- Department of Aging Service and Management, School of Aging Service and Management, Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine, Nanjing, China

Objective: This study aims to identify factors influencing university students' participation in time banking volunteer services for older adults and provides evidence to promote the involvement.

Methods: Conducted in November 2022, we utilized a convenience sampling method to recruit students from the School of Aging Service and Management at Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine, China. Data was collected through an online questionnaire focusing on various aspects related to time banking volunteer services for older adults. Factor analysis was employed to extract variables, and logistic regression was applied to identify key determinants.

Results: A significant majority (82.67%) of participants expressed willingness to engage in volunteer services for older adults. Factor analysis uncovered six influential factors explaining 62.55% of the variance. Logistic regression highlighted four key determinants of students' willingness: value judgment (OR = 4.392, CI = 2.897–6.658), social support (OR = 1.262, CI = 0.938–1.975), social influence (OR = 1.777, CI = 1.598–3.799), and socioeconomic conditions (OR = 1.174, CI = 1.891–3.046).

Conclusion: To foster sustainability and continuous time banking among university students majoring in aging service and management, a multifaceted support involving governmental, social, and university is recommended.

1 Introduction

Time banking offers a unique way for people in a community to exchange services using time instead of money. In this system, 1 h of any service is equivalent to one time credit. Individuals can join a time bank either through a local group or online, listing both their skills and needs. When a member provides a service, they earn credits, which can be used to receive services from others. Time banks keep track of these credits. Participation is voluntary, allowing members to choose the services they wish to offer and receive (1, 2). With the global older adults population projected to increase from 6.9% in 2000 to 19.3% by 2050, the demand for care services is set to escalate. China has the world's largest older adults population. The 2019 national census data reveals that the population aged 65 and over in China has reached 176 million, representing over one-fifth of the global population in this age group. This large and rapidly increasing older adults population poses significant economic and social challenges for China. Time banking encourages younger individuals to invest their time in various community services, earning credits that they can redeem for their own future needs. This approach can relieve the pressure on existing care services by facilitating informal social support and engaging socially excluded groups in community activities, thereby promoting social inclusion (3). Furthermore, time banking fosters an alternative, community-focused economic model where participants both contribute and benefit. This system highlights the value of collective efforts and a community-based lifestyle, achieved through the exchange of time and expertise (4). Such practices enhance the sense of community involvement, particularly benefiting newcomers or those living in isolation (5). Feeling connected, a key aspect of social capital, is crucial in improving overall wellbeing. Time banking proves particularly beneficial for the older adults, low-income individuals, and those living alone, as it boosts both physical health and a sense of belonging to a community (6–8). The China Time Bank Development Research Report indicates that time banking is gaining increased attention within the Chinese academic community. However, its expansion is impeded by several factors, including limited understanding of its value, inadequate institutional frameworks, and operational management support. This study aims to provide evidence supporting the involvement of time banking in care services for older adults.

In adherence to Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) 3, “Good Health and Wellbeing,” and SDG 10, “Reduced Inequalities,” special consideration is necessary for the older adults—a group often encountering restricted care access and ageism, both factors that can substantially impair their wellbeing (9, 10). The integration of home and community-based care models is advocated to improve outcomes for older adults (11). The drive toward establishment of age-friendly communities, which emphasize the welfare and quality of life for the older adults, resonates with a global aspiration (12). Time banking services not only enhance access to care for older adults but also counter potential disparities and discriminatory practices, fostering age-friendly environments. A key action area for such communities includes bolstering community support, foundational for healthy aging and aimed at elevating wellbeing and life satisfaction (13). Evidence shows that involvement in time banking can cultivate trust and promote goodwill within schools and urban areas (14), and it has been recommended as a method to harness social capital to counteract the challenges associated with an aging population (15). The 2021 Time Bank Development Research Report in China underscores the significance of incorporating time banking into higher education to enrich students' ethical awareness and practical abilities through volunteerism (16). Moreover, we posit that volunteering, traditionally viewed as an altruistic activity, may also be significantly shaped by diverse socio-economic factors (17). The aim of this study is to explore the determinants that influence university students' participation in time banking services and to amass evidence to bolster student engagement.

In China, time banking volunteer service for older adults among university students exhibit regional diversity. In Hunan Province, the Time Bank of Wangxianqiao Community has established a symbiotic relationship with neighboring colleges in Changsha County. This initiative transforms the community into a practical base for student volunteering and integrates these activities into the moral education system. Meanwhile, in Henan Province, the Youfang Community's Time Bank, developed in collaboration with the Zhishan Social Work Service Center of Henan University, showcases a partnership between social work centers and communities, with the project specifically designed to facilitate student social practice services. In Zhejiang Province, the Green Kang Time Bank demonstrates the cooperative efforts between higher education institutions, such as Zhejiang Gongshang University and Zhejiang Sci-Tech University, to serve the older adults through the engagement of college students. This collaboration not only enriches students' moral and practical experience but also grants official recognition of their volunteer services. Additionally, the School of Aging Service and Management at Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine (NJUCM), the first in China offering undergraduate programs in this field since 2020, represents a significant academic initiative. Endorsed by the Ministry of Civil Affairs, this school is at the forefront of the national active aging strategy, emphasizing the traditional ethos of respecting the older adults and promoting professional ethics in care for older adults through time-banking services. With a focus on this university community time banking, this study aims to explore the typical operation mode of China's time bank among youth groups.

2 Theoretical background

This research is grounded in the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), which posits that individual behavior is driven by behavioral intentions where these intentions are a function of an individual's attitude toward the behavior, the subjective norms surrounding the performance of the behavior, and the perceived behavioral control over the behavior (18). TPB has been widely applied to studies of volunteerism and is particularly relevant to understanding the motivations, a domain where volunteer services are exchanged within a community (19, 20). While TPB provided a valuable theoretical foundation for our research, we recognized certain limitations in its ability to fully account for the phenomena observed in time banking, particularly in the context of volunteer services for older adults. Literature highlights trust and social support as central to participation in time banking (21, 22). Trust, both knowledge-based and swift, is identified as crucial for the sharing of resources and successful collaboration within time banks (23, 24). Social cognitive theories further elucidate the psychological processes behind such community engagements (25). We adopted an exploratory approach to broaden our investigation beyond the confines of TPB. This approach allowed us to incorporate additional variables related to social support, and specific cultural factors that are crucial in the context of Chinese older adults' care. Drawing from the core principles of TPB, we integrated variables related to attitudes toward volunteer services for older adults, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, and intentions associated with these volunteer services, as indicated by existing studies (21, 26, 27). Additionally, incorporated investigation that delve into the students' socioeconomic characteristics and their attitudes toward traditional older adults' care culture in China, such as “filial piety” (28). By integrating these supplementary aspects with the core TPB framework, our study aimed to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing students' engagement in time banking. We meticulously selected a comprehensive range of variables for survey, applying factor analysis to derive actionable insights that inform the practical implementation of time banking practices in universities.

