Corrigendum: A chain mediation model on organizational support and turnover intention among healthcare workers in Guangdong province, China

- 1School of Public Health and Management, Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, Guangzhou, China

- 2School of Public Health, Guangdong Pharmaceutical University, Guangzhou, China

- 3Centre for Research on Health Economics and Health Promotion, Guangdong Pharmaceutical University, Guangzhou, China

- 4School of Psychology and Public Health, La Trobe University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

- 5Maoming Maternal and Child Health Hospital, Maoming, China

Introduction: The outbreak of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 pandemic has presented significant difficulties for healthcare workers worldwide, resulting in a higher tendency to quit their jobs. This study aims to investigate the correlation between organizational support, work-family-self balance, job satisfaction, and turnover intention of healthcare professionals in China’s public hospitals.

Methods: A cross-sectional survey was conducted on 5,434 health workers recruited from 15 public hospitals in Foshan municipality in China’s Guangdong province. The survey was measured by organizational support, work-family-self balance, job satisfaction, and turnover intention using a five-point Likert scale. The association between organizational support, work-family-self balance, job satisfaction, and turnover intention was investigated using Pearson correlation analysis and mediation analysis through the PROCESS macro (Model 6).

Results: Organizational support indirectly affected turnover intention through three pathways: the mediating role of work-family-self balance, job satisfaction, and the chain mediating role of both work-family-self balance and job satisfaction.

Conclusion: Health administrators and relevant government sectors should provide sufficient organizational support, enhance work-family-self balance and job satisfaction among healthcare workers, and consequently reduce their turnover intentions.

1 Introduction

The worldwide healthcare workforce has been enduring labor shortages, exacerbated by several factors, including heavy workloads, unpredictable work environments, the possibility of infection, the emotional toll of witnessing suffering and death, and the psychological strain stemming from the widespread COVID−19 pandemic (1, 2). These issues may lead to the dissatisfaction of healthcare workers and increase their likelihood of leaving their jobs (3). Turnover intention refers to the possibility that an employee willingly leaves his or her job in the future, which is a crucial predictor of turnover behavior (4, 5). Prior studies found that healthcare workers’ pooled prevalence of intention to leave was 30.4% in China (6) and 83% in Ethiopia (7). Several studies indicated that turnover intention among healthcare workers was high in Qatar (8) and Singapore (9) during the COVID−19 pandemic. However, a high turnover intention rate is not conducive to the continuity of patient care and the development of the healthcare system (8, 10).

Studies showed that different categories of healthcare workers had different intentions to leave. Global systematic reviews reported that general practitioners had a 47% prevalence of turnover intention (11), whereas pharmacists ranged from 13% to 61.2% (12). Other studies demonstrated that 43% of advanced practice nurses (13) and 39% of midwives had considered quitting their jobs (14). Additionally, 35 of 43 studies that examined healthcare workers’ turnover intention during the COVID-19 pandemic were focused on nurses, according to a global systematic review (15).

Turnover intention is affected by complex factors, including personal, organizational, and external environmental factors (16, 17). To examine the intrinsic motivation of turnover intention, various motivational models of turnover intention were proposed. The representative models are the Mobley model (18), the Steers and Mowday model (19), and the Price-Mueller model (20). One of the most influential models of employee turnover intention is the Price-Muller model. Based on expectancy theory, the model assumes that employees with a work environment that meets their values will be more satisfied, committed, and less likely to quit (21, 22). Furthermore, Price contends that when employees’ dissatisfactions exceed satisfactions, it puts them in a “costly” situation and drives them to look for other jobs (20). The model divides the factors influencing employee turnover into four categories: endogenous (e.g. job satisfaction and organizational commitment), structural (e.g. autonomy, pay and career), individual (e.g. training and affectivity), and environmental (e.g. opportunity and kinship responsibility).

To develop a more comprehensive turnover model, several studies have concentrated on identifying potential moderators of the association between organizational support and turnover intentions. Research indicates that organizational commitment and job satisfaction. mediated most associations between organizational support and turnover intention. A study identified that affective commitment acted as a mediating factor in the negative correlation between organizational support and turnover intention (23). Organizational concern and support may help healthcare workers foster their sense of belonging, leading to a high affective commitment and mitigating their turnover intention (23). Another study on 341 nurses revealed that job satisfaction mediated the negative relationship between organizational support and turnover intention (24). Healthcare workers who perceive sufficient support from their organizations are likely to work more effectively and efficiently, which increases job satisfaction and, in turn, decreases their intention to leave (25, 26).

Existing studies have explored the antecedents of healthcare workers’ intention to leave their jobs, mainly focusing on job characteristics, organizational variables, and personal factors, but much less is known about work-family-self balance. Moreover, the role of work-family-self balance in the relationship between organizational support and turnover intention of healthcare workers is little understood, and studies explaining the mechanism underlying the association between organizational support and turnover intention among healthcare workers were inadequate. In addition, during the COVID-19 epidemic, many studies of turnover intention were conducted on nurses rather than all healthcare workers. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the association between organizational support, work-family-self balance, job satisfaction, and turnover intention among healthcare workers in 15 public hospitals in Nanhai district, Foshan municipality, Guangdong province, China. We also aim to determine whether there is a connection between work-family-self balance and job satisfaction when both are considered to be the mediating role.

1.1 Literature review and hypothesis development

1.1.1 Organizational support and turnover intention

Organizational support is typically assessed through a subjective perspective, capturing employees’ perceptions of how much the organization cares about their well-being and values their contributions (27). Sufficient organizational support has the potential to increase the sense of self-identity, belonging, responsibility, and work engagement of medical staff, thereby improving the relationship with their organization and boosting their confidence and skills in providing care for patients (28–31). In addition, organizational support was found to be a predictor of turnover intention and to have a negative relationship with it in earlier research (32). While low levels of organizational support result in higher turnover intention, employees who felt that their organizations provided adequate support could maximally mitigate their desire to leave and encourage them to stay (23, 33). Therefore, we propose the first hypothesis:

H1: Organizational support will be negatively associated with turnover intention.

1.1.2 Work-family-self balance, organizational support, and turnover intention

“Satisfaction and good functioning at work and home, with a minimum of role conflict” was the term used to describe work-family balance (34). Work-life balance was defined as the ability of employees to work and fulfill their responsibilities to family and others outside of work (35). Work-family-self balance is the state of harmony among work, family, and self, involving physical and mental health (36). Previous studies showed that the COVID-19 pandemic increased healthcare workers’ workload and working hours, leading to longer shifts, disturbed sleep patterns, and fewer social and family activities (37, 38). According to the spillover and crossover theories, healthcare workers’ negative experiences, feelings, and attitudes at work would carry over into their homes and personal lives (39, 40). Research indicated that work-family balance had an impact on psychological outcomes, such as job anxiety, strain, and turnover intention (41, 42). A recent study found that four out of 10 healthcare workers did not balance their work with their non-work and community roles, negatively impacting their sense of personal and professional belonging (43) and potentially increasing turnover intention. However, the spillover effects and the crossover effects indicated that healthcare workers who felt they had adequate organizational support, including instrumental and emotional support (44), will get more stimulated, inspired, and have a positive experience at work, which they will carry over and transfer to their family and personal lives (39, 40). For example, they will interact with their families with greater joy, enthusiasm, and confidence (45), contributing to a more harmonious status among healthcare workers’ work and family, thereby reducing the likelihood of leaving their jobs. Existing research demonstrated that organizational support had a significant and positive effect on the work-life balance, that work-family balance and work-life balance were negatively associated with turnover intention, and that work-life balance may play a mediating role of organizational support and turnover intention (46). Based on these findings, we propose the second hypothesis:

H2: Work-family-self balance mediates the relationship between organizational support and turnover intention.

