95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Public Health , 21 March 2025

Sec. Aging and Public Health

Volume 13 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1570794

This article is part of the Research Topic Enhancing Geriatric Care: International Collaboration and Best Practices for Aging Populations View all 11 articles

Background: The acceleration of China’s aging process makes examining policy experiences from LTCI pilot cities highly significant for advancing the LTCI system in China and other emerging nations.

Methods: Policy documents were gathered using Citespace 6.3.R1, with primary data sources obtained from official government websites. A comparative study of LTCI policies in pilot cities was conducted, focusing on policy support, participation scope, financing channels, benefit provision, care conditions, and management structures to evaluate the programs’ logic.

Results: Pilot cities have developed distinct approaches in the LTCI development process. However, issues persist, including a singular financing channel, misalignment between benefit provision supply and demand, substandard care quality, and the need for improved management effectiveness.

Discussion: Establishing a sustainable LTCI system requires implementing an independent financing mechanism and a standardized financial model, developing an efficient LTCI service supply framework, strengthening LTCI oversight and administration, and fostering the commercial insurance market.

The rapid aging of population worldwide has increased the demand for geriatric care and medical treatment services, especially in the post–COVID-19 era (1). The issue of poor geriatric care services has received significant scholarly attention (2, 3). China has one of the world’s oldest populations, with over 296.97 million people aged 60 years or older by the end of 2023, representing 21.1% of the country’s total population. Among them, 216.76 million people are aged 65 years or older, accounting for 15.4% of the overall population, with a dependency ratio of 22.5% (4, 5). The prevalence of semi-disability and disability is rising, affecting approximately 35 million older adult people, or 11.6% of China’s older adult population, with a prevalence rate four times higher than that of the general population. The average duration of illness exceeds 8 years (6). Projections indicate that the number of older persons with disabilities in China may reach 46 million by 2035 and roughly 58 million by 2050 (7). The number of older persons requiring assistance for activities of daily living (ADLs) is rapidly increasing (8). However, conventional care given by senior family members is inadequate in China due to delayed childbearing and declining family sizes (9). Furthermore, the quality of such care is typically low, which has a negative impact on both caregivers’ well-being and older people’s rehabilitation (10).

Some high-income nations, like the Netherlands in 1968, the United States in the 1970s, Germany in 1995, and Japan in 2000, have implemented the LTCI program to address these issues (11, 12). The program provides monetary compensation and service protection for individuals requiring continuous care, such as those with cognitive impairments and disabilities, through institutionalized arrangements designed to mitigate the risks associated with population aging and establish a multilevel care protection system (13, 14). The World Health Organization (WHO) has recommended that China incorporate LTCI policies into its healthcare system to address older adult and disability care challenges (15–18). China’s LTCI initiative began in Qingdao in 2012, followed by phased LTCI pilots in 15 locations in 2016 and 2018 (19). By the end of 2022, trial cities had 331,000 care service professionals, 7,679 care service organizations, 16,992,000 LTCI members, and 12,080,000 individuals receiving treatment (20). However, the United Nations’ World Population Prospects report estimates that by 2050, over 500 million people in China aged 60 years or older, and by 2080, over 46% of the country’s population will be 65 years or older (21). The development of LTCI in China remains in its exploratory stage, and there is still a gap between the current available options and the need for older adult care (19). The Chinese government stated that it “will accelerate the construction of LTCI system” by 2025 in the Opinions on Deepening the Reform and Development of Older Adult Care Services, released in December 2024 (22).

In the future, the LTCI policy will be expanded by the Chinese government and applied across the country (22). However, China’s aging population, the swift increase in demand for aged care, and the global economy’s transition to slower growth present challenges in formulating an effective LTCI policy (10). Evaluating LTCI policies in pilot cities is essential for Chinese government officials and policymakers tasked with future decision-making (23). The main goal of this study is to enhance the analysis of China’s LTCI policy from both empirical and normative viewpoints. Limited research has been conducted on China’s LTCI policy, with most studies focusing on the financial mechanisms of the healthcare system and basic medical insurance for urban workers, which alleviates financial burdens on households and the government (24). This underscores the need for research evaluating the outcomes and effectiveness of China’s LTCI policy as a pilot initiative. Existing research on China’s LTCI policy primarily relies on conventional cognitive frameworks, focusing on conceptual constructions, operational mechanisms, and implementation strategies (25). This study examines the policy institutional framework of LTCI pilot cities in China to address these gaps. The second objective is to examine whether LTCI policies are facilitating the advancement of China’s healthcare insurance system. Current research indicates that LTCI has emerged as the “sixth insurance” within China’s social security framework and represents a significant policy initiative aimed at reforming the country’s healthcare system. The final objective of this study is to develop more progressive and socially pertinent LTCI policy recommendations for policymakers in China’s pilot cities.

Since the launch of China’s LTCI policy pilot cities in 2016, an increasing body literature assessed this policy across three research phases: prior to 2016, the literature predominantly focused on the feasibility and necessity of LTCI, including analyses of LTCI systems in countries such as Germany and Japan, and outcomes of LTCI implementation in pilot cities like Qingdao (26–30). Between 2016 and 2018, the literature predominantly examined LTCI pilot regions in China and drew insights from international pilot experiences to optimize institutional design and LTCI implementation (31–34). Following 2018, as the development of LTCI accelerated, scholarly interest expanded to specific components of the policy, including examining the pilot policy and procedural aspects of system design, such as comparative analyses of the beneficiaries (35–37), financing mechanisms (38, 39), reimbursement standards (40), and service coverage (41). Additionally, studies have investigated the impacts on national finance and labor markets post-implementation of the LTCI policy, although comparative analyses of pilot regions remain limited (42). Current LTCI policy research is predominantly uniform. While interdisciplinary studies have examined LTCI from many viewpoints, it lacks a cohesive integration of theory and practice. Moreover, there is a paucity of studies evaluating the effectiveness of China’s LTCI pilot regions. Existing research on the efficacy of LTCI policies seldom employs the policy evaluation theory, often categorizing policy dimensions based on participating entities and the policies themselves, thereby lacking scientific theoretical frameworks and logical coherence.

