94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Public Health , 07 December 2023

Sec. Public Mental Health

Volume 11 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1323303

This article is part of the Research Topic Community Series in Mental Illness, Culture, and Society: Dealing with the COVID-19 Pandemic, volume VIII View all 63 articles

Introduction: Nurses are more likely to experience anxiety following the coronavirus 2019 epidemic. Anxiety could compromise nurses’ work efficiency and diminish their professional commitment. This study aims to investigate nurses’ anxiety prevalence and related factors following the pandemic in multiple hospitals across China.

Methods: An online survey was conducted from April 16 to July 3, 2023, targeting frontline nurses who had actively participated in China. Anxiety and depression symptoms were assessed using the Self-rating Anxiety Scale and the Self-rating Depression Scale (SDS), respectively. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was employed to identify factors linked with anxiety.

Results: A total of 2,210 frontline nurses participated in the study. Overall, 65.07% of participants displayed clinically significant anxiety symptoms. Multivariable logistic regression revealed that nurses living with their families [2.52(95% CI: 1.68–3.77)] and those with higher SDS scores [1.26(95% CI: 1.24–1.29)] faced an elevated risk of anxiety. Conversely, female nurses [0.02(95% CI: 0.00–0.90)] and those who had recovered from infection [0.05(95%CI: 0.07–0.18)] demonstrated lower rates of anxiety.

Discussion: This study highlights the association between SDS score, gender, virus infection, living arrangements and anxiety. Frontline nurses need to be provided with emotional support to prevent anxiety. These insights can guide interventions to protect the mental well-being of frontline nurses in the post-pandemic period.

During the coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, occupational health issues have escalated rapidly in workplaces (1). Extended use of personal protective equipment has been linked to an increase in dermatological reactions (2). From December 2019 to June 2020, a significant number of frontline healthcare workers, totaling 22,380, who were caring for COVID-19 patients, reported experiencing anxiety, depression, or stress (3). Therefore, the adoption of suitable coping styles may be pivotal in mitigating the negative impacts on mental health (4).

Nurses occupy a pivotal role in managing the COVID-19 pandemic (5). Their continuous engagement in combating the pandemic, often marked by extended work hours and minimal rest opportunities, has rendered them susceptible to psychological distress (6). The incidence of mental health problems in nurses is higher than that of the general population due to an array of stressors (7). Emerging evidence suggests that the psychological ramifications of the pandemic are enduring (8–12).

It is very common for clinical nurses to experience anxiety and depression (13). Notably, their anxiety levels throughout the pandemic exceeded other healthcare workers (14). Approximately 37% clinical nurses reported anxiety during the breakout of the pandemic (15). They were still troubled by anxiety even in the late stage of the epidemic (16). Excessive working hours, fear of infection, decision-making dilemmas in care prioritization, and shortages of equipment were identified as primary anxiety sources among nurses (17, 18). Severe anxiety could compromise their work efficiency and diminish their professional commitment (19). An integrated approach to managing the factors that impact the mental health of frontline nurses can effectively alleviate their psychological distress, thereby enhancing the quality of care provided (20). However, to our knowledge, no previous study specifically assessed anxiety and associated factors among Chinese nurses following the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, comprehending anxiety’s determinants among nurses holds potential for guiding anxiety-alleviating strategies.

We conducted the present study to evaluate the mental health outcomes among a large sample of Chinese nurses following the COVID-19 pandemic by evaluating anxiety symptoms, and by analyzing associated risk factors.

This is a large-scale cross-sectional and multicentre study that investigated clinical nurses’ anxiety symptoms and its associated factors following the COVID-19 epidemic. The description of the study was done following STROBE guidelines for reporting observational studies (21).

A large-scale online survey was performed to collect data from frontline nurses following the COVID-19 pandemic in 27 provinces in China. Raosoft1 was used to assess the sample size required for this study. According to China Daily,2 the total number of nurses has now exceeded 5.2 million. A minimum of 385 nurses was needed with margin of error (5%), confidence level (95%) and response distribution (50%).

Inclusion criteria: (1) Nurses engaged in frontline work following the COVID-19 pandemic, and (2) voluntary participation in this study. Exclusion criteria: (1) Lack of the professional qualification certificate, and (2) unwilling to participate in this study.

