95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

PERSPECTIVE article

Front. Public Health , 17 August 2023

Sec. Public Health Policy

Volume 11 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1208684

This article mentions parts of:

Editorial: Public and community engagement in health science research: Openings and obstacles for listening and responding in the majority world

Luchuo Engelbert Bain1,2,3*

Luchuo Engelbert Bain1,2,3* Claude Ngwayu Nkfusai3,4,5

Claude Ngwayu Nkfusai3,4,5 Prudence Nehwu Kiseh6

Prudence Nehwu Kiseh6 Oluwaseun Abdulganiyu Badru7,8

Oluwaseun Abdulganiyu Badru7,8 Lundi Anne Omam9†

Lundi Anne Omam9† Oluwafemi Atanda Adeagbo10,11

Oluwafemi Atanda Adeagbo10,11 Ikenna Desmond Ebuenyi12

Ikenna Desmond Ebuenyi12 Gift Malunga13

Gift Malunga13 Eugene Kongnyuy14

Eugene Kongnyuy14Armed conflict, natural disasters, and forced relocation are among the humanitarian problems affecting hundreds of millions of people worldwide (1, 2). Almost 80 million people have been evicted from their homes against their will (3), and one in every six children lives in or near a combat zone (4). Humanitarian emergencies may arise due to natural disasters (e.g., earthquake in Syria and Turkey) and manmade/technological disasters (e.g., Ukraine, Russia, Yemen, Syria, and South Sudan) (4). Also, humanitarian emergencies may be indicated in cases of forced displacements, as evident with the inflow of refugees into Lebanon and Bangladesh, and could be internal displacement, as seen in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia and most recently, Cameroon (2). Additionally, complex emergencies (co-occurrence of natural and manmade) may necessitate urgent humanitarian emergencies to curb immediate and future public health issues (2). Complex emergencies can occur when there is a breakdown in authority, an attack on a critical location, looting, numerous other conflict situations, or even wars (2). Some countries are coping with many crises simultaneously or protracted crises that have lasted for decades (5).

Few studies have examined the difficulties in forming solid and balanced research partnerships, despite the limited or lack of research in such settings being widely discussed over the past decade (6). Methodological constraints, ethical concerns, security issues, and logistical challenges have been identified as the main barriers to conducting research in such settings (7). Populations affected by conflict and other crises confront a variety of humanitarian issues and demands, such as population relocation, family separation, food shortages, a lack of health care, and increased susceptibility to outbreaks (8, 9). The term “health research in humanitarian crises” refers to medical research during humanitarian crises and/or research on a crisis-inflicted population (such as a population of refugees who have fled a violent conflict and have been relocated to a more peaceful area) (10). Collaboration with humanitarian organizations is crucial if research findings are to be implemented and incorporated into humanitarian policies and procedures; this is particularly important to address logistic and security difficulties (11).

Humanitarian needs are numerous and varied (1). Research in humanitarian situations is gaining traction and is now a worthwhile endeavor that permits the generation of contextually suitable knowledge to respond to the needs of those impacted by humanitarian disasters (1). Health research is necessary to guarantee that humanitarian response to disasters is evidence-based, effective, and establishes the foundation for post-crisis health planning, implementation, and evaluation (1, 4). It is believed that it is unethical to refrain from undertaking research in war and crisis circumstances, but contextual-based research is needed to help manage these crises (4). For instance, developing information and evidence about how to best care for children in emergency situations is vital (4). Children are being displaced and caught up in wars in greater numbers every year. They are the most vulnerable to climate change and environmental deterioration and frequently face famine risks (12). Children are increasingly confronted with long-lasting crises and unstable environments. Since 2010, United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) has responded to 300 humanitarian emergencies annually in around 90 countries (12).

