- 1School of Architecture and Art, Central South University, Changsha, Hunan, China

- 2School of Art and Design, Hunan First Normal University, Changsha, Hunan, China

- 3Department of the Built Environment, Eindhoven University of Technology, Eindhoven, Netherlands

- 4Graduate School of Advanced Science and Engineering, Hiroshima University, Hiroshima, Japan

- 5School of Architecture, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China

Introduction: The effects of restoration and inspiration in the therapeutic landscape of natural environments on visitors during the COVID-19 pandemic have been well-documented. However, less attention has been paid to the heterogeneity of visitor perceptions of health and the potential impacts of experiences in wetland parks with green and blue spaces on visitors’ overall perceived health. In this study, we investigate the impact of the restorative landscapes of wetland parks on visitors’ health perceptions in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

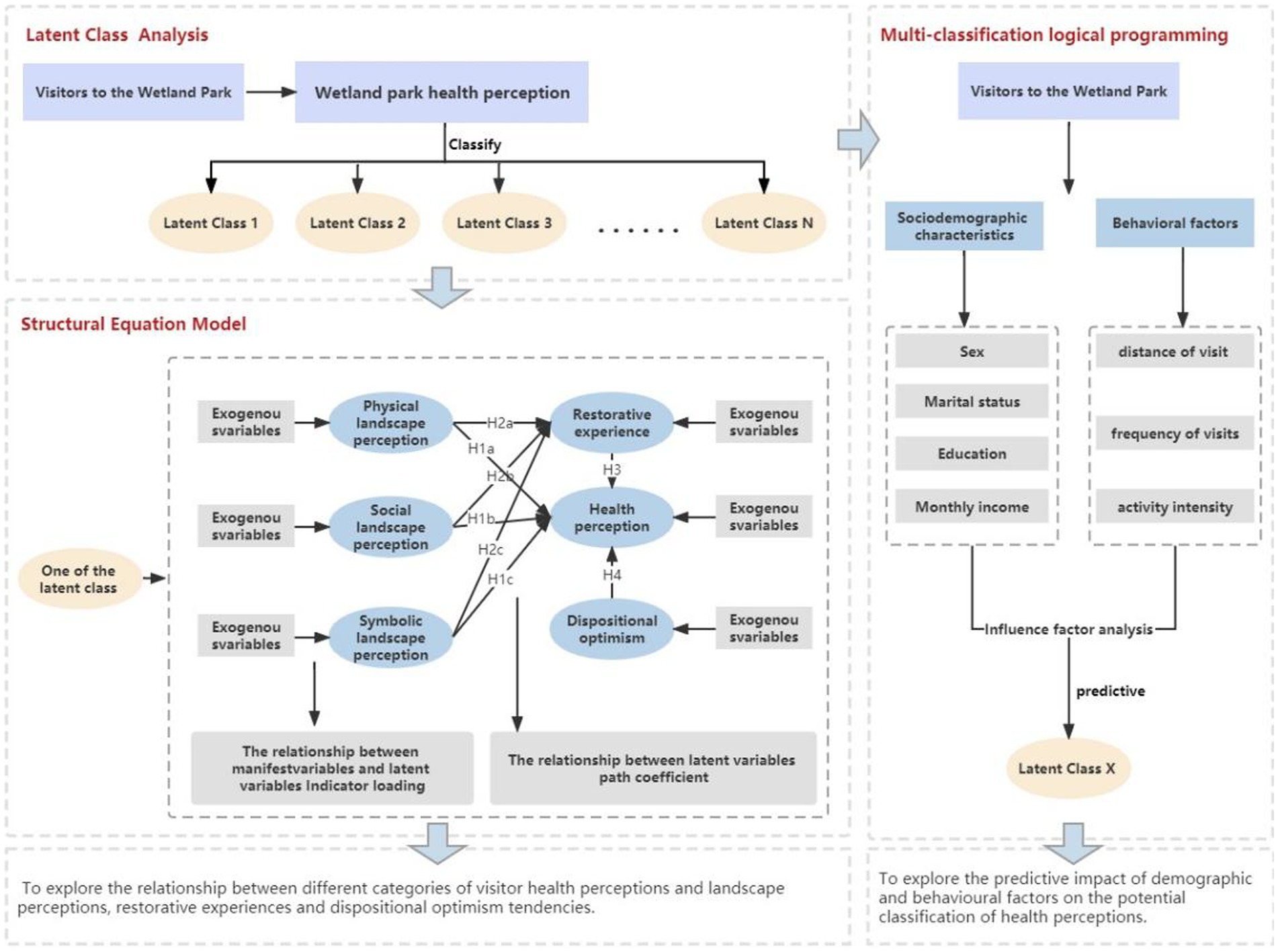

Methods: In our survey, 582 respondents participated in an online questionnaire. We analyzed the respondents’ health perceptions in terms of latent class analysis, used multinomial logistic regression to determine the factors influencing the potential categorization of health perceptions, and used structural equation modeling to validate the relationships between health perceptions of different groups and landscape perceptions of wetland parks, restorative experiences, and personality optimistic tendencies.

Results: The results identified three latent classes of health perceptions. Gender, marital status, education, occupation, income, distance, frequency of activities, and intensity of activities were significant predictors of potential classes of perceived health impacts among wetland park visitors.

Discussion: This study revealed the nature and strength of the relationships between health perception and landscape perception, restorative experience, and dispositional optimism tendencies in wetland parks. These findings can be targeted not only to improve visitor health recovery but also to provide effective references and recommendations for wetland park design, planning, and management practices during and after an epidemic.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a profound impact on human society (1). Although control measures have calmed the outbreak, they have also exacerbated mental health problems (2, 3). A growing body of literature underlines the importance of extended psychological and physical health distress during the COVID-19 epidemic (4, 5), which is considered a public health concern. Although people may suffer from many adverse effects on their health during an epidemic, such as fear of viral infection, prolonged isolation, and other complex factors, people with optimistic dispositions tend to ease stress and anxiety caused by the epidemic because of their positive psychological cues, improve their physical health, seek social interactions to fulfill their social roles, and maintain their intrinsic mental and emotional health (6, 7).

Natural areas can provide an escape from mundane urban life (8). Many studies have suggested that natural connectivity in a therapeutic landscape provides a comfortable and healing environment for tourism and recreation (8–10). This reduction in mental and physical resources can be offset by access to a therapeutic environment (11, 12). Thus, visits to wetland parks, which are special parks with therapeutic landscapes in urban areas, may effectively prevent anxiety and depression caused by short- and long-term quarantines and lockdowns in natural environments (13–15). Wetland parks in urban areas improve water and air quality, support biodiversity, and promote human comfort (16, 17). However, less attention has been paid to the important role of therapeutic landscapes in urban wetland parks in healing, restoring, and maintaining human health (18–20). Therefore, it is paramount to understand how the experience of wetland parks benefits visitors’ perceived health. This study attempts to broaden the knowledge of how the experience of wetland parks’ therapeutic environment affects people’s health perceptions.

In addition, evidence shows differences in individuals’ perceptions of their health status based on gender, age, personality traits, and cultural background. These heterogeneities can directly influence visitors’ attitudes and behaviors toward health issues. Highly preferable and stimulating landscapes in wetland parks can improve people’s mental state and promote physical wellbeing. However, factors such as social background and personal preferences differ between individuals, leading to differences in their subjective perceptions of health. Therefore, understanding the heterogeneity of visitors’ health perceptions during their visit to wetland parks is important for improving their health status. Heterogeneity in health perceptions has become an important issue in several fields, including social psychology and behavioral medicine. However, academic research on health perception in wetland parks is lacking. Therefore, further research is needed to understand the heterogeneity in the health perceptions of wetland park visitors and guide the planning and management of wetland park landscapes.

The following section proposes a comprehensive framework through which we explore the nature and strength of the relationships between people’s perceived health and their experiences with the therapeutic landscape in terms of landscape perception, restorative experiences, and dispositional optimism tendencies in wetland parks. This is followed by a description of the methods used for data collection and modeling approaches, including latent class analysis (LCA) and structural equation modeling (SEM). Based on these results, the key findings and discussion are presented in Section 4. Finally, conclusions and implications are presented in the last section.

2. Conceptual framework and hypothesis

The landscape comprises physical, social, and symbolic aspects (21). People perceive the physical landscape as the interaction between individuals and the natural and built environments (22). The park, which is characterized by highly visible mowed areas, open water, and flourishing planting mixtures, provides a diverse and picturesque landscape for visitors to enjoy (23–27). It is attractive to walkers, dog walkers, and cyclists and provides space and opportunities for physical activity (28, 29). The social aspect of the landscape is perceived by individuals when they interact socially, and it includes a wide range of themes related to public attitudes, values, behaviors, and activities (30). The social aspect of the landscape benefits social integration by providing public spaces for activities that generate broad social connections and overcome people’s feelings of social isolation and exclusion (31, 32). The symbolic landscape, as a psychological cue, is associated with the public’s belief in the healing characteristics of the therapeutic environment (33–36). For example, national parks in the United States function prominently in American culture and religion, with symbolic meanings of ‘inspiration’, ‘stability’, and ‘healing’ (37).

By visiting urban wetland parks, people can access the therapeutic landscape of nature with water, diverse vegetation, open lawns, and bright flowers, resulting in substantial improvements in mood, cognitive function, and mental health (38–40). A temporary escape from the dreary pressures of work and life and immersion in nature can satisfy the need for fresh air, sunlight, water, and food, thus facilitating a restorative experience (41). Moreover, comfortable public spaces in wetland parks allow visitors to interact socially, independent of their socio-economic status (31, 32). Wetland parks provide uncrowded and undisturbed spaces for visitors seeking solitary experiences, such as meditation and independent thinking, in natural environments. In addition, visitors can achieve psychological benefits through horticultural activities that ultimately improve their perception of restoration (40).

According to the literature, an individual’s health is influenced by environmental factors, sociodemographic characteristics, and psychological traits (18, 39, 42, 43). Dispositional optimism is a positive psychological trait often associated with good health and relief from stress and anxiety (44). Therefore, experiences in wetland parks may have an impact on health perception, which may vary among individuals with various sociodemographic backgrounds and behavioral activities.

Previous studies have indicated a diversity in individuals’ health perceptions (45, 46). However, it cannot be simply determined a priori from the relevant observed variables because the unobserved heterogeneity in an individual’s perception is not necessarily captured by the variables preconceived and specified by existing theoretical and conceptual models, but it can exist outside of the previously identified variables (47). For example, the results of various studies on gender differences in health perceptions in wetland parks are mixed: Some studies have found no significant differences in health perceptions between men and women who visited wetland parks before and after the outbreak (39), while others have shown that women who visited nature reserves felt healthier than men (48). It is imperative to classify heterogeneous visitors into multiple homogeneous groups and identify appropriate treatments for wetland park planning and design. A new modeling framework (Figure 1) was developed to accurately capture the health behavior patterns and core characteristics of different populations.

