- Centre for Global Health and Equity, Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

Refugees experience health inequities resulting from multiple barriers and difficulties in accessing and engaging with services. A health literacy development approach can be used to understand health literacy strengths, needs, and preferences to build equitable access to services and information. This protocol details an adaptation of the Ophelia (Optimizing Health Literacy and Access) process to ensure authentic engagement of all stakeholders to generate culturally appropriate, needed, wanted and implementable multisectoral solutions among a former refugee community in Melbourne, Australia. The Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ), widely applied around the world in different population groups, including refugees, is usually the quantitative needs assessment tool of the Ophelia process. This protocol outlines an approach tailored to the context, literacy, and health literacy needs of former refugees. This project will engage a refugee settlement agency and a former refugee community (Karen people origin from Myanmar also formerly knowns as Burma) in codesign from inception. A needs assessment will identify health literacy strengths, needs, and preferences, basic demographic data and service engagement of the Karen community. This community will be engaged and interviewed using a semi-structured interview based on the Conversational Health Literacy and Assessment Tool (CHAT) will cover supportive professional and personal relationships, health behaviors, access to health information, use of health services, and health promotion barriers and support. Using the needs assessment data, vignettes portraying typical individuals from this community will be developed. Stakeholders will be invited to participate in ideas generation and prioritization workshops for in-depth discussion on what works well and not well for the community. Contextually and culturally appropriate and meaningful action ideas will be co-designed to respond to identified health literacy strengths, needs, and preferences of the community. This protocol will develop and test new and improved methods that are likely to be useful for community-based organizations and health services to systematically understand and improve communication, services and outcomes among disadvantaged groups, particularly migrants and refugees.

1. Introduction

The complexity of health issues arising from the movement of refugees around the world poses challenges for health systems. Former refugee groups often experience challenges in accessing and using healthcare services because of economic and legal limitations, language barriers, lack of knowledge about their health rights, and other socio-cultural, administrative, and institutional barriers (1–3). Consequently, former refugee communities often tend to be overlooked by mainstream health programs and so do not receive fit-for-purpose health education and information. These systemic barriers result in delayed or no access to health services (4). Each year, ~4,000 refugees settle in the Australian State of Victoria through the humanitarian program (5). In Victoria, as with many regions around the world, the size of refugee populations is increasing, leading to the need for improved processes for health services to understand and respond to their health issues.

Globally, there is a limited research on the health issues faced by refugees after they have resettled in a destination country, including Australia (6–10). Refugees have relatively poor health and encounter barriers to accessing healthcare services. These barriers include the lack of culturally and linguistically sensitive health services and information, which cause difficulties in navigating the health system and for understanding or interpreting health information (11–13). The pre-migration, migration and resettlement experiences of refugees have multiple impacts on their health and wellbeing. These impacts vary across individuals, families, and communities depending on country of origin, duration of the migration experience, and their pre-existing health behaviors and ailments (14). Previous traumatic experiences of refugees have a persistent impact on their health and wellbeing after arrival in host countries (15, 16). Refugees may have experienced interruptions in access to healthcare services in their country of origin due to war and conflict (17). Consequently, they may have inadequately managed diseases, injuries, as well as have ongoing mental health issues due to trauma (18–20). In addition to experiencing conflict, poverty and variable access to health services, the settlement process in the host countries may aggravate health inequities and increase exposure to various health risks. The factors leading to the poor health of refugees in destination countries are well documented (21–23). However, a deeper understanding is required to inform health and community services about ways to better respond to these identified needs (24).

Researchers, public health practitioners and service providers across the health system attempt to identify and eliminate disparities in the health and wellbeing of former refugees. However, it is challenging to design approaches that examine underlying causes and worldviews that influence cultural beliefs, norms, values, health behaviors, and expectations (25). While a focus on these has raised awareness of the needs of these communities, much of the work to date has focused on deficits that refugees might have (e.g., what they can't do or are lacking in) (26). This has led to stereotyping such refugees as “hard to reach” (27, 28). A deficit approach, with a predilection for identifying weaknesses and problems limits research processes to capture potential strengths such as community values, resilience, tacit knowledge, skills and competencies that may be used to build a more comprehensive understanding of a population and inform the development of wholistic solutions.

Health literacy is a multidimensional concept that has recently evolved to be a valuable problem-solving tool to assess and understand both the strengths and challenges of individuals and communities including those who do not access services (26, 29–31). According to the WHO, health literacy represents “the personal knowledge and competencies that accumulate through daily activities and social interactions and across generations. Personal knowledge and competencies are mediated by the organizational structures and availability of resources that enable people to access, understand, appraise and use information and services in ways that promote and maintain good health and wellbeing for themselves and those around them” (31, 32). Different groups of people may have different sets of health literacy strengths, needs and preferences. This has important implications for understanding what is really required to determine how to build services and initiatives that may help different communities, especially those who come from diverse cultures, including refugees (26, 33, 34).

