- 1School of Public Health, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, United States

- 2Center for Community Health and Aging, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, United States

- 3Center for Health Equity and Evaluation Research, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, United States

- 4Foundation for Social Connection, Washington, DC, United States

- 5Coalition to End Social Isolation and Loneliness, Washington, DC, United States

- 6Global Initiative on Loneliness and Connection, Washington, DC, United States

- 7Healthy Places by Design, Carrboro, NC, United States

- 8The Human Flourishing Program, The Institute for Quantitative Social Sciences, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, United States

- 9Academic Research Centers, NORC at the University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, United States

- 10Departments of Psychology and Neuroscience, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT, United States

- 11Division of Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States

1. Introduction

Social disconnectedness is a complex and multi-faceted public health issue impacting individuals of all ages across the life-course. Social disconnectedness is characterized by the interrelated concepts of social isolation and loneliness stemming from limited contact or meaningful relationships with others, or related perceptions thereof. Older adults may be particularly at risk for social disconnectedness because they are more likely to live alone, experience loss or changes in their social networks (e.g., spouse, family, friends), and have chronic conditions and impairments (e.g., mobility, sensory, cognitive). In the United States, about 25% of older adults are considered to be socially isolated (1), which is an objective measure indicating the absence of a social network or the lack of social contact (2). Further, anywhere between 20% to 40% of older adults report moderate to severe loneliness (3–5), which can be described as the subjective, negative feeling from inadequate meaningful connections (6) or a lack of connection to other people despite the desire for more, or more satisfying, social relationships (7). People who feel they do not belong to majority social groups because of their gender identity, race, ethnicity, religion, language, or sexual orientation are at increased risk for social isolation, as are people living in rural areas, people with disabilities, immigrants, and individuals and families with financial struggles (8–11). The ramifications of social disconnectedness are vast and span poor physical (e.g., cardiovascular disease, stroke) (12–14) and mental (e.g., depression, anxiety) health outcomes, cognitive decline, risky health behaviors (e.g., substance use, physical inactivity, suicide), and all-cause mortality (2, 15–17).

Social connectedness is recognized as a core dimension of individual flourishing, health, wellbeing, and survival (18, 19). The longest longitudinal study of adults, the 75-year Harvard Study of Adult Development, found that an individual's satisfaction with their relationships was the greatest predictor of happiness and health (20, 21). Social connectedness has also been shown to be a key indicator of healthy aging later in life. Socially connected older adults are the core of an optimally functioning society (22). Living in socially connected communities can help older adults to thrive because it can increase neighborhood safety, strengthen resilience during societal crisis, encourage volunteerism, improve access to services and supports, and facilitate trust (23). Cognitive science demonstrates that friendships are critical for shared social pursuits of truth and that chronic forms of social isolation and loneliness contribute to distrust in social and political institutions (24).

While the consequences of social disconnectedness can be detrimental to the health, they may be symptoms of a fragmented and siloed society that obstructs and complicates efforts to build social connectedness for older adults (25). In this context, the purposes of this article are to: (a) describe societal-level challenges that foster social disconnectedness; and (b) provide opportunities and solutions to strengthen community capacity to foster social connectedness among older adults. This article brings together experts from public health, medicine, psychology, public policy, social sciences, and healthy community design to provide diverse perspectives through a unified lens to guide research, practice, and policy to drive community-level action.

2. Societal disconnectedness

Social connectedness is the degree to which an individual or population falls along the continuum of social connection, which includes (a) connections to others via the existence of relationships and their roles; (b) a sense of connection that results from actual or perceived support or inclusion; and c) the sense of connection to others that is based on positive relationship qualities (26, 27). Social connectedness is comprised of various interpersonal bonds (e.g., marriages, families, friendships)- bonds with strong (spouses, family, friends) and weak ties (infrequent, arms-length relationships), and various forms of participation in community life including memberships in civic, religious, social, and/or political organizations and networks that share common missions, interests, values, and beliefs (28). However, at times community systems and infrastructures can limit opportunities for interaction and participation, which can be detrimental to social connectedness.