Research can be used to understand and address problems in humanitarian settings (12, 13). Given the busy environment in which many humanitarian workers work, practitioners will be aware of these to some extent based on their experience, but given that, there is frequently little time to fully absorb the most recent conversations among practitioners, academics, policymakers, and civil society (13). This knowledge gap can be filled through research in the field, which will also assist practitioners in staying up to date with ongoing discussions about development and humanitarian aid (12). Researchers play a crucial role in translating complex information, such as observations, derived learnings from settings, research evidence, and specialized terminology, into a format that can be easily understood by practitioners and decision-makers who may not have an academic background or familiarity with academic traditions (11–13). Neglecting to utilize the knowledge gained from humanitarian contexts to enhance practice and services would be a missed opportunity (13, 14). However, it is important to emphasize that research should uphold ethical principles and avoid exploiting the vulnerability of individuals in these settings, aligning with the guidelines laid out in the Helsinki Declaration (13–15).

Humanitarian crises are made more vulnerable by inequalities and hierarchies in age, gender, social class, religion, and race because they restrict individuals from achieving their fundamental needs, accessing resources, and asserting their rights (14). Power asymmetry between research and study participants is heightened in these settings because of the several needs of individuals in these settings (15). Since the vulnerability needs to be investigated, especially in humanitarian settings, many researchers find themselves using a vulnerable population (15). For instance, research may be required to comprehend the vulnerability, address the therapy of, enhance the environment for, or alter policies in support of a specific ailment (14).

When it comes to receiving humanitarian relief, vulnerability—situation of being susceptible to physical or emotional harm—becomes a tool for human agency and a negotiating chip (16). Vulnerability can therefore influence social behaviors in a beneficial way. During humanitarian crises, one should act in ways that promote more openness and allow disadvantaged groups access to public spaces, especially when the impacted people is working together to rebuild their society (16). The condition of human interdependence, relational life, ties to others, and shared humanity is described here as vulnerability (17). Understanding the people, especially vulnerable populations, is crucial for reacting to humanitarian crises (12). Therefore, vulnerable groups should be involved in robust research that can ultimately increase their living condition and quality of life.

