- Department of Health Care, The Third Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, Henan, China

Introduction: The cost-effectiveness study of syphilis screening in pregnant women has not been synthesized. This study aimed to synthesize the economic evidence on the cost-effectiveness of syphilis screening in pregnant women that might contribute to making recommendations on the future direction of syphilis screening approaches.

Methods: We systematically searched MEDLINE, PubMed, and Web of Science databases for relevant studies published before 19 January 2023 and identified the cost-effectiveness analyses for syphilis screening in pregnant women. The methodological design quality was appraised by the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) 2022 checklist.

Results: In total, 17 literature met the eligibility criteria for a full review. Of the 17 studies, four evaluated interventions using different screening methods, seven assessed a combination of syphilis testing and treatment interventions, three focused on repeat screening intervention, and four evaluated the interventions that integrated syphilis and HIV testing. The most cost-effective strategy appeared to be rapid syphilis testing with high treatment rates in pregnant women who were positive.

Discussion: The cost-effectiveness of syphilis screening for pregnancy has been widely demonstrated. It is very essential to improve the compliance with maternal screening and the treatment rates for positive pregnant women while implementing screening.

Introduction

Syphilis is caused by the Treponema pallidum bacterium, which can be transmitted vertically from mother to child during pregnancy. In 2016, an estimated 98,800 cases of maternal syphilis infections occurred worldwide (1). The rate of syphilis among reproductive-age women increased, leading to an increase in the rate of congenital syphilis (CS) (2). More than half of the pregnancies among women with active syphilis result in adverse pregnancy outcomes that can be avoided (3). Historical data show that untreated syphilis during pregnancy can lead to 25% late abortion or stillbirth, 13% premature or low birthweight, 11% neonatal death, and 20% classic symptoms and signs of syphilis-infected infants (4–6). To achieve the goal of eliminating CS, the World Health Organization regards the provision of syphilis screening and treatment in antenatal care (ANC) services as one of several prevention strategies (7).

The incidence rate of CS seems to be decreasing in several countries with the approaches to prevent syphilis advocated by the WHO (8, 9). Although syphilis is preventable and treatable, the incidence of CS is on a steady rise in high-income countries such as Australia and the United States (10, 11). Mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) of syphilis can occur at any time during gestation if syphilitic pregnant women cannot be identified and treated. In addition to syphilis testing in early pregnancy, high-risk pregnant women also need to be tested again at 28 weeks of gestation and delivery (12).

The prevalence of syphilis has been proven to be closely associated with HIV epidemiologically (13). This may be because the two infections have a common route of transmission, and syphilitic genital ulcer increases the probability of HIV infection (14). However, the coverage for HIV screening is several times higher than for syphilis, and newborns who do not acquire HIV infection still have a high risk of syphilis infection (15, 16). HIV antenatal screening integrated with syphilis testing can not only improve the maternal syphilis screening rate but also prove to be cost-effective due to the inexpensive penicillin treatment (17–19).

Several studies have indicated that the screening and treatment of maternal syphilis as a public health intervention reduces adverse pregnancy and birth outcomes and medical costs and improves the quality of life of pregnant women and newborns (20–22). Health policymakers should make rational use of resources based on different incidence rates and social and economic development in different regions. The economic value obtained from the integration of cost and clinical effect is one of the most important outcomes in the evaluation of the comparative effects of medical interventions. Although the high cost-effectiveness of the screening approach depends on the high incidence rate generally, the cost-effectiveness of maternal screening has been proven in areas with low syphilis incidence (18).

Evidence-based estimates of the cost-effectiveness of screening pregnant women for syphilis help make the case for rational allocation of health resources, improve the efficiency of intervention approaches, and make progress toward elimination. Previous estimates have assessed the cost-effectiveness of screening pregnant women for syphilis based on the local syphilis prevalence, screening strategies, and economic levels. We performed a systematic review of the published evidence on the cost-effectiveness of syphilis screening in pregnant women with respect to the extent to which the evidence on the cost-effectiveness of screening has changed. In addition to this, we aimed to estimate the optimal screening strategies and extract information from cost-effectiveness analyses across different studies to provide a scientific basis for the formulation of a suitable syphilis screening strategy.

Methods

Search strategy

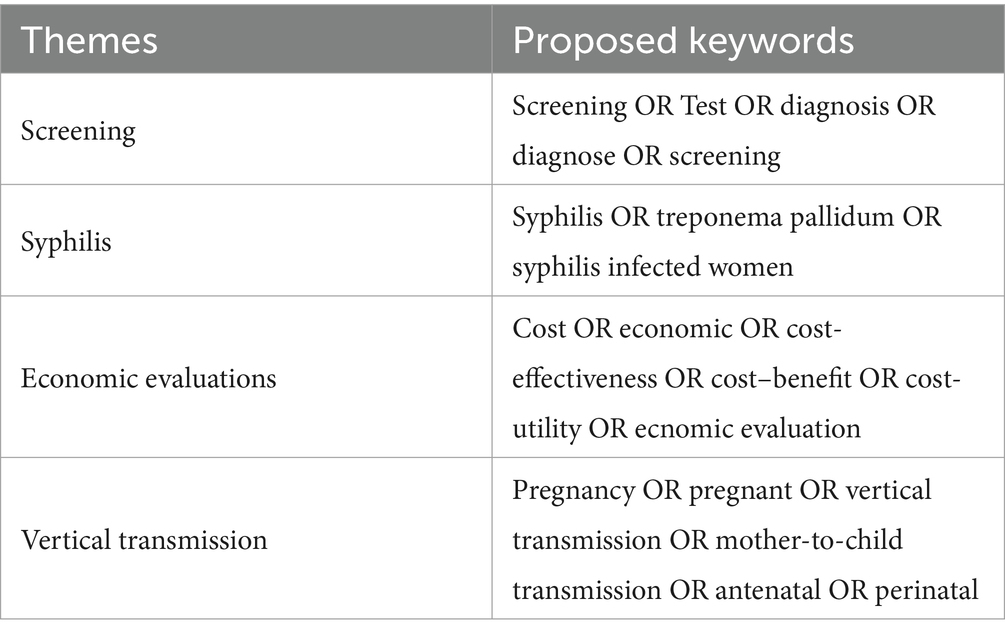

We searched MEDLINE, PubMed, and Web of Science for the cost-effectiveness of syphilis antenatal screening literature from the earliest available data in each database to 19 January 2023. We adopted the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) statement for this systematic review (23). To identify relevant economic assessments, we used the following terms: syphilis, treponema pallidum, pregnancy, antenatal, vertical transmission, mother-to-child transmission, screening, test, diagnose, cost-effectiveness, economic, cost-utility, and cost–benefit (Table 1). The search strategy was composed of medical subject title (MeSH) terms, free text terms, and AND/OR terms. Duplicates were excluded using the software EndNote X9.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We selected eligible studies using the following reported inclusion criteria: cost-effectiveness studies based on clinical trials or model-based assessments related to syphilis antenatal screening, papers evaluating syphilis testing approach economic value, and papers written in English or Chinese.

