- 1Faculty of Psychology, Tianjin Normal University, Tianjin, China

- 2Mental Health Education and Counselling Centre, Hubei Normal University, Huangshi, China

- 3Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China

With the coronavirus pandemic in 2019 (COVID-19), work from home (WFH) has become a frequent way of responding to outbreaks. Across two studies, we examined how perceived organizational support influences job performance when employees work in office or work from home. In study 1, we conducted a questionnaire survey of 162 employees who work in office. In study 2, we conducted a questionnaire survey of 180 employees who work from home. We found that perceived organizational support directly affected job performance when employees work in office. When employees work from home, perceived organizational support could not affect job performance directly. However, it could influence job performance indirectly through the separate mediating effects of job satisfaction and work engagement. These findings extend our understanding of the association of perceived organizational support and job performance and enlighten enterprises on improving employees' job performance during the COVID-19 pandemic.

1. Introduction

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak a pandemic; this pandemic has had major impacts around the world (1, 2). Forced closure of enterprises and industries around the world to curb the spread of the virus has brought a series of unique challenges to employees and employers (3). This change forced companies and employees to quickly adapt to work-from-home (WFH) policies (4). Gartner's survey of 229 HR departments revealed that about half of the companies had more than 80% of their employees working from home in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, and estimated a large long-term increase in working from home after the pandemic (5).

Yet as many employees and employers had to suddenly work from home for the first time and without any preparation (6), and this sudden shift changed work arrangements and negatively impacted employees' physical and mental state as well as their work (2), which ultimately reduced job performance (7–9). WFH can lead to employees' loneliness, difficulties in team communication (10) and cooperation, and decreased job performance (11). For example, online communication lacks nonverbal cues, which increases loneliness (12) and is strongly negatively correlated with employees' affective commitment, affiliative behavior and job performance (13); online communication can lead to anxiety, confusion and communication errors among employees (14), and may even reduce the level of trust in teams (15). During a pandemic WFH prevent social connections and quality social interactions, which can also take a toll on employees' physical and mental health, further reducing job performance (16). Therefore, how to improve the job performance when the employees work from home is an urgent problem.

There are many important effects could improve the job performance, perceived organizational support, as a common variable in management and organizational behavior, is one of the most important ways for improving job performance (17–19). However, WFH has various negative impacts, such as increased loneliness, poor team communication and reduced trust, which may affect the mechanism of perceived organizational support.

Therefore, this study aims to compare how perceived organizational support influence employees' job performance when employees in WFH and work in office. In addition, many other factors might play a role in this mechanism, such as individual qualities, motivation, psychological capital, job satisfaction, we also put them into our considering model.

1.1. Relationship between perceived organizational support and job performance

Employees' job performance consists of a range of different activities that contribute to the organization in different ways; it is “employee behaviors that are relevant to the goals of the organization” (20). Job performance is also defined as the result of the function or indicator of a job or an occupation in a certain period of time (21).

Eisenberger proposed the concept of perceived organizational support, which referred to employee perceptions of how the organization views their contributions and cares about their interests. In short, perceived organizational support reflects the support employees feel from their organization (22). According to organizational support theory (OST), perceived organizational support is a valuable resource that will elicit norms of reciprocity in the process of social exchange, which will lead to greater employee efforts on behalf of the organization because of perceived indebtedness or perceived obligation and expected reward. Perceived organizational support also meets socioemotional needs, leading to greater identification and commitment to the organization, increased desire to help the organization succeed, and improved mental health (23–25). In addition, if an employee receives adequate training, resources, and support from their organization, he or she is more likely to expect the organization to achieve its goals and more likely to help the organization achieve its goals.

Some researchers have proposed that perceived organizational support can increase extra-role behaviors and reduce harmful behaviors to the organization; thus, they regard perceived organizational support as a predictor of job performance (17–19), which confirmed by several recent empirical studies (26–29). And perceived organizational support is positively correlated with job performance (30, 31), as demonstrated in previous studies. For example, a meta-analysis of 167 studies found that perceived organizational support has a moderate, positive effect on job performance (32). Shanock and Eisenberger (33) also found that perceived organizational support reduces behavior detrimental to the organization. Based on these studies, we believe that perceived organizational support has an undeniable positive impact on job performance.

However, the exact relationship between perceived organizational support and job performance remains controversial. Chen and Chen (34) discussed the degree of agreement between direct and indirect effects and empirical data, with results favoring a direct (rather than indirect) effect of perceived organizational support on job performance. However, recent research has suggested that perceived organizational support affects employees' job performance by generating positive emotions and gratitude based on social exchange processes (35). WFH due to the pandemic increased employee loneliness and socioemotional needs. Therefore, we believe that, for employees who work from home, the impact of perceived organizational support on job performance is more likely to occur through meeting employees' emotional needs, such as job satisfaction and work engagement. Based on these theories and empirical findings, we hypothesize the following: (a) In the condition of working in office, perceived organizational support directly affects job performance; (b1) In the condition of WFH, perceived organizational support indirectly affects job performance.

1.2. The relationships among job satisfaction, perceived organizational support, and job performance

Job satisfaction is a positive emotion that encompasses emotions such as joy, happiness, passion, enthusiasm and love (36). Others define job satisfaction as a positive emotional attitude toward work (37). Such positive emotions are generated when employees strongly feel that their organization cares for them and supports them. Meta-analyses and qualitative reviews of the literature on perceived organizational support have shown positive relationships between perceived organizational support and job satisfaction (17, 19, 24). This finding has been confirmed by recent empirical studies. A study with 127 school teachers found that perceived organizational support had a positive effect on both job and life satisfaction (38). A study of cement workers in Iran reached the same conclusion (39).

According to organizational support theory, when employees feel strongly supported by the organization, their socioemotional needs will be satisfied, which leads to increased job satisfaction. These employees will reciprocate by caring for the organization and doing their job well. A meta-analysis of 100 articles revealed a significant moderate positive relationship between job performance and job satisfaction (40). Dinc et al. (41) conducted a study on the job performance of nurses in hospitals and found that improvements in job satisfaction had a significant impact on nurse job performance. According to a study on 104 school principals and 313 teachers (42), a one-unit increase in job satisfaction of teachers led to a 10% increase in job performance. The support employees receive from the organization creates a positive impression and leads to positive results for both employees and the organization. Based on these findings, we hypothesize that (b2) in the condition of WFH, job satisfaction mediates the impact of perceived organizational support on job performance.

