- 1Manning College of Nursing and Health Science, University of Massachusetts Boston, Boston, MA, United States

- 2Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, United States

- 3Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA, United States

Introduction: Family engagement and patient-family-centered care are vitally important to improve outcomes for patients, families, providers, hospitals, and communities. Both constructs prioritize providers forming partnerships with patients and their families. The domains of family-engaged care include presence, communication, shared-decision making, family needs, contribution to care, and collaboration at the institutional level. This integrative review describes the extent to which the domains of family engagement are present in the literature about Covid-era hospital visiting policies.

Methods: A search of four databases resulted in 127 articles and one added through data mining. After review, 28 articles were synthesized and analyzed into an integrative review of family engagement in the hospital with Covid-era visiting policies as the backdrop.

Results: The 28-article review resulted in an international, multidisciplinary perspective of diverse study designs. The review’s sample population includes 6,984 patients, 1,126 family members, 1,174 providers, 96 hospitals, 50 health centers, 1 unit, and 257 documents. While all the domains are represented, presence is the prevailing domain, identified in 25 out of the 28 (89%).

Discussion: Presence is recognized as facilitating the other domains. Because the concept of collaboration is largely absent in the literature, it may provide healthcare institutions with a growth opportunity to facilitate and promote family engagement. This review is the first step in operationalizing family engagement in the hospital setting, especially when presence is challenging.

1. Introduction

Family engagement has been identified as a construct that is vitally important to successful outcomes for patients, families, providers, hospitals, and communities. Hospitals often are the setting of new or worsening diagnoses for older and seriously ill patients. Family, as defined by the patient, refers to a trusted individual or group of individuals and does not necessarily reflect a legal relationship. Family engagement improves healthcare quality and safety and, therefore, patient outcomes in the hospital (1, 2). Family engagement at the end of a patient’s life has a broader scope of impact than on the patient alone. It is an antecedent and an attribute of a good death, facilitating healthy bereavement for families and job satisfaction for providers (3). In addition to improving health outcomes for the patient, family engagement also benefits the hospital. Families provide information, context, care coordination, and help with the transition home (4). Family engagement decreases readmission rates (5) and reduces overall healthcare utilization (6).

The constructs of Family Engagement and Patient and Family Centered Care overlap and run along a continuum that includes passive and active family involvement (7). With older adults, family engagement can be episodic, as seen in a new cancer diagnosis, or progressive, as seen in a dementia diagnosis (8). The six foundational components of the family engagement construct are presence, meeting family needs, communication, shared decision-making, contribution to care, and collaboration (7, 9). While the components of family engagement may require different levels of family involvement, they are not linear or discreet and are, in fact, interdependent (7). The physical presence of the family bedside, the least active of the domains, is often the precursor to the other components. The second component, meeting family needs or respect, focuses on building an effective partnership between families and providers by recognizing the family’s need for information, comfort, or resources (7, 9). Communication or information sharing between family and provider is a third family engagement component (7, 9). Shared decision-making is the fourth component of family involvement and is considered a more active form of family engagement that cannot be wholly unbraided from communication (7). The fifth, contribution to care, is the most active family involvement and encompasses physical and emotional support that the family may give the patient (7). The final component is collaboration and includes the family as a stakeholder at the institutional and policy level (9).

Family engagement is an invaluable resource to the community worldwide. For example, in 2020 in the United States, over 53 million adults reported being informal caregivers, an increase from 43.5 million caregivers in 2015 (10). In Massachusetts alone, informal caregivers provide almost 800 million hours of care, translating to nearly $12 billion annually (11). In the United States and other parts of the world, caregiving is not shared equally across the population. Most caregivers are women (12), and in the United States, black caregivers provide approximately 400 more hours a year than white caregivers (13). In addition to the gender and racial inequities that may exist, there are geographic disparities. Caregivers in rural areas have less access to support, making the intensity and burden greater in those areas (14). How informal caregiving translates to family engagement in the hospital is unknown.

Until the pandemic, restrictive visiting policies were often only seen in critical care units, where patient care is particularly complicated. However, in January 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared SARS-CoV-2, often called Covid, an international public health emergency and went on to give operational guidance to hospitals to contain the spread of the virus by severely restricting both the number of visitors and the length of the visiting period (15). Visitor policies vary from one region to another, from one institution to another, and even within a particular institution between units. The extent to which the Covid-era visiting policies affect family engagement in the hospital is unknown. The dramatic change to visiting policies may offer an opportunity to learn more about family engagement in the hospital setting, revealing which domains are underutilized and, therefore, may offer the best growth opportunities. The integrative review aims to describe the extent to which the domains of family engagement are present in the literature about visiting policy; what domains the literature focus on, and where might the gaps in the literature be.

2. Framework

Integrative reviews synthesize empirical and theoretical literature to build nursing science and health policy (16). This review is guided by the Conceptual Model of Nursing and Health Policy (CMNHP). It focuses on the unique role of nursing within the multidisciplinary health policy domain (17). CMNHP recognizes nurses’ critical role in creating and implementing health policy (17). This review focuses on hospital visiting policies at the first level, which centers on individuals, families, and communities (17).

