- Institute for Wealth and Asset Management, School of Management and Law, Zurich University of Applied Sciences, Winterthur, Switzerland

In the recent years, data science methods have been developed considerably and have consequently found their way into many business processes in banking and finance. One example is the review and approval process of credit applications where they are employed with the aim to reduce rare but costly credit defaults in portfolios of loans. But there are challenges. Since defaults are rare events, it is—even with machine learning (ML) techniques—difficult to improve prediction accuracy and improvements are often marginal. Furthermore, while from an event prediction point of view, a non-default is the same as a default, from an economic point of view much more relevant to the end user it is not due to the high asymmetry in cost. Last, there are regulatory constraints when it comes to the adoption of advanced ML, hence the call for explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) issued by regulatory bodies like FINMA and BaFin. In our study, we will address these challenges. In particular, based on an exemplary use case, we show how ML methods can be adapted to the specific needs of credit assessment and how, in the case of strongly asymmetric costs of wrong forecasts, it makes sense to optimize not for accuracy but for an economic target function. We showcase this for two simple and ad hoc explainable ML algorithms, finding that in the case of credit approval, surprisingly high rejection rates contribute to maximizing profit.

1 Introduction

One of the most fundamental properties of risk in finance is its measurability and the fact that one can price it accurately. In the particular case of credit risk, the correct pricing is—for several reasons—quite a challenge: credit and risks as such are asymmetric and skewed toward large losses with low probability and small gains with high probability, resulting in a loss distribution exhibiting the so-called fat tails. Even in traditional banking, these fat tails are quite difficult to assess, and for modeling them correctly, high-quality data and very robust models are needed. This is even truer for the fast-growing peer-to-peer (P2P) lending space where data are quite often sparse, of low quality, and ambiguous (see, e.g., Suryono et al., 2019; Ziegler and Shneor, 2020). At the same time, P2P lenders have a completely different risk profile compared to traditional lenders, namely, although both banks and P2P platforms rely on scoring models for the purpose of estimating the probability of default of a loan, the incentive for model accuracy may differ significantly as in the context of the P2P lending platforms, in most cases, the credit risk is not born by the platform but rather solely by the investors. This, in turn, makes it imperative for the P2P lending platforms to correctly assess their risks, manage them accordingly, and make them transparent to the investors (Ahelegbey et al., 2019b). To overcome the challenges of low-quality, sparse credit data, P2P lenders seek more to employ ML techniques, hoping to achieve by that a higher prediction accuracy of potential defaulters, that is, reduce the already low number of defaults even further (Giudici et al., 2019). As we will detail, this poses a threefold problem: First, optimization in the tail of the loss distribution as such is difficult—because of data issues, error propagation, and accuracy restrictions. Second, just optimizing for the lowest number of defaults conditional to some lower accuracy bound will often result in a suboptimal economic situation, the cost/benefit ratio of defaulters and non-defaulters being highly asymmetrical. Third, the soaring use of advanced ML techniques in finance with the desired goal of higher prediction accuracy renders the decision process increasingly opaque. This, in turn, conflicts with the demands for transparency and explainability issued by regulatory bodies and supervisory authorities in finance (Bafin, 2020). Examining the definition of the “fair” risk premium as the economic payoff function, we immediately understand why:

Here, the cost of comparatively few defaults is balanced by the premium paid by many non-defaulters. This, in turn, implies that omitting a default is very “valuable” and might be done, from an economic point of view, at the cost of forgoing quite a lot of premium-paying business, that is, accepting a high false positive rate (FPR). To better understand this rationale, we only have to look at the most naive estimator for conducting credit business: accept all loans. In this case, the false positive rate will be zero—as will be, unfortunately, the true positive rate (TPR). Since defaults are (relatively) rare events, the accuracy of this naive estimator will be already quite high, although we accepted all of the defaulters. To bring down the number of accepted defaulters, thus increasing the TPR, we have to reject business, but this will go hand-in-hand with an increase of the FPR: since discrimination on a high level of accuracy is increasingly difficult, we will increasingly forgo non-defaulting business and thus income. Consequently, a substantial further gain in prediction accuracy is often simply not achievable, even when employing highly sophisticated ML techniques (compare, e.g., Giudici et al., 2019; Sariev and Germano, 2019; Sariev and Germano, 2020). Already here we can see the fundamental issue: since accepted defaults are much more costly than forgone non-defaulting business, the optimum with regard to the accuracy of predicting the number of defaults never can be the same as the optimum with regard to predicting the highest payoff. While the latter is what matters to any financial institution, the former is what usually gets optimized employing ML algorithms. In this study, we will show that the correct definition of the target function is quite crucial for any credit business and that optimizing along such an economic target function can drastically improve the profitability of the business at hand. Furthermore, we will demonstrate that this concept is quite agnostic with regard to the actual ML technique chosen for optimization and we will discuss this finding in the particular context of explainability and regulatory requirements. Particularly, we will show that the choice of easy-to-understand and intuitively explainable ML algorithms does not substantially compromise prediction accuracy, thus fulfilling both demands: high discriminating and prediction effectiveness as well as explainability. The article will be structured as follows. In Section 2, we will introduce and discuss the dataset we use for our analysis. Section 3 will elaborate on explainable artificial intelligence (XAI), highlight its most prominent characteristics, and comment on its increasing importance. In Section 4, we will employ different ML models to perform the actual prediction and the subsequent optimization, first with regard to number of defaults and second with regard to profit. Here, we will show in detail how different target functions affect the profit and loss (PnL) of the loan portfolio, and we will outline how the different target functions can be formulated for different ML techniques. Last but not least, we will show that this can be done using simple, explainable ML models, without relevant loss of accuracy or fidelity. Section 5 provides a summary and conclusion. Here, we will also outline possible business opportunities for FinTech companies with a clear focus on alternative data.

