- 1Department of Biosciences, University College London, London, United Kingdom

- 2Department of Arts and Sciences, University College London, London, United Kingdom

- 3The Culture, Health and Wellbeing Alliance CIC, Barnsley, United Kingdom

Depending on environmental and social determinants, planetary health impacts unequally on human health. As it is likely that creativity and culture are under-tapped resources, the potential to address community and environmental issues to tackle health inequalities, especially those resulting from climate injustice, has not yet been fully realized. The study aimed to identify common features of environmentally and socially engaged UK community programs addressing the intersecting challenges of planetary and human health. A short survey was used to screen participants for in-depth semi-structured interviews. Inclusion criteria comprised adult practitioners offering environmentally and socially engaged community programs of creative and cultural activities leading to health and environmental outcomes. Thematic analysis of 19 surveys and eight interviews identified 146 responses, from which 12 themes with 98 subthemes were derived. Seventy per cent of responses were distributed across five major themes: ‘Collaboration and partnerships’, ‘Community health and wellbeing’, ‘Connection to nature’, ‘Funding’ and ‘Mental health’. Within these five themes, 10 subthemes which resulted from three or more similar responses by different participants were deemed common features of community programs. Two of the 10 subthemes: ‘Connection to nature in children’ and ‘Relationship with natural world’ within the major theme: ‘Connection to nature’ addressed planetary and human health directly through practices recognizing environmental and human interdependency. Four of the 10 subthemes: ‘Influencing wider systems’ within the major theme ‘Collaboration and partnerships’; and ‘Looking after our staff’, ‘Preventative measures’ and ‘Research evidence’ within the major theme ‘Mental health’; addressed planetary and human health indirectly through practitioner partnership influence over policies relating to climate change and by addressing concern for the environment manifesting in eco-anxiety. The study indicates the need for inclusive practice, partnership work, and sustainable funding that can support practitioner wellbeing and the process, outputs and impacts of natural and sustainable environment-based health interventions and other resources instrumental in preventative healthcare.

1 Introduction

Human and planetary health are “inextricably linked” [(1), p. 1] and “mutually reliant” [(2), p. 1], consequently, the “need to focus on creating healthy societies on a healthy planet” is becoming increasingly apparent [(1), p. 1]. The United Kingdom Research and Innovation (UKRI) Planetary Health Network has agreed a working definition of ‘planetary health’ based on that of the Rockefeller Foundation–Lancet Commission on Planetary Health (3), which “focuses on the health impacts (in humans, animals, and plants) of human-caused disruptions of Earth’s natural systems and the development and evaluation of potential actions to create positive feedback loops between a healthy environment and a healthy society” [(4), p. 2]. Ill health and premature death, for example, have been associated with pollution (5). Planetary health has been described as a “solutions-oriented, transdisciplinary field and social movement” that seeks to address such disruptions to Earth’s natural systems [(6), p. 1]. Planetary health is therefore premised on the idea that the wellbeing of humanity and the earth are interdependent, and a sustainable world is one in which “the earth thrives and people can pursue flourishing lives” [(7), p. 3].

The notion of planetary health arose from environmental movements of the 1970s and 1980s (8). In 1980, for example, Friends of the Earth, extended the World Health Organization (WHO) definition of health– “a state of complete physical, mental and social wellbeing” [(9), p. 1]—“a state of complete physical, mental, social and ecological well-being—personal health involves planetary health” [(10), p. 9]. Since the Rockefeller Foundation-Lancet Commission (3), this concept has been increasingly mainstreamed in clinical literature (8). The Commission determined that “human civilization… now risks substantial health effects from the degradation of nature’s life support systems in the future… driven by highly inequitable, inefficient, and unsustainable patterns of resource consumption and technological development, together with population growth” [(3), p. 1973]. A recent review of health inequalities in the UK further states that “economic growth without attending to its environmental impact… is not an option for the country or for the planet” [(11), p. 18]. Sustainability and wellbeing are both central to the ‘planetary boundaries’ framework [(12), p. 1], which describes the environmental limits in which humans can safely operate “without endangering the vitality of the ecosystems” [(13), p. 169].

Allied to planetary health are older concepts of ‘one health’ (14) and ‘holistic health’ (15). The one health approach has been described as a multi-disciplinary effort at local, national, and global levels “to attain optimal health for people, animals, and our environment” [(16), p. 3]. It gained traction in response to serious zoonotic disease outbreaks (17)—and has been endorsed by international agencies including the WHO, World Organization for Animal Health, and United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (14). The holistic health approach focuses largely on non-medical treatments—often described as complementary or alternative—and, akin to the WHO definition of health, can be expressed as “complete or total patient care that considers the physical, emotional, social, economic, and spiritual needs of the person” [(15), p. 1935]. The environmental component of one health and holistic health may have been comparatively neglected, however (17). Consequently, recent research has aimed to rebalance the emphasis on the health of people, animals, and ecosystems while recognizing their interdependence (18), and suggests that a one health approach could be applied at community, regional, national, and global scales (19).

Depending on the environmental and social determinants of health—i.e., “the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age and inequities in power, money and resources” [(20), p. 5]—planetary health impacts unequally on human health. The concept of ‘climate injustice’, moreover, speaks to the fact that while poorer nations have contributed far less to climate change, they are likely to suffer disproportionately from its effects (21). The Marmot review into health inequalities avers that “tackling social inequalities in health and tackling climate change must go together” [(11), p. 15]; moreover, that environmental stability “should be a more important societal goal than simply more economic growth” [(11), p. 18]. Yet the WHO Commission reports that health is not prioritized in environmental policies (5). Furthermore, adaptation to climate change means “we must do things differently” and “creating a sustainable future is entirely compatible with action to reduce health inequalities” [(11), p. 18]. Others have argued for shifting the center of our definition of socially determined health: to “for too long, humans alone have been the focus… and it is time to clearly acknowledge and define the determinants of planetary health in a more eco-centric way” [(22), p. E111].

Health inequalities are defined by the NHS as “unfair and avoidable differences in health across the population, and between different groups within society” [(23), p. 1]. Their consequences might include differences in length of life, health conditions and access to care (23). In a study aiming to determine priority areas for future research into inequalities in the UK and methods by which they might be addressed, participants identified health, social care, living standards and economic factors as key areas of inequality which were interconnected and needed to be addressed together “through tackling societal and structural inequalities, chiefly environmental conditions and housing, and having an active prevention program” [(24), p. 11]. According to the Institute of Health Equity, in the period prior to COVID-19 (2011–2019), 890,000 people died earlier in the most deprived quintile of England (11), with some areas of inequality widening during COVID-19 (20, 24).

A significant body of evidence, however, highlights the potential of community assets, such as museums, libraries, galleries, parks and natural heritage, to tackle health inequalities (25). For example, a review of the work of charities, freelance creative practitioners, social enterprises and local authority museums offering online workshops, pre-recorded performances, activity packs, and co-produced exhibitions or artwork during COVID-19, found their intended outcomes included improving institutional wellbeing, tackling loneliness and isolation, and supporting social or family connections (26). A further review of the social impact of music-making interventions showed that intended outcomes covered “areas of wellbeing, inclusion, confidence, empowerment, and co-operation” [(27), p. 117]. It is increasingly acknowledged that public health challenges cannot be undertaken entirely by existing healthcare systems, and practices outside of health might make a greater contribution to population health outcomes than the health sector itself (28). One such practice with potential to influence population health is ‘creative health’ which has developed in part from the broader field of ‘participatory art’ (29). At the roots of participatory art lie a challenge to professional and theoretical silos connecting “art, social work, politics, philosophy, environmentalism, therapy, community development, activism, health, esthetics, social justice and many other fields” [(29), p. 26].

The All-party Parliamentary Group on Arts, Health and Wellbeing (APPGAHW) inquiry report was among the first publications to use ‘creative health’ as an umbrella term for a multitude of creative and cultural practices, and to draw attention to the policy implications of the role of creativity in health and wellbeing (30). The report asserted that “the arts can help meet major challenges facing health and social care” and, in referencing more than a thousand creative projects and research studies, illustrated the impact of creativity and culture on health and wellbeing [(30), p. 154]. Creative health activities include “visual and performing arts, crafts, film, literature, cooking and creative activities in nature, such as gardening” [(31), p. 10].

In addition to arts practices, researchers have found a “significant amount of natural environment-based health intervention activity,” which suggest health outcomes could be improved through, for example “good quality urban greenspace interventions” [(32), p. 81]. Briefings focused on the benefits of exposure to natural environments show evidence of “physical, social, cognitive and emotional development” for children and young people [(33), p. 10–11] and a correlation of connection to nature with “pro-environmental and pro-conservation behavior and wellbeing” [(34), p. 9]. Analysis of data from two surveys assessing the impact of culture-, health- and nature-based engagement on mitigating the adverse effects of public health restrictions during COVID-19 showed that over four fifths of adult respondents participated in activities more often than before the pandemic (35). Although the highest frequency of response was for sport and fitness, other activities in the upper quartile included cooking or baking; crafts, textiles, and decorative arts; gardening or looking after plants; and painting, drawing, printmaking, and sculpture. The authors concluded that engagement with culture, health, and nature-based activities “appeared to improve psychological wellbeing, reduce loneliness and engender feelings of social connectedness” [(35), p. 18].

