at Christmas time, and mood may influence both spending and borrowing decisions. In this study, we test whether affect is related to the propensity to spend and borrow at Christmas, although we do not propose a clear direction of the relationship. On the one hand, research has shown that a decrease in negative, or increase in positive, mood may be associated with increased spending (e.g., Murray et al., 2010; Agarwal et al., 2020). On the other hand, Kasser and Sheldon (2002) found that people who reported that spending was a relatively salient experience at Christmas, reported lower Christmas wellbeing and more negative affect. Related to this, Atalay and Meloy (2011) and Park et al. (2022) report a retail therapy effect: more negative affect, or less positive affect, are significantly related to greater intention to spend.

Turning to gift motivation, for many consumers a large part of the spending associated with Christmas celebration is related to gift exchange. Previous research has found that individuals have different motivations when they buy Christmas gifts (Wolfinbarger and Yale, 1993), and the motivation may influence their subsequent choices regarding amount spent and brand choices (Givi et al., 2023). The motive to give gifts may be to make the receiver happy or better off (altruistic motivation) or it may be a strategic use of the reciprocity norm or to present oneself in a favorable manner (egoistic motivation) (e.g., Sherry, 1983). Some studies also suggest that there is variation in the willingness to give a gift, and that many gifts are given because of obligation, driven by compliance with social norms (Goodwin et al., 1990).

Few studies have focused on the link between gift motivation and spending. Wooten (2000) found that some situations, such as the presence of other people when gifts are exchanged, may lead to higher spending on gifts. People have also been found to spend more on gifts for more affluent recipients (Reshadi and Givi, 2023) while Webley et al. (1983) found that people may spend considerably more when they give cash sums rather than in-kind gifts. No studies have yet looked at the link between gift motivation and total spending. In this study, we use the three gift motivation dimensions (obligation, enjoyment, and practicality) identified by Wolfinbarger and Yale (1993) and expect stronger motives to be positively related to propensity to spend and propensity to borrow.

The substantive aim of this research is to address four research questions within a hierarchical regression framework. This framework, presented in Figure 1, enables us to identify the independent contribution of each predictor, as well as the additional contribution of groups of predictors, after controlling for the effects of others. We separately analyze predictors of each outcome variable, propensity to spend and propensity to borrow at Christmas. At the first step of analysis we include only sociodemographic predictors, at the second step we add practical financial variables, and at the third step we add the psychological predictors. Since the two outcome variables may be correlated, as an additional control we address the question of whether propensity to borrow is a predictor of propensity to spend, and vice versa, at the fourth step of the analysis. We expect each of these outcome variables to be a significant predictor of the other, since borrowing facilitates spending, and spending can lead to borrowing. In summary then, each regression analysis comprises four steps which correspond to the research questions stated below.

1. Do sociodemographic factors predict propensity to spend and borrow significantly, and if so which ones?

2. Controlling for sociodemographic factors, does the addition of practical financial variables significantly increase the variance of propensity to spend and borrow accounted for, and which of these predictors are significant?

3. Controlling for sociodemographic and practical financial variables, does the addition of psychological variables significantly increase the variance of propensity to spend and borrow accounted for, and which of these predictors are significant?

4. Controlling for all other variables, does the addition of propensity to borrow significantly increase the variance in propensity to spend accounted for, and vice versa, and if so, what changes occur in the effects of the other predictors?

We should note here that hierarchical multiple regression is essentially a correlational model that identifies significant associations between predictor and outcome variables. A predictor may be an antecedent cause of variation in the outcome variable, or alternatively, the association may be caused by other variables, or even, the outcome variable may be an antecedent cause of the predictor (see Tabachnick and Fidell, 2007). Our grouping of predictors in a hierarchy, from sociodemographic, to practical financial, to psychological, serves to address the question of whether the addition of the second and third categories of predictors at the relevant steps of analysis significantly increases the proportion of variance of the outcome variables accounted for by those variables. In exploratory research such as ours, the power of hierarchical linear regression is that predictors can be identified that are significant predictors after controlling for variation in other key variables. The findings are then interpreted in terms of causal models which must be further investigated. To propose or test such models in advance of our data collection here would have been premature, since we do not have sufficient prior knowledge to identify plausible models. Nevertheless, the identification of significant associations is an important contribution of itself toward understanding propensity to spend and borrow at Christmas. The causal nature, or otherwise, of predictors is considered in the Discussion Section.

Participants were recruited via notices placed around Leeds in libraries (on campus and off), council buildings, and community centers in north, south, west, and east Leeds. The survey was also announced at local debt forum meetings. Eligible participants were over 18 years old and indicated that they celebrated Christmas. Both online and paper-based versions of the survey were offered. N = 190 participant completed the survey in the pre-Christmas period of 2013 (n = 154 online, n = 36 paper): mean age 40 years; 64% were female; 55% had a partner; 60% had children; 65% were degree-educated; and 58% had a monthly income >£1,000. Respondents received £10 remuneration. The main difference between the online and paper version participants was a greater proportion of higher degrees in the former subgroup (see Appendix 2).

The pre-Christmas survey questionnaire comprised the following sections: (1) items to assess propensity to spend, propensity to borrow and meaning of Christmas (see Appendix 1); (2) the sociodemographic questions listed above; (3) scale items to assess the practical financial factors of economic hardship and proactive money management practices; and (4) scales to assess the psychological factors of material values, tightwad/spendthrift and positive and negative affect.

Participants, who were over 18 years old, completed an online survey in the pre-Christmas period of 2016 (N = 234). Sixty seven percent were recruited via a Facebook post in which individuals older than 18 years were asked to take part, and the rest by directly approaching train passengers and people waiting for their flights in an airport. Sample characteristics were as follows: mean age 42 years; 74% female; 53% had a partner; 36% had children; 53% were degree-educated; and 59% had a monthly net income >45,000 NOK.

The UK pre-Christmas questionnaire was adapted and translated into Norwegian. The Norwegian questionnaire comprised the same scales as the UK survey, with three differences. Economic hardship was assessed via two items, asking whether participants could afford a large expense, and whether they had financial problems. Spendthrift-tightwad was measured by two rather than four of the original items (Rick et al., 2008). In addition, we added the scale developed by Wolfinbarger and Yale (1993) which assesses three facets of gift motivation.

The scales to assess predictor and outcome variables are described below. Their descriptive statistics for the UK and Norway surveys are presented in Appendix Table A3.1 and Table A3.2. Details of the construction and evaluation of the scales for the Meaning of Christmas predictors and the two outcome variables are presented in the Results section. The first two scales described are the outcome variables.

