- 1Faculty of Human Sciences, Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Lisboa, Portugal

- 2Católica Research Centre for Psychological-Family and Social Wellbeing, Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Lisboa, Portugal

Introduction: This study aims to contribute to understanding factors that explain consumers' preferences for banking institutions. We specifically explored the roles of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)—targeted primarily at Environmental causes and secondarily at Social causes—on corporate image (CI), consumer satisfaction (CS) and consumer loyalty (CL). We tested whether integrating a CSR description with an emphasis on environmental causes into the bank marketing strategy would positively affect CI, CS and CL. We also inspected the effect of online banking vs. direct human contact, and perception of price fairness, as well as that of the consumers' demographic variables.

Methods: A survey was carried out online, with 322 international respondents recruited through social networks. Participants were randomly directed to one of eight different bank conditions, each combining descriptions where Environmental and social CSR, Price fairness, and direct human contact with the clients varied. After reading the bank description participants filled out a questionnaire that addressed their perception of the bank's CI and their projections of CS and CL.

Results and discussion: Results indicated that participants favored the banks that included CSR as part of their description, with the perception of price fairness being the second critical factor in the respondents' CI, CS, and CL. Direct human contact vs. remote banking did not play a role in the participant's ratings of the bank, which is in line with more current studies. We concluded that businesses in the banking sector enhance their global reputation when investing in environmental and social CSR.

The question What makes banks attractive to consumers? was addressed to us by a consumer's awareness association preceding our decision to conduct a study on the topic. Studies on the banking sector report that banks have succeeded over the years in attracting and retaining customers, due to factors that encompass a strong brand name and investment in the brand image (Zhang, 2015), the perceptions of quality and functionality of their mobile digital services (e.g., AlSoufi and Ali, 2014; Mbama et al., 2018), the perceived value of human contact provided by traditional banking services versus time-effectiveness, lower costs and saved time provided by fintech (e.g., Mainardes et al., 2023) and loyalty incentives such as rewards in purchases or programs that foster customers feelings of status (e.g., Chaabane and Pez, 2017). However, the brand image per se, and the emotions that the customer associates with it, have a powerful direct effect on intentions of consumer loyalty (Ou and Verhoef, 2017) and thereby on the brand's continuous profit.

A bank with a “cause”

We departed from the idea that a bank with a good brand image could be a bank with “causes”, and under the current environmental crisis,—it should be supporting environmental causes, and all along not neglecting the support of community social causes. With the environmental crisis speeding up in recent years, consumers developed a strong interest in purchasing environmentally friendly products, driving a “green trend” in a variety of businesses that improves their brand image and marketing strategy (e.g., Gong et al., 2023). So, many economic sectors—from food packaging to cosmetics and clothing—evolved (or are in the process of evolving) into producing more environmentally friendly goods, while including in their marketing strategy information on their environmental impact. The banking institutions cannot develop such a “clean green” strategy, and they traditionally have low impact on environmental sustainability (Abade, 2012; Widodo et al., 2023), but they may still grab the opportunity to attract those who are willing to pay more for eco-friendly products, by supporting environmental and social causes (as these are linked), and indirectly affect environmental sustainability (e.g., Hobeika et al., 2022; Sarfra et al., 2022). So, in this study we incorporated the support of environmental and social causes as part of the bank's corporate social responsibility (CSR) strategy to examine its impact on the bank's corporate image, consumer satisfaction, and consumer loyalty.

Previous studies have evinced the relevance and efficacy of banks' CSR in bringing positive assessments and perceptions by customers (Matute-Vallejo et al., 2011; Habel et al., 2016; Liwan et al., 2023). Given the intangible nature of financial services, and their increasing competitiveness, CSR can be a tool that enables customers to differentiate between entities and that provides the financial entities a competitive advantage (Vanhamme et al., 2012). Thompson and Cowton (2004) argue that financial institutions have the power to affect the environment indirectly, by facilitating industries that cause environmental damage, or opt otherwise to facilitate those that can intervene in environmental causes indirectly through their lending practices by investing in environmentally friendly technologies and companies that foster pollution control measures. By making these choices, banks are taking an environmental stance which can be critical to their brand name. For example, the Co-operative Bank in the UK has terminated some existing business relationships due to such concerns, a decision that positively affected its success in building market share and profitability (Thompson and Cowton, 2004). Additionally, financial institutions consume vast amounts of resources such as paper and energy, and thus they can make changes toward environmentally friendly policies, such as saving energy and reducing consumption of other natural resources (Branco and Rodrigues, 2006; Wu and Shen, 2013) and these too may become part of their public image (see next section) and affect their brand reputation.

Corporate image

Corporate image (CI) is the consumers' perception of a company; this can either be an individual view or opinion or that of a group of stakeholders, and it results from “the interaction of all experiences, impressions, beliefs, feelings, and knowledge people have about a company” (Worcester, 1997). As loyalty stems from approval, building an appealing corporate image has been shown to enhance customer loyalty directly (Zhang, 2015) and to increase repurchasing and recommendation (Pérez and Del Bosque, 2015). CI reflects both physical and behavioral attributes of the firm, including features such as its aims and values, variety of products/services, corporate culture, and the representation of quality communicated by each individual who interacts with the companies' clients (Nguyen and Leblanc, 2001; Zameer et al., 2015). As such, it has two main components: the functional and the emotional—the functional encompasses the tangible and measurable characteristics, and the emotional the psychological dimensions such as feelings and attitudes toward the firm stemming from the consumers' individual experience with the service and their processing of relevant information (Nguyen and Leblanc, 2001). It is thus, subjective, varying according to clients', employees', and shareholders' own interactions with the firm. Consequently, it is expected to vary also across age groups, professional background, education, etc. Securing a firm's reputation and sense of “uniqueness” in a competitive environment is thought to entail an accurate portrayal of its values and ethical behavior, because even though CI is positively related to customers perceived value, it can still have a negative impact on satisfaction, if the customers feel misled or if their expectations of quality are not attended to Zameer et al. (2015).

The banking sector is unique within businesses, as there are only marginal differences in prices among competitors, whilst consumers are flooded with huge volumes of information (RuŽena and Tomáš, 2014). This brings about an opportunity for an effective type of differentiation between different banking institutions—that of building of a strong corporate image.

Consumer satisfaction

The concept of Consumer Satisfaction (CS) adopted by many authors is that of a positive expectation when acquiring a product or a service (Vavra, 1993; Kotler, 2000; Caetano and Rasquilha, 2010). Although service quality should precede and lead to consumer satisfaction, previous studies have considered consumer satisfaction as an antecedent of service quality (Caruana, 2002), because the consumer has a certain expectation of what the product should be, and if expectations are met, there will be satisfaction, resulting from a positive comparison between the expectation and the outcome (Kotler, 2000). A high level of satisfaction will prompt the consumer to repeat the behavior and, in the long run, to become loyal toward that service. Thereby, CS can be measured by assessing consumer expectations, and the degree to which the performance of institutions meets those expectations (e.g., Abade, 2012; Zhang, 2015; Dam and Dam, 2021).

There is a growing understanding that service quality is only one of the factors that affects satisfaction. Another view posits that consumer satisfaction relies on more meeting customer expectations, but also the service providers' attitude and behavior, including such features as ethical standpoints and social intervention (Matute-Vallejo et al., 2011). This ethical component seems to be decisive in the evaluation of the service received, by creating positive associations in consumers' minds, thus, resulting in a higher level of perceived service quality.

The aforementioned studies show that multiple service factors have a significant impact on consumer satisfaction, which in turn, determines their loyalty after a long period of time (Leclercq-Machado et al., 2022). Therefore, consumer satisfaction can be considered as a mediator between service quality and loyalty. The findings of Caruana (2002) confirm this relationship and report that age and education play a major role in determining the different perceptions of consumers on service quality and corporate behavior.

Trust and consumer loyalty

Trust can be defined as “a willingness to rely on an exchange partner in whom one has confidence” (Moorman et al., 1992, p.315). Some markets are not very dependent on trust, for example simple transactions like the selling of fruit (Gill, 2008). In this example, consumers are quite capable of objectively evaluating each piece of fruit independently, and they can also switch merchants easily if they are not satisfied. By contrast, in financial markets consumers require creating a relationship with an agent (e.g., a bank, pension provider, insurer) in which they rely for their expertise. This relationship is, however, created over time as financial transactions are ongoing. When purchasing a financial product such as opening a savings account, consumers are contracting services for the future; thereby, long-term trust is necessary. Consumers of the financial service must believe that the agent is trustworthy and will act in their best interest.

The global financial crisis can cause adverse reactions of the banking and financial industry, partly due to the loss of confidence that consumers manifest toward these entities. Financial problems such as denying mortgages, the high commissions of transactions, or even the fall in interest rates have negatively impacted customer perceptions, driving financial institutions to search for solutions to rebuild trust and maintain loyalty (Matute-Vallejo et al., 2011).

Loyalty, more than satisfaction, is becoming the main strategic goal in today's competitive business environment. Loyalty can be seen as a concept that goes beyond purchase repetition, as it seems to comprises both an attitude and a behavioral dimension in which commitment is the essential feature (Beerli et al., 2004). It is important that banks have a good understanding of consumer behavior so that the appropriate marketing strategies can be used to build a relationship. An example of one of these strategies, is using loyalty programs such as reward schemes (Jumaev et al., 2012). These types of programs create a reluctance to abandon the financial institution that was previously adopted. Loyal customers increase the value of business as well as maintain costs lower than those associated with attracting new customers.