Recently, a new Creative Health Quality Framework, co-produced with practitioners, recognizes the diversity of creative health practice and recommends that good practice should follow eight principles: person-centered, equitable, safe, creative, collaborative, realistic, reflective, and sustainable. ‘Sustainable’ in this context is defined as, working toward “a positive, long-term legacy for people and planet” [(36), p. 7]. Expanding upon the Creative Health Quality Framework recommendations, the current research aimed to identify the common features of environmentally and socially engaged community programs, specifically those addressing the intersecting challenges of planetary and human health, through analysis of surveys and interviews with creative health practitioners.

2 Methods

2.1 Design

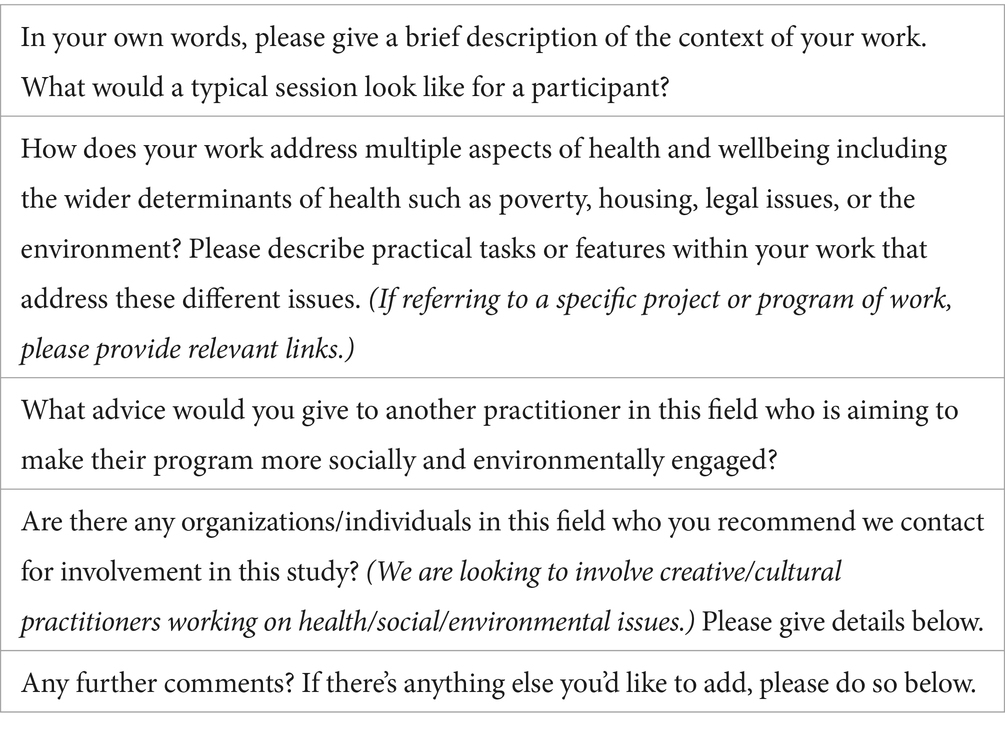

The qualitative study consisted of an online survey and in-depth interview. The survey comprised five open-ended question requiring brief responses (Table 1). Interviews comprised nine open-ended semi-structured questions under six categories (Table 2). Survey and transcribed interview data were analyzed using deductive thematic analysis informed by an interpretivist epistemological perspective using constructivist research methods. Thematic analysis was conducted in NVivo 1.7 and descriptive statistics in IBM SPSS 28.

2.2 Participants

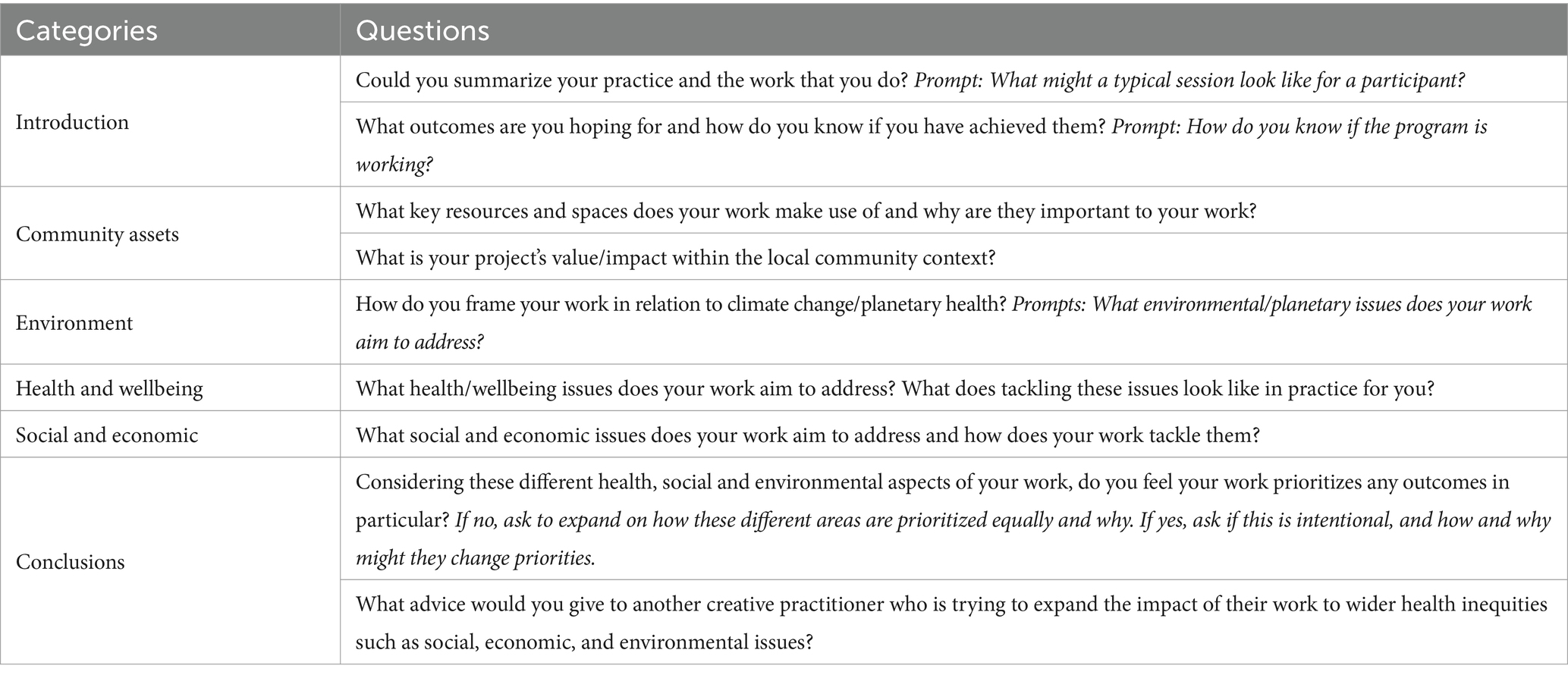

Participants were recruited for the survey using purposive and snowball sampling where organizations were contacted to make referrals and survey respondents recommended other individuals. Inclusion criteria comprised adult practitioners working in the UK offering environmentally and socially engaged community programs that involved creative and cultural activities leading to health and environmental outcomes. Of 43 potential participants identified through 73 organizations, 19 practitioners (7 employees, 12 freelancers; 16 females, 3 males) completed the survey. Of these, 15 indicated a willingness to be interviewed and eight (4 employees, 4 freelancers; 7 females, 1 male) met the inclusion criteria. Reasons for exclusion involved interest but lack of practice in the research topic. Participants were paid £50 for taking part in the interview.

2.3 Materials

Materials comprised a privacy statement; participant information sheet; consent form; an online survey and online interview protocol.

2.4 Procedure

Low risk ethical approval was obtained for the study. Libraries, museums, galleries, heritage sites, gardens, and mailing list subscribers across the UK, contacted through CHWA, London Arts and Health, Happy Museum Project and Culture Declares Emergency, were sent recruitment emails containing project information and a survey link. The survey was conducted over 3 months (April–June 2023) using Qualtrics and took 10–15 min to complete. After the survey, participants were asked if they would like to take part in a one-to-one follow-up interview. For those who agreed, responses were screened for fit with inclusion criteria. Approximately 1 month after survey completion, interviews of c.60 min were conducted in Microsoft Teams over 2 months (May–June 2023).

3 Results

3.1 Question 1: Could you summarize your practice and the work that you do?

Responses to Question 1 were tabulated with practitioner quotations to illustrate their work (Table 3).

