- 1School of Public Health, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China

- 2Hongqiao International Institute of Medicine, Tongren Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong Univeristy School of Medicine, Shanghai, China

Background: Little is known about the mediating mechanisms underlying the association between work stress and mental health, especially among primary public health workers (PHWs). We aimed to evaluated the association between work stress and mental health among PHWs, and explore the mediating roles of social support and self-efficacy.

Methods: A large-scale cross-sectional survey was conducted among 3,809 PHWs from all 249 community health centers in 16 administrative districts throughout Shanghai, China. Pearson correlation and hierarchical linear regression were used to explore the associations among work stress, social support, self-efficacy and mental health. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was conducted to examine the mediation effects.

Results: The prevalence of depression and anxiety symptoms among primary PHWs was 67.3 and 55.5%, respectively. There is a significant positive direct effect of work stress on mental health (β = 0.325, p < 0.001). Social support and self-efficacy partially mediated the relationship between work stress and mental health, respectively. Meanwhile, the chained mediating effects of social support and self-efficacy also buffered the predictive effects of work stress on anxiety and depression symptoms (β = 0.372, p < 0.001).

Conclusion: Work stress has significant direct and indirect effects on mental health among primary PHWs. Enhancing social support and self-efficacy may be effective psychological interventions to mitigate the effects of work-related stress on mental health. These findings highlight the severity of mental health problems among primary public health workers and provide new evidence for early prevention and effective intervention strategies.

Introduction

From early 2020 to the current time, the COVID-19 pandemic has affected many countries and regions and declared by the World Health Organization to be a public health emergency of international concern. Shanghai, one of the largest cities in Asia, experienced another unprecedented pandemic and associated lockdown in March 2022, which contributed to serious mental health problems (1). During the continuing COVID-19 pandemic, medical staff in hospitals and primary public health workers (PHWs) in community healthcare center (CHCs) faced increased workload and stress, resulting in adverse mental health conditions (2–4). Therefore, it is one of the main challenges of the pandemic to reduce the damage caused by COVID-19 to the mental health of healthcare workers. However, studies to date have focused on evaluating the mental health impact of COVID-19 related work stress on the various type of medical staff (5–7), with limited attention to primary public health workers. Furthermore, the neglect of primary public health workers may result in the accumulation of psychosocial problems caused by long-term, heavy work stress, potentially leading to a range of adverse psychosocial outcomes and harm to the primary healthcare system. Therefore, it is necessary to understand its harmful pathways and potential mechanisms on psychological health in order to take effective measures to prevent and reduce the risk of mental health problems, such as depression and anxiety symptoms, caused by work-related stress.

Work stress during COVID-19 and mental health

Work stress on primary public health workers has increased mainly from the need that in addition to providing basic health services, public health physicians and medical technicians are required to perform routine nucleic acid testing, mass vaccinations, epidemiological investigations and surveillance, general practitioners and nurses are responsible for community fever clinic services, and administrators and other staff perform health promotion and education and other preventive and control measures to prevent the spread of COVID-19 in the community. Work stress can be quantified based on the classic theory of Effort-Reward Imbalance (ERI) which assesses the intense stress response induced by the imbalance between the effort and the reward of work (8). In the context of COVID-19, there is evidence that work stress is strongly associated with negative mental health outcomes among healthcare workers. Prolonged, intense work stress can directly contribute to the development of anxiety and depression disorders (9). Moreover, previous studies have confirmed that the beneficial predictive effect of ERI on increasing the risk of mental health problems and other adverse health outcomes (10, 11).

Mental health problems of PHWs in community, in addition to health care workers in hospital, is also a crucial part of public health event (12). An epidemiological survey of community epidemic prevention workers revealed that a considerable proportion of participants reported depression (39.7%) and anxiety (29.5%) symptoms (13). Anxiety and depression are common mental health problems (with high prevalence) among health care workers caused by the high-intensity work environment during the COVID-19 epidemic (2, 3, 14, 15). Although previous studies have provided preliminary evidence that work stress may be a significant predictor of mental health among medical staff or healthcare workers, there is limited research on the association between work stress and mental health problems among primary PHWs. Thus, there is a stronger need to further focus on mediating factors and explore potential pathways between work stress and depression and anxiety in order to provide effective interventions for reducing the mental health issues risks of primary PHWs.

Social support and self-efficacy as mediators

Social support is a crucial interpersonal resource that encompasses mainly the close relationship between individuals and various aspects of society, such as friends, family and significant others. Based on stress buffering theory (16, 17), social support has a buffering effect on the relationship between work stress and mental health problems, which is also confirmed in healthcare workers (18, 19). Besides the external source and environment from social support, self-efficacy is an important internal aspect. Self-efficacy, which reflects individuals’ subjective evaluation of their own abilities, is considered an important personal trait with significant impact on coping with work stress and alleviating mental health problems (20, 21).

In addition, some studies have found that social support is an important source of self-efficacy, and the more social support someone receives, the more encouragement and affirmation they receive, which further enhances their self-efficacy (22–24). In contrast, when an individual perceives a lack of social support, this negative perspective on social relationships can lead to decrease in self-efficacy. This pathway proposed above bridges the gap between the external environment and personal factors. Notably, the mediating roles of social support and self-efficacy between job stress and mental health problems were also not confirmed in primary PHWs.

Present study

Due to the limited epidemiological evidence for primary public health workers and the severity of public health challenges, we conducted a large-scale cross-sectional study of PHWs to explore the relationship between work stress, social support, self-efficacy, and mental health. Based on the theoretical model and previous related studies, we constructed a chain mediation model to confirm the following hypotheses: Hypothesis 1. Work stress can directly predict mental health. Hypothesis 2. Social support can mediate the association between work stress and mental health. Hypothesis 3. Self-efficacy can mediate the association between work stress and mental health. Hypothesis 4. Social support and self-efficacy are sequential mediators in the association between work stress and mental health (Supplementary Figure S1).

Methods

Participants

We performed a large-scale questionnaire survey among primary public health workers, covering all 249 community health service centers across all 16 districts throughout Shanghai. This study was conducted with the support of the Shanghai Municipal Health Commission and the cooperation of the leadership and administrative team of each CHC. The primary goal was to improve the capacity of primary care public health services and construction. From October to November 2022, this cross-sectional study was conducted via an online survey platform (“SurveyStar,” Changsha Ranxing Science and Technology, Shanghai, China). In order to ensure the accuracy and validity of the data, all questionnaires were set up in the computer system with intelligent logical checks to identify and reject invalid responses. The collected data were subsequently desensitized by specialists for statistical analysis. All respondents were invited to complete a self-assessment questionnaire through mobile phones, which included demographic information, lifestyle, work factors and psychological factors. A total of 3,937 respondents completed the questionnaire, and of whom 128 were excluded due to unwilling to engage in this survey. Finally, 3,809 valid questionnaires were collected, with the efficiency response rate of 96.75%. All participants were the target population and were informed of the significance and value of this anonymous survey before accessing the link to complete the questionnaire, and were then asked to read and sign an electronic informed consent form. This study was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of School of Public Health, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (approval number: SJUPN-202108) and adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Measures

General information

This survey contents included demographic variables (gender, age, educational level, marital status, hometown type), lifestyle characteristic (cigarette smoking, alcohol drinking, physical activity, sleep duration), occupation-related variables (type of occupation, professional title grade, years of working, length of public health service, daily working time, work overtime status, cumulative time involved in front-line prevention during the COVID-19 pandemic).

