95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Public Health , 03 January 2024

Sec. Public Health and Nutrition

Volume 11 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1296620

This article is part of the Research Topic School-based nutrition and physical activity interventions among children and adolescents View all 14 articles

Mavra Ahmed1,2

Mavra Ahmed1,2 Alana Richardson1

Alana Richardson1 Jessica Riad1

Jessica Riad1 Chelsea McPherson1,2

Chelsea McPherson1,2 Daniel W. Sellen1,2

Daniel W. Sellen1,2 Vasanti S. Malik1,2,3*

Vasanti S. Malik1,2,3*Introduction: Following the sudden closure of schools due to the pandemic in 2020, many school food program (SFP) operators lost their operating venues and had to innovate to continue distributing meals to children. Our objective was to assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the delivery, adaptability, and resiliency of school food programs across Canada by conducting a systematic rapid review.

Materials and methods: Systematic literature searches identified newspaper articles and social media sources related to the adaptations and challenges faced by school food programs across Canada in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Included sources were assessed and thematically categorized according to the dimensions of the Analysis Grid for Environments Linked to Obesity (ANGELO) and Getting To Equity (GTE) frameworks to identify factors impacting the delivery, adaptability, and resiliency of school food programs in Canada.

Results: School food programs in Canada made various efforts to meet existing and new challenges associated with the delivery of these programs to keep feeding school children, particularly those most vulnerable, during the pandemic. Distribution of food kits, prepared meals and gift cards/coupons were successful pathways in ensuring support for food accessibility to students and their families. Increased collaborations between community members and organizations/stakeholders to help maintain food delivery or collectively offer new modes to deliver foods were most frequently cited as key to facilitating school food programming. However, maintenance and sustainability related to operating costs and funding were identified as key challenges to successful school food programming.

Conclusion: Our study highlights the swift and substantial transformation school food programs, underwent in response to the pandemic, driven by the urgent need to ensure that students still had access to nutritious meals and the importance of policy and resource support to bolster the adaptability and resiliency of these programs. Findings on facilitators and challenges to school food programs during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic can inform development of guidelines to design a robust national Canadian school food program and help make existing programs more sustainable, adaptable, and resilient.

On March 2020, the COVID-19 outbreak was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) (1), resulting in stresses on economies and food supply chains around the world, and disproportionately impacting the world’s most vulnerable populations, including children. The number of food insecure children nearly doubled due to the COVID-19 pandemic (2). Lockdown measures and school closures during the pandemic are key factors in driving increased food insecurity, by cutting off children’s access to the food sources they once relied on during the school week, especially for children already living in poverty or those with lower socioeconomic status (3).

In Canada, the food retail landscape rapidly evolved during the COVID-19 pandemic through consumer panic buying, increased operating costs of grocery stores (due to new enhanced safety precautions) and potential food shortages as a result of closed manufacturing plants, which led to increases in food prices, particularly for certain core food (i.e., recommended) categories (4). Many Canadians were and are currently faced with reduced work hours or unemployment, lower incomes, and decreased food budgets as a result of the pandemic (5) thereby increasing their risk of food insecurity and poor diet quality. In Canada, as across the world, fractured school operating schedules or long-term school closures mean that many students may no longer have access to meals through voluntary school programs that they may have relied on under normal circumstances to meet their nutritional needs (6). As COVID-19 continues to disrupt the food retail environment and create growing economic uncertainty, children and their families are at increased risk of poor nutrition (6).

School environments that reinforce positive habits and practices are critical in shaping the well-being of children and adolescents, who spend a considerable portion of their day at school. In Canada, children and adolescents reportedly consume about one-third of their daily energy at school, with most of it coming from foods low in nutritional quality (7). While schools could be a channel for nutritious foods through national school food programs, Canada remains one of the few industrialized countries without one (8). Instead, municipal, and provincial/territorial governments and non-governmental organizations support a patchwork of school food programming across Canada (9, 10). Recent evidence suggests that the participation rates of these mixed efforts in school food programming ranges from approximately 5% in Alberta to 83% in Yukon (11). Despite varying participation, school food programs offer a source of quality nutrition for children who may come to school hungry for various reasons (e.g., food insecurity).

School food programs serve nutritious meals and snacks, ensuring consistent access to healthy foods for children. With abrupt school closures due to lockdown measures, many programs faced challenges finding new ways to distribute meals. While news articles captured the adaptation and resilience of school food programs in Canada during the pandemic, there is a lack of systematic evidence synthesis on their emergency adaptations. Therefore, the objective of this study was to conduct a rapid review to systematically explore the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the delivery, resiliency, and adaptability of school food programs across Canada, offering insights to strengthen future policies, especially food food-insecure and marginalized communities, particularly during periods of school closures (e.g., during the summer holidays).

Recognizing the rapidly evolving nature of the COVID-19 pandemic and its influence on school closures, this study was designed as a systematic rapid review of newspaper articles, social media and grey literature covering information on the delivery, adaptability, and resiliency of school food programs as emergency response feeding strategies across Canada. The research question addressed by this rapid review was: For school-going children and adolescents, how did school food programs adapt during the pandemic in terms of delivery and infrastructure compared with ‘pre-pandemic’ operations, and what lessons were learned from school food programs that were sustained during the pandemic to ensure provision of nutritious meals to students. This study employed a multiple case study approach to guide our data collection, analysis, and interpretation, given the rapidly evolving nature of school food program modalities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Relevant studies were included if there were sufficient access to pertinent data in relation to the research question.

Data extraction was organized using the PICOTS framework as follows: (a) Population – school food programs provided to school-aged children and adolescents; (b) Intervention – various adaptations to school food program modalities; (c) Comparison – “pre-pandemic” school food program modalities; (d) Outcomes – The various items covered under the delivery, adaptability, and resiliency of SFP were adapted from other studies, guided by the RE-AIM framework: Reach and Effectiveness (Delivery) e.g., SFP modalities, food type and variety, method of delivery/food distribution, food procurement, participation/scope. Adoption and Implementation (Adaptability) e.g., infrastructure, changes to content (e.g., menu items, food type/variety/food distribution and procurement) of SFPs. Maintenance and Sustainability (Resiliency) e.g., concerns, challenges and successes encountered, support/beneficiaries, funding and costs and impact; (e) Time – adaptations to school food programs during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown and (f) Study design/characteristics – case studies, relevant news/webinar articles and inclusion of necessary information with respect to delivery, adaptability and resiliency. This research was guided by two frameworks: the Analysis Grid for Environments Linked to Obesity (ANGELO) (12) and the Getting to Equity (GTE) (13), selected for their complementarity towards capturing the factors impacting the delivery, adaptability, and resiliency of school food programs in Canada.

To identify potentially relevant articles for inclusion, the following electronic databases was searched: ProQuest Canadian NewStream for news articles and Social Search for social media articles. The search was supplemented by grey literature captured through targeted internet searches for news articles, as well as attendance and participation in webinars, that provided additional links to strategies addressing the adaptations of school food programs. A concept map was created to identify relevant keywords (Table 1), and the keywords were further refined with the research team and University librarian in terms of redundancy and ability to capture the relevant articles. The inclusion criteria were any case studies, news articles or webinars that were assessing school food programs (lunch, breakfast, snakes, before/after school) for school-aged children/adolescents and mentioned the delivery, adaptability, or resiliency of these programs during the COVID-19 pandemic in comparison to the regular operating schedule from the time of the public health emergency declaration and school closure announcements in Canada. Studies were excluded if they were looking at day care or early child education center food programs.