1.3. The mediating role of work engagement

Work engagement is defined as “a positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind that is characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption” (43) and is characterized by a high level of energy and strong identification with one's work (44).

According to the job demands-resources (JD-R) model, we suggest that perceived organizational support provides socioemotional support and is positively related to work engagement. When employees feel valued and supported by their organization, it enhances self-esteem and increases job satisfaction, thereby reinforcing their ability to manage work stress (45). Perceived organizational support also conveys the organization's evaluation of employee efforts and satisfies the employee's need for positive feedback and approval, which can also promote the intrinsic interest of employees and thus improve their work engagement (25). Other studies have also found that perceived organizational support is positively correlated with work engagement (46, 47).

In regard to the consequences of work engagement, numerous studies have linked work engagement to better health and positive emotions (48–52). Bakker (53) suggested that employees with higher levels of work engagement have higher job performance because (a) they experience positive emotions, which helps them to generate new ideas and resources, and (b) their health is improved, providing them with energy to work. Additionally, work engagement is regarded as a reasonable predictor of job performance because employees who most identify with their jobs tend to focus their thoughts on their jobs (54, 55). These findings have been empirically supported. Halbesleben and Wheeler (56) analyzed a sample of U.S. employees (n = 587), their supervisors, and their closest colleagues from a variety of industries and occupations and found that work engagement predicted not only higher self-reported in-role performance 2 months later but also higher in-role performance as rated by superiors and peers. Tisu et al. (57) analyzed a sample of Romanian workers and found that work engagement has positive effects on mental health and job performance. Based on these findings, we hypothesize that (b3) in the condition of WFH, work engagement mediates the impact of perceived organizational support on job performance.

1.4. The chain mediating effect of job satisfaction and work engagement

According to social exchange, employees and their organization form a positive emotional connection after a long-term successful exchange relationship and employees are more willing to improve the performance of the organization and make their own efforts to maintain such a social exchange relationship (58). While material reciprocity leads to temporary pleasure, spiritual reciprocity can bring long-term benefits. Organizational support includes not only material support but also spiritual support, such as attention, concern, encouragement and respect for employees. Recent research suggests that gratitude or other positive emotions generated by perceived organizational support may also help improve employees' job performance based on social exchange processes (35).

When perceived organizational support is high, employees are (under certain conditions) more likely to exhibit higher job performance and reduced absenteeism. However, some studies have shown different results. Stamper and Johlke (59) reported that perceived organizational support was not related to salespeople's task performance. In addition, some studies have suggested that perceived organizational support mediates multiple types of organizational experience variables and thus may not directly affect job performance (19, 30, 59).

An empirical study of 744 police officers in China found a nonsignificant direct effect of perceived organizational support on work engagement, but a significant indirect relationship of these variables mediated by job satisfaction (60). We discussed the mediating effects of job satisfaction and work engagement in the above section. According to social exchange theory, perceived organizational support, job satisfaction and work engagement meet the needs of employees; thus, these factors affect employees' job performance. Based on these findings, we hypothesize that (b4) in the condition of WFH, job satisfaction and work engagement exert a chain mediating effect on the relationship between perceived organizational support and job performance.

1.5. Overall hypothetical model

In conclusion, the research hypotheses were as follows:

(a) In the condition of working in office, perceived organizational support directly affects job performance;

(b1) In the condition of WFH, perceived organizational support indirectly affects job performance;

(b2) In the condition of WFH, job satisfaction mediates the impact of perceived organizational support on job performance;

(b3) In the condition of WFH, work engagement mediates the impact of perceived organizational support on job performance;

(b4) In the condition of WFH, job satisfaction and work engagement exert a chain mediating effect on the relationship between perceived organizational support and job performance.

To test these hypotheses, this study used two questionnaire surveys (one is in employees of working in office, one is in employees of WFH) to compare the different models of perceived organizational support and job performance.

2. Study 1

2.1. Subjects

This study was conducted online through a survey website. The survey website sent the link to the questionnaire to the email address of full-time employees who work in office, and the completed questionnaire was collected through the survey website. In this study, a screening question was included in the questionnaire to identify and exclude participants who did not answer carefully. One hundred sixty-two valid questionnaires were returned, with an effective recovery rate of 93.10%. All participants signed informed consent prior to filling out the questionnaire. They were paid 10 yuan for participating after completing the questionnaire. Among the participants, 67 were male (41.4%), and 95 were female (58.6%). The study was reviewed and approved by Ethics Committee of Hubei Normal University. All participants signed informed consent prior to filling out the questionnaire.

2.2. Materials

2.2.1. Perceived Organizational Support Scale

This study used the Perceived Organizational Support Scale (POSS) developed by Ling et al. (61). The scale consists of 24 items scored on a 5-point Likert scale and is divided into three dimensions: work support, value identification and interest concern. The higher the total POSS score is, the better the respondent's perceived organizational support. The POSS demonstrates high reliability and suitable for the Chinese population. In this study, the internal consistency coefficient was 0.934.

2.2.2. Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire

The Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire (MSQ) developed by Weiss et al. (62) was used to measure job satisfaction. The MSQ consists of 20 items with responses given on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The higher the total score is, the higher the respondent's job satisfaction. The internal consistency coefficient for this study was 0.914.

2.2.3. Utrecht Work Engagement Scale-9

The Utrecht Work Engagement Scale-9 (UWES-9) developed by Schaufeli et al. (63) is widely used; it was later revised by Zhang and Gan (64) to accommodate the cultural background of China. The UWES-9 consists of nine items scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The higher the total score is, the higher the respondent's work engagement. The internal consistency coefficient for this study was 0.899.