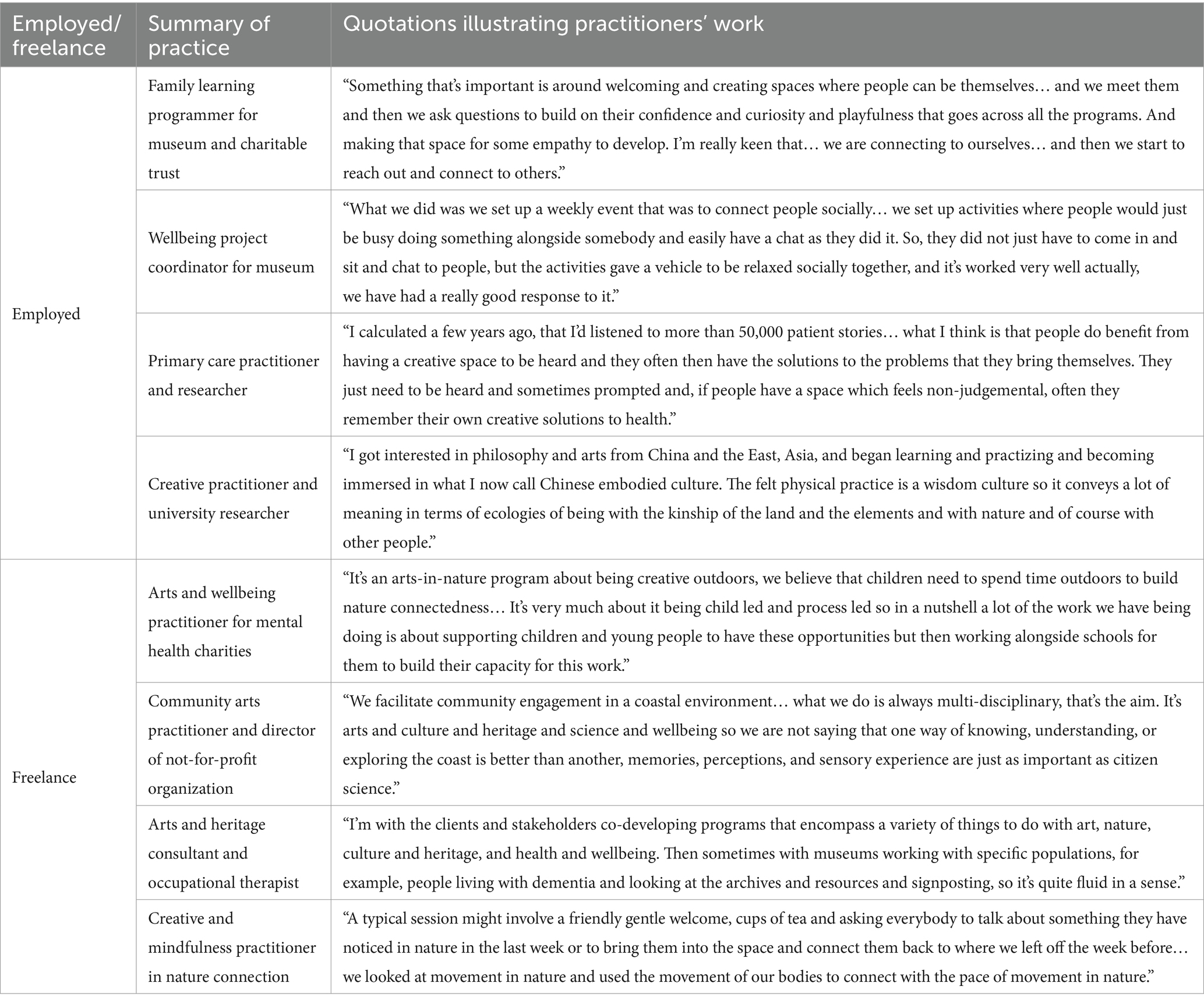

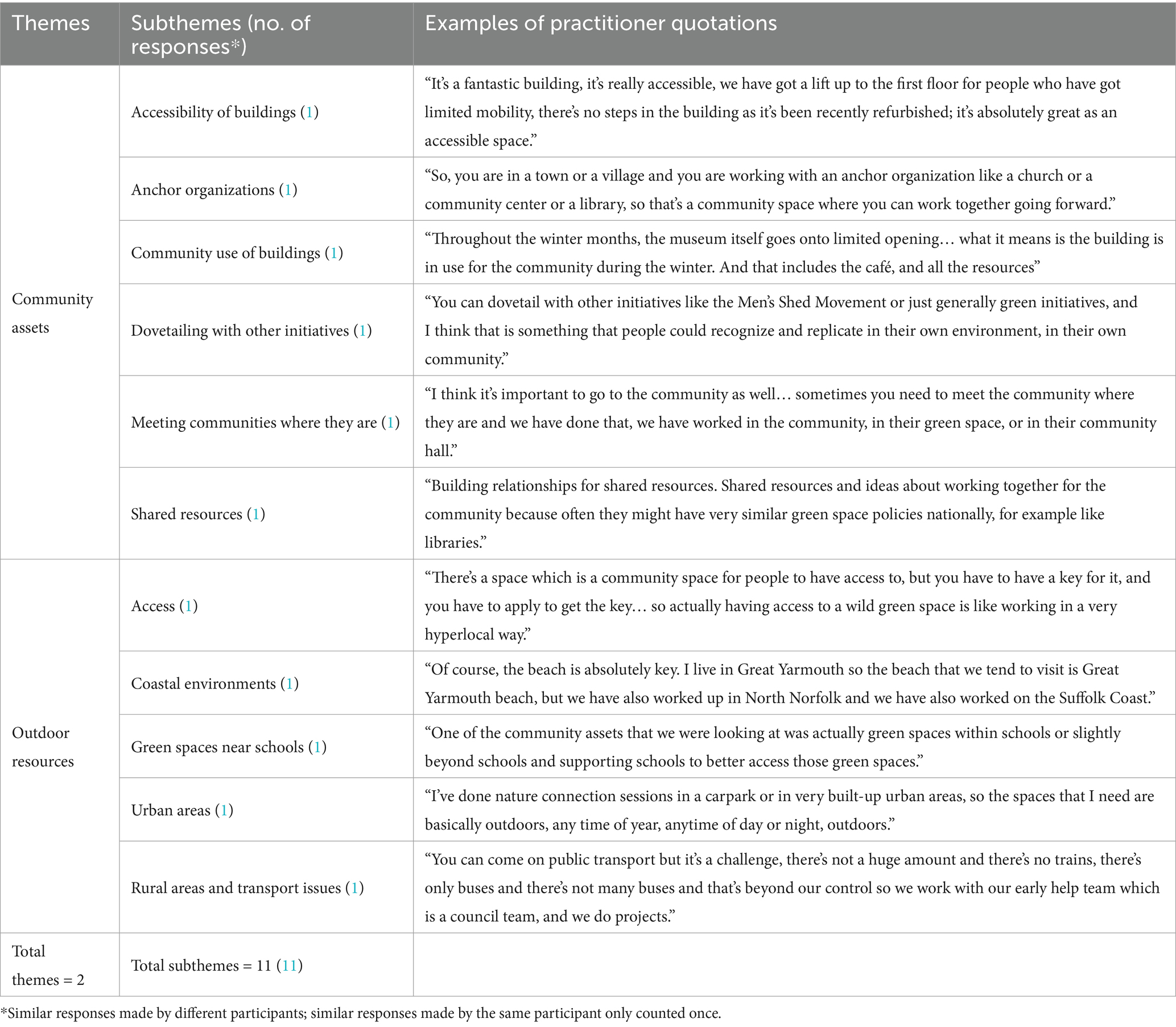

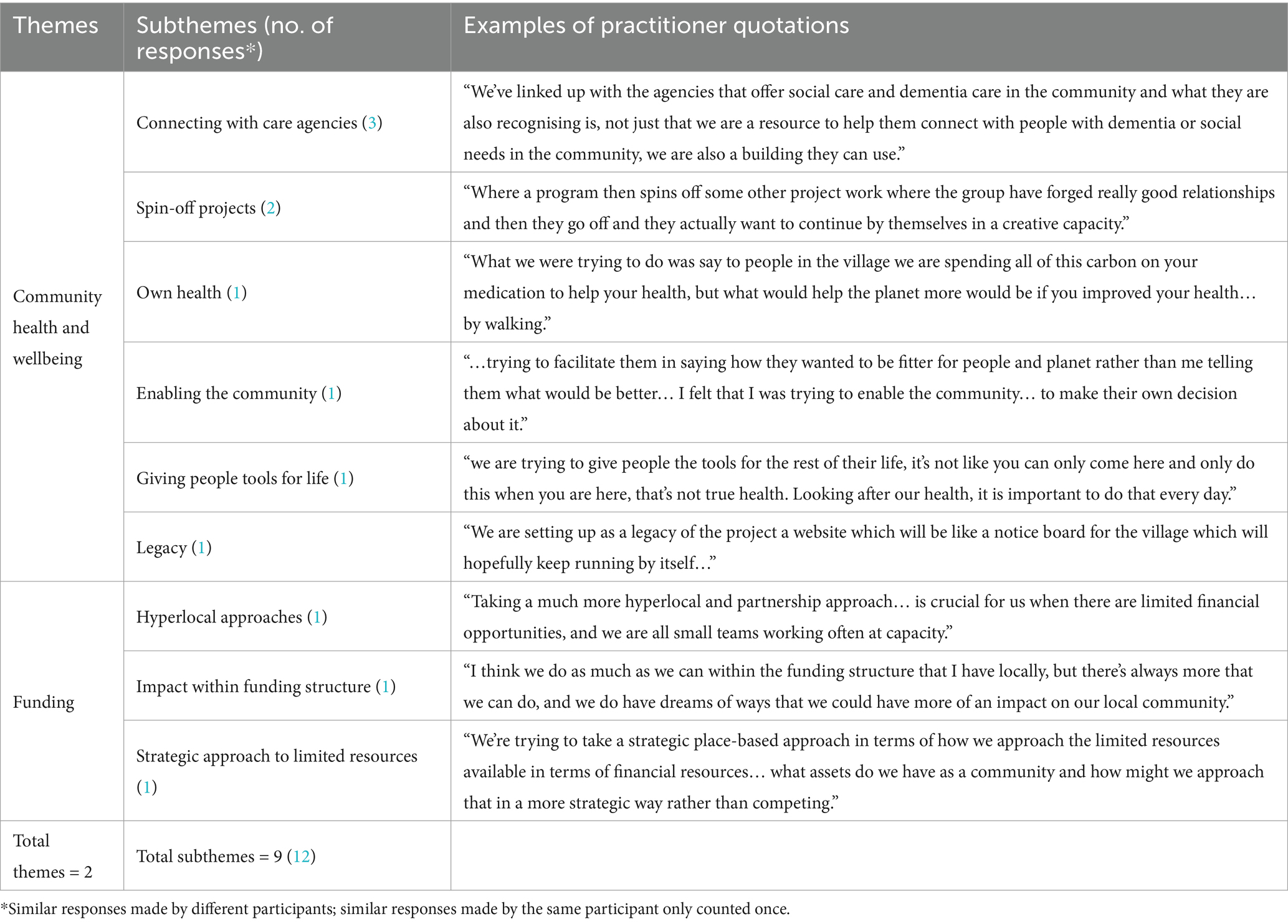

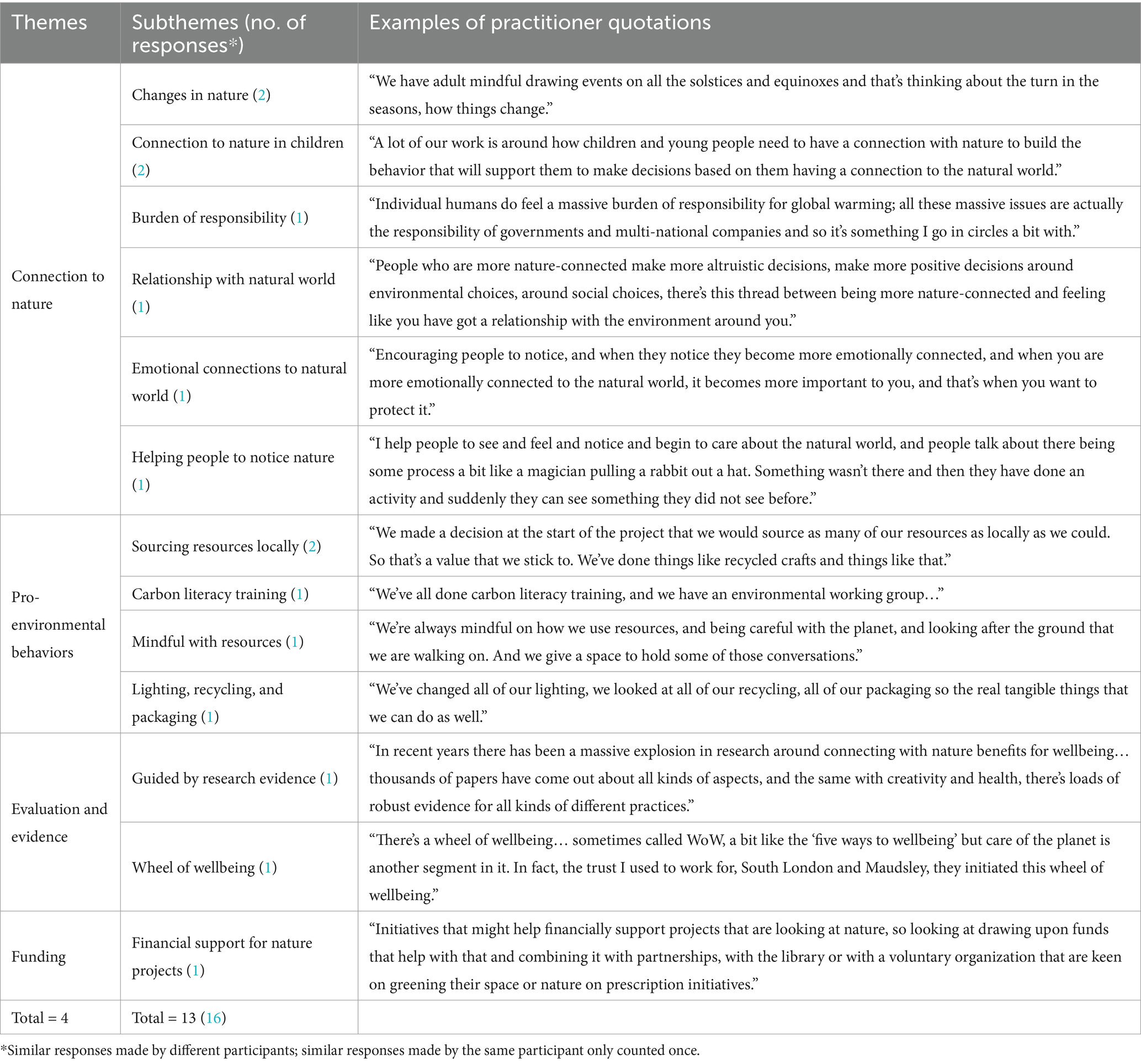

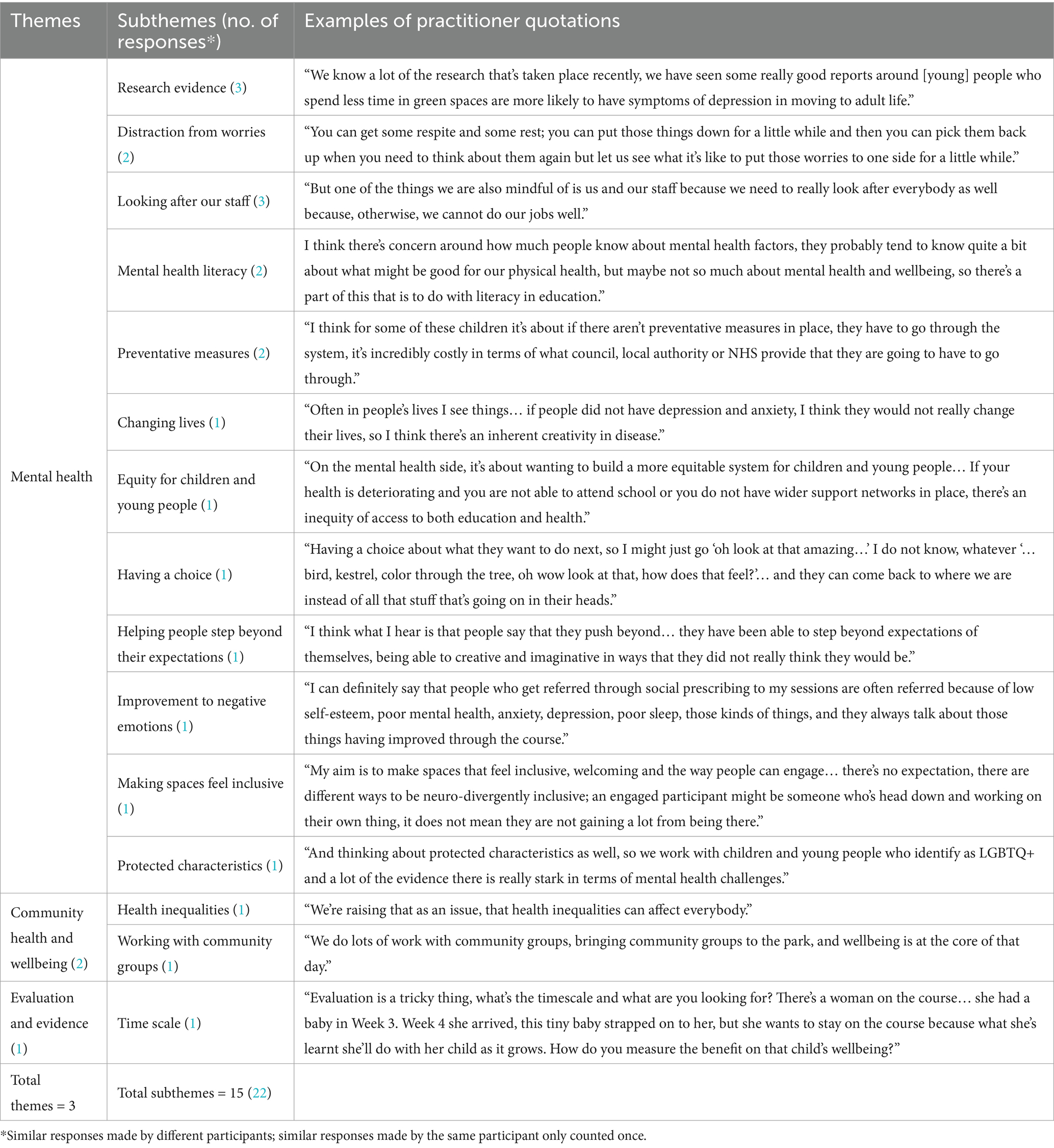

For data from Questions 2–9, 12 themes were identified from 98 subthemes derived from 146 responses, mean number of responses per theme = 12.17 (median = 9; range = 19) and mean number of subthemes per theme = 8.17 (median = 7; range = 11). Five themes, with the number of responses above the mean with just under 70 per cent (69.18%) of all responses were regarded as major themes: ‘Community health and wellbeing’; ‘Mental health’; ‘Collaboration and partnership’; ‘Connection to nature’; and ‘Funding’. Seven themes with the number of responses below the mean were regarded as minor themes: ‘Community assets’; ‘Developing a practice’; ‘Tackling poverty’; ‘Equal importance of priorities’, ‘Evaluation and evidence’; ‘Outdoor resources’; and ‘Pro-environmental behaviors’ (Figure 1).

3.2 Question 2: What outcomes are you hoping for and how do you know if you have achieved them?

Five major and two minor themes were derived in response to this question (Table 4). Within ‘Community health and wellbeing’, these outcomes included supporting isolated and lonely people, creating a sense of safety and being welcome, connecting people, and practitioners looking after their own health as the first step. Practitioners determined whether outcomes were achieved by looking at attendance numbers and regularity, whether people felt safe, welcome and confident, and by using wellbeing frameworks such as the Community Spirit Framework. Within ‘Collaboration and partnerships’, intended outcomes involved trust, building networks, integrating with other initiatives, and sharing experiences. Practitioners determined whether outcomes were achieved by assessing whether participants were able to collaborate and co-produce across the sector and influence the wider systems. Within ‘Connection to nature’, the intended outcome was to connect with nature, respect nature and appreciate they were part of nature. They felt it was important for children and young people to access green spaces and for connection to nature to be built into school curricula, though the only outcome measure was to assess whether this connection had occurred long-term. Within ‘Mental health’, practitioners spoke about the impact of environmental concerns on mental health, but also the need to change the mental health system and move toward a model that was closer to their own creative approach, emphasizing prevention and the reduction of escalation. They discussed the need for better and quicker access to mental health services, and for services co-produced with children and young people who might themselves offer ideas about the support they required. Within the minor themes of ‘Community assets’ and ‘Evaluation and evidence’, participants stressed the importance of equitable access to community assets that might determine health; and said that evaluation should be “meaningful” and used as a “reflective tool.”

