- 1Iranian Center of Excellence in Health Management (IceHM), Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

- 2Student Research Committee, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

- 3Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Birjand University of Medical Sciences, Birjand, Iran

Objective: This study aimed to investigate the evidence regarding vaccine hesitancy including refusal rate, associated factors, and potential strategies to reduce it.

Methods: This is a scoping review. Three main databases such as PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science were searched from 1 January 2020 to 1 January 2023. All original studies in the English language that investigated one of our domains (vaccine hesitancy rate, factors associated with vaccine hesitancy, and the ways/interventions to overcome or decrease vaccine hesitancy) among the general population were included in this study. The data were charted using tables and figures. In addition, a content analysis was conducted using the 3C model of vaccine hesitancy (Confidence, Complacency, and Convenience) that was previously introduced by the WHO.

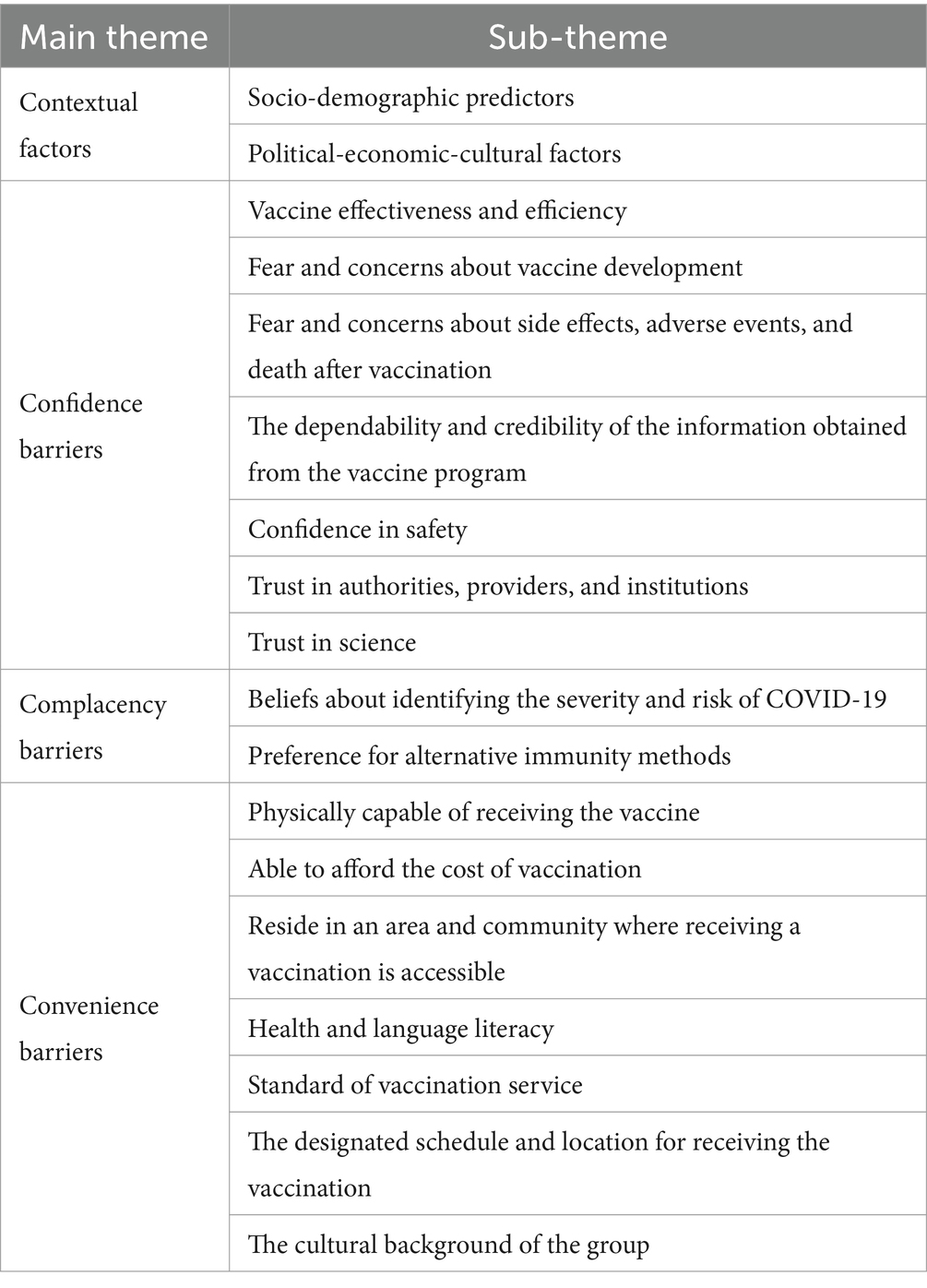

Results: Finally, 184 studies were included in this review. Of these, 165, 181, and 124 studies reported the vaccine hesitancy rate, associated factors, and interventions to reduce or overcome vaccine hesitancy, respectively. Factors affecting the hesitancy rate were categorized into 4 themes and 18 sub-themes (contextual factors, confidence barriers, complacency barriers, and convenience barriers).

Conclusion: Vaccine hesitancy (VH) rate and the factors affecting it are different according to different populations, contexts, and data collection tools that need to be investigated in specific populations and contexts. The need to conduct studies at the national and international levels regarding the reasons for vaccine refusal, the factors affecting it, and ways to deal with it still remains. Designing a comprehensive tool will facilitate comparisons between different populations and different locations.

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) declared coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) a global pandemic in March 2020 (1, 2). The COVID-19 pandemic has caused adverse health and socioeconomic impacts; as of January 2024, approximately 6.5 million people have died around the world (3). In May 2020, people all over the world agreed that getting vaccinated was important to stop the spread of COVID-19 (2, 4). The quick development of a COVID-19 vaccine gave hope for life to go back to normal. Despite the successful public vaccine uptake, many people delayed or refused to take the vaccination (5, 6).

With the development of multiple vaccines, there have been discussions about vaccine hesitancy (7). Although the effectiveness of vaccines depends on their availability, the increasing availability of vaccines has created the problem of VH. Vaccine hesitancy, which ranges from uncertainty about vaccines to outright opposition, was identified by the WHO in 2019 as one of the most important health problems in the world. This hesitancy poses challenges in controlling diseases that vaccines can prevent (8, 9).

Vaccine hesitancy is defined by the WHO as “the delay in the acceptance or refusal to vaccinate despite the availability of vaccine services” (10). Vaccine hesitancy is a complex phenomenon that is influenced by a wide range of contextual, individual, and group factors, including geographical, cultural, and socio-demographic factors, socioeconomic status, and perceptions of risk (1, 11, 12). Several studies explored COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and its determinants in China, Indonesia, Italy, Ireland, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States between March and December 2020 (7). Some of these studies indicated that factors such as age, income, and education levels are associated with a higher likelihood of accepting a vaccine (13–15).

A survey found four important issues: (1) People with chronic diseases worry more about getting COVID-19. (2) People wonder how being vaccinated will affect their chronic disease. (3) Some people are not sure if the COVID-19 vaccine is helpful. (4) There is too much information about COVID-19, and it confuses and worries patients (16).

Several reasons including personal and social are associated with vaccine hesitancy among parents. Gender, nationality, occupation, and being a healthcare worker were factors affecting the vaccination acceptance participants (17). More people were willing to get vaccinated if they trusted the government, had gotten a flu shot before, and saw COVID-19 as a danger to themselves and their community (15, 18–20).

Understanding the factors affecting vaccine hesitancy and identifying effective interventions can help with COVID-19 vaccination coverage and improve the healthcare system’s preparedness to plan and implement policies aimed at improving prevention programs for vaccine-preventable diseases. Many cross-sectional and review studies have been conducted in this field. However, there are few studies that report and synthesize the vaccine hesitancy rate, factors associated with vaccine refusal, and interventions to overcome or decrease vaccine hesitancy. This scoping review aimed to identify and synthesize the available evidence in the three dimensions of vaccine hesitancy rate, effective factors, and interventions to prevent it.

Subjects and methods

Protocol and registration

This scoping review was conducted based on the Joanna Briggs Institute guidelines (21). Furthermore, we reported this study following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) (22).

Eligibility criteria

All original studies that investigated at least one of our domains of vaccine hesitancy or refusal rate, factors associated with hesitancy or refusal of the vaccine, and the ways of interventions to overcome or decrease this phenomenon among the general population were included in this study. All non-English language studies were excluded from the study. We also excluded the studies if the full text was not available through database search or contact with authors.

Information sources and search

Our search was conducted from 1 January 2020 to 1 January 2023 in three electronic databases: PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science (WoS), using a combination of MeSH terms and free terms. Our general keywords were as follows: COVID-19, vaccine, and hesitancy. Full search strategies for databases are available in Supplementary material S1. We also searched the references of the included studies.

Selection of sources of evidence

All records were imported to EndNote software version 20, and duplicates were removed. Two independent reviewers piloted screening with a random sample of 10 studies based on eligibility criteria (agreement rate: 93%), and disagreements were resolved with a third reviewer. Then, they started screening based on title, abstract, and full text. The final included studies were entered into the charting process.

Data charting process and data items

To increase the agreement between reviewers, a data charting form was developed and independently piloted on a random sample of 10 included articles. This form includes data items of the first author, corresponding author, publication year, study design, country of origin, data collection period, participant group, sample size, ethical approval, funding statement, mean age, gender percent, the objective of the study, vaccine hesitancy or refusal rate, factors associated with or affecting hesitancy rate, and interventions to reduce or overcome hesitancy rate. Our definition of hesitancy rate was based on the WHO definition: “delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccines despite availability of vaccination services” (23).

Synthesis of results

We categorized included studies by whether the major focus was vaccine hesitancy. The main domains were vaccine hesitancy rate, factors associated with vaccine hesitancy, and interventions to reduce or overcome hesitancy. The data were charted using tables and figures. Furthermore, we performed a content analysis using the 3C (Confidence, Complacency, and Convenience) model of vaccine hesitancy that was previously introduced by the WHO for categorizing the factors associated with vaccine hesitancy (24).