Articles were eligible if they included keywords related to school food program during the COVID-19 pandemic. Potential sources obtained from literature searches were extracted, organized, and reviewed by two team members (J.R and A.R). The first team member began by screening all potential sources for relevance. Non-relevant sources were excluded (e.g., focusing on school food program adaptations outside Canada), as were any sources that were duplicated. The second team member then reviewed the remaining eligible articles for their inclusion in the study.

The ANGELO framework was designed to assess the environmental factors impacting eating behavior or physical activity and allows for identifying which factors can be readily modified (12). It is designed for communities to identify these factors, however, can be used both at the population (e.g., Canada) and settings/sector level (e.g., schools or fast-food retails). The framework assesses macro and microenvironments, with respect to the physical, economic, political, and sociocultural aspects. Macroenvironments operate at a regional/state level and may include media, food distribution programs, food transport, and food catering services while microenvironments relate to the household/institutional level and may include settings such as the home, school, church, grocery store, and food service outlets (12). In this study, the ANGELO framework was used as a conceptual model to evaluate and assess the balance of the societal and environmental factors impacting adaptability of school food programs during the COVID-19 pandemic (Supplementary Table 1). In reviewing each article, assessors thematically categorized mention of various societal and environmental factors according to the domains of the ANGELO framework.

The Getting to Equity (GTE) framework focuses on equity-oriented obesity prevention action through four types of approaches and was used to assess the gaps in school food programs, specifically for food insecure and marginalized communities during the COVID-19 pandemic (13). The four approaches are: increasing healthy options; reducing deterrents to healthy behaviors; improving social and economic resources; and building community capacity. Increasing healthy options and reducing deterrents focus on potential policy and system interventions that could lead to improved equity, while improving social and economic resources and building on community capacity focus on individual and community resources and capacity developments (13). Specifically, this framework was used to assess the adaptability of school food programs as emergency feeding strategies with a ‘people-oriented perspective’ according to how they affect school-aged children, families, insecure/marginalized communities, other population subgroups and communities. In reviewing each article, assessors thematically categorized the adaptability of school food programs according to the various approaches of the GTE framework (Supplementary Table 2).

Both the ANGELO and GTE frameworks were used to synthesize common themes related to successes and challenges emerging across the adaptability of school food programs in Canada during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In reviewing each article, we thematically categorized mention of various societal and environmental factors according to the domains of the ANGELO and GTE frameworks. The components of each framework were used to synthesize the themes after we thematically analyzed the data using NVivo, guided by the RE-AIM framework. This involved (1) becoming familiar with the literature review/similar studies (14–16), (2) creating initial codes based on these similar studies and using the RE-AIM framework to guide the selection of themes, as relevant to the research question, designed using PICOTS, and (3) Thematically organizing the data.

Data obtained from the search results were extracted and organized into the following categories by each city and province: Reach and Effectiveness (Delivery): SFP modalities (e.g., food kits, gift cards and type of foods), food type and variety, method of delivery/food distribution (e.g., delivery/pickup time), food procurement, participation/scope (e.g., students, families, insecure/marginalized populations). Adoption and Implementation (Adaptability): infrastructure, changes to content/modifications (e.g., menu items, food type/variety/food distribution and procurement) of SFPs (e.g., electronic messages, fund raisers etc.). Maintenance and Sustainability (Resiliency): concerns, challenges and successes encountered, support/beneficiaries, funding and costs and impact. Information was collected and thematically categorized and compiled by the two team members. In case of discrepancy, information was reviewed by a third team member for thematic categorization.

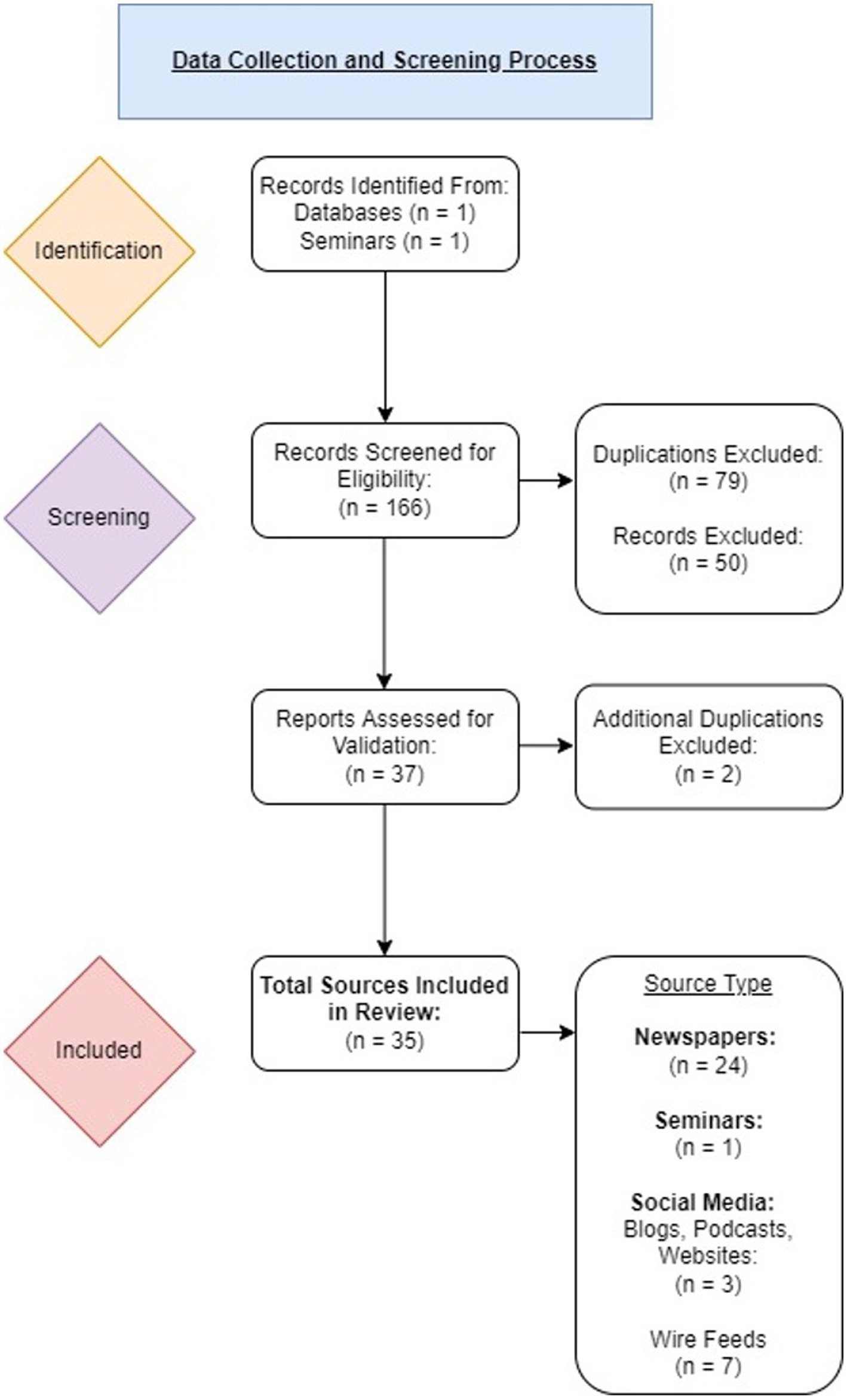

A total of 166 citations were initially retrieved. Of these, 165 were obtained from ProQuest Canadian Newsstream. The 1 remaining source was obtained from a webinar Nourishing students: How Ontario SNP’s are adapting in a time of COVID hosted by Student Nutrition Ontario and sustain Ontario on June 1st 2021.Upon review of the 166 collected citations, 81 duplicated sources and 50 sources deemed to be ineligible for the purposes of this review were excluded from further analysis.

