94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Public Health, 14 March 2024

Sec. Public Health and Nutrition

Volume 12 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1340149

This article is part of the Research TopicLearning from Global Food and Nutrition InsecurityView all 15 articles

Food security (FS) is a powerful social determinant of health (SDOH) and is crucial for human and planetary health. The objectives of this article are to (i) provide clarity on the definitions of FS and nutrition security; (ii) provide a framework that clearly explains the links between the two constructs; (iii) summarize measurement approaches, and (iv) illustrate applications to monitoring and surveillance, policy and program design and evaluation, and research, mainly based on the ongoing rich experience with food insecurity (FI) scales. A clear and concise definition of FI and corresponding frameworks are available. There are different methods for directly or indirectly assessing FI. The best method(s) of choice need to be selected based on the questions asked, resources, and time frames available. Experience-based FI measures disseminated from the United States to the rest of the world in the early 2000s became a game changer for advancing FI research, policy, program evaluation, and governance. The success with experience FI scales is informing the dissemination, adaptation, and validation of water insecurity scales globally. The many lessons learned across countries on how to advance policy and program design and evaluation through improved FS conceptualization and measurement should be systematically shared through networks of researchers and practitioners.

Food security (FS) is a powerful social determinant of health (SDOH) and is crucial for human and planetary health (1). FS is indeed crucial for nations to meet the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and, in turn, the SDGs need to be met to achieve food and nutrition security for all (1). Unfortunately, there are still many misunderstandings and misconceptions about the definition of the construct of FS, how it relates to nutrition security, and which sound frameworks are needed to guide the research and practice work in this field (2). Hence, the objectives of this article are to (i) provide clarity on the definitions of FS and nutrition security; (ii) provide a framework that clearly explains the links between the two constructs; (iii) summarize measurement approaches, and (iv) illustrate applications to monitoring and surveillance, policy and program design and evaluation, and research, mainly based on the ongoing rich experience with food insecurity (FI) scales.

Based on the 1996 World Summit in Rome hosted by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (3), the United Nations World Food Security Committee defines FS as a condition that exists when “…people, at all times, have physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food which meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life” (4).

Consistent with the United Nations World Food Security definition, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) has defined FS as “access by all people at all times to enough food for an active, healthy life” (5) and specified that “Food security includes at a minimum: (i) the ready availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods, and (ii) the assured ability to acquire acceptable foods in socially acceptable ways (e.g., without resorting to emergency food supplies, scavenging, stealing, or other coping strategies),” hence endorsing the dimension of social acceptability as a core component of the FS construct (5). Furthermore, the US has expressed that an active, healthy life depends on both adequate amounts of food and the proper mix of nutrient-rich food to meet an individual’s nutrition and health needs (ERS-USDA). As a corollary, FI has been defined as a condition that occurs “whenever the availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods, or the ability to acquire acceptable foods in socially acceptable ways is limited or uncertain” (5).

The definition of FS that has been in place for over three decades has made it clear that FS is a multidimensional construct that includes the following dimensions: Quantity, enough calories; Dietary Quality, nutritional value of foods; Food Safety, foods free of harmful microorganisms or other environmental contaminants; Suitability, culturally acceptable; Psycho-emotional, anxiety and feelings of deprivation; and Social Acceptability, socially acceptable methods for acquiring foods (1, 6, 7).

These definitions of FS were strongly informed by the development of FS experience-based scales based on mixed-methods research conducted with people in the US experiencing FI and hunger (the most extreme form of FI) (8), and led to the development, validation, and launch of the US Household Food Security Survey (USHFSSM) module in 1995 (5) and its subsequent dissemination, adaptation, and validation globally (7, 9, 10).