1.1.3 Job satisfaction, organizational support, and turnover intention

Job satisfaction refers to an individual’s feelings about her/his job (47), and it is concerned with individual productivity, relationships with coworkers, physical and mental health, and life satisfaction (48). Furthermore, the quality of healthcare is influenced by the job satisfaction of healthcare workers (49). High job satisfaction may lead to increased productivity and creativity among healthcare personnel (50). In contrast, job dissatisfaction may result in adverse effects, including turnover and absenteeism, increased work accidents, and impairment to one’s mental and physical health (51). Additionally, job satisfaction was the most significant antecedent variable for predicting turnover intention (52). The extant research suggested that organizational support could increase job satisfaction and improve employees’ positive attitudes at work (53). Strongly perceived organizational support would result in high emotional connection and commitment to the organization (54), suggesting that employees are more likely to be content with their jobs rather than leave them, according to social exchange theory (25). In other words, organizational support would lower the intention to leave by improving job satisfaction (24). Therefore, we propose the third hypothesis:

H3: Job satisfaction mediates the relationship between organizational support and turnover intention.

1.1.4 Work-family-self balance, job satisfaction, organizational support, and turnover intention

Based on the above theories, work-family-self balance and job satisfaction may mediate the correlation between organizational support and turnover intention of healthcare workers. Previous studies found that work-family balance and work-life balance were linked to increased job satisfaction and organizational performance (55–59). Work-family-self balance may have an initial impact on the association between organizational support and turnover intention, followed by job satisfaction. Then, we propose the fourth hypothesis:

H4: Work-family-self balance and job satisfaction play a chain mediating role in the relationship between organizational support and turnover intention.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study design and participants

A cross-sectional survey of hospital employees was conducted from 10 October 2021 to 11 January 2022. Study participants were recruited from 15 public hospitals (two primary hospitals with 20–99 beds, six secondary hospitals with 100–499 beds, and seven tertiary hospitals with ≥500 beds) in Nanhai District of Foshan municipality, Guangdong province, China. Eligible participants were contract staff of all professions on duty during the survey. Employees on leave at the time of the survey, retired personnel, and casual staff were not included.

A stratified proportional to size sampling method was used to recruit study participants. In Nanhai, the tertiary hospitals employed 6,877 professional healthcare workers, while the secondary hospitals employed 5,234 and the primary hospitals employed 572. Registered nurses made up about 49.68% of the skilled health workforce in Foshan. We set a quota for each participating hospital to recruit at least 220 participants. The sample size was estimated based on a sample size estimation for one-sample means with α = 0.05, Z1-α/2 = 1.96, estimate of σ = 1.31, allowed error δ = 0.05, and 20% non-response rate was considered. The values of σ were derived from the results of the Fourth National Health Service Survey in Guangdong Province (60). Each professional group received a quota for each participating hospital based on size.

2.2 Data collection

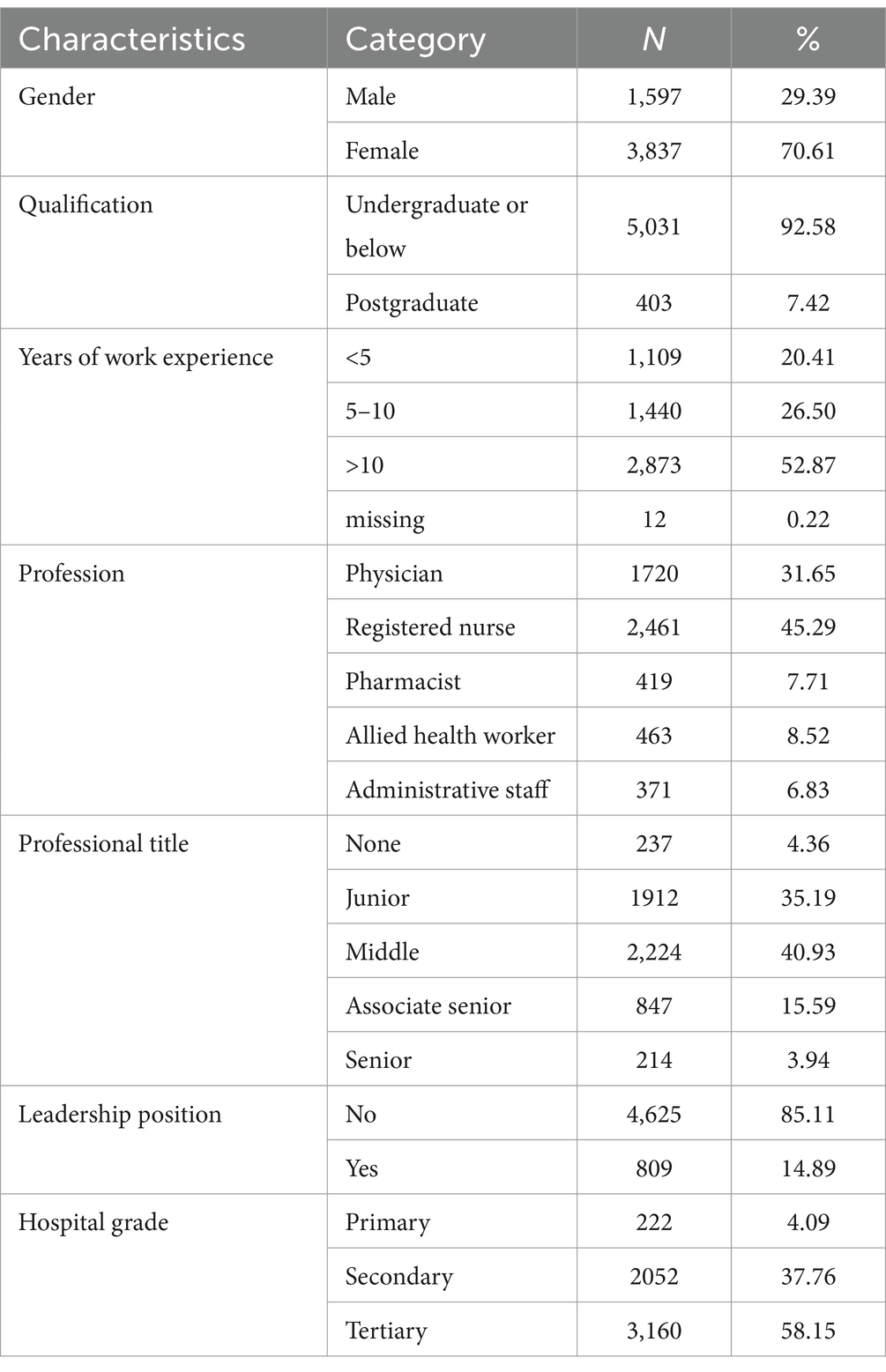

The survey was performed via an online platform. Each hospital provided a demographic list of healthcare professionals, which was used to conduct stratified sampling based on three levels: profession, professional title, and gender. The phone numbers of the selected healthcare staff were provided by each hospital’s personnel department. The chosen healthcare workers were invited to complete the questionnaire, along with the respondent’s informed consent and a link to the questionnaire. Participation in the survey was voluntary and anonymous. A total of 5,702 questionnaires were distributed, and 5,434 (95.30%) of them were completed: 31.65% from physicians (n = 1,720), 45.29% from registered nurses (n = 2,461), 7.71% from pharmacists (n = 419), 8.52% from allied health workers (n = 463), and 6.83% from administrative staff (n = 371).