3.3 Question 3: What key resources and spaces does your work make use of and why are they important to your work?

Responses to the question involved two minor themes (Table 5). Within ‘Community assets’, buildings needed to be accessible and offer warm space/hot meals during the winter. Practices involved “dovetailing with other initiatives” and working with anchor organizations, ideally having similar green policies, with a view to sharing resources. It was felt important to meet communities “where they are.” Within ‘Outdoor resources’, practitioners used green and blue, and rural and urban spaces. These resources were vital to some practitioners, but they faced challenges in applying for access to council-owned outdoor spaces and overcoming public transport issues in rural areas.

3.4 Question 4: What is your project’s value/impact within the local community context?

Responses to the question involved two major themes (Table 6). The first was ‘Community health and wellbeing’ whereby practitioner offered resources to care agencies working in the community and, also helped people develop tools to support their health “for the rest of their life” while encouraging ‘spin-off projects’ that could continue. Within ‘Funding’, practitioners felt additional funding would allow them to do more to impact the local community—while noting that strategic, hyperlocal and partnership approaches maximized value for money.

3.5 Question 5: How do you frame your work in relation to climate change/planetary health?

Responses to the question incorporated two major and two minor themes (Table 7). In ‘Connection to nature’, practitioners encouraged participants to consider how changes in nature—weather and seasons, for example—might relate to their own lives/ Practitioners felt it was critical to help people, especially children and young people, notice the natural world to become more emotionally connected with it and therefore to care about it. Practitioners suggested that they were guided by research evidencing the beneficial effects of nature on wellbeing, and associated connection to nature with altruistic and positive environmental and social choices. They also noted, however, that individuals felt a “massive burden of responsibility” for global warming, despite this being more realistically the responsibility of governments and multi-national companies. Within ‘Funding’, one practitioner suggested funders could prioritize projects concerned with nature and embedded in local partnership. For minor themes, ‘Pro-environmental behavior’ included being “mindful” about resources such as lighting, packaging and recycling, and buying locally—with one practitioner explaining how their organization had taken part in carbon literacy training and set up an environmental working group. Within ‘Evidence and evaluation’, one practitioner suggesting there was “lots of robust evidence” on access to nature and pro-environmental behaviors, and creativity and health. Another referred to the Wheel of Wellbeing, a measure including care for the planet.