3 Data and methods

The questionnaire was distributed online, with data collection taking place in November, 2022. A convenience sampling method recruited students from the School of Aging Service and Management at NJUCM, China. A total of 374 students participates in the survey. Out of these, 254 responses contained no missing values, and did not present inconsistent information were included in the final analysis. We adhered strictly to the ethical standards associated with social surveys in our study. All participants provided informed consent, and we took meticulous care to explain the nature and purpose of the study, ensuring a comprehensive understanding before participation. Collected data is anonymized and handled with utmost care to prevent unauthorized access. Additionally, our research is part of projects funded by the school (funding numbers: 2023YLFWYGL006 and 2023YLFWYGL014). The projects have received formal approval and were signed off through the “Research Integrity Commitment Letter” from NJUCM, signed by the Dean and attests to our commitment to upholding research integrity, ethical standards, and compliance with all relevant regulations.

Factor analysis was performed to establish the validity and reliability of the influencing factors of participation in time banking volunteer services for older adults in this study. First, Bartlett's test of sphericity and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test were used to examine whether the correlation matrix was an identity matrix, thereby verifying the independence of all the variables included and assessing the suitability of the dataset for factor analysis. Based on the eigenvalues, the number of factors to be extracted was determined, followed by factor rotation to facilitate more straightforward interpretation and understanding of each factor. Furthermore, a logistic regression was conducted to analyze the factors affecting the willingness to participate. The factor scores (which can be obtained directly through STATA operations) were used as independent variables, while the dependent variable was coded as the willingness to participate (with a value of 0 indicating no willingness and a value of 1 indicating willingness). P < 0.05 was set as the standard for statistical significance, and STATA 15 software was utilized for the cleaning and preprocessing of the collected raw data.

4 Results

4.1 Samples characteristics

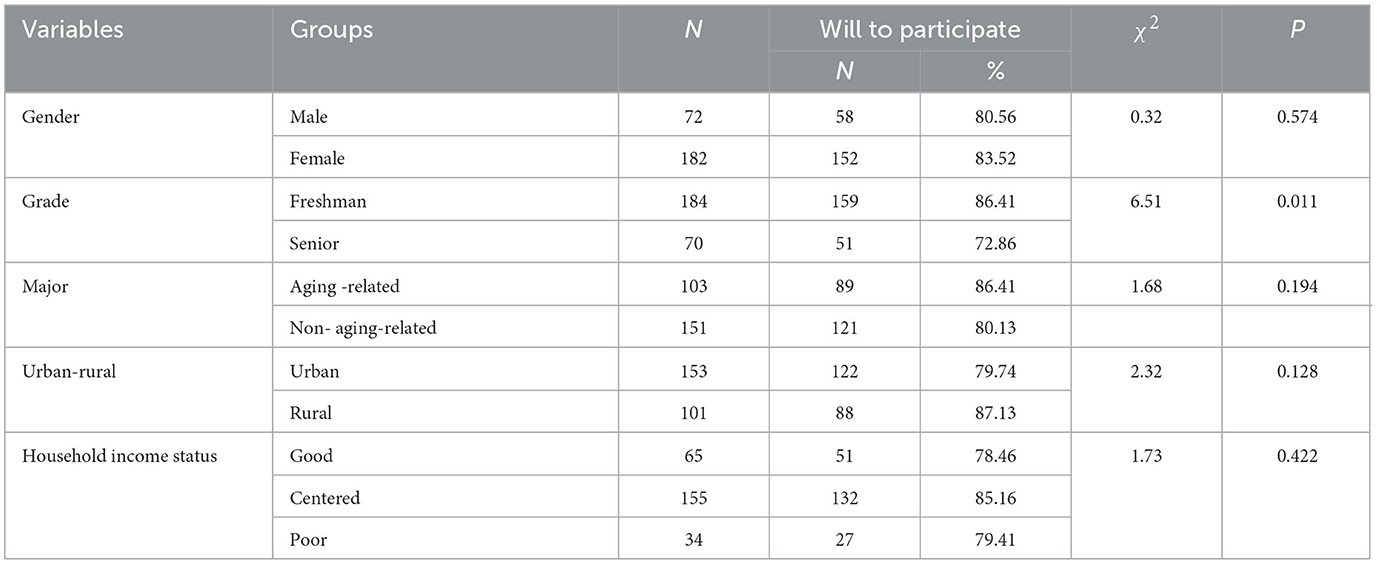

Table 1 displays the results of a survey on university students' willingness to engage in volunteer services for the older adults, segmented by demographic characteristics. Out of the 254 students surveyed, 210 (82.68%) indicated they were willing to volunteer. The data suggest that students who are female, in their freshman year, enrolled in aging-related majors, from rural backgrounds, or from households with moderate incomes show a greater propensity to volunteer in older adults' care services.