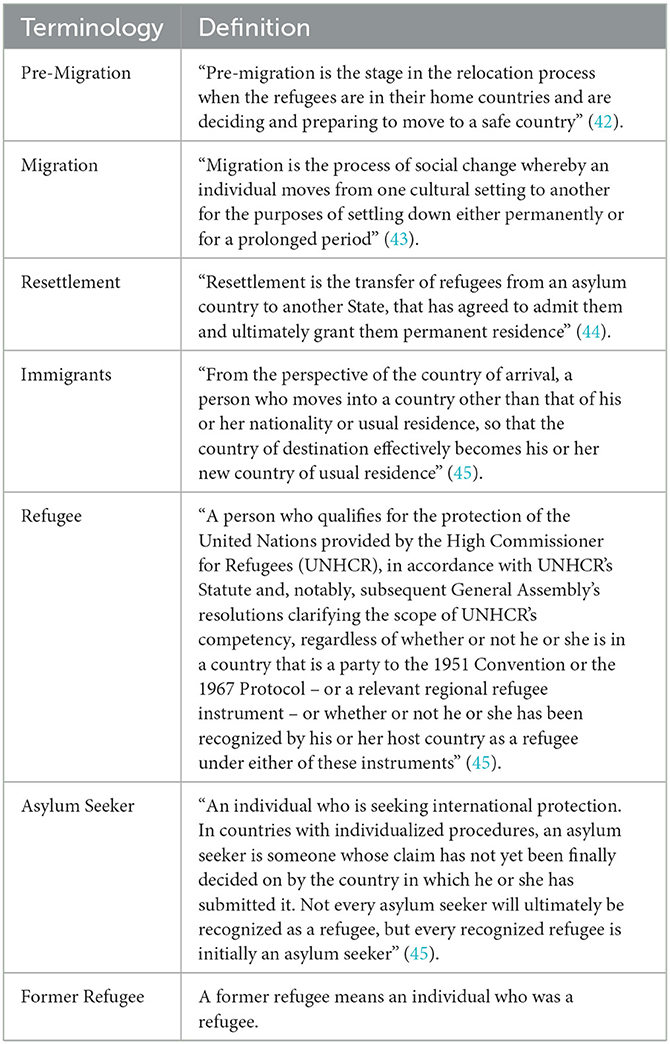

Health literacy initiatives are particularly important for refugees to facilitate uptake of available health services and information (35). Few studies provide insights into health literacy initiatives suitable for refugee populations (36–39). The limited research suggests that needs assessments, using community participatory approaches and plain language are useful (40). However, there are very few studies about methods for identifying and addressing the health literacy needs in the refugee setting. A systematic review of randomized control trials was conducted to identify methods and outcomes that aimed to improve health literacy and behaviors of refugee communities (41). Overall, the studies in the field of refugees' health literacy were highly heterogenous in terms of study groups (e.g., immigrants, refugees, and asylum seekers) (see Table 1 for migration terminology), research design, metrics, methods, and overall methodologies and did not critically assess the health literacy needs and local knowledge of refugee groups (41).

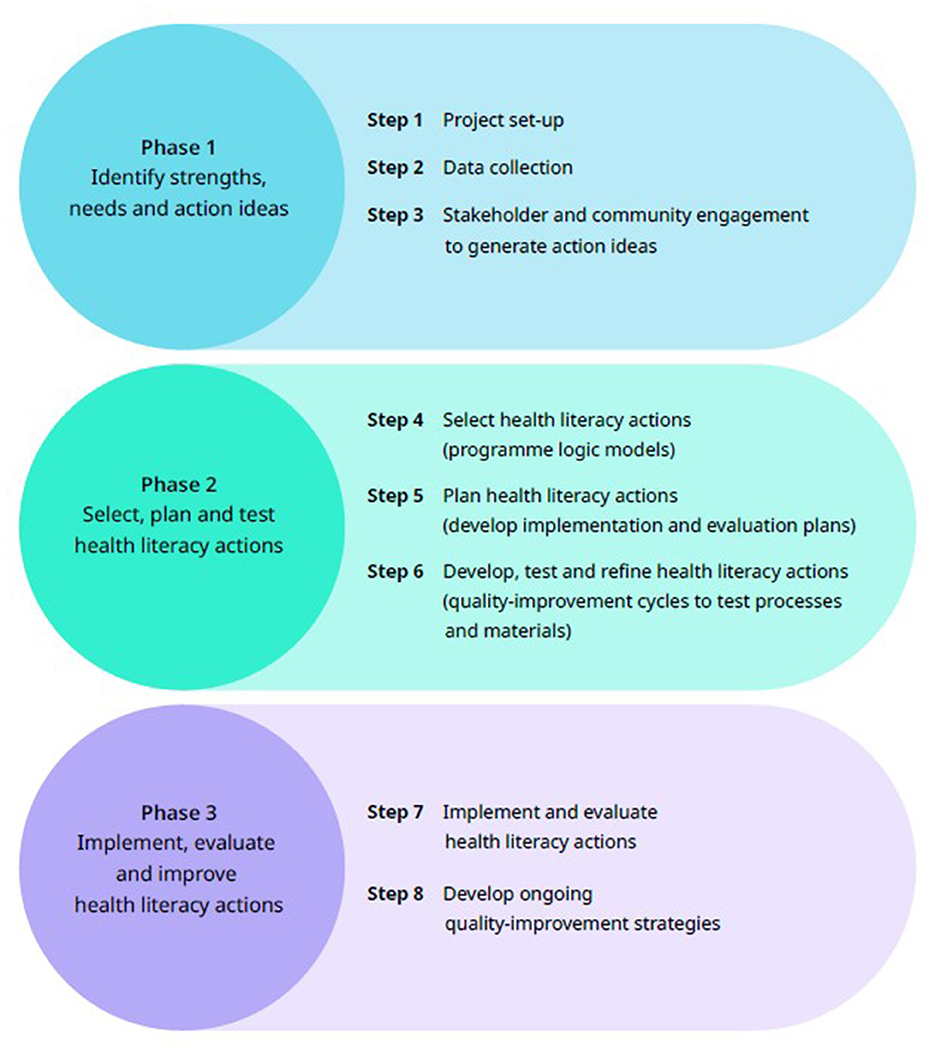

Robust research methods that recognize and address health literacy diversity, and consider the contexts of communities, are necessary to develop fit-for-purpose and sustainable solutions to health disparities (46). The Ophelia (Optimizing Health Literacy and Access) process engages community members to help identify and respond to their health literacy strengths and needs. The Ophelia process was developed in Australia (29) and further tested and refined in different contexts and several countries (2, 33, 47–51). It has three phases (Figure 1): Phase 1: needs assessment; Phase 2: co-design and testing of health literacy actions; Phase 3: implementation, evaluation and continuous quality improvement. Typically, the needs assessment in Ophelia Phase 1 uses a multi-dimensional health literacy assessment tool – the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ) – to investigate the diverse health literacy strengths, needs and preferences of groups and communities. Collaboration is undertaken across stakeholder groups, such as community leaders and members, health professionals, managers, and service users to select, test and implement health literacy actions in Phases 2 and 3.

