94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Public Health, 30 May 2024

Sec. Injury Prevention and Control

Volume 12 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1381754

This article is part of the Research TopicGender Differences in Falls and Mobility Patterns of Older AdultsView all 7 articles

Pinli Lin1†

Pinli Lin1† Guang Lin2†

Guang Lin2† Biyu Wan3

Biyu Wan3 Jintao Zhong1

Jintao Zhong1 Mengya Wang3

Mengya Wang3 Fang Tang4

Fang Tang4 Lingzhen Wang5

Lingzhen Wang5 Yuling Ye5

Yuling Ye5 Lu Peng5

Lu Peng5 Xusheng Liu5*

Xusheng Liu5* Lili Deng6*

Lili Deng6*Background: The population with chronic kidney disease (CKD) has significantly heightened risk of fall accidents. The aim of this study was to develop a validated risk prediction model for fall accidents among CKD in the community.

Methods: Participants with CKD from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) were included. The study cohort underwent a random split into a training set and a validation set at a ratio of 70 to 30%. Logistic regression and LASSO regression analyses were applied to screen variables for optimal predictors in the model. A predictive model was then constructed and visually represented in a nomogram. Subsequently, the predictive performance was assessed through ROC curves, calibration curves, and decision curve analysis.

Result: A total of 911 participants were included, and the prevalence of fall accidents was 30.0% (242/911). Fall down experience, BMI, mobility, dominant handgrip, and depression were chosen as predictor factors to formulate the predictive model, visually represented in a nomogram. The AUC value of the predictive model was 0.724 (95% CI 0.679–0.769). Calibration curves and DCA indicated that the model exhibited good predictive performance.

Conclusion: In this study, we constructed a predictive model to assess the risk of falls among individuals with CKD in the community, demonstrating good predictive capability.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) has an estimated global prevalence of approximately 9.1% among adults (1). The prevalence of CKD rises linearly with age, with individuals over 60 accounting for more than 60% of all cases (2). CKD often results in systemic complications, causing decreased physical strength, cognitive decline, osteoporosis, muscle atrophy, and other issues that elevate the risk of falls (3–5). Studies have demonstrated that individuals with CKD face an elevated risk of falling compared to those without the condition, indicating an elevated risk of falls among individuals with chronic kidney disease (6–9).

Falls resulting in injuries may lead to fatalities and long-term disabilities, adversely affecting the quality of life for those impacted (10). Epidemiological studies confirm that falls are universally recognized as the second most common cause of unintentional injury-related fatalities (11). Individuals with CKD often experience conditions such as renal osteodystrophy, leading to compromised bone health. This renders CKD patients more susceptible to fractures in the event of a fall compared to the general population (4, 12, 13). Furthermore, even non-injurious falls may instill fear of falling in patients, increasing the risk of recurrent falls (14, 15). These underscore the critical importance of early monitoring and fall prevention in individuals with CKD.

The treatment of CKD is a long-term process, and patients typically reside within the community, making it challenging for healthcare professionals to monitor and manage their conditions in real-time. Therefore, the development of a reliable model within the community could identify CKD individuals at a heightened risk of falls, enabling personalized management strategies.

The occurrence of falls in individuals with CKD is a result of the synergistic impact of various factors. Previous studies have indicated that weaknesses, muscle wasting, depression, cognitive decline, electrolyte imbalances, anemia, and other symptoms commonly associated with CKD are related to the occurrence of falls (5, 16–18). In this study, the objective is to develop and validate models for predicting the occurrence of falls among individuals with CKD in the community. The aim is to facilitate the early identification of fall risks and enhance alertness to their potential occurrence.

The data for this study was sourced from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) (19). which is a comprehensive nationwide survey conducted by the National Institute of Development of Peking University. CHARLS is designed to collect demographic and health-related data from individuals aged 45 and above across 28 provinces in China. This study was carried out in compliance with ethical standards and received approval from the Biomedical Ethics Review Committee of Peking University. All participants provided written informed consent, and the study was assigned the ethical approval number IRB00001052-11015.

For the present analysis, we included participants who self-reported chronic kidney disease in 2015. We excluded individuals who lacked information on falls during the 2017–2018 survey. Additionally, participants with missing blood data and answered by others were also excluded. Final study cohort comprising 911 participants (Figure 1).

Participants reported these incidents through a specific question in the 2017–2018 survey: “Have you experienced any falls since your last visit?” Participants provided responses, indicating either “yes” or “no.”