Work stress

Work stress was assessed by the Chinese version of the effort-reward imbalance (ERI) scale (25), which had good validity and reliability in Chinese medical staff (26, 27). The ERI scale contains 16-item of job effort (5 items, Cronbach’s =0.90) and job reward (11 items, Cronbach’s =0.82). All items were scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). ERI was measured by the effort-reward ratio calculated according to the formula: (effort total score) / [(reward total score) * (correction factor)], where the correction factor (5/11) considering the different number of items investigating job effort and reward (28). In this study, Cronbach’s alpha value of the ERI scale was 0.87.

Social support

The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived social support (MSPSS) was used to measure the levels of social support. It consists of three dimensions of support from family, friends, and others, with a total of 12 items. Each item of MSPSS is rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from one point (strongly disagree) to seven point (strongly agree). The total MSPSS score is based on the sum of three subscale ranging from 12 to 84, with higher scores representing higher levels of perceived social support (29). The reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the MSPSS have been demonstrated in different surveys (5, 30). In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.98.

Self-efficacy

Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale (GSES) was developed to assess the level of self-efficacy through psychological states and behaviors that individuals might display when dealing with difficulties or setbacks. The Chinese version of this scale has been widely used among the Chinese population (31). This revised scale consists of 10 items, using 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (not at all true) and 4 (exactly true). The total scores range from 10 to 40, with higher scores reflecting a stronger sense of self-efficacy. Previous studies showed that the revised GSES scale has good reliability, validity (32). The Cronbach’s in the current study was 0.94.

Anxiety

The General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) is widely used to measure the severity of anxiety symptoms in the Chinese population (33). The GAD-7 consists of seven items, and each item is rated on 4-point Likert-type scales (0 = “not at all,” 1 = “a few days,” 2 = “more than half the days,” 3 = “almost every day”), summing to obtain a total score to measure the severity of anxiety symptoms. The higher the score, the more severe the anxiety. Participants with a total score of 0 to 4 were assessed as “normal mood,” 5 to 9 were assessed as “mild anxiety symptoms,” while scores above 10 or 15 represent moderate or severe anxiety, respectively (34). In this study, the Cronbach’s of the scale was 0.97.

Depression

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 Items (PHQ-9). The PHQ-9 is an internationally used depressive symptom assessment scale that contains 9 items to assess the severity of depressive symptoms (35). The degree of depressive symptoms is based on the four answers ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day), with the total score range from 0 to 27. Higher scores indicate higher levels of depression (0–4 = no depression, 5–9 = mild depression, 10–14 = moderate depression, 15–19 = severe depression, ≥20 = extremely severe depression) (36). Excellent validity and reliability for the PHQ-9 scale have been showed in Chinese hospital workers (37), and the current study showing a Cronbach α of 0.94 for depression.

Statistical analysis

This study conducted descriptive analyses using frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and means ± standard deviations (SD) for continuous variables. Independent samples t-test and one-way ANOVA were used to compare differences in anxiety and depression scores across variable subgroups. The correlations between the main continuous variables (depression, anxiety, social support, self-efficacy, and ERI) were analyzed initially using the Pearson correlation method. Hierarchical multiple linear regression analysis was used to further explore the differential predictive effects of work stress on anxiety and depressive symptoms beyond social support and self-efficacy. The continuous anxiety and depression variables were considered as dependent variables, and demographic variables, lifestyle and COIVD-19-related and other work variables, work stress, social support and self-efficacy were controlled for in stepwise regression models 1–3, respectively. Before the mediation model analysis, the Harman’s single-factor test was conducted to examine the presence of common method bias in work stress, social support, self-efficacy, anxiety, and depression. It is generally considered that a variance of more than 40% for the first common factor indicated the presence of a common method bias (38, 39). Multiple mediation model analyses were conducted to examine the relationship between work stress, social support, self-efficacy, and mental health (depression and anxiety symptoms) using the maximum likelihood method. A bias-corrected bootstrap method (5,000 replicates) was applied to compute direct and indirect effects and 95% corrected confidence intervals (40). All statistical analyses were conducted using Mplus (version 8.4) and SPSS software (version 25.0). A two-tailed value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

