95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Public Health , 24 May 2023

Sec. Aging and Public Health

Volume 11 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1163561

This article is part of the Research Topic Innovations in Measurement and Evidence for Healthy Aging View all 19 articles

Introduction: The increase in population aging establishes new risk scenarios in the face of the intensification of disasters due to climate change; however, previous experiences and collective memory would generate opportunities for older people to acquire adaptive and coping capacities in the face of these events.

Objective: To analyze the theoretical-methodological characteristics presented by the studies carried out between the years 2012 and 2022 about the experience and collective memory of the older adult in the face of climate change.

Method: A systematic literature review (SLR) was carried out following the guidelines of the PRISMA statement. The databases consulted were Web of Science, Scopus, EBSCO host, and Redalyc, selecting 40 articles in Spanish, English, and Portuguese.

Results: The importance of experience and collective memory in the face of disasters as an adaptive factor in older people was identified. In addition, sharing experiences allows them to give new meaning to what happened, emphasizing confidence in their personal resources and self-management capacity and fostering perceived empowerment.

Discussion: It is essential that in future studies the knowledge provided by the older adult can be privileged, recognizing the importance of their life histories and favoring the active role in their development and wellbeing.

Climate change has become one of the main risks that increase vulnerability to natural disasters, so it is essential to provide opportunities for the most exposed groups to acquire adaptation and coping capacities to face this problem on a global and local scale (1).

In this context, it is necessary to strengthen those societal and community measures that foster adaptive capacity and reduce vulnerability to disaster risk processes intensified by climate change, especially in the most susceptible groups, such as the older adult population (2, 3).

In addition to this scenario of global environmental crisis, there are statistical projections on the accelerated population aging (4), under which one out of every 11 older adult people living in underdeveloped countries is exposed to climate risks (5, 6).

In terms of the susceptibility of the older adult population to climate change, it is important to consider various aspects, such as mobility difficulties in evacuation and emergency processes, as well as the morbidities inherent to the evolutionary stage in which they find themselves (7–9).

On the other hand, the literature highlights that a population that manages to adapt to climatological stressors is considered less vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, due to the deployment of coping strategies that can absorb, recover, and/or resignify the potentially traumatic event in a resilient manner (10–13).

Among the studies that address the coping strategies used by the older adult population in the face of disaster risk processes, the importance of access to communication and dissemination technologies (14), recognition of safe zones within the home (15), and early warning systems (16) are noted. Likewise, in collective terms, collective memory has been recognized as a central community strategy because of the possibilities of resignification that it gives to the lived experience, as well as the intersubjective understanding of the stages of the disaster that occurred (17, 18), enabling the maintenance of a high collective awareness of the risks (19).

Another relevant individual capacity is life experiences in risk situations, which determine to a large extent the presence of those affected by disasters, which is conditioned by multiple factors such as identity, personality type, lifestyle, and living conditions, to mention just a few (20, 21). Within this field, there is research that indicates that sharing a strongly shocking collective experience tends to increase cohesion, operating as an instance of support, containment, and post-disaster repair (22, 23).

Therefore, and in line with the importance of both capacities to adapt to climate change in the older population, we argue the need to deepen the existing scientific evidence, on the experience and collective memory in the face of climate change (11, 24). To accomplish the above, we conducted a systematic literature review (SLR) of empirical research published between the years 2012 and 2022, that addressed the relationship between previous disaster experiences and/or collective memory of older people in the face of climate change risks. For this, we set the following objectives: (i) to identify authors, countries of the studies, types of memory and/or experiences, types of risk and/or disaster of natural origin associated, and sources of information and methodology used; (ii) to analyze the relationship of previous experiences of disaster and/or collective memory of the older adult to the risks of climate change; and (iii) to identify the lessons learned from the experiences and/or collective memory of the older adult population in the face of the risks of climate change.