3. Methodology

3.1. Methods

LCA is a finite mixture model. It is a statistical method that allows associations between exogenous indicators to be explained by an intermittent latent class so that associations between exogenous indicators are explained by the latent class and thus maintain their local independence (49, 50). LCA is used to identify unobservable classes within a population that may have similar health perceptions. It provides a medium through which results can be expressed in terms of probabilities rather than fixed deterministic conclusions (49, 51). The relationships between individuals’ landscape perceptions, restorative experiences, and dispositional optimism tendencies were analyzed separately for different classes of visitors.

The mathematical expression for LCA is shown in the following equation:

where is the joint probability of a health-perceiving visitor taking the values of a,b..z for different field attributes. is a conditional probability indicating the conditional probability that the value of the health perception field attribute A of a health perception visitor is the given value of a given health perception visitor if the visitor belongs to class t of the latent variable. is the latent class probability, which indicates the probability that a health-perceiving visitor belongs to potential class t.

The latent class probabilities are to satisfy equation (2).

Conditional probability reflects the strength of the relationship between latent and exogenous variables. The formula used is as follows:

SEM is a general statistical approach used to assess the relationships between observed and latent variables (52), and it can estimate specific path coefficients based on identified latent classes.

The equation of the measured model is as follows:

where equations (4) and (5) are the exogenous and endogenous indicators, respectively. Λ is the relationship between inventory and latent variables, and δ and ε are measurement errors.

The structural model is a path diagram reflecting the relationship between the effects of potential variables and is formulated as follows:

where η is the endogenous latent variable, ξ is the exogenous latent variable, and Β denotes the effect of the exogenous latent variable on the endogenous latent variable. Γ denotes the effect of some endogenous latent variables on other endogenous latent variables, and ζ is the regression residual.

3.2. Data collection

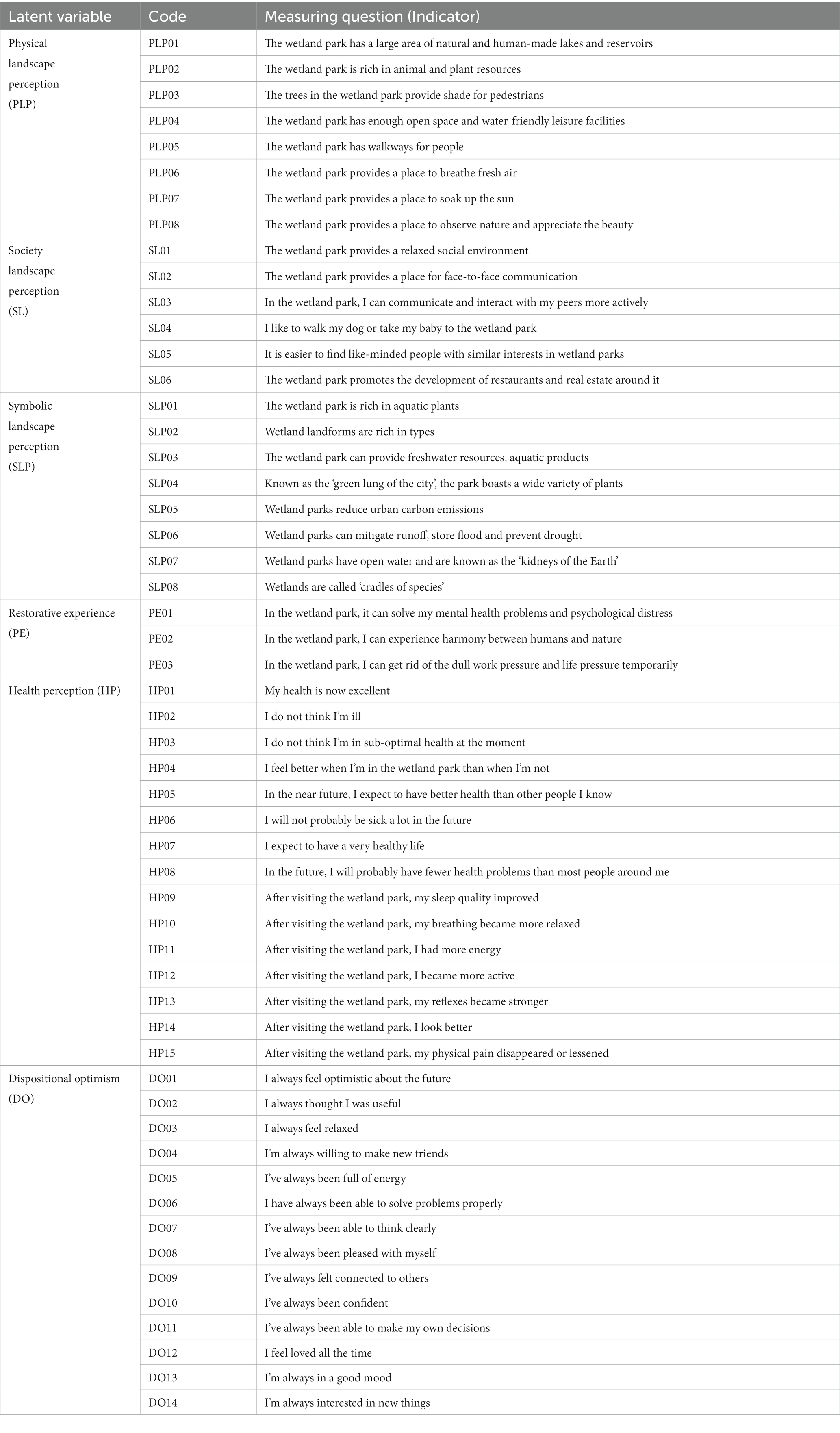

The questionnaire consisted of seven sections: (I) socio-demographics, (II) physical landscape perception, (III) social landscape perception, (IV) symbolic landscape perception, (V) restorative landscape perception, (VI) health perception, and (VII) the C-WEMWBS Warwick-Edinburgh Positive Psychology Scale. The Health Perception Scale was derived from Ware’s General Health Perception Scale (53). The Restorative Experiences Scale was derived from Korpela (54), Korpela (55), and Von Lindern et al. (56). The Dispositional Optimism Scale was derived from the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Health Scale (WEMWBS). Questionnaires were distributed across China via an online platform on 15 February 2022. Before the official questionnaire was distributed, a sample of wetland park visitors was taken for a pre-survey to verify its suitability and check for any ambiguities so that the questionnaire could be revised and improved. The survey was continued only if the respondents indicated their experience of visiting a wetland park. Table 1 shows the questionnaire form.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive statistics