In the context of public health, communities are “a group of people with diverse characteristics who are linked by social ties, share common perspectives, and engage in joint action in geographical locations or settings” (29). Communities are comprised of interrelated systems that provide services and programs to improve and maintain older adults' health and wellness. To support mental and physical health, these networks can facilitate the initiation, maintenance, and strength of interpersonal bonds and participation in community life. Spanning the aging services network, public health system, and healthcare sector, each organization serving older adults has a unique mission, set of offerings, populations served, political ideologies, partnerships, regulating agencies, and funding sources. This uniqueness gives organizations autonomy in their operations and pursuits of societal impact. However, this may also lead to “silos” that result from financial and logistical barriers that limit coordinated, integrated service provision across sectors. Furthermore, systems have been designed to oppress and isolate people through policies such as redlining and highway development that disproportionately impact communities of color. This disenfranchisement and fragmentation within systems can breed distrust for government leaders and inefficiencies to reach, engage, serve, support, and treat older adults, which can ultimately disrupt the continuity of care and service delivery and reduce older adults' community participation and social connectedness.

Older adults residing within siloed and fragmented communities are at increased risk of being socially disconnected and not having their social needs met, especially those who experience poorer health, functional or sensory impairments, live alone, or experience additional marginalization (2, 8–11). Because older adults interact with many organizations across sectors for different reasons, these organizations share older adult clients and the responsibility to offer an integrated, coordinated set of “touch points” to address social isolation, loneliness, and general disconnectedness. Misaligned funding streams, competing demands and priorities, and general lack of uniformity across organizations and silos hinder community advancement and the ability to mitigate the health-related consequences of social disconnectedness. However, opportunities exist to bridge silos and narrow societal chasms through purposive collective action that advances research, practice, and policy.

3. Opportunities and solutions to strengthen societal and community capacity for social connectedness

A systems approach is needed to reduce societal silos, unify communities, and promote social connectedness among older adults. In this section, we offer nine opportunities and solutions to strengthen and unite communities to improve their cross-sector capacity to meet the social needs of older adults.

3.1. Raise awareness about social disconnectedness and advance it as a national priority

The prevalence of social isolation and loneliness among older adults warrants increased recognition as priority public health issues (27, 28). Dedicated awareness-raising efforts are needed to elevate recognition of the risks for, consequences of, and solutions to social disconnectedness among individuals, organizations, and policy makers. Tailored messaging and communication strategies are needed to garner support and buy-in from various stakeholders (30). Although social isolation and loneliness are often discussed and addressed through an individual-level lens, social disconnectedness is also a community-level issue, strongly rooted in social determinants of health framing as well as service and treatment inequities. More efforts are needed to complement and expand the visibility of existing initiatives that are raising awareness about social disconnectedness among older adults and other populations across the life-course [e.g., U.S. Administration for Community Living (ACL)'s Commit to Connect (31), Foundation for Social Connection's Action Forum (32)].

3.2. Create a common nomenclature for use across sectors

Similar concepts are phrased and defined differently across disciplines, organizations, and community sectors. As such, it is important to identify commonly used terms and work within communities to establish a consistent terminology surrounding social disconnectedness. Creating a common nomenclature can reduce misunderstandings and facilitate efficiency during collaborations and information exchanges (33). For example, a uniform cross-sector taxonomy may be helpful to define risk factors and criteria, services and programs, and statistical methodologies and approaches.

