94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Public Health, 26 January 2023

Sec. Public Mental Health

Volume 11 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1095743

Hans Joachim Salize1*†

Hans Joachim Salize1*† Harald Dressing1†

Harald Dressing1† Heiner Fangerau2

Heiner Fangerau2 Pawel Gosek3

Pawel Gosek3 Janusz Heitzman3

Janusz Heitzman3 Inga Markiewicz3

Inga Markiewicz3 Andreas Meyer-Lindenberg1

Andreas Meyer-Lindenberg1 Thomas Stompe4,5

Thomas Stompe4,5 Johannes Wancata4

Johannes Wancata4 Marco Piccioni6,7

Marco Piccioni6,7 Giovanni de Girolamo8

Giovanni de Girolamo8Introduction: There is wide variation in the processes, structures and treatment models for dealing with mentally disordered offenders across the European Union. There is a serious lack of data on population levels of need, national service capacities, or treatment outcome. This prevents us from comparing the different management and treatment approaches internationally and from identifying models of good practice and indeed what represents financial efficiency, in a sector that is universally needed.

Methods: From March 2019 till January 2020 we surveyed forensic psychiatric experts from each European Union Member State on basic concepts, service capacities and indicators for the prevalence and incidence of various forensic psychiatric system components. Each expert completed a detailed questionnaire for their respective country using the best available data.

Results: Finally, 22 EU Member States and Switzerland participated in the survey. Due to the frequent lack of a clear definition of what represented a forensic psychiatric bed, exact numbers on bed availability across specialized forensic hospitals or wards, general psychiatric hospitals or prison medical wards were often unknown or could only be estimated in a number of countries. Population-based rates calculated from the survey data suggested a highly variable pattern of forensic psychiatric provision across Europe, ranging from 0.9 forensic psychiatric beds per 100,000 population in Italy to 23.3 in Belgium. Other key service characteristics were similarly heterogeneous.

Discussion: Our results show that systems for detaining and treating mentally disordered offenders are highly diverse across European Union Member States. Systems appear to have been designed and reformed with insufficient evidence. Service designers, managers and health care planners in this field lack the most basic of information to describe their systems and analyse their outcomes. As a basic, minimum standardized national reporting systems must be implemented to inform regular EU wide forensic psychiatry reports as a prerequisite to allow the evaluation and comparison of the various systems to identify models of best practice, effectiveness and efficiency.

The most appropriate location and treatment of people who commit offenses as a result of or while suffering from a mental disorder is an important consideration for societies and nations globally. A key challenge is to ethically implement basic principles such as that is only offenders who are responsible for their actions should be punished. Mentally disordered offenders who remain dangerous should be taken into some form of custody and treated to reduce the risk of further offending.

Internationally, a wide variety of judicial, medical and organizational approaches have evolved for this. Institutions and services where mentally ill offenders are detained and treated usually are labeled as “forensic psychiatry.” The wide-spread usage of this term suggests an international consensus regarding standards and processes for dealing with mentally disordered offenders. However, that is not the case. Guidelines for managing and treating forensic populations are scarce and typically quite general. Models of good practice are not agreed (1–4). Thus, this common label tends to conceal huge differences of the structure, size, organization and budgets of national forensic psychiatric systems.

Solid data, international evidence or essential knowledge from this sector is lacking, however. There are only a few studies on these issues available from the past, that covered only a small number of selected countries (5–9). These studies more or less used similar methods for assessing bed-rates or other data as applied in this study here, either by expert rating or by referring to administrative data, which usually turned out to be scarcely available, incomplete or of limited validity and reliability. The results suggest a wide variety in basic indicators, concepts and models.

This situation increases the risk that changes to the services for mentally disordered offenders are not triggered by clinical or legal needs but by largely extraneous economic or political considerations. Italy provides the most recent example in this when it recently closed its six established forensic psychiatric hospitals and replaced them with small community residential facilities (10, 11). However, this fundamental change had no international examples to guide them. The reorganization was not based on research if the new approach would lead to better treatment outcomes, more or fewer restrictions or how they would harm patient or public safety (12).

Initiatives as the EU-funded COST-Action IS1302 “Toward an EU research framework on Forensic Psychiatric care” launched in 2013 (9) or the so-called Ghent group (13), that try to intensify European research activities have criticized together with other experts in the field the lack of research evidence to inform the planning and design of forensic psychiatric services (4, 6, 14–16).

Research in this field faces considerable methodological challenges given that there is no clear consensus even on what a “forensic psychiatric bed” is or whether such beds should be in specialized forensic psychiatric hospitals, medical wards in prisons or in general psychiatric settings.

In order to address some of these problems, an EU-wide survey of the concepts and capacities for placing and treating mentally disordered offenders was conducted between 2018 and 2020 (with March 2019 as a starting point for the actual data collection). The survey was a part of the multi-center “European Study on Risk Factors for Violence in Mental Disorder and Forensic Care (EU-VIORMED)” (17).

