- One Health Research Group, Faculty of Health Sciences, Universidad de las Américas, Quito, Ecuador

Cervical cancer, primarily caused by human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, poses a significant global health challenge. Due to higher levels of poverty and health inequities, Indigenous women worldwide are more vulnerable to cervical cancer than their non-Indigenous counterparts. However, despite constituting nearly 10% of the population in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), the true extent of the burden of cervical cancer among Indigenous people in this region remains largely unknown. This article reviews the available information on cervical cancer incidence and mortality, as well as HPV infection prevalence, among Indigenous women in LAC. The limited existing data suggest that Indigenous women in this region face a heightened risk of cervical cancer incidence and mortality compared to non-Indigenous women. Nevertheless, a substantial knowledge gap persists that must be addressed to comprehensively assess the burden of cervical cancer among Indigenous populations, especially through enhancing cancer surveillance across LAC countries. Numerous structural, social and cultural barriers hindering Indigenous women’s access to HPV vaccination and cervical cancer screening worldwide have been identified and are reviewed in this article. The discussion highlights the critical role of culturally sensitive education, community engagement, and empowerment strategies in overcoming those barriers. Drawing insights from the success of targeted strategies in certain high-income countries, the present article advocates for research, policies and healthcare interventions tailored to the unique context of LAC countries.

1 Introduction

Cervical cancer is caused by human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, the most common sexually transmitted viral infection worldwide (1, 2). It has been estimated that, in the United States, more than 80% of sexually active women and men will acquire at least one HPV infection by the age of 45 years (3). In women, 90% of incident genital HPV infections clear within 2 years without any clinical impact (4). However, when persistence occurs, HPV becomes a risk factor for malignant transformation. Out of the more than 200 HPV types identified, 12 high-risk HPVs are responsible for virtually all cases of cervical cancers (5, 6).

Cervical cancer is one of the few cancers preventable through both vaccination and screening. Several prophylactic HPV vaccines are available in most countries and the World Health Organization (WHO) currently recommends one or two-dose vaccination of girls aged 9 to 14 years (7). As various high-risk HPV types are not covered by the vaccines, high-quality screening programs are also paramount to prevent cervical cancer. Screening can detect premalignant and early malignant lesions that can be treated with a very good prognosis (8). Three different methods can be used to identify women who have, or are at risk of, cervical precancerous lesions and early invasive cancer: (1) detection of genital high-risk HPV infection through a DNA-based test on cervical or vaginal samples; (2) microscopic examination of cervical exfoliated cells, known as the Papanicolaou (Pap) cytology test; or (3) visual inspection of the cervix with acetic acid, in low-resource settings (7). In high-income countries, the implementation of screening and treatment programs since the 1950s followed by the introduction of HPV vaccination since 2006 has led to a dramatic reduction in both the prevalence of HPV vaccine-types and closely related HPV types and the incidence and mortality of cervical cancer (9–14). Before the effectiveness of these prevention measures, the WHO launched in 2020 a strategy for the global elimination of cervical cancer, with three main objectives to be reached by 2030: 90% vaccination rates, 70% screening rates and treatment for 90% of the invasive cancers for women in all countries (15).

Unfortunately, challenges persist in low- and middle-income countries in implementing cervical cancer screening programs and ensuring access to HPV vaccines. As a result, these countries currently bear the largest burden of this preventable disease, with cervical cancer incidence and mortality worldwide strongly correlated with country income level, human development index and living standards (16, 17). At present, cervical cancer ranks fourth in cancer incidence and mortality among women globally (18). In 2020 alone, an estimated 604,000 new cases and 342,000 deaths were reported, with over 80% of these cases occurring in low- and-middle-income countries (18, 19). In Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), most of the countries have implemented cervical screening and HPV vaccination programs, and trends in cervical cancer incidence and mortality have decreased over the past 20 years (20, 21). However, several barriers to screening access and vaccination uptake persist (22, 23), and the age-standardized incidence and mortality rates in LAC in 2018 were 14.6 and 7.1 per 100,000, respectively, ranking second after the African region and slightly higher than the global rates (13.1 and 6.9, respectively) (20). In 2020, cervical cancer remained the leading cause of cancer death in women in Belize, Honduras, Nicaragua, Bolivia and Paraguay (18).

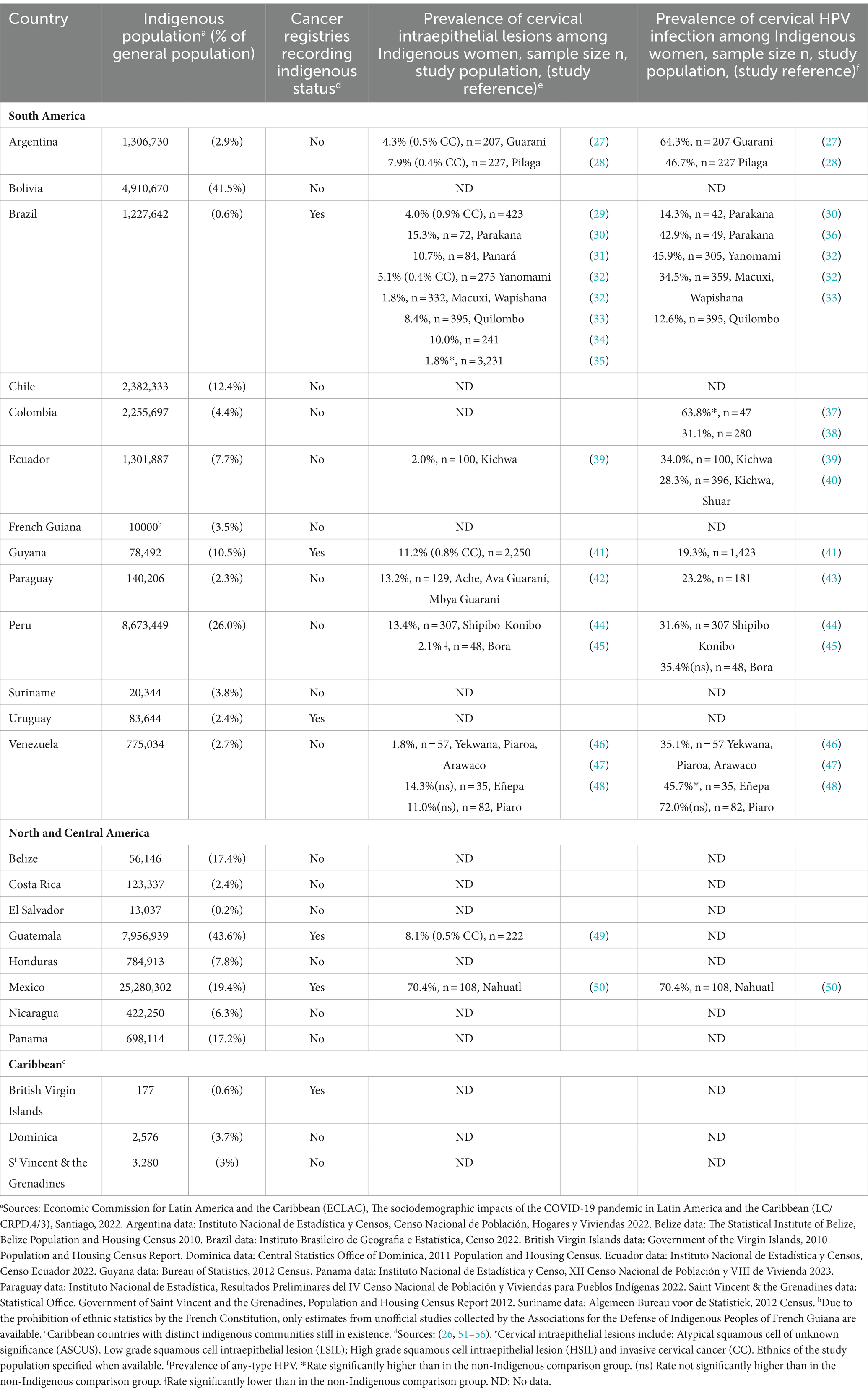

An estimated 58 million Indigenous people lived in Latin America in 2018, accounting for 10% of the total population of the subregion (24). While no formal definition has been adopted in international law, a contemporary and inclusive understanding of “Indigenous peoples” has been developed and includes those who self-identify and are identified as indigenous, exhibit historical continuity with precolonial societies, possess distinct social, economic, or political systems, maintain unique languages, cultures, and beliefs, and constitute nondominant groups of society (25, 26). In most LAC countries, the determination of indigenous status in population censuses relies on self-identification by individuals (26). The distribution of Indigenous people varies widely across LAC, both in terms of absolute numbers and relative proportions (Table 1). Guatemala, Bolivia and Peru have the highest proportions of indigenous population, with 43.6, 41.5 and 26.0%, respectively. Meanwhile, Mexico is the country with the largest number of indigenous individuals, totaling around 25 million.

