95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Public Health , 17 July 2023

Sec. Disaster and Emergency Medicine

Volume 11 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1187698

Fatma Lestari1,2*

Fatma Lestari1,2* Abdul Kadir1,2

Abdul Kadir1,2 Attika Puspitasari2

Attika Puspitasari2 Suparni3

Suparni3 Oktomi Wijaya4

Oktomi Wijaya4 Herlina J. EL-Matury5

Herlina J. EL-Matury5 Duta Liana6

Duta Liana6 Riza Yosia Sunindijo7

Riza Yosia Sunindijo7 Achir Yani Hamid8

Achir Yani Hamid8 Fira Azzahra9

Fira Azzahra9Introduction: As a disaster-prone country, hospital preparedness in dealing with disasters in Indonesia is essential. This research, therefore, focuses specifically on hospital preparedness for COVID-19 in Indonesia, which is important given the indication that the pandemic will last for the foreseeable future.

Methods: During March to September 2022, a cross-sectional approach and a quantitative study was conducted in accordance with the research objective to assess hospital preparedness for the COVID-19 pandemic. This research shows the level of readiness based on the 12 components of the rapid hospital readiness checklist for COVID-19 published by the World Health Organization (WHO). Evaluators from 11 hospitals in four provinces in Indonesia (Capital Special Region of Jakarta, West Java, Special Region of Yogyakarta, and North Sumatra) filled out the form in the COVID-19 Hospital Preparedness Information system, which was developed to assess the level of hospital readiness.

Results: The results show that hospitals in Capital Special Region of Jakarta and Special Region of Yogyakarta have adequate level (≥ 80%). Meanwhile, the readiness level of hospitals in West Java and North Sumatra varies from adequate level (≥ 80%), moderate level (50% – 79%), to not ready level (≤ 50%).

Conclusion: The findings and the methods adopted in this research are valuable for policymakers and health professionals to have a holistic view of hospital preparedness for COVID-19 in Indonesia so that resources can be allocated more effectively to improve readiness.

Indonesia, known for its Ring of Fire, is a high-risk area for various disasters, including the COVID-19 pandemic. Since its discovery in late 2019 and being declared a worldwide pandemic in March 2020, COVID-19’s effects have been holistic to almost every aspect of life. Since February 2020, Indonesia has detected more than six million positive cases with more than one hundred thousand deaths (1). It is, therefore, essential to evaluate and analyze the preparedness of healthcare facilities in Indonesia.

With the emergence of new variants, healthcare services’ condition has worsened. For instance, the Omicron variant caused another urgent public health alert due to its massive mutation and rising reinfections risk (2). New variants can have detrimental impacts on multiple sectors of healthcare facilities, particularly in the prevention and treatment aspects.

Hospitals should be able to function during and after the occurrence of disasters. As the frontline entity in handling COVID-19 cases, hospitals have essential roles in providing health services for the affected population. Hospital preparedness in facing disaster has been a concern for a long time. It has been included in Hyogo Framework for Action 2005–2015 (3) and Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030 (4), highlighting the essence of safe and effective operation during and after disaster events especially in COVID-19 referral hospitals. When a hospital considered an essential asset in disasters experiences faults or structural damages, it disrupts health services that directly affect the disaster-affected population’s safety and security. Therefore, it is crucial to study and analyze the level of preparedness of COVID-19 referral hospitals in Indonesia in facing the COVID-19 pandemic, which will likely last the foreseeable future.

To assess the preparedness of COVID-19 referral hospitals, WHO has published the rapid hospital readiness checklist for COVID-19 which includes 12 holistic components that hospitals should be aware of and maintain during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Gaps within the 12 components of COVID-19 Hospital Preparedness can also be examined, resulting in improvements in the assessed hospitals.

Previous studies conducted at pediatric and adult ICUs at Cairo University (5) and 22 Eastern Mediterranean Region (6) used the questionnaire based on the Hospital Readiness Checklist for COVID-19 developed by WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean Region. It comprises 10 key components: leadership and coordination; operational support; logistics and supply management; information; communication; human resources; continuity of essential services and surge capacity; rapid identification; diagnosis; isolation and case management; and infection prevention and control (7). These studies found the intermediate level of hospital readiness at the initial outbreak of COVID-19 (5, 6).

Other studies have also used the Comprehensive Hospital Preparedness Checklist for COVID-19 published by the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (8, 9). This checklist consists of: the structure of planning and decision-making; development of a written COVID-19 plan; and elements of a COVID-19 plan (general, facility communications, consumable and durable medical equipment and supplies; identification and management of ill patients; visitors access and movement within the facility; occupational health; education and training; and healthcare services/surge capacity) (10). These studies concluded that hospitals need higher preparedness for COVID-19 services (8, 9).

Another study in Nigeria used the Hospital Readiness Checklist for COVID-19 released by WHO regional office for Europe (11). This checklist comprises the incident management system; surge capacity; infection prevention and control; case management; human resources; continuity of essential health services and patient care; surveillance: early warning and monitoring; communication; logistics and management of supplies, including pharmaceuticals; laboratory services; essential support services (12). This research adds two more components: staff welfare and availability of necessary items. This research concluded that most hospitals in Nigeria needed to be sufficiently prepared to deal with the COVID-19 outbreak (11).

Another previous study in Mazandaran Province, Iran, used a standard checklist of the Pan American World Health Organization (PAHO 2019) (13). The checklist comprises 10 components: incident management system; coordination; information management; logistics; finance and administration; detection; diagnosis; isolation; cases management; and prevention and infection control. The hospitals’ readiness to face the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak were at the good level (13).

The Director-general of Health Services of Indonesia also issued the Monitoring and Evaluation of Hospital Readiness during COVID-19 Pandemic Guidelines. The monitoring and evaluation which were done using instruments adopted from the Rapid Hospital Readiness Checklist published by World Health Organization (WHO), assessed hospitals’ readiness in governance, structure, plans, and hospital protocols in dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic (14). The checklist consists of 12 key components: leadership and incident management system; coordination and communication; surveillance and information management; risk communication and community engagement; administration, finance, and business continuity; human resources; surge capacity; continuity of essential support services; potential management; occupational health, mental health, and psychosocial support; rapid identification and diagnosis; and infection prevention and control (15).

The checklist is only available as an Excel spreadsheet and the supporting documents cannot be directly uploaded into the Excel files. Supporting documents must be submitted to District Health Office (DHO) and DHO will manually access, recapitulates, and maps hospital readiness in their respective areas. The recapitulation results are then forwarded to the Ministry of Health (16). Manually assessing checklists is time-consuming and there needs to be a feature for data saving and uploading supporting documents, which can result in lost or corrupted data (16).

Based on previous research, the COVID-19 Hospital Preparedness information system was created to assess hospital preparedness automatically. Evaluators are asked to fill out the form on this information system. This assessment form uses the 12 components from the Rapid Hospital Readiness Checklist for COVID-19 proposed by World Health Organization (WHO) (15). The checklist aims to help hospitals prepare for COVID-19 patient management by optimizing hospital capacities. The checklist takes into account a wide range of issues, including the need to provide continuing care to patients with acute or chronic illnesses; the laboratory services needed; hospitals information management; the need to train staff and other personnel; protection of healthcare workers, patients and visitors; and the needs for mental health and psychosocial support for all hospital staff (both medical and non-medical) (15). While completing the checklist, users should also consider the health system’s challenges in ensuring preparedness for other outbreaks and concurrent emergencies. The hospital score and achievement percentage are calculated automatically and displayed in tables and radar charts, making it easier for respondents to read the assessment results.

This study was conducted using a cross-sectional approach and is a quantitative study in accordance with the research objective to assess hospital preparedness for the COVID-19 pandemic. Quantitative methods are characterized by collecting numerical data, using deductive reasoning, using natural science approaches to explain social phenomena, and having an objective conception of social reality (17). In the context of this study, numerical data was obtained by calculating the hospital safety index during the situation of COVID-19 pandemic.

