- 1Department of Public Health Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Sungai Buloh, Selangor, Malaysia

- 2Centre of Occupational Safety, Health and Wellbeing, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Puncak Alam, Selangor, Malaysia

- 3Department of Parasitology, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

- 4Department of Microbiology and Parasitology, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Aden, Aden, Yemen

- 5Department of Microbiology, International Medical School (IMS), Management & Science University (MSU), Shah Alam, Selangor, Malaysia

- 6Department of Parasitology and Medical Entomology, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Jalan Yaacob Latif, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

- 7Physiology Department, Human Biology Division, School of Medicine, International Medical University (IMU), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Background: There is limited evidence of financial toxicity (FT) among cancer patients from countries of various income levels. Hence, this study aimed to determine the prevalence of objective and subjective FT and their measurements in relation to cancer treatment.

Methods: PubMed, Science Direct, Scopus, and CINAHL databases were searched to find studies that examined FT. There was no limit on the design or setting of the study. Random-effects meta-analysis was utilized to obtain the pooled prevalence of objective FT.

Results: Out of 244 identified studies during the initial screening, only 64 studies were included in this review. The catastrophic health expenditure (CHE) method was often used in the included studies to determine the objective FT. The pooled prevalence of CHE was 47% (95% CI: 24.0–70.0) in middle- and high-income countries, and the highest percentage was noted in low-income countries (74.4%). A total of 30 studies focused on subjective FT, of which 9 used the Comprehensive Score for FT (COST) tool and reported median scores ranging between 17.0 and 31.9.

Conclusion: This study shows that cancer patients from various income-group countries experienced a significant financial burden during their treatment. It is imperative to conduct further studies on interventions and policies that can lower FT caused by cancer treatment.

1 Introduction

Cancer is the leading cause of death worldwide (1). Cancer cases and deaths continue to increase worldwide in both developed and developing countries. Despite the high cancer incidence rate in developed countries, the mortality rate is higher in developing countries (2, 3). Every year, approximately 400,000 youngsters are diagnosed with cancer (4). The growing number of people diagnosed with cancer places a responsibility on governments to offer services that are suitable, easily accessible, and reasonably priced. However, high-quality services for preventing, detecting, diagnosing, treating, supporting, and caring for those who have survived cancer are challenging to achieve due to multiple influential factors, including unstable politics, inadequately trained cancer care providers, and deficient coordination, in addition to the rising costs associated with cancer treatment (5).

A significant obstacle preventing many cancer patients from receiving therapy and care is the expense of doing so, given the significant geographical variations in patients’ financial capabilities and preparedness to spend money on healthcare and wellness services (6). In the vast majority of low-resourced countries, there is either very little or no universal access insurance coverage for medical care. However, even among insured patients, a significant number are not adequately protected against the expensive requirements of cancer treatment due to the elevated costs of insurance, which include higher co-payments and rising deductibles. Hence, cancer patients typically must pay a significant portion of their treatment costs out of pocket (7). The medical and non-medical expenses of cancer care, which result in a financial burden for cancer patients, are not adequately described in the existing body of research due to the absence of a nomenclature that is consistent throughout the field. Recent research has led to the development of a comprehensive definition of FT, which may be summarized as “The possible consequence of perceived subjective financial distress caused by an objective financial burden” (8). The terms “direct costs” and “indirect care-related costs” refer to “objective financial burden,” but “subjective financial hardship” refers to “material, psychosocial stress, negative feelings, and behavioral reactions to cancer care” (6, 8). FT is a term that is sometimes used interchangeably with terms such as financial or economic difficulties, financial difficulty, financial risk, and economic stress (9). Several studies provided valuable insights into the issue of FT among cancer patients and survivors. Yousuf Zafar (2016) highlighted that FT is a complex problem that affects the quality of life of cancer patients and survivors (10). Tucker-Seeley et al. (2016) build on this, indicating that socioeconomic factors contribute to FT, exacerbating health disparities (11). Arastu et al. (2020) highlighted that financial toxicity can be more prevalent among older adults, and they call for age-appropriate interventions (12). Gordon et al. (2016) found that cancer survivors face additional economic difficulties, such as out-of-pocket expenses and lost of income (13). Baddour et al. (2021) examined the objective and subjective impacts of financial toxicity on head and neck cancer survivors. They emphasize that financial distress not only affects the ability to pay for healthcare but also affects one’s mental health and wellbeing (14).

Ramsey et al. (2013) highlighted that cancer patients are at a greater risk of bankruptcy than individuals without cancer and that the problem of FT can persist beyond cancer diagnosis and treatment (15). Ramsey et al. (2016) further highlighted the connection between FT and early mortality among cancer patients, as financial distress may result in reduced adherence to medical treatments and a lower overall survival rate (16).

In summary, FT is a complex and significant issue for cancer patients and survivors, and its negative consequences can be long-lasting. The studies listed here provide evidence of the widespread occurrence of FT among cancer patients and survivors, indicating the need for policies and interventions to mitigate its effects and improve the quality of life for those affected.

Our study aimed to bridge the current gap in knowledge on FT among cancer patients across different countries with varying income levels. Although recent systematic reviews have examined FT in either low- or high-income countries (17, 18), there is limited comprehensive evidence that explores FT among cancer patients globally.

To address this gap, this systematic review and meta-analysis of existing literature aim to determine the prevalence and measurement of both objective and subjective FT among cancer patients. Our study utilized a rigorous methodology to identify and evaluate relevant studies from diverse sources and synthesize their findings. Through this approach, we aimed to provide a comprehensive understanding of the financial burden that cancer patients face and how it affects their lives.

The current study aims to contribute to the existing knowledge of FT among cancer patients, which will help improve clinical practice and healthcare policies worldwide. Our study will also provide a platform for future research in this area, as we anticipate identifying areas where more research is needed. Ultimately, our findings will assist in addressing the needs of cancer patients and survivors and support the development of effective interventions to mitigate the negative impacts of FT.

2 Methods

2.1 Search strategy

The systematic review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (19) guidelines from 15 August 2022 to 15 January 2023. The protocol was registered in Open Science (Registration DOI: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/MUNKG; Supplementary Table S1: PRISMA checklist).

PubMed, Science Direct, Scopus, and CINAHL databases were searched to find articles that reported FT. The search was built based on the research question concerning population/problem (cancer), outcome (financial toxicity), and exposure (healthcare treatment) and (cost of illness), as well as their synonyms (Supplementary File S1: search strategy). There was no limit on the publication year, design, or setting of the study, in order to minimize underreporting bias. In addition, a manual search through the reference list of eligible studies was applied. The search hits for databases are provided in the Supplementary File.