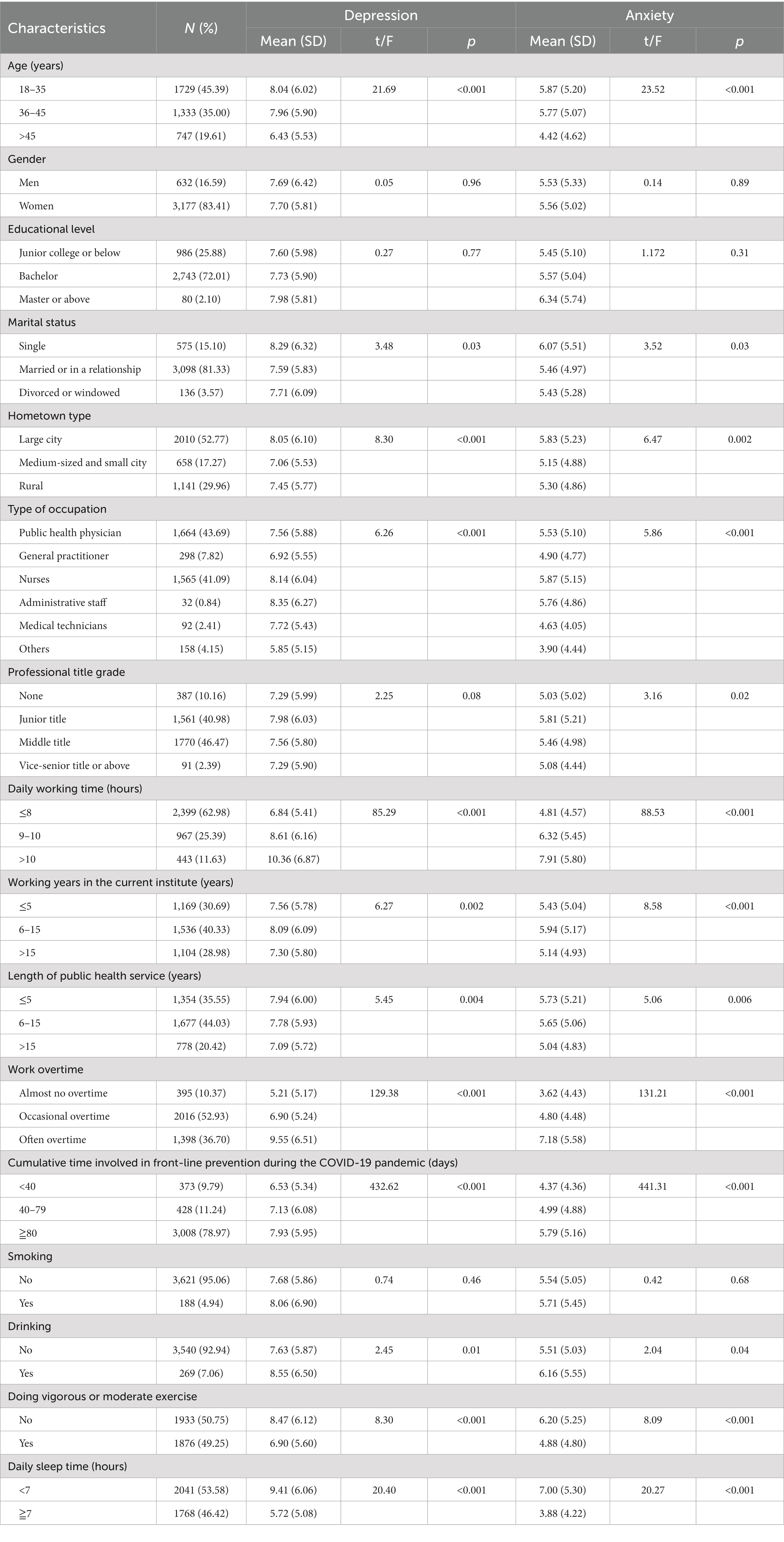

Characteristic of participants

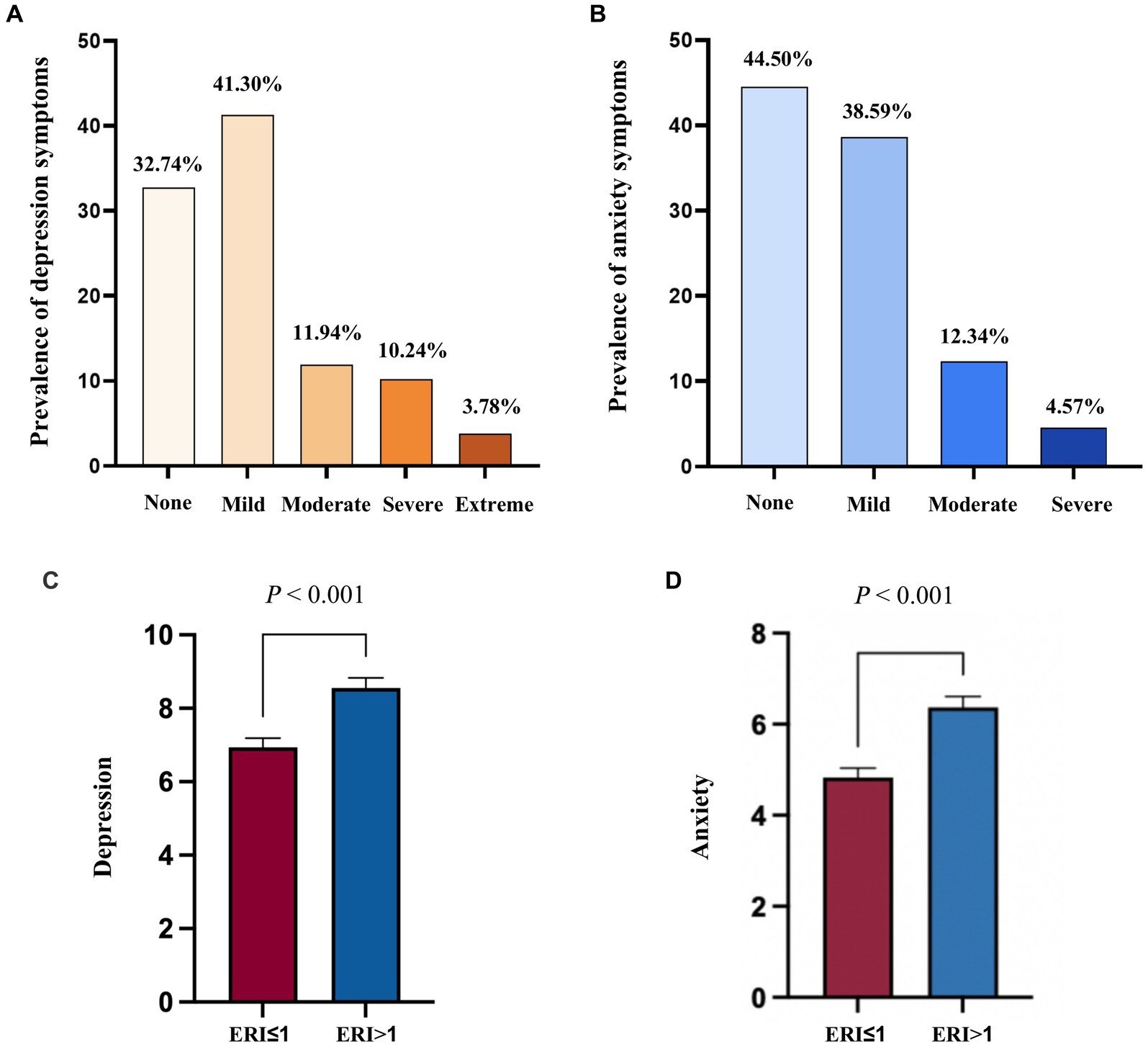

Among the 3,809 PHWs, the number and percentage of public health physicians, general practitioners, nurses, administrative staff, medical technicians and other staff were 1,664 (43.69%), 298 (7.82%), 1,565 (41.09%), 32 (0.84%), 92 (2.41%) and 158 (4.15%), respectively. The prevalence of “no depression,” “mild depression,” “moderate depression,” “severe depression” and “extremely severe depression” among all participants were 32.74%, 41.30%, 11.94%, 10.24% and 3.78%, respectively. Furthermore, 44.50% of public health workers had no anxiety symptoms, while 55.50% had different degrees of anxiety symptoms, including 38.59% with “mild anxiety,” 12.34% with “moderate anxiety,” and 4.57% with “severe anxiety” (Figure 1). The differences of anxiety and depression symptom scores among participants across general characteristics were shown in Table 1. In addition, PHW with work stress had significantly higher anxiety (t = 9.46; p < 0.001) and depression scores (t = 8.53; p < 0.001) than those without work stress (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Distribution and differences in work stress and mental health problems among primary public health workers (A) Prevalence of depression symptom among primary public health workers; (B) Prevalence of anxiety symptom among primary public health workers; (C) Difference in depression symptom among primary public health workers with and without work stress; (D) Difference in anxiety symptom among primary public health workers with and without work stress; p calculated by t-test analysis.

Table 1. Comparison of characteristics of anxiety and depression scores among public health workers (N = 3,809).