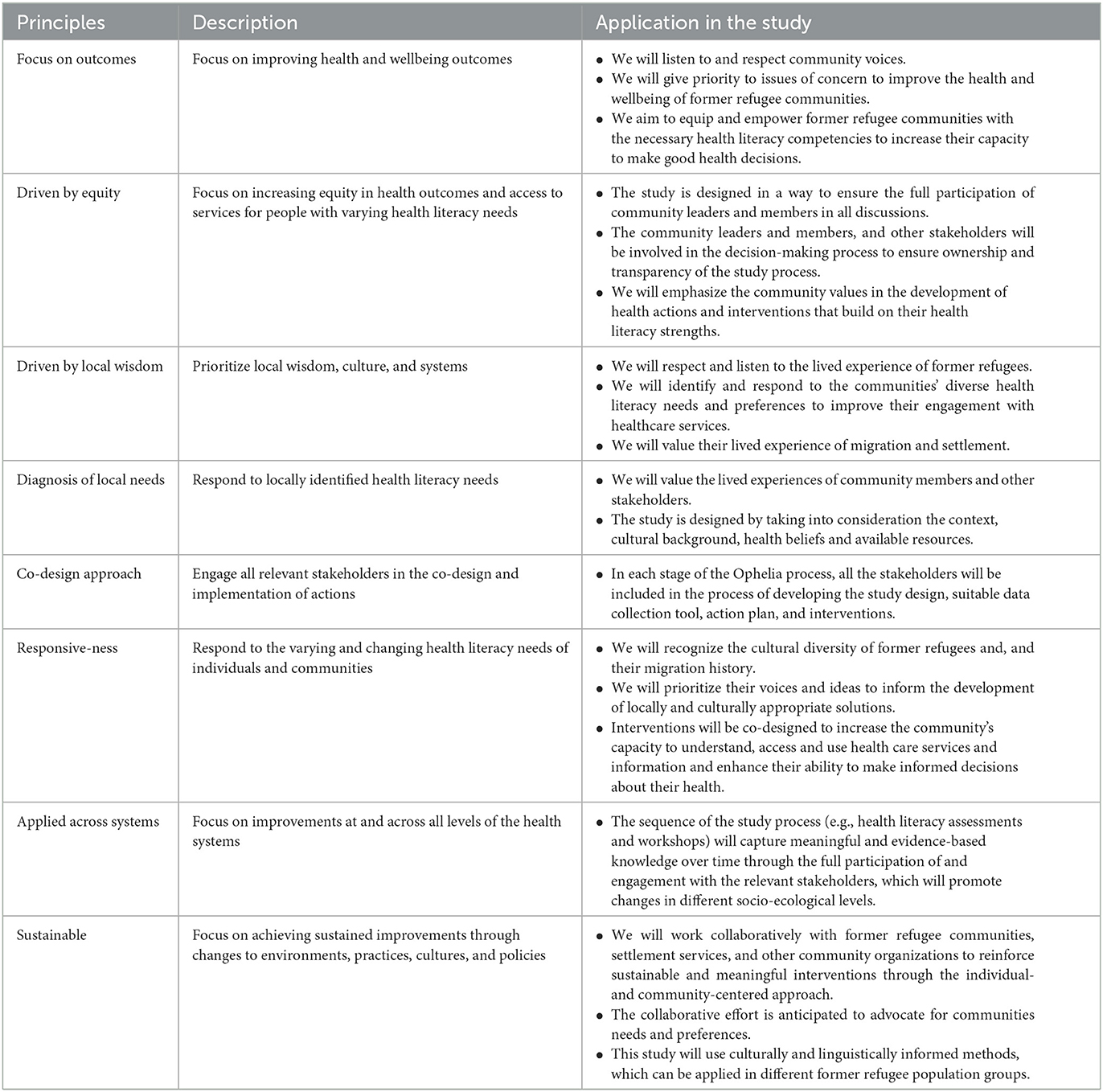

This study protocol describes a health literacy development project that aims to collaboratively identify the health literacy strengths, needs and preferences of a former refugee community living in Melbourne, Australia, and co-design health literacy actions that are culturally and linguistically relevant, meaningful and useful to the community. The Ophelia process will be applied in accordance with the eight Ophelia principles that have been operationalised for this research (Table 2). Health literacy actions will have a strong focus on building the responsiveness of health and community services to support and develop the health literacy of the community. It is expected that the project outcomes will increase the capacity of community members to access, understand, appraise, and use health information and services and enhance their confidence to make informed decisions about their health.

Table 2. Principles of the Ophelia process and the application in this study [Adapted from Osborne et al. (32)].

The setting for this study is a Karen community (i.e., refugees from the country of Myanmar formerly known as Burma) who were identified by AMES Australia, a refugee settlement agency that agreed to form a partnership with the Center for Global Health and Equity, Swinburne University of Technology, including to engage with the Ophelia guiding principles (see Table 2). Consultation then began with the Karen community leaders and members to explore their willingness to participate in a health project. Following endorsement by the Karen community leaders and members and AMES Australia, the project aim was discussed and culturally and linguistically appropriate processes were explored.