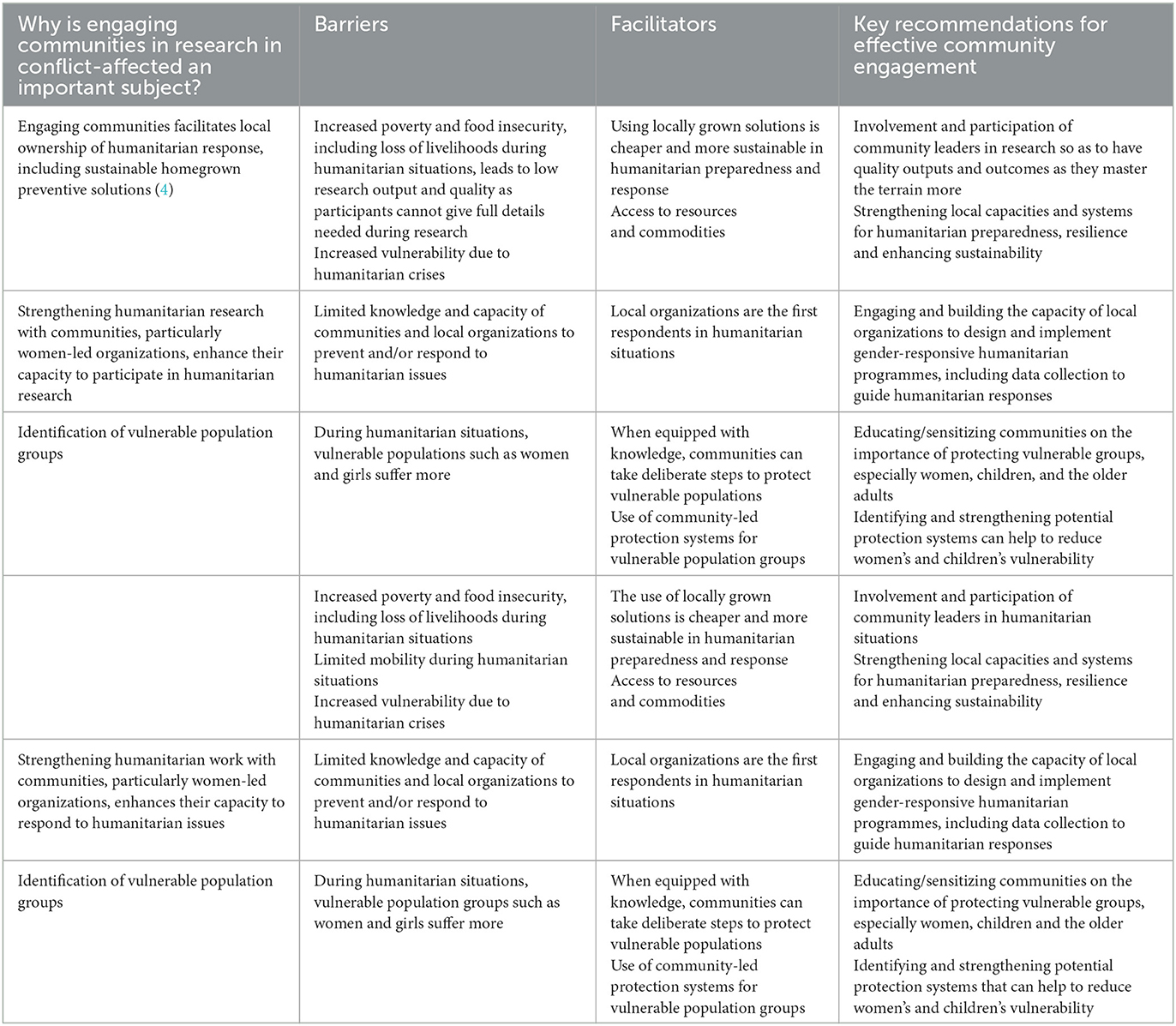

Community engagement is the act of interacting with and through groups of people who are connected by proximity, shared interests, or similar circumstances in order to address issues impacting the welfare of the populace. Community engagement is an effective tool for behavioral and environmental change to improve residents' and neighborhood's health (17–19). Partnerships and coalitions with relevant key humanitarian players are frequently employed in this process because to their capacity to mobilize resources, influence systems, alter partner relationships, and function as catalysts for changing programs, policies, and practices (18, 19). Bain et al. (20), proposed a framework for effective community engagement in research. They suggested some key elements of community-engaged research such as mutual respect, community motivation, community empowerment, and co-creation of interventions with communities, adherence to appropriate ethical principles, and gender mainstreaming. Table 1 shows barriers, facilitators and the reasons for community-engaged research in humanitarian settings as well as key recommendations.

Table 1. Community-engagement in research in humanitarian settings: barriers, facilitators and recommendations (Source: Authors experiences).

Humanitarian action is defined as any impartially carried out assistance, protection, or advocacy effort in response to a human need brought on by a complex political emergency or a natural disaster (ALNAP) (21). Delivering services to communities that are in immediate danger is what is referred to as humanitarian aid (21). There is increased interest in conducting research in humanitarian contexts, with studies ranging from population surveys to qualitative evaluations to analyse the complete range of humanitarian relief provisions (1). Medical and health policy research is scarce, and it is frequently undertaken by available international non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and humanitarian relief groups (22). Due to the possibility that this population may be particularly vulnerable to coercion and inadequate consent processes, the public health community has been working hard to uphold ethical principles like justice, autonomy, beneficence, and non-maleficence (21). Traditional ethics review is unworkable because humanitarian urgencies demand prompt assessment and management (1, 21, 22). A key element of research ethics is independent ethics evaluation before the start of a project (22). While the research could be put up alongside aid and plans to address the area's health objectives, conducting research in humanitarian situations is challenging from an ethical standpoint due to the work's time-sensitive nature and complex cultural and security factors (1). The ethical challenges arise when people are exploited or when there is no oversight in terms of the needs of the individual or actors take advantage of affected individuals, e.g., researchers may fail to get ethics approval or have unqualified or untrained people to collect data; lack of appropriate referral or debrief for people that experience psychological distress (1).