2.2.4. Job Performance Scale

The job performance scale (JPS) developed by Li et al. (65) was used in this study. This scale contains two dimensions: task performance and relationship performance, with a total of nine items. Among them, task performance is evaluated with five items, such as “I rarely make mistakes when completing work.” Relationship performance is evaluated with four items, such as “I treat my colleagues fairly” and “I offer to help my colleagues.” The nine items are scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The higher the total score is, the higher the respondent's job performance. The internal consistency coefficient for this study was 0.763.

2.3. Statistical analysis

SPSS Statistic 26.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics, New York, United States) was used to perform general descriptive statistics and Pearson correlation analysis (two-sided p < 0.05 was considered significant). To ensure the accuracy of the results, the variance inflation factor (VIF) method was used to assess collinearity (VIF > 10 indicates serious collinearity between the variables, and the corresponding variables should be eliminated). Model 6 in the process plug-in compiled by Hayes (66) was used for chain mediating effect analysis, and the bias-corrected percentile bootstrap method was used to evaluate the significance of the mediating effect. If the 99% confidence interval (CI) did not contain 0, the effect was considered statistically significant (67). In addition, Harman's one-factor test was used to test for common method bias before analyzing the data (68).

2.4. Results

2.4.1. Common method bias test

Because this study used self-report scales to collect data, which can lead to common method bias, the Harman single-factor method of exploratory factor analysis including perceived organizational support, job satisfaction, work engagement, and job performance was conducted. Only 34.847% of the variance was explained by the largest factor, which is less than the critical value of 40%, indicating that there was no significant common method bias in this study.

2.4.2. Correlations among perceived organizational support, job satisfaction, work engagement, and job performance

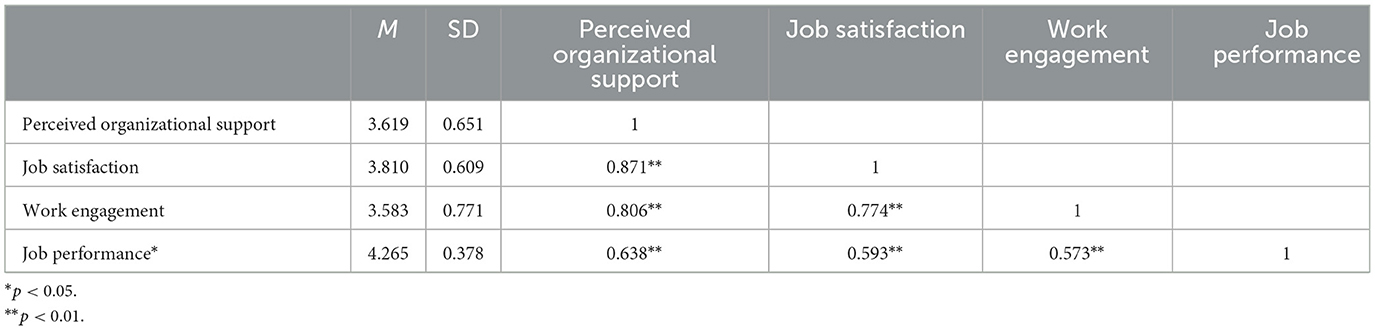

Table 1 presents the means (M), standard deviations (SD) and correlations. The highest mean is job performance (4.265). Pearson's product-moment correlation analysis was used to analyze relationships among perceived organizational support, job satisfaction, work engagement, and job performance (see Table 1). The results showed that ① perceived organizational support was significantly positively correlated with job satisfaction, work engagement and job performance (r = 0.871, p < 0.01; r = 0.806, p < 0.01; and r = 0.638, p < 0.01, respectively); ② work engagement was significantly positively correlated with job performance and job satisfaction (r = 0.573, p < 0.01 and r = 0.774, p < 0.01, respectively); and ③ job satisfaction was significantly positively correlated with job performance (r = 0.593, p < 0.01).

2.4.3. Relationship between perceived organizational support and job performance: A chain mediation model

The above analysis showed significant correlations among the variables and the presence of possible collinearity.

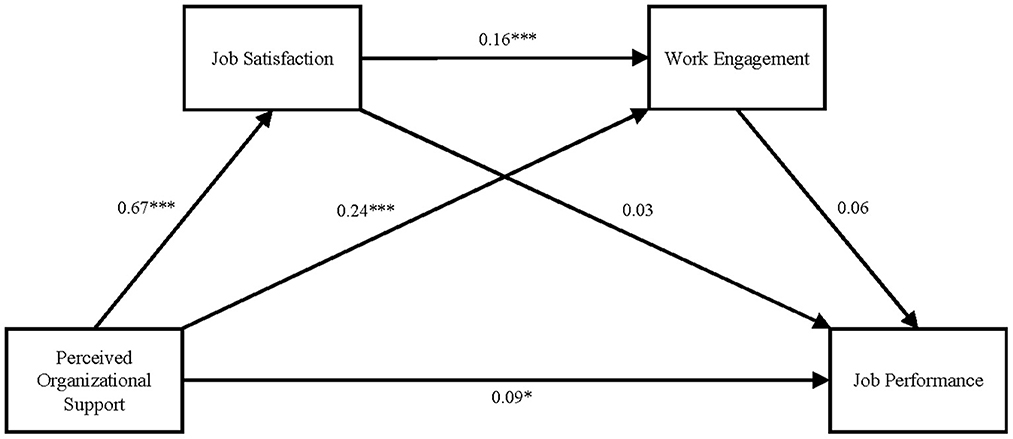

Therefore, before testing the chain mediating effect, the predictive variables in the equation were standardized, and collinearity diagnostics were performed. The results showed that the VIF values (5.050, 4.419, and 3.038) of all of the predictors were <10. Therefore, there was no serious collinearity in the data used for this study, indicating that these data were suitable for further mediation analysis (see Figure 1).

The process plug-in developed by Hayes was used to evaluate the 95% CI of the mediating effects of job satisfaction and work engagement on the relationship between perceived organizational support and job performance (the bootstrap sample size was 5,000). The results showed that perceived organizational support significantly positively predicted job performance, job satisfaction and work engagement (β = 0.09, p < 0.05; β = 0.67, p < 0.001; and β = 0.24, p < 0.001, respectively); that job satisfaction significantly predicted work engagement (β = 0.16, p < 0.001) but did not significantly predict job performance (β = 0.03, p > 0.05); and that work engagement did not significantly predict job performance (β = 0.06, p > 0.05).

