- 1Early Childhood Education Institute, University of Oklahoma-Tulsa, Tulsa, OK, United States

- 2Department of Human Development and Family Studies, College of Social Science, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, United States

- 3Department of Human Development and Family Studies, College of Human Sciences, Iowa State University, Ames, IA, United States

Given the importance of health to educational outcomes, and education to concurrent and future health, cross-systems approaches, such as the Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child (WSCC) framework, seek to enhance services typically in K-12 settings. A major gap exists in cross-systems links with early care and education serving children birth to age 5. Both pediatric health systems and early family and child support programs, such as Early Head Start (EHS) and Head Start (HS), seek to promote and optimize the health and wellbeing of infants, toddlers, preschoolers, and their families. Despite shared goals, both EHS/HS and pediatric health providers often experience challenges in reaching and serving the children most in need, and in addressing existing disparities and inequities in services. This paper focuses on infant/toddler services because high-quality services in the earliest years yield large and lasting developmental impacts. Stronger partnerships among pedicatric health systems and EHS programs serving infants and toddlers could better facilitate the health and wellbeing of young children and enhance family strengths and resilience through increased, more intentional collaboration. Specific strategies recommended include strengthening training and professional development across service platforms to increase shared knowledge and terminology, increasing access to screening and services, strengthening infrastructure and shared information, enhancing integration of services, acknowledging and disrupting racism, and accessing available funding and resources. Recommendations, including research-based examples, are offered to prompt innovations best fitting community needs and resources.

Introduction

Past research documents bidirectional associations between health and educational outcomes and acknowledges that health conditions, disabilities, and unhealthy behaviors affect educational outcomes (1, 2). A growing body of research illustrates the influence of education on health (3, 4) and suggests the effects of educational programs on health start early and have lasting impacts. Fortunately, these effects are malleable; programs have been shown to produce significant, positive impacts. For example, randomized long-term studies of high-quality early education programs designed for infants, toddlers, and preschoolers show improved health and fewer risky health behaviors at ages 21 (5), 30 and 40 (6, 7). Thus, Chiang et al. (3) observation that despite these overt links, “the health and education sectors have, for the most part, grown, developed, and established their influence independent of each other” (p. 775) is troubling. Even more perplexing, health and education professionals focus on similar issues, often with the same children, in the same neighborhoods, yet work in parallel often with minimal collaboration (3, 8).

Given the important connections between health and educational outcomes, health promotion initiatives have been developed, typically drawing on multiple disciplines and recognizing the role of different systems (e.g., home, school, neighborhood). Building on earlier models, the Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child (WSCC) framework is a health promotion approach advanced by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (8) for integrating health and education in schools (3, 9). The WSCC model comprehensively assesses strengths and needs and highlights common goals of both health and education to prompt adoption of a whole child approach (8).

The WSCC model was designed primarily for K-12 settings. While WSCC descriptions include many community organizations, links to early care and education (ECE) serving children birth to age 5 appear to be missing. Research summarizing the long-term benefits of ECE on later outcomes demonstrates school health promotion programs and ECE share common goals. Additionally, a whole child approach and comprehensive service delivery model are distinguishing features of many ECE programs, including Early Head Start (EHS) and Head Start (HS), federally-funded programs serving children birth to age 5 and their families living in the context of poverty across all U.S. states and territories.

Although EHS/HS strive to deliver comprehensive services and have experienced successes integrating education with health and other services (10), stronger partnerships among pediatric health systems, school health promotion, and ECE could further strengthen services and optimize outcomes. This paper calls for greater collaboration across these systems.

We focus on the youngest children because a growing body of research suggests that ECE programs for infants offer the largest and longest-lasting impacts (6, 11). Likewise, we highlight young children and their families living in poverty because they face multiple stressors known to impede both educational and health outcomes. In response, pediatric care, public health, and comprehensive programs designed for young children seek to address children's myriad needs adopting a prevention framework (8). These systems note challenges in reaching those most in need and successfully addressing existing inequities in service access and receipt. For example, vaccination rates often lag for infants and toddlers among impoverished families without access to insurance (12). Similarly, EHS served just 11% of eligible children in 2021 (13).

We first describe EHS because, although launched in 1995, it is less familiar than its companion program, HS, that has served preschool-aged children since 1965. We then offer strategies to strengthen collaboration across EHS and pediatric health systems.

