94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Public Health, 30 January 2023

Sec. Public Mental Health

Volume 11 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1081706

Zhaoping Wu1

Zhaoping Wu1 Qiang Yue2

Qiang Yue2 Zhen Zhao1

Zhen Zhao1 Jun Wen2

Jun Wen2 Lanying Tang1

Lanying Tang1 Zhenzhen Zhong2

Zhenzhen Zhong2 Jiahui Yang1

Jiahui Yang1 Yingpu Yuan3

Yingpu Yuan3 Xiaobo Zhang2*

Xiaobo Zhang2*Background: The relationship between smoking and depression remains controversial. This study aimed to investigate the association between smoking and depression from three aspects: smoking status, smoking volume, and smoking cessation.

Methods: Data from adults aged ≥20 who participated in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) between 2005 and 2018 were collected. The study gathered information about the participants' smoking status (never smokers, previous smokers, occasional smokers, daily smokers), smoking quantity per day, and smoking cessation. Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), with a score ≥10 indicating the presence of clinically relevant symptoms. Multivariable logistic regression was conducted to evaluate the association of smoking status, daily smoking volume, and smoking cessation duration with depression.

Results: Previous smokers [odds ratio (OR) = 1.25, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.05–1.48] and occasional smokers (OR = 1.84, 95% CI: 1.39–2.45) were associated with a higher risk of depression compared with never smokers. Daily smokers had the highest risk of depression (OR = 2.37, 95% CI: 2.05–2.75). In addition, a tendency toward a positive correlation was observed between daily smoking volume and depression (OR = 1.65, 95% CI: 1.24–2.19) (P for trend <0.05). Furthermore, the longer the smoking cessation duration, the lower the risk of depression (OR = 0.55, 95% CI: 0.39–0.79) (P for trend <0.05).

Conclusions: Smoking is a behavior that increases the risk of depression. The higher the smoking frequency and smoking volume, the higher the risk of depression, whereas smoking cessation is associated with decreased risk of depression, and the longer the smoking cessation duration, the lower the risk of depression.

Depression has become a major and serious public health challenge worldwide and has been recognized as one of the leading causes of disability and mortality around the globe (1–3). In the United States, the prevalence of major depressive disorders in women is as high as 21% and is more than 10% in men (4, 5). Thus, there is an urgent need to investigate the influencing and mitigating factors of depression in the US population. Despite growing evidence that smoking may be a risk factor for psychological problems, there has been controversy about the relationship between smoking and depression (6). A Mendelian randomization study of 462,690 participants from the UK Biobank showed that smoking was associated with an increased risk of depression and even schizophrenia in both lifelong and beginning smokers (1). In contrast, a systematic review of mental health professionals' attitudes toward smoking and smoking cessation in people with mental illness, including 38 small studies with 16,369 participants, found that smoking mitigated some psychological health problems, including depression, anxiety, and stress (7). Furthermore, some researchers did not find any association between persistent smoking and an increased risk of depression after controlling for confounding factors such as family or genetic susceptibility (8). Given these contradictions, a more in-depth study of the relationship between smoking and depression is necessary.

The change in depressive symptoms after smoking cessation is another aspect reflecting the relationship between smoking and depression, which too has attracted controversy. Unlike their counterparts in other countries, mental health professionals in the US do not consider the adverse effects of smoking cessation (7). Research has shown that smoking cessation could improve mental health (9), even in people with mental illness (6, 10), and found that continued smoking cessation over 10 years was associated with a lower risk of major depression (4). In contrast, some studies report that smoking reduces stress and relieves anxiety, and quitting smoking can lead to the aggravation of mental symptoms (11). Inconsistent findings on the relationship between smoking cessation and depressive symptoms highlight the need for continued research to explore this issue.

This study aimed to examine the association between smoking and depressive symptoms in a large, nationally representative sample of US adults across multiple dimensions by adjusting for various potential confounders. Specifically, we focused on analyzing the association between smoking and depression from three aspects: smoking status, smoking volume, and smoking cessation.

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) is a nationally representative, complex, stratified, multistage, cross-sectional survey to investigate the risk factors associated with health and nutrition among the US population. Since 1999, NHANES has been conducted biennially, and each survey round includes different participants. The assessment is carried out by means of home interviews and mobile medical examination centers (12). The National Center for Health Statistics Research Ethics Review Board approves the survey, and all participants provide written informed consent. Our study used data from seven rounds of NHANES between 2005 and 2018. This period was focused on because the NHANES started using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) score to assess depression in 2005, and the COVID-19 pandemic had not yet hit the world in 2018. Samples with incomplete questionnaire information in the seven survey rounds were excluded from this study. Considering that the sampling age of most participants was greater than or equal to 20, we chose people aged ≥20 as the research subjects. Figure 1 summarizes the inclusion and exclusion criteria for each aspect of the study.