2 Data

The data under consideration is the dataset smaller_dataset.csv sourced from the FinTech-ho2020 project (www.fintech-ho2020.eu, Fintech-ho2020 (2019-2021)) from the External Credit Assessment Institution (ECAI) (see also Ahelegbey et al., 2019b; Ahelegbey et al., 2019a; Giudici et al., 2019). FinTech-ho2020 is a 2-year project (January 2019–December 2020) that developed a European knowledge-exchange platform aimed at introducing and testing common risk management solutions that automatize compliance of FinTech companies (RegTech) and increase the efficiency of supervisory activities (SupTech). The knowledge exchange platform under the FinTech-ho2020 project consists of SubTech, RegTech, and research workshops. The dataset consists of a total of 4,514 loans, 4,016 or 88.97% of which are not defaulted (indicated by the value 0 of the variable status in the dataset), and 498 or 11.03% are defaulted (indicated by the value 1 of the variable status). Since the dataset does not contain detailed information about the size of the individual loans, we assume, for simplicity, that all loans are of equal size. If actual individual loan sizes are given, they certainly should be used in the training process of the machine learning algorithm as well as in the calculation of the resulting profit. However, as long as the distribution of loan sizes in the groups of defaulting and non-defaulting loans are roughly identical, replacing the actual loan sizes by their ensemble average seems justifiable. We split the total of 4,514 loans into an (in-sample) training set of

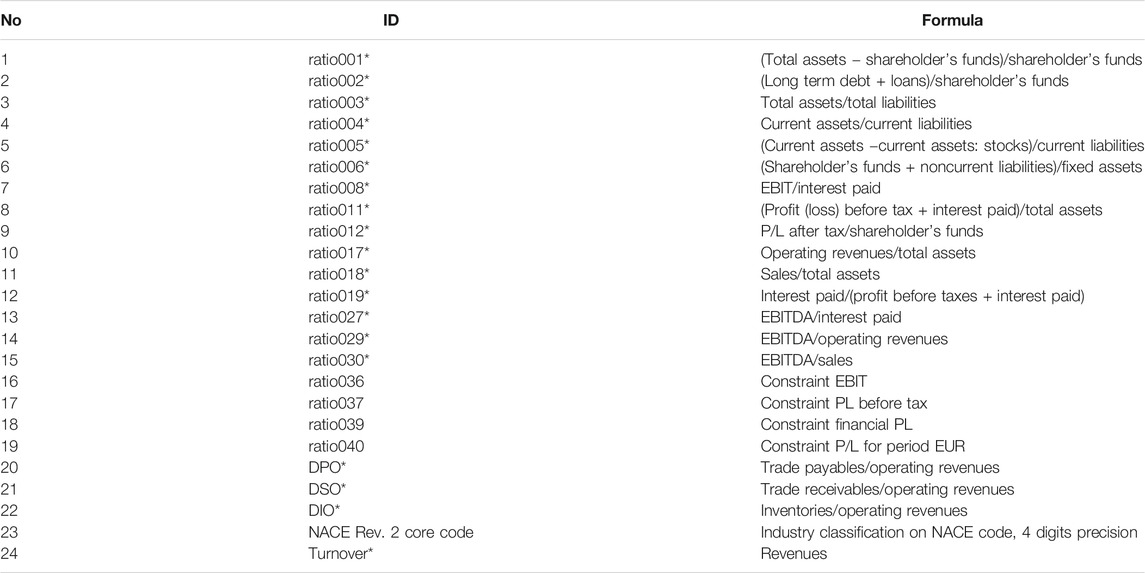

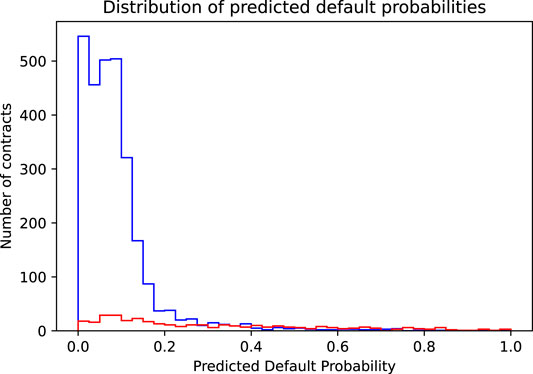

TABLE 1. List of the 24 loan features, with their respective descriptions. Only features marked with * are used as discriminators.

TABLE 2. List of the 19 features/ratios used for loan default analysis, sorted ascending by the p-values calculated using Welch’s t test.