There are a number of reasons why service loyalty is distinct from product loyalty. To begin with, service loyalty is more dependent on interpersonal relationships as opposed to loyalty to physical products, thereby characterizing an essential marketing element of services (Bloemer et al., 1998). The influence of perceived risk is also greater when taking into consideration services, as consumer loyalty is more likely to act as a barrier to consumer switching behavior with the use of such attributes as confidence and reliability. Service loyalty can be defined as an observable behavior—research in banking has resorted to tracking consumer's accounts over a period of time and quantifying the degree of continuity in patronage. This, however, is not a reliable measure for service loyalty—situational factors such as non-availability, variety seeking, and lack of provider preference can result in a low degree of repeat purchasing of a particular service (Bloemer et al., 1998). The role of other factors, such as the evolution of technology, is yet to be considered in loyalty research. The increasing use of internet banking and other customer service alternatives reduced the need for interpersonal communication with banking employees.

Perceived fairness

A consumer's perception of a company's honesty and fairness, expressing the judgment of whether the process followed for reaching an outcome is considered reasonable or just (Matute-Vallejo et al., 2011)—is another potential source of consumer satisfaction with financial services (Pérez and Del Bosque, 2015). Price fairness refers to the justice perceived by consumers in a company's pricing strategy, in which comparisons are established between the prices offered and standard costs or those that are socially accepted (Matute-Vallejo et al., 2011; Habel et al., 2016). Even though it is difficult to define what constitutes a fair price, consumers can still easily identify when there is exploitation or an unjust interaction, by weighing the price against the service quality and the value of the service offered (e.g., Zietsman et al., 2019). For this reason, price fairness can be considered one of the factors that potentially affect consumer satisfaction—banks should be perceived by their customers as being fair with their interest rates or commission, if they wish to create long-term commitments with them as well as be seen as trustworthy (Kaura et al., 2015; Kidron and Kreis, 2020). In Lind's (2001) fairness heuristic theory, fairness judgment is an important heuristic to consider when dealing with a fundamental social dilemma—on the one hand, by identifying and contributing to a social or organizational identity, individuals can extend their capacities to accomplish goals and, most importantly, secure a self-identity; on the other, identifying with group or organization can cause the rejection of one's identity and limit individuals' freedom of action. As humans are at once individuals and social beings living and working in social units, they maintain a strong sense of self, according to Lind (2001), because they solve this social dilemma by using, as a heuristic device, their impressions on fair treatment. Believing that they are being treated fairly prompts a shortcut to be more cooperative with the demands and requests of others, with the perception of fair treatment functioning as a surrogate for interpersonal trust. The consequence of perceived service fairness is that it affects positively the perceived organization's trustworthiness (Roy et al., 2015)—so financial institutions cannot simply rely on providing a high-quality product to foster high returns, as they will likely need to take into account customers' perceptions of norms and fairness and the bank's ethical integrity to keep customer satisfaction (Kidron and Kreis, 2020).

Previous research in the banking sector has shown that fair price perceptions often trigger negative emotions toward the service entity (Xia et al., 2004), driving both behavior change and institution switching (Lymperopoulos et al., 2013). A study by Ernst and Young Global Limited (2012) revealed that dissatisfaction with high fees was one of the main drivers of attrition, because consumers demand more transparency and better interest rates, and banks who are perceived to be unfair with their pricing tend to see their reputation damaged.

Internet banking

Online banking can be defined as the provision of information or services by a bank to its customers via the internet (Floh and Treiblmaier, 2006; Poovarasan and Leslin, 2022). The internet allows banking agents to carry out activities virtually with the potential for cost savings and speed of information transmission. From this standpoint shifting as many activities as possible to online platforms seems to be a smart move for financial institutions, but how useful this shift is seems to be the least explored feature of satisfaction with banking services (Patel and Siddiqui, 2023). At the same time, a new question arises—how to preserve consumers' loyalty when their relationship becomes a virtual one? Internet banking services have unique features, absent in traditional banking services—e.g., allowing customers to carry out a wide range of activities at any time and place with low handling costs (Amin, 2016). Not only this helps banks to reduce operation and fixed costs, but it also allows them to build better relationships with their customers. For consumers who have a modern lifestyle, dealing with Internet services on a daily basis for varied purposes, internet banking might feel more satisfying than for those who have a harder time with technology (Almaiah et al., 2022). Consumers' readiness to adopt technology has been pointed out as a significant factor in the understanding of the benefits of online services (e.g., Amin, 2016; Almaiah et al., 2022).

When consumers feel that they have been misled or treated unfairly, they rely upon others to choose the right form of action, which may entail looking for alternative businesses, finding stories similar to their own, or learning about how others dealt with the situation (Gill, 2008). The Portuguese Association for Consumers' Defense (DECO) conducted a study on the costs and benefits of Internet banking and concluded that users can save more than €300 per year if they use these services instead of traditional ones (DECO, 2012, as seen in Martins et al., 2014). People may hesitate to use internet banking due to lack of knowledge on its benefits (Amin, 2016) and feel encouraged to continue using and endorse online banking if the system is simple, intuitive, safe, and user-friendly (Almaiah et al., 2022; Mir et al., 2022). But it is reasonable to assume that when individuals have before them a high commitment decision they ponder and seek the opinions of others; as for most people opening a bank account or applying for credit are serious decisions that can impact their lives in the long run, it is expectable that they seek an expert opinion, and thus feel more comfortable with a more traditional banking service where they can go to a counter and speak to a bank clerk (Botha and Reyneke, 2016). As there is no personal communication between employees and clients, the consumer's trust can only be based on the brand's reputation. A company's reputation is a valuable asset that requires investment of resources and attention to customer relationships (Jarvenpaa et al., 2000). This can sometimes be hindered by the users' habits, as some may struggle with the use of an internet application due to a lack of internet skills and experience. In addition, other factors such as interpersonal and personality traits, social networks and security concerns, influence consumers toward adopting (or not) Internet banking (Amin, 2016).

Hypotheses

In a landscape of banking crisis, with an increasing social concern with the global environmental crisis, taking into account the aforementioned factors in building consumer trust and loyalty to a bank/financial institution, the current study set out to explore the effect of corporate social responsibility, emphasizing Environmental causes, on corporate image, consumer satisfaction, and consumer loyalty, while inspecting also the combined effect of other bank salient features, such as providing online banking or also traditional offices with human proximity, and the perception of fair pricing.

In previous studies, CSR was considered a main component of corporate image, and it is likely to be a key differentiator when choosing between banks. In the current study, in addition to determining this, we also aimed to disentangle the effects of perceived service price fairness and proximity with the client/vs. Internet banking, as separate constructs that might contribute directly to consumer satisfaction and to intended loyalty. So the combination of these factors produced the 8 conditions whose differences we predict in H1.

H1: Statistically significant differences in the variables of corporate image (CI), consumer satisfaction (CS) and consumer loyalty (CL) are expected between the eight different bank conditions. Scores of CI, CS, and CL should be significantly higher in the bank conditions that include CSR descriptions and/or fair price, and/or human proximity to consumers.

As previously mentioned, for Internet banking to be as satisfying to consumers as face-to-face communication, a certain level of Internet proficiency has to be present and/or perceived simplicity and effectiveness. If a consumer cannot fully benefit from the internet service being provided, he/she will not be as satisfied with the bank as if he/she had a bank representative providing assistance regarding the consumer's concerns and requests, so we would expect that this condition should be preferred overall (Amin, 2016). This, in turn, can affect the banks' image, as well as strain consumer loyalty. The consumers' characteristics might also play a role in satisfaction stemming from online banking, as younger individuals who have experience with using the Internet from a young age should have an easier experience with Internet banking than older clients. The desirability of a bank or financial institution has been linked to the consumer's, age, traits, preferences, and priorities (Nguyen and Leblanc, 2001) we thought that demographic variables could reveal group differences. Additionally, millennials have been pointed out as the most ethical generation and studies of their perceptions of CSR authenticity reveal that price is not their major concern when assessing a business, but rather authentic CSR and ethical corporate practices (Chatzopolou and de Kiewiet, 2020), we sought to inspect the effect of demographic variables (age, gender, education, and nationality) as well, and we expected younger groups and participants with higher education to differ somewhat in favoring conditions with CSR and internet banking as explicit in H2.

H2: Statistically significant differences in the variables of corporate image (CI), consumer satisfaction (CS) and consumer loyalty (CL) are expected between levels of the sociodemographic variables (gender, age, educational level, country)—younger clients and/or higher educational levels are expected to score higher than older clients and/or less educated clients on CI under conditions that incorporate CSR; and to score higher on CS in bank conditions that incorporated CSR and online banking.

From the literature reviewed above, corporate image (CI) has been linked in several studies to customer loyalty (CL) and to customer satisfaction (CS), either directly or indirectly (e.g., Dam and Dam, 2021), sometimes with (CS) and other variables such as CSR marketing mediating that link (e.g., Gong et al., 2023). Thereby, in the banking sector we expect the CI–CL link also to be strong and if CI drives CS and CS also CL that all these three variables strongly associate, as formulated in H3.