The survey was designed and managed from the Central Institute of Mental Health in Mannheim, Germany. It aimed to collect data from national forensic psychiatric experts in all European Union Member States. These experts were supposed to fill in a semi-structured questionnaire, adapted from the survey instrument used in a similar EU-study between 2003 and 2005 (6, 18). The questionnaire included 52 questions across 9 sections that covered: forensic psychiatry legislation, key concepts, forensic psychiatry assessment, court and trial procedures, placement and treatment procedures, re-assessment and discharge, patients' rights, service provision and epidemiology (indicators of prevalence and incidence of forensic psychiatric patients, mean length of stay etc.). All indicators and items of the questionnaire were defined and standardized as precisely as possible to prevent methodological uncertainty and assure comparability between nations and systems. The questionnaire asked for the most recent data available for all items. For more detailed information see the original questionnaire in the supplement material of this paper.

A list of potential collaborators and experts from every EU Member States was compiled initially. These were contacted and invited to collaborate from July 2018 onwards. After agreement, the experts were subcontracted to the study and received a small allowance. All collaborators were proven experts in the field of forensic psychiatry in their country, most of them being long-term members of the COST-Action IS 1302 or the Ghent Group (see above) or being otherwise involved into international research or having administrative responsibilities for forensic psychiatric issues of their country. The questionnaires (always in English and not translated into the local languages of the respective countries) were distributed by e-mail with an initial deadline for return (by mail) by April 2019. Apart from specifications and definitions of items in the questionnaire, the experts did not receive training to complete the survey. After extending the deadline in some cases the last questionnaire was returned in January 2020, after which the survey was declared as closed. Although being invited and included into the original sample, experts from Greece, Hungary, Lithuania, Malta, the Netherlands and Slovakia did not reply or return the questionnaire even after deadline extension. Thus, the final sample included experts from 22 countries and Switzerland, a non-EU Member State. From the UK, England was represented. This paper presents the principle survey results regarding indicators for forensic psychiatric service provision (e.g., number of beds, prevalence etc.).

According to the major aim of the survey, data analysis methods were mostly descriptive. Due to incompleteness and limited validity or reliability of data or concepts, statistical power was not given and statistical tests were not applied, particularly not in the few cases where time series were reported.

Due to uncertainty and heterogeneity of concepts internationally in use we defined indicators as shown in Table 1. If survey data was associated to external data or indicators, official data sources were used, such as EUROSTAT (e.g., population figures for the respective countries and years). Basically, national level data was asked for and included into the comparison. A few cases of regional instead of nationwide coverage are marked.

The basic legal framework governing forensic psychiatric issues between primarily health or criminal laws might give some indication of how each nation considers the detention and treatment of mentally disordered offenders. It exemplifies whether this issue is seen primarily as a matter of clinical need or public safety. According to the information provided, England and Finland regulate the placement and treatment of mentally disordered offenders by their mental or public health acts. In Austria, Belgium, Latvia, Poland, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain and Switzerland the judicial framework is predominately governed through the national criminal laws. In other countries, such as Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Romania and Sweden the regulations are spread across penal/criminal laws and mental health or public health acts. In federally organized countries such as Germany, the legal frameworks vary regionally and so cannot be characterized nationally. The majority of European laws and regulations cover the full range of ICD or DSM mental disorders. However, the laws often fail to specify diagnostic categories, prognostic criteria or definitions of disorders that are included, leaving it open to judicial practice to include all mental disorders.

