94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Public Health, 20 November 2023

Sec. Substance Use Disorders and Behavioral Addictions

Volume 11 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1284192

Elizabeth O. Obekpa1*

Elizabeth O. Obekpa1* Sheryl A. McCurdy1

Sheryl A. McCurdy1 Vanessa Schick2

Vanessa Schick2 Christine M. Markham1

Christine M. Markham1 Kathryn R. Gallardo3

Kathryn R. Gallardo3 Johnny Michael Wilkerson1

Johnny Michael Wilkerson1Background: Recovery from opioid use disorder (OUD) includes improvements in health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and is supported by recovery capital (RC). Little is known about RC and HRQOL among recovery residents taking medication for OUD. We described HRQOL and RC and identified predictors of HRQOL.

Methods: Project HOMES is an ongoing longitudinal study implemented in 14 recovery homes in Texas. This is a cross-sectional analysis of data from 358 participants’ on HRQOL (five EQ-5D-5L dimensions—mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression) and RC (Assessment of Recovery Capital scores) collected from April 2021 to June 2023. Statistical analyses were conducted using T-, Chi-squared, and Fisher’s exact tests.

Results: Most participants were 35 years/older (50.7%), male (58.9%), non-Hispanic White (68.4%), heterosexual (82.8%), and reported HRQOL problems, mainly anxiety/depression (78.4%) and pain/discomfort (55.7%). Participants who were 35 years/older [mean (SD) = 42.6 (7.3)] were more likely to report mobility and pain/discomfort problems than younger participants. Female participants were more likely to report pain/discomfort problems than male participants. Sexual minorities were more likely to report anxiety/depression problems than heterosexual participants. Married participants and those in committed relationships were more likely to report problems conducting self-care than single/never-married participants. Comorbid conditions were associated with mobility, pain/discomfort, and usual activities problems. Most participants reported high social (65.4%), personal (69.0%), and total (65.6%) RC. Low personal RC was associated with mobility (aOR = 0.43, CI = 0.24–0.76), self-care (aOR = 0.13, CI = 0.04–0.41), usual activities (aOR = 0.25, CI = 0.11–0.57), pain/discomfort (aOR = 0.37, CI = 0.20–0.68), and anxiety/depression (aOR = 0.33, CI = 0.15–0.73) problems. Low total RC was associated with problems conducting self-care (aOR = 0.20, CI = 0.07–0.60), usual activities (aOR = 0.43, CI = 0.22–0.83), pain/discomfort problems (aOR = 0.55, CI = 0.34–0.90), and anxiety/depression (aOR = 0.20, CI = 0.10–0.41) problems. Social RC was not associated with HRQOL.

Conclusion: Personal and total RC and comorbid conditions predict HRQOL. Although the opioid crisis and the increasing prevalence of comorbidities have been described as epidemics, they are currently being addressed as separate public health issues. Our findings underscore the importance of ensuring residents are provided with interprofessional care to reduce the burden of comorbidities, which can negatively impact their OUD recovery. Their RC should be routinely assessed and enhanced to support their recovery and improve HRQOL.

Substance use disorders (SUDs), including opioid use disorder (OUD), negatively impact the quality of life (QOL), physical, mental, and emotional states, and social interactions of individuals who use substances (1). The opioid epidemic in the United States (US) is worsening, with over 9 million individuals misusing opioids and 5.6 million individuals having an OUD in 2021 (2). Over 91,000 drug overdose deaths were reported in 2020, an increase of 31% from 2019, and nearly 75% of all overdose deaths were attributed to opioids (3). Opioid and stimulant use disorders and drug overdoses in the US were responsible for 15.03 million disability-adjusted life years between March 2020 and February 2022 (4).

There is an increasing interest in QOL for decision-making, especially for economic evaluations, and as an essential outcome in clinical care and SUD recovery (1, 5, 6), particularly as perceived health-related quality of life (HRQOL) is a stronger predictor of mortality and morbidity than objective assessments of health (7, 8). Individuals with current or past OUD have significant reductions in HRQOL (9). Individuals with SUDs seeking treatment have persistently lower HRQOL than those without SUDs (1). Positive changes in HRQOL among individuals with OUD are associated with recovery outcomes, including improvements in stable housing and decreases in illicit drug use (10).

Risk factors for OUD and opioid overdose deaths involving prescription and non-medical opioid use include mental and physical comorbidities and a history of SUD (11, 12). The prevalence of comorbid mental disorders is higher in adults with OUD compared to the general population (12, 13), with depression and anxiety being the most prevalent and associated with poorer HRQOL (14–17). Similarly, asthma is the most prevalent chronic disease related to opioid-related hospitalization, followed by obesity, liver disease, arthritis, cancer, and stroke (18). Patients with these chronic diseases often experience chronic pain (18) and significant reductions in their HRQOL (19–23). About 20.4% of U.S adults were living with chronic pain in 2016 (24), with researchers finding that individuals who reported chronic pain have problems conducting daily activities, mobility restrictions, worse health status, disability, and increased mortality risk (25–28).

Individuals who engage in the non-medical use of opioids frequently engage in polysubstance use, complicating the diagnosis and treatment of SUDs and accounting for most opioid-related overdose deaths (29). Most individuals engaging in polysubstance use have lower HRQOL (30) and develop comorbid SUDs (12). For instance, among individuals with an opioid (heroin) use disorder, about a quarter have an alcohol use disorder, more than 20% have a cocaine use disorder, and 12.3% have a marijuana use disorder (12). Other predictors of HRQOL among individuals with SUDs include sociodemographic characteristics, e.g., younger age, male gender, Caucasian race, marital status, employment, and higher educational qualifications, which positively correlate with higher HRQOL dimensions (1, 31–35).

Recovery from OUD is a multidimensional concept that includes improvements in mental and physical health and overall functioning following abstinence (36). Many individuals with OUD have poorer HRQOL than non-users (9, 37). Most literature on HRQOL emphasizes the impact of chronic diseases on an individual’s health and well-being rather than identifying predictors of HRQoL and resources that could support recovery from OUD and improve HRQoL (37, 38). Such research could help health planners, policymakers, and recovery resident operators plan and implement more effective recovery programs for OUD. This is critical as recovery from OUD is supported by medication for OUD (MOUD) and an individual’s ability to use resources for abstinence initiation and maintenance (39). However, despite the effectiveness of MOUD in treating OUD, decreasing illicit substance use, and improving retention in care, uptake remains low (40).

Recovery capital (RC) describes the entirety of resources individuals can use to support their recovery initiation and maintenance (39). RC comprises five resources: social, personal, physical, community, and cultural (41). However, social and personal RC may be stronger predictors of long-term recovery, with high social RC regulating the impact of low personal RC (42). Social RC is the benefits obtained from social networks and relationships that support recovery, including social support and social expectancies (41, 42). Personal RC is defined as individual characteristics, including self-efficacy, education/vocational skills, and mental and physical health (41, 42). Social and personal RC can be continually amassed or depleted over time as an individual’s opioid use or recovery impacts their personal and social functioning (43). Understanding RC in research and practice is critical, particularly as the more RC an individual possesses, the higher their perceived QOL may be.

