94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

MINI REVIEW article

Front. Public Health, 19 June 2024

Sec. Children and Health

Volume 12 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1390107

Bolajoko O. Olusanya1*

Bolajoko O. Olusanya1* Scott M. Wright2†

Scott M. Wright2† Tracey Smythe3

Tracey Smythe3 Mary A. Khetani4

Mary A. Khetani4 Marisol Moreno-Angarita5

Marisol Moreno-Angarita5 Sheffali Gulati6

Sheffali Gulati6 Sally A. Brinkman7

Sally A. Brinkman7 Nihad A. Almasri8

Nihad A. Almasri8 Marta Figueiredo9

Marta Figueiredo9 Lidia B. Giudici10

Lidia B. Giudici10 Oluwatosin Olorunmoteni11

Oluwatosin Olorunmoteni11 Paul Lynch12

Paul Lynch12 Brad Berman13

Brad Berman13 Andrew N. Williams14

Andrew N. Williams14 Jacob O. Olusanya1

Jacob O. Olusanya1 Donald Wertlieb15

Donald Wertlieb15 Adrian C. Davis16†

Adrian C. Davis16† Mijna Hadders-Algra17†

Mijna Hadders-Algra17† Melissa J. Gladstone18

Melissa J. Gladstone18 On behalf of the Global Research on Developmental Disabilities Collaborators (GRDDC)

On behalf of the Global Research on Developmental Disabilities Collaborators (GRDDC)Early childhood is foundational for optimal and inclusive lifelong learning, health and well-being. Young children with disabilities face substantial risks of sub-optimal early childhood development (ECD), requiring targeted support to ensure equitable access to lifelong learning opportunities, especially in low- and middle-income countries. Although the Sustainable Development Goals, 2015–2030 (SDGs) emphasise inclusive education for children under 5 years with disabilities, there is no global strategy for achieving this goal since the launch of the SDGs. This paper explores a global ECD framework for children with disabilities based on a review of national ECD programmes from different world regions and relevant global ECD reports published since 2015. Available evidence suggests that any ECD strategy for young children with disabilities should consists of a twin-track approach, strong legislative support, guidelines for early intervention, family involvement, designated coordinating agencies, performance indicators, workforce recruitment and training, as well as explicit funding mechanisms and monitoring systems. This approach reinforces parental rights and liberty to choose appropriate support pathway for their children. We conclude that without a global disability-focussed ECD strategy that incorporates these key features under a dedicated global leadership, the SDGs vision and commitment for the world’s children with disabilities are unlikely to be realised.

Early childhood development (ECD) is foundational for optimal learning, health and wellbeing over the life-course and a nation’s human capital development (1). This recognition is reflected in global agendas like the Incheon Declaration on Education 2030 (2), and the Sustainable Development Goals, 2015–2030, (SDGs) (3). The SDGs include a specific target to ensure that by 2030 children under 5 years of age (defined as “children under-5” hereinafter) can access quality ECD in readiness for primary education (SDG 4.2) (3). Globally, over 50 million children under-5 have mild-to-severe disabilities predominantly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), with 30 million having moderate-to-severe disabilities (4, 5). Childhood disabilities are diverse in nature, type and severity and are associated with functional difficulties typically from hearing impairment, visual impairment, deaf-blindness, speech and language disorders, intellectual disability, learning disabilities, autism spectrum disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, epilepsy, cerebral palsy, muscular dystrophies, spina bifida or multiple disorders that require wide-ranging support services (6). The disproportionate disadvantages faced by children with disabilities compared to children without disabilities, including higher risk of morbidity, premature death, lower rates of school enrolment and completion, and social exclusion are widely reported (4, 7, 8). Also recognised is the substantial emotional, health, psychosocial and economic impact of childhood disability on the affected families (9–11), and the need to prioritise children with disabilities in any global ECD initiatives (4, 12). However, there is presently no strategy to implement the global ECD agenda towards school readiness for children under-5 with disabilities, especially in LMICs (13–15). Such a strategy is needed to provide a unifying framework and action plan among UN member states and international developmental assistance providers for the effective implementation of global commitment on ECD (16–18). The only existing global ECD initiative - the “Nurturing Care Framework” (NCF) – focuses on the first 1,000 days from conception (19) and was not designed to promote school readiness for children under-5 with and without disabilities (15). In this paper, we discuss the need and features of an appropriate global disability-focussed ECD strategy for children under-5 with disabilities based on an overview of well-established national ECD programmes in different world regions. ECD policies and programmes designed to serve all children from birth to school entry (5–6 years) are termed “disability-inclusive,” while those designed exclusively to identify and support children with developmental delays and disabilities are termed “disability-focused” or “disability-specific.”

A global survey of ECD programmes published in 2019 by the Early Childhood Development Task Force in collaboration with UNICEF reported 426 programmes from 121 countries (20). The largest number of programmes were reported from Sub-Saharan Africa (n = 115 or 27%), and the least number from the Middle East and North Africa (n = 14 or 3.3%). To identify relevant national ECD programmes from different world regions we examined ECD and inclusive education reports published after the launch of the SDGs by UNICEF, WHO, the World Bank, UNESCO, and the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and USAID (21–26). We also reviewed global disability-related ECD reports published between 2015 and 2023 by International Disability and Development Consortium, International Disability Alliance, and major funders of disability projects in LMICs, including USAID and DFID to complement the findings from the national ECD programmes (Appendix 1).