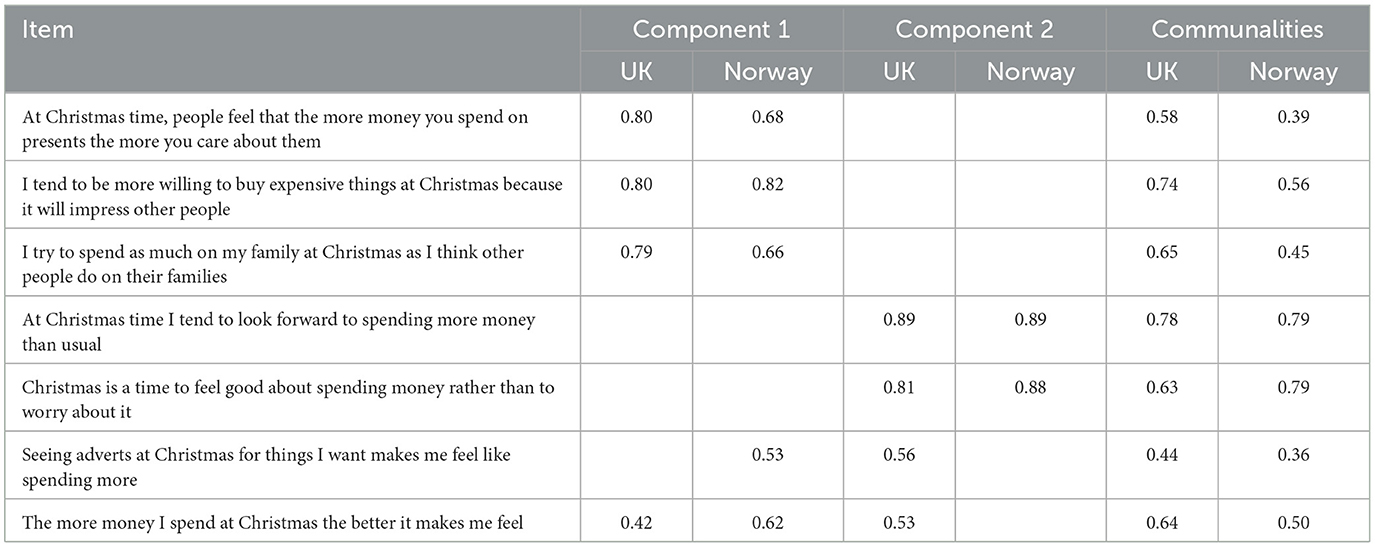

This scale comprised the seven items presented in Table 1, including “At Christmas time, people feel that the more money you spend on presents the more you care about them.” Respondents indicated on a Likert scale from 1 “strongly disagree” to 5 “strongly agree” the extent to which the statement truly reflected how they felt (Cronbach's alpha: UK = 0.81, Norway = 0.73).

Table 1. Factor loadings from principal components analysis of the seven-item propensity to spend scale, UK and Norway surveys.

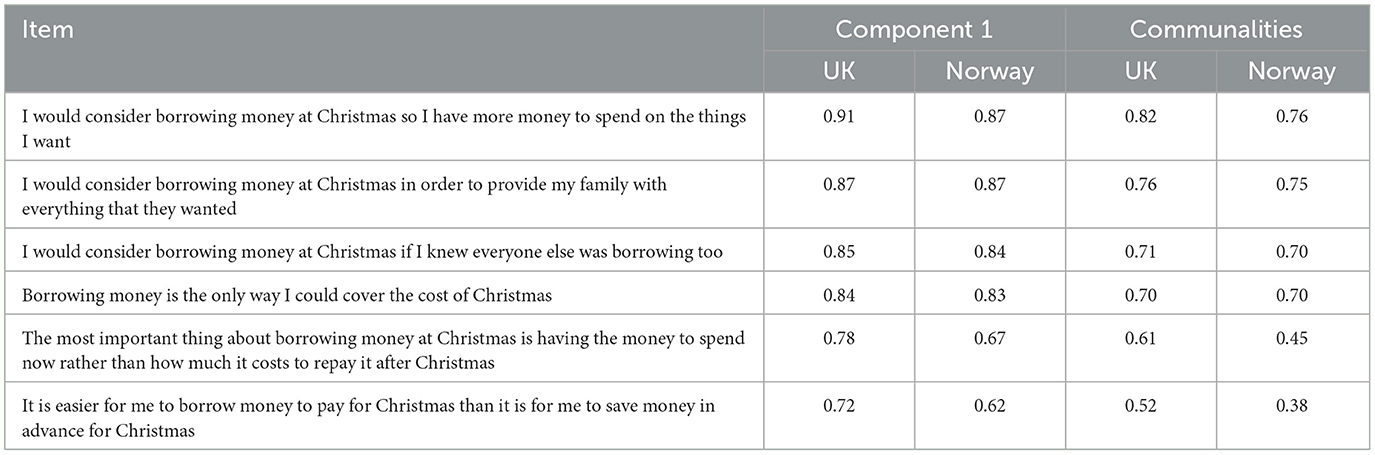

This scale comprised the six items presented in Table 2, including “I would consider borrowing money at Christmas so I have more money to spend on the things I want.” Respondents indicated on a Likert scale from 1 “strongly disagree” to 5 “strongly agree” the extent to which the statement truly reflected how they felt (Cronbach's alpha: UK = 0.91, Norway = 0.86).

Table 2. Factor loadings from the principal components analysis of the six-item propensity to borrow scale, UK and Norway surveys.

The next two scales assess practical financial predictors.

A 12-item scale (Lempers et al., 1989) to assess the degree of financial cutbacks one has had to make in the past 3 months. Each item represents a different area of everyday spending, with respondents indicating from 1 (“I've never done this”) to 5 (“I've very often done this”) the extent of the cutbacks they've made in that area. Items cover spending on socializing, food shopping, eating habits and healthcare (UK survey only, Cronbach's alpha = 0.87).

A 9-item scale (Garðarsdóttir and Dittmar, 2012) to assess the tendency for people to be proactive in managing their financial lives, covering a range of basic, everyday financial management practices, and subjective perceptions of one's current financial state (Cronbach's alpha: UK = 0.92, Norway = 0.81).

Finally, the next five scales assess ten psychological predictors, including three aspects of the meaning of Christmas, positive and negative affect and three facets of gift motivation.

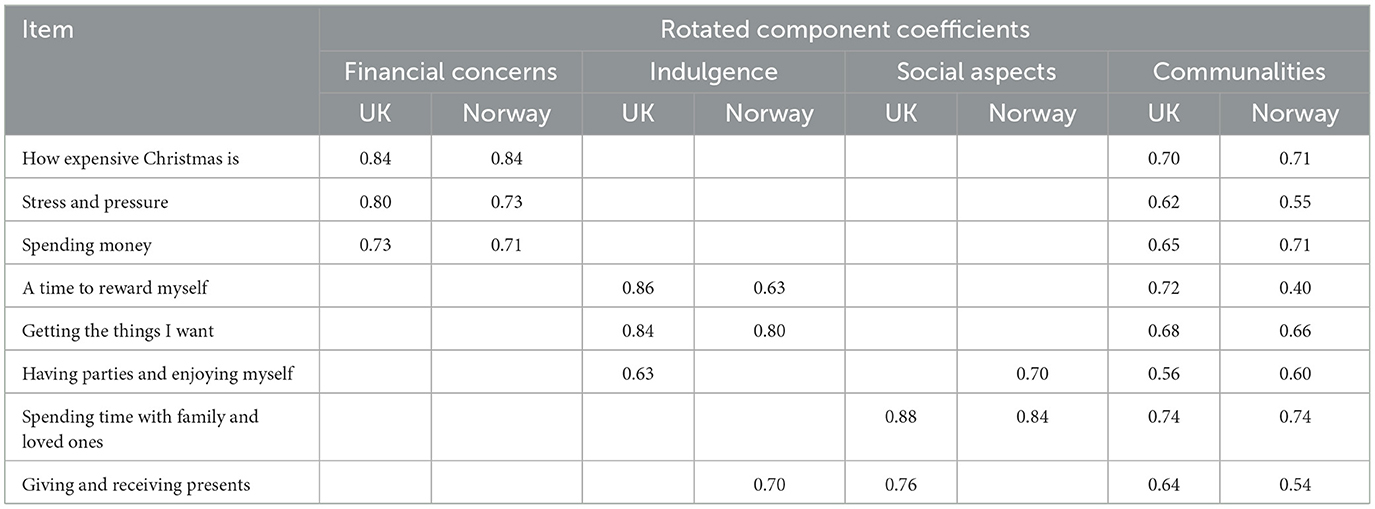

This was assessed via the eight statements presented in Table 3. Statements were preceded by “When I think about what Christmas means to me I think about … [for example] Giving and receiving presents.” Possible responses were on a Likert scale from 1 “Never” to 5 “Always.” Three subscales were identified:

Table 3. Factor loadings from principal components analysis of the meaning of Christmas items, UK and Norway surveys.

Financial concerns, 3 items, including “How expensive Christmas is” (Cronbach's alpha: UK = 0.71, Norway = 0.48);

Indulgence, 3 items including “A time to reward myself” (Cronbach's alpha: UK = 0.70, Norway = 0.0.55);

Social aspects, 2 items, including “Spending time with family & loved ones” (Cronbach's alpha: UK = 0.60, Norway = 0.32).