Demographic characteristics (title, gender, age, personality, virus infection, economic pressure, living style, worried about being infected, and SDS score) were collected. Anxiety was assessed via the Self-rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) (22). The Zung SAS contains 20 items, each with a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (none) to 4 (all of the time). A cut-off score of 36 was used to screen for clinically significant anxiety symptoms (23). Depression levels were assessed using the Self-rating Depression Scale (SDS) (24), which consists of 20 items. Each item on the scale is rated from 1 to 4. The total score is computed using the standard scoring method, where the SDS score is multiplied by 1.25. In the Chinese population, the Cronbach’s alpha values for the SAS and SDS were determined to be 0.92 and 0.93, respectively, demonstrating high reliability (25).

SPSS 23.0 was used for Statistical analyses. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. Comparisons between categorical variables were performed by chi square (χ2) test, and SDS scores between anxious and non-anxious participants were compared by the independent t test. Multivariate regression analysis was used to evaluate the impact of the diverse factors with statistically significant differences in χ2 or t-test on anxiety. The results of multivariate regression analysis were shown as adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CIs). A p was considered significant if <0.05. For Bonferroni correction, a p < 0.001 (0.01/10) was considered significant. In continuous variables, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was used to assessed associated variable predictive value for anxiety. GraphPad Prism 9.0 generated forest plots.

Ultimately, a total of 2,210 nurses were included in the study based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. Most nurses were between 26 and 35 years old. Of the participants, 80.27% were women, and 68.14% lived with their families. More details of the participants are shown in Table 1. There were statistically significant differences between anxious and non-anxious participants in terms of SDS score, gender, virus infection and living style after Bonferroni correction (p < 0.001) (Tables 2, 3).

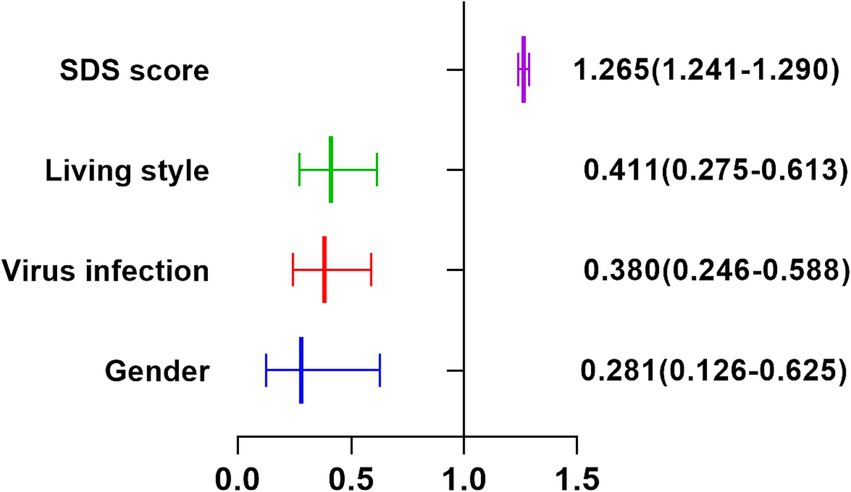

We further evaluated the relationship between anxiety and factors with statistically significant differences in Tables 2, 3 using multivariate regression analysis. We found an association between SDS score, gender, virus infection, living style and anxiety (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Forest plot for logistic regression analysis of the influencing factors of anxiety among nursing staffs.

As shown in Table 4, multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed for anxiety (SAS⩾36) by categorical covariates. Overall, nurses who lived with their families or had higher SDS scores had higher percentages of anxiety, while female nurses or nurses who had recovered from infection had lower percentages of anxiety.

ROC analysis indicated SDS score has a good predictive value for anxiety (AUC = 0.90, 95% CI: 0.88–0.91) (Figure 2).

This study underscored that a significant proportion of frontline nurses experienced anxiety following the COVID-19 pandemic (65.07%), slightly surpassing the proportion observed in China’s later pandemic stages (54%) (16). Potential reasons for this inconsistency may be associated with the difference in methods as this study (16) adopted the different cut-off scores and different assessment scales to define clinically significant anxiety. However, a validated cut-off score was used to detect anxiety symptoms in our study. Moreover, sporadic COVID-19 cases in China post-pandemic might contribute to sustained frontline nurse anxiety levels.