The variables included in the analysis encompassed a wide range of factors. These factors covered demographic information such as age, gender, marital status, disability and body mass index (BMI). Behavioral data was considered, including alcohol consumption status, smoking status, mobility, toilet seat usage, fall down experiences, dominant handgrip strength, pain status, night sleep duration, as well as activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL).

Health status was thoroughly assessed, taking into account blood pressure, CESD-10 score, cognitive score, and various comorbidities such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, cancer, heart disease, stroke, depression, memory-related diseases, arthritis, asthma, and glaucoma. In addition, several blood indicators were included, such as white blood cell count (WBC), hemoglobin, platelet count, triglycerides (TG), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), glucose, uric acid (UA), cystatin C, C-reactive protein, and hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c). The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was also considered in the analysis.

Disability encompasses physical disabilities, brain damage/mental retardation, or vision problems. BMI was calculated using the standard formula. Participants with a BMI > 45 were considered outliers and were excluded from further analysis. Mobility included walking sticks, travel devices, manual wheelchairs, and electric wheelchairs. The dominant handgrip strength was measured using a hydraulic handgrip dynamometer, specifically the Yuejian TM WL-1000 dynamometer. To determine the dominant hand, participants were asked the question, “Which is your dominant hand?” The handgrip strength was then recorded by averaging the results of two separate measurements. Participants with handgrip strength 0 kg were identified as outliers and excluded from further analysis. The cognitive score in CHARLS was determined through telephone interviews assessing cognitive status (TICS-10), a visuospatial ability test, and an episodic memory capacity test. A lower score indicates a higher risk of cognitive impairment. The CESD-10 score was utilized to evaluate depression. The total cumulative score on this scale is 30, with a score of 10 or higher indicating a high risk of depression. eGFR calculated was based on the eGFR. MDRD. Chinese (20).

All statistical analyses were conducted using the R statistical software package, version 4.3.1 (http://www.R-project.org, The R Foundation), and Free Statistics software, version 1.9.1. Continuous variables, including normally distributed data presented as means ± standard deviations and skewed data expressed as medians with interquartile ranges, were analyzed in this study. Categorical variables are reported as percentages. Baseline characteristics were compared using the t-test for normally distributed continuous variables and the rank sum test for skewed continuous variables. The chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was employed for the analysis of categorical variables.

Multiple interpolation was used to handle missing data. Data were randomly divided into training (n = 638) and validation (n = 273) sets, according to a ratio of 7:3. Training set data were analyzed by least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression and logistic regression analysis to select predictors of fall accidents in people with CKD.

In this study, the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC) was used to determine the discrimination ability of the model. Calibration curves were used to determine the degree of agreement between predicted probabilities and observed outcomes. Decision curve analysis (DCA) was used to assess clinical validity. A nomogram was used to illustrate the risk of fall in individuals with CKD. Internal consistency of the discrimination and calibration performance measures was evaluated by 10-fold cross-validation. All statistical tests were two-tailed, and a significance level of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Our study comprised 911 participants with CKD. The mean age was 61.2 ± 9.0 years, 464 (50.9%) were male. The incidence of fall accidents among participants with CKD was 30.0%. The baseline characteristics were summarized in Supplementary Table S1. Maximum missing values for all variables extracted did not exceed 6.5%. To address this, we applied data multiple interpolation techniques. After divide into training (n = 638) and validation (n = 273) sets, we obtained baseline characteristics of participants were showed in Table 1.

The prevalence of fall accidents was 26.6% (242/911). Univariate logistic regression analysis indicated that several factors, including age, marital status, mobility, fall down experience, pain status, nighttime sleep duration, ADL, IADL, CESD-10 score, cognitive score, dominant handgrip, and arthritis, differed significantly (p < 0.01) between participants with and without fall accidents. Further multivariable analysis demonstrated that fall down experience, CESD-10 score, dominant handgrip, and mobility were independent risk factors for fall accidents among CKD participants (Table 2).

To eliminate potential confounders and simplify the model, we employed LASSO regression analysis to identify the best predictors of the model. The variables considered in this model included fall down experience, ADL, IADL, mobility, dominant grip, marital status, and CESD-10 score as predictive factors (Supplementary Figure S1). This predictive model is intended for application in community populations, and for enhanced user-friendliness, we selected fall down experience, BMI, mobility, dominant handgrip, and depression as predictors in the model development process. Finally, the predictive model was developed and presented using a nomogram (Figure 2).