Eight items from the material values scale (Richins and Dawson, 1992) were adapted to refer more specifically to Christmas. Items ask about the pleasure one derives from purchasing material goods, as well as the status one ascribes to such goods (Cronbach's alpha: UK = 0.75, Norway = 0.77).

A 4-item scale (Rick et al., 2008) to assess the extent of the psychological “pain of paying” people experience when making purchases. Scale items ask directly about how the ease or difficulty with which people find themselves spending money in consumer contexts. Higher scores indicated more “Spendthrift” tendencies (UK only, Cronbach's alpha = 0.74. In the Norway survey this was assessed with just two items).

A 20-item scale (Watson et al., 1988) to measure current levels of positive and negative mood. Each item presents a different emotion, with respondents indicating how much they have felt that way in the past month using a 1 (“Not at all”) to 5 (“Extremely”) Likert scale. (Cronbach's alpha: positive affect UK = 0.91, Norway = 0.87; negative affect UK = 0.92, Norway = 0.89).

A 14-item scale (Wolfinbarger and Yale, 1993) to measure the three facets enjoyment, obligation, and practicality. Each item presents a statement about motivation for giving gifts, with respondents indicating how much they agree or disagree with the statement using a 1 (“Strongly disagree”) to 7 (“Strongly agree”) Likert scale. Sample items are “It is important to me to choose a unique gift” (enjoyment motivation), “I often feel obliged to give gifts” (obligation motivation), and “I feel it is especially important to give gifts that are useful to the receiver” (practical motivation), [Norwegian survey only, Cronbach's alpha: 0.78 (enjoyment motivation), 0.79 (obligation motive), and 0.72 (practical motivation), respectively].

In both surveys, items derived from the UK interview study to assess propensity to spend and borrow and the meaning of Christmas (see Appendix 1) were subjected to a correlational analysis which was followed by principal components analysis (PCA). In the next subsections the results for the UK survey are given first, followed by those for the Norwegian survey.

The results of the analysis of the eight items to assess propensity to spend at Christmas were similar for both surveys. First, one item, whose inter-item correlations were all < 0.3, was excluded from further analysis. As we expected this scale to represent a unidimensional construct, analysis of the remaining seven items proceeded as PCA with direct oblimin rotation. The PCAs yielded overall Keiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) statistics of 0.82 and 0.72, with all individual KMOs >0.6. Bartlett's Test of Sphericity was significant at χ2 (21) = 411.37 and 283.53, p < 0.001. The analysis found two factors with Eigen values >1, cumulatively accounting for 63% and 56% of total variance. Table 1 presents factor loadings and communalities for these PCAs. Further inspection of the results indicated both components to be moderately correlated at r = 0.43 and 0.33, suggesting that oblimin rotation was adequate (Tabachnick and Fidell, 2007). Furthermore, the decision was taken to collapse the components, and a single component-based score computed on this basis. Cronbach's alphas were 0.81 and 0.73.

Again, the results were similar in both surveys. For the eight items assessing propensity to borrow at Christmas, initial analysis identified no items with all inter-item correlations < 0.3. One item yielded negative correlations with all but one of the others and was therefore reverse-coded. In the UK survey, PCA with direct oblimin rotation was applied to these eight items on the expectation that the scale would best be represented as a singular score. The PCAs found that one item yielded an individual KMO of < 0.5, rendering it unsuitable for PCA. In dropping this item, another subsequently yielded no correlations >0.3, thus also rendering it unsuitable for PCA. The PCAs report here were thus conducted on the remaining six items. Bartlett's Test of Sphericity was significant at χ2 (15) = 716.90, and 290.88, p < 0.001, and the overall KMOs were 0.80 and 0.85. Results of both surveys indicated a single factor with Eigen value >1, accounting for 69% and 62% of total variance. A component-based score was computed based on these six items. Table 2 presents factor loadings and communalities for these PCAs. Cronbach's alphas were 0.91 and 0.86.

In both surveys, initial analysis of the ten items assessing the meaning of Christmas identified two items with no inter-item correlations >0.3 in both surveys. Another two with low inter-item correlations were present in the Norway survey but retained to give comparability with the UK survey. PCA with varimax rotation2 was applied to the remaining eight items. These yielded overall KMO statistics of 0.66 and 0.61, with individual KMOs for all eight items >0.6. Bartlett's Test of Sphericity was significant at χ2 (28) = 290.88 and 274.74, p < 0.001. In the UK survey, the PCA identified three components with Eigenvalues >1 and in the Norway survey four such components were identified. For consistency across surveys the Norway PCA was rerun with three components specified. The three component analyses cumulatively accounted for 66% and 61% of total variance and yielded simple structure.

Factor loadings, and communalities are presented in Table 3. Three component-based scores were computed for each survey. The first, financial concern, comprised three items and was common to both surveys. However, as Table 3 shows, the second and third factors had some differences across surveys. The second component, indulgence, comprised three items, two of which were common to both surveys. The third component, with two items, was social aspects, which comprised one item common to both surveys, and one different. As the table shows, while UK participants associated having parties and enjoying themselves with getting what they want and rewarding themselves, Norwegians related it more to spending time with family. Norwegians, on the other hand, relate giving and receiving presents to rewarding oneself, while UK participants associated this factor more to spending time with family. These differences may be due to different traditions with respect to Christmas parties and gift exchange across the two countries. We retained the common descriptors, i.e., indulgence and social aspects, because they capture the dominant theme of the items as a whole in both surveys. Cronbach's alphas for the three component-based scores were: financial concerns, 0.71 and 0.48; indulgence, 0.70 and 0.55; and social aspects, 0.60 and 0.32 respectively.

The pre-Christmas propensity to spend and propensity to borrow measures had significant moderate correlations with post-Christmas reported spending and borrowing by the subsample (n = 135) who completed the UK post-Christmas questionnaire: Propensity to spend with reported amount spent, r = 0.15, p < 0.05; Propensity to borrow with reported borrowed/not borrowed, r = 0.18, p < 0.05; Propensity to borrow with reported amount borrowed, r = 0.49, p < 0.005, n = 33).

Appendix Tables A4.1, A4.2 present the bivariate correlations between sociodemographic, practical financial and psychological variables for the UK and Norwegian surveys respectively. The tables show that in both surveys the two outcome variables for the regression analyses described below, propensity to spend at Christmas and propensity to borrow at Christmas, are significantly and quite strongly correlated (UK, r = 0.39; Norway, r = 0.41; p < 0.001). In addition, there are variables in each of the predictor categories that are significantly correlated with both outcome variables. However, there are differences in which variables correlate significantly with each outcome variable. For example, in the UK, whereas gender and number of children, but not age, are significantly correlated with propensity to borrow, only age is significantly associated with propensity to spend.