2. Methods and analysis

2.1. Project governance

An Advisory Group was established with community leaders to advise on the aims, purpose and community engagement processes, including recruitment. This group provides advice about relevant tribal and ethnic affiliations and ensures diverse groups will be encouraged to take part.

2.2. Setting and participants

The Karen community groups residing in Melbourne mainly originate from rural areas in Burma/ Myanmar. The participants will be recruited by invitation through the Advisory Group, and community and professional networks. Informed consent will be obtained from all participants.

Community members will be invited to participate in semi-structured interviews and/or attend ideas generation and prioritization workshops. The inclusion criteria include people who are:

• A former refugee from Burma/Myanmar;

• Aged 18 years and above; and

• Cognitively able to provide informed consent.

Service providers such as health and social care workers, health practitioners, language support providers, members from the partner organization (AMES Australia), community leaders and clinicians, community nurses, and people who provide direct or indirect services (e.g., policymakers) will be invited to participate in ideas generation and prioritization workshops.

2.3. Study design

The study design will be informed by the Ophelia process (see below). The general timeline below provides an approximate schedule for the project.

• July 2021 to 2022 – data collection and analysis (includes interviews, ideas generation workshops, and corresponding analyses)

• July 2022 to 2023 – intervention development, implementation, and evaluation (includes intervention co-design and implementation, and establishing meaningful ongoing monitoring and evaluation strategies).

2.3.1. Phase 1: Identifying the local health literacy strengths, needs and preferences

The Ophelia process is usually conducted using a quantitative data collection method – the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ), which has 44 items in nine scales (four to six items per scale) (30, 33). Cluster analysis is used to analyze the HLQ data, which can be useful to uncover the mechanisms that enable or inhibit groups of people within a population from engaging with health information and services (52). However, quantitative data collection is not appropriate or relevant for every community or culture (26). For example, studies in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities in Australia identified that yarning methodology (First Nations cultural form of conversation) is an effective and respectful data gathering tool for the Australian First Nations cultures. Yarning nurtures the sharing of knowledge and stories through in-depth discussions (53). This interview technique is a culturally appropriate method of communication transfer to help the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community with chronic disease education and self-management (54). The Karen community in Melbourne has limited English language, as well as limited reading ability in their own language, and there is risk of epistemic injustice if a health literacy measurement instrument that is not meaningful or relevant to their culture is used (26). To minimize the potential for biased data, an open interview technique will be used in this study instead of the HLQ.

To ensure the interview guide captures health literacy dimensions, the Conversational Health Literacy Assessment Tool (CHAT) will be used. The CHAT uses a series of open-ended-questions to facilitate conversations about the ways in which people access, understand, appraise and use health information and services (55, 56). The CHAT consists of five topics, each with 2 questions (total of 10 questions):

1) Supportive professional relationships

2) Supportive personal relationships

3) Health information access and comprehension

4) Current health behaviors

5) Health promotion barriers and support

The CHAT interview guide will be translated into the Karen language by the AMES Karen community liaison officer. The translated CHAT interview guide will be pilot tested with up to 5 community members to check understanding of the questions, issues with the translation, and relevance to the community needs and experiences. Feedback from the community members will be used to inform revisions to the translated questions. Semi-structured interviews will take about 30 min and will be undertaken with the assistance of bilingual workers. Up to 30 community members will be invited to participate in interviews.

Using the needs assessment data, vignettes (evidence-based case studies derived from study data) that portray typical individuals from the target community will be developed. Vignettes are realistic descriptions of profiles of health literacy strengths, needs, and preferences that influence the abilities of groups of people in the community to understand, access, appraise and use health information and services (2). The vignettes will be extensively revised and vetted by participants to ensure they portray the daily lived experiences of the target community members (57, 58).

2.3.1.1. Vignettes development

The health literacy needs assessment data from the interviews and participant demographic data will be used to construct vignettes about community members' experiences and health literacy strengths, needs, and preferences. It is expected that the thematic analysis will yield between 5 and 10 different profiles. Vignettes will be developed for the different health literacy profiles. The social and demographic data will provide narrative information about the contexts in which these experiences may take place. In this way, the vignettes are built to represent the characteristics and challenges of each health literacy profile without representing or revealing specific details about any one individual.

2.3.1.2. Ideas generation workshop

The vignettes will be presented to stakeholders in each workshop with 6 to 10 participants over 2 h. Separate workshops will be held for community members and direct service providers. Language interpretation support will be provided by bilingual workers. In each workshop, participants will be asked 4 key questions based on the vignettes:

1. Do you know people who have had, or have you had, experiences similar to the person in this story [participant is a community member] or Do you see people like this in your community or services? [participant is a service provider]

2. What sorts of problems is this person experiencing in relation to their health?

3. What strategies could be used to help this person?

4. If there were many people like this in your community, what could health services and community organizations do to help?

The Ideas Generation Workshops bring together researchers, community leaders and members, and other stakeholders to participate in discussions about issues facing the community, and to identify what works well and what does not work well for the community. This technique, with a focus on lived experiences embodied in the vignettes, emotes genuine engagement as workshop participants relate to the vignettes (32, 59, 60). Additionally, engaging various stakeholders in the discussion will increase the potential for collaborative efforts to respond to the identified needs using existing resources according to the health literacy strengths, needs and preferences of the community.

2.3.2. Phase 2: Select, plan, develop, and test selected health literacy actions

An action-oriented program logic model and theory will be developed based on the workshop outputs with categorization of short- term, intermediate and long-term outcomes where appropriate (32). This logic model will be co-designed with the key stakeholders to describe the mechanisms for how the generated action ideas are intended to work (61).