The primary outcome was to find the prevalence of subjective and objective FT among cancer patients. The cost of treatment was also considered a secondary outcome.

2.2 Study selection

First, the authors formed a search strategy involving all the relevant keywords based on their knowledge and literature. All search results were transferred to the Endnote X9 software. A total of 244 articles were identified through an online search and 24 articles through a manual search. Then, the duplicate articles were eliminated (20). The titles and abstracts of the remaining 185 articles were screened by two independent reviewers (MMA and VK). Subsequently, a total of 53 articles were retained for full-text review. Disagreements between the two reviewers were resolved by involving a third author (WMA). After a full-text review of the 53 articles, 40 were selected using the on-line search and 24 articles were selected using a manual search. The eligibility of the included articles was agreed upon by all authors. The PRISMA flowchart demonstrated the screening process (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flowchart of literature review search per Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA 2020) guidelines.

We included studies that are original English quantitative research articles and reported the financial toxicity (objective and subjective) of any type of cancer that were published before 28 August 2022. In addition, studies that reported any cost of cancer, including direct medical, direct non-medical, and indirect costs, were included. This study did not assess the intangible cost as it is difficult to calculate its monetary value. Economic evaluation studies, conference abstracts, reviews, and qualitative studies were excluded. The reasons for these exclusions are as follows: the economic evaluation studies might include the cost of cancer but do not address the primary aim of this review, namely, FT. Conference abstracts do not always present consistent and dependent data. Reviews were excluded because the designed protocols were different from this study; in addition, the outcome evaluation methods were different. Qualitative studies are more of a subjective nature, which cannot be pooled as per the protocol, and their analysis is different from the quantitative data.

2.3 Data extraction and quality assessment

The data were presented based on author date, type of cancer, study participants (sample size and sociodemographic characteristics such as age and gender), the prevalence of FT (subjective and objective), cost of illness, tools used to measure the FT, and quality scoring (Supplementary Table S2). The cost of illness is classified into direct and indirect costs. Direct costs are expenses that can be directly and specifically traced to a specific cost object (for example, the medicines consumed by a patient during his/her hospital stay). In contrast, indirect costs are defined as “expenses that cannot be directly linked to a specific cost object (e.g., labour costs) (21). The quality of all included articles was assessed using the Newcastle – Ottawa quality assessment scale for cohort and cross-sectional studies (adapted for cross-sectional studies), which comprises three sections: selection, comfortability, and outcome. The quality score is shown in Supplementary Table S2.

2.4 Data synthesis and analysis

Quantitative data were used to find the prevalence of FT. Review Manager 5.3 software was utilized to run the meta-analysis of quantitative data-reported studies. A random-effects meta-analysis was used to calculate pooled data with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The I2 index was utilized to assess the heterogeneity among studies, with values classified of ≤25%, 26–50%, and >50% as low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively (22, 23).

3 Results

3.1 Description of studies

The included studies were carried out worldwide, including in the USA (n = 30) (24–53), Europe (n = 10) (20, 54–62), Canada (n = 4) (63–66), Malaysia (n = 4) (67–70), Australia (n = 6) (71–76), Brazil (n = 2) (77, 78), China (n = 2) (79, 80), Iran (n = 2) (81, 82), Korea (n = 1) (83), Taiwan (n = 1) (84), Japan (n = 1) (85), and Ethiopia (n = 1) (86). A total of 47,964,650 cancer patients participated in a total of 64 studies carried out worldwide, with study samples ranging from 26 to 19.6 million. Out of the 64 studies, 15 studies included participants with any type of cancer (32, 35, 36, 39, 41, 44, 51, 52, 58, 65, 68, 72, 84–86), a mix of 2 or more types of cancers (10 studies) (27, 33, 38, 53, 56, 62, 69, 71, 79, 81), breast cancer (11 studies) (30, 40, 45–47, 50, 55, 66, 76, 82, 83), colorectal cancer (6 studies) (48, 57, 59, 67, 70, 75), colon cancer (n = 1) (49), skin cancer (3 studies) (20, 77, 78), lung cancer (2 studies) (54, 80), lung cancer with brain metastasis (1 study) (34), prostate cancer (3 studies) (63, 64, 74), pancreatic cancer (1 study) (28), bladder cancer (2 studies) (29, 31), head and neck cancers (n = 3 studies) (43, 60, 61), blood cancer (3 studies) (24, 26, 73), liver cancer (1 study) (42), gynecologic cancer (1 study) (25), and multiple myeloma (n = 1) (37).

3.2 Measurement of objective financial toxicity

Included research is rarely concentrated, particularly on measurable indicators of FT. Only five studies provided the measurement of objective FT in terms of the prevalence of catastrophic health expenditure (CHE), which was defined as a healthcare cost-to-income ratio of more than 40% in four studies (69, 70, 79, 80) and as the out-of-pocket payment (OOP) that exceeds 10% of total household income in one study (86).

3.3 The pooled prevalence of objective financial toxicity

A study conducted in Ethiopia reported a 74.4% prevalence of CHE. Two studies were carried out in Malaysia, one among colorectal cancer patients and the other among prostate, bladder, and renal cancer patients, and 47.8 and 16.1% of respondents, respectively, reported having experienced CHE (70, 80). Two studies were carried out in China; one study showed a total of 72.7% of participants experienced catastrophic health spending (69), and the other one showed the prevalence according to the state, where it was 87.3, 66.0, 33.7, and 19.6% in Chongqing, Fuzhou, Beijing, and Shanghai states, respectively (79). We pooled the findings of the last study (79) before including them in the meta-analysis; therefore, the prevalence of CHE in Mao et al. (79) was 51.65%. The last four studies enabled meta-analysis as they used the same method of measuring the CHE. As such, the pooled prevalence of CHE was 0.47 (95% CIs: 0.24–0.70), and the heterogeneity was high (I2 = 99%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Random-effects meta-analysis of studies that reported the prevalence of catastrophic health expenditure.

