- 1School of Business, Faculty of Business, Education, Law and Arts, University of Southern Queensland, Toowoomba, QLD, Australia

- 2Centre for Health Research, University of Southern Queensland, Toowoomba, QLD, Australia

- 3National Centre for Epidemiology and Population Health, College of Health and Medicine, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT, Australia

- 4College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Bahir Dar University, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia

Socioeconomic status affects individuals’ health behaviors and contributes to a complex relationship between health and development. Due to this complexity, the relationship between SES and health behaviors is not yet fully understood. This literature review, therefore, aims to assess the association between socioeconomic status and health behaviors in childhood and adolescence. Preferred Reporting for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis protocol guidelines were used to conduct a systematic literature review. The electronic online databases EBSCO Host, PubMed, Web of Science, and Science Direct were utilized to systematically search published articles. The Joanna Briggs Institute’s critical appeal tool was used to assess the quality of included studies. Eligibility criteria such as study context, study participants, study setting, outcome measures, and key findings were used to identify relevant literature that measured the association between socioeconomic status and health behaviors. Out of 2,391 studies, only 46 met the final eligibility criteria and were assessed in this study. Our review found that children and adolescents with low socioeconomic status face an elevated risk of unhealthy behaviors (e.g., early initiation of smoking, high-energy-dense food, low physical activity, and involvement in drug abuse), in contrast to their counterparts. Conversely, children and adolescents from higher socioeconomic backgrounds exhibit a higher prevalence of health-promoting behaviors, such as increased consumption of fruit and vegetables, dairy products, regular breakfast, adherence to a nutritious diet, and engagement in an active lifestyle. The findings of this study underscore the necessity of implementing specific intervention measures aimed at providing assistance to families from disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds to mitigate the substantial disparities in health behavior outcomes in children and adolescents.

1. Introduction

Health behavior constitutes a fundamental facet of individuals’ holistic well-being, exerting a substantial influence on their physical health, mental well-being, and overall longevity (1–5). Over the past decades, considerable attention has been directed toward comprehending health behaviors and cultivating healthy lifestyles (6–9). However, socioeconomic status (SES) (e.g., income, education, occupation, social position) pose a significant obstacle to achieving these objectives (10). Thus, people from low-SES backgrounds are more likely to exhibit a higher rate of smoking tobacco, drinking alcohol, excess weight gain, and a sedentary lifestyle, which has been consistently identified as a pivotal determinant of premature and preventable morbidity and mortality compared to their counterparts (11–13).

The literature reveals that children and adolescents’ health and health behaviors primarily depend on their parental SES backgrounds (14–18). It is well documented that children and adolescents from high parental SES backgrounds have more access to education, housing, food, clothing, health services, and social services (19–23). These advantageous services enhance self-confidence, self-esteem, and self-efficacy, which promotes a healthy lifestyle and reduces the risk of stress in youngsters (14, 15, 17). In contrast, parental support, healthy parental lifestyle, medical services, and social networks are less open to children and adolescents with low parental SES (21, 24–27). Hence, poor availability of goods and services increases the likelihood of physical and mental health issues and encourages them to adopt risky behaviors (e.g., smoking, drinking alcohol, illicit drug use, gambling) to deal with their concerns (28–33). Therefore, parental social, cultural, and economic status are fundamental determinants of health and health behaviors in children and adolescents, which are apparent from the early stages of life and persist into adolescence (34, 35).

Globally, millions of children, particularly those with low socioeconomic profiles, do not start their lives in a healthy state (36, 37). This could be due to insufficient goods and services, which are the primary causes of impairment in children’s neuro-biological development, resulting in poor social, emotional, psychological, and physiological outcomes (38, 39). Thus, focusing on improving support for deprived and underserved populations is a powerful strategy to establish the roots of healthy behaviors in childhood and adolescent development (40). Therefore, it is recommended that every government adopt a health and health equity policy program to promote positive health behaviors among its population (41–44).

Numerous studies have been documented in the international literature to determine (45), analyze (46), and explored (47, 48) the relationship between SES and health behaviors in children and adolescents. For example, in a study conducted by Liu et al. (49), adolescents hailing from families with lower parental SES exhibited a significantly higher likelihood of [OR = 2.12, 95% CI, 1.49–3.01] cigarette smoking than those from middle and high SES backgrounds. Melotti et al. (50) explored the association between parental SES and alcohol consumption among adolescents. They discovered an inverse association, revealing that adolescents with low SES had higher odds (OR: 1.26, 95% CI, 1.05–1.52) of consuming alcohol compared to those with high SES backgrounds. Furthermore, a seminal study by Krist et al. (51) investigated the impact of parental SES on physical activity levels in children and adolescents. The results indicated that those from lower parental SES backgrounds were less likely to engage in regular physical activity (OR = 0.90, 95% CI 0.63–1.29) in comparison to their peers from higher SES backgrounds. Collectively, this extensive body of evidence underscores the pivotal role played by parental SES in shaping the multifaceted landscape of health behaviors among children and adolescents. These disparities in health behaviors often contribute to adverse health outcomes, including a heightened prevalence of chronic diseases such as obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases (52).

Given the evidence above, examining the association between parental SES and health behaviors of children and adolescents holds profound scientific significance and societal consequences. Thus, a good understanding of how parental SES influences health behaviors among young individuals enables the identification of vulnerable populations at an early stage, allowing for targeted interventions and preventive measures to combat socioeconomic comorbidities and their consequences during childhood and adolescence. However, to the best of our knowledge, the existing body of literature examining the association between SES and health behaviors (e.g., protective health behaviors and damaging health behaviors) among children and adolescents remains limited (45–47, 53, 54). To address this gap in the literature, this review comprehensively examines the association between SES and health behaviors in children and adolescents aged 3–18 years, utilizing the literature on SES and health behaviors. In this review, health behaviors were examined in two ways: (i) protecting health behaviors and (ii) impairing health behaviors among children and adolescents. Protecting health behaviors is defined as the consumption of fruit vegetables, consumption of dairy products, regular breakfast, and involvement in physical activity during leisure time (55). Consumption of high-fatty foods (e.g., chips, noodles), high sugary drinks (e.g., fruit juice, Coco Cola, cordial) and engagement in smoking (i.e., tobacco, cannabis), illicit drugs, alcohol consumption, and sedentary activities during their leisure time are defined as unhealthy behaviors exhibited by children and adularescent (56). In this review study, we were particularly interested to examining two important research questions: (i) Does low socioeconomic status influence risky or impair health behavior patterns among children and adolescents compared to their counterparts? (ii) What is the association between SES and health behaviors in children and adolescents? Through an exploration of these research questions, this study will help to better understand the relationship between SES and health behaviors in children and adolescents. By doing so, this study seeks to provide valuable insights that can inform potential policy interventions aims at enhancing the health behavior outcomes of children and adolescents, particularly those who come from underserved and disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds.

2. Methods

This review article followed the Preferred Reporting for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocol (PRISMA-P) guidelines in order to identify studies that were screened, included and excluded in this review (57). PRISMA-P helps to provide a guideline for development of protocol for systematic review, and meta-analysis in order to improve the quality and transparency of the studies (58, 59). In this review, we used the PRIMA checklist shown in Supplementary Table S3.

2.1. Data sources and literature search

To identify relevant articles on SES and health behaviors in childhood and adolescence, different electronic databases of various disciplines were searched, including Academic Search, APA PsycArticles, APA PsycInfo, Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Health Source, Nursing/Academic Edition, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, Sociology Source, Sociology Source Ultimate, PubMed, Web of Science, and Science Direct. These electronic databases were searched using the keywords: socioeconomic, “socio-economic,” “health behavior,” “health behavior,” “health behaviors,” “health behaviors,” teen*, adolescent*, and child*” (see Supplementary Table S1). The articles were subsequently exported using EndNote citation manager X9 version.

2.2. Criteria of included studies

In this systematic literature review, we included studies that reported an association between SES and health behaviors. Additionally, we considered studies that had at least one specific health behavior, either protecting or impairing health behaviors, such as smoking, drinking alcohol, illicit drugs, physical exercise, consumption of fruit and vegetables, and dietary habits. Consequently, all peer-reviewed prospective, retrospective, quantitative studies from both developed and developing countries, published in the English language were included. Subsequently, national representative surveys (cross-national and longitudinal) consisting of more than 500 samples from the sampled population (i.e., children and adolescents aged 3–18 years) were also included. In this study, we considered children (i.e., 3–12 years) and adolescents (13–18 years of age) as defined by the US Department of Health and Johns Hopkins Medicine, respectively (60, 61). In summary, the inclusion criteria for this review study were structured in accordance with the PICOS model, where: “P” = Population (i.e., children and adolescents aged 3 to 18 years old), “I” = intervention (we do not have intervention in this review study), “C” = comparator (i.e., high SES and low SES backgrounds), “O” = Outcome of this study (i.e., health behavior either protecting or impairing health behaviors), and “S” = study design (i.e., cross-sectional, longitudinal only).

2.3. Criteria of excluded studies

Based on predefined eligibility criteria, we evaluated the titles and abstracts of the identified studies. In cases where the studies were found relevant to our review, we thoroughly assessed the full text. However, if the studies were not relevant to our study, such as national income inequalities and health behavior or national per-capita income inequalities and health behaviors in childhood and adolescence, we excluded such studies. Additionally, if the study did not meet the eligibility criteria such as population, comparator, outcome, and study design, we excluded the paper from this study. For example, review articles, pilot studies, reports, dissertations, books, symposia, supplementary, prospective, or intervention studies, and articles published in other languages. Articles published before 2000 were also excluded from this study, primarily because their full-text versions were not readily accessible. Furthermore, articles with a sample size of less than 500 were excluded from the analysis. The decision to exclude studies with a sample size less than 500 was driven by a combination of methodological constraints. Two articles had sample sizes of 246 and 310, respectively; however, these studies found no association between SES and health behaviors in adolescents. Therefore, we decided to exclude them from the final analysis.