Further testing of the mediating effect showed that the bootstrap 95% CI of the total indirect effect of job satisfaction and work engagement on the relationship between perceived organizational support and job performance was −0.0323 to 0.1134. This interval included 0, indicating that the chain mediating effect of job satisfaction and work engagement on the relationship between perceived organizational support and job performance was not significant. Thus, a chain mediation model was not established and Hypothesis (a) was supported.

3. Study 2

3.1. Subjects

Study 2 adopted the same online survey method as Study 1 and took place during the same period. However, unlike those in Study 1, the participants in Study 2 were full-time employees who work from home. A total of 189 questionnaires were distributed, and 180 valid questionnaires were returned, for an effective recovery rate of 95.23%. All participants signed informed consent forms prior to filling out the questionnaire. Participants were paid 10 yuan after completing the questionnaire. The study was reviewed and approved by Ethics Committee of Hubei Normal University. All participants signed informed consent prior to filling out the questionnaire.

3.2. Materials

Study 2 adopted the same four questionnaires as Study 1: the POSS, MSQ, UWES-9, and JPS.

3.3. Statistical analysis

Study 2 used the same statistical analysis approach as Study 1.

3.4. Results

3.4.1. Common method bias test

With the Harman single-factor method, perceived organizational support, job satisfaction, work engagement, and job performance were included in an exploratory factor analysis. Only 35.140% of the variance was explained by the largest factor, which was less than the critical value of 40%, indicating that there was no significant common method bias in this study.

3.4.2. Correlations among perceived organizational support, job satisfaction, work engagement, and job performance

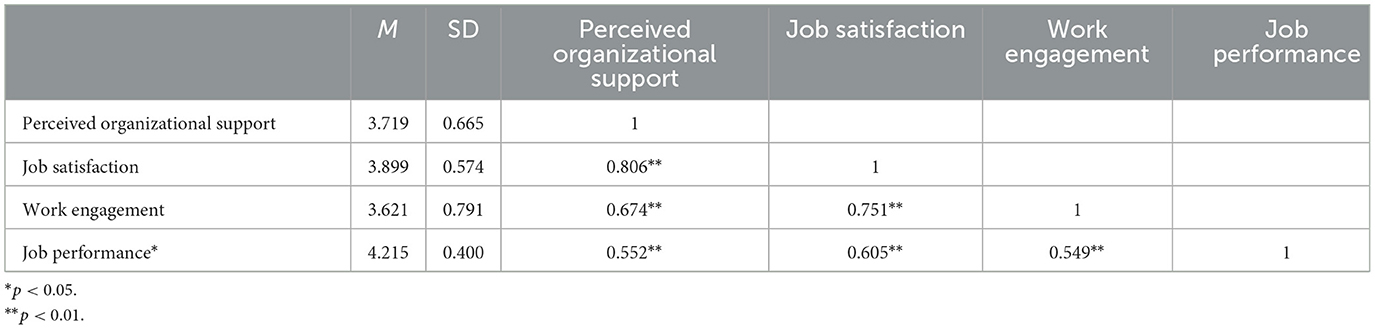

Table 2 presents the means (M), standard deviations (SD) and correlations. The highest mean is job performance (4.215). Pearson's product-moment correlation analysis was used to analyze perceived organizational support, job satisfaction, work engagement, and job performance (see Table 2). The results showed that ① perceived organizational support was significantly positively correlated with job satisfaction, work engagement and job performance (r = 0.806, p < 0.01; r = 0.674, p < 0.01; and r = 0.552, p < 0.01, respectively); ② work engagement was significantly positively correlated with job performance and job satisfaction (r = 0.549, p < 0.01 and r = 0.751, p < 0.01, respectively); and ③ job satisfaction was significantly positively correlated with job performance (r = 0.605, p < 0.01).

3.4.3. Relationship between perceived organizational support and job performance: A chain mediation model

The above analysis showed that there were significant correlations among the variables and the presence of possible collinearity. Therefore, before testing the chain mediating effect, the predictive variables in the equation were standardized, and collinearity diagnostics were performed. The results showed that the VIF values (2.949, 3.688, and 2.364) of all of the predictors were <10. Therefore, there was no serious collinearity in the data used for this study, indicating that these data were suitable for further mediation analysis.

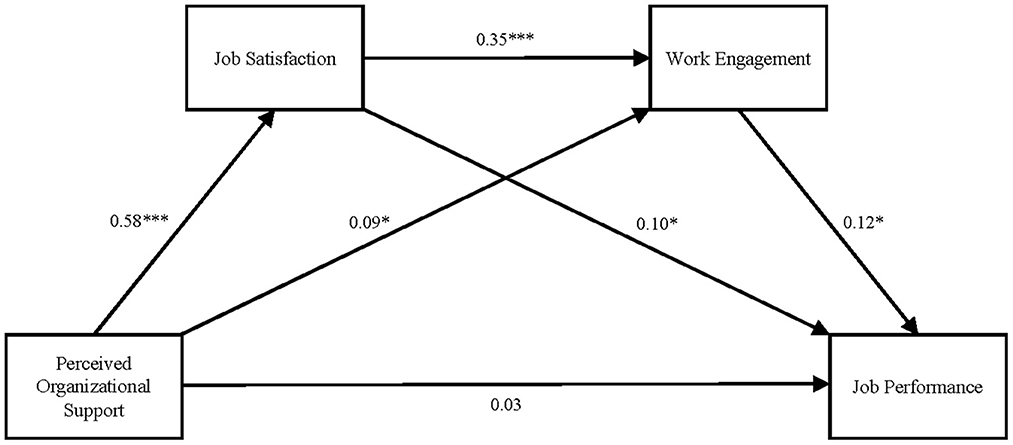

The process plug-in developed by Hayes was used to evaluate the 95% CI of the chain mediating effect of job satisfaction and work engagement on the relationship between perceived organizational support and job performance (the bootstrap sample size was 5,000), and a chain mediation model was established (see Figure 2). The results showed that perceived organizational support significantly positively predicted job satisfaction and work engagement (β = 0.58, p < 0.001 and β = 0.09, p < 0.05, respectively) but did not significantly predict job performance (β = 0.03, p > 0.05); that job satisfaction significantly predicted work engagement and job performance (β = 0.35, p < 0.001 and β = 0.10, p < 0.05, respectively); and that work engagement significantly predicted job performance (β = 0.12, p < 0.05).

