- 1Department of Epidemiology and Research, National Heart Foundation Hospital and Research Institute, Dhaka, Bangladesh

- 2Resolve To Save Lives (RTSL), New York, NY, United States

Introduction: Nutrition labeling provides nutritional information about nutrients present in a food product. It is commonly applied to packaged foods and beverages, where the information can be presented on the back or front of the pack as the nutrient declaration, nutrition and health claims, and supplementary nutrition information. Nutrition labeling is an important policy instrument for improving the nutritional quality of foods and promoting healthy diets, as it allows consumers to make informed purchasing decisions. This document review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of government-endorsed nutrition labeling policies related to nutrient declaration, nutrition claims, and supplementary nutrition information enforced worldwide.

Methods: We searched two nutrition policy databases, the Global database on the Implementation of Food and Nutrition Action (GIFNA) and the NOURISHING database, and government websites of some selected countries for the government-endorsed nutrition labeling policies published up to June 2023. We narrated the policy adopting countries' distribution by WHO regions, mode of implementation (voluntary or mandatory), and types of front-of-pack labels implemented.

Results: Globally, we found that 95 countries have mandatory policies for nutrient declarations on packages of processed products. These include 41 countries in Europe, 19 in America, 14 in the Western Pacific, nine in Africa, seven in the Eastern Mediterranean region, and five countries from South-East Asia. Additionally, 71 countries have policies on the use of nutrient claims like “fat-free,” “excellent source,” and “fortified.” European region has the highest number of countries (37) that have rules on nutrient claims. Front-of-pack labeling (FOPL) policies have been introduced in 44 countries as supplementary nutrition information. Of these, 16 countries have adopted FOPL as mandatory, while others have implemented it voluntarily. The FOPL systems include warning labels, keyhole logo, health star rating, traffic light labeling, nutri-score, and healthy choice logos.

Conclusion: Over recent years, the number of countries adopting mandatory nutrition labeling policies, especially FOPLs, has increased globally. Labeling policies should be evidence-based and follow the best practices to protect consumers from unhealthy nutrients and promote healthy eating. FOPL designs need to be selected based on country-specific evidence of effectiveness and appropriateness, avoiding industry influence.

1 Introduction

Unhealthy diets are one of the leading causes of morbidity and disability globally (1). Rapid urbanization, expansion of processed products industries, and lifestyle changes have resulted in transitions in habitual dietary patterns worldwide. People are now shifting from their homemade traditional diets toward a diet high in processed food products, which are calorie-dense, high in carbohydrates, saturated fat, trans fat, salt, and added sugars (2). Such dietary practices are major contributors to obesity, cardiovascular disease (CVDs), high blood pressure, type 2 diabetes mellitus, cancers, and other diet-related non-communicable diseases (NCDs) (3, 4). Every year, around 17.9 million people die from CVDs, which comprises 32% of the total worldwide deaths (5). According to the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2019 report, dietary risk factors resulted globally in around 8 million deaths and 188 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) from CVDs each year (6). This dietary risk encompasses the inadequate intake of healthy-nutrient-rich foods like fruits, vegetables, legumes, nuts, and seafood with simultaneous excessive intake of calorie-dense processed products and foods having nutrients that are harmful to health such as added sugar, sodium, and trans-fatty acid (7).

Nutrition labeling is an important policy instrument for reducing malnutrition in all its forms, improving the nutritional quality of foods, and promoting healthy diets (8). Nutrition labeling has been recommended in several global agreements, approved by the World Health Assembly (WHA) since it provides the nutritional content of foods allowing consumers to make informed purchasing decisions (9, 10). Nutrition labeling may include ingredient lists, nutrient declarations, supplementary nutrient information, and nutrition and/or health claims. The nutrient declaration, more commonly known as Nutrition Fact Panel (NFP) and typically placed in the Back-of-Pack (BOP), is a standardized statement that lists nutrients (i.e., energy value, protein, available carbohydrate, fat, saturated fat, sodium, total sugar) present in the food along with their quantities. Supplementary nutrient information, like front-of-package labeling (FOPL), is a way to enhance consumers' understanding of the nutritional quality of food and to facilitate their interpretation of the nutrient declaration (11, 12). A nutrient claim means any representation that provides information about certain nutritional properties of a food product (e.g., “low sodium”). Health claims imply a relationship between a food or the consistency of that food and health (e.g., “heart-healthy”) (13). As many countries do not regulate these claims, companies often use nutrition and health claims without scientific basis, thus potentially creating a “health halo” to lead consumers into thinking their product is healthy, which may not be the case (14).

As part of multiple strategies for marketing restrictions on unhealthy processed products, the World Health Organization (WHO) has urged its member states to implement a government-led mandatory FOPL system as one of the “best buys” to promote healthy diet and control and prevent the burden of NCDs (15, 16). Food companies deliberately add misleading nutrition claims (e.g., “low fat” or “high in vitamins”) to create a “health halo effect,” which leads consumers to perceive unhealthy food products as healthier than they truly are. This can obscure the products' actual nutritional quality (17, 18). In such cases, FOPL provides consumers with nutrition information in a clearer and more understandable format. A growing body of evidence suggests that FOPLs can facilitate consumers' understanding of food nutritional quality, supporting healthier food choices. These labels guide consumers to compare similar products easily and help consumers avoid less nutritious processed products. By providing nutritional information, FOPLs empower consumers and encourage the selection of healthier options. Furthermore, it can also prompt processed products reformulation by respective industries to improve quality and appeal to health-conscious consumers and avoid negative marketing implications, such as by reducing trans-fat and sodium content (19–21). Multiple FOPL systems have been introduced by different countries, including warning labels, summary labels, or a combination of both logos and factual declarations (22, 23). FOPLs can be grouped into different types: informative/non-interpretative and interpretative (informative/non-interpretative FOPL provides factual information, whereas interpretative FOPL provides evaluative judgment on nutritional quality); directive, non-directive, and semi-directive labels (based on the degree to which labels provide direct judgment about healthiness); nutrient-specific systems (focusing on specific nutrient concentrations) and nutrient summary systems (providing an overall healthfulness score) (11).

The purpose of this document review is to offer a comprehensive overview of available government-endorsed labeling policies around the world. The review aims to synthesize existing nutrition labeling policies, including nutrient declarations, rules on nutrient claims, and FOPL schemes.

2 Methods

To conduct this document review, we searched two policy databases, the Global Database on the Implementation of Food and Nutrition Action (GIFNA) (23) of the World Health Organization (WHO) and NOURISHING policy databases of the World Cancer Research Fund International (22, 23). The search was conducted during the period of July to October 2023 to identify the nutrition labeling policies published/enforced up to June 2023 in different countries around the world. The GIFNA database has “front-of-pack and other interpretive nutrition labeling” and “country score card” for sodium and sugar, which document countries' progress in implementing supplementary nutrition labels (FOPL and other interpretive labels) and declaration of sugar and sodium on the packaged food. The NOURISHING database contains information on policies regarding food labeling and restrictions on products high in sugar, salt, and fat. We used a list of keywords for searching the databases: the keywords were “nutrition labeling,” “front-of-pack labeling,” “warning label,” “law,” “legislation,” and “policies.” The keywords were translated into the country's respective languages for countries with policies in their native languages. In addition, we double-checked the search results by looking through the national websites and publicly available resources on Google, such as official and intergovernmental reports.