H3: Statistically significant relationships between the variables of corporate image (CI), consumer satisfaction (CS) and consumer loyalty (CL) are expected to occur: The more positive the perceived corporate image of the bank the higher the consumer loyalty; The more positive the perceived corporate image the higher the expected consumer satisfaction; The higher the consumer satisfaction the higher the consumer loyalty.

Method

Participants

A total of 322 participants (female = 191, 59%) between the ages of 18 and 73 (Mean = 30.76; SD = 11.07) were included in the study—from an original database with 333 respondents, as some were removed for not having completed the survey. Most participants held a bachelor's degree (n = 140, 43.2%); the others had a master's degree (n = 78, 24.1%) or a primary and secondary diploma (n = 96, 29.6%) or did not respond (n = 8, 2.4%), and most were employed (n = 161, 49.7%). Participants were mainly from Eastern Europe (n = 94, 29%), the United Kingdom (n = 93, 28.7%), Western Europe (n = 49, 15.1%), North America (United States of America and Canada; n = 38, 11.7%), 42 participants (13%) were included in the category “Others” for not belonging to any of the previous groups, whilst the remaining (n = 6, 1.8%) did not respond.

Instruments

An assessment protocol was created online, incorporating questions on corporate image (CI), consumer satisfaction (CS), and consumer loyalty (CL) based on the instrument used in Vanhamme et al. (2012) experiment, and included questions to retrieve demographic data relevant to our research questions. To measure each of the three dependent variables (CI, CS, and CL), three items were used for each variable, with a seven-point semantic differential scale (“Very bad/Very good”, “Completely Disagree/Completely Agree”, “Not Likely at all/Very Likely”). A Likert type scale is ideal for this study because it allows the quantitative measurement of attitudes (Gliem and Gliem, 2003); the final score on each variable, was obtained by the mean of scores of its three items.

Corporate image

The two main components—functional and emotional—characteristics of this variable were included (Nguyen and Leblanc, 2001): The functional refers to tangible characteristics that can be easily measured, while the emotional is associated with psychological dimensions such as feelings and emotions toward the bank. Items: 1. This bank probably has a good reputation; 2. Their main focus is the wellbeing of their clients; 3. This bank provides a better image compared to other banks.

Consumer satisfaction

Satisfaction is felt by consumers when they feel like the company is achieving their expectations (Zameer et al., 2015). Respondents were asked to evaluate the extent to which the bank reached their expectations, as well as if it provided quality and efficiency. It can be assumed that if respondents rated positively the bank's descriptions in terms of quality and efficiency, expectations had been reached. Items: 1. This bank corresponds to my expectations; 2. The bank provides quality and efficiency; 3. This bank, compared to my present bank, is better.

Consumer loyalty

As commitment is an important antecedent of a long-term relationship or customer loyalty (Matute-Vallejo et al., 2011), respondents were asked how likely they saw themselves as clients of the bank. If respondents perceived themselves as capable of committing to the services provided, it would suggest that they could develop an enduring wish to maintain a valued relationship. Items: 1. I would recommend this bank; 2. My finances would be safe in this bank; 3. I see myself being a client of this bank.

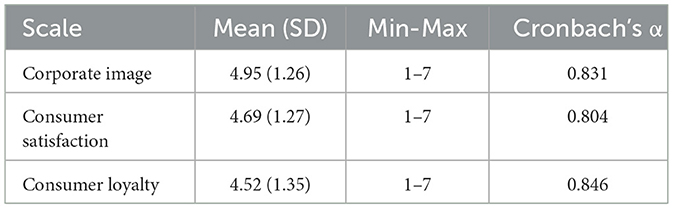

The aforementioned scales performed—as seen in Table 1—all with very satisfactory internal consistency, with Cronbach's α coefficients ranging from 0.801 to 0.846.

Table 1. Corporate image, consumer satisfaction, and consumer loyalty: psychometric characteristics.

Study design

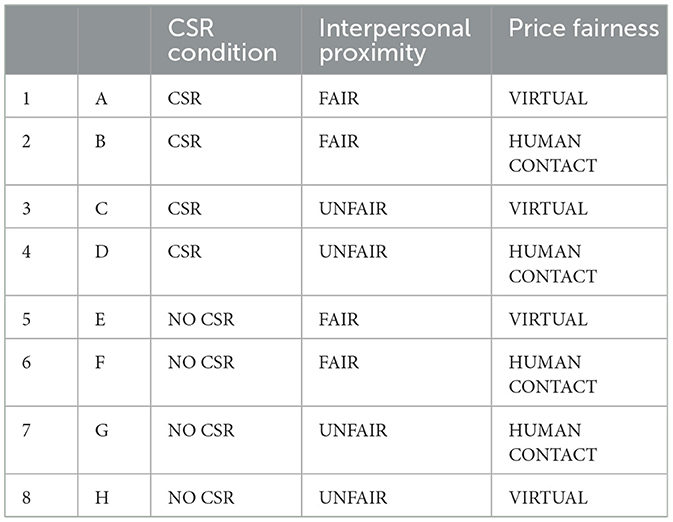

To test the hypotheses, a 2 (CSR/nonCSR) × 2(FAIR/UNFAIR) × 2 (HUMAN/VIRTUAL) factorial between-subject experiment was designed with the three attributes manipulated in the contents of the market research prospection survey. This lead to the creation of eight different hypothetical banking scenarios (see Supplementary material). Participants were randomly assigned to one of the 8 scenarios/bank descriptions when entering the questionnaire platform and asked to fill a questionnaire on their perception of a given bank, described to them according to one of the 8 scenarios, and as a real bank conducting a market prospection. The questions were formulated to assess participants' perceived corporate image, consumer satisfaction, and consumer loyalty in these banking scenarios conditions; the eight different bank scenarios were thus combinations of the variable levels: Condition A: CSR + VIRTUAL + FAIR (n = 78, 24.1%); Condition B: CSR + HUMAN + FAIR (n = 46, 14.2%); Condition C: CSR + VIRTUAL + UNFAIR (n = 43, 13.1%); Condition D: CSR + HUMAN + UNFAIR (n = 29, 9%); Condition E: NOCSR + VIRTUAL + FAIR (n = 29, 9%); Condition F: NOCSR + HUMAN + FAIR (n = 35, 10.8%); Condition G: NOCSR + HUMAN + UNFAIR (n = 28, 8.6%); Condition H: NOCSR + VIRTUAL + UNFAIR (n = 36, 11.1%).

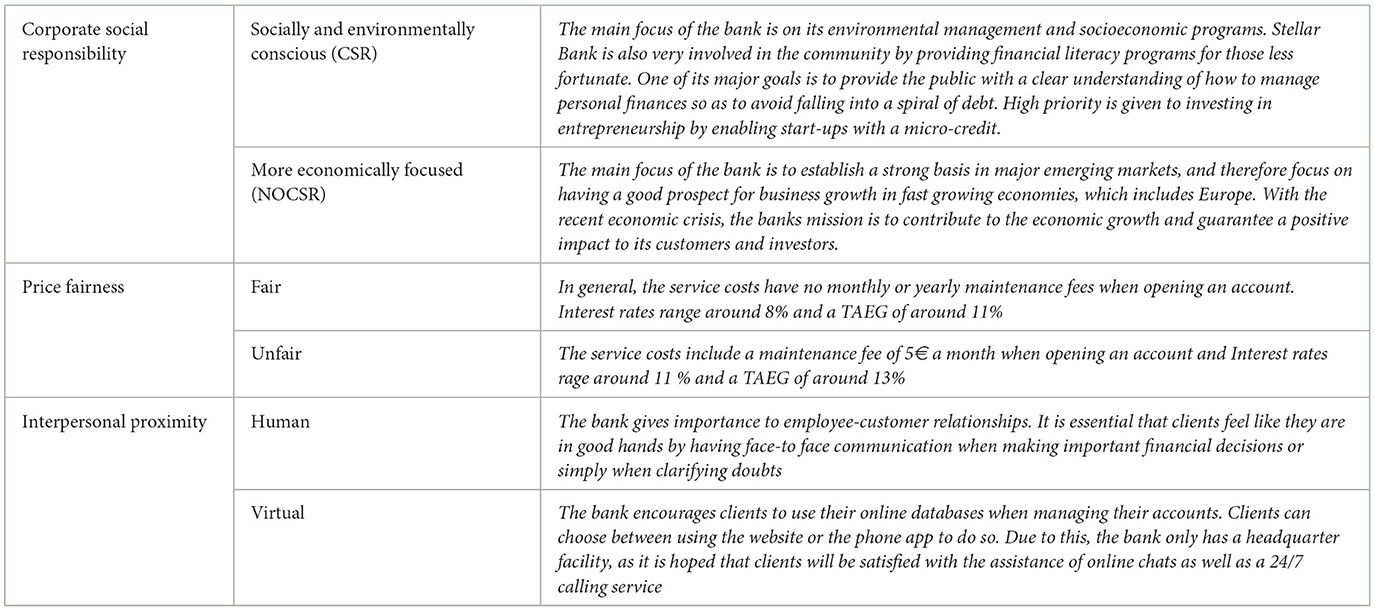

Table 2A presents the descriptions of the variables used for the various conditions. Table 2B shows how they combine to form the eight combinations (conditions) to which participants were assigned.

