- 1Section of Allergy and Immunology, Department of Dermatology, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, United States

- 2Division of Plastic Surgery, Department of Surgery, Penn State Health, Hershey, PA, United States

- 3Department of Nursing, College of Medicine, Pennsylvania State University, Penn State Health, Hershey, PA, United States

Background: Patients can demonstrate prejudice and bias toward minoritized physicians in a destructive dynamic identified as PPtP (Patient Prejudice toward Providers). These interactions have a negative impact on the physical and mental well-being of both those who are targeted and those who witness such behaviors.

Study purpose: The purpose of this study was to explore the PPtP experiences of attending physicians who identify as a minority based on race, ethnicity, citizenship status, or faith preference.

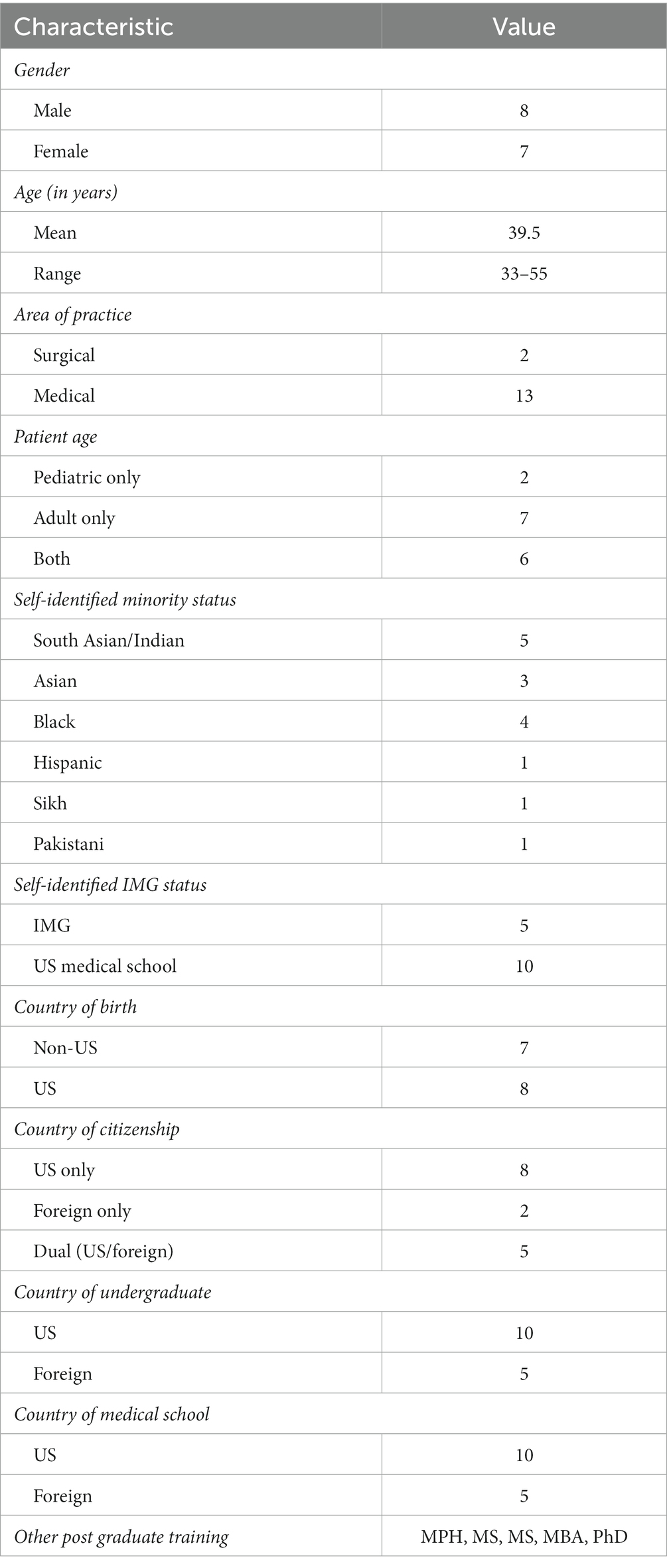

Methods: Qualitative methodology was used to collect data using in-depth interviews. 15 attending physicians (8 male, 7 female, aged 33–55 years) who identified as minorities based on ethnicity, citizenship status, or faith practices were interviewed individually. Interviews were conducted using a guide validated in previous studies and content analysis was performed by two trained researchers to identify themes.