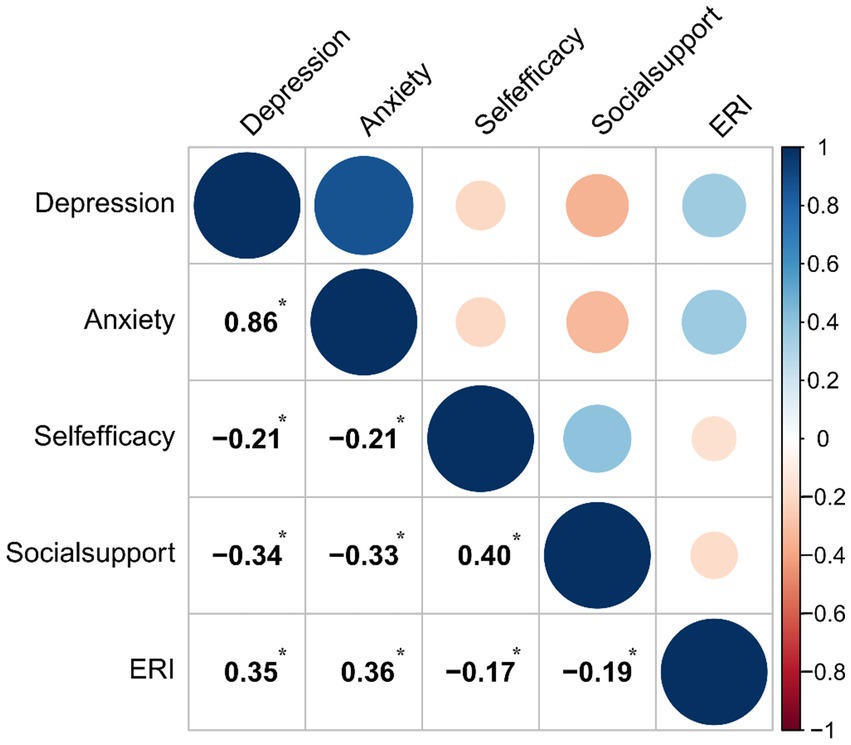

Correlation between Key variables

Figure 2 presented the correlation matrix for key study variables. The Pearson correlation analysis showed that ERI was positively correlated with depression (r = 0.35, p < 0.001) and anxiety (r = 0.36, p < 0.001), but negatively related with social support (r = −0.19, p < 0.001) and self-efficacy (r = −0.17, p < 0.001). Depression was negatively and significant correlated with social support (r = −0.34, p < 0.001) and self-efficacy (r = −0.21, p < 0.001). This significantly negative correlations were also observed between anxiety and social support and self-efficacy (p < 0.001). The validity of Hypothesis 1 was confirmed by the results of the correlation analysis.

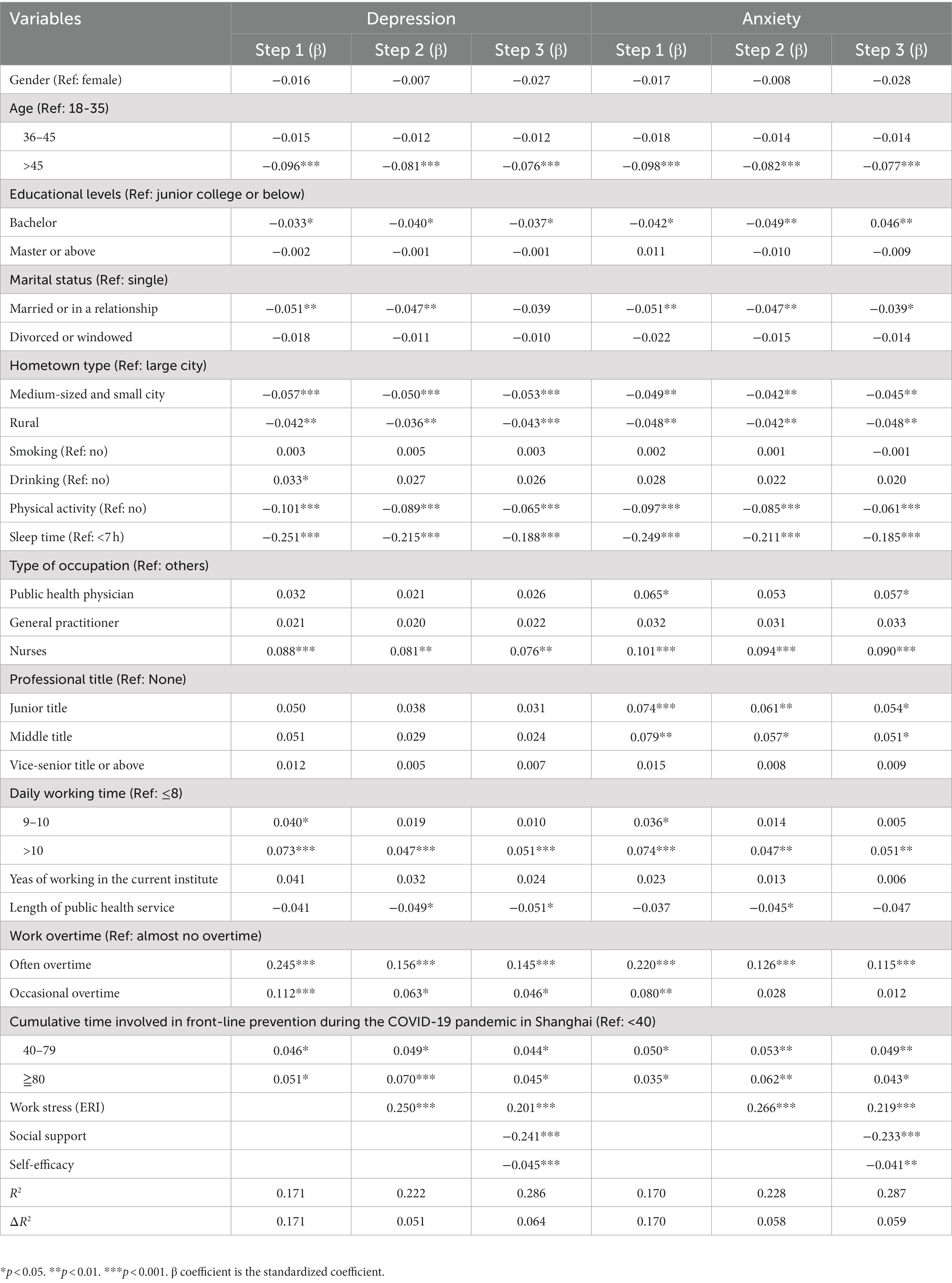

Hierarchical multiple regression analysis

In the first step, demographic variables, lifestyle and COIVD-19-related and other work variables accounted for 17.0% and 17.1% of the variance in anxiety and depression symptoms, respectively (Table 2). In a second step, work stress was introduced into the model and was positively associated with anxiety and depressive symptoms, explaining 5.8% and 5.1% of the variance, respectively (standardized β=0.266, p < 0.001 and standardized β = 0.250, p < 0.001). The relationship between work stress and anxiety and depressive symptoms remained significant when social support and self-efficacy were finally added to the model, explaining 5.9% and 6.4% of the variance in anxiety and depression, respectively. The results of the above hierarchical multiple regressions also provided the basis and theoretical support for the complex relationships constructed by the structural equation model.