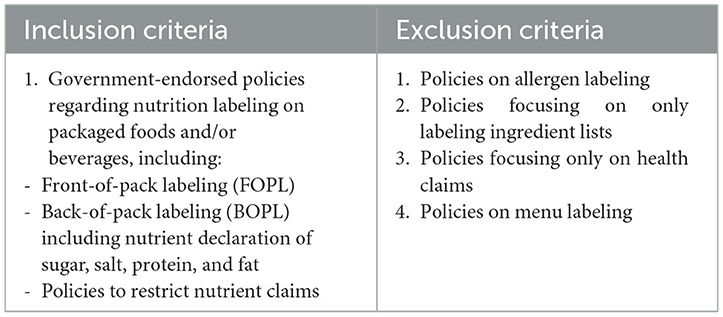

We developed and followed relevant inclusion and exclusion criteria for our research questions (Table 1) to provide an overview of government-endorsed labeling policies around the world. In this review, we included only the policies endorsed by the government and excluded the initiatives introduced by non-government private institutions, civil society organizations, or the food industry as they are often self-regulatory and are enforced with very limited uptake. Regarding the claims, we included policies on nutritional claims only, as other claims, health and risk reduction claims, are often confusing for the consumers and misleading.

We reviewed the policies selected according to the predefined criteria to describe the geographical distribution of the policy-adopting countries according to the WHO regions, types of implementation– voluntary or mandatory, and the types of schemes for the front-of-pack labels. The policy documents that were not in English were translated using Google Translate.

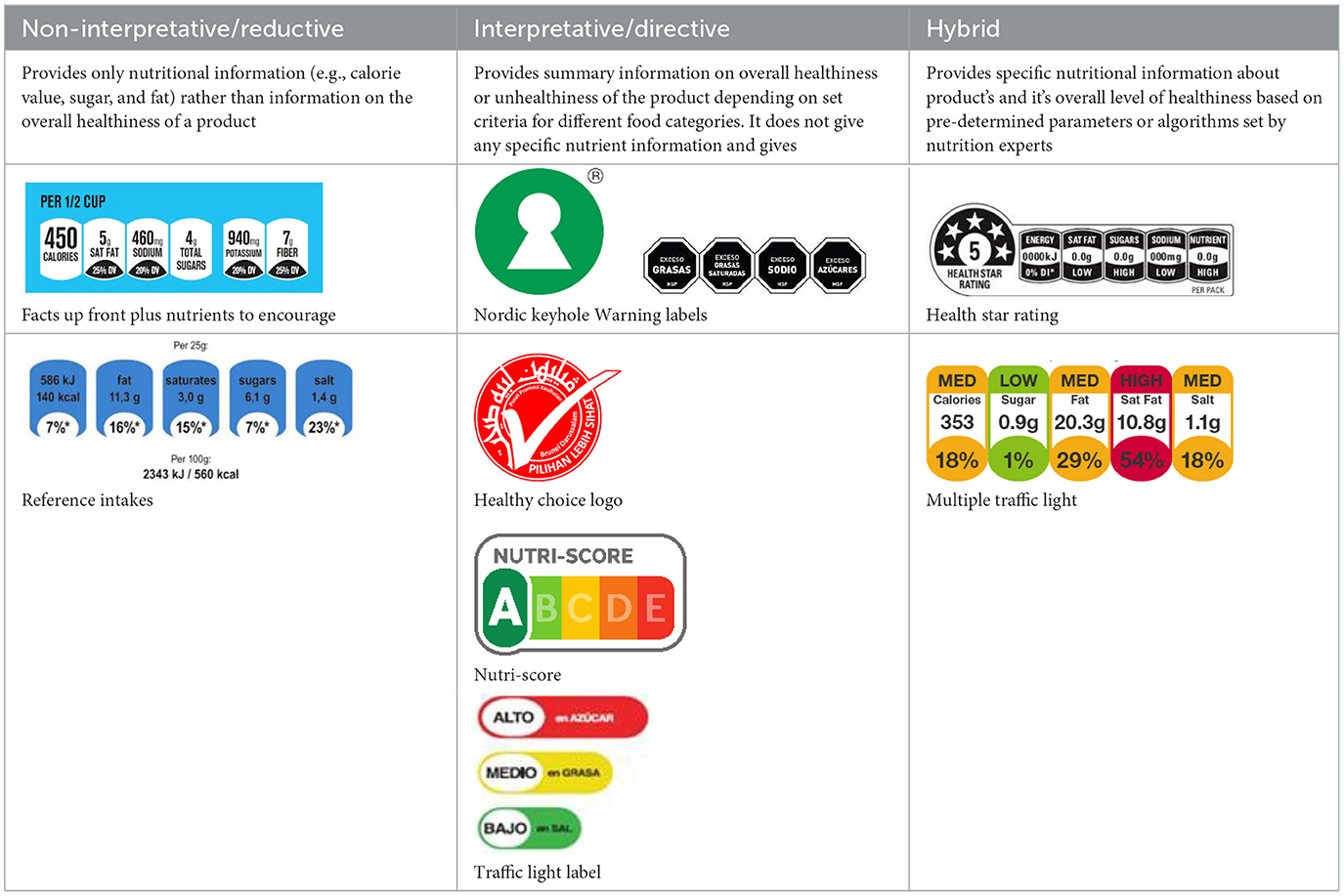

In this review, we organized the available nutrition labeling policies under three categories: (1) nutrient declaration, which included listing of ingredients and nutrients, (2) nutrition claims, which included content and comparative nutrient claims, and (3) supplementary nutrition information, which included front-of-pack nutrition labeling. To describe the types of front-of-pack nutrition labels, we classified the available FOPL schemes based on their approach to providing information about processed products into three types: (a) non-interpretative or reductive, which provide nutrient content information only with no specific judgment on the overall nutritional value of the food, (b) interpretative or directive system, which provide guidance on the relative healthfulness or unhealthfulness of the food, and (c) hybrid systems, which provide both nutrient content information with numbers and judgment on the nutritional values with additional colors or symbols (Table 2).

3 Results

This document review presents an overview of the nutrition labeling policies adopted by different countries around the world.