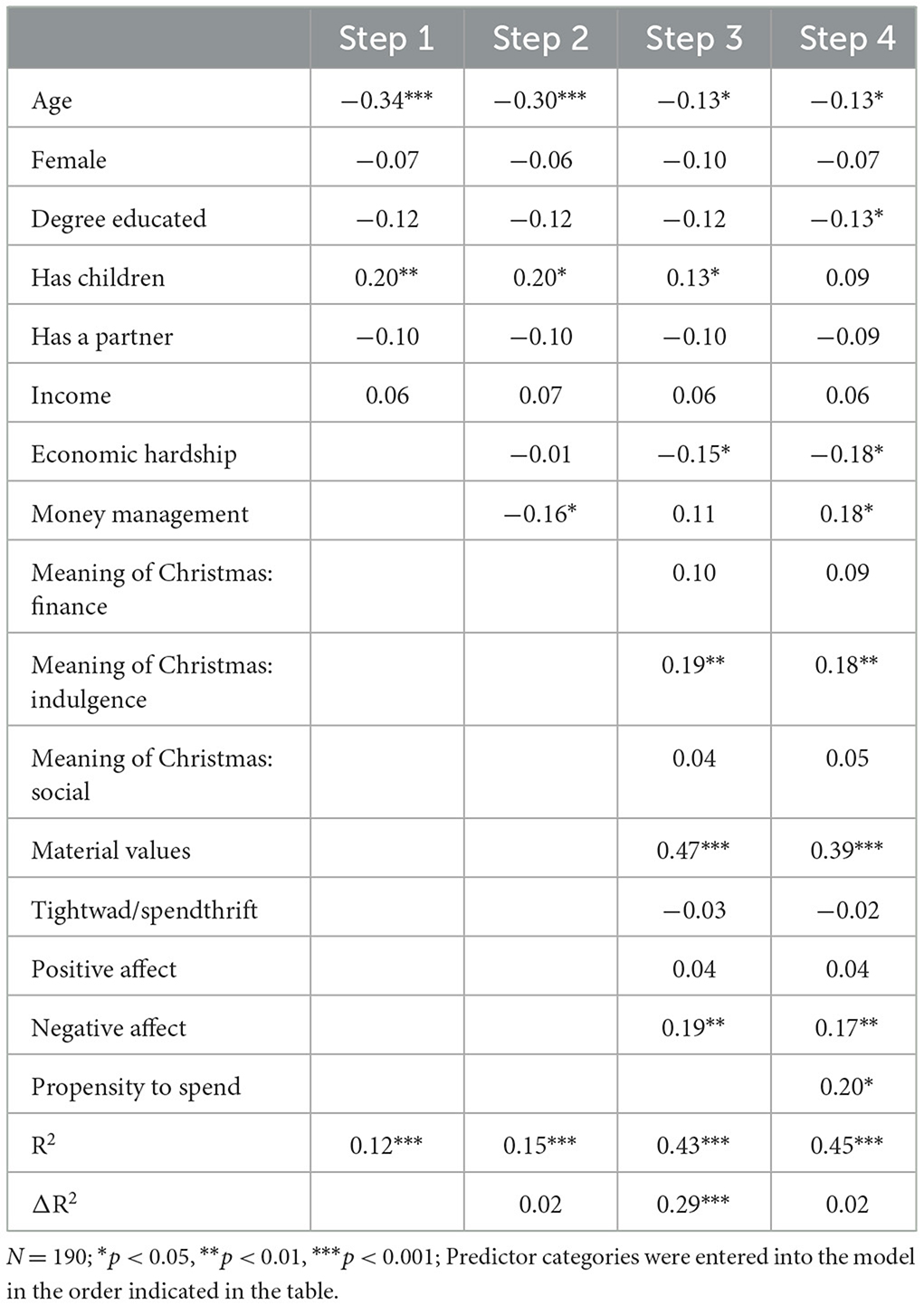

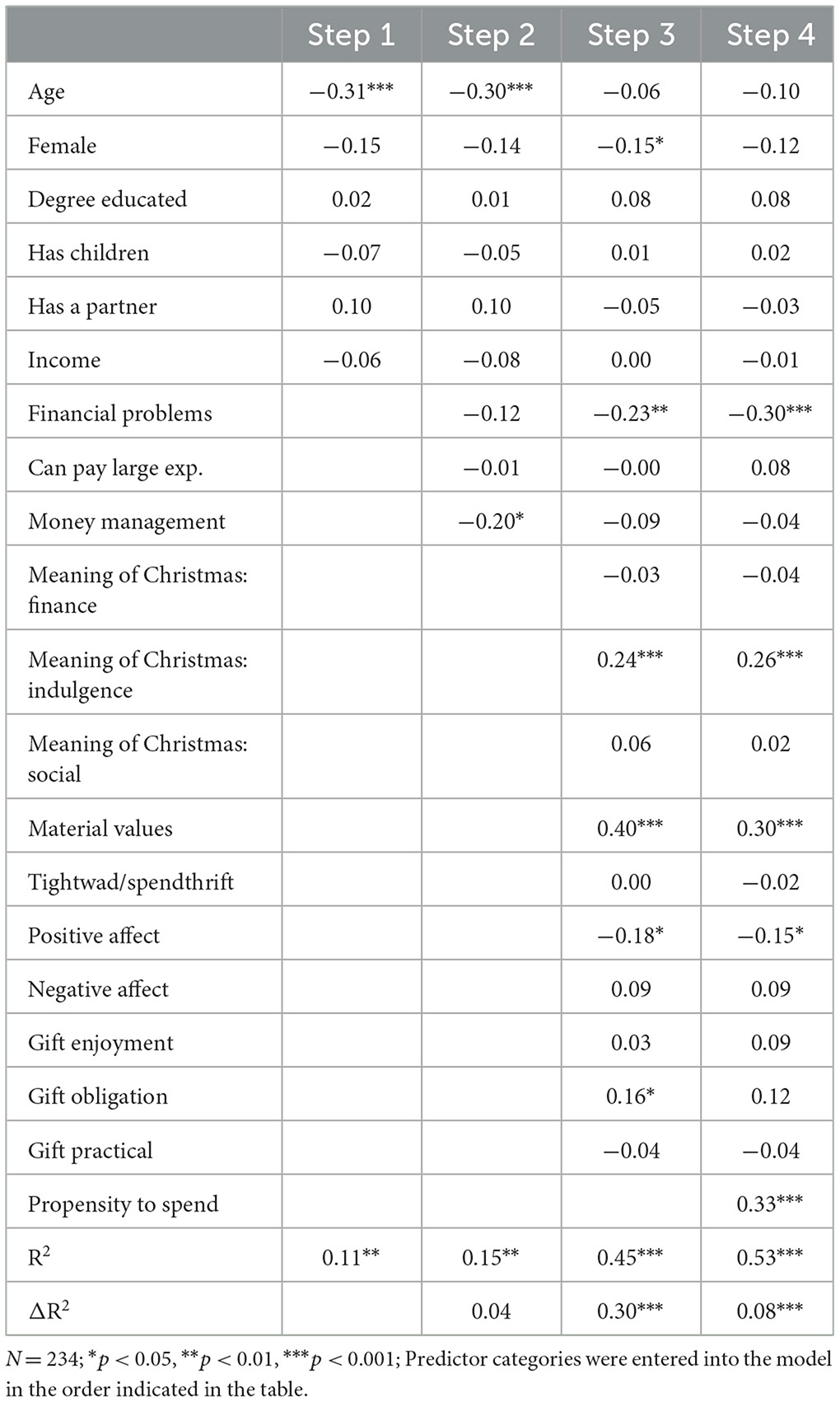

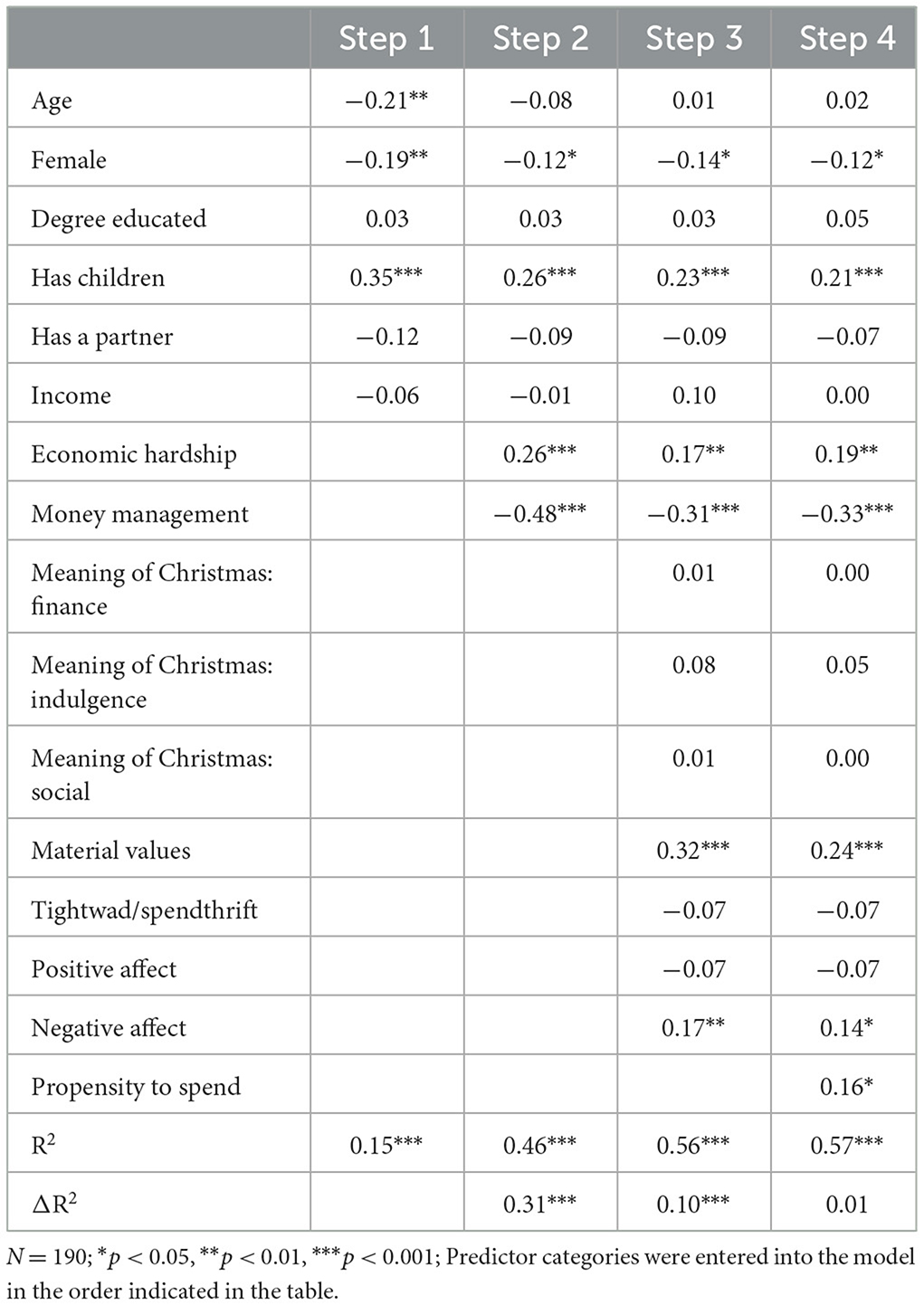

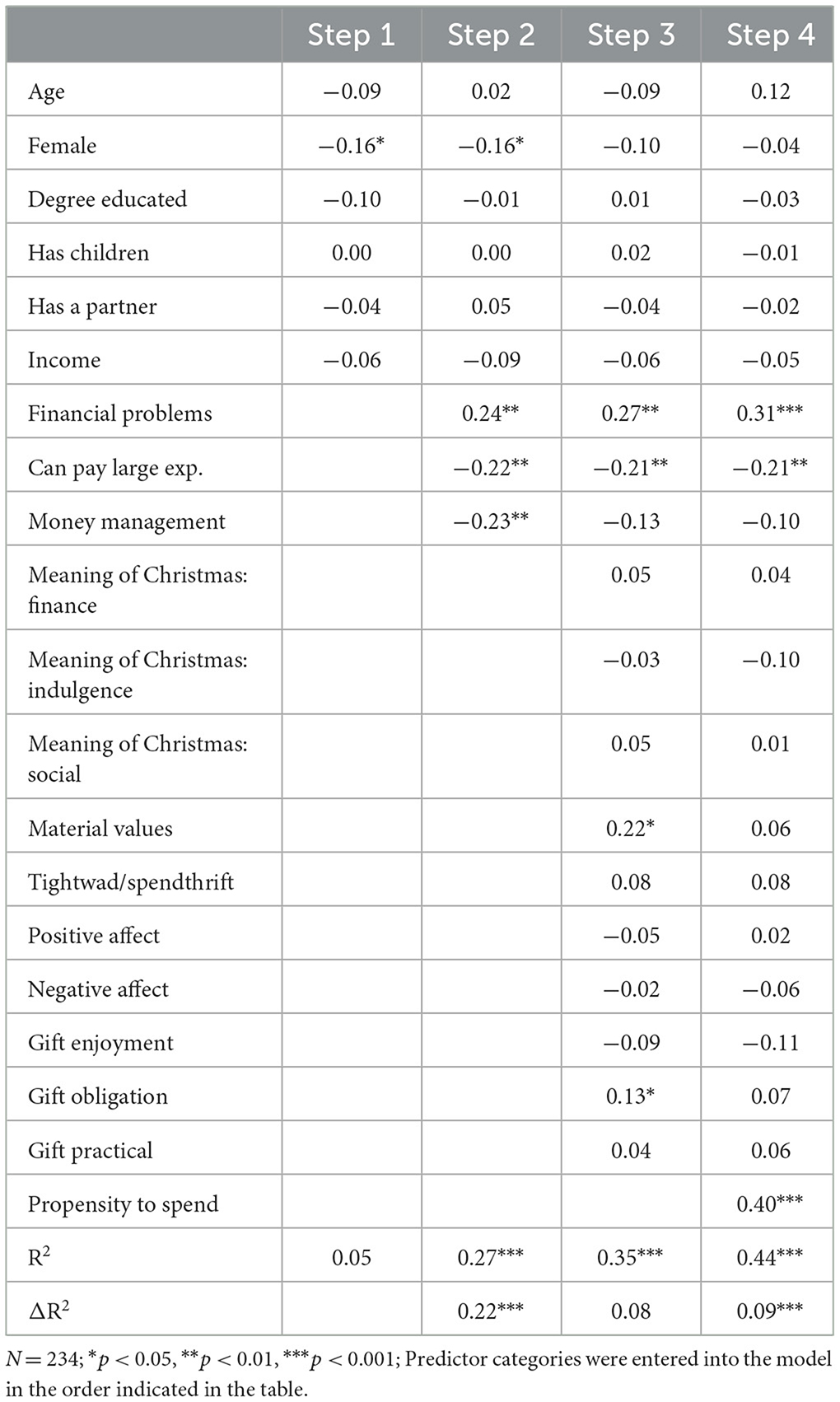

As mentioned earlier, hierarchical regression analyses for each outcome variable, propensity to spend and propensity to borrow, were conducted for each survey separately. The sociodemographic predictors were entered in the first step, followed in the second by the two practical financial factors, economic hardship and proactive money management, with the remaining psychological factors being entered in the third step. As a final control since the two outcome variables were correlated, at a fourth step propensity to borrow was added as a predictor of propensity to spend, and vice versa. Tables 4–7 present the standardized regression coefficients, proportions of variance (R2), and changes in proportion of variance (ΔR2) at each step.

Table 4. UK Survey: hierarchical regression models for propensity to spend: standardized regression coefficients, proportion of variance (R2), and change in proportion of variance (ΔR2) at each step.

For the analyses of propensity to spend (Tables 4, 5) a similar, significant proportion of variance was accounted for by sociodemographic variables at the first step of the UK and Norway surveys, just over 10 percent. Propensity to spend decreased significantly with age in both surveys, while in the UK, it increased significantly with number of children. However, after practical financial and psychological variables were included in subsequent steps of analysis, these effects were rather smaller. On the other hand, a small effect of level of education was significant at the fourth step of the UK analysis.

Table 5. Norway survey: hierarchical regression models for propensity to spend: standardized regression coefficients, proportion of variance (R2), and change in proportion of variance (ΔR2) at each step.

At step 2, the increase in proportion of variance predicted by the practical financial factors was not significant in either survey, although in both surveys propensity to spend decreased slightly but significantly as proactive money management increased. However, this effect was smaller and not significant by the fourth step of the Norway survey, while at the same step in the UK survey greater economic hardship was significantly associated with lower propensity to spend.

In contrast to step 2 of the analyses, the addition of the psychological variables at step 3 led to a large and significant increase in the proportion of variance accounted for, about thirty percent of variance in both surveys. Christmas as indulgence and material values had significant effects on propensity to spend in both surveys. In addition, in the UK survey, more negative affect was associated with higher propensity to spend, and in the Norway survey lower positive affect and higher obligation gift motivation were significantly associated with higher propensity to spend. However, at the fourth step of the Norway survey, the effect of the obligation gift motivation was smaller and non-significant.