3. Methods

One researcher (JM), a clinical nurse and doctoral student, searched four databases, CINAHL, PubMed, Medline EBSCO, and Ovid. After meeting with a healthcare librarian, the search terms “hospital visitor policy” and “hospital visiting policy” were used to keep the results broad. To keep the search unbiased, the researcher avoided using the terms “restrictive” and “no-visiting.” The range of dates is narrow, including literature from 2020 to early 2023, to ensure that the results capture the Covid-era visiting policies. Articles were included if published in English and covered the adult population. Articles that were pre-Covid or were set outside of a hospital setting were excluded. Articles related to the pediatric population were also excluded because there are different ethical and practice considerations with pediatric populations related to family engagement and visiting policies. The researcher met regularly from conception through completion with the two other authors (LH and PG), experienced researchers, professors, and experts in health policy and serious illness. Questions and concerns were settled by consensus. Additionally, the research findings were presented to a group of peers to identify questions, concerns, and oversites.

4. Search results

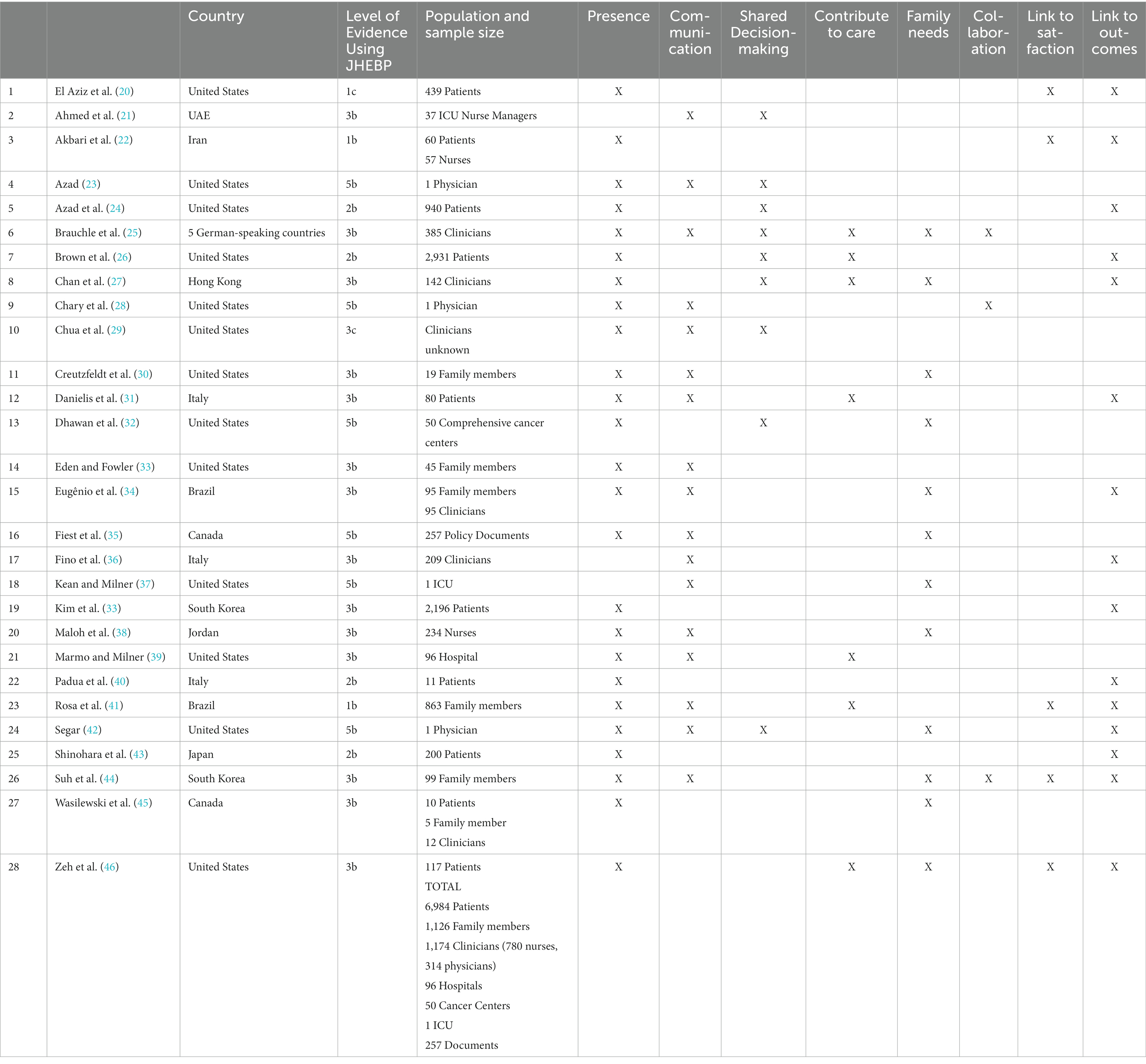

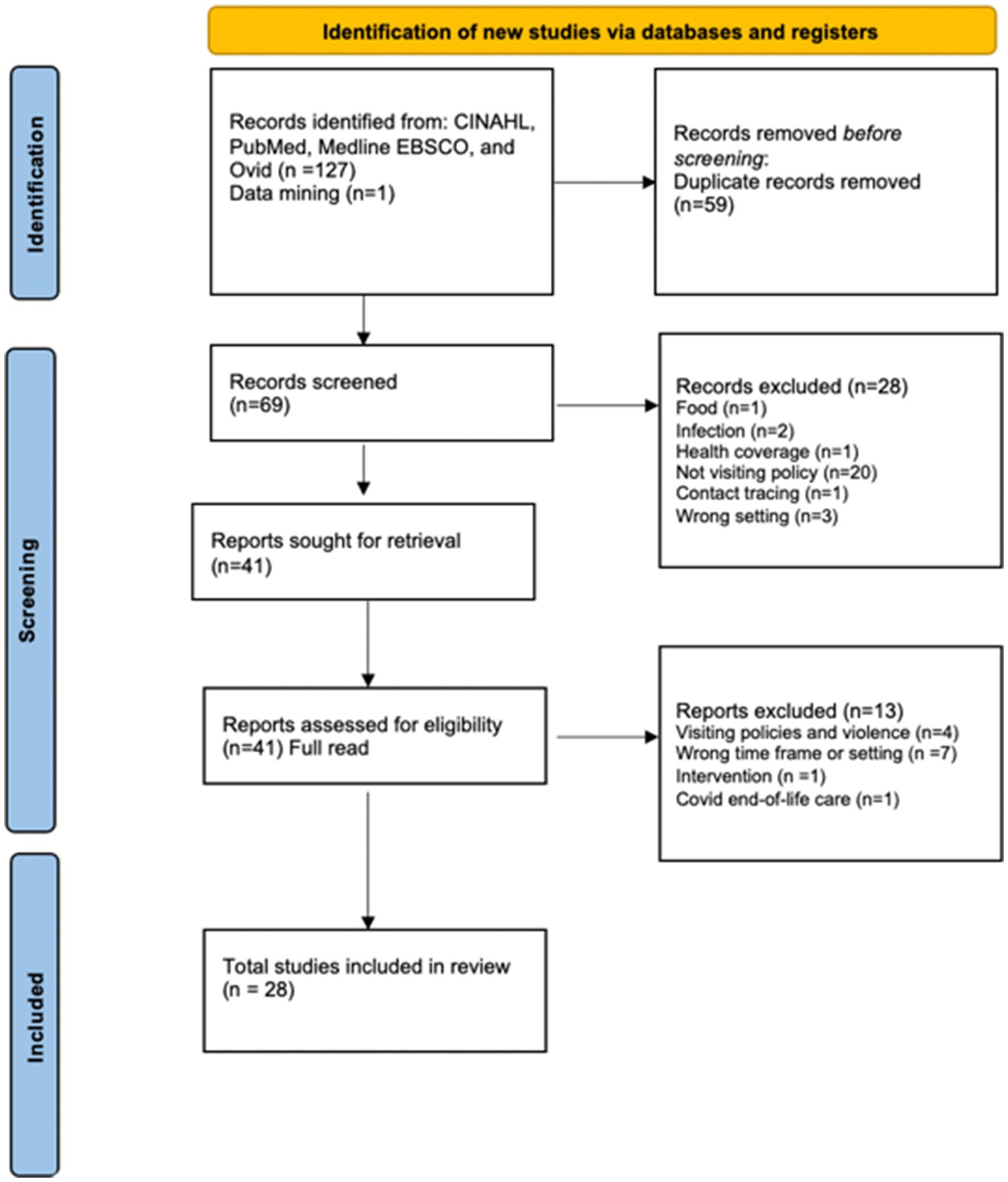

The search of CINAHL, PubMed, Medline EBSCO, and Ovid resulted in 127 studies being retrieved, with one article added through data mining. Fifty-nine duplicate articles were removed. A title search removed 28 articles, leaving 41 to read in full. Thirteen articles were then excluded after a full read. Four articles were excluded because they focused on visiting policies related to violence. Seven articles were excluded because they were in the wrong time frame (pre-Covid) or setting (long-term care or physician visits). One article was excluded because it was focused on family engagement as an intervention and did not include visiting policies; another was excluded because it was focused on the impact of Covid on end-of-life care and not on visiting policies. After reviewing the articles, the integrated review includes 28 articles. Figure 1 provides the PRISMA diagram of the screening of the documents for the integrated review (18).