The World Health Organization QOL (WHOQOL) dimensions are associated with social and personal RC among emerging adults in substance use treatment (43) and total RC in treatment and recovery samples (6). RC improves QOL by 22% among individuals with an SUD (44). High social RC is associated with greater QOL and enhanced health outcomes (43, 45). Personal RC, such as abstinence self-efficacy, is associated with greater QOL (46). Although research on RC and HRQOL among individuals with SUDs is growing, more attention needs to be paid to RC and HRQOL among individuals with OUD living in recovery homes. This study aimed to describe RC and HRQOL across five health dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression) and identify predictors of the health dimensions among a sample of recovery residents taking MOUD. Specifically, we aimed to answer two research questions: (1) do participants differ in their RC and HRQOL levels when entering the recovery homes for OUD recovery support? (2) what are the predictors of HRQOL?

Project HOMES (Housing for Opioid Medication-Assisted Recovery Expanded Services) is an ongoing longitudinal study of 14 level II (monitored homes, staffed with a paid house manager) and III (supervised homes, staffed with a paid house manager, Director/Administrator, and certified peer support) recovery homes (47) for persons in recovery for OUD and residing in five Texas cities. Eligibility includes a primary diagnosis of OUD, taking MOUD or willing to take before move-in, 18+ years, English or Spanish speaking, able and willing to consent, and agree to sign the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-compliant releases. Trained data collectors obtained written informed consent. Data analyzed were collected from April 2021 through June 2023. Ethical approval was granted by the institutional review board of the authors’ home institution. Participants received a $25 gift card for their time.

Participants were asked about their age, race/ethnicity, sex at birth, sexual orientation, education, employment, and marital status (48). To ensure adequate statistical power in the regression models, dichotomous variables for race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White and racial/ethnic minorities) and employment (employed and unemployed) were created.

Health-related Quality of Life (HRQoL) was measured using the EQ-5D-5L instrument, which consists of a descriptive system that assesses participants’ self-rated health state in five dimensions - mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression (49). Participants indicate their functioning level in a given dimension. Each dimension has five response levels of severity - no problem (1), slight problem (2), moderate problem (3), severe problem (4), and extreme problem (5) (see Table 1). The EQ-5D-5L responses were dichotomized as no problems and any problems (slight, moderate, severe, and extreme) to change the health states into frequencies of reported problems (49). Responses were also combined to generate health state profiles ranging from full health (11111) to worst health (55555). Each value for a health state was linked to a value set, i.e., index values (weights) for the US. The HRQOL index values range from −0.281 to 1, with negative values representing health states worse than death, 0 representing a health state equivalent to death, and 1 representing full health (49). Sample α = 1.000.

Participants were asked about their illicit drug use or misuse in the past 90 days (48). The most frequently reported drugs used were street opioids (55.0%), followed by amphetamines (45.3%), methamphetamines (42.2%), benzodiazepines (38.8%), marijuana (37.5%), prescription opioids (26.0%), and cocaine (24.3%) (Supplementary Table S1). Participants were categorized as engaging in polydrug use based on the number of reported drugs used in the past 90 days.

Hazardous drinking was assessed using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) (50). The AUDIT measures the frequency of drinking, typical quantity, frequency of heavy drinking, impaired control over drinking, increased salience over drinking, morning drinking, guilt after drinking, blackouts, alcohol-related injuries, and others’ concerns about drinking in the past year. Participants with scores of 8 or above were categorized as having a high risk for hazardous drinking (sample α = 0.879).

Participants were asked about 36 comorbid diseases, including depression, anxiety, cancer, arthritis, stroke, and diabetes. Participants were categorized as having comorbid diagnoses or not based on the number of reported comorbid diagnoses.

The Assessment of Recovery Capital (ARC) is a 50-item, dichotomous (0 = disagree, 1 = agree) scale used to assess participants’ RC across two domains (6). Each domain has five dimensions. The social RC domain includes substance use and sobriety, citizenship and community involvement, social support, meaningful activities, and housing and safety. The personal RC domain has global psychological and physical health, risk-taking, coping and life functioning, and recovery experience. Participants were asked to indicate their agreement or disagreement with each statement. The sum scores were calculated to create scores for social and personal ARC ranging from 0 to 25 and a total ARC score ranging from 0 to 50. Using cutoff points described in Obekpa et al. (51), ARC scores were dichotomized as low or high social, personal, and total RC (sample α: total = 0.852, social = 0.713, and personal = 0.768).

Study variables were summarized using descriptive statistics (means, standard deviation (SD), frequencies, and percentages). EQ-5D-5L dimensions were compared by participant’s characteristics and ARC scores using T-, Chi-square, or Fisher’s exact tests. Variables significant at p < 0.1 were entered into multivariable logistic regression models to explore their relationships with each EQ-5D-5L dimension. Results of p < 0.05 were considered significant. Analyses were computed using Stata/MP 16 (52).

The mean age in our sample was 36.0 (SD = 8.9). Most participants were 35 years or older (50.7%; mean age = 42.6, SD = 7.3), non-Hispanic White (68.4%), heterosexual (82.8%), male (58.9%), single or never married (62.1%), unemployed (66.0%; 5.4% were unemployed, disabled), attended some college or had a college degree (50.1%), and engaged in polydrug use in the past 30 days (75.5%). Only 8.7% had a high risk for hazardous drinking. The mean scores for social, personal, and total RC were 21.36 (SD = 3.50), 21.39 (SD = 3.60), and 42.75 (SD = 6.63), respectively (Table 2). The mean score for the mobility dimension was 1.28 (SD = 0.67), self-care 1.08 (SD = 0.37), usual activities 2.01 (SD = 1.15), pain/discomfort 2.01 (SD = 1.15), and anxiety/depression 2.46 (SD = 1.16).

Table 1 describes the five levels of self-reported 5Q-5D-5L problems by RC. Most participants with high social RC reported no problems in the mobility (84.0%), self-care (95.7%), usual activities (89.2%), and pain/discomfort (50.0%) dimensions, while 31.0% reported feeling slightly anxious/depressed, and 30.6% reported no anxiety/depression. Most participants with high personal RC reported no problems in the mobility (86.9%), self-care (98.0%), usual activities (91.8%), and pain/discomfort (53.9%) dimensions, while 32.6% reported feeling slightly anxious/depressed and 31.0% reported no anxiety/depression. Most participants with high total RC reported no mobility (85.5%), self-care (97.0%), usual activities (90.6%), and pain/discomfort (53.0%) problems. 32.5% reported feeling anxious/depressed, and 32.5% reported feeling slightly anxious/depressed.