3.6 Question 6: What health/wellbeing issues does your work aim to address? What does tackling these issues look like in practice for you?

Responses to the question consisted of two major themes and one minor theme (Table 8). ‘Mental health’ incorporated the majority of responses to this question. Here, practitioners looked to research evidence, as with Question 5, citing that less time in green spaces was associated with a greater incidence of depression. Practitioners advocated interventions where participants were distracted from other concerns and encouraged to put their “worries to one side for a little while.” They felt that negative emotions would reduce through their interventions. Practitioners reported helping people who were lonely and isolated to reconnect, making spaces feel inclusive, giving their participants choices. They thought there should be preventative measures and a more equitable mental health system for children and young people, with ‘mental health literacy’ included in education; they pointed to evidence of the particular challenges experienced by people with protected characteristics. Practitioners also considered it important to look after themselves and their staff, pointing out the risk of stress associated with working mental health. Within ‘Community health and wellbeing’, practitioners spoke about the need to work with community groups, in one case saying that health inequalities can “affect everybody.” Within ‘Evaluation and evidence’, one practitioner explained that project timescales, and the challenge of knowing what to look for, made it “tricky” to assess wellbeing.

3.7 Question 7: What social and economic issues does your work aim to address and how does your work tackle them?

Responses to the question involved the major theme of ‘Funding’ and minor theme of ‘Tackling poverty’ (Table 9). Within ‘Funding’, practitioners stressed the importance of moving toward sustainable, long-term funding models. This would support respectful and timely payment for practitioners (and in some cases participants), project sustainability, and the development of a stronger evidence base. They also spoke about the “catalyst effect” whereby through increasing their knowledge and skills, community partners might develop the potential to apply for their own funding to sustain projects. Within ‘Tackling poverty’, practitioners noted that their activities were offered for free, and they were consciously working to support people to attend. Additionally, one practitioner suggested that the pro-environmental behaviors fostered by their work might also alleviate cost-of-living challenges, for example encouraging a culture of walking to school rather than driving.

3.8 Question 8: Considering these different health, social and environmental aspects of your work, do you feel your work prioritizes any outcomes in particular?