Chengdu, Qingdao, and Shanghai are among the initial pilot cities in China that have yielded favorable outcomes in the pilot phase, exemplifying the more progressive practices of China’s current LTCI system (43). Consequently, they also signify the future trajectory of LTCI development in China, which is dedicated to establishing a unified national LTCI framework. Thus, analyzing their experiences provides valuable insights into LTCI implementation nationwide. Consequently, drawing from the experiences of the pilot advanced regions, there exists a degree of universality in the analysis of the LTCI system’s implementation in China. Qingdao was the first region in China to implement the LTCI system and achieve comprehensive coverage among LTCI participants. In 2016, 15 cities, including Chengdu, Qingdao, and Shanghai, were designated as the initial pilot cities for the LTCI system in 2016. Shanghai has the highest number of individuals benefiting from LTCI in China, while Chengdu has the largest GDP and resident population in southwestern China. Furthermore, Chengdu had the highest total GDP and resident population in Southwest China and included both those with mild disabilities and those with dementia in its LTCI pilot program (44). Chengdu, Qingdao, and Shanghai represent pilot experiences in western, eastern, and northern China, respectively, and are equally indicative of the area. These cities also have a distinct advantage over other pilot cities regarding the accessibility of operational data pertaining on the LTCI system (45, 46).

Furthermore, Chengdu, Qingdao, and Shanghai are experiencing demographic aging, leading to a heightened need for older adult care; hence, the examination of LTCI holds substantial relevance for these three cities regarding geriatric care and healthcare provision. China’s seventh population census indicated that in 2020, individuals aged 65 and older in Chengdu, Shanghai, and Qingdao was 13.62, 16.3, and 14.2%, respectively, surpassing the national average of 13.5% (47). Consequently, examining the LTCI frameworks in these cities holds significant importance for other pilot cities in China.

The data for this study was sourced from the official websites of the Chinese government, including the National Health Insurance Bureau, the Social Security Bureau, and the municipal governments of Shanghai, Chengdu, and Qingdao. Two researchers conducted independent searches concurrently using keywords such as “long-term care insurance” and “long-term care.” The keywords included “long-term care insurance,” “long-term care,” and similar terms. The inclusion criteria required that the issuing entity be a governmental department from Shanghai, Chengdu, or Qingdao and that the content be significantly relevant to LTCI, primarily including laws, regulations, judgments, opinions, provisional measures, and notices. Exclusion criteria included policy interpretations, news articles, and other non-original policy materials, as well as keywords that lacked specific LTCI content within the policy texts. The publishing period was set from January 2016 to December 2024 to ensure the study’s uniqueness and continuity. Following the search, extraneous texts were manually removed and re-evaluated multiple times to ensure the reliability of the findings, guaranteeing that the collected texts accurately represented the development of LTCI policy.

The LTCI policy texts from Shanghai, Chengdu, and Qingdao were collected and analyzed using Citespace 6.3.R1, developed by Prof. Chaomei Chen. The objective was to conduct a comparative textual analysis to examine similarities and differences in the three cities’ LTCI systems, identify issues and their root causes, and provide detailed descriptions of LTCI policies concerning policy support, coverage scope, financing, payment, and care. This analysis highlights key practices, accomplishments, and weaknesses. Additionally, the study delineates LTCI policies in terms of policy support, participation breadth, financing, payment, and care while summarizing the principal practices, achievements, and deficiencies.

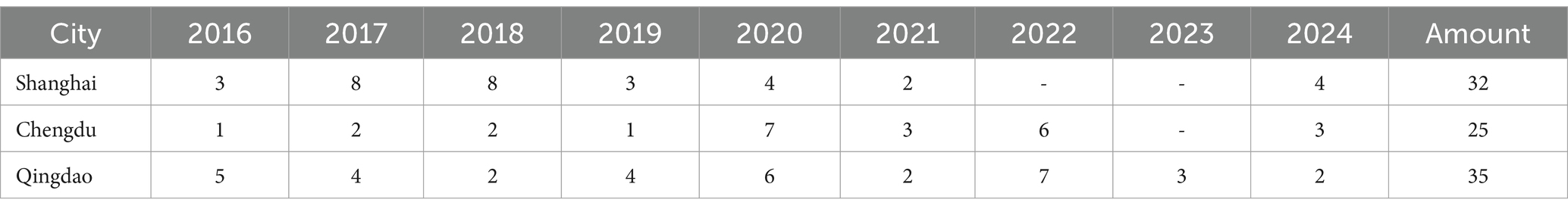

Since 2016, the number of LTCI-related local government documents released in Shanghai, Chengdu, and Qingdao, excluding informal government documents such as programs, stands at 32, 25, and 35, respectively. Chengdu has issued 12 local normative documents and four local working documents, Qingdao has released 15 local normative documents and 16 local working documents, while Shanghai has produced 21 local normative documents and six local working documents. Chengdu has comparatively fewer normative documents due to two primary factors: its pilot initiatives began later than those in Shanghai and Qingdao, resulting in inadequate preliminary research and predominantly non-governmental planning documents, and its aging demographic is relatively moderate, leading to unclear delineation of LTCI management responsibilities and a lower frequency of policy formulation (Table 1).

Table 1. Number of long-term care insurance documents issued in Shanghai, Chengdu, and Qingdao over the years.

Chengdu, Qingdao, and Shanghai encompass both urban laborers and urban and rural inhabitants. The Chengdu LTCI participants include employees, residents, students, and children. Participants in provincial basic medical insurance are aligned to engage in Chengdu’s LTCI (48), and those enrolled in basic medical insurance under the single-build integrated model may opt to participate voluntarily (49). Chengdu and Qingdao impose no age restrictions on participants, while Shanghai mandates that resident participants be of at least 60 years (50, 51) (Table 2).

Shanghai relies solely on a single financing channel, exclusively dependent on the integrated medical insurance fund (52), whereas Chengdu and Qingdao utilize diversified financing avenues, including medical insurance funds, individual contributions, and government financial subsidies. In these cities, unit contributions are allocated directly from medical insurance funds, individual contributions are deducted from personal medical insurance accounts, and government financial subsidies come from medical insurance allocations.

Regarding financing standards, all three locations differentiate contributions based on employee and resident participation, except for Qingdao’s resident participation, which follows a fixed financing amount primarily based on the health insurance contribution base. A proportional financing method is applied, with the financing benchmark for employees exceeding that for residents (53). Shanghai exhibits the highest contribution base and ratio while exempting specific demographics, such as low-income groups, from contributions. Although Chengdu’s employee participation rate is lower than Qingdao’s, its resident participation is funded at a higher level. Chengdu’s employee financing structure also establishes varying individual contribution rates based on age and implements a differentiated subsidy policy, offering proportional subsidies for employees and fixed amounts for urban and rural residents, students, and children, including college students (49). The contribution base categorizes participants according to unique circumstances, employing both pass-through and hospitalization funding methods (Table 3).