2.4. Data extraction

The data extraction was done by two independent reviewers using a data extraction table. The data extraction was based on the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) checklist (e.g., country, study setting/context, participant characteristics, outcome measures, and key findings). The final data extraction was based on the phase two screening of studies (i.e., 46 studies) by NG following the PRISMA guidelines (57), while GD, MMR, and RK approved data extraction.

2.5. Quality assessment of study

The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) and System for the Unified Management of the Assessment and Review of Information (SUMARI) is an appraisal tools assist in evaluation of the trustworthiness outcomes of the included studies (62–64). For the cross-sectional studies, JBI SUMARI apprise as follows: (i) inclusion criteria were clearly defined for the study population; (ii) study subject and study setting were clearly explained; (iii) exposures were scientifically measured; (iv) standard criteria and objectives were used to assess the measurement of the study; (v) confounding factors were identified; (vi) a strategic plan was developed to address the confounding factors; (vii) the results of the studies were reliable and valid; (viii) an appropriate statistical method was used to analyze the study. On the other hand, cohort studies were evaluated as follows: (i) the sample was recruited from the study population; (ii) exposures were measured equally between the exposed and unexposed groups; (iii) exposures were measured in a valid and reliable way; (iv) confounding factors were identified; (v) the statistical plan was used to address the confounding factors; (vi) at the beginning of the study, the sampled population was free from exposures; (vii) outcomes of the study were measured in a valid and reliable way; (viii) follow-up time was sufficiently reported; (ix) follow-up was completed, and if not, reasons were well explained; (x) plans were explored to address the issue of those in the sample lost to follow-up; (xi) the standard statistical method to analyze the study was used. To establish the credibility of our findings, every included study was apprised using the JBI SUMARI and provided the score for each study by two independent reviewers. Studies were included in this review if they had gained a score of 60 percent or above, while studies with a score of less than 60 percent were excluded. However, in the context of this study appraisal, none of the papers met the criteria for a score below 60 percent. As a result, it was not necessary to exclude any studies through the application of the JBI SUMARI appraisal tools (see Supplementary Table S4). In alignment with these principles, our review study also employed the JBI SUMARI to contribute to the overall reliability and quality of the review findings (65, 66).

Furthermore, the risk of bias in the included studies was evaluated using the 10-item grading scale for prevalence studies developed by Hoy et al. (67). The study methodology, case definition, prevalence periods, sampling, data collection, reliability, and validity of the investigations were thoroughly scrutinized. Each study was categorized as exhibiting either a low risk of bias (shown by affirmative replies to domain questions) or a high risk of bias (indicated by negative responses to domain questions). In each study, a binary scoring system was used to assign a value of 1 (indicating presence) or 0 (indicating absence) to each domain. The cumulative sum of these domain values was used to derive the overall study quality score. The assessment of bias risk was performed by calculating the total number of high-risk biases in each study. Studies were categorized as having a low risk of bias if they had two or fewer high-risk biases, moderate risk of bias if they had three or four high-risk biases, and high risk of bias if they had five or more high-risk biases. To resolve discrepancies among the reviewers, a consensus-based approach was employed for the final categorization of the risk of bias (see Supplementary Table S5).

2.6. Outcome measurement of the study

The outcomes of this study were health behaviors, either through health-protective behaviors (e.g., consumption of fruit and vegetables, consumption of a healthy diet, physical exercise) or impairing health behaviors (e.g., smoking, drinking alcohol, high sedentary lifestyle and illicit drug use), in children and adolescents (68). Childhood and adolescence are two distinct stages of life that are characterized by diverse features in the respective age groups (e.g., physical and psychological) (69, 70). Childhood is a time of rapid and remarkable development, encompassing significant strides in the physical, cognitive, social, and emotional dimensions that outpace the progress seen in other life stages. During this period, children’s innate intellectual curiosity flourishes, driving them to explore the world around them and actively engage in interactive experiences (71, 72). On the other hand, adolescence is widely acknowledged as a transformative phase known as the “storm and stress” period, characterized by profound changes in biological, cognitive, psychosocial, and emotional realms (73). These transformative shifts often give rise to a range of adjustment challenges, including mood swings, propensity for risk-taking behaviors, and conflicts with both parental figures and peers (73). Thus, considering the relationship between health behaviors in childhood and adolescence is pivotal, therefore, this review study examined the association between parental SES and health behaviors in children and adolescents separately.

2.7. Measure of socioeconomic status (SES)

SES is a multidimensional construct and is measured objectively by income, education, and occupation, or subjectively by prestige, place of residence, ethnic origin, or religious background, covering both objective and subjective measures of SES (74–76). The stratification of SES into subgroups (e.g., low SES and high SES) was predicted based on goods and materials consumed by the individual in a household, including durable goods such as televisions, bicycles, and vehicles, as well as housing-related attributes such as access to drinking water, food, bathroom facilities, and agricultural and flooring materials (77). Households that possessed adequate provision of food, water, hand-washing materials, agricultural products, fields for production, and other consumer items for a duration of merely 6 months were categorized as having low-income or low- SES backgrounds. On the other hand, families that possessed an ample supply of food and other products, including consumer goods, to sustain themselves for a period of 12 months or more were classified as affluent or wealthy or high SES backgrounds (77, 78). Based on previous literature (21, 22, 77, 79, 80), our study defined low SES and high SES backgrounds and examined the association between SES and health behaviors in children and adolescents.

3. Results

3.1. Description of the study

In this systematic literature review, 2,391 articles were initially retrieved, and 585 duplicates were removed before entering the first phase of screening. A total of 1806 articles were assessed in the first phase of screening based on their titles and abstracts. Thus, in the first screening phase, we retained only 146 articles and rejected 1,660 articles. Consequently, in phase two of the screening, we assessed 146 papers based on their full text. Of these, only 46 articles met the inclusion criteria for further evaluation. Hence, these 46 articles were eligible in our final review, which is shown in Figure 1.

A total of 46 articles were assessed to examine the association between SES and health behaviors in childhood and adolescence. Most of the studies were from Europe (n = 36), followed by Asia (n = 9), North America (n = 5), and Africa (n = 2). There has been a noticeable increase in studies on SES and health behavior in childhood and adolescence in the past decade (i.e., 2010 to 2020). From a total of 46 studies, 13 studies (79, 81–92) were published between 2000 to 2010, while 33 studies (25, 47–51, 53, 93–118) were published from 2011 to 2022.

3.2. Parental socioeconomic status and smoking

3.2.1. Parental socioeconomic status and smoking among children

From a total of 46 studies, 18 studies (25, 47, 49, 50, 53, 79, 81, 84, 86–88, 93, 96, 97, 104, 105, 107, 109) showed an association between SES and smoking behavior in children and adolescents. Out of 18 studies, five reported a positive association between low SES and smoking behavior in children, implying that children with low SES had a greater risk of exposure to early smoking, and experimenting with smoking, compared to those who were from a high SES background (25, 49, 53, 104, 105).

3.2.2. Parental socioeconomic status and smoking among adolescents

From a total of 18 studies, 12 studies showed a positive association between low SES and smoking behaviors in adolescents, indicating that adolescents with low SES had a higher risk of smoking behaviors than those with a high SES background (50, 79, 81, 84, 86–88, 93, 96, 97, 107, 109), while one study found a negative association between low SES and smoking behavior (47). In summary, a majority of 17 studies (94.44%) supported that children (5 studies, 27.77%) and adolescents (12 studies, 66.66%) from low SES backgrounds were more likely to be exposed to, have tried, or smoked daily, compared to those with high SES (see Table 1).

3.3. Parental socioeconomic status and drinking alcohol

3.3.1. Parental socioeconomic status and drinking alcohol among children

Out of 46 studies, 18 studies (25, 47, 50, 53, 79, 83–85, 91, 97, 100–102, 104, 105, 107, 108, 115) assessed the association between SES and drinking alcohol. Of them, seven studies reported a positive association between high SES and drinking alcohol in children (25, 53, 83, 102, 104, 105, 115). This implies that younger children from higher SES backgrounds are more likely to experiment with drinking alcohol compared with their counterparts. One study found a negative association between drinking alcohol and high SES (100).

3.3.2. Parental socioeconomic status and drinking alcohol among adolescents

With regard to SES and drinking alcohol by adolescents, from 18 studies, six reported a negative association between drinking alcohol and high SES (50, 85, 91, 101, 107, 108). Conversely, three studies reported a positive association between drinking alcohol and high SES (47, 79, 97). This positive association indicates that adolescents from a high SES background were found to have a higher chance of drinking alcohol than their counterparts. Moreover, a study by Richter et al. (84) reported that adolescents from Western, Northern, Southern (except Spain), Central and Eastern (except Latvia) Europe, and from a low SES background, were found to have a lower chance of drinking alcohol compared to their counterparts; however, adolescents from Scotland, Wales, Norway, Finland, Denmark, Greece, Italy, Malta, Hungary, Russia, and Ukraine were only statistically significant. In summary, out of 18 studies, children (seven studies, or 38.88%) and adolescents (three studies, or 16.66%) from a high SES background had a higher chance of drinking alcohol than those from a low SES background, while six studies (33.33%) found a negative association between a high SES background and drinking alcohol in adolescents (Table 2).

3.4. Parental socioeconomic status and physical activity (PA)

3.4.1. Parental socioeconomic status and physical activity (PA) among children

We identified 15 studies (25, 48, 51, 53, 81, 89, 92, 94, 97, 98, 104, 105, 110, 113, 117) that examined the association between SES and PA. From a total of 15 studies, seven found a positive association between high SES and PA in children (25, 48, 51, 98, 104, 110, 117); however, two reported a negative association between high SES and PA (53, 105). This negative association implies that those children from a high SES background had a lower chance of being physically active compared to their counterparts.