Table 2B. The 8 conditions in the quasi experiment 2(CSR/noCSR) × 2 (online/human) × 2(fair/not fair).

Data collection and analysis procedures

Participants were invited via email or social media networks to participate in and disseminate an online prospective study for the establishment of a new bank in their country. Reminders and posts were launched every other week for the period the survey was online. Participation relied entirely on a volunteer basis, and thereby this snowball recruiting strategy resulted in samples from different countries having different sizes. The online study was created using Google Forms. Before initiating the survey, those who accepted to take it would press one of 8 letters (A to H) to begin the survey. These would appear in different orders every time the survey was entered. Depending on which letter the participant pressed he/she was directed to one of the 8 conditions. This enabled assigning the manipulation conditions with an almost random process. Participants were thus unaware that this was not a real bank and that there was more than one description. All descriptions began with the sentence “Recently a new bank called ‘Stellar Bank' has established in your city”. Then, one of the combinations (as seen in Table 2B) of descriptions (seen in Table 2B) followed. After reading the description the participant proceeded to the questionnaire.

Participants were presented with a consent form with the aims of the study and ethical information (e.g., voluntary participation, possibility to withdraw without consequences). When data collection was closed, the fact that the target bank was not real was revealed in a thank you message on social media and email listings used to recruit.

Data were collected from November 2018 through January 2019. Incomplete surveys were removed from our sample.

Data was analyzed using Jamovi 2.3.18. Descriptive statistics were computed to examine the overall levels of CI, CS and CL per bank condition. Differences in the dependent variables as a function of the manipulated bank conditions were tested with non-parametric analyses of variance (Kruskal–Wallis H), as data did not follow normality (Kolmogorov–Smirnoff tests of normality indicated p > 0.05), followed by Dwass–Steel–Critchlow–Fligner (DSCF) pairwise comparisons. To examine differences on all 3 dependent variables as a possible function of demographics, differential tests were performed, in particular Mann–Whitney U-tests between gender, and Kruskall–Wallis H-tests between, age level of education, and nationality groups, followed by DSCF pairwise comparisons to examine the highest contrasts between conditions. Spearman correlations were carried out to examine the relationship between CI, CS, and CL. All results were considered statistically significant if p < 0.05.

Results

Differences in the variables of corporate image (CI), consumer satisfaction (CS), and consumer loyalty (CL) across the manipulated bank conditions

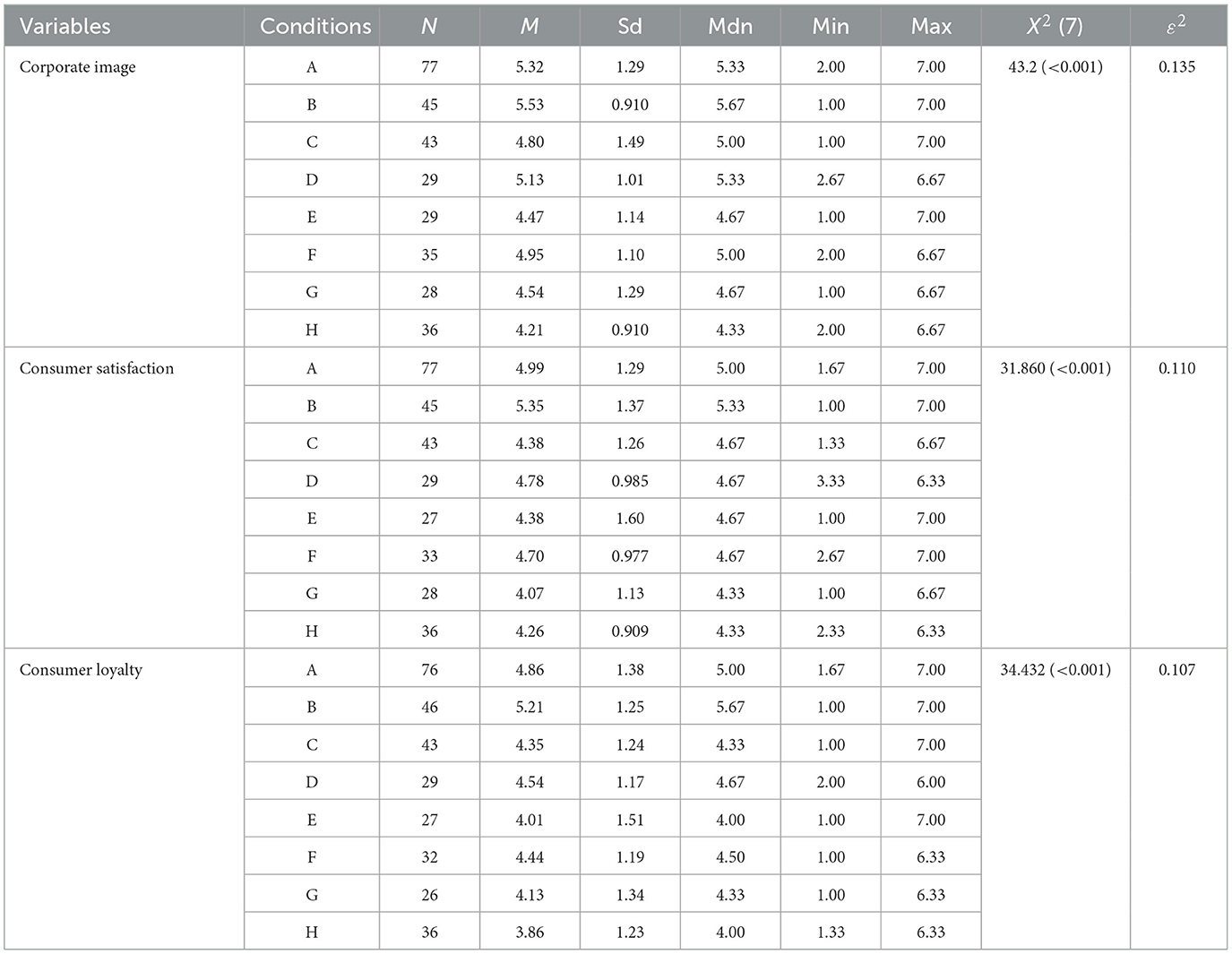

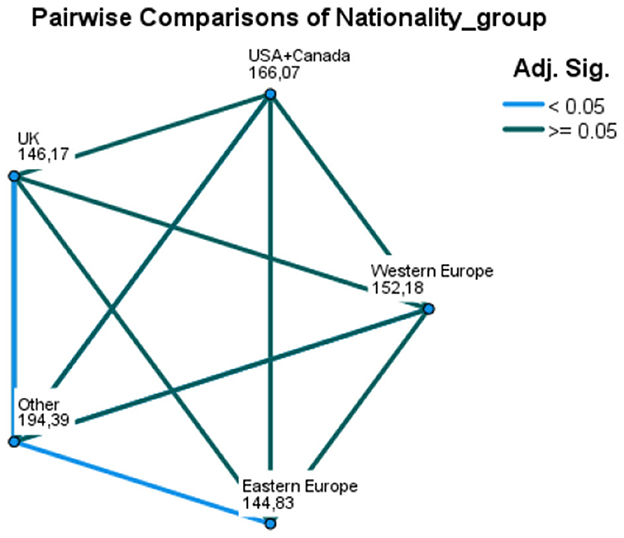

The analysis of differences in the variables of corporate image (CI), consumer satisfaction (CS), and consumer loyalty (CL) between the eight different conditions are presented in Table 3 and Figure 1. For all three variables under consideration, there are significant differences between scenarios: [(CI: X = 43.2, p < 0.001, ε2 = 0.135; CS: X = 34.7, p < 0.001, ε2 = 0.110; CL: X = 343.7, p < 0.001), ε2 = 0.107]. When Dwass–Steell–Critchlow–Fligner pairwise comparisons were applied we found that in the CI variable the differences occur between the conditions A and H (W = −6.085, p < 0.001), B and E (W = −4.925, p = 0.012), B and G (W = −5.286, p < 0.005), B and H (W = −6.921, p < 0.001) and, D and H (W = −4.932, p = 0.011); in the CS variable the differences are between the conditions A and G (W = −4.521, p = 0.030), A and H (W = −4.681, p = 0.021), B and C (W = −5.039, p = 0.009), B and G (W = −5.741, p = 0.001) and B and H (W = −6.093, p < 0.001); and, in the CL variable the differences are registered between the conditions A and H (W = −5.028, p = 0.009), B and C (W = −4,852, p = 0.014), B and E (W = −4.746, p = 0.018), B and G (W = −4.652, p = 0.022) and, B and H (W = −6.325, p < 0.001).

Table 3. Differences in the variables of corporate image (CI), consumer satisfaction (CS), and consumer loyalty (CL) across the manipulated bank conditions.

Figure 1. Pairwise comparisons according to the conditions. Differences in the variables of corporate image (CI), consumer satisfaction (CS), and consumer loyalty (CL) according to gender, age, education, and nationality.