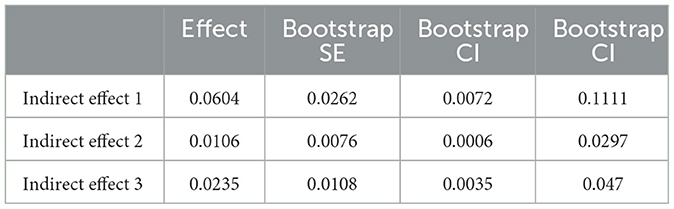

Further mediation analysis (see Table 3) showed that the bootstrap 95% CI of the total effect of job satisfaction and work engagement on the relationship between perceived organizational support and job performance was 0.0975–0.1538. This interval did not include 0; thus, job satisfaction and work engagement mediated the relationship of perceived organizational support and job performance. These two factors had a total indirect effect of 0.095, accounting for 75.18% of the total effect. This mediating effect was mainly composed of the following three paths: (1) perceived organizational support → job satisfaction → job performance [95% CI = (0.0072, 0.1111), standard error (SE) = 0.0262], under which the mediating effect is 0.0604, accounting for 48.05% of the total effect, and Hypothesis (b2) was supported; (2) perceived organizational support → work engagement → job performance [95% CI = (0.0006, 0.0297), standard error (SE) = 0.0076], under which the mediating effect was 0.0106, accounting for 8.43% of the total effect, and Hypothesis (b3) was supported; and (3) perceived organizational support → job satisfaction → work engagement → job performance [95% CI = (0.0035, 0.0470), standard error (SE) = 0.0108], under which the mediating effect was 0.0235, accounting for 18.70% of the total effect, and Hypotheses (b1) and (b4) were supported.

4. Discussion

This study explored the effect of perceived organizational support on job performance and the mediating effects of job satisfaction and work engagement. The results indicated that WFH influenced the relationship between perceived organizational support and job performance. In the condition of working in office, perceived organizational support directly affected job performance. In the condition of WFH, perceived organizational support indirectly affected job performance. In addition, in the condition of WFH, our results confirmed the separate mediating effects of job satisfaction and work engagement; moreover, job satisfaction and work engagement exerted a chain mediating effect on the relationship between perceived organizational support and job performance.

In our study, perceived organizational support was significantly positively correlated with organizational behavioral variables such as job performance, job satisfaction and work engagement, similar to previous research results. Thus, perceived organizational support is an important psychological variable that merits special attention in research and work applications.

Additionally, WFH influenced the relationship between perceived organizational support and job performance. The mechanism of action by which perceived organizational support influences job performance is controversial. Some researchers believe that perceived organizational support mainly affects job performance in a direct manner (30, 69). Other researchers believe that perceived organizational support influences job performance mainly through mediating factors such as job satisfaction, positive affectivity, affective commitment, organization-based self-esteem and organizational citizenship behavior (70–72). Different from previous research results, the conclusion of this study shows that the effect path of perceived organizational support on job performance is not fixed, which is affected by work mode. This study enriches the gap of research on WFH.

Regardless of this debate, perceived organizational support has a significant impact on job performance according to the principle of reciprocity. We believe that employees who work in office tend to regard organizational support as beneficial for organization. Based on the principle of reciprocity, when employees feel supported by their organization, they will be willing to make efforts to repay the organization for this perceived support, such as by improving job performance and increasing organizational citizenship behaviors. This exchange is more straightforward. Chen and Chen (34) uses affective support and instrumental support to explore the impact of perceived organizational support on job performance, and draws the conclusion that the direct effect is greater than the indirect effect, which is consistent with the conclusion of this study. In the condition of working in office, the direct effect of perceived organizational support on job performance is greater than in the condition of WFH.

However, employees believed that the organizational support experienced while working from home was more real than that experienced during working in office. On the one hand, employees who work from home are unable to communicate with their supervisors or colleagues in an informal and face-to-face manner due to their separate work location; thus, they usually rely on regular formal online meetings to exchange and share information and opinions. However, online communication can lead to information loss and low communicative efficiency (12). The above factors make it difficult for employees who work from home to achieve high-quality communication and objective exchanges, which may explain why there was a greater indirect effect of perceived organizational support on job performance than the direct effect. On the other hand, due to the lack of daily face-to-face interaction and communication with supervisors and colleagues, employees who work from home may experience social isolation or even envy of their colleagues (73, 74). In addition to limiting the freedom of movement, COVID-19 lockdowns are also associated with a variety of emotional challenges, including concrete fears of infection, frustration, and anger, as well as more generalized and severe symptoms of anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress (75, 76). The research of Armeli et al. (77) on 308 police patrolmen showed a nonsignificant correlation between perceived organizational support and job performance in subjects with weak socioemotional needs, which indicates that positive emotions may affect the relationship between perceived organizational support and job performance. Zhou and Bao (78) measured the perceived organizational support and only investigated the affective support, and concluded that the impact of perceived organizational support on job performance is mostly through indirect effects. Therefore, we believe that in the context of COVID-19, employees who work from home have greater emotional needs that can be met by perceived organizational support to increase job satisfaction and work engagement, thereby indirectly improving job performance.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, WFH is an effective governmental implementation to prevent further spread of disease; however, WFH impact both organizations and employees. It is urgent to identify ways to maintain job performance of employees who work from home. According to our results, perceived organizational support positively impacts employees' job performance in different work scenarios. This study explored the possible factors influencing job performance and validates and extends previous findings. Additionally, this study provides insight into the mechanism by which job satisfaction and work engagement influence the relationship between perceived organizational support and job performance and provides a possible direction for future to improve employees' job performance.