3.4.2. Parental socioeconomic status and physical activity (PA) among adolescents

Five studies found a positive association between high-SES and physical activity in adolescents (89, 92, 94, 97, 113). These findings implied that the adolescents from high parental SES backgrounds were more physically active compared to their counterparts, while one study found a negative association between high SES and PA (81). In summary, children from high-SES backgrounds in seven studies (46.66%) and adolescents in five studies (33.33%) had a higher chance of being more physically active than those from low- SES backgrounds (Table 3).

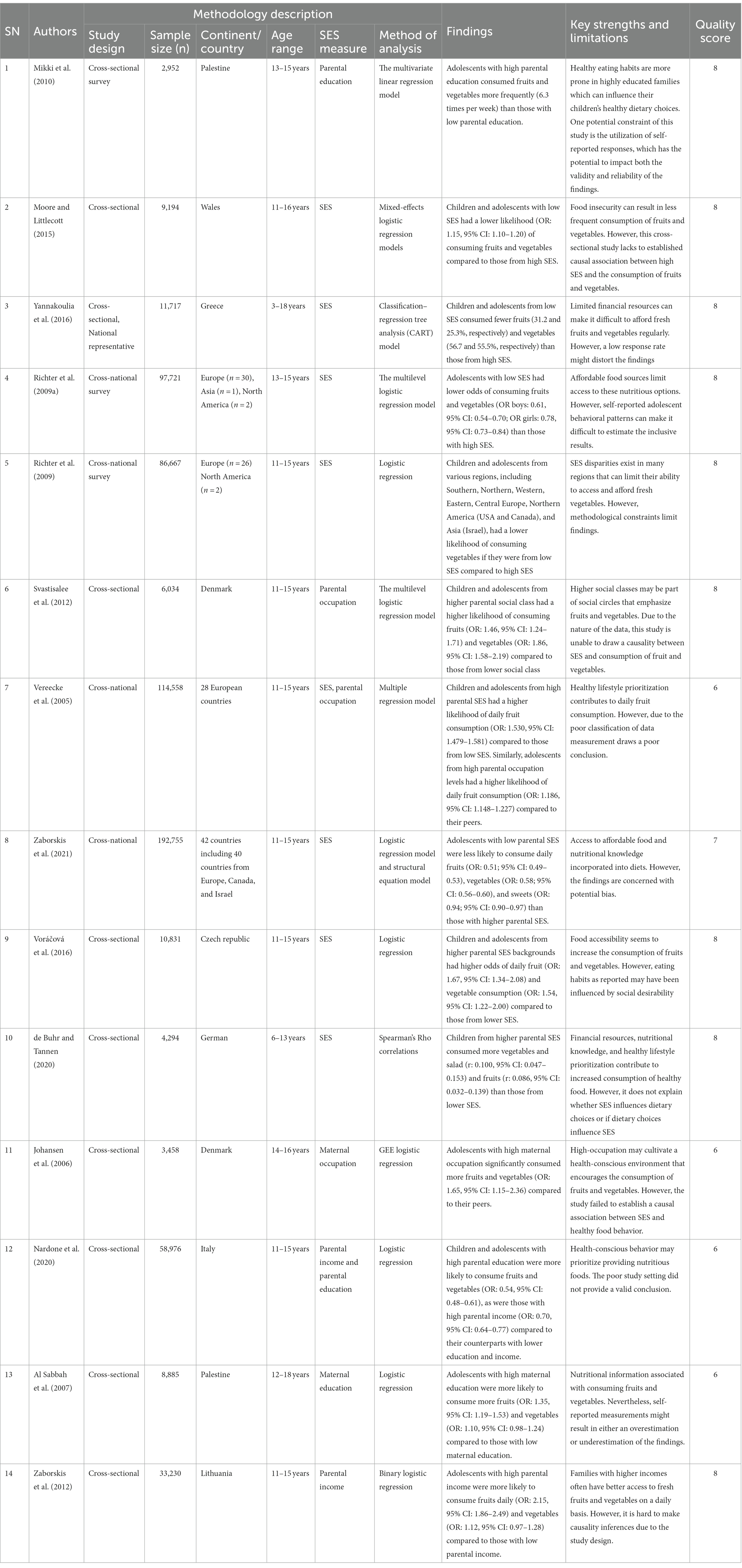

3.5. Parental socioeconomic status and fruits/vegetables

3.5.1. Parental socioeconomic status and fruits/vegetables among children

Fourteen studies (48, 53, 79, 81, 82, 84, 89, 90, 95, 99, 106, 110, 111, 118) were identified that examined the association between SES and fruit and vegetable consumption. Ten of these studies found a positive link between high SES and children’s consumption of fruits and vegetables (48, 53, 82, 84, 95, 99, 106, 110, 111, 118), which implies that children from a high SES background had a higher chance of consuming high amounts of fruits and vegetables compared to those from low SES backgrounds.

3.5.2. Parental socioeconomic status and fruits/vegetables among adolescents

From 14 studies that examined the association between SES and the consumption of fruits and vegetables, four studies found a positive association between high SES and the consumption of fruit and vegetables in adolescents (79, 81, 89, 90). A study by Vereecken et al. (82) reported that adolescents from Europe (West, South, North, Central, East), North America, and Asia with low SES were less likely to consume fruits and vegetables than those from high-SES backgrounds. Adolescents from low- SES families in Western Europe, Northern Europe, Southern Europe, North-Eastern Europe (except Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Russia, and Ukraine), North America, and Asia were less likely to consume vegetables than their counterparts. Overall, high SES was associated with greater rates of fruit and vegetable consumption among children (10 studies or 71.42%) and adolescents (4 studies or 28.57%) compared to low SES (see Table 4).

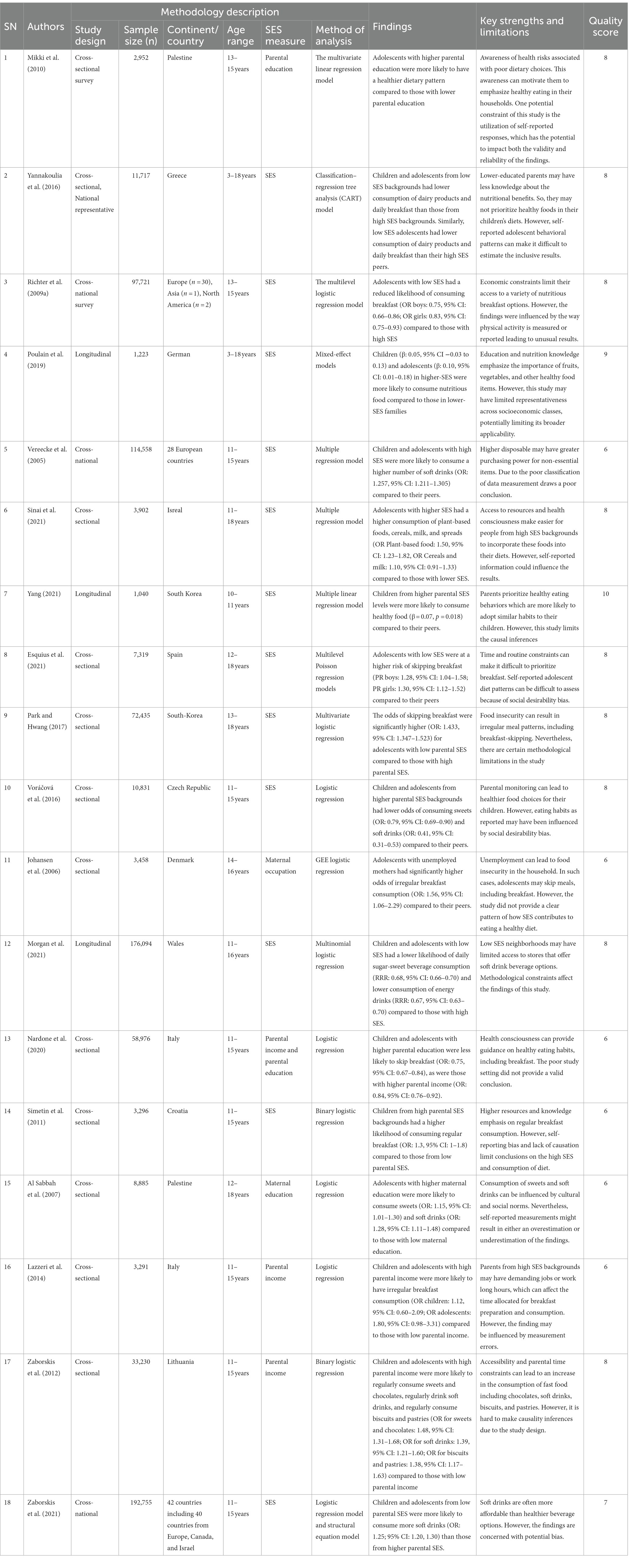

3.6. Parental socioeconomic status and dietary habits

3.6.1. Parental socioeconomic status and dietary habits among children

A total of 46 studies were included in this review study. Of these, 18 studies (25, 48, 79, 81, 82, 89, 90, 97, 99, 104–106, 111, 112, 114, 116–118) examined the association between SES and healthy diet habits in childhood and adolescence. Of a total of 18 studies, six studies revealed a positive association between high SES and healthy diet habits (e.g., animal products, nutritious food, balanced diet, breakfast) in children (25, 48, 104, 111, 116, 117). Consequently, another four studies reported a positive association between high SES and unhealthy diet (e.g., Biscuits, pastries, irregular breakfast, sweet foods, and soft drinks) (82, 89, 106, 114), while three studies found a negative association between high SES and low consumption of unhealthy dietary foods (99, 105, 118).