Patient and public involvement

As our design is a scoping review, patients or the public were not involved in any stage of the study including design, data collection, synthesis, reporting, and dissemination of this research.

Results

Selection of sources of evidence

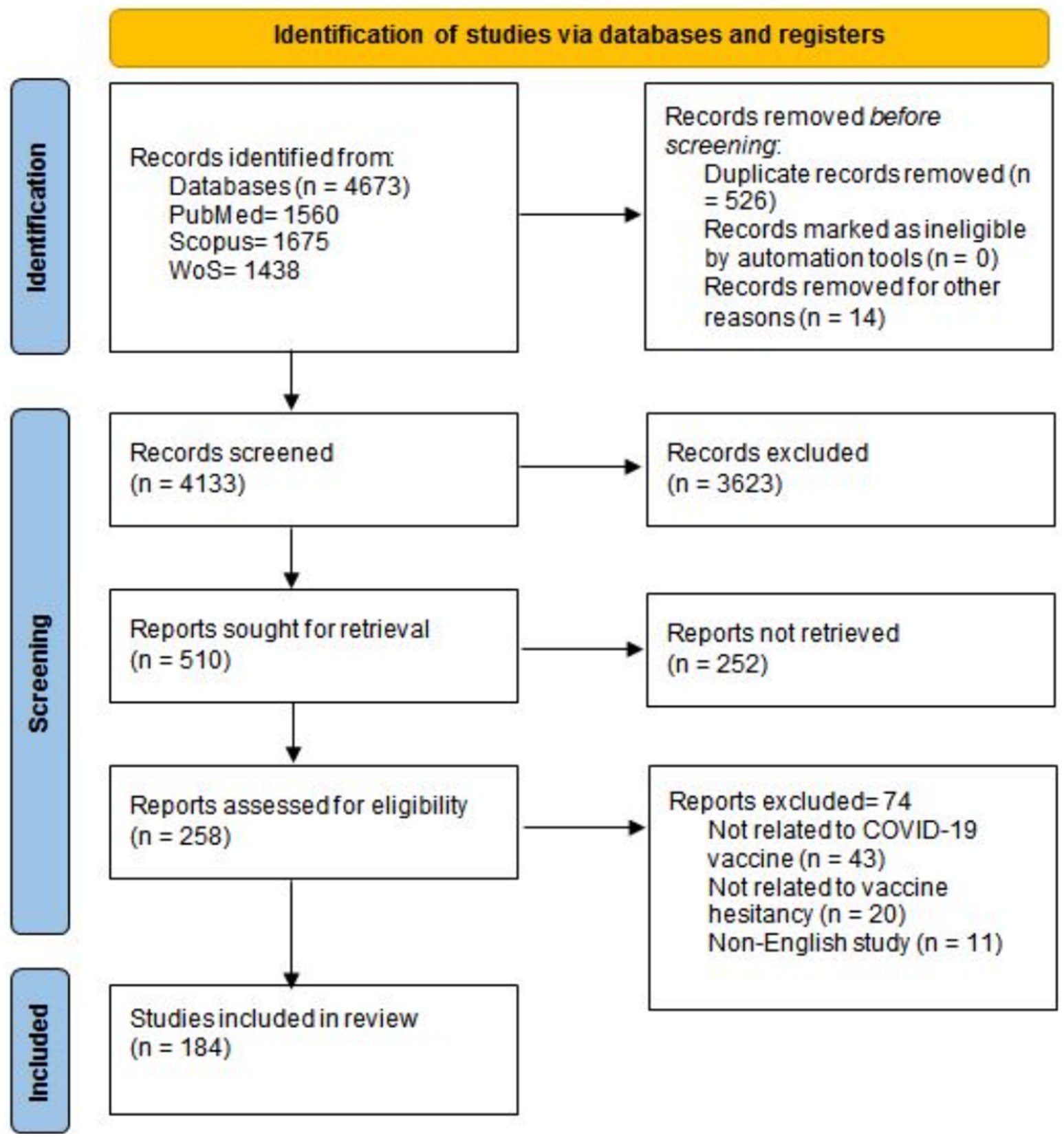

Our database search resulted in 4673 records. After duplication and initial screening, 258 records met the eligibility criteria and were considered for full-text screening. Finally, 184 articles were included in this scoping review (5, 7, 12, 25–197). The PRISMA flow diagram of the study selection process is represented in Figure 1.

Characteristics of sources of evidence

Studies were conducted across five continents: 60 from the Americas, 58 from Asia, 38 from Europe, 11 from Africa, and 4 from Oceania. Thirteen studies were multinational, 51 studies (27.7%) were conducted in the USA, and 14 studies were conducted in China (7.6%). The distribution of the included studies between countries is represented in Figure 2.

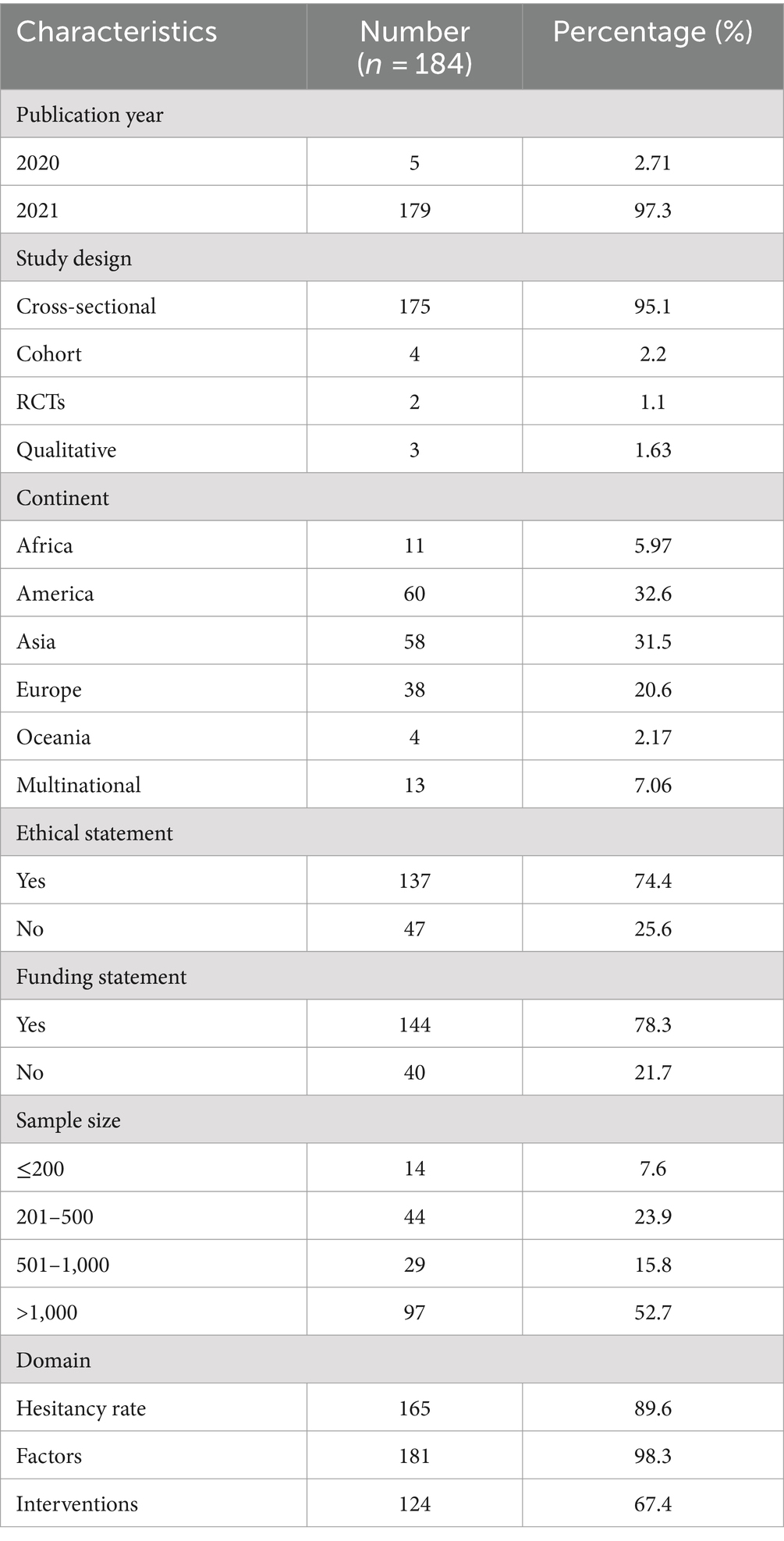

Of the 184 included studies, 175 were cross-sectional, 4 were cohort, 3 were qualitative, and 2 were randomized clinical trials (RCTs). The highest number of articles published in 2021 was 179. Funding and ethical statements were reported in 144 and 137 studies, respectively. The sample size of the included studies ranged from 20 to more than 1 million. Of the 184 included studies, 165 (89.6%) reported the hesitancy rate regarding COVID-19 vaccines, 181 (98.3%) reported the factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, and 124 (67.4%) reported potential interventions to reduce or overcome COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among participants. The summary characteristics of the included studies are reported in Table 1.

The hesitancy rate of the vaccine was different among the studies depending on the type of population, sample size, and method of conducting the study, and it ranged from less than 3% to more than 80%. Factors affecting vaccine hesitancy and interventions suggested by individual studies to overcome it are reported in Supplementary materials S2, S3.