Respondents were invited to self-complete a questionnaire that included six close-ended questions about study participants’ sociodemographic and job characteristics and 32 close-ended questions for measuring organizational support, work-family-self balance, job satisfaction, and turnover intention. On average, each survey took about 4.27 minutes. We excluded incomplete and non-conforming questionnaires for quality control (less than 60 s of response time) (61).

2.3 Measures

2.3.1 Organizational support

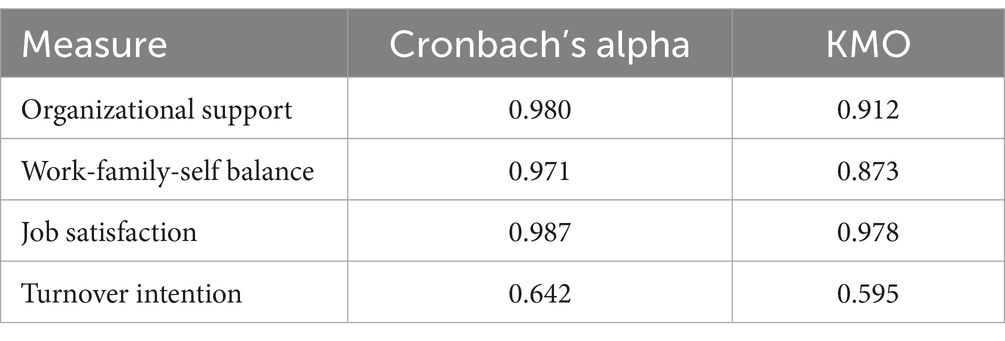

Organizational support was measured by a 5-item scale developed by Eisenberger et al. (6 items) (62). Each item was rated on a five-point Likert scale, with 1 representing “strongly disagree” and 5 representing “strongly agree.” The Cronbach’s alpha for organizational support scale was 0.980 in this study (Table 1). A summed score was calculated, with a higher score indicating higher levels of organizational support.

Table 1. The Cronbach’s alpha and KMO value of organizational support, work-family-self balance, job satisfaction, and turnover intention (N = 5,434).

2.3.2 Work-family-self balance

Work-family-self balance was measured by a 4-item scale developed by Xiao and Luo (4 items) (36). Each item was rated on a five-point Likert scale, with 1 representing “strongly disagree” and 5 representing “strongly agree.” The Cronbach’s alpha for work-family-self balance scale was 0.971 in this study (Table 1). A summed score was calculated, with a higher score indicating higher levels of work-family-self balance.

2.3.3 Job satisfaction

Job satisfaction was measured using an 18-item scale developed by Zhang and Gu (18 items) (63). Respondents rated each item on a five-point Likert scale, with 1 representing “strongly disagree” and 5 representing “strongly agree.” The Cronbach’s alpha and Split-half reliability for job satisfaction scale was 0.987 and 0.973 (Table 1). A summed score was calculated for data analysis, with a higher score indicating higher levels of job satisfaction.

2.3.4 Turnover intention

Turnover intention was measured by a 5-item scale adapted from the scale (items 32, 33, 34) developed by Mobley et al. (64) and the scale (items 35, 36) developed by Cammann (65). Each item was rated on a five-point Likert scale, with 1 representing “strongly disagree” and 5 representing “strongly agree.” The Cronbach’s alpha for turnover intention scale was 0.642 in this study (Table 1). A summed score was calculated, with a higher score indicating higher levels of turnover intention.

2.3.5 Covariates

The covariates of this study included sociodemographic (gender, educational attainment) and job characteristics (profession, contract, professional title, position, and hospital grade). Empirical evidence shows that these characteristics are associated with job satisfaction and turnover intention (66, 67).

2.4 Statistical analysis

Data were entered into Excel and analyzed with SPSS 25.0 for Windows and PROCESS v4.0 macro (model 6) developed by Hayes (68). Respondents’ sociodemographic and job characteristics were described using frequency distributions for categorical and ordinal variables and mean values and standard deviations for continuous variables. Pearson correlation analysis was used to investigate the correlations between organizational support, work-family-self balance, job satisfaction, and turnover intention. Regression models were established to determine the mediating effect of work-family-self balance and job satisfaction on the association between organizational support and turnover intention. Four models were established: model one tested the effect of organizational support on turnover intention; model two tested the impact of organizational support on work-family-self balance; model three tested the mediating effect of work-family-self balance on the association between organization support and job satisfaction; model four examined the mediating effects of work-family-self balance and job satisfaction on the correlation between organizational support and turnover intention, as well as the chain mediating effect of work-family-self balance and job satisfaction on the relationship between organizational support and turnover intention. Seven covariates (gender, academic qualification, work experience, profession, professional title, leadership position, and hospital grade) were controlled in all models. Indirect effects were computed using a bias-corrected bootstrapping procedure. If the 95% confidence interval (CI) did not include zero, it indicated that the mediation effect was significant. Missing values were handled using a pairwise deletion approach. A two-sided p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3 Results

3.1 Characteristics of study participants

The vast majority were female (70.61%), do not have a postgraduate qualification (92.58%), held a middle professional title (40.93%), and were not in a leadership position (85.11%). Most worked in a tertiary hospital (58.15%) and had over 10 years of work experience (52.87%). Registered nurses comprised 45.29% of the study population, followed by physicians (31.65%; Table 2).

