- 1Recovery Research Institute, Center for Addiction Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, United States

- 2Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States

Introduction: Educational settings represent a prime opportunity for reaching adolescents and young adults (ages 12–27) experiencing substance use disorders (SUD). Recovery high schools (RHSs) were established to help adolescents in recovery finish their education while maintaining alcohol and other drug (AOD) abstinence and collegiate recovery programs (CRPs) were implemented for college and university students. With the continued proliferation of these programs, this review synthesizes the empirical literature on the impact of both types of educational recovery supports for youth.

Method: This review's methodology was based on a previous Campbell review on the same topic from 2017. We searched five public databases (May 2024), used PRISMA 2020 reporting guidelines, and followed Campbell Collaboration guidelines including Synthesis Without Meta-Analysis. Eligible studies focused on adolescent/emerging adult participants in RHSs or CRPs. Any outcome broadly related to SUD recovery was eligible. We included quantitative or mixed methods studies and allowed for cost-benefit/cost-effectiveness designs. Data from eligible studies were extracted in duplicate and assessed for quality (Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies) by four review team members. Two cost-benefit/cost-effectiveness studies included in the CRP review were rated for quality using a separate tool appropriate for these designs by a single reviewer.

Results: We identified 37 manuscripts representing 25 unique studies focused on RHS (K = 7: N = 14,209) or CRPs (K = 18: N = 2,795). In the RHS studies, participants were predominantly White (41%) and females represented 29% of the sample. No studies met the criteria for low risk of bias. In the CRP studies, participants were predominately white (89%) and had slightly less female than male participants (45%). 11 of the 16 studies that did not use cost-benefit analysis were rated as high risk of bias. The quality rating of the two studies using cost-benefit designs indicated that both studies had fairly rigorous approaches.

Discussion: This research base suggests that students who participate in RHSs and CRPs may demonstrate reductions in AOD use, and improvements in social and academic outcomes, although given the existing research designs, statements about the incremental public health utility of investing in these programs relative to other approaches of equal intensity or duration cannot be made with confidence.

1 Introduction

In 2019, over 70,000 youth enrolled in publicly funded substance use disorder (SUD) treatment in the United States, and an additional 1.9 million needed treatment but did not receive it (1, 2). More effective engagement of youth in seeking treatment for alcohol and other drug (AOD) use and sustained recovery support would have major public health benefits. Educational settings represent a prime opportunity for reaching adolescents and young adults experiencing heavy or problematic substance use including those with an SUD, given they spend the majority of their time in such settings. Although these educational environments present an opportunity to identify and support youth in need of treatment and recovery services, they also pose barriers due to the availability of substances on campuses and the social influence of peer groups who use substances (3, 4). In response to this need, recovery high schools (RHSs) were established to help adolescents in or seeking SUD recovery finish their high school education while maintaining alcohol and other drug abstinence (5) and collegiate recovery programs (CRPs) were implemented for college and university students (6, 7). It has now been a decade since federal offices formally recognized RHSs and CRPs as important supports for youth recovery (8).

These education-based recovery support services emerged in the 1970s to support students in their recovery while also helping them achieve their academic goals (7). Recovery high schools vary in size and structure, with enrollment typically ranging from 2 to 115 students (9), and exist as both independent schools and programs embedded within another school (10). They often offer much of what a traditional high school environment offers: classes, coursework, and a high school diploma. Yet, they also offer recovery-focused programming such as recovery group check-ins, individual counseling or links to mental health supports, opportunities for volunteer community services, and ensure regular connection/check-ins with parents or guardians (7). Collegiate recovery programs (CRP) also range in size and structure, with typical student enrollment ranging from 10 to 50 students (4, 11). They do not directly offer coursework or a college diploma but instead operate on college campuses and support students in recovery pursuing university degrees. They offer recovery supports such as sober housing/dormitories, recovery specific meeting spaces/congregational areas, AOD-free social events, group recovery meetings, and scholarships and/or work-study opportunities (12, 13). Some CRPs are membership driven where a period of abstinence is required to become an official member, while others have a more open membership policy. Whereas recovery high schools are professionally led, CRPs can be peer-driven, with a limited professional staff (10, 11, 14, 15). The underlying philosophy of both CRPs and RHSs is that by surrounding young people with others seeking recovery or those farther along in recovery (e.g., advanced students, staff) they will form new, pro-recovery social network connections that will reduce engagement with pro-substance use peers and serve to reinforce substance use disorder recovery (5).

Recovery capital refers to the resources necessary to initiate and sustain recovery (16–18). This construct provides an ecological framework that outlines different types of resources at different levels: human, financial, social, and community recovery capital. Both RHSs and CRPs are positioned as sources of community recovery capital, or as resources and supports located in the local community which are recovery supportive settings and can link their participants to an assortment of recovery supportive activities and peers. They are posited to support recovery through several different mechanisms and to address a multitude of related outcomes. A previously published recovery capital-oriented logic model of CRPs (13) described how CRPs could address personal, social, and community-level barriers of students in collegiate environments to support accrual of recovery capital through a variety of programming options. RHSs can also offer a similar way of building recovery capital. For example, in an RHS, a student can work towards completing their coursework for a high school diploma, building their skillset and motivation (human or personal recovery capital). Identifying with similar age peers, making pro-recovery peer connections, and seeing recovery modeled in others can help to build new relationships and help satisfy recovery-specific developmental needs related to esteem and belonging (19, 20), as well as boost their social recovery capital. Being in an environment with trusted adults who understand the unique needs of students in recovery, and may be in recovery themselves, can offer another facet of social recovery capital. RHSs may also serve as a bridge to broader community services, for example, to help link students to services that address basic needs (e.g., food pantries, stable housing).

Though no single model for RHSs or CRPs exists, education-based recovery support services have continued to grow in recent years, with over 40 recovery high schools currently in operation (21), and over 100 CRPs in development or operation in the United States (22). This review aims to synthesize the existing empirical literature on the impact of both types of educational recovery supports for youth and provide areas for future research direction.

1.1 Aim

A previous Campbell systematic review demonstrated a growth in the empirical literature on RHSs and CRPs within recent years and indicated potential for programming to result in a variety of positive outcomes for their participants (6). Yet, that review had a narrow focus on comparative research study designs and was published in 2018 (with a search from 2017); given these programs have been increasingly implemented across the United States and even globally, there was a need to return to the literature and synthesize any updates since that review.

2 Methods

This review was based on the methods used in a previously published Campbell review conducted by the first author [Hennessy et al. (23)], but given time constraints, we were unable to preregister a new protocol. We used the PRISMA reporting guidelines (24) to report all aspects of the review, including the study inclusion/exclusion process and followed Campbell Collaboration best practice guidelines for systematic reviews (25, 26). Throughout the manuscript and tables, we use standard review convention (27) to refer to the number of studies (K) and to the number of participants (N).

2.1 Inclusion criteria

Participants, Intervention, and Comparator. Eligible studies focused on adolescent and emerging adult participants engaged in recovery high schools (RHSs) for high school students in AOD use recovery or collegiate recovery programs/collegiate recovery communities (CRCs/CRPs) for college students in AOD use recovery. Studies needed to directly identify the program as an RHS or CRP for students in recovery. There were no eligibility restrictions for the comparison groups, provided one was present.

2.1.1 Inclusion criteria: outcomes

If a study focused on and reported quantifiable participant outcomes related to SUD recovery, it was deemed eligible. Studies that only focused on the organizational functioning of RHS/CRPs were not eligible. Any outcome broadly related to AOD use recovery was eligible for inclusion. We anticipated for example, outcomes related to substance use (e.g., abstinence, quantity, frequency), academics (e.g., grades/grade point average), criminal history/behavior (e.g., interaction with the criminal justice system), and broader indicators of quality of life and recovery capital.

2.1.2 Inclusion criteria: study design, setting, and timing

We included quantitative or mixed methods studies and allowed for cost benefit or cost effectiveness study designs. Given the difficulty of randomizing participants to these programs, we anticipated primarily quasi-experimental designs and few randomized controlled trials. Single group designed studies were also eligible. Studies that were solely qualitative in nature were not eligible. There were no restrictions on the study setting or timing (e.g., cross-sectional and longitudinal studies were both included as were studies from any timepoint).