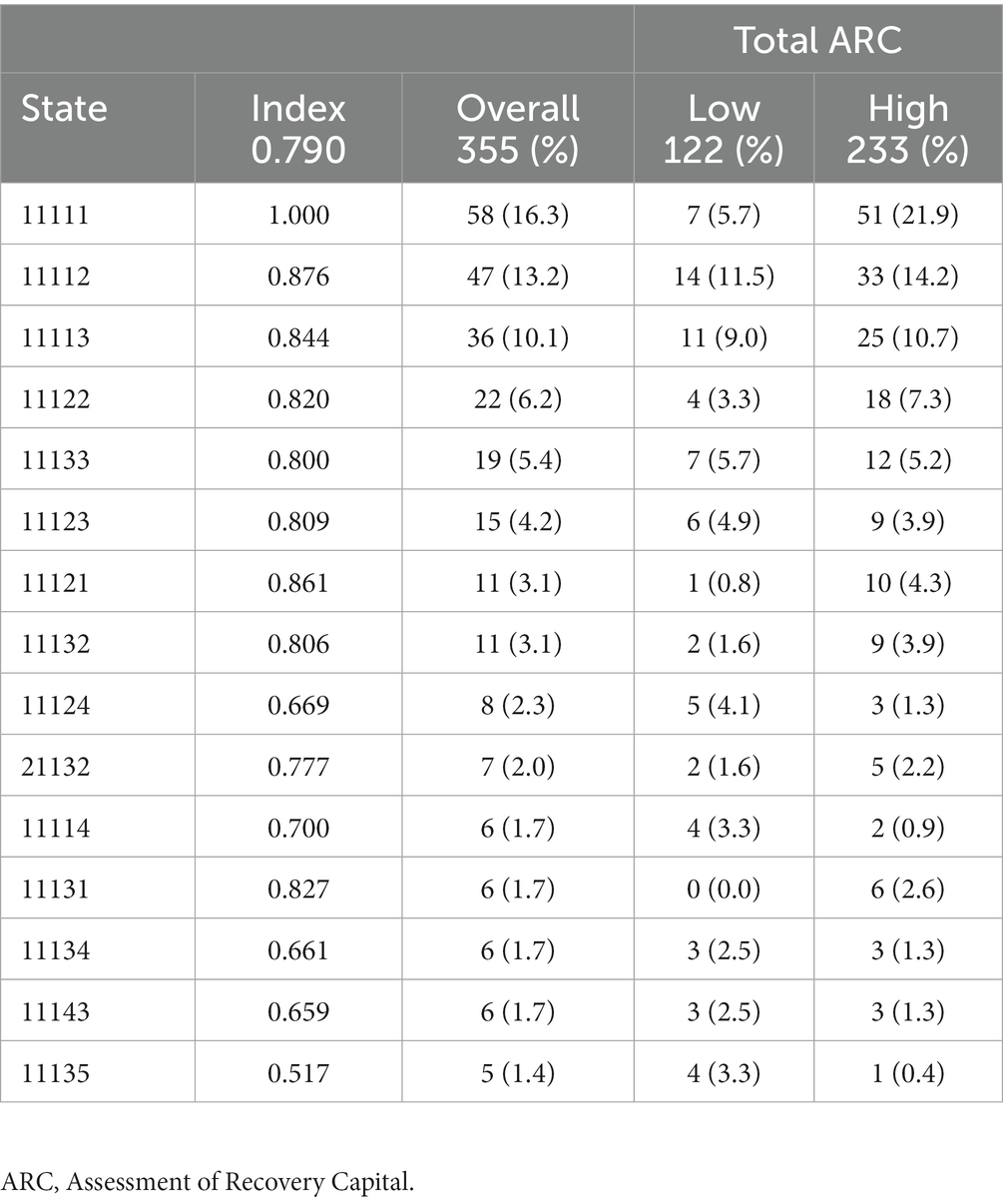

Table 3 summarizes the most frequently reported EQ-5D-5L health states and their index values by total ARC scores. Participants self-assigned 83 EQ-5D-5L health states out of a possible 3,125 health states. The most frequent 15 states (11111, 11112, 11113, 11122, 11133, 11123, 11121, 11132, 11124, 21132, 11114, 11131, 11134, 11143, and 11135) accounted for 74.1% of participants. Only 58 participants (16.3%) self-assigned health state 11111, i.e., full health, meaning no problem on any HRQOL dimension. Our sample’s overall mean EQ-5D-5L index was 0.79 (SD = 0.16). Table 4 summarizes univariate and bivariate associations between participants’ sociodemographic characteristics, substance use, comorbidities, RC, and EQ-5D-5L dimensions. Overall, the highest proportion of participants reporting any problem was in the anxiety/depression dimension (78.4%), followed by pain/discomfort (55.7%), mobility (19.3%), usual activities (15.5%), and self-care (6.8%). Most participants had high social (65.4%), personal (69.0%), and total (65.6%) RC.

Table 3. Frequently reported EQ-5D-5L health states by total recovery capital (overall index = 0.790; SD = 0.16).