Results: Five themes were identified: A Continuum of Offenses, Professional Growth through Adversity, Organizational Issues, Role of Colleagues, and Consequences for Provision of Care. Findings suggest that although attending physicians learned to cope with PPtP, the experience of being treated with bias negatively impacted their well-being and work performance. Attending physicians also felt that white majority medical students sometimes treated them with prejudice but expressed a commitment to protecting vulnerable trainees from PPtP.

Conclusion: The experience of PPtP occurs consistently throughout a career in medicine, often beginning in the years of training and persisting into the phase of attending status. This makes it imperative to include strategies that address PPtP in order to successfully recruit and retain minoritized physicians.

1 Introduction

Racism in medicine is a topic of increasing concern. Over the past decade, many studies and reports have documented bias and prejudice directed toward minoritized patients (1) on both an institutional and individual basis (2). Minority patients have been found to score below average on indicative health outcome measures, receive less intensive care for common diseases and mental health, experience less stringent pain management, undergo more invasive procedures for the same conditions, and qualify for fewer organ transplants, among many other disparities (3–10). Educational and clinical interventions to address and mitigate these negative outcomes are being evaluated and implemented (11).

The reverse situation, in which patients discriminate against their physicians or nurses of minority status (race, ethnicity, citizenship status, or faith preference) is less well understood and addressed. A landmark paper by Paul-Emile et al. demonstrates that this inverse scenario is similarly exacerbated by our limited understanding and recognition of it (12). Early examination of this phenomenon compounds the already known difficulties faced by minority physicians, who are promoted at lower rates than their non-minority counterparts, awarded less grant money, and afforded a lower income (13–18). Overt and subtle forms of discrimination can occur throughout the careers of physicians, beginning in medical school and persisting into residency. Behaviors such as disparaging comments, undermining capacity, ridicule, and refusing care are examples of bias manifested toward healthcare providers (19–21).

These negative interactions between patients and providers can have many destructive downstream effects (22). Research on “difficult” patients, or patients who use physically or psychologically violent behaviors toward providers documents that such interactions cause emotional and moral distress, burnout, poor performance, and job dissatisfaction (21, 23–27). Ultimately, patients themselves are affected negatively as the quality of the patient-doctor relationship is known to influence health outcomes (28).

Concerns about an inclusive work environment can affect the recruitment of minoritized physicians, specifically at medical centers in more rural and non-diverse areas. The lack of a critical mass of minority faculty, the absence of necessary programmatic efforts, and senior leadership without diversity can influence whether a minority physician candidate accepts a position (29). Retention is also a critical—and costly—step in maintaining a diverse workforce since onboarding a physician can take up to $250,000 until they reach full clinical potential (30). Many employees who leave an organization within the first 6 months do so because of the relational environment rather than the actual work demands (31).

Maintaining a work environment within which minoritized physicians can securely and safely work for long periods while providing optimal care for patients requires organizational commitment to addressing PPtP (32). Efforts to diversify medicine within specialties have been implemented on national and individual organizational levels with varying success. Effective initiatives have focused on recruitment measures, while others seek to balance the disparate incomes, promotions, and grant awards that negatively affect minority physicians (33–35). Few, however, address PPtP, which can have an equally profound effect on the well-being and retention of minority physicians.

We have previously delineated the PPtP experiences of resident physicians and nurses (unpublished data) and seek to complement that research by studying the attending physician community. Progress in retaining a diverse workforce will provide optimal care for a progressively more diverse patient population while affording attending physicians a safe, fruitful, and healthy work environment.

1.1 Study aim

The purpose of this study was to examine the experiences of attending physicians who have been subjected to PPtP.

2 Methods

The consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) was used to ensure objectivity and fidelity of methods used to conduct this study (36). The research team consisted of one faculty researcher with expertise in qualitative research (CD), one physician researcher who immigrated to the US after medical school (DAA), and four medical students and one resident (SM) from diverse backgrounds.

This study was conducted and completed while all members of the research team where at Penn State. Once IRB approval from the Penn State IRB to conduct the study was received, an invitation to participate was disseminated through emails to Department chairs at Penn State, online via the Junior Faculty Development Program at Penn State and posted on announcement boards throughout the hospital as well as word-of-mouth. All attending physicians at Penn State Health meeting the inclusion criteria of self-identification as a minority based on ethnicity, citizenship status, country of medical school, or faith practices were invited to contact the investigator via email if they were interested in participating.