Four provinces in Indonesia were selected as research locations: Central Special Region of Jakarta, West Java, Special Region of Yogyakarta, and North Sumatra. These locations were chosen because they have a high level of population mobility and a high number of confirmed COVID-19 cases. In addition, hospitals in Indonesia consist of Government Hospitals, Non-Governmental/Private Hospitals, the selected sample hospitals are these both hospital which are COVID-19 Patient Referral Hospitals according to the list of COVID-19 Referral Hospitals in Indonesia. All participating hospitals had received permission from the authority to participate in this study. The sampling technique used in this study is a non-probabilistic sampling technique based on the research objectives and the permission obtained from the research locations. Moreover, there are 11 hospitals selected: Capital Special Region of Jakarta (4 Hospitals), West Java (3 Hospitals), Special Region of Yogyakarta (2 Hospitals), and North Sumatra (2 Hospitals). The study was conducted from March to September 2022.

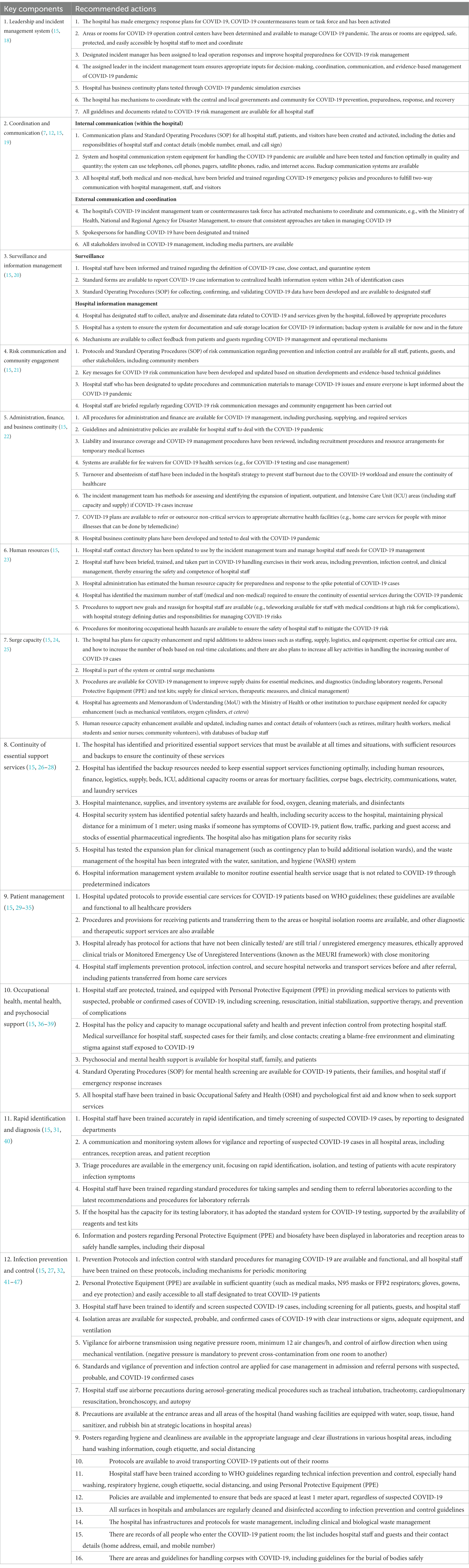

Data were collected by the evaluator team, which consists of representatives from hospital management, technical division, administrative division, finance division, and medical team (doctors and nurses). The evaluators in this study were the authors who have background education and expertise in hospital disaster management. The level and value of each element was determined through the consensus of all evaluators. Evaluators already have the skills and competencies to assess hospital preparedness for disasters, and have conducted HSI assessments in several hospitals in Indonesia. Evaluators from 11 hospitals in four provinces (Capital Special Region of Jakarta, West Java, Special Region of Yogyakarta, and North Sumatra) filled out the form in the COVID-19 Hospital Preparedness information system. As stated earlier, this form uses the 12 components from the Rapid Hospital Readiness Checklist for COVID-19 developed by WHO (13) (Table 1). This instrument includes 12 Key Components and each key component has several Recommended Actions (sub-components) as follows:

Table 1. COVID-19 hospital preparedness checklist (15).

Table 2 shows the assessment criteria to assess each component criteria.

• Not Available: there is no plan, or there is a plan but it has not started yet;

• Partially Functional: planning is already available but not yet comprehensive; or

• Fully Functional: effective and efficient planning, comply with applicable standards.

Analysis methods applied in this study was based on the Rapid hospital readiness checklist for COVID-19 to determine the hospital disaster preparedness (15). Each checklist subcomponent in the checklist is rated according to the following assessment criteria:

The Component Score is then divided by the number of sub-components in each component as in the following equation:

The Achievement Percentage was then analyzed according to the level of hospital preparedness in dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic using WHO scoring classification, which is classified into three levels as shown in Table 3 (11):

• Not ready: if the percentage of fulfillment is less than 50%;

• Moderate/Medium Readiness Level: if the percentage of fulfillment is 50–79%; or

• Adequate/High Readiness Level: if the percentage of fulfillment is more than 80%.

This study was approved under the ethical clearance Number Ket- 552/UN2.F10.D11/PPM.00.02/2023 issued by the ethics committees of the Research and Community Engagement, Faculty of Public Health, Universitas Indonesia.

After respondents filled out the form in the COVID-19 Hospital Preparedness information system, the entire data are displayed on the information system dashboard as follows:

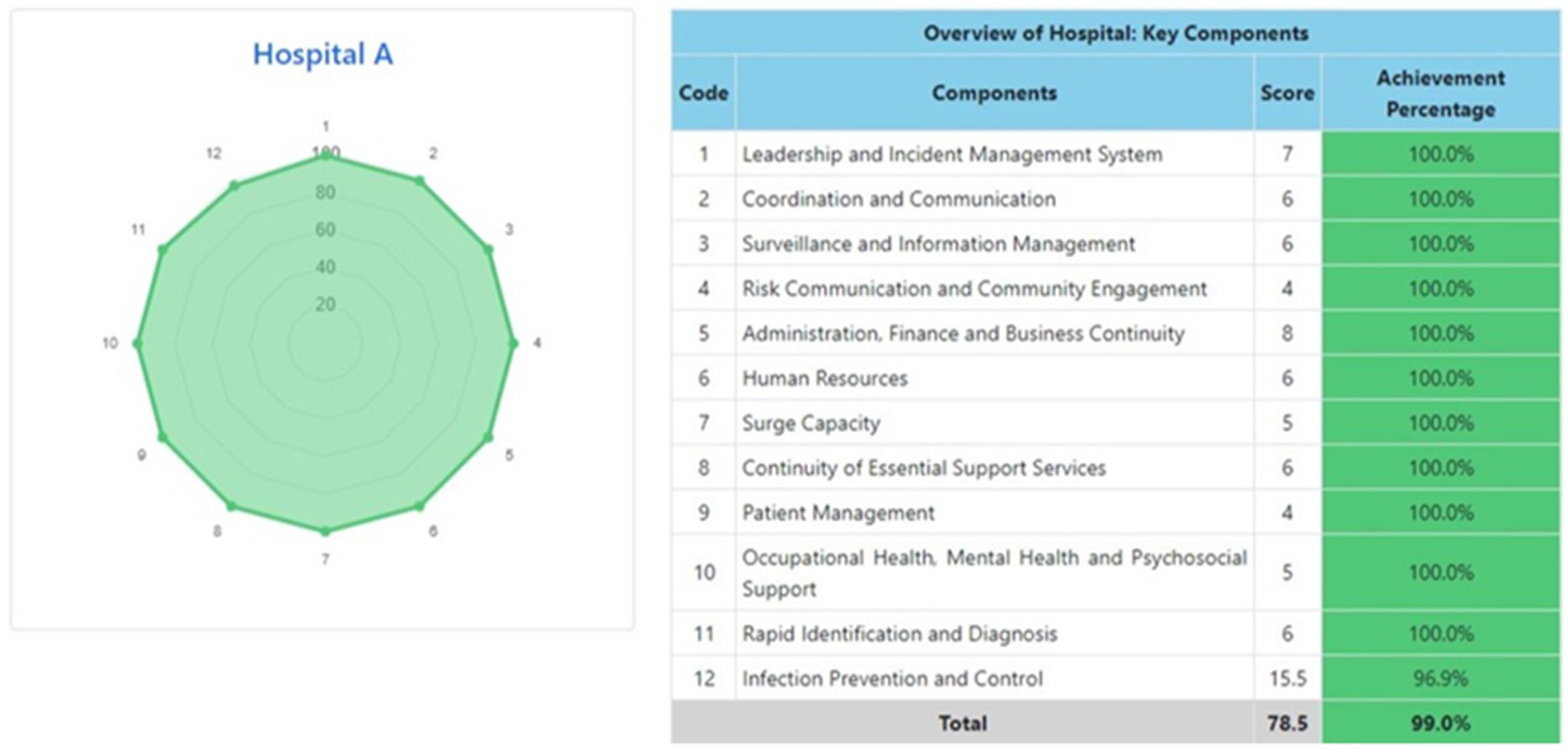

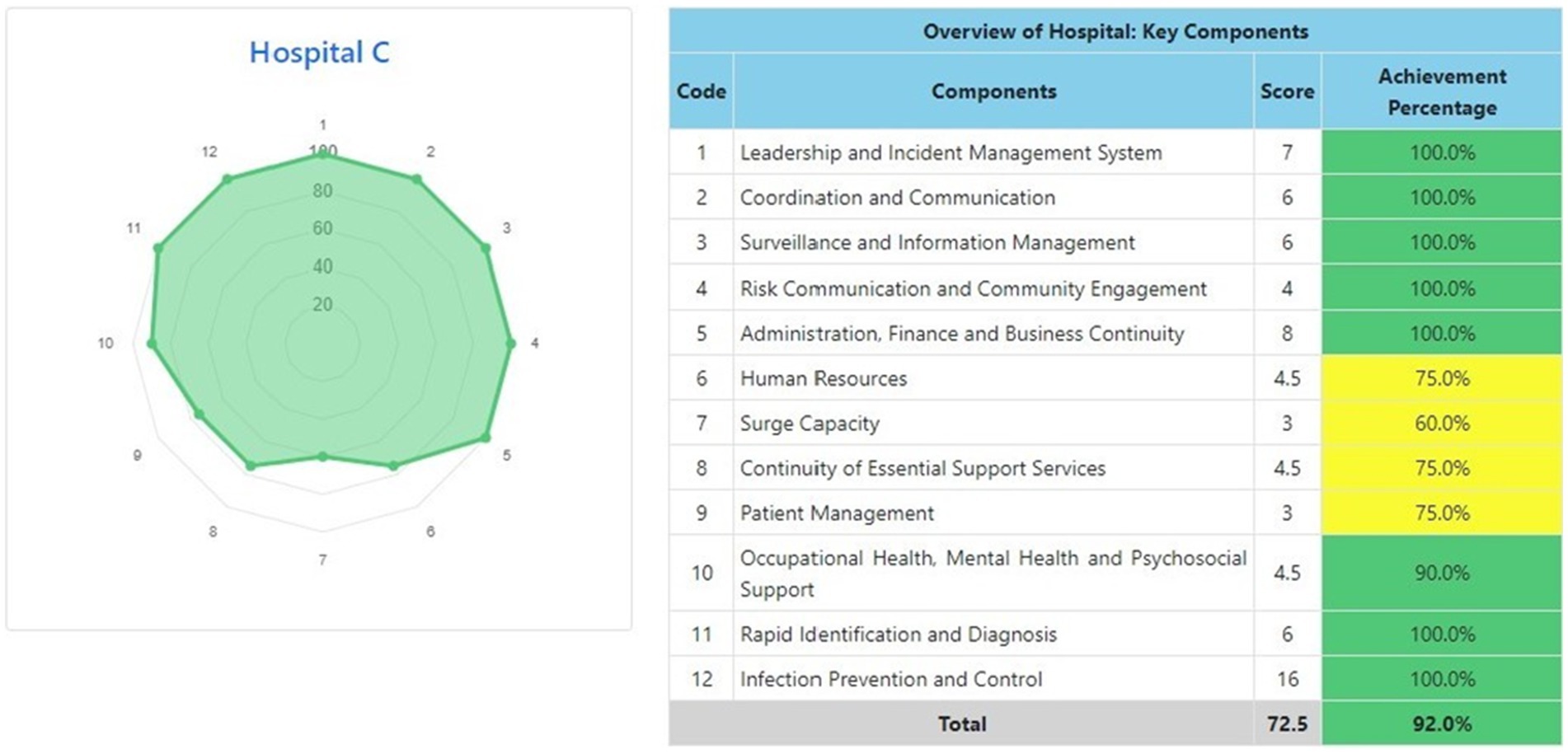

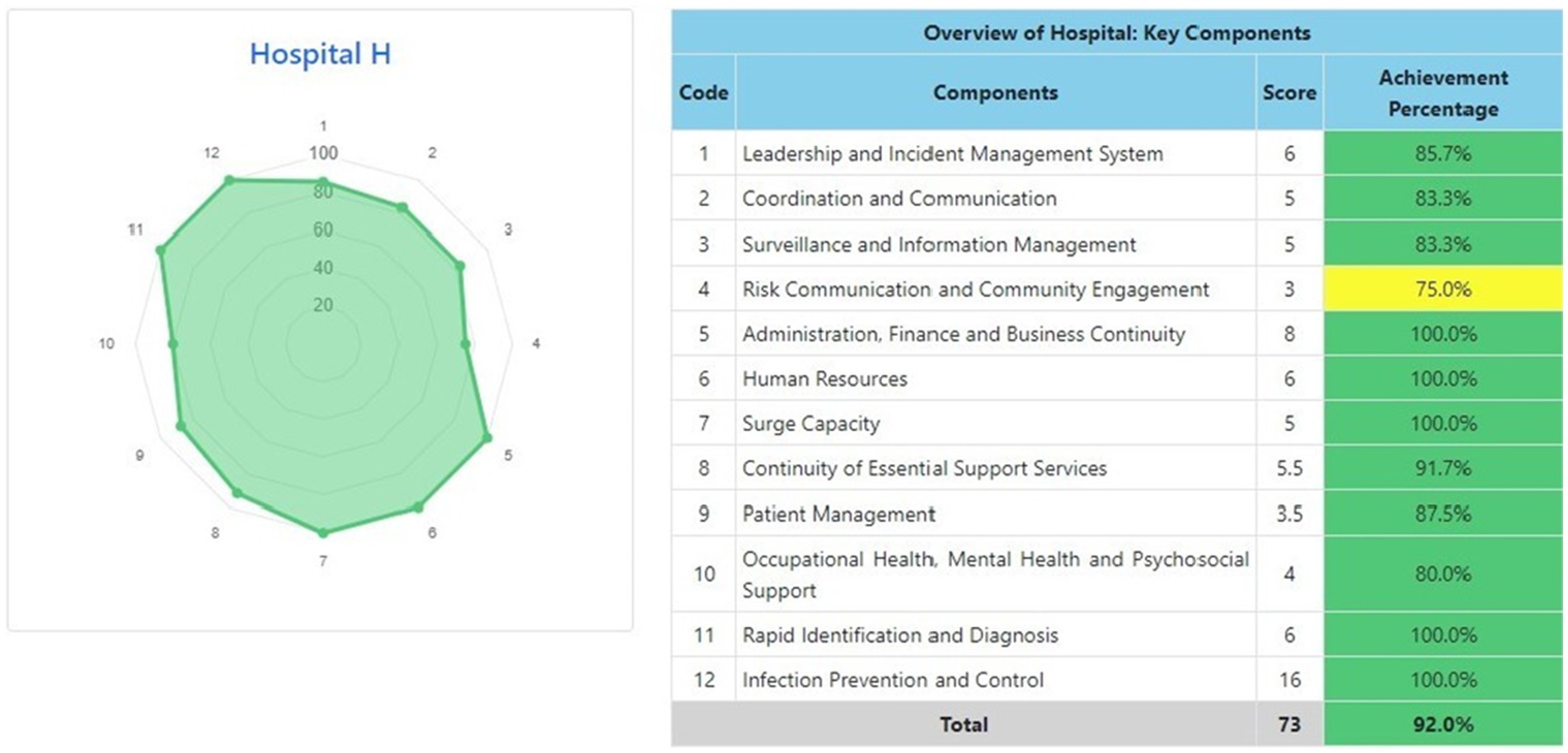

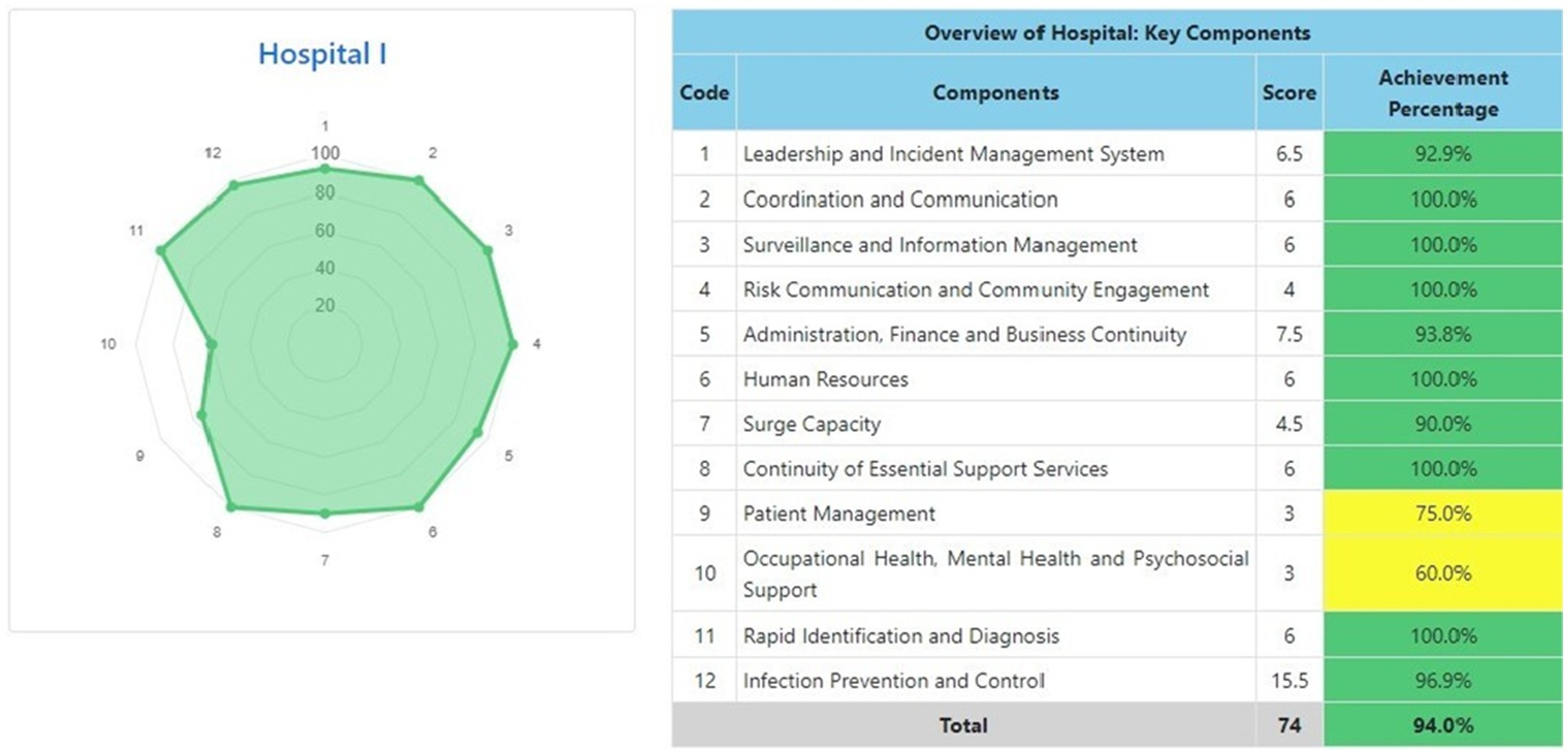

The information system dashboard (Figure 1) displays the number of provinces and hospitals that have filled out the form, the distribution areas of Hospital Preparedness for COVID-19 assessment in Indonesia, and the number of hospitals’ achievement percentage categories [Not Ready (≤50%), Moderate or Medium Readiness Level (50–79%), and Adequate or High Readiness Level (≥80%)] in each province and for the whole country. From the COVID-19 Hospital Preparedness assessment, Radar Chart, Score, and Percent Achieved can be shown in the COVID-19 Hospital Preparedness information system for 11 hospitals in four provinces [Capital Special Region of Jakarta (4 Hospitals) as shown in Figures 2–5, West Java (3 Hospitals) as shown in Figures 6–8, Special Region of Yogyakarta (2 Hospitals) as shown in Figures 9, 10, and North Sumatra (2 Hospitals) as shown in Figures 11, 12] as follows:

Figure 2. Radar chart and table of COVID-19 hospital preparedness at hospital A in capital Special Region of Jakarta.

Figure 3. Radar chart and table of COVID-19 hospital preparedness at hospital B in capital Special Region of Jakarta.

Figure 4. Radar chart and table of COVID-19 hospital preparedness at hospital C in capital Special Region of Jakarta.

Figure 5. Radar chart and table of COVID-19 hospital preparedness at hospital D in capital Special Region of Jakarta.

Figure 9. Radar chart and table of COVID-19 hospital preparedness at hospital H in Special Region of Yogyakarta.

Figure 10. Radar chart and table of COVID-19 hospital preparedness at hospital I in Special Region of Yogyakarta.