Based on the answer to the question “Have you smoked at least 100 cigarettes in life,” we defined the participants who answered “no” as “never smokers.” Those who answered “yes” were further divided into three groups according to the answer to the question “Do you now smoke cigarettes?”: “previous smokers,” “occasional smokers,” and “daily smokers.” The question “On average, how many cigarettes have you smoked per day during the past 30 days?” examined smoking volume. The average number of cigarettes smoked per day by an individual was coded as the smoking volume; the individuals who responded with “1 cigarette or less per day” were coded as 1, and those who answered “95 cigarettes or more per day” were coded as 95. The above data were treated as a continuous variable analysis. The participants were divided into quartile groups according to the smoking volume from low to high: <5 cigarettes per day (Q1), 5–9 cigarettes per day (Q2), 10–19 cigarettes per day (Q3), and more than 20 cigarettes per day (Q4).

The question “How long has it been since you quit smoking cigarettes” obtained data on smoking cessation. Smoking cessation was computed in years. Smoking cessation duration was considered “0” (Q0) when participants responded to “Do you now smoke cigarettes” with “occasionally” or “daily.” The participants were divided into quartile groups according to the duration of smoking cessation from low to high: <5 years (Q1), 5–15 years (Q2), 15–29 years (Q3), and more than 29 years (Q4).

Potential confounders for depression were selected based on previous studies, such as gender, age, race, education level, marital status, family poverty income ratio (PIR), body mass index (BMI), diabetes, failing kidneys, heart failure, coronary heart disease, emphysema, chronic bronchitis, and cancer or malignancy (13). Race was self-reported, and participants were categorized into Mexican American, non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic white, Hispanic, and other races. Marital status was categorized into married, living with a partner, divorced, widowed or separated, and never married. Education level was divided into several subgroups (college graduates or above, associate (AA) degree, high school graduates, and below grade 11) based on the “Education level—Adults 20+” questionnaire. Family PIR was expressed as median household income divided by the poverty threshold (14). Diabetes status in adults was coded as yes, no, or borderline.

All statistical analyses were performed using R software version 4.2.0 and the nhanesR package, a survey analysis procedure that accounts for sample weights, stratification, and clustering of complex sampling designs to ensure nationally representative estimates. Continuous variables in baseline data were presented as weighted means and standard errors; categorical variables were presented as weighted percentages and frequencies. Differences between continuous variables were assessed using the analysis of variance (ANOVA) test or the Kruskal–Wallis test, depending on the distribution. Differences between categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-square test. Three logistic regression models were developed to express the association of smoking status, smoking volume, and smoking cessation with depression. In Model I, no adjustment was made for confounders. In Model II, age, gender, BMI, and race were adjusted based on Model I. In Model III, adjustments were made for education level, marital status, family PIR, diabetes, failing kidneys, heart failure, coronary heart disease, emphysema, chronic bronchitis, and cancer or malignancy based on Model II. Two-sided values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