Finally, at step 4 the addition of propensity to borrow at Christmas increased the proportion of variance accounted for in propensity to spend at Christmas by a significant amount in the Norway survey, but only by a small non-significant percentage in the UK survey. Nevertheless, in both surveys propensity to borrow had a significant effect. The other main change at step 4 was that the effect sizes of most other significant predictors were smaller than at step 3.

Turning to the analysis of propensity to borrow, the effects of sociodemographic factors were rather different across surveys. Table 6 shows that in step 1 of the UK survey they accounted for a small and significant proportion of variance, whereas for the Norway survey (Table 7) the proportion was yet smaller and not significant. With respect to predictors, the main difference between the two analyses was that in the UK survey age and number of children were strongly associated with it, whereas in the Norway survey they were not. In both surveys, however, gender had a significant effect, with males having greater propensity to borrow.

Table 6. UK survey hierarchical regression models for propensity to borrow: standardized regression coefficients, proportion of variance (R2), and change in proportion of variance (ΔR2) at each step.

Table 7. Norway survey: hierarchical regression models for propensity to borrow: standardized regression coefficients, proportion of variance (R2), and change in proportion of variance (ΔR2) at each step.

In contrast to step 1, at the second step of both analyses a moderately large proportion of variance was accounted for by the practical financial variables, with greater financial hardship and less proactive money management being quite strongly related to greater propensity to borrow.

The addition of psychological variables at step 3 increased the proportion of variance accounted for in propensity to borrow by a significant 10 percent in the UK survey, and a non-significant 8 percent in the Norway survey. In the UK survey, the significant effects of gender, number of children, economic hardship and proactive money management remained, together with two psychological variables, material values and negative affect. In the Norway survey, the two economic hardship indicators also remained significant, together with two psychological variables, material values and an obligation gift motivation.

Finally, at step 4 of the UK survey, although overall variance accounted for hardly changed, propensity to spend was a significant predictor of propensity to borrow, together with all the variables that were significant at step 3. In contrast, in the Norway survey propensity to borrow had a large effect that increased proportion of variance accounted for by a significant 9 percent. The effect sizes of other predictors were reduced, with only the two economic hardship indicators remaining significant.

Our first research question asked whether sociodemographic variables predict propensity to spend and borrow at Christmas, and if so, which ones. As we saw, significant effects of age, number of children, gender, and level of education were observed, although most of these were not significant after practical financial and psychological variables were included. At the first step of the regression analysis of both surveys, higher propensity to spend and borrow were significantly associated with lower age, although the only significant effect at the third and fourth step was that in the UK survey, younger adults had a significantly higher propensity to spend, and its effect size was rather small. The changes from first to third step suggest that the association between age and propensity to spend and borrow is not due to age per se, but rather, factors that vary with age, such as financial hardship and material values. With respect to family composition, in the first step of the UK survey number of children was significantly related to both propensity to spend and propensity to borrow, and the effect was still strong and significant at the third and fourth step for propensity to borrow. The obvious explanation for this is that the more children you have, the more you must spend at Christmas, which produces greater stress on financial resources and a consequent greater tendency to borrow to fund the additional cost. In the Norway survey, respondents were asked whether they had children, rather than how many. No significant effects were observed, probably because this indicator of family composition is not sufficiently sensitive to detect any effects. As for the small effects of gender that we observed, explaining them is not so straightforward. In a review focusing on borrowing behavior, Davies et al. (2019) observed that most UK research reported that women tended to borrow more than men. It is not clear why the gender difference we found was opposite to this.

Our second research question asked whether the addition of the practical financial variables significantly increased the proportion of variance accounted for in propensity to spend and borrow at Christmas. At the second step of analysis of both surveys, there was no significant association between economic hardship and propensity to spend, but after the addition of the psychological variables the relationship was significant, with greater hardship associated with lower propensity to spend. Furthermore, economic hardship was associated with greater propensity to borrow at all steps of analysis in both surveys. Turning to proactive money management, at the second step of analysis in both surveys this was significantly associated with lower propensity to spend. This suggests that such money management practices are, at least to some extent, effective in controlling spending at this time of high pressure to spend. However, after the addition of psychological variables, this effect diminished, and in the UK survey it reversed. This implies some interaction between proactive money management and the psychological variables. With respect to propensity to borrow, in both cases, less proactive money management was significantly associated with a greater tendency to borrow, although in the Norway survey this diminished after the inclusion of psychological variables. These findings are broadly consistent with previous research on spending and borrowing (Garðarsdóttir and Dittmar, 2012; McNair et al., 2016) and are consistent with the straightforward interpretation that financial hardship and lower proactive money management are root causes of propensity to borrow. This has important policy and practical implications, that we discuss below.

Finally, our third and fourth research questions asked whether the addition of psychological variables increased the proportion of variance accounted for in propensity to spend and borrow at Christmas. As we saw, in both surveys the addition of psychological factors at the third step of analysis increased the proportion of variance accounted for significantly in both outcome variables. Also, at the fourth step of the Norway survey, the addition of propensity to borrow as a predictor of propensity to spend, and vice versa, led to further significant increases. While this was not the case in the UK survey, in both surveys propensity to spend was a significant predictor of propensity to borrow, and vice versa, and the effect sizes of other predictors were lower in most cases at the fourth step in comparison to the third. These findings suggest bidirectional causation between propensities to spend and borrow (Ahlström et al., 2020).

Apart from propensity to spend and propensity to borrow as predictors, the largest psychological effects were those for material values, which was strongly associated with propensity to spend and propensity to borrow in both surveys at step three. These associations remained at step four of the analysis, except that in the Norway survey the association between material values and propensity to borrow was not significant. This suggests an indirect causal path from material values to propensity to borrow via propensity to spend, rather than a direct causal path. Overall, the findings concerning the role of material values are broadly consistent with previous research on spending and borrowing (Watson, 2003; Garðarsdóttir and Dittmar, 2012). However, an inconsistency with respect to the findings of the UK post-Christmas survey (McNair et al., 2016) is that post-Christmas reported spending and borrowing were not significantly associated with material values. Nevertheless, in a reanalysis restricted to the participants who completed both the pre- and post-Christmas surveys (n = 132), although the correlation between material values and reported amount spent was not significant, the relationship between material values and whether participants reported borrowing to fund Christmas spending was significant (point biserial correlation = 0.24. p < 0.01). Further research would be necessary to understand why material values were strongly associated with propensity to spend but not with reported spending post-Christmas.

At steps three and four of both surveys, the extent to which people perceive Christmas as a time of indulgence was significantly associated with propensity to spend, but not with propensity to borrow. This was the only aspect of the meaning of Christmas that made an independent contribution to propensity to spend, and none of them were significant predictors of propensity to borrow. The finding is a contribution to knowledge that identifies a psychological variable that may be at play in financial behavior at Christmas. Our analysis suggests, though, that although this individual difference is a factor underlying propensity to spend at Christmas, it does not necessarily directly contribute to subsequent credit repayment difficulties, since it is not also associated with propensity to borrow. As discussed with respect to material values, however, there may be a causal path from seeing Christmas as indulgence to propensity to borrow mediated by propensity to spend.

The effects of positive and negative affect were different in the two surveys. At the third and fourth step of the UK survey, negative affect, but not positive affect, was significantly associated with both propensity to spend and propensity to borrow, whereas in same steps of the Norway survey, the only significant effect was that lower positive affect was associated with greater propensity to spend. These findings are not contradictory as they are all in the direction of previous research suggesting that more negative or less positive affect is associated with increased spending (Atalay and Meloy, 2011; Park et al., 2022), rather than with research indicating that positive mood leads to increased spending (Murray et al., 2010; Agarwal et al., 2020). Of particular practical importance is the UK finding that greater negative affect in the run up to Christmas is associated with greater propensity to borrow, which could result in post-Christmas debt concerns. However, causal interpretations should be treated with caution, since the anticipation of Christmas may cause less positive and more negative affect, which in turn may influence propensity to spend and borrow.