3.4 Measurement of subjective financial toxicity

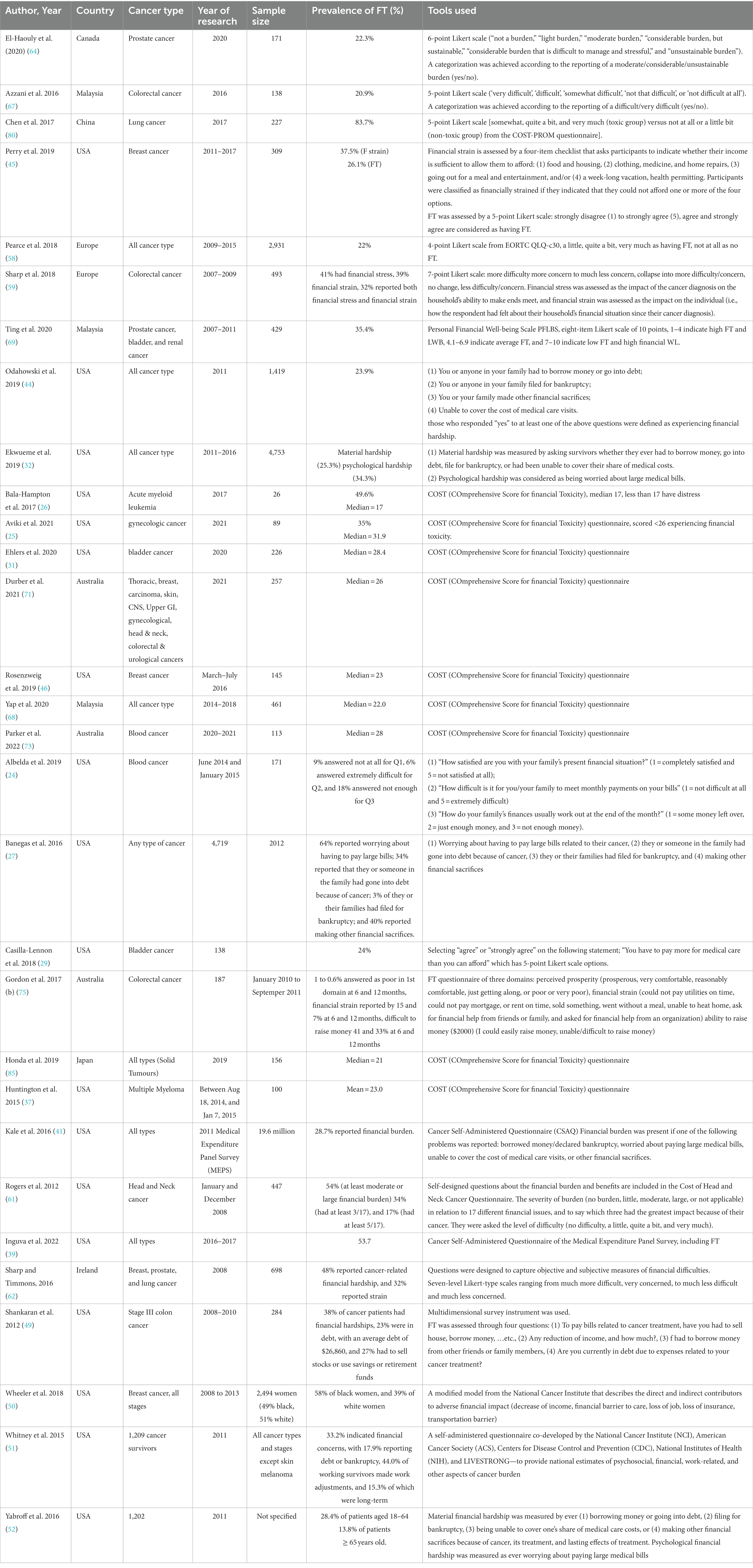

In total, 30 studies provided data on subjective FT (24–27, 29, 31, 32, 37, 39, 41, 44–46, 49–52, 58, 59, 61, 62, 64, 67–69, 71, 73, 75, 80, 85). The measures of FT varied widely among the studies. Nine of them used the COmprehensive Score for financial Toxicity (COST) tool, which had 11 items and a score ranged from 0 to 44, where lower COST values indicating higher financial toxicity (25, 26, 31, 37, 46, 68, 71, 73, 85). The median COST score in the included studies ranged between 17 and 31.9. The lowest score was reported among patients with acute myeloid leukemia and the highest among patients with gynecological cancers. Moreover, 10 studies used a 4- to 7-point Likert scale to assess the prevalence of subjective FT (24, 29, 45, 58, 59, 61, 62, 64, 67, 80), where the reported prevalence ranged between 20.9 and 83.7%. In addition, two studies used the median of COST as a cutoff point to assess those with and without FT (25, 26). One study used the Personal Financial Well-Being Scale (PFLBS), which consisted eight items on a Likert scale of 10 points, where 1–4 indicated high FT and LWB, 4.1–6.9 indicated average FT, and 7–10 indicated low FT and high financial WL (69). In addition, one study used four questions with “yes and no” answers to assess the subjective FT; those who responded “yes” to at least one of the four questions were defined as experiencing financial toxicity (44). Ekwueme et al. (2019) described the FT as material hardship and psychological hardship and found it to be 25.3% and 34.3% among the study participants, respectively. Three studies used four questions related to debt incurred, worry about paying bills, and making financial sacrifices as a measure of FT (27, 41, 49). In addition, one study in Australia assessed the FT using three questions related to perceived prosperity, financial strain, and the ability to raise money in an emergency (75) (Table 1).