3.1 Nutrient declaration

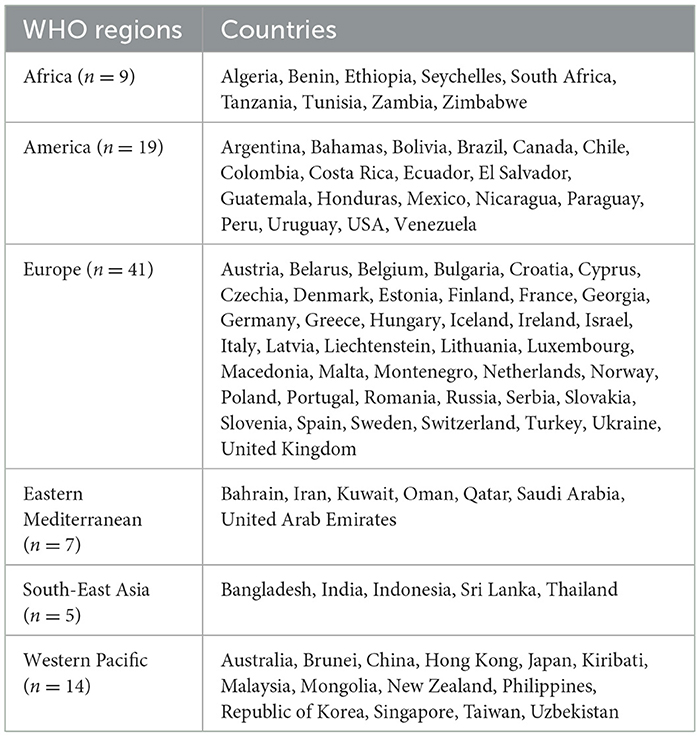

Table 3 provides an overview of countries that have adopted mandatory policies for nutrient declaration. A total of 95 countries have policies on nutrient declaration. By region, the highest in Europe (41), followed by America (19), the Western Pacific (14) and Africa (nine). Eastern Mediterranean (seven) and South-East Asia (five) are the regions with the lowest countries having a nutrient declaration policy.

Most of the countries in European region are members of the European Union (EU). From 13th December 2016, EU Regulation 1169/2011 on the “Provision of Food Information to Consumers” made it mandatory to provide a list of the nutrients and information on the energy value, amounts of fat, saturates, carbohydrates, sugars, protein, and salt, mentioning by 100 g or 100 ml, for most of the pre-packaged foods on their back of packages (24). All 27 EU member countries have followed the mandatory nutrient declaration of packaged products.

In the American region, 19 countries, including the USA, Canada, and Mexico, have adopted these regulations. Seven countries in the Eastern Mediterranean region have a nutrient declaration policy. Of them, six countries—United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Oman, Kuwait, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia—have a common regulation under the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC); the remaining one is Iran. Five countries of South-East Asia region, including Bangladesh, have a policy of nutrient declaration. The Western Pacific region lists fourteen countries, including Australia, China, and Japan.

All the policies included a mandatory declaration of ingredients on the pre-packaged food labels, and most of them included additional requirements of mentioning nutrients and their amounts. The declaration of nutrients on the food package labels is compulsory in both developed and developing countries across diverse regions.

3.2 Nutrition claims

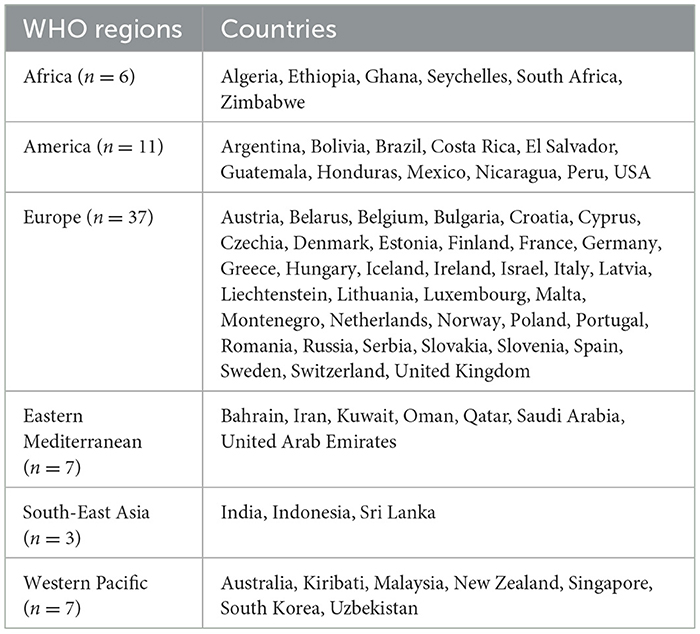

We have identified 71 countries having a policy on nutrition claims. Most of the countries with such policy are from the WHO European region (37) America (11), an equal number of countries (seven) from each of the Eastern Mediterranean and Western Pacific. Africa (six) and South-East Asia (three) have the lowest number of countries that have rules on nutrition claims. Table 4 provides an overview of the countries that have policies on nutritional claims.

The importance of regulating nutrition claims is to ensure that they accurately reflect the nutritional quality of a product. Under these regulations, nutrition claims are only allowed if the product meets specific nutrient profile criteria, such as limits on sugar, fat, or sodium content. This helps consumers make informed decisions based on trustworthy information, reducing the risk of being misled by claims that do not align with the overall healthfulness of the product.

3.3 Front-of-package labeling policies

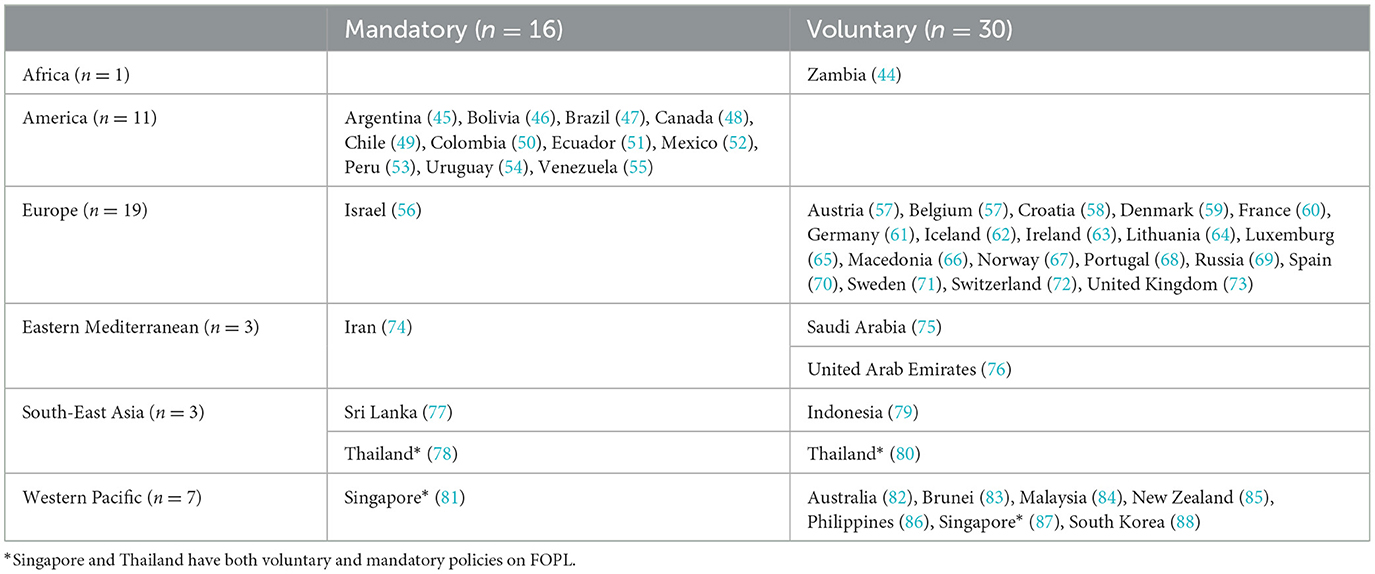

In this review, we found that 44 countries have a government-endorsed policy for front-of-pack labeling (FOPL) schemes. Of them, 16 countries have adopted FOPL as mandatory, while the remaining have implemented it voluntarily (Table 5).