Because resource-poor communities in conflict frequently experience unstable political environments and lack adequate technical and scientific guidance to oversee research ethics, international organizations frequently employ different ethical standards that may not comply with human rights or humanitarian laws (1, 22, 23). The sort of ethical assessment will vary depending on the methodology, the specific populations involved, and whether the project entails hypothesis testing, clinical research, or routine monitoring and evaluation (22). In humanitarian healthcare, emphasizing ethical practices might be problematic if it does not consider the perception of the national healthcare staff (1). Healthcare workers believe saving as many lives as possible is good and that intervening with binding ethical codes like seeking consent may waste precious time. Taking away a victim's autonomy can be justified on the grounds that their momentary shock from the accident has impaired their ability to make decisions (23).

It is important to remember that those who occupy positions of authority and responsibility for the benefit of the general welfare also bear positive obligations, such as providing decent housing, reducing inequality, and putting preparatory measures in place to minimize suffering before and after disasters (24). According to a recently published paper by Luchuo et al., the research team, community members, and potential research volunteers must discuss any apparent ethical problems that may arise throughout the study. In-depth community engagement is increasingly seen as the key factor influencing the adoption of effective research, innovations, and interventions. Communities need to be involved in research, according to community leaders, policymakers, and funders (25).

Crisis-affected populations are especially population at risk (2). Every health research should involve affected populations and local communities because it fosters community trust, enhances research designs, and creates a channel for information distribution, leading to higher-quality studies and more useful conclusions (10). Local partners are more connected to local communities because they understand the cultural and historical context, and their involvement enhances the quality and relevance of research (2, 3). Community involvement is crucial for the success of the research's implementation and adoption of its findings after it is finished, in addition to being required ethically (26). It becomes even more important when assisting those experiencing severe trauma and agitation brought on by a humanitarian disaster (27). A key component of a comprehensive strategy for community involvement is community engagement, an increasingly important requirement for research programs (9). Unfortunately, there is little community involvement and little involvement of scholars from crisis-affected nations and regions (9). Community health workers (CHWs) can contribute critically to emergency response and preserve important services during crises by participating in research, particularly in humanitarian circumstances.

With the current COVID-19 pandemic and the West Africa Ebola outbreak, there is a rising understanding of the need of CHWs for the security and resilience of the global health system (11). There is strong evidence that CHWs can provide a variety of services locally, expand access to necessary healthcare services, and that supporting community-based initiatives can result in appreciable gains in neonatal, child, and maternal health (10). Humanitarian organizations addressing the current issue frequently collaborate with researchers conducting humanitarian studies (27). Although significant service delivery limitations may exist during acute crises and protracted times of violence and instability, CHWs can still provide services. They also frequently educate humanitarians about the safety of their region, easing aid delivery processes (11).

The importance of considering community beliefs and culture when conducting research and involving the community in the design and implementation of the study has been stressed by the Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) ethical committee (11). Health workers will be forced to evacuate during conflicts since many health facilities will be destroyed, looted, or burned down. In response, CHWs, who are typically dependable members of the community, will be sought (6, 28, 29). Despite their critical role, there may be few or no CHWs after the acute crisis phase, which fosters distrust (1).

Determining what and who the community is, as well as who has the authority to speak on its behalf, is a problem that arises in all initiatives aiming at including the community (11). Through community-based surveillance (CBS), the community can also be involved. A community member's systematic observation and reporting of incidents with public health implications is known as CBS (27). These communities are frequently employed in conflict-affected areas and communities that are topographically difficult to reach. In a study conducted in Cameroon utilizing CBS, Metuge et al. (5) discovered that it could aid in the identification of outbreaks as well as other events during crises. Improving the capability of academic and non-governmental organizational-based researchers in and from humanitarian crisis-affected countries could enhance readiness and resilience for future disasters. Community engagement is crucial (27). According to Shanks et al. (10), extensive community participation and community consultation before doing research in humanitarian situations can lessen the threats to these vulnerable groups' autonomy posed by researchers from humanitarian agencies. Although the literature on global health strongly supports community involvement in any research, there are few recommendations for overcoming obstacles in humanitarian circumstances (18).