3.3. Develop uniform screening across organizations and sectors

Because social disconnectedness can encompass many constructs [e.g., social isolation, loneliness, social networks, and social supports (2)], organizations commonly use different measures, scales, and screening tools to identify risk among older adults. Measures are commonly selected because of the mission of the organization, the clients they serve, and/or the requirements of their funding sources. However, the use of non-standardized measures (or non-standardized cut-points to indicate risk) can hinder a community's ability to document the prevalence of social disconnectedness or demonstrate collective impact when services and programs are offered through different organizations. It is beneficial to develop and routinely administer uniform and robust measures, which can be aligned with larger national and global initiatives for comparative purposes [e.g., inclusion of uniform social isolation and loneliness me asures collected by the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) (34) and National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) (35)].

3.4. Strengthen cross-sectoral referrals and community navigation

Each organization provides their own set of services and programs that address social disconnectedness. As such, the social needs of older adults may not be entirely addressed by any one organization. To ensure continuity of care for older adults across sectors, organizations should communicate about their respective services and resources (36) and establish seamless inter-agency referral criteria and processes. To enhance these referral systems, organizations should utilize trusted community navigators (e.g., community health workers, promotors, social workers, case managers) who understand specific cultural norms and needs, are familiar with community offerings, and can link older adults to appropriate services and programs. Social prescribing models may help older adults identify and access services and supports (37, 38). Further, technological advances may automate these referral and linkage processes and foster innovative community-clinical-industry partnerships (39, 40).

3.5. Establish and expand evidence about effective programs and services

Despite a growing recognition of the importance to address social disconnectedness, there are limited evidence-based programs and services shown to reduce social isolation and loneliness. Many of the interventions that have been tested are focused on individual interventions such as therapy, and less data exist about implementation and evaluation of community-wide or society wide interventions, social infrastructure, or policies. More also needs to be known about how inter-generational initiatives and various living arrangements affect loneliness and social isolation and influence interpersonal bonds and community participation (41). Additional efforts are needed to conduct controlled and pragmatic trials to assess the effectiveness of interventions to address social disconnectedness. It will be critical for such trials to integrate systems thinking approaches and consider the societal context within which trials are conducted to ensure aspects of equity, efficacy, replicability, and scalability can be addressed (42). To complement new interventions that specifically address social disconnectedness, existing interventions developed for other purposes should also be evaluated to determine their indirect benefits on social disconnectedness (43–45).

3.6. Improve community places and spaces to promote mobility and connectivity

Older adults with impairments (e.g., physical, sensory, cognitive), limited financial resources, or unreliable transportation may have additional difficulty accessing community resources and each other. As such, it is important to consider the built environment and physical infrastructure within a community to promote community-level mobility and connectivity. Inclusive public spaces are critical for all people to interact with one other, gain trust in community leaders, experience cultural activities, and gain a sense of belonging. Libraries, public parks, community gardens, community centers, and other types of social infrastructure are multifaceted and can improve social connectedness while providing many other benefits to individuals and the community (46). All community-level solutions should be developed with the input and participation of community members to ensure their needs, culture, and interests are included, especially those who are marginalized. Connectivity may be especially difficult in rural communities where resources are more geographically dispersed, which highlights the benefits of delivering services in easily accessible locations that are commonly frequented by older adults (e.g., faith-based organizations, senior centers, healthcare offices, commercial businesses) (47). For example, older residents have better connectivity to shared communal life when their built environment integrates civic, religious, and retail buildings with affordable housing (48).