3.5 Cost of cancer management

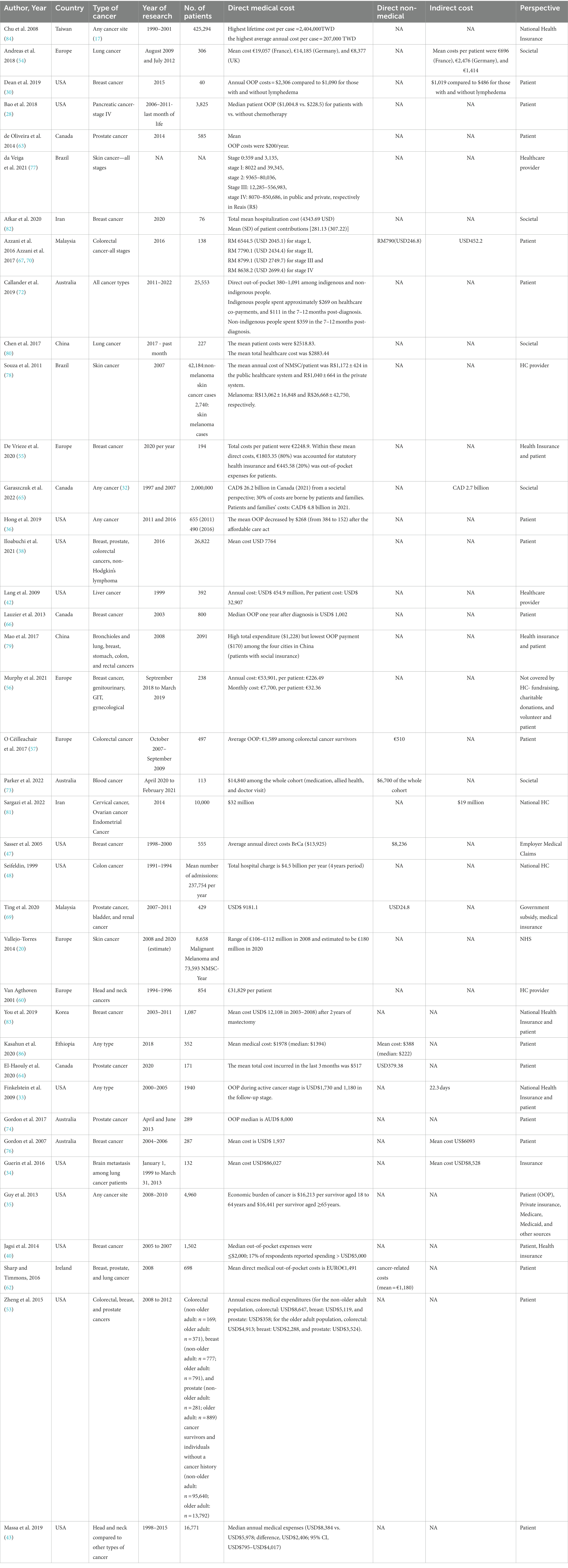

The cost of cancer management was also reported in the majority of included studies (20, 28, 30, 34–36, 38, 42, 43, 47, 48, 54–57, 60, 62–67, 69, 72–74, 76–84, 86).

3.5.1 Direct medical costs

Data on mean direct medical costs from different perspectives were reported in 39 studies in total (20, 28, 30, 33–36, 38, 40, 42, 43, 47, 48, 53–57, 60, 62–67, 69, 72–74, 76–84, 86). The period during which the expenditures were incurred varied widely in the included studies; some studies calculated the cost among cancer survivors (35, 40, 57), in the past 1 month (80), in the last month of life (28), and 2 years after diagnosis (83). The majority reported the annual cost (30, 33, 47, 48, 54–56, 63, 66, 78). Garaszczuk et al. (2022) found that most of the burden is incurred during the first year after diagnosis, and the most costly cancers are lung, colorectal, and prostate (65). The cost perspective varied widely among studies, with the majority using patient perspectives. However, few studies used the provider perspective or the societal perspective. In addition, some considered the cost of health insurance plans. Detailed cost data are shown in Table 2.

3.5.2 Direct non-medical costs

The direct non-medical cost was included in only seven studies (47, 57, 64, 67, 69, 73, 86). Two studies were conducted on colorectal cancer patients (44, 67): one in prostate cancer patients (64), one among patients of three types of cancer, namely bladder, prostate cancer, and renal cancer (69), one among blood cancer patients (73), and one among patients of any cancer type (86). The cost in the last 3 months for prostate cancer was USD$ 379.38 in Canada (64). For colorectal cancer, one study was done in Malaysia and found the cost to be USD$ 246.8 in the first year after diagnosis, and the other one was conducted in Europe and found the cost to be €510 in the three studied years (2007–2009) (57, 67). Ting et al. (2020) found that the cost per patient is USD$ 24.8 in Malaysia, and Parker et al. found that the cost in Australia is AUD$ 6,700 among blood cancer patients (73). In addition, the cost among cancer patients of any type in Ethiopia was USD$ 1,978 (86), and Sasser et al. (2005) found that the annual cost among breast cancer patients was USD$ 8,236. (Table 2).

3.5.3 Indirect cost

A total of eight studies reported the indirect cost of cancer management (30, 33, 34, 54, 65, 67, 76, 81). Total annual indirect costs in Europe per lung cancer patient were as follows: €696, €2,476, and €1,414 in France, Germany, and the UK, respectively (54). It was USD$ 1,019 compared to USD$ 48 for those with breast cancer with lymphadenoma compared to those without lymphadenoma, respectively, in the USA (30). In addition, the cost was USD$ 452.2 among colorectal cancer patients in Malaysia (67). Moreover, 10 years of indirect costs amounted to CAD$ 2.7 billion among patients of any cancer type in Canada (1097–2007) (65). It accounted for USD$ 19 million in Iran in 2014 among gynecology cancer patients (81). In addition, one study reported the work days missed due to disease rather than the cost of productivity lost (33) (Table 2).

4 Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis describe the prevalence of subjective and objective FT among cancer patients. The included studies are from different income countries and were published between 1999 and 2022. The majority of studies reported only direct medical costs (n = 39). Few studies (n = 7) reported direct non-medical costs, which include the cost of transportation, food, and accommodation due to disease, and similar findings were observed earlier (17). Moreover, only eight studies reported the indirect cost among cancer patients, which is defined as the cost of productivity loss of patients and their caregivers as a result of cancer. This was also hardly measured previously (17). Even though cancer care expenses are intuitive indications of the financial effects of cancer care, it was challenging to compare the included research cost findings due to the disparate illness course, type, stage, perspective, and the period during which the expenditures were incurred.

The medical expenditure–income ratio may be more suitable than a particular value for medical costs when evaluating cancer-related FT among patients. However, the definition and methods of measurement were contradictory in the included articles. For example, four studies used CHE to measure the household financial burden of healthcare payments, which is a well-established objective tool (87, 88). It is considered that a patient experiences a catastrophic situation when a household’s OOP healthcare expenditure exceeds 40% of the household’s capacity to pay (i.e., effective income remaining after basic subsistence needs have been fulfilled) (89). However, one study estimated the CHE using the Wagstaff and Van Doorslaer approach (90); when households with prior-year cancer patients’ OOP expenses for care exceeded 10% of their total annual household income, it was deemed catastrophic. As such, we only pooled the prevalence of CHE in four studies and found it equal to (47%) (69, 70, 79, 80), which is less than that found in a study conducted in a low-income country (74.4%) (86). However, this value represents only 11% of the included studies, which reflects that the included studies barely focused on measuring the objective FT.

Regarding the prevalence of subjective financial toxicity, it was found to range between 20.9 and 83.7%. There is a huge variation in measuring the subjective FT among the included studies. This finding confirms the earlier observation that there is a lack of accepted definitions of subjective FT (91). Similar findings have been reported by a previous systematic review, which synthesized methods for measuring FT (8, 17). Recently, a few standardized instruments have been developed and validated in an attempt to quantify the financial toxicity of cancer patients. An example of a COST tool is the de Souza (92) instrument, which was developed in 2014 and validated and used in high- and higher-middle-income countries to measure cancer patients’ experiences of financial toxicity. However, it may not apply to lower-middle or low-income countries. The median COST score among included studies [USA (n = 5), Australia (n = 2), Japan (n = 1), and Malaysia (n = 1)] ranged between 17 among acute myeloid leukemia and 31.9 among patients with gynecological cancers, in which a low score indicated high financial toxicity (92). Some studies used the median COST score as a cutoff point to define those experiencing FT (25, 26). However, there was a wide variation in the median of included studies, which might require a validation study on COST to standardize the cutoff point to categorize those experiencing FT.