2.2 Search

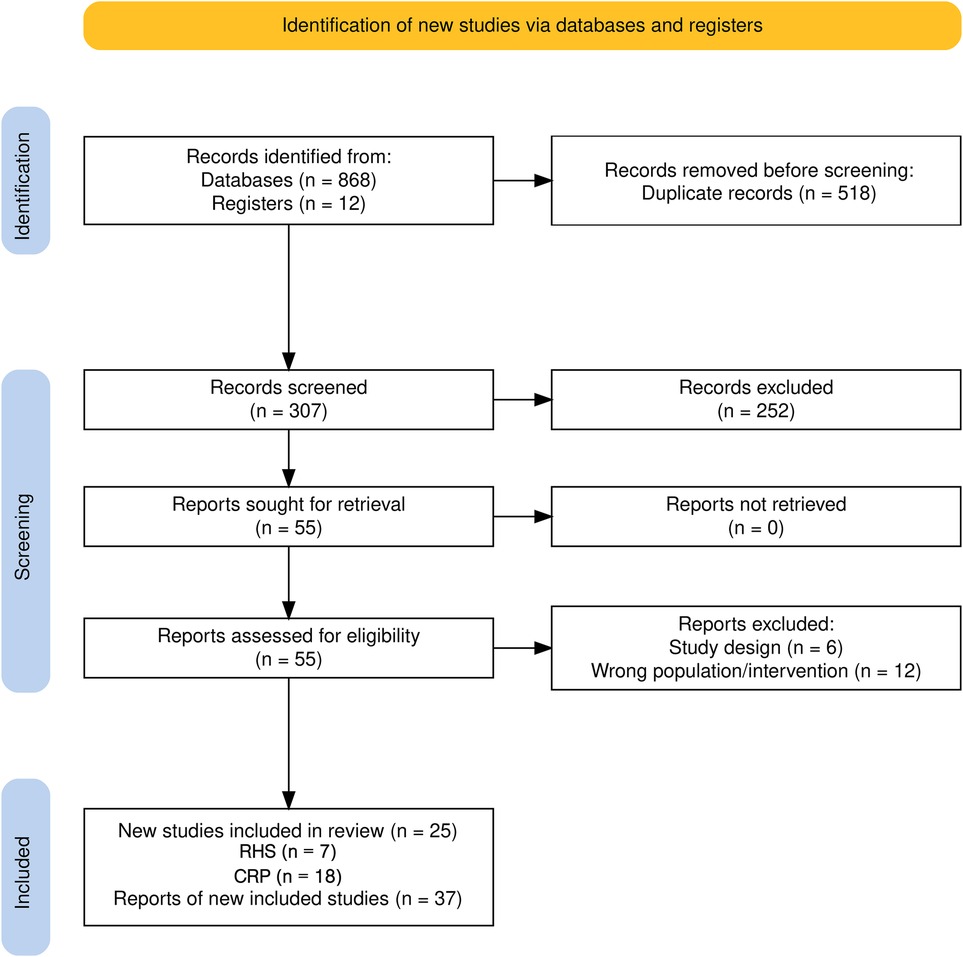

A systematic search of the literature (from inception until 5/9/2023), using the search terms “collegiate recovery”, “recovery school”, “recovery high school”, “recovery hous*”, “university-based recovery center”, or “university based recovery center” in combination with substance use terms (see Supplementary Material), identified 786 records across five publicly available databases (i.e., PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL, CENTRAL, and PsycInfo). A title/abstract screen removed 482 duplicate records and 260 ineligible reports, leaving 44 for full-text review. 11 additional articles were identified through reference list searching of previous reviews and eligible articles and assessed for inclusion. In May of 2024, we completed an updated search, which resulted in 82 records, 36 of which were duplicates. The remaining 46 titles and abstracts were screened and 33 were excluded. The full-text review of 10 articles resulted in 3 more articles being excluded, for a final addition of 7 new articles to the original search. See Figure 1 for the PRISMA flow diagram created using the Shiny app developed by Haddaway and colleagues (28). In the original search, only a single screener completed the screening due to resource constraints, but in the updated search, two screeners independently completed both the title/abstract and full-text screening through the Covidence platform and compared discrepancies. Screeners had 100% agreement for including/excluding studies: the only areas of disagreement were for the reason for excluding a study as only a single item could be selected as a reason for exclusion.

Figure 1. PRISMA study flow diagram (28).

2.3 Data extraction

Data from eligible studies were extracted in duplicate by four members of the review team (EH, JO, MK, SG) using an instrument developed for this purpose in the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) electronic data capture tools hosted at Massachusetts General Hospital (29). The coding form included categories for characteristics at the study level (study design, retention rate, demographic characteristics of participants), group level (intervention and comparator characteristics), and outcome level (type of outcome, measurement of outcome, author-reported statistical results of outcome measure). Coding discrepancies were resolved by discussion. Studies where the first author was an author on this review were coded by alternate review team members.

2.4 Quality assessment

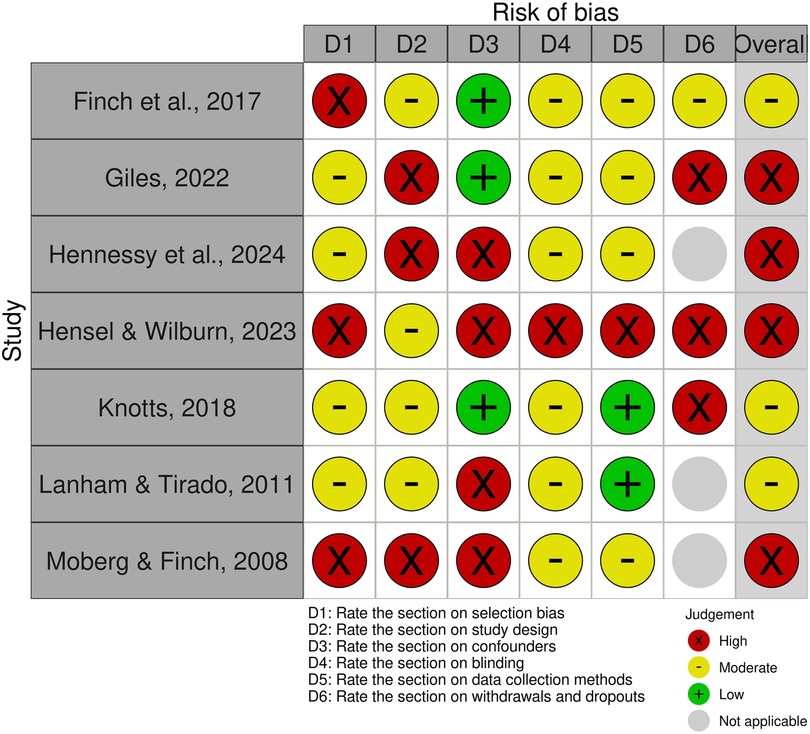

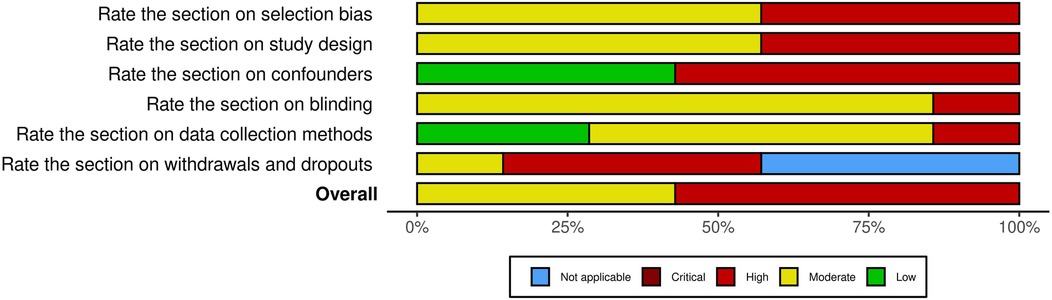

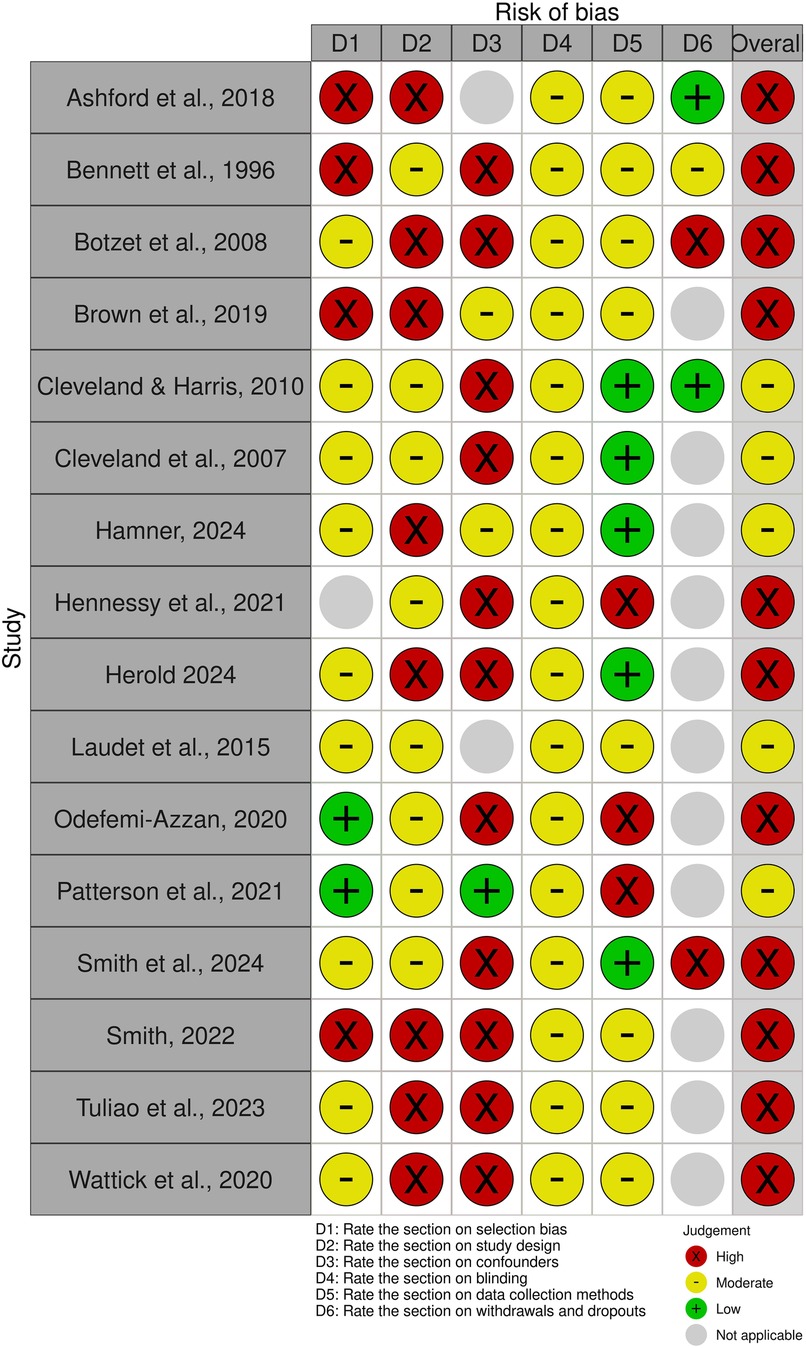

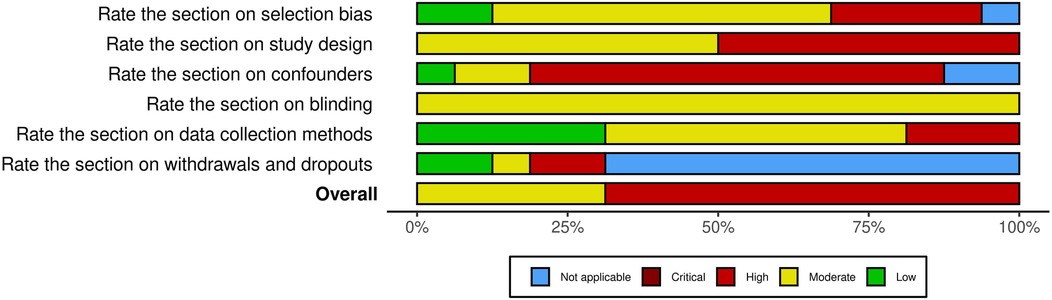

As suggested by previous reviewers to address quality assessment of non-RCTs (30, 31), we used the Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies by the Effective Public Health Practice Project [EPHPP (32)], for all studies aside from the cost-effectiveness/cost-benefit studies (32). Four reviewers (EH, JO, MK, SG) assessed for risk of bias independently and in duplicate and came to a consensus on the component ratings before a global assessment (Strong, Moderate, Weak) was decided. The Risk-of-bias VISualization (ROBVIS) online tool was used to visualize and present the quality assessment results from the EPHPP tool (33).

For the two cost-effectiveness/cost-benefit studies included in the CRP review, a single reviewer (EH) used a separate tool appropriate for these designs to rate their quality (34), which has 16 items and uses a weighted grading scheme, resulting in a score for each study of up to 100. In this tool, the question about sub-group analysis (weight of 1) was deemed not applicable for either study so the resulting scale range is up to 99.