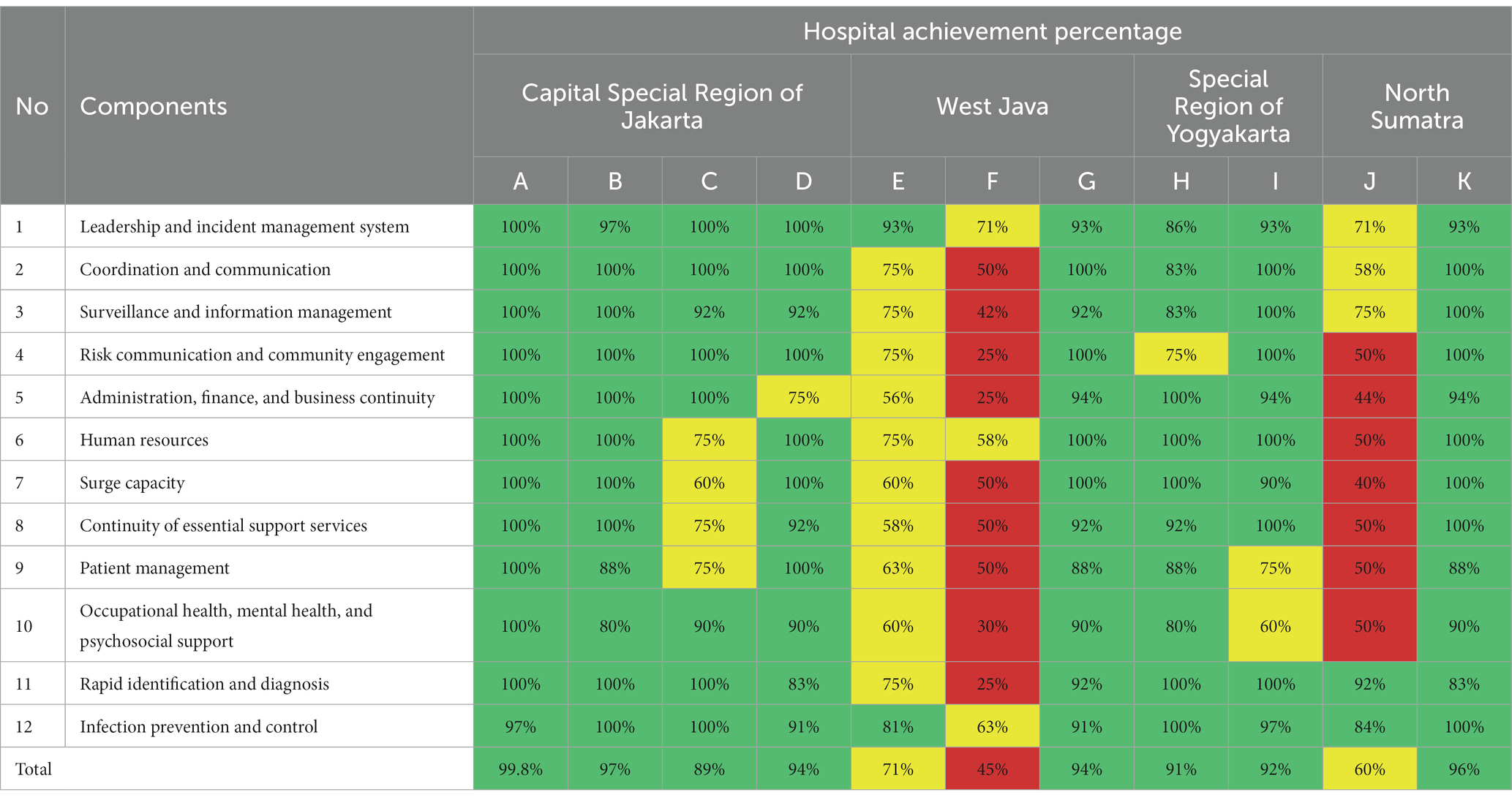

Table 4 shows that the majority of hospitals under investigation have achievement percentage in Adequate or High Readiness Level (≥80%). One hospital in West Java (Hospital E) and another hospital in North Sumatra (Hospital J) have Moderate or Medium Readiness Level (50–79%), while one hospital in West Java (Hospital F) is at Not Ready level (≤50%).

Table 4. Comparison of achievement percentage of COVID-19 hospital preparedness at 11 hospitals and classified based on the provinces: capital special region of Jakarta (Hospital A, Hospital B, Hospital C, and Hospital D); West Java (Hospital E, Hospital F, and Hospital G); Special Region of Yogyakarta (Hospital H and Hospital I); and North Sumatra (Hospital J and Hospital K).

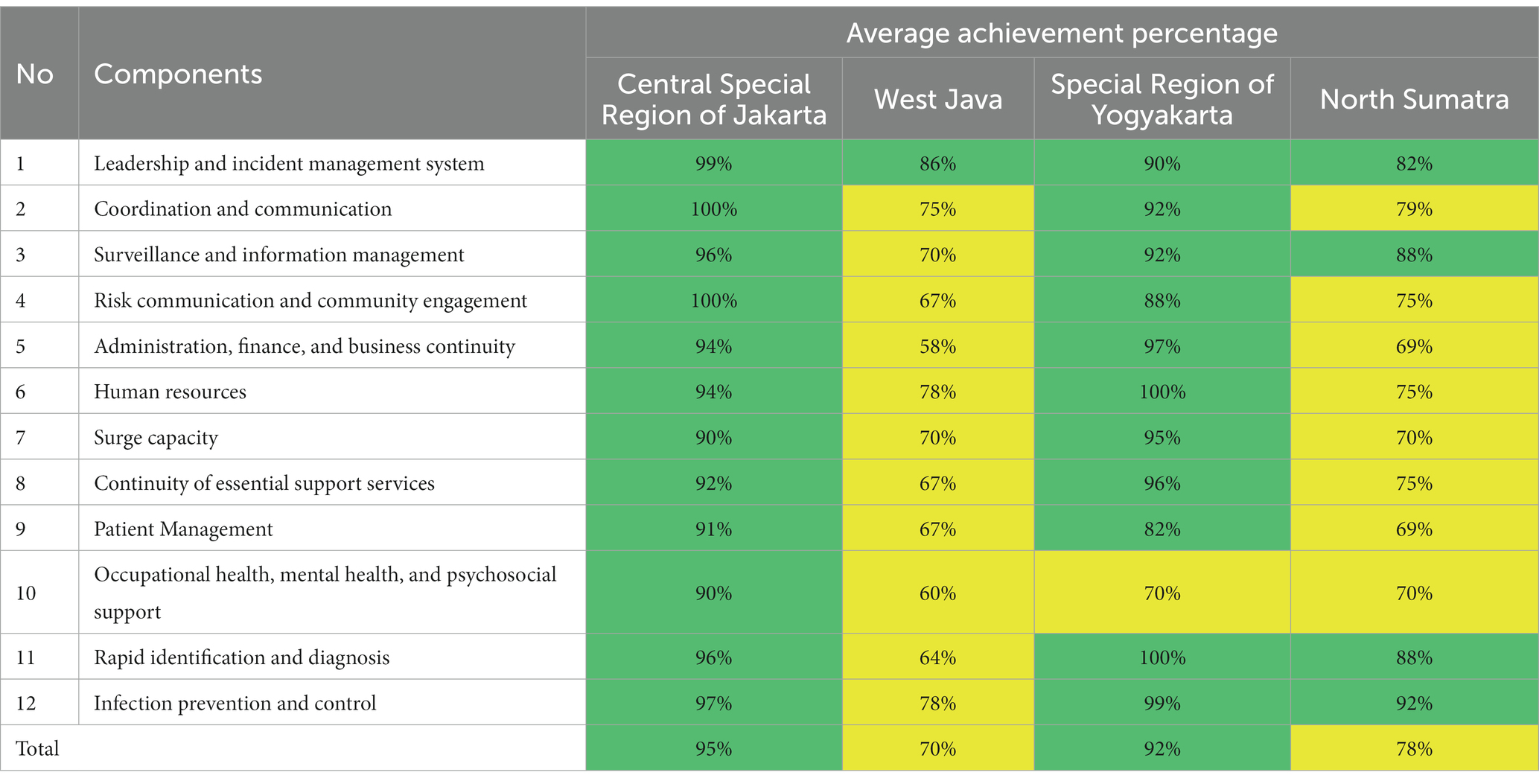

Table 5 indicates that four hospitals in Central Special Region of Jakarta and two hospitals in Special Region of Yogyakarta have average achievement percentage at Adequate or High Readiness Level (≥80%). Meanwhile, the other two provinces (West Java (three hospitals) and North Sumatra (two hospitals)) have average achievement percentage in Moderate or Medium Readiness Level (50–79%).

Table 5. Comparison of the average achievement percentage of COVID-19 hospital preparedness from 11 hospitals in four provinces in Indonesia: Capital Special Region of Jakarta, West Java, Special Region of Yogyakarta, and North Sumatra.

Incident Management System (IMS) is a standardized structure and approach adopted by WHO to administer the response to public health events and emergencies and to ensure that the organization follows best practices in emergency management (18). Good leadership and a well-functioning hospital incident management system team are fundamental for adequately administering emergency operations. Because many hospitals and other healthcare facilities already have critical management and emergency readiness plans, WHO advises adapting these plans to the core requirements for responding to the COVID-19 outbreak and maintaining the hospital’s essential routine of health services (15, 18).

This research found that the leadership and incident management system is at Adequate or High Readiness Level (≥80%) with only two hospitals at Moderate or Medium Readiness Level (50–79%), which results in a good enough. Cooperation between hospital staff and all stakeholders will create a well-functioning hospital incident management system.

This research also proposed findings that efforts to reduce the risk of morbidity and mortality from COVID-19 depend on more than just the availability of health services such as hospitals. However, the social determinants of health also influence the outcome of COVID-19, such as poverty, low-paid workers, crowded housing, and homeless people. Homeless people are at high risk of contracting the disease because they live in dense residential areas, while poor people have limited access to screening and testing. Thus, in addition to health services, the social determinants of health must be prioritized in handling a pandemic. Various improvements that can be made include financial support for low-income families, ease of access to screening and testing, and increasing access to health services for low-income people to reduce the risk of morbidity and death from COVID-19.