Early Head Start

EHS provides an array of services to pregnant women and families with children under age 3 living in poverty (14), extending the comprehensive services offered through HS to infants and toddlers. In 2020, EHS and HS together served more than 839,000 children across the US; 30% were under age 3 (15). EHS programs follow the Head Start Program Performance Standards (HSPPS) stipulating provision of high-quality, comprehensive child development services through home visits, childcare, case management, parenting education, health care and referrals, and family support (16, 17). They must also meet Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment (EPSDT) requirements (16). The goal of comprehensive services, an EHS “cornerstone” (18), is to promote the health and wellbeing of children and support families as caregivers (19). Thus, comprehensive EHS services are designed to address the needs of infants, toddlers, and families including facilitating health, mental health, and early intervention (EI) services. See the following website for additional information about EHS: https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/programs/article/about-early-head-start-program.

Theoretical and practical foundations

In ECE, existing models similar to WSCC are used. For example, delivery of comprehensive services across systems is well-aligned with contemporary models of child and family development, including early relational health (ERH). ERH highlights two important considerations. First, wellbeing is defined comprehensively to include children's physical health (e.g., receipt of health care, well-child visits), developmental health (e.g., optimal development across domains), and relational health (e.g., the child's positive relationships with parents/caregivers, teachers) (20). Second, ERH frameworks (21) highlight essential relationships across three, interrelated systems: (1) primary relationships between caregivers and children (e.g., parent-child/teacher-child relationships); (2) secondary relationships among caregivers and service providers (e.g., healthcare providers, social workers, ECE providers); and (3) tertiary relationships among larger systems impacting children's wellbeing, including communication and infrastructure to support coordination among systems (e.g., ECE programs including EHS, primary healthcare, and EI).

ERH, the common framework driving systems thinking across birth to age 5 services, shares similarities with WSCC's systemic approach. ERH, similar to WSCC with older children, provides a framework supporting integration of children's physical, developmental, and mental health needs and services. Practically speaking, ERH models offer the most robust framework for early support/intervention given the strong influence the health of infants and toddlers has across developmental domains (22). Calls to provide integrated services advocated by ERH and WSCC are crucial for the youngest children; while public school systems serve over 91% of children K-Grade 12 (23), U.S. ECE is fragmented with many children and families underserved.