Table 1. Indigenous population, recording of indigenous status by cancer registries, and prevalence of cervical intraepithelial lesions and HPV infection among Indigenous women in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Despite the inherent cultural, geographic, and genetic diversity among the more than 800 distinct ethnic groups in LAC (57), Indigenous peoples share a common history of colonization and ongoing dispossession of traditional lands, resources and practices (58). Consequently, Indigenous peoples suffer the greatest structural inequalities in Latin America and are over-represented among the socially disadvantaged in almost every country (59). According to estimations from 2020, 45.5% of Indigenous people in Latin America live in poverty and 7.1% in extremely poverty, more than twice the rates for non-Indigenous people in the region (60). Furthermore, in most LAC countries, indigenous people continue to primarily live in rural areas associated with their ancestral territories, and when they live in cities, it is often in extreme poverty in marginal areas, with trouble accessing basic services and decent jobs (59). One consequence of this marginalization is that Indigenous people in LAC have disproportionally worse health than their nonindigenous counterparts (61). Specifically, Indigenous women are directly impacted by the strong association between poverty and cervical cancer.

The primary objective of this perspective article is to examine the existing data on the burden of cervical cancer among Indigenous women in LAC. Moreover, it aims to identify the barriers potentially hindering their access to HPV vaccination, cervical cancer screening and treatment services. Finally, the article explores proven strategies from high-income countries that have successfully addressed similar challenges, with a view toward their potential applicability within LAC nations.

The articles included in this paper were obtained through a systematic literature search conducted on the PubMed Medline database from its inception to February 2024, using the following terms: (“cervical cancer” OR “papillomavirus”) AND “indigenous.” All abstracts retrieved were reviewed and assessed to identify relevant studies, including peer-reviewed original articles, meta-analyses, reviews, and reports published in English, Spanish or Portuguese. Additional articles were gathered from the references of selected publications. Studies were excluded if they: (1) were unrelated to human papillomavirus infection or cervical cancer; (2) did not clearly define Indigenous people as the study population; (3) were not published in peer-reviewed journals. Furthermore, demographic and epidemiological data specific to each LAC country, including cancer registries and population censuses, were manually searched for on official governmental websites. As a result, findings were categorized and presented through a narrative synthesis in subsequent sections.

2 The burden of cervical cancer among Indigenous women in Latin America and the Caribbean

Because they frequently experience both ethnic and gender discrimination, Indigenous women often face the most profound structural inequalities, especially concerning poverty, education, and healthcare (59). Consequently, they are particularly vulnerable to cervical cancer. Over the last decades, numerous studies have extensively reported and characterized the disproportionately high burden of cervical cancer incidence and mortality among Indigenous women compared to non-Indigenous ones in high-income countries, namely Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the United States (62–68). A higher prevalence of HPV infection has also been observed among Indigenous women compared to the general population in these countries (69–72).

On the contrary, in the LAC region, the actual magnitude of the burden of cervical cancer among Indigenous women remains largely unknown and may be substantially under-estimated due to insufficient data collection. To the best of available information, indigenous status is currently recorded in the population-based cancer registries of only six out of the 24 LAC countries with Indigenous population (Table 1) (26, 51–56). However, none of these six countries publicly provide cancer rates for Indigenous people in their registry reports. Two recent studies have estimated cervical cancer mortality among Indigenous women in Brazil, reporting a mean age-standardized mortality rate of 6.7 per 100,000 between 2000 and 2020, the highest among all ethnic groups in the country and corresponding to a significant 80% increase in cervical cancer death risk compared to white women (73, 74). Regarding cervical cancer incidence, a study conducted on the Indigenous population in the State of Acre, located in the Brazilian Western Amazon, reported that, between 2000 and 2012, cervical cancer was the most frequent neoplasm among indigenous women, and cervical cancer incidence was significantly higher compared to the reference population (Standardized Incidence Ratio: 4.49) (75). Similarly, an analysis of the population-based cancer registry of Guyana from 2000 to 2009 highlighted that cervical cancer was significantly more common among Indigenous Amerindian women compared to other ethnic groups (53). Based on the available information, the assessment of cervical cancer risk among Indigenous women in the rest of LAC relies exclusively on studies investigating the prevalence of cervical HPV infection and cervical intraepithelial lesions within Indigenous populations. Table 1 summarizes the findings of these studies. Reported rates of any-type HPV infection among Indigenous women in LAC are notably high, ranging from 12.6 to 72.0%. Importantly, the majority of studies (15/19) identified higher cervical HPV prevalence rates compared to the meta-analysis estimates for the general populations of Brazil and Latin America, respectively 25.41 and 16.1% (76, 77). Furthermore, a wide range of cervical intraepithelial lesions prevalence rates have been reported among Indigenous women across LAC, varying from 1.8 to 15.3%, except for a study in Mexico which documented an exceptionally high prevalence of 70.4% among Nahuatl women (50). Notably, nine out of the 20 identified studies reported a prevalence of cervical lesions exceeding 10%, while the prevalence of cervical lesions in women worldwide generally remains under 10% (78).

In conclusion, the currently available data suggest that Indigenous women in LAC face a heightened risk of cervical cancer incidence and mortality, mirroring trends observed in Indigenous populations in high-income countries and reflecting the health inequities they experience. However, there remains a significant lack of data on cervical cancer trends among Indigenous women in most LAC countries, including countries like Guatemala, Bolivia, and Mexico, which have some of the highest proportions of Indigenous populations in the region. The wide variations observed in the prevalence of HPV infection and cervical abnormalities may reflect disparities in cervical cancer risk linked to the heterogeneity of Indigenous groups across LAC, including differences in geographical location, degree of isolation, and social and sexual behaviors (35). Consequently, further research is imperative to comprehensively assess the burden of cervical cancer among Indigenous women both regionally and within each LAC country.