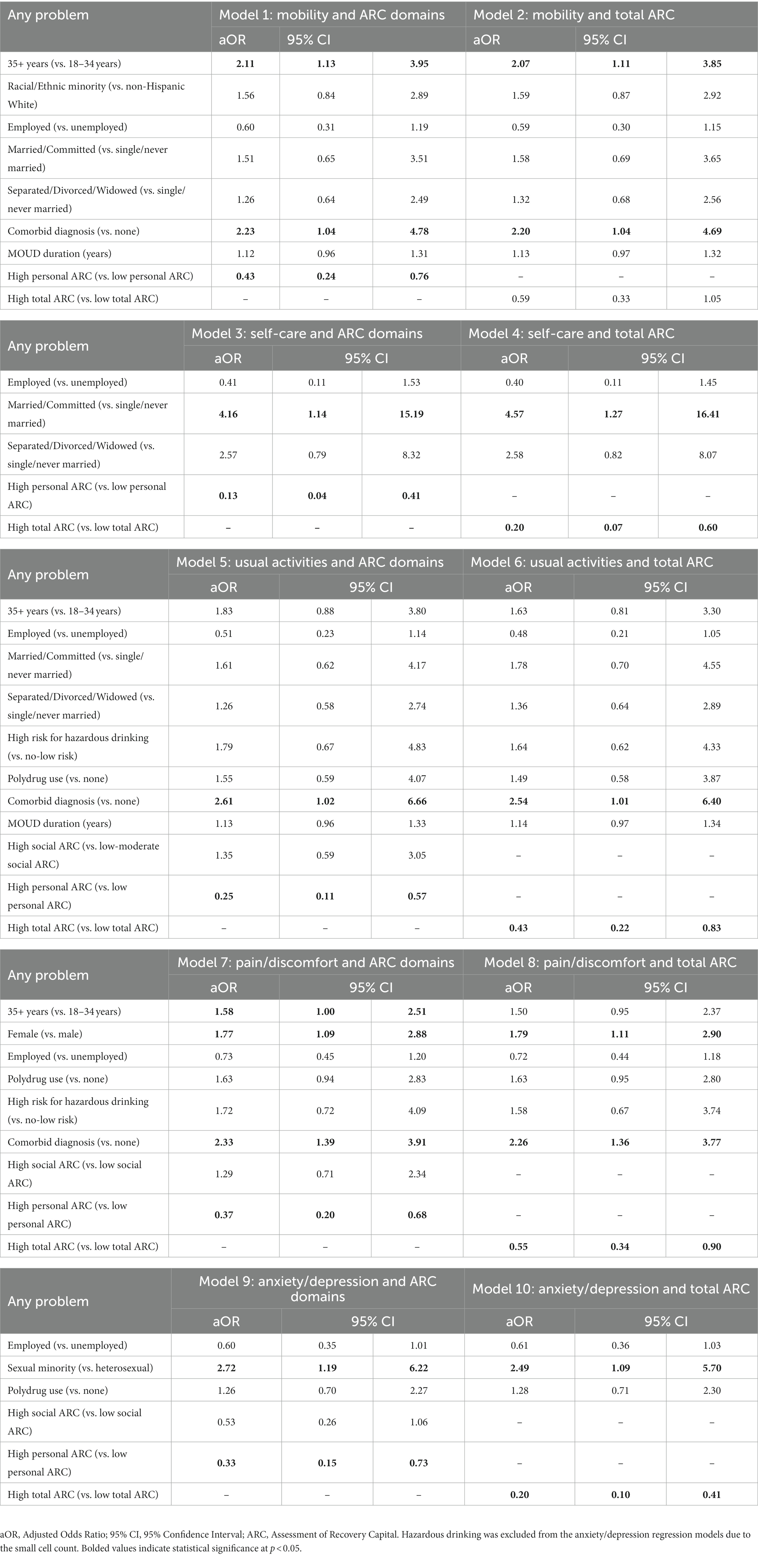

In Table 4, significant bivariate associations were age, race/ethnicity, employment, marital status, comorbid diagnoses, MOUD duration, and personal and total RC. Most participants with mobility problems had high total RC (51.6%), while half had high personal RC. Multivariable logistic regression analyses of EQ-5D-5L dimension by participant factors are summarized in Table 5. Age 35+ years (Model 1: aOR = 2.11, CI = 1.13–3.95; Model 2: aOR = 2.07, CI = 1.141–3.85), comorbid diagnoses (Model 1: aOR = 2.23, CI = 1.04–4.78, Model 2: aOR = 2.20, CI = 1.04–4.69), and low personal RC (Model 1: aOR = 0.43, CI = 0.24–0.76) were associated with mobility problems. There were no significant associations between mobility problems and social and total RC.

Table 5. Covariate adjusted multivariable logistic regression to predict any problems in each EQ-5D-5L health state by ARC scores and participants’ characteristics.

In Table 4, significant bivariate associations were employment, marital status, and personal and total RC. Most participants who reported problems conducting self-care had low personal (73.7%) and total (68.4%) RC. In Table 5, marital status- married/common-law marriage/committed relationship (Model 3: aOR = 4.16, CI = 1.14–15.19; Model 4: aOR = 4.57, CI = 1.27–16.41), low personal RC (Model 3: aOR = 0.13, CI = 0.04–0.41), and total RC (Model 4: aOR = 0.20, CI = 0.07–0.60) were associated with problems conducting self-care. There was no significant association between social RC and self-care problems.

In Table 4, significant bivariate associations were age, employment, marital status, hazardous drinking, polydrug use, comorbid diagnoses, MOUD duration, and social, personal, and total RC. In Table 5, most participants who reported problems conducting usual activities had high social RC (67.4%) and low personal (58.3%) and total (56.3%) RC. Comorbid diagnosis (Model 5: aOR = 2.61, CI = 1.02–6.66, Model 6: aOR = 2.54, CI = 1.01–6.40) and low personal (Model 5: aOR = 0.25, CI = 0.11–0.57) and total (Model 6: aOR = 0.43, CI = 0.22–0.83) RC were associated with problems conducting usual activities. There was no significant association between social RC and the usual activities dimension.

In Table 4, significant bivariate associations were age, sex at birth, employment, hazardous drinking, polydrug use, comorbid diagnoses, and social, personal, and total RC. Most participants who reported pain/discomfort problems had high social (61.4%), personal (59.8%), and total (57.7%) RC. In Table 5, age 35 + years (Model 7: aOR = 1.58, CI = 1.00–2.51), female sex (Model 7: aOR = 1.77, CI = 1.09–2.88; Model 8: aOR = 1.79, CI = 1.11–2.90), comorbid diagnoses (Model 7: aOR = 2.33, CI = 1.39–3.91, Model 8: aOR = 2.26, CI = 1.36–3.77), and low personal (Model 7: aOR = 0.37, CI = 0.20–0.68) and total (Model 8: aOR = 0.55, CI = 0.34–0.90) were associated with pain/discomfort problems. There were no significant associations between social RC and pain/discomfort problems.

In Table 4, significant bivariate associations were sexual orientation, employment, hazardous drinking, polydrug use, and social, personal, and total RC. Most participants who reported anxiety/depression problems had high social (59.9%), personal (62.8%), and total (58.4%) RC. In Table 5, sexual minority orientation (Model 9: aOR = 2.72, CI = 1.19–6.22; Model 10: aOR = 2.49, CI = 1.09–5.70) and low personal (Model 9: aOR = 0.33, CI = 0.15–0.73) and total (Model 10: aOR = 0.20, CI = 0.10–0.41) RC were associated with anxiety/depression problems. There were no significant associations between social RC and anxiety/depression problems. Hazardous drinking was excluded from the regression models due to the small cell size.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the associations between RC and EQ-5D-5L HRQOL, described as frequencies of reported problems across five dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression), among recovery residents taking MOUD in the United States. Our findings add new evidence to the growing literature on RC and HRQOL among recovery residents with OUD. We identified the health dimensions most affected by OUD and comorbid health conditions, summarized the frequency of problems across each dimension, measured the levels of RC and HRQOL problems, examined their associations, and identified strong predictors of poor HRQOL. Our findings can improve our understanding of RC and HRQOL among recovery residents with OUD. With improved understanding, health planners, recovery home administrators/operators, and policy-makers can strengthen recovery residence-based care systems through resource allocation and prioritization.

Most of our study participants self-assigned low HRQOL. Participants 35 years and older were more likely to report mobility and pain/discomfort problems than younger participants. Our findings are concerning because this is a younger sample self-reporting mobility and pain/discomfort problems, contrasting with research that demonstrated mobility problems and chronic pain are common among older adults with OUD (53, 54) and the general population (55, 56), and predictors of SUDs in older adults (57).

Our findings indicate that recovery residents with OUD who report mobility and pain/discomfort problems require special attention for several reasons. First, the most frequently reported comorbidities in our sample were mental health, respiratory, neurological, cardiovascular, and musculoskeletal conditions (Supplementary Table S1), and having either of these comorbidities is associated with mobility problems, pain/discomfort problems, and problems conducting usual activities. Second, individuals with chronic pain, respiratory, neurological, cardiovascular, and musculoskeletal/degenerative diseases are frequently prescribed opioids (55, 58–60), often misuse prescription opioids (61–63), and self-medicate with illicit drugs, resulting in SUDs, including OUD (64, 65). Furthermore, mobility problems are associated with mental illness, including anxiety and depression, increased risk of falls, and cardiovascular and respiratory conditions (66). Finally, the economic cost of pain ($560 billion to $635 billion), OUD ($471 billion), fatal opioid overdose ($550 billion), injury due to fatal ($754 million) and non-fatal ($50 billion) falls, and mental and chronic health conditions, including musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, and respiratory diseases (an estimated 90% of the United States $4.1 trillion yearly healthcare expenditure), which are attributed to direct healthcare costs, lost wages, impaired QOL, and value of statistical life, cost the United States trillions of dollars, annually (67–71).