After an interactive session on the primary goal of this review and prior publications by GRDDC, we chose 10 key criteria for selecting ECD programmes for our analysis namely: the existence of a national policy or programme, date of establishment of at least 10 years, relevant legislations, target beneficiaries, type of disability services offered, designated service providers, performance indicators, budget or disbursements, governance structure and open data sources. We were unable to select countries based on indicators such as the rate of school enrolment or drop-out rate among children with disabilities because of the general lack of publicly available population-based data particularly in LMICs (4, 5).

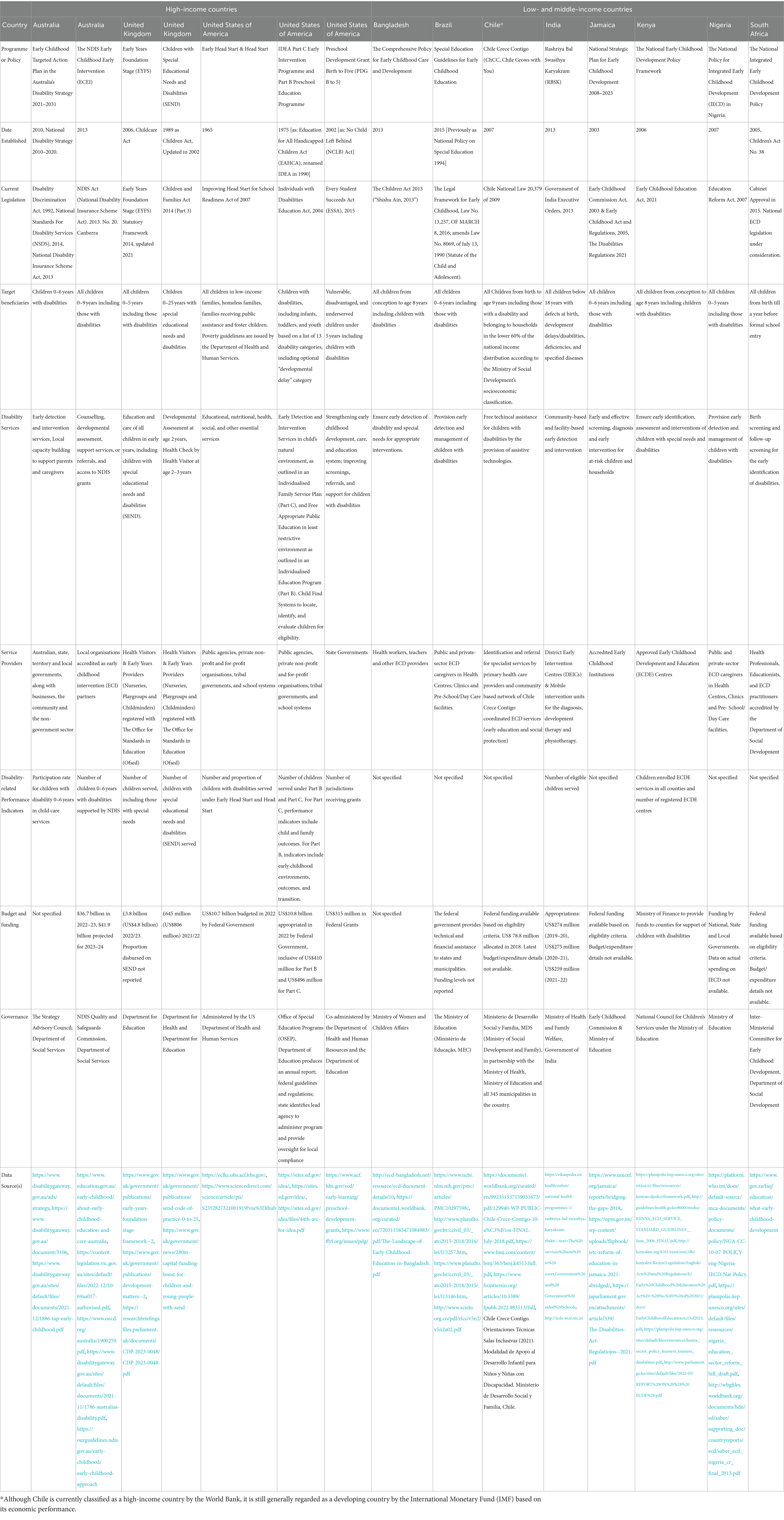

Fifteen national ECD programmes from 11 countries (three high-income countries or HICs and eight LMICs countries) were purposively selected (27), based on sufficient publicly available information on the parameters listed in Table 1, including countries with substantial prevalence of children with disabilities (4, 28). Three countries (Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa) were selected from sub-Saharan Africa, three (Brazil, Chile and Jamaica) from Latin America and the Caribbean, and two countries (Bangladesh and India) from South Asia. Additionally, one HIC each was included from North America (United States of America), Europe (United Kingdom), and East Asia/Pacific (Australia). Limited data were available from Middle-East and North Africa on disability-inclusive or disability-focused ECD as per the chosen criteria (25, 26). The 11 countries selected account for approximately 39% of the estimated 3 million children with disabilities in HICs and 35% of the 50 million children with disabilities in LMICs (28).

Table 1. Overview of selected national early childhood development programmes for children with disabilities.