Figure 1. Integrative review of Covid-era visiting policy literature. *Consider, if feasible to do so, reporting the number of records identified from each database or register searched (rather than the total number across all databases/registers). **If automation tools were used, indicate how many records were excluded by a human and how many were excluded by automation tools. From Page et al. (18). *EBSCO = 47, Pubmed = 47, CINAHL= 30, Ovid= 4 **All exclusions made by human.

5. Quality appraisal

An integrated review aims to provide the broadest research review (16). This review used the Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence-Based Practice (JHEBP) tool (19). The JHEBP tool can be used to assess the hierarchy and quality of an article, with a level 1 given to randomized control trials and systematic reviews of randomized control trials, a level 2 designated for quasi-experiments, a level 3 for non-experimental study, a level 4 for opinions from respected authorities or committees, and finally, a level 5 for quality improvement projects, narratives, or case reports.

6. Data abstraction

Data were retrieved, assessed, and tabulated by one reviewer. The articles were evaluated for the study design, aim, conclusions, and insights into family engagement and patient-family-centered care. Additional insights and comments were included. The investigation details are captured in narrative form in results and matrix form in Tables 1, 2.

This data abstraction and evaluation was approached using the Whittemore and Knafl methodology (16). This review of quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods research and narratives were assessed considering the pandemic-era hospital visiting policy on family engagement and patient-family-centered care for an older and seriously ill patient. Taking guidance from Whittemore and Knafl (16), the researcher extracted data, noting patterns and themes, common and unusual patterns, to build a description of family engagement in the hospital. Any questions that arose in the data abstraction process were discussed with all authors to reach a consensual decision.