Recovery housing provides individuals with SUDs with ongoing support, structure, and life skills building, such as healthy eating and regular exercising, to improve their physical health. Recovery housing-based systems can be leveraged to link residents with interdisciplinary healthcare professionals to provide individualized treatment for their comorbid mental and physical health conditions, including pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical pain management methods. The high rates of self-reported mobility and pain/discomfort problems increase residents’ risks for other comorbid conditions, polysubstance use, and relapse, underscoring the need to screen residents for pain and mobility problems and continuously monitor polysubstance use and safety to prevent opioid-related overdose deaths. Also, recovery housing staff should be trained to assess residents’ functional limitations.

We found that female residents were more likely to report pain/discomfort problems than male residents, consistent with research that demonstrated pain prevalence and severity appear higher among women (72, 73). Although the precise underlying mechanisms that drive this disparity in pain level are obscure, it has been proposed that interrelated biological and psychosocial factors may contribute to these disparities (73–79). For instance, sex differences might exist in how the opioid receptors are activated in response to pain. Further, men and women are differently socialized to talk about and cope with painful experiences, including adverse childhood experiences. Thus, when compared to men, women will more often employ a diverse set of coping strategies, including relying on social support, while men typically use behavioral distraction or problem-focused approaches (77, 80). There are potential advantages in providing comprehensive, integrated care models that do not place the blame on female residents experiencing pain. Rather, interventions might be needed to support recovery residences’ staff to link female residents to trauma-informed outpatient treatment programs and other services, including social support and mutual aid groups, which are central to improving substance use outcomes (81, 82). While sex differences existed in our sample only on the pain/discomfort dimension, other differences may exist. Future research with larger samples should explore sex differences across all HRQOL dimensions.

Participants who are married or in a committed relationship were more likely to report problems conducting self-care than single or never-married participants, contrary to previous research that reported married individuals have better HRQOL and health than single, divorced/separated, or bereaved individuals (83–85). This contrasting result may be because residents’ partners also engage in opioid or other substance use, highlighting the need to provide behavioral couples therapy to residents and their married or cohabiting partners.

The highest proportion of participants reporting any HRQOL problem was in the anxiety/depression dimension. Anxiety and depression frequently co-occur with OUD and are risk factors for opioid misuse and OUD (15, 17). We also found that sexual minorities were more likely to report anxiety/depression problems than heterosexuals, consistent with previous researchers’ findings that indicate sexual minorities have poorer HRQOL, and gay/bisexual men are more likely to report anxiety/depression problems than heterosexuals (86). Given that sexual minorities report worse health outcomes, including anxiety, depression, poor HRQOL, and health-related behaviors, than heterosexuals due to stigma and discrimination (86–88), culturally competent co-occurring mental health and SUDs treatment and support must be integrated into recovery residence-based systems of care.

Most participants had high total, social, and personal RC, consistent with research that reported individuals with higher RC are more likely to identify and access substance use treatment than those with lower RC (89). Low personal RC was associated with problems in all HRQOL dimensions. Similarly, low total RC was associated with HRQOL problems, except mobility problems. Personal RC includes mental and physical health and education/vocational skills (41, 42). Indeed, most participants had attended some college or had a vocational/technical diploma or college degree and reported comorbid mental and physical diagnoses, which may account for the differences in HRQOL by personal RC observed. The presence of comorbid mental and physical conditions may be due to OUD or exacerbated by OUD, which decreases HRQOL (12). Future research should identify and assess the effects of all types of personal RC on HRQOL so recovery staff will better understand how to strengthen residents’ RC to support their recovery and improve their HRQOL.

The logistic regression model suggests that social RC is not associated with any HRQOL dimension. Our finding is novel compared to previous researchers that reported significant associations between social RC and HRQOL (43, 45, 90). White and Cloud (42) suggest that long-term recovery is predicted by social and personal RC, with the impact of low personal RC being regulated by high social RC. Contrarily, using HRQOL as a proxy for long-term recovery, personal RC is a stronger predictor of long-term recovery, and high personal RC appears to regulate the impact of low social RC in our sample. Nonetheless, recovery homes can provide a safe and supportive environment for residents with low social RC to connect with their peers to improve their health, well-being, and recovery from OUD. This is critical as social capital, such as social support and connectedness obtained from social networks and supportive relationships, are protective against substance use, anxiety, and depression (41, 42, 91–93).

Our results should be interpreted with caution due to several limitations. First, our analysis has a cross-sectional design, limiting our ability to assess causal relationships. Second, most participants were non-Hispanic White and resided in levels II and III certified recovery homes across five cities in Texas. Therefore, our findings may not be generalizable to other individuals with OUD. Furthermore, our analysis of RC and HRQOL relied on self-reported data, which may introduce social desirability and recall bias. Also, with a larger sample size, potentially meaningful differences that were not statistically significant in our sample might have been identified, e.g., sex differences across all HRQOL dimensions and not just the pain/discomfort dimension alone. Finally, the ARC scale assesses only two of the five RC domains; thus, total RC in our study refers to only the social and personal resources that residents can draw upon to initiate and sustain their recovery from OUD. Nonetheless, personal RC is the stronger predictor of HRQOL and long-term recovery among recovery residents with OUD.

Our analysis of data from individuals taking MOUD and residing in levels II and III recovery homes indicates that most residents have high RC. However, personal RC is a stronger predictor of HRQOL than social RC. Our findings underscore the importance of examining each RC domain and increasing RC to influence the HRQOL of individuals with OUD. We also found that comorbid conditions, including mental illness, respiratory, neurological, musculoskeletal, and cardiovascular diseases, are highly prevalent and negatively impact HRQOL. Our results emphasize the need for policymakers to support the integration of MOUD and treatment for comorbid conditions, especially mental illness and chronic physical health conditions that result in pain, mobility issues, and problems conducting usual activities. Recovery is multidimensional and lifelong; thus, researchers and recovery residence administrators/staff should be trained to identify and understand RC and its influences on HRQOL to strengthen residents’ existing or develop new RC. Recovery providers can support residents’ recovery to improve opioid use outcomes and HRQOL by participating in intervention design, interprofessional models of care, and policies. This study adds to the HRQOL and RC literature by identifying the most frequently reported problems in five EQ-5D-5L HRQOL dimensions and predictors of poor HRQOL, i.e., female sex, sexual minority identity, married status, comorbid conditions, and low recovery capital, among recovery residents with OUD.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The studies involving humans were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects (CPHS). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

EO: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SM: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. VS: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. CM: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. KG: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Project administration. JW: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This project was supported by the Texas Targeted Opioid Response, a public health initiative operated by the Texas Health and Human Services Commission through federal funding from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration grant award 1H79TI083288. The funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study, collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data, and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

The authors would like to acknowledge the engagement and support from the staff of the recovery homes and residents participating in Project HOMES.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the official policies of the Department of Health and Human Services or Texas Health and Human Services, nor does any mention of trade names, commercial practices, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. or Texas Government.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1284192/full#supplementary-material

aOR, Adjusted Odds Ratio; 95% CI, 95% Confidence Interval; HIPAA, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act; HRQOL, Health-Related Quality of Life; MOUD, Medication for Opioid Use Disorder; OUD, Opioid Use Disorder; RC, Recovery Capital; SUDs, Substance Use Disorders.