3 Barriers to cervical cancer screening and HPV vaccination among Indigenous women

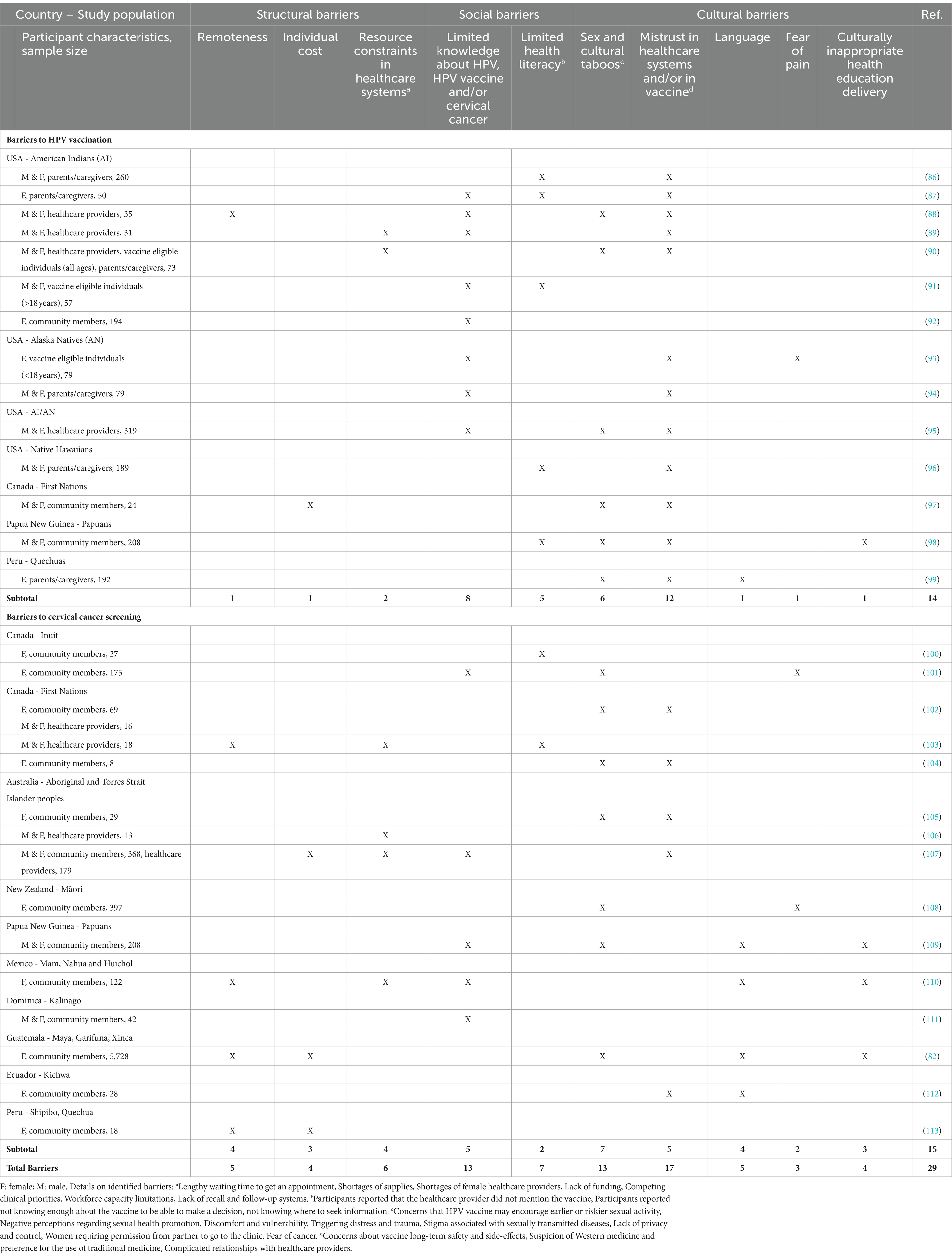

Indigenous women worldwide exhibit a higher prevalence of HPV infection as well as increased cervical cancer incidence and mortality rates compared to the general population. This disproportionate burden of cervical cancer in Indigenous women in both high- and low-and-middle-income countries could be explained by substantially lower rates of HPV vaccination (79–81), lower cervical screening coverage and longer time to clinical investigation (67, 82–85) in Indigenous women compared to non-Indigenous women. Numerous multifaceted barriers have been identified that hinder proper access for Indigenous women to HPV vaccination and cervical cancer screening and treatment (Table 2). While many of these obstacles are not exclusive to Indigenous individuals, the intricate interplay of structural, social and cultural barriers in cervical cancer prevention, diagnosis and treatment uniquely challenges Indigenous women, contributing to their disproportionate burden of this disease.

Table 2. Main barriers to HPV vaccination and cervical cancer screening in Indigenous population globally.

3.1 Structural barriers

Structural impediments play a pivotal role in limiting cervical cancer screening for Indigenous women. Most of them live in rural areas, where distance from health care centers and practitioners, coupled with the lack of personal resources, limit access to appropriate and timely health care, and pose challenges to screening, diagnosis and treatment (82, 88, 97, 103, 107, 110, 113). Furthermore, fragmentation of healthcare systems and economic constraints present additional challenges to the implementation of specific programs for prevention and control of cervical cancer among Indigenous women (23, 89, 90, 103, 106, 107, 110) (Table 2).

3.2 Social determinants

A complex interplay of social determinants, including limited health literacy, low education rates, low socioeconomic status, and isolation, exacerbates barriers to health services. Lack of awareness of cervical cancer and limited understanding of HPV role in its etiology has been identified as one of the main barrier contributing to low screening rates and HPV vaccination coverage among Indigenous women worldwide (see Table 2).

3.3 Cultural factors

Indigenous women often face discrimination and challenges in accessing culturally safe cervical screening and treatment services. Cultural differences and language barriers contribute to communication challenges with health care providers (82, 98, 99, 109, 110, 112). Furthermore, colonization disrupted Indigenous knowledge systems, de-valuing traditional practices and creating historical mistrust impacting their willingness to undergoing gynecological inspections and cervical cytology invasive procedure, as well as to participate in vaccination campaign (81, 114). Thus, mistrust in healthcare systems and HPV vaccines appears to be the first barrier to cervical cancer prevention and control among Indigenous women globally (see Table 2). Finally, community sensitivities regarding sexual health promotion and sexually transmitted diseases were also identified as one of the main limitation to both HPV vaccination and cervical cancer screening.

4 Strategies to improve cervical screening and HPV vaccination uptake for Indigenous women in Latin America and the Caribbean: recommendations for action

Cervical cancer poses a significant public health challenge for Indigenous women globally, demanding targeted strategies in response to the unique cultural and systemic factors hindering cervical screening and HPV vaccination uptake in Indigenous populations. Canada, Australia and New Zealand have implemented specific programs and initiatives of cancer screening and/or HPV vaccination that are showing promising results in reducing HPV-related diseases among Indigenous populations (97, 115–121). While taking example from these successful policies and strategies, it is imperative to devise solutions adapted to the socio-economic realities of LAC countries and the cultural diversity within Indigenous populations residing in the region.

4.1 Cultural sensitivity and education

Works in collaboration within Métis Nation communities in Canada have highlighted the importance of culturally-sensitive educational approaches to promote cervical cancer awareness and vaccination and to address misconceptions (115). Implementing culturally appropriate programs and ensuring that health care practitioners receive adequate support and resources to be able to incorporate cultural components into the delivery of information have been demonstrated to improve screening rates and HPV vaccination uptake among Indigenous women and adolescents in high-income countries (100, 102, 106, 114, 122, 123).

4.2 Community engagement and empowerment

Recognizing the influence of cultural factors on decision-making is crucial. Research from Canada and Australia has demonstrated that indigenous leadership plays a pivotal role in shaping research priorities, providing policy guidance, and developing strategies that are acceptable, appropriate and sustainable for Indigenous communities (64, 107, 116, 124).

Prioritizing collaboration with Indigenous leaders, strengthening intergenerational relationships and ensuring community involvement in program development and delivery are essential components for the success of HPV vaccination and cancer screening initiatives in high-income countries (97, 114). Community and peer support has been shown to positively contribute to overcoming negative attitudes toward cervical screening and vaccination cervical cancer screening barriers in Australia (120, 125), the United States (126) and Peru (127).

Finally, implementing mobile medical clinics to offer essential services has demonstrated its cost-effectiveness in overcoming access barriers for rural populations in low- and middle-income countries like South Africa (128) and Peru (129).

4.3 HPV self-testing implementation

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based testing for high-risk HPVs on cervical or vaginal samples is now the gold standard for cervical cancer prevention (15). This screening method has shown higher sensitivity and negative predictive value compared to the Pap cytology test, thus allowing for larger intervals between screenings and providing greater protection against developing invasive cervical cancers (130–133). Another advantage of HPV testing is that self-collected vaginal samples can be used, which can reduce cost, is noninvasive, and thus emerges as a promising solution to increase screening participation in settings with limited resources, access to health services, or where cultural barriers exist (134–139). In particular, self-collected HPV testing has been shown to be better accepted among Indigenous women in Australia (108, 140), New Zealand (141, 142) and Guatemala (143). Accordingly, in recent years, the Ministry of Health of Guatemala has worked to implement self-collection for HPV testing as an alternative screening method to increase screening coverage in vulnerable populations, especially rural and Indigenous women (144, 145). To the best of available information, this is the only governmental initiative dedicated to improve cervical cancer prevention and control among Indigenous populations that has been implemented in a LAC country.

5 Conclusion

Because they experience higher levels of poverty and health inequities, Indigenous women worldwide are more vulnerable to cervical cancer than non-Indigenous women. In high-income countries, the disproportionately high burden of cervical cancer among Indigenous populations has been extensively characterized. Studies have consistently revealed a higher prevalence of HPV infection and increased incidence and mortality of cervical cancer among Indigenous women compared to their non-Indigenous counterparts. In these countries, targeted programs and initiatives aimed at overcoming the multiple and complex structural, social, and cultural barriers hindering Indigenous women’s access to cervical screening and HPV vaccination are yielding promising results.