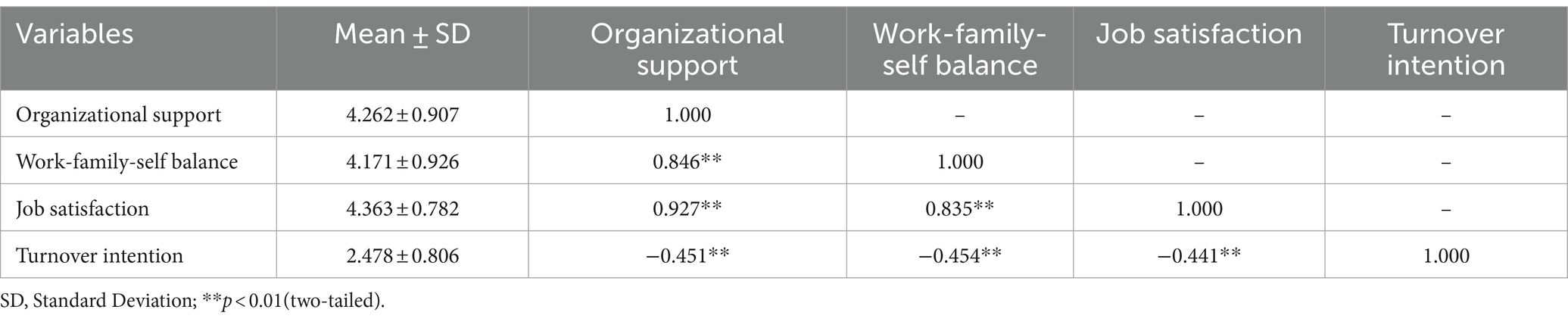

3.2 Organizational support, work-family-self balance, job satisfaction, and turnover intention

Respondents reported a mean score of 4.262 (SD = 0.907), 4.171(SD = 0.926), 4.363 (SD = 0.782), and 2.478 (SD = 0.806) for organizational support, work-family-self balance, job satisfaction, and turnover intention, respectively. Organizational support, work-family-self balance, job satisfaction, and turnover intention were all moderately or strongly correlated, with correlation coefficients ranging from −0.454 to 0.927 (Table 3).

Table 3. Descriptive statistic and Pearson correlations among organizational support, work-family-self balance, job satisfaction, and turnover intention.

3.3 Results of regression modeling and mediating effects

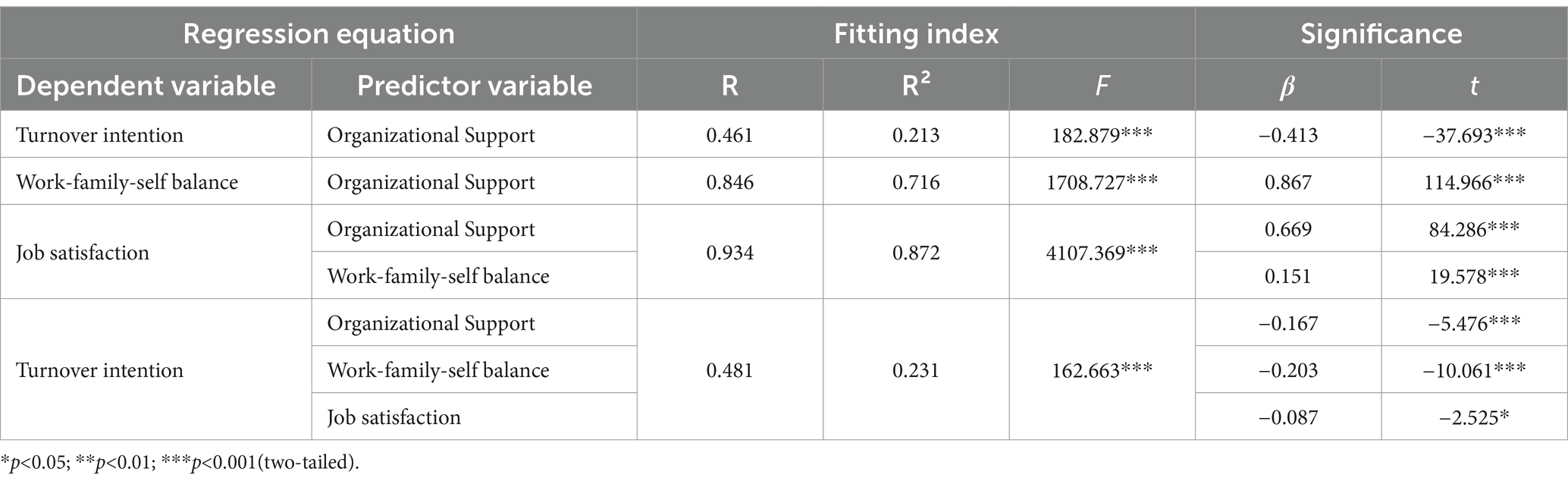

Respondents with higher organizational support (β = −0.413, p < 0.001) had lower levels of turnover intention (Model 1 in Table 4). Hypothesis 1 is confirmed. Respondents with higher organizational support (β = 0.867, p < 0.001) had higher levels of work-family-self balance (Model 2 in Table 4). Respondents with higher organizational support (β = 0.669, p < 0.001) and higher work-family-self balance (β = 0.151, p < 0.001) had higher levels of job satisfaction (Model 3 in Table 4). Respondents with higher organizational support (β = −0.167, p < 0.001), higher work-family-self balance (β = −0.203, p < 0.001), and higher job satisfaction (β = −0.087, p < 0.05) had lower levels of turnover intention (Model 4 in Table 4).

Table 4. Regression analysis of the relationship between organizational support and turnover intention (N=5,422).