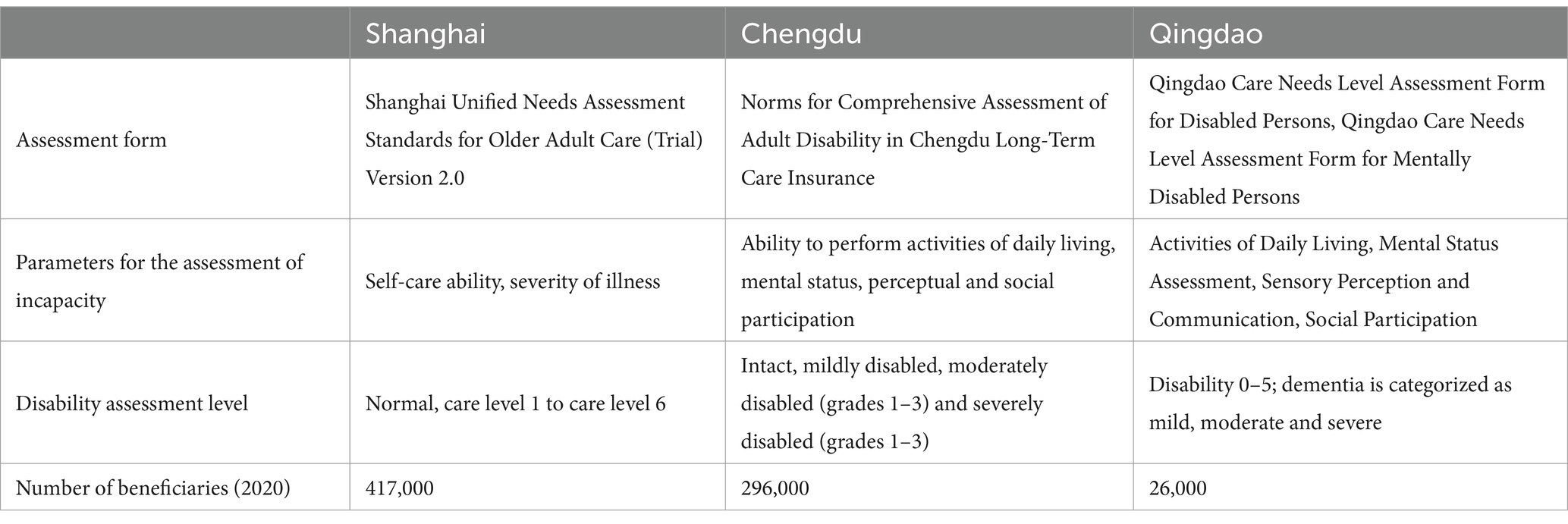

All three cities have established their own disability assessment criteria. Chengdu and Qingdao follow the Trial Standards for Assessing Disability Levels published by the Health Insurance Bureau in 2021 (54), with Qingdao further differentiating criteria for individuals with disabilities and intellectual disabilities.

Chengdu and Qingdao assess four dimensions: daily living activities, mental status, perception and communication abilities, and social participation, which were subdivided into 19 and 22 indicators, respectively. The results were derived by aggregating the ratings of each dimension. Qingdao incorporates diagnostic assessments from medical institutions and specialists in its evaluation outcomes. Shanghai’s disability assessment criteria focus on self-care capability and illness severity, subdividing self-care capability into 50 specific indicators. The disability evaluation in Shanghai is predicated on the illness dimension, which markedly differs from that of Chengdu and Qingdao (55–57) (Table 4).

Table 4. Disability assessment status of long-term care insurance in Shanghai, Chengdu, and Qingdao.

Regarding payment methods, Shanghai and Qingdao offer home care, institutional care, and daycare services, while Chengdu provides only home and institutional care and has yet to develop a community daycare model. Qingdao classifies care services into six types: home care, itinerant care, skilled nursing care, residential care, dementia care, and specialized care, with dementia care being the first of its kind in the country. In terms of financial support, the home care offerings in Chengdu and Shanghai closely resemble those of institutional care, although Qingdao’s institutional care services are comparatively more diverse.

In terms of financial support, Shanghai provides the highest payment sum among the three cities. Each city differentiates between employee and resident participants, implements a proportionate payment system, and establishes a payment cap. The home care model possesses the highest reimbursement rate. Concerning the payment limit, Chengdu and Qingdao explicitly delineate specific payment limits in their respective regulations, whereas Shanghai establishes the limit through negotiations between individuals and care providers, restricting the number of services and the duration of treatment. Payment norms and restrictions for employees in all three cities exceed those for residents, with the health insurance coordination fund significantly contributing to the disbursement of benefits (58) (Table 5).

All nursing care organizations have used the paradigm of agreement management for their regulation. Nursing institutions are categorized based on the services they offer, with Qingdao additionally classifying institutions based on the number of nursing beds, stipulating that only those with at least 30 nursing beds classify as residential nursing service institutions (59).

Concerning the evaluation of nursing care organizations, each city has established its own evaluation standards and defined unique criteria for assessment. The evaluation criteria in Qingdao encompass several elements, such as environment, management, services, and social impact, with care services assigned the highest importance, underscoring the divergent assessment priorities compared with those of Chengdu and Shanghai. Furthermore, in contrast to Chengdu and Qingdao, which employ standardized assessment criteria citywide, Shanghai’s evaluation metrics are determined by each district based on its own circumstances (60–62).

Concerning the nursing workforce, there exists a pervasive issue of inadequate staffing, predominantly comprising females, older adult individuals, and those possessing relatively poor educational qualifications. To resolve the disparity between the supply and demand for nursing staff and enhance the quality of nursing care, Chengdu has conducted multiple training programs for nursing personnel by engaging third-party institutions to elevate their professionalism. Conversely, Qingdao has released a policy paper regarding the training mechanism for nursing personnel, with the city’s medical insurance agency tasked with arranging and executing the training, thereby further standardizing the nursing personnel training process. Conversely, Shanghai has created its own regulations for the training of nursing personnel, according to local circumstances. For instance, Hongkou District has not only created a nursing talent pool but also elevated the pay of nursing personnel, resulting in Shanghai offering superior compensation and a more sufficient reserve of nursing staff (63–66) (Table 6).

The Medical Protection Bureau serves as the responsible authority for LTCI management in all three regions, designating its subordinate unit as the operational and management organization. Chengdu’s management regulations only identify the competent authority and operational organization, without detailing the responsibilities of other government departments. In contrast, Qingdao and Shanghai provide explicit definitions of the responsibilities of caregiver training and fund management departments.

All three cities engage commercial insurance firms in LTCI payment processing and disability evaluations. In Shanghai and Chengdu, commercial insurers contribute to system development and management, while in Qingdao, they also oversee fund management (50, 51).