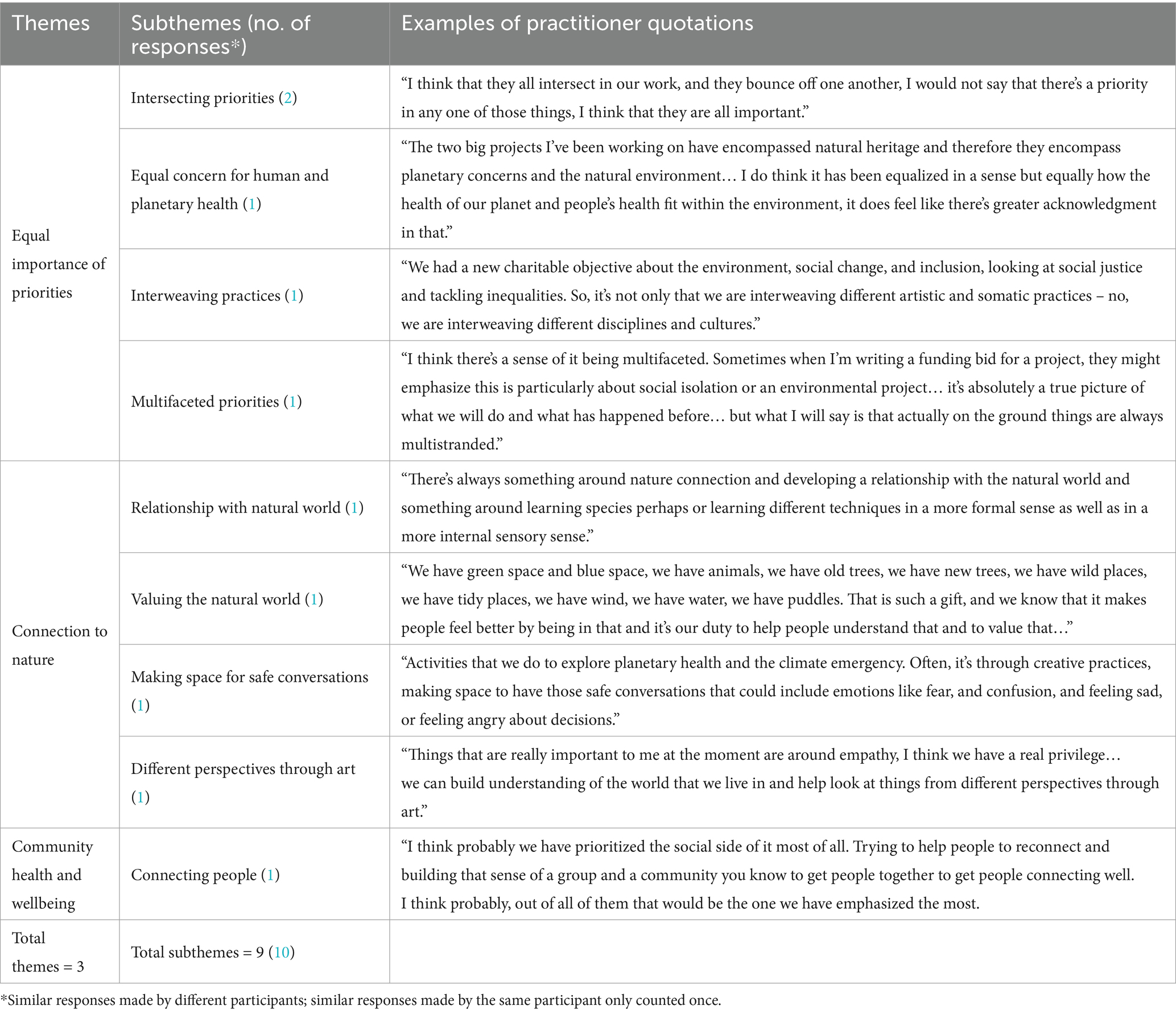

Responses to the question produced one major and two minor themes (Table 10). Within ‘Equal importance or priorities’, most practitioners felt that the health, social and environmental aspects of their work were of equal importance. They saw these priorities as “intersecting,” “interweaving” and “multifaceted.” ‘Connection to nature’ included developing a relationship with and understanding and valuing the natural world and using art-making to foster empathy for different perspectives. Within ‘Community health and wellbeing’, one practitioner prioritized “the social side” with a view to building a sense of group and community “to get people together.”

3.9 Question 9: What advice would you give to another creative practitioner who is trying to expand the impact of their work to wider health inequities such as social, economic, and environmental issues?

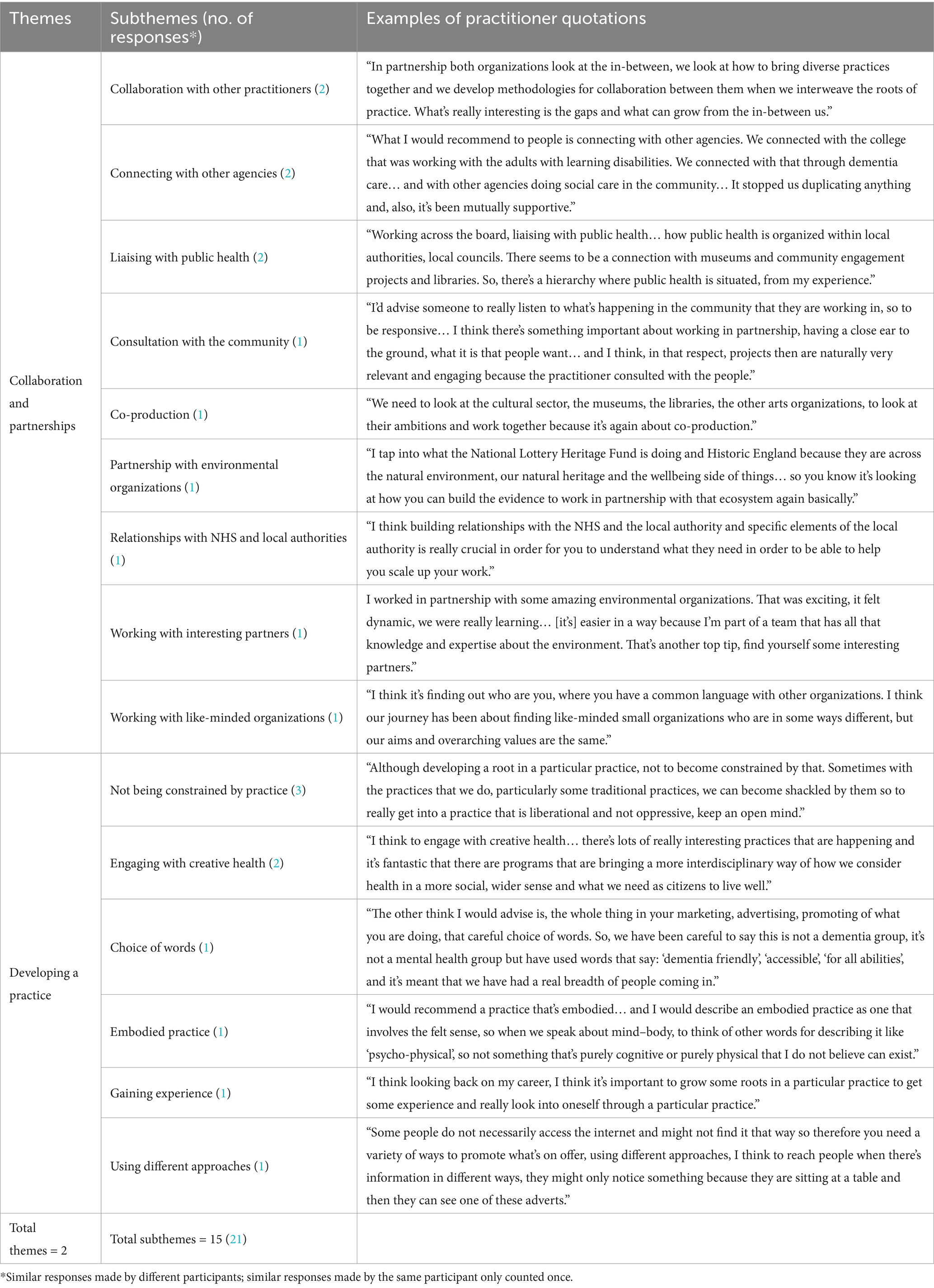

Responses to the question involved one major and two minor themes (Table 11). Within ‘Collaboration and partnerships’, collaborating with other practitioners was seen as essential, particularly “interesting partners” and “like-minded small organizations.” Practitioners stressed the value of forming partnerships with funders, co-producing across the cultural sector, and consulting the community. They advised others to liaise with public health, build relationships with the NHS and local authorities, and connect with other agencies such as social and dementia care. Within ‘Developing a practice’ they spoke about the need “to grow some roots” within a particular discipline, without becoming “shackled by traditional practice.” They also talked about taking a variety of approaches to promoting the work and favoring inclusive language (“careful choice of words”) to ensure a breadth of participation.

3.10 Common features

To address the aim of identifying common features of environmentally and socially engaged community programs, subthemes derived from three or four similar responses (37.5–50% of practitioners) were located by combining Tables 3–11 (Appendix 1). Ten subthemes, derived from 32 responses constituting just over a fifth (21.92%) of all responses and contributing to the five major themes, were identified as common features of the practices of those interviewed (Figure 2). The two most common features, each with four similar responses, were ‘Preventative measures’, within the theme of ‘Mental health’ and ‘Supporting isolated people’, within the theme of ‘Community health and wellbeing’. The remaining eight common features, each with three similar responses, were ‘Research evidence’ and ‘Looking after our staff, within the theme of ‘Mental health’; ‘Connecting with care agencies’, within the theme of ‘Community health and wellbeing’; ‘Having sufficient funding’ and ‘Paid practitioner opportunities’, within the theme of ‘Funding’; ‘Connection to nature in children’ and ‘Relationship with the natural world’, within the theme of ‘Connection with nature; and ‘Influencing wider systems’, within the theme of ‘Collaboration and partnerships’.