Mandatory FOPL policies are predominantly found in the American region, with 11 countries, including Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, Peru, Uruguay, and Venezuela. Israel from Europe, Iran from the Eastern Mediterranean, Sri Lanka and Thailand from South-East Asia, and Singapore from the Western Pacific also have mandatory FOPL policies. Notably, Singapore and Thailand have policies that are both mandatory and voluntary for different schemes of FOPL. Countries that have adopted and implemented FOPL schemes as mandatory, require food manufacturers to adopt and display on processed products by law. This regulatory approach ensures uniformity across the food industry, aiming to provide consumers with consistent information about key nutrients, such as sugar, salt, and fat.

Countries adopting the FOPL policies voluntarily are mainly from the European region, with 18 countries implementing these policies. There is no regional standard policy for the FOPL like the nutrient declaration policy adopted by the EU and GCC. In the Western Pacific region, six countries- Australia, Brunei, Malaysia, New Zealand, Philippines, Singapore, and South Korea have adopted voluntary FOPL policy. In the African region, only Zambia has implemented a voluntary FOPL policy. Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates from the Eastern Mediterranean, and Indonesia and Thailand from South-East Asia have adopted the FOPL policy voluntarily. Voluntary FOPL policies allow manufacturers to choose whether to use specific labels on their products. This approach provides flexibility for companies to market healthier options without legal compulsion. Voluntary policies encourage manufacturers to adopt labels that highlight positive nutritional attributes but do not enforce uniformity across all products.

3.4 Types of FOPL schemes used

A comprehensive document review of FOPL systems across various countries reveals a diverse landscape of approaches designed to guide consumers in making healthier food choices regarding the nutritional content of processed products. In our review, we found four types of interpretive, one non-interpretive, and two hybrid schemes of FOPL in implementation in 44 countries worldwide. An interpretive approach has been adopted in 33 countries, a non-interpretive approach in only one country (Thailand), and a mixed/hybrid approach in 10 countries (Table 6).

Of the interpretive approaches, a single healthy food endorsement logo was adopted in 14 countries (Keyhole Logo in six countries and Healthier Choice Logo in eight countries), the Warning Label in 10 countries, the Nutri-score/Nutri-grade scheme in nine countries, and Traffic Light Labeling (TLL) in two countries. Of the hybrid approaches, the Multiple Traffic Light system was adopted in eight countries, and Health Star Rating in three countries. The single healthy food endorsement logo is broadly of two types—the Nordic Keyhole Logo, first introduced by Sweden, and the Healthier Choice Logo, initiated by the Choices Programme. The Healthier Choice Logos varied from country to country in their design and criteria for defining the healthiness of a food.

The warning label was the most common type of mandatory interpretive system, adopted mostly in the countries of the American region. Only Israel has the red warning label, and the rest of the country has black, although the shape of the warning label varies from country to country. Warning labels alert consumers to specific nutrients of concern, promoting informed decision-making.

The Nutri-score/Nutri-grade systems adopting countries were mostly in the European region, and the adoption was voluntary. The Nutri-score/Nutri-grade and TLL systems offer interpretive guidance to consumers about the nutritional quality of products through different color codes. Non-interpretative mandatory FOPLs, like Thailand's Guideline Daily Amounts (GDA), provide consumers with essential nutritional information without interpretative guidance.

Hybrid FOPL systems combine interpretative and non-interpretative elements. It incorporated the nutrient-specific information of GDA with an interpretive indicator of TLL in the Multiple Traffic Light system, and with the summary indicator in the Health Star Rating. South Korea first introduced the Multiple Traffic Light system, and Australia and New Zealand started the Health Star Rating system.

4 Discussion

In this document review, we compiled government-endorsed policies on nutrition labeling for packaged products available worldwide. Our review presents a comprehensive view of the nutrition labeling policies that may contribute to a reduction in population intake of unhealthy nutrients of concern. Following the Codex Alimentarius guideline (25), we reviewed policies on nutrient and ingredient declaration, nutrition claims, and supplementary nutrition information which focused on front-of-pack labeling (FOPL). Mandatory nutrient declaration on food packages is a key prerequisite for establishing FOPL and other nutrition policies (26–28). This review found that the declaration of ingredients and nutrients of packaged food products on their pack label is mandatory in 95 countries, 71 countries have rules for making a nutrient claims about the product, and 44 countries have FOPL policies. Among the countries having FOPL policies, 16 countries have adopted it as mandatory and 30 as voluntary. Two countries, Thailand and Singapore, have both voluntary and mandatory FOPL policies. Thailand has a mandatory Guideline Daily Amount (GDA) system for certain snack foods high in sugar, fat, and sodium, while a voluntary Healthier Choice Logo is used for categories such as snacks, beverages, dairy products, and ready-to-eat meals. Similarly, Singapore mandates the Nutri-Grade label for pre-packaged beverages with higher sugar and fat content, while the Healthier Choice Symbol remains voluntary for a wide range of food categories, including beverages, snacks, cooking oils, and sauces. Of the countries with mandatory FOPL policy, Bolivia, Canada, and Venezuela have adopted it as mandatory but have not implemented it until our review period. Venezuela is already in the implementation process and it will be implemented by December 2024 (29) and the food industry of Canada has until 1 January 2026 to implement it (30). Bolivia is contemplating transitioning from its interpretive-only Nutritional Traffic Light system to a warning label scheme to enhance consumer awareness of nutritional content.

The necessity of nutrition labeling was raised with the increasing availability of processed food products from the mid-20th century onward to ensure food quality and inform consumers. In 1972, the US FDA first proposed a regulation to declare nutritional information on the pack label. Later, Codex Alimentarius formulated guidelines on nutrition labeling in 1985 (31). The Codex guideline is mainly accepted and adopted by countries worldwide. In all countries with nutrient declaration policies, the list of ingredients must be included on the pack label, together with the declaration of nutrient components and their amounts. Different ministries and authorities —like the Ministry of Health, Ministry of Food, Ministry of Industry, and Municipalities— implemented this policy of nutrient declaration in different countries worldwide. The majority of the countries that have a policy on nutrition claims have adopted it in the same policy of nutrient declaration. Regarding nutrition claims, some countries have mentioned that any claim should be based on scientific evidence and the actual amount of content, whereas in many countries, specifications for different claims—such as free, low, high, enrich, etc.—have been documented in the regulation. Setting the specification for nutrition claims included many nutrients beyond the nutrients of concern. We excluded health claim-related policies from this review as health claims have a diverse dimension in practice, are confusing for consumers most of the time, and are difficult to formulate in regulations.

In 2004 WHO proposed nutritional labeling in accordance with Codex Alimentarius guidelines as part of its Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health (32). The nutrient declaration aims in informing consumers about the specific nutrient content of foods, although it can be difficult to understand (26). In addition to being difficult to understand, barriers to using nutrition labels include illiteracy, lack of awareness, and distrust (28). A significant milestone in nutrition labeling was achieved during the WHO technical meeting on FOPL in December 2015, where a set of guiding principles for FOPL was established. These principles were further developed and updated in June 2017 (26). FOPL creates a positive food environment by supporting consumers in making healthier food choices quickly in a complex food environment and promoting food reformulation (27, 31, 33). The FOPL policy has been adopted in most countries as a voluntary approach; Ecuador was the first country that made it mandatory in 2014. Because of regulatory limitations, none of the EU countries could formulate any mandatory FOPL policies (24, 34).