The key findings from the national ECD programmes reviewed are summarised as follows.

Early detection and intervention services for children with disabilities in the first 3 years of life are delivered predominantly within the health sector by diverse professionals including community health workers. The responsibility for the 3–5 years pre-school age is shared by both the health and educational sectors to ensure effective transition to school. Active collaboration between the health and educational sectors with support by the social and finance sectors is recognised as essential to promoting school readiness (29, 30).

Many ECD programmes are presented as disability-inclusive, suggesting that all children are provided equal access to all listed services from birth to school entry. However, several cultural, logistical, financial and systemic barriers to equitable access, including discrimination, stereotyping, and stigmatisation are commonly reported (31), making true inclusion for children with disabilities unattainable. Moreover, children with disabilities are not a homogeneous group (6), and many require individualised support to learn and participate on an equal basis with their peers without disabilities (31, 32). Hence, one-size-fits-all ECD programmes often missed or are poorly equipped to serve children with disabilities, particularly those with complex conditions. It also infringes on parental rights and freedom to choose what they consider to be in the child’s best interest.

A twin-track approach has therefore, emerged in several countries like Australia, UK, India and USA, where a disability-inclusive ECD programme is implemented alongside a dedicated disability-focussed ECD programme to optimise access to support services for children with disabilities. Each track is independently managed by a designated department or ministry but coordinated to effectively serve all children with disabilities. For instance, in the USA, disability-inclusive Head Start and Early Head Start programmes under the Department of Health (29), are complemented with disability-focused early intervention programme under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) coordinated by the Department of Education (30). In the UK, the Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS) programme for all children under-5 (33), is implemented alongside disability-focused Children with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND) (34). In India, the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) programme which provides early childhood care for all children under-6 (35), is supported with the disability-focused Rashtriya Bal Swasthya Karyakram (RBSK) programme (36).

ECD programmes are supported with guidelines for routine newborn screening, developmental screening and surveillance, diagnosis and timely referrals for children with developmental delays and disabilities. Early parenting support is prioritised to ensure family-centred intervention. In some countries, ECD guidelines are integrated with community-based and facility-based maternal and child health services. However, routine newborn screening for developmental disorders and disabilities that is mandated in several HICs is limited in LMICs (37, 38).

National legislations or executive orders are put in place to support ECD programmes for children with disabilities. These laws outline eligibility criteria, service entry points, family involvement, coordinating agencies, performance indicators, workforce training, enforceable rights of children with disabilities and their families, and statutory provisions for funding. Some legislations designate functions to be carried out by various levels of government: national, state and local authorities. Others make explicit provisions for non-state actors including non-governmental organisations. Engagement with and active participation by organisations for people with disabilities (OPDs), adults with lived experience and parent groups is also mandated in line with the UN Conventions of the Rights of the Child (UN-CRC) and the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UN-CRPD). These legislations facilitate political support for ECD programmes especially for budgetary allocation, and they also provide tools for advocacy.

Funding schemes for implementing service provisions in the ECD legislations are established predominantly in HICs. Most services are federally funded and grants are made to other levels of government based on agreed protocol and responsibilities. The US-based Head Start Programme and Early Intervention and Preschool Education Programme under the IDEA are perhaps the most established and well-funded multi-racial disability-oriented national programmes globally. Funding for IDEA reached $10.8 billion in 2022, supporting states to implement the Act, with $410 million allocated for preschool grants and $496 million for early intervention services. Disability insurance schemes that provide financial assistance directly to families especially where costly support services and assistive technologies are necessary also exist in some countries like Australia. In many LMICs, the absence of federal funding for ECD services contributes to the failure or ineffectiveness of national ECD programmes, even when disability legislations are in place (39, 40).

Multisectoral coordination, monitoring and a system of accountability at the national and community levels are provided and legislated in many countries. The accountability mechanisms stipulate roles and responsibilities, rewards and incentives for good performance as well as penalties for poor or non-performance. For example, in the USA, at least 10% of enrolled children must have disabilities and be eligible for special education or early intervention services under the Head Start and Early Head Start programmes. Since inception, these programmes have served over 38 million children and families with up to 13% enrolment of children with disabilities. Before 1975, many disabled children in the USA were excluded from public schools, but in the 2020–21 school year, over 7.5 million received special education services, with more than 66% integrated into general education classrooms under IDEA. Since its inception, India’s RBSK has served approximately 1.2 billion children under 18 years, identifying 86 million with selected impairments or disorders through 360 District Early Intervention Centres.

Based on the foregoing findings from the national ECD programmes we summarise critical considerations for developing a global disability ECD strategy in this section. It is noteworthy to mention that some of these findings are reinforced by several global ECD reports. For example, a twin-track approach is recommended in the UN Disability Inclusion Strategy (41), the Disability Inclusion Policy and Strategy by UNICEF (42), WHO Disability Policy (43), the World Bank Policy on Disability-Inclusive Health Systems (16), USAID Policy on Inclusive Education (12, 17), and reports from OPDs (31, 44). However, there is no dedicated global ECD strategy for children with disabilities. The NCF already underscores the critical role of a globally coordinated ECD strategy for implementing the global agenda for child development especially in LMICs (19) and has the potential to serve as a pathway for mainstreaming children with disabilities (19). However, because the programme was not originally developed as a disability-inclusive ECD strategy, efforts have been made lately for its adaptation to serve this purpose (45). An independent and complementary disability-focused ECD strategy is now required to ensure targeted support for children with disabilities under the twin-track model.