Health, mental health, and early intervention services in EHS

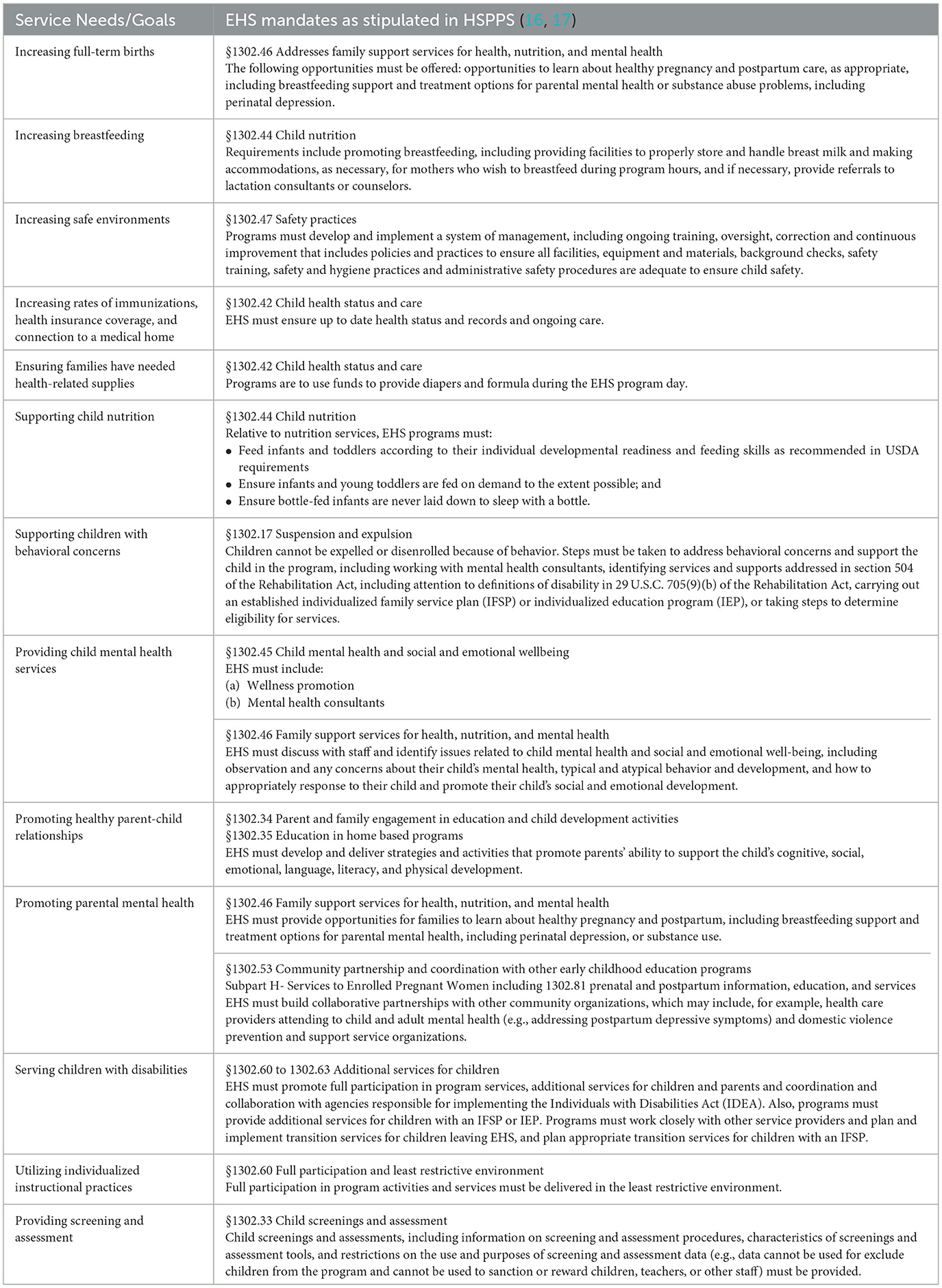

The HSPPS (16) detail requirements for EHS/HS comprehensive services (Table 1 provides details). Expanding collaboration between EHS and health care is well-aligned with EHS and pediatric health goals. Further, growing recognition that racial and economic inequities start well before birth (13) is a clarion call that inequities must be acknowledged and attention focused on creating practices, policies, and systems that achieve equity in service access and receipt. Next, we summarize how EHS addresses health, mental health, and EI service needs as background for discussion on how EHS/HS and pediatric services might expand collaborations.

Health services

Rates of immunizations and insurance coverage are important health indicators that vary across states and sociodemographic groups. EHS programs work successfully with families to increase access with rates of immunization (94% to 96%) and health insurance (95% to 97%) increasing over the 2018–19 HS program year (24). EHS also shows favorable impacts on increased breastfeeding and other health promoting practices (22, 25). These indicators reflect, in part, the resources and care a medical home provides. Unfortunately, most states report only about 50% of parents have a medical home for their infants and toddlers, with rates varying widely by race and ethnicity (13). Participation in EHS/HS boosts rates of connection to medical (95% to 97%) and dental homes (82% to 90%) (24) underscoring the potential to further increase service access and child wellbeing via enhanced EHS-pediatric health collaborations.

Mental health services

One out of every six children, ages 2 to 8, has a diagnosed mental health, behavioral, or developmental disorder (26). Mental health concerns are disproportionately high among children from impoverished contexts, where nearly 20% of children experience a mental, behavioral, and/or developmental disorder (27), and among children from ethnic-racial minorities (28). Unfortunately, access to full mental health services lags behind needs (29). For example, about 78% of children with depression receive treatment but only 54% of children with behavioral disorders receive treatment (30). Among children experiencing poverty, fewer than 15% receive needed mental health services (27), and Black children are less likely than White children to receive treatment (31). Fortunately, EHS/HS are effective vehicles for linking children and families with mental health services. HSPPS require provision of infant and early childhood mental health consultation, which is linked to reductions in children's behavioral challenges (32). Infant and early childhood mental health consultants partner with EHS/HS teachers to promote children's mental health via classroom practices and with case managers, teachers, and families to address children's behavioral concerns (33). Starting early is effective with children enrolled in HS at age 3 more likely to receive mental health treatment than those enrolled at age 4 (31).