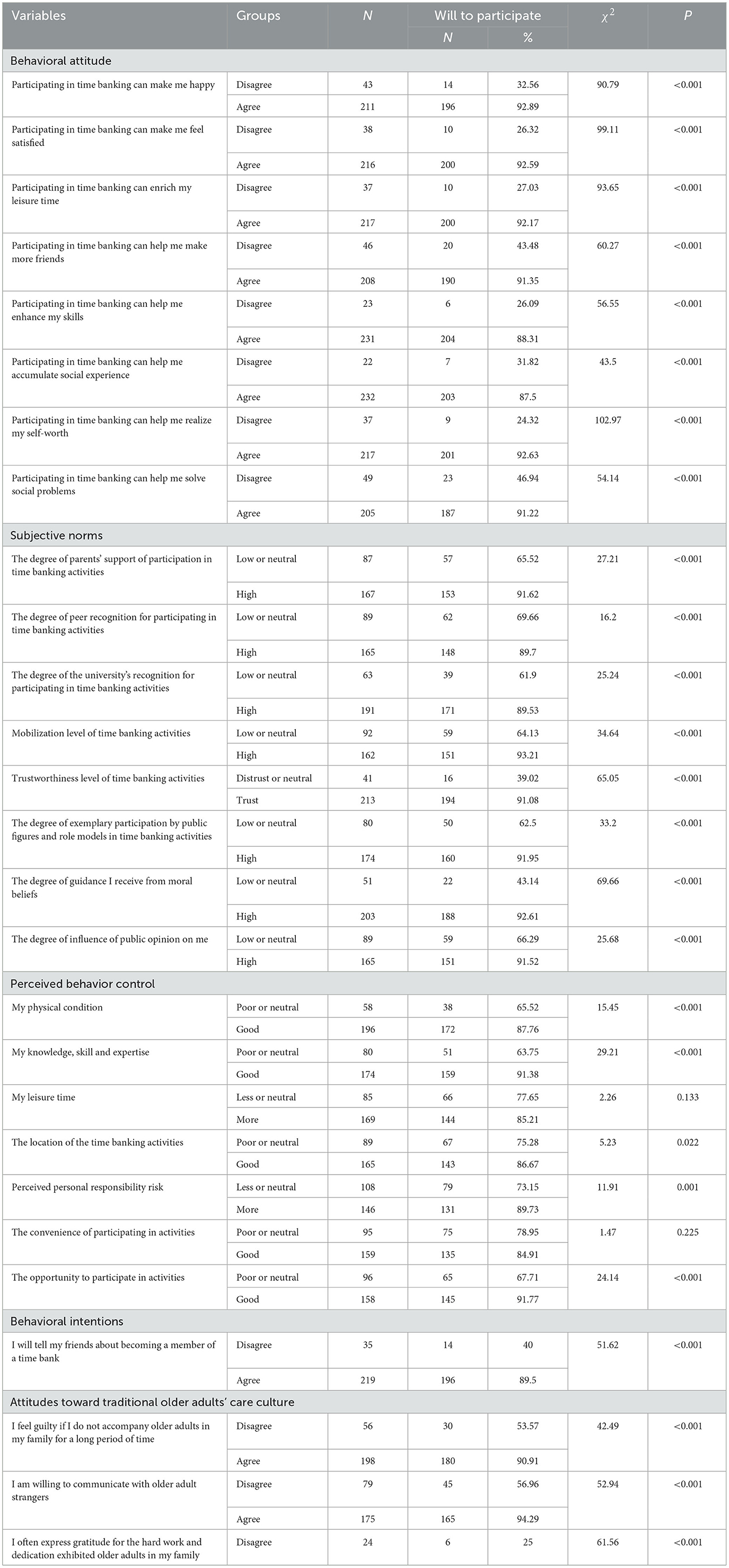

Table 2 shows the attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, and intentions, along with attitudes toward traditional older adults' care culture among the investigated university students and their willingness to engage in time banking volunteer services for the older adults. Behavioral attitude dimension indicates a strong agreement with the benefits of time banking, such as happiness, satisfaction, skill enhancement, and social experience accumulation, with high percentages of students willing to participate ranging from 87.5% to 92.89%. Subjective norms aspect shows high percentages of willingness to participate were also observed among students who felt support from parents, peers, and the university, or who saw high mobilization and trustworthiness in such activities. Perceived behavior control dimension shows that students who perceive themselves as having a good physical condition, adequate knowledge, skills, expertise, and leisure time, and who find the activities conveniently located, are more inclined to participate. A significant majority of students would tell their friends about becoming a member of a time bank. Lastly, attitudes toward traditional older adults' care culture indicates that those who feel a sense of guilt for not accompanying older adults or who are willing to communicate with older adult strangers have a higher percentage of willingness to participate in time banking.

4.2 Multicollinearity analysis

The multicollinearity of the factors influencing participation willingness was assessed using Bartlett's test of sphericity and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy. Bartlett's test of sphericity tests the assumption that the correlation matrix is an identity matrix. This test yielded a result of χ2 = 3736.279 (P < 0.001), leading to the rejection of the null hypothesis. The KMO statistic measures the degree of shared variance among variables by comparing the magnitudes of simple correlation coefficients to partial correlation coefficients. A KMO value of 0.871 was obtained, thus implying a substantial overlap of information among the variables and thereby indicating their suitability for factor analysis. Given these results, proceeding with factor analysis and multiple regression analysis was deemed appropriate.