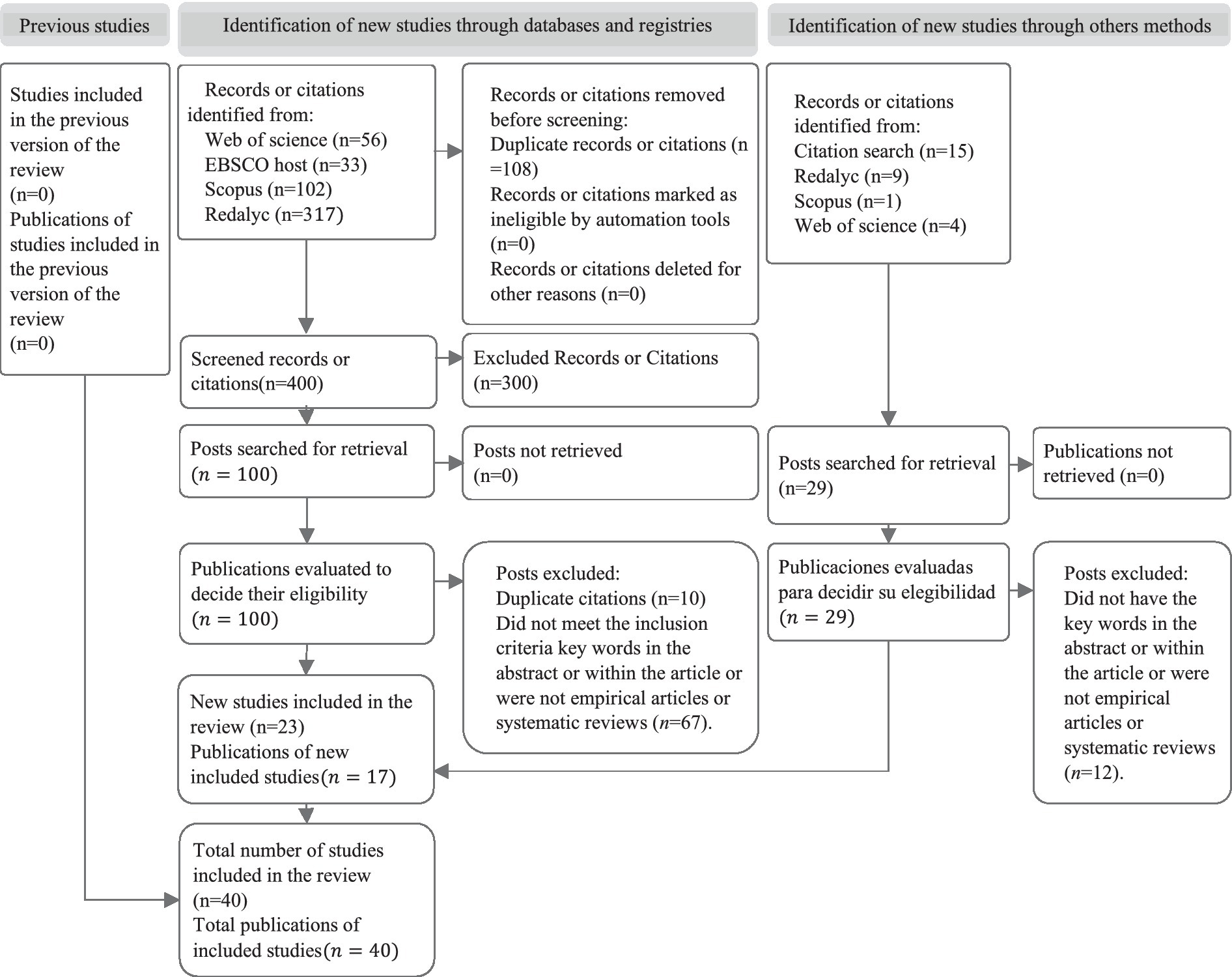

A systematic review of the literature (SLR) was carried out following the guidelines and recommendations of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement, complying with points 1–10, 13, 16–17, 20, and 23–27, from their checklist (25). In turn, following the PICo format of qualitative research, we pose the following research question: What role do previous disaster experiences and the collective memory of older people play in the face of climate change risks?

The search for articles was limited to studies with empirical data conducted in Spanish, English, and Portuguese with their respective keywords (see Table 1), using the Boolean operators AND, OR, and quotation marks AND and OR with the symbol + and quotation marks for the search, as indicated in Table 2. In addition, the exploration of articles published between 2012 and 2022 was configured during April and August 2022 from the search in four databases, from which a total of 50,849 documents were obtained Web of Science (n = 566), Scopus (n = 102), EBSCO host (n = 33), and Redalyc (n = 31,733). To complement the selection process, a second search for articles updated until the end of 2022 was carried out in the Web of Science (4 articles), Scopus (1 article) and Redalyc (9 articles) databases. In total, 15 additional articles were identified that met the eligibility criteria.

A selection was made in stages (see Figure 1). First, all the articles collected (n = 508) were compiled; second, the titles were read and duplicates were eliminated (n = 108); third, the titles, abstracts, keywords, and instruments used were read, eliminating those that did not meet the inclusion criteria (n = 300); fourth, a full-text reading was carried out, eliminating theoretical instrumental studies or those that did not focus their results on the collective experience and/or memory, climate change, and the older people (n = 67); fifth, a second search to obtain studies updated to 2022 from the databases and the search for citations (n = 29); and sixth, the last elimination was made of articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria (n = 12).

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram: literature identification and selection process. Prepared from Page et al. (25).

After the analysis and review of the selected articles (n = 40), an integrative synthesis of the selected works was carried out to compare the different studies, extracting: author/s and year of publication, country of the study, type of report or experience addressed, type of risk and/or disaster, methodology, sample, source of information, and whether it is primary or secondary.

Table 3 presents the synthesis of empirical studies, which are concentrated in Australia (13.2%), China (10.5%), the United States (7.9%), Mexico (7.9%), India (5.3%), and the United Kingdom (5.3%). In this context, Latin America and the Caribbean have gathered 18.9% of the studies, focusing their research on Mexico (7.9%), Chile (2.6%), and Ecuador (2.6%) while 10.5% of the remaining studies do not report the country of study.