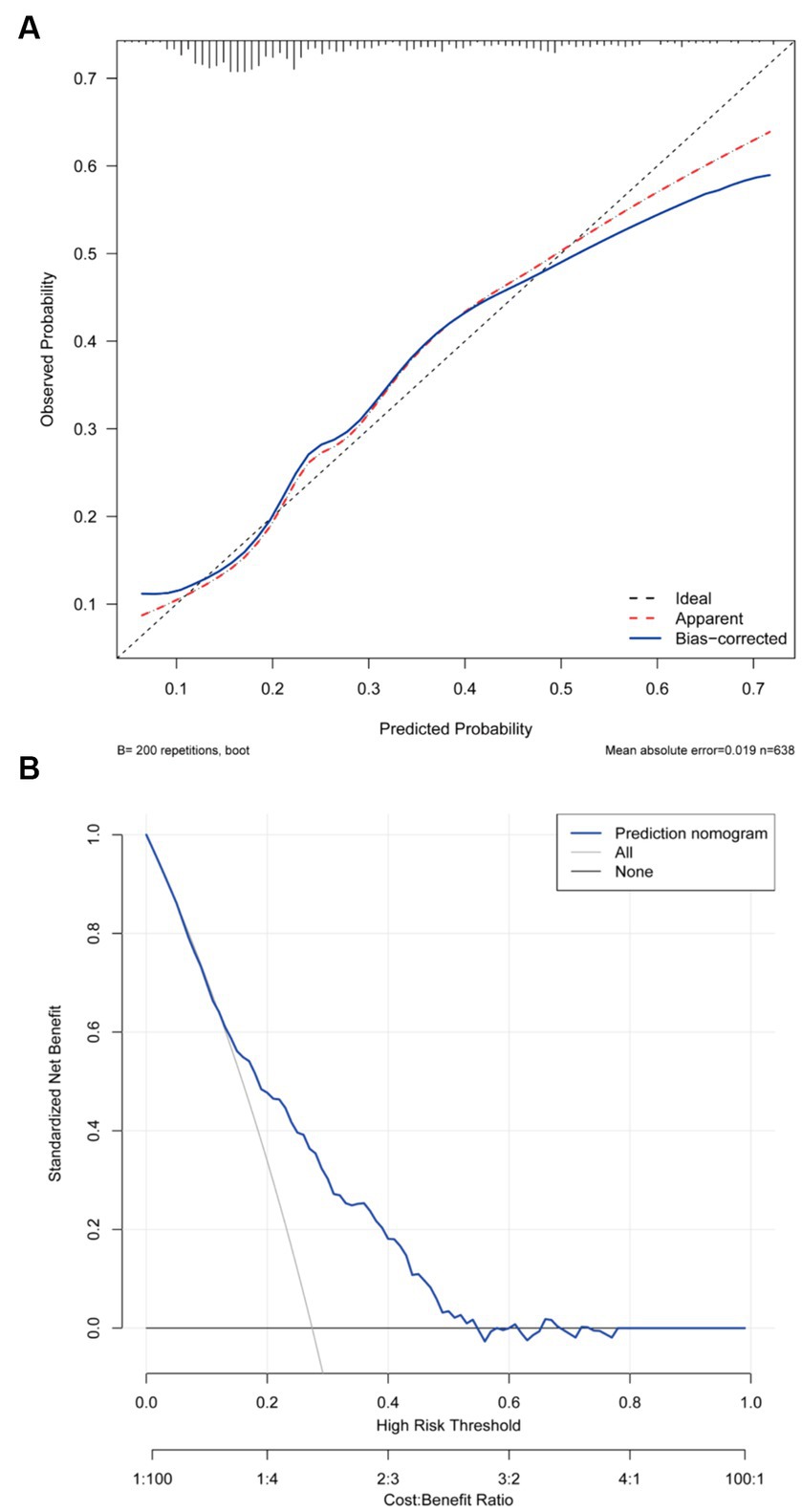

As shown in Figure 3, the predictive model achieved an AUC value of 0.724 (95% CI = 0.679–0.769), and the calibration curve illustrated that the model exhibited a good fit (χ2 = 5.293, df = 7, p = 0.726). The clinical validity of the model was evaluated using the DCA method, and the results showed that the training set exceeded the extreme cases, indicating that the nomogram model provided superior net benefit and predictive accuracy (Figure 4).

Figure 4. (A) Calibration plot for the training dataset. (B) Decision curve plot for the training dataset.