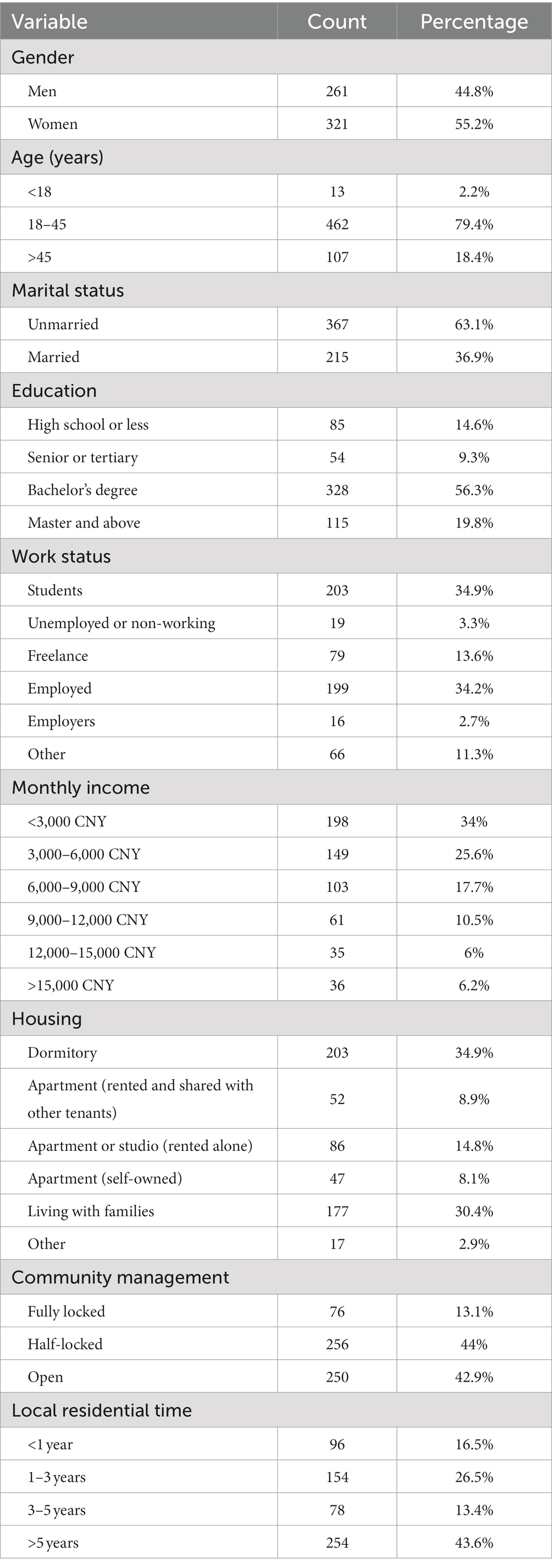

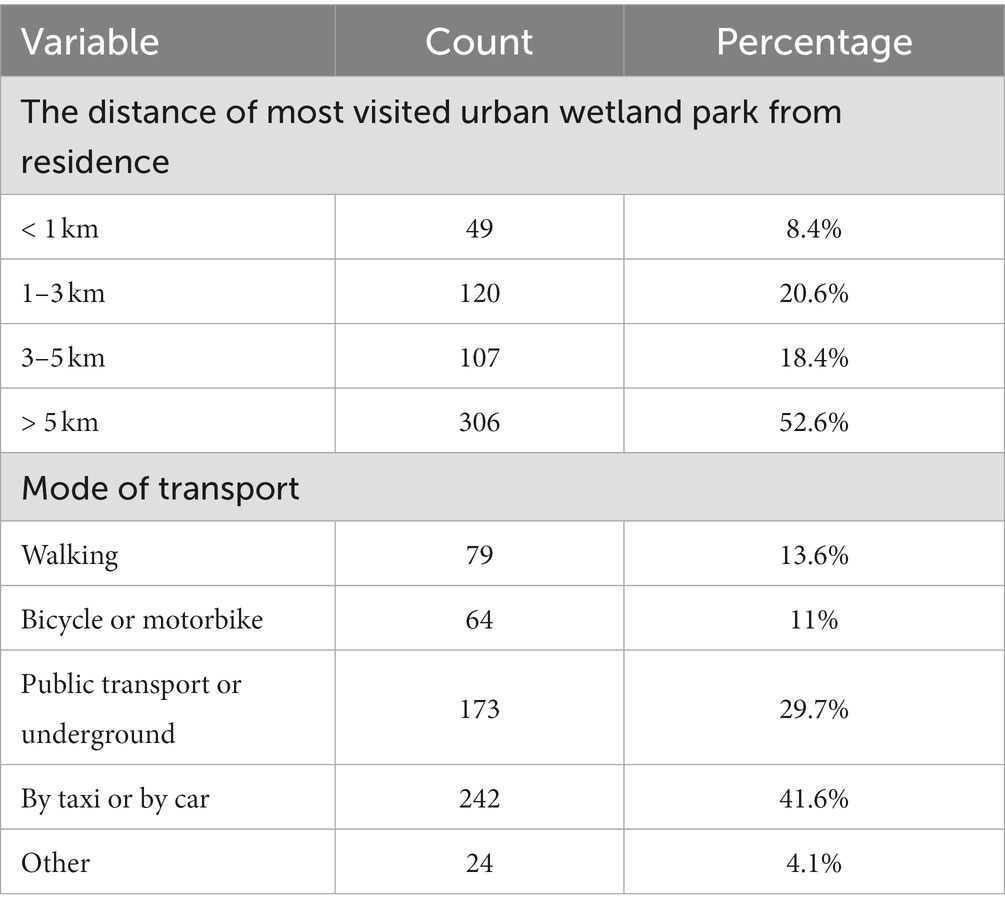

Table 2 presents the socio-demographic characteristics, socio-economic status, and dwelling conditions of the respondents. Slightly more female visitors than male visitors participated in the survey. Of the respondents, 18–45-year-olds were the majority, followed by those aged 45 years. In terms of marriage, 63.1% of the visitors were unmarried, and 36.9% were married. Approximately 76.1% of the respondents had a bachelor’s degree. Students were predominant in the sample population, accounting for 34.9% of respondents, while employed individuals accounted for 34.2%. The respondents’ monthly income is denoted in Chinese Yuan (CNY), and the income of more than one-third of the respondents did not exceed 3,000 CNY. Regarding housing tenure status, most respondents lived in dormitories or with their families, and approximately 70% of respondents did not own property. Most of the respondents had lived in the local area for more than 3 years. Nearly half of the respondents reported that their neighborhoods were under semi-containment or full containment as a result of the outbreak. Of these, 13.1% were strictly confined to their homes during the outbreak and could not move freely within their neighborhoods. In addition, 44% of them were required to record their temperature when entering and leaving the neighborhood.

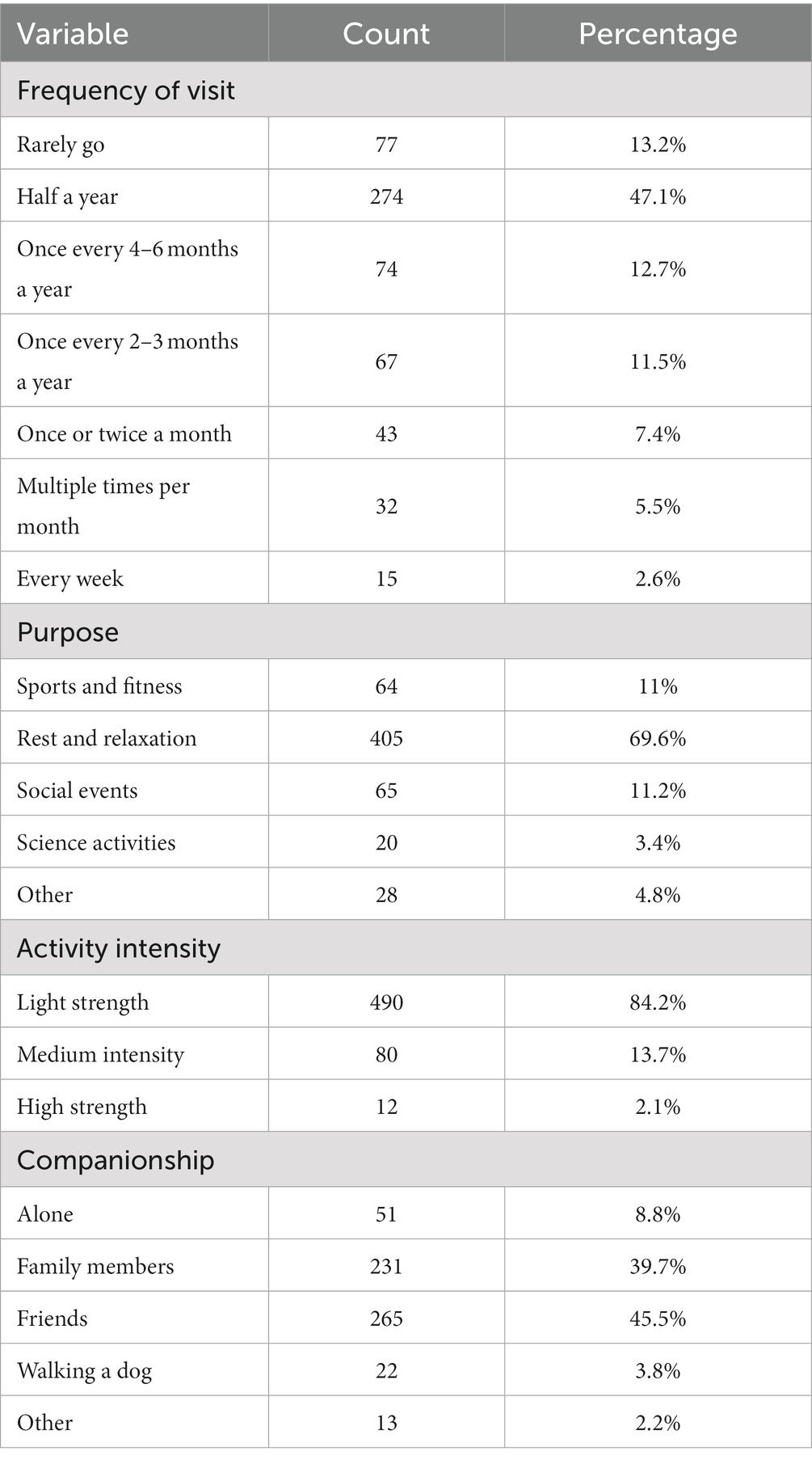

Table 3 lists the factors related to transportation. More than half of the visitors traveled more than 5 km to the wetland park, and only 8.4% traveled less than 1 km; thus, the wetland park attracts many visitors who live far from it. In terms of transport choice, 41.6% of visitors chose to travel by taxi or car, with the fewest visitors choosing to travel by motorbike or bicycle, accounting for 11% of the sample size. The respondents who visited wetland parks once every 6 months accounted for 47.1% of the sample size, and only 2.6% visited wetland parks weekly. For most of them, the main purpose of visiting was to rest and relax. In terms of activity intensity, 84.2% of visitors chose low-intensity activities, whereas only 2.1% engaged in high-intensity activities. Regarding the form of accompaniment on a visit to a wetland park, 45.5% of visitors indicated that they usually visited a wetland park with friends, followed by family members, accounting for 39.7% of the sample size (Table 4).

4.2. Identifying distinct classes of health perception

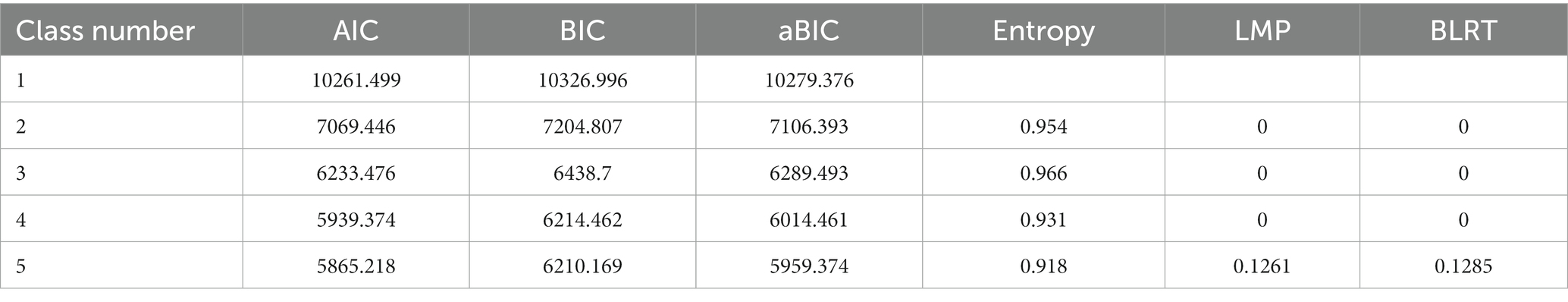

Models with increments in the number of classes were estimated to detect a suitable number of latent classes. Multiple statistical indicators were used to determine the best-fit model. The smaller the values of the Akaike information criterion (AIC), Bayesian information criterion (BIC), and adjusted Bayesian information criterion (aBIC), the better the model’s fit (47, 57). Entropy evaluates the accuracy of the model classification, and a value closer to 1 indicates a better fit (58). The Lo–Mendell–Rubin (LMR) and bootstrapped likelihood ratio test (BLRT) provide a value of p that can be used to compare the increase in model fit between neighboring class models and to determine a statistically significant improvement in fit when another class is included. As shown in Table 5, the AIC, BIC, and aBIC decreased as the number of categories increased. It is possible that the higher the number of categories, the better the fit. However, from Class 3, the entropy started to decrease, and from Class 4, the LMR (P) also started to become statistically insignificant (p > 0.05), indicating that the model’s fit gradually deteriorated from Class 3. The entropy was closest to 1 in Class 3, which means that the model has the best-fit and classification accuracy. A model with three latent classes was selected as the most appropriate for this study, considering the practical significance of the classes and the fit values p represented by the classes.