This study was exempt from after potential interviewees received a summary explanation of the research, a research assistant arranged to meet with them at a convenient time and place that ensured privacy on the end of the interviewer. Arranging for a quiet and private place was encouraged also for the interviewee when scheduling the interview. All interviews were conducted via Zoom using the PPtP Interview Guide validated in previous studies (see Supplementary material). Where appropriate, prompts were used to elaborate on the responses. Interviews lasted 60 min on average. Each physician was interviewed once, with no repeat interviews offered. Four medical students functioned as paid research assistants who conducted all interviews. Each had received a four-hour training on qualitative methods and successfully completed a pilot interview with a physician of minority background under the supervision of the investigators. Periodic audits of completed interviews were conducted by the investigators to assure continued fidelity.

The first 15 participants who expressed interest completed interviews, with saturation being reached after the 14th interview, with an additional interview conducted for veracity (Data saturation was defined as the point when additional interviews did not render additional information). Our sample size is within the reported range of a recent meta-analysis describing that within 9–17 interviews (mean12-13), most themes are captured (37).

Interviews were recorded and stored in a secure file (stored in Penn State box as apple audio files) prior to transcription. The transcription was performed by a paid transcriptionist within the Penn State system. The audio files were de-identified prior to transcription. After transcribing and cleaning, transcripts were reviewed independently by the investigators. With an iterative process that compared each transcript across and within interviewees, recurring words, phrases, and concepts were noted. The investigators (CD and DAA) then met to compare results and merge them into themes. The Kappa coefficient of agreement between the researchers was 0.88. An independent reviewer (SM) examined the PPtP Interview Guide questions and content relevant to PPtP, then compared the themes and exemplar statements for consistency and validity. After data extraction and theme identification, the investigators reviewed the interviews to identify sample quotes.