A total of 35 unique sources were validated and included in this review. The 35 sources consisted of different source types such as newspapers (n = 24), seminars (n = 1), and social media sources comprised of blogs, podcasts, and websites (n = 3) and wire feeds (n = 7). Source type was determined using the classifications obtained from ProQuest (excluding the seminar as ProQuest was not used to find this source) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flowchart of data collection and screening process: A total of 166 citations were retrieved. Thirty five articles from 7 provinces and territories across Canada fulfilled the eligibility criteria and were included in this review. Ten of the included articles were from social media sources.

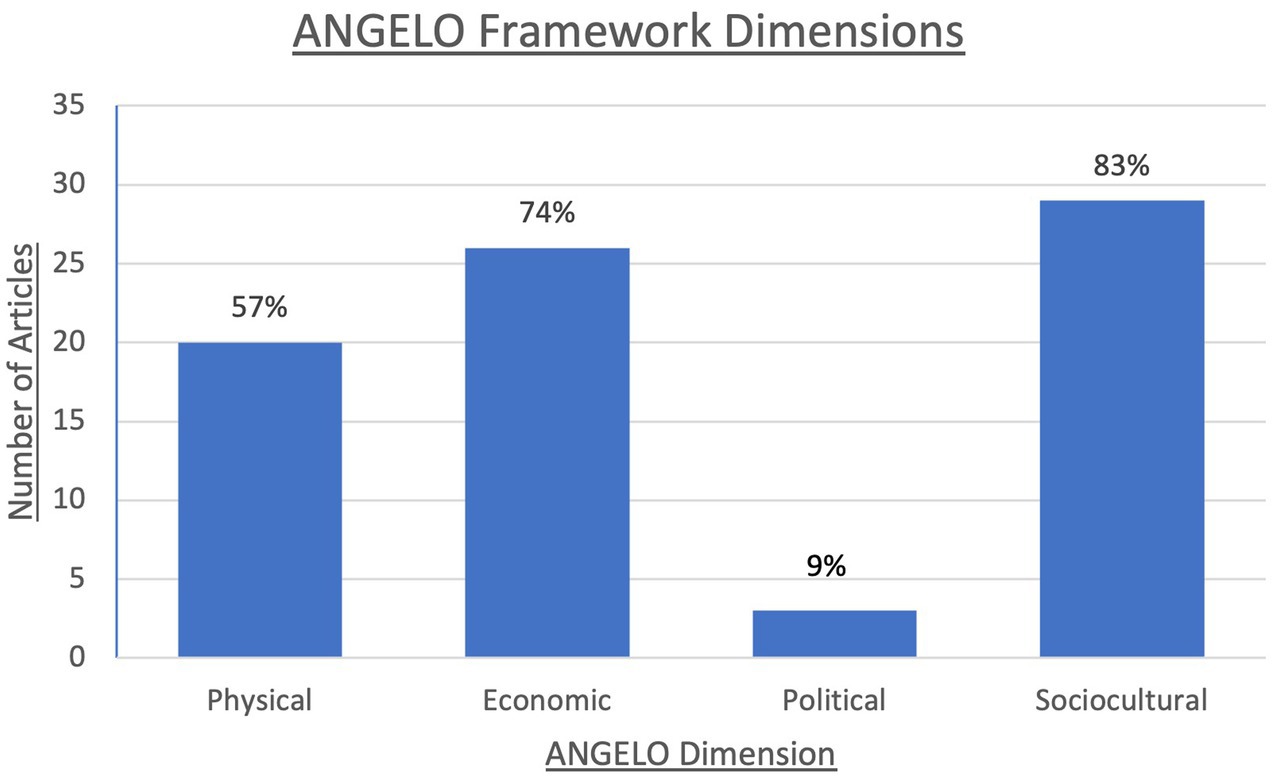

The main dimensions of the ANGELO framework captured by the 35 sources were related to sociocultural (n = 29), physical (n = 26), or economic (n = 20) environments. There was a notable lack of school food program adaptations which incorporated the political environment (n = 3). (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Analysis Grid for Environments Linked to Obesity (ANGELO) framework dimensions captured in included sources: Number of sources (out of total n = 35) which captured each respective dimension of the ANGELO framework (12). Examples of physical environment components include food availability, accessibility, and distribution. The economic environment covers aspects such as food costs, price gouging, and available financial resources (e.g., monetary donations, fundraisers) for both SFPs and families in need. The political environment includes governmental interventions such as the creation of new laws, regulations, and funding changes. The sociocultural environment focuses on the attitudes, values, and collaborations of the community and society at large. Abbreviations: ANGELO, Analysis Grid for Environments Linked to Obesity; SFP, School Food Program.