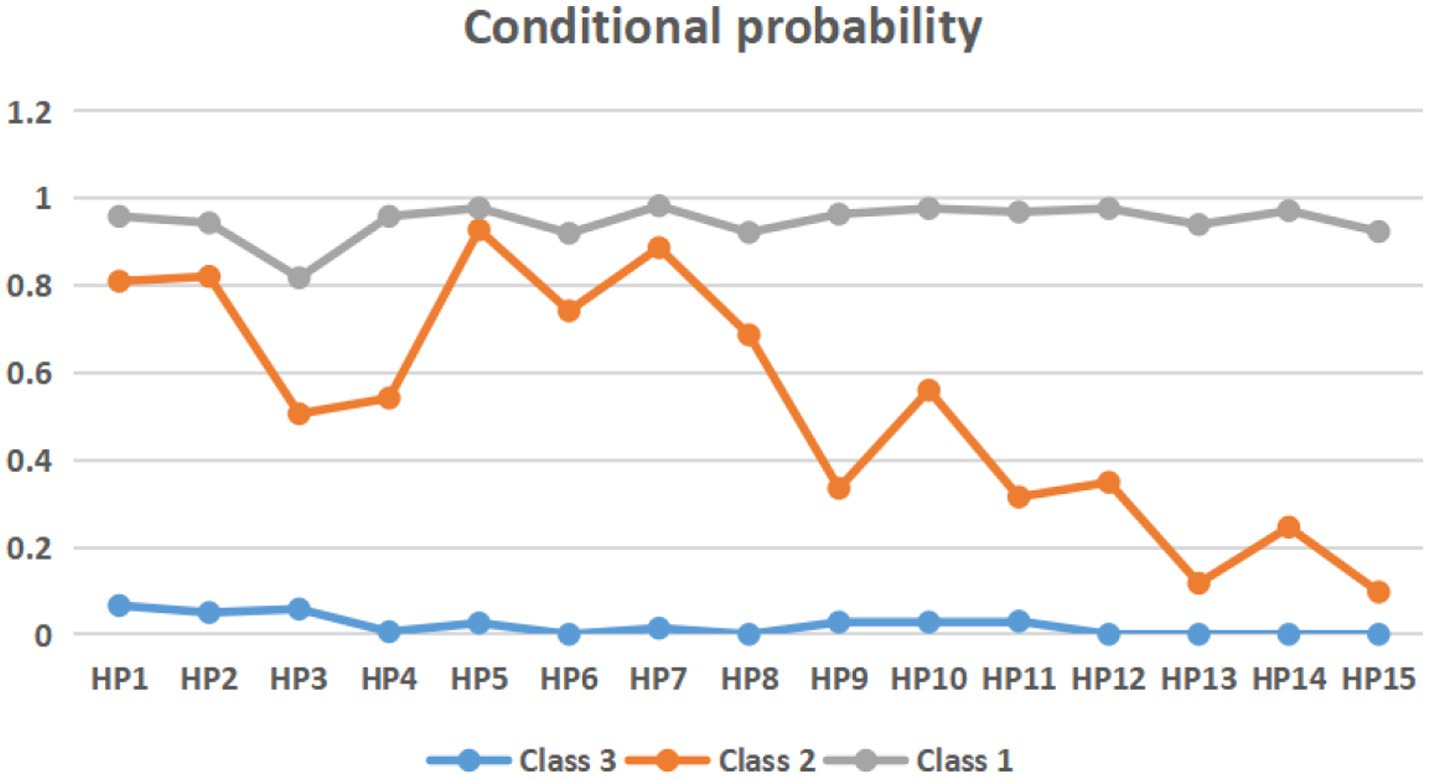

Based on the three-class model, Figure 2 illustrates the probabilities of respondents’ health perception in each latent class. Latent class 1 (C1) was characterized by high probabilities for all health perception components and labeled ‘good self-perception of health’ (n = 323, 55.5%). Latent class 2 (C2) was characterized by high probabilities of good health status in the present and future but did not improve significantly after the visit to the wetland park and was, therefore, named ‘neutral self-perception of health’ (n = 192, 33.0%). Latent class 3 (C3) was characterized by low probabilities of all health perceptions; accordingly, we labeled it ‘poor self-perception of health’ (n = 67, 11.5%).

4.3. Roles of different factors in predicting class membership

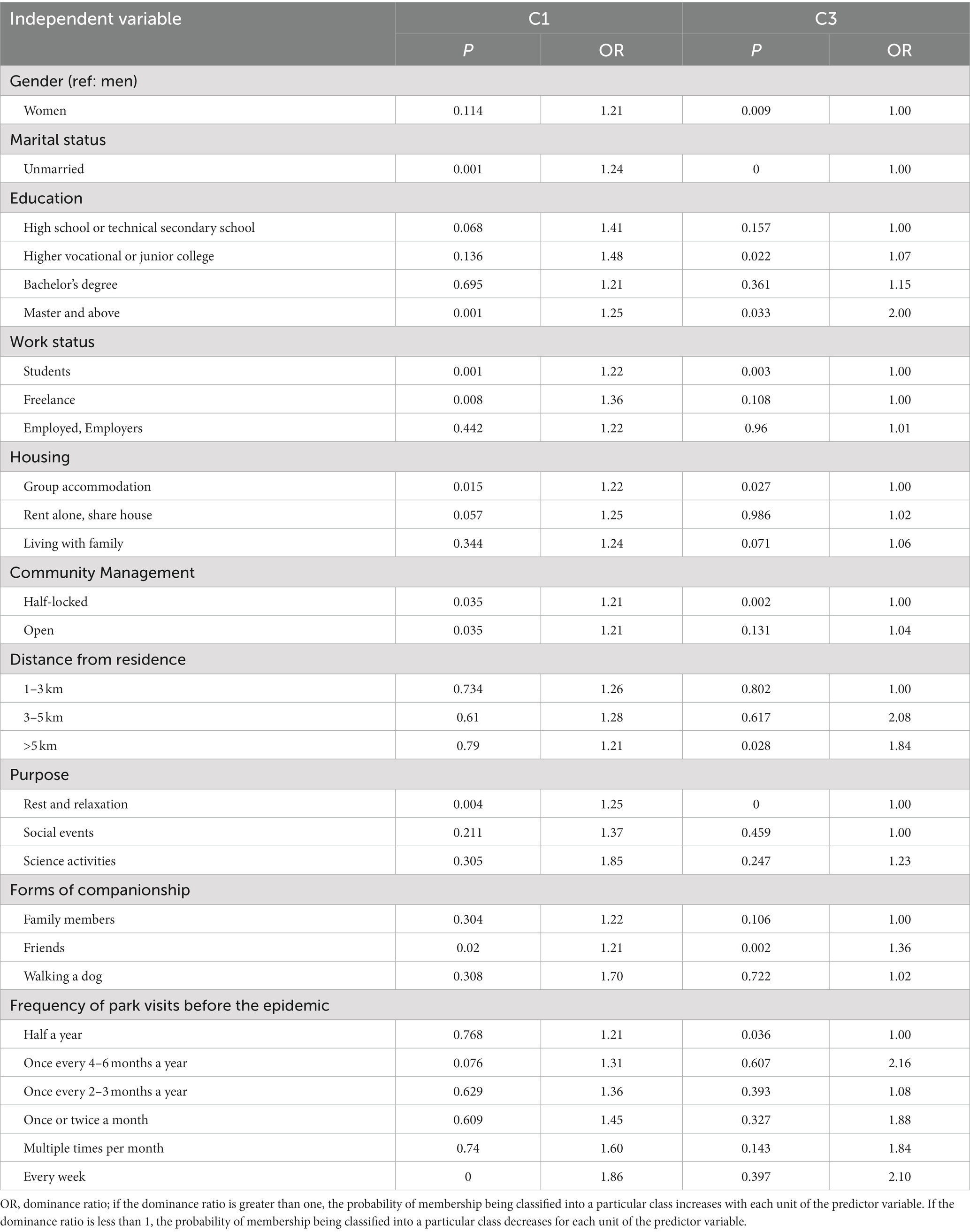

We further conducted a multinomial logistic regression model to examine the respondents’ health perceptions associated with their social backgrounds and behavioral activities, with Class 2 (medium self-perception of health) as the reference group (Table 6).

Compared with Class 2, respondents in Class 1 (good self-perception of health) were more likely to be unmarried (OR = 1.24, p < 0.001), master and above (OR = 1.25, p < 0.001), students or freelancers (OR = 1.22, p < 0.001; OR = 1.36, p < 0.01), in a group accommodation (OR = 1.22, p < 0.05) and under open and semi-closure management of residential areas during the outbreak period (OR = 1.21, p < 0.05; OR = 1.21, p < 0.05). The main purposes for visiting the park were more likely to be for rest and relaxation (OR = 1.25, p < 0.01). The probabilities of visiting the park with friends were high, and weekly park visits before the outbreak were high (OR = 1.21, p < 0.05; OR = 1.86, p < 0.001).

Compared with Class 2, respondents in Class 3 (poor self-perception of health) were more likely to be female (OR = 1, p < 0.05), unmarried (OR = 1, p < 0.001), with a higher vocational or junior college degree (OR = 1.07, p < 0.05), with a master’s degree and above (OR = 2, p < 0.05), students (OR = 1, p < 0.05), in a group accommodation (OR = 1, p < 0.05), and under semi-closure management of residential areas during the outbreak period (OR = 1, p < 0.01). Accommodation was more than 5 km away from the wetland park (OR = 1.84, p < 0.05). The main purposes of visiting the park were more likely to be for rest and relaxation (OR = 1, p < 0.001). The probabilities of visiting the park with friends and visiting the park 6 months before the outbreak (OR = 1.36, p < 0.05; OR = 1, p < 0.05).