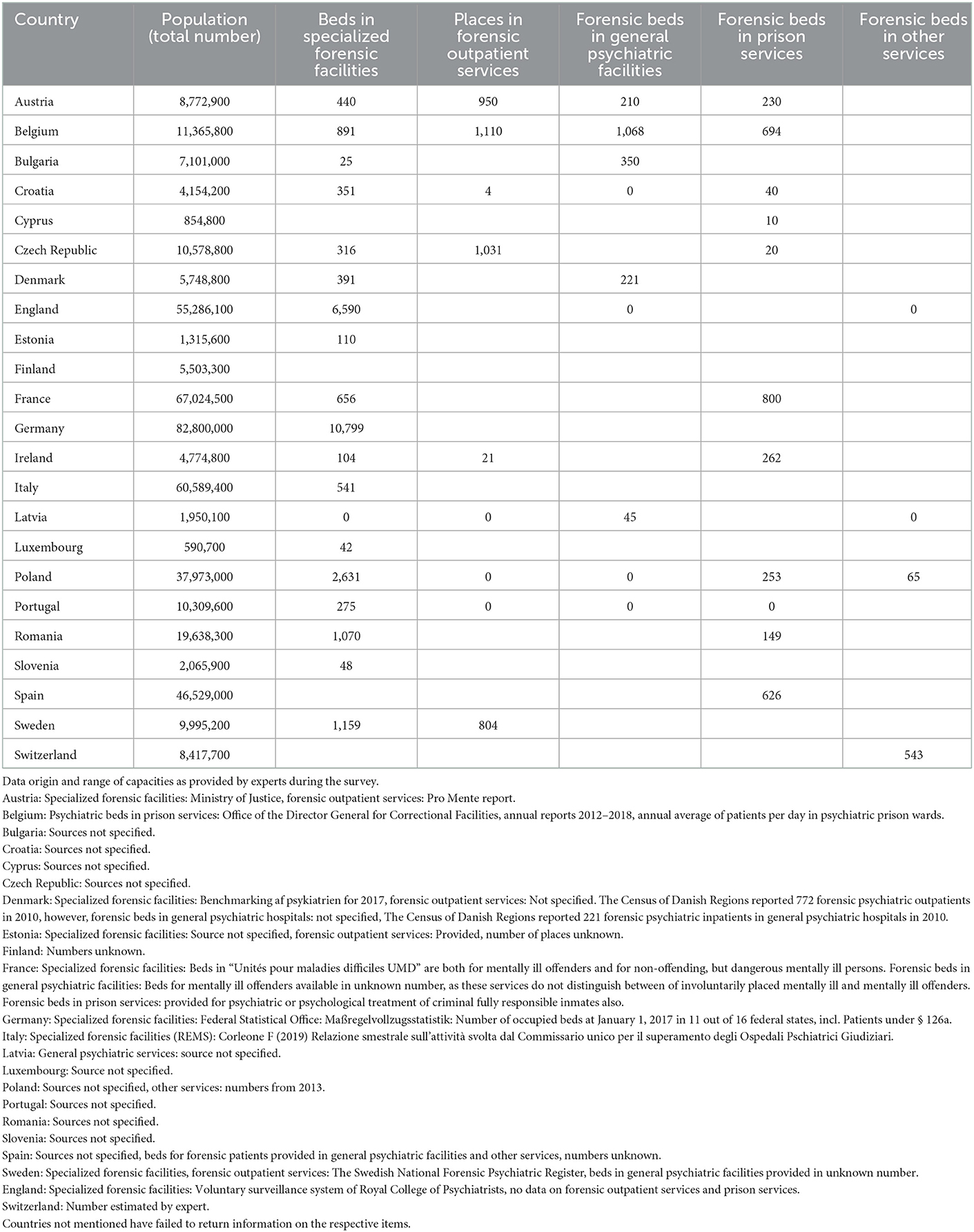

Generally, mentally disordered offenders may be detained and treated in a wide variety of service types and facilities in both health and penal settings. These include specialized forensic in- and outpatient services, general psychiatric hospitals and medical prison wards. Table 2 shows the estimated number of forensic psychiatric beds or places provided across the European Union in 2017 as reported during the survey.

Table 2. Number of defined forensic psychiatric beds in European Union Member States in 2017 (empty cells: no answer or unknown).

The numbers reported were based on the concept of a “psychiatric bed or place” that had some “official” assignation or arrangement as being officially regarded as a forensic psychiatric bed or place. Despite that superficially more or less clear concept, a considerable proportion of the capacities either had to be estimated or were even totally unknown to a proportion of experts. No answers in the questionnaire for the respective services or items were left open in the boxes of Table 2. The footnotes of Table 2 show the data origins and areal ranges of figures if such information was provided.