The relationships between three facets of gift motivation and propensity to spend and to borrow at Christmas were investigated in the Norway survey. One significant association was observed in step 3 of the regression analysis, that between an obligation gift motivation and propensity to spend. This indicates that for some consumers, a part of their Christmas spending is unwanted, and caused by perceived social expectations. Reciprocal gift giving makes people spend more than they want, and for some, more than they can afford. Helping people to find socially acceptable ways of breaking the cycle of gift-giving may be helpful advice for people in a strained financial situation. That this effect was reduced at the fourth step of the analysis may simply be a by-product of the general effect on other predictors of the addition of a new and relatively strong predictor.

Turning to our methodological aim, this was to construct and evaluate scales to assess aspects of the meaning of Christmas, propensity to spend at Christmas, and propensity to borrow at Christmas. This was a prerequisite to addressing our substantive research questions, since such scales have not previously been developed. A positive feature of the new scales is that their items were generated from UK interviewees' own words when expressing their views on these matters. On the other hand, they have limited general utility, since they relate specifically to one context, that of Christmas. Nevertheless, they could be used in future research on issues concerning this annual event. Principal components analysis enabled us to construct scales to measure three facets of the meaning of Christmas, financial concerns, indulgence, and social aspects. In the UK survey the three measures had reasonably good item reliability. However, in the Norway survey item reliability was somewhat lower, and consequently, their effect sizes as predictors would be likely to be underestimated. An obvious explanation for the difference in reliability of the scales is that the items were based on the words and views of UK, rather than Norwegian interviewees. Turning to the scales to assess propensity to spend and borrow at Christmas, these had sound psychometric properties in both surveys. Furthermore, in the UK survey the scales were found to have low to moderate correlations with post-Christmas reports of Christmas spending and borrowing.

As mentioned earlier, a strength of the regression analysis adopted for this research is that the statistical significance and size of the effect of any predictor on a dependent variable can be identified independently of those of the other predictors considered. Future research adopting a structural equation modeling framework could go further, by exploring the relationship between propensity to spend at Christmas and propensity to borrow at Christmas, and whether the effects of some predictors moderate or mediate those of others. Another interesting issue for future research is cross-country comparisons, in surveys adopting appropriate sampling and comparable survey content.

In addition, the present study by no means exhausts the range of psychological variables that may potentially be important. Future research could, for example, include the key variable of financial literacy, and also, specifically for contexts in which spending on gifts is salient, the important affect-related variable of gift anxiety. This would develop the present study's contribution to our understanding of the role of affect on propensity to spend and borrow at times of high pressure to spend, particularly on gifts.

The research presented here can inform interventions to support people's financial decision making at times of high pressure to spend, especially at Christmas. First, one reason Norwegians report less borrowing related to Christmas spending may be due to the tax system (Remote, 2023). In Norway, monthly tax deductions from pay are reduced to zero in June, and by half in December, with these reductions added to the other months of the year. The intention is to ensure that people have more money to spend for their summer holiday and for Christmas. As is evident from our review this is not a panacea, since some Norwegians report borrowing issues pre-Christmas despite this support. Nevertheless, the UK and other countries could adopt similar variable-time tax distribution policies as a clear and concrete measure to alleviate seasonal financial stresses.

In both surveys financial hardship was associated with propensity to borrow pre-Christmas, which for some could lead to an increase in financial hardship post-Christmas. Previous reviews of the literature have found such associations with borrowing and debt more generally and have recommended interventions to support people experiencing financial hardship (Lempers et al., 1989; Garðarsdóttir and Dittmar, 2012; Silinskas et al., 2021). Our findings suggest that these are particularly important pre-Christmas, including practical support from the tax and benefit system such as the above-mentioned. Also in both surveys, less proactive money management was associated with greater propensity to borrow pre-Christmas. This is another association that has been documented for borrowing more generally, and our results imply that interventions to support more proactive money management that have proved effective are particularly important pre-Christmas.

Turning to psychological factors, our finding that less positive affect in one survey, or more negative affect in the other, was associated with a greater propensity to spend suggests that lower mood could lead to overspending and subsequent financial problems, either increased propensity to borrow, as we observed in the UK survey, or other financial problems such as depleted savings. As we concluded from our post-Christmas survey (McNair et al., 2016), the above findings suggest that financial advice and support services should not focus narrowly on practical financial skills but more broadly on supporting the development of psychological resilience.

Finally, the findings of these surveys relate to propensities, the internal motivations to spend and borrow, which are related to, but not synonymous with, spending and borrowing behavior. This is both a strength and a weakness of the research reported. Economic psychology has been described as the science of economic mental life and behavior (Ranyard and Ferreira, 2017), with the former being worthy of study in its own right. A strength of this study, then, is that it contributes to our understanding of an important aspect of economic mental life at a time of high pressure to spend and borrow. On the other hand, however, it only partially contributes to our understanding of pre-Christmas spending and borrowing behavior, since propensities to spend and borrow are only two antecedents to such behavior. Therefore, future research should investigate the extent to which there is a propensity-behavior gap, and how propensities interact with other factors to fully explain actual pre-Christmas spending and borrowing behavior.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving humans were approved by the Economics and Business Ethics Research Committee, Leeds University Business School, UK. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

SM: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. EN: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. RR: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

We are most grateful to Wändi Bruine de Bruin and Barbara Summers for their major inputs into the early stages of the UK study and for their feedback on earlier versions of the paper.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frbhe.2024.1385609/full#supplementary-material

1. ^A subset of participants of the pre-Christmas survey (n = 135) also completed the post-Christmas survey. The findings of the post-Christmas survey, for which additional participants were recruited (n = 162), were reported by McNair et al. (2016).

2. ^For completeness, PCA with direct oblimin rotation was also conducted on the scale. This analysis determined that inter-component correlations where all < 0.32. In such instances, it has been argued that varimax rotation is thus preferred as correlations >0.32 would suggest more than 10% overlap in variance between factors (Tabachnick and Fidell, 2007).

Agarwal, S., Chomsisengphet, S., Meier, S., and Zou, X. (2020). In the mood to consume: effect of sunshine on credit card spending. J. Bank. Finan. 121:105960. doi: 10.1016/j.jbankfin.2020.105960

Ahlström, R., Gärling, T., and Thøgersen, J. (2020). Affluence and unsustainable consumption levels: The role of consumer credit. Clean. Respons. Consumpt. 1:100003. doi: 10.1016/j.clrc.2020.100003

Allgood, S., and Walstad, W. (2013). Financial literacy and credit card behaviors: a cross-sectional analysis by age. Numeracy. 6, 1–19. doi: 10.5038/1936-4660.6.2.3

Atalay, A. S., and Meloy, M. G. (2011). Retail therapy: a strategic effort to improve mood. Psychol. Market. 28, 638–659. doi: 10.1002/mar.20404

Belk, R. W. (1993). “Materialism and the making of the modern American Christmas,” in Unwrapping Christmas, ed. D. Miller (Oxford: Clarendon Press), 75–104.

Bergen, H., and Hawton, K. (2007). Variation in deliberate self-harm around Christmas and new year. Soc. Sci. Med. 65, 855–867. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.04.004

Bourova, E., Ramsay, I., and Ali, P. (2019). The experience of financial hardship in Australia: causes, impacts and coping strategies. J. Cons. Policy. 42, 189–221. doi: 10.1007/s10603-018-9392-1

Davies, S., Finney, A., Collard, S., and Trend, L. (2019). Borrowing behaviour. A Systematic Review for the Standard Life Foundation Report. Personal Finance Research Centre, University of Bristol: Bristol, UK 16.

Deloitte (2018). Christmas Survey 2018. Available online at: https://www2.deloitte.com/uk/en/pages/consumer-business/articles/deloitte-christmas-survey-2018.html (accessed April 4, 2024).