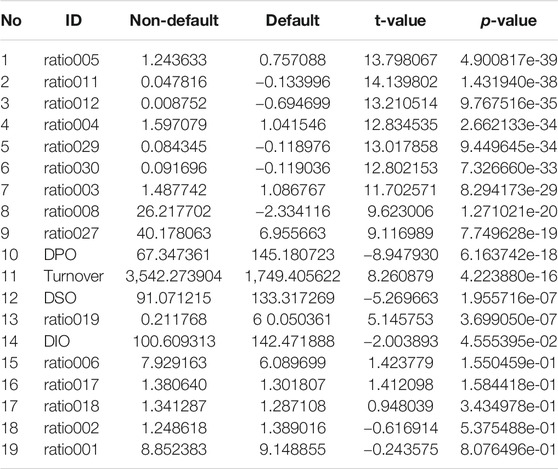

FIGURE 1. Scatter plots and densities for the two ratios with the best p-values and for the two ratios with worst p-values, from left to right, respectively.

3 Discussion on XAI and Econometrics

As widely acknowledged, machine learning (ML) is increasingly used in finance and with very good results at that (Andriosopoulos et al., 2019). One of the prime examples is, of course, the process of credit decisions on sparse datasets of low quality (Lessmann et al., 2015). But there is a fundamental disconnect at the core between machine learning models and statistical or econometric models usually applied when analyzing data (Athey and Imbens, 2019): econometrics is centered around explainability. The very concept starts with an econometric model derived from theoretical reasoning and uses empirical data to “prove” and quantitatively find causal relations between explanatory variables

4 Optimizing With Machine Learning

In this section, we will use two machine learning models, a logistic regression and a decision tree, to identify defaulting and non-defaulting loan contracts. We keep both models as simple as possible: first, because this guarantees a certain level of ad hoc explainability as discussed in the previous section, and second, because more elaborate models often fail to significantly improve the models’ performance while quickly compromising its transparency. For the same reason, we do not try to optimize the models by hyperparameter tuning. We use a standard logistic regression model without regularization1 and a simple decision tree of depth 3 grown without any further constraints.2 For both models, we use all of the ratios included in the dataset as features (c.f. Section 2) and the variable status as the label to be predicted. We use

4.1 Logistic Regression

We use the following logistic regression model to predict a contract’s probability of default given its features

The parameters

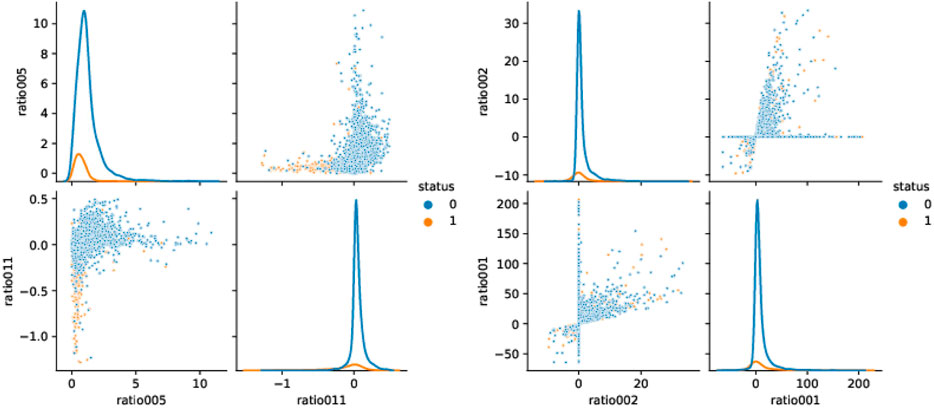

FIGURE 2. Shown is the distribution of the predicted default probabilities separately for contracts that actually do not default (blue histogram) and for contracts that actually do default (red histogram).

4.1.1 Accuracy Maximizing Threshold

We now proceed to find the threshold that leads to the highest possible prediction accuracy. Mathematically speaking, this simply means to maximize the target function “prediction accuracy” as a function of the chosen threshold

where

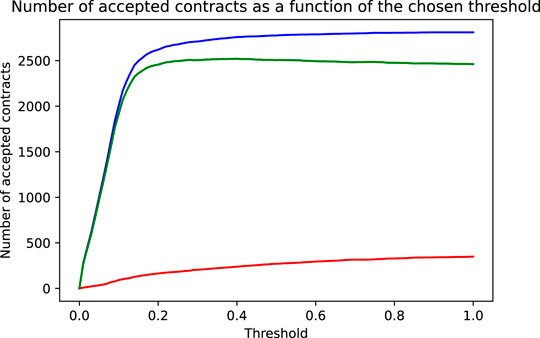

FIGURE 3. As a function of the chosen threshold are shown the number of correctly accepted non-defaulting contracts (blue line), the number of incorrectly accepted defaulting contracts (red line) and the net effect, that is, the difference of correct and incorrect decisions reflecting the models accuracy (green line).