3 Results

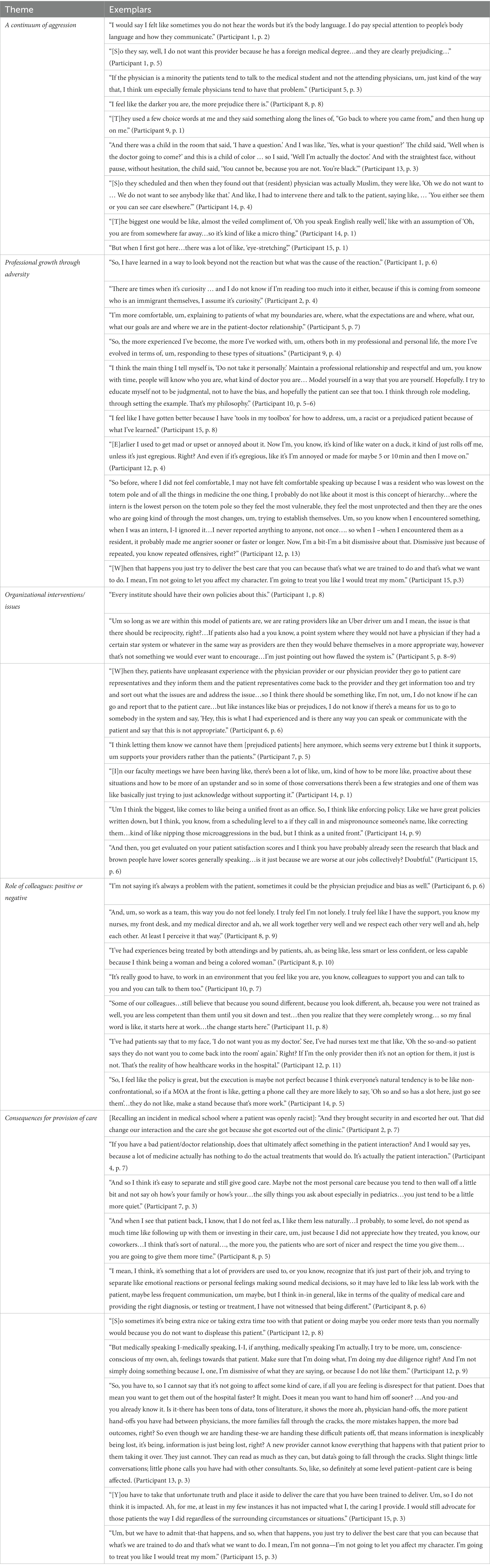

The 15 interviewees (8 male, 7 female, aged 33–55 years) represented a diverse group in relation to ethnicity/immigration status, age, gender, and type of practice. All were employed by the same academic healthcare system, but some of the experiences they described occurred at other institutions and/or during training. For demographics, see Table 1. Exemplar statements from the transcripts are contained in Table 2. Five themes were identified based on the analysis of the researchers. A Continuum of Offenses, Professional Growth through Adversity, Organizational Issues, Role of Colleagues, and Consequences for Provision of Care.

3.1 Continuum of offenses

Situations in which the provider was the target of some form of PPtP from patients and their families were described by most interviewees, with the emotional impact of these interactions differing. For example, remarks about a physician’s ability to speak English happened so frequently that some chose to laugh it off. One told a patient: “If I could not speak [English] well, it would be a condemnation for the American public school system, since that’s where I learned” (Participant 2, p. 5).

At other times, the reaction to the aggression went deeper, especially when physicians felt they were viewed as “less than” their non-minoritized peers. Physicians reported that refusal of care from a patient felt specifically hurtful. In one situation where a parent was doubting the physician’s capabilities because of ethnicity, the physician said,

I had to call him out on it, and say like, “Sir…what are your concerns?” He’s like, “I just, you know, I do not appreciate that foreigners are like, doing this.” And I was like, “Well you know I grew up in [US state], like, you know, I do not really consider myself a foreigner.” (Participant 14, p. 2–3).

3.2 Professional growth through adversity

There was consensus among interviewees that PPtP happened more frequently in medical school and residency, but by the end of their training, many physicians reflected that part of what they had learned was strategies for how to react. One interviewee explained:

[Y]es, I’ve matured and changed and experienced that, but that coat of armor has built up. The skills of talking with patients ha[ve] built up. The skills of upstanding and by-standing and being an advocate, those skills have developed over the years, so it’s yes, I can take a lot more than I once could…you develop some comfort level but you are not always comfortable, right? It’s like this concept of being comfortable with the uncomfortable, ah, in many instances. (Participant 12, p. 14).

Interviewees reported that after completing their training, there was a feeling of security and confidence in their skills; thus, they felt less personally offended when PPtP occurred. Sometimes this was a deliberate stance and, at others, almost automatic as physicians refined their technological expertise.

The recognition that vulnerability was most evident in the early stages of training was illustrated by one interviewee this way: “[T]he intern is the lowest person on the totem pole so they feel the most vulnerable, they feel the most unprotected and then they are the ones who are going kind of through the most” (Participant 12, p. 14). This led interviewees to feel a special protectiveness toward those who were still trainees, especially if they came from minoritized backgrounds.

3.3 Organizational interventions/issues

While there was agreement that the hospital as an institution and employer held some responsibility for resolving PPtP, physicians recognized that certain parts of their work environment led them to believe there was no easy resolution or remediation. Noting that medicine is increasingly a “consumer-focused” profession, the anonymous power a patient can have over a physician via feedback and evaluations is tremendous and limits corrections, according to interviewees. Often manifested by scores on satisfaction surveys or feedback to administration, this contributed to burnout and anxiety in addition to feelings of rejection. Regardless of the legitimacy of a complaint, once it was entered as a patient comment, the physician perceived a type of “double hit”: bias from the patient during the encounter and later negative consequences from the system because of the low satisfaction score or negative comment. The fallout of organizations failing to take action to address PPtP was significant. Said one physician:

I would say [PPtP] has deeply impacted my job satisfaction. I still love working here…but I think, I do miss, um, having a diverse population…I did not expect to feel that way but it’s also harder to relate to someone who does not appreciate different cultures or different personalities or different backgrounds. (Participant 8, p.9).

Many saw it as their employer’s imperative to create a workplace that welcomed diversity and positively acknowledged attempts by the institution to do so. An interviewee said,

So, if I’m Hospital A and Hospital A needs to be comfortable explaining to people of the community A lives in that we hire and employ people who are quite skilled at providing their care and reassure them that even though the person may look different than them, the standard that we have in place for who cares for the people in our community is unrivaled and because of that, we ask these people to come in and serve and care for people who might be ill. Ask them to respect their service, and this is what respecting their service looks like. And having that be a clear part of the mission, the vision and values of Hospital A. (Participant 13, p. 4).