3.6.2. Parental socioeconomic status and dietary habits among adolescents

Out of 18 studies that examined the association between SES and dietary habits, five studies reported a positive association between high SES and consumption of healthy dietary food in adolescents (79, 81, 90, 97, 112), implying that adolescents with high parental SES had a higher probability of consuming a high proportion of dairy products, a regular breakfast, a healthy or nutritious diet, a balanced diet, and a low proportion of high-fat diet than those with low SES (see Table 5). In summary, six (33.33%) and five studies (27.77%) were positively associated with high SES and healthy dietary habits in childhood and adolescence, respectively.

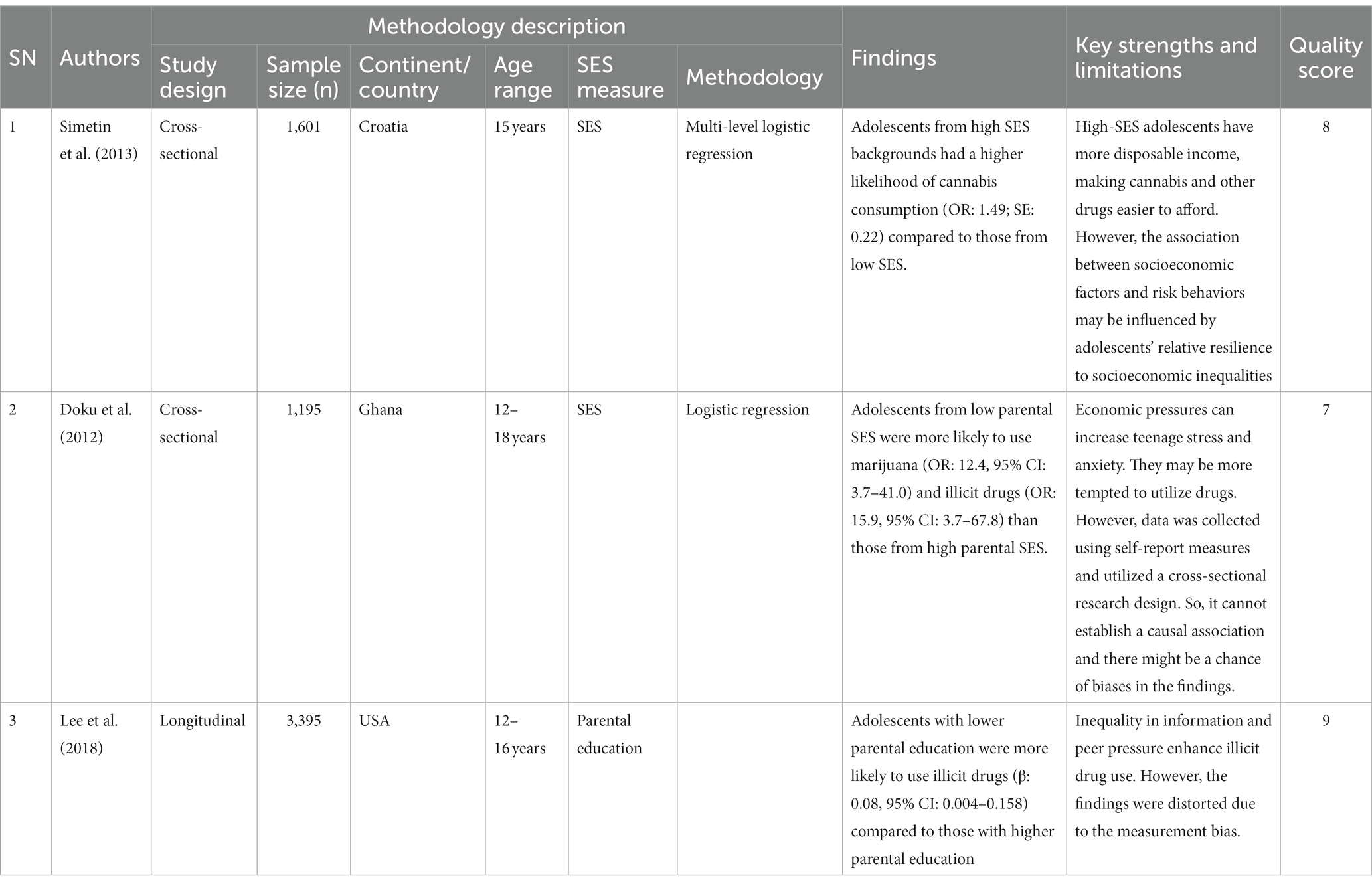

3.7. Parental socioeconomic status and cannabis, marijuana, and illicit drug use by adolescents

In this literature review, we assessed three studies (47, 101, 103) out of 46 that examined the relationship between SES and cannabis use and illicit drugs. Of these, one study reported a negative association between high SES and cannabis use (47), while another found a negative relationship between high SES and marijuana consumption (101). Similarly, two other studies found a negative association between high SES and illicit drugs used by adolescents (101, 103). This indicates that adolescents with low SES were found to consume cannabis, marijuana, and illicit drugs more frequently than adolescents from high SES backgrounds. In summary, 66.66%, or two studies, reported a negative association between high SES and illicit drug used in adolescents (see Table 6).

4. Discussion

Our study produced evidence, mostly from cross-sectional and longitudinal studies, that consistently demonstrates a strong relationship between SES and health behaviors. SES plays a major and well-documented influence in the onset and progression of chronic diseases in children and adolescents. Lower-income children and adolescents may have less access to frequent check-ups, preventative care, and early disease identification, increasing their risk of acquiring chronic disorders. Furthermore, SES influences the availability and cost of healthy food. Low-income families may struggle to offer adequate diets, which can contribute to poor eating habits, obesity, and linked chronic illnesses such as type 2 diabetes (52, 119, 120). Childhood and adolescence are regarded as pivotal stages in the development of life foundations in the general population. Focusing on younger ages is important because health behaviors can be learned and consolidated during these ages, affecting an individual’s health for the rest of their life. Therefore, this review study aims to examine the association between SES and health behaviors in children and adolescents.

The findings of this review demonstrate that children and adolescents from low SES backgrounds are more likely to engaged in unhealthy behaviors, such as smoking, alcohol consumption, physical inactivity, poor dietary choices, and drug use, when compared to their peers from higher SES backgrounds. These disparities in multiple health behaviors among children and adolescents may be possibly due to low parental SES, which limits access to healthy food, physical activity, and health education. Lower parental SES also correlates with low health literacy, which may lead to a lack of awareness about the importance of healthy behaviors. These findings align with existing literature, highlighting the impact of economic constraints in low-SES households, hindering access to health-promoting resources. Limited financial resources often result in inadequate nutrition, reduced physical activity opportunities, and lower educational attainment, contributing to reduced health awareness (120–124). This knowledge and resource gap influences healthy behaviors in individuals, children, and adolescents. As a result, it is critical to emphasize the need for tailored interventions for disadvantaged children and adolescents.

In the context of SES and smoking behavior among children and adolescents, the results of this review study reported that children and adolescents with low parental SES backgrounds had heightened vulnerability to early exposure to smoking during childhood and early initiation of smoking during adolescence. This susceptibility may be attributed to a confluence of factors, including pervasive tobacco advertising, normalization of smoking within their social environments, easy access to cigarettes, limited social support for smoking cessation, heightened nicotine dependence, and the burden of stressful life circumstances. These findings substantiate the existing body of literature, which consistently demonstrates an elevated prevalence of smoking within lower SES strata, often attributed to factors such as a paucity of robust social support networks and the presence of stress-inducing lifestyles. Furthermore, children from low SES backgrounds are approximately 6.6 times more likely to be exposed to secondhand smoke within their parental residences compared to their counterparts in high- SES households (125–127). This discrepancy underscores the urgent need for targeted interventions to mitigate the adverse consequences of smoking in vulnerable populations, particularly during the critical period of life.

On the other hand, alcohol consumption was significantly higher among adolescents with high SES. These findings align with those of previous research, reinforcing the robust association between SES and adolescent alcohol consumption. Specifically, adolescents from high parental SES backgrounds exhibit increased odds of alcohol use (OR = 1.4, 95% CI = 1.19–1.78) (128). Recent research by Torchyan et al. (129) further substantiates this phenomenon, indicating a heightened likelihood of weekly alcohol consumption (OR = 1.24, 95% CI = 1.16–1.32) among high-SES adolescents when compared to their counterparts (129). This persistent pattern has been confirmed in other studies, indicating that high-SES adolescents are more likely to consume alcohol under parental supervision than their counterparts, (130). This could be explained through social and cultural activities (business meetings, and, party celebrations), the availability of alcohol at home, and the availability of pocket money to purchase alcohol (131). This review underlines early alcohol initiation among children with high SES, which is often influenced by parental drinking behavior (132). Thus, parental discretion in alcohol consumption around children is pivotal in preventing negative alcohol-related behavior (133). Therefore, this study suggests that parents should take care while drinking alcohol in front of their children to prevent them from developing bad alcohol-related behavior.

In addition, our review study found that children and adolescents with high SES were more likely to be engaged in physical exercise. These findings are consistent with previous studies and led to the conclusion that parental SES (OR = 2.73, 95% CI = 2.18, 3.42) were significantly (p < 0.05) associated with participation in indoor and outdoor physical activities by children and adolescents (134, 135). If parents had a good family income, there would be a higher chance of availability of goods and material resources at home (136). This availability of materials would make it possible to be more engaged in physical activity rather than spending more time watching television or being inactive (137). However, children and adolescents from lower parental SES backgrounds were found to participate less often in physical activity but were more often involved in sedentary behaviors. Previous studies have found that poor parental SES backgrounds were significantly associated with poor physical activity, high sedentary activity, and high screen time in children and adolescents (113, 138, 139). Moreover, there was ample evidence to suggest that more children and adolescents from deprived SES were more likely to spend more time inside the home due to a lack of a secure neighborhood, lack of green areas for sports and recreational activities, and the cost associated with physical activity (140, 141).