On the contrary, in LAC, where Indigenous people constitute 10% of the population, the true extent of the burden of cervical cancer among Indigenous women remains largely unknown. Through an extensive review of published literature, this study presents the currently available data concerning the prevalence of cervical cancer and HPV infection among Indigenous women in LAC, highlighting the paucity of existing data and the critical gaps in research and healthcare interventions that need to be fill. While the findings discussed in this article offer valuable insights, one notable limitation is the absence of a meta-analysis, which could have facilitated a comparative assessment of HPV infection and cervical lesion prevalence rates between Indigenous women in LAC and the general population. Because indigenous status is not recorded in cancer registries of most LAC countries, accurately quantifying and understanding the burden of cervical cancer among Indigenous women in the region remains a challenge. Nevertheless, the limited available data suggest that Indigenous women in LAC face a heightened risk of cervical cancer incidence and mortality, as observed in Indigenous populations in high-income countries.

Strategies to improve cervical screening and HPV vaccination uptake for Indigenous women in LAC must be culturally sensitive, education-focused, and community-engaged. Detailed data on screening behaviors, vaccination uptake, and barriers specific to Indigenous populations in the region are essential. While taking example from successful policies and initiatives implemented in high-income countries, solutions adapted to the socio-economic realities of LAC countries and acknowledging the diversity among the more than 800 Indigenous groups in the region need to be found for bridging existing disparities and achieving the global goal of cervical cancer elimination.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

CM: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author declares that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by Universidad de Las Américas, Quito, Ecuador (Grant number: VET.CM.19.05).

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. de Sanjosé, S, Diaz, M, Castellsagué, X, Clifford, G, Bruni, L, Muñoz, N, et al. Worldwide prevalence and genotype distribution of cervical human papillomavirus DNA in women with normal cytology: a meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. (2007) 7:453–9. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70158-5

2. Forman, D, de Martel, C, Lacey, CJ, Soerjomatarama, I, Lortet-Tieulent, J, Bruni, L, et al. Global burden of human papillomavirus and related diseases. Vaccine. (2012) 30:F12–23. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.07.055

3. Bruni, L, Albero, G, Rowley, J, Alemany, L, Arbyn, M, Giuliano, AR, et al. Global and regional estimates of genital human papillomavirus prevalence among men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. (2023) 11:e1345–62. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(23)00305-4

4. Rodríguez, AC, Schiffman, M, Herrero, R, Wacholder, S, Hildesheim, A, Castle, PE, et al. Rapid clearance of human papillomavirus and implications for clinical focus on persistent infections. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. (2008) 100:513–7. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn044

5. Doorbar, J, Quint, W, Banks, L, Bravo, IG, Stoler, M, Broker, TR, et al. The biology and life-cycle of human papillomaviruses. Vaccine. (2012) 30:F55–70. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.06.083

6. Chan, CK, Aimagambetova, G, Ukybassova, T, Kongrtay, K, and Azizan, A. Human papillomavirus infection and cervical Cancer: epidemiology, screening, and vaccination - review of current perspectives. J Oncol. (2019) 2019:1–11. doi: 10.1155/2019/3257939

7. Organization WH. Human papillomavirus vaccines: WHO position paper, December 2022. (2022) [cited 2023 Nov 4]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/who-wer9750-645-672

8. Cuzick, J, Arbyn, M, Sankaranarayanan, R, Tsu, V, Ronco, G, Mayrand, MH, et al. Overview of human papillomavirus-based and other novel options for cervical Cancer screening in developed and developing countries. Vaccine. (2008) 26:K29–41. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.06.019

9. Checchi, M, Mesher, D, Panwar, K, Anderson, A, Beddows, S, and Soldan, K. The impact of over ten years of HPV vaccination in England: surveillance of type-specific HPV in young sexually active females. Vaccine. (2023) 41:6734–44. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2023.10.002

10. Palmer, T, Wallace, L, Pollock, KG, Cuschieri, K, Robertson, C, Kavanagh, K, et al. Prevalence of cervical disease at age 20 after immunisation with bivalent HPV vaccine at age 12-13 in Scotland: retrospective population study. BMJ. (2019) 365:l1161. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l1161

11. Chow, EPF, Machalek, DA, Tabrizi, SN, Danielewski, JA, Fehler, G, Bradshaw, CS, et al. Quadrivalent vaccine-targeted human papillomavirus genotypes in heterosexual men after the Australian female human papillomavirus vaccination programme: a retrospective observational study. Lancet Infect Dis. (2017) 17:68–77. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30116-5

12. Patel, C, Brotherton, JML, Pillsbury, A, Jayasinghe, S, Donovan, B, Macartney, K, et al. The impact of 10 years of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination in Australia: what additional disease burden will a nonavalent vaccine prevent? Eur Secur. (2018) 23:30–40. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2018.23.41.1700737

13. Sankaranarayanan, R, Gaffikin, L, Jacob, M, Sellors, J, and Robles, S. A critical assessment of screening methods for cervical neoplasia. Int J Gynecol Obstet. (2005) 89:S4–S12. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2005.01.009

14. Ferlay, J, Soerjomataram, I, Dikshit, R, Eser, S, Mathers, C, Rebelo, M, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. (2015) 136:E359–86. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210

15. World Health Organization. Global strategy to accelerate the elimination of cervical cancer as a public health problem. (2020) [cited 2023 Nov 4]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240014107

16. Singh, GK, Azuine, RE, and Siahpush, M. Global inequalities in cervical Cancer incidence and mortality are linked to deprivation, low socioeconomic status, and human development. Int J Matern Child Heal AIDS. (2012) 1:17–30. doi: 10.21106/ijma.12

17. de Martel, C, Georges, D, Bray, F, Ferlay, J, and Clifford, GM. Global burden of cancer attributable to infections in 2018: a worldwide incidence analysis. Lancet Glob Health. (2020) 8:e180–90. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30488-7

18. Sung, H, Ferlay, J, Siegel, RL, Laversanne, M, Soerjomataram, I, Jemal, A, et al. Global Cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. (2021) 71:209–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660

19. Vaccarella, S, Laversanne, M, Ferlay, J, and Bray, F. Cervical cancer in Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean and Asia: regional inequalities and changing trends. Int J Cancer. (2017) 141:1997–2001. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30901

20. Pilleron, S, Cabasag, CJ, Ferlay, J, Bray, F, Luciani, S, Almonte, M, et al. Cervical cancer burden in Latin America and the Caribbean: where are we? Int J Cancer. (2020) 147:1638–48. doi: 10.1002/ijc.32956

21. Torres-Roman, JS, Ronceros-Cardenas, L, Valcarcel, B, Bazalar-Palacios, J, Ybaseta-Medina, J, Carioli, G, et al. Cervical cancer mortality among young women in Latin America and the Caribbean: trend analysis from 1997 to 2030. BMC Public Health. (2022) 22:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-12413-0

22. Nogueira-Rodrigues, A, Flores, MG, Macedo Neto, AO, Braga, LAC, Vieira, CM, de Sousa-Lima, RM, et al. HPV vaccination in Latin America: coverage status, implementation challenges and strategies to overcome it. Front Oncol. (2022) 12:984449. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.984449

23. Fernández-Deaza, G, Serrano, B, Roura, E, Castillo, JS, Caicedo-Martínez, M, Bruni, L, et al. Cervical cancer screening coverage in the Americas region: a synthetic analysis. Lancet Reg Heal - Am. (2024) 30:100689. doi: 10.1016/j.lana.2024.100689

24. Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL)/Fondo para el Desarrollo de los Pueblos Indígenas de América Latina y el Caribe (FILAC), “Los pueblos indígenas de América Latina - Abya Yala y la Agenda 2030 para el Desarrollo Sostenible: tensiones y desafíos desde una perspectiva territorial”, Documentos de Proyectos (LC/TS.2020/47), Santiago, 2020.

25. UNHCR. The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples: A Manual for National Human Rights Institutions. (2013). 152 p. Available from: http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/IPeoples/UNDRIPManualForNHRIs.pdf

26. Moore, SP, Forman, D, Piñeros, M, Fernández, SM, de Oliveira, SM, and Bray, F. Cancer in indigenous people in Latin America and the Caribbean: a review. Cancer Med. (2014) 3:70–80. doi: 10.1002/cam4.134

27. Tonon, SA, Picconi, MA, Zinovich, JB, Nardari, W, Mampaey, M, Badano, I, et al. Human papillomavirus cervical infection in Guarani Indians from the rainforest of Misiones. Argentina Int J Infect Dis. (2004) 8:13–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2003.03.001

28. Deluca, GD, Basiletti, J, González, JV, Vásquez Díaz, N, Lucero, RH, and Picconi, MA. Human papilloma virus risk factors for infection and genotype distribution in aboriginal women from northern Argentina. Med (Buenos Aires). (2012) 72:461–6.