The economic assessments included in this review were cost-effectiveness, cost-utility, or cost–benefit analyses. The outcomes of these studies would include at least one of the following: cost per diagnosis of syphilis in pregnant women, cost per averted adverse birth outcomes, cost per quality-adjusted life years (QALY), and the total cost of screening pregnant women for syphilis approaches. We excluded the studies that focused solely on cost analyses or exclusively assessed the cost-effectiveness of syphilis treatment.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two independent reviewers summarized the retrieved results and extracted the information of interest. The differences between the two were discussed and resolved. Data extracted included analysis type, country, target population, sample size, intervention, incidence, perspective, outcomes, and costs.

The economic assessments of the methodological quality of syphilis screening in pregnant women were evaluated by the 28-item Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) 2022 checklist (24). For the list, each item was scored using “Yes” if the article met the quality criterion, “Not applicable” if the item does not apply to a particular economic evaluation, and “Not reported” if the information is otherwise not reported.

Results

Search results

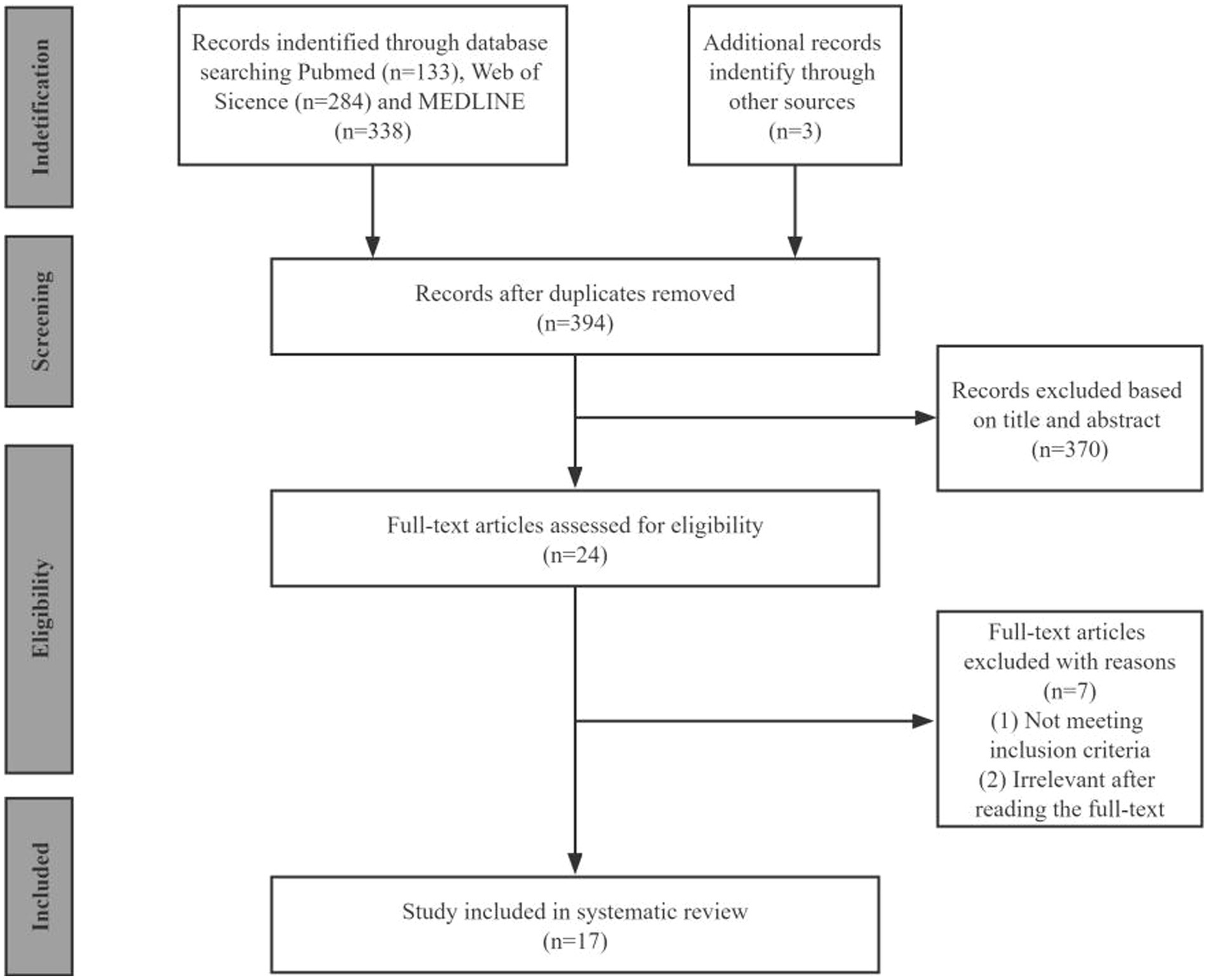

By searching the three databases, we identified 758 publications (PubMed: 133, Web of Science: 284, and MEDLINE: 338). After removing duplicates and excluding irrelevance, we collected 24 articles for full-text review. We identified 17 eligible studies for a final full review as shown in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