7. Results

7.1. Diverse perspectives, designs, and sample population

The integrative review represents an international perspective, as captured in Table 2. Almost half of the twenty-eight studies illustrate the visiting policies in the United States. There are two Canadian studies and two Brazilian studies. There are three Italian studies and one study representing five countries with individuals who are literate in and speak German. There are two South Korean, one Japanese, and one Chinese territory, Hong Kong studies. Finally, there are studies from the United Arab Emirates, Iran, and Jordan that represent a Middle Eastern perspective. There are no African countries or Australian studies described in the literature.

The review includes diverse study designs, including quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-method designs. Seven studies include a survey in their design (12, 25, 27, 33, 36, 38, 46). The review includes randomized control trials (22, 41), retrospective comparative studies (20, 26, 31, 38, 43, 47), observational studies (29, 40), and a regression discontinuity and time to event design (24). There are qualitative studies with semi-structured interviews (21, 30, 45). There are two mixed-methods studies (27, 39), three narratives (23, 28, 42), an environmental scan (35) and an analysis on primary language availability of patient-facing policy (32).

The articles were critically appraised using the Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence-Based Practice (JHEBP) tool (19). The articles range from a rating of 1b to a 5b, with most articles falling in the 3b range. Two randomized control trials are rated 1b (22, 41), and a retrospective comparative study is rated 1c (20). Six articles are rated 5b (23, 28, 32, 35, 37, 42).

As well as having an international perspective and a diverse collection of study designs, this review provides a multidisciplinary perspective. The review presents the nursing, physician, health policy, and social work perspectives, to name a few. One-third of the articles are published in nursing journals. Another third of the articles are published in multidisciplinary journals. The remaining third are published in medical journals.

The review encompasses a large and diverse sample population. The perspective most captured is that of the patient. There are close to 7,000 patients included in the review. The second most substantial perspective is that of the provider. There are 1,174 multidisciplinary clinicians included in the review. Of the over one thousand clinicians, 780 are nurses, and 314 are physicians. One study does not share the number of clinicians (29). The review includes 96 hospitals, 50 comprehensive cancer centers, and one hospital unit. In addition, the review includes 257 policy documents.