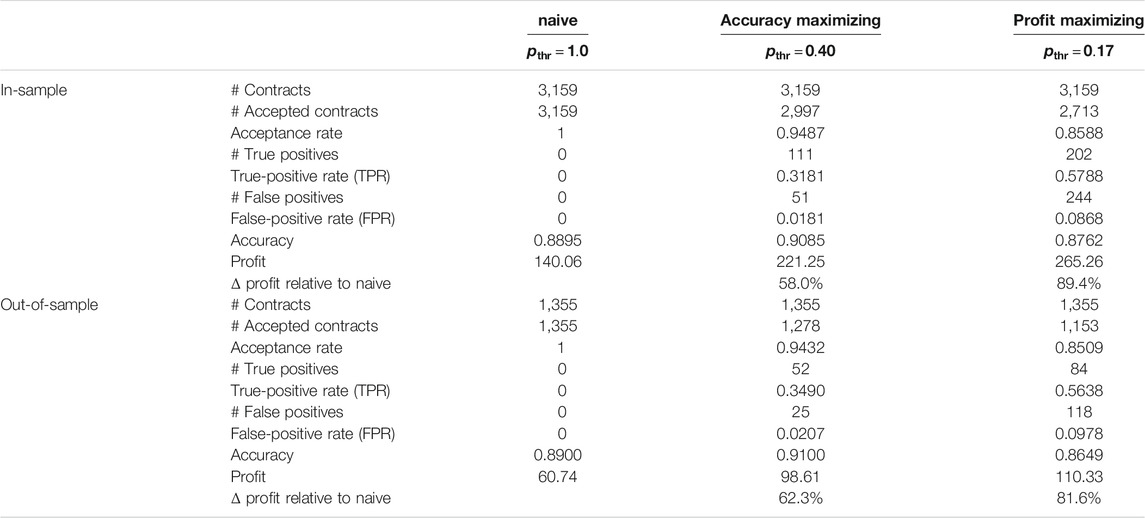

TABLE 3. Overview of the in- and out-of-sample performance figures of logistic regression models with different thresholds

4.1.2 Weighting of Contracts and Profit Maximization

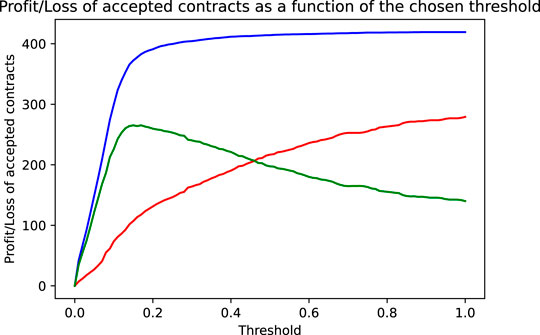

We have seen above that using an accuracy maximizing threshold improves the model’s accuracy only slightly but did increase the resulting profit considerably. This was mainly due to the fact that the model was able to greatly reduce the bank’s loss by correctly identifying and rejecting defaulting contracts. This gives rise to the idea to try to choose the threshold not in a way to maximize accuracy, but in a way to directly maximize profit. Mathematically speaking, this means maximizing the profit target function

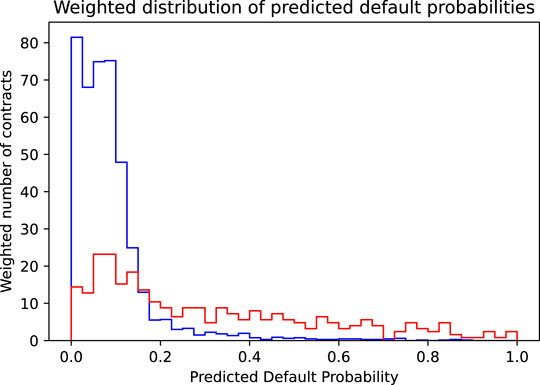

Again, we illustrate this maximization process graphically. The starting point to find the accuracy maximizing threshold was Figure 2, showing the distribution of the predicted default probabilities. Implicitly and by construction, in this histogram, every contract is given the same weight. This is the appropriate view if we want to judge the model’s accuracy where every wrong or correct decision contributes equally. However, if we focus on profit, we must consider the completely different cost of wrongly accepted defaulting contracts vs. the cost of wrongly denied non-defaulting contracts. The solution is to weigh each contract with the dollar cost resulting if it is wrongly classified, that is, we weigh the non-defaulting contracts by the income we lose, if we reject them (

FIGURE 4. Shown is the distribution of the predicted default probabilities, where the distribution for the actually non-defaulting contracts (blue histogram) is weighted by their income (corresponding to the risk premium plus the spread) and the distribution of the actually defaulting contracts (red histogram) is weighted by their loss (corresponding to the face value reduced by the recovery rate).

FIGURE 5. As a function of the chosen threshold are shown the income by the accepted non-defaulting contracts (blue line), the loss incurred by the accepted defaulting contracts (red line), and the net effect, that is, the bank’s profit (income less loss, green line).