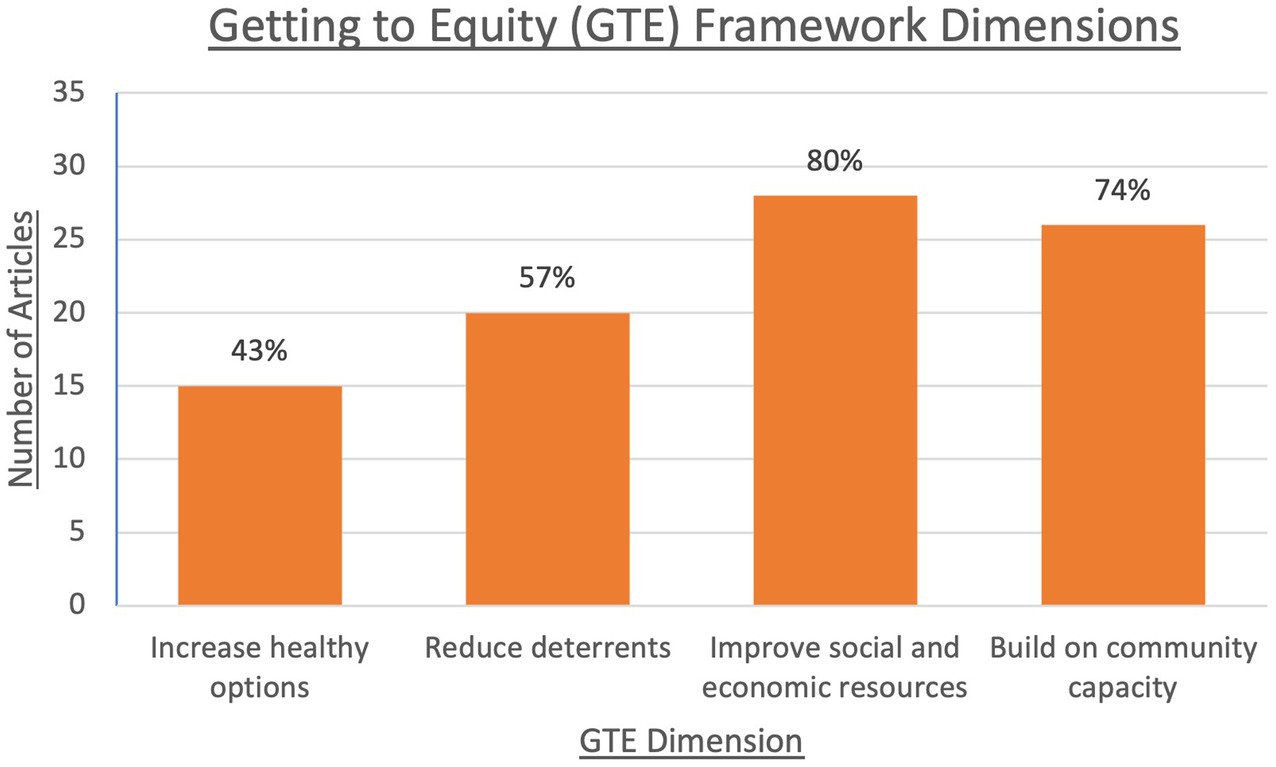

When examined using a basis of the GTE framework, the 35 included sources predominantly focused on improving social and economic resources (n = 28) and building community capacity (n = 26). Reducing deterrents was also a focus of the included articles (n = 20), with the least number of articles focusing on increasing healthy options (n = 15) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Getting to Equity (GTE) framework dimensions captured in included sources: Number of sources (out of total n = 35) which captured each respective dimension of the GTE framework (13). Examples of increasing healthy options includes the distribution of free meal kits and prepared meals which follow existing SFP guidelines, as well as meal kit delivery. Reducing deterrents involves mechanisms such as providing food at accessible locations, following COVID-19 guidelines, and non-discriminatory outreach to all students and families. Improving social and economic resources can occur through the creation of new SFPs during COVID-19, along with increased amounts of funding and donations (e.g., monetary, food, other supplies) to SFPs or directly towards vulnerable students and their families. Building on community capacity can be achieved through collaborations between community members to help those in need, using community resources in beneficial ways, and creating new partnerships to provide greater aid to those in need (e.g., working with larger organizations and companies). Abbreviations: GTE, Getting To Equity, SFP, school food program.

In terms of modality, novel approaches to the delivery of school food programs included new initiatives or adjustments to old approaches, community initiatives and increased financial support. Programs in several provinces implemented the provision of food kits and gift cards to students, with some even offering home delivery. Community initiatives included setting up shelters or other public locations to provide meals and food kits to students and their families, as well as organizing local events to increase awareness on food insecurity of local families and raise funds. Additionally, with the support of non- governmental organizations (NGOs) and school food program-allocated funds from governments (federal, provincial/territorial), there was greater capacity to maintain emergency food distribution in certain regions (e.g., Nunavut) (Table 2).

During the pandemic, several school food programs focused on vulnerable students and families, particularly those identified as high-risk of facing food insecurity and/or belonging to marginalized communities (e.g., those with language barriers, minority groups). Most programs adapted to provide meals on a weekly basis, with some in the provinces of New Brunswick and Ontario giving daily options (Table 2).

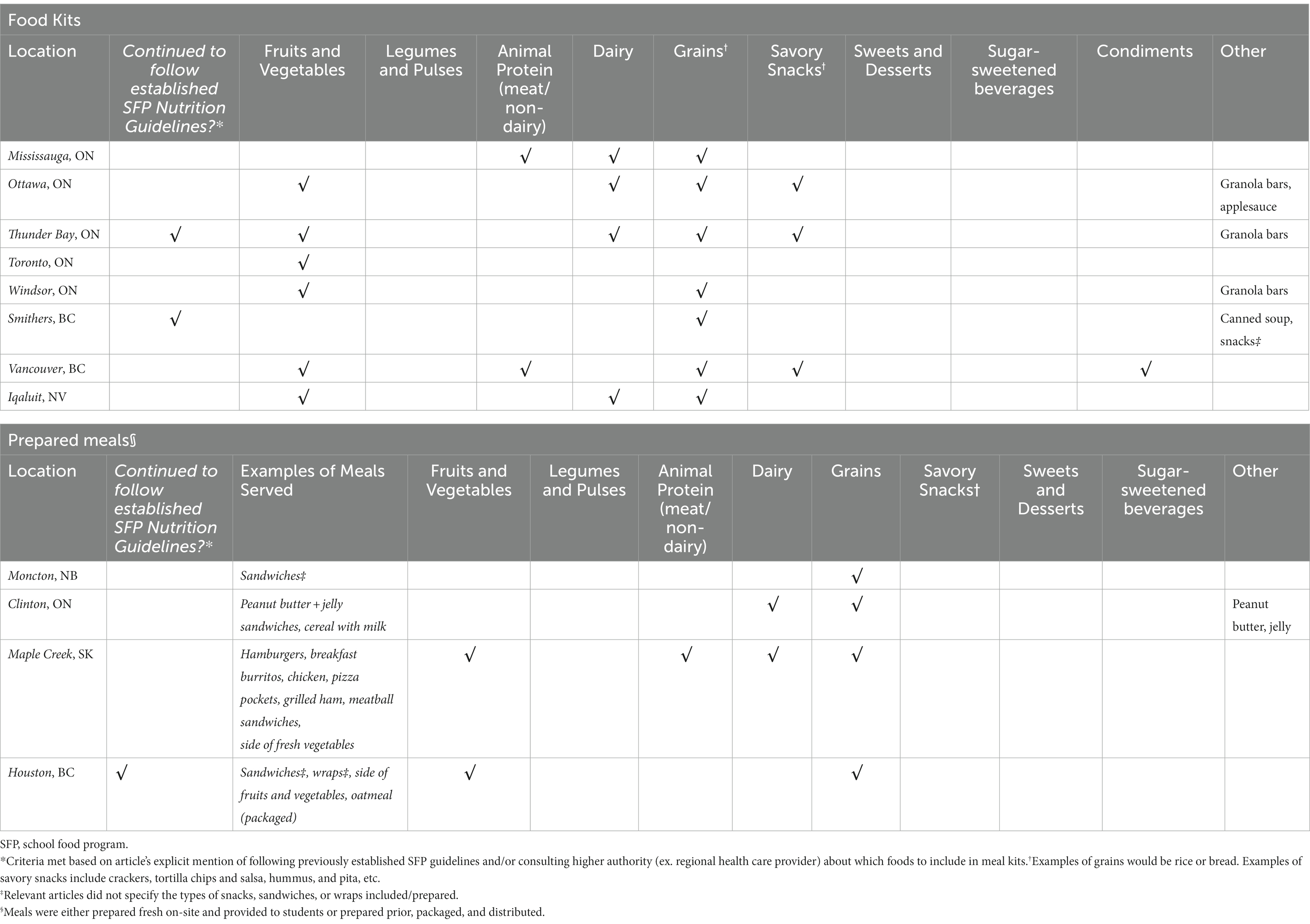

For the programs that adapted to provide food kits, the majority of the food kits included some form of fruit, vegetables, dairy and grain products. A few also incorporated granola bars or savory snacks such as crackers. There was none or very limited provision of legumes and pulses, animal protein, sweets and desserts and sugar-sweetened beverages. Only two articles indicated following nutritional guidelines established for the SFP (Table 3).

Table 3. Summary of components included in food kits and prepared meals following School Food Programs modifications in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

For the programs that indicated provision of prepared meals, the majority incorporated dairy and grain products as components of meals, while only few indicated the inclusion of animal products other than dairy, fruits, and vegetables (Table 3).