Appropriate communication and timely coordination are essential to ensure that data inform risk analyses and decision-making; and that there is effective collaboration, cooperation, and credence among all hospital staff and stakeholders. This component includes communication and coordination within the hospital and adequate links with local and national stakeholders, including communities and primary healthcare services (7, 12, 15, 19). Some criteria assessed in this component are divided into internal communication (within the hospital) and external communication and coordination (with other stakeholders).

In this research, the coordination and communication aspects are mostly at Adequate or High Readiness Level (≥80%). Nevertheless, three hospitals are at Moderate or Medium Readiness Level (50–79%) and Not Ready level (≤50%). Therefore, cooperation between the hospital’s countermeasures team or task force and all stakeholders is needed to increase the hospital’s internal and external communication and coordination readiness.

Global surveillance for COVID-19 is a fundamental activity needed to monitor and control pandemic outbreaks, especially in hospitals and long-term healthcare facilities. Hospital information management is equipped with surveillance aspects that are very important to increase public awareness about surveillance, emergency risks associated with public health, and the steps needed to minimize and respond to emergencies (15, 20).

Overall, this study’s surveillance and information management is at Adequate or High Readiness Level (≥80%). That means that the readiness of hospitals in the sample locations have met the WHO preparedness criteria. However, some hospitals were at Moderate or Moderate Readiness Level (50–79%) and Not Ready level (≤50%). Specifically, the following components need improvements: making SOP for collecting, confirming, and validating COVID-19 data; staff to collect, analyze and disseminate data related to COVID-19; and documentation, storage, and backup systems for COVID-19 information.

Ensuring effective risk communication and community engagement helps to limit or stop the spread of issues regarding a pandemic outbreak. It can convey precise and clear information concerning COVID-19 (15, 21). Again, although the majority of the hospitals have Adequate or High Readiness Level (≥80%), in this aspect is at some hospitals are at Moderate or Medium Readiness Level (50–79%) and even Not Ready level (≤50%). That shows that a few hospitals’ risk communication and community engagement sub-components are either partially functional or unavailable. Therefore, hospital staff and stakeholders should focus on improving risk communication protocols for infection prevention and control for all staff, patients, guests, community members, and other stakeholders; and COVID-19 risk communication should be developed and updated based on developments in the situation and evidence-based technical guidelines.

Hospital or facility administration and finance activities are essential to support systems for preventing, preparing, and responding to emergencies during the COVID-19 pandemic (15, 22). Similar to the previous dimensions, hospitals’ administration, finance, and business continuity comprehensively are generally at the Adequate or High Readiness Level (≥80%). However, some hospitals are at Moderate or Medium Readiness Level (50–79%) and Not Ready level (≤50%). This dimension needs to be enhanced by creating a strategy to prevent staff burnout due to the COVID-19 workload and ensure the continuity of healthcare; creating methods for assessing and identifying the expansion of inpatient, outpatient, and Intensive Care Unit (ICU) areas if COVID-19 cases increases; creating COVID-19 plans to refer or outsource non-critical services to appropriate alternative health facilities; and develop hospital business continuity plans to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic.

Humans are the most critical resource for preventing, preparing for, responding to, and recovering from a disease outbreak. It is essential to review staffing necessities to establish that hospitals and other healthcare facilities have the appropriate staff and the ability to deliver quality care to respond to the demands caused by the outbreak (15, 23). Resources provision for the COVID-19 control response must support the implementation of medical, laboratory, and other component responses. The provision of these resources needs to be carried out by the Central Government in collaboration with the Regional Government (48).

This research reveals that some hospitals must improve several aspects, such as having adequate staff for preparedness and response to the spike potential of COVID-19 cases, and procedures for monitoring occupational health hazards are available to ensure the safety of hospital staff to mitigate the COVID-19 risk.

Responses to this component aim to enable hospitals to develop their ability to manage a sudden or rapidly progressive surge in demand for emergency services. COVID-19 may cause a rapid and continued increase in demand. The essential services and supplies needed to resolve the COVID-19 risk include essential healthcare, equipment, and supplies necessary to maintain high-quality healthcare, especially for patients with severe COVID-19 cases. Furthermore, an increased workload should be anticipated (15, 24, 25).

In this research, some hospitals should have plans for capacity enhancement and rapid additions of COVID-19 cases; procedures for COVID-19 management to improve supply chains for essential medicines and diagnostics; and agreements and Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with the Ministry of Health or other institution to purchase equipment needed for capacity enhancement.

Besides the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak, which evolves and needs rapid scale-up of emergency preparedness and operational readiness, there are also existing requirements for essential medical and surgical care that requires a hospital’s attention (e.g., emergency medical and surgical services). Therefore, hospitals must consider the best practice to continue and sustain the continuity of their health services safely (e.g., in terms of supplies, logistics, and pharmacy services) while addressing COVID-19 case management needs (15, 26–28).

In this research, certain hospitals should identify and prioritize essential support services that must be available at all times and situations with sufficient resources and backups to ensure the continuity of these services; maintenance, supplies, and inventory systems are available; security system has identified potential health and safety hazards and mitigation plans for security risks; has the expansion plan for clinical management and the waste management of the hospital integrated with the water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) system; and information management system to monitor routine essential health service usage that is not related to COVID-19 through predetermined indicators.

Patient management consists of admission or referral, triage, diagnosis, treatment, patient flow and tracking; discharge and follow-up; support services management, pharmacy services, logistics, and supply functions. The purposes are to ensure that the hospital’s patient management system remains safe, effective, and efficient and that the hospital can manage safe and effective patient management when normal circumstances and COVID-19 pandemic demands increase the hospital’s resources and capacities. When dealing with a new infectious disease outbreak, hospitals should ensure they have space for triage and isolating COVID-19 suspected, possible, and confirmed cases (15, 29–35, 49).

In this research, some hospitals should update protocols to provide essential care services for COVID-19 patients based on WHO guidelines; have procedures and provisions for receiving patients and transferring them to hospital isolation rooms or other diagnostic and therapeutic support services; have protocols for actions that have not been clinically tested, are still trial or unregistered emergency measures, ethically approved clinical trials or Monitored Emergency Use of Unregistered Interventions (MEURI framework); and hospital staff have to implement prevention protocol, infection control, transport services before and after referral, including patients transferred from homecare services.

Occupational health, mental health, and psychosocial support services are necessary to decrease the detrimental psychological and social impacts of COVID-19 on hospital patients, staff, families, and communities. WHO has published guidelines regarding assessing and managing risks to healthcare staff. Additionally, several publications review the mental health and psychosocial issues associated with the pandemic (15, 36–39).

Certain hospitals, particularly outside the Capital Special Region of Jakarta, should protect, train, and equip their staff with Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) in providing medical services to patients with suspected, probable, or confirmed cases of COVID-19; have the policy and capacity to manage occupational safety and health and prevent infection control from protecting hospital staff; have psychosocial and mental health support for hospital staff, family, and patients; and all hospital staff have been trained in essential Occupational Safety and Health (OSH) and psychological first aid.

The rapid identification and diagnosis laboratory of COVID-19 cases will ensure a logical and effective chain of events during case management. In principle, the triage process identifies patients who need treatment and immediate medical intervention or may need to access certain health facilities based on the patient’s clinical condition (14).

The result indicates that some hospitals should train their staff regarding rapid identification accurately and timely screening of suspected COVID-19 cases; have communication and monitoring systems for vigilance and reporting of suspected COVID-19 cases in all hospital areas; have triage procedures in the emergency unit, focusing on rapid identification, isolation, and testing of patients with acute respiratory infection symptoms; and train hospital staff concerning standard procedures for taking samples and sending them to referral laboratories. Laboratory services must be provided to support the hospital’s preparedness, operational readiness, and response activities, such as surveillance, infection prevention and control (IPC), and patient management; all of these must be accomplished promptly and efficiently (15, 31, 40).