2.3.3. Phase 3: Implementation, evaluation and ongoing monitoring of health literacy actions

This phase involves implementation of the chosen health literacy actions from Phase 2, which include improving the local uptake, effectiveness, and sustainability of health actions using quality improvement cycles. AMES Australia will evaluate and examine the intended outcomes (short-term, intermediate, and long-term) of the chosen health actions, and refine the processes to enhance responsiveness and effectiveness, capacity building, and sustainability of the health actions. A post-implementation evaluation tool will be identified and used to evaluate the outcomes (32).

2.4. Data analysis

The data will be synthesized in two stages: analysis of the semi-structured interviews and analysis of the data generated from the workshops.

2.4.1. Semi- structured interviews

The narratives from the semi-structured interviews, guided by the CHAT questions, will be coded, themed and analyzed deductively (62–65), whilst also allowing for inductive generation of codes identified in the data. The codes will be categorized and themes will be developed from the categories.

The themes will be used to generate groups of similar health literacy profiles across the interviewed participants. The coded data, within the themes, will be scored according to challenges experienced by participants. A score 3 of 3 means the person experienced fewer challenges; a score of 2 means the person experienced a moderate number of challenges; and a score of 1 means the person had many challenging experiences. The scoring of the challenges will be based on the number and severity of challenges. The severity of the challenges will be determined based on participants' expressions, communication styles, tone of voice and behaviors while responding to the interview questions. Some participants may not give any responses that are relevant to the identified theme, and these will be categorized as “no response”. Scores for each theme will be summed. The total scores will be grouped from the highest scores to the lowest scores. Higher scores suggest potential strengths, and lower scores indicate potential challenges. The demographic data will be linked to each individual to identify demographic differences in terms of education, age, and gender. The health literacy profile of the interviewed community members will be used to develop vignettes.

2.4.2. Ideas generation workshop

In each workshop participants will discuss up to 4 vignettes. The ideas will be grouped into 3 categories of health literacy actions: (1) actions related to what community members can do (e.g., increasing confidence of individuals in using their knowledge and skills of local culture, beliefs, resources, and environment); (2) actions related to what community or local health organizations can do (e.g., understanding local wisdom of the community, providing culturally sensitive services); and (3) policy level actions (e.g., actions that influence organizational policy and decision making processes) (29). Data analysis will be led by one researcher with iterative review and checking of congruency of codes by other members from the team including the community leaders and AMES Australia staff.

Following the thematic analysis of the health literacy actions, a prioritization workshop will be conducted with key stakeholders, including community members and leaders and AMES Australia staff. A health literacy development and implementation plan will be developed.

3. Discussion

Health service organizations and settlement agencies who work closely with former refugees experience challenges in identifying, understanding, and responding in culturally responsive ways to the diverse health literacy needs of this cohort. Given that substantial health disparities in former refugee communities are frequently observed (23), new ways to support communities and health authorities to understand the health needs and to take action are warranted. Simply providing health information in different languages for these communities is not sufficient to enhance their engagement with the health services, reduce health inequities, and improve their health outcomes (66–68).

This protocol details an adaptation of the Ophelia process such that it can accelerate a settlement agency's engagement with their community and develop an in depth understanding about how to best generate and implement health literacy development actions and programs that are locally relevant and implementable. Importantly, Ophelia provides an authentic process for engagement and co-design with diverse stakeholders. The Ophelia process has been successfully adapted to fit many projects in different countries around the world (32) and previous Ophelia protocols for studies in different contexts have been published (29, 69, 70) including a study about refugees in Portugal (2). This study will be conducted in accordance with the eight principles of the Ophelia process (Table 2) which may mean that during the co-design phases of the project, some protocol changes may be necessary to suit the cultural and linguistic needs of the community, available resources, and other contextual circumstances.

Potential limitations to this study protocol include inadequate time for consultation and code sign with the agency and community members, limited reach into the full range of refugee groups, and reluctance of refugee groups to express any concerns they may have in their new host country. The governance of the Advisory Group and adherence to the Ophelia principles are, however, likely to mitigate these potential limitations.

The Ophelia process recommends application of a formal multidimensional questionnaire [i.e., the Health Literacy Questionnaire (30)]. However, this type of tool, whether administered in written or oral form, may miss key health literacy elements of the refugee settlement experience, and may be an unacceptable burden to people who are illiterate in the own language, or come from an oral language tradition (26). Consequently, this protocol includes a semi-structured qualitative interview using the CHAT. If successful, this protocol will increase the reach and impact of Ophelia into wider settings, including among groups often not authentically included in research and program development activities. The development and continuous improvement of equitable healthcare services require responsiveness to the local nuances of a community, development of bespoke or tailored health literacy actions, and careful evaluation of the acceptability, uptake and impact of public health responses (32).

4. Conclusion

This study will support an organization to understand and respond to the factors that affect a community's ability to understand, access, appraise, and use health information and services to make informed decisions about their health. This protocol applies authentic co-design to develop locally appropriate interventions based on diverse stakeholders' experiences and identified needs. The outcomes of this study are anticipated to be useful for various community-based organizations and policy makers to reduce health disparities in former refugee and other communities that experience vulnerability and marginalization and to create enabling environments that enhance meaningful engagement with and equitable access to health information and services.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Swinburne University of Technology Human Research Ethics Committee (Ref: 20214120-5868). Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

ZJ, SE, MH, and RHO contributed to the conceptualization and development of this research design. ZJ drafted the manuscript. All the listed authors reviewed and provided constructive feedback to all manuscript sections and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

ZJ was funded by a Swinburne University Postgraduate Research Award (SUPRA) (102943987). RHO was funded in part through an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Principal Research Fellowship (APP115125).