Early intervention services

EI exists at the nexus of health, education, and social services by both the nature of services and legislative mandate. EI services are available to every U.S. child, birth to age 3, who has a developmental delay or diagnosed condition with a high probability of resulting delay. Services can include special instruction, psychological services, speech and language therapy, physical or occupational therapy, nursing and nutrition services, hearing and vision services, social work services, transportation, and assistive technology. More children are identified as eligible for EI as they age. Approximately 3.5% of children under age 2 received EI services and ~6.8% of children ages 3 to 5 received early childhood special education services in 2018 (34). However, ethnic-racial disparities are evident. For example, infants (age 9 months) receive EI services at approximately the same rate, but Black toddlers (age 24 months) are five times less likely to receive EI services than their White counterparts (35). Delays in identification are problematic because EI services can influence long-term success for children and families (36). EHS provides frequent developmental screening and supports families navigating the EI system; those enrolled in EHS (5.7%) were more likely to receive Part C services than those in a control group (3.7%) (37).

Recommendations to improve/strengthen delivery of these comprehensive services

The need to strengthen the availability and integration of services was illustrated by the COVID-19 pandemic that highlighted disparities in access and focused attention on the fragility and critical importance of U.S. early childhood “systems” (38). These lessons underscore the need to build more robust approaches that forge stronger connections across primary health care, ECE, social services, and other systems (38). Recommendations (summarized in Table 2) offered here to enhance cross-system collaboration apply to health, mental health, and EI service needs.

Table 2. Summary of recommendations to improve/strengthen delivery of comprehensive services to children and families.

Strengthen training and professional development

Cross-system collaboration calls for a paradigm shift in how systems engage with children and families and how they interact with each other (39). Strengthened professional development is needed to enhance integration. Specific recommendations include expanding preservice and inservice training on ERH and allied systems, including pediatric health and EHS, across professional domains. Discipline specific training could include preparing preservice (e.g., students in medicine, public health, social work, ECE) and front-line practitioners (e.g., home visitors, teachers, nurses, physicians) to attend to the complex interactions that impact mental health (e.g., historical trauma, systemic racism, environmental injustices) (40). Students would benefit from clinical experiences in both pediatric and EHS contexts. Incorporating information about EHS/HS and similar ECE programs into schools of medicine and public health would promote understanding and reinforce shared goals for promoting child health and wellbeing.

Expand screening and service delivery models

Integrating screening and comprehensive services would increase access to services, strengthen relationships among systems, and streamline service provision. Enhanced screenings and greater service access are key to integration of services, which includes efforts to embed child and family support into primary pediatric care (27). A related strategy could embed mobile pediatric care into EHS/HS programs, making services more accessible to families and facilitating provision of cross system services.

EHS/HS and community partners working together to provide free screenings, could reverse the unfortunate trend of decreasing access to screenings (e.g., vision, hearing, behavioral, developmental) without unnecessary burden on any partners (29). Additional barriers to screening include lack of families' access to consistent transportation and translation services (e.g., just 24% of HS agency respondents indicated health care providers had bilingual staff) (29).

Examining successful models can help generate ideas. For example, the National Center on Early Childhood Health Wellness (41) offers a step-by-step guide to building collaborations between EHS/HS and medical homes. Importantly, collaborations may begin small between a single pediatric clinic and one EHS program with both parties sharing expertise, materials, and information; building knowledge of each other; and supporting bidirectional referrals (41).

Another example, Warm Connections, integrates IMH services in local WIC programs (42). Trained clinicians provide brief mental health and parenting supports and referrals to community resources, including more intensive community mental health referrals. In addition to service access, pilot findings suggest the program may relieve parenting distress and increase parental efficacy.

Healthy Steps by Zero to Three (43) programs partner with pediatric clinics to offer families child development information and supports. services include screenings, referrals, and facilitating families' access to other services, including care coordination and systems navigation.

Strengthen infrastructure

Strengthening and coordinating administrative and data infrastructure is important for building working relationships and monitoring service effectiveness. Linking child health, education/care, and welfare data systems could promote improved communication and better understanding of service distribution; additionally, this could facilitate identification of service gaps. For example, linking kindergarten entrance assessments and medical records could facilitate appropriate screenings/referrals and target service areas (44). Cross sector data integration would enable annual reviews of service delivery, coordination, and gaps. A randomized trial linking child health directly with ECE services, in one urban pediatric clinic, showed a computer-generated enrollment packet sent directly to HS (referral letter, physical examination, and immunization records) from the pediatric office increased HS enrollment compared to providing parents a list of HS contacts (45). This approach resulted in increased HS attendance and increased HS direct contacts with families (46).