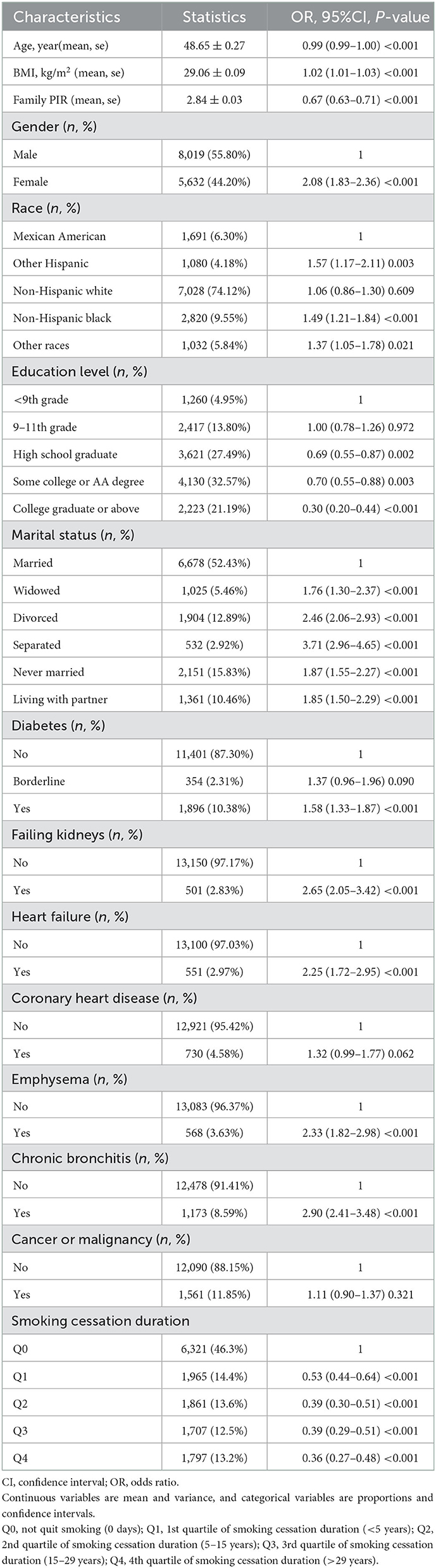

A total of 116,876 US residents participated in seven survey rounds between 2008 and 2015. Of these, 43,190 participants provided complete data on smoking status and depressive symptoms; 12,666 participants were excluded due to missing covariate data. A total of 30,524 participants were included for the final analysis of the association between smoking status and depressive symptoms. Their mean age was 47.17 ± 0.24 years, and 48.70% were male.

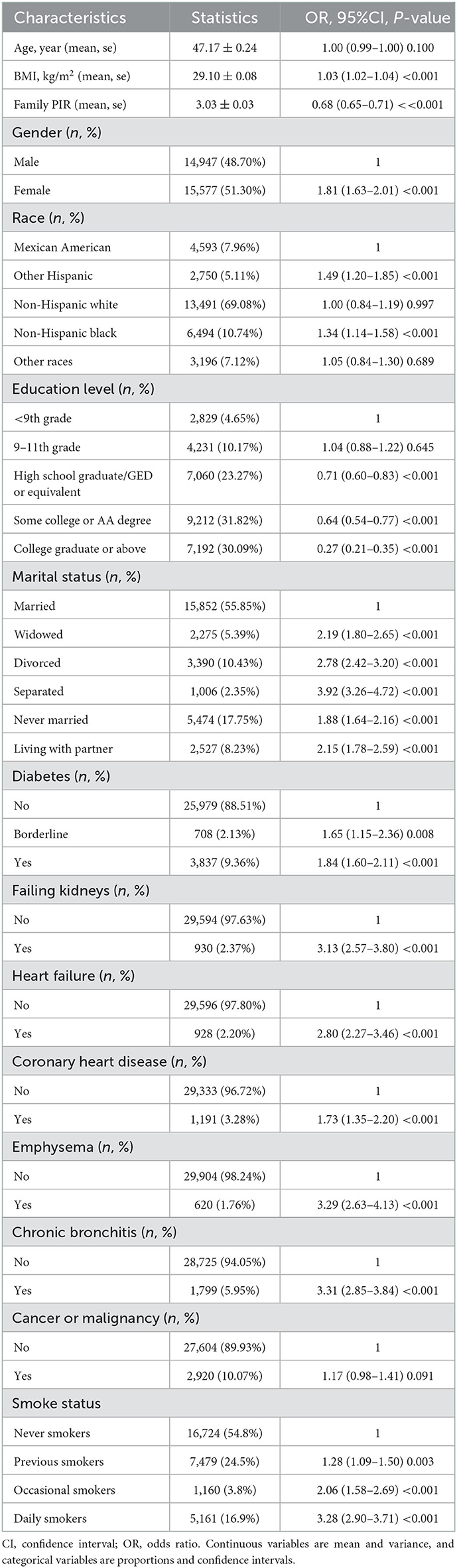

Among the analyzed sample participants, 54.8% (n = 16,724) were never smokers, 24.5% (n = 7,479) were previous smokers, 3.8% (n = 1,160) were occasional smokers, and 16.9% (n = 5,161) were daily smokers. Compared with other groups, daily smokers were younger, primarily men, non-Hispanic whites and non-Hispanic blacks, and had lower BMI, family PIR, and education levels. In addition, they were most likely to be divorced or living with their parents, suffering from heart failure, emphysema, chronic bronchitis, depression, and other diseases. The specific baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1.

We observed significant differences in gender, BMI, race, education level, marital status, and family PIR between depressed and non-depressed individuals (P < 0.05) (Table 2). Diabetes, renal failure, heart failure, coronary heart disease, chronic bronchitis, emphysema, nausea, and tumor were highly correlated with depression (P < 0.05) (Table 2). Furthermore, daily smokers had the strongest association with depression compared with the other three groups (OR = 3.28, 95% CI: 2.90–3.71, P < 0.001).

Table 2. Univariate analysis of depressive symptoms in the study population based on smoking status.