There was a greater development of research around the general experience of the older adult (34.3%), oriented to the knowledge acquired from a lifetime; the lived experience (14.9%), referring to what was lived around daily life at the time of the disaster; personal experience (6%), which is not influenced by third parties, but only the subjective attribution of the subject is conceived; previous experience (4.5%), understood as the information that was obtained before the event, either directly or indirectly; life experience (4.5%), understood as the knowledge generated from what has been learned, directly or through the story provided by other people; local experience (3%), alluding to the learning generated from the environment and from what was lived in the community of origin; collective memory (3%); daily experience (3%), referring to what was lived around the daily chores within the home during the disaster; spatial experience (3%), understood as knowledge based on the area inhabited and beyond the home of origin, for example, knowledge based on what has been experienced as an immigrant.

Although there are several disasters of natural origin associated with climate change, studies on the experience of the older adult have mainly addressed floods (18.8%), heat waves (10.4%), storms (6.3%), droughts (6.3%), and climate change, in general (6.3%).

In terms of methodology, there was a predominance of qualitative studies (67.5%) that used interviews (52.5%) as the main technique. In relation to the role of older persons in the research analyzed, three subgroups were identified: i) older persons as a primary source (41%), ii) older persons as a mixed source, in which other key agents who live or work with the older adult population were incorporated (30.8%), and iii) older persons as an indirect source, that is, only through key agents (25.6%).