In humanitarian circumstances, the risk that a woman would experience intimate partner or non-partner violence grows to around 1 in 3 over the course of her lifetime as the perpetrator attacker is brought closer to the victim (7). The peculiar nature of humanitarian settings increases likelihood of sexual based violence (27). Gender-based violence (GBV) is when a person is armed based on their gender expression or identity. Examples of GBV include intimate partner violence (IPV), sexual assault, sexual abuse, economic exploitation, reproductive coercion, and child marriages (8). The negative effects of gender-insensitive pandemic control measures like lockdowns during the most recent coronavirus disease (COVID-19) increased the risk of GBV by bringing victims and survivors closer to abusers, reinforcing gender roles in the home, amplifying socioeconomic stress, restricting access to reproductive and sexual healthcare, all of which were exacerbated in humanitarian circumstances (9). Access to psychosocial support, healthcare and abortion by pregnant survivors of sexual violence is limited in such settings leading to many unintended pregnancies (6). In humanitarian situations, pro-delaying-pregnancy campaigns frequently ignore issues including limited access to contraception, lack of reproductive autonomy, and, in some cases, criminalized abortions. When transactional sex is utilized to relieve socioeconomic stress, the risk of sexually transmitted illnesses caused by sexual violence may increase (27, 30, 31).

In humanitarian settings, there is the lack of quality data, and most studies are cross-sectional, which makes it extremely difficult to address causality. Most interventions implemented in these settings are inappropriate, as they are not grounded in any solid evidence (unethical). Obtaining parental consent/assent to carry out research among adolescents in humanitarian settings can be extremely difficult. It is another question knowing if true consent is easily obtainable in these settings, as persons might be intentionally or unintentionally “coerced” to participate in research (e.g., transport and time compensation, or fear of being named and not receiving services, especially if the research agenda is NGO driven). Researchers need to be particularly trained to understand the broader meanings of consent within these contexts. Ethics committees have their responsibilities to play. Indeed, the competence of research ethics committees in reviewing research protocols geared toward humanitarian settings needs to be strengthened. They can specifically seek to know how “true consent” will be sought from participants as a special requirement in the ethics applications. Conceptualization informed consent for humanitarian settings is an urgently needed but under explored area of research.

Research in humanitarian settings is essential and presents an opportunity to use setting-specific knowledge to improve practice. Hence, community engagement must be ensured through co-creating the research agenda from the inception, implementation, and evaluation of evidence-based interventions. Indeed, ownership, adaptation, and sustainability can only be achieved through effective community engagement in research in these settings. Core considerations like gender, ethics, and frameworks to adequately characterize context remain key. Ignoring effective community engagement predisposes to create new areas of inequalities, widen existing gaps, or aggravate the conditions of some already vulnerable groups. How communities in humanitarian settings should be effectively engaged in research is an important yet underexplored area of implementation science which is highly needed.

LB, CN, PN, OB, LA, OA, ID, GM, and EK were contributed equally and significantly to its creation. LB read and made the necessary edits on the manuscript. All authors reviewed the final draft and gave their approval.

LB and CN were employed by Global South Health Services and Research. PN was employed by Cameroon Baptist Convention Health Services, Bamenda, Cameroon.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

CBS, community-based surveillance; CE, community engagement; CHWs, Community Health Workers; COVID-19, coronavirus disease; GBV, gender based violence; ICRC, International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement; MSF, Médecins Sans Frontières; NGOs, Non-Governmental Organizations; RCTs, Randomized Controlled Trials.