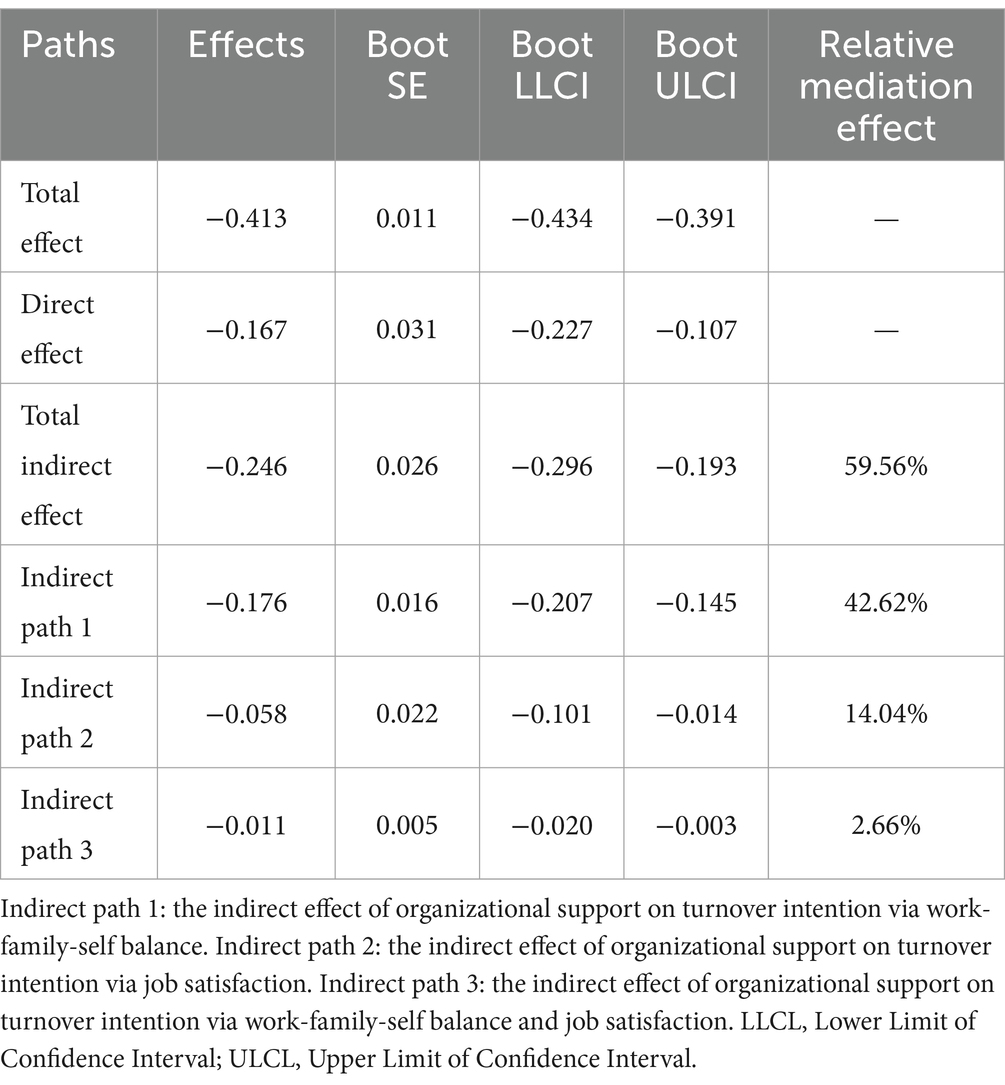

Work-family-self balance partially mediated the relationship between organizational support and turnover intention: the indirect effect accounted for 42.62% of the total effect. Job satisfaction partially mediated the relationship between organizational support and turnover intention, with the indirect effect accounting for 14.04% of the total effect. According to the chain mediation that described the mediating effects of work-family-self balance and job satisfaction between organizational support and turnover intention, the indirect impact contributed to 2.66% of the total effect (Table 5). Hypotheses 2, 3, and 4 are confirmed.

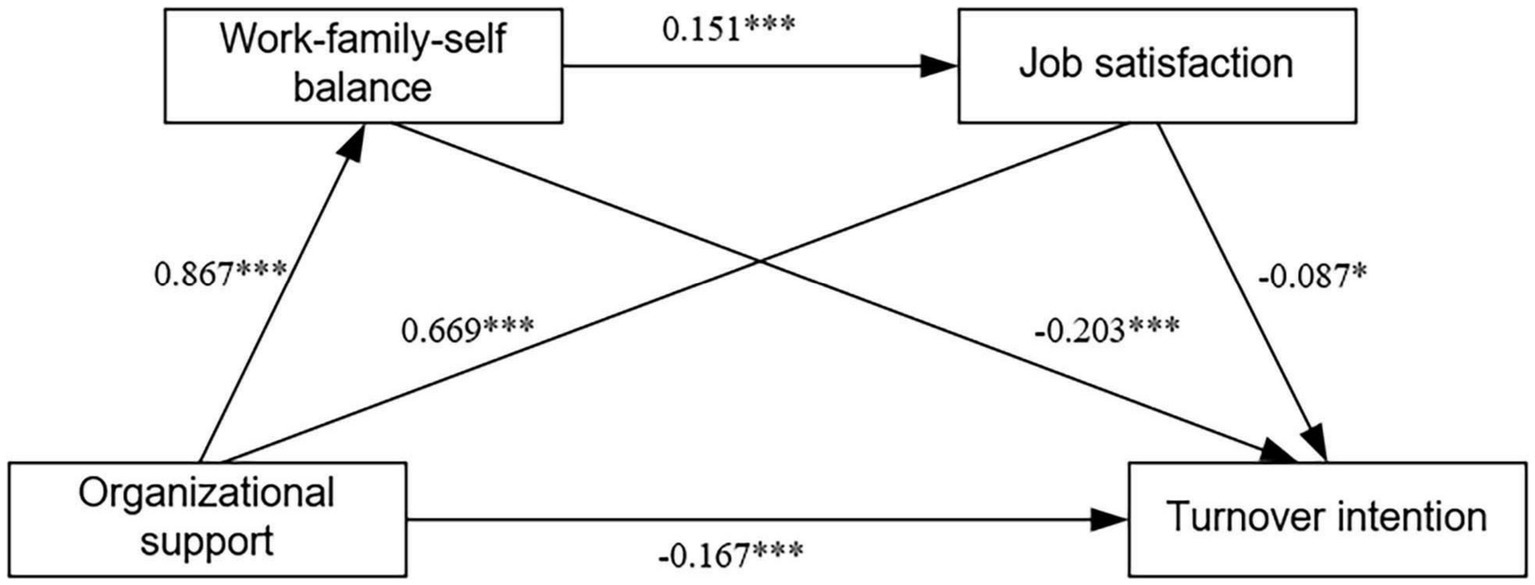

Figure 1 illustrates how organizational support can indirectly predict turnover intention via the single mediating effect of work-family-self balance and job satisfaction and the chain mediating effect of work-family-self balance and job satisfaction. The mediating effect consists of three indirect effects: Path 1: organizational support → work-family-self balance → turnover intention. Path 2: organizational support → job satisfaction → turnover intention. Path 3: organizational support → work-family-self balance → job satisfaction → turnover intention. All three indirect impacts are significant.

Figure 1. The chain mediation model. The chain mediating role of organizational support and turnover intention through work-family-self balance and job satisfaction. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001(two-tailed).

4 Discussion

This study investigated the effect of organizational support on healthcare workers’ turnover intention by collecting data from healthcare workers in Guangdong province, China, during the COVID-19 pandemic. We explored the chain mediating effects of work-family-self balance and job satisfaction on organizational support and turnover intention among healthcare workers. This is the first study to examine the relationship between organizational support, work-family-self balance, job satisfaction, and turnover intention in China. Additionally, this study contributed to the theoretical development and applications of turnover intention.

The study found that organizational support, work-family-self balance, and job satisfaction had a direct impact on turnover intention, which is consistent with prior research. An earlier study suggested that certain supportive practices, such as participation in decision-making and job rewards, could help to reduce employee turnover intention (32). A study revealed that healthcare workers who struggled to balance their work and family lives were more likely to experience job anxiety, which led to a greater intention to leave their jobs (69). Another study of primary care doctors in China indicated that individuals under age 30 were more likely to consider leaving their positions in search of better career opportunities and being dissatisfied or negative about their current job prospects (70). Organizational support, work-family-self balance, and job satisfaction directly affect turnover intention since they are linked to an employee’s career and psychological well-being.