7.2. Family engagement domains

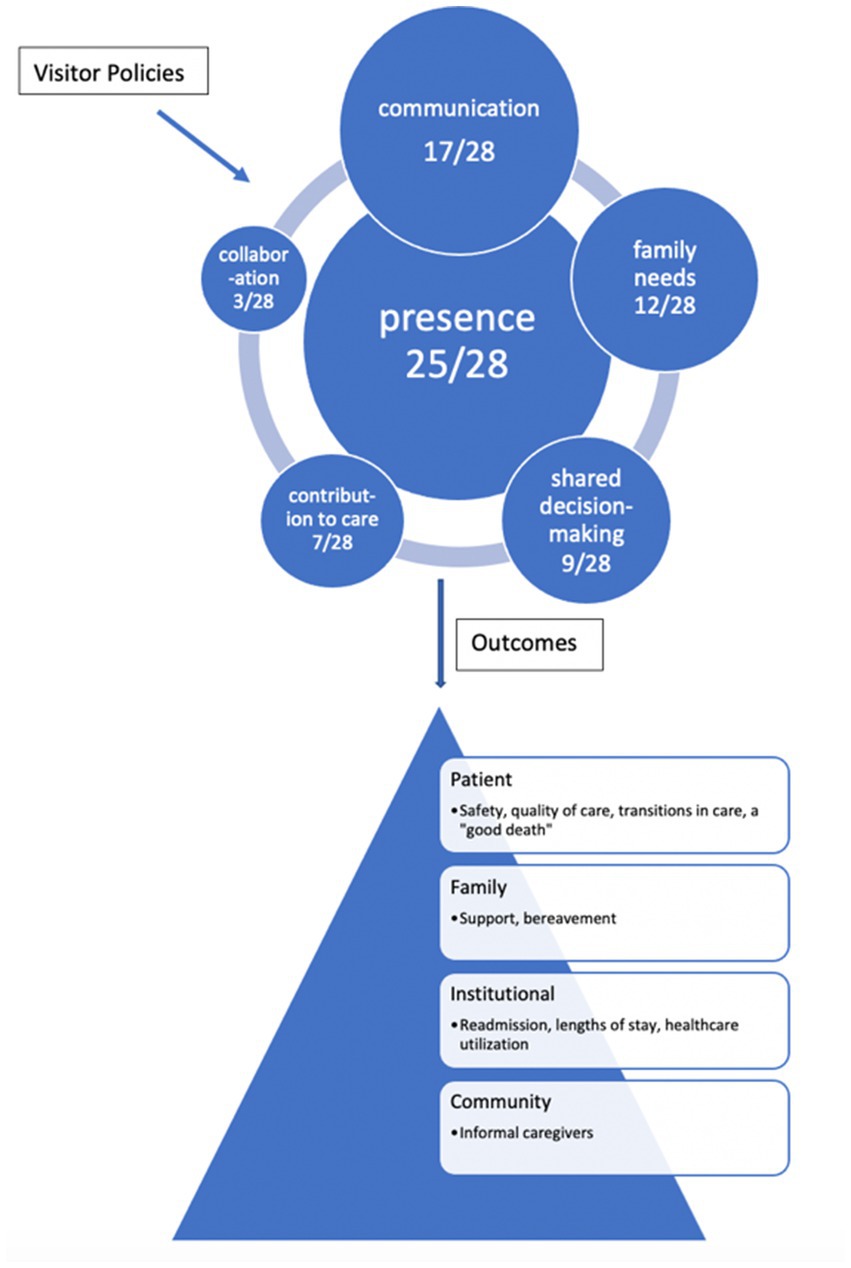

Assessing the articles on visiting policies for evidence of the domains of family engagement and patient-family-centered care reveals large variability between domains that the studies convey and those domains that studies do not. The most noticeable domains in the studies are presence, communication (information sharing), and shared decision-making (participation). Figure 2 illustrates the variability of the domains. Twenty-five of the twenty-eight, or 90%, articles on visiting policies connect visiting to the family engagement domain of presence. The family engagement domain of communication overlaps with the patient-family-centered care domain of information sharing. The next most prominent domain linked to visitor policies in 60% of the articles included in the review is communication or information sharing. Family engagement’s domain of family needs, like patient-family-centered care’s respect, is illustrated in a little less than half of the included articles.

Figure 2. The frequency and variability of the domains of family engagement within the visiting policy literature and the outcomes that are affected.

Family engagement’s shared decision-making, contribution to care, and collaboration are the more active and the least present domains in the review. The interplay of shared decision-making, participation, and restrictive visiting policies are characterized in nine studies, or 32% of the included articles. The most active domain of family engagement, contribution to care, which shares some of the same principles of family patient-centered care’s participation, is described in only a quarter of the articles. Patient-family-centered care’s collaboration of family at the institutional level in policies and programs is the most absent domain and only portrayed in three articles, or 10% of the articles.

The articles in the review of visitors’ policies, family engagement, and patient-family-centered care primarily focus on patient outcomes. A little more than half of the articles link the policy and domains to outcomes (12, 20, 22, 24, 26, 27, 31, 34, 36, 40–43, 46, 47). These articles add to the body of evidence that supports the benefits of family engagement. Five articles connect the policy and domains to patient and family satisfaction (12, 20, 22, 41, 46).

7.3. Question of equity of visiting policy

Some of the twenty-eight articles identify other confounding factors to visiting policy and family involvement. The idea of exceptions to the visiting policy was raised in seven articles (22, 23, 28, 35, 37, 39, 42). Choice architecture, the context in which family and patient decisions are influenced (Blumenthal-Barby and Opel, 2018) is described in two articles (23, 42). The review also identifies the need to focus on health equity in eight articles (23, 28–30, 32, 35, 42, 45).

8. Discussion

8.1. Insights gained from integrative review

The literature on post-Covid era visiting policy adds to what is known about the benefits of family engagement for the patient by focusing on physical and emotional outcomes. For example, family presence improves the patient experience and outcomes, decreases loneliness, anxiety, and distress and mitigates certain types of delirium, and improves patients’ orientation and decreases their agitation (26). 8/16/23 4:09:00 PM While they provide emotional support and comfort to the patient, families also are active agents in the early recognition of clinical deterioration and pain (31, 46). Presence also positively impacts family members (30, 33, 34, 42, 44). Finally, several studies encourage leveraging technology to create a family-patient connection with phone, email, or video contact when physical presence is impossible (20, 21, 35).

The literature reviewed herin also adds to the interconnectedness of the domains and the impact that restrictive policies may have on equitable and culturally appropriate competent care. It is difficult for providers to assess and meet the family’s needs when they have reduced interaction with their families (27). Furthermore, few restrictive visiting policies are culturally sensitive (25) and may not be equitable. For one, not all families have the same access to technology and, therefore, cannot engage in the technology that can facilitate presence (45). Restrictive visiting policies impact culturally appropriate decision-making for patients who are members of cultures that value communal decision-making and families (32). Additionally, families report not having enough information about their loved one’s condition and treatment plan (44) or having their preferences considered for discharge planning (46). At the end of a patient’s life, clinicians worry that they cannot provide a patient with a culturally appropriate death that respects the patient’s and family’s wishes (42).

The literature recognizes that communication between providers and families can be complex, and the post-Covid era visiting policies increase the complexity. In the best of circumstances, presence sets the stage for information sharing between the family and the providers facilitating communication and partnerships between the family and the providers. Clinicians share information, educating patients and families on conditions, treatments, and care after discharge. Family members provide valuable contextual information to providers (28). Additionally, when families can ask providers questions or observe rounding, their understanding and knowledge about the patient’s condition increases (33, 37, 44). Communication builds a family’s trust in the provider (23, 28, 30). Post-Covid technological adaptations to enable communication with families have altered the technological demands of nursing work (39). However, adopting new practices that encourage family participation, like facilitating and scheduling conference calls with families of patients, especially for families with language barriers, can be time-consuming for the nurse and other providers (28) and therefore are frequently not incorporated into the work-flow (25).

When families cannot be present because of restrictions or physical distance, the literature shares that technology may offer a solution, albeit not a perfect one. In the hospital, communication is fundamental to shared decision-making (7) and participation (9). Virtual family presence on rounds is encouraged when physical presence is impossible (21). The inability to have family bedside delays shared decision-making and may unnecessarily extend a patient’s stay in the intensive care unit (24, 42). However, the research is showing that providers need even more advanced communications education and training to establish a rapport and facilitate difficult conversations on a video platform (29, 34, 36) technology cannot wholly replicate in-person interaction, especially for serious illness and complex conversations (23).