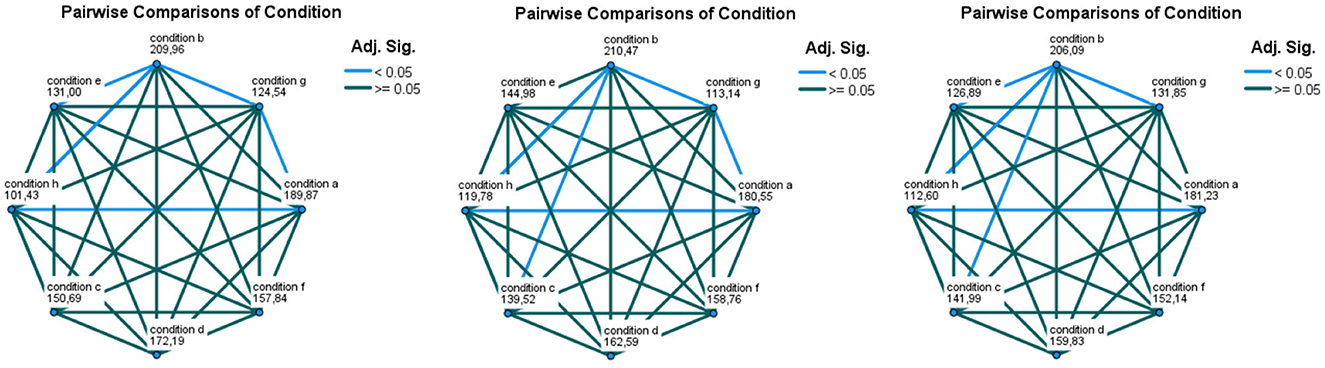

When examining possible differences in CI, CS, and CL in regard to sociodemographic variables (gender, age, educational level, nationality), we found no differences according to gender (CI: U = 12,319, p = 0.850, r = 0.0124; CS: U = 11,535, p = 0.400, r = 0.0553; CL: U = 11,761, p = 0.828, r = 0.0144), age [CI: X = 0.870, p = 0.833, ε2 = 0.003; CS: X = 0.555, p = 0.907, ε2 = 0.002; CL: X = 0.877, p = 0.831, ε2 = 0.003], or educational level [CI: X = 1.891, p = 0.595, ε2 = 0.006; CS: X = 3.063, p = 0.382, ε2 = 0.010; CL: X = 0.321, p = 0.956, ε2 = 0.001]. However, differences emerged according to nationality, only for the CS variables [CI: X = 10.07, p = 0.056, ε2 = 0.0322; CS: X = 10.70, p = 0.030, ε2 = 0.0346; CL: X = 9.20, p = 0.0569; ε2 = 0.0301). These differences occurred between the Eastern European participants and the participants in the group Other Nationalities (W = 4.284, p = 0.021), and between the UK participants and the participants in the group Other Nationalities (W = 4.082, p = 0.032), where UK and Eastern European participants had the lowest scores (cf. Figure 2).

Figure 2. Pairwise comparison according to the nationality group. Relationship between the variables of corporate image (CI), customer satisfaction (CS), and customer loyalty (CL).

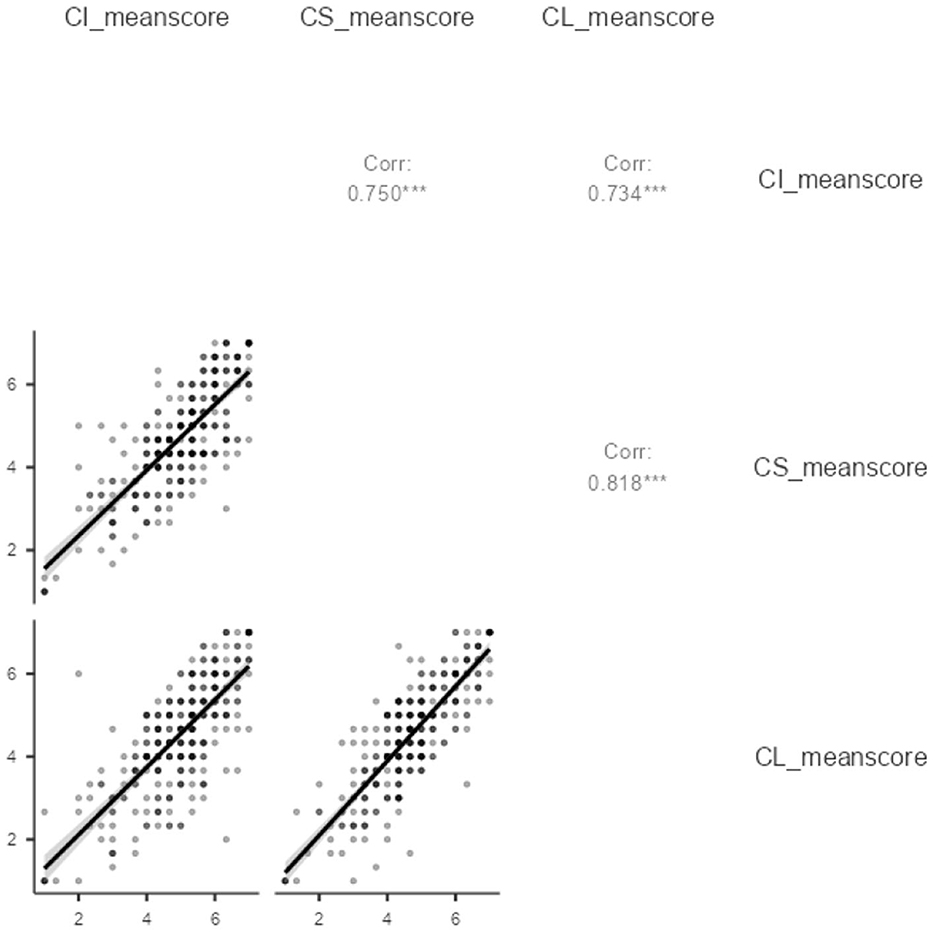

Results indicate the existence of statistically significant, positive, and strong relationships between all variables (rci − cs = 0.750, p < 0.001; rci − cl = 0.734, p < 0.001; rcs − cl = 0.818, p < 0.001; cf. Figure 3).

Discussion

Our results confirmed most of our expectations. First, they indicated that corporate image (CI), consumer satisfaction (CS), and consumer loyalty (CL) differed significantly according to conditions offered by the bank (confirming H1). The bank scenario that scored highest on all these variables was the one in condition B—whereby the bank is focused on environmental and social causes (CSR), provides human contact in physical offices (HUMAN), and practices fair prices (FAIR). This condition differed the most from all others, contrasting mainly with conditions E and G (both with CSR absent) and with condition H (the complete opposite of B, with no CSR, no human contact, and unfair prices).

Demographic variables did not influence CI, CS, and CL the way we expected (H2), with the exception that consumers from Eastern Europe and the UK scored significantly lower on CS than those from other origins.

Our results also confirmed that the CI, CS, and CL variables are strongly associated among themselves (H3), and stressed a major association between CS and CL, and also a very strong association between CI and CS. The strong correlations between the outcomes of our bank conditions are supportive of the proposition that a strong CI drives CS, and CS drives CL. Thereby we focus our discussion on building a good CI in the banking sector.

A good corporate image is thought to be the outcome of positive experiences, feelings, and information the public has gathered about a certain company (Worcester, 1997). The current study manipulated two of the main components, functional and emotional, that might impact one's image of a company. CSR is related to the emotional side of one's opinion, whilst price fairness is the functional attainable perspective (Nguyen and Leblanc, 2001).

The most striking result in our study was the importance of CSR to customers, as the other two features (price fairness and direct human contact) would be more expected to affect CS and CL scores—they are more self-oriented, benefiting directly the customer. From all 8 bank conditions, those with CSR scored the highest on CI.

CSR emerged from our results as more relevant than human contact and that price fairness, and the latter was more important than human contact. So, it seems that CSR was the major contributor to CI, followed by price fairness.

Even though environmental CSR is often neglected in times of crisis as noted by Seles et al. (2018) in a literature review, it also harnesses support by stakeholders and contributes to organizations' success in those very times of crisis, and globally the author's analysis indicates that in such periods there is a larger investment in environmental and social CSR than the abandonment of these practices. However, while there is some evidence that CSR was a factor in the promotion of banks' reputations even during the financial recession of 2008–2009, the banks' financial performance did not increase as a result of CSR (Forcadell and Aracil, 2017). Other authors (Englert et al., 2020) claim that during financial crises the factors that bring up the banks' reputation are mostly non-financial and focused on other attributes and people's perception is largely driven by media visibility and the “emotional” tone of that media content. It seems likely that a good reputation based on CSR is consistently built over time and does not provide immediate returns, and, as suggested by Forcadell and Aracil (2017), CSR has to be in line with the (good) reputation of their respective bank managers.

Public opinion on banks was strongly affected after the global financial recession of 2008–2009 and in its aftermath, as trillions of dollars were lost and bank CEO's reputation was severely damaged. Our data was collected in 2018 and 2019, a long time after the recession, but the importance given to the moral features of banks probably never ceased to increase.