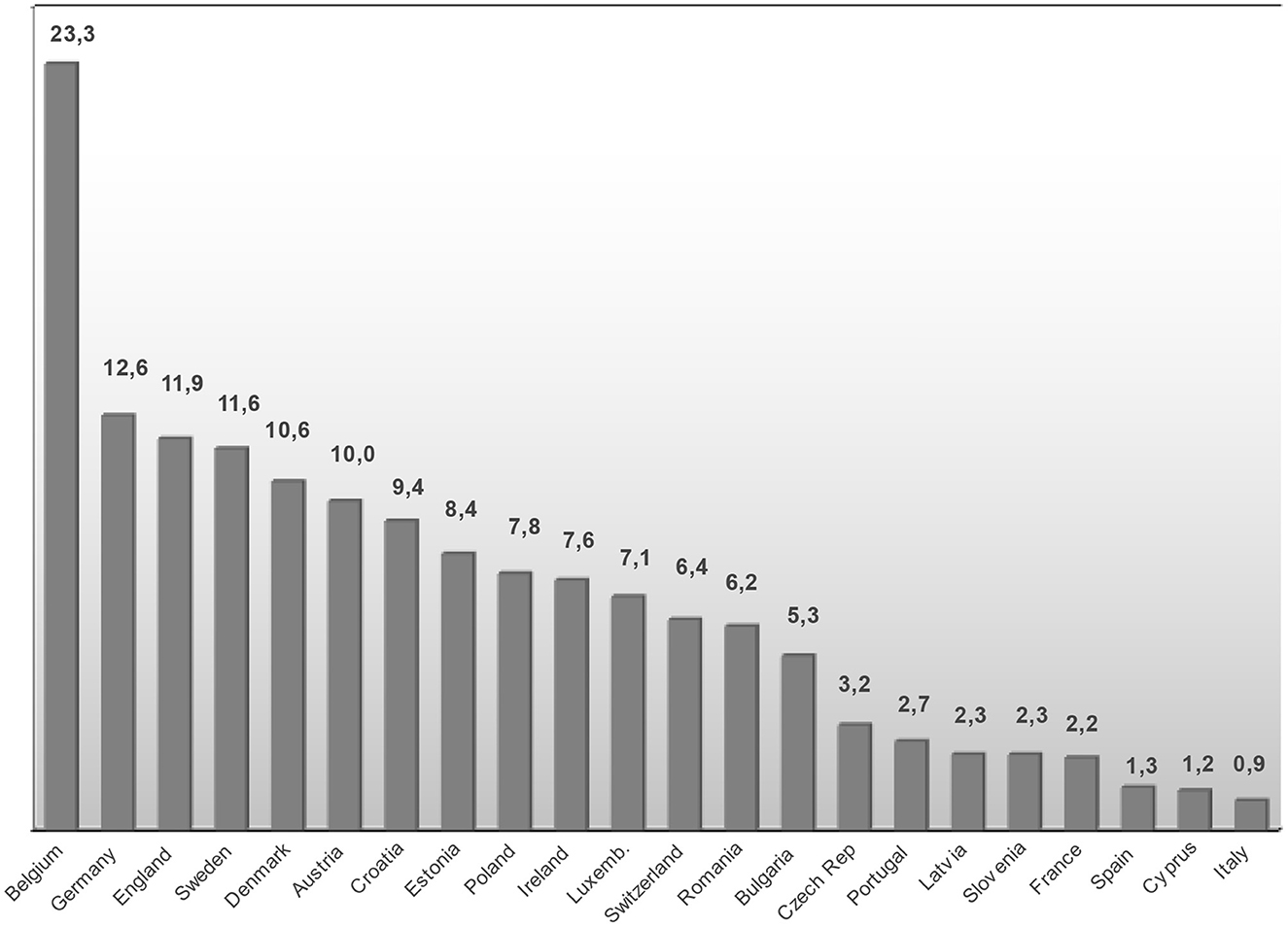

Despite these uncertainties, we summarized the number of forensic psychiatric beds in specialized forensic facilities, forensic psychiatric beds in general psychiatric facilities and forensic psychiatric beds in prison ward facilities and in other services to calculate the overall forensic psychiatric bed rates for every nation involved (columns 2–5 of Table 2). The population figures for the respective years were from Eurostat (19). Results are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Forensic psychiatric beds per 100,000 population in European Union Member States in 2017 (forensic psychiatric beds in specialized forensic facilities, in general psychiatric facilities, in medical prison wards and in other services, excluding forensic psychiatric outpatient treatment capacities). Countries not mentioned have failed to return information on the respective items.

Even when taking into account the heterogeneity of this data, population-based rates reveal a highly variable pattern or service provision across Europe, ranging from 0.9 forensic psychiatric beds per 100,000 population in the reorganized forensic psychiatric service in Italy up to 23.3 in Belgium. Of all participating countries, Belgium provides the largest amount of forensic psychiatric beds that are located in general psychiatric hospitals (n= 1,068). Even when those beds were removed from the calculation, Belgium still had the largest per capita service among the included countries with 14.0 forensic psychiatric beds per 100,000 population.

There was almost no data on the national mean length of stay in forensic psychiatric services, although this information is essential for evaluating the effectiveness or outcome of the forensic psychiatric sector. When provided, mean length of stay data usually covered only selected services, and completely excluded patients in general psychiatric and prison service placements and thus were not reported here.