4.3 Factor analysis

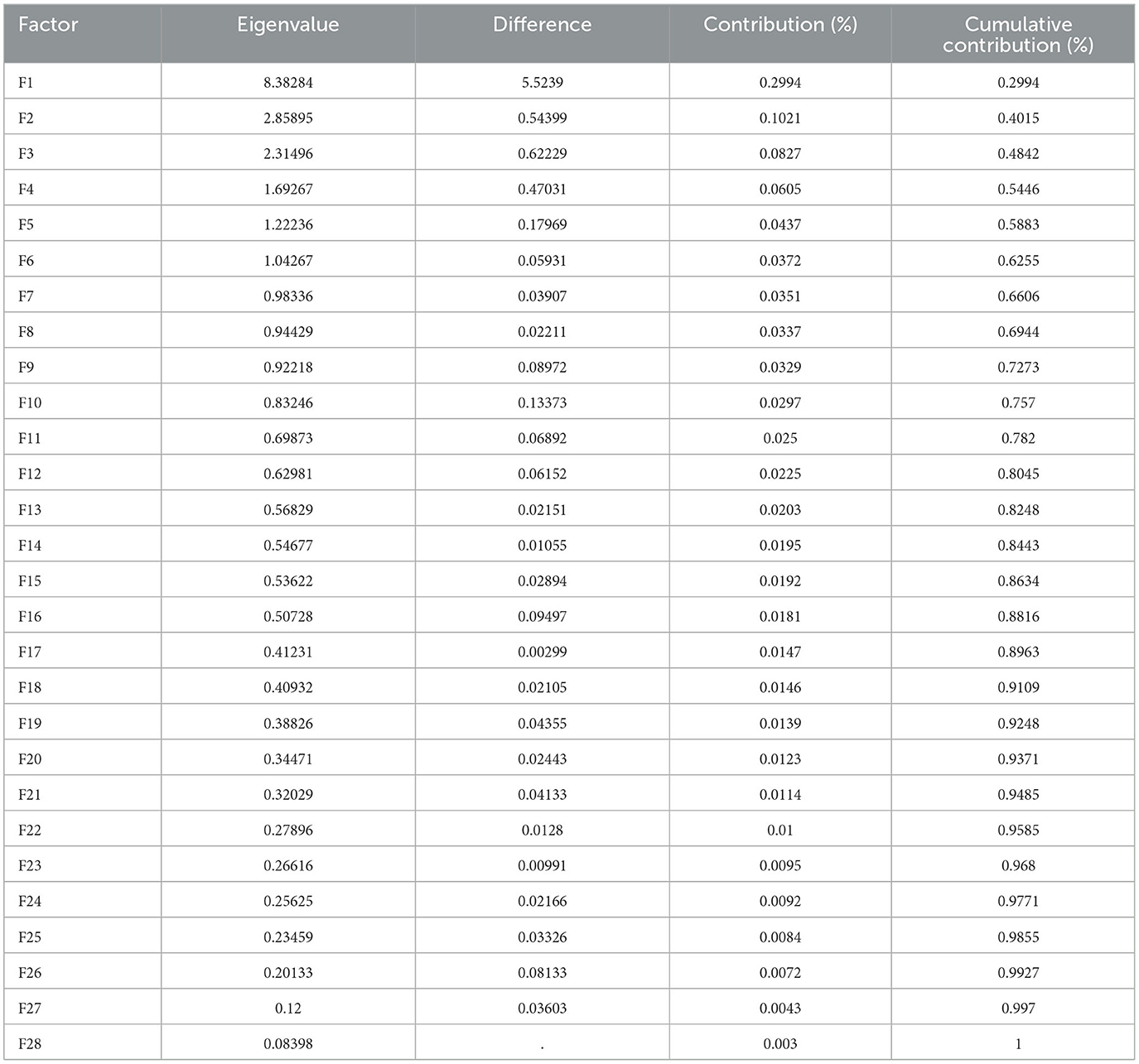

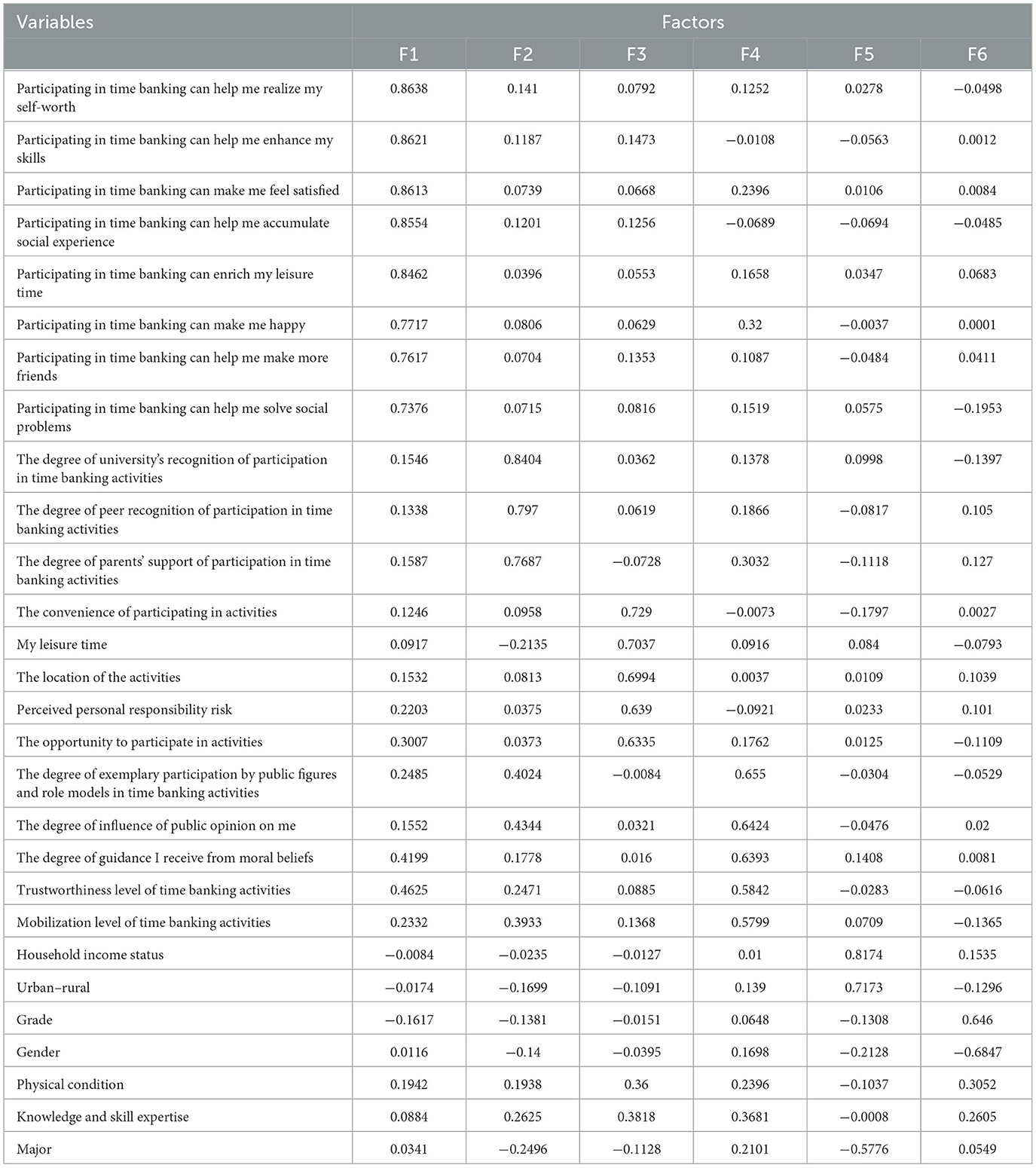

The results of the factor analysis are shown in Table 3. According to the criterion of an eigenvalue ≥1, 6 factors were extracted, which exhibited a cumulative contribution rate of 62.55%. After the maximum variance orthogonal rotation, the rotated component matrix was obtained, as shown in Table 4.

F1: Value Judgment Factor. This factor encompasses perceptions of volunteer services for older adults as avenues for personal growth and satisfaction. Specifically, it includes elements such as realizing one's self-worth, exercising one's abilities, deriving satisfaction, accumulating social experiences, enriching leisure time, fostering happiness, facilitating friendships, and contributing to social solutions.