In relation to SES and diet (e.g., dairy products, fruit, vegetables, breakfast, soft drinks, and high-fat diet), we found that higher SES was positively associated with the consumption of breakfast, dairy products, fruit, vegetables, and a balanced diet, but negatively associated with consumption of sugar, sugar items, high- fat diet, and soft drinks. The findings of this review study are consistent with those of other studies that show that parental SES has a strong influence on children’s diet (142). These findings show that children and adolescents from high-SES families consume a healthy proportion of calories (β = 1.86, SE = 0.76) rather than high-energy foods (143). Children and adolescents from low-SES families may have few food options and may even face food insecurity and scarcity at home (144). Therefore, low parental SES may lead to low price food, high-fat diet, high- salt food, energy-dense food, and low intake of regular breakfast, dairy products, fruits, and vegetables during childhood and adolescence (144–147).

Moreover, in the context of SES and cannabis and illicit drug abuse in adolescents, there was a correlation between the consumption of cannabis and illicit drug abuse and low parental SES, poor schooling, unsafe neighborhoods, and stressful daily life events. Thus, it is important to consider how parental SES particularly affects an adolescent’s health behaviors. This review study revealed that 66.66% of the adolescents had consumed illicit drugs. These conditions increase the risk of physical, psychological, social, and emotional competence in adolescents. These findings could help to provide information about how low parental SES affects children and adolescents, and thus motivate authorities to carry out preventative activities and appropriate rules, regulations, and policies to promote healthy lifestyles in children and adolescents (148). Overall, risky health behaviors were found to be a major concern, particularly in children and adolescents with low parental SES. These conditions may increase the risk of poor health and development in childhood and adolescence. Therefore, to control these issues, an appropriate strategy helps to protect and prevent risky health behaviors in children and adolescents and gives them equal rights, services, and facilities to fight against inequalities. Hence, this study indicated that parental SES play a significant role in developing social and emotional competence and positive health outcomes in children and adolescents. Therefore, authorities and government bodies should pay more attention to the health and health behaviors of every individual, including children and adolescents, and provide support to children and adolescents, especially those with low parental SES.

5. Strength and limitations

This study comprehensively examined the association between SES and health behaviors, including protecting and impairing health behaviors in children and adolescents across the world. Moreover, this study used multiple databases and followed a structural research process that provided transparent, unbiased, and reliable information on SES and health behaviors. In summary, this study’s strengths lie in its comprehensive approach, use of multiple databases, adherence to a structured research process, and commitment to providing unbiased information. However, this study had certain limitations. The heterogeneity of the studies makes Meta-Analysis not possible. Another limitation is no risk of bias and no registration in “PROSPERO,” was remedied by that two researchers have independently assessed each article, and that a Quality Score was provided (Supplementary Table S4) as well as a “PRISMA” approach (Supplementary Table S3).

6. Conclusion

The current study revealed a robust association between low parental SES and a myriad of unhealthy behaviors (high smoking behavior, low physical exercise, illicit drug use, low consumption of fruit and vegetables, and unhealthy diet) in children and adolescents. However, alcohol consumption was more common in adolescents with a high parental SES. Based on these significant findings, this study underscores the urgent need for an appropriate intervention program that caters to the unique needs of children and adolescents from low-SES families. By implementing measures such as free all-day schools with complementary meals, free after-school activities, and supervised homework sessions, we can bridge the gaps in opportunities, capabilities, and productivity, thereby fostering healthier and more promising futures for these individuals.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

NG: conceptualization, data curation, methodology, software, formal analysis, and original drafting. GD: methodology, reviewing, editing, supervision, and validation. MR: reviewing, editing, supervision, and validation. RK: conceptualization, reviewing, editing, supervision, and validation. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

We are profoundly grateful for the invaluable support and proofreading expertise provided by the late Barbara Harmes. Our deepest respect goes out to Tricia Kelly, Rowena McGregor, Margaret Bremner, and all the dedicated librarians at USQ for their unwavering assistance in the library. Additionally, we extend our heartfelt appreciation to the School of Business at the University of Southern Queensland, Toowoomba, Australia, for creating an environment conducive to the successful completion of this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1228632/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

JBI, Joanna Briggs Institute; PA, Physical Activity; PRISMA, Preferred Reporting for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis; SES, Socioeconomic Status; SUMARI, System for the Unified Management of the Assessment and Review of Information.

References

1. Kivimäki, M, Batty, GD, Pentti, J, Shipley, MJ, Sipilä, PN, Nyberg, ST, et al. Association between socioeconomic status and the development of mental and physical health conditions in adulthood: a multi-cohort study. Lancet Public Health. (2020) 5:e140–9. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30248-8

2. Yusuf, S, Joseph, P, Rangarajan, S, Islam, S, Mente, A, Hystad, P, et al. Modifiable risk factors, cardiovascular disease, and mortality in 155 722 individuals from 21 high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries (PURE): a prospective cohort study. Lancet. (2020) 395:795–808. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32008-2

3. Qin, Z, Wang, N, Ware, RS, Sha, Y, and Xu, F. Lifestyle-related behaviors and health-related quality of life among children and adolescents in China. Health Qual Life Outcomes. (2021) 19:8. doi: 10.1186/s12955-020-01657-w

4. Macsinga, I, and Nemeti, I. The relation between explanatory style, locus of control and self-esteem in a sample of university students. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. (2012) 33:25–9. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.01.076

5. Janowski, K, Kurpas, D, Kusz, J, Mroczek, B, and Jedynak, T. Health-related behavior, profile of health locus of control and acceptance of illness in patients suffering from chronic somatic diseases. PLoS One. (2013) 8:e63920. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063920

6. Patterson, RE, Haines, PS, and Popkin, BM. Health lifestyle patterns of US adults. Prev Med. (1994) 23:453–60. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1994.1062

7. Hirdes, JP, and Forbes, WF. The importance of social relationships, socioeconomic status and health practices with respect to mortality among healthy Ontario males. J Clin Epidemiol. (1992) 45:175–82. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90010-K

8. Wiley, JA, and Camacho, TC. Life-style and future health: evidence from the Alameda County study. Prev Med. (1980) 9:1–21. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(80)90056-0

9. McGinnis, JM, and Foege, WH. Actual causes of death in the United States. JAMA. (1993) 270:2207. doi: 10.1001/jama.1993.03510180077038

10. Braveman, P, and Gottlieb, L. The social determinants of health: it's time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Rep. (2014) 129:19–31. doi: 10.1177/00333549141291S2

11. Peacock, A, Leung, J, Larney, S, Colledge, S, Hickman, M, Rehm, J, et al. Global statistics on alcohol, tobacco and illicit drug use: 2017 status report. Addiction. (2018) 113:1905–26. doi: 10.1111/add.14234

12. King, DE, Mainous, AG III, Carnemolla, M, and Everett, CJ. Adherence to healthy lifestyle habits in US adults, 1988-2006. Am J Med. (2009) 122:528–34. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.11.013

13. Guthold, R, Stevens, GA, Riley, LM, and Bull, FC. Worldwide trends in insufficient physical activity from 2001 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 358 population-based surveys with 1· 9 million participants. Lancet Glob Health. (2018) 6:e1077–86. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30357-7

14. Falci, CD. Self-esteem and mastery trajectories in high school by social class and gender. Soc Sci Res. (2011) 40:586–601. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2010.12.013

15. Twenge, JM, and Campbell, WK. Self-esteem and socioeconomic status: a meta-analytic review. Personal Soc Psychol Rev. (2002) 6:59–71. doi: 10.1207/S15327957PSPR0601_3

16. Schwartz, CE, Zhang, J, Stucky, BD, Michael, W, and Rapkin, BD. Is the link between socioeconomic status and resilience mediated by reserve-building activities: mediation analysis of web-based cross-sectional data from chronic medical illness patient panels. BMJ Open. (2019) 9:e025602. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025602

17. Zou, R, Xu, X, Hong, X, and Yuan, J. Higher socioeconomic status predicts less risk of depression in adolescence: serial mediating roles of social support and optimism. Front Psychol. (2020) 11:1955. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01955

18. Conger, RD, and Donnellan, MB. An interactionist perspective on the socioeconomic context of human development. Annu Rev Psychol. (2007) 58:175–99. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085551

19. Quon, EC, and McGrath, JJ. Subjective socioeconomic status and adolescent health: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol. (2014) 33:433–47. doi: 10.1037/a0033716

20. Pechey, R, and Monsivais, P. Socioeconomic inequalities in the healthiness of food choices: exploring the contributions of food expenditures. Prev Med. (2016) 88:203–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.04.012

21. Okamoto, S. Parental socioeconomic status and adolescent health in Japan. Sci Rep. (2021) 11:12089. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-91715-0

22. Chen, Q, Kong, Y, Gao, W, and Mo, L. Effects of socioeconomic status, parent–child relationship, and learning motivation on reading ability. Front Psychol. (2018) 9:1297. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01297

23. Charonis, A, Kyriopoulos, I-I, Spanakis, M, Zavras, D, Athanasakis, K, Pavi, E, et al. Subjective social status, social network and health disparities: empirical evidence from Greece. Int J Equity Health. (2017) 16:40. doi: 10.1186/s12939-017-0533-y

24. Belsky, J, Bell, B, Bradley, RH, Stallard, N, and Stewart-Brown, SL. Socioeconomic risk, parenting during the preschool years and child health age 6 years. Eur J Pub Health. (2007) 17:508. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckl261