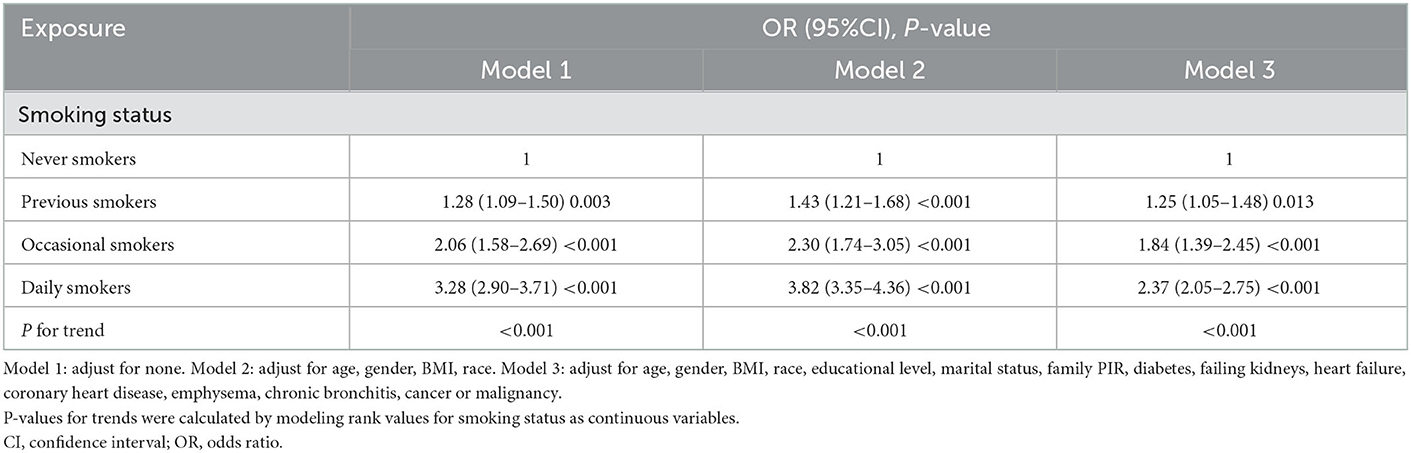

Table 3 shows that the association between smoking status and depression persisted after multiple adjustments for different confounders. Compared with never smokers, participants in the other three groups had an increased risk of depression (all models, P for trend < 0.001). Furthermore, compared with previous smokers (OR = 1.25, 95% CI: 1.05–1.48, P < 0.05) and occasional smokers (OR = 1.84, 95% CI: 1.39–2.45, P < 0.05), daily smokers had a 1.3–1.9-fold increased risk of depression (OR = 2.37, 95% CI: 2.05–2.75, P < 0.05).

Table 3. Associations of smoking status with clinically relevant depressive symptoms among adults (n = 16,724) in NHANES (2005–2018).