Chengdu employs a regional operation model, permitting each region to independently contract commercial insurers for the management and operation of their respective areas. In contrast, Shanghai and Qingdao employ an exclusive operation model, wherein a single insurer oversees the operation and management of the entire region. Shanghai has engaged commercial insurers to manage operational tasks for a limited duration, with the trial initiative only conducted in Putuo District (67).

Moreover, all three cities are actively investigating the development of LTCI platforms, intending to use the “Internet Plus” trend to enhance informatization and intelligent infrastructure. Shanghai has implemented online disability assessment processing via WeChat public accounts and mini-programs, alongside real-time monitoring of care service quality to enhance supervision. Qingdao and Chengdu have developed specialized mobile applications and other online tools to actively facilitate the online processing of disability assessments. Nevertheless, shortcomings persist in the development of information intelligence in the three cities, indicating substantial potential for enhancement (Table 7).

Regarding the medical insurance fund, pertinent research indicate that the current sustainability of China’s urban workers’ medical insurance fund is robust, although the rate of increase in its sustainability has decelerated (68, 69). Certain studies have explicitly shown that the existing employee medical insurance framework may jeopardize the stability of the coordinated fund due to the LTCI model for employees derived from urban employees’ medical insurance (70). The yearly balance rate of the Chengdu fund was <10% in 2017, 2019, and 2021 (71–73). In Qingdao, the employee care fund amounted to 1.1 billion yuan in 2021, while the resident care fund totaled 145 million yuan (74). The overall expenditure of the care fund was approximately 677 million yuan, which seemed substantial at first glance; however, only 42,000 individuals actually received benefits (75). In 2021, the magnitude of Shanghai’s health insurance fund attained 522.9 billion yuan; however, if financed at the 1% ratio stipulated in Shanghai’s previous pilot scheme, the fund would only amount to 5.23 billion yuan, whereas the expenditure for establishing an LTCI system is significantly higher at 11.92 billion yuan (76). Certain researchers project that the expenditure for LTCI would amount to 224.134 billion yuan by 2030 and escalate to 618.120 billion yuan by 2050, indicating that the existing finance model is unable to accommodate the linear growth in the financial demands of LTCI (77). Consequently, the long-term viability of the basic medical insurance fund is under considerable strain.

Chengdu and Qingdao exhibit disparities in reimbursement rates and maximum reimbursement limits for care services between employee and resident participants, with employee participants receiving more benefits than their resident counterparts. While this aligns with the contribution rates of the two participant categories, the cost of care for disabled individuals is determined by the severity of their condition rather than their employment or residency status. Simultaneously, the cost of nursing care services is relatively high, and those with lower incomes should benefit from an increased reimbursement threshold.

Chengdu and Shanghai have implemented the same evaluation methods and criteria for assessing individuals with disabilities and dementia. However, disability and dementia are distinct conditions. Disability primarily refers to physical impairments, requiring an emphasis on self-care and mobility, whereas dementia pertains to cognitive impairments, necessitating attention to thought processes and memory. Different evaluation criteria must be used to distinguish between the two. While Qingdao differentiates between them, its criteria for assessing dementia remain simplistic, relying solely on memory and orientation while neglecting aspects such as self-care and spatial awareness, which require further refinement.

Chengdu, Qingdao, and Shanghai face a shortage of caretakers. In 2020, the proportion of impaired older adult individuals relative to the total older adult population in China was 16.6% (78). Based on this ratio, the estimated number of disabled older adult individuals in Chengdu, Qingdao, and Shanghai in 2020 was 353,600, 339,100, and 965,400, respectively. In the same year, the nursing staff in Chengdu, Qingdao, and Shanghai numbered approximately 20,000, 12,000, and 75,000, respectively, significantly below the stipulated 1:10 ratio of nursing staff to self-care individuals outlined in the “Norms for Job Setting and Staffing of Elderly Institutions” issued by the Department of Older Adult Services of the Ministry of Civil Affairs of China (79), revealing a substantial disparity with international standards (80).

Alongside the shortage of nursing personnel, there are inadequacies in the qualifications of nursing staff in Chengdu, Qingdao, and Shanghai. The quality of caregivers is inconsistent. The educational attainment of caregivers in these cities is predominantly low, with few holding a bachelor’s degree. There is also a deficiency in caregiving training and a lack of standardized training protocols. Furthermore, caregivers tend to be older, predominantly middle-aged women. The turnover rate among nursing personnel is high. Nursing work intensity is considerable, with many working over 10 h a day. However, nursing staff salaries are low, falling below the local average wage.

Collaboration with external organizations in the three regions is inadequate. In Shanghai, the medical insurance center primarily handles administrative management, with collaboration with commercial insurance firms in operational management occurring solely in Putuo District as part of a trial initiative. Additionally, in Qingdao and Shanghai, commercial insurance firms oversee the entire management process, from disability evaluation to benefit disbursement, without distinguishing between assessment and payment management. This may lead to conflicts of interest that could compromise the objectivity of evaluations.

Chengdu, Qingdao, and Shanghai also exhibit shortcomings in the informatization and intelligent development of LTCI (81). Despite the establishment of online information systems in all three cities, user feedback on their effectiveness has been unsatisfactory. In Chengdu and Qingdao, online LTCI services are limited to incapacity assessment apps, while in Shanghai, online functionalities are primarily used for monitoring care processes, resulting in a restricted expansion of online services. Additionally, many older adult individuals are unfamiliar with online operations, negatively affecting their experience with the program. The development of smart care equipment and institutions is progressing slowly and requires further improvement.

The sustained advancement of LTCI primarily relies on the efficient allocation of expenditures. In China, the LTCI fund is still in its early stages, and a robust insurance funding system has yet to be established. In pilot cities, financing sources include medical insurance funds, contributions from individuals and organizations, financial subsidies, and allocations from social welfare and public welfare budgets. To reduce the financial burden of social insurance on businesses, some cities temporarily reallocated funds from the medical insurance fund during the pilot period (82–84). Certain cities provide financial subsidies based on economic development levels, making the health insurance fund the primary source of LTCI funding in China. We propose a comprehensive funding structure that incorporates government agencies, business entities, individuals, and third-party commercial insurers, drawing on models from other countries. This framework aims to create a balanced and systematic approach to the development of LTCI funds. Given China’s current and future economic trajectory, potential financing channels for LTCI can be categorized into five groups: government subsidies, health insurance funds, housing provident funds, social donations, and individual contributions. Social contributions encompass philanthropic donations, public welfare funds from lotteries, business financing, and other methods. The government must optimize fund allocation, improve the conversion rate of the health insurance fund, enhance fund autonomy, and ensure that funding levels correspond with economic development to meet the healthcare needs of the older adult population.