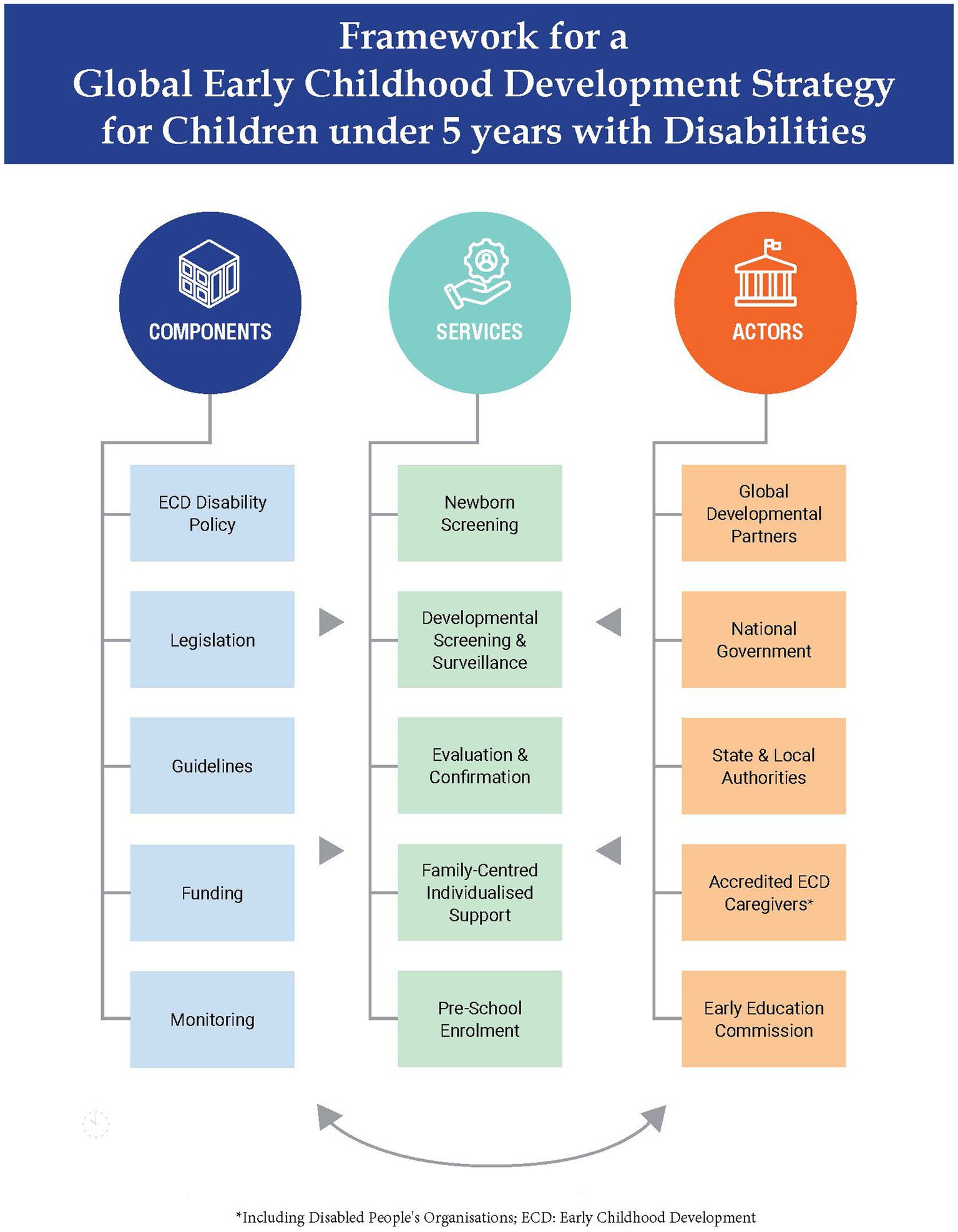

A conceptual framework for developing a global disability-focused ECD strategy for children under-5 with disabilities is proposed in Figure 1. The overarching goal and centrepiece of the strategy is to ensure that young children with developmental delays and disabilities are identified early and provided the required support to facilitate equitable access to inclusive education. Within this framework, inclusive education is not merely about integration, merging or mainstreaming. It is the mode of learning that optimises the potential of a child with any degree of disability for inclusion into the wider society. The broad issues to be addressed based on findings from our review are grouped under components of policy issues, services required for timely identification of and intervention for children with disabilities and key actors for implementing the strategy.

Figure 1. Recommended framework for early childhood development for children under 5 years with disabilities.