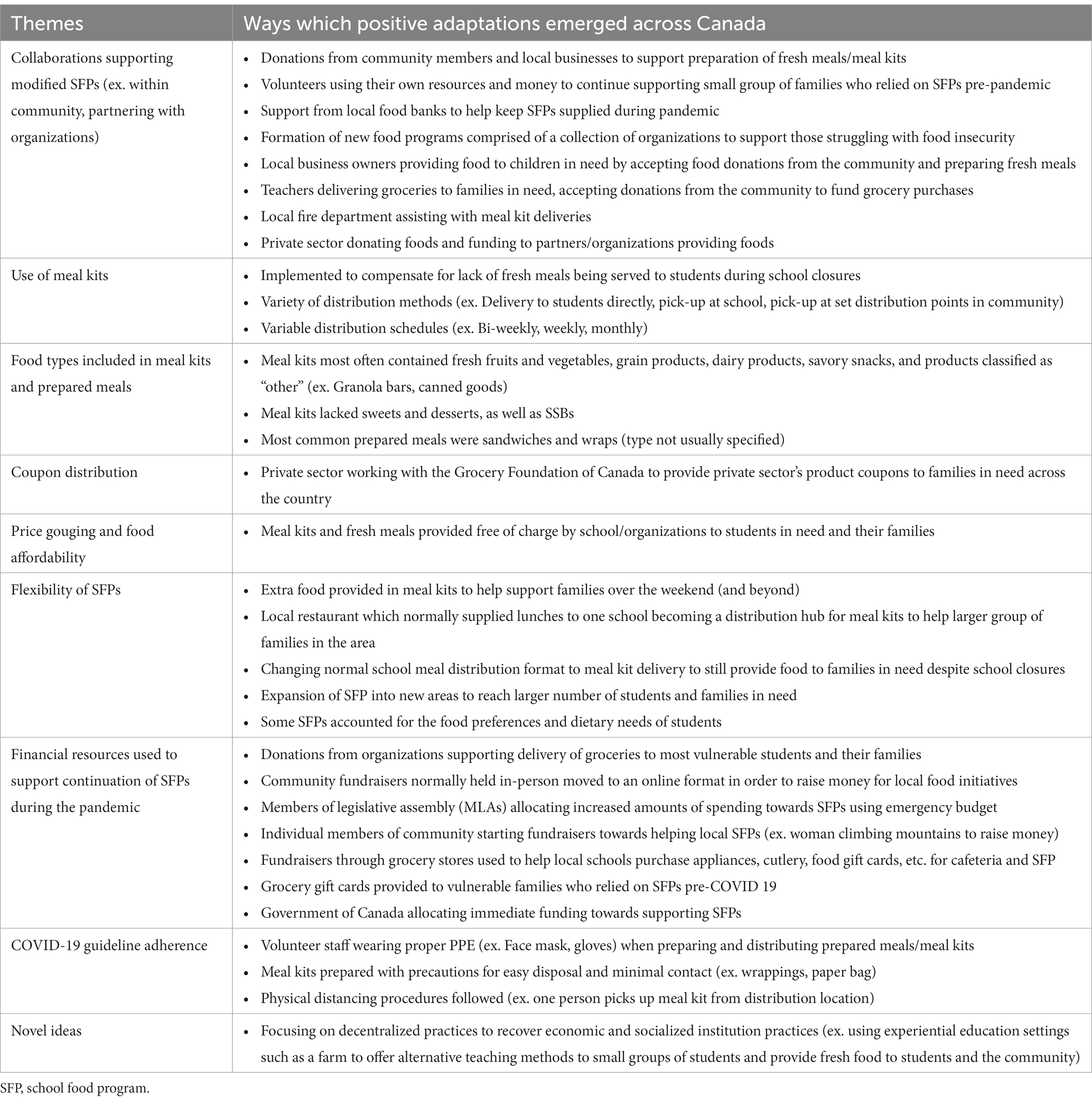

One of the factors that was repeatedly mentioned as facilitating the continuation of school food programs during the pandemic was leveraging existing community partnerships and distribution channels. For example, several articles highlighted the collaborative approach that was helpful in swiftly altering the mode of distribution and provision of nutritious meals and snacks, particularly to those families and children in need. This approach was further facilitated by the development of new partnerships with local businesses, which allowed for the purchase of food from local farmers whose distribution chains had been disrupted and local restaurants taking on the responsibility to provide fresh meals to students after losing regular business. Additionally, the flexibility of certain school food programs led to modifications like expansion in food provision range to reach a larger number of children and families, including extra food in meal kits to help support families over the weekend, and transforming restaurants which supplied lunches to one school pre-pandemic into distribution hubs to reach a larger group of families in the area (Table 4).

Table 4. Overall summary of positive adaptions made to the School Food Programs in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

A shared barrier among the school food programs were the increased expenses involved with the procurement of food and meals, and additional operating costs related to adhering to COVID-19 protocols. Challenges faced when adapting school food programs also included a heavy reliance on community donations and volunteers, as well as the use of electronic devices and social media to reach families and children in need, although not all families had internet access. Several school food programs continued providing healthy meals during the pandemic without the provision of additional resources. In addition, they faced issues such as limited food supplies and interruptions to food transportation (Table 5).

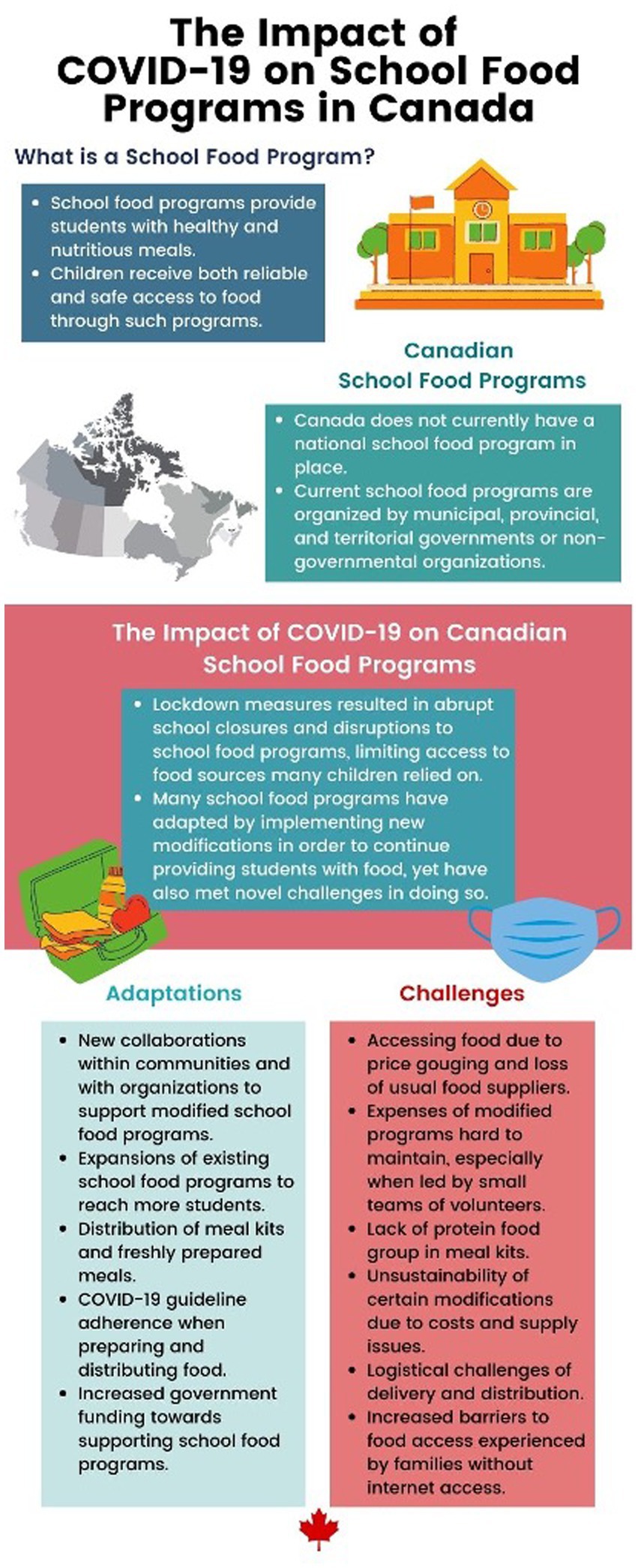

The findings from this study illustrate how voluntary school food programs across Canada modified and adapted feeding strategies during school closures and the facilitators and challenges they faced in delivering essential provisions to school-aged children, particularly those who were the most vulnerable, which resulted from the COVID-19 pandemic (Figure 4). There was an increased emphasis on community engagement, identified as a key component in facilitating provision of foods to children. However, despite the strengthened efforts among community members, a lack of or limited funds allocated for emergency feeding made delivery of foods challenging, as related to maintenance and sustainability.