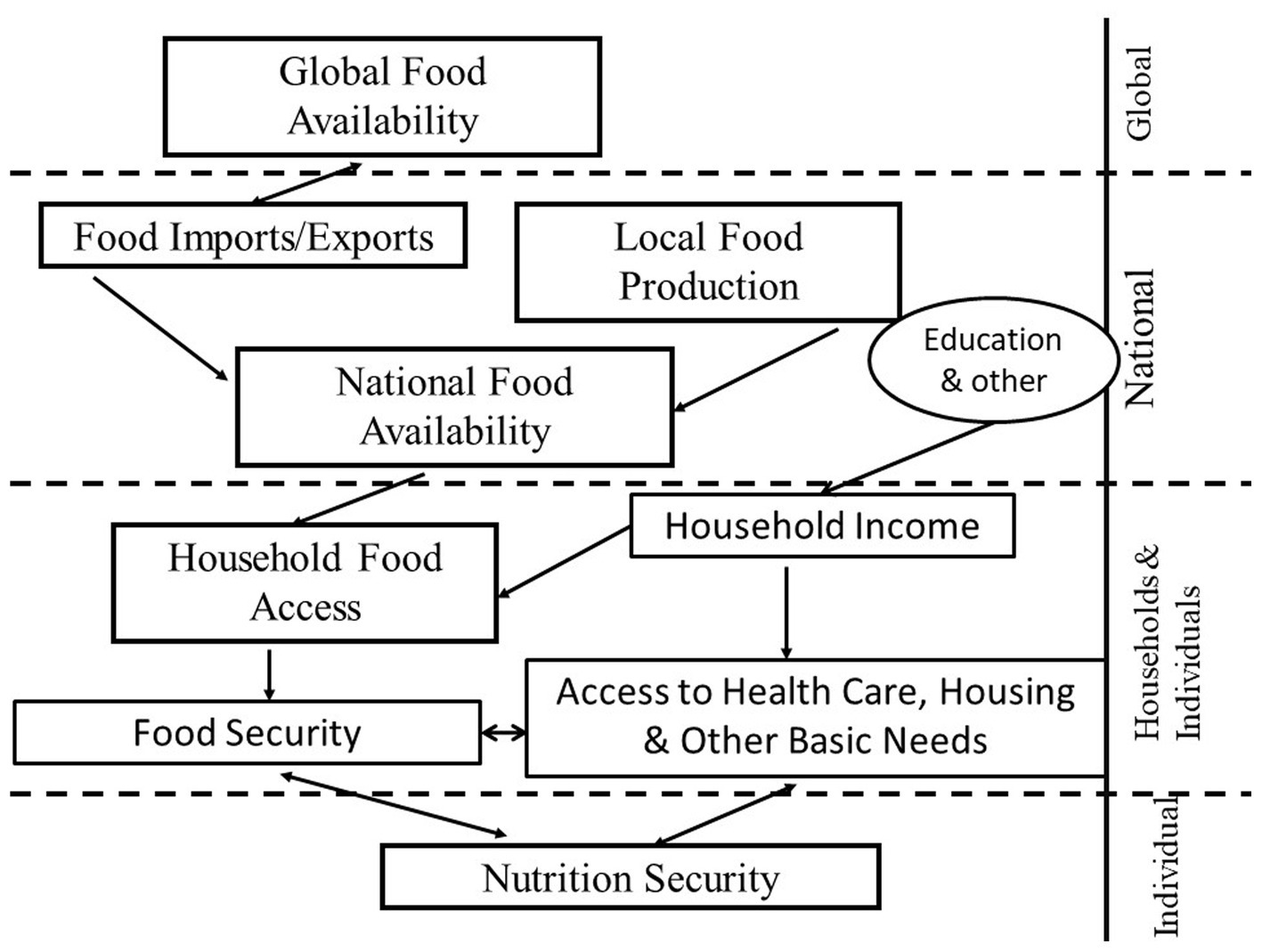

Nutrition status has been defined as “the assimilation and utilization of nutrients by the body plus interactions of environmental factors such as those that affect food consumption and food security” (11). Hence, it is a construct that needs to be assessed and understood by researchers, program evaluators, and policymakers at the level of the individual’s organism. Indeed, Smith presented a clear food and nutrition security multilevel framework (12) adapted from Frankenberger (13) and UNICEF (14), ranging from the global to the individual level to understand the strong relationship between FS and nutrition security and their distinct characteristics (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The relationships between global food security, household food security, and nutrition security. Adapted with permission from Smith (12), Frankenberger et al. (13), and UNICEF (14).

Extensive research involving experience-based FS scales has shown that in human societies, FS needs to be understood at the household level, and that it is a SDOH that, in turn, is strongly determined by socio-economic status and social class (7). FS relies on stable economic, physical, and social access to diverse, healthy, and nutritious foods that are culturally acceptable in the communities where the households are located. This access, in turn, depends on regional, national, and global availability of such foods. Currently, the global availability of these foods is constantly threatened by climate change and armed conflicts across the globe (1).

Nutrition security among individuals is determined by FS in combination with other SDOH, including healthcare access, housing, and other basic human needs such as water security (3, 4, 15).

Food and nutrition security sits right at the intersection of public health and human rights, as reflected in articles from the UN Charter on the Right to Adequate Food (16). For instance, Articles 11 and 12 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) along with children’s rights to food, health, care, survival, and development; Articles 6, 24, and 27 of the Convention on the Civil Rights of the Child (CRC) detailing the rights of mothers to adequate nutrition during pregnancy and lactation; and Article 12.2 of the Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) highlight this intersection. These articles reflect the universal, indivisible, interrelated, and interdependence of the human right to food.

The definition of food and nutrition security in Brazil is an example of how a country can incorporate the domains of human rights, taking the SDOH and environmental sustainability into account. Specifically, the Brazilian Government defines food and nutrition security based on its Organic Law on Food and Nutritional Security (LOSAN—Law No. 11.346, issued on 15 September 2006) as “the realization of everyone’s right to regular and permanent access to quality food, in sufficient quantity, without compromising access to other essential needs, based on health-promoting food practices that respect cultural diversity and are environmentally, culturally, economically and socially sustainable” (17).