The LTCI service system comprises nursing facilities, individual service providers, and management organizations. Currently, China faces a shortage of beds in healthcare and professional nursing facilities, leading to limited availability (85). Consequently, the care needs of disabled older adult individuals must be met by private nursing institutions. However, several obstacles hinder the development of private care facilities in China, resulting in outdated technology and facilities, as well as an uneven distribution of skilled workers. These challenges have limited the ability of private institutions to meet the needs of the older adult disabled population. The National Nursing Care Development Plan of China (2021–2025) recommends enhancing the integration of medical care and supporting the establishment of private nursing institutions (86). In the long term, encouraging private care institutions to participate in LTCI is a key objective and a crucial method to challenges of an aging population. The proficiency of caregivers is intrinsically linked to the efficacy of long-term care. Despite significant advancements in caregiver training in China, the country continues to confront challenges, including an aging workforce, inadequate educational attainment, elevated turnover rates, a lack of willingness to pursue the profession, and a rising demand for services at low wage levels (87). To resolve these issues, it is imperative to build professional nursing training institutions, develop a cohesive training system along with evaluation and assessment mechanisms, enhance faculty involvement and policy support, and elevate the professional quality and skill level of nursing personnel. Furthermore, an equitable system of occupational subsidies must to be established to cultivate a feeling of professional dignity, eradicate societal misconceptions and biases regarding the senior care profession, enhance the social standing of caregivers, and entice a greater number of young individuals into the field.

The efficient functioning of LTCI necessitates a thorough and rigorous oversight and management structure. It is essential for the insured to establish explicit admission and discharge criteria, precisely evaluate health status and disability levels, and tackle the issues arising from inadequate or excessive service provision by employing a methodology that integrates random sampling with systematic monitoring and follow-up visits. Concerning service providers, the business license, staffing, and bed capacity should constitute the fundamental criteria for inclusion in LTCI. Local health insurance agencies must collaborate with experts from accredited healthcare organizations to perform a thorough evaluation of care providers’ qualifications and establish a systematic assessment framework. It is essential to enhance the oversight of the content and quality of institutional services. Moreover, pilot cities should employ varying criteria for evaluating LTCI quality, with quality management primarily falling under the jurisdiction of district-level health insurance agencies that report to municipal authorities. However, due to the diverse settings in which services are delivered, including private institutions, residences, and public hospitals, it is challenging for supervisory agencies to acquire accurate and actionable information. To resolve these issues, a robust quality assessment system must be implemented, utilizing known healthcare quality management methodologies. The system must encompass the evaluation of service receivers, credentials of service professionals, substance and timetable of services, a mechanism for gathering service-related data, and standardization of service procedures.

The Research Report on Long-Term Care Insurance by the Institute for Research on Aging at Fudan University indicates that China’s LTCI market exhibits notable deficiencies in medical and other specialized services, with demand from disabled older adult individuals significantly surpassing supply (88). China has initiated a pilot program that allows commercial insurance entities to engage in LTCI across 13 cities. Estimates indicate that the total demand for LTCI services for the older adult in urban areas of China in 2021 will approximate 1.4 trillion yuan, whereas protective measures, comprising household expenditures and policy-based LTCI and subsidies, will fall short of 500 billion yuan, resulting in a deficit of 921.7 billion yuan (82). In response to the increasing demand for older adult care services, it is essential to broaden the commercial older adult care insurance market and motivate more seniors to proactively select third-party older adult care insurance products, thereby alleviating the burden of policy-based insurance. Simultaneously, it is crucial to proactively investigate the development of a multilayer pension service system that amalgamates home, community, and institutional assistance, while persistently enhancing China’s LTCI market.

KD: Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – original draft. YL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. YH: Data curation, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by National Social Science Fund of China (2024-SKJJ-C-034) and Social Science Cultivation Fund of Naval Medical University (2023SK018).

We thank Charlesworth (www.cwauthors.com) for its linguistic assistance during the preparation of this manuscript.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Xu, X, Huang, X, Zhang, X, and Chen, L. Family economic burden of elderly chronic diseases: evidence from China. Healthcare. (2019) 7:99. doi: 10.3390/healthcare7030099

2. Yu, Y, and Sloan, FA. Trends in elderly health by cohort: evidence from China. China Econ Rev. (2017) 44:282–95. doi: 10.1016/j.chieco.2017.05.001

3. Courbage, C, Montoliu-Montes, G, and Wagner, J. The effect of long-term care public benefits and insurance on informal care from outside the household: empirical evidence from Italy and Spain. Eur J Health Econ. (2020) 21:1131–47. doi: 10.1007/s10198-020-01215-7

4. Lei, X, and Bai, C. Cognitive function and mental health of elderly people in China: findings from 2018 Clhls survey. China Popul Dev Stud. (2020) 3:343–51. doi: 10.1007/s42379-020-00054-6

5. Ministry of Civil Affairs, China. 2023 National Aging Development Bulletin. (2024). Available online at: https://www.gov.cn/lianbo/bumen/202410/content_6979487.htm (Accessed February 25, 2025).

6. China Research Center on Aging. The fifth sample survey on the living conditions of urban and rural senior residents. (2024). Available online at: http://www.crca.cn/index.php/19-data-resource/life/1117-2024-10-17-08-01-05.html (Accessed February 1, 2025).

7. Zhang, L, Fu, S, and Fang, Y. Prediction of the number of and care costs for disabled elderly from 2020 to 2050: a comparison between urban and rural areas in China. Sustain For. (2020) 12:2598. doi: 10.3390/su12072598

8. Feng, Z, Glinskaya, E, Chen, H, Gong, S, Qiu, Y, Xu, J, et al. Long-term care system for older adults in China: policy landscape, challenges, and future prospects. Lancet. (2020) 396:1362–72. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32136-X

9. Fang, EF, Xie, C, Schenkel, JA, Wu, C, Long, Q, Cui, H, et al. A research agenda for ageing in China in the 21st century (2nd edition): focusing on basic and translational research, Long-term care, policy and social networks. Ageing Res Rev. (2020) 64:101174. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2020.101174

10. Zhang, Y, and Yu, X. Evaluation of Long-term care insurance policy in Chinese pilot cities. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:3826. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16203826

11. Campbell, JC, Ikegami, N, and Gibson, MJ. Lessons from public long-term care insurance in Germany and Japan. Health Aff. (2010) 29:87–95. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0548

12. Ikegami, N. Rationale, design and sustainability of long-term care insurance in Japan – in retrospect. Soc Policy Soc. (2007) 6:423–34. doi: 10.1017/S1474746407003739

13. Dai, W, Li, Y, and Shen, J. The pilot programme of long-term care insurance in China: fragmentation and policy implications. China Int. J. (2022) 20:186–206. doi: 10.1353/chn.2022.0010

14. Xiao, S. From welfare statism to welfare pluralism: cases of Nanjing and Lanzhou. J. Tsinghua Univ. (2001) 16:16–23.

15. Blondeau, J, and Dubois, D. Financing old-age dependency in Europe: towards overall management of old-age. Geneva Papers Risk Insurance Issues Pract. (1997) 22:46–59. doi: 10.1057/gpp.1997.5

16. Glendinning, C. ed. Rights and realities: comparing new developments in long-term care for older people. Policy Press. (1998).