Our result is consistent with that of a previous study, as the prevalence of anxiety among nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic was 71.9% (26), which might be because the epidemic in Turkey was already under control when Gül et al. conducted his study (26). However, the proportion of participants with clinically significant anxiety symptoms is slightly smaller than that in Turkey. It is possible that nurses in Turkey suffered from more anxiety since they have never experienced such a serious epidemic in the past, or even learned the knowledge of controlling the epidemic. Compared with nurses in Turkey, Chinese nurses were more confident in managing the epidemic based on their previous experience.

Female participants reported lower anxiety than male participants, probably because the latter were less confident and more uncertain about the future than the former. However, a recent study has discovered that female participants are more prone to experiencing stress and anxiety (27). The discrepancy in the survey results may be associated with the fact that our study only included nurses who worked in hospitals following the epidemic. The new findings provided important evidence for managers to formulate new psychological intervention strategies in male nurses following the epidemic.

Our results showed that participants who have recovered from the COVID-19 infection following the epidemic have a lower risk of anxiety compared to those who have not been infected. The possible reasons are explained as follows: First, they believed that they had developed antibodies due to previous infection and would be protected from being reinfected in the near future; Secondly, the clinical symptoms caused by the infection are not as serious as expected; Finally, they believed that there are already effective treatment methods and vaccines that can effectively prevent reinfection.

Participants who lived with their families experienced more anxiety than those living with colleagues because they not only need to do more housework, but also need to learn how to educate children, and take care of the older adult. The increased workload is associated with the risk of developing anxiety (28, 29). On the other hand, they did not have enough time for self-care. Research shows that self-care is very important for nurses (30). If nurses cannot maintain self-care, it will lead to stress, anxiety and burnout (31–33). Although research showed that social support is important for mental health (34), people who have been married are more likely to experience anxiety than those who are single (35).

We found that the higher the SDS score, the more likely the participants were to suffer from anxiety. This finding could be explained by the fact that anxiety and depression may share a common pathogenesis, or one disorder is an epiphenomenon of the other (36). According to our results of ROC analysis, SDS score had a good predictive value for anxiety elevation. However, the predictive potential of SDS score for anxiety elevation still needs to be further verified by studies in different population following the COVID-19 pandemic.

This study had some strengths and limitations. The strengths of this study: (1) Our study only included frontline nurses, which helps to understand the mental health outcome of frontline nurses following the COVID-19 pandemic and assists managers in formulating interventions and preventive actions, (2) Our study included frontline nurses from 27 provinces, and the findings are representative of the mental health outcome of frontline nurses following the epidemic, (3) Multidimensional examination of factors influencing anxiety; The possible limitations of this study: (1) Cross-Sectional Design: The cross-sectional design of this study restricts our ability to infer causal relationships between anxiety and the identified factors. Longitudinal studies are needed to better understand the temporal dynamics of anxiety among frontline nurses. (2) Self-Report Measures: The reliance on self-reported measures for anxiety and depression symptoms may introduce response bias and subjective interpretations. Objective clinical assessments could enhance the accuracy of mental health evaluations. (3) Social Desirability Bias: Participants might have provided responses they deemed socially desirable, potentially influencing the reported prevalence of anxiety or other associated factors. (4) Regional Focus: The study was conducted exclusively in China and might not fully represent the experiences and mental health outcomes of frontline nurses in other countries or cultural contexts. (5) Generalizability of Findings: While efforts were made to include a diverse sample from multiple provinces, the variation in healthcare settings, COVID-19 impact, and socioeconomic factors across regions might limit the generalizability of the study’s findings.

In conclusion, the current study indicated an association between SDS score, gender, virus infection, living style and anxiety among frontline nurses, which may hopefully assist managers in implementing interventions following the COVID-19 pandemic.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics Committee of Tianjin Anding Hospital. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

ShiW: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Writing – original draft. GL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft. DP: Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Supervision, Validation, Visualization. XD: Writing – review & editing, Data curation. FY: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Resources. LZ: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. ShuoW: Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Software. XM: Investigation, Resources, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by Natural Science Foundation of Anhui Provincial Education Department (2022AH050756).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html

2. ^http://ex.chinadaily.com.cn/exchange/partners/70/rss/channel/www/columns/y38633/stories/WS64643210a310b6054fad35ef.html

1. Gualano, MR, Santoro, PE, Borrelli, I, Rossi, MF, Amantea, C, Daniele, A, et al. TElewoRk-RelAted stress (TERRA), psychological and physical strain of working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Workplace Health Saf. (2023) 71:58–67. doi: 10.1177/21650799221119155