The strength of this study is that it is the first systematic study and meta-analysis to determine the amount of cancer-related financial toxicity and how it has been measured in various income countries. However, this study has several limitations. First, due to the considerable heterogeneity in the outcome measurement utilized in the included studies, our summary of the findings was narrative rather than quantitative (except for CHE). Second, owing to the considerable heterogeneity in the disease period or course during which the costs were incurred, unknowns and inconsistencies in the amount and type of resources included, inflation, and currency rates, we did not synthesize or compare cancer-related expenditures (including medical, non-medical, and indirect costs) across studies.

5 Implication and recommendation

Regular clinical evaluations rarely include FT assessments. According to this review, FT affects cancer patients and their families negatively and is common among cancer patients around the world. As a result, in clinical practice, FT in cancer patients needs to get more attention. The evaluation, acknowledgment, and discussion of financial toxicity are crucial milestones. Nurses can work with doctors to analyze patients’ financial burdens and provide information assistance for cancer patients because they have the closest touch with cancer patients and their careers. Therefore, the government, cancer foundations, and other organizations should adopt initiatives such as education and training programs to expand nurses’ awareness of FT assessment and patient assistance programs.

More high-quality research is required, especially from low-income nations, on the FT of cancer. A tool to quantify FT in cancer patients has to be developed and validated in further research.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

MA: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. WA: Writing – review & editing. DA: Writing – original draft. VK: Writing – original draft. MA: Writing – original draft.

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia GGPM grant, (GGPM-2023-020). The authors gratefully acknowledge Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia for the approved funding that allows this important research to be carried out.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1266533/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Ferlay, J, Ervik, M, Lam, F, Colombet, M, Mery, L, Piñeros, M, et al. Global Cancer observatory: Cancer today. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer (2020).

2. Bray, F, Ferlay, J, Soerjomataram, I, Siegel, RL, Torre, LA, and Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. (2018) 68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492

3. Ghoncheh, M, and Salehiniya, H. Inequality in the incidence and mortality of all cancers in the world. Iran J Public Health. (2016) 45:1675–7.

4. Steliarova-Foucher, E, Colombet, M, Ries, LAG, Moreno, F, Dolya, A, Bray, F, et al. International incidence of childhood cancer, 2001-10: a population-based registry study. Lancet Oncol. (2017) 18:719–31. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30186-9

5. Milroy, MJ. Outlining the crisis in Cancer care In: P Hopewood and MJ Milroy, editors. Quality Cancer care: Survivorship before, during and after treatment. Cham: Springer International Publishing (2018). 1–12.

6. Carrera, PM, Kantarjian, HM, and Blinder, VS. The financial burden and distress of patients with cancer: understanding and stepping-up action on the financial toxicity of cancer treatment. CA Cancer J Clin. (2018) 68:153–65. doi: 10.3322/caac.21443

7. Desai, A, and Gyawali, B. Financial toxicity of cancer treatment: moving the discussion from acknowledgement of the problem to identifying solutions. EClinicalMedicine. (2020) 20:100269. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100269

8. Witte, J, Mehlis, K, Surmann, B, Lingnau, R, Damm, O, Greiner, W, et al. Methods for measuring financial toxicity after cancer diagnosis and treatment: a systematic review and its implications. Ann Oncol. (2019) 30:1061–70. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz140

9. Lentz, R, Benson, AB 3rd, and Kircher, S. Financial toxicity in cancer care: prevalence, causes, consequences, and reduction strategies. J Surg Oncol. (2019) 120:85–92. doi: 10.1002/jso.25374

10. Zafar, SY. Financial toxicity of Cancer care: It's time to intervene. J Natl Cancer Inst. (2016) 108:djv370. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv370

11. Tucker-Seeley, RD, and Yabroff, KR. Minimizing the "financial toxicity" associated with cancer care: advancing the research agenda. J Natl Cancer Inst. (2016) 108:djv410. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv410

12. Arastu, A, Patel, A, Mohile, SG, Ciminelli, J, Kaushik, R, Wells, M, et al. Assessment of financial toxicity among older adults with advanced Cancer. JAMA Netw Open. (2020) 3:e2025810. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.25810

13. Gordon, LG, Merollini, KMD, Lowe, A, and Chan, RJ. A systematic review of financial toxicity among Cancer survivors: we Can't pay the co-pay. Patient. (2017) 10:295–309. doi: 10.1007/s40271-016-0204-x

14. Baddour, K, Fadel, M, Zhao, M, Corcoran, M, Owoc, MS, Thomas, TH, et al. The cost of cure: examining objective and subjective financial toxicity in head and neck cancer survivors. Head Neck. (2021) 43:3062–75. doi: 10.1002/hed.26801

15. Ramsey, S, Blough, D, Kirchhoff, A, Kreizenbeck, K, Fedorenko, C, Snell, K, et al. Washington state cancer patients found to be at greater risk for bankruptcy than people without a cancer diagnosis. Health Aff (Millwood). (2013) 32:1143–52. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1263

16. Ramsey, SD, Bansal, A, Fedorenko, CR, Blough, DK, Overstreet, KA, Shankaran, V, et al. Financial insolvency as a risk factor for early mortality among patients with Cancer. J Clin Oncol. (2016) 34:980–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.6620

17. Donkor, A, Atuwo-Ampoh, VD, Yakanu, F, Torgbenu, E, Ameyaw, EK, Kitson-Mills, D, et al. Financial toxicity of cancer care in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer. (2022) 30:7159–90. doi: 10.1007/s00520-022-07044-z

18. Mols, F, Tomalin, B, Pearce, A, Kaambwa, B, and Koczwara, B. Financial toxicity and employment status in cancer survivors. A systematic literature review. Support Care Cancer. (2020) 28:5693–708. doi: 10.1007/s00520-020-05719-z

19. Page, MJ, McKenzie, JE, Bossuyt, PM, Boutron, I, Hoffmann, TC, Mulrow, CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. (2021) 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

20. Vallejo-Torres, L, Morris, S, Kinge, JM, Poirier, V, and Verne, J. Measuring current and future cost of skin cancer in England. J Public Health (Oxf). (2014) 36:140–8. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdt032