Based on the Regulation of the Minister of Health of the Republic of Indonesia number 27 of 2017 concerning Infection Prevention and Control, Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) is an effort to prevent and minimize the occurrence of infections in patients, staff, visitors, and the community around healthcare facilities (48). IPC is essential to minimize the COVID-19 transmission risk to hospital staff, other patients, close contacts, and visitors. Prevent or breaking the chain of COVID-19 infection transmission in healthcare facilities can be achieved by applying the principles of COVID-19 prevention and transmission control risk, which consists of isolation precautions (standard and transmission precautions), administrative controls, education and training; PPI in pre-referral health facilities; and IPC to burial corpses (15, 50).

In this research, only one hospital is at Not Ready level (≤50%), while the rest are at Adequate or High Readiness Level (≥80%). Cooperation between hospital staff, the countermeasure task force team, and all stakeholders is key to ensuring hospital infection prevention and control.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, the sample size of selected hospital was quite small (only 11 hospitals), which delivered from four provinces in Indonesia. Further study from another countries is required to be conducted in order to assess the hospital preparedness situations. Secondly, since the study focus on the hospital preparedness for COVID-19 situation, the selected hospital was not considered the characteristic of employees. It was based on the hospital that is the referral for Covid-19 patients. Thirdly, the data collection was very limited and done through online focus group discussion and interviews, therefore it is strongly recommended for further study to conduct a direct survey. Fourthly, the instrument used for study is based on WHO checklist which proposed in COVID-19 situation, which the first study conducted in Indonesia. The study in these areas is strongly recommended to examine especially in pre-COVID-19 situation and post COVID-19 as well as Hospital preparedness for preventing pandemic in future. Lastly, further statistical analysis such multivariate analysis method should be considered to identify the most significant variables that affect Hospital preparedness.

Hospital preparedness for COVID-19 needs to become a concern for assessment and evaluation. Limited research, especially in Indonesia, related to hospital preparedness for COVID-19 makes this research necessary. Based on the analysis, Central Special Region of Jakarta (Hospital A and Hospital B), West Java (Hospital G), and North Sumatra (Hospital K) with overall scores at Adequate or High Readiness Level (≥80%) for 12 components of Rapid hospital readiness checklist for COVID-19. Despite some elements are still found to have a poor level of preparedness, especially Hospital E in West Java was at Moderate or Medium Readiness Level (50–79%) and Hospital F in West Java was at Not Ready level (≤50%) in almost all aspects such as coordination and communication; surveillance and information management; risk communication and community engagement; administration, finance and business continuity; human resources; surge capacity; continuity of essential support services; patient management; occupational health, mental health, and psychosocial support; and rapid identification and diagnosis.

The assessment results also demonstrate that the hospital preparedness in the Central Special Region of Jakarta and Special Region of Yogyakarta tend to be better if compared with the other two provinces (West Java and North Sumatra) in some aspects: coordination and communication; risk communication and community engagement; administration, finance and business continuity; human resources; surge capacity; continuity of essential support services; and patient management.

The results of this research can be used to inform hospital staff, countermeasures team or task force, and relevant stakeholders regarding COVID-19 hospital awareness and preparedness then appropriate policies and practice guidelines can be implemented to improve their capabilities of facing this pandemic outbreak and other future pandemic-prone diseases. This study has limitations regarding the small number of provinces and hospitals which have filled out forms in COVID-19 Hospital Preparedness information system. Further studies are needed to describe the overall hospital preparedness for COVID-19 in Indonesia. It is also envisioned that the dashboard can be expanded over time by assessing hospital preparedness against various disaster events.

The data analyzed in this study is subject to the following licenses/restrictions: The datasets utilized and/or analyzed during the present study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to ZmF0bWFAdWkuYWMuaWQ=.

FL and AK: conceptualization, methodology, and funding acquisition. AP: software, validation, and visualization. OW, S, HE-M, and DL: formal analysis. FA: investigation and project administration. DL: resources. AYH: data curation. FL, AK, OW, HE-M, and S: writing—original draft preparation. RS: writing—review and editing. FL: supervision. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This study is funded by Directorate of Research and Development, Universitas Indonesia, Under Hibah PUTI Q1 (Grant No. NKB-462/UN2.RST/HKP.05.00/2022).

The authors would like to thank the Disaster Risk and Reduction Center Universitas Indonesia (DRRC UI) for the supports in completing this study.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. World Health Organization (WHO). Indonesia: WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard with Vaccination Data [Internet]. World Health Organization (WHO). (2023) Available at: https://covid19.who.int/region/searo/country/id (Accessed March 13, 2023).

2. Khandia, R, Singhal, S, Alqahtani, T, Kamal, MA, el-Shall, NA, Nainu, F, et al. Emergence of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron (B.1.1.529) variant, salient features, high global health concerns and strategies to counter it amid ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Environ Res. (2022) 209:112816. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2022.112816

3. International Strategy for Disaster Reduction. Hygo Framework for Action 2005-2015: Building the Resilience of Nations and Communities to Disasters. (2005). [Internet]. Available from: https://www.unisdr.org/2005/wcdr/intergover/official-doc/L-docs/Hyogo-framework-for-action-english.pdf (Accessed March 14, 2023).

4. UNDRR. Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015 - 2030. (2015). Available from: https://www.undrr.org/publication/sendai-framework-disaster-risk-reduction-2015-2030 (Accessed April 1, 2023).

5. Labib, JR, Kamal, S, Salem, MR, El Desouky, ED, and Mahmoud, AT. Hospital preparedness for critical care during COVID-19 pandemic: exploratory cross-sectional study. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. (2020) 8:429–32. doi: 10.3889/oamjms.2020.5466

6. Ravaghi, H, Naidoo, V, Mataria, A, and Khalil, M. Hospitals early challenges and interventions combatting COVID-19 in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. PLoS One. (2022) 17:e0268386. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0268386

7. WHO. Hospital readiness checklist for COVID-19 Interim document-Version 1. (2020). Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/333972 (Accessed March 13, 2023).

8. Qarawi, ATA, Ng, SJ, Gad, A, Luu, MN, al-Ahdal, TMA, Sharma, A, et al. Study protocol for a global survey: awareness and preparedness of hospital staff against coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. Front Public Health. (2021) 9:580427. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.580427

9. Dewi, K, Chalidyanto, D, and Laksono, AD. Hospital Preparedness for COVID-19 in Indonesia: A case study in three types hospital. Indian J For Med Toxicol. (2021) 15:3496. doi: 10.37506/ijfmt.v15i3.15842

10. CDC. Comprehensive Hospital Preparedness Checklist for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). (2020). Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/downloads/HCW_Checklist_508.pdf or https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/facility-planning-operations.html (Accessed March 16, 2023).

11. Ogoina, D, Mahmood, D, Oyeyemi, AS, Okoye, OC, Kwaghe, V, Habib, Z, et al. A national survey of hospital readiness during the COVID-19 pandemic in Nigeria. PLoS One. 16:e0257567. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0257567

12. WHO. Hospital readiness checklist for COVID-19 interim version February 24 2020. (2020). Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/333972 (Accessed March 17, 2023).

13. Hosseini, SH, Tabari, YS, Assadi, T, Ghasemihamedani, F, and HabibiSaravi, R. Hospitals Readiness in Response to COVID-19 Pandemic in Mazandaran Province, Iran 2020. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci. (2020) 31:71–81.

14. Direktorat Jenderal Pelayanan Kesehatan. Hospital services guideline during the COVID-19 pandemic: technical instructions for hospital services during the adaptation period for the new normal. (2020). Available from: https://www.covidlawlab.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Indonesia_2020.11.09_Notification_Technical-Guidelines-for-Hospital-Services-in-the-Adaptation-Period-for-New-Habits_IN.pdf (Accessed March 16, 2023).

15. WHO. Rapid hospital readiness checklist for COVID-19. (2020). Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/337039 (Accessed March 16, 2023).