Interpretive models of FOPL have been adopted more in recent years among the available schemes since evidence suggests that they are more effective in promoting healthy dietary habits. WHO Guiding Principles and Framework Manual (26) recommended interpretative labels for FOPL, especially those that use interpretational visual aids to minimize numerical information, as the best approach to aid consumers' comprehension of FOPL. They require less health and nutrition literacy, require less time, and help consumers in making quick decisions regarding the healthiness of the product. Among the interpretative FOPLs, warning labels have been adopted in 10 countries as mandatory FOPL policies. Finland first introduced a warning label to warn consumers against the high sodium content of a food; Chile was the first country in adopting a mandatory Warning Label to make consumers aware of the nutrients of concern and protect them from the harm of those nutrients (34).

Research has shown that mandatory FOPLs are more effective than voluntary systems in improving public health outcomes by providing consistent and clear nutritional information (35). A mandatory approach prevents food companies from selectively disclosing only favorable information, thereby reducing misleading marketing practices (36). Also, to avoid negative labeling manufacturers reformulate their products just below the nutrient cutoff, with common reformulated nutrients being sugar and sodium (37). Evaluations of Chile's mandatory warning labeling policy have shown significant declines in high-in nutrients of concern (sugar, salt, trans fat) in packaged food and beverage purchases, including a 20.2% relative reduction in sugar and a 13.8% relative reduction in sodium (38). Additional results show significant reformulation by the industry to avoid the warning label (39). However, when FOPL compliance is left voluntary, these labels often appear on some products but are absent from others. Furthermore, there is evidence that food companies selectively apply labels to healthier products while omitting them from less healthy options (36, 37). The review reveals significant variation in FOPL policies across countries, especially regarding nutrient thresholds. These differences are influenced by diverse dietary patterns, health priorities, and regulatory contexts. For example, countries with high rates of diet-related diseases may set stricter thresholds, while others adopt more moderate ones to fit local habits and industry practices. Gradual implementation of these thresholds allows manufacturers time to reformulate products and helps consumers adapt to new labeling practices. Understanding these variations is key to develop more effective and globally harmonized FOPL strategies.

The attempt to label healthier foods with an easy-to-interpret symbol is far older; in 1989, Sweden endorsed the “Keyhole” logo for the first time (31). Although the healthy food endorsement logo was the first FOPL system adopted, it is easy to manipulate and less effective in protecting consumers from harmful nutrients. Evaluating the effectiveness and comparing different types of FOPL was beyond the scope of our review, and there is ample evidence for such comparison. During our review, we explored that there are some industry-initiated initiatives for healthy food endorsement FOPL scheme. An industry-supported voluntary organization is working with various non-government and government organizations and agencies to promote such schemes, especially in the African and Asian continents. Adoption of voluntary FOPL in Zambia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines is the outcome of such efforts, which we included in this review because of the government endorsement. We excluded similar policies of more than ten countries, which are promoted by different non-government organizations of respective countries (27, 39–42). Adoption of those interpretative FOPL schemes can create a “health halo” making packaged foods appear healthy by including some positive nutrients despite containing some high levels of harmful nutrients of concern (43).

Strengths of this document review include our attempt to compile all existing government-endorsed nutrition labeling policies, especially he elaborated documentation of the policies on FOPL including the adopted schemes throughout the world. It included the declaration of key nutrient and ingredient lists, which is crucial for establishing further nutrition policies for NCD risk reduction and health promotion, like front-of-package labeling (FOPL) adoption, and setting maximum targets for nutrients of concern in packaged products. The limitations of this article are the absence of an in-depth analysis of each policy, a description of the step-by-step progress toward the current policy environment, and the exclusion of studies on the effectiveness of the various policies and programs. Moreover, in this review, we looked into two databases only, and there might be other uncovered similar policies in other databases. In addition, we did not identify the specific threshold levels for FOPLs in all of the reviewed policies, and no quality assessment scale was employed during this review.

5 Conclusion

This document review aims to provide documentation of the available government-endorsed nutrition labeling schemes adopted by countries worldwide. Nutrition labeling has been regarded as one of the most important policy solutions for tackling the burden of obesity and diet-related NCDs. To prevent death and disabilities from NCDs, countries around the world have been adopting mandatory nutrition labeling schemes to limit the purchase of foods high in unhealthy nutrients of concern. As of late 2023, 95 countries have adopted mandatory declaration of ingredients and nutrients, and 71 countries have adopted policies to regulate nutrient claims. For an easier understanding of nutrition information on food packaging, FOPL has been adopted by 44 countries, including interpretative, non-interpretative, and hybrid schemes, of which, 16 countries have adopted mandatory FOPL schemes. Over the last few years, there has been a strong global momentum for developing mandatory nutrition labeling policies, which should be continued using available experiences and evidence on the best standard of practice. Local evidence from scientifically sound robust studies may be required in selecting and designing the most effective, well-understandable, and appropriate FOPL schemes in a country-specific context. A highly cautionary approach should be followed during policy adoptions to avoid the nuance of industry-initiated misguidance and their interference.

Author contributions

UA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft. AA: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. AN: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Formal analysis. SS: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. NI: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. SC: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported in part by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation [Grant # INV-048317]. Under the grant conditions of the Foundation, a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Generic License has already been assigned to the Author Accepted Manuscript version that might arise from this submission. This project was also supported by Resolve to Save Lives, which receives funding in part from the Chan Zuckerberg Foundation [Grant # CZIF2022-007362].

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the editors and the reviewers for their useful feedback that improved this paper.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Afshin A, Sur PJ, Fay KA, Cornaby L, Ferrara G, Salama JS, et al. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. (2019) 393:1958–72. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30041-8

2. Popkin BM, Adair LS, Ng SW. Global nutrition transition and the pandemic of obesity in developing countries. Nutr Rev. (2012) 70:3–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00456.x

3. Stuckler D, McKee M, Ebrahim S, Basu S. Manufacturing epidemics: the role of global producers in increased consumption of unhealthy commodities including processed foods, alcohol, and tobacco. PLoS Med. (2012) 9:10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001235

4. Hall KD, Ayuketah A, Brychta R, Cai H, Cassimatis T, Chen KY, et al. Ultra-processed diets cause excess calorie intake and weight gain: an inpatient randomized controlled trial of ad libitum food intake. Cell Metab. (2019) 30:67–77.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.05.008

5. World Health Organization. Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). (2021). Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds) (accessed April 6, 2023).

6. Roth GA, Mensah GA, Johnson CO, Addolorato G, Ammirati E, Baddour LM, et al. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk factors, 1990-2019: update from the GBD 2019 study. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2020) 76:2982–3021. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.010

7. Al-Jawaldeh A, Abbass MMS. Unhealthy dietary habits and obesity: the major risk factors beyond non-communicable diseases in the Eastern Mediterranean region. Front Nutr. (2022) 9:817808. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.817808

8. Campos S, Doxey J, Hammond D. Nutrition labels on pre-packaged foods: a systematic review. Public Health Nutr. (2011) 14:1496–506. doi: 10.1017/S1368980010003290

9. World Health Organization (WHO). Nutrition Labelling: Policy Brief . (2022). Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240051324 (accessed May 8, 2023).