2.5 Synthesis

We used Synthesis Without Meta-analysis (SWiM) to guide our reporting of the outcomes (35). Given the likely diversity of the included studies and the small evidence base, the review team decided a priori that a descriptive synthesis would be undertaken, highlighting areas for future primary studies and meta-analyses to examine. All extracted data were tabularized and summarized in tables to aid in the descriptive synthesis of findings. We grouped the outcomes into the following seven broad categories of outcomes we established a priori and reported all identified outcomes in these categories in the text and/or tables: (1) Academic; (2) Crime/Criminal Involvement; (3) Employment; (4) Recovery Capital (validated measures); (5) Social network change; (6) Substance use; (7) Other psychosocial outcome. After coding the included studies, we returned to the “Other psychosocial outcome” grouping for each intervention (RHS and CRP) and created a further sub-coding of categories based on emerging categories. Drug craving/urges and length of time in recovery were both recategorized from “other psychosocial outcome” to the (6) Substance use category for ease of interpretation. We added new categories of (8) Mental or Physical Health (9), Life Satisfaction/Flourishing (10), Cost benefit, and (11) Metrics of Participation (CRPs only) to replace the broader “other” outcomes category. We considered metrics of participation important to gather as these can be considered an intermediate or enabling outcome. By attending programming, participants are positioned to gain the resources and social support necessary to achieve longer-term outcomes. Although the ultimate goals of CRPs include long-term impacts like remission and graduation, participation metrics recognize that the process of engaging the community is itself an important achievement. This aligns with theories of change that value process-oriented outcomes alongside impact-oriented ones (36).

Given the diversity of types of outcomes and ways these were measured, we did not standardize the coded quantitative outcomes into any given metric but instead reported these outcomes as they had been reported in the primary studies using the text and/or table entries provided by the authors.

3 Results

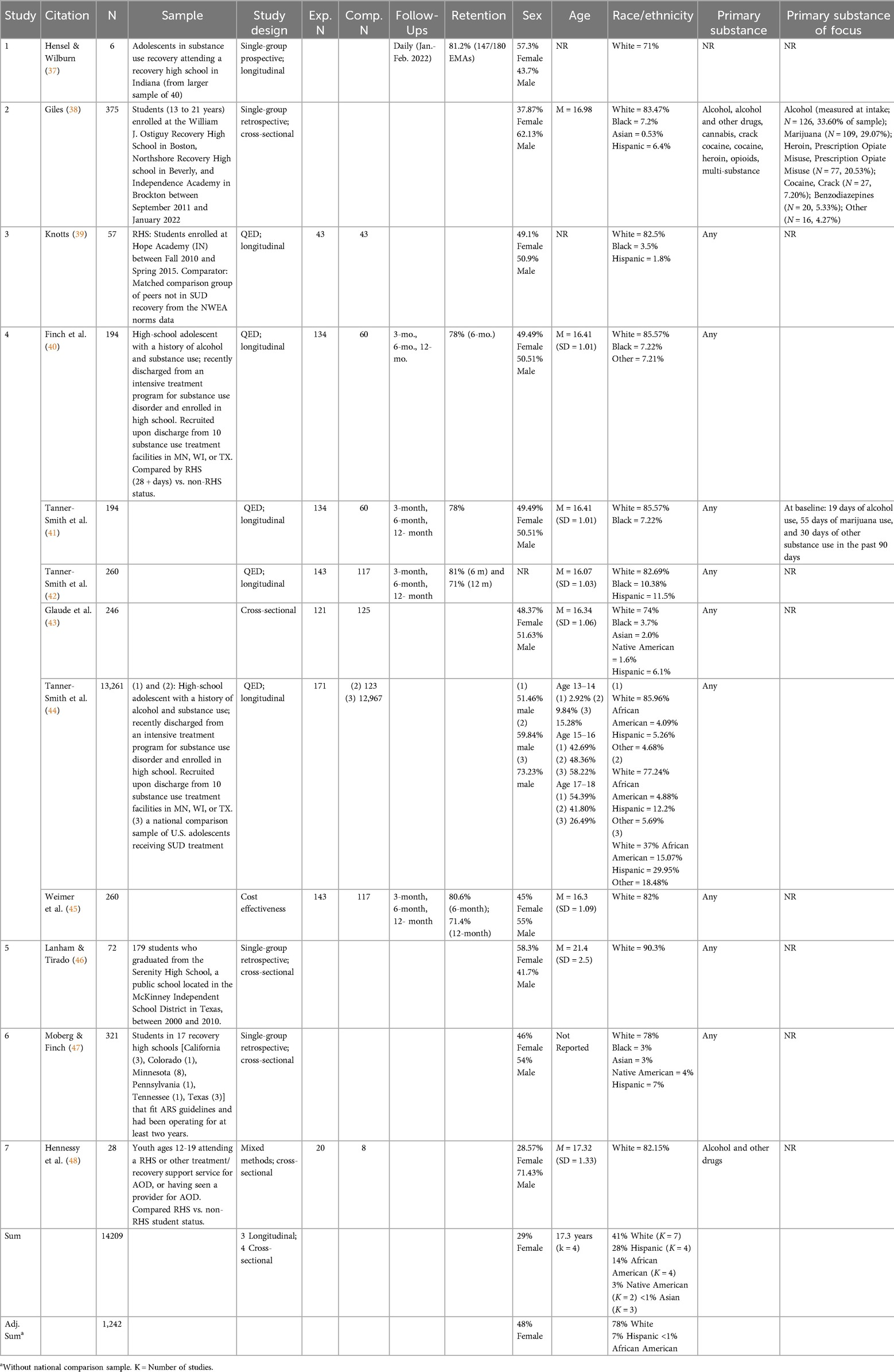

We identified 37 manuscripts representing 25 unique studies that focus on RHS (K = 7: N = 14,209 including a national sample from a pooled dataset of adolescents who have undergone SUD treatment, or N = 1,242 without that sample included) or CRPs (K = 18: N = 2,795). An overall summary of key characteristics of these studies is in Table 1 (RHS) and Table 2 (CRP). Notably, there were no RCTs of either type of educational recovery support, so the strongest study designs identified are comparative studies that attempt to equate groups through matching or cost-benefit analysis studies.

3.1 Description of recovery high school studies

3.1.1 Types of research designs

Of the seven RHS studies, there were two comparative studies: (1) a dissertation by Adam Knotts in 2017 (39) and (2) another study from Finch and colleagues in 2017 [Finch and colleagues (40)] was the main publication with a series of additional manuscripts focused on different subsets of the population or research questions, including a publication led by Weimer utilizing cost-benefit analysis (41–45).1 There was also one cross-sectional mixed methods study that explored differences between RHS and non-RHS groups (48), three cross-sectional single-group studies of just RHS students (38, 46, 47), and one longitudinal single-group study of RHS students (37).

3.1.2 Study characteristics

Study samples ranged in size from just six persons up to 13,261. Tanner-Smith and colleagues published multiple studies comparing their sample of RHS attendees with a previously-collected national comparison sample of US adolescents receiving treatment for AOD use treatment, but who attended mainstream high school (44). This inclusion inflated the sample demographics across several categories to be more nationally representative. Including this sample, participants were predominantly White (41%), with Hispanic (28%), Black (14%), and Native American (3%) participants represented at rates generally consistent with the national United States demographics. Females represented only 29% of the overall participant sample. Without this national sample, participants were predominately White (78%; range, 71%–90%), with only 7% Hispanic and <1% Black participants included. Studies also had about equal female and male participants overall (M = 48% female; M range, 29%–57%). The average age was 17.3 years (M range, 13–21).

3.1.3 Study quality

Overall, there were three studies of moderate and four of high risk of bias; no studies met the criteria for low risk of bias (See Figures 2, 3). Blinding of participants to the research question and of data collection by the outcome assessor were most likely to have the lowest risk of bias ratings, at primarily moderate. Regarding the potential for selection bias, individuals who were selected to participate were rated as either somewhat or very likely to be representative of the target population, but only a single study reported the percentage of individuals who agreed to participate after selection (46). In terms of appropriately addressing the potential confounders defined by the EPHPP tool, the studies were split between low risk of bias (k = 3) or high risk of bias (k = 4). Those rated as high risk of bias did not measure potential confounders, or if they did, did not include them in their analytic approach to examining outcomes. For example, of the list of eight common confounders (race, sex/gender, marital status/family, age, income/class, education, health status, and pre-intervention score on outcome), only 3 studies controlled for race and/or sex/gender, only 2 studies controlled for age and pre-baseline scores on outcomes (e.g., AOD use), and only a single study controlled for SES, education, or health status of participants.

3.2 Recovery high school student outcomes

3.2.1 Overview

Six of the seven studies examined some aspect of substance use (e.g., frequency, abstinence), with all but one (38) using primarily self-report. Four studies examined academic outcomes, with only two using official school records (38, 39). Two studies examined involvement with the criminal justice system via self-reported delinquency (42) or legal issues (46). Two studies examined social networks, with one focusing on conflict and perceptions of social support (43) and the other focusing on the alcohol and drug use behaviors of social groups within their networks (48). Two studies examined mental (but not physical) health outcomes, and a single study examined life satisfaction/flourishing. A single study examined work status (full vs. part-time) and number of hours worked. No studies examined measures of Recovery Capital.