3.4 Role of colleagues: positive or negative

Although participants were not explicitly asked about prejudice and bias originating from coworkers or other individuals in their work environment, when describing experiences with patients, this influence was frequently commented on. Said one,

[I]t was a nurse who—it was their patient, their name was on the chart to call for questions, they were the senior resident, but the nurse decided to call the junior resident…the junior resident was not black. So, then the junior resident had to call the senior resident to help…. when they asked [the nurse] why they did not call them, they were very quiet…so there was a feeling of bias against calling the senior resident. (Participant 13, p. 1).

The interviewee reported that in this situation, bias against the resident was not addressed because it was difficult to know how to do so. When bias came from team members, there was significant frustration:

Some of our colleagues…still believe that because you sound different, because you look different, ah, because you were not trained as well, you are less competent than them until you sit down and test…then you realize that they were completely wrong… [and] …some of them feel like they have to diminish you to be able to be seen as a good physician. (Participant 11, p. 8).

A supportive work environment was described as a very important factor in dealing with the daily impacts of PPtP; specifically. This often includes colleagues who were understanding and provided safe spaces to discuss experiences. One interviewee commented that: “It’s really good to have, to work in an environment that you feel like you are, you know, colleagues to support you and can talk to you and you can talk to them too” (Participant 10, p. 7). This positive culture within teams was not limited to direct colleagues, as demonstrated in this comment:

I truly feel like I have the support, you know my nurses, my front desk, and my medical director and ah, we all work together very well and we respect each other very well and ah, help each other. At least I perceive it that way. (Participant 8, p. 9).

These physicians reported that the actions of both supervisors (administrators) and colleagues (coworkers) had an influence on the work environment and could contribute to positive evaluations of the interviewee (and therefore bonuses). Direct support from colleagues or supervisors seemed to have a more effective strategy than institutional policies, which were felt to be inconsistently implemented and often ignored.

3.5 Consequences for provision of care

PPtP was shown to impact not only the affected physicians but also had a negative effect on patient care, as evidenced by this comment about a patient who exhibited prejudice toward the physician: “I probably, to some level, do not spend as much time like following up with them or investing in their care” (Participant 7, p. 3). Trained to deliver quality patient care in a compassionate way, providers on the receiving end of PPtP found themselves in an ethically challenging position due to conflict between providing optimal care while simultaneously managing the emotional effect of bias from the patient. Ultimately, they persevered, as demonstrated by this comment:

[W]hen that happens, you just try to deliver the best care that you can because that what’s we are trained to do and that’s what we want to do. I mean, I’m not gonna-I’m not going to let you affect my character. I’m going to treat you like I would treat my mom. (Participant 15, p. 3).

Even though PPtP became a “norm” and interviewees felt like they became used to it, one said: “I think, it’s something that a lot of providers are used to, or you know, recognize that it’s just part of their job, and try to separate emotional reactions or personal feelings making sound medical decisions” (Participant 8, p. 5).

The reported effect on patient care ranged from overcompensation, fractured communication, and less diligent care. Some physicians described practicing medicine with extra caution after a patient addressed them with prejudice. “[S]o sometimes it’s being extra nice or taking extra time too with that patient or doing maybe you order more tests than you normally would because you do not want to displease this patient” (Participant 8, p. 6).

4 Limitations

This study was limited by the use of one institution to recruit participants, although many interviewees drew on experiences at other hospitals. While qualitative methodology limits generalizability, current studies using quantitative measures with a larger population are in progress.

5 Discussion

The PPtP experiences of attending physicians described in this study are consistent with behaviors identified in our previous studies. They include both overt actions such as refusing care or making negative comments as well as covert gestures such as “side-eyeing” or body language. As with our previous work, female residents or physicians felt more targeted, especially when they were mistaken for a nurse or received sexist comments on their appearance (22).