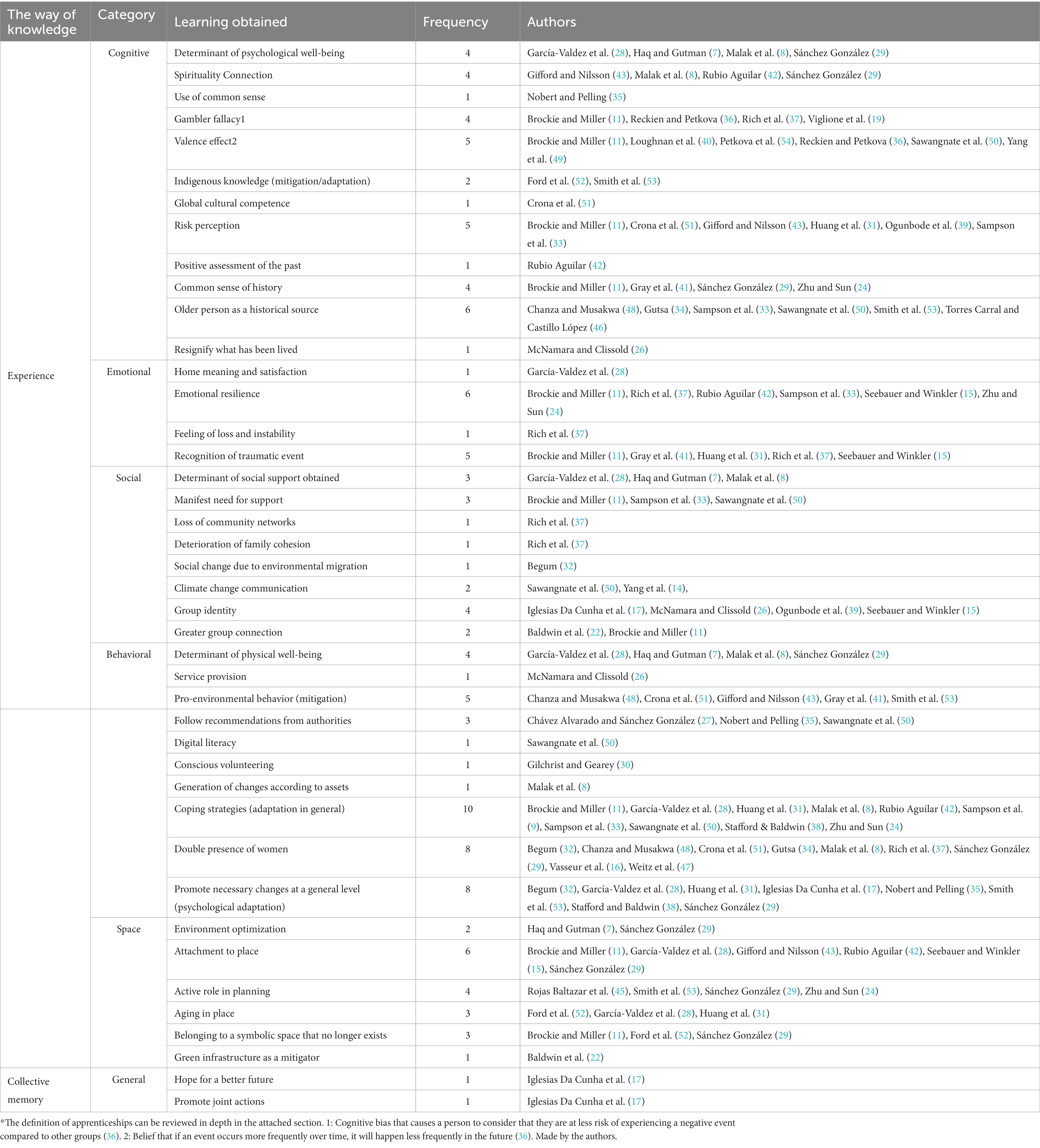

In another area, research has reported various lessons learned from the experience and/or collective memory of older people after a disaster (see Table 4). Through experience and from the cognitive point of view, this age group has been valued as a historical source due to all the knowledge they have obtained from their experience of a disaster (15%) and a greater risk perception after experiencing a disaster (12.5%). However, the valence effect (12.5%) has also been highlighted, which causes a greater risk in the population, making them believe that they have a lower risk of experiencing a negative event compared to other people (36). At an emotional level, emotional resilience stands out (15%), understood as the ability to not be affected or to overcome more quickly the worry, uncertainty, and anxiety caused by a disaster (41) and the one that can recognize the traumatic event (12.5%). At the social level, it stands out that after a disaster, the older adult tend to form a group identity (10%), favoring the social support obtained (7.5%) and the manifest need for support (7.5%). In other words, social cohesion increases and, consequently, it would favor the generation of new support networks, whether intra- or extra-familial (28). At the behavioral level, behavioral adaptation is revealed through generalized coping strategies (25%), the change in gender roles (20%), and a greater general adaptation to climate change (20%). At the spatial level, a greater attachment to the place where the older adult live (15%) and an active role in planning (10%) were observed.

Table 4. Learning obtained through experience or collective memory after a disaster according to studies.

Regarding collective memory, it was identified that, after a disaster, older people gained greater hope for the future, seeing it as a better future, and from this, they began to promote actions together with their peers to overcome the circumstances of risk of natural origin. However, this learning involved only 2.5% of recent research. Finally, regarding the characteristics of the other learning obtained, see Supplementary material S1 for their definitions.

Systematized scientific evidence shows that it has recently begun to be understood that the physical and emotional wellbeing of the older adult can be influenced by controlling the environment (34). However, it is paradoxical that this manifestation, on many occasions, does not come directly from this age group, but from key agents who interact with the older adult; it would therefore be interesting to know the perspective of the protagonists themselves. Therefore, it is essential that in future studies, the knowledge provided by the older adult can be privileged, recognizing the importance of their life histories and favoring the active role in their development and wellbeing (28).

It has been observed that when people can tell their stories of trauma, they can recover and resignify what happened more easily, emphasizing the confidence they have achieved in their strength and in the ability to manage the resources they were able to deploy in the face of a certain disaster, thus adapting to the post-event physical and social environment, enhancing perceived empowerment (28). In connection with the above, after experiencing a disaster, it would be beneficial for this group to have listening spaces, even more so given the perception of loneliness that has been manifested in various studies (11, 41, 55).

On the other hand, there is a gap in the literature regarding the study of the previous experiences and collective memory of the older adult in the face of risks and/or disasters of natural origin, mainly those caused by climate change, reflected in the low number of empirical studies found. In this way, it is important to delve into this issue, and, through it, enhance the agency capacity of the older adult, especially in those places where they are at greater risk of disaster (45).

When making a comparison between the number of studies that address experience and collective memory, the difference observed is significant, since when looking for an explanation, some studies express their preference for investigating collective memory only when it refers to phenomena that have greater social and psychological significance for the community (56, 57), prioritizing those events that are considered more “collectively representative” among the population. Therefore, some of the “silent risks” of climate change (such as heat waves and frosts) do not have great research relevance so far (58), increasing the scientific debt toward the older adult population. However, it is important to highlight that environmental gerontology, a relatively new discipline (especially in Latin America), has been focusing on carrying out multidisciplinary work that addresses this debt through the understanding, analysis, and optimization of the relationship between the physical-social environment and the aging person (59, 60). In this way, it is intended to raise awareness about the phenomenon of aging and the importance of building friendly environments that reinforce support networks within the community (29, 61).

In another area, it is possible to point out that much of the literature reviewed in the field of environmental gerontology and older people have been built in developed countries, evidencing a scarcity of research focused on the population of Latin America and the Caribbean (58, 62). In the same way, these studies are developed under qualitative methodologies, leaving aside other research perspectives (quantitative or mixed designs, for example), so it is necessary to expand the research development from this perspective (6), generating new knowledge based on the permanent change of the physical and social environments, even more so when they are in danger of experiencing a disaster in the short, medium or long term (59).

In short, it is essential to obtain adequate knowledge so that this same age group can generate the necessary strategies to adapt and protect itself from climate risks (13), minimizing susceptibilities by strengthening its capacity for the agency (28).