Quality assessment

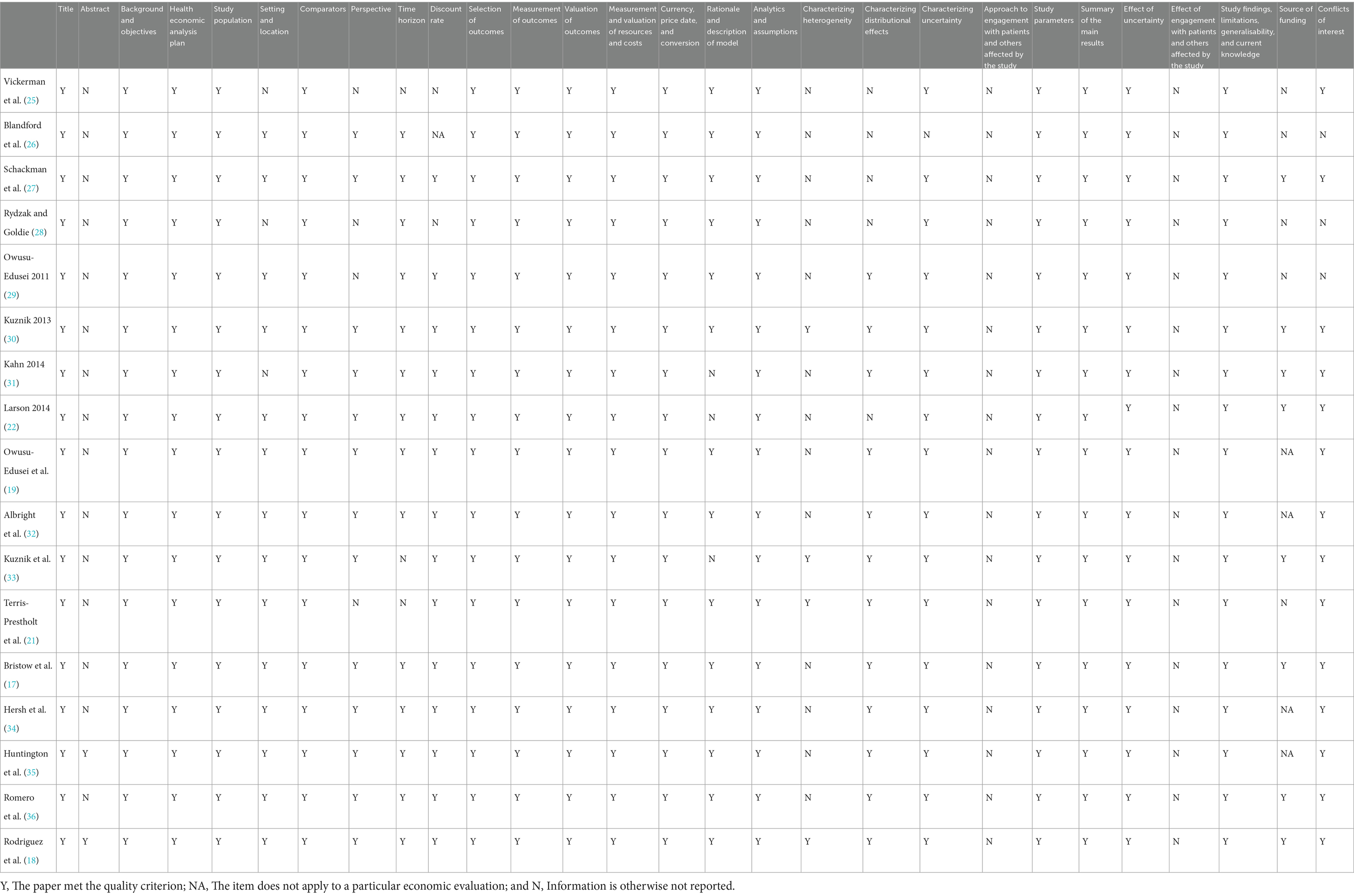

The quality assessment of the 17 studies using the CHEERS 2022 checklist is presented in Table 2. Most of the articles met most of the items in the CHEERS 2022 checklist. The abstracts of most of the articles did not report enough information about the context of highlights and alternative analyses. In contrast to CHEERS 2013, none of the studies met the items related to patient or service recipient, general public, and community or stakeholder involvement and engagement that were added to the CHEERS 2022 checklist. Multiple studies have failed to report where publicly available models can be found, which was encouraged in CHEERS 2022.