F2: Social Support Factor. Recognition from key social relations, including schools, peers, and parents, is included as part of this factor, which emphasizes the role of external validation and encouragement.

F3: Objective Conditions Factor. This factor considers the tangible elements affecting participation, such as convenience, the availability of free time, the location of the activity, potential personal responsibility risks, and participation opportunities.

F4: Social Influence Factor. Aspects such as role modeling by public figures, prevailing social opinion, guidance from moral beliefs, the trustworthiness of volunteer activity organizers, and participant mobilization efforts are included under this classification.

F5: Socioeconomic Factor. Components pertaining to an individual's background, including his or her family's economic status and urban or rural residence, constitute this factor.

F6: Knowledge and Skills Factor. This final factor contains elements that are linked to one's professional profile, including the individual's grade, knowledge and skill expertise, major, and other professional competencies. It also integrates gender, physical condition, and other elements that influence an individual's self-assessment of their own knowledge and capabilities.

4.4 Multivariate logistic regression analysis

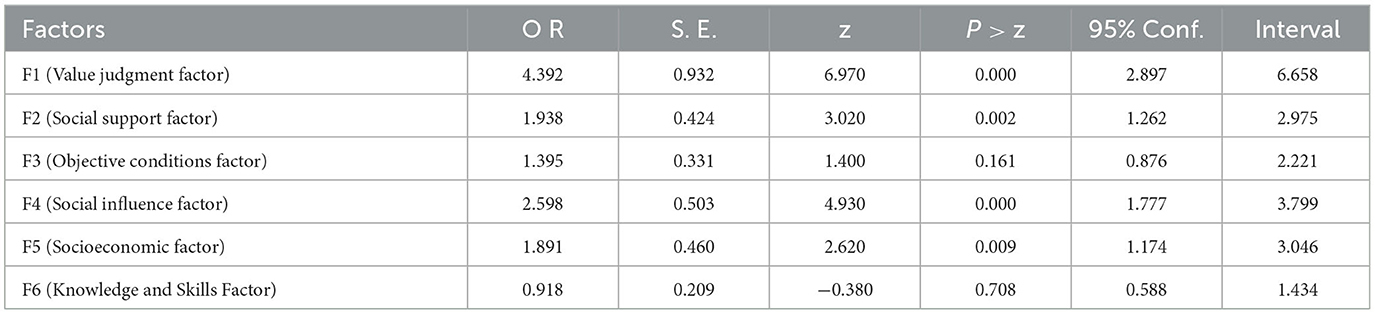

A multivariate logistic regression was conducted to explore the influence of the previously identified factors on undergraduates' willingness to participate in volunteer services for older adults. The results of a chi-square goodness-of-fit test of the model yielded a value of 110.64 (P < 0.001), thus emphasizing the model's robustness. Table 5 illustrates the detailed logistic regression outcomes: the Value Judgment Factor (F1) exhibited a strong positive association with students' willingness to participate, with the highest odds ratio (OR = 4.39, P < 0.001). The Social Support Factor (F2), Social Influence Factor (F4), and Socioeconomic Factor (F5) also significantly encouraged participation (OR > 1, P < 0.001). The Objective Conditions Factor (F3) exhibited a trend toward promoting participation, although this impact did not achieve statistical significance (P > 0.05). The Knowledge and Skills Factor (F6) seemed to potentially discourage participation, with an OR of 0.918 (P > 0.05).

Table 5. Logistic regression of the factors affecting willingness to participate in elder care volunteer services.

5 Discussion

To alleviate pressures from an aging population, time banking emerges as a promising strategy. It dovetails with the objectives of Sustainable Development Goals 3 and 10, particularly in prioritizing support for older adults as a vulnerable demographic. Despite its potential, Time banking is not widespread in China. One of the primary challenges in the widespread adoption of time banking in China is rooted in the cultural context. Traditional Chinese values emphasize family-based care for the older adults. This may limit the perceived need or acceptance of alternative systems like time banking, which are based on community sharing and reciprocity. Meanwhile, there is a relative lack of awareness and understanding of the time banking concept among the general population in China. Time banking, as a relatively new and Western-origin concept, is not widely recognized. Moreover, the policy environment in China has not yet fully adapted. It was only toward the end of 2021 that the term “time bank” was officially incorporated into a government document - the “Beijing Elderly Care Services Time Bank Implementation Plan (Trial).” In 2022, the development of the “time bank” mutual aid model for older adults' was explicitly proposed as a task in the Beijing government work report during the “Two Sessions.” However, this concept has not yet been implemented nationwide. The absence of comprehensive government endorsement may also constitute a barrier, impacting public trust and legitimacy. Besides, the development of time banking requires a robust technological infrastructure to facilitate the exchange of services and time credits. Especially in rural or less developed regions of China, the necessary technological infrastructure is not sufficiently advanced to support such systems. The School of Aging Service and Management at NJUCM, offering an undergraduate degree in aging service and management, reflects a Chinese governmental strategy to address the aging challenge (29). Our research based on this, probes the variables that affect university students' willingness to engage in time banking volunteer services for older adults. The aim is to uncover practical, data-driven strategies that can enhance the adoption and efficacy of time banking in universities.

Firstly, we found that 82.67% of the students in this survey expressed their willingness to participate in the provision of volunteer services for older adults, and students who are female, in their freshman year, enrolled in aging-related majors, from rural backgrounds, or from households with moderate incomes show a greater propensity to volunteer in care service for older adults. While students exhibit a substantial inclination toward participation in time banking volunteer services for older adults, a pronounced discrepancy exists between this intent and their actual participation. Such an inconsistency is in line with the findings of previous research (30). Several factors could contribute to it. Lack of awareness or access to opportunities, students may be willing to participate but are not aware of available opportunities or face barriers in accessing them. Moreover, there may be a difference between general willingness and the motivation required to take concrete action. Such as perceived impact, personal gains, and social recognition play a role in transitioning from intent to action. This gap between intent and participation is an important area for future research. Studies specifically designed to investigate these barriers and facilitators to participation would provide valuable insights into converting willingness into active engagement.