This current study found that the associations between organizational support and turnover intention among healthcare workers are mediated by work-family-self balance and job satisfaction, which is consistent with previous studies (46, 71). Furthermore, this study investigated a chain link between organizational support, work-family-self balance, job satisfaction, and turnover intention. These findings suggest that organizational support may contribute to work-family-self balance and job satisfaction and that work-family-self balance may contribute to job satisfaction. Healthcare workers who receive more organizational support may feel respected and valued by the organization, promoting positive emotions in the workplace, such as a sense of security and belonging (72). According to social exchange theory (25), when healthcare workers feel positive emotions and attitudes at work, their job satisfaction is considerably increased. Meanwhile, adequate organizational support is necessary for healthcare workers to balance the demands of their professional work, family responsibilities (45), and personal lives (73, 74) while also improving their mental health (75–78). Healthcare workers who are well-supported by their organizations are more productive, creative, and happy. Healthcare workers’ increased work productivity and creativity have the potential to alleviate the stress caused by heavy workloads and strict work hour pressures, reducing conflict between work, family, and themselves and facilitating the achievement of their desired state of work-family-self balance (69, 79). In addition, implementing work-life balance practices in hospitals could help healthcare workers maintain a balance between their professional and personal lives, enhancing their performance at work and increasing their job satisfaction (80). Organizational support directly affects work-family-self balance, job satisfaction, and turnover intention, as well as indirectly affects job satisfaction and turnover intention. This emphasizes the importance of organizational support in healthcare workers’ well-being and turnover decision-making, highlighting the need for organizations to adopt supportive measures. To improve organizational support for healthcare workers, creating a supportive work environment (81) and formulating organizational policies and human resource initiatives (82) may facilitate balancing work demands outside of the workplace, such as encouraging organizational trust and positive organizational climate (44), providing training and development opportunities, and establishing family supportive policies (27). Work-family-self balance also has a substantial impact on turnover intention, indicating that healthcare workers’ needs outside of work should be addressed and work-family-self-balance initiatives implemented. Providing benefits assists healthcare workers in achieving a better work-family-self balance and improving job performance by expanding health insurance coverage for healthcare workers and their dependents and introducing programs or services to promote their physical well-being and fitness (83).

The study explores the role of work-family-self balance and job satisfaction as the internal mechanisms that link organizational support to turnover intention among healthcare workers, thereby enriching the understanding of how organizational support influences turnover intention and emphasizing the importance of organizational support in mitigating turnover intention. The findings of this study provide a foundation for further research to understand the complexity and multidimensionality of healthcare workers’ turnover intention. Moreover, this study has important implications for health and hospital administrators, indicating that strengthening organizational support levels could facilitate achieving work-family self-balance, enhance job satisfaction, and lower turnover intention. The results of this study offer initial evidence that preventive intervention approaches should be prioritized to improve work-family selfbalance and job satisfaction among healthcare workers. There are some limitations in this study. First, it is not ideal that Cronbach’s coefficient of turnover intention scale was below 0.7. We will try to find ways to improve the reliability of the results in further research. Second, the sample size for the two primary hospitals did not reach 220 because of the small number of staff in the primary hospitals. Third, this study did not measure demographic characteristics of age. Finally, the generalization of this study’s findings needs to be tested and verified further, as all participants come from the same district.

5 Conclusion

The study showed that organizational support indirectly predicts the turnover intention of healthcare workers through the mediating effects of work-family-self balance, job satisfaction, and the chain mediating effect between work-family-self balance and job satisfaction. This suggests that health administrators and relevant government sectors should be reminded of the significance of providing organizational support. They should enhance healthcare workers’ work-family-self balance, boost their job satisfaction, and decrease their intention to leave.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee of Guangdong Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

YC: Formal analysis, Validation, Writing – original draft, Resources. PX: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. CL: Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Supervision. CY: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Resources, Data curation. QZ: Data curation, Investigation, Validation, Writing – original draft. BL: Data curation, Investigation, Validation, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 72074057).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to sincerely thank all the respondents who participated in this study, as well as the support given by Huanru Chen and Jianhua Huang of the Nanhai District Hospital Management Center in Foshan municipality.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

COVID-19, Coronavirus Disease 2019

References

1. Alharbi, J, Jackson, D, and Usher, K. The potential for COVID-19 to contribute to compassion fatigue in critical care nurses. J Clin Nurs. (2020) 29:2762–4. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15314

3. Labrague, LJ, and Santos, JAA. Fear of COVID-19, psychological distress, work satisfaction and turnover intention among frontline nurses. J Nurs Manag. (2021) 29:395–403. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13168

4. March, JG, and Simon, HA. Organizations. 2. ed., repr ed. Cambridge, Mass: Blackwell Business (1995). 287 p.

5. Chao, M-C, Jou, R-C, Liao, C-C, and Kuo, C-W. Workplace stress, job satisfaction, job performance, and turnover intention of health Care Workers in Rural Taiwan. Asia Pac J Public Health. (2015) 27:NP1827–36. doi: 10.1177/1010539513506604

6. He, R, Liu, J, Zhang, W-H, Zhu, B, Zhang, N, and Mao, Y. Turnover intention among primary health workers in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. (2020) 10:e037117. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037117

7. Nenko, G, and Vata, P. Assessment of health professionals’ intention for turnover and determinant factors in Yirgalem and Hawassa referral hospitals, southern Ethiopia. Int J Develop Res. (2014) 4:2–4.

8. Azizi, MR, Atlasi, R, Ziapour, A, Abbas, J, and Naemi, R. Innovative human resource management strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic narrative review approach. Heliyon. (2021) 7:e07233. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07233

9. Tan, C . More healthcare workers in S’pore quit amid growing fatigue as Covid-19 drags on. Straits Times. (2021)

10. Hou, H, Pei, Y, Yang, Y, Lu, L, Yan, W, Gao, X, et al. Factors associated with turnover intention among healthcare workers during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in China. RMHP. (2021) 14:4953–65. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S318106

11. Shen, X, Jiang, H, Xu, H, Ye, J, Lv, C, Lu, Z, et al. The global prevalence of turnover intention among general practitioners: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Fam Pract. (2020) 21:246–10. doi: 10.1186/s12875-020-01309-4

12. Thin, SM, Chongmelaxme, B, Watcharadamrongkun, S, Kanjanarach, T, Sorofman, BA, and Kittisopee, T. A systematic review on pharmacists’ turnover and turnover intention. Res Soc Adm Pharm. (2022) 18:3884–94. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2022.05.014

13. Wood, E, King, R, Senek, M, Robertson, S, Taylor, B, Tod, A, et al. UK advanced practice nurses’ experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic: a mixed-methods cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. (2021) 11:e044139. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-044139

14. Muluneh, MD, Moges, G, Abebe, S, Hailu, Y, Makonnen, M, and Stulz, V. Midwives’ job satisfaction and intention to leave their current position in developing regions of Ethiopia. Women Birth. (2022) 35:38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2021.02.002

15. Poon, Y-SR, Lin, YP, Griffiths, P, Yong, KK, Seah, B, and Liaw, SY. A global overview of healthcare workers’ turnover intention amid COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review with future directions. Hum Resour Health. (2022) 20:70. doi: 10.1186/s12960-022-00764-7

16. Muchinsky, PM, and Morrow, PC. A multidisciplinary model of voluntary employee turnover. J Vocat Behav. (1980) 17:263–90. doi: 10.1016/0001-8791(80)90022-6

17. Zeffane, RM . Understanding employee turnover: the need for a contingency approach. Int J Manpow. (1994) 15:22–37. doi: 10.1108/01437729410074182

18. Mobley, WH . Intermediate linkages in the relationship between job satisfaction and employee turnover. J Appl Psychol. (1977) 62:237–40. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.62.2.237

19. Steers, RM, and Mowday, RT. Employee turnover and post-decision accommodation processes. Oregon: Graduate School of Management, University of Oregon (1979).