General and economic features of the studies

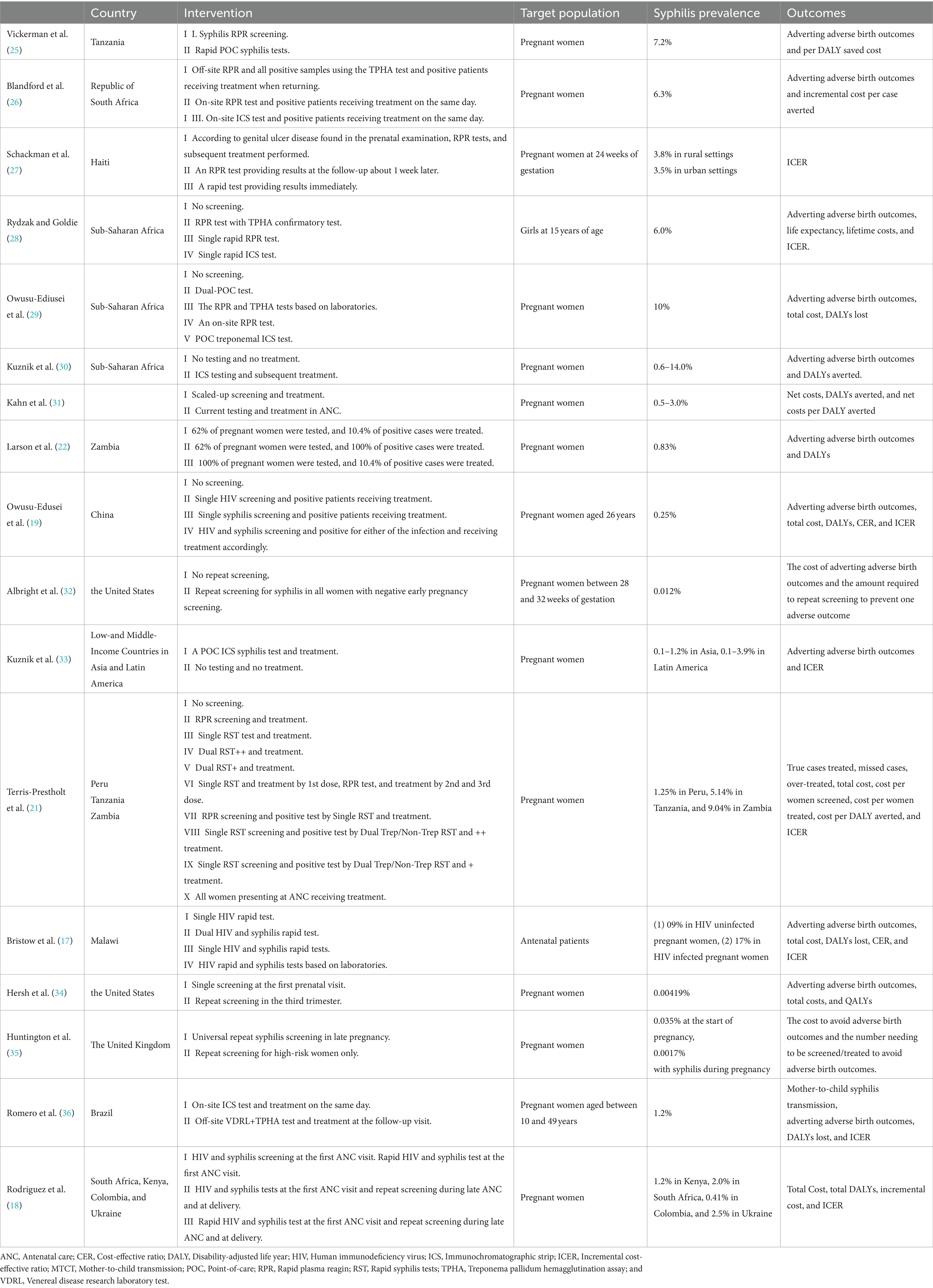

An overview of the main study characteristics of the 17 included cost-effectiveness studies is shown in Table 3. With the exception of one article that did not identify a specific target setting, the 16 included studies were based on a total of 40 countries or regions. The majority (N = 15) of the 16 included studies were based on low-income (N = 9) and middle-income (N = 6) settings, with the exception of two high-income countries. More than half of the studies were conducted in Africa (N = 9), six in America, two in Asia, and two in Europe. The lowest prevalence rate of syphilis among the 17 studies was 0.00419%, and the highest was 10%. In addition to one study targeting 15-year-old girls, 16 studies targeted pregnant women, 12 of which did not identify the characteristics of pregnant women, while two studies identified the age of pregnant women (26 and 10–49 years old, respectively), and two studies identified the gestational weeks of pregnant women (24 and 28–32 weeks, respectively). A majority of the studies (N = 13, 76%) were cost-utility analyses (CUAs); of which, outcome measures used disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) (N = 12) or quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) (N = 1). Four studies performed cost-effectiveness analysis using incremental cost per case averted as an outcome. Of the 17 studies, four studies evaluated interventions using different screening methods, including rapid plasma reagin (RPR), rapid syphilis test, immunochromatographic strip test (ICS), and treponema pallidum hemagglutination assay (TPHA); seven studies assessed the combination of syphilis test and treatment interventions; and three studies focused on repeat screening intervention. In addition, four studies mixed interventions to integrate syphilis and HIV testing.

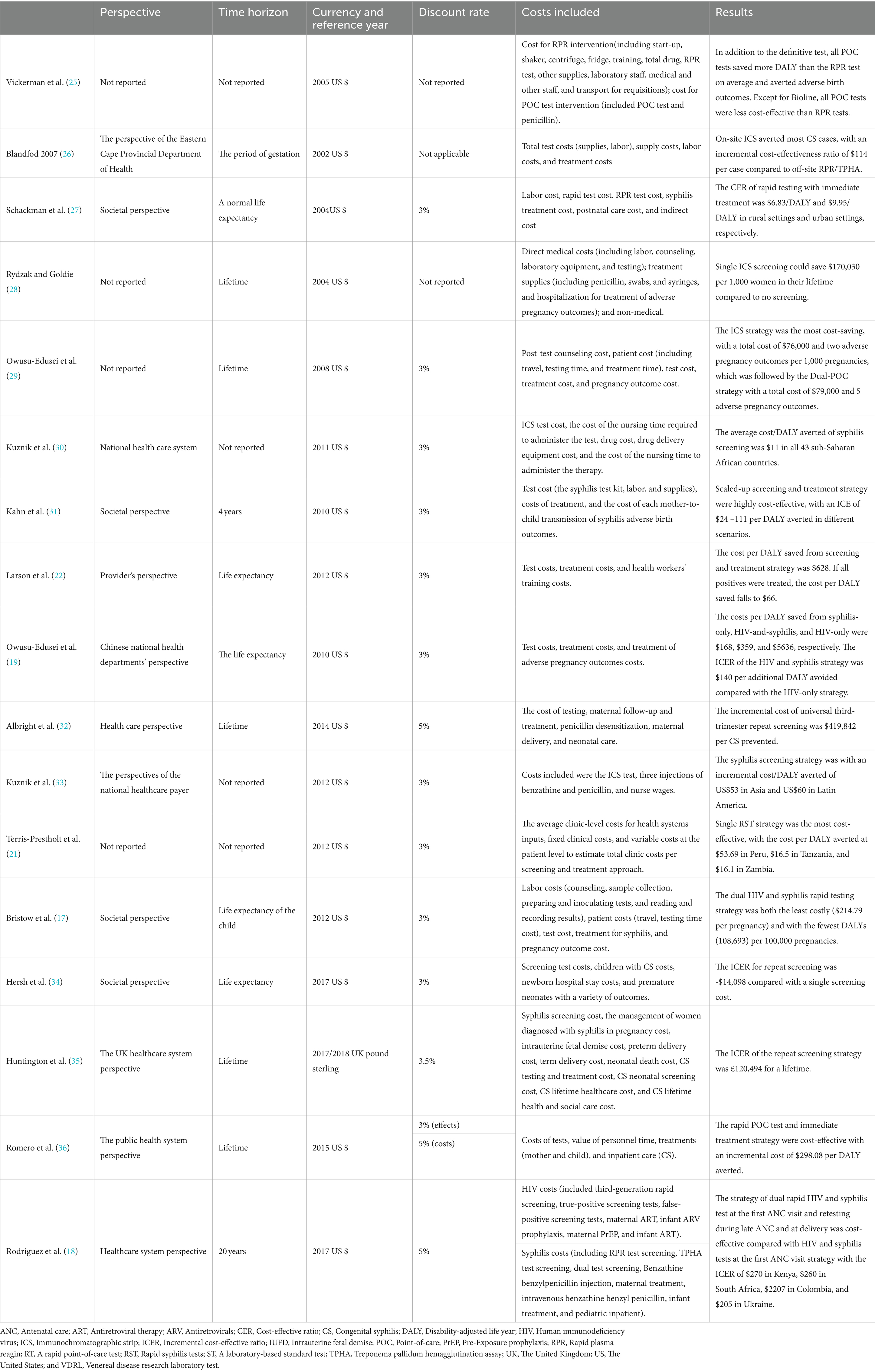

Table 4 presents information on the following categories: perspective, time horizon, currency and reference year, discount rate, costs included, and main results. In addition to the four unreported studies’ research perspectives, four were social perspectives, eight were health system perspectives, and one was provider perspective. The cost of most studies included testing, counseling, treatment, and labor costs. Of the included studies, 10 had a lifetime horizon, one had a gestation period, one had a 4-year time horizon, and one had a 20-year time horizon. The currency used in most of the studies was the US dollar, and only one study used the United Kingdom pound sterling. Among the included studies, two studies did not report the discount rate, and one study did not need to report the discount rate due to less than 1-year time horizon. The discount rate of 10 studies was 3%, two studies were 5%, and one study was 3.5%. One study used 3% for effect discount and 5% for cost discount.

Table 4. The perspective, time horizon, currency and reference year, discount rate, costs included, and main results of the 17 studies.