Navigators or guides can also shore-up infrastructure. Using navigation to assist in service coordination, reduce barriers, and increase family access has begun to move from medical to social service settings. Recently, Waid et al. (47) illustrated navigation services were successfully facilitated by clinicians, peers, paraprofessionals, service teams, or via self-direction in a variety of formats (e.g., in person, telephone, online). Diaz-Linhart et al. (48) evaluated a navigator program for families in HS, who were randomized to the navigation or a usual care group. Navigators worked successfully with families to overcome barriers with families receiving navigation reporting more connections with external mental health services than parents in the usual care group.

Acknowledge and reduce racism

The Head Start Head Start Early Childhood Learning and Knowledge Center (49) offers training designed to engage programs and professionals in conversations about racism, including recognizing and opposing racism in all forms (50), and developing anti-bias practices and policies. Trainings address levels (e.g., internalized, personally mediated, and institutionalized racism) (51) and forms of racism and implicit bias. Strategies such as reflective supervision may be effective in supporting practitioners' awareness of personal and systemic biases (52). The Annie E. Casey Foundation (53) offers a toolbox for setting goals/measuring success toward increasing racial equity, assessing the impact of policies on minoritized groups, and engaging community partners in promoting social change. Additional strategies include reporting health and education statistics by race and SES, already required for education records, to assist in identifying areas for increasing equity in access and service provision and examining current practices.

Identify, secure, and maximize resources

Peterson et al. (44) note the importance of funding to incentivize and drive innovations. The Healthy Steps by Zero to Three (43) program is financed by combining multiple funding streams including redistribution of health system and graduate medical education funds, reallocation of city/county/state/local/federal supports (e.g., tobacco and cannabis sales), and philanthropic organizations. given that collaborations may begin small, initial efforts may require minimal financial resources, providing time to collect pilot data to fuel more expansive funding applications. Another strategy is to identify and target funding to prompt innovative, transdisciplinary work outside the typical health and education siloes including potential federal funding supporting coordination efforts. For example, federal funds appropriated to the U.S. department of health and human services and jointly administered with the U.S. department of education provided preschool development grants birth-to-five, for which states could apply, to increase access to high-quality ECE. importantly, these funds could also be used to address coordination and integration of services across systems.

Other resources include conducting SWOT analyses (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats) (54), which can assist collaborating agencies in highlighting and leveraging strengths, addressing weakness, identifying opportunities, and minimizing threats to their collaborative efforts. The SWOT approach facilitates strategic planning across collaborating agencies/systems to optimize health services for young children in poverty (55).

Conclusions

Public health, pediatric healthcare, and EHS share a mission to enhance the wellbeing of young children, particularly those at developmental risk. Yet, each fails to reach all children and misses many of the most vulnerable. Employing comprehensive relational health models, emphasizing the interrelatedness of children's physical, mental, and developmental health, prompts new opportunities for collaborative partnerships between pediatric health systems and EHS to strengthen provision of comprehensive services. Finally, examples of strategies and tools were shared to inspire the development, implementation, and maintenance of collaborative comprehensive service models.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

DH: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HB-H: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CP: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was completed by the authors as part of the Early Head Start Research Workgroup funded by the Pritzker Family Foundation. We thank this funder and the other member of the Workgroup for their support of the development of this manuscript. DH was funded, in part, by the George Kaiser Family Foundation (GKFF), HB-H was partially supported by the USDA National Institute of Food and AgrWiculture, Hatch Project (MIC02700), CP partially funded by ISU's College of Human Sciences – Nancy Rygg Armbrust Professorship for Early Child Development and Education. The authors thank the Libraries of the University of Oklahoma and Iowa State University for subvention funding to support the publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Jani A, Lowry C, Haylor E, Wanninayake S, Gregson D. Leveraging the bi-directional links between health and education to promote long-term resilience and equality. J R Soc Med. (2022) 115:95–9. doi: 10.1177/01410768211066890

2. Suhrcke M, de Paz Nieves C. The Impact of Health and Health Behaviours on Educational Outcomes in High-Income Countries: A Review of the Evidence. Geneva: World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe (2011).