It is clear from the definitions of FS used internationally and within countries that the construct of FS has four interrelated dimensions: food availability, access, utilization, and stability (4). Since access to food is key for food and nutrition security, it is important to understand what this construct means and its domains. Food access centers on the stable availability of nourishing, affordable, and suitable food access, shaped by diverse economic, social, commercial, and political structural factors. Physical and economic access to nutritious foods coming from sustainable food production systems are important elements of the food access construct. Hence, the construct of food access has five dimensions: food availability, proximity, affordability, acceptability, and accommodation to cultural preferences (18).

Food and nutrition security can only be attained with stable access to healthy, nutritious, and sustainable diets. These diets should avoid or strongly minimize the inclusion of ultra-processed foods and beverages and maximize the intake of unprocessed or minimally processed foods such as fresh fruits and vegetables, whole grains, and sustainable protein sources, prepared in healthy ways, as well as water (19–21).

There are different methods to assess different dimensions of FS, including aggregated availability to adequate calories and FAO balance sheets; individual-level dietary intake with 24-h recalls, Food Frequency Questionnaires, and/or food records; anthropometry; and biomarkers such as blood levels of iron and other micronutrients (6). However, the only method currently available to directly assess household FS is through experience-based scales, almost all of which are derived from the USHFSSM (6, 22). All the methods have strengths and weaknesses related to specificity, ease of application, data collection speed, cost, and measurement errors, they complement each other, and the choice of method(s) depends on the question(s) being asked (22). For example, a comprehensive assessment of the nutritional status of individuals requires evaluation of their food consumption patterns and FI status as well as examining biochemical, clinical, and anthropometric indices of their nutritional status (11).

Given the rapid dissemination and utilization of experience-based scales globally, the following subsection focuses on them.

The origin of experience-based scales dates back to the 1980s when ethnographic research conducted in upstate New York with people who had experienced hunger and FI suggested that FI could be understood as a stepwise process that starts with household members worrying about food running out followed by sacrificing dietary quality and eventually calories are first reduced among adults and last among children living in the household (6). Subsequently, FS experience-based scales were developed by researchers to capture this sequence of events as reported by a household informant. The strong validity of the scale provided a strong impetus for the US Government to bring together a group of experts to develop what became the USHFSSM, which was heavily influenced by the Radimer/Cornell Hunger scale (23) and the Community Childhood Hunger Identification Project (CCHIP) scale (5, 24, 25). As a result, the USHFSSM has been incorporated since 1995 in the US Census Bureau Continuous Population Survey (CPS) (5) and became incorporated in nationally representative surveys such as the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) (25) (Table 1).

The specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART) properties of the indicators derived from the USHFSSM led to the global dissemination, adaptation, and validation of the USHFSSM across world regions (26). In Latin America, the experience of the Brazilian Food Insecurity Scale (EBIA) (27, 28), a scale from Colombia (9), and the Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) (29) led to the development of the Latin American Food Security Scale (ELCSA) in strong partnership with FAO’s Latin American regional office in Chile (9) (Table 2).

ELCSA was subsequently adopted in additional countries, including Mexico and Guatemala, and it eventually provided the impetus for the development of the Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FIES) that is being used by FAO to track the Sustainable Development Goal 2.1.2 (10) (Table 3).