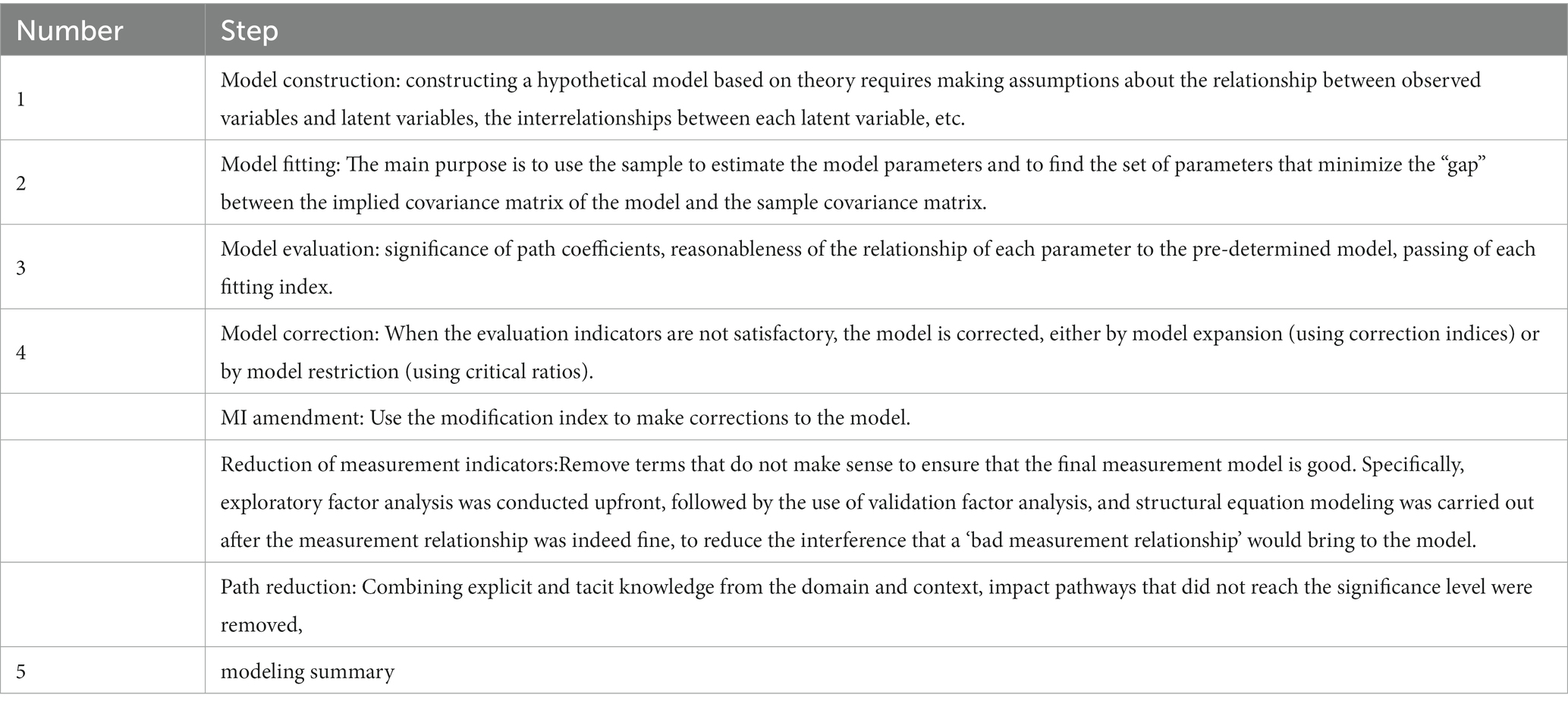

4.4. Structural equation modeling results

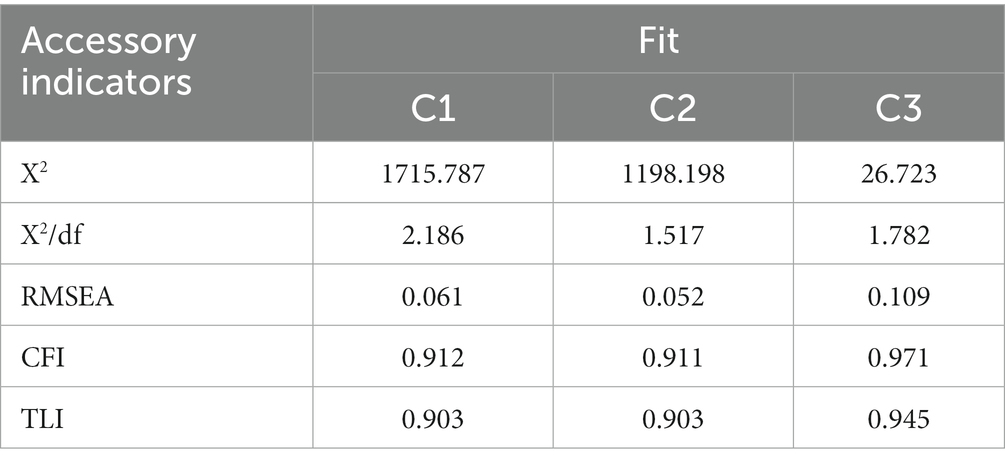

Table 7 shows that the critical fitting indices of C1 and C2 are within the acceptable recommended value range; thus, models C1 and C2 have good fitting degrees. The CFI and TLI of C3 are within the acceptable recommended value range, respectively; however, the RMSEA of C3 suggests an insufficient model fit. Overall, the model’s fit was considered acceptable, as RMSEA can suggest a below-adequate model fit for models with low degrees of freedom (59). The relevant structural equation modeling adjustments are detailed in Appendix A.

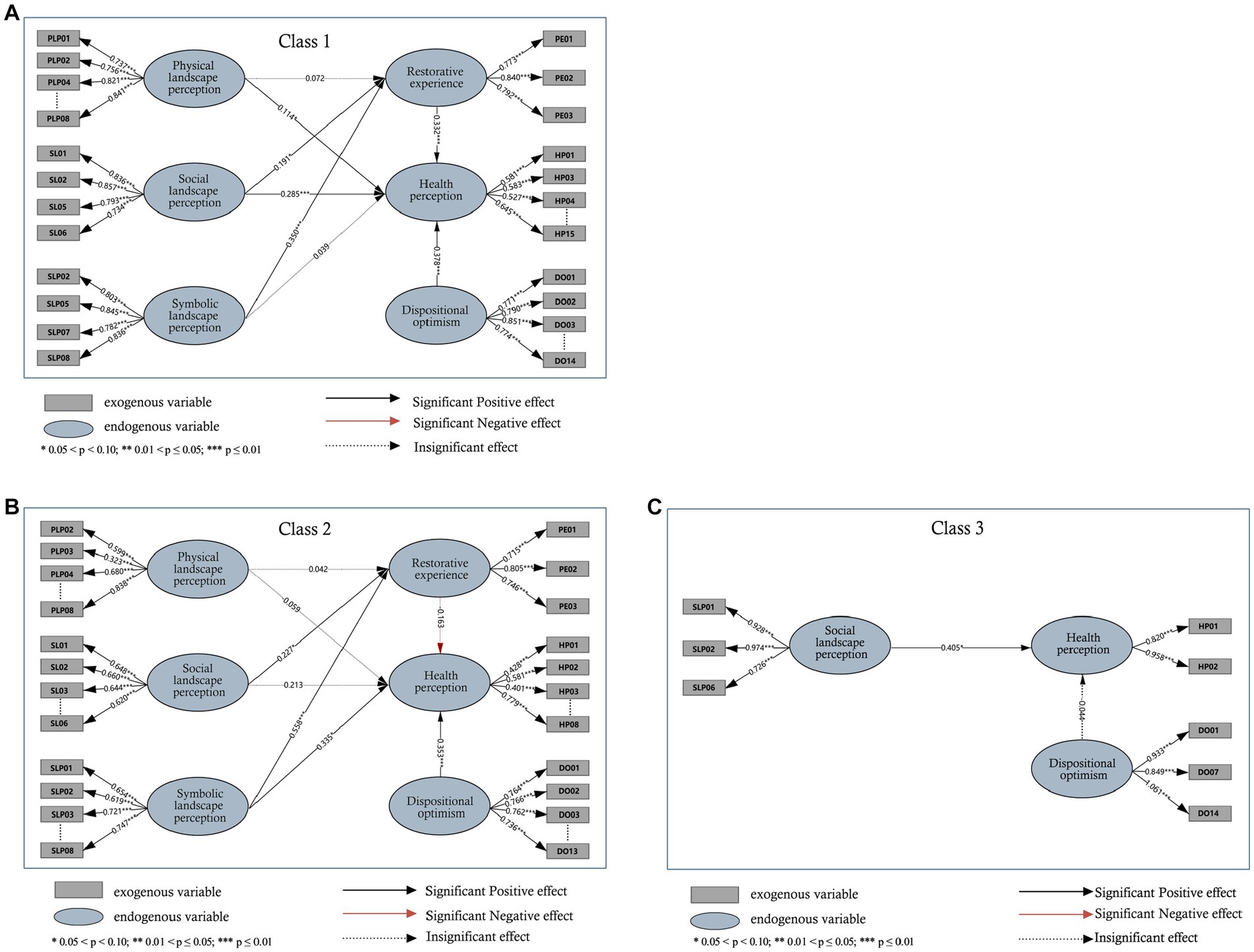

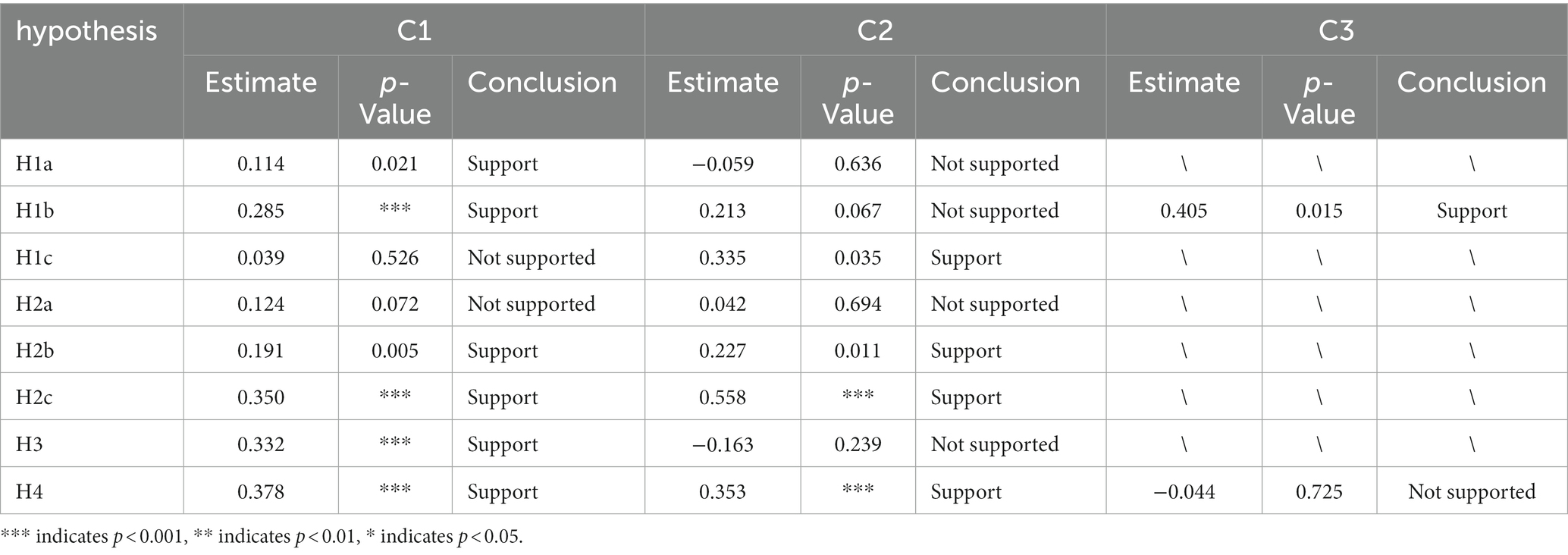

The research model’s hypothesis was validated using AMOS 24.0, and the standardized path coefficients and significance levels between the latent variables are shown in Figure 3. The final hypothesis validation results are shown in Figure 3.