Figure 4. Summary on Canadian school food programs and examples of different adaptations and challenges: Summary of the main adaptations and challenges faced by school food programs across Canada in response to the COVID-19 pandemic as evident through this systematic rapid review.

As shown from the results of this study, these programs devised and implemented new modalities, which included a mixture of meal provision strategies such as meal pick up at a central location or direct delivery of food kits/prepared meals or gift cards to use in grocery stores. Results from other countries such as the US, Europe or Latin America assessing emergency feeding response indicated similar adaptations (e.g., food kits/ food vouchers) to feeding modalities (14, 17, 18). The results from this study on types of modalities are in alignment with another Canadian study examining the breadth of school food programming; indicating the provision of meals (e.g., breakfast), food boxes and gift cards to sustain school food programming during school closures (16). Direct delivery of food kits/prepared meals or specified pick-up locations ensured student food accessibility, particularly for those who may have limitations accessing these locations via public/personal transport methods. These adaptations to program accessibility can also benefit students with food provision during the ‘summer’ months or when schools are not in session, particularly for students receiving free or reduced-priced meals during the school year. Recent studies have incorporated spatial analyses to assess school meal accessibility related to geographic opportunity, finding that meal distribution sites were often located in larger high poverty areas and areas with a higher proportion of visible minorities (19–21).

Increased outreach (e.g., through local events) and expansion of existing programs (to those outside the community via internet/social media campaigns) also helped improve student food access, as captured by the ANGELO framework of sociocultural factors and GTE framework of building community capacity. Considering the associated risks to student health and well-being due to disruptions in food access, particularly students from vulnerable groups who may lack other nutritious options, future research in Canada can benefit from examining proximity to food access points in relation to factors such as race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status.

The development and effectiveness of these new modalities depended on resource availability and logistical navigation for acquiring and distributing foods with an emphasis on securing funds for sustainability. Support from NGOs, private organizations and/or governmental support was identified as contributing to the maintenance of these emergency food distributions, particularly in regions that are difficult to access (e.g., Nunavut). The modifications in school food programs reflected an increased emphasis on improving social and economic resources as captured by GTE and physical/economic environments aspects as captured by ANGELO. The emphasis on adequate and sustained resources has also been echoed by school-level program volunteers to ensure program feasibility and fidelity (22). These resources not only indicate a need for more staff and enhanced funding but also for resources to train and support staff (e.g., educational workshops to handle food waste or food for large numbers of children) (22).

Considering the patchwork of programming and multi-modality strategies as adaptations in various regions across Canada, it is unclear whether one method of modality is preferred, feasible or functional over another and how they might be associated with contextual factors such as stigma. A 2017 study investigating using food vouchers or free daily lunch (to reduce food insecurity) found the daily lunch method was preferred by many families, with less stigma associated with this method in comparison to food vouchers (23). However, use of a particular modality is likely community specific as factors identified in this study, such as accessibility and reach, are likely to play a role in their success.

Similar to the response by other countries (14, 17, 18), many organizations considered alternative innovative strategies to continue meal delivery. For example, distribution sites such as local community centers, places of worship and other public institutions were used to maximize access. Home delivery was another innovative approach with a high uptake in neighborhoods and for hard-to-reach areas. This suggests the potential to expand the school food programs beyond the traditional modes of delivery, for school-aged children in remote/hard-to-access areas and for when schools are not in session. Similar benefits have been shown in other studies indicating that relaxing restrictions or expanding locations of free meal sites can increase child access to meals during expected and unexpected disruptions to programs and continue to ensure access to nutritious food (24). In many areas, school meals were extended beyond school-aged children to unhoused individuals/families, those relying on food banks, food insecure families and other vulnerable population groups.

Collectively, this suggests that cross-sectoral collaborations to serve children and families can help strengthen community engagement and local partnerships to resourcefully deploy feeding strategies across various population groups, reaching the most at-risk populations. The results from this study are similar to a case study showing that student nutrition programs rich in partnerships enables the staff to pivot and respond efficiently and quickly to the lockdown restrictions (25). Additional studies have also demonstrated the importance of community/multisectoral partnerships in the provision of local, healthy, and traditional foods for schools (26, 27). Importantly, such partnerships have potential for long-term sustainability and maintenance of school food programs.

Despite logistical challenges, some of the programs identified aimed to provide foods as recommended by 2007 Canada’s Food Guide, e.g., including some form of vegetables, fruits, dairy and grain products. However, the challenges of a decreased food supply, price gouging, and changes to normal program delivery impacted the provision of fresh foods and led to increased provision of processed shelf-stable foods that are typically high in discretionary nutrients. Difficulties related to following recommended school food program guidelines were likely related to challenges obtaining fresh food and desire to limit food perishing as much as possible. This is also made evident through the lack of articles which reflected the GTE framework dimension of increasing healthy options. Additionally, food accessibility for children with allergies and/or certain dietary restrictions was more difficult due to the decreased variety of foods available in meal kits and limited options of prepared meals due to indicated challenges. Other countries also reported similar challenges in the provision of healthy foods (14, 17, 18). For example, in UK, media reports showed that many food parcels/kits were inadequate and did not meet school food standards with parents criticizing a lack of fruits and vegetables and inadequate portion sizes (28).

Several studies have indicated that meals offered through school food programs can make substantial contributions in helping children meet their dietary recommendations (29–31), with research indicating consumption of school meals positively relating to child intake of key food groups (e.g., school food participants were more likely than nonparticipants to consume milk, fruit, vegetables and less likely to consume desserts and snack items) (32, 33). Canada’s Food Guide stresses the importance of consuming products with healthy fats and limiting highly processed foods (34), thus continued efforts are needed to ensure school meals offered in Canadian schools meet nutrition standards. In addition, beyond food accessibility and availability, children may also benefit from nutrition education programs to facilitate adoption of better food choices and encourage healthy food-related behaviors (35).

In addition to challenges associated with the quality of foods, other barriers that were commonly mentioned included difficulties in reaching vulnerable families, financial constraints/available funds and limited government fund allocation and involvement in emergency feeding. Students without internet access may have faced limitations in participating in programs relying on online communication. Limited funding raised uncertainties about the sustainability of volunteer-run food programs, impacting the number of families assisted weekly. There was a notable lack of political intervention (e.g., few instances of increased government funding) as captured by the ANGELO framework (the ‘political’ environment factor was only captured by 3 sources). This highlights a critical need for increased government support of school food programs and feeding strategies during emergencies/school closures; this increased support would also help decrease uncertainties/unknowns associated with school food program reliance on donations and volunteers and would also help ensure that students/families, particularly those in need, have reliable access to healthy food for defined or prolonged periods, mitigating stress associated with food and nutrition insecurity (15).

Canada is the only Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) country without a school food program. In the UK, for example, which has a national school food program, schools were required to adapt their approach to school meals due to COVID-19 to ensure support for eligible children (15, 17) and in the US, which also has a national school food program, United States Department of Agriculture waivers were authorized for provision of school meals (18, 24). Despite not having a national school feeding strategy, various approaches were adapted across Canada to reach school-aged children, particularly those in greatest need. These findings highlight key adaptations to school food programs that played a vital role in responding to student and family food needs and underscore the challenges of feeding children during emergency situations or when schools are closed for prolonged periods.

Unhealthy dietary behaviors are a major preventable risk factor for obesity. Canadian children have poor diet quality (36, 37), consuming diets that are high in sodium, sugar and saturated fat ((36)). Considering that schools are an important setting to address childhood obesity and support healthy eating behaviors (30, 38), implementation of school-based nutrition interventions to create healthy school food environments can benefit student health and well-being. School food programs in Canada continue to be provided by a patchwork of programming and could benefit from a comprehensive and standardized approach that addresses nutritional standards, accessibility and equitable distribution to ensure all students have access to healthy and balanced meals (39).