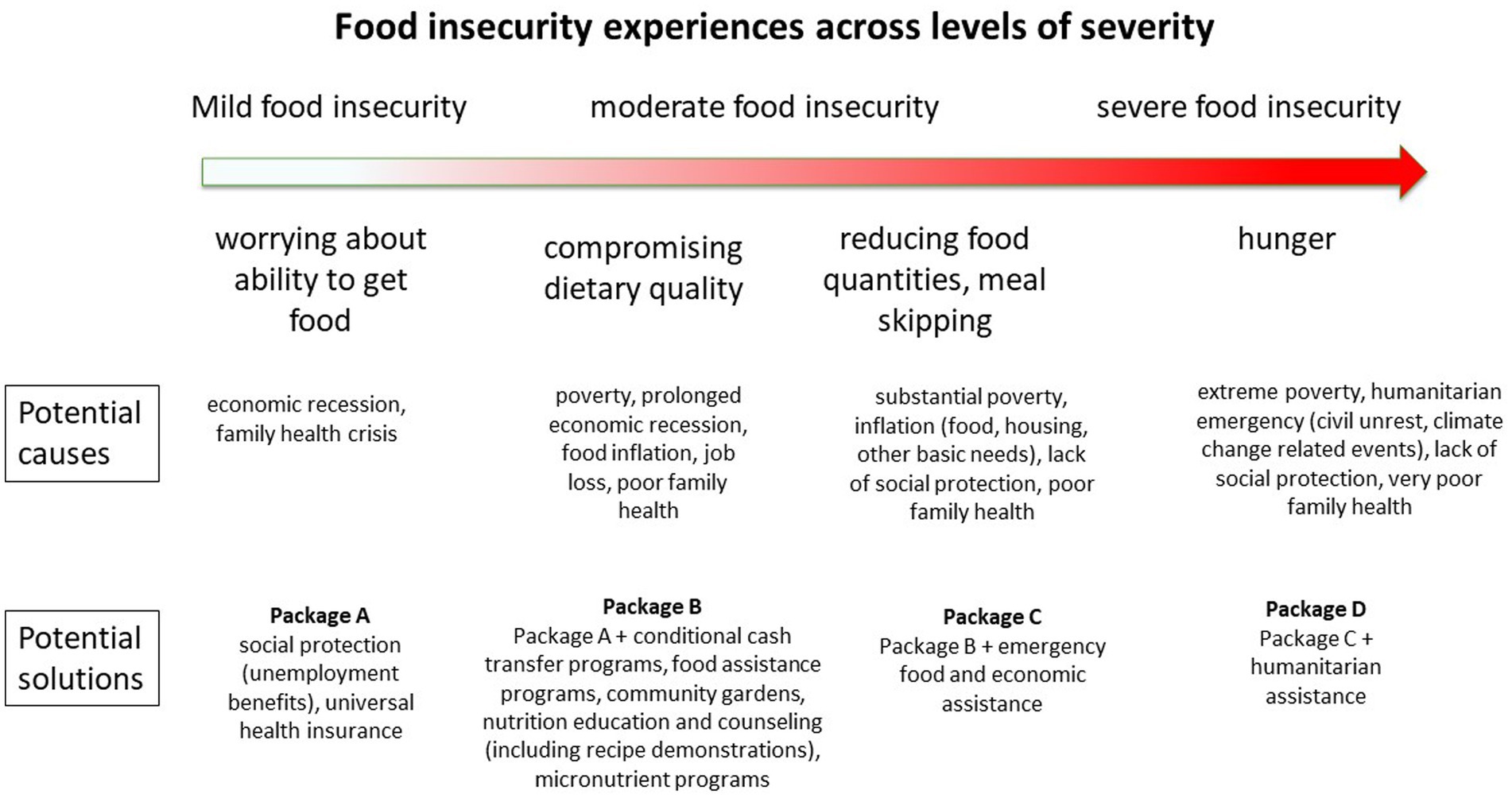

FS experience scales yield an additive score that allows households to be classified according to their level of severity of FI (mild, moderate, and severe), which has allowed for a better understanding of how to design and target FS policies and programs (6). This is because different levels of severity of FI represent different issues ranging from psycho-emotional stress to poor dietary quality all the way to excessive hunger, which requires different solutions (30) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Food insecurity experiences across levels of severity. Potential causes and solutions. Prepared by the author.

FS experience scales have allowed countries, regions, and the world to have better estimates of the burden of FI in the world. Based on FIES, in 2022, 29.6% of the global population, or 2.4 billion people, were moderately or severely FI (31). This meant that there were 391 million more people experiencing moderate or severe FI in 2022 than in 2019, before the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic (31). Furthermore, significant inequities existed based on the economic development of countries, the area of residence (rural vs. peri-urban vs. urban), and sex (female vs. male) (31).

FS experience scales have allowed researchers to better understand the links between FI and (i) the triple burden of malnutrition (undernutrition, obesity, and climate change) (32); (ii) infectious diseases including COVID-19, and common childhood communicable diseases in low- and middle-income countries; (iii) poor mental health across the life course; and (iv) poor early childhood development; (v) and poor medication adherence to treatments (1, 7, 30–39).

Furthermore, from a policy and programmatic perspective, FS experience scales have been useful for supporting equitable social policy investments (30, 31) across countries and for holding governments accountable when FI rates increase, as recently shown in Brazil, and the number of people affected by severe FI increased from 10 million to 30 million between 2018 and 2022 (40, 41). They have also been used to assess the impact of specific programs, including the SNAP programs in the US (26) and conditional cash transfer programs in Mexico (42) and Brazil (40).

The profound link between water and FI in a highly unstable world highlighted the need to consider the use of water insecurity experience scales such as the Household Water Insecurity Experiences (HWISE) alongside the FI scales (15). The 12-item HWISE scale yields an additive score that, combined with a pre-established cutoff point, allows households to be categorized as water-secure or insecure (43) (Table 4). HWISE assesses the frequency in the previous 4 weeks that anyone in the household experienced any of 12 negative emotions (e.g., worry, anger, and shame), disruptions in daily life (e.g., inability to wash clothes, hands, or take a bath), or even unsatisfied thirst due to water insecurity. Research using HWISE has shown that WI is strongly and consistently associated with FI all over the world (15, 44), as well as with physical and mental health outcomes (45–48). Similar to food, access to safe water is a human right recognized by the UN charter since 2010 (15, 43), and it is important to track it as part of the SDGs with an experience scale as it is done for FS (45).