However, the current study has some limitations. First, its cross-sectional nature prevents. However us from drawing any conclusions about causal relationships. ThereforeHowever, the direction of relationships among perceived organizational support, job satisfaction, work engagement, and job performance cannot be determined. Future longitudinal studies should use cross-lagged analysis to examine bidirectional associations among these variables. Second, only two mediating variables, job satisfaction and work engagement, were examined in the present study. Future researchers should consider more mediating mechanisms, such as stress, anxiety, and leadership style, that influence the relationship between perceived organizational support and job performance. Finally, due to the limitations of data collection during a pandemic, all studied variables were derived from the same source. The scope and sources of data collection should be expanded in future studies.

5. Conclusions

In the condition of working in office, perceived organizational support directly affected job performance. In the condition of WFH, perceived organizational support indirectly affected job performance. And perceived organizational support affected job performance through the separate mediating effects of job satisfaction and work engagement. Additionally, in this condition, perceived organizational support affected job performance through the chain mediating effect of job satisfaction and work engagement. These findings extend our understanding of the association of perceived organizational support and job performance and enlighten enterprises on improving employees' job performance during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Hubei Normal University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

Conceptualization and writing—original draft: XL and YS. Data curation: XL. Funding acquisition and methodology: YJ. Project administration, supervision, and validation: YS. Writing—review and editing: XL, YJ, and YS. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was funded by General Project of Education of National Social Science Foundation, Project No. BIA220072.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Amirkhan JH. Stress overload in the spread of coronavirus. Anxiety Stress Coping. (2021) 34:121–9. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2020.1824271

2. Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. (2020) 395:912–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8

3. Kniffin KM, Narayanan J, Anseel F, Antonakis J, Ashford SP, Bakker AB, et al. Covid-19 and the workplace: implications, issues, and insights for future research and action. Am Psychol. (2021) 76:63–77. doi: 10.1037/amp0000716

4. Faulds DJ, Raju PS. The work-from-home trend: an interview with brian kropp. Bus Horiz. (2021) 64:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.bushor.2020.10.005

5. Gartner H. Gartner Hr Survey Reveals 41% of Employees Likely to Work Remotely at Least Some of the Time Post Coronavirus Pandemic. News Release, April (2020) 14.

6. Galanti T, Guidetti G, Mazzei E, Zappala S, Toscano F. Work from home during the Covid-19 outbreak: the impact on employees' remote work productivity, engagement, and stress. J Occup Environ Med. (2021) 63:e426–e32. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000002236

7. Chong S, Huang Y, Chang CD. Supporting interdependent telework employees: a moderated-mediation model linking daily Covid-19 Task setbacks to next-day work withdrawal. J appl psychol. (2020) 105:1408–22. doi: 10.1037/apl0000843

8. Gasparro R, Scandurra C, Maldonato NM, Dolce P, Bochicchio V, Valletta A, et al. Perceived job insecurity and depressive symptoms among italian dentists: the moderating role of fear of Covid-19. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:5338. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17155338

9. Truxillo DM, Cadiz DM, Brady GM. Covid-19 and Its implications for research on work ability. Work Aging Retire. (2020) 6:242–5. doi: 10.1093/workar/waaa016

10. Benetyte J. Building and sustaining trust in virtual teams within organizational context. Reg Form Dev Stud. (2013) 2:18–30. doi: 10.15181/rfds.v10i2.138

11. Daim TU, Ha A, Reutiman S, Hughes B, Pathak U, Bynum W, et al. Exploring the communication breakdown in global virtual teams. Int J Proj Manag. (2012) 30:199–212. doi: 10.1016/j.ijproman.2011.06.004

12. Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, Ernst JM, Burleson M, Berntson GG, Nouriani B, et al. Loneliness within a nomological net: an evolutionary perspective. J Res Pers. (2006) 40:1054–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2005.11.007

13. Ozcelik H, Barsade SG. No Employee an Island: workplace loneliness and job performance. Acad Manag J. (2018) 61:2343–66. doi: 10.5465/amj.2015.1066

14. Barhite BL. The Effects of Virtual Leadership Communication on Employee Engagement. Bowling Green, OH: Bowling Green State University (2017).

15. Mogale L, Sutherland M. Managing virtual teams in multinational companies. S Afr J Labour Relat. (2010) 34:7–24.

16. Mogilner C, Whillans A, Norton MI. Time, money, and subjective well-being. In:Diener E, Oishi S, editors. Handbook of Well-Being. Salt Lake City, UT: DEF (2018).

17. Kurtessis JN, Eisenberger R, Ford MT, Buffardi LC, Stewart KA, Adis CS. Perceived organizational support: a meta-analytic evaluation of organizational support theory. J Manag. (2015) 43:1854–84. doi: 10.1177/0149206315575554

18. Miao RT. Perceived organizational support, job satisfaction, task performance and organizational citizenship behavior in China. J Behav Appl Manag. (2011) 12:105–27. doi: 10.21818/001c.17632

19. Rhoades L, Eisenberger R. Perceived organizational support: a review of the literature. J appl psychol. (2002) 87:698–714. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.698

20. Campbell JP. Modeling the performance prediction problem in industrial and organizational psychology. In:Dunnette M, Hough L, editors. Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press (1990). p. 687–732.