Deloitte (2019). Christmas Survey 2019. Available online at: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/uk/Documents/consumer-business/deloitte-uk-christmas-survey-2019.pdf (accessed January 26, 2024).

Dittmar, H., Bond, R., Hurst, M., and Kasser, T. (2014). The relationship between materialism and personal well-being: a meta-analysis. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 107, 879–924. doi: 10.1037/a0037409

Downs, J. S., de Bruin, W. B., and Fischhoff, B. (2008). Parents' vaccination comprehension and decisions. Vaccine. 26, 1595–1607. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.01.011

Garðarsdóttir, R. B., and Dittmar, H. (2012). The relationship of materialism to debt and financial well-being: the case of Iceland's perceived prosperity. J. Econ. Psychol. 33, 471–481. doi: 10.1016/j.joep.2011.12.008

Givi, J., Birg, L., Lowrey, T. M., and Galak, J. (2023). An integrative review of gift-giving research in consumer behavior and marketing. J. Cons. Psychol. 33, 529–545. doi: 10.1002/jcpy.1318

Goodwin, C., Smith, K. L., and Spiggle, S. (1990). “Gift giving: consumer motivation and the gift purchase process,” in Advances in Consumer Research, eds. M. E. Goldberg, G. Gorn, and R. W. Pollay (New York: Association for Consumer Research), 690–698.

Intrum (2019). Nordmenn bruker for mye og bekymrer seg for julehandelen | Intrum (accessed January 26, 2024).

Kasser, T., and Sheldon, K. M. (2002). What makes for a merry Christmas? J. Happin. Stud. 3, 313–329. doi: 10.1023/A:1021516410457

Keatinge, W. R., and Donaldson, G. C. (2004). Changes in mortalities and hospital admissions associated with holidays and respiratory illness: implications for medical services. J. Evaluat. Clin. Pract. 11, 275–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2005.00533.x

Lempers, J. D., Clark-Lempers, D., and Simons, R. L. (1989). Economic hardship, parenting, and distress in adolescence. Child Dev. 60, 25–39. doi: 10.2307/1131068

Loibl, C. (2017). “Living in poverty: Understanding the financial behaviour of vulnerable groups,” in Economic Psychology, ed. R. Ranyard (London: Jon Wiley and Sons), 421–434. doi: 10.1002/9781118926352.ch26

McNair, S., Summers, B., de Bruin, W. B., and Ranyard, R. (2015). Buy now, worry later: an exploratory study into spending, borrowing, and debt at Christmas (Unpublished manuscript). Leeds University. Available online at: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/211631 (accessed April 26, 2024).

McNair, S., Summers, B., de Bruin, W. B., and Ranyard, R. (2016). Individual-level factors predicting consumer financial behavior at a time of high pressure. Person. Indiv. Differ. 99, 211–216. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2016.05.034

Morgan, M. G., Fischhoff, B., Bostrom, A., and Atman, C. J. (2002). Risk Communication: A Mental Model Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511814679

Murray, K. B., Di Muro, F., Finn, A., and Leszczyc, P. P. (2010). The effect of weather on consumer spending. J. Retail. Consumer Serv. 17, 512–520. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2010.08.006

Mutz, M. (2016). Christmas and subjective well-being: a research note. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 11, 1341–1356. doi: 10.1007/s11482-015-9441-8

Nepomuceno, M. V., and Laroche, M. (2015). The impact of materialism and anti-consumption lifestyles on personal debt and account balances. J. Busin. Res. 68, 654–664. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.08.006

Otnes, C., Lowrey, T. M., and Kim, Y. C. (1993). Gift selection for easy and difficult recipients: a social roles interpretation. J. Cons. Res. 20, 229–244. doi: 10.1086/209345

Park, I., Lee, J., Lee, D., Lee, C., and Chung, W. Y. (2022). Changes in consumption patterns during the COVID-19 pandemic: Analyzing the revenge spending motivations of different emotional groups. J. Retail. Cons. Serv. 65:102874. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102874

Phillips, D. P., Jarvinen, J. R., Abramson, I. S., and Phillips, R. R. (2004).Cardiac mortality is higher around Christmas and New Year's than at any other time: the holidays as a risk factor for death. Circulation 110, 3781–3788. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000151424.02045.F7

Pillai, R. G., and Krishnakumar, S. (2019). Elucidating the emotional and relational aspects of gift giving. J. Bus. Res. 101,194–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.03.037

Ranyard, R., and Ferreira, V. R. D. M. (2017). “Introduction to economic psychology: the science of economic mental life and behaviour,” in Economic Psychology, ed. R. Ranyard (Jon Wiley & Sons), 118.

Remote (2023). How does the half-tax regime work in Norway? Available online at: https://support.remote.com/hc/en-us/articles/21091653551757-How-does-the-half-tax-regime-work-in-Norway (accessed January 31, 2024).

Reshadi, F., and Givi, J. (2023). Spending the most on those who need it the least: gift givers buy more expensive gifts for affluent recipients. Eur. J. Market. 57, 479–504. doi: 10.1108/EJM-01-2022-0042

Richins, M. L., and Dawson, S. (1992). A consumer values orientation for materialism and its measurement: scale development and validation. J. Cons. Res. 19, 303–316. doi: 10.1086/209304

Rick, S. I., Cryder, C. E., and Loewenstein, G. (2008). Tightwads and spendthrifts. J. Cons. Res. 34, 767–782. doi: 10.1086/523285

Sherry, J. F. (1983). Gift giving in anthropological perspective. J. Cons. Res. 10, 157–168. doi: 10.1086/208956

Sherry, J. F., McGrath, M. A., and Levy, S. J. (1993). The dark side of the gift. J. Bus. Res. 28, 225–244. doi: 10.1016/0148-2963(93)90049-U

Silinskas, G., Ranta, M., and Wilska, T. A. (2021). Financial behaviour under economic strain in different age groups: predictors and change across 20 years. J. Cons. Policy. 44, 235–257. doi: 10.1007/s10603-021-09480-6

Tabachnick, B. G., and Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using Multivariate Statistics, 5th Edn. Allyn & Bacon/Pearson Education.

Velamoor, V., Voruganti, L., and Nadkarni, N. (1999). Feelings about Christmas, as reported by psychiatric emergency patients. Soc. Behav. Person. 27, 303–308. doi: 10.2224/sbp.1999.27.3.303

Virke (2023). Prognoser for julehandelen 2023 - Virke- Handels- og tjenestenæringen - Hovedorganisasjonen Virke(accessed January 26, 2024).

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., and Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 54, 1063–1070. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063

Watson, J. J. (2003). The relationship of materialism to spending tendencies, saving, and debt. J. Econ. Psychol. 24, 723–739. doi: 10.1016/j.joep.2003.06.001

Webley, P., Lea, S. E., and Portalska, R. (1983). The unacceptability of money as a gift. J. Econ. Psychol. 4, 223–238. doi: 10.1016/0167-4870(83)90028-4

Wolfinbarger, M. F., and Yale, L. J. (1993). “Three motivations for interpersonal gift giving: experiental, obligated and practical motivations,” in NA - Advances in Consumer Research, eds. L. McAlister and M.l L. Rothschild (Provo, UT: Association for Consumer Research), 520–526.

Keywords: spending, borrowing, Christmas, affect, material values, gift motivation

Citation: McNair S, Nyhus EK and Ranyard R (2024) Propensity to spend and borrow at a time of high pressure: the role of the meaning of Christmas and other psychological factors. Front. Behav. Econ. 3:1385609. doi: 10.3389/frbhe.2024.1385609

Received: 13 February 2024; Accepted: 09 April 2024;

Published: 09 May 2024.

Edited by:

Gerrit Antonides, Wageningen University and Research, NetherlandsReviewed by:

Erik Hoelzl, University of Cologne, GermanyCopyright © 2024 McNair, Nyhus and Ranyard. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rob Ranyard, ci5yYW55YXJkQGxlZWRzLmFjLnVr

†Present address: Simon McNair, Cowry Civic Solutions, London, United Kingdom

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.