Mediating effect analysis

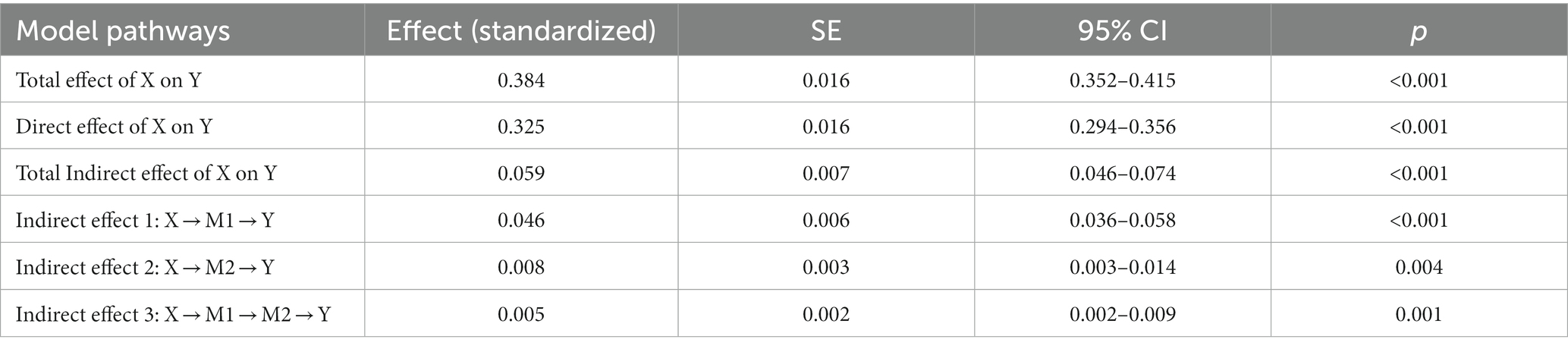

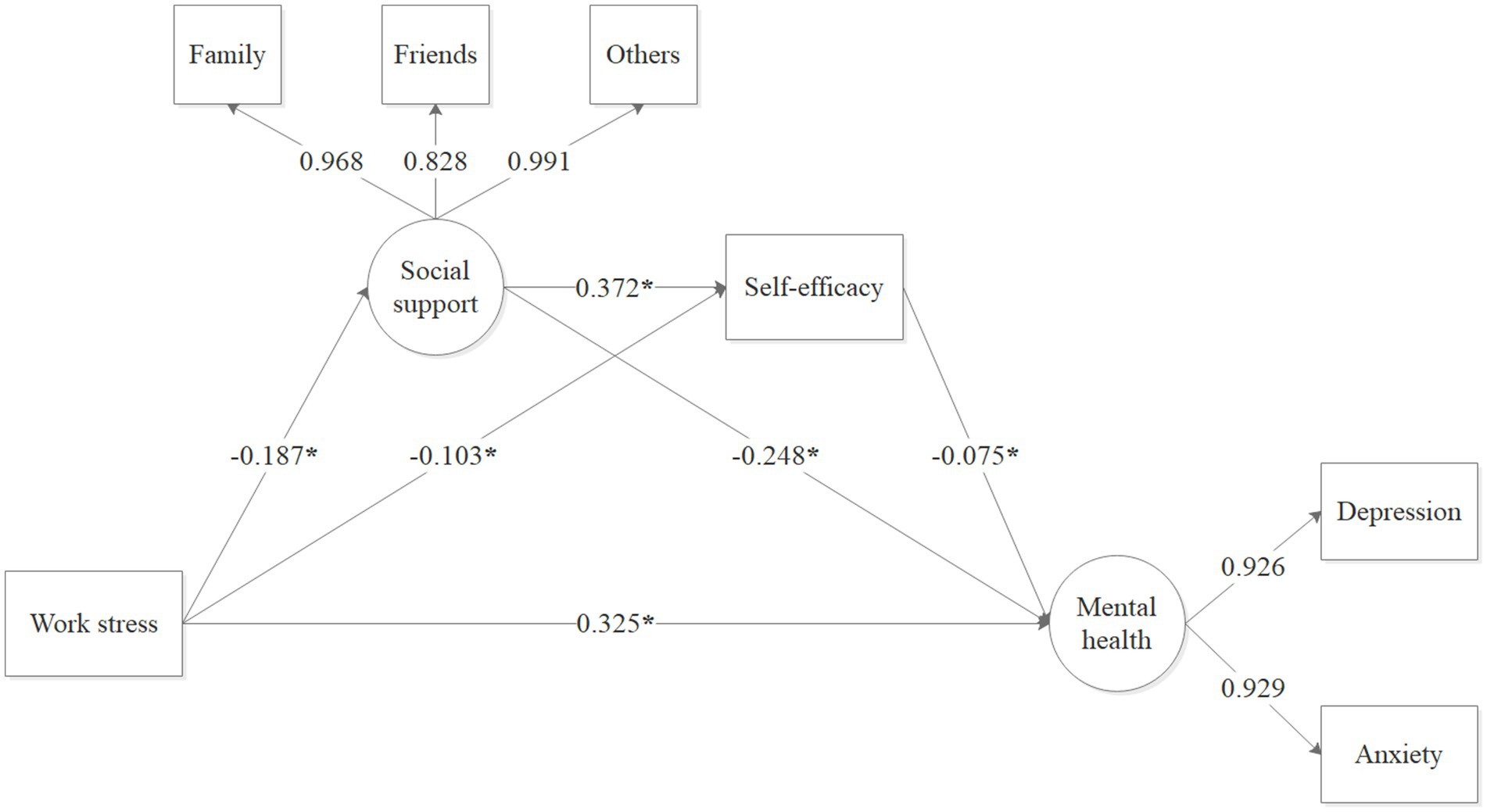

The results showed that five factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, and the first factor explained 32.40% of the variance (less than 40%). Therefore, it may be deduced that the variables involved in this study do not have significant common method bias. The results of mediation pathway model in the association between work stress and mental health were shown in Table 3 and Figure 3. All path coefficients, including direct and indirect effects, between work stress and mental health were statistically significant (p < 0.001, bias-corrected 95% confidence interval not including 0). The standardized direct effect of work stress on depression and anxiety was 0.325 (p < 0.001). The results indicated that work stress had a significant negative effect on social support (β = −0.187, p < 0.001) and self-efficacy (β = −0.103, p < 0.001). In addition, social support (β = −0.248, p < 0.001) and self-efficacy (β = −0.075, p < 0.001) had a significant negative influence on depression and anxiety. Notably, social support was positively associated with self-efficacy (β = 0.372, p < 0.001). The chain mediating effect model were acceptable according to the model fit index (model fit: χ2/df = 2.98 < 3 (p < 0.001), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) = 0.982, comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.991, standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) = 0.026 and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.068 (p < 0.001)).

Table 3. Direct, indirect, and total effects of the chain mediation model between work stress and mental health problems.