A comprehensive global ECD strategy for young children with disabilities ideally should encompass several key components, including a well-defined disability policy, supportive legislation, operational guidelines, sustainable funding mechanism and a robust monitoring system. The proposed policy should address the needs of children with disabilities from birth up to age 5 years, emphasising the critical role of early intervention from birth as a foundation for pre-school education. Early intervention before age 2–3 years has been demonstrated in longitudinal studies to reduce the need for special education for some children with developmental delays and disabilities at school entry (46, 47). The exclusion of children under 2 years from the current indicator for SDG 4.2 and the UNICEF monitoring tool (ECDI2030) therefore, needs to be resolved as soon as possible (48). The ECDI2030 should be harmonised with the Global Scale for Early Development for children aged 0–3 years recently developed by WHO to produce a single tool for children under-5 for use in all LMICs. The global disability policy should make explicit provisions for the required health and educational services including newborn and developmental screening and surveillance ideally synchronised with well-child visits including routine immunisation, referral pathway for diagnostic evaluation, and links for timely enrolment into family-centred support programmes for children with disabilities (49, 50). The absence of routine newborn screening for developmental disorders and disabilities in the vast majority of many LMICs needs to be addressed to ensure the timely detection of children with disabilities. Early parenting interventions should be emphasised to minimise the emotional burden and sense of helplessness often encountered by parents following diagnosis of disability in their child (51, 52). The policy should also provide clear guidance on how to manage the transition from family-based intervention services in the first 3 years of life to pre-school enrolment starting at age 3 years.

The global ECD policy needs to be supported by appropriate legislations (4, 53–55). All countries included in our review had specific disability laws or general legislations for all children with or without reference to children with disabilities. The UN Conventions of the Rights of the Child and the Rights of Persons with Disabilities already provide a practical framework and guidance for mandating all countries to make specific provisions for children under-5 in their national laws for persons with disabilities and childcare legislations. A template can be developed to assist countries with and without disability legislations to make specific legally binding provisions for services required by children with disabilities in line with SDG 4.2. Such legislations also empower parents to seek their rights to state support for their children.

Comprehensive operational guidelines for service providers across all levels of service delivery are necessary. These guidelines should be adaptable to different populations and should reflect the standard protocol for clinical recommendations and guidelines provided by WHO. The guidelines should address the range of services listed in the framework as a matter of principle and best practice. Even in situations where ideal technologies may not be readily available, these guidelines can serve as a valuable compass, informing service providers about the desired direction and potential avenues for future improvement.

Disability policies and legislations are necessary but not sufficient without funding. The critical role of funding is reinforced in various global reports on disability inclusion (Appendix 1). Many LMICs rely on funding from donor organisations and HICs for maternal and child health programmes (56) and are more likely to require such support for ECD initiatives (57). In our view, the introduction of a global disability-focussed ECD strategy is likely to attract greater attention and funding. At the current levels of developmental assistance to LMICs for childhood disabilities by OECD donors and others, the global ECD agenda is unachievable (58). A dedicated global fund should be considered to support LMICs that have instituted appropriate legislations for children with disabilities and are committed to allocating a proportion of their annual health and educational budgets for ECD services.

Global funding schemes require effective monitoring system for accountability linked to specific performance indicators (16, 41–43, 55). For example, it is important to track the number of children that are screened, identified with disabilities, enrolled for early intervention services, and attending preschool programmes during each reporting period. Ongoing access to global funds should be contingent on these performance indicators.

The key actors with critical roles in ensuring the effectiveness of the global ECD Strategy include donor organisations, relevant government ministries, state and local authorities, accredited providers of services for children with disabilities at community-level, including OPDs and a designated national governance body. Countries may consider establishing an independent but multidisciplinary ECD Commission with specific mandate for inclusive education in line with all the provisions of the SDG 4.2. In line with the efforts to transform the NCF into a global disability-inclusive ECD programme, it will be necessary to designate lead UN agencies for the development and implementation of the global disability-focussed ECD strategy. Additionally, we recommend that in developing a comprehensive global strategy as proposed in this paper, the relevant UN agencies should consider engaging with administrators of established national ECD programmes in different world regions for better insights on the associated operational challenges and how to address them. Lessons and key performance indicators (e.g., school enrolment and participation, school completion rate, programme costs) that have not been published can be garnered from such engagements to inform the introduction of global and national targets. Also, it is important to clarify that the implementation of a global strategy is typically country-led, allowing nations to adapt and prioritise service delivery within a defined operational framework to promote a greater sense of ownership and best possible developmental outcomes across diverse cultures and contexts. We are not unmindful of several cultural, health and social barriers to service delivery and uptake that persist even in countries with well-established and well-funded ECD programmes especially in high-income countries (59–62). A global disability-focussed ECD strategy is unlikely to fully address the stigma and discrimination faced by children with disabilities and their families worldwide as they transition into school education in inclusive settings. However, it provides a pathway for individualised support especially for children with severe or complex disabilities.

The global ECD commitment under the SDGs requires that disabled children and their families are empowered from birth for equitable access and participation in the larger society through inclusive and quality education. This aspiration is supported by disability-inclusion policies of various UN agencies and OPDs since 2015. Evidence from well-established ECD national programmes have shown that children with disabilities and their families are better served through a twin track approach in which a dedicated and disability-focused ECD strategy is implemented alongside disability-inclusive ECD programmes for all young children. This review provides a framework for developing an independent global disability-focussed ECD strategy aimed at ensuring that children with disabilities and their families are adequately served in all countries. It is unlikely that the vision and commitment under the SDGs for children with disabilities will be realised without such a strategy under a dedicated global leadership.

BO: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. SW: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. TS: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Data curation. MK: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Data curation. MM-A: Writing – review & editing, Data curation. SG: Writing – review & editing. SB: Writing – review & editing, Data curation. NA: Writing – review & editing. MF: Writing – review & editing. LG: Writing – review & editing. OO: Writing – review & editing. PL: Writing – review & editing. BB: Writing – review & editing. AW: Writing – review & editing. JO: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Data curation. DW: Writing – review & editing. AD: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. MH-A: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. MG: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision. The authors are members of the Global Research on Developmental Disabilities Collaborators (GRDDC) - a diversified group of caregivers with and without lived experience of disability from various socio-cultural and income settings, along with parents of children with disabilities.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The publication fee for this article was funded by the Children’s Participation in Environmental Research Lab, University of Chicago, USA.