4 Discussion

The current research aimed to identify common features of environmentally and socially engaged community programs, specifically those addressing the intersecting challenges of planetary and human health. To achieve this aim, the study analyzed survey and interview data from creative health practitioners. Practices employed a variety of interventions involving arts and crafts, breathing techniques, creative writing, discussion, forest bathing, gardening, meditation and mindfulness, singing, and walking. Some activities were held indoors whereas others took place in green and blue, and rural and urban spaces. Findings showed that over two thirds of participant responses were distributed across five major themes: ‘Mental health’; ‘Community health and wellbeing’; ‘Funding’; ‘Connection to Nature’; and ‘Collaboration and partnerships’. Ten of the subthemes within these major themes, based on three or more similar responses from different practitioners, were deemed common features of community programs (Figure 2).

On the whole practitioners felt that the health, social and environmental aspects of their work were of equal importance in that they were interconnected and needed to be addressed together. A study determining priority areas for future research into inequalities showed a similar finding (24). Practitioners acknowledged the intersection of planetary and human approaches to health, promoting the idea that arts engagement could help to “mitigate the effects of an adverse environment” [(30), p. 10]. Some practitioners, though, held individual views not shared with other practitioners. Consequently, of the 10 subthemes reflecting common features among practices, only two addressed the intersecting challenges of planetary and human health directly. These were ‘Connection to nature in children’ and ‘Relationship with natural world’, through practices recognizing environmental and human interdependency. Findings aligned with the work of other authors who hypothesized that connection to nature might mediate health and wellbeing gains from the natural environment that might play a role in pro-environmental or pro-conservation and behaviors (34). Evidence for these benefits, however, was described as “patchy” and recommendations aligned with the notion that findings should be “brought systematically together to inform transferal and scaling of programs between contexts and populations” [(32), p. 81].

Four subthemes of ‘Influencing wider systems’, ‘Looking after our staff’, ‘Preventative measures’, and ‘Research evidence’ addressed the intersecting challenges of planetary and human health indirectly through practitioner partnership influence over policies relating to climate change, and by addressing concern for the environment manifesting in eco-anxiety. Analysis of community practitioner case studies showed that connections needed to be built between climate and health through creative programming intended to link nature, health and wellbeing outcomes (37). Other researchers proposed that planetary health should draw attention to the “integration of biological, psychological, social and cultural aspects of health in the modern environment” [(10), p. 1], aligning with the biopsychosocial model of health (38). In the current study, practitioners talked about developing their practices over several years and typically described their work as “process-led with a focus on the doing of the activity” in contrast with evaluation of end products such as artworks or wellbeing. As a result, practices were not set up as models intended to build creative, climate and health connections Instead practices evolved over time and, as one practitioner expressed, “adjusted to prevailing trends.”

With respect to mental health, practitioners described their own feelings of anxiety toward climate crisis or those of their collaborators or participants. As one creative health practitioner stated, “I have a lot of tension in myself where I think that I should be doing more” and “individual artists do feel, and individual humans do feel a massive burden for responsibility for global warming… all these massive issues.” Along with the emotional impacts of working with people facing mental health challenges, this ‘eco-anxiety’ also contributed to the subtheme of ‘Looking after our staff’. Another practitioner explained how creative activities facilitated space for discussion on the “collective trauma” of climate change. Practitioners were keen to promote “system change in terms of mental health and wellbeing,” moving from “dealing with an escalation” to “something which is much more preventative.” Although they did not formally evaluate their own projects, practitioners commonly cited various sources, particularly mental health studies, advocating increased use of preventative measures such as creative health practices. They suggested that the natural environment could be used as a resource for the prevention or treatment of poor mental health and that longer-term programs might be more effective than those in the short-term. Participants highlighted the need for more good quality evaluation and research on the impacts and cost-effectiveness of natural environment-based health interventions. Their suggestions were in keeping with the proposal that “existing evidence should be brought together using systematic approaches” [(32), p. 81].

The remaining four subthemes informing common features of practice (‘Connecting with care agencies’; ‘Supporting isolated people’; Having sufficient funding’; and ‘Paid practitioner opportunities’) were ostensibly concerned with human health and wellbeing particularly in isolated communities. Common features of practice were underpinned by connecting with other people and agencies and obtaining funding. Practitioners were generally of the view that developing their own approaches and resources “strengthened local social, economic, environmental, cultural and political circumstances” [(20), p. 11]. Developing these approaches led them to boost both their own and community health (20). Nearly all practitioners reported that their intended outcomes related to addressing social factors aligning with statistics showing that 30–55 per cent of health outcomes are rooted in social outcomes which are “more important than health care or lifestyle choices in influencing health” [(28) p. 1]. Practices were in keeping with the assertion that “the most effective actions to reduce health inequalities will come through action within the social determinants of health” [(11), p. 86]. They agreed that in public policy discourse, engagement with the arts and culture is “typically connected to such wider societal targets as improving the welfare of citizens, building social connectedness, revitalizing marginalizing areas, and boosting creativity and innovativeness” [(27), p. 16]. The common features of obtaining sufficient funding and paying practitioners were unsurprising given the wider state of underfunding for both direct delivery and the ecosystem of the creative health sector (39). It is also worth noting that higher education institutions typically can apply for funding for research but not for service provision. Case studies exploring barriers and enablers faced by UK creative and cultural practitioners addressing planetary and human health found that a key barrier was a lack of long-term funding to develop capacity for partnerships, networks, and policy influence whereas a key enabler was institutional commitment to increase resources (37). Findings were, therefore, consistent with the case study evaluation in that “climate, health and creativity are not separate in people’s experiences” but they are separated by “funding and organizational structures” [(37), p. 1].

4.1 Limitations

Findings from the current study should be interpreted with caution because of the restricted number of practitioners interviewed due to the stringency of inclusion criteria and the fact that several practitioners who completed the survey did not consider their work to be creative or cultural despite being referred by another participant or organization. It should be noted that seven out of eight practitioners interviewed (87.5%) were female, typical of the creative health sector; diversity statistics for creative health found a similar female workforce (87.8%) (40). Demographic data was not sought, however, so age or ethnicity cannot be compared. Practitioners regularly reported that limitations on funding makes formal evaluation challenging, so evidence was not sought in the form of reports or evaluations; instead, anecdotal evidence reported by practitioners was analyzed. Consequently, views could be said to be subjective rather than objective, though in keeping with the constructivist methods used. A research approach only employing larger organizations with the funding, expertise, resources, and time to carry out robust evaluation would have risked excluding many creative health projects. In employing an interpretivist epistemology, the researchers understand that they are never removed from the research process and acknowledge that their understanding of the potential of creative health practices may have predisposed them to certain conclusions.

5 Conclusion

The current study aimed to expand upon the Creative Health Quality Framework (36) by identifying common features of environmentally and socially engaged community programs, specifically those addressing the intersecting challenges of planetary and human health. Creative health practices described by those interviewed were diverse, varying greatly depending on the communities in which they were located, and the cultural or creative organisations, practitioners and resources involved. The interventions, while superficially simple—often founded in conversation—rest on paying careful attention to bringing people together in spaces that feel open, safe and warm and being led by their own responses to nature and creativity. By identifying commonalities, the study drew attention to practitioners’ socially determined views of health, and desire to work collaboratively for mutual support and shared resources. Results of the study may be utilized by commissioners and funders to better understand connections between planetary and human health as they operate for community organizations and to consider how their funding and commissioning structures might support these. Results may also be helpful for creative practitioners to address the wider social determinants of health, including planetary health, to tackle health inequalities with the intention of maximizing “human wellbeing for present and future generations while remaining safely within ecological boundaries” [(2), p. 1]. To achieve this goal requires “a more complete understanding of community wellbeing and alternative ways of characterizing it” [(2), p. 1]. Given that until recently wellbeing was understood “mainly in economic terms,” it is now necessary “to enrich the understanding of wellbeing on the basis of a relational paradigm, in which the dependency of human wellbeing on the health of the ecosystems is internalized” [(13), p. 167]. As it is likely that creativity and culture are under-tapped resources, the potential to address community and environmental issues to tackle health inequalities, especially those resulting from climate injustice, has not yet been fully realized. The current study indicates the need for inclusive practice, partnership work, and sustainable funding which can support both practitioner wellbeing and the process, outputs and impacts of natural and sustainable environment-based health interventions and other resources instrumental in preventative healthcare.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Research Ethics Committee of University College London. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

LT: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. VH: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HC: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The research was funded by UK Research and Innovation (UKRI/AHRC: AH/W006405/1; PI: HJ Chatterjee) as part of the Mobilizing Community Assets to Tackle Health Inequalities research program.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the creative health practitioners for participating in the survey and interviews.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1449317/full#supplementary-material

References

1. World Health Organization. World health day 2022: Our planet, our health. Geneva: World Health Organization (2022).

2. Movahed, NY. Nurturing the nurturing mother: a method to assess the interdependence of human and planetary health through community wellbeing In: P Kraeger, S Cloutier, and C Talmage, editors. New dimensions in community wellbeing. Community quality-of-life and wellbeing. Cham: Springer (2017)

3. Whitmee, S, Haines, A, and Beyrer, C. Safeguarding human health in the Anthropocene epoch: report of the Rockefeller Foundation–lancet commission on planetary health. Lancet. (2024) 2015:1973–2028. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60901-1

4. Rowse, L. United Kingdom research and innovation (UKRI) planetary health workshop report. Swindon: UKRI (2022).

5. World Health Organization Commission on Health and Environment. Our planet, our health: Report of the WHO Commission on health and environment. Geneva: World Health Organization (1992).