20. Price, JL . Reflections on the determinants of voluntary turnover. Int J Manpow. (2001) 22:600–24. doi: 10.1108/EUM0000000006233

21. Gurney, CA, Mueller, CW, and Price, JL. Job satisfaction and organizational attachment of nurses holding doctoral degrees. Nurs Res. (1997) 46:163–71. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199705000-00007

22. Kim, S-W, Price, JL, Mueller, CW, and Watson, TW. The determinants of career intent among physicians at a US air force hospital. Hum Relat. (1996) 49:947–76. doi: 10.1177/001872679604900704

23. Purnamawati, ND, and Purba, DE. How does support by the organization decrease Employee’s intention to leave? Jurnal Ilmu Perilaku. (2019) 2:61–74. doi: 10.25077/jip.2.2.61-74.2018

24. Sharif, SP, Bolt, EET, Ahadzadeh, AS, Turner, JJ, and Nia, HS. Organisational support and turnover intentions: a moderated mediation approach. Nurs Open. (2021) 8:3606–15. doi: 10.1002/nop2.911

26. Chen, G, Ployhart, RE, Thomas, HC, Anderson, N, and Bliese, PD. The power of momentum: a new model of dynamic relationships between job satisfaction change and turnover intentions. Acad Manag J. (2011) 54:159–81. doi: 10.5465/amj.2011.59215089

27. Kurtessis, JN, Eisenberger, R, Ford, MT, Buffardi, LC, Stewart, KA, and Adis, CS. Perceived organizational support: a Meta-analytic evaluation of organizational support theory. J Manag. (2017) 43:1854–84. doi: 10.1177/0149206315575554

28. Cropanzano, R, Howes, JC, Grandey, AA, and Toth, P. The relationship of organizational politics and support to work behaviors, attitudes, and stress. J Organ Behav. (1997) 18:159–80. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1379(199703)18:2<159::AID-JOB795>3.0.CO;2-D

29. Stinglhamber, F, and Vandenberghe, C. Organizations and supervisors as sources of support and targets of commitment: a longitudinal study. J Organ Behav. (2003) 24:251–70. doi: 10.1002/job.192

30. Li, Z, Liu, J, Li, H, Huang, Y, and Xi, X. Primary healthcare pharmacists’ perceived organizational support and turnover intention: do gender differences exist? PRBM. (2023) 16:1181–93. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S406942

31. Jing, J, and Yan, J. Study on the effect of employees’ perceived organizational support, psychological ownership, and turnover intention: a case of China’s employee. IJERPH. (2022) 19:6016. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19106016

32. Dawley, D, Houghton, JD, and Bucklew, NS. Perceived organizational support and turnover intention: the mediating effects of personal sacrifice and job fit. J Soc Psychol. (2010) 150:238–57. doi: 10.1080/00224540903365463

33. Astuty, I, and Udin, U. The effect of perceived organizational support and transformational leadership on affective commitment and employee performance. J Asian Finance, Econ Business. (2020) 7:401–11. doi: 10.13106/JAFEB.2020.VOL7.NO10.401

34. Clark, SC . Work/family border theory: a new theory of work/family balance. Hum Relat. (2000) 53:747–70. doi: 10.1177/0018726700536001

35. Lestari, D, and Margaretha, M. Work life balance, job engagement and turnover intention: Experience from Y generation employees. Manag Sci Let. (2021) 11:165–70. doi: 10.5267/j.msl.2020.8.019

36. Xiao, W, and Luo, J. Structure model and scale development of Women’s career success. Econ Manag. (2015) 37:79–88.

37. Konlan, KD, Asampong, E, Dako-Gyeke, P, and Glozah, FN. Burnout syndrome among healthcare workers during COVID-19 pandemic in Accra, Ghana. PLoS One. (2022) 17:e0268404. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0268404

38. Pudasaini, S, Schenk, L, Möckel, M, and Schneider, A. Work-life balance in physicians working in two emergency departments of a university hospital: results of a qualitative focus group study. PLoS One. (2022) 17:e0277523. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0277523

39. Kanter, RM . Work and family in the United States: a critical review and agenda for research and policy. Russell Sage Foundation. (1977). doi: 10.7758/9781610443265

40. Westman, M . Stress and strain crossover. Hum Relat. (2001) 54:717–51. doi: 10.1177/0018726701546002

41. Shaffera, M . Struggling for balance amid turbulence on international assignments: work–family conflict, support and commitment. J Manag. (2001) 27:99–121. doi: 10.1016/S0149-2063(00)00088-X

42. Chen, C-F, and Kao, Y-L. The antecedents and consequences of job stress of flight attendants – evidence from Taiwan. J Air Transp Manag. (2011) 17:253–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2011.01.002

43. Obina, WF, Ndibazza, J, Kabanda, R, Musana, J, and Nanyingi, M. Factors associated with perceived work-life balance among health workers in Gulu District, northern Uganda: a health facility-based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. (2024) 24:278. doi: 10.1186/s12889-024-17776-8

44. Zhou, T, Guan, R, and Sun, L. Perceived organizational support and PTSD symptoms of frontline healthcare workers in the outbreak of COVID-19 in Wuhan: the mediating effects of self-efficacy and coping strategies. Applied Psych Health & Well. (2021) 13:745–60. doi: 10.1111/aphw.12267

45. Lo Presti, A, Molino, M, Emanuel, F, Landolfi, A, and Ghislieri, C. Work-family organizational support as a predictor of work-family conflict, enrichment, and balance: crossover and spillover effects in dual-income couples. Eur J Psychol. (2020) 16:62–81. doi: 10.5964/ejop.v16i1.1931

46. Fitria, Y, and Linda, MR. Perceived organizational support and work life balance on employee turnover intention. Proceedings of the 1st international conference on economics, business, entrepreneurship, and finance (ICEBEF 2018). Bandung, Indonesia: Atlantis Press (2019).

47. Robbins, SP . Essentials of organizational behavior. 8th ed. Upper Saddle River, N.J: Pearson/Prentice Hall (2005). 330 p.

48. Mekuria, MM . Factors associated to job satisfaction among healthcare Workers at Public Hospitals of west Shoa zone, Oromia regional state, Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. SJPH. (2015) 3:161. doi: 10.11648/j.sjph.20150302.12

49. Shaffril, H, and Jegak, U. The influence of SOCIO-demographic factors on work performance among employees of government agriculture agencies in MALAYSIA. J Int Social Res. (2010)

50. Al-Hussami, DRM . Study of nurses’ job satisfaction: the relationship to organizational commitment, perceived organizational support, transactional leadership, transformational leadership, and level of education. Eur J Sci Res. (2008) 22:286–95.