3.2.2 Comparative studies

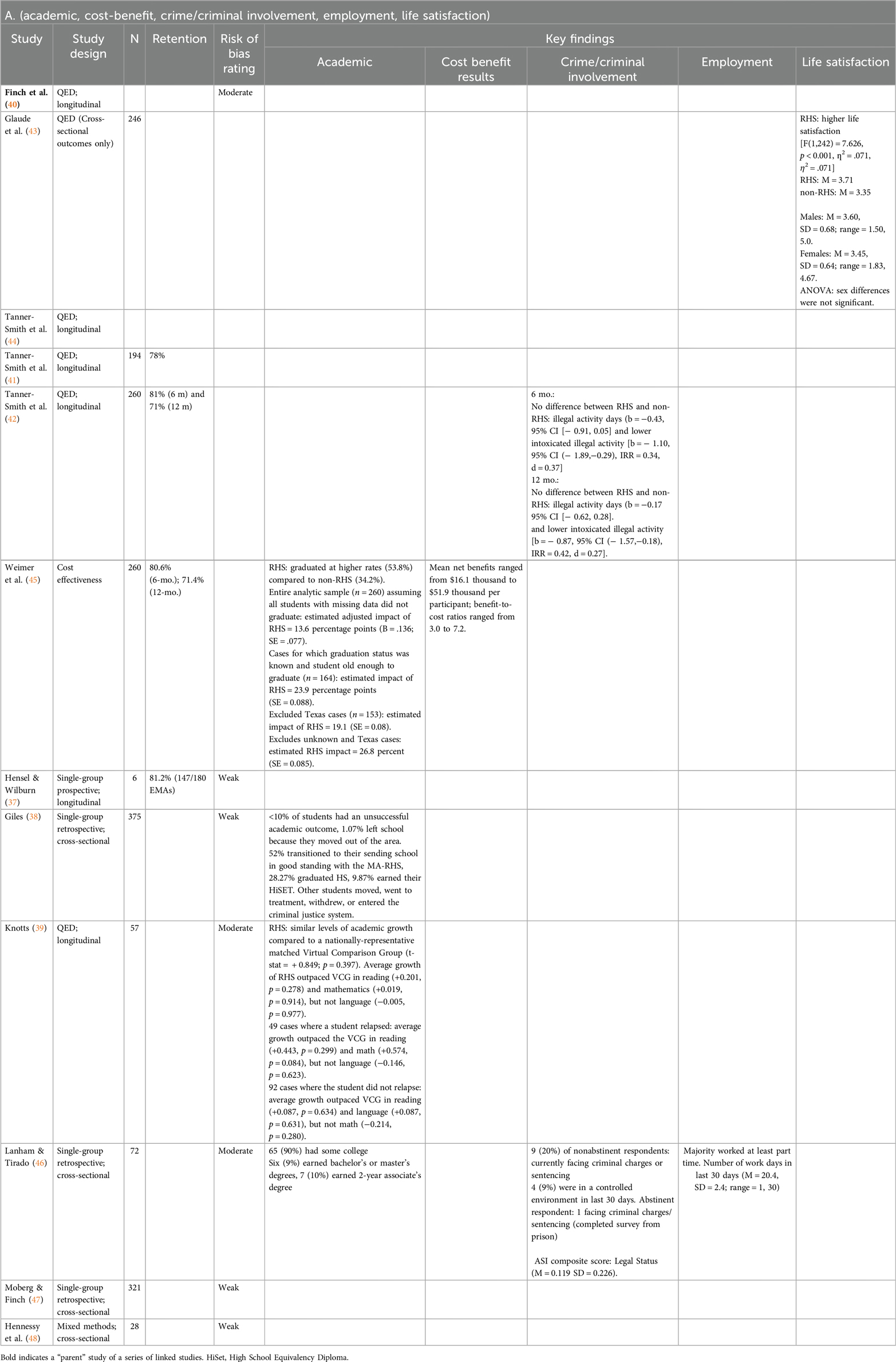

This section details the adolescent outcomes among the studies of RHSs with the most rigorous study design in this sample, two comparative studies of RHS, one of which includes a cost-benefit analysis driven from the findings of the researchers' quasi-experimental study. In addition to having the most rigorous study design, they had the lowest risk of bias (moderate) compared to the majority of other studies. The other study designs and their associated outcomes are reported in full in Table 3.

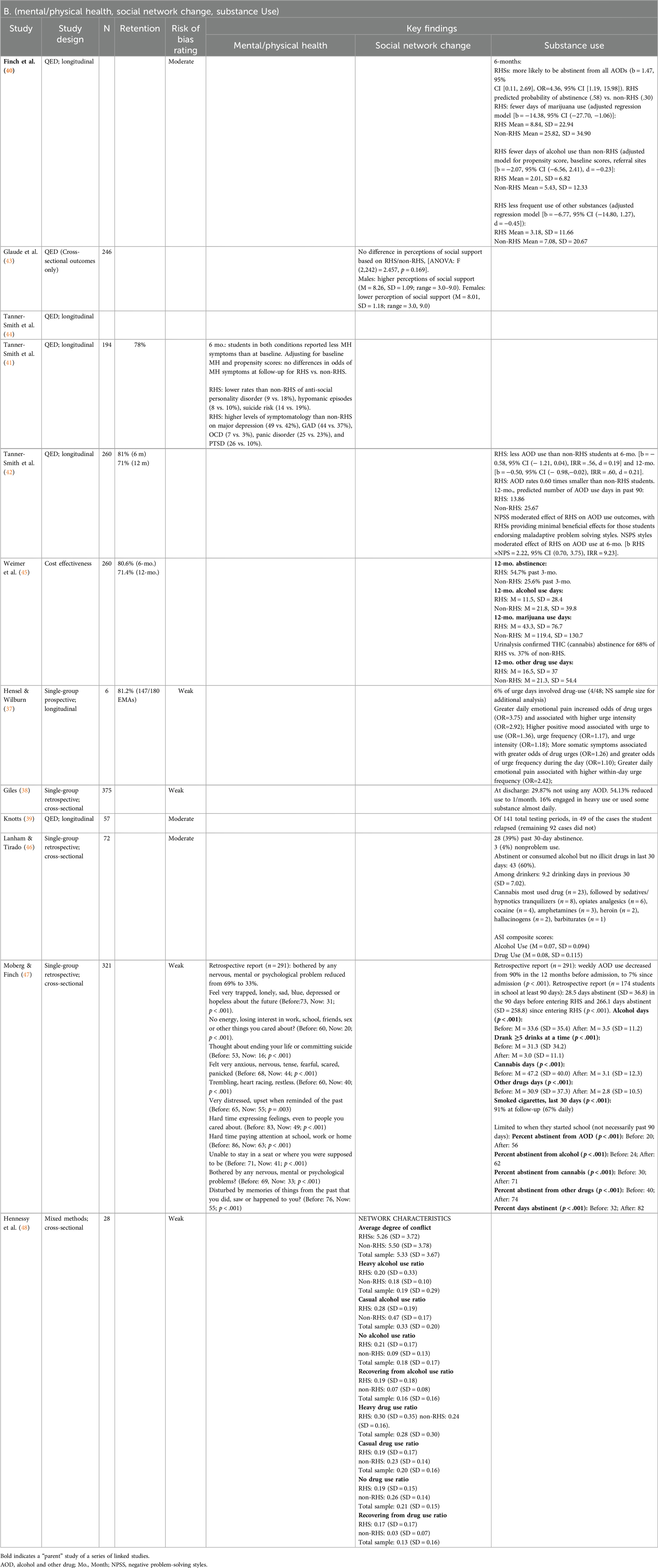

Table 3. Recovery high school study outcomes by study quality: academic, cost-benefit, crime/criminal Involvement, Employment, life satisfaction, mental/physical health, social network change, substance Use (K = 7).

One dissertation study conducted by Knotts (39) enrolled 57 students from an Illinois RHS, Hope Academy (2010–2017) and matched 43 of these students with a nationally representative virtual comparison group of students from the 2015 Northwest Evaluation Association's Measure of Academic Progress normative data. Matching was conducted to ensure that students were from similar schools (percentage of students receiving free/reduced-price lunches and school location) and that there was a match for each RHS student on gender, ethnicity, subject area, starting score, grade level, and testing timeframe. When examining these academic outcomes using paired t-tests, RHS students displayed similar levels of academic growth when compared to the virtual comparison group (t-stat = + 0.849; p = 0.397), including on reading (+0.201, p = 0.278), mathematics (+0.019, p = 0.914), and language (−0.005, p = 0.977). Substance use was only assessed among RHS students as the virtual comparison group did not have this assessment. The RHS students were administered the Global Assessment of Individual Needs-Short Screen (GAIN-SS) every eight to twelve weeks. This resulted in 141 instances of the GAIN-SS in the RHS sample: in 49 of these, the student had returned to use, while in the remaining 92 instances, they had not returned to substance use.

In the only other comparative study of RHS students, 294 youth in recovery were recruited from RHS and treatment centers from 2011 to 2016 (40–45). Their school enrollment choice (after treatment, if enrolled from a treatment center) was collected, and they were followed for one year. Matching was conducted to equate the non-RHS and the RHS youth for the analysis. Of the analyzed sample of 260 youth, RHS students reported less substance use than non-RHS students at the 6-month (b = − 0.58, 95% CI [− 1.21, 0.04], Incidence Rate Ratio [IRR] = .56, d = 0.19) and 12-month follow-ups [b = −0.50, 95% CI (− 0.98,−0.02), IRR = .60, d = 0.21]. Students who attended RHS reported substance use rates approximately 0.60 times lower than non-RHS students. At the 12-month follow-up, the number of days predicted by the negative binomial models for use of substances in the past 90 days was 13.86 for RHS students vs. 25.67 for non-RHS students. RHS students reported less frequent delinquent behavior while intoxicated and fewer days of substance use relative to students attending non-RHSs. Urinalysis was used to examine abstinence from THC (cannabis): 68% of RHS students vs. 37% of comparison students were abstinent. In the cost-benefit analysis from 260 students in this sample (45), the mean net benefits ranged from $16.1 thousand to $51.9 thousand per participant, indicating a large cost savings by implementing the RHS for youth struggling with substance use; benefit-to-cost ratios ranged from 3.0 to 7.2. In addition, RHS students' high school graduation rates were 21–25 percentage points higher than comparison students.