Figure 3. The mediating role of social support and self-efficacy in the relationship between work stress and mental health problems. *p < 0.001.

Discussion

Currently, there are limited epidemiological evidence on the association between work stress and mental health among primary public health workers. Overall, the prevalence of work stress and mental health problems (i.e., depression and anxiety) among community PHWs was 67.3 and 55.5%, respectively. The prevalence of mental health problems in our study was significantly higher than the combined prevalence of general healthcare workers reported in several meta-analyses during the COVID-19 pandemic (14, 41–43), which also emphasized the importance of focusing on the mental health for primary PHWs. Consistent with previous hypotheses, the current study showed that work stress had direct and indirect effects on depression and anxiety in primary PHWs. Furthermore, the mediating effect of social support and self-efficacy buffered the positive predictive effects of work stress on depression and anxiety. Exploring the underlying mechanisms and pathways between work stress and mental health, and identifying risk factors after a major public health event, is beneficial in preventing the occurrence and progression of mental health problems in primary PHWs.

As assumed, work stress was found to be directly associated with depression and anxiety among community PHWs, which supported and expanded the previous findings on occupational mental health among primary healthcare workers or medical staff. For example, a cross-sectional study conducted in Brazil found a significant positive relationship between ERI and common mental disorders among healthcare workers (44). Similar results were found for the significant positive effects of work stress on anxiety and depression among Chinese healthcare workers and medical staff (45, 46). Therefore, future research should pay more attention to the work and psychosocial situation of primary PHWs. Meanwhile, the related institutions are recommended to adopt positive coping strategies, such as improving job benefits, providing solid job security and continuous mental health services, to prevent and alleviate mental health problems caused by work stress (47).

As predicted, social support played a significant mediating role in the association between work stress and mental health among community PHWs, which explained 12.0% of the effect of work stress on anxiety and depression. This significant direct effect is consistent with the previous studies conducted with medical staff and primary healthcare workers (19, 45, 48). Individuals with higher levels of social support tended to experience professional achievement and increased confidence in coping with stressful situations, which contributed to reducing anxiety (49). Hence, nurses with higher levels of social support had positive emotional states (22, 50). On the contrary, medical staff who have lower levels of social support are at higher risks of developing depressive symptoms (51). Therefore, higher levels of social support may mitigate the negative effects of work stress on depression and anxiety.

In line with hypothesis, self-efficacy mediated the relationship between work stress and mental health among PHWs. This means that work stress can reduce PHWs’ self-efficacy, which in turn can lead to depression and anxiety. Individuals with higher self-efficacy have greater confidence in their ability to handle and overcome work-related challenges and more likely to adopt positive coping strategies to achieve successful and satisfying performance, which may explain why self-efficacy can buffer the effects of work-related stress on mental health (32, 52). Thus, high occupational stress among hospital sanitation workers leads to reduce self-efficacy, which in turn puts them at higher risk of suffering from poor mental health during the COVID-19 epidemic (21). The current study conducted in primary PHWs fulfilled and expanded inadequate research findings on self-efficacy, while highlighting the need for interventions that focus on enhancing self-efficacy to alleviate the adverse effects of job stress on mental health.

Notably, the chain mediation role of social support and self-efficacy in the association between work stress and mental health (depression and anxiety) was first demonstrated in primary PHWs. The long-term accumulation of work-related stress can lead to lack of social support from family, friends and others due to busy work, and consequently losing self-confidence to cope with setbacks and difficulties, eventually leading to a significant increase in anxiety and depression (22). Moreover, social support, as a protective factor for self-efficacy, can provide additional external resources to help improve self-efficacy when individuals perceive work stress (23). And individuals with higher self-efficacy in the process of connecting with people who provide social support may positively cope with work stress and effectively reduce the adverse effects of work stress on mental health (53). Therefore, the current study showed the sequential mediating effect of social support and self-efficacy in the relationship between work stress and mental health, which also provides a potential mechanism for the interaction between individual internal characteristics (e.g., self-efficacy) and external environment (e.g., social support). The indirect effect sizes of social support and self-efficacy on work stress and mental health were not high, respectively, although such indirect effects were shown to be significant. This might be related to factors associated with blocking social support such as lockdowns and social isolation during COVID-19. The relationship and pathways between work stress and mental health are complex, which in turn indicates the need to explore other pathways and potential mechanisms between work stress and mental health. Finally, based on these, related institutions can implement more targeted psychological interventions to improve the psychological health and service quality of community PHWs.

Previous literature suggested that some psychological interventions might reduce anxiety and depressive symptoms by increasing self-efficacy and accessing more social support. For example, effective coping strategies, such as setting up special rest areas and counseling rooms, providing individual case work and group work, using online social platforms and developing healthy and optimistic behaviors, could obtain adequate social support from within or outside the family for coping with work stress and challenges, and reducing anxiety and depression (48). Group-based activities and psychiatric training that improved self-efficacy could reduce depression and anxiety symptoms (32, 53). In addition, interventions that simultaneously consider the interactive effects of social support and self-efficacy may be equally important in reducing the risk of anxiety and depression.

Several limitations of the current study should be considered. First, we failed to examine the causal relationships between work stress, social support, self-efficacy, and mental health due to the limitation of cross-sectional design. Therefore, the intrinsic mechanisms between variables should be further explored in more detail, combined with experimental and long-term longitudinal studies. Second, the main variables in this study were assessed by self-rating scales, which may not avoid resulting recall and social desirability bias. Third, primary PHWs information in this study was collected from all community health centers, but only from one city in China. Therefore, future studies need to conduct surveys in more cities to improve the generalizability of our findings.

Despite the above limitations of this study, this large-scale cross-sectional study with large sample sizes extended the literature on the direct and indirect relationship between work stress and mental health among primary PHWs. The findings of this study shed light on the critical role of social support and self-efficacy in alleviating work stress-induced anxiety and depressive symptoms among community PHWs. The present study contributed to explore the chain mediating pathways of social support and self-efficacy between work stress and mental health, which finding provides a new perspective on interventions to address work stress and mental health among primary PHWs. Therefore, this study has significant public health implications and provides a theoretical and practical basis for government and managers of primary health service center institutions to adopt targeted interventions.

Conclusion

This study showed a high prevalence of depression and anxiety symptoms among primary public health workers after the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak. Moreover, this study revealed that work stress has a significant positive direct effect on depression and anxiety symptoms among PHWs, with social support and self-efficacy playing an independent mediating role. These findings may provide a theoretical basis for developing psychosocial interventions for mental health of primary PHWs in China. Therefore, related healthcare institutions should pay more attention to the mental health of primary public workers, and enhancing social support for public health workers and improving their self-efficacy may be an effective approach to alleviate mental health in follow-up interventions.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethical Review Committee of School of Public Health, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (approval number: SJUPN-202108) and adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

YD: conceptualization, investigation, data curation, formal analysis, and writing – original draft. QZ: investigation, methodology, formal analysis, validation, and writing – original draft. RC: investigation, validation, and data curation. RW: investigation, methodology, and data curation. HH: conceptualization, supervision, and writing – review & editing. YC: conceptualization, funding acquisition, supervision, and writing review & editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was supported National Key R&D Program of China, Strategic Collaborative Innovation Team (2018YFC1705103). Shanghai Three-Year Action Plan for Public Health under Grant (GWV-10.1-XK18 and GWV-10.2-XD13). Shanghai Municipal Education Commission (2023-PHAPD-01-45). Hospital Management Program, China hospital development institute, Shanghai Jiao Tong University (CHDI-2022-B-05). Science and Technology Commission Shanghai Municipality (No. 20JC1410204).