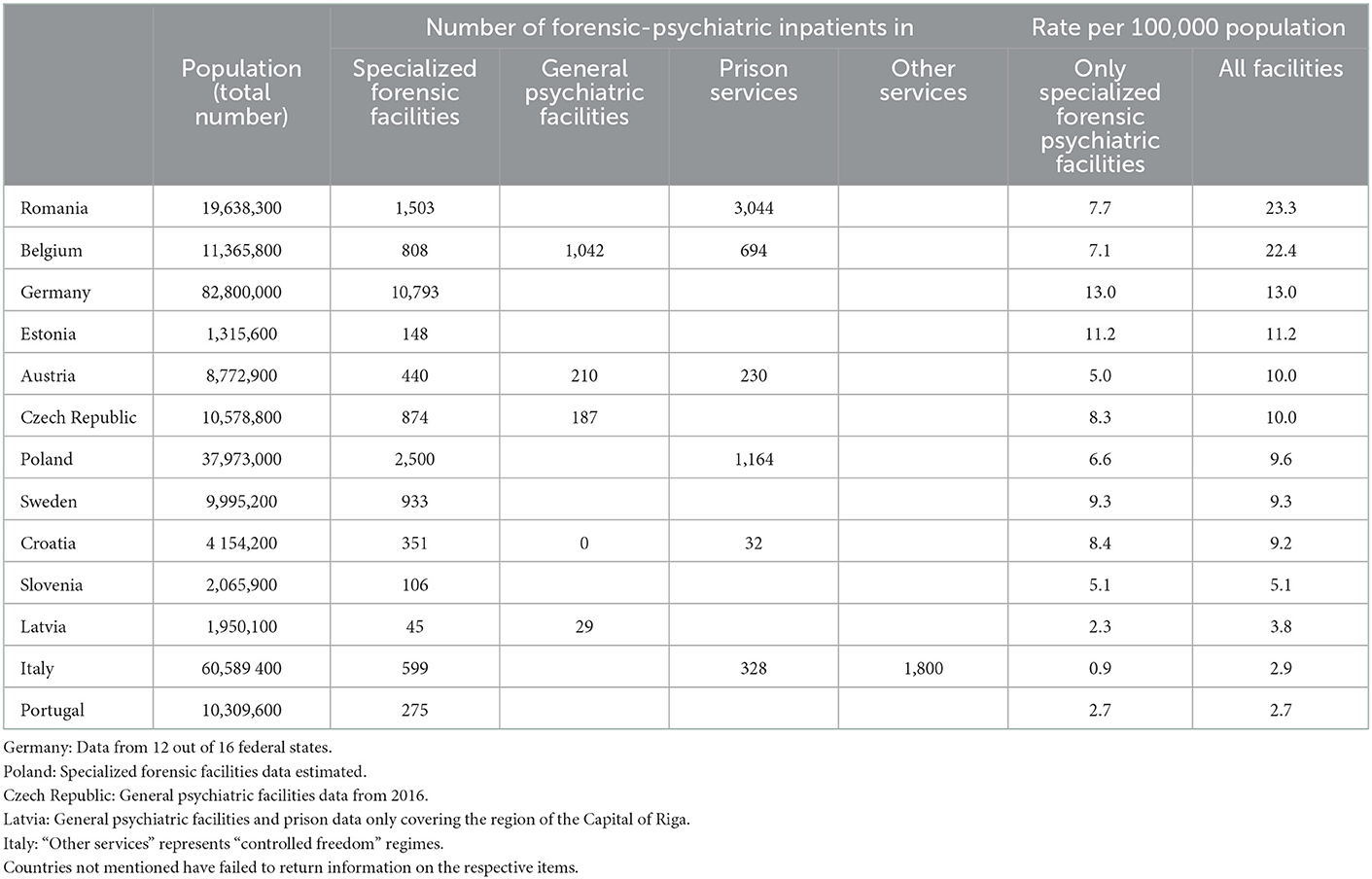

The numbers of patients actually detained or treated in the available forensic beds were reported only from 13 out of the 22 participating countries. We used these figures as an estimate for the treated prevalence of forensic patients. Due to the greater uncertainty around the data on forensic psychiatric patients in general psychiatric hospitals and prison services, we calculated two prevalence rates, one for all facilities for which data was available and another covering only specialized forensic psychiatric facilities in 2017 (see Table 3).

Table 3. Estimates of treated prevalence of mentally ill offenders per 100,000 population in European Union Member States in 2017 (only forensic psychiatric inpatients, excluding forensic psychiatric patients in forensic psychiatric outpatient or other outpatient services; empty cells: unknown).

Considering all services that could detain or treat a mentally disordered offender, prevalence rates ranged from 2.7 per 100,000 population in Portugal up to 23.3 per 100,000 population in Romania. Looking only at specialized forensic psychiatric facilities, the lowest rate was 0.9 per 100,000 population in Italy and the highest was 13.0 per 100,000 population in Germany. However, this still underestimated the real prevalence in Germany, due to the lack of available data from 25 % of German Federal States.