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the members of AMES Australia Tess Demediuk, Maria Tsopanis, Angelica Svensson and Melika Yassin Sheik-Eldin for their continued support and contribution in this study. Importantly, the authors gratefully acknowledge Nanthu Kunoo for her steadfast assistance in supporting the researchers to engage with the community leaders and members and for providing cultural and linguistic guidance and advice in all aspects of the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Dias S, Gama A, Cortes M, de Sousa B. Healthcare-seeking patterns among immigrants in Portugal. Health Soc Care Commun. (2011) 19:514–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2011.00996.x

2. Dias S, Gama A, Maia AC, Marques MJ, Campos Fernandes A, Goes AR, et al. Migrant communities at the center in co-design of health literacy-based innovative solutions for non-communicable diseases prevention and risk reduction: application of the optimising health literacy and access (ophelia) process. Front Public Health. (2021) 9:639405. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.639405

3. Dias S, Gama A, Rocha C. Immigrant women's perceptions and experiences of health care services: Insights from a focus group study. J Public Health. (2010) 18:489–96. doi: 10.1007/s10389-010-0326-x

4. Ahmadinia H, Eriksson-Backa K, Nikou S. Health-seeking behaviours of immigrants, asylum seekers and refugees in Europe: a systematic review of peer-reviewed articles. J Document. (2021) 78:18–41. doi: 10.1108/JD-10-2020-0168

5. Department of Health Human Services. Refugee and asylum seeker health and wellbeing State Government of Victoria, Australia. (2020). Available online at: https://www2.health.vic.gov.au/about/populations/refugee-asylum-seeker-health#:~:text=Victoria%20currently%20receives%20around%20one,settle%20in%20Victoria%20each%20year (accessed July 7, 2020).

6. Mårtensson L, Lytsy P, Westerling R, Wångdahl J. Experiences and needs concerning health related information for newly arrived refugees in Sweden. BMC Public Health. (2020) 20:1–1044. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09163-w

7. Bogic M, Njoku A, Priebe S. Long-term mental health of war-refugees: a systematic literature review. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. (2015) 15:1–41. doi: 10.1186/s12914-015-0064-9

8. Hahn K, Steinhäuser J, Goetz K. Equity in health care: A qualitative study with refugees, health care professionals, and administrators in one region in Germany. BioMed Res Int. (2020) 8:1–15. doi: 10.1155/2020/4647389

9. Lloyd A. Building information resilience: how do resettling refugees connect with health information in regional landscapes–implications for health literacy. Australian Acad Res Libraries. (2014) 45:48–66. doi: 10.1080/00048623.2014.884916

10. Russell G, Harris M, Cheng I-H, Kay M, Vasi S, Joshi C, Chan B, Lo W, Wahidi S, Advocat J. Coordinated primary health care for refugees: a best practice framework for Australia. (2013). Available online at: http://files.aphcri.anu.edu.au/reports/Grant%20RUSSELLFinal%20Report.pdf (accessed August 28, 2022).

11. Murray SB, Skull SA. Hurdles to health: immigrant and refugee health care in Australia. Australian Health Review. (2005) 29:25–9. doi: 10.1071/AH050025

12. Sheikh M, Nugus PI, Gao Z, Holdgate A, Short AE, Al Haboub A, et al. Equity and access: understanding emergency health service use by newly arrived refugees. Med J Australia. (2011) 195:74–6. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2011.tb03210.x

13. Simich L. Health Literacy Immigrant Populations. Public Health Agency of Canada Metropolis Canada, Ottawa, Canada. (2009). Available online at: http://www.metropolis.net/pdfs/health_literacy_policy_brief_jun15_e.pdf (accessed July 20, 2022).

14. Dowling A, Enticott J, Kunin M, Russell G. The association of migration experiences on the self-rated health status among adult humanitarian refugees to Australia: An analysis of a longitudinal cohort study. Int J Equity Health. (2019) 18:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12939-019-1033-z

15. George M, A. theoretical understanding of refugee trauma. Clin Soc Work J. (2010) 38:379–87. doi: 10.1007/s10615-009-0252-y

16. Kartal D, Alkemade N, Kiropoulos L. Trauma and mental health in resettled refugees: mediating effect of host language acquisition on posttraumatic stress disorder, depressive and anxiety symptoms. Transcult Psychiatry. (2019) 56:3–23. doi: 10.1177/1363461518789538

17. Sheikh-Mohammed M, MacIntyre CR, Wood NJ, Leask J, Isaacs D. Barriers to access to health care for newly resettled sub-Saharan refugees in Australia. Medical J Austr. (2006) 185:594–7. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00721.x

18. Sigvardsdotter E, Vaez M, Hedman A-M, Saboonchi F. Prevalence of torture and other war-related traumatic events in forced migrants: a systematic review. J Rehab Torture Victims Prev Torture. (2016) 26:41–73.

19. Masters PJ, Lanfranco PJ, Sneath E, Wade AJ, Huffam S, Pollard J, et al. Health issues of refugees attending an infectious disease refugee health clinic in a regional Australian hospital. Austr J Gen Practice. (2018) 47:305–10. doi: 10.31128/AFP-10-17-4355

20. Chaves NJ, Paxton GA, Biggs BA, Thambiran A, Gardiner J, Williams J, et al. The australasian society for infectious diseases and refugee health network of australia recommendations for health assessment for people from refugee-like backgrounds: an abridged outline. Med J Austr. (2017) 206:310–5. doi: 10.5694/mja16.00826

21. Chiarenza A, Dauvrin M, Chiesa V, Baatout S, Verrept H. Supporting access to healthcare for refugees and migrants in European countries under particular migratory pressure. BMC Health Serv Res. (2019) 19:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4353-1

22. World Health Organization (WHO). Report on the Health of Refugees and Migrants in the WHO European Region: No Public Health Without Refugee and Migrant Health. World Health Organization Regional Office. (2018). Available online at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/311347/9789289053846-eng.pdf (accessed September 20, 2022).