Internal validation using a validation set demonstrated that the discrimination AUC, calibration χ2, and calibration slope means were similar to those obtained from the models for the entire population. This indicates good internal consistency for our equations. The DCA curve demonstrated the model’s clinical validity (Supplementary Figures S2–S4). Furthermore, we conducted an internal validation using a 10-fold cross-validation, and the results remained stable (the mean AUC = 0.719).

In this study, fall down experience, BMI, mobility, dominant handgrip, and depression were selected as predictor factors to develop the predictive model for fall accidents among individuals with CKD in the community. The model demonstrated excellent performance in predicting fall risk, exhibiting robust internal consistency and external validation. To our knowledge, no other predictive model for fall accidents has been developed and validated among individuals with CKD in the community.

The occurrence of falls in patients with CKD is a consequence of the combined effects of multiple factors. This study revealed that a history of falling, BMI, mobility, dominant handgrip, and depression were predictors of fall accidents in individuals with CKD.

Having experienced a fall previously significantly increases the risk of subsequent fall accidents. This finding aligns with conclusions drawn from several studies involving the elders (21, 22). Currently widely applied fall risk prediction models for hospitalized older adult individuals similarly underscore the potential risk associated with a history of falling in predicting fall accidents. Studies on fall incidents among patients with liver cirrhosis and diabetes similarly utilize fall history as a predictive factor, highlighting the independent correlation between fall history and the occurrence of falls (23, 24). This correlation remains significant among individuals with CKD. It can be attributed to the fact that those with CKD, who have a history of falls, may be more prone to developing a fear of falling, which leads to reduced physical activity. The reduced physical activity contributes to diminished muscle function, thereby increasing the risk of falls (14). The use of mobility aids follows a similar pattern; their use is often considered in fall risk assessments, and it has been observed that the use of mobility aids decreases activity levels in individuals with CKD, leading to a decline in muscle function and an increased risk of falls (21).

BMI and dominant handgrip strength are also considered in the predictive model. This is because in individuals with CKD, renal function decline leads to the excretion of albumin in urine, often accompanied by symptoms such as hypoalbuminemia and malnutrition. These conditions typically result in decreased muscle mass, making it challenging for the body to support its weight, thus increasing the risk of falls. BMI is the simplest and most readily measurable indicator for assessing nutritional status, while handgrip strength is the simplest and most readily measurable indicator for assessing sarcopenia (16, 25). Furthermore, several studies have also demonstrated the correlation between handgrip strength and falls, providing additional support to the conclusions (26–29).

It is noteworthy that cognitive function is often considered a predictive factor for fall risk (17, 30). However, in this study, the decline in cognitive function among individuals with CKD has not been included as a predictive factor in the model. However, in this study, after adjusting for multiple factors, cognitive function did not exhibit a significant association with falls. This may be due to the widespread occurrence of cognitive decline among individuals with CKD.

However, there are several limitations should be considered. First, the incidence of falls in our study may have been underestimated. Fall accidents were defined based on self-reported incidents of falling within the past 2 years, introducing the potential for memory bias. Fall incidents without injury might be overlooked or forgotten in such self-reports. Second, the nomogram was created using data from Chinese adults with CKD aged over 45 years. To validate the model’s suitability for other groups, including younger individuals or those from different ethnic backgrounds, additional data from external cohorts are required. Third, the nomogram did not encompass several potential predictors, including balance function and walking speed and so on, which could exert an influence on the occurrence of falls. However, our model is designed to be used in the community, focusing on markers that are both easily measurable and efficient for widespread application. The chosen predictors in our model, including fall down experience, BMI, mobility, dominant handgrip, and depression, align with the principle that applicable prediction models should leverage easily measurable characteristics. Fourth, this study outcomes are based on self-reported falls within 2 years, covering both injurious and non-injurious falls, but do not include fall frequency. Our main focus is on falls as isolated incidents. Although we acknowledge that non-injurious falls are also worthy of attention, considering the cost–benefit ratio, further research is needed to comprehensively evaluate a broader range of outcomes.

In this study, we developed and validated a predictive model for fall accidents among individuals with CKD in the community, presenting it in the form of a nomogram. Variables such as fall down experience, BMI, mobility, dominant handgrip, and depression were identified and included in the model. Internally validated, the model proved to be a useful tool for assessing the risk of fall incidents. The developed predictive model holds potential significance in screening CKD patients at a high risk of experiencing falls.

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found at: http://charls.pku.edu.cn/index.htm.