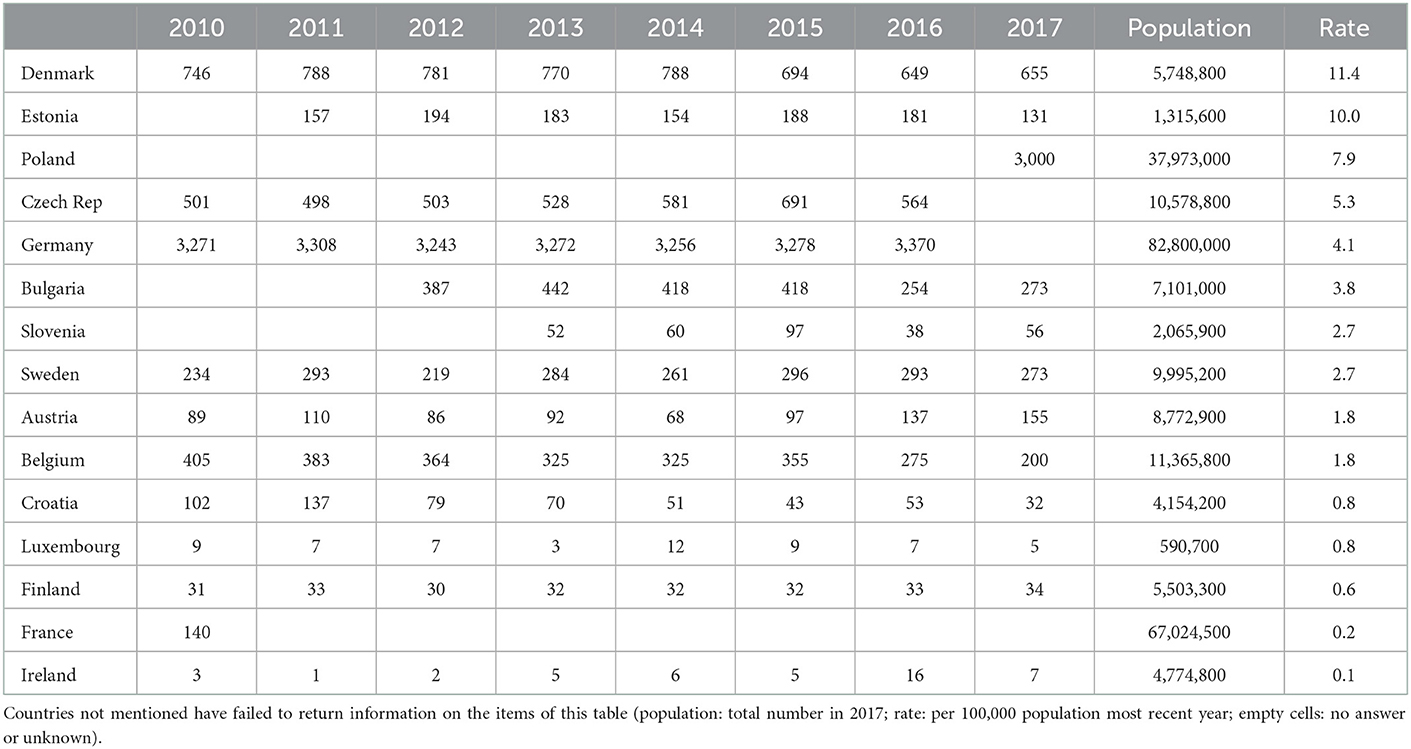

As accurate information on admissions and discharges to the various services was even rarer, we considered the annual numbers of defendants found not being guilty by reason of insanity as an estimate for the incidence of mentally ill offenders. That data was usually provided by the Ministries of Justice and more readily available. Table 4 shows the time series of these verdicts from 2010 onwards and the incidence rate per 100,000 population calculated for the most recent year available from 15 countries.

Table 4. Annual number of verdicts on persons not guilty for reason of insanity from 2010 to 2017 as an estimate for the incidence of mentally ill offenders in European Union Member States.

Again, the data suggest a wide variation in the annual incidence across Europe. Time series data indicate uneven trends of higher (e.g., Austria), lower (e.g., Belgium, Croatia, Bulgaria) or more or less stable incidence rates (e.g., Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Sweden) during the covered 8 year-period. Lowest estimates were 0.1 per 100,000 population in 2017 against 11.4 per 100,000 population as the highest rate in Denmark in 2017.

There is a serious gap in our knowledge about the basic characteristics and features of forensic psychiatric systems in European Union Member States. The common usage of the umbrella term “forensic psychiatry” tends to cover various understandings and practices. In many countries, even leading national experts or forensic psychiatrists in the field are unable to easily report valid basic numbers of the most essential indicators such as the number of forensic psychiatric beds, the incidence and prevalence of mentally disordered offenders or the mean length of stay in forensic psychiatric services. Outdated data or incomplete or time series (as in Table 4 in the case of France or Poland) suggest weak reporting standards regarding these issues in the health or judicial administration of these and other countries. Exact information on capacities of forensic outpatient services, forensic beds in general psychiatric hospitals and psychiatric beds in prison wards were particularly incomplete, or completely unknown even when it was reported that such services were in principle available.