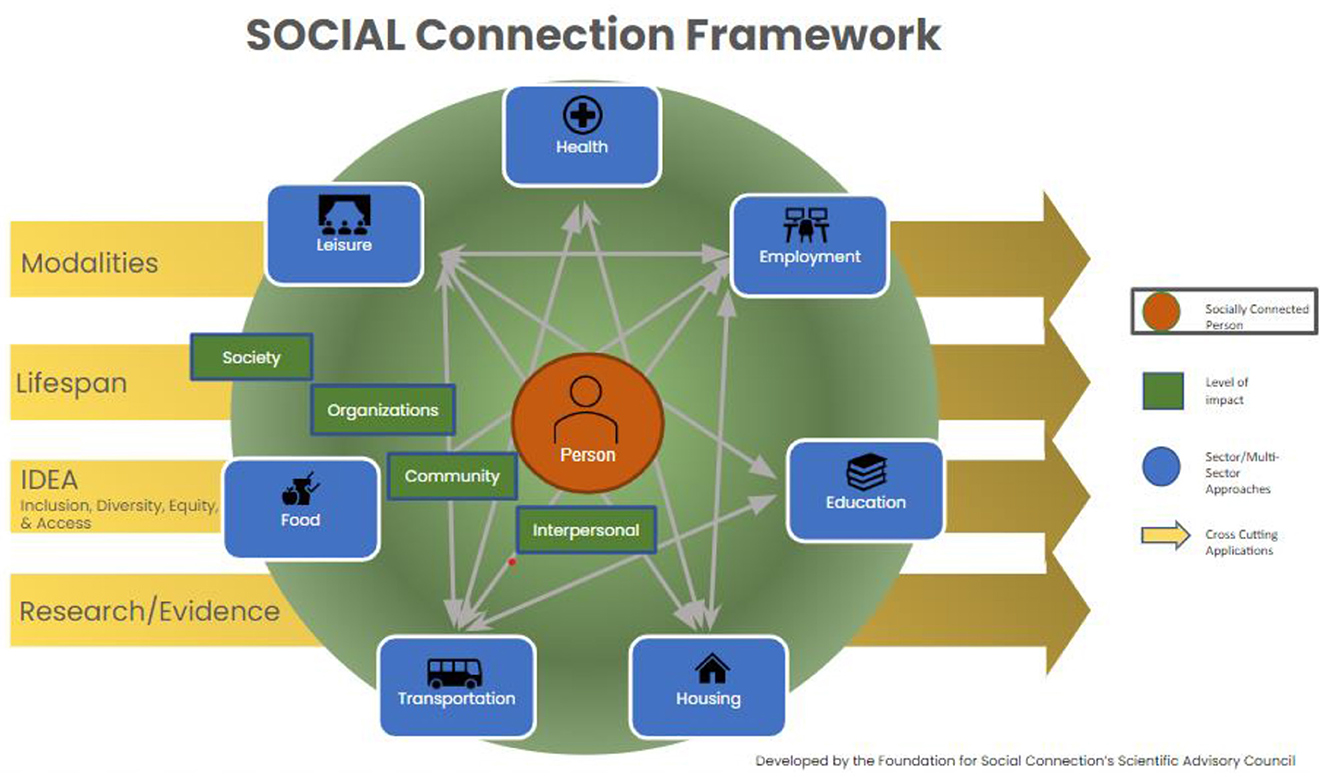

3.7. Adopt unified, systems-level models

Collective planning across organizations and sectors is often contingent on utilizing a common framework. Such frameworks can help organizations better understand the roles and offerings of other organizations within a community, identify leverage points for collaboration, duplicative services, and service gaps which require additional resources or partnership. An example of an inclusive framework is the Systems approach Of Cross-sector Integration and Action across the Lifespan (SOCIAL) Framework (see Figure 1), which was developed by the Foundation for Social Connection's Scientific Advisory Council (SAC) “to facilitate and accelerate multi-stakeholder actions to reduce social isolation and loneliness, increase social connectedness, and identify opportunities for impact and gaps for additional research and solutions” (27).

Figure 1. The Systems approach Of Cross-sector Integration and Action across the Lifespan (SOCIAL) Framework (27).