3.3 Description of collegiate recovery program studies

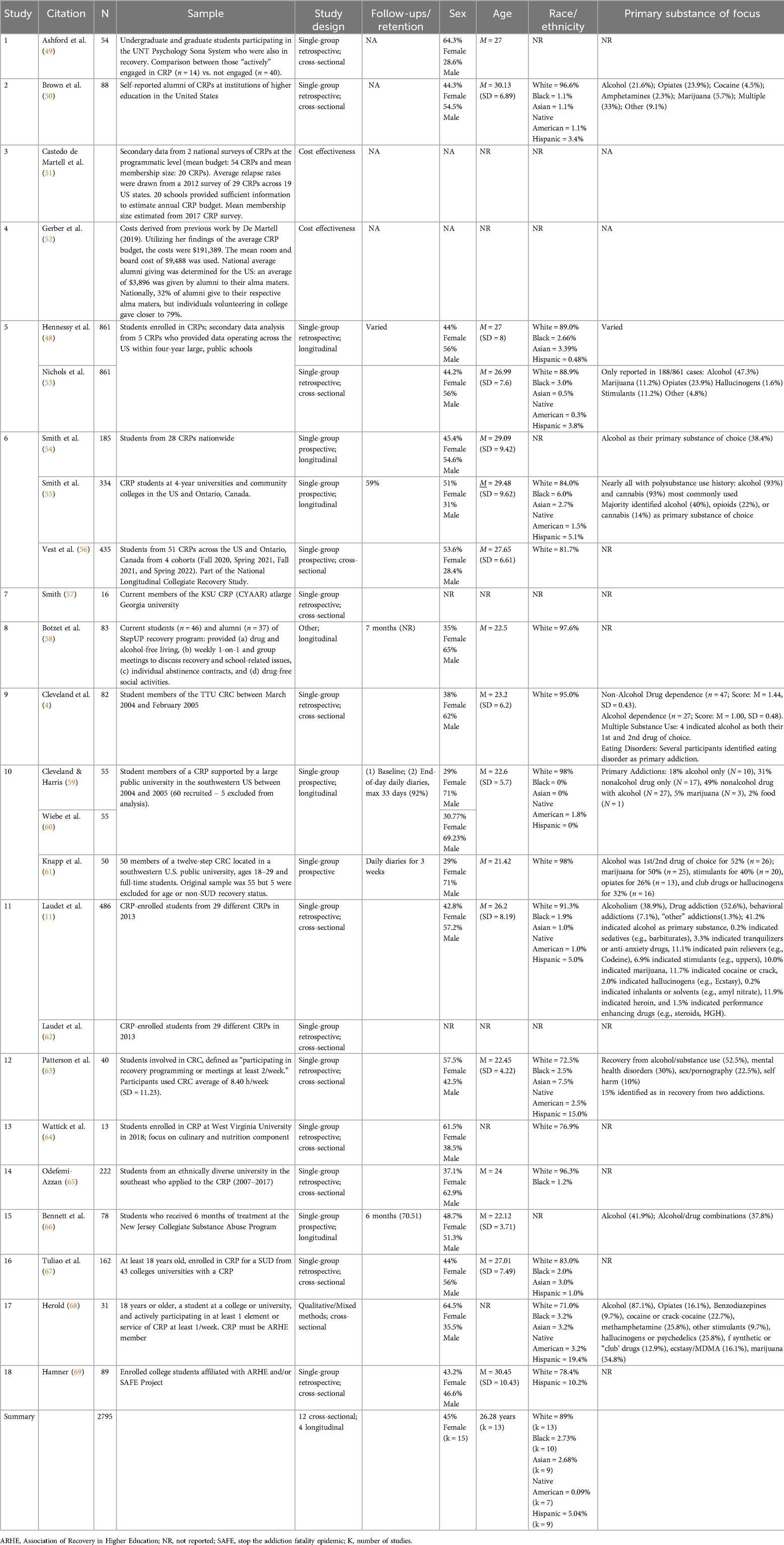

Of the 18 CRP studies, there were two cost-benefit (51, 52) and 16 single-group studies, the majority of which were cross-sectional (75%).

3.3.1 Study characteristics

The demographic characteristics for the 17 studies that were not cost-benefit studies indicate a high degree of heterogeneity across the included studies. Study samples ranged in size from 13 to 861 participants, although the largest sample size was from a secondary data analysis that synthesized data across five CRPs (13). Participants were predominately white (89%; range, 71%–98%). Studies had slightly less female than male participants overall (M = 45% female; M range, 29%–66%). The average age was 26.28 years (M range, 22–30).

3.3.2 Study quality

Overall, the 16 studies that did not use cost-benefit analysis had variable quality (See Figures 4, 5). The majority were rated as high risk of bias (k = 11), primarily due to selection bias, study design, and the way confounders were addressed. All studies were rated as moderate due to their approach to blinding of participants to the research question and of the outcome assessors to the condition of the participants. A subset of five studies were rated as low risk of bias in data collection methods, with a further eight studies at moderate risk of bias as many used validated and reliable scales or a combination of these with measures developed for their study purposes.

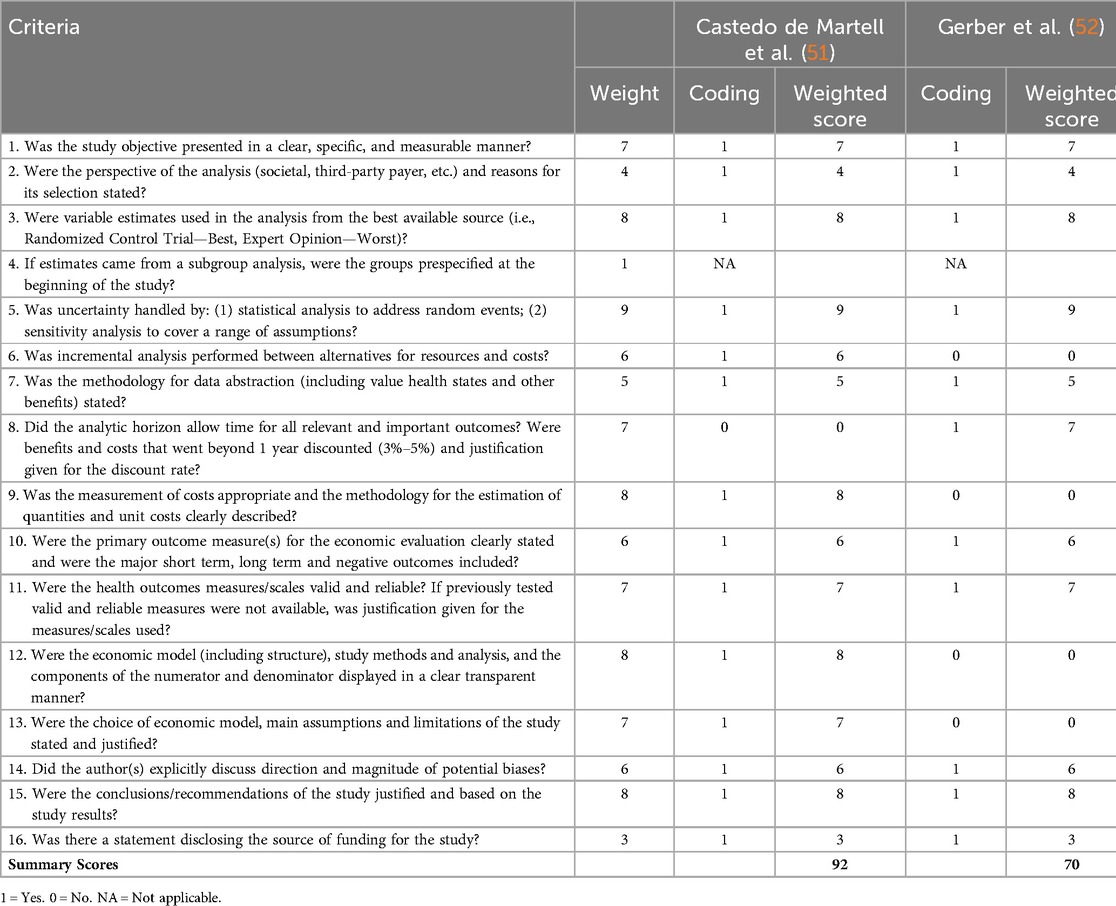

The quality rating of the two studies using cost-benefit designs indicated that overall both studies had fairly rigorous approaches (See Table 4). The study by Castedo de Martell and colleagues (51) achieved a score of 92. Factors influencing this score were a lack of adjusting for longitudinal outcomes and not discounting benefits over time. The study by Gerber and colleagues (52) achieved a score of 70, primarily due to poor reporting of various aspects of the approach, including a lack of specifying and justifying the modeling approach, using insufficiently or overly optimistic assumptions (e.g., rates of volunteerism) and relying heavily on the earlier cost work by Castedo de Martell (51) without sufficient rationale for several indicators.

Table 4. Results of the grading assessment of the quality of the CRP cost-effectiveness studies (K = 2).

3.4 Collegiate recovery program student outcomes

3.4.1 Overview

Nine studies examined substance use outcomes and all used self-report assessments. Five additional studies did not examine substance use directly but instead inquired about length of time in recovery or substance craving (15, 49, 59, 64, 69). Seven studies examined academic outcomes, with the majority focused on GPA (4, 13, 15, 49, 55, 57, 62, 65). Five studies assessed various metrics related to CRP participation, including duration of participation, perceived helpfulness or program benefits, engagement in recovery-related activities, and whether the CRP was the primary pathway to recovery (50, 54, 55, 58, 62, 67). Five studies examined mental and/or physical health outcomes, with the majority assessing the history of such problems not limited to the resolution of problems during the participant's time in the CRP (11, 53, 58–60, 66). Two studies examined stress among participants related to their current experience in the CRP (54, 58), and another study examined “good health and the absence of depression symptoms” as part of their CRP culinary programming component (64). Four studies (49, 50, 54–56, 65, 69) examined recovery capital using either the 50-item Assessment of Recovery Capital (72) or its 10-item version, the BARC (73). Five studies (49, 50, 54–56, 64, 68) examined life satisfaction by measuring self-reported quality of life (k = 3), personal growth (k = 1), resilience (k = 1), and/or flourishing (k = 1). Four studies examined aspects of social networks: (i) social network change (58), (ii) whether the CRP plays an important role in their social life (55), and (iii) in-group nominations (63). Two additional reports from the same study examined whether and where (CRC setting or not) a participant talked with others about their recovery and how this related to their craving (59), as well as whether stress and negative affect changed who CRC students connected with (family, sponsor, CRC peers) and how frequently (61). Two studies examined employment by collecting whether participants worked during the semester and examining hours worked (4, 56). A single study focused on criminal involvement and examined self-reported “legal severity” (66) and another study analyzed several recovery outcomes by comparing them across student incarceration history (56).