Acknowledgments

We thank the leadership of the primary community health service centers for their support and all the primary public health workers who participated in the survey. Meanwhile, we also thank all the colleagues who participated in this study for their hard work and effort in collecting data.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1236645/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Hall, BJ, Li, G, Chen, W, Shelley, D, and Tang, W. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation during the Shanghai 2022 lockdown: a cross-sectional study. J Affect Disord. (2023) 330:283–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2023.02.121

2. Liu, Y, Chen, H, Zhang, N, Wang, X, Fan, Q, Zhang, Y, et al. Anxiety and depression symptoms of medical staff under COVID-19 epidemic in China. J Affect Disord. (2021) 278:144–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.004

3. Dragioti, E, Tsartsalis, D, Mentis, M, Mantzoukas, S, and Gouva, M. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of hospital staff: an umbrella review of 44 meta-analyses. Int J Nurs Stud. (2022) 131:104272. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2022.104272

4. Li, J, Xu, J, Zhou, H, You, H, Wang, X, Li, Y, et al. Working conditions and health status of 6,317 front line public health workers across five provinces in China during the COVID-19 epidemic: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. (2021) 21:106. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-10146-0

5. Liu, Y, Zou, L, Yan, S, Zhang, P, Zhang, J, Wen, J, et al. Burnout and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms among medical staff two years after the COVID-19 pandemic in Wuhan, China: social support and resilience as mediators. J Affect Disord. (2023) 321:126–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2022.10.027

6. Tang, L, Yu, XT, Wu, YW, Zhao, N, Liang, RL, Gao, XL, et al. Burnout, depression, anxiety and insomnia among medical staff during the COVID-19 epidemic in Shanghai. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:1019635. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1019635

7. Wang, LQ, Zhang, M, Liu, GM, Nan, SY, Li, T, Xu, L, et al. Psychological impact of coronavirus disease (2019) (COVID-19) epidemic on medical staff in different posts in China: a multicenter study. J Psychiatr Res. (2020) 129:198–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.07.008

8. Siegrist, J. Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. J Occup Health Psychol. (1996) 1:27–41. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.1.1.27

9. Magnavita, N, Soave, PM, and Antonelli, M. Prolonged stress causes depression in frontline workers facing the COVID-19 pandemic-a repeated cross-sectional study in a COVID-19 hub-Hospital in Central Italy. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:18. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18147316

10. Rugulies, R, Aust, B, and Madsen, IE. Effort-reward imbalance at work and risk of depressive disorders. A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Scand J Work Environ Health. (2017) 43:294–306. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3632

11. Zhang, J, Wang, Y, Xu, J, You, H, Li, Y, Liang, Y, et al. Prevalence of mental health problems and associated factors among front-line public health workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in China: an effort-reward imbalance model-informed study. BMC Psychol. (2021) 9:55. doi: 10.1186/s40359-021-00563-0

12. Buselli, R, Corsi, M, Veltri, A, Baldanzi, S, Chiumiento, M, Lupo, ED, et al. Mental health of health care workers (HCWs): a review of organizational interventions put in place by local institutions to cope with new psychosocial challenges resulting from COVID-19. Psychiatry Res. (2021) 299:113847. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113847

13. Yang, C, Liu, W, Chen, Y, Zhang, J, Zhong, X, Du, Q, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for mental health symptoms in community epidemic prevention workers during the postpandemic era of COVID-19 in China. Psychiatry Res. (2021) 304:114132. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114132

14. Salari, N, Khazaie, H, Hosseinian-Far, A, Khaledi-Paveh, B, Kazeminia, M, Mohammadi, M, et al. The prevalence of stress, anxiety and depression within front-line healthcare workers caring for COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-regression. Hum Resour Health. (2020) 18:100. doi: 10.1186/s12960-020-00544-1

15. Ahn, MH, Shin, YW, Suh, S, Kim, JH, Kim, HJ, Lee, KU, et al. High work-related stress and anxiety as a response to COVID-19 among health Care Workers in South Korea: cross-sectional online survey study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. (2021) 7:e25489. doi: 10.2196/25489

16. Cohen, S, and Wills, TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull. (1985) 98:310–57. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310

17. Lazarus, RS. Coping theory and research: past, present, and future. Psychosom Med. (1993) 55:234–47. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199305000-00002

18. Lin, HS, Probst, JC, and Hsu, YC. Depression among female psychiatric nurses in southern Taiwan: main and moderating effects of job stress, coping behaviour and social support. J Clin Nurs. (2010) 19:2342–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03216.x

19. Wu, H, Ge, CX, Sun, W, Wang, JN, and Wang, L. Depressive symptoms and occupational stress among Chinese female nurses: the mediating effects of social support and rational coping. Res Nurs Health. (2011) 34:401–7. doi: 10.1002/nur.20449

20. Azemi, S, Dianat, I, Abdollahzade, F, Bazazan, A, and Afshari, D. Work-related stress, self-efficacy and mental health of hospital nurses. Work. (2022) 72:1007–14. doi: 10.3233/WOR-210264

21. Nawal, A, Shoaib, M, Zamecnik, R, and Rehman, AU. Effects of occupational stress, self-efficacy and mental health during the pandemic on hospital sanitation Workers in Malaysia. Eval Health Prof. (2022) 45:313–24. doi: 10.1177/01632787221112079

22. Chen, J, Li, J, Cao, B, Wang, F, Luo, L, and Xu, J. Mediating effects of self-efficacy, coping, burnout, and social support between job stress and mental health among young Chinese nurses. J Adv Nurs. (2020) 76:163–73. doi: 10.1111/jan.14208

23. Liu, Y, and Aungsuroch, Y. Work stress, perceived social support, self-efficacy and burnout among Chinese registered nurses. J Nurs Manag. (2019) 27:1445–53. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12828

24. Gao, LL, Sun, K, and Chan, SW. Social support and parenting self-efficacy among Chinese women in the perinatal period. Midwifery. (2014) 30:532–8. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2013.06.007

25. Yang, WJ, and Li, J. Measurement of psychosocial factors in work environment: application of two models of occupational stress. Zhonghua Lao Dong Wei Sheng Zhi Ye Bing Za Zhi. (2004) 22:422–6.