10. World Health Organization. Nutrient profiling: report of a WHO/IASO technical meeting, London, United Kingdom 4-6 October 2010. (2011). Available at: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/336447 (accessed April 6, 2023).

11. Kelly B, Jewell J. What is the evidence on the policy specifications, development processes and effectiveness of existing front-of-pack food labelling policies in the WHO European Region? Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534354/ (accessed April 18, 2024).

12. Food Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations World Health Organization. Guidelines on Nutrition Labelling. Available at: https://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/sh-proxy/en/?lnk=1&url=https%253A%252F%252Fworkspace.fao.org%252Fsites%252Fcodex%252FStandards%252FCXG%2B2-1985%252FCXG_002e.pdf (accessed July 16, 2024).

13. U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Label Claims for Conventional Foods and Dietary Supplements. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/food/food-labeling-nutrition/label-claims-conventional-foods-and-dietary-supplements (accessed October 21, 2023).

14. Prates SMS, Reis IA, Rojas CFU, Spinillo CG, Anastácio LR. Influence of nutrition claims on different models of front-of-package nutritional labeling in supposedly healthy foods: impact on the understanding of nutritional information, healthfulness perception, and purchase intention of Brazilian consumers. Front Nutr. (2022) 9:921065. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.921065

15. World Health Organization (WHO). NCD Best Buys and Other Effective Interventions. (2018). Available at: https://applications.emro.who.int/docs/EMROPUB_2018_EN_17036.pdf?ua=1 (accessed April 17, 2024).

16. UNICEF. Front-of-Pack Nutrition Labelling of Foods and Beverages. Available at: https://www.unicef.org/media/116686/file/Front-of-Pack%20Nutrition%20Labelling%20(FOPNL).pdf (accessed April 17, 2024).

17. World Heart Federation. Policy Brief: Front-of-Pack-Labelling. (2020). Available at: https://world-heart-federation.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/WHF-Policy-Brief-on-Front-of-Pack-Labelling.pdf (accessed September 19, 2024).

18. Panczyk M, Dobrowolski H, Sińska BI, Kucharska A, Jaworski M, Traczyk I. Food Front-of-pack labelling and the nutri-score nutrition label—poland-wide cross-sectional expert opinion study. Foods. (2023) 12:2346. doi: 10.3390/foods12122346

19. Shangguan S, Afshin A, Shulkin M, Ma W, Marsden D, Smith J, et al. A meta-analysis of food labeling effects on consumer diet behaviors and industry practices. Am J Prev Med. (2019) 56:300–14. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.09.024

20. Neal B, Crino M, Dunford E, Gao A, Greenland R, Li N, et al. Effects of different types of front-of-pack labelling information on the healthiness of food purchases-a randomised controlled trial. Nutrients. (2017) 9:1284. doi: 10.3390/nu9121284

21. Cecchini M, Warin L. Impact of food labelling systems on food choices and eating behaviours: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized studies. Obes Rev. (2016) 17:201–10. doi: 10.1111/obr.12364

22. World Cancer Research Fund International. NOURISHING and MOVING policy databases. Available at: https://policydatabase.wcrf.org/ (accessed October 20, 2023).

23. World Health Organization. Global database on the Implementation of Nutrition Action (GINA). Available at: https://extranet.who.int/nutrition/gina/en/home (accessed October 20, 2023).

24. European Commision. Nutrition Labelling. Available at: https://food.ec.europa.eu/safety/labelling-and-nutrition/food-information-consumers-legislation/nutrition-labelling_en (accessed October 21, 2023).

25. Food Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations World Health Organization (WHO). Codex Alimentarius. Guidelines on Nutrition Labelling. Available at: https://www.fao.org/ag/humannutrition/32443-04352e8311b857c57caf5ffc4c5c4a4cd.pdf (accessed August 26, 2024).

26. World Health Organization (WHO). Guiding principles and framework manual for front-of-pack labelling for promoting healthy diet. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/guidingprinciples-labelling-promoting-healthydiet (accessed February 7, 2024).

27. Croker H, Packer J, Russell SJ, Stansfield C, Viner RM. Front of pack nutritional labelling schemes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of recent evidence relating to objectively measured consumption and purchasing. J Hum Nutr Diet. (2020) 33:518–37. doi: 10.1111/jhn.12758

28. Hoteit M, Yazbeck N, Al-Jawaldeh A, Obeid C, Fattah HA, Ghader M, et al. Assessment of the knowledge, attitudes and practices of Lebanese shoppers towards food labeling: the first steps in the Nutri-score roadmap. F1000Res. (2022) 11:84. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.75703.1

29. FJS International Solutions. Venezuela Approves Additional Seals for the FOP Labelling. Available at: https://fjsinternationalsolutions.com/venezuela-approves-additional-seals-for-the-fop-labelling (accessed July 13, 2024).

30. Goverment of Canada. Nutrition labelling: Front-of-package nutrition symbol. Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-nutrition/nutrition-labelling/front-package.html (accessed July 13, 2024).

31. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Examination of Front-of-Package Nutrition Rating Systems and Symbols. Front-of-Package Nutrition Rating Systems and Symbols. National Academic Press (2010). Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK209847/ (accessed August 2, 2024).

32. World Health Organization (WHO). Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health. (2004). Available at: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/43035/9241592222_eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed 27 August 2024).

33. Jones A, Neal B, Reeve B, Ni Mhurchu C, Thow AM. Front-of-pack nutrition labelling to promote healthier diets: current practice and opportunities to strengthen regulation worldwide. BMJ Glob Health. (2019) 4:e001882. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001882

34. Reyes M, Garmendia ML, Olivares S, Aqueveque C, Zacarías I, Corvalán C. Development of the Chilean front-of-package food warning label. BMC Public Health. (2019) 19:906. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7118-1

35. Hammond D, Acton RB, Rynard VL, White CM, Vanderlee L, Bhawra J, et al. Awareness, use and understanding of nutrition labels among children and youth from six countries: findings from the 2019 – 2020 International Food Policy Study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. (2023) 20:55. doi: 10.1186/s12966-023-01455-9

36. Center for Science in the Public Interest. Front-of-Package Nutrition Labeling. Leveraging food labels to inform consumers and promote public health. (2023). Available at: https://www.cspinet.org/sites/default/files/2023-01/FOPNL%20Fact%20Sheet_1.10.23_final.pdf (accessed September 19, 2024).