17. Geraedts, M, Heller, GV, and Harrington, CA. Germany's long-term care insurance: putting a social insurance model into practice. Milbank Q. (2000) 78:375–401, 340. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00178

18. Fine, M, and Chalmers, J. ‘User pays’ and other approaches to the funding of long-term care for older people in Australia. Ageing Soc. (2000) 20:5–32. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X99007643

19. Jia, L, Quan, M, Fu, Y, Zhao, T, Li, Y, Wei, C, et al. Dementia in China: epidemiology, clinical management, and research advances. Lancet Neurol. (2020) 19:81–92. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(19)30290-x

20. National Healthcare Security Administration, China. 2022 National Medical Security Industry Development Statistical Bulletin. (2023). Available online at: https://www.nhsa.gov.cn/art/2023/7/10/art_7_10995.html (Accessed February 1, 2025).

21. UN Department of economic and social affairs. World population prospects 2024: summary of results. (2024). Available online at: https://desapublications.un.org/publications/world-population-prospects-2024-summary-results (Accessed March 16, 2025).

22. State Council, China. Opinions on deepening the reform and development of elderly care services. (2024). Available online at: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/202501/content_6996775.htm (Accessed February 1, 2025).

23. World Trade Organization. World trade report 2024. WTO (2024). Available online at: https://www.wto-ilibrary.org/content/books/9789287076717(Accessed March 16, 2025).

24. Feng, Q, Yeung, W-JJ, Wang, Z, and Zeng, Y. Age of retirement and human capital in an aging China, 2015-2050. Eur J Popul Revue Eur De Demographie. (2019) 35:29–62. doi: 10.1007/s10680-018-9467-3

25. Wang, Q, Zhou, Y, Ding, X, and Ying, X. Demand for long-term care insurance in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2018) 15:5. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15010006

26. Alders, P, and Schut, FT. The 2015 long-term care reform in the Netherlands: getting the financial incentives right? Health Policy. (2019) 123:312–6. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2018.10.010

27. Chen, L, Zhang, L, and Xu, X. Review of evolution of the public long-term care insurance (LTCI) system in different countries: influence and challenge. BMC Health Serv Res. (2020) 20:1057. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05878-z

28. Nadash, P, Doty, P, and von Schwanenflügel, M. The German long-term care insurance program: evolution and recent developments. Gerontologist. (2018) 58:588–97. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnx018

29. Hayashi, M. Japan's long-term care policy for older people: the emergence of innovative "mobilisation" initiatives following the 2005 reforms. J Aging Stud. (2015) 33:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2015.02.004

30. Kim, H, Kwon, S, Yoon, NH, and Hyun, KR. Utilization of long-term care services under the public long-term care insurance program in Korea: implications of a subsidy policy. Health Policy. (2013) 111:166–74. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2013.04.009

31. Rhee, JC, Done, N, and Anderson, GF. Considering long-term care insurance for middle-income countries: comparing South Korea with Japan and Germany. Health Policy. (2015) 119:1319–29. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2015.06.001

32. Liu, H, and Hu, T. Evaluating the long-term care insurance policy from medical expenses and health security equity perspective: evidence from China. Arch Public Health. (2022) 80:3. doi: 10.1186/s13690-021-00761-7

33. Tang, Y, Chen, T, Zhao, Y, and Taghizadeh-Hesary, F. The impact of the long-term care insurance on the medical expenses and health status in China. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:847822. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.847822

34. Liu, H, Ma, J, and Zhao, L. Public long-term care insurance and consumption of elderly households: evidence from China. J Health Econ. (2023) 90:102759. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2023.102759

35. Cao, Y, Chen, H, and Yang, X. The impact of medical insurance on family financial support: evidence from Charls in China. Health Econ Rev. (2023) 13:39. doi: 10.1186/s13561-023-00452-9

36. Feng, J, Wang, Z, and Yu, Y. Does long-term care insurance reduce hospital utilization and medical expenditures? Evidence from China. Soc Sci Med. (2020) 258:113081. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113081

37. Strauss, J, Lei, X, Park, A, Shen, Y, Smith, JP, Yang, Z, et al. Health outcomes and socio-economic status among the elderly in Gansu and Zhejiang provinces, China: evidence from the Charls pilot. J Popul Ageing. (2010) 3:111–42. doi: 10.1007/s12062-011-9033-9

38. Chen, H, and Ning, J. The impacts of long-term care insurance on health care utilization and expenditure: evidence from China. Health Policy Plan. (2022) 37:717–27. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czac003

39. Lu, B, Mi, H, Yan, G, Lim, JG, and Feng, G. Substitutional effect of long-term care to hospital inpatient care? China Econ Rev. (2020) 62:101466. doi: 10.1016/j.chieco.2020.101466

40. Yang, S, Guo, D, Bi, S, and Chen, Y. The effect of Long-term care insurance on healthcare utilization of middle-aged and older adults: evidence from China health and retirement longitudinal study. Int J Equity Health. (2023) 22:228. doi: 10.1186/s12939-023-02042-x

41. Lei, X, Bai, C, Hong, J, and Liu, H. Long-term care insurance and the well-being of older adults and their families: evidence from China. Soc Sci Med. (2022) 296:114745. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114745

42. Zhou, JQ, Zhu, B, Yan, YH, Hou, LS, Wu, JH, Dong, BR, et al. Effect of china's Long-term care insurance on health outcomes of older disabled people: role of institutional care. Int J Qual Health Care. (2023) 35:mzad054. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzad054

43. Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security, China. Guidance on the development of a pilot long-term care insurance system. (2016). Available online at: https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2016-07/08/content_5089283.htm (Accessed February 25, 2025).