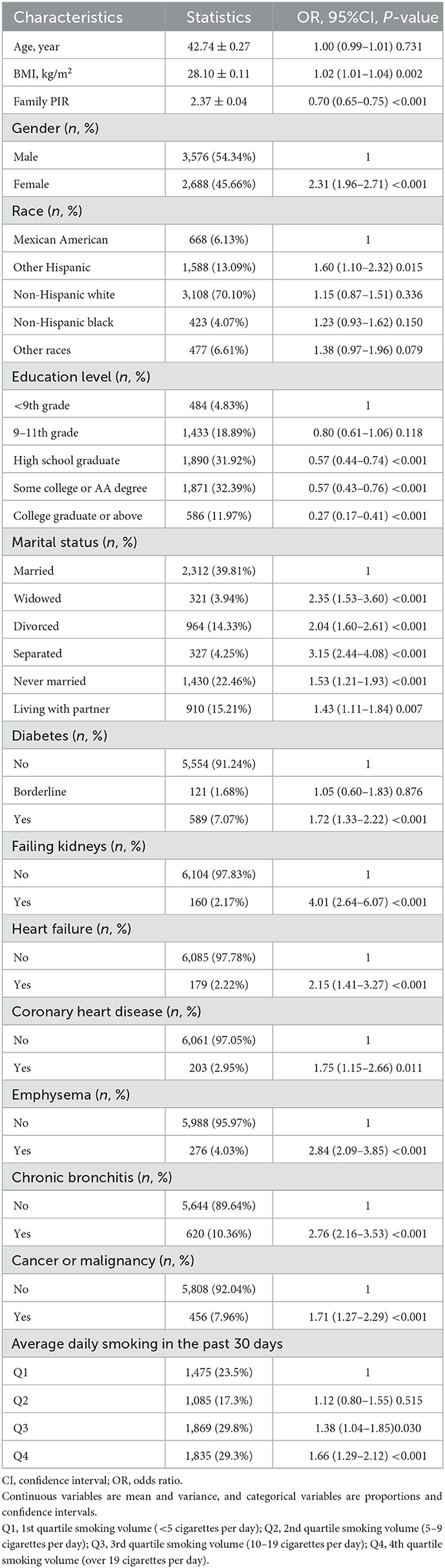

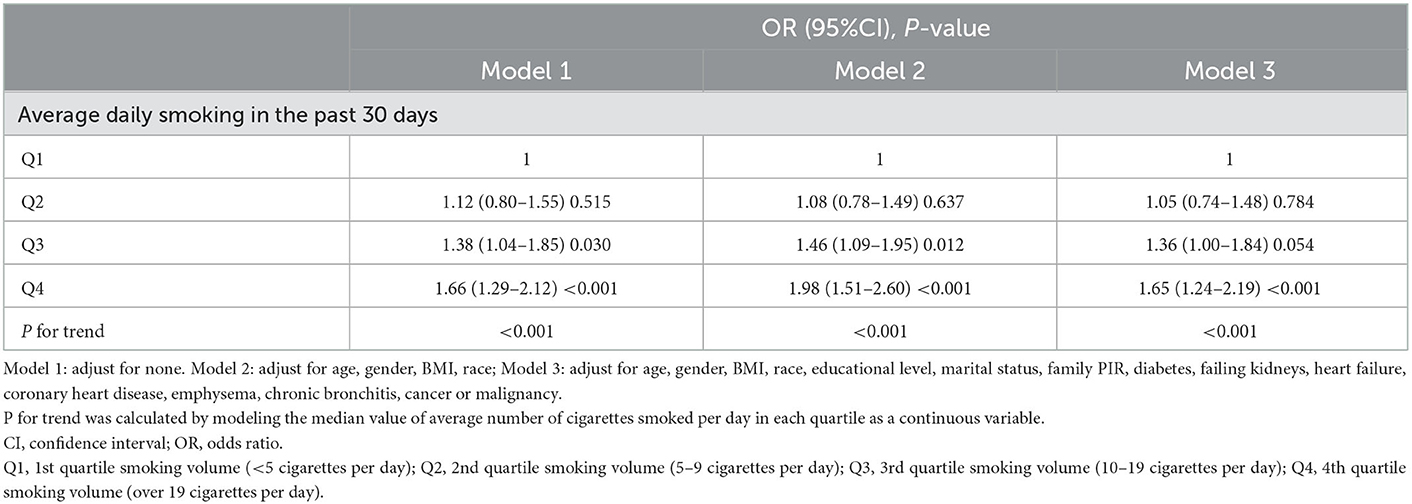

Among the participants, 6,246 provided complete daily smoking data for the past 30 days. Their average age was 42.74 ± 0.27 years, and 48.70% were male. Based on baseline results for average daily smoking in the four groups (Q1 to Q4), compared to the other three groups, the Q4 group that smoked the most number of cigarettes per day was older with fewer females, and mainly included non-Hispanic whites, widowed or divorced people, who had lower education level and higher prevalence of diabetes, emphysema, chronic bronchitis, cancer or malignant tumors, depression, and other diseases (Table 4).

Table 5 shows that BMI, race, education level, marital status, family PIR, hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), and dietary intake significantly varied between depressed and non-depressed groups. Diabetes, renal failure, heart failure, coronary heart disease, chronic bronchitis, emphysema, nausea, and tumor were highly correlated with depression (P < 0.05). Compared with the other three groups, the Q4 group showed a higher correlation with depression (OR = 1.66, 95% CI: 1.29–2.12, P < 0.001).

Table 5. Univariate analysis of depressive symptoms in the study population based on average daily smoking in the past 30 days.