From the perspective of validity and reliability, the inclusion of experts with varying background providing data from heterogenous non-standardized and in some cases not clearly defined sources is a serious methodological limitation. However, the current situation in European forensic psychiatry does not allow a better standardized data collection approach without risking to come up with even larger data gaps.

A considerable amount of informal, provisional, temporary or otherwise unregistered forensic beds in general psychiatric hospitals, outpatient services or medical prison wards cannot be ruled out in several countries. Crucial national outcome data, such as the rate of re-offending is totally lacking. These findings and conclusion are in line with the most recent study on the issue of Tomlin and colleagues who applied a similar approach and were confronted with similar obstacles (9).

The finding that national reporting systems on this crucial issue still seem to be grossly underdeveloped and that European registers are still missing is even more striking considering the repeated criticism of this failing by experts over the last decades.

Despite the poor data-base it is evident that approaches and models of detaining and treating mentally disordered offenders are highly diverse across European Union Member States. The poorly standardized estimates presented here can only really be compared with an appreciation of the various legal and service provision frameworks that shape the national models (6, 20). However, we did not find any system characteristic or indicator from the questionnaire that would explain or justify a phenomenon as e.g., the much higher rate of forensic psychiatric capacities in Belgium. This great diversity of approaches prohibits a meaningful comparison of national forensic psychiatric systems merely on the basis of bed-rates or treated prevalence and makes it very difficult to draw any firm conclusions about the effectiveness of forensic psychiatric service models in Europe and worldwide.

The lack of clear data must be seen as a serious omission in a sector that is essential both for national psychiatric systems and for societies in general. Judicial frameworks that are overcome or incomplete or care concepts that are ineffective cannot be identified from the current scarce evidence. It also contributes to the fact that current forensic psychiatric treatment guidelines are rather general in nature (3).

This situation put European forensic psychiatry far behind the standards of related disciplines. Community psychiatry for instance has developed, discussed and agreed upon common concepts and guidelines and applies these in the improvement of national systems across Europe (21). The situation is inappropriate for a sector whose condition can be seen as a touchstone for a fair judicial framework, the high quality of mental health care provision and the overall level of humanity of any society. It seems absolutely essential to develop a strategy that would encompass over-arching concepts, harmonized regulations and practice guidelines for moving the field in that direction in future. To internationally agree on a common set of basic standardized indicators that are flexible enough for easy application across the various international forensic psychiatric systems is overdue. Mandatory national reporting systems need to be implemented.

This is first and foremost not a methodological challenge, but rather a political task to be tackled immediately. It is the task of the scientific community to combine their efforts by providing a binding methodological and research framework and increase pressure on national policy makers to implement it.

The data analyzed in this study is subject to the following licenses/restrictions: confidential. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to not applicable.

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

The EUropean Study on VIOlence Risk and MEntal Disorders (EU-VIORMED) project has received a grant from European Commision (Grant Number PP-2- 3-2016, November 2017–October 2020) and is registered on the Research Registry - https://www.researchregistry.com/ - Unique Identifying Number 4604. In Italy this study has also been supported by 5 × 1000 2017 funds and Ricerca Corrente funds from the Italian Ministry of Health. The funding source had no role in the design and in the conduct of the study, and had no role in data analyses, in the interpretation of results and in the writing.

Additionally to the co-authors of this paper, we acknowledge the contribution for this study from the following experts (among others), who provided questionnaires with data on the forensic psychiatric care system in their country: Thierry Pham (Belgium), Vladimir Nakov (Bulgaria), Dragica Kozarić-Kovačić, Zrnka Kovačić Petrović (Croatia), Kostas Fantis (Cyprus), Jirí Raboch (Czech Republic), Lisbeth Uhrskov (Denmark), Madis Parksepp (Estonia), Thomas Fovet, FlorenceThibaut (France), Andrea Giersiefen, Barbara Horten, Julia Schmidt (Germany), Harry Kennedy (Ireland), Luca Castelletti, Laura Iozzino, Franco Scarpa (Italy), Niamh Catherine Power (Luxembourg), Nicoleta Tataru, Gabriela Costea (Romania), Miguel Xavier (Portugal), Miran Pustoslemsek (Slovenia), and Vicenç Tort-Herrando (Spain).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Priebe S. Institutionalization revisited - with and without walls. Acta Psychiatr Scand. (2004) 110:81–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0047.2004.00386.x

2. Salize HJ, Lepping P, Dressing H. How harmonised are we? Forensic mental health legislation and service provision in the European Union Crim. Behav Ment Health. (2005) 15:143–7. doi: 10.1002/cbm.6

3. Völlm BA, Clarke M, Herrando VT, Seppänen AO, Gosek P, Heitzman J, et al. European Psychiatric Association (EPA) guidance on forensic psychiatry: Evidence based assessment and treatment of mentally disordered offenders. Eur Psychiatry. (2018) 9 51:58–73. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.12.007

4. Goethals C. Forensic Psychiatry and Psychology in Europe. A Cross-border Study Guide. Cham: Springer International Publishing. (2018).