37. Ganderats-Fuentes M, Morgan S. Front-of-package nutrition labeling and its impact on food industry practices: a systematic review of the evidence. Nutrients. (2023) 15:2630. doi: 10.3390/nu15112630

38. Taillie LS, Bercholz M, Popkin B, Rebolledo N, Reyes M, Corvalán C. Decreases in purchases of energy, sodium, sugar, and saturated fat 3 years after implementation of the Chilean food labeling and marketing law: an interrupted time series analysis. PLoS Med. (2024) 21:e1004463. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1004463

39. Reyes M, Taillie LS, Popkin B, Kanter R, Vandevijvere S, Corvalán C. Changes in the amount of nutrient of packaged foods and beverages after the initial implementation of the Chilean Law of Food Labelling and Advertising: a nonexperimental prospective study. PLoS Med. (2020) 17:e1003220. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003220

40. Taillie LS, Hall MG, Popkin BM, Ng SW, Murukutla N. Experimental studies of front-of-package nutrient warning labels on sugar-sweetened beverages and ultra-processed foods: a scoping review. Nutrients. (2020) 12:569. doi: 10.3390/nu12020569

41. Mora-Plazas M, Higgins ICA, Gomez LF, Hall M, Parra MF, Bercholz M, et al. Impact of nutrient warning labels on choice of ultra-processed food and drinks high in sugar, sodium, and saturated fat in Colombia: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE. (2022) 17:e0263324. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0263324

42. Arrúa A, MacHín L, Curutchet MR, Martínez J, Antúnez L, Alcaire F, et al. Warnings as a directive front-of-pack nutrition labelling scheme: comparison with the Guideline Daily Amount and traffic-light systems. Public Health Nutr. (2017) 20:2308–17. doi: 10.1017/S1368980017000866

43. Talati Z, Pettigrew S, Dixon H, Neal B, Ball K, Hughes C. Do health claims and front-of-pack labels lead to a positivity bias in unhealthy foods? Nutrients. (2016) 8:787. doi: 10.3390/nu8120787

44. World Food Programme (WPF). Good Food Logo: How a simple graphic aims to boost nutrition in Zambia. (2021). Available at: https://www.wfp.org/stories/good-food-logo-how-simple-graphic-aims-boost-nutrition-zambia (accessed 27 August 2024).

45. World Health Organization. Argentina: Front-of-Pack Labeling (FOPL) Policy. Global database on the Implementation of Food and Nutrition Action (GIFNA). (2021). Available at: https://gifna.who.int/countries/ARG/policies/82175 (accessed August 26, 2024).

46. World Health Organization. Bolivia: Front-of-Pack Labeling (FOPL) Policy. Global database on the Implementation of Food-related Nutrition Action (GIFNA). (2016). Available at: https://gifna.who.int/countries/BOL/policies/24664 (accessed August 26, 2024).

47. World Health Organization. Brazil: Front-of-Pack Labeling (FOPL) Policy. Global database on the Implementation of Food and Nutrition Action (GIFNA). (2020). Available at: https://gifna.who.int/countries/BRA/policies/41525 (accessed August 26, 2024).

48. World health Organization. Canada: Front-of-Pack Labeling (FOPL) Policy. Global database on the Implementation of Food-related Nutrition Action (GIFNA). (2022). Available at: https://gifna.who.int/countries/CAN/policies/111522 (accessed August 26, 2024).

49. World Health Organization. Chile: Front-of-Pack Labeling (FOPL) Policy. Global database on the Implementation of Food and Nutrition Action (GIFNA). (2016). Available at: https://gifna.who.int/countries/CHL/policies/43863 (accessed August 26, 2024).

50. World Health Organization. Colombia: Front-of-Pack Labeling (FOPL) Policy. Global database on the Implementation of Food-related Nutrition Action (GIFNA). (2021). Available at: https://gifna.who.int/countries/COL/policies/66482 (accessed August 26, 2024).

51. World health Organization. Ecuador: Front-of-Pack Labeling (FOPL) Policy. Global database on the Implementation of Food and Nutrition Action (GIFNA). (2014). Available at: https://gifna.who.int/countries/ECU/policies/22924 (accessed August 26, 2024).

52. World Health Organization. Mexico: Front-of-Pack Labeling (FOPL) Policy. Global database on the Implementation of Food-related Nutrition Action (GIFNA). (2020). Available at: https://gifna.who.int/countries/MEX/policies/43113 (accessed August 26, 2024).

53. World Health Organization. Peru: Front-of-Pack Labeling (FOPL) Policy. Global database on the Implementation of Food-related Nutrition Action (GIFNA). (2018). Available at: https://gifna.who.int/countries/PER/policies/43114 (accessed August 26, 2024).

54. World Health Organization. Uruguay: Front-of-Pack Labeling (FOPL) Policy. Global database on the Implementation of Food-related Nutrition Action (GIFNA). (2018). Available at: https://gifna.who.int/countries/URY/policies/36135 (accessed August 26, 2024).

55. World Health Organization. Venezuela: Front-of-Pack Labeling (FOPL) Policy. Global database on the Implementation of Food-related Nutrition Action (GIFNA). (2020). Available at: https://gifna.who.int/countries/VEN/policies/44361 (accessed August 26, 2024).

56. World Health Organization. Israel: Front-of-Pack Labeling (FOPL) Policy. Global database on the Implementation of Food-related Nutrition Action (GIFNA). (2017). Available at: https://gifna.who.int/countries/ISR/policies/43111 (accessed August 26, 2024).

57. World Health Organization. Belgium: Front-of-Pack Labeling (FOPL) Policy. Global database on the Implementation of Food-related Nutrition Action (GIFNA). (2019). Available at: https://gifna.who.int/countries/BEL/policies/41462 (accessed August 26, 2024).

58. World Health Organization. Croatia: Front-of-Pack Labeling (FOPL) Policy. Global database on the Implementation of Food-related Nutrition Action (GIFNA). (2017). Available at: https://gifna.who.int/countries/HRV/policies/42842 (accessed August 26, 2024).

59. World Health Organization. Denmark: Front-of-Pack Labeling (FOPL) Policy. Global database on the Implementation of Food-related Nutrition Action (GIFNA). (2009). Available at: https://gifna.who.int/countries/DNK/policies/22920 (accessed August 26, 2024).

60. World Health Organization. France: Front-of-Pack Labeling (FOPL) Policy. Global database on the Implementation of Food-related Nutrition Action (GIFNA). (2017). Available at: https://gifna.who.int/countries/FRA/policies/25376 (accessed August 26, 2024).

61. World Health Organization. Germany: Front-of-Pack Labeling (FOPL) Policy. Global database on the Implementation of Food-related Nutrition Action (GIFNA). (2020). Available at: https://gifna.who.int/countries/DEU/policies/43599 (accessed August 26, 2024).

62. World Health Organization. Iceland: Front-of-Pack Labeling (FOPL) Policy. Global database on the Implementation of Food-related Nutrition Action (GIFNA). (2015). Available at: https://gifna.who.int/countries/ISL/policies/36129 (accessed August 26, 2024).

63. World health Organization. Ireland: Front-of-Pack Labeling (FOPL) Policy. Global database on the Implementation of Food-related Nutrition Action (GIFNA). (2013). Available at: https://gifna.who.int/countries/GBR/policies/22935 (accessed August 26, 2024).

64. World Health organization. Lithuania: Front-of-Pack Labeling (FOPL) Policy. Global database on the Implementation of Food-related Nutrition Action (GIFNA). (2014). Available at: https://gifna.who.int/countries/LTU/policies/25739 (accessed August 26, 2024).

65. World Health Organization. Luxemburg: Front-of-Pack Labeling (FOPL) Policy. Global database on the Implementation of Food-related Nutrition Action (GIFNA). (2021). Available at: https://gifna.who.int/countries/LUX/policies/73544 (accessed August 26, 2024).

66. World Health Organization. Macedonia: Front-of-Pack Labeling (FOPL) Policy. Global database on the Implementation of Food-related Nutrition Action (GIFNA). (2016). Available at: https://gifna.who.int/countries/MKD/policies/8739 (accessed August 26, 2024).