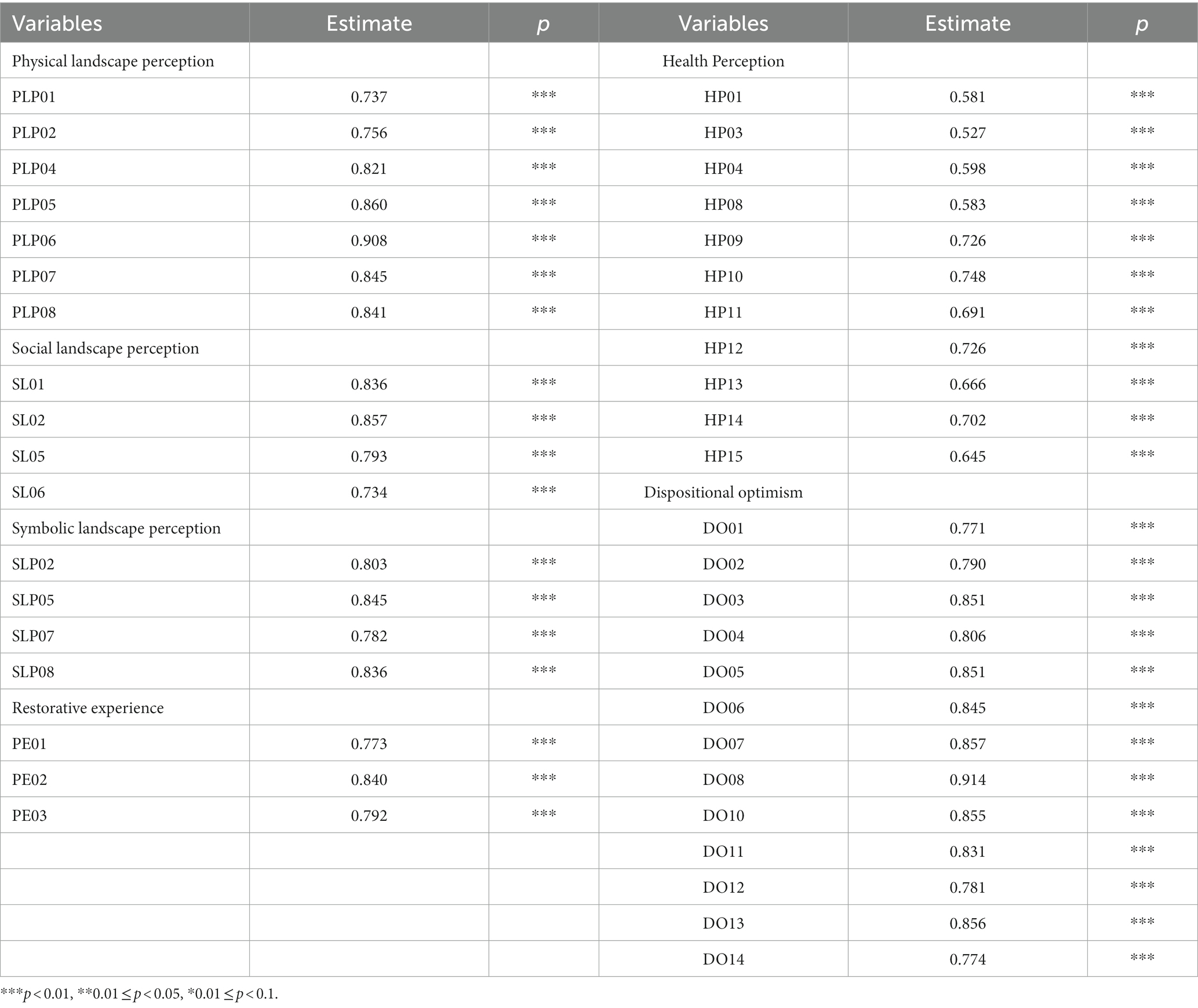

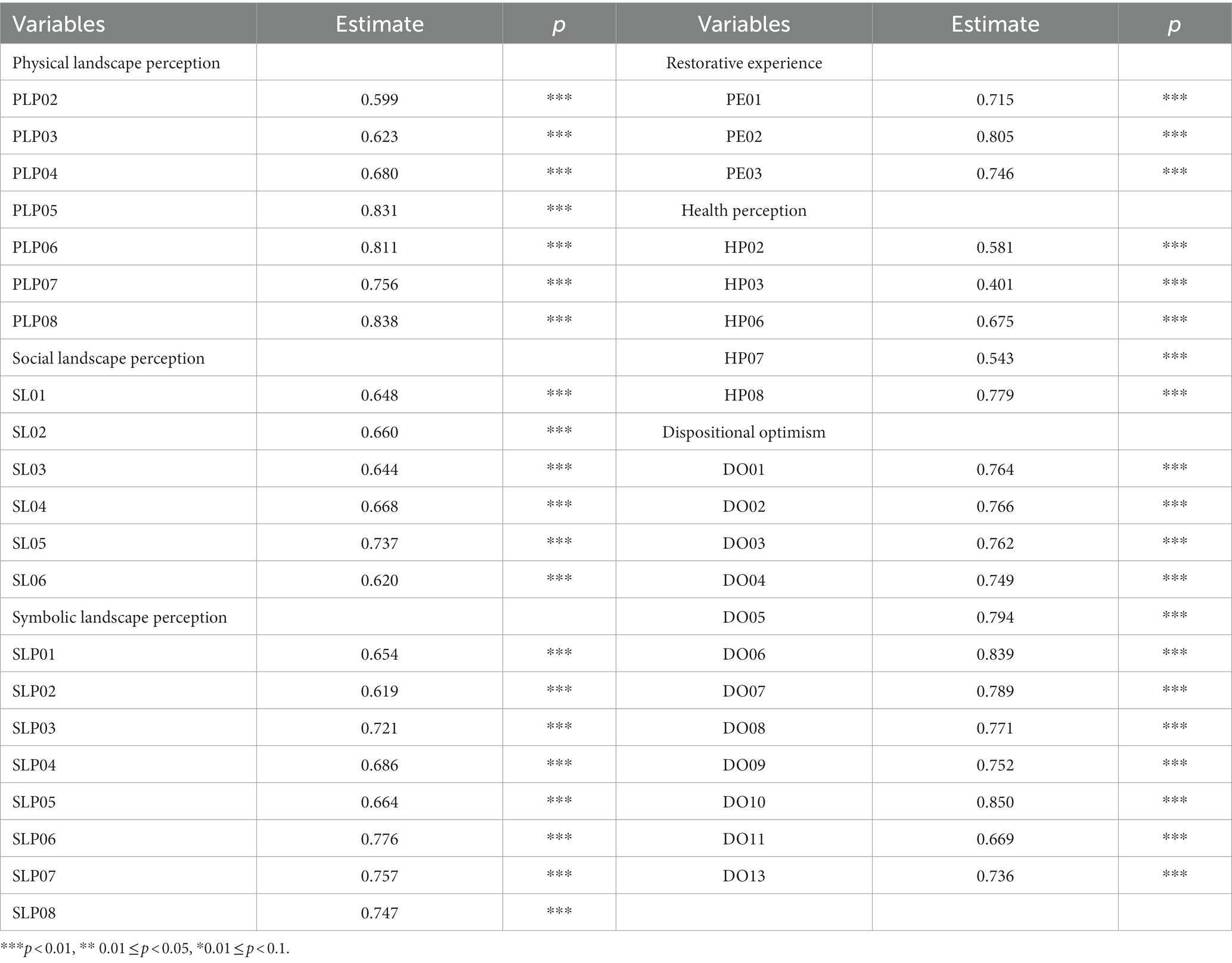

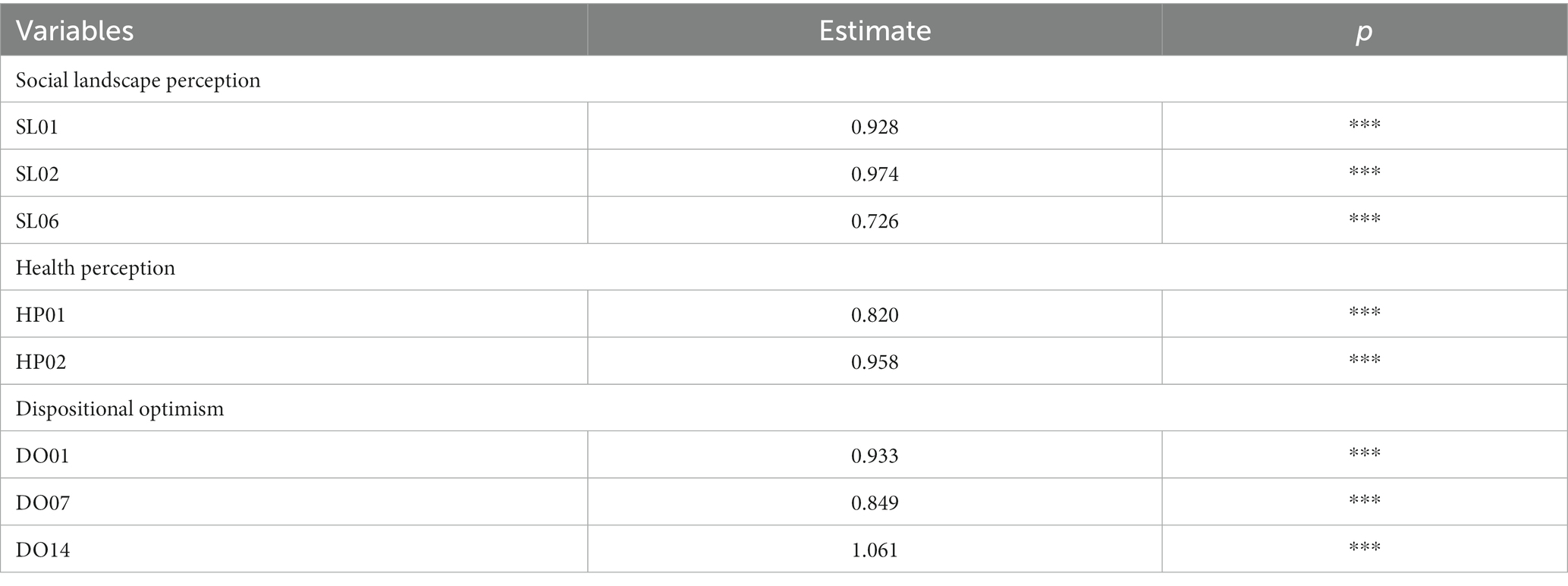

As shown in Tables 8–10, the standardized factor loadings between the latent variables and all the corresponding observed variables are >0.5. Regarding the structural models, Table 11 presents the estimation results for the three latent classes; those for latent class 1 are as follows (Figure 3A). Visitor’s physical landscape perception (γ = 0.114, p = 0.021) and social landscape perception (γ = 0.285, p <0.001) were positively significant on health perception. Visitors’ perceptions of the social landscape (γ = 0.191, p = 0.005) and symbolic landscape (γ = 0.350, p < 0.001) were positively significant for their restorative experiences. The effect of visitors’ restorative experience (γ = 0.332, p<0.001) and character optimism (γ = 0.378, p<0.001) on health perceptions was positively significant. The relationship between the visitors’ symbolic landscape perception variables (γ = 0.039, p = 0.526) and health perceptions was not significant.