23. Matlin SA, Depoux A, Schütte S, Flahault A, Saso L. Migrants' and refugees' health: towards an agenda of solutions. Public Health Rev. (2018) 39:1–55. doi: 10.1186/s40985-018-0104-9

24. Greenhalgh T. Speaking of Medicine and Health: Less Research is Needed. PLOS BLOG. Available online at: https://speakingofmedicine.plos.org/2012/06/25/less-research-is-needed/ (accessed November 28, 2022).

25. Rikard R, Hall JK, Bullock K. Health literacy and cultural competence: a model for addressing diversity and unequal access to trauma-related health care. Traumatology. (2015) 21:227. doi: 10.1037/trm0000044

26. Osborne RH, Cheng CC, Nolte S, Elmer S, Besancon S, Budhathoki SS, et al. Health literacy measurement: embracing diversity in a strengths-based approach to promote health and equity, and avoid epistemic injustice. BMJ Global Health. (2022) 7:e009623. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2022-009623

27. Bonevski B, Randell M, Paul C, Chapman K, Twyman L, Bryant J, et al. Reaching the hard-to-reach: a systematic review of strategies for improving health and medical research with socially disadvantaged groups. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2014) 14:1–29. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-42

28. O'Reilly-de Brún M, de Brún T, Okonkwo E, Bonsenge-Bokanga J-S, Silva MMDA, Ogbebor F, et al. Using participatory learning and action research to access and engage with ‘hard to reach’migrants in primary healthcare research. BMC Health Serv Res. (2015) 16:1–16. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-1247-8

29. Batterham RW, Buchbinder R, Beauchamp A, Dodson S, Elsworth GR, Osborne RH. The optimising health literacy (ophelia) process: study protocol for using health literacy profiling and community engagement to create and implement health reform. BMC Public Health. (2014) 14:694. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-694

30. Osborne RH, Batterham RW, Elsworth GR, Hawkins M, Buchbinder R. The grounded psychometric development and initial validation of the health literacy questionnaire (HLQ). BMC Public Health. (2013) 13:658. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-658

31. Osborne RH, Elmer S, Hawkins M, Cheng CC, Batterham RW, Dias S, et al. Health literacy development is central to the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases. BMJ Global Health. (2022) 7:e010362. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2022-010362

32. Osborne RH, Elmer S, Hawkins M, Cheng C. The Ophelia Manual. The Optimising Health Literacy and Access (Ophelia) process to plan and implement National Health Literacy Demonstration Projects. Centre for Global Health and Equity, School of Health Sciences, Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne, Australia (2021).

33. Cheng C, Elsworth GR, Osborne RH. co-designing ehealth and equity solutions: application of the ophelia (optimizing health literacy and access) process. Front Public Health. (2020) 8: 604401. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.604401

34. Jordan JE, Buchbinder R, Osborne RH. Conceptualising health literacy from the patient perspective. Patient Educ Couns. (2010) 79:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.10.001

35. Bouclaous C, Haddad I, Alrazim A, Kolanjian H, El Safadi A. Health literacy levels and correlates among refugees in Mount Lebanon. Public Health. (2021) 199:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2021.08.006

36. Berkman ND, Davis TC, McCormack L. Health literacy: what is it? J Health Commun. (2010) 15:9–19. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.499985

37. Fernández-Gutiérrez M, Bas-Sarmiento P, Albar-Marín M, Paloma-Castro O, Romero-Sánchez J. Health literacy interventions for immigrant populations: a systematic review. Int Nurs Rev. (2018) 65:54–64. doi: 10.1111/inr.12373

38. Shohet L, Renaud L. Critical analysis on best practices in health literacy. Canadian J Pub Health. (2006):S10–13. doi: 10.1007/BF03405366

39. Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Crotty K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med. (2011) 155:97–107. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-2-201107190-00005

40. Williams ME, Thompson SC. The use of community-based interventions in reducing morbidity from the psychological impact of conflict-related trauma among refugee populations: a systematic review of the literature. J Immigrant Minority Health. (2011) 13:780–94. doi: 10.1007/s10903-010-9417-6

41. Fox S, Kramer E, Agrawal P, Aniyizhai A. Refugee and migrant health literacy interventions in high-income countries: a systematic review. J Immigrant Minority Health. (2021) 25:1–30. doi: 10.1007/s10903-021-01152-4

42. Wessels WK. The Refugee Experience: Involving Pre-Migration, in Transit, Post Migration Issues in Social Services. (2014). Available online at: https://sophia.stkate.edu/msw_papers/280 (accessed September 20, 2022).

43. Bhugra D, Jones P. Migration and mental illness. Adv Psychiatr Treatment. (2001) 7:216–22. doi: 10.1192/apt.7.3.216

44. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Resettlement: How We do Resettlement. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. (2022). Available online at: https://www.unhcr.org/en-au/resettlement.html (accessed December 12, 2022).

45. International Organization for Migration (IOM). International Migration Law: Glossary on Migration. International Organization for Migration. (2019). Available online at: https://publications.iom.int/books/international-migration-law-ndeg34-glossary-migration (accessed December 12, 2022).

46. World Health Organisation (WHO). Health Literacy Toolkit for Low and Middle-Income Countries: A Series of Information Sheets to Empower Communities and Strengthen Health Systems. WHO Regional Office for South-East Asia. (2015). Available online at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/205244 (accessed September 20, 2022).

47. Aaby A, Simonsen CB, Ryom K, Maindal HT. Improving organizational health literacy responsiveness in cardiac rehabilitation using a co-design methodology: results from the heart skills study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:1015. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17031015

48. Bakker MM, Putrik P, Aaby ASE, Debussche X, Morrissey J, Borge CR, et al. Acting together–WHO national health literacy demonstration projects (nhldps) address health literacy needs in the european region. Public Health Panorama. (2019) 5:233–43.