6. Planetary Health Alliance. Planetary health (2023). Available at: https://www.planetaryhealthalliance.org/planetary-health (Accessed 10 June 2024).

7. Bandarage, A. Sustainability and well-being: The path to environment, society, and the economy. London: Palgrave Macmillan (2013).

8. Prescott, SL, and Logan, AC. Planetary health: from the wellspring of holistic medicine to personal and public health imperative. Exp Dermatol. (2019) 15:98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2018.09.002

10. Logan, AC, Berman, SH, Berman, BM, and Prescott, SL. Project earthrise: inspiring creativity, kindness and imagination in planetary health. Challenges. (2020) 11:1–23. doi: 10.3390/challe11020019

11. Marmot, M, Allen, J, and Goldblatt, P. Fair society, healthy lives: The Marmot review: Strategic review of health inequalities in England post-2010. London: The Marmot Review (2010).

12. Steffen, W, Richardson, K, Rockström, J, Cornell, SE, Fetzer, I, Bennett, EM, et al. Planetary boundaries: guiding human development on a changing planet. Science. (2015) 347:1–11. doi: 10.1126/science.1259855

13. Helne, T, and Hirvilammi, T. Wellbeing and sustainability: a relational approach. Sustain Dev. (2015) 23:167–75. doi: 10.1002/sd.1581

14. De Castañeda, RR, Villers, J, and Guzmán, CAF. One health and planetary health research: leveraging differences to grow together. Lancet Plan Health. (2023) 7:e109–11. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(23)00002-5

15. Ventegodt, S, Kandel, I, and Ervin, DA. Concepts of holistic care In: IL Rubin, J Merrick, and DE Greydanus, editors. Health care for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities across the lifespan. Cham, Switzerland: Springer (2016). 1935–41.

16. American Veterinary Medical Association. One health: A new professional imperative. One health initiative task force: Final report. Schaumburg: American Veterinary Medical Association (2008).

17. Essack, SY. Environment: the neglected component of the one health triad. Lancet Plan Health. (2018) 2:e238–9. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(18)30124-4

18. Zinsstag, J, Schelling, E, and Crump, L. One health: The theory and practice of integrated health approaches. Wallingford: CABI Publishing (2020).

19. Hort, K, Sommanustweechai, A, Adisasmito, W, and Gleeson, L. Stewardship of health security: the challenges of applying the one health approach. Public Adm Dev. (2019) 39:23–33. doi: 10.1002/pad.1826

20. Marmot, M, Allen, S, and Boyce, T. Health equity in England: The Marmot review 10 years on. London: Institute of Health Equity (2020).

21. Baker, JL. Climate change, disaster risk, and the urban poor: Cities building resilience for a changing world. Washington, DC: World Bank Publication (2012).

22. Redvers, N. The determinants of planetary health. Lancet Plan Health. (2021) 5:E111–2. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00008-5

23. NHS England. What are healthcare inequalities? (2020). Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/about/equality/equality-hub/national-healthcare-inequalities-improvement-programme/what-are-healthcare-inequalities/#:~:text=Health%20inequalities%20are%20unfair%20and,that%20is%20available%20to%20them (Accessed 10 June 2024).

24. Thomson, LJ, Gordon-Nesbitt, R, Elsden, E, and Chatterjee, HJ. The role of cultural, community and natural assets in addressing societal and structural health inequalities in the UK: future research priorities. Int J Equity Health. (2021) 20:249–15. doi: 10.1186/s12939-021-01590-4

25. Chatterjee, HJ. How can community assets, creative health partnerships and social prescribing tackle health inequalities? (2021). Available at: https://ucleuropeblog.com/2021/06/28/how-can-community-assets-creative-health-partnerships-and-social-prescribing-tackle-health-inequalities/ (Accessed 10 June 2024).

26. Culture, Health and Wellbeing Alliance (CHWA). How culture and creativity have been supporting people in health, care and other institutions during the Covid-19 pandemic. Barnsley: CHWA (2021).

27. Sloboda, J, Baker, G, and De Bisschop, A. Music for social impact: an overview of context, policy and activity in four countries, Belgium, Colombia, Finland, and the UK. Finn J Music Educ. (2020) 23:116–43.

28. World Health Organization. Social determinants of health (2023). Available at: https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1 (Accessed 10 June 2024).

29. Matarasso, F. A restless art: How participation won, and why it matters. Lisbon and London: Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation (2019).

30. All-party Parliamentary Group on Arts. Health and wellbeing. Creative health: The arts for health and wellbeing. London: APPGAHW (2017).

31. All-party Parliamentary Group on Arts, Health and wellbeing and National Centre for creative health. Creative Health Review (2023). Available at: https://ncch.org.uk/creative-health-review (Accessed 10 June 2024).

32. Lovell, R, Wheeler, B, and Husk, K. What works briefing on natural environment based health interventions. Exeter: University of Exeter Medical School (2019).

33. Seers, H, Mughal, R, and Chatterjee, HJ. National academy for social prescribing, UK. How the natural environment can support children and young people In: Natural England evidence information note EIN067. London: Natural England (2022)

34. Seers, H, Mughal, R, and Chatterjee, HJ. National Academy for social prescribing, UK In: Connection to nature. Natural England evidence information note EIN068. London: Natural England (2022)

35. Thomson, LJ, Spiro, N, and Williamon, A. The impact of culture-, health- and nature-based engagement on mitigating the adverse effects of public health restrictions on wellbeing, social connectedness and loneliness during COVID-19: quantitative evidence from a smaller- and larger-scale UK survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2023) 20:6943. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20206943

36. Willis, J, and Hume, V. Culture, health and wellbeing Alliance (CHWA) creative health quality framework. Barnsley: CHWA (2023).

37. Culture, Health and Wellbeing Alliance (CHWA). Creativity, climate and health: Case studies and analysis. Barnsley: CHWA (2022).

38. Frazier, LD. The past, present, and future of the biopsychosocial model: a review of the biopsychosocial model of health and disease: new philosophical and scientific developments by Derek Bolton and Grant Gillett. New Ideas Psychol. (2020) 57:100755. doi: 10.1016/j.newideapsych.2019.100755

39. Tang, J. Creative health: UK state of the sector survey (2024). Available at: https://www.culturehealthandwellbeing.org.uk/sites/default/files/SectorReport_202040201.pdf (Accessed 10 June 2024).

40. Tang, J. Creative health: UK state of the sector equality, diversity & representation report (2024). Available at: https://www.culturehealthandwellbeing.org.uk/sites/default/files/DiversityReport_20240201.pdf (Accessed 10 June 2024).

Keywords: community programs, creative health, human health, mental health, planetary health, social determinants of health, sustainability, wellbeing

Citation: Thomson LJM, Critten A, Hume V and Chatterjee HJ (2025) Common features of environmentally and socially engaged community programs addressing the intersecting challenges of planetary and human health: mixed methods analysis of survey and interview evidence from creative health practitioners. Front. Public Health. 13:1449317. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1449317

Edited by:

Zeyuan Qiu, New Jersey Institute of Technology, United StatesReviewed by:

Dana Perniu, Transilvania University of Brașov, RomaniaJamie Harvie, Harvie Consulting, United States

Copyright © 2025 Thomson, Critten, Hume and Chatterjee. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Linda J. M. Thomson, bGluZGEudGhvbXNvbkB1Y2wuYWMudWs=; Helen J. Chatterjee, aC5jaGF0dGVyamVlQHVjbC5hYy51aw==

Linda J. M. Thomson

Linda J. M. Thomson Ailsa Critten2

Ailsa Critten2 Helen J. Chatterjee

Helen J. Chatterjee