Inspired by the experience with EBIA, Brazil recently applied the HWISE in a nationally representative sample to document the prevalence of WI during the COVID-19 pandemic and how strongly it relates to FI (41). Findings showed that 12% of households experienced WI in Brazil and that among those with WI, 42% experienced severe FI (vs. 12.1% in water-secure households) (43). Mexico has now also included HWISE and a water intermittency scale in nationally representative surveys. The application of HWISE in the National Health and Nutrition Survey (ENSANUT)-2021 demonstrated that HWISE has strong psychometric and predictive validity in the Mexican context (49), and its application through another nationally representative public opinion poll showed that 32% of Mexican households experienced water insecurity and that 68% of households experiencing severe FI were also experiencing WI (vs. 17% in FS households) (50). Furthermore, the application of a water intermittency scale in ENSANUT-2022 found that only 31.5% of Mexican households had water 7 days per week, and of these, only 17.4% did not experience water scarcity in the previous 12 months (51). As expected, water intermittency was more common in the poorest region of Mexico and among the poorest families, confirming that the distribution of WI follows the same social, economic, and demographic inequity patterns as FI.

There are indeed key lessons learned that show how cross-border collaborations have advanced and can continue advancing FI solutions across borders and world regions.

The strong global consensus on the definition of FI and the development of sound conceptual frameworks explaining its determinants at multiple levels and how, together with other SDOH links with nutrition security, allowed for the development of FI measurement approaches that have helped understand the causes, consequences, and potential solution to FI across and within countries (1, 7, 9, 10, 26).

The capacity of countries, regions, and the world to track FI with SMART monitoring and surveillance systems on a continuous basis has been greatly facilitated by the dissemination, adaptation, and validation of the USHFSSM (1, 7, 9, 10, 26). In the US, this scale has been used through the CPS Food Security Supplement, NHANES, the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), the Early Childhood Longitudinal Survey (ECLS), and other monitoring and surveillance systems across sectors. Latin American countries have included scales derived from the USHFSSM, such as EBIA (28) and ELCSA (9), as part of the countries’ national health and nutrition surveys, household income expenditure surveys, public opinion polls, and state and local monitoring systems. At a global level, FIES is used to track SDG 2.1.2, and in fact, FIES was instrumental in the addition of this target to the SDGs. As previously mentioned in this article, all the methods for assessing FI complement each other. Hence, it is encouraging that comprehensive multi-methods monitoring systems have also been developed, such as the food systems dashboard (52) and a low-burden tool for collecting valid, comparable food group consumption data through the “What the World Eats” initiative (53, 54).

FI experience scales have been shown to be helpful for food and nutrition security policies and program designs, including program targeting and evaluation. A robust body of evidence confirms that FI experience scales yield SMART indicators that can help improve FS governance across countries and regions (17, 26, 40, 55).

A clear and concise global definition of FI and corresponding frameworks are in place. Countries such as Brazil have strengthened the definition of food and nutrition security by incorporating human rights and the sustainability dimension, which they have clearly operationalized through the country’s progressive food and nutrition security policies and dietary guidelines (21). There are different methods for directly or indirectly assessing FI. The best method(s) of choice need to be selected based on questions asked, resources, and time frames available. Experience-based FI measures disseminated from the United States to the rest of the world in the early 2000s became a game changer for advancing FI research, policy, and program evaluation. The success of experience-based FI scales is informing the dissemination, adaptation, and validation of WI scales globally. The rich lessons learned across countries on how to advance policy and program design and evaluation through improved FS conceptualization and measurement should be systematically shared through networks of researchers and practitioners such as the recently established Water Insecurity Experiences-Latin America and the Caribbean (WISE-LAC) Network (56).

RP-E: Conceptualization, Investigation, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The author received funding support from the NIH Fogarty International Center. This work was also supported by the Cooperative Agreement Number 5 U48DP006380–02-00 funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Prevention Research Center Program (PI. Rafael Pérez-Escamilla). The funders did not participate in the development of this manuscript. The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the author and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Centers for Disease Control, the Department of Health and Human, or the NIH Fogarty International Center.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Pérez-Escamilla, R. Food security and the 2015-2030 sustainable development goals: from human to planetary health: perspectives and opinions. Curr Dev Nutr. (2017) 1:e000513. doi: 10.3945/cdn.117.000513

2. Poblacion, A, Ettinger de Cuba, S, and Cook, JT. For 25 years, food security has included a nutrition domain: is a new measure of nutrition security needed? J Acad Nutr Diet. (2022) 122:1837–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2022.04.009

3. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Report of the world food summit: 13–17 1996. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; (1996). Available at: www.fao.org/docrep/003/w3548e/w3548e00.htm. (Accessed November 5, 2023).