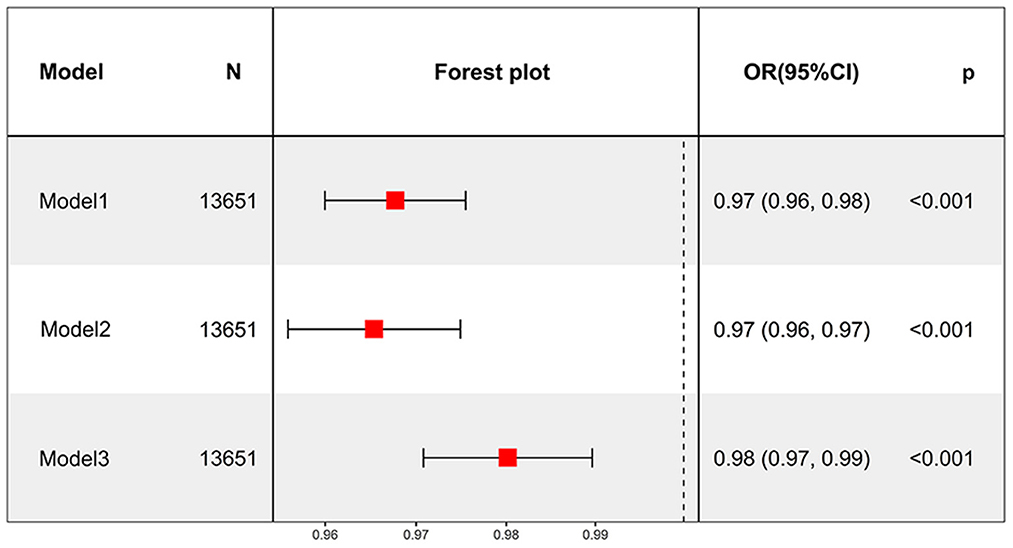

The relationship between average daily smoking volume and depression was described by adjusting for different confounding factors. All three models showed that daily smoking was associated with an increased risk of depression. Model III showed that smoking one more cigarette a day was associated with a 2% increased likelihood of depression (OR = 1.02, 95% CI: 1.01–1.03, P < 0.001) (Figure 2). After converting continuous variables to categorical variables, all three models still showed that smoking was associated with an increased risk of depression (all models, P for trend < 0.001). Model III showed that compared with the Q1 group with the least daily smoking volume, the Q2 and Q3 groups had no significantly increased risk of depression (P > 0.05), whereas the Q4 group had a significantly increased risk of depression (OR = 1.65, 95% CI: 1.24–2.19, P < 0.001) (Table 6).

Figure 2. Average daily smoking in the past 30 days as a continuous variable to analyze the relationship between average daily smoking and depression.

Table 6. Average daily smoking in the past 30 days as categorical variables to analyze the relationship between average daily smoking and depression in adults (n = 6,264) in NHANES (2005–2018).

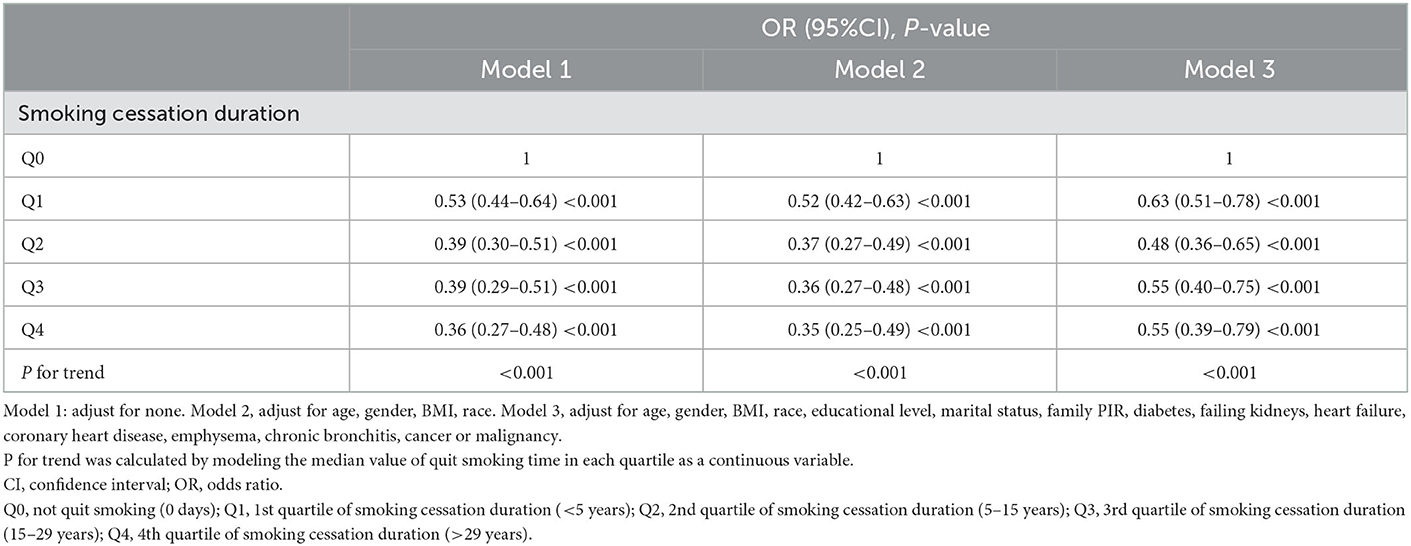

A total of 13,651 people were examined in this analysis, including 7,330 quitters and 6,321 current smokers. Their mean age was 48.65 ± 0.27 years, and 55.82% were male. Table 7 shows that, compared with the other four groups, the Q4 group with the longest smoking cessation duration was older with higher income, married; included mostly males, non-Hispanic whites; and had higher education levels, a higher prevalence of diabetes, renal failure, heart failure, coronary heart disease, emphysema, chronic bronchitis, and cancer or malignant tumor.

In addition, we observed differences (P < 0.05) in age, BMI, gender, race, education level, marital status, and family PIR between depressed and non-depressed individuals (Table 8). Diabetes, renal failure, heart failure, coronary heart disease, chronic bronchitis, emphysema, nausea, and tumor were highly correlated with depression (P < 0.05) (Table 8). Compared with the other four groups, the Q4 group was the least prone to depression (OR = 0.36, 95% CI: 0.27–0.48, P < 0.001).