3.8. Share and leverage funding and data

Funding for research and service provision has become increasingly scarce and competitive in recent years. While organizations rely on their own sources of funding to operate, leveraged funding through strategic partnerships can expand the scope and reach of services beyond the capabilities of any single organization. Public and private funders should consider ways to incentivize community wide collaboration, paying special attention to diversity, equity, and inclusion, to build social connectedness and community participation. Additionally, because each organization collects and generates its own data, efforts are recommended to share and leverage data across organizations and community sectors to alleviate data collection burdens, optimize understanding about older adult clients, and demonstrate collective impact. For example, Health Information Exchanges have been shown to facilitate community partnerships and identify cost savings for programs and services provided to residents (49–52). Another example is the Gravity Project, which defines social determinants of health information so it can be documented in and exchanged across disparate digital health and human service platforms to facilitate payment for social risk data collection and intervention activities (53).

3.9. Build inclusive, action-oriented strategic alliances

The formation of community-level coalitions, action alliances, and task forces can unify communities for a common mission. As such, these multi-organization, cross-sector entities can effectively incorporate each of the strategies mentioned above (e.g., raise awareness, create common nomenclature, adopt uniform screening, strengthen referrals, leverage funding). Examples of successful, model entities include the U.S. Coalition to End Social Isolation and Loneliness (CESIL) (54), Building Resilient and Inclusive Communities (BRIC) (55), U.K. Campaign to End Loneliness (56), Australian Ending Loneliness Together (57), and Global Initiative on Loneliness and Connection (GILC) (58).

4. Conclusion

Social isolation and loneliness among older adults are growing concerns in many communities across the world. These issues can have a significant impact on an older person's physical and mental health, leading to a decline in overall well-being. To meaningfully combat these problems, communities must recognize collaborative opportunities to address system injustices, transcend sectoral silos, synergize, and leverage efforts for the collective benefit of older adult connectedness.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

TC was supported by the National Institute on Aging K23AG075191, the Johns Hopkins University Center for Innovative Medicine Human Aging Project as a Caryl & George Bernstein Scholar, and the Robert and Jane Meyerhoff Endowed Professorship.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Foundation for Social Connection's Scientific Advisory Council (SAC) for their leadership, innovation and dedication to address social isolation and loneliness. SAC Members include (listed alphabetically): Juan Albertorio, Thomas Cudjoe, Nicole Ellison, Louise Hawkley, Julianne Holt-Lunstad, Eden Litt, Matthew Pantell, Carla Perissinotto, Harry Reis, Matthew Lee Smith, and Mark Van Ryzin. We also thank the following organizations for their financial support, technical assistance, and prioritization of initiatives to unify communities and facilitate social connectedness: Administration for Community Living (ACL), National Association for Chronic Disease Directors (NACDD), Office of the Surgeon General, USAging, and members of the Coalition to End Social Isolation and Loneliness (CESIL).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Cudjoe TK, Roth DL, Szanton SL, Wolff JL, Boyd CM, Thorpe RJ Jr. The epidemiology of social isolation: National health and aging trends study. J Gerontol: Series B. (2020) 75:107-13. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gby037

2. National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine. Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults: Opportunities for the Health Care System. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. (2020).

3. Anderson GO, Thayer CE. Loneliness and Social Connections: A National Survey of Adults 45 and Older. Washington, DC: AARP Foundation. (2018).

4. Perissinotto CM, Cenzer IS, Covinsky KE. Loneliness in older persons: A predictor of functional decline and death. Arch Intern Med. (2012) 172:1078–83. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.1993

5. Hawkley LC, Kozloski M, Wong J. A Profile of Social Connectedness in Older Adults. (2017). Available online at: https://connect2affect.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/A-Profile-of-Social-Connectedness.pdf (accessed February 25, 2023).