The results in C2 were as described below (Figure 3B). In terms of perceived landscape, perceived symbolic landscape (γ = 0.335, p = 0.035) had a positive and significant effect on health perception. Restorative experiences (γ = −0.163, p = 0.239) and health perceptions were not significantly related to each other. Dispositional optimism (γ = 0.353, p<0.001) significantly and positively influenced health perceptions. In terms of restorative experience, the perceived physical landscape (γ = 0.042, p = 0.694) was not significantly related to restorative experience. Perceived social landscape (γ = 0.227, p = 0.0.011) and symbolic landscape (γ = 0.558, p < 0.001) significantly influenced restorative experience.

For latent class 3 (Figure 3C), social landscape perception (γ = 0.405, p = 0.015) influenced health perception, while dispositional optimism (γ = −0.044, p = 0.725) had no significant relationship with health perception.

5. Discussion

We investigated the impact of restorative landscapes in wetland parks on the health perceptions of respondents during the COVID-19 pandemic. By classifying respondents’ health perceptions into latent classes, we found that visitors could be classified into three groups with significant group heterogeneity in the population. Sociodemographic characteristics and behavioral factors showed different associations with each group.

Compared with the ‘medium self-perception of health’ class, respondents in the ‘good self-perception of health’ group were more likely to be freelancers and have a higher education level. Consistent with previous studies, freelancers have more time at their disposal and fewer stressors than other professionals, and participating in leisure and recreational activities can reduce psychological stress and improve their physical and mental wellbeing. With the improvement in education level, highly educated people have a relatively high preference for wild nature and a strong restorative experience in wetland parks (23). Our results also showed that residents of unsealed neighborhoods had a higher probability of belonging to the ‘good self-perception of health’ category during the peak of the epidemic. Lockdown measures have been a panacea for pandemic control. However, home restrictions and the overall disruption of personal daily life have made people exercise less; the workspace in a home office environment has increased the chances of physical pain and other physical health conditions, and blurred work–life boundaries can make it difficult to detach mentally from work, which can increase stress and anxiety. Therefore, when dealing with major safety and health events such as the epidemic, the community and the wetland park should adopt a ‘closed’ and ‘open’ relationship (12, 60–64). The frequency and intensity of park cleaning and disinfection can be increased within the park, and infrastructure to stimulate exercise can be incorporated. The maximum number of visitors to a park during an outbreak can also be predicted, and spaces with a large distribution of visitors can be monitored for flow and effective evacuation guidance. Outside the parks, it is necessary to increase connections with residents in neighboring communities and improve residents’ accessibility to parks (65).

Compared to the ‘medium self-perception of health’ group, the ‘poor self-perception of health’ group was more likely to include women. Consistent with previous studies, gender strongly shapes the experience of visitors to urban parks, with men being more likely than women to rate health benefits when visiting urban blue-green spaces at peak times. In addition, the more frequently residents visit parks, the better their perceived health status, which indicates that park users develop place attachment and increased affinity with nature, which contribute to health benefits. The more residents lived in a wetland park, the worse their perceived health. This is because, at the peak of the epidemic, many non-essential commercial and public spaces were off-limits. People’s need to visit outdoor spaces was higher than ever. Thus, the closer the urban wetland park was to the neighbourhood, the more people had access to the park, and the more likely they felt healthy. Therefore, it is possible to extend the opening hours of wetland park services during epidemics and improve accessibility to parks while observing more accurate infection prevention methods to ensure wetland park use (65, 66).

The SEM results of the three categories showed that landscape perception, optimistic personality tendencies, and restorative experiences had different strengths and associations with health perception. It is worth noting that in the first category, the symbolic landscape has no positive effect on health perception and restorative experience, possibly because the environmental elements and cultural cues associated with symbolic restorative health in China’s wetland parks have not yet established positive images for people. Fewer psychological hints about health are available to visitors compared to those available at famous sites known for longevity and healing. Therefore, in future construction of wetland parks, planning designers can try to add cultural clues and symbols with symbolic significance for health and create environmental factors conducive to the healthy restoration of wetland parks. Additionally, the results showed that optimism had an impact on health perceptions regardless of group, and optimists’ positive expectations are not limited to specific areas of behavior or types of circumstances.

6. Conclusion

This study examined the impact of wetland park landscapes on different health-perceiving populations during the COVID-19 pandemic. The study identified various factors affecting the potential categories of health perception of visitors, such as gender, marital status, education, work status, housing, community management, distance from home, purpose, form of companionship, and frequency of pre-pandemic park visits. The existence of different pathways and correspondence coefficients among the three potential categories of visitor groups was also investigated. In the event of a future major safety and health event, wetland park managers should pre-emptively address the need for ‘closed’ and ‘open’ relationships between communities and wetland parks and try to increase cultural cues and symbols with health symbolism. However, this study had several limitations. First, the findings were limited to Chinese participants. Future studies should explore cross-cultural comparisons among visitors from different countries. Second, this study did not examine the dynamics of health perceptions over time. Future research could examine longitudinal changes in the health perceptions of wetland parks. These insights can inform the decision-making process and contribute to better planning and management of wetland parks.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the participants was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

JL: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft. YC: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology. XC: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Resources, Writing – review & editing. SL: Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. YP: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. TF: Writing – review & editing. JQ: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft. YJ: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft. YX: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft. WL: Resources, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The authors declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 52108049, 42177072, and 51909283), the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province, China (Nos. 2020JJ4711 and 2023JJ30182), the Humanities and Social Science Fund of Ministry of Education of China (No. 20YJCZH003), the Key Research and Development program of Hunan Province in China (No. 2020WK2001), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of Central South University (No. 2021XQLH116).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Chinazzi, M, Davis Jessica, T, Ajelli, M, Gioannini, C, Litvinova, M, Merler, S, et al. The effect of travel restrictions on the spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus (Covid-19) outbreak. Science. (2020) 368:395–400. doi: 10.1126/science.aba9757

2. Losada-Baltar, A, Jiménez-Gonzalo, L, Gallego-Alberto, L, Pedroso-Chaparro, MS, Fernandes-Pires, J, and Márquez-González, M. “We are staying at home”. Association of Self-perceptions of aging, personal and family resources, and loneliness With psychological distress during the lock-down period of COVID-19. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. (2021) 76:e10–6. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbaa048

3. Xiao, Y, Becerik-Gerber, B, Lucas, G, and Roll, SC. Impacts of working from home during Covid-19 pandemic on physical and mental well-being of office workstation users. J Occup Environ Med. (2021) 63:181–90. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000002097

4. Huang, R, and Wang, X. Impact of Covid-19 on mental health in China: analysis based on sentiment knowledge enhanced pre-training and Xgboost algorithm. Front Public Health. (2023) 11:11. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1170838

5. Zhang, S, Liu, Q, Yang, F, Zhang, J, Fu, Y, Zhu, Z, et al. Associations between Covid-19 infection experiences and mental health problems among Chinese adults: a large cross-section study. J Affect Disord. (2023) 340:719–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2023.08.080

6. Felt, JM, Russell, MA, Johnson, JA, Ruiz, JM, Uchino, BN, Allison, M, et al. Within-person associations of optimistic and pessimistic expectations with momentary stress, affect, and ambulatory blood pressure. Anxiety Stress Coping. (2023) 36:636–48. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2022.2142574

7. Oh, J, Purol, MF, Weidmann, R, Chopik, WJ, Kim, ES, Baranski, E, et al. Health and well-being consequences of optimism across 25 years in the Rochester adult longitudinal study. J Res Pers. (2022) 99:104237. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2022.104237

8. Sonti, NF, Campbell, LK, Svendsen, ES, Johnson, ML, and Novem Auyeung, DS. Fear and fascination: use and perceptions of new York City’s forests, wetlands, and Landscaped Park areas. Urban For Urban Green. (2020) 49:126601. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2020.126601

9. Barbier, EB. The value of coastal wetland ecosystem services In: GME Perillo, E Wolanski, DR Cahoon, and CS Hopkinson, editors. Coastal wetlands. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier (2019). 947–64.

11. Erika, SS, Lindsay, KC, and Heather, LM. Stories, shrines, and symbols: recognizing psycho-social-spiritual benefits of urban parks and natural areas. J Ethnobiol. (2016) 36:881–907. doi: 10.2993/0278-0771-36.4.881

12. Barquilla, CAM, Lee, J, and He, SY. The impact of greenspace proximity on stress levels and travel behavior among residents in Pasig City, Philippines during the Covid-19 pandemic. Sustain Cities Soc. (2023) 97:104782. doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2023.104782

13. Wei, H, Zhang, J, Xu, Z, Hui, T, Guo, P, and Sun, Y. The association between plant diversity and perceived emotions for visitors in urban forests: a pilot study across 49 parks in China. Urban For Urban Green. (2022) 73:127613. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2022.127613

14. Luo, L, Yu, P, and Jiang, B. Differentiating mental health promotion effects of various Bluespaces: an electroencephalography study. J Environ Psychol. (2023) 88:102010. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2023.102010

15. Ha, J, Kim, HJ, and With, KA. Urban green space alone is not enough: a landscape analysis linking the spatial distribution of urban green space to mental health in the City of Chicago. Landsc Urban Plan. (2022) 218:104309. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2021.104309

16. Davidson, NC, and Finlayson, CM. Updating global coastal wetland areas presented in Davidson and Finlayson (2018). Mar Freshw Res. (2019) 70:1195–200. doi: 10.1071/MF19010

17. Zhou, LL, Guan, DJ, Huang, XY, Yuan, XZ, and Zhang, MJ. Evaluation of the cultural ecosystem Services of Wetland Park. Ecol Indic. (2020) 114:106286. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2020.106286

18. Gascon, M, Sánchez-Benavides, G, Dadvand, P, Martínez, D, Gramunt, N, Gotsens, X, et al. Long-term exposure to residential green and blue spaces and anxiety and depression in adults: a cross-sectional study. Environ Res. (2018) 162:231–9. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2018.01.012

19. Gesler, WM. Therapeutic landscapes: medical issues in light of the new cultural geography. Soc Sci Med. (1992) 34:735–46. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90360-3

20. Gesler, WM. Therapeutic landscapes: theory and a case study of Epidauros, Greece. Environ Plan D Soc Space. (1993) 11:171–89. doi: 10.1068/d110171

21. Kearns, R, and Milligan, C. Placing therapeutic landscape as theoretical development in Health & Place. Health Place. (2020) 61:102224. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.102224