Table 8. Univariate analysis of depressive symptoms in the study population based on smoking cessation status.

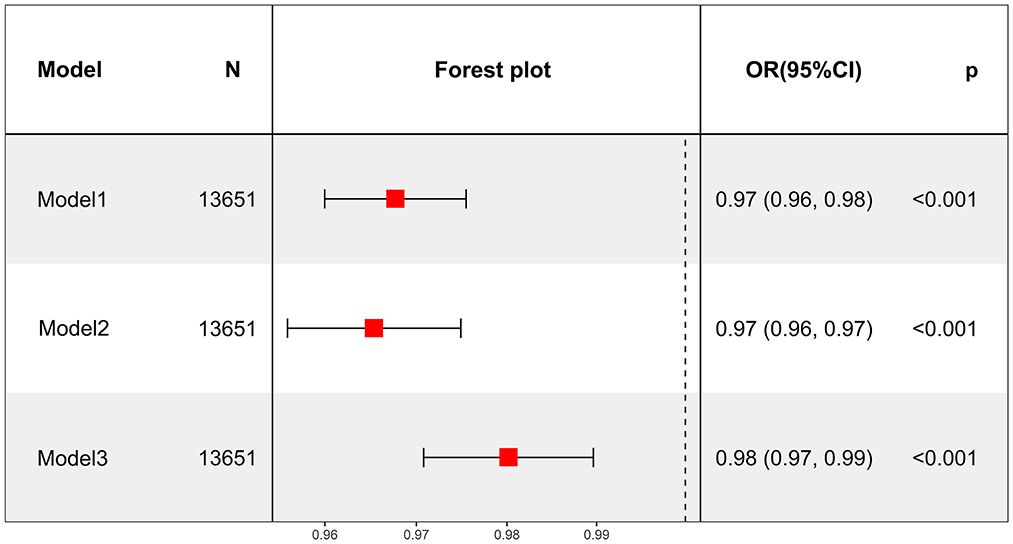

Model III confirmed that each additional year of smoking cessation was associated with a 2% decrease in the likelihood of developing depression after adjusting for most confounders (OR = 0.98, 95% CI: 0.97–0.99, P < 0.001) (Figure 3). After converting continuous variables to categorical variables, all three models still showed that smoking cessation duration was inversely related to depression (all models, P for trend < 0.001). Model III revealed a 45% reduced risk of depression in both the Q3 and Q4 groups (Table 9).

Figure 3. Smoking cessation duration as a continuous variable to analyze the relationship between smoking cessation and depression.

Table 9. Smoking cessation duration as categorical variables to analyze the relationship between smoking cessation and depression in adults (n = 13,651) in NHANES (2005–2018).

There is ongoing controversy regarding whether smoking increases the risk of depression (6, 15) or not (16–19). The present study first examined the association between smoking status and depression by analyzing data in the NHANES database (2005–2018). It was found that smokers had a significantly increased likelihood of developing depression than non-smokers. Compared with people who have never been exposed to tobacco (never smokers), those who have smoked in the past (previous smokers), currently smoke (occasional smokers), and who smoke every day (daily smokers) had an increased risk of depression in the given order. This result supports a conclusion that has been increasingly accepted in recent years: smoking increases the risk of depression (20). Next, we analyzed the relationship between smoking volume and depression. The findings showed that the higher the daily smoking volume, the more severe the risk of depression. This result confirms that smoking volume is positively related to the risk of depression, which is similar to the findings of some previous studies (21), and further supports the conclusion that smoking increases the risk of depression. These associations persisted even after adjusting for known confounders such as age, gender, BMI, race, education level, marital status, family PIR, diabetes, failing kidneys, heart failure, coronary heart disease, emphysema, chronic bronchitis, and cancer or malignancy.

However, some scholars believe that the high incidence of depression in smokers is not caused by smoking but that depressed people tend to smoke because they prefer to use tobacco to improve their mental status—the self-medication hypothesis (22, 23). Tobacco contains substances, such as nicotine, which are primarily used to excite the brain. Nicotine mainly acts on nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs), which stimulate the release of substances such as norepinephrine, serotonin, dopamine, acetylcholine, γ-aminobutyric acid, and glutamate secretion in the brain (24). The brain regions involved in these activities include the lateral septum, dorsal raphe nucleus, mesolimbic dopamine system, and hippocampus, which regulate stress response, anxiety, and depression pathways, thus affecting anxiety level and mood (25). Although the short-term pharmacological effect of nicotine is to stimulate the brain and relieve stress, anxiety, and depression (26), long-term use of nicotine is prone to addiction, which can cause mental and psychological damage, making people more sensitive and vulnerable, and more prone to depression or anxiety (27). These explanations also corroborate the idea that smoking increases the risk of depression.