1. Simirea, M, Baumann, C, Bisch, M, Rousseau, H, Di Patrizio, P, Viennet, S, et al. Health-related quality of life in outpatients with substance use disorder: evolution over time and associated factors. Health Qual Life Outcomes. (2022) 20:26. doi: 10.1186/s12955-022-01935-9

2. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2022). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2021 National Survey on drug use and health (NSDUH). Available at: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2021-nsduh-annual-national-report (Accessed February 10, 2023).

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2022). Drug overdose deaths. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/deaths/index.html (Accessed February 10, 2023).

4. Chen, Q, Griffin, PM, and Kawasaki, SS. Disability-adjusted life-years for drug overdose crisis and COVID-19 are comparable during the two years of pandemic in the United States. Value Health. (2022) 26:796–801. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2022.11.010

5. Bray, JW, Aden, B, Eggman, AA, Hellerstein, L, Wittenberg, E, Nosyk, B, et al. Quality of life as an outcome of opioid use disorder treatment: a systematic review. J Subst Abus Treat. (2017) 76:88–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.01.019

6. Groshkova, T, Best, D, and White, W. The assessment of recovery capital: properties and psychometrics of a measure of addiction recovery strengths. Drug Alcohol Rev. (2013) 32:187–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2012.00489.x

7. Desalvo, KB, Bloser, N, Reynolds, K, Jiang, HE, and Muntner, P. Mortality prediction with a single general self-rated health question: a meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. (2006) 21:267–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00291.x

8. Dominick, KL, Ahern, FM, Gold, CH, and Heller, DA. Relationship of health-related quality of life to health care utilization and mortality among older adults. Aging Clin Exp Res. (2002) 14:499–508. doi: 10.1007/BF03327351

9. Rhee, TG, and Rosenheck, RA. Association of current and past opioid use disorders with health-related quality of life and employment among US adults. Drug Alcohol Depend. (2019) 199:122–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.03.004

10. Nosyk, B, Guh, DP, Sun, H, Oviedo-Joekes, E, Brissette, S, Marsh, DC, et al. Health related quality of life trajectories of patients in opioid substitution treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. (2011) 118:259–64. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.04.003

11. Webster, LR. Risk factors for opioid-use disorder and overdose. Anesth Analg. (2017) 125:1741–8. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000002496

12. National Institutes on Drug Abuse (NIDA). (2020). Common comorbidities with substance use disorders research report. Available at: https://nida.nih.gov/publications/research-reports/common-comorbidities-substance-use-disorders/introduction (Accessed February 10, 2023).

13. Zhu, Y, Mooney, LJ, Yoo, C, Evans, EA, Kelleghan, A, Saxon, AJ, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity and treatment outcomes in patients with opioid use disorder: results from a multisite trial of buprenorphine-naloxone and methadone. Drug Alcohol Depend. (2021) 228:108996. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108996

14. Griffin, ML, Bennett, HE, Fitzmaurice, GM, Hill, KP, Provost, SE, and Weiss, RD. Health-related quality of life among prescription opioid-dependent patients: results from a multi-site study. Am J Addict. (2015) 24:308–14. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12188

15. Langdon, KJ, Dove, K, and Ramsey, S. Comorbidity of opioid- and anxiety-related symptoms and disorders. Curr Opin Psychol. (2019) 30:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.12.020

16. Santo, T, Campbell, G, Gisev, N, Martino-Burke, D, Wilson, J, Colledge-Frisby, S, et al. Prevalence of mental disorders among people with opioid use disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. (2022) 238:109551–1. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2022.109551

17. Tumenta, T, Ugwendum, DF, Chobufo, MD, Mungu, EB, Kogan, I, and Olupona, T. Prevalence and trends of opioid use in patients with depression in the United States. Curēus. (2021) 13:e15309. doi: 10.7759/cureus.15309

18. Rajbhandari-Thapa, J, Zhang, D, Padilla, HM, and Chung, SR. Opioid-related hospitalization and its association with chronic diseases: findings from the national inpatient sample, 2011-2015. Prev Chronic Dis. (2019) 16:E157. doi: 10.5888/pcd16.190169

19. Stephenson, J, Smith, CM, Kearns, B, Haywood, A, and Bissell, P. The association between obesity and quality of life: a retrospective analysis of a large-scale population-based cohort study. BMC Public Health. (2021) 21:1990. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-12009-8

20. Ali, R, Ahmed, N, Salman, M, Daudpota, S, Masroor, M, and Nasir, M. Assessment of quality of life in bronchial asthma patients. Cureus. (2020) 12:e10845. doi: 10.7759/cureus.10845

21. Nayak, MG, George, A, Vidyasagar, MS, Mathew, S, Nayak, S, Nayak, BS, et al. Quality of life among cancer patients. Indian J Palliat Care. (2017) 23:445–50. doi: 10.4103/ijpc.Ijpc_82_17

22. Xavier, RM, Zerbini, CAF, Pollak, DF, Morales-Torres, JLA, Chalem, P, Restrepo, JFM, et al. Burden of rheumatoid arthritis on patients’ work productivity and quality of life. Adv Rheumatol. (2019) 59:47. doi: 10.1186/s42358-019-0090-8

23. Jipan, XIE, Wu, EQ, Zheng, Z-J, Croft, JB, Greenlund, KJ, Mensah, GA, et al. Impact of stroke on health-related quality of life in the noninstitutionalized population in the United States. Stroke. (2006) 37:2567–72. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000240506.34616.10

24. Dahlhamer, J, Lucas, J, Zelaya, C, Nahin, R, Mackey, S, DeBar, L, et al. Prevalence of chronic pain and high-impact chronic pain among adults—United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. (2018) 67:1001–6. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6736a2

25. Gureje, O, Von Korff, M, Simon, GE, and Gater, R. Persistent pain and well-being: a World Health Organization study in primary care. JAMA. (1998) 280:147–51. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.2.147

26. Smith, BH, Elliott, AM, Chambers, WA, Smith, WC, Hannaford, PC, and Penny, K. The impact of chronic pain in the community. Fam Pract. (2001) 18:292–9. doi: 10.1093/fampra/18.3.292

27. Nahin, RL. Estimates of pain prevalence and severity in adults: United States, 2012. J Pain. (2015) 16:769–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.05.002

28. Smith, D, Wilkie, R, Croft, P, and McBeth, J. Pain and mortality in older adults: the influence of pain phenotype. Arthritis Care Res. (2018) 70:236–43. doi: 10.1002/acr.23268

29. Compton, WM, Valentino, RJ, and DuPont, RL. Polysubstance use in the U.S. opioid crisis. Mol Psychiatry. (2021) 26:41–50. doi: 10.1038/s41380-020-00949-3

30. Kelly, PJ, Robinson, LD, Baker, AL, Deane, FP, McKetin, R, Hudson, S, et al. Polysubstance use in treatment seekers who inject amphetamine: drug use profiles, injecting practices and quality of life. Addict Behav. (2017) 71:25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.02.006

31. Donovan, D, Mattson, ME, Cisler, RA, Longabaugh, R, and Zweben, A. Quality of life as an outcome measure in alcoholism treatment research. J Stud Alcohol. (2005) 15:119–39. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2005.s15.119

32. Foster, JH, Peters, TJ, and Marshall, EJ. Quality of life measures and outcome in alcohol-dependent men and women. Alcohol. (2000) 22:45–52. doi: 10.1016/S0741-8329(00)00102-6

33. Jalali, A, Ryan, DA, Jeng, PJ, McCollister, KE, Leff, JA, Lee, JD, et al. Health-related quality of life and opioid use disorder pharmacotherapy: a secondary analysis of a clinical trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. (2020) 215:108221. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108221

34. Laudet, AB. The case for considering quality of life in addiction research and clinical practice. Addict Sci Clin Pract. (2011) 6:44–55.