For most interviewees, experience led to role security and the development of specific proactive responses to PPtP. Often, this involved attempting to make meaning of the behaviors in ways that allowed physicians to continue providing care, such as reasoning that the person was ill and not their best self. At other times, this involved giving patients the benefit of the doubt or using standard responses to PPtP (validating their credentials, seeking outside help) so the therapeutic relationship would not be fractured. Others even adopted an attitude of forgiveness, rationalizing that even white physicians could be on the receiving end of unpleasant and rude behavior from individuals who were sick. Additional approaches included setting boundaries, humor, tolerating, and ignoring. Still, the experience of PPtP was coped with at the cost of spontaneity, connection, and professional well-being.

Despite their resilience in responding to PPtP, attending physicians were still concerned about the ethics of such challenging situations, which often required them to provide care for patients who treated them with disrespect and even outright rejection. Also, the impact of such interactions on patient satisfaction scores was worrisome, and negative comments from patients influenced job satisfaction and might ultimately affect promotions or bonuses.

The relatively higher status, self-confidence, and clinical skill that came after the initial phases of training provided not only the ability to respond better for oneself but a feeling of protectiveness towards trainees who found themselves in these situations. However, being cast in the role of educator had a threatening as well as a motiving impact. Teaching students who were “mostly white” caused some to question their abilities, especially when they had an accent or were educated outside the US.

6 Conclusion

Our studies have helped highlight a multitude of problems arising from PPtP in healthcare settings. Some hospital systems have implemented a zero-tolerance policy toward bias and prejudice against members of the healthcare system taking a clear stance. However, these policies are often hard to implement in real life. As one participant said, “Policies do not take away prejudice.” More research on the effectiveness of organizational responses to PPtP as well as larger interdisciplinary and quantitative studies are needed to better address and resolve this destructive dynamic. The multi-institutional intervention study by Kalet et al. (32) offers promise in this area.

Many of the PPtP situations described by our interviewees were microaggressions, meaning bystanders who have never been on the receiving end of these biases may not recognize when they occur or consider them a form of prejudice. The affected provider then can feel not only disrespected but also isolated in their experience. At the same time, bystanders who witness more overt forms of rejection, such as belittling or humiliation, describe a sense of helplessness in reacting appropriately (22). Depending on the status or experience of the bystanders, confronting the patient and immediate response to the situation might be difficult. However, acknowledgment of the situation from non-affected team members has been reported to decrease the feeling of isolation and increase team coherence (38). Open discussion of actual or hypothetical PPtP situations within teams has also been reported to increase the chance of bystanders becoming upstanders in future situations (39).

Discord and disrespect within healthcare teams can lead to miscommunication, increased stress, and ultimately worse patient outcomes (40). As reported in our study, rejection of healthcare team members based on their race, ethnicity, immigration status, or religious affiliation by patients and/or their families can lead to diminished motivation to provide care, a sense of rejection, feelings of being let down by the employer, and difficulties with coworkers—all of which can lead to burnout and turnovers.

There is value in being proactive and persistent. In both basic and graduate medical educational settings, PPtP should be openly discussed before it occurs, not reported when there are problems. Strategies for responding should be shared and individualized. As well, all attending physicians should begin their career with an awareness of what PPtP is, how it impacts both providers and patients, and what responses can be effectively used to react to it. Our interviewees were resilient and creative in addressing their experiences of patient prejudice and bias—now they and others like them should be given a voice to share and empower others with their wisdom.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Penn State Health Review Board and considered exempt STUDY00016826. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The ethics committee/institutional review board waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants' legal guardians/next of kin because the study was considered exempt.

Author contributions

DAA: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CD: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was partially funded by a Junior Faculty Training grant awarded to DAA (2018–2020).

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Jane Frances Aruma, Natasha Sood, Noa Farou and Lindsey Peck.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1304107/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Bailey, ZD, Krieger, N, Agénor, M, Graves, J, Linos, N, and Bassett, MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. (2017) 389:1453–63. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X

2. Klonoff, EA. Disparities in the provision of medical care: an outcome in search of an explanation. J Behav Med. (2009) 32:48–63. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9192-1

3. Trivedi, AN, Zaslavsky, AM, Schneider, EC, and Ayanian, JZ. Relationship between quality of care and racial disparities in Medicare health plans. JAMA. (2006) 296:1998–2004. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.16.1998