3.4.2 Cost-benefit studies

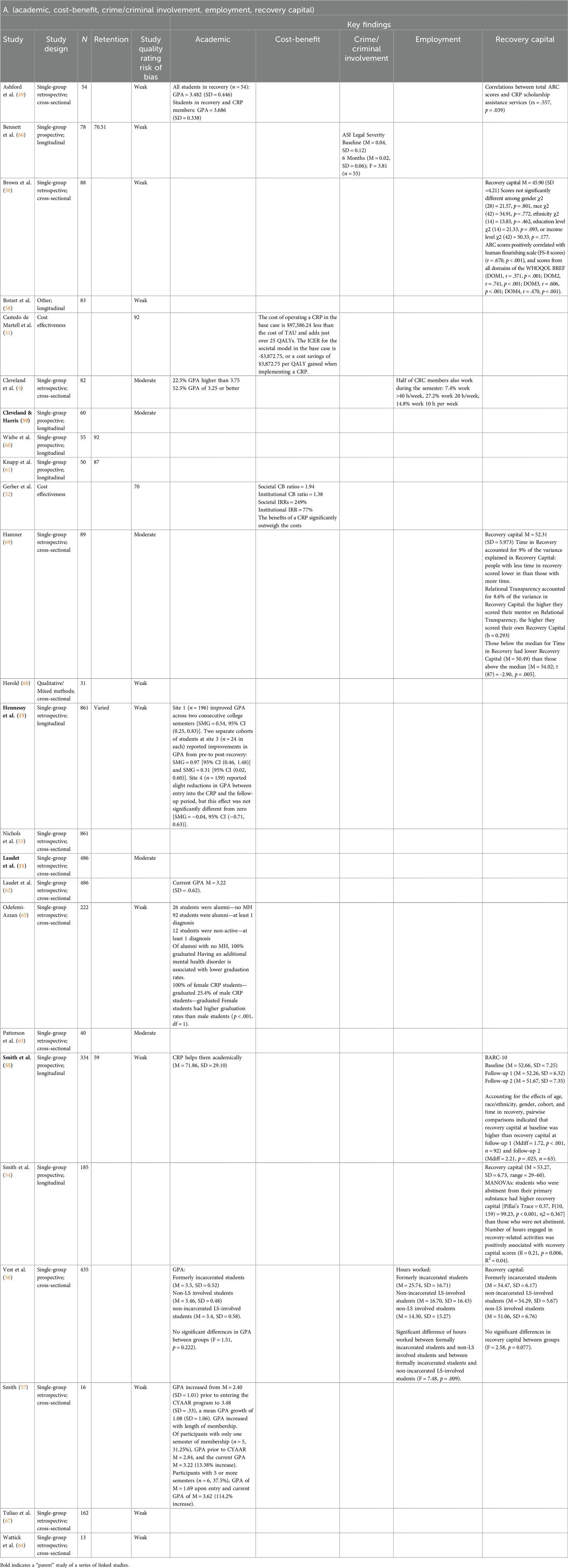

This section focuses on the student outcomes among the two studies of CRPs that utilized cost-benefit analyses (51, 52). The other 16 studies, study designs, and their associated outcomes are reported in Table 5.

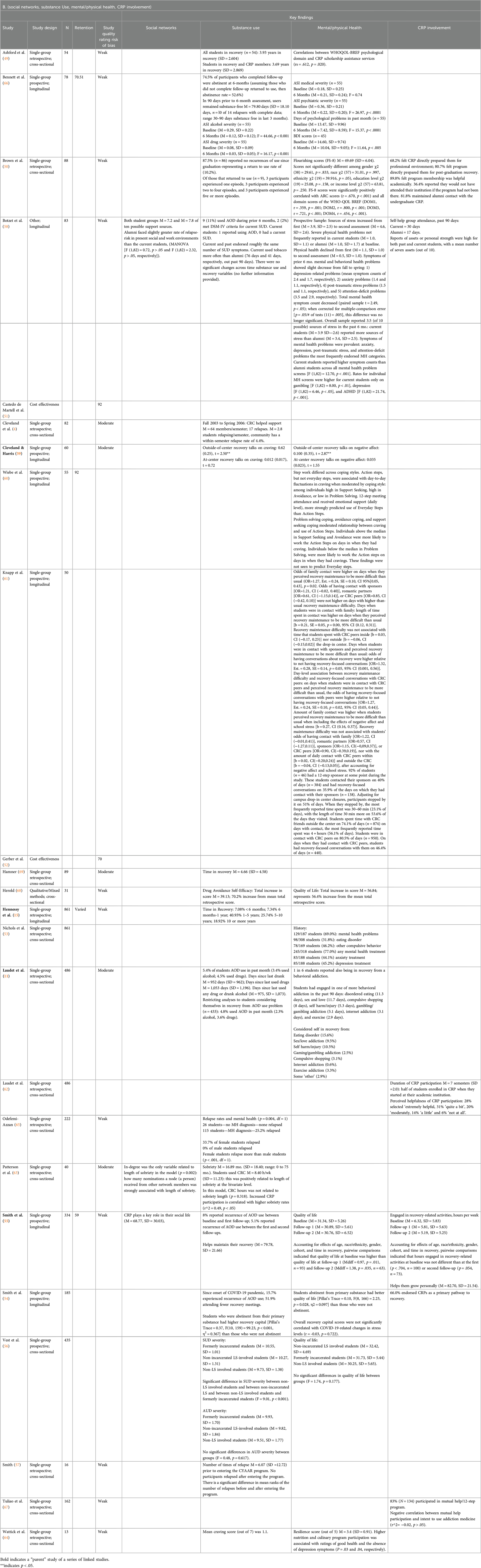

Table 5. Study outcomes by study quality: collegiate recovery program engagement and satisfaction, substance use, recovery capital, social connectedness, employment/education, criminal justice involvement, quality of life and well-being (K = 19).

In one cost-benefit analysis of CRPs (51, 74), the authors used secondary data from two national surveys of CRPs at the programmatic level to model CRP-related variables. The mean budget was modeled from 54 CRPs and the mean membership size from 20 CRPs, while the average relapse rates were used from a 2012 survey of 29 CRPs across 19 US states. Model results indicated that the cost of operating a CRP in the base case is $97,586.24 less than the cost of treatment as usual and adds just over 25 Quality-Adjusted Life Years. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio for the societal model in the base case is -$3,872.75, suggesting a cost savings of $3,872.75 per Quality-Adjusted Life Years gained when implementing a CRP.

In another cost-benefit analysis of CRPs (52), several sources of existing data were used. Utilizing Castedo De Martell's 2019 findings of the average CRP budget [from the thesis underlying the 2022 publication covered above (74)], the CRP costs for this study were set at $191,389. The mean room and board cost to educate students of $9,488 was used as a cost to the university. The national average alumni giving amounts in the United States was determined using alumni giving amounts and volunteering to the college. An underlying assumption was that CRP students might be more willing to give due to the strong tradition of giving back as part of CRP membership while students at the university. A CRP size of 14 members was used in the calculations and a 90% graduation rate was used. These calculations resulted in a societal cost-benefit ratio of 1.94 and an institutional cost-benefit ratio of 1.38. The societal Incident Rate Ratio was 249% and the institutional Incident Rate Ratio was 77%. The results indicate that for every dollar the university spends, there will be a return of $2.26 over the course of ten years. Thus, this study indicated that the benefits of a CRP outweighed the costs, but to what degree a CRP outweighs the costs will depend on the size of the university and the expected CRP student membership.

4 Discussion

This systematic review identified 25 unique studies focused on education-based supports for adolescents (RHSs) and emerging adults (CRPs). The combination of a good number of descriptive studies, and a few studies with comparison groups, suggests that students who participate in RHS and CRPs may demonstrate positive outcomes such as reductions in AOD use, and improvements in social and academic outcomes (e.g., grades). Yet, given the lack of randomized controlled designs or even non-randomized comparative prospective research designs, statements about the incremental public health utility of investing in RHSs and/or CRPs relative to some other kind of approach of equal intensity and duration or engagement with services-as-usual, cannot be made with confidence. Similarly, cost-benefit analyses among both types of programs suggest large cost-savings or benefits, which could benefit society overall, but given the lack of comparative prospective investigations, robust estimates of cost-benefit remain unclear. Unlike an RHS, which often requires standalone programming, CRPs represent programming that can be implemented on college and university campuses and potentially integrated with college student health and wellness services. Thus, there seems to be increased potential for their sustainability in these settings given the larger cost savings and potential for synergy with existing structures that these programs represent. Overall, findings suggest possible near-term benefits are likely from RHS and CRP participation. However, much greater research investment is needed to understand more clearly the incremental benefit attributable to these kinds of programs as well for which students in particular, and also to gain greater clarity on the long-term trajectories of youth with SUD histories engaged with such services vs. similar youth who are not engaged with such services.

As might be expected of studies examining recovery supports in education settings, the most commonly measured outcomes for both types of supports were some assessment of substance use and academic outcomes. Surprisingly, given that a key proposed mechanism of both programs is engaging young people in positive social supports and creating recovery-supportive social networks, only a minority of studies examined whether this happened for their participants (5, 13). Capturing social networks can be challenging with limited resources, but it would be an important mechanism for these programs to examine in future research. A few studies also examined mental health outcomes, which epidemiological data has identified as important to understand among individuals experiencing AOD use disorders (75, 76). Only the CRP studies directly examined recovery capital, using a recovery capital measure. This may be due in part to the lack of a developmentally-appropriate measure of recovery capital despite the identified gap in recovery capital measures (23, 77).

At present, given the study designs of the existing research identified in this review, there is limited evidence identifying RHSs and CRPs as the direct cause of improved outcomes for their participants. There is also limited evidence of longer-term outcomes related to positive development and the growth of recovery capital, such as college graduation, employment and career trajectory after college, and marriage or family life. Furthermore, results from the reviewed studies must be considered alongside their methodological limitations which included high potential for selection bias (often inadequately addressed in analysis), study design (majority of studies did not utilize a comparator group), and the lack of appropriate attention to confounders. There are many important gaps in the literature base that will be important to fill. For example, as it is less feasible to conduct RCT designs with these types of recovery supports, it will be important for researchers to conduct rigorous and longitudinal quasi-experimental studies to determine the effect of RHS and CRPs on AOD use and related outcomes, from which point researchers can work to determine which aspects of these programs are most beneficial, for whom in particular, and why. Providing RHS and CRP programs with funds for a data collection infrastructure that includes dedicated personnel and technical support to engage in ongoing program monitoring will help to establish a sustainable evidence base for these services (12, 13). Overall, substantially more research is needed to begin forming conclusions about the utility of these education-based recovery supports.

In addition to efficacy, RHS and CRPs face additional challenges that warrant investigation. One key issue evident from the studies in this review is that students who utilize these supports are predominately white. Although researchers identify racial disparities in addiction treatment as an ongoing issue (9), RHS often do not reflect the demographic breakdown of their school district (46) or their county. In fact, there are more students of color who receive addiction treatment per capita than attend RHS (78). One possible avenue for future research is to examine, among other factors, the ways in which students are referred and considered for program admission to identify barriers that minoritized individuals face in accessing these services, reason for engaging in services when they do, and strategies for surmounting them. Moreover, it is important for researchers to investigate why, despite the millions of adolescents and young adults with substance use disorder who need treatment, many RHS report one of their main challenges to be enrolling enough students (10). When considering that in 2021, there were an estimated 1.9 million adolescents and 8 million young adults in need of specialized substance use disorder treatment who did not receive it (79), it is important for researchers to work to reconcile the paradox of the adolescent and young adult treatment gap with the enrollment struggles of RHS.

Despite a strong theoretical rationale for the need for education-based recovery supports for young people, research on their effectiveness remains nascent, with only a handful of studies examining these potentially integral supports. Well-conducted comparison studies that examine their underlying logic model are needed to confidently assert that such programs are worthy of integration into the broader public education system (13, 14). Then, larger-scale studies might be undertaken that examine the specific mechanisms to determine how these resources confer benefit and for which students, in particular.