Previous disaster experiences and collective memory have been identified as adaptive capacities in older people (63), which has been expressed through the learnings obtained after some potentially traumatic event of natural origin. Specifically, negatively valenced emotions, be it fear and anger, and perceived self-efficacy would drive precautionary attitudes and behaviors (8, 53). In this case, the deployment of coping skills would be motivated by the level of involvement of the person in the face of the event experienced, which would amplify the perception of risk and the organization of their resources to deal functionally with climate change (43). Similarly, Sandoval-Obando (64) describes generative coping as that set of actions and tasks deployed by the older adult in the face of potentially traumatic events (pandemic for example), in which solidarity, trust, social participation, reciprocity, and mutual support give them a greater degree of self-efficacy and social support in the face of these events (65).

The agency capacity of the older adult in the face of disasters of natural origin, either individually or collectively, favors adaptation processes through experience and the respective personal meaning of what they have experienced (24, 31), actively empowering itself during the aging process. In other words, on a personal level, the older adult can value and make decisions about their lives and know how to act in the face of danger, beyond their family, and, on a social level, allows them to be part of the community, integrating and actively participating in their environment (66–68). In short, the empowerment of the older adult makes it possible to overcome ageism conceptions of old age, reducing vulnerability indices to the risks generated by climate change, and at the same time, allows them to be recognized as an age group of enormous historical-cultural value for future generations (30, 48).

By way of reflection, it is possible to point out that the experience and collective memory of this age group in the face of potentially traumatic events of natural origin, emerges as a resilient post-disaster attitude, thanks to the positive assessment they establish with themselves, in addition to the recognition and appreciation of their knowledge and personal resources (12, 42), becoming a determinant of individual/social resilience (69). At the same time, it would favor a better psychological adjustment and less emotional distress after a disaster (11). Finally, the experience of aging in changing environments as a consequence of climate change can stimulate the emergence of functional behaviors and challenging tasks for the older adult, contributing to their adaptive process (59).

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

CN-V and JS-D contributed to conception and design of the study. CN-V organized the database. CN-V, JS-D, and ES-O wrote sections of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

This work was financed by the National Agency for Research and Development (ANID)/FONDECYT of Initiation No. 11200683 and the UBB2095 project “Strengthening capacities and the role of collective memories in the face of disaster risk processes of the elderly” of the Universidad del Bío Bío.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1163561/full#supplementary-material

1. Siclari Bravo, P. G. (2021). Amenazas de cambio climático, métricas de mitigación y adaptación en ciudades de América Latina y el Caribe. CEPAL. Available at: https://hdl.handle.net/11362/46575 (Accessed October 3, 2022).

2. Magrin, G. (2015). Adaptación al cambio climático en América Latina y el Caribe. CEPAL. Available at: https://hdl.handle.net/11362/39842 (Accessed October 3, 2022).

3. Sarker, MNI, Wu, M, Shouse, RC, and Ma, C. Administrative resilience and adaptive capacity of administrative system: a critical conceptual review In: J En Xu, S Ahmed, F Cooke, and G Duca, editors. Proceedings of the thirteenth international conference on management science and engineering management. ICMSEM 2019. Advances in intelligent systems and computing, vol. 1002. Cham: Springer (2020)

4. Huenchuan, S. (2018). Envejecimiento, personas mayores y Agenda 2030 para el Desarrollo Sostenible: perspectiva regional y de derechos humanos. CEPAL. Available at: https://hdl.handle.net/11362/44369 (Accessed August 17, 2022).

5. Banco Mundial, I. D. D. M. (2021). Población de 65 años de edad y más (% del total) [Archivo de datos]. Available at: https://datos.bancomundial.org/indicator/SP.POP.65UP.TO.ZS (Accessed November 15, 2022).

6. Sánchez, D, and Chávez, R. Envejecimiento de la población y cambio climático In: Vulnerabilidad y resiliencia desde la Gerontología Ambiental. Asociación de Geográfos Españoles. Comares: Granada (2019)

7. Haq, G, and Gutman, G. Climate gerontology: meeting the challenge of population ageing and climate change. Zeitschrift fur Gerontologie und Geriatrie. (2014) 47:462–7. doi: 10.1007/s00391-014-0677-y

8. Malak, MA, Sajib, AM, Quader, MA, and Anjum, H. "we are feeling older than our age": vulnerability and adaptive strategies of aging people to cyclones in coastal Bangladesh. Int J Disast Risk Reduct. (2020) 48:101595. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101595

9. Sampson, NR, Gronlund, CJ, Buxton, MA, Catalano, L, White-Newsome, JL, Conlon, KC, et al. Staying cool in a changing climate: reaching vulnerable populations during heat events. Glob Environ Chang. (2013) 23:475–84. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2012.12.011

10. Astill, S, and Miller, E. 'The trauma of the cyclone has changed us forever': self-reliance, vulnerability and resilience among older Australians in cyclone-prone areas. Ageing Soc. (2018) 38:403–29. doi: 10.1017/s0144686x1600115x

11. Brockie, L, and Miller, E. Understanding older adults’ resilience during the Brisbane floods: social capital, life experience, and optimism. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. (2017) 11:72–9. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2016.161

12. Navarrete Valladares, C, and Sandoval-Díaz, J. El rol del apoyo social frente al cambio climático en la población mayor. Revista Pensamiento y Acción Interdisciplinaria. (2022) 8:13–33. doi: 10.29035/pai.8.2.13

13. Solís, S. (2021). Influencia del cambio climático en la salud de las personas mayores 2021. Available at: https://gerathabana2021.sld.cu/index.php/gerathabana/2021/paper/download/103/72 (Accessed October 06, 2022).