3. Chiang RJ, Meagher W, Slade S. How the whole school, whole community, whole child model works: creating greater alignment, integration, and collaboration between health and education. J School Health. (2015) 85:775–84. doi: 10.1111/josh.12308

4. Raghupathi V, Raghupathi W. The influence of education on health: an empirical assessment of OECD countries for the period 1995–2015. Arch Pub Health. (2020) 78:20. doi: 10.1186/s13690-020-00402-5

5. Muennig P, Robertson D, Johnson G, Campbell F, Pungello EP, Neidell M, et al. The effect of an early education program on adult health: the carolina Abecedarian project randomized controlled trial. Am J Pub Health. (2011) 101:512–6. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.200063

6. Campbell F, Conti G, Hechman JJ, Moon SH, Pinto R, Pungello E, et al. Early childhood investments substantially boost adult health. Science. (2014) 343:1478–85. doi: 10.1126/science.1248429

7. Schweinhart LJ, Montie J, Xiang Z, Barnett WS, Belfield CR, Nores M, et al. Lifetime Effects: The High/Scope Perry Preschool Study Through Age 40. London: High/Scope Press (2005).

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About CDC Healthy Schools. (2023). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/about.htm (accessed August 4, 2023).

9. Lewallen TC, Hunt H, Potts-Datema W, Zaza S, Giles W. The whole school, whole community, whole child model: a new approach for improving educational attainment and healthy development for students. J School Health. (2015) 85:729–39. doi: 10.1111/josh.12310

10. Raikes H, Yazejian N, Horm D, Peterson C, Herb-Brophy H, Chazan-Cohen R, et al. Specific comprehensive services in the context of early childhood programs (2023).

11. Horm DM, Jeon S, Clavijo MV, Acton M. Kindergarten through grade 3 outcomes associated with participation in high-quality early care and education: a RCT Follow-Up Study. Educ Scie. (2022) 12:908–30. doi: 10.3390/educsci12120908

12. Hill HA, Yankey D, Elam-Evans LD, Singleton JA, Sterrett N. Vaccination coverage by age 24 months among children born in 2017 and 2018- national immunization survey-child, United Stated, 2018-2020. MMWR. (2021) 70:1435–40. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7041a1

13. ZERO to THREE. State of Babies Yearbook, 2021. (2021). Available online at: https://stateofbabies.org/?_gl=1%2A1qd3b1f%2A_ga%2AMTQ1NDU3NDg3Ny4xNzA2NzIxMzU5%2A_ga_2YNPJ7MP63%2AMTcwNjcyMTM2MC4xLjEuMTcwNjcyMTM4Mi4wLjAuMA..%2A_ga_JGW29BDN22%2AMTcwNjcyMTM1OS4xLjEuMTcwNjcyMTM4OC4zMS4wLjA (accessed May 21, 2023).

14. Love JM, Kisker EE, Ross C, Raikes H, Constantine J, Boller K, et al. The effectiveness of early head start for 3-year-old children and their parents: lessons for policy and programs. Dev Psychol. (2005) 41:885–901. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.6.88

15. Head Start Early Childhood Learning and Knowledge Center. Head Start Program Facts: Fiscal Year 2021. (2021). Available online at: https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/about-us/article/head-start-program-facts-fiscal-year-2021 (accessed May 21, 2023).

16. Administration for Children and Families (ACF). Head Start Program Performance Standards. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office of Head Start (2018). Available online at: https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/policy/45-cfr-chap-xiii (accessed February 2, 2024).

17. USDHHS. Head Start Program: Final Rule. Federal Register, 61, 215. (1996). Available online at: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-1996-11-05/pdf/96-28134.pdf

18. Banghart P, Cook M, Zaslow M. Approaches to Providing Comprehensive Services in Early Head Start-Child Care Partnerships. ChildTrends. (2020). Available online at: https://www.childtrends.org/publications/approaches-to-providing-comprehensive-services-in-early-head-start-child-care-partnerships (accessed December 10, 2023).