The studies involving humans were approved by Biomedical Ethics Review Committee of Peking University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

PL: Methodology, Writing – original draft. GL: Data curation, Writing – original draft. BW: Writing – original draft, Data curation. JZ: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. MW: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis. FT: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. LW: Data curation, Writing – original draft. YY: Data curation, Writing – original draft. LP: Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft. XL: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. LD: Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by Sanming Project of Medicine in Shenzhen (No. SZZYSM202206014) and Special Research Project on Traditional Chinese Medicine Science and Technology at Guangdong Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine (No. YN2022HL21). This work was also supported by the Major Innovation Technology Construction Project in Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine Clinical Collaboration in Guangzhou Area (to XL).

We would like to express our gratitude to the CHARLS team for their diligent efforts and selfless sharing of survey data, as well as to Qilin Yang (The Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou, China) for their valuable assistance in this revision.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1381754/full#supplementary-material

1. Cockwell, P, and Fisher, L-A. The global burden of chronic kidney disease. Lancet. (2020) 395:662–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32977-0

2. Hill, NR, Fatoba, ST, Oke, JL, Hirst, JA, O’Callaghan, CA, Lasserson, DS, et al. Global prevalence of chronic kidney disease – a systematic review and Meta-analysis. PLoS One. (2016) 11:e0158765. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158765

3. Bohannon, RW, Hull, D, and Palmeri, D. Muscle strength impairments and gait performance deficits in kidney transplantation candidates. Am J Kidney Dis. (1994) 24:480–5. doi: 10.1016/S0272-6386(12)80905-X

4. Huang, J-F, Zheng, X-Q, Sun, X-L, Zhou, X, Liu, J, Li, YM, et al. Association between bone mineral density and severity of chronic kidney disease. Int J Endocrinol. (2020) 2020:1–11. doi: 10.1155/2020/8852690

5. Webster, AC, Nagler, EV, Morton, RL, and Masson, P. Chronic kidney disease. Lancet. (2017) 389:1238–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32064-5

6. Kistler, BM, Khubchandani, J, Wiblishauser, M, Wilund, KR, and Sosnoff, JJ. Epidemiology of falls and fall-related injuries among middle-aged adults with kidney disease. Int Urol Nephrol. (2019) 51:1613–21. doi: 10.1007/s11255-019-02148-8

7. Kistler, BM, Khubchandani, J, Jakubowicz, G, Wilund, K, and Sosnoff, J. Falls and fall-related injuries among US adults aged 65 or older with chronic kidney disease. Prev Chronic Dis. (2018) 15:E82. doi: 10.5888/pcd15.170518

8. Lin, P, Wan, B, Zhong, J, Wang, M, Tang, F, Wang, L, et al. Risk of fall in patients with chronic kidney disease: results from the China health and retirement longitudinal study (CHARLS). BMC Public Health. (2024) 24:499. doi: 10.1186/s12889-024-17982-4

9. Liu, H, Hou, Y, Li, H, and Lin, J. Influencing factors of weak grip strength and fall: a study based on the China health and retirement longitudinal study (CHARLS). BMC Public Health. (2022) 22:2337. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-14753-x

10. Wang, J, Chen, Z, and Song, Y. Falls in aged people of the Chinese mainland: epidemiology, risk factors and clinical strategies. Ageing Res Rev. (2010) 9:S13–7. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2010.07.002

11. Ye, P, Er, Y, Wang, H, Fang, L, Li, B, Ivers, R, et al. Burden of falls among people aged 60 years and older in mainland China, 1990–2019: findings from the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Public Health. (2021) 6:e907–18. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00231-0

12. Cannata-Andía, JB, Martín-Carro, B, Martín-Vírgala, J, Rodríguez-Carrio, J, Bande-Fernández, JJ, Alonso-Montes, C, et al. Chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disorders: pathogenesis and management. Calcif Tissue Int. (2021) 108:410–22. doi: 10.1007/s00223-020-00777-1

13. Kutner, NG, and Bowling, CB. Targeting Fall Risk in CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. (2019) 14:965–6. doi: 10.2215/CJN.06040519

14. Patil, R, Uusi-Rasi, K, Kannus, P, Karinkanta, S, and Sievänen, H. Concern about falling in older women with a history of falls: associations with health, functional ability, physical activity and quality of life. Gerontology. (2014) 60:22–30. doi: 10.1159/000354335