29. Taborda, WC, Ferreira, SC, Rodrigues, D, Stávale, JN, and Baruzzi, RG. Cervical cancer screening among indigenous women in the Xingu Indian reservation, Central Brazil. Rev Panam Salud Publica. (2000) 7:92–6. doi: 10.1590/S1020-49892000000200004

30. Brito, EB, Martins, SJ, and Menezes, RC. Human papillomaviruses in Amerindian women from Brazilian Amazonia. Epidemiol Infect. (2002) 128:485–9. doi: 10.1017/S0950268802006908

31. Rodrigues, DA, Ribeiro Pereira, É, de Souza Oliveira, LS, de Góis Speck, NM, and Gimeno, SGA. Prevalence of cytological atypia and high-risk human papillomavirus infection in Panará indigenous women in Central Brazil. Cad Saude Publica. (2014) 30:2587–93. doi: 10.1590/0102-311x000152713

32. Fonseca, AJ, Taeko, D, Chaves, TA, Da Costa Amorim, LD, Murari, RSW, Miranda, AE, et al. HPV infection and cervical screening in socially isolated indigenous women inhabitants of the Amazonian rainforest. PLoS One. (2015) 10:e0133635. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133635

33. Nascimento, M d DSB, Vidal, FCB, Silva, MACN d, Batista, JE, Lacerda Barbosa, M d C, Muniz Filho, WE, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus infection among women from Quilombo communities in northeastern Brazil. BMC Womens Health. (2018) 18:1. doi: 10.1186/s12905-017-0499-3

34. Barbosa, MDS, Andrade de Souza, IB, Schnaufer, ECDS, Da, SLF, Maymone Gonçalves, CC, Simionatto, S, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with trichomonas vaginalis infection in indigenous Brazilian women. PLoS One. (2020) 15:e0240323. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240323

35. Novais, IR, Coelho, CO, Machado, HC, Surita, F, Zeferino, LC, and Vale, DB. Cervical cancer screening in Brazilian Amazon indigenous women: towards the intensification of public policies for prevention. PLoS One. (2023) 18:e0294956. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0294956

36. Brito, EB, Silva, IDC, Stávale, JN, Taromaru, E, Menezess, RC, and Martins, SJ. Amerindian women of the Brazilian Amazon and STD. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. (2006) 27:279–81.

37. Camargo, M, Soto-De Leon, SC, Sanchez, R, Perez-Prados, A, Patarroyo, ME, and Patarroyo, MA. Frequency of human papillomavirus infection, coinfection, and association with different risk factors in Colombia. Ann Epidemiol. (2011) 21:204–13. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.11.003

38. Sarmiento-Medina, MI, de Amaya, MP, Villamizar-Gómez, L, González-Coba, AC, and Guzmán-Barajas, L. High-risk HPV prevalence and vaccination coverage among indigenous women in the Colombian Amazon: implications for cervical cancer prevention. Cross-sectional study. PLoS One. (2024) 19:e0297579. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0297579

39. Carrión Ordoñez, JI, Soto Brito, Y, Pupo Antúnez, M, and Loja, CR. Infección por Virus del Papiloma Humano y citología cérvico-vaginal en mujeres indígenas del Cañar, Ecuador. Bionatura. (2019) 4:934–8. doi: 10.21931/RB/2019.04.03.10

40. Ortiz Segarra, J, Vega Crespo, B, Campoverde Cisneros, A, Salazar Torres, K, Delgado López, D, and Ortiz, S. Human papillomavirus prevalence and associated factors in indigenous women in Ecuador: a cross-sectional analytical study. Infect Dis Rep. (2023) 15:267–78. doi: 10.3390/idr15030027

41. Kightlinger, RS, Irvin, WP, Archer, KJ, Huang, NW, Wilson, RA, Doran, JR, et al. Cervical cancer and human papillomavirus in indigenous Guyanese women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. (2010) 202:626.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.03.015

42. Velázquez, C, Kawabata, A, and Ríos-González, CM. Prevalence of precursor lesions of cervical cancer and sexual/reproductive antecedents of natives of Caaguazú, Paraguay 2015-2017. Rev salud pública Paraguay. (2018) 8:15–P20. doi: 10.18004/rspp.2018.diciembre.15-20

43. Mendoza, L, Mongelos, P, Paez, M, Castro, A, Rodriguez-Riveros, I, Gimenez, G, et al. Human papillomavirus and other genital infections in indigenous women from Paraguay: a cross-sectional analytical study. BMC Infect Dis. (2013) 13:531. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-531

44. Blas, MM, Alva, IE, Garcia, PJ, Carcamo, C, Montano, SM, Muñante, R, et al. Association between human papillomavirus and human T-Lymphotropic virus in indigenous women from the Peruvian Amazon. PLoS One. (2012) 7:e44240. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044240

45. Martorell, M, Garcia-Garcia, JA, Gomez-Cabrero, D, and Del Aguila, A. Comparison of the prevalence and distribution of human papillomavirus infection and cervical lesions between urban and native habitants of an Amazonian region of Peru. Genet Mol Res. (2012) 11:2099–106. doi: 10.4238/2012.August.6.14

46. Nicita, G, Reigosa, A, Torres, J, Vázquez, C, Fernández, Y, Álvarez, M, et al. Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection in an indigenous population of the Venezuelan Amazon. Salus. (2010) 14:51–9.

47. Fuenmayor, A, Fernández, C, Pérez, V, Coronado, J, Ávila, M, Fernandes, A, et al. Detection of precancerous lesions in the cervix and HPV infection in women in the region of Maniapure. Bolivar State Ecancermedicalscience. (2018) 12:884. doi: 10.3332/ecancer.2018.884

48. Vargas-Robles, D, Magris, M, Morales, N, de Koning, MNC, Rodríguez, I, Nieves, T, et al. High rate of infection by only oncogenic human papillomavirus in Amerindians. mSphere. (2018) 3:e00176-18. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00176-18

49. Jeffries, A, Beck-Sagué, CM, Marroquin-Garcia, AB, Dean, M, McCoy, V, Cordova-Toma, DA, et al. Cervical visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) and oncogenic human papillomavirus screening in rural indigenous Guatemalan women: time to rethink VIA. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:12406. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182312406

50. Torres-Rojas, FI, Mendoza-Catalán, MA, Alarcón-Romero, LDC, Parra-Rojas, I, Paredes-Solís, S, Leyva-Vázquez, MA, et al. HPV molecular detection from urine versus cervical samples: an alternative for HPV screening in indigenous populations. PeerJ. (2021) 9:e11564. doi: 10.7717/peerj.11564

51. Ministério da Saude - Instituto Nacional de Câncer José Alencar Gomes da Silva (INCA). Coordenação Geral de Prevenção e Vigilância (CGPV), Divisão de Vigilância e Análise de Situação. Manual de rotinas e procedimentos para registros de câncer de base populacional. Instituto Nacional de Câncer José Alencar Gomes da Silva, Coordenação Geral de Prevenção e Vigilância, Divisão de Vigilância e Análise de Situação. 2. ed. rev. atual. Rio de Janeiro: Inca. (2012). 240 p.

52. Comision contra el Cancer - Registro Nacional de Cancer. Registro Nacional de Cáncer, Uruguay - Material para Buscadores de Datos. Registro Nacional de Cáncer - Área Vigilancia Epidemiológica, Área de Capacitación Técnico Profesional. (2019). 26 p.

53. Best Plummer, WS, Persaud, P, and Layne, PJ. Ethnicity and cancer in Guyana, South America. Infect Agent Cancer. (2009) 4:S7. doi: 10.1186/1750-9378-4-S1-S7

54. Gobierno de la República de Guatemala, Ministerio de Salud Pública y Asistencia Social. Protoco de estudio: Evaluacion de alternativas para la deteccion temprana de cáncer cervicouterino en Guatemala. Gobierno de la República de Guatemala, Ministerio de Salud Pública y Asistencia Social. (2018). 37 p.

55. Brau-Figueroa, H, Palafox-Parrilla, EA, Mohar-Betancourt, A, Brau-Figueroa, H, Palafox-Parrilla, EA, and Mohar-Betancourt, A. El Registro Nacional de Cáncer en México, una realidad. Gac Mex Oncol. (2020) 19:107–11. doi: 10.24875/j.gamo.20000030

56. Government of the United States Virgin Islands, Department of Health. Virgin Islands Central Cancer Registry - Physician’s Cancer Report Form. Government of the United States Virgin Islands, Department of Health. (2016). 2 p.