14. Yang, JX, Gounaridis, D, Liu, MM, Bi, J, and Newell, JP. Perceptions of climate change in China: evidence from surveys of residents in six cities. Earths Future. (2021) 9:2144. doi: 10.1029/2021ef002144

15. Seebauer, S, and Winkler, C. Should I stay or should I go? Factors in household decisions for or against relocation from a flood risk area. Glob Environ Chang. (2020) 60:102018. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2019.102018

16. Vasseur, L, Thornbush, M, and Plante, S. Gender-based experiences and perceptions after the 2010 winter storms in Atlantic Canada. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2015) 12:12518–29. doi: 10.3390/ijerph121012518

17. Iglesias Da Cunha, L, Pardellas Santiago, M, and GradaÍLle Pernas, R. Públicos invisibles, espacios educativos improbables: el proyecto "Descarboniza! que non é pouco…" como educación para el cambio climático. Invisible Audiences, Unlikely Educational Spaces: The "Descarboniza! que non é pouco…". Projects Educ Climate Change. (2020) 36:81–93. doi: 10.7179/PSRI_2020.36.05

18. Meza, J. E. (2018). Memoria colectiva y desastres. Implicaciones psicosociales y subjetivas del terremoto de Nicoya, Costa Rica. Argumentos Estudios críticos de la sociedad, 101–118. Available at: https://argumentos.xoc.uam.mx/index.php/argumentos/article/view/1033 (Accessed October 26, 2022).

19. Viglione, A, Di Baldassarre, G, Brandimarte, L, Kuil, L, Carr, G, Salinas, JL, et al. Insights from socio-hydrology modelling on dealing with flood risk–roles of collective memory, risk-taking attitude and trust. J Hydrol. (2014) 518:71–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2014.01.018

20. Díaz Prieto, C, and García Sánchez, JN. Influencia de las experiencias vitales sobre la calidad de vida percibida de adultos y mayores. Int J Dev Educ Psychol. (2019) 2:321–7. doi: 10.17060/ijodaep.2019.n1.v2.1648

21. García Fernández, C. El cambio climático: Los aspectos científicos y económicos mas relevantes. Nómadas Crit J Social Juridical Sci. (2011) 32:38052. doi: 10.5209/rev_noma.2011.v32.n4.38052

22. Baldwin, C, Matthews, T, and Byrne, J. Planning for older people in a rapidly warming and ageing world: the role of urban greening. Urban Policy Res. (2020) 38:199–212. doi: 10.1080/08111146.2020.1780424

23. Sainz, S. (2003). Estrategias de afrontamiento del impacto emocional y sus efectos en trabajadores de emergencias. Available at: https://rephip.unr.edu.ar/handle/2133/10915 (Accessed January 12, 2023).

24. Zhu, XX, and Sun, BQ. Recognising and promoting the unique capacities of the elderly. Int J Emerg Manag. (2018) 14:137–51. doi: 10.1504/ijem.2018.090883

25. Page, MJ, McKenzie, JE, Bossuyt, PM, Boutron, I, Hoffmann, TC, Mulrow, CD, et al. Declaración PRISMA 2020: una guía actualizada para la publicación de revisiones sistemáticas. Rev Esp Cardiol. (2021) 74:790–9. doi: 10.1016/j.recesp.2021.06.016

26. McNamara, KE, and Clissold, R. Vulnerable groups and preliminary insights into intersecting categories of identity in Laamu atoll, Maldives Singapore. J Trop Geography. (2019) 40:410–28. doi: 10.1111/sjtg.12280

27. Chávez Alvarado, R, and Sánchez González, D. Personas mayores con discapacidad afectadas por inundaciones en la ciudad de Monterrey, México. Análisis de su entorno físico-social. Cuadernos Geográficos. (2016) 55:85–106. Available at: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=17149048004

28. García-Valdez, MT, Román-Pérez, R, and Sánchez-González, D. Envejecimiento y estrategias de adaptación a los entornos urbanos desde la gerontología ambiental. Estudios Demográficos y Urbanos. (2019) 34:101–28. doi: 10.24201/edu.v34i1.1810

29. Sánchez González, D. Ambiente físico-social y envejecimiento de la población desde la gerontología ambiental y geografía. Implicaciones socioespaciales en América Latina. Revista de Geografía Norte Grande. (2015) 60:97–114. doi: 10.4067/S0718-34022015000100006