Synthesis of results

Factors affecting the hesitancy rate are categorized into 4 themes and 18 sub-themes including contextual factors, confidence barriers, complacency barriers, and convenience barriers. Contextual factors include two main sub-themes: socio-demographic predictors and political-economic-cultural factors. Confidence barriers include seven main sub-themes: vaccine effectiveness and efficiency; fear and concerns about vaccine development; fear and concerns about side effects, adverse events, and death after vaccination; reliability and trustworthiness of received information from the vaccine program; confidence in safety; trust in authorities, providers, and institutions; and trust in science. Complacency barriers include two main sub-themes: beliefs about identifying the severity and risk of COVID-19 and preference for alternative immunity methods. Convenience barriers to getting vaccinated include being able to physically go and get vaccinated, being able to afford it, living in an area where it is available, understanding health information, having access to good vaccination services, finding the time and place to get vaccinated, and considering cultural factors. The overall themes, sub-themes, and code summary are reported in Table 2.

Discussion

Overall, 184 articles were included in this scoping review. These articles report at least one of our domains investigated in this review including hesitancy rate, factor effecting, and strategy to prevent or reduce hesitancy regarding COVID-19 vaccines. Of the 184 included studies, 165 (89.6%) reported the hesitancy rate regarding COVID-19 vaccines, 181 (98.3%) reported the factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, and 124 (67.4%) reported potential interventions to reduce or overcome COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among participants. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy varied significantly based on the population, sample size, and method of conducting the studies, with reported rates ranging from less than 3% to more than 80% in the included studies. In addition, the main factors affecting the hesitancy rate were categorized into four groups: contextual factors, confidence barriers, complacency barriers, and convenience barriers. Public education campaigns, consultation programs, patient engagement, providing detailed information and shared decision-making programs, streaming educational content through media and broadcast channels, strengthening positive attitudes to vaccination, and reducing conspiracy suspicions were among the important interventions to reduce vaccine hesitancy during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Vaccine hesitancy rate

The rate of vaccine hesitancy was different among the studies depending on the type of population, sample size, and method of conducting the study, and it ranged from less than 3% to more than 80%. The findings of several systematic and scoping reviews are consistent with our results.

Our results were comparable to those of a scoping review conducted by Ackah et al. on an African population. Based on their results, the vaccine acceptance rate ranged from 6.9 to 97.9% (198). Another systematic review conducted by Sallam showed similar results, indicating that the highest COVID-19 vaccine acceptance rate was 97% in Ecuador, while the lowest was 23.6% in Kuwait (199).

The results of a scoping review that was conducted in high-income countries also showed a similar result to our study. Based on this scoping review, the rates of vaccine hesitancy across high-income countries or regions ranged from 7 to 77.9% (200). Furthermore, the results of a worldwide scoping review of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy showed that people in different countries had varying percentages of vaccine uptake (28–86.1%), vaccine hesitancy (10–57.8%), and vaccine refusal (0–24%) (201).

Factor associated

In various studies, several factors have been mentioned that are related to not accepting the vaccine or accepting the vaccine in the case of COVID-19. These influencing factors have been different depending on the geographical context; the participants; demographic characteristics of the population; background factors; and other cultural, social, economic, and political factors in the studies. However, many of these factors have been similar in different studies, and even their causal relationships have been investigated.

A study was carried out to explore the level and factors contributing to COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in South Africa in order to guide the development of interventions to combat it. The study found that COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in South Africa is primarily influenced by social factors such as age, race, education, politics, location, and employment status (202). Another study identified socio-demographic factors as the individual determinants of vaccine hesitancy. Right-wing political affiliation was the main socio-demographic psychological determinant (89). Political affiliation was identified as one of the contextual factors in our findings.

A narrative review was conducted to explore and examine the issue of vaccine hesitancy amid the COVID-19 pandemic. The review identified various factors that impact individuals’ decisions to accept or reject vaccines, such as ethnicity, employment status, religious beliefs, political views, gender, age, education level, income, and other factors (203).

A scoping review was carried out on 60 studies from around the world to explore vaccine hesitancy and acceptance. Through qualitative analysis, this study identified factors that influence people’s decisions on vaccination in various cultural and demographic settings. These factors include risk perceptions, trust in healthcare systems, solidarity, past experiences with vaccines, misinformation, concerns about vaccine side effects, and political beliefs, all of which play a role in addressing or reducing vaccine hesitancy (204).

The WHO acknowledges that vaccine hesitancy poses a significant risk to public health. A recent study investigated how attitudes, norms, and perceived behavioral control influence vaccination intentions. The study found that these factors were important predictors of vaccination intentions, with attitude being the most influential (205). In our study, a positive attitude toward the government has been mentioned as an effective factor in vaccine hesitancy.

Vaccine hesitancy, characterized by a lack of trust in vaccinations and/or indifference toward them, can result in postponing or rejecting vaccination even when it is accessible. This poses a significant risk to the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccination initiatives. Factors such as the quick development of vaccines, misinformation spread through mainstream and social media, the divided socio-political climate, and the challenges of implementing widespread vaccination campaigns may erode confidence in vaccination and heighten apathy toward COVID-19 vaccination efforts (206).

Various factors that impact the decision-making process regarding vaccines are diverse, intricate, and dependent on the specific context. These factors can be triggered or exacerbated by unregulated online information or misinformation. Kassianos et al. (207) addressed the most common concerns regarding the COVID-19 vaccination. The rise of new variants of COVID-19 has contributed to vaccine hesitancy. Healthcare professionals, who are considered reliable sources of information, need to be provided with sufficient resources and practical advice to help them address concerns effectively (207). Advice and recommendations from health professionals about getting or not getting vaccinated were discussed as one of the effective factors in vaccine hesitancy.

Although vaccination has proven to be an effective tool in combating the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic, vaccine hesitancy has become a significant challenge in various countries, including Africa. A scoping review was conducted to consolidate the current research on vaccine hesitancy in Africa. The primary reasons for hesitancy included worries about vaccine safety and potential side effects, distrust in pharmaceutical companies, and exposure to misinformation or contradictory information from the media. Factors linked to a more favorable view of vaccines included being male, having a higher education level, and a fear of contracting the virus (198). These reasons were also discussed in our findings.

According to the classification of the WHO model, health and language literacy is one of the convenience barriers, which includes negative stories, misinformation, and misperceptions focusing on the vaccine and personal knowledge. A study examined the frequency and reasons behind COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among individuals with mental health conditions. Common factors contributing to hesitancy include distrust, false information, belief in conspiracy theories, and negative views on vaccines. Mental health disorders, particularly anxiety and phobias, may heighten the likelihood of vaccine hesitancy (208).

Vaccine hesitancy is a significant obstacle to the acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine. A scoping review was conducted to summarize the rates of COVID-19 hesitancy and its determinants in affluent countries or regions. Factors such as younger age, gender, non-white ethnicity, and lower education levels were commonly linked to increased vaccine hesitancy. Other factors included not having a recent history of influenza vaccination, a lower perceived risk of contracting COVID-19, less fear of the virus, belief in the mildness of COVID-19, and absence of chronic medical conditions. Specific concerns about vaccine safety and effectiveness, as well as worries about the rapid development of COVID-19 vaccines, were also associated with increased vaccine hesitancy (200). All these factors are consistent with our findings.

Strategies to overcome

Considering the wide range of factors affecting vaccine hesitancy, various studies have proposed various interventions to overcome this issue. These interventions have been at various levels, including media, service delivery, community education, and even decision-making processes.

One of the important interventions that has been mentioned in many studies is holding various campaigns to educate people at the community, individual, and family level (28, 66, 134). Some of these training campaigns have been focused on equipping service providers and health sector employees, empowering them to effectively transfer this knowledge to the general public (42). In some of these campaigns, the target population has included less privileged and less educated people because some studies have shown that the level of education is one of the factors affecting knowledge and attitude in this field (47). The way of conducting these campaigns has also been different. In some cases, campaigns have been organized at the community level, following the principles of prevention. Some other campaigns have been held online through media due to the COVID-19 situation (32, 171).

Another recommended intervention in this field has been holding counseling sessions and establishing hotlines to communicate with consultants in the field of public health. In some societies, this disease is considered a kind of stigma, making online communication and telephone consultations very welcome due to the confidentiality and anonymity they offer. On the other hand, some obstacles that exist in face-to-face communication, such as the shyness of raising the issue, are reduced in such a mode of communication, and people raise relevant issues more easily (88, 186, 209).

Another important intervention for reducing vaccine hesitancy is holding educational workshops to explain the advantages and disadvantages of vaccination for different target populations. By holding such workshops and training programs, while increasing people’s awareness, people are given the opportunity to know the advantages and disadvantages of an intervention and decide whether or not to receive it. In this regard, communication between doctors and patients is crucial, as because healthcare professionals are important sources for increasing confidence in vaccination. Patients tend to trust these individuals more, which facilitates acceptance of their recommendations (81, 114, 174).

Some studies showed that recommending vaccination and presenting its advantages and disadvantages through celebrities can have good effects on the general population due to their fame and followers (91). Furthermore, advertising during major events featuring celebrities can also help in this area. However, due to the conditions surrounding this disease and the need to maintain preventive measures, many of these events were held in closed settings at that time, which may have reduced their effectiveness (60, 149).