57. Davis-Castro, CY. Indigenous peoples in Latin America: Statistical Information. (Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service). (2023). 34 p.

58. Axelsson, P, Kukutai, T, and Kippen, R. The field of indigenous health and the role of colonisation and history. J Popul Res. (2016) 33:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s12546-016-9163-2

59. Pan American Health Organization. The Sociodemographic Situation of Indigenous Peoples in Latin America and the Caribbean. Analysis in the Context of Aging and COVID-19. Washington, D.C.: PAHO. (2023). Available from: https://doi.org/10.37774/9789275126479.

60. International Labour Organization. Implementing the ILO Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention No. 169: Towards an inclusive, sustainable and just future. (2019). 160 p. Available from: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/---publ/documents/publication/wcms_735607.pdf

61. Montenegro, RA, and Stephens, C. Indigenous health in Latin America and the Caribbean. Lancet (London, England). (2006) 367:1859–69. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68808-9

62. Moore, SP, Antoni, S, Colquhoun, A, Healy, B, Ellison-Loschmann, L, Potter, JD, et al. Cancer incidence in indigenous people in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the USA: a comparative population-based study. Lancet Oncol. (2015) 16:1483–92. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00232-6

63. Ministry of Health. Tatau Kahukura Māori health chart book 2015 (3rd edition). (2015). 68 p. Available from: https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/tatau-kahukura-maori-health-chart-book-2015-3rd-edition

64. Lawton, B, Heffernan, M, Wurtak, G, Steben, M, Lhaki, P, Cram, F, et al. IPVS policy statement addressing the burden of HPV disease for indigenous peoples. Papillomavirus Res. (2020) 9:100191. doi: 10.1016/j.pvr.2019.100191

65. Vasilevska, M, Ross, SA, Gesink, D, and Fisman, DN. Relative risk of cervical cancer in indigenous women in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Public Health Policy. (2012) 33:148–64. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2012.8

66. Simkin, J, Smith, L, van Niekerk, D, Caird, H, Dearden, T, van der Hoek, K, et al. Sociodemographic characteristics of women with invasive cervical cancer in British Columbia, 2004-2013: a descriptive study. C open. (2021) 9:E424–32. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20200139

67. Mazereeuw, MV, Withrow, DR, Nishri, ED, Tjepkema, M, Vides, E, and Marrett, LD. Cancer incidence and survival among Métis adults in Canada: results from the Canadian census follow-up cohort (1992-2009). Can Med Assoc J. (2018) 190:E320–6. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.170272

68. Supramaniam, R, Grindley, H, and Pulver, LJ. Cancer mortality in aboriginal people in New South Wales, Australia, 1994-2002. Aust N Z J Public Health. (2006) 30:453–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842X.2006.tb00463.x

69. Sethi, S, Ali, A, Ju, X, Antonsson, A, Logan, R, Canfell, K, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of human papillomavirus infection in indigenous populations – a global picture. J Oral Pathol Med. (2021) 50:843–54. doi: 10.1111/jop.13201

70. Jiang, Y, Brassard, P, Severini, A, Goleski, V, Santos, M, Leamon, A, et al. Type-specific prevalence of human papillomavirus infection among women in the Northwest Territories, Canada. J Infect Public Health. (2011) 4:219–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2011.09.006

71. Garland, SM, Brotherton, JML, Condon, JR, McIntyre, PB, Stevens, MP, Smith, DW, et al. Human papillomavirus prevalence among indigenous and non-indigenous Australian women prior to a national HPV vaccination program. BMC Med. (2011) 9:1–14. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-104

72. Bennett, R, Cerigo, H, Coutlée, F, Roger, M, Franco, EL, and Brassard, P. Incidence, persistence, and determinants of human papillomavirus infection in a population of Inuit women in northern Quebec. Sex Transm Dis. (2015) 42:272–8. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000272

73. Góes, EF, Guimarães, JMN, da CC, AM, Gabrielli, L, Katikireddi, SV, Campos, AC, et al. The intersection of race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status: inequalities in breast and cervical cancer mortality in 20,665,005 adult women from the 100 million Brazilian cohort. Ethn Health. (2024) 29:46–61. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2023.2245183

74. de Melo, AC, da Silva, JL, dos Santos, ALS, and Thuler, LCS. Population-based trends in cervical Cancer incidence and mortality in Brazil: focusing on Black and indigenous population disparities. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. (2024) 11:255–63. doi: 10.1007/s40615-023-01516-6

75. de SO, BMF, Koifman, S, Koifman, RJ, and da Silva, IF. Cancer incidence in indigenous populations of Western Amazon, Brazil. Ethn Health. (2022) 27:1465–81. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2021.1893663

76. Colpani, V, Falcetta, FS, Bidinotto, AB, Kops, NL, Falavigna, M, Hammes, LS, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus (HPV) in Brazil: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. (2020) 15:e0229154. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229154

77. Bruni, L, Diaz, M, Castellsagué, X, Ferrer, E, Bosch, FX, and De Sanjosé, S. Cervical human papillomavirus prevalence in 5 continents: Meta-analysis of 1 million women with Normal cytological findings. J Infect Dis. (2010) 202:1789–99. doi: 10.1086/657321

78. Ting, J, Rositch, AF, Taylor, SM, Rahangdale, L, Soeters, HM, Sun, X, et al. Worldwide incidence of cervical lesions: a systematic review. Epidemiol Infect. (2015) 143:225. doi: 10.1017/S0950268814001356

79. Shafer, LA, Jeffrey, I, Elias, B, Shearer, B, Canfell, K, and Kliewer, E. Quantifying the impact of dissimilar HPV vaccination uptake among Manitoban school girls by ethnicity using a transmission dynamic model. Vaccine. (2013) 31:4848–55. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.07.073

80. Brotherton, JML, Winch, KL, Chappell, G, Banks, C, Meijer, D, Ennis, S, et al. HPV vaccination coverage and course completion rates for indigenous Australian adolescents, 2015. Med J Aust. (2019) 211:31–6. doi: 10.5694/mja2.50221

81. Poirier, B, Sethi, S, Garvey, G, Hedges, J, Canfell, K, Smith, M, et al. HPV vaccine: uptake and understanding among global indigenous communities – a qualitative systematic review. BMC Public Health. (2021) 21:2062. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-12147-z

82. Gottschlich, A, Ochoa, P, Rivera-Andrade, A, Alvarez, CS, Mendoza Montano, C, Camel, C, et al. Barriers to cervical cancer screening in Guatemala: a quantitative analysis using data from the Guatemala demographic and health surveys. Int J Public Health. (2020) 65:217. doi: 10.1007/s00038-019-01319-9

83. Barcelos, MRB, de Cássia Duarte Lima, R, Tomasi, E, Nunes, BP, SMS, D, and Facchini, LA. Quality of cervical cancer screening in Brazil: external assessment of the PMAQ. Rev Saude Publica. (2017) 51:67. doi: 10.1590/s1518-8787.2017051006802

84. Whop, LJ, Baade, PD, Brotherton, JML, Canfell, K, Cunningham, J, Gertig, D, et al. Time to clinical investigation for indigenous and non-indigenous Queensland women after a high grade abnormal pap smear, 2000-2009. Med J Aust. (2017) 206:73–7. doi: 10.5694/mja16.00255

85. Dasgupta, P, Aitken, JF, Condon, J, Garvey, G, Whop, LJ, DeBats, C, et al. Spatial and temporal variations in cervical cancer screening participation among indigenous and non-indigenous women, Queensland, Australia, 2008-2017. Cancer Epidemiol. (2020) 69:101849. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2020.101849

86. Gopalani, SV, Janitz, AE, Burkhart, M, Campbell, JE, Chen, S, Martinez, SA, et al. HPV vaccination coverage and factors among American Indians in Cherokee nation. Cancer Causes Control. (2023) 34:267. doi: 10.1007/s10552-022-01662-y

87. Bowen, DJ, Weiner, D, Samos, M, and Canales, MK. Exploration of New England native American Women’s views on human papillomavirus (HPV), testing, and vaccination. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. (2014) 1:45–51. doi: 10.1007/s40615-014-0009-3

88. Jacobs-Wingo, JL, Jim, CC, and Groom, AV. Human papillomavirus vaccine uptake: increase for American Indian adolescents, 2013–2015. Am J Prev Med. (2017) 53:162. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.01.024

89. Duvall, J, and Buchwald, D. Human papillomavirus vaccine policies among American Indian tribes in Washington state. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. (2012) 25:131. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2011.11.012

90. Schmidt-Grimminger, D, Frerichs, L, Black Bird, AE, Workman, K, Dobberpuhl, M, and Watanabe-Galloway, S. HPV knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs among Northern Plains American Indian adolescents, parents, young adults, and health professionals. J Cancer Educ. (2013) 28:357–66. doi: 10.1007/s13187-013-0468-y

91. Hodge, FS, Itty, T, Cardoza, B, and Samuel-Nakamura, C. HPV vaccine readiness among American Indian college students. Ethn Dis. (2011) 21:415–20.