15. Bahat Öztürk, G, Kılıç, C, Bozkurt, ME, and Karan, MA. Prevalence and Associates of Fear of falling among community-dwelling older adults. J Nutr Health Aging. (2021) 25:433–9. doi: 10.1007/s12603-020-1535-9

16. Moorthi, RN, and Avin, KG. Clinical relevance of sarcopenia in chronic kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. (2017) 26:219–28. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000318

17. Zhou, R, Li, J, and Chen, M. The association between cognitive impairment and subsequent falls among older adults: evidence from the China health and retirement longitudinal study. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:900315. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.900315

18. Gambaro, E, Gramaglia, C, Azzolina, D, Campani, D, Molin, AD, and Zeppegno, P. The complex associations between late life depression, fear of falling and risk of falls. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. (2022) 73:101532. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2021.101532

19. Zhao, Y, Hu, Y, Smith, JP, Strauss, J, Yang, G, and Negri, E. Cohort Profile: The China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). International Journal of Epidemiology. (2014) 43:61–6. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys203

20. Ma, Y-C, Zuo, L, Chen, J-H, Luo, Q, Yu, X-Q, Li, Y, et al. Modified glomerular filtration rate estimating equation for Chinese patients with chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. (2006) 17:2937–44. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006040368

21. Deandrea, S, Lucenteforte, E, Bravi, F, Foschi, R, La Vecchia, C, and Negri, E. Risk factors for falls in community-dwelling older people. Epidemiology. (2010) 21:658–68. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181e89905

22. Xu, Q, Ou, X, and Li, J. The risk of falls among the aging population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:902599. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.902599

23. Tapper, EB, Nikirk, S, Parikh, ND, and Zhao, L. Falls are common, morbid, and predictable in patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol. (2021) 75:582–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.04.012

24. Cheng, Z, Li, X, Xu, H, Bao, D, Mu, C, and Xing, Q. Incidence of accidental falls and development of a fall risk prediction model among elderly patients with diabetes mellitus: a prospective cohort study. J Clin Nurs. (2023) 32:1398–409. doi: 10.1111/jocn.16371

25. Porto, JM, Nakaishi, APM, Cangussu-Oliveira, LM, Freire Júnior, RC, Spilla, SB, and DCC, DA. Relationship between grip strength and global muscle strength in community-dwelling older people. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. (2019) 82:273–8. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2019.03.005

26. Yang, N-P, Hsu, N-W, Lin, C-H, Chen, H-C, Tsao, H-M, Lo, S-S, et al. Relationship between muscle strength and fall episodes among the elderly: the Yilan study, Taiwan. BMC Geriatr. (2018) 18:90. doi: 10.1186/s12877-018-0779-2

27. Kwon, J-W, Lee, BH, Lee, S-B, Sung, S, Lee, C-U, Yang, J-H, et al. Hand grip strength can predict clinical outcomes and risk of falls after decompression and instrumented posterolateral fusion for lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine J. (2020) 20:1960–7. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2020.06.022

28. Van Ancum, JM, Pijnappels, M, Jonkman, NH, Scheerman, K, Verlaan, S, Meskers, CGM, et al. Muscle mass and muscle strength are associated with pre-and post-hospitalization falls in older male inpatients: a longitudinal cohort study. BMC Geriatr. (2018) 18:116. doi: 10.1186/s12877-018-0812-5

29. Ikegami, S, Takahashi, J, Uehara, M, Tokida, R, Nishimura, H, Sakai, A, et al. Physical performance reflects cognitive function, fall risk, and quality of life in community-dwelling older people. Sci Rep. (2019) 9:12242. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-48793-y

Keywords: falls, chronic kidney disease, CHARLS, predictive model, nomogram

Citation: Lin P, Lin G, Wan B, Zhong J, Wang M, Tang F, Wang L, Ye Y, Peng L, Liu X and Deng L (2024) Development and validation of prediction model for fall accidents among chronic kidney disease in the community. Front. Public Health. 12:1381754. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1381754

Received: 04 February 2024; Accepted: 07 May 2024;

Published: 30 May 2024.

Edited by:

Yijian Yang, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, ChinaReviewed by:

Lambert Zixin Li, Stanford University, United StatesCopyright © 2024 Lin, Lin, Wan, Zhong, Wang, Tang, Wang, Ye, Peng, Liu and Deng. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xusheng Liu, bGl1eHVzaGVuZ0BnenVjbS5lZHUuY24=; Lili Deng, ZGVuZ2xpbGlAZ3p1Y20uZWR1LmNu

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.