19. Johnson-Staub C. Putting it Together: A Guide to Financing Comprehensive Services in Child Care and Early Education. (2012). Available online at: https://www.clasp.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/A-Guide-to-Financing-Comprehensive-Services-in-Child-Care-and-Early-Education.pdf

20. Willis DW, Eddy JM. Early relational health: Innovations in child health for promotion, screening, and research. Infant Ment Health J. (2022) 43:361–72. doi: 10.1002/imhj.21980

21. Metzler J, Willis D. Building Relationships: Framing Early Relational Health. Washington, DC: FrameWorks Institute (2020).

22. Administration for Children and Families. Health and Health Care Among Early Head Start Children. A Research-to Practice Brief From the Early Head Start and Research and Evaluation Project. (2006). Available online at: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/opre/healthcare.pdf (accessed May 21, 2023).

23. National Center for Education Statistics. Private School Enrollment. Condition of Education. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. (2022). Available online at: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/cgc (accessed August 29, 2023).

24. Head Start Early Childhood Learning and Knowledge Center. Head Start Program Facts: Fiscal Year 2019. (2022). Available online at: https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/about-us/article/head-start-program-facts-fiscal-year-2019 (accessed May 21, 2023).

25. Administration for Children and Families. Health and Health Care Among Early Head Start Children: Research to Practice Brief . (2019). Available online at: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/opre/report/health-and-health-care-among-early-head-start-children-research-practice-brief (accessed August 29, 2023).

26. Cree RA, Bitsko RH, Robinson LR, Holbrook JR, Danielson ML, Smith C. Health care, family, and community factors associated with mental, behavioral, and developmental disorders and poverty among children aged 2–8 years — United States, 2016. Morb Mort Weekly Rep. (2018) 67:1377–83. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6750a1

27. Hodgkinson S, Godoy L, Beers LS, Lewin A. Improving mental health access for low-income children and families in the primary care setting. Pediatrics. (2017) 139:e20151175. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-1175

28. Hutchins HJ, Barry CM, Wanga V, Bacon S, Njai R, Claussen AH, et al. Perceived racial/ethnic discrimination, physical and mental health conditions in childhood, and the relative role of other adverse experiences. Adv Res Sci. (2022) 3:181–94. doi: 10.1007/s42844-022-00063-z

29. National Head Start Association. Head Start and Early Head Start Health Benchmark and Trends Report. (2021). Available online at: https://www.nhsa.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021NHSAHealthBenchmarkReport.pdf (accessed December 12, 2021).

30. Ghandour RM, Sherman LJ, Vladutiu CJ, Ali MM, Lynch SE, Bitsko RH, et al. Prevalence and treatment of depression, anxiety, and conduct problems in US children. J Pediatr. (2019) 206:256–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.09.021

31. Lee K. Head Start enrollment and children's mental health treatment. J Commun Psychol. (2014) 42:823–37. doi: 10.1002/jcop.21655

32. Gilliam WS, Maupin AN, Reyes CR. Early childhood mental health consultation: Results of a statewide random-controlled evaluation. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2016) 55:754–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.06.006

33. National Center on Early Childhood Health and Wellness. Facilitating a Referral for Mental Health Services for Children and Their Families Within Early Head Start and Head Start. (2020). Available online at: https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/facilitating-referral-mental-health.pdf (accessed March 6, 2020).

34. U. S. Department of Education. 42nd Annual Report to Congress on the Implementation of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, 2020. (2020). Available online at: https://sites.ed.gov/idea/files/42nd-arc-for-idea.pdf (accessed March 3, 2023).

35. Bailey DB, Scarborough A, Hebbeler K. Families First Experiences With Early Intervention: National Early Intervention Longitudinal Study. NEILS Data Report. (2003). Available online at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED476293.pdf (accessed March 3, 2023).

36. Hebbeler K, Spiker D, Bailey D, Scarborough A, Mallik S, Simeonsson R, et al. Early Intervention for Infants and Toddlers With Disabilities and Their Families: Participants, Services, and Outcomes. Washington, DC: U.S. Office of Special Education Programs (2007).

37. Peterson CA, Wall S, Raikes HA, Kisker EE, Swanson ME, Jerald J, et al. Early Head Start: Identifying and serving children with disabilities. Topics Early Child Spec Educ. (2004) 24:76–88. doi: 10.1177/02711214040240020301

38. Shonkoff JP. Re-Envisioning, Not Just Rebuilding: Looking Ahead to a Post-COVID-19 World. Cambdridge, MA: Harvard University Center on the Developing Child (2021).