4. Nelson, A. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Natl Med Assoc. (2002) 94:666–8.

5. Bhandari, VK, Wang, F, Bindman, AB, and Schillinger, D. Quality of anticoagulation control: do race and language matter? J Health Care Poor Underserved. (2008) 19:41–55. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2008.0002

6. Jha, AK, Fisher, ES, Li, Z, Orav, EJ, and Epstein, AM. Racial trends in the use of major procedures among the elderly. N Engl J Med. (2005) 353:683–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa050672

7. Pletcher, MJ, Kertesz, SG, Kohn, MA, and Gonzales, R. Trends in opioid prescribing by race/ethnicity for patients seeking care in US emergency departments. JAMA. (2008) 299:70–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2007.64

8. Stolzmann, KL, Bautista, LE, Gangnon, RE, McElroy, JA, Becker, BN, and Remington, PL. Trends in kidney transplantation rates and disparities. J Natl Med Assoc. (2007) 99:923–32.

9. Reid, AE, Resnick, M, Chang, Y, Buerstatte, N, and Weissman, JS. Disparity in use of orthotopic liver transplantation among blacks and whites. Liver Transpl. (2004) 10:834–41. doi: 10.1002/lt.20174

10. Hudson, JL, Miller, GE, and Kirby, JB. Explaining racial and ethnic differences in children's use of stimulant medications. Med Care. (2007) 45:1068–75. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31806728fa

11. Hunter, J, Majd, I, Kowalski Dc, M, and Harnett, JE. Interprofessional communication-a call for more education to ensure cultural competency in the context of traditional, complementary, and integrative medicine. Glob Adv Health Med. (2021) 10:21649561211014107. doi: 10.1177/21649561211014107

12. Paul-Emile, K, Smith, AK, Lo, B, and Fernández, A. Dealing with racist patients. N Engl J Med. (2016) 374:708–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1514939

13. Fang, D, Moy, E, Colburn, L, and Hurley, J. Racial and ethnic disparities in faculty promotion in academic medicine. JAMA. (2000) 284:1085–92. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.9.1085

14. Nunez-Smith, M, Curry, LA, Bigby, J, Berg, D, Krumholz, HM, and Bradley, EH. Impact of race on the professional lives of physicians of African descent. Ann Intern Med. (2007) 146:45–51. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-1-200701020-00008

15. Nunez-Smith, M, Ciarleglio, MM, Sandoval-Schaefer, T, Elumn, J, Castillo-Page, L, Peduzzi, P, et al. Institutional variation in the promotion of racial/ethnic minority faculty at US medical schools. Am J Public Health. (2012) 102:852–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300552

16. Ginther, DK, Schaffer, WT, Schnell, J, Masimore, B, Liu, F, Haak, LL, et al. Race, ethnicity, and NIH research awards. Science. (2011) 333:1015–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1196783

17. Ginther, DK. Reflections on race, ethnicity, and NIH research awards. Mol Biol Cell. (2022) 33:ae1. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E21-08-0403

18. Ly, DP, Seabury, SA, and Jena, AB. Differences in incomes of physicians in the United States by race and sex: observational study. BMJ. (2016) 353:i2923. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2923

19. Fnais, N, Soobiah, C, Chen, MH, Lillie, E, Perrier, L, Tashkhandi, M, et al. Harassment and discrimination in medical training: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Med. (2014) 89:817–27. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000200

20. Osseo-Asare, A, Balasuriya, L, Huot, SJ, Keene, D, Berg, D, Nunez-Smith, M, et al. Minority resident Physicians' views on the role of race/ethnicity in their training experiences in the workplace. JAMA Netw Open. (2018) 1:e182723. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.2723

21. de Bourmont, SS, Burra, A, Nouri, SS, El-Farra, N, Mohottige, D, Sloan, C, et al. Resident physician experiences with and responses to biased patients. JAMA Netw Open. (2020) 3:e2021769. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.21769

22. Dellasega, C, Aruma, JF, Sood, N, and Andreae, DA. The impact of patient prejudice on Minoritized female physicians. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:902294. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.902294

23. Jain, SH. The racist patient. Ann Intern Med. (2013) 158:632. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-8-201304160-00010

24. Paul-Emile, K, Critchfield, JM, Wheeler, M, de Bourmont, S, and Fernandez, A. Addressing patient Bias toward health care workers: recommendations for medical centers. Ann Intern Med. (2020) 173:468–73. doi: 10.7326/M20-0176

25. Singh, K, Sivasubramaniam, P, Ghuman, S, and Mir, HR. The dilemma of the racist patient. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). (2015) 44:E477–9.