67. World Health Organization. Norway: Front-of-Pack Labeling (FOPL) Policy. Global database on the Implementation of Food-related Nutrition Action (GIFNA). (2009). Available at: https://gifna.who.int/countries/NOR/policies/23012 (accessed August 26, 2024).

68. World Health Organization. Portugal: Front-of-Pack Labeling (FOPL) Policy. Global database on the Implementation of Food-related Nutrition Action (GIFNA). (2017). Available at: https://gifna.who.int/countries/PRT/policies/39764 (accessed August 26, 2024).

69. World health Organization. Russia: Front-of-Pack Labeling (FOPL) Policy. Global database on the Implementation of Food-related Nutrition Action (GIFNA). (2018). Available at: https://gifna.who.int/countries/RUS/policies/43601 (accessed August 26, 2024).

70. World Health Organization. Spain: Front-of-Pack Labeling (FOPL) Policy. Global database on the Implementation of Food-related Nutrition Action (GIFNA). (2021). Available at: https://gifna.who.int/countries/ESP/policies/77539 (accessed August 26, 2024).

71. World Health Organization. Sweden: Front-of-Pack Labeling (FOPL) Policy. Global database on the Implementation of Food-related Nutrition Action (GIFNA). (2009). Available at: https://gifna.who.int/countries/SWE/policies/23011 (accessed August 26, 2024).

72. World Health Organization. Switzerland: Front-of-Pack Labeling (FOPL) Policy. Global database on the Implementation of Food-related Nutrition Action (GIFNA). (2019). Available at: https://gifna.who.int/countries/CHE/policies/66486 (accessed August 26, 2024).

73. World Health Organization. United Kingdom: Front-of-Pack Labeling (FOPL) Policy. Global database on the Implementation of Food-related Nutrition Action (GIFNA). (2013). Available at: https://gifna.who.int/countries/GBR/policies/22935 (accessed August 26, 2024).

74. World Health Organization. Iran: Front-of-Pack Labeling (FOPL) Policy. Global database on the Implementation of Food-related Nutrition Action (GIFNA). (2014). Available at: https://gifna.who.int/countries/IRN/policies/42843 (accessed August 26, 2024).

75. World health Organization. Saudi Arabia: Front-of-Pack Labeling (FOPL) Policy. Global database on the Implementation of Food-related Nutrition Action (GIFNA). (2018). Available at: https://gifna.who.int/countries/SAU/policies/53608 (accessed August 26, 2024).

76. World Health Organization. United Arab Amirates: Front-of-Pack Labeling (FOPL) Policy. Global database on the Implementation of Food-related Nutrition Action (GIFNA). (2019). Available at: https://gifna.who.int/countries/ARE/policies/39386 (accessed August 26, 2024).

77. World Health Organization. Sri Lanka: Front-of-Pack Labeling (FOPL) Policy. Global database on the Implementation of Food-related Nutrition Action (GIFNA). (2019). Available at: https://gifna.who.int/countries/LKA/policies/44844 (accessed August 26, 2024).

78. World Health Organization. Thailand: Front-of-Pack Labeling (FOPL) Policy. Global database on the Implementation of Food-related Nutrition Action (GIFNA). Guideline Daily Amounts (GDA). (2016). Available at: https://gifna.who.int/countries/THA/policies/25401 (accessed August 26, 2024).

79. World Health Organization. Indonesia: Front-of-Pack Labeling (FOPL) Policy. Global database on the Implementation of Food-related Nutrition Action (GIFNA). (2013). Available at: https://gifna.who.int/countries/IDN/policies/26167 (accessed August 26, 2024).

80. World Health Organization. Thailand: Front-of-Pack Labeling (FOPL) Policy. Global database on the Implementation of Food-related Nutrition Action (GIFNA). Healthier Choice Logo. (2016). Available at: https://gifna.who.int/countries/THA/policies/82176 (accessed August 26, 2024).

81. World Health Organization. Singapore: Front-of-Pack Labeling (FOPL) Policy. Global database on the Implementation of Food-related Nutrition Action (GIFNA). (2021). Available at: https://gifna.who.int/countries/SGP/policies/79838 (accessed August 26, 2024).

82. World Health Organization. Australia: Front-of-Pack Labeling (FOPL) Policy. Global database on the Implementation of Food-related Nutrition Action (GIFNA). (2013). Available at: https://gifna.who.int/countries/AUS/policies/22919 (accessed August 26, 2024).

83. World Health Organization. Brunei: Front-of-Pack Labeling (FOPL) Policy. Global database on the Implementation of Food-related Nutrition Action (GIFNA). (2016). Available at: https://gifna.who.int/countries/BRN/policies/25367 (accessed August 26, 2024).

84. World Health Organization. Malaysia: Front-of-Pack Labeling (FOPL) Policy. Global database on the Implementation of Food-related Nutrition Action (GIFNA). (2017). Available at: https://gifna.who.int/countries/MYS/policies/53609 (accessed August 26, 2024).

85. World Health Organization. New Zealand: Front-of-Pack Labeling (FOPL) Policy. Global database on the Implementation of Food-related Nutrition Action (GIFNA). (2013). Available at: https://gifna.who.int/countries/NZL/policies/22919 (accessed August 26, 2024).

86. World Health Organization. Philipines: Front-of-Pack Labeling (FOPL) Policy. Global database on the Implementation of Food-related Nutrition Action (GIFNA). (2012). Available at: https://gifna.who.int/countries/PHL/policies/25387 (accessed August 26, 2024).

87. World Health Organization. Singapore: Front-of-Pack Labeling (FOPL) Policy. Global database on the Implementation of Food-related Nutrition Action (GIFNA). Healthier Choice Symbol Programme. (1998). Available at: https://gifna.who.int/countries/SGP/policies/8196 (accessed August 26, 2024).

88. World Health Organization. South Korea: Front-of-Pack Labeling (FOPL) Policy. Global database on the Implementation of Food-related Nutrition Action (GIFNA). (2022). Available at: https://gifna.who.int/countries/KOR/policies/77548 (accessed August 26, 2024).

Keywords: nutrition labeling, packaged food, front-of-pack labeling, labeling policy, food labeling

Citation: Afroza U, Abrar AK, Nowar A, Sobhan SMM, Ide N and Choudhury SR (2024) Global overview of government-endorsed nutrition labeling policies of packaged foods: a document review. Front. Public Health 12:1426639. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1426639

Received: 01 May 2024; Accepted: 08 October 2024;

Published: 08 November 2024.

Edited by:

Catalina Medina, National Institute of Public Health, MexicoReviewed by:

Alexandra Kalbus, University of London, United KingdomLuz M. Sanchez Romero, Georgetown University, United States

Copyright © 2024 Afroza, Abrar, Nowar, Sobhan, Ide and Choudhury. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ummay Afroza, YWZyb3phdGFtYW5uYS5iZEBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Ummay Afroza

Ummay Afroza Ahmad Khairul Abrar

Ahmad Khairul Abrar Abira Nowar

Abira Nowar Sheikh Mohammad Mahbubus Sobhan

Sheikh Mohammad Mahbubus Sobhan Nicole Ide

Nicole Ide Sohel Reza Choudhury

Sohel Reza Choudhury