Conclusion

Based on our study, the vaccine hesitancy rate and the factors affecting it vary across different populations, contexts, and data collection methods. This underscores the need for further investigation in specific populations and contexts. The need to conduct studies at the national and international levels regarding the reasons for vaccine refusal, the factors affecting it, and ways to deal with it is still pending. Designing a comprehensive tool will facilitate comparisons between different populations and different locations. Health and medicine authorities should strengthen the dissemination of vaccination-related knowledge for patients such as an expert consensus or guidelines through various media. Some key points should be emphasized in the knowledge sharing about vaccination, including the importance of vaccination, the safety and side effects of COVID-19 vaccines, and predictions regarding epidemiological trends of COVID-19.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

RB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft. MS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft. MA-Z: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1382849/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Lazarus, JV, Wyka, K, White, TM, Picchio, CA, Gostin, LO, Larson, HJ, et al. A survey of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance across 23 countries in. Nat Med. (2022) 29:366–75. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-02185-4

2. Pandher, R, and Bilszta, JL. Novel COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and acceptance, and associated factors, amongst medical students: a scoping review. Med Educ Online. (2023) 28:2175620. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2023.2175620

3. AlShurman, BA, and Butt, ZA. Proposing a new conceptual Syndemic framework for COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: a narrative review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2023) 20:1561. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20021561

4. Cénat, JM, Noorishad, PG, Moshirian Farahi, SMM, Darius, WP, Mesbahi El Aouame, A, Onesi, O, et al. Prevalence and factors related to COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and unwillingness in Canada: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Virol. (2023) 95:e28156. doi: 10.1002/jmv.28156

5. Carcelen, AC, Prosperi, C, Mutembo, S, Chongwe, G, Mwansa, FD, Ndubani, P, et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Zambia: a glimpse at the possible challenges ahead for COVID-19 vaccination rollout in sub-Saharan Africa. Hum Vaccin Immunother. (2022) 18:1–6. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1948784

6. Rancher, C, Moreland, AD, Smith, DW, Cornelison, V, Schmidt, MG, Boyle, J, et al. Using the 5C model to understand COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy across a national and South Carolina sample. J Psychiatr Res. (2023) 160:180–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2023.02.018

7. Soares, P, Rocha, JV, Moniz, M, Gama, A, Laires, PA, Pedro, AR, et al. Factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Vaccine. (2021) 9:300. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9030300

8. Mahato, P, Adhikari, B, Marahatta, SB, Bhusal, S, Kunwar, K, Yadav, RK, et al. Perceptions around COVID-19 and vaccine hesitancy: a qualitative study in Kaski district, Western Nepal. PLOS Glob Public Health. (2023) 3:e0000564. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0000564

9. Mundagowa, PT, Tozivepi, SN, Chiyaka, ET, Mukora-Mutseyekwa, F, and Makurumidze, R. Assessment of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among Zimbabweans: a rapid national survey. PLoS One. (2022) 17:e0266724. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0266724

10. Organization WH. Report of the SAGE working groups on vaccine hesitancy. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization (2014).

11. MacDonald, NE. Vaccine hesitancy: definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. (2015) 33:4161–4. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036

12. Mejri, N, Berrazega, Y, Ouertani, E, Rachdi, H, Bohli, M, Kochbati, L, et al. Understanding COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and resistance: another challenge in cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. (2022) 30:289–93. doi: 10.1007/s00520-021-06419-y

13. Fisher, KA, Bloomstone, SJ, Walder, J, Crawford, S, Fouayzi, H, and Mazor, KM. Attitudes toward a potential SARS-CoV-2 vaccine: a survey of US adults. Ann Intern Med. (2020) 173:964–73. doi: 10.7326/M20-3569

14. Lin, C, Tu, P, and Beitsch, LM. Confidence and receptivity for COVID-19 vaccines: a rapid systematic review. Vaccine. (2020) 9:16. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9010016

15. Reiter, PL, Pennell, ML, and Katz, ML. Acceptability of a COVID-19 vaccine among adults in the United States: how many people would get vaccinated? Vaccine. (2020) 38:6500–7. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.08.043

16. Choi, T, Chan, B, Grech, L, Kwok, A, Webber, K, Wong, J, et al. Factors influencing COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among patients with serious chronic illnesses during the initial Australian vaccine rollout: a multi-Centre qualitative analysis using the health belief model. Vaccine. (2023) 11:239. doi: 10.3390/vaccines11020239

17. Khatrawi, EM, and Sayed, AA. The reasons behind COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy among the parents of children aged between 5 to 11 years old in Saudi Arabia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2023) 20:1345. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20021345

18. Wang, J, Jing, R, Lai, X, Zhang, H, Lyu, Y, Knoll, MD, et al. Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Vaccine. (2020) 8:482. doi: 10.3390/vaccines8030482

19. Harapan, H, Wagner, AL, Yufika, A, Winardi, W, Anwar, S, Gan, AK, et al. Acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine in Southeast Asia: a cross-sectional study in Indonesia. Front Public Health. (2020) 8:381. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00381

20. Yoda, T, and Katsuyama, H. Willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccination in Japan. Vaccine. (2021) 9:48. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9010048

21. Peters, MD, Godfrey, CM, McInerney, P, Soares, CB, Khalil, H, and Parker, D. The Joanna Briggs institute reviewers' manual 2015 methodology for JBI scoping reviews. (The Joanna Briggs Institute) (2015). Available at: https://repositorio.usp.br/directbitstream/5e8cac53-d709-4797-971f-263153570eb5/SOARES%2C+C+B+doc+150

22. Tricco, AC, Lillie, E, Zarin, W, O'Brien, KK, Colquhoun, H, Levac, D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. (2018) 169:467–73. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850

23. Shen, SC, and Dubey, V. Addressing vaccine hesitancy: clinical guidance for primary care physicians working with parents. Can Fam Physician. (2019) 65:175–81.

24. Afzelius, P, Molsted, S, and Tarnow, L. Intermittent vacuum treatment with VacuMed does not improve peripheral artery disease or walking capacity in patients with intermittent claudication. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. (2018) 78:456–63. doi: 10.1080/00365513.2018.1497803

25. Abdulah, DM. Prevalence and correlates of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the general public in Iraqi Kurdistan: a cross-sectional study. J Med Virol. (2021) 93:6722–31. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27255

26. Abou Leila, R, Salamah, M, and El-Nigoumi, S. Reducing COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy by implementing organizational intervention in a primary care setting in Bahrain. Cureus. (2021) 13. doi: 10.7759/cureus.19282

27. Abouhala, S, Hamidaddin, A, Taye, M, Glass, DJ, Zanial, N, Hammood, F, et al. A national survey assessing COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among Arab Americans. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. (2021) 9:2188–96. doi: 10.1007/s40615-021-01158-6

28. Acheampong, T, Akorsikumah, EA, Osae-Kwapong, J, Khalid, M, Appiah, A, and Amuasi, JH. Examining vaccine hesitancy in sub-Saharan Africa: a survey of the knowledge and attitudes among adults to receive COVID-19 vaccines in Ghana. Vaccine. (2021) 9:814. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9080814

29. Adigwe, OP. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and willingness to pay: emergent factors from a cross-sectional study in Nigeria. Vaccine: X. (2021) 9:100112. doi: 10.1016/j.jvacx.2021.100112

30. Aemro, A, Amare, NS, Shetie, B, Chekol, B, and Wassie, M. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among health care workers in Amhara region referral hospitals, Northwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Epidemiol. Infect. (2021) 149:e225. doi: 10.1017/S0950268821002259

31. Alabdulla, M, Reagu, SM, Al-Khal, A, Elzain, M, and Jones, RM. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and attitudes in Qatar: a national cross-sectional survey of a migrant-majority population. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. (2021) 15:361–70. doi: 10.1111/irv.12847

32. Aldakhil, H, Albedah, N, Alturaiki, N, Alajlan, R, and Abusalih, H. Vaccine hesitancy towards childhood immunizations as a predictor of mothers’ intention to vaccinate their children against COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia. J Infect Public Health. (2021) 14:1497–504. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2021.08.028

33. Alfieri, NL, Kusma, JD, Heard-Garris, N, Davis, MM, Golbeck, E, Barrera, L, et al. Parental COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy for children: vulnerability in an urban hotspot. BMC Public Health. (2021) 21:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11725-5

34. Ali, M, and Hossain, A. What is the extent of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Bangladesh? A cross-sectional rapid national survey. BMJ Open. (2021) 11:e050303. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-050303

35. Alibrahim, J, and Awad, A. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among the public in Kuwait: a cross-sectional survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:8836. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18168836

36. Alkhammash, R, and Abdel-Raheem, A. ‘To get or not to get vaccinated against COVID-19’: Saudi women, vaccine hesitancy, and framing effects. (2022). Available at: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/17504813211043724

37. Allington, D, McAndrew, S, Moxham-Hall, V, and Duffy, B. Coronavirus conspiracy suspicions, general vaccine attitudes, trust and coronavirus information source as predictors of vaccine hesitancy among UK residents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Med. (2023) 53:236–47. doi: 10.1017/S0033291721001434

38. Almaghaslah, D, Alsayari, A, Kandasamy, G, and Vasudevan, R. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among young adults in Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional web-based study. Vaccine. (2021) 9:330. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9040330

39. Al-Mohaithef, M, Padhi, BK, and Ennaceur, S. Socio-demographics correlate of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy during the second wave of COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional web-based survey in Saudi Arabia. Front Public Health. (2021) 9:698106. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.698106

40. Al-Mulla, R, Abu-Madi, M, Talafha, QM, Tayyem, RF, and Abdallah, AM. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in a representative education sector population in Qatar. Vaccine. (2021) 9:665. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9060665

41. Al-Wutayd, O, Khalil, R, and Rajar, AB. Sociodemographic and behavioral predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Pakistan. J Multidiscip Healthc. (2021) 14:2847–56. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S325529

42. Amuzie, CI, Odini, F, Kalu, KU, Izuka, M, Nwamoh, U, Emma-Ukaegbu, U, et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among healthcare workers and its socio-demographic determinants in Abia state, southeastern Nigeria: a cross-sectional study. Pan Afr Med J. (2021) 40:10. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2021.40.10.29816

43. Andrade, G. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, conspiracist beliefs, paranoid ideation and perceived ethnic discrimination in a sample of university students in Venezuela. Vaccine. (2021) 39:6837–42. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.10.037

44. Andrade, G. Predictive demographic factors of Covid-19 vaccine hesitancy in Venezuela: a cross-sectional study. Vacunas (English Edition). (2022) 23:S22–5. doi: 10.1016/j.vacune.2022.08.002

45. Asaoka, H, Koido, Y, Kawashima, Y, Ikeda, M, Miyamoto, Y, and Nishi, D. Longitudinal change in depressive symptoms among healthcare professionals with and without COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy from October 2020 to June 2021 in Japan. Ind Health. (2021) 60:387–94. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.2021-0164