Contribution to care and collaboration are poorly represented in the literature examining family engagement domains and visiting policy. These domains reflect the family as an active stakeholder in the patient’s care. Most clinicians report that their institutions do not have a family advisory group to help inform policies (26). Some of the effects of not having active partnerships with family can be seen in the literature. For example, even when the population most affected by Covid was the Latinx population; the online patient-facing visiting policy was only posted in English (28). In the clinical setting, patients and their families recommended that with the restricted visiting policies in place, providers should schedule more frequent family meetings with clinicians (44).

The literature also shows that family engagement is poorly operationalized. While literature adds more evidence to the benefits of family engagement, there are gaps in the description of family engagement in the hospital, how to operationalize it, and measure it. For example, while alternative methods of communication like phone or video can be used to update families on the patient’s condition and shared decision-making, few families report receiving telephone or video calls (33) even though the research encourages having a dedicated team member schedule and facilitate these conversations (35).

One of the consequences of not operationalizing family engagement is making exceptions to the visiting policy without systemization (28). Frontline workers are charged with enforcing the policy or making exceptions. Exceptions are made for patients at the end of their life, critical illness, or patients that require assistance for a cognitive or physical disability (35, 39). Unfortunately, the exceptions create choice architecture and are unfairly given (42). Exceptions affect the family’s trust in providers and the healthcare system (23). The exceptions also create conflict between the nurses who make exceptions and those who do not (37). Further evidence of the need to operationalize family engagement is the absence of a consistent proxy measure.

9. Limitations and strengths

There are limitations to this integrative review. First, the review covers a concise time frame from 2020 to 2023. Also, the visiting policies have undergone iterative changes within this time related to the uptake of vaccines and as more is learned about the virus. Additionally, the search process may not have captured everything to know. The Family Engagement Construct, while defined, includes many of the same concepts as the Patient-Family-Centered Construct, which may lead to some confusion and is behind the reason for combining the two. A final limitation is that one reviewer completed the review and assessment of the literature.

The review’s strengths lie in what we learn about family engagement in the hospital. The manuscript synthesizes the literature to reveal the foundational pieces that are most visible and strong in the hospital. It also identifies which domains could be strengthened. This review also reflects an international and multidisciplinary perspective of the care of seriously ill patients. Finally, this review is the first step toward operationalizing family engagement in the hospital setting, which could benefit all stakeholders.

10. Conclusion

This integrated review can guide practice, educational initiatives, and future research, for students, providers, and policy creators, by identifying the domains of family engagement and patient family-centered care related to the visiting policy. In practice, awareness of family engagement as a vehicle for improving outcomes is the first step to activating it. Presence which has been identified as one of the family engagement domains, may be the domain upon which all the others are built. It facilitates communication, family needs assessment, shared decision-making, and contribution to care. When presence is challenged by visiting policies or distance from family, nursing and other providers can leverage technology to mediate presence when it is impossible. Those who provide care can use the results of the review to activate family engagement domains that need support. Increasing awareness of the benefits of engagement helps create an institutional culture that recognizes the importance of encouraging and facilitating family engagement.

This review reveals opportunities for healthcare models and systems. The domain that offers the most significant opportunity for growth is collaborating with the stakeholders in the institutional policies. Collaboration is necessary to form partnerships between providers and families supporting the patient, family, community, and hospital. In the post-pandemic era, with capacity and workforce challenges, partnerships that reduce readmissions and healthcare utilizations become even more essential. Hospital policy creators can use the results of the review to guide policy creation that supports all the domains of family engagement.

Finally, further research on family engagement in the hospital setting is needed to operationalize family engagement. Describing the extent to which all the domains are seen within the hospital setting and identifying proxies to measure the domains would help test the effectiveness of family engagement interventions. Also, more information is needed to explore if institutional policies, like visiting policies, disproportionately burden specific populations, thereby increasing health disparities. Finally, research is required to explore the role that unmet social determinants of health may play in the ability of families to engage with a hospital patient.

Author contributions

JM conceptualized, performed data abstraction and analysis, and wrote the manuscript. PG guided the review process, edited the manuscript, and provided guidance on figures and tables. LH helped guide the review process and gave manuscript edits. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [AHRQ] (2022). "Engaging patients and families in their health care." October 2022. Available at: https://www.ahrq.gov/patient-safety/patients-families/index.html.

2. Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2021). "Person and family engagement | CMS." December 1, 2021. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/QualityInitiativesGenInfo/Person-and-Family-Engagement.

3. Morgan, J, and Gazarian, P. A good death: A synthesis review of concept analyses studies. Collegian. (2022) 30:236–46. doi: 10.1016/j.colegn.2022.08.006

4. Aronson, PL, Yau, J, Helfaer, MA, and Morrison, W. Impact of family presence during pediatric intensive care unit rounds on the family and medical team. Pediatrics. (2009) 124:1119–25. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0369

5. Rodakowski, J, Rocco, PB, Ortiz, M, Folb, B, Schulz, R, Morton, SC, et al. Caregiver integration during discharge planning for older adults to reduce resource use: A Metaanalysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2017) 65:1748–55. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14873

6. Herrin, J, Harris, KG, Kenward, K, Hines, S, Joshi, MS, and Frosch, DL. Patient and family engagement: A survey of US Hospital practices. BMJ Qual Safety. (2016) 25:182–9. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004006

7. Olding, M, McMillan, SE, Reeves, S, Schmitt, MH, Puntillo, K, and Kitto, S. Patient and family involvement in adult critical and intensive care settings: A scoping review. Health Expect. (2016) 19:1183–202. doi: 10.1111/hex.12402

8. Gitlin, LN, and Wolff, J. Family involvement in care transitions of older adults: what do we know and where do we go from Here? Annu Rev Gerontol Geriatr. (2012) 31:31–64. doi: 10.1891/0198-8794.31.31

9. Johnson, B, Abraham, M, Conway, J, Simmons, L, Edgman-Levitan, S, Sodomka, P, et al. Partnering with patients and families to design a patient- and family-centered health care system. Bethesda, MD: Institute for Patient and Family-Centered Care (2008).