49. Kolarcik P, Belak A, Osborne RH. The Ophelia (OPtimise HEalth LIteracy and Access) Process. Using health literacy alongside grounded and participatory approaches to develop interventions in partnership with marginalised populations. Eur Health Psychologist. (2015) 17:297–304.

50. Stubbs T. Exploring the design and introduction of the ophelia (optimising health literacy and access) process in the philippines: a qualitative case study. Health Promotion J Austr. (2022) 33:829–37. doi: 10.1002/hpja.546

51. Anwar WA, Mostafa NS, Hakim SA, Sos DG, Cheng C, Osborne RH. Health literacy co-design in a low resource setting: harnessing local wisdom to inform interventions across fishing villages in egypt to improve health and equity. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:4518. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18094518

52. Bakker M, Putrik P, Rademakers J, Van de Laar M, Vonkeman H, Kok M, et al. OP0257-PARE using patient health literacy profiles to identify solutions to challenges faced in rheumatology care. Ann Rheum Dis. (2020) 79:162. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-eular.877

53. Bessarab D. Ng'Andu B. Yarning about yarning as a legitimate method in Indigenous research. Int J Criti Indig Studies. (2010) 3:37–50. doi: 10.5204/ijcis.v3i1.57

54. Rheault H, Coyer F, Bonner A. Chronic disease health literacy in first nations people: a mixed methods study. J Clin Nurs. (2021) 30:2683–95. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15757

55. O'Hara J, Hawkins M, Batterham R, Dodson S, Osborne RH, Beauchamp A. Conceptualisation and development of the conversational health literacy assessment tool (CHAT). BMC Health Serv Res. (2018) 18:199. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3037-6

56. Jensen NH, Aaby A, Ryom K, Maindal HT, A CHAT. about health literacy–a qualitative feasibility study of the conversational health literacy assessment tool (CHAT) in a danish municipal healthcare centre. Scand J Caring Sci. (2021) 35:1250–8. doi: 10.1111/scs.12943

57. Choi J, Kushner KE, Mill J, Lai DW. Understanding the language, the culture, and the experience: translation in cross-cultural research. Int J Q Methods. (2012) 11:652–65. doi: 10.1177/160940691201100508

58. Hawkins M, Cheng C, Elsworth GR, Osborne RH. Translation method is validity evidence for construct equivalence: analysis of secondary data routinely collected during translations of the health literacy questionnaire (HLQ). BMC Med Res Methodol. (2020) 20:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12874-020-00962-8

59. Wilkinson S. Focus group methodology: a review. Int J Soc Res Methodol. (1998) 1:181–203. doi: 10.1080/13645579.1998.10846874

60. Liamputtong P. Focus group methodology: introduction and history. Focus Group Methodol Principle Practice. (2011) 224:1–14. doi: 10.4135/9781473957657.n1

61. Funnell SC, Rogers PJ. Purposeful Program Theory: Effective Use of Theories of Change and Logic Models. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons (2011) 46–7 p.

62. Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL, Gutmann ML, Hanson WE. Advanced mixed methods research designs. Handb Mixed Methods Soc Behav Res. (2003) 209:209–40.

63. Edmondson AC, McManus SE. Methodological fit in management field research. Acad Manage Rev. (2007) 32:1246–64. doi: 10.5465/amr.2007.26586086

64. Creswell JW, Creswell JD. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. London: Sage Publications (2017), 160–90 p.

65. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Q Res Psychol. (2006) 3:77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

66. Gele AA, Pettersen KS, Torheim LE, Kumar B. Health literacy: the missing link in improving the health of Somali immigrant women in Oslo. BMC Public Health. (2016) 16:1134. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3790-6

67. Renzaho A, Polonsky M, Mellor D, Cyril S. Addressing migration-related social and health inequalities in Australia: call for research funding priorities to recognise the needs of migrant populations. Australian Health Review. (2016) 40:3–10. doi: 10.1071/AH14132

68. Svensson P, Carlzén K, Agardh A. Exposure to culturally sensitive sexual health information and impact on health literacy: a qualitative study among newly arrived refugee women in Sweden. Cult Health Sexuality. (2017) 19:752–66. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2016.1259503

69. Hawkins M, Massuger W, Cheng C, Batterham R, Moore GT, Knowles S, et al. Codesign and implementation of an equity-promoting national health literacy programme for people living with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): a protocol for the application of the Optimising Health Literacy and Access (Ophelia) process. BMJ Open. (2021) 11:e045059. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-045059

Keywords: health literacy development, co-design, former refugee community, Ophelia process, Conversational Health Literacy Assessment Tool (CHAT)

Citation: Jawahar Z, Elmer S, Hawkins M and Osborne RH (2023) Application of the optimizing health literacy and access (Ophelia) process in partnership with a refugee community in Australia: Study protocol. Front. Public Health 11:1112538. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1112538

Received: 30 November 2022; Accepted: 03 February 2023;

Published: 21 February 2023.

Edited by:

Ozden Gokdemir, Izmir University of Economics, TürkiyeReviewed by:

Tevfik Tanju Yilmazer, Ministry of Health, TürkiyeRiitta-Maija Hämäläinen, Wellbeing Services County of Päijät-Häme, Finland

Copyright © 2023 Jawahar, Elmer, Hawkins and Osborne. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zaman Jawahar,  emphd2FoYXJAc3dpbi5lZHUuYXU=

emphd2FoYXJAc3dpbi5lZHUuYXU=

Zaman Jawahar

Zaman Jawahar Shandell Elmer

Shandell Elmer Melanie Hawkins

Melanie Hawkins Richard H. Osborne

Richard H. Osborne