25. Poulain, T, Vogel, M, Sobek, C, Hilbert, A, Körner, A, and Kiess, W. Associations between socio-economic status and child health: findings of a large German cohort study. Int J Env Res Public Health. (2019) 16:677. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16050677

26. Hasan, E. Inequalities in health care utilization for common illnesses among under five children in Bangladesh. BMC Pediatr. (2020) 20:192. doi: 10.1186/s12887-020-02109-6

27. Li, J, Wang, J, Li, JY, Qian, S, Jia, RX, Wang, YQ, et al. How do socioeconomic status relate to social relationships among adolescents: a school-based study in East China. BMC Pediatr. (2020) 20:271. doi: 10.1186/s12887-020-02175-w

28. Shaw, BA, Agahi, N, and Krause, N. Are changes in financial strain associated with changes in alcohol use and smoking among older adults? J Stud Alcohol Drugs. (2011) 72:917–25. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.917

29. Kipping, RR, Smith, M, Heron, J, Hickman, M, and Campbell, R. Multiple risk behaviour in adolescence and socio-economic status: findings from a UK birth cohort. Eur J Pub Health. (2015) 25:44–9. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cku078

30. Umeda, M, Oshio, T, and Fujii, M. The impact of the experience of childhood poverty on adult health-risk behaviors in Japan: a mediation analysis. Int J Env Res Public Health. (2015) 14:145. doi: 10.1186/s12939-015-0278-4

31. Gong, WJ, Fong, DYT, Wang, MP, Lam, TH, Chung, TWH, and Ho, SY. Increasing socioeconomic disparities in sedentary behaviors in Chinese children. BMC Public Health. (2019) 19:754. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7092-7

32. Assari, S, Caldwell, CH, and Mincy, R. Family socioeconomic status at birth and youth impulsivity at age 15; blacks’ diminished return. Children. (2018) 5:58. doi: 10.3390/children5050058

33. Assari, S, Smith, J, Mistry, R, Farokhnia, M, and Bazargan, M. Substance use among economically disadvantaged African American older adults; objective and subjective socioeconomic status. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:1826. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16101826

34. Ben-Shlomo, Y, and Kuh, D. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology: conceptual models, empirical challenges and interdisciplinary perspectives. Int J Epidemiol. (2002) 31:285–93. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.2.285

35. Due, P, Krølner, R, Rasmussen, M, Andersen, A, Trab Damsgaard, M, Graham, H, et al. Pathways and mechanisms in adolescence contribute to adult health inequalities. Scand J Public Health. (2011) 39:62. doi: 10.1177/14034948103959

36. United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund. The state of the world’s children, growing well in a changing world children, food and nutrition. (2019). Available at: https://www.unicef.org/media/60806/file/SOWC-2019.pdf (Accessed November 15, 2021).

37. United Nation. Peace, dignity and equality on a healthy planet. (2019). Available at: https://www.un.org/en/global-issues/children (Accessed October 25, 2021).

38. Reiss, F. Socioeconomic inequalities and mental health problems in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med. (2013) 90:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.04.026

39. Ross, CE, and Mirowsky, J. The interaction of personal and parental education on health. Soc Sci Med. (2011) 72:591. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.11.028

41. Hahn, RA, and Truman, BI. Education improves public health and promotes health equity. Int J Health Serv. (2015) 45:657–78. doi: 10.1177/002073141558598

42. Pearce, A, Mason, K, Fleming, K, Taylor-Robinson, D, and Whitehead, M. Reducing inequities in health across the life-course: early years, childhood and adolescence. WHO Regional Office for Europe: Denmark (2020).

43. Baker, A, Bentley, C, Carr, D, Connolly, AM, Heasman, M, Johnson, C, et al. Reducing health inequalities: system, scale and sustainability. London: Public Health England (2017).

44. World Health Organization. Situation of child and adolescent health in Europe. Copenhagen, Denmark: WHO Regional Office for Europe (2018).

45. Chen, E, Matthews, KA, and Boyce, WT. Socioeconomic differences in children's health: how and why do these relationships change with age? Psychol Bull. (2002) 128:295–329. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.2.295

46. Hanson, MD, and Chen, E. Socioeconomic status and health behaviors in adolescence: a review of the literature. J Behav Med. (2007) 30:263–85. doi: 10.1007/s10865-007-9098-3

47. Simetin, IP, Kern, J, Kuzman, M, and Pfortner, TK. Inequalities in Croatian pupils’ risk behaviors associated to socioeconomic environment at school and area level: a multilevel approach. Soc Sci Med. (2013) 98:154–61. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.09.021

48. Yannakoulia, M, Lykou, A, Kastorini, CM, Papasaranti, ES, Petralias, A, Veloudaki, A, et al. Socio-economic and lifestyle parameters associated with diet quality of children and adolescents using classification and regression tree analysis: the DIATROFI study. Public Health Nutr. (2016) 19:339–47. doi: 10.1017/S136898001500110X

49. Liu, Y, Wang, M, Tynjälä, J, Villberg, J, Lv, Y, and Kannas, L. Socioeconomic differences in adolescents’ smoking: a comparison between Finland and Beijing, China. BMC Public Health. (2016) 16:805. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3476-0

50. Melotti, R, Heron, J, Hickman, M, Macleod, J, Araya, R, and Lewis, G. Adolescent alcohol and tobacco use and early socioeconomic position: the ALSPAC birth cohort. Pediatrics. (2011) 127:e948–55. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3450

51. Krist, L, Bürger, C, Ströbele-Benschop, N, Roll, S, Lotz, F, Rieckmann, N, et al. Association of individual and neighbourhood socioeconomic status with physical activity and screen time in seventh-grade boys and girls in Berlin, Germany: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. (2017) 7:e017974. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017974

52. Obita, G, and Alkhatib, A. Disparities in the prevalence of childhood obesity-related comorbidities: a systematic review. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:923744. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.923744

53. Moore, GF, and Littlecott, HJ. School-and family-level socioeconomic status and health behaviors: multilevel analysis of a national survey in Wales, United Kingdom. J Sch Health. (2015) 85:267. doi: 10.1111/josh.12242

54. Haddad, MR, and Sarti, FM. Sociodemographic determinants of health behaviors among Brazilian adolescents: trends in physical activity and food consumption, 2009–2015. Appetite. (2020) 144:104454. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2019.104454

55. Currie, C, Zanotti, C, Morgan, A, Currie, D, De Looze, M, Roberts, C, et al. Social determinants of health and well-being among young people. Health behaviour in school-aged children (HBSC) study: international report from the 2009/2010 survey. (Health Policy for Children and Adolescents). Copenhagen, Denmark: WHO Regional Office for Europe (2012).

56. Jackson, CA, Henderson, M, Frank, JW, and Haw, SJ. An overview of prevention of multiple risk behaviour in adolescence and young adulthood. J Public Health. (2012) 34:i31–40. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdr113

57. McInnes, MD, Moher, D, Thombs, BD, McGrath, TA, Bossuyt, PM, Clifford, T, et al. Preferred reporting items for a systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy studies: the PRISMA-DTA statement. JAMA. (2018) 319:388. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.19163

58. Moher, D, Liberati, A, Tetzlaff, J, and Altman, DG, Group* P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. (2009) 151:264. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135

59. Moher, D, Shamseer, L, Clarke, M, Ghersi, D, Liberati, A, Petticrew, M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. (2015) 4:1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1

60. US Department of Health. Pediatric expertise for advisory panels - guidance for industry and FDA staff. Geretta Wood: US Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration, Center for Devices and Radiological Health (2003).

61. Johns Hopkins Medicine. The growing child: adolescent 13 to 18 years. Available at: https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/wellness-and-prevention/the-growing-child-adolescent-13-to-18-years (Accessed November 22, 2021).

62. Munn, Z, Aromataris, E, Tufanaru, C, Stern, C, Porritt, K, Farrow, J, et al. The development of software to support multiple systematic review types: the Joanna Briggs institute system for the unified management, assessment and review of information (JBI SUMARI). Int J Evid Based Healthc. (2019) 17:36–43. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000152

63. Moola, S, Munn, Z, Tufanaru, C, Aromataris, E, Sears, K, and Sfetcu, R. Chapter 7: Systematic reviews of etiology and risk In: E Aromataris and Z Munn, editors. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual : The Joanna Briggs Institute. (2017).

64. Munn, Z, Moola, S, Lisy, K, Riitano, D, and Tufanaru, C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. JBI Evid. Implement. (2015) 13:147–53. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000054

65. Piper, C. System for the unified management, assessment, and review of information (SUMARI). J Med Libr Assoc. (2019) 107:634. doi: 10.5195/jmla.2019.790

66. Dijkshoorn, AB, van Stralen, HE, Sloots, M, Schagen, SB, Visser-Meily, JM, and Schepers, VP. Prevalence of cognitive impairment and change in patients with breast cancer: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Psychooncol. (2021) 30:635–48. doi: 10.1002/pon.5623

67. Hoy, D, Brooks, P, Woolf, A, Blyth, F, March, L, Bain, C, et al. Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. J Clin Epidemiol. (2012) 65:934. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.11.014

68. Johnston, M, and Johnston, DW. Assessment and measurement issues. In comprehensive clinical psychology. M Johnston, DW Johnston, AS Bellack, and M Hersen, Eds. Elsevier Science Publishers B.V. (2001) 113–135.

69. Arnett, JJ. Emerging adulthood: a theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am Psychol. (2000) 55:469–80. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469

70. Konner, M. The evolution of childhood: relationships, emotion, mind. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press (2011).