10. May, Steven. (2020). "Caregiving in the US 2020 | the National Alliance for caregiving." May 11, 2020. Available at: https://www.caregiving.org/caregiving-in-the-us-2020/.

11. Carol, Brooks Ball. (2017). "The CARE act is now law in Massachusetts: learn what this means for you." Massachusetts December 3, 2017. Available at: https://states.aarp.org/massachusetts/care-act-now-law-massachusetts-learn-means.

12. World Social Report (2023): Leaving no one behind in an ageing world. 2023. World social report 2023. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Available at: https://social.desa.un.org/publications/undesa-world-social-report-2023.

13. Cohen, SM, Volandes, AE, Shaffer, ML, Hanson, LC, Habtemariam, D, and Mitchell, SL. Concordance between proxy level of care preference and advance directives among nursing home residents with advanced dementia: A cluster randomized clinical trial. J Pain Symptom Manag. (2019) 57:37–46.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.09.018

14. Pedersen, DE, Minnotte, KL, and Ruthig, JC. Challenges of using secondary data to study rural caregiving within the United States. Sociol Inq. (2020) 90:955–70. doi: 10.1111/soin.12364

15. World Health Organization. (2020). Maintaining essential health services: operational guidance for the COVID-19 context: interim guidance, 1 June 2020. WHO/2019-nCoV/essential_health_services/2020.2. World Health Organization. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/332240.

16. Whittemore, R, and Knafl, K. The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs. (2005) 52:546–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x

17. Fawcett, J, and Russell, G. A conceptual model of nursing and health policy. Policy Polit Nurs Pract. (2001) 2:108–16. doi: 10.1177/152715440100200205

18. Page, MJ, McKenzie, JE, Bossuyt, PM, Boutron, I, Hoffmann, TC, Mulrow, CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. (2021) 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

19. Dang, D, Dearholt, SL, Bissett, K, Whalen, M, and Ascenzi, J. Johns Hopkins evidence-based practice for nurses and healthcare professionals: model & guidelines. Fourth ed. Indianapolis: Sigma Theta Tau International (2021).

20. El Aziz, A, Mohamed, A, Calini, G, Abdalla, S, Saeed, HA, Lovely, JK, et al. Acute social isolation and postoperative surgical outcomes. Lessons learned from COVID-19 pandemic. Minerva Surgery. (2022) 77:348–53. doi: 10.23736/S2724-5691.21.09243-1

21. Ahmed, FR, Dias, JM, Al Yateem, N, Subu, MA, and Ruz, MA. Lessons learned and recommendations from the COVID-19 pandemic: content analysis of semi-structured interviews with intensive care unit nurse managers in the United Arab Emirates. J Nurs Manag. (2022) 30:2479–87. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13677

22. Akbari, R, Moonaghi, HK, Mazloum, SR, and Moghaddam, AB. Implementation of a flexible visiting policy in intensive care unit: A randomized clinical trial. Nurs Crit Care. (2020) 25:221–8. doi: 10.1111/nicc.12499

23. Azad, TD. Opinion & Special Articles: shared decision-making during the COVID-19 pandemic: three bullets in 3 hemispheres. Neurology. (2021) 96:e2558–60. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000011811

24. Azad, TD, Al-Kawaz, MN, Turnbull, AE, and Rivera-Lara, L. Coronavirus disease 2019 policy restricting family presence May have delayed end-of-life decisions for critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. (2021) 49:e1037–9. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000005044

25. Brauchle, M, Nydahl, P, Pregartner, G, Hoffmann, M, and Jeitziner, M-M. Practice of family-Centred Care in Intensive Care Units before the COVID-19-pandemic: A cross-sectional analysis in German-speaking countries. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. (2022) 68:103139. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2021.103139

26. Brown, RT, Shultz, K, Karlawish, J, Zhou, Y, Xie, D, and Ryskina, KL. Benzodiazepine and antipsychotic use among hospitalized older adults before versus after restricting visitation: march to May 2020. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2022) 70:2988–95. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17947

27. Chan, WC, Ho, RK, Woo, W, Kwok, DK-S, Clare Tsz Kiu, Y, and Chiu, LM-H. Impact of COVID-19 on mental health of palliative care professionals and services: A mixed-methods survey study. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. (2022) 39:1227–35. doi: 10.1177/10499091211057043

28. Chary, AN, Naik, AD, and Kennedy, M. Visitor policies and health equity in emergency Care of Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2022) 70:376–8. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17392

29. Chua, IS, Jackson, V, and Kamdar, M. Webside manner during the COVID-19 pandemic: maintaining human connection during virtual visits. J Palliat Med. (2020) 23:1507–9. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2020.0298

30. Creutzfeldt, CJ, Schutz, REC, Zahuranec, DB, Lutz, BJ, Randall Curtis, J, and Engelberg, RA. Family presence for patients with severe acute brain injury and the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic. J Palliat Med. (2021) 24:743–6. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2020.0520