Considering the national and global momentum on the importance of school food programs for meeting nutritional needs and ensuring access to healthy foods for children (40, 41), the results from this study can be contextualized to highlight lessons learned for future considerations for school food program implementation in Canada and during future emergencies and/or during school closures, as follows: (1) establishment of national school food guidelines to guide the nutritional quality of foods, (2) allocation of funds/resources dedicated to provision of school feeding strategies, and (3) capacity building for strengthening community engagement and local partnerships.

Recommendations to reduce intake of foods with nutrients-of-concern (sodium, sugar and saturated fat) and processed foods are recommended by health organizations worldwide, given the increase in overweight, obesity and diet-related non-communicable diseases (42). The current study indicated, that although there were attempts made at provision of foods from various food groups including fruits and vegetables, limited articles mentioned following nutritional guidelines when determining the types of food provided to children (also given the constraints with resourcing, price increase of foods, and distribution/delivery etc.). Nutritional guidelines are critical to avoid providing less healthful, nutrient-poor foods in emergency programs. Previous studies have indicated prevalence of high-calorie, low nutritional quality foods in such assistance efforts (14, 43). Additionally, self-stable ultra-processed foods, easily pre-packaged for individual consumption, may be provided without assessing their nutritional adequacy in emergency responses (14, 43). Considering the limited literature on the nutritional quality of foods provided during emergencies in high-income countries, there is a critical need for national nutritional guidelines for school feeding programs that also address provision during, school closures, and future emergencies.

Limited funds and resources hindered schools from sustaining food provision during COVID-19 related school closures, despite innovative strategies, community engagement and donations. The patchwork of funding coming from various sources and uncertainty surrounding the continuation of funds led to cessation of many feeding adaptations shortly after being initiated, emphasizing the need for a sustainable funding structure for school food programs (44). This challenge extends beyond Canada, as budget constraints were observed globally and noted as a significant barrier to the operability of feeding strategies during the pandemic in other countries (14, 17), highlighting the political aspects of the ANGELO domain with inconsistent funding allocation.

Adapting school feeding strategies successfully involved community engagement and forming local partnerships for food resourcing and access. Collaborations, such as volunteers working with local food banks and/or community organizations, played a vital role in the adaptability, sustainability, and resiliency of school feeding strategies. Future design of school feeding strategies should prioritize partnerships between local community organizations and government support to enhance community capacity. Previous studies from the US and Latin American emphasize the importance of local partnerships as key to the success for the adaptability of school feeding strategies (14, 18). Strengthening community engagement may also contribute to the success of complementary community food security responses to reach the most vulnerable.

This study is limited by using case selection and non-traditional literature sources for information on adaptability of school feeding strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic school closures, particularly, as many organizations diverted to use of social media to raise awareness and information about feeding strategies. Data from news articles, gathered through rapid assessment, may not capture specific challenges faced by organizations and/or communities. This study may also be limited in identifying the full breadth of feeding strategies reaching marginalized communities. Nonetheless, the findings highlight challenges and facilitators, informing future considerations. Comparisons with school food programs in other countries such as the US or UK is limited due to Canada lacking a national school feeding strategy. As such, certain aspects of this research, e.g., whether the grocery store gift cards were used for food only is beyond the scope of this study.

This study is the first of its kind in Canada to capture the adaptability and resiliency of various school food programs by province and city during an emergency and provides an overview of the challenges and facilitators faced in adapting school food programs. Furthermore, considering the rapid assessment approach, this study applied validated frameworks (ANGELO AND GTE) that assessed food environments, to give a snapshot of where future considerations could focus for emergency and/or out-of-school feeding strategies.

The findings highlight key recommendations that can help inform government and civil society to more readily face the challenges associated with school feeding during similar emergency periods and/or during sustained periods of school closure (i.e., during summertime). Drawing from the lessons learned, the findings underscore the importance of establishing national nutrition guidelines to meet nutritional needs of children, allocation of immediate/emergency funds to sustain the provision of school food programs and supporting strengthening of community efforts to increase the accessibility and affordability of healthy foods within communities.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

MA: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AR: Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JR: Formal analysis, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CM: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. DS: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. VM: Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Feeding Kids, Nourishing Minds is funded by a $2 million investment from President’s Choice Children’s Charity, and by the Joannah & Brian Lawson Centre for Child Nutrition at the University of Toronto. The funding sponsor was not involved in the design, conduct or analysis of the research described.

MA, AR, and JR were partially funded by the Feeding Kids, Nourishing Minds School-based Nutrition Research Initiative Graduate Award/Fellowship and/or Catalyst Fund. VM has received funding from the Canada Research Chairs Program; Connaught New Researcher Award, University of Toronto; The Joannah and Brian Lawson Centre for Child Nutrition, University of Toronto; Temerty Faculty of Medicine Pathway Grant, University of Toronto; Canada Foundation for Innovation; and the Ontario Research Fund.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1296620/full#supplementary-material

1. World Health Organization(a) . Internet Avaialble at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200311-sitrep-51-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=1ba62e57_10 (Accessed May 8, 2020).

2. Schanzebach DPA . Internet Avaialble at: https://www.ipr.northwestern.edu/documents/reports/ipr-rapid-research-reports-pulse-hh-data-10-june-2020.pdf. (Accessed January 17, 2022).

3. Poole, MK, Fleischhacker, SE, and Bleich, SN. Addressing child hunger when school is closed - considerations during the pandemic and beyond. N Engl J Med. (2021) 384:e35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2033629

4. Charlebois, S, Somogyi, S, Taylor, G, Jackson, E, and Music, J. Internet Available at: https://www.dal.ca/sites/agri-food/research/canada-s-food-price-report---revised-updates.html (Accessed March 31, 2020).

5. Angus Reid Institute . Internet: Available at: http://angusreid.org/rising-food-prices/ (Accessed April 4, 2016).

6. Kinsey, EW, Hecht, AA, Dunn, CG, Levi, R, Read, MA, Smith, C, et al. School closures during COVID-19: opportunities for innovation in meal service. Am J Public Health. (2020) 110:1635–43. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305875

7. Tugault-Lafleur, CN, Black, JL, and Barr, SI. Examining school-day dietary intakes among Canadian children. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. (2017) 42:1064–72. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2017-0125

8. The Coalition for Healthy School Foods . Internet Available at: https://www.healthyschoolfood.ca/post/school-food-in-the-g7-the-time-is-ripe-for-canada-to-catch-up (Accessed August 20, 2020).

9. Roberts, E, McLeod, N, Montemurro, G, Veugelers, PJ, Gleddie, D, and Storey, KE. Implementing comprehensive school health in Alberta, Canada: the principal's role. Health Promot Int. (2016) 31:915–24. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dav083

10. Veugelers, PJ, and Schwartz, ME. Comprehensive school health in Canada. Can J Public Health. (2010) 101:S5–8. doi: 10.1007/BF03405617

11. Health Canada . (2022). Internet Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/programs/school-food/consultation-school-food/discussion-paper.html (Accessed November 11, 2022).

12. Swinburn, B, Egger, G, and Raza, F. Dissecting obesogenic environments: the development and application of a framework for identifying and prioritizing environmental interventions for obesity. Prev Med. (1999) 29:563–70. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1999.0585

13. Kumanyika, S. (2017). Internet Available at: https://nam.edu/getting-to-equity-in-obesity-prevention-a-new-framework/ (Accessed November 10, 2022).