We are grateful to our colleagues, Nem-Yun Boo, Cecilia Breinbauer, Vivian Cheung, Rekha Radhakrishnan, Maureen Samms-Vaughan, MKC Nair, and Chiara Servili for helpful comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that BOO was an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decisio.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1390107/full#supplementary-material

ECD, early childhood development; HIC, high-income country; IDEA, Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, USA; LMIC, low- and middle-income country; NCF, nurturing care framework; OPDs, organisations of people with disabilities; RBSK, Rashtriya Bal Swasthya Karyakram, India; SDG, Sustainable Development Goal; UN-CRC, United Nations Conventions on the Rights of the Child; UN-CRPD, United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

1. World Bank . From early child development to human development: investing in our children’s future. Proceedings of a World Bank Conference on Investing in Our Children’s Future Washington, D.C., April 10–11, 2000. ME Young (Ed). The World Bank: Washington DC. (2002).

2. UNESCO . Education 2030 framework for action. (2016) Available at: https://apa.sdg4education2030.org/education-2030-framework-action (Accessed February 20, 2024).

3. United Nations . Sustainable development goals. (2015). Available at: http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals (Accessed February 20, 2024).

4. United Nations Children’s Fund . Seen, counted, included: using data to shed light on the well-being of children with disabilities. (2021). Available at: https://data.unicef.org/resources/children-with-disabilities-report-2021/ (Accessed February 20, 2024).

5. Olusanya, BO, Kancherla, V, Shaheen, A, Ogbo, FA, and Davis, AC. Global and regional prevalence of disabilities among children and adolescents: analysis of findings from global health databases. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:977453. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.977453

6. Olusanya, BO, Storbeck, C, Cheung, VG, and Hadders-Algra, M. Global research on developmental disabilities collaborators (GRDDC). Disabilities in early childhood: a Global Health perspective. Children. (2023) 10:155. doi: 10.3390/children10010155

7. Kuper, H, Monteath-van Dok, A, Wing, K, Danquah, L, Evans, J, Zuurmond, M, et al. The impact of disability on the lives of children; cross-sectional data including 8,900 children with disabilities and 898,834 children without disabilities across 30 countries. PLoS One. (2014) 9:e107300. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107300

8. Abuga, JA, Kariuki, SM, Kinyanjui, SM, Boele van Hensbroek, M, and Newton, CR. Premature mortality, risk factors, and causes of death following childhood-onset neurological impairments: a systematic review. Front Neurol. (2021) 12:627824. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.627824

9. Cheng, AWY, and Lai, CYY. Parental stress in families of children with special educational needs: a systematic review. Front Psych. (2023) 14:1198302. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1198302

10. Reichman, NE, Corman, H, and Noonan, K. Impact of child disability on the family. Matern Child Health J. (2008) 12:679–83. doi: 10.1007/s10995-007-0307-z

11. Whiting, M . Impact, meaning and need for help and support: the experience of parents caring for children with disabilities, life-limiting/life-threatening illness or technology dependence. J Child Health Care. (2013) 17:92–108. doi: 10.1177/1367493512447089

12. United States Agency for International Development . Global child thrive act: implementation Guidance. (2023). Available at: https://www.advancingnutrition.org/resources/global-thrive-act-implementation-guidance (Accessed February 20, 2024).

13. Every Woman Every Child . The global strategy for women's, children's and adolescents' health. (2016–2030). Available at: https://globalstrategy.everywomaneverychild.org/ (Accessed February 20, 2024).

14. Cieza, A, Kamenov, K, Sanchez, MG, Chatterji, S, Balasegaram, M, Lincetto, O, et al. Disability in children and adolescents must be integrated into the global health agenda. BMJ. (2021) 372:n9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n9

15. Olusanya, BO, Gulati, S, and Newton, CRJ. The nurturing care framework and children with developmental disabilities in LMICs. Pediatrics. (2023) 151:e2022056645. doi: 10.1542/peds.2022-056645

16. World Bank . Disability-inclusive health care systems: technical note for World Bank task teams. Washington, DC: World Bank (2022).

17. United States Agency for International Development . Are we fulfilling our promises? Inclusive education in Sub-Saharan Africa. (2020). Available at: https://www.edu-links.org/resources/are-we-fulfilling-our-promises-inclusive-education-sub-saharan-africa (Accessed February 20, 2024).

18. Olusanya, BO, Gulati, S, Berman, BD, Hadders-Algra, M, Williams, AN, Smythe, T, et al. Global research on developmental disabilities collaborators (GRDDC). Global leadership is needed to optimize early childhood development for children with disabilities. Nat Med. (2023) 29:1056–60. doi: 10.1038/s41591-023-02291-x

19. United Nations Children’s Fund, World Health Organisation, the World Bank Group . Nurturing care for early childhood development: a framework for helping children survive and thrive to transform health and human potential. Geneva: World Health Organisation (2018).