21. Dharma Y. The effect of work motivation on the employee performance with organization citizenship behavior as intervening variable at bank aceh syariah. In: Proceedings of Micoms 2017. Emerald Reach Proceedings Series. 1. Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited (2018), p. 7–12. doi: 10.1108/978-1-78756-793-1-00065

22. Eisenberger R, Huntington R, Hutchison S, Sowa D. Perceived organizational support. J Appl Psychol. (1986) 71:500–7. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.71.3.500

23. Aselage J, Eisenberger R. Perceived organizational support and psychological contracts: a theoretical integration. J Organ Behav. (2003) 24:491–509. doi: 10.1002/job.211

24. Baran BE, Shanock LR, Miller LR. Advancing organizational support theory into the twenty-first century world of work. J Bus Psychol. (2012) 27:123–47. doi: 10.1007/s10869-011-9236-3

25. Eisenberger R, Stinglhamber F. Perceived Organizational Support: Fostering Enthusiastic and Productive Employees. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association (2011). doi: 10.1037/12318-000

26. Bellou V, Dimou M. The impact of destructive leadership on public servants' performance: the mediating role of leader-member exchange, perceived organizational support and job satisfaction. Int J Public Adm. (2022) 45:697–707. doi: 10.1080/01900692.2020.1868509

27. Jeong Y, Kim M. Effects of perceived organizational support and perceived organizational politics on organizational performance: mediating role of differential treatment. Asia Pac Manag Rev. (2022) 27:190–9. doi: 10.1016/j.apmrv.2021.08.002

28. Junça Silva A, Lopes C. Cognitive and affective predictors of occupational stress and job performance: the role of perceived organizational support and work engagement. J Econ Adm Sci. (2021). doi: 10.1108/JEAS-02-2021-0020

29. Sanliöz E, Sagbaş M, Sürücü L. The mediating role of perceived organizational support in the impact of work engagement on job performance. Hosp Top. (2022) 1–14. doi: 10.1080/00185868.2022.2049024

30. Eisenberger R, Armeli S, Rexwinkel B, Lynch PD, Rhoades L. Reciprocation of perceived organizational support. J Appl Psychol. (2001) 86:42–51. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.86.1.42

31. Wayne SJ, Shore LM, Bommer WH, Tetrick LE. The role of fair treatment and rewards in perceptions of organizational support and leader-member exchange. Journal of Applied Psychology. (2002) 87:590–8. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.3.590

32. Riggle RJ, Edmondson DR, Hansen JD. A meta-analysis of the relationship between perceived organizational support and job outcomes: 20 years of research. J Bus Res. (2009) 62:1027–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2008.05.003

33. Shanock LR, Eisenberger R. When supervisors feel supported: relationships with subordinates' perceived supervisor support, perceived organizational support, and performance. J Appl Psychol. (2006) 91:689–95. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.91.3.689

34. Chen Z, Chen J. The direct and indirect effects of knowledge-worker's perceived organizational support to their job performance. Ind Eng Manag. (2008) 1:99–104. doi: 10.19495/j.cnki.1007-5429.2008.01.021

35. Ford MT, Wang Y, Jin J, Eisenberger R. Chronic and episodic anger and gratitude toward the organization: relationships with organizational and supervisor supportiveness and extrarole behavior. J Occup Health Psychol. (2018) 23:175–87. doi: 10.1037/ocp0000075

36. Jain AK. The mediating role of job satisfaction in the relationship of vertical trust and distributed leadership in health care context. J Model Manag. (2016) 11:722–38. doi: 10.1108/JM2-10-2014-0077

37. Giri VN, Pavan Kumar B. Assessing the impact of organizational communication on job satisfaction and job performance. Psychol Stud. (2010) 55:137–43. doi: 10.1007/s12646-010-0013-6

38. Bernarto I, Sudibjo N, Bachtiar D, Suryawan I, Purwanto A, Asbari M. Effect of transformational leadership, perceived organizational support, job satisfaction toward life satisfaction: evidences from indonesian teachers. Int J Adv Sci Technol. (2020) 29:5495−503.

39. Ahmad ZA, Yekta ZA. Relationship between perceived organizational support, leadership behavior, and job satisfaction: an empirical study in Iran. Intang Cap. (2010) 6:162–84. doi: 10.3926/ic.2010.v6n2.p162-184

40. Katebi A, HajiZadeh MH, Bordbar A, Salehi AM. The relationship between “job satisfaction” and “job performance”: a meta-analysis. Glob J Flex Syst Manag. (2022) 23:21–42. doi: 10.1007/s40171-021-00280-y

41. Dinc MS, Kuzey C, Steta N. Nurses' job satisfaction as a mediator of the relationship between organizational commitment components and job performance. J Workplace Behav Health. (2018) 33:75–95. doi: 10.1080/15555240.2018.1464930

42. Baluyos GR, Rivera HL, Baluyos EL. Teachers' job satisfaction and work performance. Open J Soc Sci. (2019) 7:206–21. doi: 10.4236/jss.2019.78015

43. Schaufeli WB, Salanova M, González-Romá V, Bakker AB. The measurement of engagement and burnout: a two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J Happiness Stud. (2002) 3:71–92. doi: 10.1023/A:1015630930326

44. Demerouti E, Sanz-Vergel A. Burnout and work engagement: the Jd-R approach. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav. (2014) 1:389–411. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091235

45. Xu Z, Yang F. The impact of perceived organizational support on the relationship between job stress and burnout: a mediating or moderating role? Curr Psychol. (2021) 40:402–13. doi: 10.1007/s12144-018-9941-4

46. Kinnunen U, Feldt T, Mäkikangas A. Testing the effort-reward imbalance model among finnish managers: the role of perceived organizational support. J Occup Health Psychol. (2008) 13:114–27. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.13.2.114

47. Saks AM. Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement revisited. J Organ Eff People Perform. (2019) 6:19–38. doi: 10.1108/JOEPP-06-2018-0034

48. Rodríguez-Muñoz A, Sanz-Vergel AI, Demerouti E, Bakker AB. Engaged at work and happy at home: a spillover-crossover model. J Happiness Stud. (2014) 15:271–83. doi: 10.1007/s10902-013-9421-3

49. Schaufeli W, Van Rhenen W. Over de rol van positieve en negatieve emoties bij het welbevinden van managers: een studie met de job-related affective well-being scale (Jaws). Gedrag Organ. (2006) 19:323–44. doi: 10.5117/2006.019.004.002

50. Seppälä P, Mauno S, Kinnunen ML, Feldt T, Juuti T, Tolvanen A, et al. Is work engagement related to healthy cardiac autonomic activity? Evidence from a field study among Finnish women workers. J Posit Psychol. (2012) 7:95–106. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2011.637342