92. Buchwald, D, Muller, C, Bell, M, and Schmidt-Grimminger, D. Attitudes toward HPV vaccination among rural American Indian women and urban white women in the Northern Plains. Health Educ Behav. (2013) 40:704–11. doi: 10.1177/1090198113477111

93. Kemberling, M, Hagan, K, Leston, J, Kitka, S, Provost, E, and Hennessy, T. Alaska native adolescent views on cervical cancer, the human papillomavirus (HPV), genital warts and the quadrivalent HPV vaccine. Int J Circumpolar Health. (2011) 70:245–53. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v70i3.17829

94. Toffolon-Weiss, M, Hagan, K, Leston, J, Peterson, L, Provost, E, and Hennessy, T. Alaska native parental attitudes on cervical cancer, HPV and the HPV vaccine. Int J Circumpolar Health. (2008) 67:363–73. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v67i4.18347

95. Jim, CC, Wai-Yin Lee, J, Groom, AV, Espey, DK, Saraiya, M, Holve, S, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination practices among providers in Indian Health Service, tribal and urban Indian healthcare facilities. J Women's Health. (2012) 21:372–8. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2011.3417

96. Dela Cruz, MRI, Braun, KL, Tsark, JAU, Albright, CL, and Chen, JJ. HPV vaccination prevalence, parental barriers and motivators to vaccinating children in Hawai’i. Ethn Health. (2020) 25:982. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2018.1473556

97. Henderson, RI, Shea-Budgell, M, Healy, C, Letendre, A, Bill, L, Healy, B, et al. First nations people’s perspectives on barriers and supports for enhancing HPV vaccination: foundations for sustainable, community-driven strategies. Gynecol Oncol. (2018) 149:93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.12.024

98. Kelly-Hanku, A, Newland, J, Aggleton, P, Ase, S, Aeno, H, Fiya, V, et al. HPV vaccination in Papua New Guinea to prevent cervical cancer in women: gender, sexual morality, outsiders and the de-feminization of the HPV vaccine. Papillomavirus Res. (2019) 8:100171. doi: 10.1016/j.pvr.2019.100171

99. De La Cruz-Ramirez, YM, and Olaza-Maguiña, AF. Barriers to HPV vaccine uptake in adolescents of the indigenous Andean community of Peru. Int J Gynecol Obstet. (2023) 162:187–9. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.14844

100. Tratt, E, Sarmiento, I, Gamelin, R, Nayoumealuk, J, Andersson, N, and Brassard, P. Fuzzy cognitive mapping with Inuit women: what needs to change to improve cervical cancer screening in Nunavik, northern Quebec? BMC Health Serv Res. (2020) 20:529. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05399-9

101. Cerigo, H, Macdonald, ME, Franco, EL, and Brassard, P. Inuit women’s attitudes and experiences towards cervical cancer and prevention strategies in Nunavik, Quebec. Int J Circumpolar Health. (2012) 71:17996. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v71i0.17996

102. Wakewich, P, Wood, B, Davey, C, Laframboise, A, and Zehbe, I. Colonial legacy and the experience of first nations women in cervical cancer screening: a Canadian multi-community study. Crit Public Health. (2016) 26:368–80. doi: 10.1080/09581596.2015.1067671

103. Maar, M, Burchell, A, Little, J, Ogilvie, G, Severini, A, Yang, JM, et al. A qualitative study of provider perspectives of structural barriers to cervical Cancer screening among first nations women. Womens Health Issues. (2013) 23:e319–25. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2013.06.005

104. O’Brien, BA, Mill, J, and Wilson, T. Cervical screening in Canadian first nation Cree women. J Transcult Nurs. (2009) 20:83–92. doi: 10.1177/1043659608322418

105. Butler, TL, Lee, N, Anderson, K, Brotherton, JML, Cunningham, J, Condon, JR, et al. Under-screened aboriginal and Torres Strait islander women’s perspectives on cervical screening. PLoS One. (2022) 17:e0271658. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0271658

106. Jaenke, R, Butler, TL, Condon, J, Garvey, G, Brotherton, JML, Cunningham, J, et al. Health care provider perspectives on cervical screening for aboriginal and Torres Strait islander women: a qualitative study. Aust N Z J Public Health. (2021) 45:150–7. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.13084

107. Manderson, L, and Hoban, E. Cervical cancer services for indigenous women: advocacy, community-based research and policy change in Australia. Women Health. (2006) 43:69–88. doi: 10.1300/J013v43n04_05

108. Adcock, A, Cram, F, Lawton, B, Geller, S, Hibma, M, Sykes, P, et al. Acceptability of self-taken vaginal HPV sample for cervical screening among an under-screened indigenous population. Aust New Zeal J Obstet Gynaecol. (2019) 59:301–7. doi: 10.1111/ajo.12933

109. Kelly-Hanku, A, Ase, S, Fiya, V, Toliman, P, Aeno, H, Mola, GM, et al. Ambiguous bodies, uncertain diseases: knowledge of cervical cancer in Papua New Guinea. Ethn Health. (2018) 23:659–81. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2017.1283393

110. Allen-Leigh, B, Uribe-Zúñiga, P, León-Maldonado, L, Brown, BJ, Lörincz, A, Salmeron, J, et al. Barriers to HPV self-sampling and cytology among low-income indigenous women in rural areas of a middle-income setting: a qualitative study. BMC Cancer. (2017) 17:734. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3723-5

111. Warner, ZC, Reid, B, Auguste, P, Joseph, W, Kepka, D, and Warner, EL. Awareness and knowledge of HPV, HPV vaccination, and cervical Cancer among an indigenous Caribbean community. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:5694. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19095694

112. Nugus, P, Désalliers, J, Morales, J, Graves, L, Evans, A, and Macaulay, AC. Localizing global medicine: challenges and opportunities in cervical screening in an indigenous Community in Ecuador. Qual Health Res. (2018) 28:800–12. doi: 10.1177/1049732317742129

113. Nevin, PE, Garcia, PJ, Blas, MM, Rao, D, and Molina, Y. Inequities in cervical Cancer Care in Indigenous Peruvian Women. Lancet Glob Health. (2019) 7:e556–7. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30044-0

114. MacDonald, SE, Kenzie, L, Letendre, A, Bill, L, Shea-Budgell, M, Henderson, R, et al. Barriers and supports for uptake of human papillomavirus vaccination in indigenous people globally: a systematic review. PLOS Glob Public Heal. (2023) 3:e0001406. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0001406

115. Letendre, A, Khan, M, Bartel, R, Chiang, B, James, A, Shewchuk, B, et al. Creation of a Métis-specific instrument for Cancer screening: a scoping review of Cancer-screening programs and instruments. Curr Oncol. (2023) 30:9849–59. doi: 10.3390/curroncol30110715

116. Jumah, NA, Kewayosh, A, Downey, B, Campbell Senese, L, and Tinmouth, J. Developing a health equity impact assessment ‘indigenous Lens tool’ to address challenges in providing equitable cancer screening for indigenous peoples. BMC Public Health. (2023) 23:2250. doi: 10.1186/s12889-023-16919-7

117. Lawton, B, MacDonald, EJ, Storey, F, Stanton, JA, Adcock, A, Gibson, M, et al. A model for empowering rural solutions for cervical Cancer prevention (he Tapu Te Whare Tangata): protocol for a cluster randomized crossover trial. JMIR Res Protoc. (2023) 12:e51643. doi: 10.2196/51643