44. National Bureau of Statistics of China. Statistical Communiqué of the People's Republic of China on the 2023 National Economic and social development. (2024). Available online at: https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/zxfb/202402/t20240228_1947915.html (Accessed February 25, 2025).

45. Chengdu Human Resources and Social Security Bureau. Chengdu long-term care insurance system pilot program. (2017). Available online at: https://cdhrss.chengdu.gov.cn/cdrsj/uploads/20180523103526wwevlckni3l.pdf (Accessed February 25, 2025).

46. Shanghai Civil Affairs Bureau. Comprehensive statistical information on the elderly population, aging career and elderly Services in Shanghai. (2024). Available online at: https://mzj.sh.gov.cn/2024bsmz/20240706/73924c349f4d475a9d46b6019f1a396b.html (Accessed February 25, 2025).

47. National Bureau of Statistics of China. Communiqué of the Seventh National Population Census (No. 7). (2021). Available online at: https://www.stats.gov.cn/english/PressRelease/202105/t20210510_1817192.html (Accessed February 1, 2025).

48. Sichuan Provincial Healthcare Security Administration. Notice of the participation of provincial basic medical insurance participants in the pilot long-term care insurance system of Chengdu City. (2021). Available online at: https://ylbzj.sc.gov.cn/scsybj/nc040100/2021/2/2/5f81bb9b602145b79da921904a76e5c6.shtml (Accessed February 1, 2025).

49. ChengDu Healthcare Security Administration. Chengdu long-term care insurance implementation rules. (2022). Available online at: https://cdyb.chengdu.gov.cn/ylbzj/c128998/2022-06/16/658f5c90a0a04782830e64119fb4023b/files/094487d121a54dbf80f9501315bd8ef3.pdf (Accessed February 1, 2025).

50. Shanghai Municipal People’s Government. Shanghai long-term care insurance pilot measures. (2023). Available online at: https://www.shanghai.gov.cn/nw12344/20211231/d433625980cf4b8d8a4256e44d18622a.html (Accessed February 1, 2025).

51. Qingdao Municipal Government. Qingdao long-term care insurance pilot measures. (2021). Available online at: http://www.qingdao.gov.cn/zwgk/xxgk/ybj/gkml/gwfg/202103/t20210330_3034215.shtml (Accessed February 1, 2025).

52. Shanghai Municipal People’s Government. Shanghai long-term care insurance settlement measures (for trial implementation). (2018). Available online at: https://www.shanghai.gov.cn/gwk/search/content/fc9833ce9fe04d4f9d8ea49e30a784ec (Accessed February 1, 2025).

53. Qingdao Municipal Healthcare Security Bureau. Notice regarding concerns regarding the implementation of Qingdao’s long-term care insurance measures. (2021). Available online at: http://www.qingdao.gov.cn/zwgk/xxgk/ybj/gkml/gwfg/202103/t20210331_3035725.shtml (Accessed February 1, 2025).

54. National Healthcare Security Administration, China. Long-term care disability rating assessment criteria (trial). (2021). Available online at: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2021-08/06/content_5629937.htm (Accessed February 1, 2025).

55. Chengdu Human Resources and Social Security Bureau. Chengdu long-term care insurance disability care service items and standards (dementia). (2018). Available online at: https://cdhrss.chengdu.gov.cn/cdrsj/c109727/2019-01/08/content_9be6a0e77e8f4541a71f065332f66a94.shtml (Accessed February 1, 2025).

56. Qingdao Municipal Healthcare Security Bureau. Qingdao long-term care insurance disability and dementia rating assessment work regulations. (2024). Available online at: http://www.qingdao.gov.cn/zwgk/xxgk/ybj/gkml/gwfg/202408/t20240801_8159142.shtml (Accessed February 1, 2025).

57. Shanghai Municipal Bureau of Civil Affairs. Shanghai uniform needs assessment standards for elderly care (trial) version 2.0. (2019). Available online at: https://www.shanghai.gov.cn/zhfwzfbzsjzc/20230418/b0bc8649f8d74973a45ec60bce219ab2.html (Accessed February 1, 2025).

58. ChengDu Healthcare Security Administration. Long-term care insurance for urban workers: service items and payment standards. (2018). Available online at: https://cdyb.chengdu.gov.cn/ylbzj/c128998/2020-05/27/content_ad3b2ccaecd44f058cb1fde2537fdb88.shtml (Accessed February 1, 2025).

59. Qingdao Municipal Bureau of Human Resources and Social Security. Qingdao long-term care insurance designated nursing service organization agreement management measures. (2018). Available online at: http://www.qingdao.gov.cn/zwgk/xxgk/rlshbz/gkml/zcjd/202010/t20201017_356391.shtml (Accessed February 1, 2025).

60. Qingdao Municipal Healthcare Security Bureau. Qingdao long-term care insurance designated nursing facility assessment and implementation plan (trial). (2023). Available online at: http://www.qingdao.gov.cn/zwgk/xxgk/ybj/gkml/gwfg/202307/t20230705_7276839.shtml (Accessed February 1, 2025).

61. Shanghai Municipal People’s Government. Shanghai long-term care insurance designated care service institution management measures (trial). (2023). Available online at: https://www.shanghai.gov.cn/gwk/search/content/c5b1ca97ce164633970e2983084b7ba1 (Accessed February 1, 2025).

62. ChengDu Healthcare Security Administration. Management measures for designated service institutions of Chengdu long-term care insurance. (2022). Available online at: https://cdyb.chengdu.gov.cn/gkml/xzgfxwj/1660544782516117505.shtml (Accessed February 1, 2025).

63. ChengDu Healthcare Security Administration. Administrative measures for standardized training of home care service personnel of Chengdu long-term care insurance (2022). Available online at: https://cdyb.chengdu.gov.cn/gkml/uploadfiles/070369020201/2022083014330296.pdf (Accessed February 1, 2025).

64. Qingdao Municipal Healthcare Security Bureau. Qingdao municipal bureau of medical security notice on vocational skills training for long-term care insurance caregivers. (2021). Available online at: http://www.qingdao.gov.cn/zwgk/xxgk/ybj/gkml/gwfg/202210/t20221010_6440706.shtml (Accessed February 1, 2025).

65. Shanghai Civil Affairs Bureau. Implementation opinions on accelerating the construction of Shanghai’s elderly care workforce. (2017). Available online at: https://mzj.sh.gov.cn/MZ_zhuzhan279_0-2-8-15-55-231/20200519/MZ_zhuzhan279_43811.html (Accessed February 1, 2025).