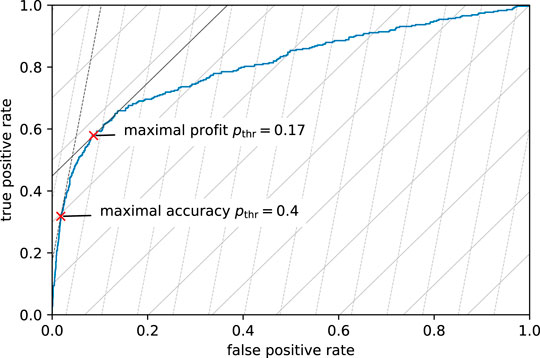

4.1.3 Visualization of Accuracy and Profit Maximization in the ROC Diagram

The logistic regression model predicts probabilities and allows for a continuous shift of the decision threshold. Such a model’s quality is often judged by looking at its receiver operating characteristic (ROC). Figure 6 shows the in-sample ROC diagram of our logistic regression model. The ROC curve shows the model’s true positive rate (TPR) and false positive rate (FPR) for thresholds between 0 and 1. This curve starts in the lower left corner at a threshold of 1.0, representing a model that accepts all contracts and consequently has 0 TPR (no defaulting contracts are identified) and 0 FPR (no non-defaulting contracts are wrongly rejected). As the threshold is lowered below 1.0, more and more contracts are rejected. This leads to a (fast) increase of the TPR (many defaulting contracts start to be correctly identified) but also to a (slow) increase of the FPR (some non-defaulting contracts are wrongly rejected). Together, this leads to a steep increase of the ROC curve. As the threshold is decreased further, the increase of the TPR slows down, while the increase of the FPR speeds up, leading to a flattening of the ROC curve until it reaches a TPR and FPR of 1 at the threshold 0 (rejecting all contracts). The quality of the logistic regression model can be judged based on the shape of the ROC curve. The more the ROC curve is bent to the upper left corner (maximal TPR with minimal FPR), the better the model. The performance figure is the area under the ROC curve, the AUC. For our logistic regression model, the in-sample AUC is 0.8058. However, the choice of the best possible threshold depends on the target function to be optimized. Both of the target functions we investigate, accuracy and profit maximization, depend on the number of correct and wrong decisions made by the model, that is, on the model’s TPR and FPR. The steep dashed lines in Figure 6 represent combinations of TPR and FPR that yield the same accuracy. We call these iso-accuracy lines. Since in our training sample there are approximately 8 times more non-defaulting contracts than defaulting contracts, an increase of the FPR by one percentage point must be compensated by an increase of the TPR by about 8 percentage points to achieve the same accuracy. Thus, the iso-accuracy lines have a slope of approximately 8. Iso-accuracy lines close to the upper left corner of the diagram correspond to high accuracy, while those that are closer to the lower right corner correspond to lower accuracies. The model’s best possible threshold is, therefore, achieved at the TPR/FPR combination where the iso-accuracy line lays tangent to the model’s ROC curve (c.f. dark dashed line in Figure 6). This point is indicated in Figure 6 by a red cross and corresponds to a threshold of 0.4 where the model achieves a TPR of 0.3181 and an FPR of 0.0181 (c.f. Table 3). As the main focus of the bank is not to maximize prediction accuracy but rather to maximize its profit, we added in the ROC diagram lines of equal profit, iso-profit lines (flat solid lines in Figure 6). Since wrongly accepted defaulting contracts are about five times as expensive as wrongly rejected non-defaulting contracts, the slope of the iso-profit lines is by a factor of 5.36 lower than the slope of the iso-accuracy lines. The slope of the iso-profit lines is

FIGURE 6. In-sample ROC curve of the logistic regression model (blue curve). Added are the curves of equal accuracy (steep dashed lines) and the curves of equal profit (flat solid lines). The lines more to the upper left represent spots of higher accuracy and profit, lines more to the lower right represent spots of lower accuracy and profit. The two red crosses represent the TPR and FPR of models with thresholds that lead to maximal accuracy or maximal profit.

4.2 Predicting Defaults Using a Single Decision Tree

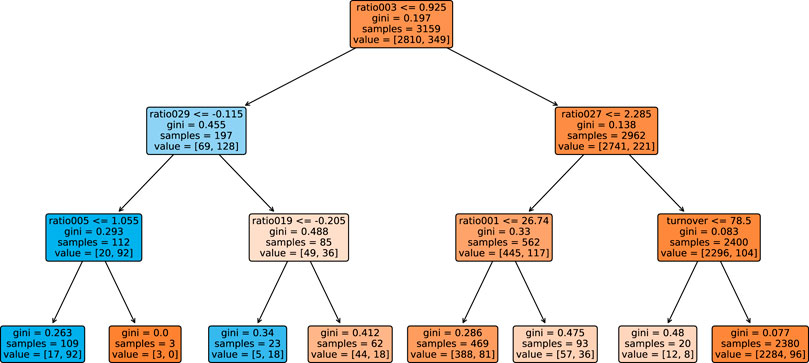

As an alternative to the logistic regression model, we illustrate the steps necessary to calibrate to a profit maximizing model using another machine learning model, a single decision tree. Even though this model is even simpler than the logistic regression and, thus, also more explainable and transparent in its decisions than the logistic regression model, it is still capable to yield significant performance improvements by tuning it to profit maximization. We use a simple tree with a depth of 3 and minimize the Gini impurity measure to grow the tree. No further restrictions were imposed while growing the tree.