20. Vargas-Barón, E, Small, J, Wertlieb, D, Hix-Small, H, Gómez Botero, R, Diehl, K, et al. Global survey of inclusive early childhood development and early childhood intervention programs. Washington, DC: RISE Institute (2019).

21. OECD . Starting strong 2017: key OECD indicators on early childhood education and care, starting strong. Paris: OECD Publishing (2017).

22. Grimes, P, and de la Cruz, A. Mapping of disability-inclusive education practices in South Asia. Kathmandu: United Nations Children’s Fund Regional Office for South Asia (2021).

23. UNICEF . Mapping and recommendations on disability-inclusive education in eastern and Southern Africa. (2023). Available at: https://www.unicef.org/esa/media/12201/file/Full_Report_Mapping_of_Progress_towards_disability-inclusive_in_ESA.pdf (Accessed February 20, 2024).

24. UNESCO . Global education monitoring report, 2020, Latin America and the Caribbean: inclusion and education: all means all. (2020). Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000374614 (Accessed February 20, 2024).

25. Contin, R, Khochen-Bagshaw, M, Stephan, C, and Khoury, N. Middle East and North Africa (MENA) disability inclusive education study. (2022). Available at: https://www.edu-links.org/resources/DisabilityInclusiveEducationStudy (Accessed February 20, 2024).

26. El-Kogali, S, and Krafft, C. Expanding opportunities for the next generation: early childhood development in the Middle East and North Africa. Washington, DC: World Bank (2015).

27. Seawright, J, and Gerring, J. Case selection techniques in case study research: a menu of qualitative and quantitative options. Polit Res Q. (2008) 61:294–308. doi: 10.1177/1065912907313077

28. Global Research on Developmental Disabilities Collaborators . Developmental disabilities among children younger than 5 years in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Glob Health. (2018) 6:e1100–21. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30309-7

29. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services . Head Start. Early Childhood Learning and Knowledge Centre. Available at: https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/ (Accessed February 20, 2024).

30. U.S. Department of Education, Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services, Office of Special Education Programs . 44th Annual Report to Congress on the Implementation of IDEA. (2022). Available at: https://sites.ed.gov/idea/files/44th-arc-for-idea.pdf (Accessed February 20, 2024).

31. Sapiets, SJ, Totsika, V, and Hastings, RP. Factors influencing access to early intervention for families of children with developmental disabilities: a narrative review. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. (2021) 34:695–711. doi: 10.1111/jar.12852

32. International Disability and Development Consortium (IDDC) . Inclusive education: an imperative for advancing human rights and sustainable development. Conference of State Parties (CoSP) to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UN-CRPD), New York. (2023).

33. United Kingdom Government . Department of Education. Statutory framework for the early years foundation stage setting the standards for learning, development and care for children from birth to five. (2023). Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/65aa5e29ed27ca001327b2c6/EYFS_statutory_framework_for_childminders.pdf (Accessed February 20, 2024).

34. United Kingdom Government . Department of education and department of health. Special educational needs and disability code of practice: 0 to 25 years. Statutory guidance for organisations which work with and support children and young people who have special educational needs or disabilities. (2015). Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a7dcb85ed915d2ac884d995/SEND_Code_of_Practice_January_2015.pdf (Accessed February 20, 2024).

35. Integrated Child Development Services . Ministry of women and child development, government of India. (2022). Available at: http://icds-wcd.nic.in (Accessed December 30, 2023).

36. National Health Mission, India . Rashtriya Bal Swasthya Karyakram (RBSK). Child Health Screening and Early Intervention Services. Ministry of Health & Family Welfare Government of India May 2014. Available at: https://nhm.gov.in/index4.php?lang=1&level=0&linkid=499&lid=773 (Accessed February 20, 2024).

37. Therrell, BL, Padilla, CD, Loeber, JG, Kneisser, I, Saadallah, A, Borrajo, GJ, et al. Current status of newborn screening worldwide: 2015. Semin Perinatol. (2015) 39:171–87. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2015.03.002

38. Kim, S . Worldwide national intervention of developmental screening programs in infant and early childhood. Clin Exp Pediatr. (2022) 65:10–20. doi: 10.3345/cep.2021.00248

39. Samms-Vaughan, M. Bridging the gap: towards a system of early years care and support. UNICEF. (2020). Available at: https://www.unicef.org/jamaica/reports/bridging-the-gaps-2019 (Accessed February 20, 2024).

40. Abboah-Offei, M, Amboka, P, and Nampijja, M. Improving early childhood development in the context of the nurturing care framework in Kenya: a policy review and qualitative exploration of emerging issues with policy makers. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:1016156. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1016156

41. United Nations Disability Inclusion Strategy . Available at: https://www.un.org/en/content/disabilitystrategy/ (Accessed February 20, 2024).

42. United Nations Children’s Fund . Disability inclusion policy and strategy (DIPAS) 2022–2030. New York: UNICEF (2022).

43. WHO Policy on Disability . Geneva. (2021). Available at: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/341079/9789240020627-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (Accessed 20 February 2024).

44. Light for the World . Leave no child behind: invest in the early years. Global Report 2020. Available at: https://www.light-for-the-world.org/publications/leave-no-child-behind-invest-in-the-early-years/ (Accessed February 20, 2024).

45. WHO, UNICEF . Nurturing care framework progress report 2018–2023: reflections and looking forward. (2023). Available at: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/369449/9789240074460-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (Accessed February 20, 2024).