30. Gilchrist, P, and Gearey, M. Reframing rural governance: gerontocratic expressions of socio-ecological resilience. Ager Revista de Estudios sobre Despoblación y Desarrollo Rural. (2019) 27:103–27. doi: 10.4422/ager.2019.12

31. Huang, J, Cao, W, Wang, H, and Wang, Z. Affect path to flood protective coping behaviors using sem based on a survey in Shenzhen, China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:940. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17030940

32. Begum, S. Effects of livelihood transformation on older persons in the Nordic Arctic: a gender-based analysis. Polar Record. (2016) 52:159–69. doi: 10.1017/s0032247415000819

33. Sampson, NR, Price, CE, Kassem, J, Doan, J, and Hussein, J. “We’re just sitting ducks”: recurrent household flooding as an underreported environmental health threat in Detroit’s changing climate. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:1006. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16010006

34. Gutsa, I. Emic ethnographic encounters: researching elderly female household heads’ experience with climate change in rural Zimbabwe. Ethnography. (2021). doi: 10.1177/14661381211030888

35. Nobert, S, and Pelling, M. What can adaptation to climate-related hazards tell us about the politics of time making? Exploring durations and temporal disjunctures through the 2013 London heat wave. Geoforum. (2017) 85:122–30. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.07.010

36. Reckien, D, and Petkova, EP. Who is responsible for climate change adaptation? Environ Res Lett. (2019) 14:aaf07a. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/aaf07a

37. Rich, JL, Wright, SL, and Loxton, D. Older rural women living with drought. Local Environ. (2018) 23:1141–55. doi: 10.1080/13549839.2018.1532986

38. Stafford, L, and Baldwin, C. Planning walkable neighborhoods: are we overlooking diversity in abilities and ages? J Plan Lit. (2018) 33:17–30. doi: 10.1177/0885412217704649

39. Ogunbode, CA, Demski, C, Capstick, SB, and Sposato, RG. Attribution matters: revisiting the link between extreme weather experience and climate change mitigation responses. Glob Environ Chang. (2019) 54:31–9. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/w86cn

40. Loughnan, ME, Carroll, M, and Tapper, N. Learning from our older people: pilot study findings on responding to heat. Australas J Ageing. (2014) 33:271–7. doi: 10.1111/ajag.12050

41. Gray, SG, Raimi, KT, Wilson, R, and Árvai, J. Will millennials save the world? The effect of age and generational differences on environmental concern. J Environ Manag. (2019) 242:394–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.04.071

42. Rubio Aguilar, V. Personas mayores en situaciones de desastre: un análisis desde su experiencia en el incendio de Valparaíso de 2014. Sophia Austral. (2019) 24:119–44. doi: 10.4067/s0719-56052019000200119

43. Gifford, R, and Nilsson, A. Personal and social factors that influence pro-environmental concern and behaviour: a review. Int J Psychol. (2014) 49:141–57. doi: 10.1002/ijop.12034

44. Yang, J, Zhou, Q, Liu, X, Liu, M, Qu, S, and Bi, J. Biased perception misguided by affect: how does emotional experience lead to incorrect judgments about environmental quality? Glob Environ Chang. (2018) 53:104–13. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2018.09.007

45. Rojas Baltazar, A, Chung Alonso, P, and Correa Fuentes, DA. Servicios urbanos para la construcción de resiliencia en los espacios públicos de tipo abierto en México. Vivienda y Comunidades Sustentables. (2022) 11:23–49. doi: 10.32870/rvcs.v0i11.178

46. Torres Carral, GA, and Castillo López, S. Milpa y saberes mayas en San Sebastián Yaxché, Peto, Yucatán. Estudios de Cultura Maya LIX. (2022) 59:171–89. doi: 10.19130/iifl.ecm.59.22x876

47. Weitz, CA, Mukhopadhyay, B, and Das, K. Individually experienced heat stress among elderly residents of an urban slum and rural village in India. Int J Biometeorol. (2022) 66:1145–62. doi: 10.1007/s00484-022-02264-8

48. Chanza, N, and Musakwa, W. Indigenous local observations and experiences can give useful indicators of climate change in data-deficient regions. J Environ Stud Sci. (2022) 12:534–46. doi: 10.1007/s13412-022-00757-x

49. Yang, ZM, Yang, B, Liu, PF, Zhang, YQ, Hou, LL, and Yuan, XC. Exposure to extreme climate decreases self-rated health score: large-scale survey evidence from China. Global Environ Change Human Policy Dimen. (2022) 74:102514. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2022.102514

50. Sawangnate, C, Chaisri, B, and Kittipongvises, S. Flood Hazard mapping and flood preparedness literacy of the elderly population residing in Bangkok, Thailand. Water. (2022) 14:1268. doi: 10.3390/w14081268

51. Crona, B, Wutich, A, Brewis, A, and Gartin, M. Perceptions of climate change: linking local and global perceptions through a cultural knowledge approach. Clim Chang. (2013) 119:519–31. doi: 10.1007/s10584-013-0708-5