4.1 Limitations

Several limitations to the methodological approaches employed in this review should be mentioned. First, screening from the original search was not conducted in duplicate; however, the updated search included duplicate screening, and there were no exclusion discrepancies during this screening, so the risk of inadvertently excluding eligible studies is minimal. Second, while we identified some grey literature (e.g., conference abstracts and dissertations), our search primarily used electronic databases. Thus, some relevant studies may be missing from this review. Finally, although the majority of studies' risk of bias were assessed in duplicate using two reviewers, only a single reviewer applied the separate cost-benefit tool to assess the risk of bias in the two cost-benefit studies. In the interest of transparency, we provide all coded responses for this tool in Table 4.

5 Conclusions

This systematic review highlights the growing interest and evidence supporting education-based recovery supports (RHSs) and collegiate recovery programs (CRPs) for adolescents and young adults, suggesting potential reductions in substance use and improvements in academic and social outcomes. Despite these promising findings, robust causal evidence is limited, particularly regarding effects on long-term outcomes and the development of recovery capital, indicating a need for more rigorous comparative studies with much longer follow-up and better measurement and data collection. Additionally, disparities in enrollment highlight a critical gap in access for students of minoritized identities, emphasizing the importance of investigating barriers to participation and ensuring these programs reflect the demographics of their communities (70, 71).

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

EH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Resources, Validation. SG: Formal Analysis, Visualization, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Investigation, Validation. MK: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Validation, Writing – review & editing. JO: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Validation, Writing – review & editing. DE: Writing – review & editing. JK: Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Support for this work was provided in part by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and Opioid Response Network (1H79TI085588) and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (K01AA028536 [Hennessy], K23AA027577 [Eddie], K24AA022136-10 [Kelly]).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fradm.2025.1522678/full#supplementary-material

Footnote

1. ^Other publications that were identified and linked to this study because they published on a portion of the data or focused on aspects of the study design but were not coded for this review include: (70, 71).

References

1. Behavioral Health, Statistics and Quality. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS): 2020. Admissions to and Discharges from Publicly Funded Substance Use Treatment Facilities. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2022). Available online at: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/data-we-collect/teds-treatment-episode-data-set

2. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). 2018–2019 National Surveys on Drug Use and Health: Model-Based Estimated Totals (in Thousands) (50 States and the District of Columbia). Available online at: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt32879/NSDUHsaeTotal2019/2019NSDUHsaeTotal.pdf (Accessed September 10, 2024).

3. National Center for Education Statistics. Marijuana Use and Illegal Drug Availability [Internet]. 2021 May. (Preprimary, Elementary, and Secondary Education). Available online at: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/a15/marijuana-use-drug-availability (Accessed September 10, 2024).

4. Cleveland HH, Harris KS, Baker AK, Herbert R, Dean LR. Characteristics of a collegiate recovery community: maintaining recovery in an abstinence-hostile environment. J Subst Abuse Treat. (2007) 33(1):13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.11.005

5. Finch AJ, Frieden G. The ecological and developmental role of recovery high schools. Peabody J Educ. (2014) 89(2):271–87. doi: 10.1080/0161956X.2014.897106

6. Hennessy EA, Tanner-Smith EE, Finch AJ, Sathe N, Kugley S. Recovery schools for improving behavioral and academic outcomes among students in recovery from substance use disorders. Campbell Collab. (2018) 14:1–86. doi: 10.4073/csr.2018.9

7. White WL, Finch AJ. The recovery school movement: its history and future. Counselor. (2006) 7(2):54–8.

8. Office of National Drug Control Policy. National Drug Control Strategy 2014. Washington, DC: Office of National Drug Control Policy (2014). Available online at: https://www.ojp.gov/ncjrs/virtual-library/abstracts/national-drug-control-strategy-2014 (cited October 21, 2024).

9. Association of Recovery Schools. The State of Recovery High Schools, 2016 Biennial Report. Denton, TX; 2017. Available online at: https://recoveryschools.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/State-of-Recovery-Schools_3-3-16.pdf (cited 2024 October 21).

10. Finch AJ, Moberg DP, Krupp AL. Continuing care in high schools: a descriptive study of recovery high school programs. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse. (2014) 23(2):116–29. doi: 10.1080/1067828X.2012.751269

11. Laudet AB, Harris K, Kimball T, Winters KC, Moberg DP. Characteristics of students participating in collegiate recovery programs: a national survey. J Subst Abuse Treat. (2015) 51:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2014.11.004

12. Vest N, de Martell SC, Hennessy E. Introducing a socio-ecological model of collegiate recovery programs. Drug Alcohol Depend. (2024) 260:110563. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2023.110563

13. Hennessy EA, Nichols LM, Brown TB, Tanner-Smith EE. Advancing the science of evaluating collegiate recovery program processes and outcomes: a recovery capital perspective. Eval Program Plann. (2022) 91:102057. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2022.102057

14. Vest N, Reinstra M, Timko C, Kelly J, Humphreys K. College programming for students in addiction recovery: a PRISMA-guided scoping review. Addict Behav. (2021) 121:106992–106992. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.106992

15. Hennessy EA, Tanner-Smith E, Nichols LM, Brown TB, Mcculloch BJ. A multi-site study of emerging adults in collegiate recovery programs at public institutions. Soc Sci Med. (2021) 278:113955–113955. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113955

16. Granfield R, Cloud W. Coming Clean: Overcoming Addiction Without Treatment. Vol. 25. New York: New York University Press (1999). p. 281.

17. Granfield R, Cloud W. Social context and “natural recovery”: the role of social capital in the resolution of drug-associated problems. Subst Use Misuse. (2001) 36(11):1543–70. doi: 10.1081/JA-100106963

18. Hennessy EA, Cristello JV, Kelly JF. RCAM: a proposed model of recovery capital for adolescents. Addict Res Theory. (2019) 27(5):429–36. doi: 10.1080/16066359.2018.1540694

20. Maslow AH. Preface to motivation theory. Psychosom Med. (1943) 5(1):85–92. doi: 10.1097/00006842-194301000-00012

21. Finch AJ. Recovery High Schools Growth Chart - Assn. of Recovery Schools [Internet]. Association of Recovery Schools. (2021). Available online at: https://recoveryschools.org/rhs-growth-chart/ (cited October 21, 2024).

22. Association of Recovery in Higher Education. Collegiate Recovery Directory [Internet]. Kennesaw, Georgia: Association of Recovery in Higher Education. (2024). Available online at: https://collegiaterecovery.org/collegiate-recovery-directory/ (cited October 21, 2024).

23. Hennessy EA. Recovery capital: a systematic review of the literature. Addict Res Theory. (2017) 25(5):349–60. doi: 10.1080/16066359.2017.1297990

24. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Br Med J. (2021) 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

25. The Methods Group of the Campbell Collaboration. Methodological expectations of campbell collaboration intervention reviews: conduct standards. Campbell Policies Guidel Ser. (2016) 3. doi: 10.4073/cpg.2016.3

26. Aloe AM, Dewidar O, Hennessy EA, Pigott T, Stewart G, Welch V, et al. Campbell standards: modernizing campbell’s methodologic expectations for campbell collaboration intervention reviews (MECCIR). Campbell Syst Rev. (2024) 20(4):e1445. doi: 10.1002/cl2.1445

27. Johnson BT, Hennessy EA. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses in the health sciences: best practice methods for research syntheses. Soc Sci Med. (2019) 233. (Journal Article):237–51. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.05.035

28. Haddaway NR, Page MJ, Pritchard CC, McGuinness LA. PRISMA2020: an R package and Shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and Open Synthesis. Campbell Syst Rev. (2022) 18:e1230. doi: 10.1002/cl2.1230

29. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. (2009) 42(2):377–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010

30. Mamikutty R, Aly AS, Marhazlinda J. Selecting risk of bias tools for observational studies for a systematic review of anthropometric measurements and dental caries among children. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18(16):8623. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18168623

31. Thomas BH, Ciliska D, Dobbins M, Micucci S. A process for systematically reviewing the literature: providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventions. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. (2004) 1(3):176–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2004.04006.x

32. Armijo-Olivo S, Stiles CR, Hagen NA, Biondo PD, Cummings GG. Assessment of study quality for systematic reviews: a comparison of the cochrane collaboration risk of bias tool and the effective public health practice project quality assessment tool: methodological research. J Eval Clin Pract. (2012) 18(1):12–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01516.x

33. McGuinness LA, Higgins JPT. Risk-of-bias VISualization (robvis): an R package and shiny web app for visualizing risk-of-bias assessments. Res Synth Methods. (2021) 12(1):55–61. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1411

34. Chiou CF, Hay JW, Wallace JF, Bloom BS, Neumann PJ, Sullivan SD, et al. Development and validation of a grading system for the quality of cost-effectiveness studies. Med Care. (2003) 41(1):32–44. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200301000-00007

35. Campbell M, McKenzie JE, Sowden A, Katikireddi SV, Brennan SE, Ellis S, et al. Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: reporting guideline. Br Med J. (2020) 368:l6890. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l6890

36. Kelly JF, Myers MG, Brown SA. A multivariate process model of adolescent 12-step attendance and substance use outcome following inpatient treatment. Psychol Addict Behav. (2000) 14(4):376–89. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.14.4.376

37. Hensel DJ, Wilburn VG. Daily association of drug use cravings and physical and emotional well-being among students attending a recovery high school during COVID-19: results from an EMA study. J Adolesc Health. (2023) 72(3):S88. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2022.11.178

38. Giles M. The Massachusetts recovery high schools: ensuring success in school and in recovery (Phd thesis). Brandeis University, The Heller School for Social Policy and Management (2022). Available online at: https://search.proquest.com/openview/963d364fe3a5cacf2dd2eb11a5970579/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y (cited October 21, 2024).

39. Knotts AC. Young people in recovery from substance use disorders: an analysis of a recovery high school’s impact on student academic performance & recovery success (Phd thesis). Indiana University, Indiana (2017). Available online at: https://scholarworks.iupui.edu/bitstream/1805/16280/1/Knotts_iupui_0104D_10282.pdf (cited October 21, 2024).