5. Blaauw E, Hoeve M, van Marle H, Sheridan L. Mentally disordered offenders. International Perspective on Assessment and Treatment. The Hague: Elsevier. (2002).

6. Salize HJ, Dressing H. Placement and Treatment of Mentally Ill Offenders - Legislation and Practice in EU Member States. Lengerich, Berlin, Bremen, Miami, Riga, Viernheim, Wien, Zagreb: Pabst Scientific Publishers. (2005).

7. Chow WS, Priebe S. How has the extent of institutional mental healthcare changed in Western Europe? Analysis of data since 1990. BMJ Open. (2016) 6:e010188. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010188

8. Connell C, Seppänen A, Scarpa F, Gosek P, Heitzman J, Furtado V. External factors influencing length of stay in forensic services - a European evaluation. Psychiatr Pol. (2019) 53:673–89. doi: 10.12740/PP/99299

9. Tomlin J, Lega I, Braun P, Kennedy HG, Herrando VT, Barroso R, et al. Forensic mental health in Europe: some key figures. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2021) 56:109–17. doi: 10.1007/s00127-020-01909-6

10. Di Lorito C, Castelletti L, Lega I, Gualco B, Scarpa F, Völlm B. The closing of forensic psychiatric hospitals in Italy: determinants, current status and future perspectives. A scoping review. Int J Law Psychiatry. (2017) 55:54–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2017.10.004

11. Ferracuti S, Pucci D, Trobia F, Alessi MC, Rapinesi C, Kotzalidis GD, et al. Evolution of forensic psychiatry in Italy over the past 40 years (1978-2018). Int J Law Psychiatry. (2019) 62:45–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2018.10.003

12. Vorstenbosch E, Castelletti L. Exploring needs and quality of life of forensic psychiatric inpatients in the reformed Italian system, implications for care and safety. Front Psychiatry. (2020) 11:258. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00258

13. Nedopil N, Taylor P, Gunn J. Forensic psychiatry in Europe: the perspective of the Ghent Group. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. (2015) 19:80–3. doi: 10.3109/13651501.2014.967700

14. Müller-Isberner R, Hodgins S. “Evidence-based treatment of mentally disordered offenders”. In: Hodgins S, Müller-Isberner R, editors. Violence, crime and mentally disordered offenders. Chichester: Wiley. (2000).

15. Dressing H, Salize HJ. Forensic psychiatric assessment in European Union Member States. Acta Psychiatr Scand. (2006) 114:282–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00771.x

16. Arboleda-Florez J. Forensic psychiatry: contemporary scope, challenges and controversies. World Psychiatry. (2006) 5:87–91.

17. De Girolamo G, Carrà G, Fangerau H, Ferrari C, Gosek P, Heitzman J, et al. European violence risk and mental disorders (EU-VIORMED): a multi-centre prospective cohort study protocol. BMC Psychiatry. (2019) 19:410. doi: 10.1186/s12888-019-2379-x

18. Salize HJ, Dressing H. Admission of mentally disordered offenders to specialized forensic care in fifteen European Union Member States. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2007) 42:336–42. doi: 10.1007/s00127-007-0159-2

20. Fovet T, Thibaut F, Parsons A, Salize H, Thomas P, Lancelev C. Mental health and the criminal justice system in France: a narrative review. Forensic Sci Int. (2020) 1:100028. doi: 10.1016/j.fsiml.2020.100028

Keywords: forensic psychiatric care, mentally ill offenders, forensic psychiatric prevalence, forensic psychiatric incidence, mental health policies

Citation: Salize HJ, Dressing H, Fangerau H, Gosek P, Heitzman J, Markiewicz I, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Stompe T, Wancata J, Piccioni M and de Girolamo G (2023) Highly varying concepts and capacities of forensic mental health services across the European Union. Front. Public Health 11:1095743. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1095743

Received: 11 November 2022; Accepted: 06 January 2023;

Published: 26 January 2023.

Edited by:

Wulf Rössler, Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin, GermanyReviewed by:

Yi Huang, Lingnan University, ChinaCopyright © 2023 Salize, Dressing, Fangerau, Gosek, Heitzman, Markiewicz, Meyer-Lindenberg, Stompe, Wancata, Piccioni and de Girolamo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hans Joachim Salize,  aGFucy1qb2FjaGltLnNhbGl6ZUB6aS1tYW5uaGVpbS5kZQ==

aGFucy1qb2FjaGltLnNhbGl6ZUB6aS1tYW5uaGVpbS5kZQ==

†These authors share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.