6. Prohaska T, Burholt V, Burns A, Golden J, Hawkley L, Lawlor B, et al. Consensus statement: loneliness in older adults, the 21st century social determinant of health?. BMJ Open. (2020) 10:e034967. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034967

7. Badcock JC, Holt-Lunstad J, Garcia E, Bombaci P, Lim MH. Position Statement: Addressing Social Isolation Loneliness the Power of Human Connection. Global INITIATIVE on Loneliness Connection (GILC) (2022). Available online at: https://www.gilc.global/general-6

8. Kearns A, Whitley E, Tannahill C, Ellaway A. Loneliness, social relations and health and wellbeing in deprived communities. Psychol Health Med. (2015) 20:332–44. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2014.940354

9. Scharf T, Phillipson C, Smith AE. Social exclusion of older people in deprived urban communities of England. Eur J Ageing. (2005) 2:76–87. doi: 10.1007/s10433-005-0025-6

10. Algren MH, Ekholm O, Nielsen L, Ersbøll AK, Bak CK, Andersen PT. Social isolation, loneliness, socioeconomic status, and health-risk behaviour in deprived neighbourhoods in Denmark: a cross-sectional study. SSM Popul Health. (2020) 10:100546. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2020.100546

11. Tapia-Muñoz T, Staudinger UM, Allel K, Steptoe A, Miranda-Castillo C, Medina JT, et al. Income inequality and its relationship with loneliness prevalence: A cross-sectional study among older adults in the US and 16 European countries. (2022) PLoS ONE. 17:e0274518. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0274518

12. Valtorta NK, Kanaan M, Gilbody S, Ronzi S, Hanratty B. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal observational studies. Heart. (2016) 102:1009–16. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308790

13. Cené CW, Beckie TM, Sims M, Suglia SF, Aggarwal B, Moise N, et al. Effects of objective and perceived social isolation on cardiovascular and brain health: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. J Am Heart Assoc. (2022) 11:e026493. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.122.026493

14. Cudjoe TK, Prichett L, Szanton SL, Roberts Lavigne LC, Thorpe RJ Jr. Social isolation, homebound status, and race among older adults: findings from the National Health and Aging Trends Study (2011–2019). J Am Geriatr Soc. (2022) 70:2093–100. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17795

15. Huang AR, Roth DL, Cidav T, Chung SE, Amjad H, Thorpe RJ Jr, Boyd CM, Cudjoe TK. Social isolation and 9-year dementia risk in community-dwelling Medicare beneficiaries in the United States. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2023) 71:765–3. doi: 10.1111/jgs.18140

16. Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB. Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med. (2010) 7:e1000316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316

17. Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, Harris T, Stephenson D. Loneliness social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Perspect Psychol Sci. (2015) 10:227–37. doi: 10.1177/1745691614568352

18. VanderWeele TJ. On the promotion of human flourishing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2017). 114:8148-56. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1702996114

19. van Zanden JL, Rijpma A, Malinowski M, Mira d'Ercole M. How's Life? 2020: Measuring Well-being. How's Life? (2020). Available online at: https://www.oecd.org/wise/how-s-life-23089679.htm (accessed March 9, 2020)

20. Waldinger R. What Makes a Good Life. Lessons From the Longest Study on Happiness. Harvard University in the Daily Good: News that Inspires (2015). Available online at: http://www.giuliotortello.it/materiali/80_years_study_hapiness_harvard.pdf (accessed February 25, 2023).

21. Vaillant GE. Positive aging. In: Positive psychology in practice: Promoting human flourishing in work, health, education, everyday life. John Wiley & Sons (2015) p. 595–612. doi: 10.1002/9781118996874.ch35

22. Li S, Hagan K, Grodstein F, VanderWeele TJ. Social integration and healthy aging among US women. Prev Med Rep. (2018) 9:144–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2018.01.013

23. Plan H. Social connectedness.2018. Available online at: https://planh.ca/sites/default/files/tools-resources/socialconnectedness_ag_v2_1_web.pdf (accessed February 25, 2023).