Additionally, the increased concern with the environmental crisis that has built up in recent years suggests that environmental and social CSR may be building CI by providing meaning to customers' choices and creating a connection with the brand. Although CSR has not been under the spotlight of public attention and customer scrutiny in the financial services sector, at least not as much as in other businesses that produce actual goods (Branco and Rodrigues, 2006) it can give banks a competitive advantage compared to those which are solely financially driven, as Matute-Vallejo et al. (2011) point out. Indeed, an increasing number of studies suggest that consumers might relate to brands by identifying with a cause that has been incorporated in the brand's cause-related marketing campaigns, affecting both self-image and corporate image evaluations (e.g., Kim and Sullivan, 2019; Vredenburg et al., 2020). In the current study, bank conditions encompassing CSR mentioned cause-related campaigns, both environmental and social. These mentions were all the information available for respondents to score CI, CS, and CL—as the bank was fictitious and no other information was available, and no interaction with the bank ever existed. Scores on CS and CL were thus projections of what they might have been and were highly correlated with CI, which was the only real assessment possible. This further strengthened the critical role of CSR in the financial institutions strategy to develop CI, and consequentially, CS and CL.

The perception of Price Fairness, in turn, would have been expected to play a primary role when evaluating financial services, especially banks—the pricing of taxes and maintenance fairs has a direct impact on their financial situation and reflects the justice that is perceived by consumers in the bank's pricing strategies. Taking this into consideration, participants might have had difficulty in understanding if the price fairness (PF) condition was truly fair, as it is difficult to articulate what is fair in this business without a good financial literacy that most people do not have. However, participants were able to identify an unfair action, as would be expected (Matute-Vallejo et al., 2011). Respondents might have a basic understanding of what is an abusive price and what is not, allowing those in conditions with no price fairness to evaluate both corporate image and corporate satisfaction negatively. The effect the perception of price fairness seems to have had on corporate image stresses the importance for banks to be just and transparent with their pricing policies (Habel et al., 2016). Some credit unions have experimented with web-based tools that help clients to select mortgages or loan programs that best fit their financial situations (Matzler et al., 2006). And by doing so with open and honest information on bank services, they may be indeed contributing to building a respectable CI, and as a consequence, CS and CL.

Drawing from the results, the type of interaction between a bank and its clients seems to have little importance. The only difference between the bank conditions A and B, was the fact that, in condition A the bank portrayed a more virtual interaction with their clients while in condition B it was described with an emphasis on face-to-face. It was initially assumed that respondents would be sensitive toward this variable, as facing monetary concerns and making investments can be perceived as high-risk situations (Samadi and Yaghoob-Nejadi, 2009), and advice from a bank clerk can consequently be welcome. One of the main factors for why respondents would have preferred the more traditional interaction conditions is due to the poor perceived service quality and consumer satisfaction that online purchasing can bring (Amin, 2016). However, this perception might have been obfuscated by the salience of the perception of CSR, and reasoning on PF. Also, online banking has developed further than just being informational: individuals can pay bills, transfer funds, print statements and check transactions from their mobile phones, making transactions easier to access and more time efficient (Yee-Loong Chong et al., 2010). Thus, it is likely that a more internet-based bank may be preferred by those who already have the habit of using web services, finding them easier and more convenient to use.

Contrary to our initial expectations, no differences were found between the four age groups in their preferences over Internet or face-to-face banking. Our expectations were based on two assumptions from previous studies: (a) that mature clients would have more difficulty in learning to use Internet banking (e.g., Mattila et al., 2003) and (b) that mature clients prefer a face-to-face banking service due to a lack of trust in digital media and high perceived privacy risk (e.g., Gaitán et al., 2015).

There are multiple interpretations for this absence of differences and the general preference for face-to-face banking. When individuals have to make a high-commitment decision, they tend to take time to ponder and seek the opinions of others. Applying for some form of credit or investment are serious decisions that can impact an individual's life in the long run. One might therefore need an expert opinion and thus prefer a more traditional banking service where one can go to a counter and speak to a bank clerk (Botha and Reyneke, 2016). For this type of service and level of commitment, there is no reason why it should be different across the age range of adult customers when choosing a new bank. Younger clients are more likely to use online banking for most other banking services, as they have fewer responsibilities and are less likely to invest or buy credit (Camillieri and Grech, 2017). Mature clients may use online banking for the same reasons but still prefer to talk about high-risk decisions with a bank expert. It is also possible that mature client's banking habits are changing swiftly. The role of income in these preferences was not possible to address, due to the diversity of participants' countries, and their respective different economies and policies. Our respondents across age groups were people comfortably using social media and online applications as the study was online. In other online surveys on banking services, the population of respondents to this topic is typically young (e.g., Akter et al., 2023), so perhaps studies are globally underrepresenting the barriers many bank clients may have with online banking. It is also possible that as the web services of financial companies become increasingly more user friendly (e.g., Almaiah et al., 2022; Akter et al., 2023) that some of our expectations based on earlier studies have been outpaced. There is evidence that when there is more investment in the quality of online service the number of web-based banking and financial services users is higher and so is their satisfaction (e.g., Mainardes et al., 2023). The example of Citibank as compared with other banks, as the highest in technology investment and web users in 2015 (46%) is revealing, although at the time their customer adherence to web and fintech was still under 50% (Chen et al., 2017).

Internet banking has been well-established for more than a decade, and it is widely recognized to enhance participants' efficiency and effectiveness, allowing convenient access to bank accounts (Yuen et al., 2010). Although in traditional banking the human factor and the perception of empathy are associated with customer satisfaction with the bank, that perception did not differ significantly between traditional and web-based services in a recent study by Mainardes et al. (2023) on the Brazilian banking sector. Our results may be expressing the perception of the added value web-based services bring to face-to-face interaction.

In most studies, consumer satisfaction (CS) is a good predictor of re-purchasing, which would then lead to consumer trust and loyalty (e.g., Chang and Fong, 2010; Leclercq-Machado et al., 2022). The current study's results show a clear positive correlation between all three dependent variables, thereby indicating that corporate image, consumer satisfaction, and consumer loyalty are highly associated and affect each other in the same direction.

As the main significant differences were between bank conditions that did not have, first and foremost, CSR, it is clear that this feature is key to CI and CS. This is consistent with previous studies reporting the connection between the business's social and environmental causes and corporate image, reputation, satisfaction, and loyalty (e.g., Zameer et al., 2015; Aramburu and Pescador, 2019; Vredenburg et al., 2020). In the banking sector and in line with our results, researchers addressing the customers of banks in the Basque Country found a connection between CSR and CL-mediated by corporate reputation (Aramburu and Pescador, 2019), and others studying banks in Pakistan also found a strong relation between CSR and CL-mediated by an identification process with the bank and their CSR causes (Raza et al., 2020; Sun et al., 2020).

The strength of the correlations in our study suggests a stronger link between CI and CS and a stronger direct link between CS and CL. However, there is also a strong correlation between CI and CL. In our prospective study, both CS and CL are projections of what might be, as respondents do not have a relationship with the bank and the descriptions in the survey only enable them to form a corporate image. But in real life, consumer loyalty to a bank has been associated with the bank's attitude and behavior in the long run, including its reputation from the ethical and social intervention standpoints (Matute-Vallejo et al., 2011; Fatma and Khan, 2023), thereby reflecting a direct link between CI and CL. In addition to CSR, there are certain expectations of the quality of a bank's services deemed to generate satisfaction, and only when they are met will customers be satisfied (Caruana, 2002). Another contribution to this link is the perceived price fairness, which reportedly builds a positive CI, supporting the belief that the bank is being fair and truthful toward its clients, and promotes both more customer satisfaction and an honest long-term relationship (Kaura et al., 2015). Another important factor for customer satisfaction is a valued relationship between the bank and its customers. However, as previously mentioned, it was not necessary for there to be direct human contact for this relationship to be valued—for example in Kaura et al. (2015) study, both employee behavior and information technology were equally important for customer satisfaction and customer loyalty.

Study limitations

The study's recruitment method and the fact that the experiment was conducted online did not enable a representative sample of the European population that uses banking services. People who do not have access, or who do not regularly use the internet or social media, or the websites that were being used to reach them could not be surveyed. This sets limits to the conclusions that can be drawn from the study.

Caution is also to be taken regarding the results on the perception of price fairness—as we had an international and quite diverse respondent sample and the perception of pricing in different countries may be affected by pricing policies such as caps and floors or the efficiency and stability of the financial situation (Wruuck et al., 2013).

Another limitation of the study was the fact that the variable income could not be used when analyzing the dependent variables. Once again, as the study was conducted with an international sample (comprising over fifty countries of residence), income could not be compared between subjects without taking into consideration the political and economic status of each country.

Conclusion

This study contributes to understanding what are the key factors for individuals who are considering becoming customers of a given bank/financial institution. The three dependent variables of corporate image, consumer satisfaction and consumer loyalty scored higher when corporate social responsibility and price fairness were incorporated into the bank's attributes. CSR had a strong focus on environmental causes. This stresses the importance of philanthropy, and in times of crisis perhaps altruism as well, on public opinion, as well as a sense of fairness. The increased global interest of doing good in social and environmental contexts shows that the prioritization of corporate moral obligations is essential to the public's preference. The results also indicate that it is important not to neglect the public's perception of price fairness, as people can identify quickly when they are being unfairly treated. If the perceived price of the bank is found reasonable it increases customer satisfaction as well as loyalty, and these are critical to developing long-term relationships between the bank and customers. Our results also suggest that while people enjoy having easy access of phone applications and 24/7 calling services for their routine banking activities, they still value having human face-to-face contact with the bank.