26. Garran, AM, and Rasmussen, BM. How should organizations respond to racism against health care workers? AMA J Ethics. (2019) 21:E499–504. doi: 10.1001/amajethics.2019.499

27. Shankar, M, Albert, T, Yee, N, and Overland, M. Approaches for residents to address problematic patient behavior: before, during, and after the clinical encounter. J Grad Med Educ. (2019) 11:371–4. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-19-00075.1

28. Isbell, LM, Boudreaux, ED, Chimowitz, H, Liu, G, Cyr, E, and Kimball, E. What do emergency department physicians and nurses feel? A qualitative study of emotions, triggers, regulation strategies, and effects on patient care. BMJ Qual Saf. (2020) 29:1.5–2. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2019-010179

29. Kaplan, SE, Gunn, CM, Kulukulualani, AK, Raj, A, Freund, KM, and Carr, PL. Challenges in recruiting, retaining and promoting racially and ethnically diverse faculty. J Natl Med Assoc. (2018) 110:58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jnma.2017.02.001

30. Stajhudar, T. The high costs of hiring the wrong physician, NEJMCareerCenter.org. Recruiting Physicians Today. (2019) 27. Available at: https://employer.nejmcareercenter.org/rpt/RecruitingPhysiciansToday_NovDec19.pdf

31. Christine Harsh, MHA, Jná Báez, MBA, Faraz Ahmad, MD, Junk, C, and Olayiwola, JN. “Thank you for not letting me crash and burn” the imperative of quality physician onboarding to Foster job satisfaction, strengthen workplace culture, and advance the quadruple aim. JCOM. (2021) 28:57–61. doi: 10.12788/jcom.0039

32. Kalet, A, Libby, AM, Jagsi, R, Brady, K, Chavis-Keeling, D, Pillinger, MH, et al. Mentoring underrepresented minority physician-scientists to success. Acad Med. (2022) 97:497–502. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000004402

33. Alexander, GR, and Johnson, JH. Disruptive demographics: their effects on nursing demand, supply and academic preparation. Nurs Adm Q. (2021) 45:58–64. doi: 10.1097/NAQ.0000000000000449

34. Mcintosh-Clarke, DR, Zeman, MN, Valand, HA, and Tu, RK. Incentivizing physician diversity in radiology. J Am Coll Radiol. (2019) 16:624–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2019.01.003

35. White, MJ, Wyse, RJ, Ware, AD, and Deville, C. Current and historical trends in diversity by race, ethnicity, and sex within the US pathology physician workforce. Am J Clin Pathol. (2020) 154:450–8. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/aqaa139

36. Tong, A, Sainsbury, P, and Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. (2007) 19:349–57. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

37. Hennink, M, and Kaiser, BN. Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: a systematic review of empirical tests. Soc Sci Med. (2022) 292:114523. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114523

38. Simpson, AV, Farr-Wharton, B, and Reddy, P. Cultivating organizational compassion in healthcare. J Manag Organ. (2020) 26:340–54. doi: 10.1017/jmo.2019.54

39. Thompson, N, Carter, M, Crampton, P, Burford, B, Illing, J, and Morrow, G. Workplace bullying in healthcare: a qualitative analysis of bystander experiences. Qual Rep. (2020) 25:3993–4028. doi: 10.46743/2160-3715/2020.3525

Keywords: prejudice and discrimination, retention, workforce, bias, patient outcomes

Citation: Andreae DA, Massand S and Dellasega C (2024) The physician experience of patient to provider prejudice (PPtP). Front. Public Health. 12:1304107. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1304107

Edited by:

Meghna Ranganathan, University of London, United KingdomReviewed by:

Candace S. Brown, University of North Carolina at Charlotte, United StatesKarolien Aelbrecht, Ghent University Hospital, Belgium

Copyright © 2024 Andreae, Massand and Dellasega. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Doerthe A. Andreae, YWRyaWFuYS5hbmRyZWFlQGhzYy51dGFoLmVkdQ==

Doerthe A. Andreae

Doerthe A. Andreae Sameer Massand2

Sameer Massand2 Cheryl Dellasega

Cheryl Dellasega