24. Corbin I, Dhand AM. Unshared minds, decaying worlds: toward a pathology of chronic loneliness. J Med Philosophy.

25. Emlet CA, Moceri JT. The importance of social connectedness in building age-friendly communities. J Aging Res. (2012) 2012:173247. doi: 10.1155/2012/173247

26. Holt-Lunstad J. Why social relationships are important for physical health: a systems approach to understanding and modifying risk and protection. Annu Rev Psychol. (2018) 69:437–58. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-122216-011902

27. Holt-Lunstad J. Social connection as a public health issue: the evidence and a systemic framework for prioritizing the “social” in social determinants of health. Annu Rev Public Health. (2022) 43:193–13. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-052020-110732

28. Holt-Lunstad J, Robles TF, Sbarra DA. Advancing social connection as a public health priority in the United States. American psychologist. (2017) 72:517. doi: 10.1037/amp0000103

29. MacQueen KM, McLellan E, Metzger DS, Kegeles S, Strauss RP, Scotti R, et al. What is community? An evidence-based definition for participatory public health. Am J Public Health. (2001) 91:1929–38. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.91.12.1929

30. Cairney P, Kwiatkowski R. How to communicate effectively with policymakers: combine insights from psychology and policy studies. Palgrave Commun. (2017) 3:1–8. doi: 10.1057/s41599-017-0046-8

31. Administration for Community Living. Commit to Connect. Available online at: https://committoconnect.org/ (accessed February 25, 2023).

32. Foundation for Social Connection. Action Forum. Available online at: https://www.social-connection.org/action-forum/ (accessed February 25, 2023).

33. Fortune N, Madden R, Riley T, Short S. The International Classification of Health Interventions: an ‘epistemic hub' for use in public health. Health Promot Int. (2021) 36:1753–64. doi: 10.1093/heapro/daab011

34. Centers for Disease Control Prevention. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/index.html (accessed February 25, 2023).

35. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm (accessed February 25, 2023).

36. Hawkley LC. Loneliness health. Nat Rev Dis Primers. (2022) 8:22. doi: 10.1038/s41572-022-00355-9

37. Drinkwater C, Wildman J, Moffatt S. Social prescribing. Br Med J. (2019) 364:l1285. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l1285

38. Chatterjee H, Polley MJ, Clayton G. Social prescribing: community-based referral in public health. Perspect Public Health. (2017) 138:18–9. doi: 10.1177/1757913917736661

39. Wisdo Health Humana. Reducing Loneliness and Social Isolation among Medicare Advantage Members Using a Peer Support Community. Report Summary Pilot. (2022). Available online at: https://pages.wisdo.com/hubfs/Wisdo%20humana%20white%20paper_Final.pdf?utm_medium=email&_hsmi=244742080&_hsenc=p2ANqtz−3b8thj7pP8EeyMUAXu5YWqNThDzN3Y_pB7ws4V5fz5NWnNLDTAOsZEU2yTPsERUeLFjtBHCwoeQZEbmHuGov3re0BEw&utm_content=244742080&utm_source=hs_email (accessed February 25, 2023).

40. Far From Alone. Available online at: https://farfromalone.com/ (accessed February 25, 2023).

41. Beach B, Willis P, Powell J, Vickery A, Smith R, Cameron A. The impact of living in housing with care and support on loneliness and social isolation: findings from a resident-based survey. Innovat Aging. (2022) 6:igac061. doi: 10.1093/geroni/igac061

42. Shiell A, Hawe P, Kavanagh S. Evidence suggests a need to rethink social capital and social capital interventions. Social Sci Med. (2020) 257:111930. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.09.006

43. Steinman L, Parrish A, Mayotte C, Acevedo PB, Torres E, Markova M, et al. Increasing social connectedness for underserved older adults living with depression: a pre-post evaluation of PEARLS. Am J Geriatric Psychiat. (2021) 29:828–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.10.005

44. Smith ML, Chen E, Lau CA, Davis D, Simmons JW, Merianos AL. Effectiveness of chronic disease self-management education (CDSME) programs to reduce loneliness. Chronic Illn. (2022) 11:17423953221113604. doi: 10.1177/17423953221113604

45. Brady S, D'Ambrosio LA, Felts A, et al. Reducing isolation and loneliness through membership in a fitness program for older adults: implications for health. J Appl Gerontol. (2020) 39:301–10. doi: 10.1177/0733464818807820

46. Healthy Places By Design. Socially Connected Communities: Solutions for Social Isolation. (2021). Available online at: https://healthyplacesbydesign.org/socially-connected-communities-solutions-for-social-isolation/ (accessed February 25, 2023).