35. Le, NT, Vu, TT, Vu, TTV, Khuong, QL, Le, HTCH, Tieu, TTV, et al. Quality of life profile of methadone maintenance treatment patients in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. J Subst Use. (2022) 28:692–8. doi: 10.1080/14659891.2022.2084782

36. Kelly, JF, and Hoeppner, B. A biaxial formulation of the recovery construct. Addict Res Theory. (2015) 23:5–9. doi: 10.3109/16066359.2014.930132

37. Morgen, K, Astone-Twerell, J, Hernitche, T, Gunneson, L, and Santangelo, K. Health-related quality of life among substance abusers in residential drug abuse treatment. Appl Res Qual Life. (2007) 2:239–46. doi: 10.1007/s11482-008-9040-z

38. Garner, BR, Scott, CK, Dennis, ML, and Funk, RR. The relationship between recovery and health-related quality of life. J Subst Abus Treat. (2014) 47:293–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2014.05.006

39. Cloud, W, and Granfield, R. Conceptualizing recovery capital: expansion of a theoretical construct. Subst Use Misuse. (2008) 43:1971–86. doi: 10.1080/10826080802289762

40. Dickson-Gomez, J, Spector, A, Weeks, M, Galletly, C, McDonald, M, and Green Montaque, HD. "You're not supposed to be on it forever": medications to treat opioid use disorder (MOUD) related stigma among drug treatment providers and people who use opioids. Subst Abuse. (2022) 16:11782218221103859. doi: 10.1177/11782218221103859

41. Hennessy, EA. Recovery capital: a systematic review of the literature. Addict Res Theory. (2017) 25:349–60. doi: 10.1080/16066359.2017.1297990

42. White, W, and Cloud, W. Recovery capital: a primer for addiction professionals. Counselor. (2008) 9:22–7.

43. Mawson, E, Best, D, Beckwith, M, Dingle, GA, and Lubman, DI. Social identity, social networks and recovery capital in emerging adulthood: a pilot study. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. (2015) 10:45. doi: 10.1186/s13011-015-0041-2

44. Laudet, AB, Morgen, K, and White, WL. The role of social supports, spirituality, religiousness, life meaning and affiliation with 12-step fellowships in quality of life satisfaction among individuals in recovery from alcohol and drug problems. Alcohol Treat Q. (2006) 24:33–73. doi: 10.1300/J020v24n01_04

45. Magasi, S, Wong, A, Gray, DB, Hammel, J, Baum, C, Wang, C-C, et al. Theoretical foundations for the measurement of environmental factors and their impact on participation among people with disabilities. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. (2015) 96:569–77. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2014.12.002

46. O’Sullivan, D, Xiao, Y, and Watts, JR. Recovery capital and quality of life in stable recovery from addiction. Rehabil Couns Bull. (2019) 62:209–21. doi: 10.1177/0034355217730395

47. National Alliance of Recovery Residences (NARR). (2011). An introduction and membership invitation from the National Association of recovery residences. Available at: https://narronline.org/resources/ (Accessed February 17, 2023).

48. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2019). Center for Mental Health Services NOMs client-level measures for discretionary programs providing direct services: services tool for adult programs. Available at: https://spars-ta.samhsa.gov/Resources/DocumentDetails (Accessed November 1, 2021).

49. EuroQol. (2019). EQ-5D-5L user guide: Basic information on how to use the EQ-5D-5L instrument. Available at: https://euroqol.org/publications/user-guides/ (Accessed April 5, 2022).

50. Saunders, JB, Aasland, OG, Babor, TF, De La Fuente, JR, and Grant, M. Development of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-II. Addiction. (1993) 88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x

51. Obekpa, EO, McCurdy, SA, Schick, V, Markham, C, Gallardo, KR, and Wilkerson, JM. Situational confidence and recovery capital among recovery residents taking medications for opioid use disorder in Texas. J Addict Med. (2023) 17:670–676. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000001206

53. Potru, S, and Tang, YL. Chronic pain, opioid use disorder, and clinical management among older adults. Focus. (2021) 19:294–302. doi: 10.1176/appi.focus.20210002

54. Dagnino, A, and Campos, MM. Chronic pain in the elderly: mechanisms and perspectives. Front Hum Neurosci. (2022) 16:736688. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2022.736688

55. Reid, MC, Eccleston, C, and Pillemer, K. Management of chronic pain in older adults. BMJ. (2015) 350:h532. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h532

56. Schwan, JMD, Sclafani, JMD, and Tawfik, VLMDP. Chronic pain management in the elderly. Anesthesiol Clin. (2019) 37:547–60. doi: 10.1016/j.anclin.2019.04.012

57. Aas, CF, Vold, JH, Skurtveit, S, Lim, AG, Ruths, S, Islam, K, et al. Health-related quality of life of long-term patients receiving opioid agonist therapy: a nested prospective cohort study in Norway. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. (2020) 15:68. doi: 10.1186/s13011-020-00309-y

58. Dowell, D, Haegerich, TM, and Chou, R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—United States, 2016. JAMA. (2016) 315:1624–45. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1464

59. Le, TT, Park, S, Choi, M, Wijesinha, M, Khokhar, B, and Simoni-Wastila, L. Respiratory events associated with concomitant opioid and sedative use among medicare beneficiaries with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. BMJ Open Respir Res. (2020) 7:e000483. doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2019-000483

60. Liew, SM, Chowdhury, EK, Ernst, ME, Gilmartin-Thomas, J, Reid, CM, Tonkin, A, et al. Prescribed opioid use is associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes in community-dwelling older persons. ESC Heart Fail. (2022) 9:3973–84. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.14101

61. Garland, EL, Froeliger, B, Zeidan, F, Partin, K, and Howard, MO. The downward spiral of chronic pain, prescription opioid misuse, and addiction: cognitive, affective, and neuropsychopharmacologic pathways. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2013) 37:2597–607. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.08.006

62. Krantz, MJ, Palmer, RB, and Haigney, MCP. Cardiovascular complications of opioid use: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2021) 77:205–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.002