Among them, female students exhibit higher participatory willingness, which can potentially be attributed to the perceived traits of patience and empathy (31). The motivations for volunteering across different gender groups, additional evidence is needed to substantiate this analysis. Freshmen, who are new enrollees, might experience less study pressure and thus have more time and enthusiasm for volunteerism. Students in aging-related majors, due to their study focus, likely possess deeper insights into the needs of and challenges faced by older adult individuals, thereby exhibiting an increased propensity to serve this demographic. The tight-knit familial and community bonds observed in rural areas might foster a heightened sense of community service among these students (32). Students from moderate economic backgrounds, compared to their more affluent or economically disadvantaged peers, may have more time and resources to dedicate to volunteer activities (33). This could potentially lead to a stronger and more sustained willingness to participate. The particularities of volunteer services for older adults in the context of Chinese traditional culture, contrasted with the “volunteerism elitism” perspective prevalent in the West counties (34), offer a fresh perspective in understanding volunteer behavior in care for older adults within the unique Chinese context. It is noteworthy that groups showing less willingness to engage in voluntary services could be at a heightened risk of social exclusion. This is because volunteering is often perceived not only as a means to augment individual resources but also as a vital pathway for reducing social exclusion. It facilitates “creating avenues for reintegration into society and provides opportunities for individuals to become more involved in their communities” (35).

Secondly, the research indicates that several factors influence university students' willingness to participate in time banking care services. A predominant factor is their value judgments. Students place a high value on the intrinsic benefits they derive from participation, such as self-realization, skill development, satisfaction, and enriching social experiences. This observation is consistent with a longitudinal study of first-time non-violent juvenile offenders in Washington, DC. Participants referred to the Youth Court showed the effectiveness of voluntary service programs (36). A significant correlation was found with the development of life skills, particularly in areas like goal setting, problem-solving, decision-making, and academic learning (37). In another study, an intervention framework for co-production and time banking, designed to assist practitioners in implementing time banking projects, revealed an interesting trend. Initially, student participation was involuntary, but it evolved into a semi-voluntary engagement. This transition was marked by a significant increase in emotional and cognitive engagement, leading to the development of social skills, improved self-esteem, and positive identity formation (38). Furthermore, trust theory suggests that when students believe their participation will fulfill the intrinsic values mentioned earlier, their commitment tends to become more steadfast (39). A parallel can be drawn with a survey on older adults' motivations for sustained volunteerism, where the primary driving force was societal contribution, deeply rooted in a spirit of altruism (40). Given these insights, it becomes crucial for universities and government bodies to tailor time banking and volunteer services for older adults to align with these motivations and needs. Such alignment not only meets the specific requirements of the older adults but also enhances the engagement and fulfillment of the student volunteers.

Our findings also reveal that the social support factor, including recognition from key social relations such as schools, peers, and parents, plays a significant role. This factor is crucial according to the theory of social capital, which posits that social relations and networks profoundly influence individual behaviors. They provide individuals with support, resources, and pertinent information, thereby increasing their likelihood of engaging in volunteer services for older adults (41). Conversely, time banking contributes significantly to the development of social capital (15). Participants in time banking, who exhibit increased self-efficacy, also demonstrate a heightened sense of community (42, 43). Additionally, we discovered that the influence of social influence, public figures, and public opinion is significant. Public figures' endorsements or criticisms can not only shape public opinion but also enhance or diminish the perceived credibility of social causes and initiatives (44). Celebrities and influential personalities can inspire and motivate students by setting an example through their own involvement or endorsement. Public opinion, shaped by media and social discourse, raises awareness about the importance of such volunteering, potentially making it a socially valued and expected activity. This creates a conductive environment where university students feel encouraged and motivated to participate, aligning their actions with societal expectations and the examples set by admired figures (17, 45). Moreover, social cognitive theory suggests that individual behavior is influenced by social cognitive processes (46, 47), this influence is mediated by established social norms, collective identity, and channels of information dissemination, thereby fostering individual involvement in volunteer services for older adults (48). Observing peers, relatives, or community members engage in volunteer services for older adults, an individual might perceive such behavior as socially approved and valuable, thus influencing their own behavior. This type of influence, achieved through social norms, group identity, and information transmission mechanisms, encourages participation (49). In addition to these, factors related to knowledge and skills may also influence individuals' willingness to participate in volunteer services for older adults (50). Lastly and in line with previous studies (51, 52), socioeconomic factors may influence individuals' willingness to participate in volunteer services. This highlights the need for policy-makers to consider students' actual conditions and avoid excessive motivation.

While the findings show that volunteer projects organized by educational institutions are influenced by a variety of factors, there are concerns about their long-term viability. The sustainability and ongoing commitment of students to community service pose significant challenges in China, particularly in Hong Kong (15). For example, secondary school students are typically engaged in the Other Learning Experience (OLE) project, which relates to community service, often are unable to develop a strong sense of personal and social responsibility within their communities (53). This implies that despite previous experiences, their future participation in volunteer services may not be sustained. The motivational factors influencing university students may significantly differ, given their increased autonomy and more defined career and social responsibility perspectives. As highlighted in the China Time Bank Development Research Report, time banking is increasingly gaining attention in the Chinese academic sphere. However, its prolonged development faces challenges, including a limited general understanding of its benefits, and the need for more robust institutional frameworks and operational management support. To foster sustainable and continuous engagement in time banking among university students, a synergistic approach involving government, society, and educational institutions is crucial. In light of our study's insights, we propose a comprehensive strategy for promotion that includes: Firstly, further popularizing the concept of time banking in China is crucial. The Government should provide more resources in the community and subsidies for universities, including raising awareness about the value of time banking, which aligns with the SDGs for improving older adults' access to care and addressing issues of limited opportunities and discrimination. Additionally, coordinating the activities for the exchange of time and service is vital. Given that time banks often struggle to cover administrative costs, government and university financial support can aid both promotion and operations of time banks, helping university students perceive such behavior as socially approved and valuable. Moreover, social commercial organizations, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and family units can also play a significant role in the promotional process of time banking. Furthermore, Party members in China, who are pivotal in public welfare activities (2), therefore could encourage the student members to participate as the exemplary deeds.

This study focuses on identifying factors influencing university students' participation in time banking volunteer services for older adults and providing evidence to promote involvement, which is in line with university education of major in aging service and management in China, emphasizes traditional cultural values, mirroring the “virtue-first” approach and the respect for the older adults deeply ingrained in Chinese society. These principles are akin to the concepts of “character education” or “moral education” prevalent in Western countries, aimed at nurturing well-rounded value systems and moral judgment in students. As the related undergraduate programs become more widespread in Chinese universities, our research provides essential insights for practical volunteer service education in these areas. Moreover, the application of our findings in promoting time banking services among other youth groups in China could serve as a model of reference with time banking volunteer services for older adults among university students exhibit regional diversity.