21. Špacírová, Z, Epstein, D, García-Mochón, L, Rovira, J, de Labry, O, Lima, A, et al. A general framework for classifying costing methods for economic evaluation of health care. Eur J Health Econ. (2020) 21:529–42. doi: 10.1007/s10198-019-01157-9

22. McKenzie, JE, Beller, EM, and Forbes, AB. Introduction to systematic reviews and meta-analysis. Respirology. (2016) 21:626–37. doi: 10.1111/resp.12783

23. Higgins, JPT, Thompson, SG, Deeks, JJ, and Altman, DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. (2003) 327:557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557

24. Albelda, R, Wiemers, E, Hahn, T, Khera, N, Salas Coronado, DY, and Abel, GA. Relationship between paid leave, financial burden, and patient-reported outcomes among employed patients who have undergone bone marrow transplantation. Qual Life Res. (2019) 28:1835–47. doi: 10.1007/s11136-019-02150-8

25. Aviki, EM, Thom, B, Braxton, K, Chi, AJ, Manning-Geist, B, Chino, F, et al. Patient-reported benefit from proposed interventions to reduce financial toxicity during cancer treatment. Support Care Cancer. (2022) 30:2713–21. doi: 10.1007/s00520-021-06697-6

26. Bala-Hampton, JE, Dudjak, L, Albrecht, T, and Rosenzweig, MQ. Perceived economic hardship and distress in acute myelogenous Leukemia. J. Oncol. Navigation Survivorship. (2017) 8:1–9.

27. Banegas, MP, Guy, GP Jr, de Moor, JS, Ekwueme, DU, Virgo, KS, Kent, EE, et al. For working-age Cancer survivors, medical debt and bankruptcy create financial hardships. Health Aff (Millwood). (2016) 35:54–61. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0830

28. Bao, Y, Maciejewski, RC, Garrido, MM, Shah, MA, Maciejewski, PK, and Prigerson, HG. Chemotherapy use, end-of-life care, and costs of care among patients diagnosed with stage IV pancreatic Cancer. J Pain Symptom Manag. (2018) 55:1113–21 e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.12.335

29. Casilla-Lennon, MM, Choi, SK, Deal, AM, Bensen, JT, Narang, G, Filippou, P, et al. Financial toxicity among patients with bladder Cancer: reasons for delay in care and effect on quality of life. J Urol. (2018) 199:1166–73. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2017.10.049

30. Dean, LT, Moss, SL, Ransome, Y, Frasso-Jaramillo, L, Zhang, Y, Visvanathan, K, et al. "it still affects our economic situation": long-term economic burden of breast cancer and lymphedema. Support Care Cancer. (2019) 27:1697–708. doi: 10.1007/s00520-018-4418-4

31. Ehlers, M, Bjurlin, M, Gore, J, Pruthi, R, Narang, G, Tan, R, et al. A national cross-sectional survey of financial toxicity among bladder cancer patients. Urol Oncol. (2021) 39:76e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2020.09.030

32. Ekwueme, DU, Zhao, J, Rim, SH, de Moor, JS, Zheng, Z, Khushalani, JS, et al. Annual out-of-pocket expenditures and financial hardship among cancer survivors aged 18–64 years—United States, 2011–2016. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. (2019) 68:494. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6822a2

33. Finkelstein, EA, Tangka, FK, Trogdon, JG, Sabatino, SA, and Richardson, LC. The personal financial burden of cancer for the working-aged population. Am J Manag Care. (2009) 15:801–6.

34. Guérin, A, Sasane, M, Dea, K, Zhang, J, Culver, K, Nitulescu, R, et al. The economic burden of brain metastasis among lung cancer patients in the United States. J Med Econ. (2016) 19:526–36. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2016.1138962

35. Guy, GP Jr, Ekwueme, DU, Yabroff, KR, Dowling, EC, Li, C, Rodriguez, JL, et al. Economic burden of cancer survivorship among adults in the United States. J Clin Oncol. (2013) 31:3749–57. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.1241

36. Hong, Y-R, Smith, GL, Xie, Z, Mainous, AG, and Huo, J. Financial burden of cancer care under the affordable care act: analysis of MEPS-experiences with cancer survivorship 2011 and 2016. J Cancer Surviv. (2019) 13:523–36. doi: 10.1007/s11764-019-00772-y

37. Huntington, SF, Weiss, BM, Vogl, DT, Cohen, AD, Garfall, AL, Mangan, PA, et al. Financial toxicity in insured patients with multiple myeloma: a cross-sectional pilot study. Lancet Haematol. (2015) 2:e408–16. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(15)00151-9

38. Iloabuchi, C, Dwibedi, N, LeMasters, T, Shen, C, Ladani, A, and Sambamoorthi, U. Low-value care and excess out-of-pocket expenditure among older adults with incident cancer–a machine learning approach. J Cancer Policy. (2021) 30:100312. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpo.2021.100312

39. Inguva, S, Priyadarshini, M, Shah, R, and Bhattacharya, K. Financial toxicity and its impact on health outcomes and caregiver burden among adult cancer survivors in the USA. Future Oncol. (2022) 18:1569–81. doi: 10.2217/fon-2021-1282

40. Jagsi, R, Pottow, JA, Griffith, KA, Bradley, C, Hamilton, AS, Graff, J, et al. Long-term financial burden of breast cancer: experiences of a diverse cohort of survivors identified through population-based registries. J Clin Oncol. (2014) 32:1269–76. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.0956

41. Kale, HP, and Carroll, NV. Self-reported financial burden of cancer care and its effect on physical and mental health-related quality of life among US cancer survivors. Cancer. (2016) 122:283–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29808

42. Lang, K, Danchenko, N, Gondek, K, Shah, S, and Thompson, D. The burden of illness associated with hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. J Hepatol. (2009) 50:89–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.07.029

43. Massa, ST, Osazuwa-Peters, N, Adjei Boakye, E, Walker, RJ, and Ward, GM. Comparison of the financial burden of survivors of head and neck Cancer with other Cancer survivors. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. (2019) 145:239–49. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2018.3982

44. Odahowski, CL, Zahnd, WE, Zgodic, A, Edward, JS, Hill, LN, Davis, MM, et al. Financial hardship among rural cancer survivors: an analysis of the medical expenditure panel survey. Prev Med. (2019) 129:105881. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.105881

45. Perry, LM, Hoerger, M, Seibert, K, Gerhart, JI, O'Mahony, S, and Duberstein, PR. Financial strain and physical and emotional quality of life in breast cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. (2019) 58:454–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.05.011