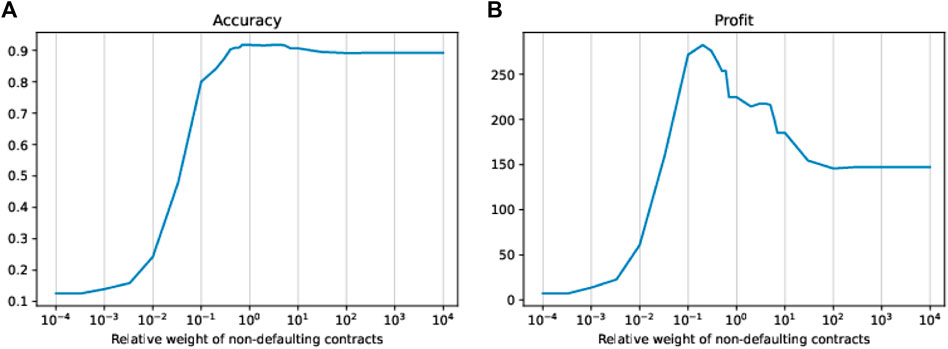

4.2.1 Tuning the Tree Growth to Maximize Accuracy and Profit

Since the tree we use is quite shallow (depth of 3 leading to just eight leaves), it does not make a lot of sense to tune the decision threshold applied in the leaves to decide whether to accept or reject a contract. We, therefore, leave the threshold fixed at 0.5, that is, whether a new contract is accepted or rejected is decided upon the simple majority of the contracts of the training set in the leaf to which the new contract is assigned. However, we can tune the growth of the decision tree by using weights for the two classes of contracts in the training data. We do this by tuning the relative weight of the non-defaulting contracts relative to the defaulting ones in a range from

FIGURE 7. In-sample accuracy (A) and in-sample profit (B) of trees as a function of different relative weights of the non-defaulting contracts.

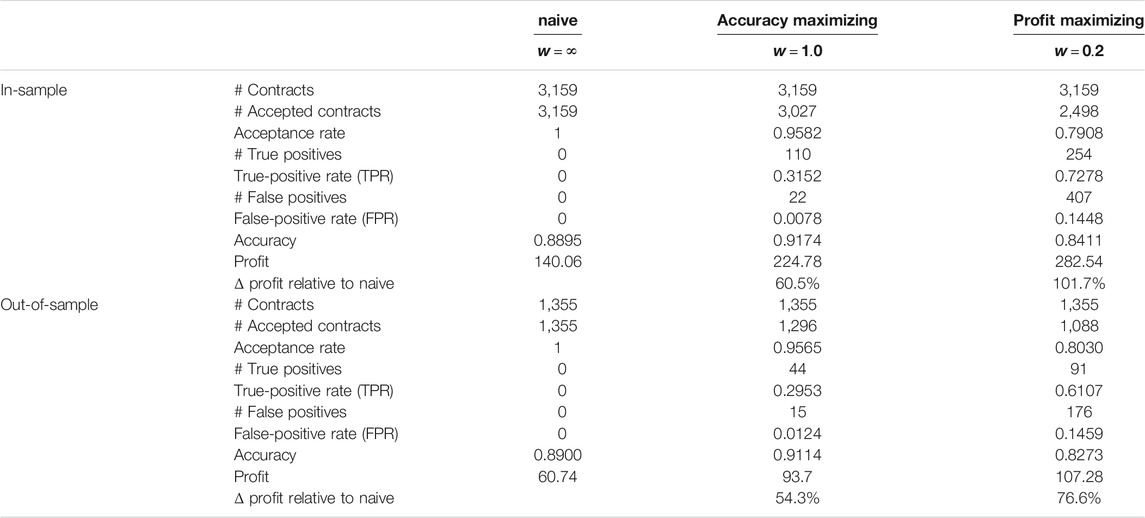

TABLE 4. Overview of the in- and out-of-sample performance figures of decision tree models with different weightings w of the non-defaulting contracts.