47. Towne SD, Smith ML, Pulczinski JC, Lee C, Ory MG. Older adults. In: Bolin J, editor. Rural Healthy People 2020: A Companion Document to Healthy People (2020). Bryan, Texas: outhwest Rural Health Research Center, School of Public Health, Texas A&M University System Health Science Center. (2015) p.107–118.

48. van Hoof J, Marston HR, Kazak JK, Buffel T. Ten questions concerning age-friendly cities and communities and the built environment. Build Environ. (2021) 199:107922. doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2021.107922

49. Menachemi N, Rahurkar S, Harle CA, Vest JR. The benefits of health information exchange: an updated systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. (2018) 25:1259–65. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocy035

50. Walker J, Pan E, Johnston D, Adler-Milstein J, Bates DW, Middleton B. The Value of Health Care Information Exchange and Interoperability: there is a business case to be made for spending money on a fully standardized nationwide system. Health Affairs. (2005) 24:W5–10. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.W5.10

51. Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. Social Determinants of Health Information Exchange Toolkit: Foundational Elements for Communities. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2023). Available online at: https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/2023-02/Social%20Determinants%20of%20Health%20Information%20Exchange%20Toolkit%202023_508.pdf (accessed February 25, 2023).

52. United Healthcare. Introducing UnitedHealthcare CatalystTM. (2023). Available online at: https://www.uhccommunityandstate.com/content/articles/introducing-unitedhealthcare-catalyst- (accessed February 25, 2023).

53. The Gravity Project. (2023). Available at: https://thegravityproject.net/ (accessed February 25, 2023).

54. Coalition to End Social Isolation and Loneliness (CESIL). Available online at: https://www.endsocialisolation.org/ (accessed February 25, 2023).

55. National Association of Chronic Disease Directors. Building Resilient Inclusive Communities (BRIC). Available at: https://chronicdisease.org/bric/ (accessed February 25, 2023).

56. Campaign to End Loneliness. Available online at: https://www.campaigntoendloneliness.org/ (accessed February 25, 2023).

57. Ending Loneliness Together. Available online at: https://endingloneliness.com.au/ (accessed February 25, 2023).

58. Global Initiative on Loneliness and Connection. Available online at: https://www.gilc.global/ (accessed February 25, 2023).

Keywords: social connectedness, social isolation, loneliness, community capacity, strategic initiatives, organizational collaboration

Citation: Smith ML, Racoosin J, Wilkerson R, Ivey RM, Hawkley L, Holt-Lunstad J and Cudjoe TKM (2023) Societal- and community-level strategies to improve social connectedness among older adults. Front. Public Health 11:1176895. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1176895

Received: 01 March 2023; Accepted: 11 April 2023;

Published: 04 May 2023.

Edited by:

Colette Joy Browning, Federation University Australia, AustraliaReviewed by:

Andrew Joyce, Swinburne University of Technology, AustraliaCopyright © 2023 Smith, Racoosin, Wilkerson, Ivey, Hawkley, Holt-Lunstad and Cudjoe. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Matthew Lee Smith, bWF0dGhldy5zbWl0aEB0YW11LmVkdQ==

Matthew Lee Smith

Matthew Lee Smith Jillian Racoosin4,5,6

Jillian Racoosin4,5,6 Risa Wilkerson

Risa Wilkerson Thomas K. M. Cudjoe

Thomas K. M. Cudjoe