All in all, the study supports a paradigm shift for banks, whereby these financial institutions benefit the most in recruiting new customers and promoting the loyalty of their current ones, from a strategy that encompasses a corporate image built on a responsible contribution to environmental and social causes and keeping costs accessible, rather than focused on entrepreneurship, business growth, and financial performance.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Católica Research Center for Psychological, Family and Social Wellbeing. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

AG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. JC: Formal analysis, Supervision, Writing—review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Director and staff at DECO - Portuguese Association for Consumers' Defense, who provided decisive insights that led to conducting this study and on banking services price fairness.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frbhe.2023.1330861/full#supplementary-material

References

Abade, T. R. (2012). Satisfação e fidelização dos clientes bancários no Algarve [Satisfaction and loyalty of bank customers in Algarve] (doctoral dissertation). University of the Algarve, Faro, Portugal. Available online at: https://sapientia.ualg.pt/bitstream/10400.1/5826/1/Disserta%C3%A7%C3%A3o%20final%20PDF.pdf

Akter, M. S., Amin, A., Bhuiyan, M. R. I., Poli, T. A., and Hossain, R. (2023). Web based banking services on E-customer satisfaction in private banking sectors: a cross sectional study in developing economy. Migrat. Lett. 20, 894–911.

Almaiah, M. A., Al-Rahmi, A. M., Alturise, F., Alrawad, M., Alkhalaf, S., Lutfi, A., et al. (2022). Factors influencing the adoption of internet banking: An integration of ISSM and UTAUT with price value and perceived risk. Front. Psychol. 13, 919198. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.919198

AlSoufi, A., and Ali, H. (2014). Customers' perception of M-banking adoption in Kingdom of Bahrain: an empirical assessment of an extended TAM model. Int. J. Manag. Inform. Technol. 6, 1–13. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1403.2828

Amin, M. (2016). Internet banking service quality and its implication on e-customer satisfaction and e-customer loyalty. Int. J. Bank Market. 34, 280–306. doi: 10.1108/IJBM-10-2014-0139

Aramburu, I. A., and Pescador, I. G. (2019). The effects of corporate social responsibility on customer loyalty: the mediating effect of reputation in cooperative banks versus commercial banks in the Basque Country. J. Bus. Ethics 154, 701–719 doi: 10.1007/s10551-017-3438-1

Beerli, A., Martin, J. D., and Quintana, A. (2004). A model of customer loyalty in the retail banking market. Eur. J. Market. 38, 253–275. doi: 10.1108/03090560410511221

Bloemer, J., De Ruyter, K., and Peeters, P. (1998). Investigating drivers of bank loyalty: the complex relationship between image, service quality and satisfaction. Int. J. Bank Market. 16, 276–286. doi: 10.1108/02652329810245984

Botha, E., and Reyneke, M. (2016). “The influence of social presence on online purchase intention: an experiment with different product types,” in Looking Forward, Looking Back: Drawing on the Past to Shape the Future of Marketing, eds C. Campbell and J. J. Ma (Cham: Springer), 180–183. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-24184-5_49

Branco, M. C., and Rodrigues, L. L. (2006). Communication of corporate social responsibility by Portuguese banks: a legitimacy theory perspective. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 11, 232–248. doi: 10.1108/13563280610680821

Camillieri, S. J., and Grech, G. (2017). The relevance of age categories in explaining internet banking adoption rates and customers' attitudes towards the service. J. Appl. Finance Bank. 7, 29–47. Available online at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2934790

Caruana, A. (2002). Service loyalty: the effects of service quality and the mediating role of customer satisfaction. Eur. J. Market. 36, 811–828. doi: 10.1108/03090560210430818

Chaabane, A. M., and Pez, V. (2017). “Make me feel special”: are hierarchical loyalty programs a panacea for all brands? The role of brand concept. J. Retail. Cons. Serv. 38, 108–117. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2017.05.007

Chang, N. J., and Fong, C. M. (2010). Green product quality, green corporate image, green customer satisfaction, and green customer loyalty. Afr. J. Bus. Manage. 4, 2836–2844.

Chatzopolou, E., and de Kiewiet, A. (2020). Millennials' evaluation of corporate social responsibility: the wants and needs of the largest and most ethical generation. J. Cons. Behav. 20, 521–534. doi: 10.1002/cb.1882

Chen, Z., Li, Y., Wu, Y., and Luo, J. (2017). The transition from traditional banking to mobile internet finance: an organizational innovation perspective-a comparative study of Citibank and ICBC. Fin. Innovat. 3, 1–16. doi: 10.1186/s40854-017-0062-0

Dam, S. M., and Dam, T. C. (2021). Relationships between service quality, brand image, customer satisfaction, and customer loyalty. J. Asian Fin. Econ. Bus. 8, 585–593. doi: 10.13106/jafeb.2021.vol8.no3.0585

DECO (2012). Contas à ordem: Internet rende boas poupanç as. Available online at: http://www.deco.proteste.pt/nt/nc/comunicado-de-imprensa/contas-ordeminternet-rende-boas-poupancas

Englert, M. R., Koch, C., and Wüstemann, J. (2020). The effects of financial crisis on the organizational reputation of banks: an empirical analysis of newspaper articles. Bus. Soc. 59, 1519–1553. doi: 10.1177/0007650318816512

Ernst and Young Global Limited (2012). The Customer Takes Control. Global Banking Consumer Survey. Available online at: http://www.ey.com/za/en/newsroom/news-releases/2012—press-release—september—global-consumer-banking-survey-2012

Fatma, M., and Khan, I. (2023). CSR influence on brand loyalty in banking: the role of brand credibility and brand identification. Sustainability 15, 802. doi: 10.3390/su15010802

Floh, A., and Treiblmaier, H. (2006). What Keeps the e-banking Customer Loyal? A Multigroup Analysis of the Moderating Role of Consumer Characteristics on E-Loyalty in the Financial Service Industry. Available online at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2585491 (accessed March 26, 2006).

Forcadell, F. J., and Aracil, E. (2017). European Banks' reputation for corporate social responsibility. Corp. Soc. Respons. Environ. Manage. 24, 1–14. doi: 10.1002/csr.1402

Gaitán, J. A., Peral, B., and Jerónimo, M. R. (2015). Elderly and internet banking: an application of UTAUT2. J. Internet Bank. Commerce 20, 1–23.

Gill, C. (2008). Restoring consumer confidence in financial services. Int. J. Bank Market. 26, 148–152. doi: 10.1108/02652320810852790

Gliem, J. A., and Gliem, R. R. (2003). “Calculating, interpreting, and reporting Cronbach's alpha reliability Likert-type scales,” in Midwest Research-to-Practice Conference in Adult, Continuing, and Community Alsoufi & Ali (IUPUI).

Gong, Y., Xiao, J., Tang, X., and Li, J. (2023). How sustainable marketing influences the customer engagement and sustainable purchase intention? The moderating role of corporate social responsibility. Front. Psychol. 14, 1128686. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1128686

Habel, J., Schons, L. M., Alavi, S., and Wieseke, J. (2016). Warm glow or extra charge? The ambivalent effect of corporate social responsibility activities on customers' perceived price fairness. J. Market. 80, 84–105. doi: 10.1509/jm.14.0389

Hobeika, J., Khelladi, I., and Orhan, M. A. (2022). Analyzing the corporate social responsibility perception from customer relationship quality perspective. An application to the retail banking sector. Corp. Soc. Respons. Environ. Manage. 29, 2053–2064 doi: 10.1002/csr.2301

Jarvenpaa, S. L., Tractinsky, N., and Vitale, M. (2000). Consumer trust in an Internet store. Inform. Technol. Manage. 1, 45–71. doi: 10.1023/A:1019104520776

Jumaev, M., Kumar, D., and Hanaysha, J. R. (2012). Impact of relationship marketing on customer loyalty in the banking sector. Far East J. Psychol. Bus. 6, 36–55.

Kaura, V., Durga Prasad, C. S., and Sharma, S. (2015). Service quality, service convenience, price and fairness, customer loyalty, and the mediating role of customer satisfaction. Int. J. Bank Market. 33, 404–422. doi: 10.1108/IJBM-04-2014-0048

Kidron, A., and Kreis, Y. (2020). Listening to bank customers: the meaning of trust. Int. J. Qual. Serv. Sci. 12, 355–370. doi: 10.1108/IJQSS-10-2019-0120

Kim, Y.-K., and Sullivan, P. (2019). Emotional branding speaks to consumers' heart: the case of fashion brands. Fashion Textiles 6, 2. doi: 10.1186/s40691-018-0164-y

Leclercq-Machado, L., Alvarez-Risco, A., Esquerre-Botton, S., Almanza-Cruz, C., de las Mercedes Anderson-Seminario, M., Del-Aguila-Arcentales, S., et al. (2022). Effect of corporate social responsibility on consumer satisfaction and consumer loyalty of private banking companies in Peru. Sustainability 14, 9078. doi: 10.3390/su14159078

Lind, E. A. (2001). “Fairness heuristic theory: justice judgments as pivotal cognitions in organizational relations,” in Advances in Organization Justice, eds J. Greenberg and R. Cropanzano (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press), 56–88.