46. Ashok, N, Krishnamurthy, K, Singh, K, Rahman, S, Majumder, MAA, and Majumder, MA. High COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among healthcare workers: should such a trend require closer attention by policymakers? Cureus. (2021) 13. doi: 10.7759/cureus.17990

47. Badr, H, Zhang, X, Oluyomi, A, Woodard, LD, Adepoju, OE, Raza, SA, et al. Overcoming COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: insights from an online population-based survey in the United States. Vaccine. (2021) 9:1100. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9101100

48. Bagasra, AB, Doan, S, and Allen, CT. Racial differences in institutional trust and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and refusal. BMC Public Health. (2021) 21:1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-12195-5

49. Bagateli, LE, Saeki, EY, Fadda, M, Agostoni, C, Marchisio, P, and Milani, GP. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among parents of children and adolescents living in Brazil. Vaccine. (2021) 9:1115. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9101115

50. Baniak, LM, Luyster, FS, Raible, CA, McCray, EE, and Strollo, PJ. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and uptake among nursing staff during an active vaccine rollout. Vaccine. (2021) 9:858. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9080858

51. Barello, S, Nania, T, Dellafiore, F, Graffigna, G, and Caruso, R. ‘Vaccine hesitancy’among university students in Italy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur J Epidemiol. (2020) 35:781–3. doi: 10.1007/s10654-020-00670-z

52. Bass, SB, Wilson-Genderson, M, Garcia, DT, Akinkugbe, AA, and Mosavel, M. SARS-CoV-2 vaccine hesitancy in a sample of US adults: role of perceived satisfaction with health, access to healthcare, and attention to COVID-19 news. Front Public Health. (2021) 9:665724. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.665724

53. Belingheri, M, Roncalli, M, Riva, MA, Paladino, ME, and Teruzzi, CM. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and reasons for or against adherence among dentists. J Am Dent Assoc. (2021) 152:740–6. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2021.04.020

54. Bendau, A, Plag, J, Petzold, MB, and Ströhle, A. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and related fears and anxiety. Int Immunopharmacol. (2021) 97:107724. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2021.107724

55. Berry, SD, Johnson, KS, Myles, L, Herndon, L, Montoya, A, Fashaw, S, et al. Lessons learned from frontline skilled nursing facility staff regarding COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2021) 69:1140–6. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17136

56. Blanchi, S, Torreggiani, M, Chatrenet, A, Fois, A, Mazé, B, Njandjo, L, et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in patients on dialysis in Italy and France. Kidney Int Rep. (2021) 6:2763–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2021.08.030

57. Bogart, LM, Ojikutu, BO, Tyagi, K, Klein, DJ, Mutchler, MG, Dong, L, et al. COVID-19 related medical mistrust, health impacts, and potential vaccine hesitancy among black Americans living with HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. (1999) 86:200–7. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002570

58. Botwe, B, Antwi, W, Adusei, J, Mayeden, R, Akudjedu, T, and Sule, S. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy concerns: findings from a Ghana clinical radiography workforce survey. Radiography. (2022) 28:537–44. doi: 10.1016/j.radi.2021.09.015

59. Caserotti, M, Girardi, P, Rubaltelli, E, Tasso, A, Lotto, L, and Gavaruzzi, T. Associations of COVID-19 risk perception with vaccine hesitancy over time for Italian residents. Soc Sci Med. (2021) 272:113688. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113688

60. Chadwick, A, Kaiser, J, Vaccari, C, Freeman, D, Lambe, S, Loe, BS, et al. Online social endorsement and Covid-19 vaccine hesitancy in the United Kingdom. Social Media Soc. (2021) 7:205630512110088. doi: 10.1177/20563051211008817

61. Chaudhary, FA, Ahmad, B, Khalid, MD, Fazal, A, Javaid, MM, and Butt, DQ. Factors influencing COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and acceptance among the Pakistani population. Hum Vaccin Immunother. (2021) 17:3365–70. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1944743

62. Chen, H, Li, X, Gao, J, Liu, X, Mao, Y, Wang, R, et al. Health belief model perspective on the control of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and the promotion of vaccination in China: web-based cross-sectional study. J Med Internet Res. (2021) 23:e29329. doi: 10.2196/29329

63. Corcoran, KE, Scheitle, CP, and DiGregorio, BD. Christian nationalism and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and uptake. Vaccine. (2021) 39:6614–21. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.09.074

64. Cordina, M, and Lauri, MA. Attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccination, vaccine hesitancy and intention to take the vaccine. Pharm Pract. (2021) 19:2317. doi: 10.18549/PharmPract.2021.1.2317

65. Cotfas, L-A, Delcea, C, and Gherai, R. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the month following the start of the vaccination process. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:10438. doi: 10.3390/ijerph181910438

66. Danabal, KGM, Magesh, SS, Saravanan, S, and Gopichandran, V. Attitude towards COVID 19 vaccines and vaccine hesitancy in urban and rural communities in Tamil Nadu, India–a community based survey. BMC Health Serv Res. (2021) 21:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-07037-4

67. de Sousa, ÁFL, Teixeira, JRB, Lua, I, de Oliveira, SF, Ferreira, AJF, Schneider, G, et al. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Portuguese-speaking countries: a structural equations modeling approach. Vaccine. (2021) 9:1167. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9101167

68. Dinga, JN, Sinda, LK, and Titanji, VP. Assessment of vaccine hesitancy to a COVID-19 vaccine in Cameroonian adults and its global implication. Vaccine. (2021) 9:175. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9020175

69. Doherty, IA, Pilkington, W, Brown, L, Billings, V, Hoffler, U, Paulin, L, et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in underserved communities of North Carolina. PLoS One. (2021) 16:e0248542. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0248542

70. Dror, AA, Eisenbach, N, Taiber, S, Morozov, NG, Mizrachi, M, Zigron, A, et al. Vaccine hesitancy: the next challenge in the fight against COVID-19. Eur J Epidemiol. (2020) 35:775–9. doi: 10.1007/s10654-020-00671-y

71. Du, M, Tao, L, and Liu, J. The association between risk perception and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy for children among reproductive women in China: an online survey. Front Med. (2021) 8:741298. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.741298

72. Duong, TV, Lin, C-Y, Chen, S-C, Huang, Y-K, Okan, O, Dadaczynski, K, et al. Oxford COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in school principals: impacts of gender, well-being, and coronavirus-related health literacy. Vaccine. (2021) 9:985. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9090985

73. Ebrahimi, OV, Johnson, MS, Ebling, S, Amundsen, OM, Halsøy, Ø, Hoffart, A, et al. Risk, trust, and flawed assumptions: vaccine hesitancy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Public Health. (2021) 9:700213. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.700213

74. Edwards, B, Biddle, N, Gray, M, and Sollis, K. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and resistance: correlates in a nationally representative longitudinal survey of the Australian population. PLoS One. (2021) 16:e0248892. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0248892

75. Ehde, DM, Roberts, MK, Humbert, AT, Herring, TE, and Alschuler, KN. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in adults with multiple sclerosis in the United States: a follow up survey during the initial vaccine rollout in 2021. Mult Scler Relat Disord. (2021) 54:103163

76. Ekstrand, ML, Heylen, E, Gandhi, M, Steward, WT, Pereira, M, and Srinivasan, K. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among PLWH in South India: implications for vaccination campaigns. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. (2021) 88:421–5. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002803

77. El-Sokkary, RH, El Seifi, OS, Hassan, HM, Mortada, EM, Hashem, MK, Gadelrab, MRMA, et al. Predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among Egyptian healthcare workers: a cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. (2021) 21:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-06392-1

78. Fedele, F, Aria, M, Esposito, V, Micillo, M, Cecere, G, Spano, M, et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: a survey in a population highly compliant to common vaccinations. Hum Vaccin Immunother. (2021) 17:3348–54. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1928460

79. Fernandes, N, Costa, D, Costa, D, Keating, J, and Arantes, J. Predicting COVID-19 vaccination intention: the determinants of vaccine hesitancy. Vaccine. (2021) 9:1161. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9101161

80. Fernández-Penny, FE, Jolkovsky, EL, Shofer, FS, Hemmert, KC, Valiuddin, H, Uspal, JE, et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among patients in two urban emergency departments. Acad Emerg Med. (2021) 28:1100–7. doi: 10.1111/acem.14376

81. Fisher, KA, Nguyen, N, Crawford, S, Fouayzi, H, Singh, S, and Mazor, KM. Preferences for COVID-19 vaccination information and location: associations with vaccine hesitancy, race and ethnicity. Vaccine. (2021) 39:6591–4. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.09.058

82. Freeman, D, Lambe, S, Yu, L-M, Freeman, J, Chadwick, A, Vaccari, C, et al. Injection fears and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. (2021). doi: 10.1017/S0033291721002609

83. Freeman, D, Loe, BS, Chadwick, A, Vaccari, C, Waite, F, Rosebrock, L, et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK: the Oxford coronavirus explanations, attitudes, and narratives survey (Oceans) II. Psychol Med. (2022) 52:3127–41. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720005188

84. Freeman, D, Loe, BS, Yu, L-M, Freeman, J, Chadwick, A, Vaccari, C, et al. Effects of different types of written vaccination information on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK (OCEANS-III): a single-blind, parallel-group, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Public Health. (2021) 6:e416–27. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00096-7

85. Fridman, A, Gershon, R, and Gneezy, A. COVID-19 and vaccine hesitancy: a longitudinal study. PLoS One. (2021) 16:e0250123. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0250123

86. Gao, X, Li, H, He, W, and Zeng, W. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among medical students: the next COVID-19 challenge in Wuhan, China. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. (2023) 17:e46. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2021.291

87. Gaur, P, Agrawat, H, and Shukla, A. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in patients with systemic autoimmune rheumatic disease: an interview-based survey. Rheumatol Int. (2021) 41:1601–5. doi: 10.1007/s00296-021-04938-9

88. Gehlbach, D, Vázquez, E, Ortiz, G, Li, E, Sánchez, CB, Rodríguez, S, et al. COVID-19 testing and vaccine hesitancy in Latinx farm-working communities in the eastern Coachella Valley (United States: Research square), (2021).