66. Hongkou District Civil Affairs Bureau. Opinions on accelerating the construction of elder care personnel teams in Hongkou District. (2017). Available online at: https://www.shhk.gov.cn/hkxxgk/showinfo.html?infoGuid=f1d5b6c7-06c1-4c87-b583-19512a63d74a (Accessed February 1, 2025).

67. Zhong Yu-ying, CJ. A comparative study of commercial insurance institutions participating in long-term care insurance: an analysis of Haidian District in Beijing and Qingdao in Shandong Province. Chinese J. Health Policy. (2018) 11:24–8. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-2982.2018.04.005

68. Hu Hongwei, GX. The German nursing security system: evolution, structural adjustment, evaluation, and insights from a system relationship perspective. Compar Econ Soc Syst. (2023) 5:177–87. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1003-3947.2023.05.018

69. Zhao Jiuyang, GK. Study on the influencing factors of Chinese medical insurance fund development: based on provincial panel data. Manag Rev. (2023) 35:71–84. doi: 10.14120/j.cnki.cn11-5057/f.20220530.002

70. Yong, T. The study on the financial burden capacity of long-term care insurance in China—a discussion on the rationality of long-term care insurance system based on medical insurance. Soc Sec Stud. (2020) 1:33–47. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-4802.2020.01.004

71. Chengdu Municipal Statistics Bureau. Statistical bulletin on National Economic and social development of Chengdu City, 2017. (2018). Available online at: https://cdstats.chengdu.gov.cn/cdstjj/c154795/2018-05/15/content_d34bb4a4dbc34257ac32f2c294ffe7e4.shtml.

72. Chengdu Municipal Statistics Bureau. Statistical bulletin on National Economic and social development of Chengdu City, 2019. (2020). Available online at: https://cdstats.chengdu.gov.cn/cdstjj/c154795/2020-03/28/content_dc66717c17064757b7b3372695f775ad.shtml (Accessed February 1, 2025).

73. Chengdu Municipal Statistics Bureau. Statistical bulletin on National Economic and social development of Chengdu City, 2021. (2022). Available online at: https://cdstats.chengdu.gov.cn/cdstjj/c154795/2022-03/25/content_f4c79d6ef64a4fe994a335102a860b6b.shtml (Accessed February 1, 2025).

74. Qingdao Municipal Finance Bureau. 2021 Qingdao medical protection bureau departmental accounts. (2022). Available online at: http://qdcz.qingdao.gov.cn/zfxxgk/fdzdgknr/czysjs/bmczyjs_yjs/2022/czyjs2022_71/czjs_2022/t_7396137.shtml (Accessed February 1, 2025).

75. Qingdao Municipal Healthcare Security Bureaun. Qingdao municipal health protection bureau 2021 work summary. (2021). Available online at: http://www.qingdao.gov.cn/zwgk/xxgk/ybj/gkml/ghjh/202201/t20220110_4192682.shtml (Accessed February 1, 2025).

76. Shanghai Municipal Bureau of Finance. Shanghai citywide and municipal financial accounts 2021. (2022). Available online at: https://czj.sh.gov.cn/zys_8908/czsj_9054/zfyjs/yjsbg_9056/20220902/7f8316dd51c44da488c2bfa7bc62e245.html (Accessed February 1, 2025).

77. Fangtao, L, and Qing, F. A research on the scale of long-term care insurance demand and the security path in China—based on the data of the seventh population census. Insurance Stud. (2023) 3:59–69. doi: 10.13497/j.cnki.is.2023.03.005

78. National Health Commission, China. 2020 National bulletin on aging. (2021). Available online at: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/cms-search/xxgk/getManuscriptXxgk.htm?id=c794a6b1a2084964a7ef45f69bef5423 (Accessed February 1, 2025).

79. Ministry of Civil Affairs, China. Specifications of post setting and staffing for senior care organization. (2021). Available online at: https://www.mca.gov.cn/gdnps/n2445/n2575/n2580/n2582/n2590/c117044/attr/273014pdf (Accessed February 1, 2025).

80. Baker, C, Cary, AH, and da Conceicao, BM. Global standards for professional nursing education: the time is now. J Prof Nurs. (2021) 37:86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2020.10.001

81. Ruiming, D, Shiying, H, Man, J, Ying, W, Ge, B, and Li, L. Study on the importance of information system in the supervision of long-term care insurance. Health Dev Policy Res. (2019) 22:35–37+42. doi: 10.13688/j.cnki.chr.2019.18282

82. Swiss Re Institute. Private long-term care insurance opportunities in China. (2022). Available online at: https://www.swissre.com/institute/research/topics-and-risk-dialogues/china/long-term-care-insurance-china.html (Accessed February 1, 2025).

83. Yang, H, Fan, W, and Jiang, W. Estimation of the financing burden of Long-term care insurance funds: comparative analysis based on 8 Ltc insurance pilot regions. Chinese J Health Policy. (2023) 16:1–9. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-2982.2023.06.001

84. Zhang, N. A visual analysis of the research on the funding mechanism of long-term care insurance in China—based on CiteSpace. Operations Res. Fuzziol. (2023) 13:2487–96. doi: 10.12677/ORF.2023.133249

85. Kapil, S. Number of long-term care beds by county correlates with caregiver burden. J Am Med Dir Assoc. (2018) 19:B28–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.12.085

86. National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. National Nursing Career Development Plan (2021-2025). Chinese Nurs Manag. (2022) 22:801–4. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-1756.2022.06.001

87. Huynh, NTT, Le, TD, Hapsari, HI, Hsiao, HT, Huang, MC, and Kao, CY. The experiences of migrant care workers in long-term care facilities: a scoping review. J Immigr Minor Health. (2024) 26:936–44. doi: 10.1007/s10903-024-01618-1

88. Fudan Institute on Ageing. Long-term care insurance study. (2021). Available online at: http://aging.fudan.edu.cn/contents/33/205.html (Accessed February 1, 2025).

Keywords: long-term care insurance, geriatric services, policy analysis, population aging, cross-sectional study

Citation: Du K, Liu Y and Hu Y (2025) Evaluation of long-term care insurance pilot city policies in China: a cross-sectional study. Front. Public Health. 13:1570794. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1570794

Received: 04 February 2025; Accepted: 10 March 2025;

Published: 21 March 2025.

Edited by:

Marios Kyriazis, National Gerontology Centre, CyprusReviewed by:

Lijun Zeng, Sichuan University, ChinaCopyright © 2025 Du, Liu and Hu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yiran Hu, bm11X2h1eWlyYW5AMTI2LmNvbQ==

†These authors share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.