46. Rosenzweig, M, West, M, Matthews, J, Stokan, M, Kook, Y, Gallups, S, et al. Financial toxicity among women with metastatic breast Cancer. Oncology nursing forum (2019)

47. Sasser, AC, Rousculp, MD, Birnbaum, HG, Oster, EF, Lufkin, E, and Mallet, D. Economic burden of osteoporosis, breast cancer, and cardiovascular disease among postmenopausal women in an employed population. Womens Health Issues. (2005) 15:97–108. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2004.11.006

48. Seifeldin, R, and Hantsch, JJ. The economic burden associated with colon cancer in the United States. Clin Ther. (1999) 21:1370–9. doi: 10.1016/S0149-2918(99)80037-X

49. Shankaran, V, Jolly, S, Blough, D, and Ramsey, SD. Risk factors for financial hardship in patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer: a population-based exploratory analysis. J Clin Oncol. (2012) 30:1608–14. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.9511

50. Wheeler, SB, Spencer, JC, Pinheiro, LC, Carey, LA, Olshan, AF, and Reeder-Hayes, KE. Financial impact of breast Cancer in black versus white women. J Clin Oncol. (2018) 36:1695–701. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.77.6310

51. Whitney, RL, Bell, JF, Reed, SC, Lash, R, Bold, RJ, Kim, KK, et al. Predictors of financial difficulties and work modifications among cancer survivors in the United States. J Cancer Surviv. (2016) 10:241–50. doi: 10.1007/s11764-015-0470-y

52. Yabroff, KR, Dowling, EC, Guy, GP Jr, Banegas, MP, Davidoff, A, Han, X, et al. Financial hardship associated with Cancer in the United States: findings from a population-based sample of adult Cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. (2016) 34:259–67. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.0468

53. Zheng, Z, Yabroff, KR, Guy, GP Jr, Han, X, Li, C, Banegas, MP, et al. Annual medical expenditure and productivity loss among colorectal, female breast, and prostate cancer survivors in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. (2016) 108:djv382. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv382

54. Andreas, S, Chouaid, C, Danson, S, Siakpere, O, Benjamin, L, Ehness, R, et al. Economic burden of resected (stage IB-IIIA) non-small cell lung cancer in France, Germany and the United Kingdom: a retrospective observational study (LuCaBIS). Lung Cancer. (2018) 124:298–309. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2018.06.007

55. De Vrieze, T, Gebruers, N, Nevelsteen, I, Tjalma, WAA, Thomis, S, De Groef, A, et al. Breast cancer-related lymphedema and its treatment: how big is the financial impact? Support Care Cancer. (2021) 29:3801–13. doi: 10.1007/s00520-020-05890-3

56. Murphy, A, Chu, RW, and Drummond, FJ. A cost analysis of a community-based support Centre for cancer patients and their families in Ireland: the EVeCANs study. Support Care Cancer. (2021) 29:619–25. doi: 10.1007/s00520-020-05508-8

57. Ó Céilleachair, A, Hanly, P, Skally, M, O’Leary, E, O’Neill, C, Fitzpatrick, P, et al. Counting the cost of cancer: out-of-pocket payments made by colorectal cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. (2017) 25:2733–41. doi: 10.1007/s00520-017-3683-y

58. Pearce, A, Tomalin, B, Kaambwa, B, Horevoorts, N, Duijts, S, Mols, F, et al. Financial toxicity is more than costs of care: the relationship between employment and financial toxicity in long-term cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. (2019) 13:10–20. doi: 10.1007/s11764-018-0723-7

59. Sharp, L, O’Leary, E, O’Ceilleachair, A, Skally, M, and Hanly, P. Financial impact of colorectal cancer and its consequences: associations between cancer-related financial stress and strain and health-related quality of life. Dis Colon Rectum. (2018) 61:27–35. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000923

60. van Agthoven, M, Van Ineveld, B, De Boer, M, Leemans, C, Knegt, P, Snow, G, et al. The costs of head and neck oncology: primary tumours, recurrent tumours and long-term follow-up. Eur J Cancer. (2001) 37:2204–11. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(01)00292-1

61. Rogers, SN, Harvey-Woodworth, CN, Hare, J, Leong, P, and Lowe, D. Patients' perception of the financial impact of head and neck cancer and the relationship to health related quality of life. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. (2012) 50:410–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2011.07.026

62. Sharp, L, and Timmons, A. Pre-diagnosis employment status and financial circumstances predict cancer-related financial stress and strain among breast and prostate cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. (2016) 24:699–709. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2832-4

63. de Oliveira, C, Bremner, KE, Ni, A, Alibhai, SM, Laporte, A, and Krahn, MD. Patient time and out-of-pocket costs for long-term prostate cancer survivors in Ontario. Canada J Cancer Surviv. (2014) 8:9–20. doi: 10.1007/s11764-013-0305-7

64. El-Haouly, A, Lacasse, A, El-Rami, H, Liandier, F, and Dragomir, A. Out-of-pocket costs and perceived financial burden associated with prostate Cancer treatment in a Quebec remote area: a cross-sectional study. Curr Oncol. (2020) 28:26–39. doi: 10.3390/curroncol28010005

65. Garaszczuk, R, Yong, JH, Sun, Z, and de Oliveira, C. The economic burden of Cancer in Canada from a societal perspective. Curr Oncol. (2022) 29:2735–48. doi: 10.3390/curroncol29040223

66. Lauzier, S, Lévesque, P, Mondor, M, Drolet, M, Coyle, D, Brisson, J, et al. Out-of-pocket costs in the year after early breast cancer among Canadian women and spouses. J National Cancer Institute. (2013) 105:280–92. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs512

67. Azzani, M, Roslani, AC, and Su, TT. Financial burden of colorectal cancer treatment among patients and their families in a middle-income country. Support Care Cancer. (2016) 24:4423–32. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3283-2

68. Yap, SL, Wong, SS, Chew, KS, Kueh, JS, and Siew, KL. Assessing the relationship between socio-demographic, clinical profile and financial toxicity: evidence from Cancer survivors in Sarawak. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. (2020) 21:3077–83. doi: 10.31557/APJCP.2020.21.10.3077

69. Ting, CY, Teh, GC, Yu, KL, Alias, H, Tan, HM, and Wong, LP. Financial toxicity and its associations with health-related quality of life among urologic cancer patients in an upper middle-income country. Support Care Cancer. (2020) 28:1703–15. doi: 10.1007/s00520-019-04975-y