89. Gerretsen, P, Kim, J, Caravaggio, F, Quilty, L, Sanches, M, Wells, S, et al. Individual determinants of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. PLoS One. (2021) 16:e0258462. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0258462

90. Gerussi, V, Peghin, M, Palese, A, Bressan, V, Visintini, E, Bontempo, G, et al. Vaccine hesitancy among Italian patients recovered from COVID-19 infection towards influenza and Sars-Cov-2 vaccination. Vaccine. (2021) 9:172. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9020172

91. Griffith, J, Marani, H, and Monkman, H. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Canada: content analysis of tweets using the theoretical domains framework. J Med Internet Res. (2021) 23:e26874. doi: 10.2196/26874

92. Hamdan, MB, Singh, S, Polavarapu, M, Jordan, TR, and Melhem, N. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among university students in Lebanon. Epidemiol Infect. (2021) 149:e242. doi: 10.1017/S0950268821002314

93. Harrison, J, Berry, S, Mor, V, and Gifford, D. “Somebody like me”: understanding COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among staff in skilled nursing facilities. J Am Med Dir Assoc. (2021) 22:1133–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2021.03.012

94. He, K, Mack, WJ, Neely, M, Lewis, L, and Anand, V. Parental perspectives on immunizations: impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on childhood vaccine hesitancy. J Community Health. (2022) 47:39–52. doi: 10.1007/s10900-021-01017-9

95. Holeva, V, Parlapani, E, Nikopoulou, V, Nouskas, I, and Diakogiannis, I. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in a sample of Greek adults. Psychol Health Med. (2022) 27:113–9. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2021.1948579

96. Hossain, MB, Alam, MZ, Islam, MS, Sultan, S, Faysal, MM, Rima, S, et al. Health belief model, theory of planned behavior, or psychological antecedents: what predicts COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy better among the Bangladeshi adults? Front Public Health. (2021) 9:711066. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.711066

97. Hou, Z, Tong, Y, Du, F, Lu, L, Zhao, S, Yu, K, et al. Assessing COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, confidence, and public engagement: a global social listening study. J Med Internet Res. (2021) 23:e27632. doi: 10.2196/27632

98. Hwang, SE, Kim, W-H, and Heo, J. Socio-demographic, psychological, and experiential predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in South Korea, October-December 2020. Hum Vaccin Immunother. (2022) 18:1–8. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1983389

99. İkiışık, H, Akif Sezerol, M, Taşçı, Y, and Maral, I. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: a community-based research in Turkey. Int J Clin Pract. (2021) 75:e14336. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.14336

100. Jain, J, Saurabh, S, Kumar, P, Verma, MK, Goel, AD, Gupta, MK, et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among medical students in India. Epidemiol Infect. (2021) 149:149. doi: 10.1017/S0950268821001205

101. Jennings, W, Stoker, G, Bunting, H, Valgarðsson, VO, Gaskell, J, Devine, D, et al. Lack of trust, conspiracy beliefs, and social media use predict COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Vaccine. (2021) 9:593. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9060593

102. Jin, Q, Raza, SH, Yousaf, M, Zaman, U, and Siang, JMLD. Can communication strategies combat COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy with trade-off between public service messages and public skepticism? Experimental evidence from Pakistan. Vaccine. (2021) 9:757. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9070757

103. Joshi, A, Sridhar, M, Tenneti, VJD, Devi, V, Sangeetha, K, Nallaperumal, AB, et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in healthcare workers amidst the second wave of the pandemic in India: a single Centre study. Cureus. (2021) 13. doi: 10.7759/cureus.17370

104. Khaled, SM, Petcu, C, Bader, L, Amro, I, Al-Hamadi, AMH, Al Assi, M, et al. Prevalence and potential determinants of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and resistance in Qatar: results from a nationally representative survey of Qatari nationals and migrants between December 2020 and January 2021. Vaccine. (2021) 9:471. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9050471

105. Khan, MSR, Watanapongvanich, S, and Kadoya, Y. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among the younger generation in Japan. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:11702. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182111702

106. Khubchandani, J, Sharma, S, Price, JH, Wiblishauser, MJ, and Webb, FJ. COVID-19 morbidity and mortality in social networks: does it influence vaccine hesitancy? Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:9448. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18189448

107. King, WC, Rubinstein, M, Reinhart, A, and Mejia, R. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy January-may 2021 among 18–64 year old US adults by employment and occupation. Prev Med Rep. (2021) 24:101569. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2021.101569

108. Knight, H, Jia, R, Ayling, K, Bradbury, K, Baker, K, Chalder, T, et al. Understanding and addressing vaccine hesitancy in the context of COVID-19: development of a digital intervention. Public Health. (2021) 201:98–107. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2021.10.006

109. Kobayashi, Y, Howell, C, and Heinrich, T. Vaccine hesitancy, state bias, and Covid-19: evidence from a survey experiment using Phase-3 results announcement by BioNTech and Pfizer. Soc Sci Med. (2021) 282:114115. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114115

110. Kose, S, Mandiracioglu, A, Sahin, S, Kaynar, T, Karbus, O, and Ozbel, Y. Vaccine hesitancy of the COVID-19 by health care personnel. Int J Clin Pract. (2021) 75:e13917. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.13917

111. Kumar, R, Alabdulla, M, Elhassan, NM, and Reagu, SM. Qatar healthcare workers' COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and attitudes: a national cross-sectional survey. Front Public Health. (2021) 9:727748. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.727748

112. Kwok, KO, Li, K-K, Wei, WI, Tang, A, Wong, SYS, and Lee, SS. Influenza vaccine uptake, COVID-19 vaccination intention and vaccine hesitancy among nurses: a survey. Int J Nurs Stud. (2021) 114:103854. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103854

113. Lamot, M, Krajnc, MT, and Kirbiš, A. DEMOGRaphic and socioeconomic characteristics, health status and political orientation as predictors of covid-19 vaccine hesitancy among the slovenian public. Druzboslovne Razprave. (2020) 36

114. Li, PC, Theis, SR, Kelly, D, Ocampo, T, Berglund, A, Morgan, D, et al. Impact of an education intervention on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in a military base population. Mil Med. (2022) 187:e1516–22. doi: 10.1093/milmed/usab363

115. Liu, H, Zhou, Z, Tao, X, Huang, L, Zhu, E, Yu, L, et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among Chinese residents under the free vaccination policy. Rev Assoc Med Bras. (2021) 67:1317–21. doi: 10.1590/1806-9282.20210633

116. Liu, R, and Li, GM. Hesitancy in the time of coronavirus: temporal, spatial, and sociodemographic variations in COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. SSM Popul Health. (2021) 15:100896. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100896

117. Lockyer, B, Islam, S, Rahman, A, Dickerson, J, Pickett, K, Sheldon, T, et al. Understanding COVID-19 misinformation and vaccine hesitancy in context: findings from a qualitative study involving citizens in Bradford, UK. Health Expect. (2021) 24:1158–67. doi: 10.1111/hex.13240

118. Longchamps, C, Ducarroz, S, Crouzet, L, Vignier, N, Pourtau, L, Allaire, C, et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among persons living in homeless shelters in France. Vaccine. (2021) 39:3315–8. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.05.012

119. Lu, F, and Sun, Y. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: the effects of combining direct and indirect online opinion cues on psychological reactance to health campaigns. Comput Hum Behav. (2022) 127:107057. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2021.107057

120. Lu, X, Wang, J, Hu, L, Li, B, and Lu, Y. Association between adult vaccine hesitancy and parental acceptance of childhood COVID-19 vaccines: a web-based survey in a northwestern region in China. Vaccine. (2021) 9:1088. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9101088

121. Lucia, VC, Kelekar, A, and Afonso, NM. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among medical students. J Public Health. (2021) 43:445–9. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdaa230

122. Mahdi, BM. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and acceptance among medical students: an online cross-sectional study in Iraq. Open access Macedonian. J Med Sci. (2021) 9:955–8. doi: 10.3889/oamjms.2021.7399

123. Mangla, S, Zohra Makkia, FT, Pathak, AK, Robinson, R, Sultana, N, Koonisetty, KS, et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and emerging variants: evidence from six countries. Behav Sci. (2021) 11:148. doi: 10.3390/bs11110148

124. Maraqa, B, Nazzal, Z, Rabi, R, Sarhan, N, Al-Shakhra, K, and Al-Kaila, M. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among health care workers in Palestine: a call for action. Prev Med. (2021) 149:106618. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106618

125. McElfish, PA, Willis, DE, Shah, SK, Bryant-Moore, K, Rojo, MO, and Selig, JP. Sociodemographic determinants of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, fear of infection, and protection self-efficacy. J Prim Care Community Health. (2021) 12:215013272110407. doi: 10.1177/21501327211040746

126. Mohan, S, Reagu, S, Lindow, S, and Alabdulla, M. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in perinatal women: a cross sectional survey. J Perinat Med. (2021) 49:678–85. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2021-0069

127. Mollalo, A, and Tatar, M. Spatial modeling of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the United States. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:9488. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18189488

128. Momplaisir, FM, Kuter, BJ, Ghadimi, F, Browne, S, Nkwihoreze, H, Feemster, KA, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among health care workers in 2 large academic hospitals. JAMA Netw Open. (2021) 4:e2121931. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.21931

129. Monami, M, Gori, D, Guaraldi, F, Montalti, M, Nreu, B, Burioni, R, et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and early adverse events reported in a cohort of 7,881 Italian physicians. Ann Ig. (2021) 34:344–357. doi: 10.7416/ai.2021.2491

130. Moore, DCBC, Nehab, MF, Camacho, KG, Reis, AT, de Fátima, J-MM, Abramov, DM, et al. Low COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Brazil. Vaccine. (2021) 39:6262–8. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.09.013