4. United Nations Committee on World Food Security. Available at https://www.fao.org/cfs/en/ (Accessed November 5, 2023).

5. Bickel, G, Nord, M, Price, C, Hamilton, W, and Cook, J. Guide to measuring household food security, revised. USDA Food and Nutrition Service, Alexandria, VA (2000). Available at: https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/FSGuide.pdf (Accessed November 5, 2023).

6. Pérez-Escamilla, R, and Segall-Corrêa, AM. Food insecurity measurement and indicators. Revista de Nutrição. (2008) 21:15s–26s. doi: 10.1590/S1415-52732008000700003

7. Pérez-Escamilla, R. Food insecurity in children: impact on physical, psychoemotional, and social development In: K. Tucker editor. Modern nutrition in health and disease. USA: Jones & Bartlett (In Press).

8. Radimer, KL, Olson, CM, and Campbell, CC. Development of indicators to assess hunger. J Nutr. (1990) 120:1544–8. doi: 10.1093/jn/120.suppl_11.1544

9. Comité Científico de la ELCSA (2012). Escala Latinoamericana Y Caribeña De Seguridad Alimentaria (ELCSA): Manual De Uso Y Aplicaciones. FAO, Santiago, Chile Available at: http://wwwfaoorg/3/i3065s/i3065spdf (Accessed November 5, 2023)

10. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). The food insecurity experience scale: developing a global standard for monitoring hunger worldwide. Technical paper. FAO, Rome, Italy. (2013) Available at: https://www.fao.org/3/as583e/as583e.pdf Accessed November 5, 2023

11. Anderson, SA. Core indicators of nutritional state for difficult-to-sample populations. J Nutr. (1990) 120:1559–600. doi: 10.1093/jn/120.suppl_11.1555

12. Smith, L. Keynote paper: the use of household expenditure surveys for the assessment of food insecurity. In FAO. Measurement and assessment of food deprivation and undernutrition. In: Proceeding of international scientific symposium, Rome (2002). 26 (pp. 26–28). Available at: https://www.fao.org/3/Y4249e/y4249e08.htm (Accessed November 5, 2023)

13. Frankenberger, T. R., Frankel, L., Ross, S., Burke, M., Cardenas, C., Clark, D., et al. (1997). Household livelihood security: a unifying conceptual framework for CARE programs. In Proceedings of the USAID workshop on performance measurement for food security, 11–12, (1995), Arlington, VA. Washington, DC, United States Agency for International Development

14. UNICEF (United Nations Children’s Fund). The state of the world’s children 1998. New York: Oxford University Press (1998).

15. Young, SL, Frongillo, EA, Jamaluddine, Z, Melgar-Quiñonez, H, Pérez-Escamilla, R, Ringler, C, et al. Perspective: the importance of water security for ensuring food security, good nutrition, and well-being. Adv Nutr. (2021) 12:1058–73. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmab003

16. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Glossary on right to food. Rome: FAO. (2009). Available at: https://www.fao.org/3/as994t/as994t.pdf (Accessed November 5, 2023)

17. Government of Brasil. Lei no 11.346, de 15 de setembro de 2006. (2006) Cria o Sistema Nacional de Segurança Alimentar e Nutricional—SISAN com vistas em assegurar o direito humano à alimentação e dá outras providências. Diário Oficial da União.

18. Swinburn, B, Sacks, G, Vandevijvere, S, Kumanyika, S, Lobstein, T, Neal, B, et al. INFORMAS (international network for food and obesity/non-communicable diseases research, monitoring, and action support): overview and fundamental principles. Obes Rev. (2013) 14:1–12. doi: 10.1111/obr.12087

19. Scrinis, G. Nutritionism: The science and politics of dietary advice. 1st ed. Londres: Routledge (2013).

20. Monteiro, CA, Cannon, G, Levy, R, Moubarac, JC, Jaime, P, Martins, AP, et al. NOVA. The star shines bright. World Nutr. (2016) 7:28–38.

21. Brazil. Ministry of Health of Brazil. Secretariat of health care. Primary health care department. Dietary guidelines for the Brazilian population / Ministry of Health of Brazil, secretariat of health care, primary health care department. Brasília: Ministry of Health of Brazil (2015) Available at: https://www.fao.org/nutrition/education/food-based-dietary-guidelines/regions/countries/brazil/en/.

22. Pérez-Escamilla, R, Gubert, MB, Rogers, B, and Hromi-Fiedler, A. Food security measurement and governance: assessment of the usefulness of diverse food insecurity indicators for policy makers. Global Food Security. (2017) 14:96–104. doi: 10.1016/j.gfs.2017.06.003

23. Kendall, A, Olson, CM, and Frongillo, EA. Validation of the Radimer/Cornell measures of hunger and food insecurity. J Nutr. (1995) 125:2793–801. doi: 10.1093/jn/125.11.2793

24. Murphy, JM, Wehler, CA, Pagano, ME, Little, M, Kleinman, RE, and Jellinek, MS. Relationship between hunger and psychosocial functioning in low-income American children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (1998) 37:163–70. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199802000-00008

25. Wunderlich, GS, and Norwood, JK. (Eds). History of the development of food insecurity and hunger measures. In: Food insecurity and hunger in the United States: An assessment of the measure. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (2006). 23–40.