39. Miller AL, Stein SF, Sokol R, Varisco R, Trout P, Julian MM, et al. From zero to thrive: A model of cross-system and cross-sector relational health to promote early childhood development across the child-serving ecosystem. Infant Ment Health J. (2022) 43:624–37. doi: 10.1002/imhj.21996

40. Watson MF, Bacigalupe G, Daneshpour M, Han WJ, Parra-Cardona R. COVID-19 interconnectedness: health inequity, the climate crisis, and collective trauma. Fam Process. (2020) 59:832–46. doi: 10.1111/famp.12572

41. National Center on Early Childhood Health and Wellness. The Medical Home and Head Start Working Together. (2023). Available online at: https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/medical-home-head-start-working-together.pdf (accessed February 22, 2023).

42. Klawetter S, Glaze K, Sward A, Frankel KA. Warm connections: Integration of infant mental health services into WIC. Commun Ment Health J. (2021) 57:1130–41. doi: 10.1007/s10597-020-00744-y

43. Healthy Steps by Zero to Three. Early Childhood Development Experts in Pediatrics. (2023). Available online at: https://www.healthysteps.org (accessed April 8, 2023).

44. Peterson JW, Loeb S, Chamberlain LJ. The Intersection of health and education to address school readiness of all children. Pediatrics. (2018) 142:e20181126. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-1126

45. Silverstein M, Mack C, Reavis N, Koepsell TD, Gross GS, Grossman DC, et al. Effect of a clinic-based referral system to head start: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. (2004) 292:968–71. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.8.968

46. Silverstein M, Sand N, Glascoe FP, Gupta VB, Tonniges TP, O'Connor KG, et al. Pediatrician practices regarding referral to early intervention services: Is an established diagnosis important? Ambulat Pediatrics. (2006) 6:105–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2005.09.003

47. Waid J, Halpin K, Donaldson R. Mental health service navigation: a scoping review of programmatic features and research evidence. Soc Work Ment Health. (2021) 19:60–79. doi: 10.1080/15332985.2020.1870646

48. Diaz-Linhart Y, Silverstein M, Grote N, Cadena L, Feinberg E, Ruth BJ, et al. Patient navigation for mothers with depression who have children in head start: a pilot study. Soc Work Pub Health. (2016) 31:504–10. doi: 10.1080/19371918.2016.1160341

49. Head Start Early Childhood Learning and Knowledge Center (ECLKC). Advancing racial and ethnic Equity in Head Start. (2022). Available online at: https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/culture-language/article/advancing-racial-ethnic-equity-head-start (accessed November 19, 2022).

50. Trent M, Dooley DG, Dougé J. The impact of racism on child and adolescent health. Pediatrics. (2019) 144:e20191765. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1765

51. Jones CP. Levels of racism: a theoretic framework and a gardener's tale. Am J Pub Health. (2000) 90:1212–5. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.90.8.1212

52. Lingras KA. Mind the Gap (s): Reflective supervision/consultation as a mechanism for addressing implicit bias and reducing our knowledge gaps. Infant Ment Health J. (2022) 43:638–52. doi: 10.1002/imhj.21993

53. The Annie E. and Casey Foundation. Race Equity and Inclusion Action Guide. (2015). Available online at: https://www.aecf.org/resources/race-equity-and-inclusion-action-guide (accessed January 8, 2015).

54. Teoli D, Sanvictores T, An JS. WOT Analysis. StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing (2023).

Keywords: infant, child health services accessibility, interinstitutional relations, poverty, Early Head Start, cross-system collaboration

Citation: Horm DM, Brophy-Herb HE and Peterson CA (2024) Optimizing health services for young children in poverty: enhanced collaboration between Early Head Start and pediatric health care. Front. Public Health 12:1297889. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1297889

Received: 25 September 2023; Accepted: 29 January 2024;

Published: 14 February 2024.

Edited by:

Kevin Dadaczynski, Fulda University of Applied Sciences, GermanyReviewed by:

Fatma Ozlem Ozturk, Ankara University, TürkiyeCopyright © 2024 Horm, Brophy-Herb and Peterson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Diane M. Horm, ZGhvcm1Ab3UuZWR1

Diane M. Horm

Diane M. Horm Holly E. Brophy-Herb

Holly E. Brophy-Herb Carla A. Peterson

Carla A. Peterson