2. Santoro, PE, Borrelli, I, Gualano, MR, Proietti, I, Skroza, N, Rossi, MF, et al. The dermatological effects and occupational impacts of personal protective equipment on a large sample of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Public Health. (2022) 9:815415. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.815415

3. Salari, N, Khazaie, H, Hosseinian-Far, A, Khaledi-Paveh, B, Kazeminia, M, Mohammadi, M, et al. The prevalence of stress, anxiety and depression within front-line healthcare workers caring for COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-regression. Hum Resour Health. (2020) 18:100. doi: 10.1186/s12960-020-00544-1

4. Rossi, MF, Gualano, MR, Magnavita, N, Moscato, U, Santoro, PE, and Borrelli, I. Coping with burnout and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on workers' mental health: a systematic review. Front Psych. (2023) 14:1139260. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1139260

5. Shechter, A, Diaz, F, Moise, N, Anstey, DE, Ye, S, Agarwal, S, et al. Psychological distress, coping behaviors, and preferences for support among New York healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. (2020) 66:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2020.06.007

6. Nie, A, Su, X, Zhang, S, Guan, W, and Li, J. Psychological impact of COVID-19 outbreak on frontline nurses: a cross-sectional survey study. J Clin Nurs. (2020) 29:4217–26. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15454

7. World Health Organization. Nursing and midwifery. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/nursing-and-midwifery

8. Ausín, B, González-Sanguino, C, Castellanos, MA, Sáiz, J, Zamorano, S, Vaquero, C, et al. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain: a longitudinal study. Psicothema. (2022) 34:66–73. doi: 10.7334/psicothema2021.290

9. Dharra, S, and Kumar, R. Promoting mental health of nurses during the coronavirus pandemic: will the rapid deployment of Nurses' training programs during COVID-19 improve self-efficacy and reduce anxiety? Cureus. (2021) 13:e15213. doi: 10.7759/cureus.15213

10. Kumar, R, Das, A, Singh, V, Gupta, PK, and Bahurupi, YA. Rapid survey of psychological status of health-care workers during the early outbreak of COVID-19 pandemic: a single-Centre study at a tertiary care hospital in northern India. J Med Evid. (2021) 2:213–8. doi: 10.4103/JME.JME_8_21

11. Kumar, R, Beniwal, K, and Bahurupi, Y. Pandemic fatigue in nursing undergraduates: role of individual resilience and coping styles in health promotion. Front Psychol. (2022) 13:940544. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.940544

12. Dahiya, H, Goswami, H, Bhati, C, Yadav, E, Bhanupriya, Tripathi, D, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 omicron variant and psychological distress among frontline nurses in a major COVID-19 center: implications for supporting psychological well-being. J Prim Care Spec. (2023) 4:p10–6. doi: 10.4103/jopcs.jopcs_22_22

13. Chen, J, Liu, X, Wang, D, Jin, Y, He, M, Ma, Y, et al. Risk factors for depression and anxiety in healthcare workers deployed during the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2021) 56:47–55. doi: 10.1007/s00127-020-01954-1

14. Hacimusalar, Y, Kahve, AC, Yasar, AB, and Aydin, MS. Anxiety and hopelessness levels in COVID-19 pandemic: a comparative study of healthcare professionals and other community sample in Turkey. J Psychiatr Res. (2020) 129:181–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.07.024

15. Al Maqbali, M, Al Sinani, M, and Al-Lenjawi, B. Prevalence of stress, depression, anxiety and sleep disturbance among nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res. (2021) 141:110343. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110343

16. Peng, P, Chen, Q, Liang, M, Liu, Y, Chen, S, Wang, Y, et al. A network analysis of anxiety and depression symptoms among Chinese nurses in the late stage of the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:996386. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.996386

17. Braquehais, MD, Vargas-Cáceres, S, Gómez-Durán, E, Nieva, G, Valero, S, Casas, M, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of healthcare professionals. QJM. (2020):hcaa207. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcaa207

18. Ruiz-Fernández, MD, Ramos-Pichardo, JD, Ibáñez-Masero, O, Cabrera-Troya, J, Carmona-Rega, MI, and Ortega-Galán, ÁM. Compassion fatigue, burnout, compassion satisfaction and perceived stress in healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 health crisis in Spain. J Clin Nurs. (2020) 29:4321–30. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15469