26. Pérez-Escamilla, R. Can experience-based household food security scales help improve food security governance? Glob Food Sec. (2012) 1:120–5. doi: 10.1016/j.gfs.2012.10.006

27. Pérez-Escamilla, R, Segall-Corrêa, AM, Kurdian Maranha, L, Sampaio Md Mde, F, Marín-León, L, and Panigassi, G. An adapted version of the U.S. Department of Agriculture food insecurity module is a valid tool for assessing household food insecurity in Campinas. Brazil J Nutr. (2004) 134:1923–8. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.8.1923

28. Segall, AM, Marin-Leon, L, and Perez-Escamilla, R. Escala Brasileira de Medida da inseguranca Alimentar (EBIA): Validacão, Usos e Importancia para as Politicas Publicas. In: Fome Zero: Uma historia Brasileiria. 3. Brasilia: Ministerio do Desenvolvimento Social e Combate a Fome. (2010) pp. 26–43. Available at: https://www.mds.gov.br/webarquivos/publicacao/Fome%20Zero%20Vol3.pdf (Accessed November 7, 2023).

29. Coates, J, Swindale, A, and Bilinsky, P. Household food insecurity access scale (HFIAS) for measurement of household food access: Indicator guide (v. 3). Washington, D.C.: FHI 360/FANTA. (2007). Available at: https://www.fantaproject.org/sites/default/files/resources/HFIAS_ENG_v3_Aug07.pdf (Accessed November 7, 2023)

30. Pérez-Escamilla, R, Vilar-Compte, M, and Gaitán-Rossi, P. Why identifying households by degree of food insecurity matters for policymaking. Glob Food Sec. (2020) 26:100459. doi: 10.1016/j.gfs.2020.100459

31. FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO. The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2023 urbanization, agrifood systems transformation and healthy diets across the rural–urban continuum. Rome: FAO. (2023)

32. Swinburn, BA, Kraak, VI, Allender, S, Atkins, VJ, Baker, PI, Bogard, JR, et al. The global Syndemic of obesity, undernutrition, and climate change: the lancet commission report. Lancet. (2019) 393:791–846. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32822-8

33. Perez-Escamilla, R., and Pinheiro de Toledo Vianna, R., 2012. Food insecurity and the behavioral and intellectual development of children: a review of the evidence. J Appl Res Child Inform Pol Child Risk. (2012) 3:9. Available at https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/childrenatrisk/vol3/iss1/9/ (Accessed November 7, 2023)

34. Gundersen, C, and Ziliak, JP. Food insecurity and health outcomes. Health Aff (Millwood). (2015) 34:1830–9. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0645

35. Fang, D, Thomsen, MR, and Nayga, RM Jr. The association between food insecurity and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Public Health. (2021) 21:607. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10631-0

36. Jones, AD. Food insecurity and mental health status: a global analysis of 149 countries. Am J Prev Med. (2017) 53:264–73. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.04.008

37. Young, S, Wheeler, AC, McCoy, SI, and Weiser, SD. A review of the role of food insecurity in adherence to care and treatment among adult and pediatric populations living with HIV and AIDS. AIDS Behav. (2014) 18 Suppl 5:S505–15. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0547-4

38. Thomas, MMC, Miller, DP, and Morrissey, TW. Food insecurity and child health. Pediatrics. (2019) 144:e20190397. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0397

39. Rosen, F, Settel, L, Irvine, F, Koselka, EPD, Miller, JD, and Young, SL. Associations between food insecurity and child and parental physical, nutritional, psychosocial and economic well-being globally during the first 1000 days: a scoping review. Matern Child Nutr. (2023) 20:e13574. doi: 10.1111/mcn.13574

40. Salles-Costa, R, Ferreira, AA, Mattos, RA, Reichenheim, ME, Pérez-Escamilla, R, Bem-Lignani, J, et al. National trends and disparities in severe food insecurity in Brazil between 2004 and 2018. Curr Dev Nutr. (2022) 6:nzac034. doi: 10.1093/cdn/nzac034

41. Rede PENSSAN. II Inquérito Nacional sobre Insegurança Alimentar no Contexto da Pandemia da COVID-19 no Brasil (2022). Brazil. Available at: https://olheparaafome.com.br/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Relatorio-II-VIGISAN-2022.pdf (Accessed November 12, 2023).