131. Muhajarine, N, Adeyinka, DA, McCutcheon, J, Green, KL, Fahlman, M, and Kallio, N. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and refusal and associated factors in an adult population in Saskatchewan, Canada: evidence from predictive modelling. PLoS One. (2021) 16:e0259513. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0259513

132. Muric, G, Wu, Y, and Ferrara, E. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy on social media: building a public twitter data set of antivaccine content, vaccine misinformation, and conspiracies. JMIR Public Health Surveill. (2021) 7:e30642. doi: 10.2196/30642

133. Murphy, J, Vallières, F, Bentall, RP, Shevlin, M, McBride, O, Hartman, TK, et al. Psychological characteristics associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and resistance in Ireland and the United Kingdom. Nat Commun. (2021) 12:29. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-20226-9

134. Musa, S, Dergaa, I, Abdulmalik, MA, Ammar, A, Chamari, K, and Saad, HB. BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among parents of 4023 young adolescents (12–15 years) in Qatar. Vaccine. (2021) 9:981. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9090981

135. Navarre, C, Roy, P, Ledochowski, S, Fabre, M, Esparcieux, A, Issartel, B, et al. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in French hospitals. Infect Dis Now. (2021) 51:647–53. doi: 10.1016/j.idnow.2021.08.004

136. Nazlı, ŞB, Yığman, F, Sevindik, M, and Deniz, ÖD. Psychological factors affecting COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Ir J Med Sci (1971 -). (2022) 191:71–80. doi: 10.1007/s11845-021-02640-0

137. Nguyen, LH, Joshi, AD, Drew, DA, Merino, J, Ma, W, Lo, C-H, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and uptake medrxiv, (United States: medrxiv) (2021).

138. Okoro, O, Kennedy, J, Simmons, G, Vosen, EC, Allen, K, Singer, D, et al. Exploring the scope and dimensions of vaccine hesitancy and resistance to enhance COVID-19 vaccination in black communities. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. (2021) 9:2117–30. doi: 10.1007/s40615-021-01150-0

139. Okubo, R, Yoshioka, T, Ohfuji, S, Matsuo, T, and Tabuchi, T. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and its associated factors in Japan. Vaccine. (2021) 9:662. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9060662

140. Oliveira, BLCA, Campos, MAG, Queiroz, RCS, Souza, BF, Santos, AM, and Silva, AAM. Prevalence and factors associated with covid-19 vaccine hesitancy in Maranhão, Brazil. Rev Saude Publica. (2021) 55:12. doi: 10.11606/s1518-8787.2021055003417

141. Palamenghi, L, Barello, S, Boccia, S, and Graffigna, G. Mistrust in biomedical research and vaccine hesitancy: the forefront challenge in the battle against COVID-19 in Italy. Eur J Epidemiol. (2020) 35:785–8. doi: 10.1007/s10654-020-00675-8

142. Paris, C, Bénézit, F, Geslin, M, Polard, E, Baldeyrou, M, Turmel, V, et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among healthcare workers. Infect Dis Now. (2021) 51:484–7. doi: 10.1016/j.idnow.2021.04.001

143. Park, HK, Ham, JH, Jang, DH, Lee, JY, and Jang, WM. Political ideologies, government trust, and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in South Korea: a cross-sectional survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:10655. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182010655

144. Prickett, KC, Habibi, H, and Carr, PA. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and acceptance in a cohort of diverse new Zealanders. Lancet Reg Health Western Pacific. (2021) 14:100241. doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2021.100241

145. Purnell, M, Maxwell, T, Hill, S, Patel, R, Trower, J, Wangui, L, et al. Exploring COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy at a rural historically black college and university. J Am Pharm Assoc. (2022) 62:340–4. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2021.09.008

146. Puteikis, K, and Mameniškienė, R. Factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among people with epilepsy in Lithuania. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:4374. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18084374

147. Qunaibi, EA, Helmy, M, Basheti, I, and Sultan, I. A high rate of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in a large-scale survey on Arabs. eLife. (2021) 10:e68038. doi: 10.7554/eLife.68038

148. Ramonfaur, D, Hinojosa-González, DE, Rodriguez-Gomez, GP, Iruegas-Nuñez, DA, and Flores-Villalba, E. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and acceptance in Mexico: a web-based nationwide survey. Rev Panam Salud Publica. (2021) 45:1. doi: 10.26633/RPSP.2021.133

149. Reno, C, Maietti, E, Di Valerio, Z, Montalti, M, Fantini, MP, and Gori, D. Vaccine hesitancy towards COVID-19 vaccination: investigating the role of information sources through a mediation analysis. Infect Dis Rep. (2021) 13:712–23. doi: 10.3390/idr13030066

150. Rezende, RPV, Braz, AS, Guimarães, MFB, Ribeiro, SLE, Vieira, RMRA, Bica, BE, et al. Characteristics associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: a nationwide survey of 1000 patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. Vaccine. (2021) 39:6454–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.09.057

151. Riad, A, Abdulqader, H, Morgado, M, Domnori, S, Koščík, M, Mendes, JJ, et al. Global prevalence and drivers of dental students’ COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Vaccine. (2021) 9:566. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9060566

152. Robertson, E, Reeve, KS, Niedzwiedz, CL, Moore, J, Blake, M, Green, M, et al. Predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK household longitudinal study. Brain Behav Immun. (2021) 94:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2021.03.008

153. Rodriguez, VJ, Alcaide, ML, Salazar, AS, Montgomerie, EK, Maddalon, MJ, and Jones, DL. Psychometric properties of a vaccine hesitancy scale adapted for COVID-19 vaccination among people with HIV. AIDS Behav. (2022) 26:96–101. doi: 10.1007/s10461-021-03350-5

154. Rozek, LS, Jones, P, Menon, A, Hicken, A, Apsley, S, and King, EJ. Understanding vaccine hesitancy in the context of COVID-19: the role of trust and confidence in a seventeen-country survey. Int J Public Health. (2021) 66:636255. doi: 10.3389/ijph.2021.636255

155. Sadaqat, W, Habib, S, Tauseef, A, Akhtar, S, Hayat, M, Shujaat, SA, et al. Determination of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among university students. Cureus. (2021) 13. doi: 10.7759/cureus.17283

156. Saied, SM, Saied, EM, Kabbash, IA, and Abdo, SAEF. Vaccine hesitancy: beliefs and barriers associated with COVID-19 vaccination among Egyptian medical students. J Med Virol. (2021) 93:4280–91. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26910

157. Sallam, M, Dababseh, D, Eid, H, Al-Mahzoum, K, Al-Haidar, A, Taim, D, et al. High rates of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and its association with conspiracy beliefs: a study in Jordan and Kuwait among other Arab countries. Vaccine. (2021) 9:42. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9010042

158. Saluja, S, Lam, CN, Wishart, D, McMorris, A, Cousineau, MR, and Kaplan, CM. Disparities in COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among Los Angeles County adults after vaccine authorization. Prev Med Rep. (2021) 24:101544. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2021.101544

159. Savoia, E, Piltch-Loeb, R, Goldberg, B, Miller-Idriss, C, Hughes, B, Montrond, A, et al. Predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: socio-demographics, co-morbidity, and past experience of racial discrimination. Vaccine. (2021) 9:767. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9070767

160. Schernhammer, E, Weitzer, J, Laubichler, MD, Birmann, BM, Bertau, M, Zenk, L, et al. Correlates of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Austria: trust and the government. J Public Health. (2022) 44:e106–16. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdab122

161. Schwarzinger, M, Watson, V, Arwidson, P, Alla, F, and Luchini, S. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in a representative working-age population in France: a survey experiment based on vaccine characteristics. Lancet Public Health. (2021) 6:e210–21. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00012-8

162. Sharma, M, Batra, K, and Batra, R. A theory-based analysis of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among African Americans in the United States: a recent evidence. Healthcare. (2021) 9:1273. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9101273

163. Siegler, AJ, Luisi, N, Hall, EW, Bradley, H, Sanchez, T, Lopman, BA, et al. Trajectory of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy over time and association of initial vaccine hesitancy with subsequent vaccination. JAMA Netw Open. (2021) 4:e2126882–e2126882. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.26882

164. Silva, J, Bratberg, J, and Lemay, V. COVID-19 and influenza vaccine hesitancy among college students. J Am Pharm Assoc. (2021) 61:709–714.e1. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2021.05.009

165. Smith-Norowitz, TA, Silverberg, JI, Norowitz, EM, Kohlhoff, S, and Hammerschlag, MR. Factors impacting vaccine hesitancy toward coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) vaccination in Brooklyn, New York. Hum Vaccin Immunotherap. (2021) 17:4013–4. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1948786

166. Solak, Ç, Peker-Dural, H, Karlıdağ, S, and Peker, M. Linking the behavioral immune system to COVID-19 vaccination intention: the mediating role of the need for cognitive closure and vaccine hesitancy. Personal Individ Differ. (2022) 185:111245. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2021.111245

167. Sowa, P, Kiszkiel, Ł, Laskowski, PP, Alimowski, M, Szczerbiński, Ł, Paniczko, M, et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Poland—multifactorial impact trajectories. Vaccine. (2021) 9:876. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9080876

168. Stoler, J, Enders, AM, Klofstad, CA, and Uscinski, JE. The limits of medical trust in mitigating COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among black Americans. J Gen Intern Med. (2021) 36:3629–31. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-06743-3

169. Talmy, T, Cohen, B, Nitzan, I, and Ben, MY. Primary care interventions to address COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among Israel defense forces soldiers. J Community Health. (2021) 46:1155–60. doi: 10.1007/s10900-021-01002-2

170. Thaker, J. The persistence of vaccine hesitancy. (United States: COVID-19 vaccination intention. medRxiv) (2020):2020.