63. Genberg, BL, Astemborski, J, Piggott, DA, Woodson-Adu, T, Kirk, GD, and Mehta, SH. The health and social consequences during the initial period of the COVID-19 pandemic among current and former people who inject drugs: a rapid phone survey in Baltimore, Maryland. Drug Alcohol Depend. (2021) 221:108584. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108584

64. Ilgen, MA, Perron, B, Czyz, EK, McCammon, RJ, and Trafton, J. The timing of onset of pain and substance use disorders. Am J Addict. (2010) 19:409–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2010.00065.x

65. Alford, DP, German, JS, Samet, JH, Cheng, DM, Lloyd-Travaglini, CA, and Saitz, R. Primary care patients with drug use report chronic pain and self-medicate with alcohol and other drugs. J Gen Intern Med. (2016) 31:486–91. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3586-5

66. Iezzoni, LI, McCarthy, EP, Davis, RB, and Siebens, H. Mobility difficulties are not only a problem of old age. J Gen Intern Med. (2001) 16:235–43. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016004235.x

67. Luo, F, Li, M, and Florence, C. State-level economic costs of opioid use disorder and fatal opioid overdose- United States, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. (2021) 70:541–6. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7015a1

68. Peterson, C, Miller, GF, Barnett, SBL, and Florence, C. Economic cost of injury - United States, 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. (2021) 70:1655–9. doi: 10.15585/MMWR.MM7048A1

69. Florence, CS, Bergen, G, Atherly, A, Burns, E, Stevens, J, and Drake, C. Medical costs of fatal and nonfatal falls in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2018) 66:693–8. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15304

70. Haddad, YK, Bergen, G, and Florence, CS. Estimating the economic burden related to older adult falls by state. J Public Health Manag Pract. (2019) 25:E17–24. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000816

71. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2023). Health and economic costs of chronic diseases. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/about/costs/index.htm (Accessed August 27, 2023).

72. Huhn, AS, Tompkins, DA, Campbell, CM, and Dunn, KE. Individuals with chronic pain who misuse prescription opioids report sex-based differences in pain and opioid withdrawal. Pain Med. (2019) 20:1942–7. doi: 10.1093/pm/pny295

73. Gerdle, B, Björk, J, Cöster, L, Henriksson, K, Henriksson, C, and Bengtsson, A. Prevalence of widespread pain and associations with work status: a population study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. (2008) 9:102–2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-9-102

74. Manubay, J, Davidson, J, Vosburg, S, Jones, J, Comer, S, and Sullivan, M. Sex differences among opioid-abusing patients with chronic pain in a clinical trial. J Addict Med. (2015) 9:46–52. doi: 10.1097/adm.0000000000000086

75. Jamison, RN, Butler, SF, Budman, SH, Edwards, RR, and Wasan, AD. Gender differences in risk factors for aberrant prescription opioid use. J Pain. (2010) 11:312–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.07.016

76. Lumley, MA, Cohen, JL, Borszcz, GS, Cano, A, Radcliffe, AM, Porter, LS, et al. Pain and emotion: a biopsychosocial review of recent research. J Clin Psychol. (2011) 67:942–68. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20816

77. Bartley, EJ, and Fillingim, RB. Sex differences in pain: a brief review of clinical and experimental findings. Br J Anaesth. (2013) 111:52–8. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet127

78. Brown, RC, Plener, PL, Braehler, E, Fegert, JM, and Huber-Lang, M. Associations of adverse childhood experiences and bullying on physical pain in the general population of Germany. J Pain Res. (2018) 11:3099–108. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S169135

79. Bondesson, E, Larrosa Pardo, F, Stigmar, K, Ringqvist, Å, Petersson, IF, Jöud, A, et al. Comorbidity between pain and mental illness – evidence of a bidirectional relationship. Eur J Pain. (2018) 22:1304–11. doi: 10.1002/ejp.1218

80. Unruh, AM, Ritchie, J, and Merskey, H. Does gender affect appraisal of pain and pain coping strategies? Clin J Pain. (1999) 15:31–40. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199903000-00006

81. Polcin, DL, and Korcha, R. Social support influences on substance abuse outcomes among sober living house residents with low and moderate psychiatric severity. J Alcohol Drug Educ. (2017) 61:51–70.

82. Mericle, AA, Slaymaker, V, Gliske, K, Ngo, Q, and Subbaraman, MS. The role of recovery housing during outpatient substance use treatment. J Subst Abus Treat. (2022) 133:108638. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108638

84. Tun, S, Balasingam, V, and Singh, DS. Factors associated with quality of life (QOL) scores among methadone patients in Myanmar. PLoS Glob Public Health. (2022) 2:e0000469–9. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0000469

85. Han, KT, Park, EC, Kim, JH, Kim, SJ, and Park, S. Is marital status associated with quality of life? Health Qual Life Outcomes. (2014) 12:109. doi: 10.1186/s12955-014-0109-0

86. Marti-Pastor, M, Perez, G, German, D, Pont, A, Garin, O, Alonso, J, et al. Health-related quality of life inequalities by sexual orientation: results from the Barcelona health interview survey. PLoS One. (2018) 13:e0191334. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0191334

87. Pascoe, EA, and Smart Richman, L. Perceived discrimination and health: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. (2009) 135:531–54. doi: 10.1037/a0016059

88. Meyer, IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull. (2003) 129:674–97. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

89. Wen, H, Hockenberry, JM, Borders, TF, and Druss, BG. Impact of Medicaid expansion on Medicaid-covered utilization of buprenorphine for opioid use disorder treatment. Med Care. (2017) 55:336–41. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000703

90. Best, D, Gow, J, Knox, T, Taylor, A, Groshkova, T, and White, W. Mapping the recovery stories of drinkers and drug users in Glasgow: quality of life and its associations with measures of recovery capital. Drug Alcohol Rev. (2012) 31:334–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2011.00321.x

91. Breton, JJ, Labelle, R, Berthiaume, C, Royer, C, St-Georges, M, Ricard, D, et al. Protective factors against depression and suicidal behaviour in adolescence. Can J Psychiatr. (2015) 60:S5–S15. doi: 10.1016/j.neurenf.2012.05.152

92. Dailey, SF, Parker, MM, and Campbell, A. Social connectedness, mindfulness, and coping as protective factors during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Couns Dev. (2023) 101:114–26. doi: 10.1002/jcad.12450

Keywords: health-related quality of life, EQ-5D-5L, recovery capital, opioid use disorder, medication for opioid use disorder, recovery homes, sober living homes

Citation: Obekpa EO, McCurdy SA, Schick V, Markham CM, Gallardo KR and Wilkerson JM (2023) Health-related quality of life and recovery capital among recovery residents taking medication for opioid use disorder in Texas. Front. Public Health. 11:1284192. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1284192

Received: 28 August 2023; Accepted: 27 October 2023;

Published: 20 November 2023.

Edited by:

Wendy Margaret Walwyn, University of California, Los Angeles, United StatesReviewed by:

Louis Trevisan, Creighton University, United StatesCopyright © 2023 Obekpa, McCurdy, Schick, Markham, Gallardo and Wilkerson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Elizabeth O. Obekpa, ZWxpemFiZXRoLm8ub2Jla3BhQHV0aC50bWMuZWR1

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.