14. Colon-Ramos, U, Monge-Rojas, R, Weil, JG, Olivares, GF, Zavala, R, Grilo, MF, et al. Lessons learned for emergency feeding during modifications to 11 school feeding programs in Latin America and the Caribbean during the COVID-19 pandemic. Food Nutr Bull. (2022) 43:84–03. doi: 10.1177/03795721211062371

15. Patten, EV, Spruance, L, Vaterlaus, JM, Jones, M, and Beckstead, E. Disaster management and school nutrition: a qualitative study of emergency feeding during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Acad Nutr Diet. (2021) 121:1441–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2021.04.012

16. Guptaa, S, Engler-Stringera, R, Ruetz, A, and McKennac, ML. School food programming across Canada during the COVID 19 pandemic: program reach and modalities. J Hunger Environ Nutr. (2022) 18:343–55. doi: 10.1080/19320248.2022.2105185

17. McIntyre, RL, Adamson, AJ, Nelson, M, Woodside, J, Beattie, S, and Spence, S. Changes and differences in school food standards (2010-2021) and free school meal provision during COVID-19 across the UK: potential implications for children's diets. Nutr Bull. (2022) 47:230–45. doi: 10.1111/nbu.12556

18. Jablonski, BBR, Casnovsky, J, Clark, JK, Cleary, R, Feingold, B, Freedman, D, et al. Emergency food provision for children and families during the COVID-19 pandemic: examples from five U.S. Cities Appl Econ Perspect Policy. (2021) 43:169–84. doi: 10.1002/aepp.13096

19. Miller, DP . Accessibility of summer meals and the food insecurity of low-income households with children. Public Health Nutr. (2016) 19:2079–89. doi: 10.1017/S1368980016000033

20. McLoughlin, GM, McCarthy, JA, McGuirt, JT, Singleton, CR, Dunn, CG, and Gadhoke, P. Addressing food insecurity through a health equity Lens: a case study of large Urban School districts during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Urban Health. (2020) 97:759–75. doi: 10.1007/s11524-020-00476-0

21. Jabbari, J, Chun, Y, Nandan, P, McDermott, L, Frank, T, Moreland-Russell, S, et al. How did school meal access change during the COVID-19 pandemic? A two-step floating catchment area analysis of a large metropolitan area. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:11350–67. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182111350

22. Ismail, MR, Gilliland, JA, Matthews, JI, and Battram, DS. School-level perspectives of the Ontario student nutrition program. Children (Basel). (2022) 9:117–87. doi: 10.3390/children9020177

23. Dalma, A, Zota, D, Kouvari, M, Kastorini, CM, Veloudaki, A, Ellis-Montalban, P, et al. Daily distribution of free healthy school meals or food-voucher intervention? Perceptions and attitudes of parents and educators. Appetite. (2018) 120:627–35. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2017.10.025

24. Toossi, S . The distribution of and access to free meal sites serving school aged children during the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from Texas. J Sch Health. (2023) 93:395–01. doi: 10.1111/josh.13303

25. Noyes, N . COVID-19 and school food: the impact of the early stages of the coronavirus pandemic on student nutrition programs in Ontario. J Agric Food Syst Commun Dev. (2021) 10:197–01. doi: 10.5304/jafscd.2021.102.049

26. McEachern, LW, Yessis, J, Yovanovich, J, Crack, S, Zupko, B, Valaitis, R, et al.. Implementation of the learning circle: local food to school initiative in the island communities of Haida Gwaii, British Columbia, Canada-a descriptive case study. Curr Dev Nutr (2022). 6: nzac090. doi: 10.1093/cdn/nzac090

27. Beets, MW, Tilley, F, Turner-McGrievy, G, Weaver, RG, and Jones, S. Community partnership to address snack quality and cost in after-school programs. J Sch Health. (2014) 84:543–8. doi: 10.1111/josh.12175

28. The Guardian . (2021). Internet Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/education/2021/jan/12/what-am-i-supposed-to-make-with-this-uk-parents-on-schools-meagre-food-parcels (Accessed July 15, 2021).

29. Story, M, Kaphingst, KM, and French, S. The role of schools in obesity prevention. Futur Child. (2006) 16:109–42. doi: 10.1353/foc.2006.0007

30. Briefel, RR, Wilson, A, and Gleason, PM. Consumption of low-nutrient, energy-dense foods and beverages at school, home, and other locations among school lunch participants and nonparticipants. J Am Diet Assoc. (2009) 109:S79–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.10.064

31. Micha, R, Karageorgou, D, Bakogianni, I, Trichia, E, Whitsel, LP, Story, M, et al. Effectiveness of school food environment policies on children's dietary behaviors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. (2018) 13:e0194555. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194555

32. Condon, EM, Crepinsek, MK, and Fox, MK. School meals: types of foods offered to and consumed by children at lunch and breakfast. J Am Diet Assoc. (2009) 109:S67–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.10.062

33. Mohammadi, S, Su, TT, Jalaludin, MY, Dahlui, M, Azmi Mohamed, MN, Papadaki, A, et al. School-based intervention to improve healthy eating practices among Malaysian adolescents: a feasibility study protocol. Front Public Health. (2020) 8:549637. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.549637

34. Health Canada . (2023). Internet Available at: https://food-guide.canada.ca/en/ (Accessed January 24, 2019).

35. Rasheed, M . Promoting nutritional education in primary school children. Br J Nurs. (2023) 32:S14–8. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2023.32.8.S14

36. Ng A AM and L'Abbe MR . (2021). Internet. Avaialble at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/357244965_Nutrient_Intakes_of_Canadian_Children_and_Adolescents_Results_from_the_Canadian_Community_Health_Survey_CCHS_2015_-_Nutrition_Public_Use_Microdata_Files.

37. Hack, S, Jessri, M, and L'Abbe, MR. Nutritional quality of the food choices of Canadian children. BMC Nutr. (2021) 7:16. doi: 10.1186/s40795-021-00422-6

38. Campbell, KJ, Crawford, DA, Salmon, J, Carver, A, Garnett, SP, and Baur, LA. Associations between the home food environment and obesity-promoting eating behaviors in adolescence. Obesity (Silver Spring). (2007) 15:719–30. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.553

39. Haines, J, and Ruetz, A. (2020). Internet Available at: https://arrellfoodinstitute.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/SchoolFoodNutrition_Final_RS.pdf (Accessed November 28, 2023).

40. Government of Canada . (2023). Internet Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/programs/school-food/consultation-school-food/what-we-heard-report-2023.html (Accessed November 27, 2023).

41. World Health Organization(b) . (2021). Internet Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240025646 (Accessed November 27, 2021).

42. World Health Organization(c) . (2013). Internet Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/94384/1/9789241506236_eng.pdf?ua=1 (Accessed December 10, 2018).

43. Colon-Ramos, U, Roess, AA, Robien, K, Marghella, PD, Waldman, RJ, and Merrigan, KA. Foods distributed during Federal Disaster Relief Response in Puerto Rico after hurricane Maria did not fully meet Federal Nutrition Recommendations. J Acad Nutr Diet. (2019) 119:1903–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2019.03.015

Keywords: Canada, COVID-19, challenges, children, school food programs, nutrition programs

Citation: Ahmed M, Richardson A, Riad J, McPherson C, Sellen DW and Malik VS (2024) Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the adaptability and resiliency of school food programs across Canada. Front. Public Health. 11:1296620. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1296620

Received: 19 September 2023; Accepted: 06 December 2023;

Published: 03 January 2024.

Edited by:

Shooka Mohammadi, University of Malaya, MalaysiaReviewed by:

Ai Kah Ng, University of Malaya, MalaysiaCopyright © 2024 Ahmed, Richardson, Riad, McPherson, Sellen and Malik. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Vasanti S. Malik, dmFzYW50aS5tYWxpa0B1dG9yb250by5jYQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.