1. Bruno W, Haar RJ. A systematic literature review of the ethics of conducting research in the humanitarian setting. Confl Health. (2020) 14:27. doi: 10.1186/s13031-020-00282-0

2. Kohrt BA, Mistry AS, Anand N, Beecroft B, Nuwayhid I. Health research in humanitarian crises: an urgent global imperative. BMJ Global Health. (2019) 4:e001870. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001870

3. Singh NS, Abrahim O, Altare C. COVID-19 in humanitarian settings: documenting and sharing context-specific programmatic experiences. Confl Health. (2020) 14:79. doi: 10.1186/s13031-020-00321-w

4. Leresche E, Truppa C, Martin C, Marnicio A, Rossi R, Zmeter C, et al. Conducting operational research in humanitarian settings: is there a shared path for humanitarians, national public health authorities and academics? Confl Health. (2020) 14:25. doi: 10.1186/s13031-020-00280-2

5. Metuge A, Omam LA, Jarman E, Njomo EO. Humanitarian led community-based surveillance: case study in Ekondo-titi, Cameroon. Confl Health. (2021) 15:17. doi: 10.1186/s13031-021-00354-9

6. Civaner MM, Vatansever K, Pala K. Ethical problems in an era where disasters have become a part of daily life: a qualitative study of healthcare workers in Turkey. PLOS ONE 12:e0174162. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0174162

7. Studying South Sudan's violence against women and girls: ethical and safety issues to take into account. Conflict and Health. Available online at: https://conflictandhealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13031-019-0239-4 (accessed February 12, 2023).

8. Meinhart M, Vahedi L, Carter SE, Poulton C, Palaku PM, Stark L. Gender-based violence and infectious disease in humanitarian settings: lessons learned from Ebola, Zika, and COVID-19 to inform syndemic policy making. Confl Health. (2021) 15:84. doi: 10.1186/s13031-021-00419-9

9. Leung MW, Yen IH, Minkler M. Community based participatory research: a promising approach for increasing epidemiology's relevance in the 21st century. Int J Epidemiol. (2004) 33:499–506. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh010

10. Shanks L, Moroni C, Rivera IC, Price D, Clementine SB, Pintaldi G. “Losing the tombola”: a case study describing the use of community consultation in designing the study protocol for a randomized controlled trial of a mental health intervention in two conflict-affected regions. BMC Med Ethics. (2015) 16:38. doi: 10.1186/s12910-015-0032-x

11. Miller NP, Ardestani FB, Dini HS, Shafique F, Zunong N. Community health workers in humanitarian settings: scoping review. J Glob Health. (2020) 10:020602. doi: 10.7189/jogh.10.020602

12. UNICEF-IRC. Humanitarian Research. UNICEF-IRC. Available online at: https://www.unicef-irc.org/research/humanitarian-research/ (accessed February 12, 2023).

13. 5 Reasons Why We Need Research in the Humanitarian Sector. HAD. (2019). Available online at: https://had-int.org/blog/5-reasons-why-we-need-research-in-the-development-humanitarian-sector/ (accessed February 12, 2023).

14. Bankoff G. Rendering the world unsafe: ‘vulnerability' as western discourse. Disasters. (2001) 25:19–35. doi: 10.1111/1467-7717.00159

15. Curchod C, Patriotta G, Cohen L, Neysen N. Working for an algorithm: power asymmetries and agency in online work settings. Adm Sci Q. (2020) 65:644–76. doi: 10.1177/0001839219867024

16. Hülssiep M, Thaler T, Fuchs S. The impact of humanitarian assistance on post-disaster social vulnerabilities: some early reflections on the Nepal earthquake in 2015. Disasters. (2021) 45:577–603. doi: 10.1111/disa.12437

17. Thorneycroft R. Problematizing and reconceptualizing ‘vulnerability' in the context of disablist violence. In:Asquith NL, Bartkowiak-Théron I, Roberts KA, , editors. Policing Encounters with Vulnerability (Berlin: Springer), 27–46. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-51228-0_2

18. Dada S, Cocoman O, Portela A, Brún AD, Bhattacharyya S, Tunçalp Ö, et al. What's in a name? Unpacking ‘Community Blank' terminology in reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health: a scoping review. BMJ Global Health. (2023) 8:e009423. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2022-009423