Cost-effectiveness of the different tests

Vickerman et al. (25) estimated the cost-effectiveness of using the rapid POC syphilis tests compared with rapid plasma reagin (PRP) in the Mwanza antenatal syphilis screening. POC tests saved more disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) than the RPR test but were less cost-effective than the RPR test unless the cost of POC was $0.63. Rydzak et al. assessed the cost-effectiveness of three screening strategies, namely, conventional two-step screening using an RPR test followed by a Treponema pallidum hemagglutination assay (TPHA) confirmatory test, single-visit rapid RPR, and single-visit rapid immunochromatographic strip (ICS) compared with no screening. They found that compared with no screening, single visits with ICS was a cost-saving strategy of US$170,303 per 1,000 women over their lifetime (28). Owusu-Ediusei et al. compared the health and economic outcomes of four testing/screening algorithms, namely, the dual-POC test, RPR+TPHA algorithm, an onsite PRP testing, and ICS testing, and the results showed that the dual-POC test was the most cost saving (saved $30,000) in resource-poor and high prevalence settings (29).

Cost-effectiveness of syphilis tests and treatments

The scaling-up of syphilis screening and treatment strategy was likely to be highly cost-effective in a wide range of settings (31). Larson et al. (22) reported on a model-based study and found that syphilis screening was only cost-effective for reducing adverse birth outcomes if positive patients were treated. ICS testing and subsequent treatment strategy were proved to be highly cost-effective compared with no testing and no treatment in Sub-Saharan Africa and low- and middle-income countries in Asia and Latin America (30–33). The ICS test, which involved the same-day treatment of those testing positive, was cost-effective compared to PRP/TPHA that needed patients returning for results and treatment in high maternal syphilis prevalence settings such as the Republic of South Africa and Brazil (26, 36). Terris-Prestholt et al. (21) assessed the cost-effectiveness of maternal syphilis screening using rapid syphilis tests (RSTs) detecting only treponema pallidum antibodies (single RSTs) or both treponemal and non-treponemal antibodies (dual RSTs). They found that the single RST and treatment should be the best approach unless the price of the dual RST was significantly reduced (21).

Cost-effectiveness of repeat syphilis screening

Albright et al. (32) estimated the cost-effectiveness of universal third-trimester syphilis repeat screening in the United States compared to no-repeat screening, and they found that the repeat screening approach was at a high healthcare cost to prevent adverse outcomes. The universal repeat screening was also proved to be not cost-effective in the United Kingdom setting of a low syphilis prevalence (35). However, Hersh et al. (34) reported that the strategy of screening all women during the first and third trimesters was cost-effective and improved maternal and neonatal outcomes in the United States.

Cost-effectiveness of integrated HIV and syphilis screening

The integrated screening strategy using a rapid syphilis test as a part of prenatal HIV test would prevent CS cases and stillbirths and would be cost-effective in Haiti (27). In addition, Bristow et al. (17) found that a dual HIV and syphilis test was even cost-saving. Owusu-Edusei et al. assessed the health and economic outcomes of four different strategies of HIV and syphilis screening in pregnant women, namely, no screening, screening for HIV only, screening for syphilis only, and screening for both HIV and syphilis. The results showed that prenatal HIV screening, including syphilis screening, would be substantially more cost-effective than HIV screening alone in China (19). Rodriguez et al. (18) modeled and evaluated the cost-effectiveness of dual maternal HIV and syphilis testing during ANC and retesting during late ANC strategies in high and low HIV prevalence countries, and they found that the dual rapid diagnosis test was cost-saving compared with individual HIV and syphilis tests. The strategy of retesting during late ANC with a dual rapid diagnostic test was evaluated to be cost-effective compared with the strategy of screening syphilis and HIV with the dual rapid diagnosis test in the first ANC visit (18).

Discussion

Pregnant women infected with syphilis not only endanger their own health but also cause intrauterine infection of the fetus, resulting in abortion, premature birth, stillbirth, or delivery of CS children, which greatly endangers the health of the offspring (37, 38). Based on the prevalence and harm of CS, the WHO put forward a global action plan for eliminating CS in 2007 and formulated corresponding strategies (9). Syphilis screening during pregnancy and treatment of positive pregnant women can effectively reduce MTCT and improve the eugenic rate. Studies have shown that pregnant women with syphilis can effectively prevent adverse pregnancy outcomes through early diagnosis and intervention (3, 38, 39). To select the best screening strategy for syphilis during pregnancy, a detailed and comprehensive economic evaluation is needed to provide a basis for health policymakers. This systematic review aimed to synthesize the results of cost-effectiveness analyses of screening for prevention of MTCT of syphilis and summarize the available evidence.

The cost-effectiveness of universal early pregnancy syphilis screening was evaluated in developed countries, developing countries, and countries with limited resources. The results of the economic evaluation show that in developed countries or countries with limited resources, screening pregnant women for syphilis is cost-effective compared with no screening. In addition, early pregnancy screening in areas with high syphilis incidence is not only cost-effective but there is also economic value in intervening in syphilis screening in countries with very low syphilis prevalence. Screening compliance may affect the cost-effectiveness of screening. In addition, women with poor compliance generally carry a higher burden of syphilis. Focusing on improving the screening rates in this population may improve the health benefits of screening. The treatment rate of positive pregnant women can also affect the cost-effectiveness of screening strategies, mainly because screening can timely detect positive pregnant women and intervene on time to effectively reduce the incidence of CS, thereby improving the quality of life of newborns and reducing economic costs. All of the included studies showed that the maternal syphilis screening strategy was cost-effective. However, the specific policy context and economic development of different countries must be taken into account in the analysis, and the results of other countries cannot be directly used.

Serological tests for syphilis include the treponema pallidum test and the non-treponema pallidum test. The titer of the non-treponema pallidum test is associated with syphilis activity. Most patients with syphilis have passed standard treatment and have turned negative for non-treponema pallidum but remain positive for treponema pallidum or even lifelong positive. At present, a non-treponema pallidum antigen test (such as RPR) is used as the primary screening, and a treponema pallidum antigen test (such as TPHA) is used as the confirmation strategy. However, because the screening for syphilis often needs to be based on laboratory testing, it is largely limited by the existing technical conditions, especially in developing countries and primary care institutions.

In addition, the included literature compared the cost-effectiveness of various testing methods, summarized the results of different testing methods, and further evaluated the best options for syphilis screening. The main reason is that rapid testing can effectively integrate testing and treatment, improve treatment compliance among positive pregnant women, and effectively reduce the occurrence of adverse pregnancy outcomes, especially in regions with limited resources. In 2004, the WHO put forward the urgent need for new POC diagnostic tests for bacterial sexually transmitted infections and formulated standards to highlight that POC testing should be affordable, have reliable sensitivity and specificity, simple to operate, require no training, quick, no need for refrigeration supply chain, and no additional laboratory equipment (40, 41). Most of the available syphilis POC tests detect antibodies against the syphilis pathogen Treponema pallidum (TP) and can be used as a screening test. Most studies included showed that POC tests were cost-effective and would improve both maternal and infant outcomes compared to the traditional tests (28, 29). The study in Tanzania found that the high cost of the POC test might limit its cost-effectiveness value (25).