We acknowledge key limitations in our research and suggest directions for future studies. Our use of an exploratory survey design is a crucial factor to consider while interpreting our results. One specific limitation is the focus on NJUCM, known for its emphasis on traditional Chinese cultural education, which might influence the higher willingness among surveyed students to participate in volunteer services for older adults. Furthermore, in the data processing phase, there may also be biases such as merging groups with very few samples, and the exclusion of certain variables, despite we based on a theoretical framework. Self-report bias is another limitation that cannot be entirely eliminated in our study. Future research employing diverse methodologies, such as observational studies or third-party reported data, would be valuable to gain a more comprehensive understanding of students' true willingness to volunteer. Additionally, the potential for non-response bias we suggest future studies might explore this further, possibly through more targeted outreach to non-respondents or employing alternative data collection methods.

6 Conclusion

We found a strong willingness among university students majoring in aging service and management students to participate in time banking. A multifaceted support involving governmental, social, and university is recommended to promote the involvement.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

YW: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Validation, Visualization. SL: Data curation, Investigation, Writing—original draft. YS: Investigation, Writing—original draft. ZZ: Investigation, Writing—original draft. YL: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Writing—review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by the Jiangsu Province Higher Education Philosophy and Social Science (2022SJYB0327), Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine (NZYJG2022136), Philosophy and Social Sciences in Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (2022SJSZ0104), School of Aging Service and Management (Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine) (2023YLFWYGL006 and 2023YLFWYGL014), and Jiangsu Province Higher Education Teaching Reform Research Project (2021JSJG053).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Ng TKC, Fong BYF, Leung WKS. Enhancing Social Capital for Elderly Services with Time Banking. In:Law VTS, Fong BYF, , editors. Ageing with Dignity in Hong Kong and Asia: Holistic and Humanistic Care. Quality of Life in Asia. Singapore: Springer Nature (2022). p. 377–393.

2. Wu Y, Ding Y, Hu C, Wang L. The Influencing Factors of Participation in Online Timebank Nursing for Community Elderly in Beijing, China. Frontiers in Public Health. (2021) 9:650018. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.650018

3. Seyfang G. Growing cohesive communities one favour at a time: social exclusion, active citizenship and time banks. Int J Urban Reg Res. (2003) 27:699–706. doi: 10.1111/1468-2427.00475

4. Laamanen M, Wahlen S, Campana M. Mobilising collaborative consumption lifestyles: a comparative frame analysis of time banking. Int J Consum Stud. (2015) 39:459–67. doi: 10.1111/ijcs.12190

5. Moyer L. An impact assessment model for web-based time banks – a thought-experiment in the operationalization of social capital. Consilience. (2015) 106–25. Available online at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/26188744

6. (Tina) Yuan CW, Hanrahan BV, Carroll JM. Is there social capital in service exchange tools? Investigating timebanking use and social capital development. Comput Hum Behav. (2018) 81:274–281. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2017.12.029

7. Ozanne LK. Learning to Exchange Time: Benefits Obstacles to Time Banking. (2010). Available online at: http://hdl.handle.net/10092/3793 (accessed November 15, 2023).

8. Lasker J, Collom E, Bealer T, Niclaus E, Young Keefe J, Kratzer Z, et al. Time banking and health: the role of a community currency organization in enhancing well-being. Health Promot Pract. (2011) 12:102–15. doi: 10.1177/1524839909353022

9. Rippon I, Kneale D, de Oliveira C, Demakakos P, Steptoe A. Perceived age discrimination in older adults. Age Ageing. (2014) 43:379–86. doi: 10.1093/ageing/aft146

10. Marquet M, Chasteen AL, Plaks JE, Balasubramaniam L. Understanding the mechanisms underlying the effects of negative age stereotypes and perceived age discrimination on older adults' well-being. Aging Ment Health. (2019) 23:1666–73. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2018.1514487

11. Low L-F, Yap M, Brodaty H. A systematic review of different models of home and community care services for older persons. BMC Health Serv Res. (2011) 11:93. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-93

12. Lui C-W, Everingham J-A, Warburton J, Cuthill M, Bartlett H. What makes a community age-friendly: A review of international literature. Australas J Ageing. (2009) 28:116–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6612.2009.00355.x

13. Alley D, Liebig P, Pynoos J, Banerjee T, Choi IH. Creating elder-friendly communities. J Gerontol Soc Work. (2007) 49:1–18. doi: 10.1300/J083v49n01_01

14. Singh S,. The Evolution of Giving: An Exploration of Time Banking as a Community Development Instrument. Senior Theses. (2017) 188. Available online at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/senior_theses/188

15. Ng TK, Yim NT. Time banking for elderly in Hong Kong: Current practice and challenges. Asia Pacific J Health Manage. (2020) 15:23–9. doi: 10.24083/apjhm.v15i2.375

16. Peking University C. China Time Bank Development Research Report. (2021). Available online at: https://pic.crcf.org.cn/attachment/20210926/d2cdae56d5b440f78fe321570f33d135.pdf (accessed August 30, 2023).

17. Haski-Leventhal D. Altruism and volunteerism: the perceptions of altruism in four disciplines and their impact on the study of volunteerism. J Theory Soc Behav. (2009) 39:271–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5914.2009.00405.x

18. Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. (1991) 50:179–211. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

19. MacGillivray GS, Lynd-Stevenson RM. The revised theory of planned behavior and volunteer behavior in Australia. Commun Dev. (2013) 44:23–37. doi: 10.1080/15575330.2012.675578

20. Okun MA, Sloane ES. Application of planned behavior theory to predicting volunteer enrollment by college students in a campus-based program. Soc Behav Pers Int J. (2002) 30:243–9. doi: 10.2224/sbp.2002.30.3.243

21. Kakar AK. Investigating factors that promote time banking for sustainable community based socio-economic growth and development. Comput Human Behav. (2020) 107:105623. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2018.07.034

22. Lee C, Burgess G, Kuhn I, Cowan A, Lafortune L. Community exchange and time currencies: a systematic and in-depth thematic review of impact on public health outcomes. Pub Health. (2020) 180:117–28. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2019.11.011