51. Akin Aksu, A, and Aktaş, A. Job satisfaction of managers in tourism: cases in the Antalya region of Turkey. Manag Audit J. (2005) 20:479–88. doi: 10.1108/02686900510598830

52. Van Dick, R, Christ, O, Stellmacher, J, Wagner, U, Ahlswede, O, Grubba, C, et al. Should I stay or should I go? Explaining turnover intentions with organizational identification and job satisfaction *. British J Manag. (2004) 15:351–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8551.2004.00424.x

53. Rhoades, L, and Eisenberger, R. Perceived organizational support: a review of the literature. J Appl Psychol. (2002) 87:698–714. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.698

54. Shore, LM, and Wayne, SJ. Commitment and employee behavior: comparison of affective commitment and continuance commitment with perceived organizational support. J Appl Psychol. (1993) 78:774–80. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.78.5.774

55. Allen, TD, Herst, DEL, Bruck, CS, and Sutton, M. Consequences associated with work-to-family conflict: a review and agenda for future research. J Occup Health Psychol. (2000) 5:278–308. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.5.2.278

56. Tiedje, LB, Wortman, CB, Downey, G, Emmons, C, Biernat, M, and Lang, E. Women with multiple roles: role-compatibility perceptions, satisfaction, and mental health. J Marriage Fam. (1990) 52:63. doi: 10.2307/352838

57. Ernst Kossek, E, and Ozeki, C. Work–family conflict, policies, and the job–life satisfaction relationship: a review and directions for organizational behavior–human resources research. J Appl Psychol. (1998) 83:139–49. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.83.2.139

58. Gragnano, A, Simbula, S, and Miglioretti, M. Work–life balance: weighing the importance of work–family and work–health balance. IJERPH. (2020) 17:907. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17030907

59. Aruldoss, A, Berube Kowalski, K, Travis, ML, and Parayitam, S. The relationship between work–life balance and job satisfaction: moderating role of training and development and work environment. JAMR. (2022) 19:240–71. doi: 10.1108/JAMR-01-2021-0002

60. Lu, Y, Hu, X-M, Huang, X-L, Zhuang, X-D, Guo, P, Feng, L-F, et al. The relationship between job satisfaction, work stress, work–family conflict, and turnover intention among physicians in Guangdong, China: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. (2017) 7:e014894. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014894

61. Curran, PG . Methods for the detection of carelessly invalid responses in survey data. J Exp Soc Psychol. (2016) 66:4–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2015.07.006

62. Eisenberger, R, Huntington, R, Hutchison, S, and Sowa, D. Perceived organizational support. J Appl Psychol. (1986) 71:500–7. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.71.3.500

63. Zhang, X-N, and Gu, Y. The study of the correlation to the job satisfaction and organizational commitment of the knowledge worker-an example of technology enterprises in Xi’an hi-tech industry development zone. Econ Manag J. (2010) 32:77–85.

64. Mobley, WH, Griffeth, RW, Hand, HH, and Meglino, BM. Review and conceptual analysis of the employee turnover process. Psychol Bull. (1979) 86:493–522. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.86.3.493

65. Cammann, C . Assessing the attitudes and perceptions of organizational members. Assessing organizational change: A guide to methods, measures, and practices. (1983):71–138.

66. Seashore, SE, and Taber, TD. Job satisfaction indicators and their correlates. Am Behav Sci. (1975) 18:333–68. doi: 10.1177/000276427501800303

67. Kang, IG, Croft, B, and Bichelmeyer, BA. Predictors of turnover intention in US Federal Government Workforce: machine learning evidence that perceived comprehensive HR practices predict turnover intention. Pub Personnel Manag. (2021) 50:538–58. doi: 10.1177/0091026020977562

68. Hayes, AF . Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. (2013). Available at: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:143408509

69. Vanderpool, C, and Way, SA. Investigating work–family balance, job anxiety, and turnover intentions as predictors of health care and senior services customer-contact employee voluntary turnover. Cornell Hosp Q. (2013) 54:149–60. doi: 10.1177/1938965513478682

70. Wen, T, Zhang, Y, Wang, X, and Tang, G. Factors influencing turnover intention among primary care doctors: a cross-sectional study in Chongqing, China. Hum Resour Health. (2018) 16:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12960-018-0274-z

71. Li, X, Zhang, Y, Yan, D, Wen, F, and Zhang, Y. Nurses’ intention to stay: the impact of perceived organizational support, job control and job satisfaction. J Adv Nurs. (2020) 76:1141–50. doi: 10.1111/jan.14305

72. Eisenberger, R, Armeli, S, Rexwinkel, B, Lynch, PD, and Rhoades, L. Reciprocation of perceived organizational support. J Appl Psychol. (2001) 86:42–51. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.86.1.42

73. Geevarghese, DKKS . Impact of organizational support on executives’ personal and social life: an empirical study among the executives of large scale public Sector manufacturing organizations across India. J Comput Theor Nanosci. (2018) 15:3576–9. doi: 10.1166/jctn.2018.7667

74. Asiedu-Appiah, F, and Zoogah, DB. Awareness and usage of work-life balance policies, cognitive engagement and perceived organizational support: a multi-level analysis. Africa J Manag. (2019) 5:115–37. doi: 10.1080/23322373.2019.1618684

75. Akter, KM, Banik, S, and Molla, MS. Impact of organizational and family support on work-life balance: an empirical research. Business. (2022) 3:1–13. doi: 10.38157/businessperspectivereview.v3i2.344

76. Chan, AOM . Psychological impact of the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak on health care workers in a medium size regional general hospital in Singapore. Occup Med. (2004) 54:190–6. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqh027

77. Marjanovic, Z, Greenglass, ER, and Coffey, S. The relevance of psychosocial variables and working conditions in predicting nurses’ coping strategies during the SARS crisis: an online questionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Stud. (2007) 44:991–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.02.012

78. Tremblay, D-G . Work-family balance and organizational support for fathers: an analysis of obstacles and levers in Québec (Canada). JHRSS. (2023) 11:675–97. doi: 10.4236/jhrss.2023.113037

79. Oosthuizen, RM, Coetzee, M, and Munro, Z. Work-life balance, job satisfaction and turnover intention amongst information technology employees. SABR. (2019) 20:446–67. doi: 10.25159/1998-8125/6059

80. Thangamalai, A . Work LIFE balance in health care SECTOR. J Manag Res Analysis. (2022) 2:99–101.

81. Rangachari, P, and Woods, J. Preserving organizational resilience, patient safety, and staff retention during COVID-19 requires a holistic consideration of the psychological safety of healthcare workers. IJERPH. (2020) 17:4267. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17124267

82. Worley, JA, Fuqua, DR, and Hellman, CM. The survey of perceived organisational support: which measure should we use? SA J Ind Psychol. (2009) 35:5. doi: 10.4102/sajip.v35i1.754

Keywords: turnover intention, organizational support, work-family-self balance, job satisfaction, healthcare workers

Citation: Chen Y, Xia P, Liu C, Ye C, Zeng Q and Liang B (2024) A chain mediation model on organizational support and turnover intention among healthcare workers in Guangdong province, China. Front. Public Health. 12:1391036. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1391036

Edited by:

Juan Jesús García-Iglesias, University of Huelva, SpainReviewed by:

Faiza Manzoor, Zhejiang University, ChinaMaura Pilotti, Prince Mohammad bin Fahd University, Saudi Arabia

Copyright © 2024 Chen, Xia, Liu, Ye, Zeng and Liang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ping Xia, eGlhcGluZ0BnZHB1LmVkdS5jbg==

Yuanyuan Chen1

Yuanyuan Chen1 Ping Xia

Ping Xia Chaojie Liu

Chaojie Liu