40. Finch AJ, Tanner-Smith E, Hennessy E, Moberg DP. Recovery high schools: effect of schools supporting recovery from substance use disorders. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. (2017) 44(2):175–84. doi: 10.1080/00952990.2017.1354378

41. Tanner-Smith EE, Finch AJ, Hennessy EA, Moberg DP. Effects of recovery high school attendance on Students’ mental health symptoms. Int J Ment Health Addict. (2019) 17(2):181–90. doi: 10.1007/s11469-017-9863-7

42. Tanner-Smith EE, Nichols LM, Loan CM, Finch AJ, Moberg DP. Recovery high school attendance effects on student delinquency and substance use: the moderating role of social problem solving styles. Prev Sci. (2020) 21(8):1104–13. doi: 10.1007/s11121-020-01161-z

43. Glaude MW, Jennings SW, Torres LR, Finch AJ. School of enrollment and perceptions of life satisfaction among adolescents experiencing substance use disorders. J Evid-Based Soc Work. (2019) 16(3):261–77. doi: 10.1080/26408066.2019.1588184

44. Tanner-Smith EE, Finch AJ, Hennessy EA, Moberg DP. Who attends recovery high schools after substance use treatment? A descriptive analysis of school aged youth. J Subst Abuse Treat. (2018) 89:20–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2018.03.003

45. Weimer DL, Moberg DP, French F, Tanner-Smith EE, Finch AJ. Net benefits of recovery high schools: higher cost but increased sobriety and increased probability of high school graduation. J Ment Health Policy Econ. (2019) 22(3):109–20.31811754

46. Lanham CC, Tirado JA. Lessons in sobriety: an exploratory study of graduate outcomes at a recovery high school. J Groups Addict Recovery. (2011) 6(3):245–63. doi: 10.1080/1556035X.2011.597197

47. Moberg DP, Finch AJ. Recovery high schools: a descriptive study of school programs and students. J Groups Addict Recovery. (2008) 2. (Journal Article):128–61. doi: 10.1080/15560350802081314

48. Hennessy EA, Jurinsky J, Cowie K, Pietrzak AZ, Blyth S, Krasnoff P, et al. Visualizing the influence of social networks on recovery: a mixed-methods social identity mapping study with recovering adolescents. Subst Use Misuse. (2024) 59(9):1405–15. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2024.2352618

49. Ashford RD, Brown AM, Curtis B. Collegiate recovery programs: the integrated behavioral health model. Alcohol Treat Q. (2018) 36(2):274. doi: 10.1080/07347324.2017.1415176

50. Brown AM, Ashford RD, Figley N, Courson K, Curtis B, Kimball T. Alumni characteristics of collegiate recovery programs: a national survey. Alcohol Treat Q. (2019) 37(2):149–62. doi: 10.1080/07347324.2018.1437374

51. Castedo de Martell S, Holleran Steiker L, Springer A, Jones J, Eisenhart E, Brown HS III. The cost-effectiveness of collegiate recovery programs. J Am Coll Health. (2022) 72(1):82–93. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2021.2024206

52. Gerber WM, Hune ND, Wang EW, Kimball TG. Tangible and intangible values of a CRP: a cost-benefit analysis. Alcohol Treat Q. (2022) 40(2):164–73. doi: 10.1080/07347324.2021.1979437

53. Nichols LM, Hennessy EA, Brown TB, Tanner-Smith EE. Co-occurring mental and behavioral health conditions among collegiate recovery program members. J Am Coll Health. (2021) 71(7):2085–92. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2021.1955687

54. Smith RL, Bannard T, McDaniel J, Whitney J, DeFrantz-Dufor W, Statman M, et al. Examining the associations between collegiate recovery programs and students' recovery capital and quality of life during the COVID-19 pandemic. Poster Abstracts. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. (2021) 45:80–262. doi: 10.1111/acer.14628

55. Smith RL, Bannard T, McDaniel J, Aliev F, Brown A, Holliday E, et al. Characteristics of students participating in collegiate recovery programs and the impact of COVID-19: an updated national longitudinal study. Addict Res Theory. (2024) 32(1):58–67. doi: 10.1080/16066359.2023.2216459

56. Vest N, Bell JS, Nieder A, Smith R, Bannard T, Tragesser S, et al. Learning with conviction: exploring the relationship between criminal legal system involvement and substance use and recovery outcomes for students in collegiate recovery programs. Drug Alcohol Depend. (2024) 257:111127. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2024.111127

57. Smith T. Sustaining recovery: the participant perspective of a collegiate recovery program. Diss Abstr Int. (2022) 83(10-B):1–118.

58. Botzet AM, Winters K, Fahnhorst T. An exploratory assessment of a college substance abuse recovery program: Augsburg College’s StepUP program. J Groups Addict Recovery. (2008) 2(2–4):257–70. doi: 10.1080/15560350802081173

59. Cleveland HH, Harris K. Conversations about recovery at and away from a drop-in center among members of a collegiate recovery community. Alcohol Treat Q. (2010) 28(1):78–94. doi: 10.1080/07347320903436268

60. Wiebe RP, Griffin AM, Zheng Y, Harris KS, Cleveland HH. Twelve steps, two factors: coping strategies moderate the association between craving and daily 12-step use in a college recovery community. Subst Use Misuse. (2018) 53(1):114–27. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2017.1325904

61. Knapp KS, Cleveland HH, Apsley HB, Harris KS. Using daily diary methods to understand how college students in recovery use social support. J Subst Abuse Treat. 20210414 ed. (2021) 130:108406. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108406

62. Laudet AB, Harris K, Kimball T, Winters KC, Moberg DP. In college and in recovery: reasons for joining a collegiate recovery program. J Am Coll Health. (2016) 64(3):238–46. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2015.1117464

63. Patterson MS, Russell AM, Nelon JL, Barry AE, Lanning BA. Using social network analysis to understand sobriety among a campus recovery community. J Stud Aff Res Pract. (2020) 58(4):401–16. doi: 10.1080/19496591.2020.1713142

64. Wattick RA, Hagedorn RL, Olfert MD. Enhancing college student recovery outcomes through nutrition and culinary therapy: mountaineers for recovery and resilience. J Nutr Educ Behav. (2020) 52(3):326–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2019.11.006

65. Odefemi-Azzan OA. Factors that affect students enrolled in a midsize collegiate recovery program in the United States (ProQuest Dissertations & Theses). St. Peter's University, Jersey City, NJ, United States (2020).

66. Bennett ME, McCrady BS, Keller DS, Paulus MD. An intensive program for collegiate substance abusers progress six months after treatment entry. J Subst Abuse Treat. (1996) 13(3):219–25. doi: 10.1016/S0740-5472(96)00045-1

67. Tuliao AP, Tuliao MD, Lewis LE, Mullet ND, North-Olague J, Mills D, et al. Perceptions of addiction medications within collegiate recovery communities. J Addict Med. (2023) 17(6):732–5. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000001224

68. Herold MA. Student perceptions of the effectiveness of collegiate recovery programs and collegiate recovery communities (ProQuest Dissertations & Theses). The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, Edinburg, TX, United States (2023).

69. Hamner LC. The Influence of Authentic Leadership on Recovery Capital in a Collegiate Setting. San Antonio, TX: Our Lady of the Lake University (2023). Available online at: https://search.proquest.com/openview/80d034820124e56e7670bc10febe777a/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y (cited October 21 2024).

70. Botzet AM, Mcilvaine PW, Winters KC, Fahnhorst T, Dittel C. Data collection strategies and measurement tools for assessing academic and therapeutic outcomes in recovery schools. Peabody J Educ. (2014) 89(2):197–213. doi: 10.1080/0161956X.2014.895648

71. Hennessy EA, Finch AJ. Adolescent recovery capital and recovery high school attendance: an exploratory data mining approach. Psychol Addict Behav. (2019) 33(8):669. doi: 10.1037/adb0000528

72. Groshkova T, Best D, White W. The assessment of recovery capital: properties and psychometrics of a measure of addiction recovery strengths. Drug Alcohol Rev. (2013) 32(2):187–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2012.00489.x

73. Vilsaint CL, Kelly JF, Bergman BG, Groshkova T, Best D, White W. Development and validation of a brief assessment of recovery capital (BARC-10) for alcohol and drug use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend. (2017) 177. (Journal Article):71–6. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.03.022

74. Castedo de Martell S. Cost-Effectiveness Of Collegiate Recovery Programs [Internet]. UTHealth School of Public Health; 2019. Available online at: https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/uthsph_dissertsopen/42/ (cited 2024 October 21).

75. Couwenbergh C, van den Brink W, Zwart K, Vreugdenhil C, van Wijngaarden-Cremers P, van der Gaag RJ. Comorbid psychopathology in adolescents and young adults treated for substance use disorders. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2006) 15(6):319–28. doi: 10.1007/s00787-006-0535-6

76. Lamps CA, Sood AB, Sood R. Youth with substance abuse and comorbid mental health disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. (2008) 10(3):265–71. doi: 10.1007/s11920-008-0043-0

77. Bunaciu A, Bliuc AM, Best D, Hennessy EA, Belanger M, Benwell C. Measuring recovery capital for people recovering from alcohol and drug addiction: a systematic review. Addict Res Theory. (2024) 32(3):225–36. doi: 10.1080/16066359.2023.2245323

78. Oser R, Karakos HL, Hennessy EA. Disparities in youth access to substance abuse treatment and recovery services: how one recovery school initiative is helping students “change tracks.”. J Groups Addict Recovery. (2016) 11(4):267–81. doi: 10.1080/1556035X.2016.1211056

79. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). 2021 National Surveys on Drug Use and Health: Model-Based Estimated Totals (in Thousands) (50 States and the District of Columbia) - Table 28 [Internet]. Available online at: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2021-nsduh-estimated-totals-state (Accessed September 10, 2024).

Keywords: collegiate recovery communities, collegiate recovery programs, recovery capital for adolescents model, recovery high school, systematic review

Citation: Hennessy EA, George SS, Klein MR, O’Connor JB, Eddie D and Kelly JF (2025) A systematic review of recovery high schools and collegiate recovery programs for building recovery capital among adolescents and emerging adults. Front. Adolesc. Med. 3:1522678. doi: 10.3389/fradm.2025.1522678

Received: 4 November 2024; Accepted: 23 January 2025;

Published: 17 February 2025.

Edited by:

Anita Cservenka, Oregon State University, United StatesReviewed by:

Bo Cleveland, The Pennsylvania State University (PSU), United StatesHannah Apsley, The Pennsylvania State University (PSU), United States

George Comiskey, Texas Tech University, United States

Copyright: © 2025 Hennessy, George, Klein, O'Connor, Eddie and Kelly. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Emily A. Hennessy, ZWhlbm5lc3N5QG1naC5oYXJ2YXJkLmVkdQ==

Emily A. Hennessy

Emily A. Hennessy Shane S. George

Shane S. George Morgan R. Klein

Morgan R. Klein Jenny B. O’Connor

Jenny B. O’Connor David Eddie

David Eddie John F. Kelly

John F. Kelly