23. Blomqvist K, Cook K. Swift Trust-State-of-the-Art and Future Research Directions. Paris: OECD (2018), p. 29–49

24. Robert L, Dennis A, Hung Y-T. Individual swift trust and knowledge-based trust in face-to-face and virtual team members. J Manage Inf Syst. (2009) 26:241–79. doi: 10.2753/MIS0742-1222260210

25. Leung WKS, Chang MK, Cheung ML, Shi S. Swift trust development and prosocial behavior in time banking: a trust transfer and social support theory perspective. Comput Human Behav. (2022) 129:107137. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2021.107137

26. Venkatesh V, Thong JYL, Xu X. Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Quarterly. (2012) 36:157–78. doi: 10.2307/41410412

27. Rintamäki T, Kanto A, Kuusela H, Spence MT. Decomposing the value of department store shopping into utilitarian, hedonic and social dimensions: evidence from Finland. Int J Retail Distrib Manage. (2006) 34:6–24. doi: 10.1108/09590550610642792

28. Liu S. Research on the realistic path of rural mutual aid for the aged under the background of rural revitalization. Front Bus Econ Manage. (2022) 5:168–70. doi: 10.54097/fbem.v5i2.1757

29. School of Elderly Care Service Management N. Introduction of School of Elderly Care Service and Management. (2021). Available online at: https://ylxy.njucm.edu.cn/5497/list.htm (accessed August 30, 2023).

30. Xin Y, An J, Xu J. Continuous voluntary community care services for older people in China: evidence from Wuhu. Front Pub Health. (2023) 10:1063156. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1063156

31. Christov-Moore L, Simpson EA, Coudé G, Grigaityte K, Iacoboni M, Ferrari PF. Empathy: gender effects in brain and behavior. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2014) 46:604–27. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.09.001

32. Sørensen J. Rural–urban differences in bonding and bridging social capital. Reg Stud. (2014) 50:1–20. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2014.918945

34. Bonnesen L. Social inequalities in youth volunteerism: a life-track perspective on Danish youths. Voluntas Int J Volunt Nonprofit Org. (2018) 29:160–73. doi: 10.1007/s11266-017-9934-1

35. Southby K, South J. Volunteering, Inequalities Barriers to Volunteering: A Rapid Evidence Review. Volunteering Matters. (2016). Available online at: https://volunteeringmatters.org.uk (accessed August 31, 2023).

36. Marks MB. Time banking service exchange systems: a review of the research and policy and practice implications in support of youth in transition. Child Youth Serv Rev. (2012) 34:1230–6. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.02.017

38. A Theoretical Empirical Investigation of Co-Production Interventions for Involuntary Youth in the Child Welfare Juvenile Justice Systems - ProQuest. (2023). Available online at: https://www.proquest.com/openview/acd7dbeb91dc90fcb3b84b8c8d05813d/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750 (accessed November 15, 2023).

39. Osterman KF. Students' need for belonging in the school community. Rev Educ Res. (2000) 70:323–67. doi: 10.3102/00346543070003323

40. Burns D, Reid J, Toncar M, Fawcett J, Anderson C. Motivations to volunteer: the role of altruism. Int Rev Pub Nonprofit Marketing. (2006) 3:79–91. doi: 10.1007/BF02893621

41. Latkin CA, Knowlton AR. Social network assessments and interventions for health behavior change: a critical review. Behav Med. (2015) 41:90–7. doi: 10.1080/08964289.2015.1034645

42. Yuan CW, Hanrahan BV, Carroll JM. Assessing timebanking use and coordination: implications for service exchange tools. Inf Technol People. (2018) 32:344–63. doi: 10.1108/ITP-09-2017-0311

43. Aldrich DP, Meyer MA. Social capital and community resilience. Am Behav Sci. (2015) 59:254–69. doi: 10.1177/0002764214550299

44. Seiter RHG, John S. Persuasion: Social Influence and Compliance Gaining, 7th Edn. New York, NY: Routledge (2022), p. 500.

45. Zsila Á, Orosz G, McCutcheon LE, Demetrovics Z. Individual differences in the association between celebrity worship and subjective well-being: the moderating role of gender and age. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:651067. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.651067

46. Schunk DH, DiBenedetto MK. Motivation and social cognitive theory. Contemp Educ Psychol. (2020) 60:101832. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2019.101832

47. Lent RW, Brown SD, Hackett G. Toward a unifying social cognitive theory of career and academic interest, choice, and performance. J Vocat Behav. (1994) 45:79–122. doi: 10.1006/jvbe.1994.1027

48. Farooq O, Rupp DE, Farooq M. The multiple pathways through which internal and external corporate social responsibility influence organizational identification and multifoci outcomes: the moderating role of cultural and social orientations. AMJ. (2017) 60:954–85. doi: 10.5465/amj.2014.0849

49. Liu H, Zhu Y, Li Y. Multiple network effects: “individual-organization social interaction” model on China's sustainable voluntary service supply mechanism. Sustainability. (2023) 15:10562. doi: 10.3390/su151310562

50. Farr R. Exploring the Relationship Between Civic Engagement, Early Life, and Wellbeing: A Mixed Methods Study With a Diverse Sample of University Students. London: University of East (2023).

51. Mak H, Fancourt D. Predictors of engaging in voluntary work during the COVID-19 pandemic: analyses of data from 31,890 adults in the UK. Perspect Public Health. (2022) 142:287–96. doi: 10.1177/1757913921994146

52. Seifert A, König R. Help from and help to neighbors among older adults in Europe. Front Sociol. (2019) 4: 46. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2019.00046

Keywords: volunteer services for older adults, factor analysis, time banking, theory of planned behavior, sustainable development goals

Citation: Wu Y, Liu S, Song Y, Zhang Z and Liu Y (2024) The influencing factors of participation in time banking volunteer service for older adults among university students in Nanjing, China. Front. Public Health 11:1289512. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1289512

Received: 06 September 2023; Accepted: 19 December 2023;

Published: 11 January 2024.

Edited by:

Hiroto Narimatsu, Kanagawa Cancer Center, JapanReviewed by:

Sean Mark Patrick, University of Pretoria, South AfricaRodica Ianole-Calin, University of Bucharest, Romania

Copyright © 2024 Wu, Liu, Song, Zhang and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yunlong Liu, NzQwOTc1ODcwQHFxLmNvbQ==

Yue Wu

Yue Wu Siyu Liu

Siyu Liu