19. Cyril S, Smith BJ, Possamai-Inesedy A, Renzaho AMN. Exploring the role of community engagement in improving the health of disadvantaged populations: a systematic review. Glob Health Action. (2015) 8:29842. doi: 10.3402/gha.v8.29842

20. Bain LE, Akondeng C, Njamnshi WY, Mandi HE, Amu H, Njamnshi AK. Community engagement in research in sub-Saharan Africa: current practices, barriers, facilitators, ethical considerations and the role of gender - a systematic review. Pan Afr Med J. (2022) 43:152. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2022.43.152.36861

21. Slim H, Bonwick A. Protection: An ALNAP Guide for Humanitarian Agencies. Oxford: Oxfam (2006), p. 128. doi: 10.3362/9780855988869

22. Ford N, Mills EJ, Zachariah R, Upshur R. Ethics of conducting research in conflict settings. Confl Health. (2009) 3:7. doi: 10.1186/1752-1505-3-7

23. _ara.pdf. Available online at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44783/9789290218814_ara.pdf (accessed February 12, 2023).

24. Hunt MR. Establishing moral bearings: ethics and expatriate health care professionals in humanitarian work. Disasters. (2011) 35:606–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7717.2011.01232.x

25. Gaglioti AH, Werner JJ, Rust G, Fagnan LJ, Neale AV. Practice-based Research Networks (PBRNs) bridging the gaps between communities, funders, and policymakers. J Am Board Fam Med. (2016) 29:630–5. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2016.05.160080

26. Yimer G, Gebreyes W, Havelaar A, Yousuf J, McKune S, Mohammed A, et al. Community engagement and building trust to resolve ethical challenges during humanitarian crises: experience from the CAGED study. Confl Health. (2020) 14:68 doi: 10.1186/s13031-020-00313-w

27. Akondeng C, Njamnshi WY, Mandi HE, Agbor VN, Bain LE, Njamnshi AK. Community engagement in research in sub-Saharan Africa: approaches, barriers, facilitators, ethical considerations and the role of gender – a systematic review protocol. BMJ Open. (2022) 12:e057922. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-057922

28. Contreras-Urbina M, Blackwell A, Murphy M, Ellsberg M. Researching violence against women and girls in South Sudan: ethical and safety considerations and strategies. Confl Health. (2019) 13:55.

29. Zia Y, Mugo N, Ngure K, Odoyo J, Casmir E, Ayiera E, et al. Psychosocial experiences of adolescent girls and young women subsequent to an abortion in Sub-saharan Africa and globally: a systematic review. Front Reprod Health. (2021) 3:638013. doi: 10.3389/frph.2021.638013

30. Mistry AS, Kohrt BA, Beecroft B, Anand N, Nuwayhid I. Introduction to collection: confronting the challenges of health research in humanitarian crises. Confl Health. (2021) 15:38. doi: 10.1186/s13031-021-00371-8

31. Types of Disasters - Javatpoint. www.javatpoint.com. Available online at: https://www.javatpoint.com/types-of-disasters (accessed February 23, 2023).

Keywords: community engagement, research, humanitarian settings, ethical consideration, gender issues

Citation: Bain LE, Ngwayu Nkfusai C, Nehwu Kiseh P, Badru OA, Anne Omam L, Adeagbo OA, Desmond Ebuenyi I, Malunga G and Kongnyuy E (2023) Community-engagement in research in humanitarian settings. Front. Public Health 11:1208684. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1208684

Received: 19 April 2023; Accepted: 25 July 2023;

Published: 17 August 2023.

Edited by:

Nicolai Savaskan, District Office Neukölln of Berlin Neukölln, GermanyReviewed by:

Matilda Aberese-Ako, University of Health and Allied Sciences, GhanaCopyright © 2023 Bain, Ngwayu Nkfusai, Nehwu Kiseh, Badru, Anne Omam, Adeagbo, Desmond Ebuenyi, Malunga and Kongnyuy. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Luchuo Engelbert Bain, bGViYWlpbnNAZ21haWwuY29t

†Reach Out N.G.O https://www.reachoutcameroon.org

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.