46. Hebbeler, K, Spiker, D, Scarborough, A, Mallik, S, Simeonsson, R, Singer, M, et al. National early intervention longitudinal study (NEILS) final report. Menlo Park, CA: SRI International (2007).

47. Hauser-Cram, P, Warfield, ME, Shonkoff, JP, Krauss, MW, Sayer, A, and Upshur, CC. Children with disabilities: a longitudinal study of child development and parent well-being. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. (2007) 66: i–viii, 1–114; discussion 115–26.

48. Olusanya, BO, Hadders-Algra, M, Breinbauer, C, Williams, AN, Newton, CRJ, Davis, AC, et al. The conundrum of a global tool for early childhood development to monitor SDG indicator 4.2.1. Lancet Glob Health. (2021) 9:e586–7. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00030-9

49. Lipkin, PH, Macias, MM, COUNCIL ON CHILDREN WITH DISABILITIES, SECTION ON DEVELOPMENTAL AND BEHAVIORAL PEDIATRICSNorwood, KW Jr, Brei, TJ, Davidson, LF, et al. Promoting optimal development: identifying infants and young children with developmental disorders through developmental surveillance and screening. Pediatrics. (2020) 145:e20193449. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3449

50. Barger, B, Rice, C, Wolf, R, and Roach, A. Better together: developmental screening and monitoring best identify children who need early intervention. Disabil Health J. (2018) 11:420–6. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2018.01.002

51. Hohlfeld, ASJ, Harty, M, and Engel, ME. Parents of children with disabilities: a systematic review of parenting interventions and self-efficacy. Afr J Disabil. (2018) 7:437. doi: 10.4102/ajod.v7i0.437

52. Akhbari Ziegler, S, de Souza Morais, RL, Magalhães, L, and Hadders-Algra, M. The potential of COPCA’s coaching for families with infants with special needs in low- and middle-income countries. Front Pediatr. (2023) 11:983680. doi: 10.3389/fped.2023.983680

53. WHO/UNICEF . Global report on children with developmental disabilities: from the margins to the mainstream. Geneva: World Health Organization and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) (2023).

54. United Nations Children’s Fund . Early childhood development. UNICEF vision for every child. New York: UNICEF (2023).

55. WHO . Global report on health equity for persons with disabilities. Geneva: World Health Organization (2022).

56. Global Burden of Disease 2020 Health Financing Collaborator Network . Tracking development assistance for health and for COVID-19: a review of development assistance, government, out-of-pocket, and other private spending on health for 204 countries and territories, 1990-2050. Lancet. (2021) 398:1317–43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01258-7

57. Arregoces, L, Hughes, R, Milner, KM, Hardy, VP, Tann, C, Upadhyay, A, et al. Accountability for funds for nurturing care: what can we measure? Arch Dis Child. (2019) 104:S34–42. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2018-315429

58. Olusanya, BO, Davis, AC, Hadders-Algra, M, and Wright, SM. Global investments to optimise the health and wellbeing of children with disabilities: a call to action. Lancet. (2023) 401:175–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)02368-6

59. The Health Resources and Services Administration’s (HRSA) . Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB). Children and youth with special health care needs. NSCH Data Brief. (2022). Available at: https://mchb.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/mchb/programs-impact/nsch-data-brief-children-youth-special-health-care-needs.pdf (Accessed April 8, 2024).

60. Carlson, E, Bitterman, A, and Daley, T. Access to educational and community activities for young children with disabilities. Rockville, MD: Westat (2010).

61. The Disabled Children’s Partnership . Failed and forgotten. Executive Summary. (2023). Available at: https://disabledchildrenspartnership.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Failed-and-Forgotten-DCP-report-2023.pdf (Accessed April 8, 2024).

62. UK Children’s Commissioner Report . We all have a voice: disabled children’s vision for change. (2023). Available at: https://assets.childrenscommissioner.gov.uk/wpuploads/2023/10/We-all-have-a-voice-Disabled-childrens-vision-for-change_final.pdf (Accessed April 8, 2024).

Keywords: developmental disabilities, early childhood development, global strategy, school readiness, inclusive education, nurturing care framework, Sustainable Development Goals, twin track approach

Citation: Olusanya BO, Wright SM, Smythe T, Khetani MA, Moreno-Angarita M, Gulati S, Brinkman SA, Almasri NA, Figueiredo M, Giudici LB, Olorunmoteni O, Lynch P, Berman B, Williams AN, Olusanya JO, Wertlieb D, Davis AC, Hadders-Algra M and Gladstone MJ (2024) Early childhood development strategy for the world’s children with disabilities. Front. Public Health. 12:1390107. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1390107

Received: 22 February 2024; Accepted: 28 May 2024;

Published: 19 June 2024.

Edited by:

Michael Msall, University of Chicago Medical Center, United StatesReviewed by:

Daniel Holzinger, Hospitaller Brothers of Saint John of God Linz, AustriaCopyright © 2024 Olusanya, Wright, Smythe, Khetani, Moreno-Angarita, Gulati, Brinkman, Almasri, Figueiredo, Giudici, Olorunmoteni, Lynch, Berman, Williams, Olusanya, Wertlieb, Davis, Hadders-Algra and Gladstone. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bolajoko O. Olusanya, Ym9sYWpva28ub2x1c2FueWFAdWNsbWFpbC5uZXQ=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share senior authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.