171. Thaker, J, and Subramanian, A. Exposure to COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy is as impactful as vaccine misinformation in inducing a decline in vaccination intentions in New Zealand: results from pre-post between-groups randomized block experiment. Front Commun. (2021) 6:721982. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2021.721982

172. Thanapluetiwong, S, Chansirikarnjana, S, Sriwannopas, O, Assavapokee, T, and Ittasakul, P. Factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Thai seniors. Patient Prefer Adherence. (2021) 15:2389–403. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S334757

173. Thelwall, M, Kousha, K, and Thelwall, S. Covid-19 vaccine hesitancy on English-language twitter. Profesional de la información (England: EPI). (2021);30.

174. Townsel, C, Moniz, MH, Wagner, AL, Zikmund-Fisher, BJ, Hawley, S, Jiang, L, et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among reproductive-aged female tier 1A healthcare workers in a United States medical center. J Perinatol. (2021) 41:2549–51. doi: 10.1038/s41372-021-01173-9

175. Tram, KH, Saeed, S, Bradley, C, Fox, B, Eshun-Wilson, I, Mody, A, et al. Deliberation, dissent, and distrust: understanding distinct drivers of coronavirus disease 2019 vaccine hesitancy in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. (2022) 74:1429–41. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab633

176. Trent, M, Seale, H, Chughtai, AA, Salmon, D, and MacIntyre, CR. Trust in government, intention to vaccinate and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: a comparative survey of five large cities in the United States, United Kingdom, and Australia. Vaccine. (2022) 40:2498–505. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.06.048

177. Tsai, R, Hervey, J, Hoffman, K, Wood, J, Johnson, J, Deighton, D, et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and acceptance among individuals with cancer, autoimmune diseases, or other serious comorbid conditions: cross-sectional, internet-based survey. JMIR Public Health Surveill. (2022) 8:e29872. doi: 10.2196/29872

178. Turhan, Z, Dilcen, HY, and Dolu, İ. The mediating role of health literacy on the relationship between health care system distrust and vaccine hesitancy during COVID-19 pandemic. Curr Psychol. (2022) 41:8147–56. doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-02105-8

179. Uhr, L, and Mateen, FJ. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in multiple sclerosis: a cross-sectional survey. Mult Scler J. (2022) 28:1072–80. doi: 10.1177/13524585211030647

180. Umakanthan, S, Patil, S, Subramaniam, N, and Sharma, R. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and resistance in India explored through a population-based longitudinal survey. Vaccine. (2021) 9:1064. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9101064

181. Uvais, N. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among patients with psychiatric disorders. Primary Care Compan CNS Dis. (2021) 23:37927. doi: 10.4088/PCC.21br03028

182. Uzochukwu, IC, Eleje, GU, Nwankwo, CH, Chukwuma, GO, Uzuke, CA, Uzochukwu, CE, et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among staff and students in a Nigerian tertiary educational institution. Therap Adv Infect Dis. (2021) 8:204993612110549. doi: 10.1177/20499361211054923

183. Vallée, A, Fourn, E, Majerholc, C, Touche, P, and Zucman, D. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among French people living with HIV. Vaccine. (2021) 9:302. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9040302

184. Vergiev, S, and Niyazi, D. Vaccine hesitancy during the COVID-19 vaccination campaign: a cross-sectional survey among Bulgarian university students. Acta Microbiol Bulg. (2021) 37:122–5.

185. Walker, KK, Head, KJ, Owens, H, and Zimet, GD. A qualitative study exploring the relationship between mothers’ vaccine hesitancy and health beliefs with COVID-19 vaccination intention and prevention during the early pandemic months. Hum Vaccin Immunother. (2021) 17:3355–64. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1942713

186. Wang, C, Han, B, Zhao, T, Liu, H, Liu, B, Chen, L, et al. Vaccination willingness, vaccine hesitancy, and estimated coverage at the first round of COVID-19 vaccination in China: a national cross-sectional study. Vaccine. (2021) 39:2833–42. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.04.020

187. Wang, K, Wong, EL-Y, Ho, K-F, Cheung, AW-L, Yau, PS-Y, Dong, D, et al. Change of willingness to accept COVID-19 vaccine and reasons of vaccine hesitancy of working people at different waves of local epidemic in Hong Kong, China: repeated cross-sectional surveys. Vaccine. (2021) 9:62. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9010062

188. Wang, Q, Xiu, S, Zhao, S, Wang, J, Han, Y, Dong, S, et al. Vaccine hesitancy: COVID-19 and influenza vaccine willingness among parents in Wuxi, China—a cross-sectional study. Vaccine. (2021) 9:342. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9040342

189. Waters, AR, Kepka, D, Ramsay, JM, Mann, K, Vaca Lopez, PL, Anderson, JS, et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. JNCI Cancer Spectr. (2021) 5:pkab049. doi: 10.1093/jncics/pkab049

190. West, H, Lawton, A, Hossain, S, Mustafa, AG, Razzaque, A, and Kuhn, R. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among temporary foreign workers from Bangladesh. Health Syst Reform. (2021) 7:e1991550. doi: 10.1080/23288604.2021.1991550

191. Willis, DE, Andersen, JA, Bryant-Moore, K, Selig, JP, Long, CR, Felix, HC, et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: race/ethnicity, trust, and fear. Clin Transl Sci. (2021) 14:2200–7. doi: 10.1111/cts.13077

192. Xu, Y, Cao, Y, Ma, Y, Zhao, Y, Jiang, H, Lu, J, et al. COVID-19 vaccination attitudes with neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders: vaccine hesitancy and coping style. Front Neurol. (2021) 12:717111. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.717111

193. Xu, Y, Xu, D, Luo, L, Ma, F, Wang, P, Li, H, et al. A cross-sectional survey on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among parents from Shandong vs. Zhejiang. Front Public Health. (2021) 9:779720. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.779720

194. Yang, Y, Dobalian, A, and Ward, KD. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and its determinants among adults with a history of tobacco or marijuana use. J Community Health. (2021) 46:1090–8. doi: 10.1007/s10900-021-00993-2

195. Yilmaz, S, Çolak, FÜ, Yilmaz, E, Ak, R, Hökenek, NM, and Altıntaş, MM. Vaccine hesitancy of health-care workers: another challenge in the fight against COVID-19 in Istanbul. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. (2022) 16:1134–40. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2021.257

196. Zhang, Z, Feng, G, Xu, J, Zhang, Y, Li, J, Huang, J, et al. The impact of public health events on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy on Chinese social media: national infoveillance study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. (2021) 7:e32936. doi: 10.2196/32936

197. Zhuang, W, Zhang, J, Wei, P, Lan, Z, Chen, R, Zeng, C, et al. Misconception contributed to COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in patients with lung cancer or ground-glass opacity: a cross-sectional study of 324 Chinese patients. Hum Vaccin Immunother. (2021) 17:5016–23. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1992212

198. Ackah, BB, Woo, M, Stallwood, L, Fazal, ZA, Okpani, A, Ukah, UV, et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Africa: a scoping review. Global Health Res Policy. (2022) 7:1–20. doi: 10.1186/s41256-022-00255-1

199. Sallam, MJV. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy worldwide: a concise systematic review of vaccine acceptance rates. Vaccines (Basel). (2021) 9:160. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9020160

200. Aw, J, Seng, JJB, Seah, SSY, and Low, LL. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy—a scoping review of literature in high-income countries. Vaccine. (2021) 9:900. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9080900

201. Biswas, MR, Alzubaidi, MS, Shah, U, Abd-Alrazaq, AA, and Shah, Z. A scoping review to find out worldwide COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and its underlying determinants. Vaccine. (2021) 9:1243. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9111243

202. Cooper, S, van Rooyen, H, and Wiysonge, CS. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in South Africa: how can we maximize uptake of COVID-19 vaccines? Expert Rev Vaccines. (2021) 20:921–33. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2021.1949291

203. Troiano, G, and Nardi, A. Vaccine hesitancy in the era of COVID-19. Public Health. (2021) 194:245–51. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2021.02.025

204. Majid, U, Ahmad, M, Zain, S, Akande, A, and Ikhlaq, F. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and acceptance: a comprehensive scoping review of global literature. Health Promot Int. (2022) 37:daac078. doi: 10.1093/heapro/daac078

205. Xiao, X, and Wong, RM. Vaccine hesitancy and perceived behavioral control: a meta-analysis. Vaccine. (2020) 38:5131–8. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.04.076

206. Rutten, LJF, Zhu, X, Leppin, AL, Ridgeway, JL, Swift, MD, Griffin, JM, et al. Evidence-based strategies for clinical organizations to address COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy In: Mayo Clinic proceedings. (Netherlands: Elsevier) (2021)

207. Kassianos, G, Puig-Barberà, J, Dinse, H, Teufel, M, Türeci, Ö, and Pather, S. Addressing COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Drugs Context. (2022) 11:1–19. doi: 10.7573/dic.2021-12-3

208. Payberah, E, Payberah, D, Sarangi, A, and Gude, J. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in patients with mental illness: strategies to overcome barriers—a review. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. (2022) 97:1–6. doi: 10.1186/s42506-022-00102-8

Keywords: COVID-19, vaccine hesitancy, refusal rate, strategy, scoping review

Citation: Bahreini R, Sardareh M and Arab-Zozani M (2024) A scoping review of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: refusal rate, associated factors, and strategies to reduce. Front. Public Health. 12:1382849. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1382849

Edited by:

Mahmaod I. Alrawad, Al-Hussein Bin Talal University, JordanReviewed by:

Shisan (Bob) Bao, The University of Sydney, AustraliaAna Afonso, NOVA University of Lisbon, Portugal

Copyright © 2024 Bahreini, Sardareh and Arab-Zozani. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Morteza Arab-Zozani, YXJhYi5odGFAZ21haWwuY29t

†ORCID: Morteza Arab-Zozani, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7223-6707

Rona Bahreini

Rona Bahreini Mehran Sardareh

Mehran Sardareh Morteza Arab-Zozani

Morteza Arab-Zozani