4.2.2 Comparison of the Accuracy Maximizing and Profit Maximizing Trees

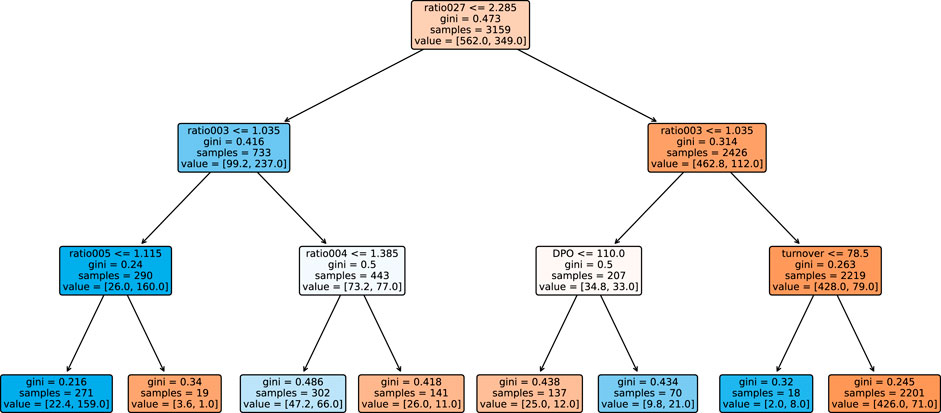

Figures 8, 9 show the decision trees at the accuracy maximizing weight of 1 and the profit maximizing weight of 0.2. The accuracy maximizing tree identifies approximately one third of the defaulting contracts only in leaves where defaults represent a clear majority. The remaining two thirds of defaults remain hidden in leaves where they are mixed with a majority of non-defaulting contracts. Even though a large majority of the defaulting contracts is wrongly classified due to the low number of defaults in our highly unbalanced dataset, this still results in a tree with maximum in- and out-of-sample prediction accuracy. However, for the task of profit maximization, the defaults are assigned a much larger (relative) weight. Therefore, the profit maximizing tree “tries much harder” to correctly identify and separate more of the defaulting contracts. Using only four of the available 19 ratios, namely ratio003, ratio029, ratio005, and ratio019, the accuracy maximizing quickly arrives at branches and leaves with clear majorities indicated by the more saturated colors in Figure 8. The profit maximizing tree needs six different ratios, namely ratio027, ratio003, ratio005, ratio004, DPO, and turnover, and still ends up in quite some leaves with rather weak majorities indicated by the less saturated colors. It is instructive to note that, confirming our expectation, most of the ratios used in the branches of the trees are among the most significant discriminators as identified in our statistical analysis in Table 2. In fact, the most relevant ratios as identified during the growth process of the tree are asset-liability ratios (ratio003 and ratio005) and earnings ratios (ratio027 and ratio029). This is consistent with the traditional wisdom of banking experts that these types of ratios are among the most relevant ones when it comes to judging the credit worthiness of a company.

FIGURE 8. Tree grown using the dataset, where non-defaulting and defaulting contracts are weighted equally. This tree maximizes prediction accuracy.

FIGURE 9. Tree grown using the dataset, where the weight of the non-defaulting contracts is reduced by a factor of 0.2 relative to the defaulting contracts. This tree maximizes the banks profit.

5 Summary and Conclusion

For many applications, as for example, credit decisions made by banks, the output of the used models has to be sufficiently transparent and understandable. This often prevents or at least complicates the use of many advanced and nontransparent machine learning models. However, especially in the case of highly unbalanced datasets one is typically confronted with in credit applications, already the naive procedure (simply basing the decision upon the majority class in the training data) or the use of simple, transparent and ad hoc explainable machine learning algorithms can easily achieve high prediction accuracy that is difficult to significantly be enhanced by more complex and nontransparent algorithms. On the other hand, for users of machine learning models, it is often not prediction accuracy which is of most concern, but each application has its own, business specific target function to be optimized. In the use-case studied in this study, the relevant target function is the profit the bank can draw from its credit business. While application of simple machine learning algorithms only minimally improves prediction accuracy over the naive case of accepting all business, it quickly shows a considerable positive effect on the banks profit by identifying and rejecting some of the defaulting contracts. However, neither the often applied pure accuracy maximization nor the balancing of the training dataset to equal shares of defaulting and non-defaulting contracts leads to the maximal profit. In order to maximize profit, it is crucial to include the user’s target function in the choice of the best possible model and parameters. In the case of the logistic regression, we tuned the threshold distinguishing between accepted and rejected contracts to maximize the given profit target function. In case of the decision tree, we used weighting to balance the data not to equal shares of both types of contracts but to reflect the impact of the model’s correct and wrong decisions on the target function, the bank’s profit. As a result, we have seen that applying simple machine learning algorithms that are tuned to profit maximization can increase the banks profit on new business considerably. For both models studied, the bank’s profit could be increased by up to 80% relative to the naive case of accepting all business. We observe that the profit-maximizing models tend to reject surprisingly many of the contracts, that is, these models accept a lot of falsely rejected good business in order to sort out a few more of the defaulting contracts. This is because the cost of a wrongly accepted defaulting contract by far outweighs the loss incurred by falsely rejected good, non-defaulting contract (forgone business). With our dataset and models, up to 20% of all contracts are rejected, approximately two thirds of which are actually non-defaulting contracts. This could lead to new business opportunities, for example, for peer-to-peer lending platforms, that might try to use additional alternative data and advanced machine learning techniques to identify some of the remaining good business within the many contracts rejected by banks. To conclude, from a purely theoretical point of view, the observations made in this study of course can be translated to any use case where one has to deal with unbalanced datasets and target functions that depend in a highly asymmetrical way on the model’s decisions.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. These data can be found here: www.fintech-ho2020.eu, Fintech-ho2020 (2019–2021), smaller_dataset.csv, https://github.com/danpele/FINTECH_HO_2020/tree/main/3.%20Use%20Cases/1.%20Big%20Data%20Analytics/Use%20Case%20I_BDA/Replication_code_BDA_I.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

This research has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program FIN-TECH: A Financial supervision and Technology compliance training program under the grant agreement No 825215 (Topic: ICT-35-2018, Type of action: CSA). Moreover, this article is also based upon the work from the Innosuisse Project 41084.1 IP-SBM Towards Explainable Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Credit Risk Management. Furthermore, this article is based upon work from COST Action 19130 FinTech and Artificial Intelligence in Finance, supported by COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology), www.cost.eu.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the management committee members of the COST Action CA19130 FinTech and Artificial Intelligence in Finance as well as to the speakers and participants of the 5th European COST Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Finance and Industry, which took place at the Zurich University of Applied Sciences, Switzerland, in September 2020. The authors would further like to thank Branka Hadji Misheva for fruitful discussions and valuable comments.