71. Armstrong, KH, Ogg, JA, Sundman-Wheat, AN, St John Walsh, A, Armstrong, KH, Ogg, JA, et al. Early childhood development theories. New York, NY: Springer (2014).

72. Woodhead, M. Early childhood development: a question of rights. Int J Early Child. (2005) 37:79–98. doi: 10.1007/BF03168347

73. Arnett, JJ. Adolescent storm and stress, reconsidered. Am Psychol. (1999) 54:317–26. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.54.5.317

74. Adler, NE, Epel, ES, Castellazzo, G, and Ickovics, JR. Relationship of subjective and objective social status with psychological and physiological functioning: preliminary data in healthy. White Women Health Psychol. (2000) 19:586–92. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.19.6.586

75. Doshi, T, Smalls, BL, Williams, JS, Wolfman, TE, and Egede, LE. Socioeconomic status and cardiovascular risk control in adults with diabetes. Am J Med Sci. (2016) 352:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2016.03.020

76. Bradley, RH, and Corwyn, RF. Socioeconomic status and child development. Annu Rev Psychol. (2002) 53:371–99. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135233

77. Howe, LD, Galobardes, B, Matijasevich, A, Gordon, D, Johnston, D, Onwujekwe, O, et al. Measuring socio-economic position for epidemiological studies in low-and middle-income countries: a methods of measurement in epidemiology paper. Int J Epidemiol. (2012) 41:871. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys037

78. Bhusal, M, Gautam, N, Lim, A, and Tongkumchum, P. Factors associated with stillbirth among pregnant women in Nepal. J Prev Med Public Health. (2019) 52:154–60. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.18.270

79. Johansen, A, Rasmussen, S, and Madsen, M. Health behaviour among adolescents in Denmark: influence of school class and individual risk factors. Scand J Public Health. (2006) 34:32–40. doi: 10.1080/14034940510032

80. Piko, BF, and Fitzpatrick, KM. Socioeconomic status, psychosocial health and health behaviours among Hungarian adolescents. Eur J Pub Health. (2007) 17:353–60. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckl257

81. Richter, M, Erhart, M, Vereecken, CA, Zambon, A, Boyce, W, and Gabhainn, SN. The role of behavioural factors in explaining socio-economic differences in adolescent health: a multilevel study in 33 countries. Soc Sci Med. (2009) 69:396. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.023

82. Vereecken, CA, Inchley, J, Subramanian, SV, Hublet, A, and Maes, L. The relative influence of individual and contextual socio-economic status on consumption of fruit and soft drinks among adolescents in Europe. Eur J Pub Health. (2005) 15:224–32. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cki005

83. Richter, M, Leppin, A, and Gabhainn, SN. The relationship between parental socio-economic status and episodes of drunkenness among adolescents: findings from a cross-national survey. BMC Public Health. (2006) 6:289. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-289

84. Richter, M, Vereecken, CA, Boyce, W, Maes, L, Gabhainn, SN, and Currie, CE. Parental occupation, family affluence and adolescent health behaviour in 28 countries. Int J Public Health. (2009) 54:203. doi: 10.1007/s00038-009-8018-4

85. Andersen, A, Holstein, BE, and Due, P. School-related risk factors for drunkenness among adolescents: risk factors differ between socio-economic groups. Eur J Pub Health. (2007) 17:27–32. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckl071

86. Kislitsyna, O, Stickley, A, Gilmore, A, and McKee, M. The social determinants of adolescent smoking in Russia in 2004. Int J Public Health. (2010) 55:619. doi: 10.1007/s00038-010-0196-6

87. Doku, D, Koivusilta, L, Rainio, S, and Rimpela, A. Socioeconomic differences in smoking among Finnish adolescents from 1977 to 2007. J Adolesc Health. (2010) 47:479. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.03.012

88. Doku, D, Koivusilta, L, Raisamo, S, and Rimpela, A. Do socioeconomic differences in tobacco use exist also in developing countries? A study of Ghanaian adolescents. BMC Public Health. (2010) 10:758. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-758

89. Al Sabbah, H, Vereecken, C, Kolsteren, P, Abdeen, Z, and Maes, L. Food habits and physical activity patterns among Palestinian adolescents: findings from the national study of Palestinian schoolchildren (HBSC-WBG2004). Public Health Nutr. (2007) 10:739–46. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007665501

90. Mikki, N, Abdul-Rahim, HF, Shi, ZM, and Holmboe-Ottesen, G. Dietary habits of Palestinian adolescents and associated sociodemographic characteristics in Ramallah, Nablus and Hebron governorates. Public Health Nutr. (2010) 13:1419–29. doi: 10.1017/S1368980010000662

91. Andersen, A, Holstein, BE, and Due, P. Large-scale alcohol use and socioeconomic position of origin: longitudinal study from ages 15 to 19 years. Scand J Public Health. (2008) 36:326. doi: 10.1177/14034948070869

92. Pavon, DJ, Ortega, FP, Ruiz, JR, Romero, VE, Artero, EG, Urdiales, DM, et al. Socioeconomic status influences physical fitness in European adolescents independently of body fat and physical activity: the HELENA study. Nutr Hosp. (2010) 25:311. doi: 10.3305/nh.2010.25.2.4596

93. Moor, I, Rathmann, K, Lenzi, M, Pförtner, TK, Nagelhout, GE, de Looze, M, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in adolescent smoking across 35 countries: a multilevel analysis of the role of family, school and peers. Eur J Public Health. (2015) 25:457–63. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cku244

94. Hankonen, N, Heino, MT, Kujala, E, Hynynen, ST, Absetz, P, Araújo-Soares, V, et al. What explains the socioeconomic status gap in activity? Educational differences in determinants of physical activity and screentime. BMC Public Health. (2017) 17:144. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3880-5

95. Svastisalee, CM, Holstein, BE, and Due, P. Fruit and vegetable intake in adolescents: association with socioeconomic status and exposure to supermarkets and fast food outlets. J Nutr Metab. (2012) 2012:1–9. doi: 10.1155/2012/185484

96. Levin, KA, Dundas, R, Miller, M, and McCartney, G. Socioeconomic and geographic inequalities in adolescent smoking: a multilevel cross-sectional study of 15 year olds in Scotland. Soc Sci Med. (2014) 107:162–70. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.02.016

97. Park, MH, and Hwang, EH. Effects of family affluence on the health behaviors of Korean adolescents. Jpn J Nurs Sci. (2017) 14:173. doi: 10.1111/jjns.12146

98. Henriksen, PW, Rayce, SB, Melkevik, O, Due, P, and Holstein, BE. Social background, bullying, and physical inactivity: national study of 11- to 15-year-olds. Scand J Med Sci Sports. (2016) 26:1249–55. doi: 10.1111/sms.12574

99. Voráčová, J, Sigmund, E, Sigmundová, D, and Kalman, M. Family affluence and the eating habits of 11- to 15-year-old Czech adolescents: HBSC 2002 and 2014. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2016) 13:1034. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13101034

100. Melotti, R, Lewis, G, Hickman, M, Heron, J, Araya, R, and Macleod, J. Early life socio-economic position and later alcohol use: birth cohort study. Addiction. (2013) 108:516–25. doi: 10.1111/add.12018

101. Doku, D, Koivusilta, L, and Rimpela, A. Socioeconomic differences in alcohol and drug use among Ghanaian adolescents. Addict Behav. (2012) 37:357. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.11.020

102. Liu, Y, Wang, M, Tynjala, J, Villberg, J, Lv, Y, and Kannas, L. Socioeconomic inequalities in alcohol use of adolescents: the differences between China and Finland. Int J Public Health. (2013) 58:177–85. doi: 10.1007/s00038-012-0432-3

103. Lee, JO, Cho, J, Yoon, Y, Bello, MS, Khoddam, R, and Leventhal, AM. Developmental pathways from parental socioeconomic status to adolescent substance use: alternative and complementary reinforcement. J Youth Adolesc. (2018) 47:334–48. doi: 10.1007/s10964-017-0790-5

104. Simetin, IP, Kuzman, M, Franelic, IP, Pristas, I, Benjak, T, and Dezeljin, JD. Inequalities in Croatian pupils' unhealthy behaviours and health outcomes: role of school, peers and family affluence. Eur J Pub Health. (2011) 21:122–8. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckq002

105. Lazzeri, G, Azzolini, E, Pammolli, A, Simi, R, Meoni, V, and Giacchi, MV. Factors associated with unhealthy behaviours and health outcomes: a cross-sectional study among tuscan adolescents (Italy). Int J Equity Health. (2014) 13:83. doi: 10.1186/s12939-014-0083-5

106. Zaborskis, A, Lagunaite, R, Busha, R, and Lubiene, J. Trend in eating habits among Lithuanian school-aged children in context of social inequality: three cross-sectional surveys 2002, 2006 and 2010. BMC Public Health. (2012) 12:52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-52

107. Sweeting, H, and Hunt, K. Adolescent socioeconomic and school-based social status, smoking, and drinking. J Adolesc Health. (2015) 57:37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.03.020

108. Pape, H, Rossow, I, Andreas, JB, and Norstrom, T. Social class and alcohol use by youth: different drinking behaviors, different associations? J Stud Alcohol Drugs. (2018) 79:132–6. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2018.79.132

109. Pförtner, TK, Moor, I, Rathmann, K, Hublet, A, Molcho, M, Kunst, AE, et al. The association between family affluence and smoking among 15-year-old adolescents in 33 European countries, Israel and Canada: the role of national wealth. Addiction. (2015) 110:162–73. doi: 10.1111/add.12741

110. de Buhr, E, and Tannen, A. Parental health literacy and health knowledge, behaviours and outcomes in children: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health. (2020) 20:1096. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-08881-5