Although repeated screening is recommended for high-risk pregnant women (42–44), the evidence for economic evaluation is still inadequate. The results of the articles included in this study show that syphilis repeat screening in the third trimester of pregnancy might not be cost-effective, but the areas implementing that intervention were restricted to developed countries, such as the United Kingdom and the United States (32, 34, 35). The conclusions remain heterogeneous. Albright et al. (32) found that it was unlikely that the universal repeated screening for syphilis in the third trimester of pregnancy has cost-effectiveness value in the environment with low syphilis prevalence in the United States. In contrast, this study did not use quality-adjusted life years as a measure of health outcomes, which could underestimate the impact of CS on health quality. However, Hersh et al. (34) showed that repeated syphilis screening on third-trimester pregnant women in the United States may have cost-effectiveness value. In Hersh’s study, the incidence of maternal syphilis was 0.00419%, while the probability of syphilis infection during pregnancy was 0.012% (34). The higher incidence of syphilis infection during pregnancy makes repeated screening during pregnancy more cost-effective. However, the optimal interval between the first and second tests is not considered, and it is unclear whether the cost-effectiveness deteriorates when the interval is shortened. Therefore, the optimal time interval needs to be well-evaluated.

Testing coverage for HIV is often higher than for syphilis, and the integration of syphilis and HIV testing may improve the coverage of syphilis testing (15, 45, 46). The genital ulcer disease caused by syphilis infection can increase the risk of horizontal transmission of HIV among the maternal population, making the infection rate of syphilis-infected maternal HIV higher than that in the general maternal population (47–49). Syphilis infection during pregnancy can cause pathological changes in the placenta, destroying the normal function of the maternal-fetal circulatory system, thus affecting the growth and development of the fetus and promoting the MTCT of HIV (50, 51). The combined screening of syphilis and HIV for pregnant women can not only significantly improve the coverage of screening but the results of the overall cost-effectiveness studies included in this study showed that the integrated screening was cost-effective and also cost-saving (17–19, 27).

The evaluation results of most of the studies included are conservative, and the effects of screening interventions on high-risk behaviors in mothers are not considered in the models, which may underestimate the cost-effectiveness of screening. Some studies have shown that the transmission rate of people who do not know their infection is higher than those who know their conditions (52, 53). Thus, maternal screening may reduce the risk of sexual transmission, as well as the potential impact of encouraging positive maternal partners to be tested, but these effects have not been considered. In addition, most studies aimed to assess the health effects on infants and do not include the health effects on mothers after pregnancy, and the health output of maternal syphilis screening may be underestimated. It is also important to assess the negative benefits, such as the psychological burden on the mother, as these may significantly affect the quality of life and thus the ultimate cost-effectiveness of screening. Most studies have been conducted under the following assumptions: (1) syphilis prevalence is the same among women who accept screening and those who refuse, (2) the side effects of antiviral treatment are ignored, (3) the costs do not cover indirect medical costs, and (4) syphilis screening results do not significantly affect pregnant women’s reproductive choices.

The cost-effectiveness analysis studies generally discount future costs and health outcomes. Most of the studies included in this study used discount rates ranging from 3 to 5%. One study used a discount rate of 5% for costs and 3% for health outcomes (36). However, the best discount rates and whether to use different discount rates for costs and health outcomes remain controversial.

Sensitivity analysis allows for a more accurate assessment of the reliability of cost-effectiveness analysis results and minimizes the uncertainty caused by the lack of accurate data on the key parameters. All included studies used sensitivity analysis to evaluate the stability of reported results, including one-dimensional sensitivity analysis and probability sensitivity analysis. These studies mainly focused on the impact of changes in the prevalence, sensitivity, and specificity of syphilis testing, as well as the cost and screening acceptance rate on the cost-effectiveness of screening. However, it is increasingly difficult to accurately predict health outcomes and lifetime costs as screening costs, therapeutic regimens, and treatment costs are constantly changing. There was also heterogeneity in the research perspectives of the included studies, with some studies only considering costs incurred in the healthcare perspective and not including indirect costs due to time costs, which may also have an impact on the results, and others were analyzed from the whole society perspective.

This study also has some limitations. First, the literature included in the study is mainly concentrated in a small number of countries, mainly in Africa, which may lead to an overestimation of the actual infection rate. Second, only three studies have evaluated related issues in developed countries, which may also lead to limitations in extrapolating our findings to developed countries. Third, most of the studies included in this study focus on more specific local situations, potentially creating limitations in generalizability. Finally, this study included only the literature published in English, which may have had a language bias effect on the results, leading to the miss of some other potentially important studies.

Conclusion

Overall, this study presented a systematic review of published evidence on the cost-effectiveness of syphilis screening in pregnancy to provide a scientific basis for the development of appropriate syphilis screening strategies. The cost-effectiveness of syphilis screening in pregnancy compared with no screening has been widely established. In resource-limited areas with high syphilis incidence, rapid testing has the best cost-effectiveness value. In developing countries with better health resources, screening strategies based on more accurate serological tests are preferable. Repeat syphilis screening strategies in the third trimester are less likely to be cost-effective in developed countries, where the incidence of syphilis is low. While implementing the screening, it is even important to improve compliance with maternal screening and positive maternal treatment rates. Indeed, those with poor adherence were more likely to be at high risk. Furthermore, syphilis screening in combination with HIV screening should be advocated and promoted. To effectively prevent MTCT of syphilis and eliminate CS, in addition to adopting the strategy of syphilis screening and treatment during pregnancy and childbirth, we also need to strengthen education and supervision, pay attention to the shame and fear of syphilis on pregnant women and their families, and improve the compliance of syphilis screening and treatment for pregnant women. In addition, strengthening international cooperation to comprehensively improve and enhance the availability of quality medical care is also the key to achieving the goal of eliminating CS.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

MZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HZ: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. XH: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. HQ: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. JX: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. FX: Writing – review & editing. CS: Writing – review & editing. JH: Writing – review & editing. YC: Writing – review & editing. MH: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by the Joint Construction Project of Medical Science and Technology Breakthrough Plan of Henan Province (LHGJ20220554), the Maternal and Child Taige Care and Prevention of Mother to Child Transmission Fund of China Association for STD and AIDS Prevention and Control (PMTCT202206), and the PhD research startup foundation of the Third Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University (BS20230103).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Korenromp, EL, Rowley, J, Alonso, M, Mello, MB, Wijesooriya, NS, Mahiané, SG, et al. Global burden of maternal and congenital syphilis and associated adverse birth outcomes-estimates for 2016 and progress since 2012. PLoS One. (2019) 14:e0211720. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0211720