118. McGregor, S, Saulo, D, Brotherton, J, Liu, B, Phillips, S, Skinner, SR, et al. Decline in prevalence of human papillomavirus infection following vaccination among Australian indigenous women, a population at higher risk of cervical cancer: the VIP-I study. Vaccine. (2018) 36:4311–6. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.05.104

119. Gibson-Helm, M, Slater, T, MacDonald, EJ, Stevenson, K, Adcock, A, Geller, S, et al. Te Ara Waiora–implementing human papillomavirus (HPV) primary testing to prevent cervical cancer in Aotearoa New Zealand: a protocol for a non-inferiority trial. PLoS One. (2023) 18:e0280643. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0280643

120. Moxham, R, Moylan, P, Duniec, L, Fisher, T, Furestad, E, Manolas, P, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, intentions and behaviours of Australian indigenous women from NSW in response to the National Cervical Screening Program changes: a qualitative study. Lancet Reg Heal West Pacific. (2021) 13:100195. doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2021.100195

121. Jackson, J, Sonneveld, N, Rashid, H, Karpish, L, Wallace, S, Whop, L, et al. Vaccine preventable diseases and vaccination coverage in aboriginal and Torres Strait islander people, Australia, 2016-2019. Commun Dis Intell. (2023) 47:127–59. doi: 10.33321/cdi.2023.47.32

122. Jamal, S, Jones, C, Walker, J, Mazereeuw, M, Sheppard, AJ, Henry, D, et al. Cancer in first nations people in Ontario, Canada: incidence and mortality, 1991 to 2010. Heal reports. (2021) 32:14–28. doi: 10.25318/82-003-x202100600002-eng

123. Maxwell, AE, Young, S, Rabelo Vega, R, Cayetano, RT, Crespi, CM, and Bastani, R. Building capacity to address Women’s health issues in the Mixtec and Zapotec community. Womens Health Issues. (2015) 25:403. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2015.03.010

124. Maar, M, Wakewich, P, Wood, B, Severini, A, Little, J, Burchell, AN, et al. Strategies for increasing cervical Cancer screening amongst first nations communities in Northwest Ontario, Canada. Health Care Women Int. (2016) 37:478–95. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2014.959168

125. Butler, TL, Anderson, K, Condon, JR, Garvey, G, Brotherton, JML, Cunningham, J, et al. Indigenous Australian women’s experiences of participation in cervical screening. PLoS One. (2020) 15:e0234536. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0234536

126. Suarez, L, Lloyd, L, Weiss, N, Rainbolt, T, and Pulley, L. Effect of social networks on Cancer-screening behavior of older Mexican-American women. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. (1994) 86:775–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/86.10.775

127. Luque, JS, Opoku, S, Ferris, DG, and Guevara Condorhuaman, WS. Social network characteristics and cervical cancer screening among Quechua women in Andean Peru. BMC Public Health. (2016) 16:181. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-2878-3

128. Schnippel, K, Lince-Deroche, N, Van Den Handel, T, Molefi, S, Bruce, S, and Firnhaber, C. Cost evaluation of reproductive and primary health care Mobile service delivery for women in two rural districts in South Africa. PLoS One. (2015) 10:e0119236. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119236

129. Ferris, DG, Shapiro, J, Fowler, C, Cutler, C, Waller, J, and Condorhuaman, WSG. The impact of accessible cervical Cancer screening in Peru-the Día del Mercado project. J Low Genit Tract Dis. (2015) 19:229–33. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0000000000000112

130. Kulasingam, SL, Hughes, JP, Kiviat, NB, Mao, C, Weiss, NS, Kuypers, JM, et al. Evaluation of human papillomavirus testing in primary screening for cervical abnormalities: comparison of sensitivity, specificity, and frequency of referral. JAMA. (2002) 288:1749–57. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1749

131. Mayrand, M-H, Duarte-Franco, E, Rodrigues, I, Walter, SD, Hanley, J, Ferenczy, A, et al. Human papillomavirus DNA versus Papanicolaou screening tests for cervical Cancer. N Engl J Med. (2007) 357:1579–88. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071430

132. Rijkaart, DC, Berkhof, J, Rozendaal, L, van Kemenade, FJ, Bulkmans, NWJ, Heideman, DAM, et al. Human papillomavirus testing for the detection of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cancer: final results of the POBASCAM randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. (2012) 13:78–88. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70296-0

133. Ronco, G, Dillner, J, Elfström, KM, Tunesi, S, Snijders, PJF, Arbyn, M, et al. Efficacy of HPV-based screening for prevention of invasive cervical cancer: follow-up of four European randomised controlled trials. Lancet. (2014) 383:524–32. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62218-7

134. Mezei, AK, Armstrong, HL, Pedersen, HN, Campos, NG, Mitchell, SM, Sekikubo, M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of cervical cancer screening methods in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Int J Cancer. (2017) 141:437–46. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30695

135. Malone, C, Barnabas, RV, Buist, DSM, Tiro, JA, and Winer, RL. Cost-effectiveness studies of HPV self-sampling: a systematic review. Prev Med (Baltim). (2020) 132:105953. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.105953

136. Toliman, P, Badman, SG, Gabuzzi, J, Silim, S, Forereme, L, Kumbia, A, et al. Field evaluation of Xpert HPV point-of-care test for detection of human papillomavirus infection by use of self-collected vaginal and clinician-collected cervical specimens. J Clin Microbiol. (2016) 54:1734–7. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00529-16

137. Polman, NJ, de Haan, Y, Veldhuijzen, NJ, Heideman, DAM, de Vet, HCW, Meijer, CJLM, et al. Experience with HPV self-sampling and clinician-based sampling in women attending routine cervical screening in the Netherlands. Prev Med (Baltim). (2019) 125:5–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.04.025

138. Gravitt, PE, Belinson, JL, Salmeron, J, and Shah, KV. Looking ahead: a case for human papillomavirus testing of self-sampled vaginal specimens as a cervical cancer screening strategy. Int J Cancer. (2011) 129:517–27. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25974

139. Scarinci, IC, Litton, AG, Garcés-Palacio, IC, Partridge, EE, and Castle, PE. Acceptability and usability of self-collected sampling for HPV testing among African-American women living in the Mississippi Delta. Womens Health Issues. (2013) 23:e123–30. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2012.12.003

140. MacDonald, EJ, Geller, S, Sibanda, N, Stevenson, K, Denmead, L, Adcock, A, et al. Reaching under-screened/never-screened indigenous peoples with human papilloma virus self-testing: a community-based cluster randomised controlled trial. Aust New Zeal J Obstet Gynaecol. (2021) 61:135–41. doi: 10.1111/ajo.13285

141. Bromhead, C, Wihongi, H, Sherman, SM, Crengle, S, Grant, J, Martin, G, et al. Human papillomavirus (Hpv) self-sampling among never-and under-screened indigenous māori, pacific and asian women in aotearoa New Zealand: a feasibility study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:10050. doi: 10.3390/ijerph181910050

142. Brewer, N, Bartholomew, K, Grant, J, Maxwell, A, McPherson, G, Wihongi, H, et al. Acceptability of human papillomavirus (HPV) self-sampling among never- and under-screened indigenous and other minority women: a randomised three-arm community trial in Aotearoa New Zealand. Lancet Reg Heal - West Pacific. (2021) 16:100265. doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2021.100265

143. Gottschlich, A, Rivera-Andrade, A, Grajeda, E, Alvarez, C, Mendoza Montano, C, and Meza, R. Acceptability of human papillomavirus self-sampling for cervical Cancer screening in an indigenous Community in Guatemala. J Glob Oncol. (2017) 3:444–54. doi: 10.1200/JGO.2016.005629

144. Gobierno de Guatemala, Ministerio de Salud Pública y Asistencia Social. Guía de atención integral para la prevención, detección y tratamiento de lesiones precursoras del cáncer cérvico uterino. Gobierno de Guatemala, Ministerio de Salud Pública y Asistencia Social. 2da edición. (2020). 76 p.

Keywords: cervical cancer, HPV, indigenous, Latin America, Caribbean

Citation: Muslin C (2024) Addressing the burden of cervical cancer for Indigenous women in Latin America and the Caribbean: a call for action. Front. Public Health. 12:1376748. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1376748

Edited by:

Rene L. Begay, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, United StatesReviewed by:

Marion Pineros, International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), FranceCopyright © 2024 Muslin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Claire Muslin, Y2xhaXJlLm11c2xpbkBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Claire Muslin

Claire Muslin