51. Sonnentag S, Mojza EJ, Demerouti E, Bakker AB. Reciprocal relations between recovery and work engagement: the moderating role of job stressors. J Appl Psychol. (2012) 97:842–53. doi: 10.1037/a0028292

52. Ten Brummelhuis L. Staying engaged during the week: the effect of off-job activities on next day work engagement. J Occup Health Psychol. (2012) 17:445–55. doi: 10.1037/a0029213

53. Bakker A. Building engagement in the workplace. In:Cooper C, Burke R, editors. The Peak Performing Organization. Abingdon, UK: Routledge (2009), p. 50–72. doi: 10.4324/9780203971611.ch3

54. Hillman AJ, Nicholson G, Shropshire C. Directors' multiple identities, identification, and board monitoring and resource provision. Organ Sci. (2008) 19:441–56. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1080.0355

55. Kreiner GE, Hollensbe EC, Sheep ML. Where is the “me” among the “we”? Identity work and the search for optimal balance. Acad Manag J. (2006) 49:1031–57. doi: 10.5465/amj.2006.22798186

56. Halbesleben JRB, Wheeler AR. The relative roles of engagement and embeddedness in predicting job performance and intention to leave. Work Stress. (2008) 22:242–56. doi: 10.1080/02678370802383962

57. Tisu L, Lup?a D, Vîrgă D, Rusu A. Personality characteristics, job performance and mental health: the mediating role of work engagement. Pers Individ Differ. (2020) 153:109644. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2019.109644

58. Avolio BJ, Zhu W, Koh W, Bhatia P. transformational leadership and organizational commitment: mediating role of psychological empowerment and moderating role of structural distance. J Organ Behav. (2004) 25:951–68. doi: 10.1002/job.283

59. Stamper CL, Johlke MC. The impact of perceived organizational support on the relationship between boundary spanner role stress and work outcomes. J Manag. (2003) 29:569–88. doi: 10.1016/S0149-2063_03_00025-4

60. Lan T, Chen M, Zeng X, Liu T. The influence of job and individual resources on work engagement among chinese police officers: a moderated mediation model. Front Psychol. (2020) 11:497. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00497

61. Ling WQ, Yang HJ, Fang LL. Perceived organizational support(Pos) of the employees. Acta Psychol Sin. (2006) 38:281–7.

62. Weiss DJ, Dawis RV, England GW, Lofquist LH. Construct validation studies of the minnesota importance questionnaire. Minn Stud Vocat Rehabil. (1964) 18:1–76.

63. Schaufeli WB, Bakker AB, Salanova M. The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: a cross-national study. Educ Psychol Meas. (2006) 66:701–16. doi: 10.1177/0013164405282471

64. Zhang YW, Gan YQ. The Chinese version of utrecht work engagement scale: an examination of reliability and validity. Chin J Clin Psychol. (2005) 13:268–70.

65. Li Y, Wang Y, Yang J. Research on influencing of self-efficacy job involvement on job performance of high-tech enterprise R&D staff. Sci Sci Manag S Tianjin. (2015) 36:173–80.

66. Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press (2013).

67. Erceg-Hurn DM, Mirosevich VM. Modern robust statistical methods: an easy way to maximize the accuracy and power of your research. Am Psychol. (2008) 63:591–601. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.63.7.591

68. Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J appl psychol. (2003) 88:879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

69. Kaufman JD, Stamper CL, Tesluk PE. Do supportive organizations make for good corporate citizens? J Manag Issues. (2001) 13:436–49. Available online at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40604363

70. Chiang C-F, Hsieh T-S. The impacts of perceived organizational support and psychological empowerment on job performance: the mediating effects of organizational citizenship behavior. Int J Hosp Manag. (2012) 31:180–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2011.04.011

71. Arshadi N, Hayavi G. The effect of perceived organizational support on affective commitment and job performance: mediating role of obse. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. (2013) 84:739–43. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.06.637

72. Guan X, Sun T, Hou Y, Zhao L, Luan Y-Z, Fan L-H. The relationship between job performance and perceived organizational support in faculty members at Chinese universities: a questionnaire survey. BMC Med Educ. (2014) 14:50. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-14-50

73. Gajendran RS, Harrison DA. The good, the bad, and the unknown about telecommuting: meta-analysis of psychological mediators and individual consequences. J Appl Psychol. (2007) 92:1524–41. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.92.6.1524

74. Morganson VJ, Major DA, Oborn KL, Verive JM, Heelan MP. Comparing telework locations and traditional work arrangements. J Manag Psychol. (2010) 25:578–95. doi: 10.1108/02683941011056941

75. Altena E, Baglioni C, Espie CA, Ellis J, Gavriloff D, Holzinger B, et al. Dealing with sleep problems during home confinement due to the Covid-19 outbreak: practical recommendations from a task force of the European Cbt-I ACADEMY. J Sleep Res. (2020) 29:e13052. doi: 10.1111/jsr.13052

76. Liu S, Yang L, Zhang C, Xiang YT, Liu Z, Hu S, et al. Online mental health services in china during the Covid-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry. (2020) 7:e17–e8. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30077-8

77. Armeli S, Eisenberger R, Fasolo P, Lynch P. Perceived organizational support and police performance: the moderating influence of socioemotional needs. J Appl Psychol. (1998) 83:288–97. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.83.2.288

Keywords: perceived organizational support, job satisfaction, work engagement, job performance, work from home, COVID-19

Citation: Liu X, Jing Y and Sheng Y (2023) Work from home or office during the COVID-19 pandemic: The different chain mediation models of perceived organizational support to the job performance. Front. Public Health 11:1139013. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1139013

Received: 06 January 2023; Accepted: 10 February 2023;

Published: 03 March 2023.

Edited by:

Dimitrios Papagiannis, University of Thessaly, GreeceReviewed by:

Shujie Guo, Henan Provincial People's Hospital, ChinaMaja Rožman, University of Maribor, Slovenia

Copyright © 2023 Liu, Jing and Sheng. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Youyu Sheng, c2hlbmd5b3V5dTk2QGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Xiong Liu1

Xiong Liu1 Yumei Jing

Yumei Jing Youyu Sheng

Youyu Sheng