19. Labrague, LJ, and De Los Santos, JAA. COVID-19 anxiety among frontline nurses: predictive role of organisational support, personal resilience and social support. J Nurs Manag. (2020) 28:1653–61. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13121

20. Barr, P. Moral distress and considering leaving in NICU nurses: direct effects and indirect effects mediated by burnout and the hospital ethical climate. Neonatology. (2020) 117:646–9. doi: 10.1159/000509311

21. Cuschieri, S. The STROBE guidelines. Saudi J Anaesth. (2019) 13:S31–4. doi: 10.4103/sja.SJA_543_18

22. Zung, WW. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics. (1971) 12:371–9. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(71)71479-0

23. Dunstan, DA, and Scott, N. Norms for Zung’s self-rating anxiety scale. BMC Psychiatry. (2020) 20:90. doi: 10.1186/s12888-019-2427-6

24. Zung, WW. Self-rating depression scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (1965) 12:63–70. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1965.01720310065008

25. Liu, Z, Qiao, D, Xu, Y, Zhao, W, Yang, Y, Wen, D, et al. The efficacy of computerized cognitive behavioral therapy for depressive and anxiety symptoms in patients with COVID-19:randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. (2021) 23:e26883. doi: 10.2196/26883

26. Gül, Ş, and Kılıç, ST. Determining anxiety levels and related factors in operating room nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic: a descriptive study. J Nurs Manag. (2021) 29:1934–45. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13332

27. Santoro, PE, Borrelli, I, Gualano, MR, Amantea, C, Tumminello, A, Daniele, A, et al. Occupational hazards and gender differences: a narrative review. Ital J Gend-Specif Med. (2022) 8:154–62. doi: 10.1723/3927.39110

28. Koksal, E, Dost, B, Terzi, Ö, Ustun, YB, Özdin, S, and Bilgin, S. Evaluation of depression and anxiety levels and related factors among operating theater workers during the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. J Perianesth Nurs. (2020) 35:472–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jopan.2020.06.017

29. Mo, Y, Deng, L, Zhang, L, Lang, Q, Liao, C, Wang, N, et al. Work stress among Chinese nurses to support Wuhan for fighting against the COVID-19 epidemic. J Nurs Manag. (2020) 28:1002–9. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13014

30. Adams, M, Chase, J, Doyle, C, and Mills, J. Self-care planning supports clinical care: putting total care into practice. Prog Palliat Care. (2020) 28:305–7. doi: 10.1080/09699260.2020.1799815

31. Hossain, F, and Clatty, A. Self-care strategies in response to nurses’ moral injury during COVID-19 pandemic. Nurs Ethics. (2021) 28:23–32. doi: 10.1177/0969733020961825

32. Liu, N, Zhang, F, Wei, C, Jia, Y, Shang, Z, Sun, L, et al. Prevalence and predictors of PTSS during COVID-19 outbreak in China hardest-hit areas: gender differences matter. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 287:112921. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112921

33. Liu, S, Yang, L, Zhang, C, Xiang, YT, Liu, Z, Hu, S, et al. Online mental health services in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry. (2020) 7:e17–8. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30077-8

34. Su, X, and Guo, LL. Relationship between psychological elasticity, work stress and social support of clinical female nurses. Chinese Occup Med. (2015) 42:55–8. doi: 10.11763/j.issn.2095-2619.2015.01.013

35. Han, L, Wong, FKY, She, DLM, Li, SY, Yang, YF, Jiang, MY, et al. Anxiety and depression of nurses in a north west province in China during the period of novel coronavirus pneumonia outbreak. J Nurs Scholarsh. (2020) 52:564–73. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12590

Keywords: anxiety symptoms, clinical nurses, interventions, post-pandemic period, related factors

Citation: Wang S, Luo G, Pan D, Ding X, Yang F, Zhu L, Wang S and Ma X (2023) Anxiety prevalence and associated factors among frontline nurses following the COVID-19 pandemic: a large-scale cross-sectional study. Front. Public Health. 11:1323303. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1323303

Received: 17 October 2023; Accepted: 22 November 2023;

Published: 07 December 2023.

Edited by:

Renato de Filippis, University Magna Graecia of Catanzaro, ItalyReviewed by:

Ivan Borrelli, Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, Rome, ItalyCopyright © 2023 Wang, Luo, Pan, Ding, Yang, Zhu, Wang and Ma. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shitao Wang, d2FuZ3NoaXRhb21kQDE2My5jb20=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.