31. Danielis, M, Iob, R, Achil, I, and Palese, A. Family visiting restrictions and postoperative clinical outcomes: A retrospective analysis. Nurs Rep. (2022) 12:583–8. doi: 10.3390/nursrep12030057

32. Dhawan, N, Subbiah, IM, Yeh, JC, Thompson, B, Hildner, Z, Jawed, A, et al. Healthcare disparities and the COVID-19 pandemic: analysis of primary language and translations of visitor policies at NCI-Designated Comprehensive Cancer centers. J Pain Symptom Manag. (2021) 61:e13–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.01.140

33. Eden, C, and Fowler, SB. Family perceptions related to isolation during COVID-19 hospitalization. Nursing. (2021) 51:56–60. doi: 10.1097/01.NURSE.0000757160.34741.37

34. Eugênio, CS, da Silva, T, Haack, R, Teixeira, C, Rosa, RG, Nogueira, E, et al. Comparison between the perceptions of family members and health professionals regarding a flexible visitation model in an adult intensive care unit: A cross-sectional study. Revista Brasileira de Terapia Intensiva. (2022) 34:374–9. doi: 10.5935/0103-507X.20220114-pt

35. Fiest, KM, Krewulak, KD, Hiploylee, C, Bagshaw, SM, Burns, KEA, Cook, DJ, et al. An environmental scan of visitation policies in Canadian intensive care units during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Canadian J Anaesthesia. (2021) 68:1474–84. doi: 10.1007/s12630-021-02049-4

36. Fino, E, Fino, V, Bonfrate, I, Russo, PM, and Mazzetti, M. Helping patients connect remotely with their loved ones modulates distress in healthcare workers: A tend-and-befriend hypothesis for COVID-19 front liners. Eur J Psychotraumatol. (2021) 12:1968141. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2021.1968141

37. Kean, L, and Milner, KA. Implementation of open visitation in an adult intensive care unit: an evidence-based practice quality improvement project. Crit Care Nurse. (2020) 40:76–9. doi: 10.4037/ccn2020661

38. Maloh, HI, Abu, A, Jarrah, S, Al-Yateem, N, Ahmed, FR, and AbuRuz, ME. Open visitation policy in intensive care units in Jordan: cross-sectional study of Nurses' perceptions. BMC Nurs. (2022) 21:336–8. doi: 10.1186/s12912-022-01116-5

39. Marmo, S, and Milner, KA. From open to closed: COVID-19 restrictions on previously unrestricted visitation policies in adult intensive care units. Am J Crit Care. (2023) 32:31–41. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2023365

40. Padua, L, Fredda, G, Coraci, D, Reale, G, Glorioso, D, Loreti, C, et al. COVID-19 and hospital restrictions: physical disconnection and digital re-connection in disorders of consciousness. Brain Inj. (2021) 35:1134–42. doi: 10.1080/02699052.2021.1972335

41. Rosa, RG, Pellegrini, JAS, Moraes, RB, Prieb, RGG, Sganzerla, D, Schneider, D, et al. Mechanism of a flexible ICU visiting policy for anxiety symptoms among family members in Brazil: A path mediation analysis in a cluster-randomized clinical trial. Crit Care Med. (2021) 49:1504–12. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000005037

42. Segar, NO. As hospitals restrict visitors, what constitutes A 'Good Death'? Health Aff. (2022) 41:921–4. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01857

43. Shinohara, F, Unoki, T, and Horikawa, M. Relationship between no-visitation policy and the development of delirium in patients admitted to the intensive care unit. PLoS One. (2022) 17:e0265082. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0265082

44. Suh, J, Na, S, Jung, S, Kim, KH, Choo, S, Choi, JY, et al. Family Caregivers' responses to a visitation restriction policy at a Korean surgical intensive care unit before and during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Heart Lung. (2023) 57:59–64. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2022.08.015

45. Wasilewski, MB, Szigeti, Z, Sheppard, CL, Minezes, J, Hitzig, SL, Mayo, AL, et al. Infection prevention and control across the continuum of COVID-19 care: A qualitative study of Patients', Caregivers' and Providers' experiences. Health Expect. (2022) 25:2431–9. doi: 10.1111/hex.13558

46. Zeh, RD, Santry, HP, Monsour, C, Sumski, AA, Bridges, JFP, Tsung, A, et al. Impact of visitor restriction rules on the postoperative experience of COVID-19 negative patients undergoing surgery. Surgery. (2020) 168:770–6. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2020.08.010

Keywords: family engagement, informal caregiver, integrative review, patient-family centered care, hospital visitor policy

Citation: Morgan JD, Gazarian P and Hayman LL (2023) An integrated review: connecting Covid-era hospital visiting policies to family engagement. Front. Public Health. 11:1249013. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1249013

Edited by:

Efrén Murillo-Zamora, Mexican Social Security Institute (IMSS), MexicoReviewed by:

Polychronis Voultsos, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, GreeceEmily Gadbois, Brown University, United States

Copyright © 2023 Morgan, Gazarian and Hayman. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jennifer D. Morgan, amVubmlmZXIubW9yZ2FuMDAyQHVtYi5lZHU=

Jennifer D. Morgan

Jennifer D. Morgan Priscilla Gazarian

Priscilla Gazarian Laura L. Hayman

Laura L. Hayman