2. Stafford, IA, Sánchez, PJ, and Stoll, BJ. Ending congenital syphilis. JAMA. (2019) 322:2073–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.17031

3. Gomez, GB, Kamb, ML, Newman, LM, Mark, J, Broutet, N, and Hawkes, SJ. Untreated maternal syphilis and adverse outcomes of pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bull World Health Organ. (2013) 91:217–26. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.107623

4. Hawkes, S, Matin, N, Broutet, N, and Low, N. Effectiveness of interventions to improve screening for syphilis in pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. (2011) 11:684–91. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70104-9

5. Watson-Jones, D, Changalucha, J, Gumodoka, B, Weiss, H, Rusizoka, M, Ndeki, L, et al. Syphilis in pregnancy in Tanzania. I. Impact of maternal syphilis on outcome of pregnancy. J Infect Dis. (2002) 186:940–7. doi: 10.1086/342952

6. Schmid, G . Economic and programmatic aspects of congenital syphilis prevention. Bull World Health Organ. (2004) 82:402–9.

7. WHO (2008). The Global Elimination of Congenital Syphilis: Rationale and Strategy for Action. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/the-global-elimination-of-congenital-syphilis-rationale-and-strategy-for-action.

8. McCauley, M, and van den Broek, N. Eliminating congenital syphilis-lessons learnt in the United Kingdom should inform global strategy. BJOG. (2017) 124:78–8. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14038

9. WHO (2021). Global Guidance on Criteria and Processes for Validation: Elimination of Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV, Syphilis and Hepatitis B Virus. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240039360.

10. Wu, MX, Moore, A, Seel, M, Britton, S, Dean, J, Sharpe, J, et al. Congenital syphilis on the rise: the importance of testing and recognition. Med J Aust. (2021) 215:345–346.e1. doi: 10.5694/mja2.51270

11. Center for Disease Control and Prevention (2020). Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2020: National overview. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/std/statistics/2020

12. Ghanem, KG, Ram, S, and Rice, PA. The modern epidemic of syphilis. N Engl J Med. (2020) 382:845–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1901593

13. Adawiyah, RA, Saweri, OPM, Boettiger, DC, Applegate, TL, Probandari, A, Guy, R, et al. The costs of scaling up HIV and syphilis testing in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Health Policy Plan. (2021) 36:939–54. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czab030

15. Baker, U, Okuga, M, Waiswa, P, Manzi, F, Peterson, S, Hanson, C, et al. Bottlenecks in the implementation of essential screening tests in antenatal care: syphilis, HIV, and anemia testing in rural Tanzania and Uganda. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. (2015) 130:S43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.04.017

16. Peeling, RW, Mabey, D, Fitzgerald, DW, and Watson-Jones, D. Avoiding HIV and dying of syphilis. Lancet. (2004) 364:1561–3. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17327-3

17. Bristow, CC, Larson, E, Anderson, LJ, and Klausner, JD. Cost-effectiveness of HIV and syphilis antenatal screening: a modelling study. Sex Transm Infect. (2016) 92:340–6. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2015-052367

18. Rodriguez, PJ, Roberts, DA, Meisner, J, Sharma, M, Owiredu, MN, Gomez, B, et al. Cost-effectiveness of dual maternal HIV and syphilis testing strategies in high and low HIV prevalence countries: a modelling study. Lancet Glob Health. (2021) 9:e61–71. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30395-8

19. Owusu-Edusei, KJ, Tao, G, Gift, TL, Wang, A, Wang, L, Tun, Y, et al. Cost-effectiveness of integrated routine offering of prenatal HIV and syphilis screening in China. Sex Transm Dis. (2014) 41:103–10. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000085

20. Saweri, OP, Batura, N, Adawiyah, RA, Causer, L, Pomat, W, Vallely, A, et al. Cost and cost-effectiveness of point-of-care testing and treatment for sexually transmitted and genital infections in pregnancy in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review protocol. BMJ Open. (2019) 9:e029945. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029945

21. Terris-Prestholt, F, Vickerman, P, Torres-Rueda, S, Santesso, N, Sweeney, S, Mallma, P, et al. The cost-effectiveness of 10 antenatal syphilis screening and treatment approaches in Peru, Tanzania, and Zambia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. (2015) 130:S73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.04.007

22. Larson, BA, Lembela-Bwalya, D, Bonawitz, R, Hammond, EE, Thea, DM, and Herlihy, J. Finding a needle in the haystack: the costs and cost-effectiveness of syphilis diagnosis and treatment during pregnancy to prevent congenital syphilis in Kalomo District of Zambia. PLoS One. (2014) 9:e113868. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113868

23. Liberati, A, Altman, DG, Tetzlaff, J, Mulrow, C, Gøtzsche, PC, Ioannidis, JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. (2009) 339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700

24. Husereau, D, Drummond, M, Augustovski, F, de Bekker-Grob, E, Briggs, AH, Carswell, C, et al. Consolidated health economic evaluation reporting standards 2022 (CHEERS 2022) statement: updated reporting guidance for health economic evaluations. BMJ. (2022) 376:e067975. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2021-067975

25. Vickerman, P, Peeling, RW, Terris-Prestholt, F, Changalucha, J, Mabey, D, Watson-Jones, D, et al. Modelling the cost-effectiveness of introducing rapid syphilis tests into an antenatal syphilis screening programme in Mwanza. Tanz Sex Transmit Infect. (2006) 82:V38–43. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.021824

26. Blandford, JM, Gift, TL, Vasaikar, S, Mwesigwa-Kayongo, D, Dlali, P, and Bronzan, RN. Cost-effectiveness of on-site antenatal screening to prevent congenital syphilis in rural eastern cape province, republic of South Africa. Sex Transm Dis. (2007) 34:S61–6. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000258314.20752.5f

27. Schackman, BR, Neukermans, CP, Fontain, SN, Nolte, C, Joseph, P, Pape, JW, et al. Cost-effectiveness of rapid syphilis screening in prenatal HIV testing programs in Haiti. PLoS Med. (2007) 4:e183–947. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040183

28. Rydzak, CE, and Goldie, SJ. Cost-effectiveness of rapid point-of-care prenatal syphilis screening in sub-Saharan Africa. Sex Transm Dis. (2008) 35:775–84. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318176196d

29. Owusu-Edusei, KJ, Gift, TL, and Ballard, RC. Cost-effectiveness of a dual non-Treponemal/Treponemal syphilis point-of-care test to prevent adverse pregnancy outcomes in sub-Saharan Africa. Sex Transm Dis. (2011) 38:997–1003. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3182260987