22. Markevych, I, Schoierer, J, Hartig, T, Chudnovsky, A, Hystad, P, Dzhambov, AM, et al. Exploring pathways linking greenspace to health: theoretical and methodological guidance. Environ Res. (2017) 158:301–17. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2017.06.028

23. Ode Sang, Å, Knez, I, Gunnarsson, B, and Hedblom, M. The effects of naturalness, gender, and age on how urban green space is perceived and used. Urban For Urban Green. (2016) 18:268–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2016.06.008

24. Coles, RW, and Bussey, SC. Urban Forest landscapes in the UK–progressing the social agenda. Landsc Urban Plan. (2000) 52:181–8. doi: 10.1016/S0169-2046(00)00132-8

25. Carrus, G, Lafortezza, R, Colangelo, G, Dentamaro, I, Scopelliti, M, and Sanesi, G. Relations between naturalness and perceived Restorativeness of different urban green spaces. PsyEcology. (2013) 4:227–44. doi: 10.1174/217119713807749869

26. Zedler, JB, and Kercher, S. Wetland resources: status, trends, ecosystem services, and restorability. Annu Rev Environ Resour. (2005) 30:39–74. doi: 10.1146/annurev.energy.30.050504.144248

27. De Groot, JIM, and Steg, L. Value orientations to explain beliefs related to environmental significant behavior: how to measure egoistic, altruistic, and Biospheric value orientations. Environ Behav. (2007) 40:330–54. doi: 10.1177/0013916506297831

28. Pröbstl-Haider, U, Gugerell, K, and Maruthaveeran, S. Covid-19 and outdoor recreation – lessons learned? Introduction to the special issue on “outdoor recreation and Covid-19: its effects on people, parks and landscapes”. J Outdoor Recreat Tour. (2023) 41:100583. doi: 10.1016/j.jort.2022.100583

29. Kim, YJ, Cho, JH, and Park, YJ. Leisure sports Participants' engagement in preventive health behaviors and their experience of constraints on performing leisure activities during the Covid-19 pandemic. Front Psychol. (2020) 11:589708. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.589708

30. Ryan, RL. The social landscape of planning: integrating social and perceptual research with spatial planning information. Landsc Urban Plan. (2011) 100:361–3. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2011.01.015

31. Wellman, B, and Wortley, S. Different strokes from different folks: community ties and social support. Am J Sociol. (1990) 96:558–88. doi: 10.1086/229572

32. Milligan, C, Gatrell, A, and Bingley, A. ‘Cultivating health’: therapeutic landscapes and older people in northern England. Soc Sci Med. (2004) 58:1781–93. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00397-6

33. Sonntag-Öström, E, Nordin, M, Lundell, Y, Dolling, A, Wiklund, U, Karlsson, M, et al. Restorative effects of visits to urban and Forest environments in patients with exhaustion disorder. Urban For Urban Green. (2014) 13:344–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2013.12.007

34. Adevi, AA, and Mårtensson, F. Stress rehabilitation through garden therapy: the garden as a place in the recovery from stress. Urban For Urban Green. (2013) 12:230–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2013.01.007

35. Jo, H, Rodiek, S, Fujii, E, Miyazaki, Y, Park, B-J, and Ann, S-W. Physiological and psychological response to floral scent. HortScience Horts. (2013) 48:82–8. doi: 10.21273/HORTSCI.48.1.82

36. Valladares, A, Bornstein, L, Botero, N, Gold, I, Sayanvala, F, and Weinstock, D. From scary places to therapeutic landscapes: voices from the Community of People Living with schizophrenia. Health Place. (2022) 78:102903. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2022.102903

37. Ross-Bryant, L. Sacred sites: nature and nation in the U.S. National Parks. Relig Am Cult. (2005) 15:31–62. doi: 10.1525/rac.2005.15.1.31

38. Li, J, Pan, Q, Peng, Y, Feng, T, Liu, SB, Cai, XX, et al. Perceived quality of urban wetland parks: a second-order factor structure equation modeling. Sustainability. (2020) 12:204. doi: 10.3390/su12177204

39. Zhai, X, and Lange, E. The influence of Covid-19 on perceived health effects of wetland parks in China. Wetlands. (2021) 41:101. doi: 10.1007/s13157-021-01505-7

40. Kovary, M. Healing landscapes: Design guidelines for mental health facilities. Ames, Iowa: Iowa State University Press (2002).

41. Jorgensen, A, Hitchmough, J, and Calvert, T. Woodland spaces and edges: their impact on perception of safety and preference. Landsc Urban Plan. (2002) 60:135–50. doi: 10.1016/S0169-2046(02)00052-X

42. Liu, L, Zhong, Y, Ao, S, and Wu, H. Exploring the relevance of green space and epidemic diseases based on panel data in China from 2007 to 2016. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:2551. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16142551

43. Crouse Dan, L, Balram, A, Hystad, P, Pinault, L, van den Bosch, M, Chen, H, et al. Associations between living near water and risk of mortality among urban Canadians. Environ Health Perspect. 126:077008. doi: 10.1289/EHP3397

44. Avvenuti, G, Baiardini, I, and Giardini, A. Optimism’s explicative role for chronic diseases. Front Psychol. (2016) 7:7. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00295

45. Arni, P, Dragone, D, Goette, L, and Ziebarth, NR. Biased health perceptions and risky health behaviors—theory and evidence. J Health Econ. (2021) 76:102425. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2021.102425

46. Mazumdar, S, and Gerdtham, U-G. Heterogeneity in self-assessed health status among the elderly in India. Asia Pac J Public Health. (2013) 25:271–83. doi: 10.1177/1010539511416109

47. Peng, Y, Feng, T, and Timmermans, HJP. Heterogeneity in outdoor comfort assessment in urban public spaces. Sci Total Environ. (2021) 790:147941. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.147941

48. Lemieux, CJ, Eagles, PFJ, Slocombe, DS, Doherty, ST, Elliott, SJ, and Mock, SE. Human health and well-being motivations and benefits associated with protected area experiences: an opportunity for transforming policy and Management in Canada. Parks. (2012) 18:71–85. doi: 10.2305/IUCN.CH.2012.PARKS-18-1.CJL.en

49. Aflaki, K, Vigod, S, and Ray, JG. Part I: a friendly introduction to latent class analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. (2022) 147:168–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2022.05.008

50. Muthén, B, and Muthén, LK. Integrating person-centered and variable-centered analyses: growth mixture modeling with latent trajectory classes. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. (2000) 24:882–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2000.tb02070.x

51. Sevenant, M, and Antrop, M. The use of latent classes to identify individual differences in the importance of landscape dimensions for aesthetic preference. Land Use Policy. (2010) 27:827–42. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2009.11.002

52. Tarka, P. An overview of structural equation modeling: its beginnings, historical development, usefulness and controversies in the social sciences. Qual Quant. (2018) 52:313–54. doi: 10.1007/s11135-017-0469-8

54. Korpela, KM, Hartig, T, Kaiser, FG, and Fuhrer, U. Restorative experience and self-regulation in favorite places. Environ Behav. (2001) 33:572–89. doi: 10.1177/00139160121973133

55. Korpela, KM, Ylén, M, Tyrväinen, L, and Silvennoinen, H. Determinants of restorative experiences in everyday favorite places. Health Place. (2008) 14:636–52. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2007.10.008

56. von Lindern, E. Setting-dependent constraints on human restoration while visiting a wilderness Park. J Outdoor Recreat Tour. (2015) 10:29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jort.2015.06.001

57. Berlin, KS, Williams, NA, and Parra, GR. An introduction to latent variable mixture modeling (part 1): overview and cross-sectional latent class and latent profile analyses. J Pediatr Psychol. (2014) 39:174–87. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jst084

58. Celeux, G, and Soromenho, G. An entropy criterion for assessing the number of clusters in a mixture model. J Classif. (1996) 13:195–212. doi: 10.1007/BF01246098

59. Kenny, DA, Kaniskan, B, and McCoach, DB. The performance of Rmsea in models with small degrees of freedom. Sociol Methods Res. (2014) 44:486–507. doi: 10.1177/0049124114543236

60. Venter, ZS, Barton, DN, Gundersen, V, Figari, H, and Nowell, MS. Back to nature: Norwegians sustain increased recreational use of urban green space months after the Covid-19 outbreak. Landsc Urban Plan. (2021) 214:104175. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2021.104175

61. Gao, S, Zhai, W, and Fu, X. Green space justice amid Covid-19: unequal access to public green space across American neighborhoods. Front Public Health. (2023) 11:11. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1055720

62. Zhang, W, and Li, J. A quasi-experimental analysis on the causal effects of Covid-19 on Urban Park visits: the role of Park features and the surrounding built environment. Urban For Urban Green. (2023) 82:127898. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2023.127898

63. Rice, WL, and Pan, B. Understanding changes in Park visitation during the Covid-19 pandemic: a spatial application of big data. Wellbeing Space Soc. (2021) 2:100037. doi: 10.1016/j.wss.2021.100037

64. Geneletti, D, Cortinovis, C, and Zardo, L. Simulating crowding of urban green areas to manage access during lockdowns. Landsc Urban Plan. (2022) 219:104319. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2021.104319

65. Wu, Y, Wei, YD, Liu, M, and García, I. Green infrastructure inequality in the context of Covid-19: taking parks and trails as examples. Urban For Urban Green. (2023) 86:128027. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2023.128027

66. Padeiro, M, Freitas, Â, Costa, C, Loureiro, A, and Santana, P. Resilient cities and built environment: Urban Design, citizens and health. Learning from Covid-19 experiences In: E Pozo Menéndez and E Higueras García, editors. Urban design and planning for age-friendly environments across Europe: North and south: Developing healthy and therapeutic living spaces for local contexts. Cham: Springer International Publishing (2022). 141–58.

Appendix A

Keywords: health perception, restorative experience, therapeutic landscape, COVID-19 pandemic, latent class analysis, structural equation modeling

Citation: Li J, Chang Y, Cai X, Liu S, Peng Y, Feng T, Qi J, Ji Y, Xia Y and Lai W (2023) Health perception and restorative experience in the therapeutic landscape of urban wetland parks during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Public Health. 11:1272347. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1272347

Edited by:

Shazia Rehman, Central South University, ChinaReviewed by:

Thomas Bias, West Virginia University, United StatesDaixin Dai, Tongji University, China

Copyright © 2023 Li, Chang, Cai, Liu, Peng, Feng, Qi, Ji, Xia and Lai. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiaoxi Cai, eGlhb3hpQGhudS5lZHUuY24=; Shaobo Liu, bGl1c2hhb2JvQGNzdS5lZHUuY24=

Jiang Li

Jiang Li Yating Chang1

Yating Chang1 Xiaoxi Cai

Xiaoxi Cai Shaobo Liu

Shaobo Liu You Peng

You Peng Yifeng Ji

Yifeng Ji