26. Li, P, Wang, Y, Liu, B, Wu, C, He, C, Lv, X, et al. Association of job stress, FK506 binding protein 51 (FKBP5) gene polymorphisms and their interaction with sleep disturbance. PeerJ. (2023) 11:e14794. doi: 10.7717/peerj.14794

27. Tian, M, Zhou, X, Yin, X, Jiang, N, Wu, Y, Zhang, J, et al. Effort-reward imbalance in emergency department physicians: prevalence and associated factors. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:793619. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.793619

28. Siegrist, J, Starke, D, Chandola, T, Godin, I, Marmot, M, Niedhammer, I, et al. The measurement of effort-reward imbalance at work: European comparisons. Soc Sci Med. (2004) 58:1483–99. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00351-4

29. Zimet, GD, Powell, SS, Farley, GK, Werkman, S, and Berkoff, KA. Psychometric characteristics of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. (1990) 55:610–7. doi: 10.1080/00223891.1990.9674095

30. Yang, Y, Wang, P, Kelifa, MO, Wang, B, Liu, M, Lu, L, et al. How workplace violence correlates turnover intention among Chinese health care workers in COVID-19 context: the mediating role of perceived social support and mental health. J Nurs Manag. (2022) 30:1407–14. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13325

31. Zhang, JX, and Schwarzer, R. Measuring optimistic self-beliefs: a Chinese adaptation of the general self-efficacy scale. Psychologia. (1995) 38:174–81.

32. Sun, Y, Song, H, Liu, H, Mao, F, Sun, X, and Cao, F. Occupational stress, mental health, and self-efficacy among community mental health workers: a cross-sectional study during COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Soc Psychiatry. (2021) 67:737–46. doi: 10.1177/0020764020972131

33. Hu, J, Huang, Y, Liu, J, Zheng, Z, Xu, X, Zhou, Y, et al. COVID-19 related stress and mental health outcomes 1 year after the peak of the pandemic outbreak in China: the mediating effect of resilience and social support. Front Psych. (2022) 13:828379. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.828379

34. Spitzer, RL, Kroenke, K, Williams, JB, and Lowe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. (2006) 166:1092–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

35. Fawzi, MCS, Ngakongwa, F, Liu, Y, Rutayuga, T, Siril, H, Somba, M, et al. Validating the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for screening of depression in Tanzania. Neurol Psychiatry Brain Res. (2019) 31:9–14.

36. Kroenke, K, Spitzer, RL, and Williams, JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. (2001) 16:606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

37. Lixia, W, Xiaoming, X, Lei, S, Su, H, Wo, W, Xin, F, et al. A cross-sectional study of the psychological status of 33,706 hospital workers at the late stage of the COVID-19 outbreak. J Affect Disord. (2022) 297:156–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.10.013

38. Podsakoff, PM, MacKenzie, SB, Lee, JY, and Podsakoff, NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. (2003) 88:879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

39. Chen, R, Liu, YF, Huang, GD, and Wu, PC. The relationship between physical exercise and subjective well-being in Chinese older people: the mediating role of the sense of meaning in life and self-esteem. Front Psychol. (2022) 13:1029587. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1029587

40. Preacher, KJ, and Hayes, AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods. (2008) 40:879–91. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879

41. Aymerich, C, Pedruzo, B, Perez, JL, Laborda, M, Herrero, J, Blanco, J, et al. COVID-19 pandemic effects on health worker's mental health: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Psychiatry. (2022) 65:e10. doi: 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2022.1

42. Saragih, ID, Tonapa, SI, Saragih, IS, Advani, S, Batubara, SO, Suarilah, I, et al. Global prevalence of mental health problems among healthcare workers during the Covid-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. (2021) 121:104002. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.104002

43. Wu, T, Jia, X, Shi, H, Niu, J, Yin, X, Xie, J, et al. Prevalence of mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. (2021) 281:91–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.11.117

44. Araujo, TM, de Sousa, CC, and Siegrist, J. Stressful work in primary health care and mental health: the role of gender inequities in Brazil. Am J Ind Med. (2022) 65:604–12. doi: 10.1002/ajim.23360

45. Shi, LS, Xu, RH, Xia, Y, Chen, DX, and Wang, D. The impact of COVID-19-related work stress on the mental health of primary healthcare workers: the mediating effects of social support and resilience. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:800183. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.800183

46. Zou, Y, Lu, Y, Zhou, F, Liu, X, Ngoubene-Atioky, AJ, Xu, K, et al. Three mental health symptoms of frontline medical staff associated with occupational stressors during the COVID-19 peak outbreak in China: the mediation of perceived stress and the moderation of social support. Front Psychol. (2022) 13:888000. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.888000

47. Ashley, C, James, S, Williams, A, Calma, K, McInnes, S, Mursa, R, et al. The psychological well-being of primary healthcare nurses during COVID-19: a qualitative study. J Adv Nurs. (2021) 77:3820–8. doi: 10.1111/jan.14937

48. Wu, N, Ding, F, Zhang, R, Cai, Y, and Zhang, H. The relationship between perceived social support and life satisfaction: the chain mediating effect of resilience and depression among Chinese medical staff. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:19. doi: 10.3390/ijerph192416646

49. Zhu, W, Wei, Y, Meng, X, and Li, J. The mediation effects of coping style on the relationship between social support and anxiety in Chinese medical staff during COVID-19. BMC Health Serv Res. (2020) 20:1007. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05871-6

50. Labrague, LJ, and De Los Santos, JAA. COVID-19 anxiety among front-line nurses: predictive role of organisational support, personal resilience and social support. J Nurs Manag. (2020) 28:1653–61. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13121

51. Song, X, Fu, W, Liu, X, Luo, Z, Wang, R, Zhou, N, et al. Mental health status of medical staff in emergency departments during the coronavirus disease 2019 epidemic in China. Brain Behav Immun. (2020) 88:60–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.06.002

52. Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. (1977) 84:191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191

53. Rippon, D, Shepherd, J, Wakefield, S, Lee, A, and Pollet, TV. The role of self-efficacy and self-esteem in mediating positive associations between functional social support and psychological wellbeing in people with a mental health diagnosis. J Ment Health. (2022) 5:1–10. doi: 10.1080/09638237.2022.2069695

Keywords: depression, anxiety, social support, self-efficacy, healthcare worker, mediating effect

Citation: Dong Y, Zhu Q, Chang R, Wang R, Cai Y and Huang H (2023) Association between work stress and mental health in Chinese public health workers during the COVID-19 epidemic: mediating role of social support and self-efficacy. Front. Public Health. 11:1236645. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1236645

Edited by:

Juan Jesús García-Iglesias, University of Huelva, SpainReviewed by:

Riyu Pan, Anqing Normal University, ChinaCihad Dundar, Ondokuz Mayıs University, Türkiye

Copyright © 2023 Dong, Zhu, Chang, Wang, Cai and Huang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yong Cai, Y2FpeW9uZzIwMjAyOEBob3RtYWlsLmNvbQ==; Hong Huang, aHVhbmdob25nMTk2M0BvdXRsb29rLmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Yinqiao Dong1†

Yinqiao Dong1† Rongxi Wang

Rongxi Wang Yong Cai

Yong Cai