52. Ford, JD, Cameron, L, Rubis, J, Maillet, M, Nakashima, D, Willox, AC, et al. Including indigenous knowledge and experience in IPCC assessment reports. Nat Clim Chang. (2016) 6:349–53. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2954

53. Smith, BM, Chakrabarti, P, Chatterjee, A, Chatterjee, S, Dey, UK, Dicks, LV, et al. Collating and validating indigenous and local knowledge to apply multiple knowledge systems to an environmental challenge: a case-study of pollinators in India. Biol Conserv. (2017) 211:20–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2017.04.032

54. Petkova, EP, Ebi, KL, Culp, D, and Redlener, I. Climate change and health on the U.S. Gulf Coast: public health adaptation is needed to address future risks. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2015) 12:9342–56. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120809342

55. Rhoades, JL, Gruber, JS, and Horton, B. Developing an in-depth understanding of elderly adult’s vulnerability to climate change. Gerontologist. (2018) 58:567–77. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw167

56. Manzi, J, Helsper, E, Ruiz, S, Krause, M, and Kronmüller, E. El pasado que nos pesa: La memoria colectiva del 11 de septiembre de 1973. Revista de ciencia política (Santiago). (2003) 23:177–214. doi: 10.4067/s0718-090x2003000200009

57. Martínez, MAS, and Brito, RM. Memoria colectiva y procesos sociales. Enseñanza e investigación en psicología. (2005) 10:171–89. Available at: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=29210112

58. Chávez-Alvarado, R, and Sánchez-González, D. Envejecimiento vulnerable en hogares inundables y su adaptación al cambio climático en ciudades de América Latina: el caso de Monterrey. Papeles de Población. (2016) 22:9–42. doi: 10.22185/pp.22.2016/033

59. Sánchez-González, D. Contexto ambiental y experiencia espacial de envejecer en el lugar: el caso de Granada. Papeles de población. (2009) 15:175–213. Available at: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=11211340008

60. Yu, J, and Rosenberg, MW. Aging and the changing urban environment: the relationship between older people and the living environment in post-reform Beijing. China Urban Geography. (2020) 41:162–81. doi: 10.1080/02723638.2019.1643172

61. Cano Gutiérrez, E., and Sánchez-González, D. (2019). Espacio público y sus implicaciones en el envejecimiento activo en el lugar. Cuadernos de Arquitectura y Asuntos Urbanos. Available at: ://hdl.handle.net/10486/689068

62. Agich, G. Dependence and autonomy in old age: an ethical framework for long-term care. J Med Ethics. (2003) 31:e3. doi: 10.1136/jme.2003.006783

63. Almazan, JU, Cruz, JP, Alamri, MS, Albougami, ASB, Alotaibi, JSM, and Santos, AM. Coping strategies of older adults survivors following a disaster: disaster-related resilience to climate change adaptation. Ageing Int. (2019) 44:141–53. doi: 10.1007/s12126-018-9330-1

64. Sandoval-Obando, E, Altamirano, V, Isla, B, Loyola, V, and Painecura, C. Social and political participation of Chilean older people: an exploratory study from the narrative-generative perspective. Archives of Health. (2021) 2:1631–49. doi: 10.46919/archv2n8-003

65. Sandoval Díaz, JS, Monsalves Peña, S, and y Vejar Valles, V. Capacidades y capital social ante un riesgo natural en personas mayores: el caso del Complejo Volcánico Nevados de Chillán, Chile. Perspect Geogr. (2022) 27:40–59. doi: 10.19053/01233769.13434

66. Arias, CJ, and Iacub, R. El empoderamiento en la vejez. J Behav Health Social Issues. (2010) 2:17–32. doi: 10.5460/jbhsi.v2.2.26787

67. Carrera, B. (2019). Ambiente y vejez. Oportunidades de empoderamiento desde una perspectiva ambientalmente sustentable. Rev Invest. Available at: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=376168604010 (Accessed January 12, 2023).

68. Sandoval-Díaz, JS, Monsalves-Peña, SR, Vejar-Valle, V, and Bravo-Ferretti, C. Apego al lugar y percepción del riesgo volcánico en personas mayores de Ñuble, Chile. Urbano. (2022) 25:8–19. doi: 10.22320/07183607.2022.25.46.01

Keywords: older people, climate change, disasters, vital experience, collective memory

Citation: Navarrete-Valladares C, Sandoval-Díaz J and Sandoval-Obando E (2023) Experience and local memory of older people in the face of disasters: a systematic review. Front. Public Health. 11:1163561. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1163561

Received: 10 February 2023; Accepted: 28 April 2023;

Published: 24 May 2023.

Edited by:

Marcela Agudelo-Botero, National Autonomous University of Mexico, MexicoReviewed by:

Mondira Bardhan, Clemson University, United StatesCopyright © 2023 Navarrete-Valladares, Sandoval-Díaz and Sandoval-Obando. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: José Sandoval-Díaz, anNhbmRvdmFsQHViaW9iaW8uY2w=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.