111. Nardone, P, Pierannunzio, D, Ciardullo, S, Lazzeri, G, Cappello, N, Spinelli, A, et al. Dietary habits among Italian adolescents and their relation to socio-demographic characteristics. Ann Ist Super. (2020) 56:504–13. doi: 10.4415/ANN_20_04_15

112. Esquius, L, Aguilar-Martínez, A, Bosque-Prous, M, González-Casals, H, Bach-Faig, A, Colillas-Malet, E, et al. Social inequalities in breakfast consumption among adolescents in Spain: the DESKcohort project. Nutrients. (2021) 13:2500. doi: 10.3390/nu13082500

113. Falese, L, Federico, B, Kunst, AE, Perelman, J, Richter, M, Rimpela, A, et al. The association between socioeconomic position and vigorous physical activity among adolescents: a cross-sectional study in six European cities. BMC Public Health. (2021) 21:866. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10791-z

114. Morgan, K, Lowthian, E, Hawkins, J, Hallingberg, B, Alhumud, M, Roberts, C, et al. Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption from 1998-2017: findings from the health behaviour in school-aged children/school health research network in Wales. PLoS One. (2021) 16:e0248847. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0248847

115. Pedroni, C, Dujeu, M, Lebacq, T, Desnouck, V, Holmberg, E, and Castetbon, K. Alcohol consumption in early adolescence: associations with sociodemographic and psychosocial factors according to gender. PLoS One. (2021) 16:e0245597. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0245597

116. Sinai, T, Axelrod, R, Shimony, T, Boaz, M, and Kaufman-Shriqui, V. Dietary patterns among adolescents are associated with growth, socioeconomic features, and health-related behaviors. Foods. (2021) 10:3054. doi: 10.3390/foods10123054

117. Yang, HM. Associations of socioeconomic status, parenting style, and grit with health behaviors in children using data from the panel study on Korean children (PSKC). Child Health Nurs Res. (2021) 27:309–16. doi: 10.4094/chnr.2021.27.4.309

118. Zaborskis, A, Grincaitė, M, Kavaliauskienė, A, and Tesler, R. Family structure and affluence in adolescent eating behaviour: a cross-national study in forty-one countries. Public Health Nutr. (2021) 24:2521. doi: 10.1017/S1368980020003584

119. Lantz, PM, House, JS, Lepkowski, JM, Williams, DR, Mero, RP, and Chen, J. Socioeconomic factors, health behaviors, and mortality: results from a nationally representative prospective study of US adults. JAMA. (1998) 279:1703. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.21.1703

120. McMaughan, DJ, Oloruntoba, O, and Smith, ML. Socioeconomic status and access to healthcare: interrelated drivers for healthy aging. Front Public Health. (2020) 8:231. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00231

121. Pampel, FC, Krueger, PM, and Denney, JT. Socioeconomic disparities in health behaviors. Annu Rev Sociol. (2010) 36:349–70. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.012809.102529

122. Fujiwara, T, Isumi, A, and Ochi, M. Pathway of the association between child poverty and low self-esteem: results from a population-based study of adolescents in Japan. Front Psychol. (2019) 10:937. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00937

123. Svendsen, MT, Bak, CK, Sørensen, K, Pelikan, J, Riddersholm, SJ, Skals, RK, et al. Associations of health literacy with socioeconomic position, health risk behavior, and health status: a large national population-based survey among Danish adults. BMC Public Health. (2020) 20:565. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-08498-8

124. Obita, G, and Alkhatib, A. Effectiveness of lifestyle nutrition and physical activity interventions for childhood obesity and associated comorbidities among children from minority ethnic groups: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients. (2023) 15:2524. doi: 10.3390/nu15112524

125. Kuntz, B, and Lampert, T. Social disparities in parental smoking and young children’s exposure to secondhand smoke at home: a time-trend analysis of repeated cross-sectional data from the German KiGGS study between 2003-2006 and 2009-2012. BMC Public Health. (2016) 16:485. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3175-x

126. Tyas, SL, and Pederson, LL. Psychosocial factors related to adolescent smoking: a critical review of the literature. Tob Control. (1998) 7:409–20. doi: 10.1136/tc.7.4.409

127. Hiscock, R, Bauld, L, Amos, A, Fidler, JA, and Munafò, M. Socioeconomic status and smoking: a review. Ann N Y Acad Sci. (2012) 1248:107–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06202.x

128. Humensky, JL. Are adolescents with high socioeconomic status more likely to engage in alcohol and illicit drug use in early adulthood? Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. (2010) 5:19. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-5-19

129. Torchyan, AA, Houkes, I, and Bosma, H. Income inequality and socioeconomic disparities in alcohol use among eastern European adolescents: a multilevel analysis. J Adolesc Health. (2023) 73:347–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2023.03.001

130. Kuppens, S, Moore, SC, Gross, V, Lowthian, E, and Siddaway, AP. The enduring effects of parental alcohol, tobacco, and drug use on child well-being: a multilevel meta-analysis. Dev Psychopathol. (2020) 32:765. doi: 10.1017/S0954579419000749

131. Patrick, ME, Wightman, P, Schoeni, RF, and Schulenberg, JE. Socioeconomic status and substance use among young adults: a comparison across constructs and drugs. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. (2012) 73:772. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.772

132. Donovan, JE, and Molina, BS. Children’s introduction to alcohol use: sips and tastes. Clin Exp Res. (2008) 32:108–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00565.x

133. Skylstad, V, Babirye, JN, Kiguli, J, Skar, AMS, Kühl, MJ, Nalugya, JS, et al. Are we overlooking alcohol use by younger children? BMJ Paediatr Open. (2022) 6:e001242. doi: 10.1136/bmjpo-2021-001242

134. Wijtzes, AI, Jansen, W, Bouthoorn, SH, Pot, N, Hofman, A, Jaddoe, VW, et al. Social inequalities in young children’s sports participation and outdoor play. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. (2014) 11:155. doi: 10.1186/s12966-014-0155-3

135. Gonzalo-Almorox, E, and Urbanos-Garrido, RM. Decomposing socio-economic inequalities in leisure-time physical inactivity: the case of Spanish children. Int J Equity Health. (2016) 15:106. doi: 10.1186/s12939-016-0394-9

136. Story, M, Neumark-Sztainer, D, and French, S. Individual and environmental influences on adolescent eating behaviors. J Am Diet Assoc. (2002) 102:S40–51. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(02)90421-9

137. Federico, B, Falese, L, and Capelli, G. Socio-economic inequalities in physical activity practice among Italian children and adolescents: a cross-sectional study. J Public Health. (2009) 17:377–84. doi: 10.1007/s10389-009-0267-4

138. Lampinen, EK, Eloranta, AM, Haapala, EA, Lindi, V, Väistö, J, Lintu, N, et al. Physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and socioeconomic status among Finnish girls and boys aged 6–8 years. Eur J Sport Sci. (2017) 17:462. doi: 10.1080/17461391.2017.1294619

139. Musić Milanović, S, Buoncristiano, M, Križan, H, Rathmes, G, Williams, J, Hyska, J, et al. Socioeconomic disparities in physical activity, sedentary behavior and sleep patterns among 6-to 9-year-old children from 24 countries in the WHO European region. Obes Rev. (2021) 22:e13209. doi: 10.1111/obr.13209

140. Moore, LV, Roux, AVD, Evenson, KR, McGinn, AP, and Brines, SJ. Availability of recreational resources in minority and low socioeconomic status areas. Am J Prev Med. (2008) 34:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.021

141. Hoffimann, E, Barros, H, and Ribeiro, AI. Socioeconomic inequalities in green space quality and accessibility—evidence from a southern European city. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2017) 14:916. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14080916

142. Agrawal, S, Kim, R, Gausman, J, Sharma, S, Sankar, R, Joe, W, et al. Socio-economic patterning of food consumption and dietary diversity among Indian children: evidence from NFHS-4. Eur J Clin Nutr. (2019) 73:1361–72. doi: 10.1038/s41430-019-0406-0

143. Leyva, RPP, Mengelkoch, S, Gassen, J, Ellis, BJ, Russell, EM, and Hill, SE. Low socioeconomic status and eating in the absence of hunger in children aged 3–14. Appetite. (2020) 154:104755. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2020.104755

144. Shinwell, J, and Defeyter, MA. Food insecurity: a constant factor in the lives of low-income families in Scotland and England. Front Public Health. (2021) 9:588254. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.588254

145. Attorp, A, Scott, JE, Yew, AC, Rhodes, RE, Barr, SI, and Naylor, PJ. Associations between socioeconomic, parental and home environment factors and fruit and vegetable consumption of children in grades five and six in British Columbia, Canada. BMC Public Health. (2014) 14:150. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-150

146. Zarnowiecki, D, Ball, K, Parletta, N, and Dollman, J. Describing socioeconomic gradients in children’s diets–does the socioeconomic indicator used matter? Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. (2014) 11:44. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-11-44

147. Vilela, S, Oliveira, A, Pinto, E, Moreira, P, Barros, H, and Lopes, C. The influence of socioeconomic factors and family context on energy-dense food consumption among 2-year-old children. Eur J Clin Nutr. (2015) 69:47–54. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2014.140

Keywords: socioeconomic status, health behavior, childhood, adolescence, systematic literature review

Citation: Gautam N, Dessie G, Rahman MM and Khanam R (2023) Socioeconomic status and health behavior in children and adolescents: a systematic literature review. Front. Public Health. 11:1228632. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1228632

Edited by:

Ahmad Alkhatib, University of Taipei, TaiwanReviewed by:

Damilola Olajide, University of Nottingham, United KingdomZeyu Wang, Guangzhou University, China

Copyright © 2023 Gautam, Dessie, Rahman and Khanam. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nirmal Gautam, nirmal.gautam@usq.edu.au; gnirmal655@gmail.com

Nirmal Gautam

Nirmal Gautam