30. Kuznik, A, Lamorde, M, Nyabigambo, A, and Manabe, YC. Antenatal syphilis screening using point-of-care testing in sub-Saharan African countries: a cost-effectiveness analysis. PLoS Med. (2013) 10:e1001545. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001545

31. Kahn, JG, Jiwani, A, Gomez, GB, Hawkes, SJ, Chesson, HW, Broutet, N, et al. The cost and cost-effectiveness of scaling up screening and treatment of syphilis in pregnancy: a model. PLoS One. (2014) 9:e87510. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087510

32. Albright, CM, Emerson, JB, Werner, EF, and Hughes, BL. Third-trimester prenatal syphilis screening a cost-effectiveness analysis. Obstet Gynecol. (2015) 126:479–85. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000997

33. Kuznik, A, Muhumuza, C, Komakech, H, Marques, EM, and Lamorde, M. Antenatal syphilis screening using point-of-care testing in low-and middle-income countries in Asia and Latin America: a cost-effectiveness analysis. PLoS One. (2015) 10:e0127379. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127379

34. Hersh, AR, Megli, CJ, and Caughey, AB. Repeat screening for syphilis in the third trimester of pregnancy a cost-effectiveness analysis. Obstet Gynecol. (2018) 132:699–707. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002795

35. Huntington, S, Weston, G, Seedat, F, Marshall, J, Bailey, H, Tebruegge, M, et al. Repeat screening for syphilis in pregnancy as an alternative screening strategy in the UK: a cost-effectiveness analysis. BMJ Open. (2020) 10:e038505. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-038505

36. Romero, CP, Marinho, DS, Castro, R, de Aguiar Pereira, CC, Silva, E, Caetano, R, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of point-of-care rapid testing versus laboratory-based testing for antenatal screening of syphilis in Brazil. Value Health Reg Issues. (2020) 23:61–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vhri.2020.03.004

37. Keuning, MW, Kamp, GA, Schonenberg-Meinema, D, Dorigo-Zetsma, JW, van Zuiden, JM, and Pajkrt, D. Congenital syphilis, the great imitator-case report and review. Lancet Infect Dis. (2020) 20:e173–9. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30268-1

38. Garcia, JFB, Aun, MV, Motta, AA, Castells, M, Kalil, J, and Giavina-Bianchi, P. Algorithm to guide re-exposure to penicillin in allergic pregnant women with syphilis: efficacy and safety. World Allergy Organ J. (2021) 14:100549. doi: 10.1016/j.waojou.2021.100549

39. Newman, L, Kamb, M, Hawkes, S, Gomez, G, Say, L, Seuc, A, et al. Global estimates of syphilis in pregnancy and associated adverse outcomes: analysis of multinational antenatal surveillance data. PLoS Med. (2013) 10:e1001396. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001396

40. Adamson, PC, Loeffelholz, MJ, and Klausner, JD. Point-of-care testing for sexually transmitted infections: a review of recent developments. Arch Pathol Lab Med. (2020) 144:1344–51. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2020-0118-RA

41. Toskin, I, Murtagh, M, Peeling, RW, Blondeel, K, Cordero, J, and Kiarie, J. Advancing prevention of sexually transmitted infections through point-of-care testing: target product profiles and landscape analysis. Sex Transm Infect. (2017) 93:S69–80. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2016-053071

42. Workowski, KA, and Bolan, GA. Bolan,Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. (2015) 64:1–137.

43. Workowski, KA, Bachmann, LH, Chan, PA, Johnston, CM, Muzny, CA, Park, I, et al. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. MMWR Recomm Rep. (2021) 70:1–187. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr7004a1

44. Tsai, S, Sun, MY, Kuller, JA, Rhee, EHJ, and Dotters-Katz, S. Syphilis in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Surv. (2019) 74:557–64. doi: 10.1097/OGX.0000000000000713

45. Tucker, JD, Yang, LG, Zhu, ZJ, Yang, B, Yin, YP, Cohen, MS, et al. Integrated syphilis/HIV screening in China: a qualitative analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. (2010) 10:58. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-58

46. Tucker, JD, Yang, LG, Yang, B, Zheng, HP, Chang, H, Wang, C, et al. A twin response to twin epidemics: integrated HIV/syphilis testing at STI clinics in South China. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. (2011) 57:e106–11. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31821d3694

47. Phiri, S, Zadrozny, S, Weiss, HA, Martinson, F, Nyirenda, N, Chen, CY, et al. Etiology of genital ulcer disease and association with HIV infection in Malawi. Sex Transm Dis. (2013) 40:923–8. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000051

48. The Cochrane CollaborationMutua, FM, M'Imunya, MJ, and Wiysonge, CS. Genital ulcer disease treatment for reducing sexual transmission of HIV. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2012) 15:CD007933. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007933

49. Zetola, NM, and Klausner, JD. Syphilis and HIV infection: an update. Clin Infect Dis. (2007) 44:1222–8. doi: 10.1086/513427

50. Sheffield, JS, Sánchez, PJ, Wendel, GDJ, Fong, DW, Margraf, LR, Zeray, F, et al. Placental histopathology of congenital syphilis. Obstet Gynecol. (2002) 100:126–33. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02010-0

51. Mwapasa, V, Rogerson, SJ, Kwiek, JJ, Wilson, PE, Milner, D, Molyneux, ME, et al. Maternal syphilis infection is associated with increased risk of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in Malawi. AIDS. (2006) 20:1869–77. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000244206.41500.27

52. Hall, HI, Holtgrave, DR, and Maulsby, C. HIV transmission rates from persons living with HIV who are aware and unaware of their infection. AIDS. (2012) 26:893–6. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328351f73f

Keywords: syphilis, screening, cost-effectiveness, pregnant women, review

Citation: Zhang M, Zhang H, Hui X, Qu H, Xia J, Xu F, Shi C, He J, Cao Y and Hu M (2024) The cost-effectiveness of syphilis screening in pregnant women: a systematic literature review. Front. Public Health. 12:1268653. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1268653

Edited by:

Ellie Jordan Putz, Agricultural Research Service (USDA), United StatesReviewed by:

Rogério Valois Laurentino, Federal University of Pará, BrazilDomenico Marino, Mediterranea University of Reggio Calabria, Italy

Copyright © 2024 Zhang, Zhang, Hui, Qu, Xia, Xu, Shi, He, Cao and Hu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mengcai Hu, YmFvamlhbmJ1aG1jQDE2My5jb20=;emRzZnliamJAMTYzLmNvbQ==

Meng Zhang

Meng Zhang Hongyan Zhang

Hongyan Zhang