16. Dhamanti, I, Rachman, T, Nurhaida, I, and Muhamad, R. Challenges in implementing the WHO hospital readiness checklist for the COVID-19 pandemic in indonesian hospitals: a qualitative study. J Multidiscip Healthc. (2022) 15:1395–402. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S362422

17. Ahmad, S, Wasim, S, Irfan, S, Gogoi, S, Srivastava, A, and Farheen, Z. Qualitative v/s, Quantitative research- a summarized review. J Evid Based Med Healthc. (2019) 6:2828–32. doi: 10.18410/jebmh/2019/587

18. WHO. Emergency response framework (ERF), second edition. (2017). [Internet]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241512299 (Accessed March 18, 2023).

19. PAHO. Hospital Readiness checklist for COVID-19 Interim document - Version 5. February 10, 2020. (2020). [Internet]. Available from: https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/52402?show=full (Accessed March 16, 2023).

20. WHO. Global surveillance for COVID-19 caused by human infection with COVID-19 virus Interim guidance 20 March 2020. (2020). [Internet]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331506 (Accessed March 16, 2023).

21. WHO. Risk communication and community engagement readiness and response to coronavirus disease (COVID-19): interim guidance, 19 March 2020. (2020). [Internet]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/risk-communication-and-community-engagement-readiness-and-initial-response-for-novel-coronaviruses (Accessed March 18, 2023).

22. WHO. Home care for patients with COVID-19 presenting with mild symptoms and management of their contacts: interim guidance, 17 March 2020. (2020). [Internet]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331473 (Accessed March 17, 2023).

23. WHO. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak: rights, roles and responsibilities of health workers, including key considerations for occupational safety and health: interim guidance, 19 March 2020. (2020). [Internet]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331510 (Accessed March 15, 2023).

24. Simulation exercise. [Internet]. (2023). Available at: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/training/simulation-exercise (Accessed March 15, 2023).

25. WHO. Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection (SARI) when COVID-19 disease is suspected: interim guidance, 13 March 2020 (2020). [Internet]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331446 (Accessed March 16, 2023).

26. WHO. COVID-19: operational guidance for maintaining essential health services during an outbreak: interim guidance, 25 March 2020. (2020). [Internet]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331561 (Accessed March 16, 2023).

27. WHO. Infection prevention and control for the safe management of a dead body in the context of COVID-19: interim guidance, 24 March 2020. (2020). [Internet]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/infection-prevention-and-control-for-the-safe-management-of-a-dead-body-in-the-context-of-covid-19-interim-guidance (Accessed March 14, 2023).

28. WHO. Water, sanitation, hygiene and waste management for COVID-19: technical brief, 03 March 2020. (2020). [Internet]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331305 (Accessed March 14, 2023).

29. WHO. Service availability and readiness assessment (SARA): an annual monitoring system for service delivery: reference manual, Version 2.2, Revised July 2015. (2014). [Internet]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/149025 (Accessed March 11, 2023).

30. Case management [Internet]. (2022). Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance/patient-management (Accessed March 15, 2023).

31. WHO. Operational considerations for case management of COVID-19 in health facility and community: interim guidance, 19 March 2020. (2020). [Internet]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/10665-331492 (Accessed March 11, 2023).

32. WHO. Severe acute respiratory infections treatment centre: practical manual to set up and manage a SARI treatment centre and a SARI screening facility in health care facilities. (2020). [Internet]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/10665-331603 (Accessed March 11, 2023).

33. WHO. Laboratory testing for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in suspected human cases: interim guidance, 2 March 2020. (2020). [Internet]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331329 (Accessed March 11, 2023).

34. WHO. Guidance for managing ethical issues in infectious disease outbreaks (2016). [Internet]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/250580 (Accessed March 11, 2023).

35. PAHO. Prehospital Emergency Medical System Readiness: Checklist for COVID-19. Draft document, Version 2.3. (2020). Available from: https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/52169 (Accessed March 9, 2023).

36. WHO. Risk assessment and management of exposure of health care workers in the context of COVID-19: interim guidance, (2020). [Internet]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331496 (Accessed March 19, 2023).

37. Interim Briefing Note Addressing Mental Health and Psychosocial Aspects of COVID-19 Outbreak | IASC [Internet]. (2020). Available from: https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/iasc-reference-group-mental-health-and-psychosocial-support-emergency-settings/interim-briefing (Accessed March 15, 2023).

38. ILO. HealthWISE Work Improvement in Health Services: Action Manual. (2014). [Internet]. Available from: https://www.ilo.org/sector/Resources/training-materials/WCMS_250540/lang--en/index.htm (Accessed March 11, 2023).

39. Xiang, YT, Yang, Y, Li, W, Zhang, L, Zhang, Q, Cheung, T, et al. Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed. Lancet Psychiatry. (2020) 7:228–9. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30046-8

40. Rational use of personal protective equipment (PPE) for coronavirus disease (COVID-19): interim guidance. (2020) (Accessed March 19, 2020).

41. Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) in the context of COVID-19 [Internet]. Available at: https://openwho.org/courses/COVID-19-IPC-EN (March 15, 2023).

42. van Doremalen, N, Bushmaker, T, Morris, DH, Holbrook, MG, Gamble, A, Williamson, BN, et al. Aerosol and Surface Stability of SARS-CoV-2 as Compared with SARS-CoV-1. N Engl J Med. (2020) 382:1564–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2004973

43. IRC. Best Practices for Environmental Cleaning in Healthcare Facilities: in Resource-Limited Setting. (2019). Available from: https://www.ircwash.org/resources/best-practices-environmental-cleaning-health-care-facilities-resource-limited-settings (Accessed March 16, 2023).

44. WHO. Safe management of wastes from health-care activities: a summary. (2017). [Internet]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/259491 (Accessed March 12, 2023).

45. WHO. Infection prevention and control during health care when coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is suspected or confirmed. (2021). [Internet]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-IPC-2021.1 (Accessed March 3, 2023).

46. WHO. Preventing and managing COVID-19 across long-term care services: Policy brief, 24 July 2020. (2020). [Internet]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Policy_Brief-Long-term_Care-2020.1 (Accessed February 26, 2023).

47. WHO. WASH and infection prevention and control in health-care facilities. (2020). [Internet]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/documents/wash-and-infection-prevention-and-control-health-care-facilities (Accessed March 11, 2023).

48. Regulation of the Minister of Health of Republic Indonesia number 27 of 2017 concerning Infection Prevention and Control. (2017). [Internet]. Available from: http://hukor.kemkes.go.id/uploads/produk_hukum/PMK_No._27_ttg_Pedoman_Pencegahan_dan_Pengendalian_Infeksi_di_FASYANKES_.pdf (Accessed March 11, 2023).

49. Country & Technical Guidance - Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) [Internet]. (2020). Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance (Accessed March 14, 2023).

50. WHO. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) prevention and control guidelines 5th revision. (2020). [Internet]. Available from: https://www.who.int/indonesia/news/detail/11-08-2020-disseminating-the-revised-national-covid-19-guidelines (Accessed March 11, 2023).

Keywords: hospital readiness checklist for COVID-19, hospital preparedness, hospital readiness, information system, Indonesia

Citation: Lestari F, Kadir A, Puspitasari A, Suparni, Wijaya O, EL-Matury HJ, Liana D, Sunindijo RY, Yani Hamid A and Azzahra F (2023) Hospital preparedness for COVID-19 in Indonesia. Front. Public Health. 11:1187698. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1187698

Received: 16 March 2023; Accepted: 26 June 2023;

Published: 17 July 2023.

Edited by:

Rafael Castro Delgado, Health Research Institute of Asturias (ISPA), SpainReviewed by:

Ozden Gokdemir, İzmir University of Economics, TürkiyeCopyright © 2023 Lestari, Kadir, Puspitasari, Suparni, Wijaya, EL-Matury, Liana, Sunindijo, Yani Hamid and Azzahra. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Fatma Lestari, ZmF0bWFAdWkuYWMuaWQ=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.