Liwan, N. A., Haliah, H., and Nirwana, N. (2023). Implementation of corporate social responsibility (CSR) in improving he reputation of islamic banking: a perspective of shariah enterprise theory. Dinasti Int. J. Econ. Fin. Account. 4, 592–602. doi: 10.38035/dijefa.v4i4.2044

Lymperopoulos, C., Chaniotakis, I. E., and Soureli, M. (2013). The role of price satisfaction in managing customer relationships: the case of financial services. Market. Intell. Plan. 31, 216–228. doi: 10.1108/02634501311324582

Mainardes, E. W., Costa, P. M. F., and Nossa, S. N. (2023). Customers' satisfaction with fintech services: evidence from Brazil. J. Fin. Serv. Mark. 28, 378–395. doi: 10.1057/s41264-022-00156-x

Martins, C., Oliveira, T., and Popovič, A. (2014). Understanding the Internet banking adoption: a unified theory of acceptance and use of technology and perceived risk application. Int. J. Inform. Manage. 34, 1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2013.06.002

Mattila, M., Karjaluoto, H., and Pento, T. (2003). Internet banking adoption among mature customers: early majority or laggards? J. Serv. Market. 17, 514–528. doi: 10.1108/08876040310486294

Matute-Vallejo, J., Bravo, R., and Pina, J. M. (2011). The influence of corporate social responsibility and price fairness on customer behaviour: evidence from the financial sector. Corp. Soc. Respons. Environ. Manage. 18, 317–331. doi: 10.1002/csr.247

Matzler, K., Würtele, A., and Renzl, B. (2006). Dimensions of price satisfaction: a study in the retail banking industry. Int. J. Bank Market. 24, 216–231. doi: 10.1108/02652320610671324

Mbama, C. I., Ezepue, P., Alboul, L., and Beer, M. (2018). Digital banking, customer experience and financial performance. UK bank managers' perceptions. J. Res. Interact. Market. 12, 432–451. doi: 10.1108/JRIM-01-2018-0026

Mir, R. A., Rameez, R., and Tahir, N. (2022). Measuring internet banking service quality: an empirical evidence. TQM J. 35, 492–518. doi: 10.1108/TQM-11-2021-0335

Moorman, C., Zaltman, G., and Deshpande, R. (1992). Relationships between providers and users of market research: the dynamics of trust within and between organizations. J. Market. Res. 29, 314–328. doi: 10.1177/002224379202900303

Nguyen, N., and Leblanc, G. (2001). Corporate image and corporate reputation in customers' retention decisions in services. J. Retail. Cons. Serv. 8, 227–236. doi: 10.1016/S0969-6989(00)00029-1

Ou, Y., and Verhoef, P. (2017). The impact of positive and negative emotions on loyalty intentions and their interactions with customer equity drivers. J. Bus. Res. 80, 106–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.07.011

Patel, R. J., and Siddiqui, A. (2023). Banking service quality literature: a bibliometric review and future research agenda. Qual. Res. Fin. Markets. 15, 732–756. doi: 10.1108/QRFM-01-2022-0008

Pérez, A., and Del Bosque, I. R. (2015). An integrative framework to understand how CSR affects customer loyalty through identification, emotions and satisfaction. J. Bus. Ethics 129, 571–584. doi: 10.1007/s10551-014-2177-9

Poovarasan, M. T., and Leslin, M. J. M. (2022). “Impact of e-banking and traditional banking services in banking industries,” in Commerce, Economics and Management, eds D. Sharma and R. P. Mahurkar (Lunawada: Infinity Publication), 167–169.

Raza, A., Saeed, A., Iqbal, M. K., Saeed, U., Sadiq, I., and Faraz, N. A. (2020). Linking corporate social responsibility to customer loyalty through co-creation and customer company identification: exploring sequential mediation mechanism. Sustainability 12, 2525. doi: 10.3390/su12062525

Roy, S. K., Devlin, J. F., and Sekhon, H. (2015). The impact of fairness on trustworthiness and trust in banking. J. Market. Manage. 31, 996–1017. doi: 10.1080/0267257X.2015.1036101

RuŽena, L., and Tomáš, U. (2014). Bank image structure: the relationship to consumer behaviour. J. Compet. 6, 18–35. doi: 10.7441/joc.2014.01.02

Samadi, M., and Yaghoob-Nejadi, A. (2009). A survey of the effect of consumers' perceived risk on purchase intention in e-shopping. Bus. Intell. J. 2, 261–275.

Sarfra, M., Abdullah, M. I., Arif, S., and Tariq, J. (2022). How corporate social responsibility enhance banking sector customer loyalty in digital environment? An empirical study. Etikonomi 21, 335–354. doi: 10.15408/etk.v21i2.24548

Seles, B. M. P., Jabbour, A. B., Jabbour, C. J. C., and Jugend, D. (2018). “In sickness and in health, in poverty and in wealth?”: Economic crises and CSR change management in difficult times. J. Organ. Change Manage. 318, 4–25. doi: 10.1108/JOCM-05-2017-0159

Sun, H., Rabbani, M. R., Ahmad, N., Sial, M. S., Cheng, G., Zia-Ud-Din, M., et al. (2020). CSR, co-creation and green consumer loyalty: are green banking initiatives important? A moderated mediation approach from an emerging economy. Sustainability 12, 10688. doi: 10.3390/su122410688

Thompson, P., and Cowton, C. J. (2004). Bringing the environment into bank lending: implications for environmental reporting. Brit. Account. Rev. 36, 197–218. doi: 10.1016/j.bar.2003.11.005

Vanhamme, J., Lindgreen, A., Reast, J., and Van Popering, N. (2012). To do well by doing good: improving corporate image through cause-related marketing. J. Bus. Ethics 109, 259–274. doi: 10.1007/s10551-011-1134-0

Vredenburg, J., Kapitan, S., Spry, A., and Kemper, J. A. (2020). Brands taking a stand: authentic brand activism or woke washing? J. Public Policy Market. 39, 444–460. doi: 10.1177/0743915620947359

Widodo, N. F. P., Burhany, D. I., Sumiyati, S., and Dahtiah, N. (2023). Enhancing financial performance of islamic banks in Indonesia: the mediating effect of green banking disclosure on corporate governance practices. Indonesian J. Econ. Manage. 3, 495–508. doi: 10.35313/ijem.v3i3.4886

Worcester, R. M. (1997). Managing the image of your bank: the glue that binds. Int. J. Bank Market. 15, 146–152. doi: 10.1108/02652329710175244

Wruuck, P., Speyer, B., and Hoffmann, R. (2013). Pricing in Retail Banking. Scope for Boosting Customer Satisfaction. Frankfurt am Main: Deutsche Bank AG. Available online at: https://www.dbresearch.com/PROD/RPS_EN-PROD/PROD0000000000451927/Pricing_in_retail_banking:_Scope_for_boosting_cust.pdf?undefinedandrealload=9RJlDVxNvN3O7UspERz~viz/qcSnAP5AlVHGTffMe9q6mSUuRNJsx1UAgffXZ2XJ

Wu, M. W., and Shen, C. H. (2013). Corporate social responsibility in the banking industry: motives and financial performance. J. Bank. Fin. 37, 3529–3547. doi: 10.1016/j.jbankfin.2013.04.023

Xia, L., Monroe, K. B., and Cox, J. L. (2004). The price is unfair! A conceptual framework of price fairness perceptions. J. Market. 68, 1–15. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.68.4.1.42733

Yee-Loong Chong, A., Ooi, K. B., Lin, B., and Tan, B. I. (2010). Online banking adoption: an empirical analysis. Int. J. Bank Market. 28, 267–287. doi: 10.1108/02652321011054963

Yuen, Y. Y., Yeow, P. H., Lim, N., and Saylani, N. (2010). Internet banking adoption: comparing developed and developing countries. J. Comput. Inform. Syst. 51, 52–61.

Zameer, H., Tara, A., Kausar, U., and Mohsin, A. (2015). Impact of service quality, corporate image and customer satisfaction towards customers' perceived value in the banking sector in Pakistan. Int. J. Bank Market. 33, 442–456. doi: 10.1108/IJBM-01-2014-0015

Zhang, Y. (2015). The impact of brand image on consumer behavior: a literature review. Open J. Bus. Manage. 3, 58–62. doi: 10.4236/ojbm.2015.31006

Keywords: banking sector, environmental and social causes, corporate social responsibility, corporate image, consumer satisfaction, consumer loyalty

Citation: Gaspar AD and Pinto JC (2024) The good bank: preference of banking institutions based on perceptions of corporate environmental and social causes. Front. Behav. Econ. 2:1330861. doi: 10.3389/frbhe.2023.1330861

Received: 08 November 2023; Accepted: 27 December 2023;

Published: 16 January 2024.

Edited by:

Pantelis C. Kostis, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, GreeceReviewed by:

Charalampos Basdekis, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, GreeceIoannis Katsampoxakis, University of the Aegean, Greece

Copyright © 2024 Gaspar and Pinto. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Augusta D. Gaspar, YXVndXN0YS5nYXNwYXJAdWNwLnB0

Augusta D. Gaspar

Augusta D. Gaspar Joana Carneiro Pinto

Joana Carneiro Pinto