42. Saldivar-Frausto, M, Unar-Munguía, M, Méndez-Gómez-Humarán, I, Rodríguez-Ramírez, S, and Shamah-Levy, T. Effect of a conditional cash transference program on food insecurity in Mexican households: 2012-2016. Public Health Nutr. (2022) 25:1084–93. doi: 10.1017/S1368980021003918

43. Young, SL, Bethancourt, HJ, Cafiero, C, Gaitán-Rossi, P, Koo-Oshima, S, McDonnell, R, et al. Acknowledging, measuring and acting on the importance of water for food and nutrition. Nature Water. (2023) 1:825–8. doi: 10.1038/s44221-023-00146-w

44. Young, SL, Boateng, GO, Jamaluddine, Z, Miller, JD, Frongillo, EA, Neilands, TB, et al. The household water InSecurity experiences (HWISE) scale: development and validation of a household water insecurity measure for low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob Health. (2019) 4:e001750. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001750

45. Young, SL. The measurement of water access and use is key for more effective food and nutrition policy. Food Policy. (2021) 104:102138. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2021.102138

46. Jepson, WE, Stoler, J, Baek, J, Morán Martínez, J, Uribe Salas, FJ, and Carrillo, G. Cross-sectional study to measure household water insecurity and its health outcomes in urban Mexico. BMJ Open. (2021) 11:e040825. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040825

47. Boateng, GO, Workman, CL, Miller, JD, Onono, M, Neilands, TB, and Young, SL. The syndemic effects of food insecurity, water insecurity, and HIV on depressive symptomatology among Kenyan women. Soc Sci Med. (2022) 295:113043. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113043

48. Mundo-Rosas, V, Muñoz-Espinosa, A, Hernández-Palafox, C, Vizuet-Vega, NI, Humarán, IM, Shamah-Levy, T, et al. Asociación entre inseguridad del agua y presencia de sintomatología depresiva en población mexicana de 20 años o más. Salud Publica Mex. (2023) 65:620–8. doi: 10.21149/15068

49. Shamah-Levy, T, Mundo-Rosas, V, Muñoz-Espinosa, A, Gómez-Humarán, IM, Pérez-Escamilla, R, Melgar-Quiñones, H, et al. Viabilidad de una escala de experiencias de inseguridad del agua en hogares mexicanos. Salud Pública de México. (2023) 65:219–26. doi: 10.21149/14424

50. Gaitán-Rossi, P, Teruel Belismelis, G, and Parás García, P, Vilar-Compte M, Young SL, Pérez- Escamiíla R. Agua y alimentos. NEXOS. (2023). Available at: https://www.nexos.com.mx/?p=72225. (Accessed November 12, 2023).

51. Figueroa, JL, Rodríguez-Atristain, A, Cole, F, Mundo-Rosas, V, Muñoz-Espinosa, A, Figueroa-Morales, JC, et al. ¿Agua para todos? La intermitencia en el suministro de agua en los hogares en México. Salud Publica Mex. (2023) 65:s181–8. doi: 10.21149/14783

52. Fanzo, J, Haddad, L, McLaren, R, Marshall, Q, Davis, C, Herforth, A, et al. The food systems dashboard is a new tool to inform better food policy. Nature Food. (2020) 1:243–6. doi: 10.1038/s43016-020-0077-y

53. Global Diet Quality Project. Measuring what the world eats: insights from a new approach. Geneva: global Alliance for improved nutrition (GAIN), Boston, MA: Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Department of Global Health and Population. (2022).

54. Global Diet Quality Project. Enabling diet quality monitoring globally with tools and data. Geneva: Gallup, global Alliance for improved nutrition (GAIN), Boston, MA: Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Department of Global Health and Population Available at: https://www.dietquality.org/ (Accessed November 12, 2023).

55. Perez-Escamilla, A, Sales-Costa, R, and Segall-Correa, AM. Food insecurity experience-based scales and food security governance: A case study from Brazil Glob Food Sec. (In Press).

56. Melgar-Quiñonez, H, Gaitán-Rossi, P, Pérez-Escamilla, R, Shamah-Levy, T, Teruel-Belismelis, G, and Young, SL. The water insecurity experiences-Latin America, the Caribbean (WISE-LAC) network. A declaration on the value of experiential measures of food and water insecurity to improve science and policies in Latin America and the Caribbean. Int J Equity Health. (2023) 22:184. doi: 10.1186/s12939-023-01956-w

Keywords: food security, nutrition policy, dietary quality, measurement, nutrition security, food access

Citation: Pérez-Escamilla R (2024) Food and nutrition security definitions, constructs, frameworks, measurements, and applications: global lessons. Front. Public Health. 12:1340149. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1340149

Received: 17 November 2023; Accepted: 19 February 2024;

Published: 14 March 2024.

Edited by:

Juan E. Andrade Laborde, University of Florida, United StatesReviewed by:

Luana Lara Rocha, Federal University of Minas Gerais, BrazilCopyright © 2024 Pérez-Escamilla. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rafael Pérez-Escamilla, cmFmYWVsLnBlcmV6LWVzY2FtaWxsYUB5YWxlLmVkdQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.