70. Azzani, M, Yahya, A, Roslani, A, and Su, T. Catastrophic health expenditure among colorectal Cancer patients and families: a case of Malaysia. Asia Pacific J Public Health. (2017) 29:485–94. doi: 10.1177/1010539517732224

71. Durber, K, Halkett, GK, McMullen, M, and Nowak, AK. Measuring financial toxicity in Australian cancer patients–validation of the Comprehensive score for financial toxicity (FACT COST) measuring financial toxicity in Australian cancer patients. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. (2021) 17:377–87. doi: 10.1111/ajco.13508

72. Callander, E, Bates, N, Lindsay, D, Larkins, S, Preston, R, Topp, SM, et al. The patient co-payment and opportunity costs of accessing healthcare for indigenous Australians with cancer: a whole of population data linkage study. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. (2019) 15:309–15. doi: 10.1111/ajco.13180

73. Parker, C, Ayton, D, Zomer, E, Liew, D, Vassili, C, Fong, CY, et al. Do patients with haematological malignancies suffer financial burden? A cross-sectional study of patients seeking care through a publicly funded healthcare system. Leuk Res. (2022) 113:106786. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2022.106786

74. Gordon, LG, Walker, SM, Mervin, MC, Lowe, A, Smith, DP, Gardiner, RA, et al. Financial toxicity: a potential side effect of prostate cancer treatment among Australian men. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). (2017) 26. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12392

75. Gordon, LG, Beesley, VL, Mihala, G, Koczwara, B, and Lynch, BM. Reduced employment and financial hardship among middle-aged individuals with colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). (2017) 26. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12744

76. Gordon, L, Scuffham, P, Hayes, S, and Newman, B. Exploring the economic impact of breast cancers during the 18 months following diagnosis. Psychooncology. (2007) 16:1130–9. doi: 10.1002/pon.1182

77. da Veiga, CRP, da Veiga, CP, Souza, A, Wainstein, AJA, de Melo, AC, and Drummond-Lage, AP. Cutaneous melanoma: cost of illness under Brazilian health system perspectives. BMC Health Serv Res. (2021) 21:284. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06246-1

78. Souza, RJSAP, Mattedi, AP, Corrêa, MP, Rezende, ML, and Ferreira, ACA. An estimate of the cost of treating non-melanoma skin cancer in the state of São Paulo, Brazil. An Bras Dermatol. (2011) 86:657–62. doi: 10.1590/S0365-05962011000400005

79. Mao, W, Tang, S, Zhu, Y, Xie, Z, and Chen, W. Financial burden of healthcare for cancer patients with social medical insurance: a multi-centered study in urban China. Int J Equity Health. (2017) 16:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12939-017-0675-y

80. Chen, JE, Lou, VW, Jian, H, Zhou, Z, Yan, M, Zhu, J, et al. Objective and subjective financial burden and its associations with health-related quality of life among lung cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. (2018) 26:1265–72. doi: 10.1007/s00520-017-3949-4

81. Sargazi, N, Daroudi, R, Zendehdel, K, Hashemi, FA, Tahmasebi, M, Darrudi, A, et al. Economic burden of Gynecological cancers in Iran. Value Health Reg Issues. (2022) 28:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.vhri.2021.02.005

82. Afkar, A, Heydari, S, Jalilian, H, Pourreza, A, and Emami, SA. Hospitalization costs of breast cancer before and after the implementation of the health sector evolution plan (HSEP), Iran, 2017: a retrospective single-centre study. J Cancer Policy. (2020) 24:100228. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpo.2020.100228

83. You, CH, Kang, S, and Kwon, YD. The economic burden of breast Cancer survivors in Korea: a descriptive study using a 26-month Micro-costing cohort approach. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. (2019) 20:2131–7. doi: 10.31557/APJCP.2019.20.7.2131

84. Chu, PC, Hwang, JS, Wang, JD, and Chang, YY. Estimation of the financial burden to the National Health Insurance for patients with major cancers in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc. (2008) 107:54–63. doi: 10.1016/S0929-6646(08)60008-X

85. Honda, K, Gyawali, B, Ando, M, Kumanishi, R, Kato, K, Sugiyama, K, et al. Prospective survey of financial toxicity measured by the comprehensive score for financial toxicity in Japanese patients with Cancer. J Glob Oncol. (2019) 5:1–8. doi: 10.1200/JGO.19.00003

86. Kasahun, GG, Gebretekle, GB, Hailemichael, Y, Woldemariam, AA, and Fenta, TG. Catastrophic healthcare expenditure and coping strategies among patients attending cancer treatment services in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. (2020) 20:984. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09137-y

87. Berki, SE. A look at catastrophic medical expenses and the poor. Health Aff (Millwood). (1986) 5:138–45. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.5.4.138

88. World Health O. Distribution of health payments and catastrophic expenditures methodology/by Ke Xu. Geneva: World Health Organization (2005).

89. Xu, K, Evans, DB, Kawabata, K, Zeramdini, R, Klavus, J, and Murray, CJ. Household catastrophic health expenditure: a multicountry analysis. Lancet. (2003) 362:111–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13861-5

90. Wagstaff, A, and van Doorslaer, E. Catastrophe and impoverishment in paying for health care: with applications to Vietnam 1993-1998. Health Econ. (2003) 12:921–34. doi: 10.1002/hec.776

91. Pauge, S, Surmann, B, Mehlis, K, Zueger, A, Richter, L, Menold, N, et al. Patient-reported financial distress in Cancer: a systematic review of risk factors in universal healthcare systems. Cancers (Basel). (2021) 13:5015. doi: 10.3390/cancers13195015

Keywords: direct medical cost, direct non-medical cost, indirect medical cost, catastrophic health expenditure, perceived financial hardship, systematic review, meta-analysis

Citation: Azzani M, Atroosh WM, Anbazhagan D, Kumarasamy V and Abdalla MMI (2024) Describing financial toxicity among cancer patients in different income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Public Health. 11:1266533. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1266533

Edited by:

Jeffrey Harrison, University of North Florida, United StatesReviewed by:

Zuzana Špacírová, Andalusian School of Public Health, SpainChiara Cadeddu, Erasmus University Rotterdam, Netherlands

Copyright © 2024 Azzani, Atroosh, Anbazhagan, Kumarasamy and Abdalla. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Vinoth Kumarasamy, dmlub3RoQHVrbS5lZHUubXk=

Meram Azzani

Meram Azzani Wahib Mohammed Atroosh

Wahib Mohammed Atroosh Deepa Anbazhagan

Deepa Anbazhagan Vinoth Kumarasamy

Vinoth Kumarasamy Mona Mohamed Ibrahim Abdalla

Mona Mohamed Ibrahim Abdalla