Footnotes

1Optimal L2 regularization using cross-validation did not significantly change the performance of the model (measured in terms of AUC), nor would it change any of our discussions and conclusions made below.

2Using cross-validation, we found the optimal depth to be in a range between two and four splits. Larger trees tend to overfit the training data while smaller trees significantly underperform.

3We use a stratified split to keep the ratio of defaulting contracts in the training set and test set identical.

4In fact, 93% of the non-defaulting contracts had predicted default probabilities below 20%, while this was the case for only 47% of the defaulting contracts.

5Note that balancing the training data to equal shares of defaulting and non-defaulting contracts would correspond to a weight of

References

Ahelegbey, D. F., Giudici, P., and Hadji-Misheva, B. (2019a). Factorial Network Models to Improve P2p Credit Risk Management. Front. Artif. Intell. 2, 8. doi:10.3389/frai.2019.00008

Ahelegbey, D. F., Giudici, P., and Hadji-Misheva, B. (2019b). Latent Factor Models for Credit Scoring in P2p Systems. Physica A: Stat. Mech. its Appl. 522, 112–121. doi:10.1016/j.physa.2019.01.130

Andriosopoulos, D., Doumpos, M., Pardalos, P. M., and Zopounidis, C. (2019). Computational Approaches and Data Analytics in Financial Services: A Literature Review. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 70, 1581–1599. doi:10.1080/01605682.2019.1595193

Arrieta, A. B., Díaz-Rodríguez, N., Del Ser, J., Bennetot, A., Tabik, S., Barbado, A., et al. (2020). Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI): Concepts, Taxonomies, Opportunities and Challenges toward Responsible AI. Inf. Fusion 58, 82–115. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2019.12.012

Athey, S., and Imbens, G. W. (2019). Machine Learning Methods that Economists Should Know about. Annu. Rev. Econ. 11, 685–725. doi:10.1146/annurev-economics-080217-053433

Athey, S. (2018). The Impact of Machine Learning on Economics. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press.

Bafin, F. F. S. A. (2020). Big Data Meets Artificial Intelligence. Challenges and Implications for the Supervision and Regulation of Financial servicesTech. Rep. Germany: Federal Financial Supervisory Authority - BAFIN.

Bussmann, N., Giudici, P., Marinelli, D., and Papenbrock, J. (2020). Explainable AI in Fintech Risk Management. Front. Artif. Intell. 3, 26. doi:10.3389/frai.2020.00026

Carvalho, D. V., Pereira, E. M., and Cardoso, J. S. (2019). Machine Learning Interpretability: A Survey on Methods and Metrics. Electronics 8, 832. doi:10.3390/electronics8080832

Fintech-ho2020 (2019-2021). Fintech-ho2020 Project, a Financial Supervision and Technology Compliance Training Programme, Smaller_dataset.csv

Giudici, P., Hadji-Misheva, B., and Spelta, A. (2019). Network Based Scoring Models to Improve Credit Risk Management in Peer to Peer Lending Platforms. Front. Artif. Intell. 2, 3. doi:10.3389/frai.2019.00003

Greene, W. H. (2008). Econometric Analysis. 6th Edition. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Lessmann, S., Baesens, B., Seow, H.-V., and Thomas, L. C. (2015). Benchmarking State-Of-The-Art Classification Algorithms for Credit Scoring: An Update of Research. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 247, 124–136. doi:10.1016/j.ejor.2015.05.030

Lundberg, S. M., and Lee, S.-I. (2017). “A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions,” in NIPS 17: Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, 4768–477.

Ribeiro, M. T., Singh, S., and Guestrin, C. (2016). “Why Should I Trust You?: Explaining the Predictions of Any Classifier,” in KDD ’16: Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA. doi:10.1145/2939672.2939778

Sariev, E., and Germano, G. (2019). An Innovative Feature Selection Method for Support Vector Machines and its Test on the Estimation of the Credit Risk of Default. Rev. Financ. Econ. 37, 404–427. doi:10.1002/rfe.1049

Sariev, E., and Germano, G. (2020). Bayesian Regularized Artificial Neural Networks for the Estimation of the Probability of Default. Quantitative Finance 20, 311–328. doi:10.1080/14697688.2019.1633014

Keywords: machine learning, XAI, credit default, P2P lending, FinTech

Citation: Gramespacher T and Posth J-A (2021) Employing Explainable AI to Optimize the Return Target Function of a Loan Portfolio. Front. Artif. Intell. 4:693022. doi: 10.3389/frai.2021.693022

Received: 09 April 2021; Accepted: 17 May 2021;

Published: 15 June 2021.

Edited by:

Jochen Papenbrock, NVIDIA GmbH, GermanyReviewed by:

Hayette Gatfaoui, IESEG School of Management, FranceGuido Germano, University College London, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2021 Gramespacher and Posth. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Thomas Gramespacher, Z3JhdEB6aGF3LmNo

Thomas Gramespacher

Thomas Gramespacher Jan-Alexander Posth

Jan-Alexander Posth