Finally, we analyzed the association between smoking cessation and depression, and the results showed that the longer the smoking cessation duration, the lower the risk of depression. This inversely proves that smoking increases the risk of depression. As nicotine is addictive, withdrawal symptoms early in smoking cessation can aggravate discomfort, causing anxiety and depression (28). If the self-medication hypothesis holds that smokers smoke to relieve mental discomfort, they will have difficulty quitting smoking. Moreover, smoking cessation is associated with an increased risk of depression due to the loss of the therapeutic effect of tobacco. This inference is contrary to the findings of this study and some previous similar studies (11). It has even been reported that smokers feel happier when they quit smoking, which researchers fear could be a reason for people to smoke (29, 30). However, according to our results, although former smokers had a reduced risk of depression compared with smokers, they had a higher risk of depression than those who had never been exposed to nicotine, which may be due to the toxic effects of long-term nicotine use on the nervous system (4). Thus, smoking for the joy of quitting smoking could lead to adverse health outcomes.

This study has several strengths: (1) The data are obtained from the NHANES database, which is relatively standardized and increases the reliability of the results; (2) Cross-sectional research with a large sample size, standardized data collection, and reliable information is more objective (31); (3) We analyzed the relationship between smoking and depression from three aspects, that is, smoking status, smoking volume, and smoking cessation. The study also has shortcomings. First, the data we analyzed came from US citizens; therefore, the results of this study may not be applicable to other countries or regions. Second, this is a cross-sectional study, and the evidence of causality is not as good as in longitudinal studies, let alone clinical randomized control analysis.

In summary, we believe that smoking is a behavior that increases the risk of depression. The higher the smoking frequency and smoking volume, the higher the risk of depression, whereas smoking cessation reduces the risk of depression, and the longer the smoking cessation duration, the lower the risk of depression.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Review Board of the National Center for Health Statistics. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

ZW and XZ reviewed the literature, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. ZZha, JW, YY, and QY reviewed the literature. ZZho, LT, and JY prepared all the figures and tables. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

This study was supported by the First People's Hospital of Changde City (2022ZZ11) and COVID-19 Emergency Special Project of Changde Science and Technology Bureau (2020SK005).

The authors would like to acknowledge the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) for providing data.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Wootton RE, Richmond RC, Stuijfzand BG, Lawn RB, Sallis HM, Taylor GMJ, et al. Evidence for causal effects of lifetime smoking on risk for depression and schizophrenia: a Mendelian randomisation study. Psychol Med. (2020) 50:2435–43. doi: 10.1017/S0033291719002678

2. Weinberger AH, Kashan RS, Shpigel DM, Esan H, Taha F, Lee CJ, et al. Depression and cigarette smoking behavior: a critical review of population-based studies. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. (2017) 43:416–31. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2016.1171327

3. Cuijpers P, Quero S, Dowrick C, Arroll B. Psychological treatment of depression in primary care: recent developments. Curr Psychiatry Rep. (2019) 21:129. doi: 10.1007/s11920-019-1117-x

4. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Lowe B. The patient health questionnaire somatic, anxiety, and depressive symptom scales: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. (2010) 32:345–59. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.03.006

5. Park LT, Zarate CA Jr. Depression in the primary care setting. N Engl J Med. (2019) 380:559–68. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1712493

6. Taylor GMJ, Munafo MR. What about treatment of smoking to improve survival and reduce depression? Lancet Psychiatry. (2018) 5:464. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30132-9

7. Sheals K, Tombor I, McNeill A, Shahab L. A mixed-method systematic review and meta-analysis of mental health professionals' attitudes toward smoking and smoking cessation among people with mental illnesses. Addiction. (2016) 111:1536–53. doi: 10.1111/add.13387

8. Munafo MR, Hitsman B, Rende R, Metcalfe C, Niaura R. Effects of progression to cigarette smoking on depressed mood in adolescents: evidence from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Addiction. (2008) 103:162–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02052.x

9. Taylor G, Girling A, McNeill A, Aveyard P. Does smoking cessation result in improved mental health? A comparison of regression modelling and propensity score matching. BMJ Open. (2015) 5:e008774. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008774

10. Cavazos-Rehg PA, Breslau N, Hatsukami D, Krauss MJ, Spitznagel EL, Grucza RA, et al. Smoking cessation is associated with lower rates of mood/anxiety and alcohol use disorders. Psychol Med. (2014) 44:2523–35. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713003206

11. Liu S, Jiang H, Zhang D, Luo J, Zhang H. The association between smoking cessation and depressive symptoms: diet quality plays a mediating role. Nutrients. (2022) 14:3047. doi: 10.3390/nu14153047

12. Paulose-Ram R, Graber JE, Woodwell D, Ahluwalia N. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 2021–2022: adapting data collection in a COVID-19 environment. Am J Public Health. (2021) 111:2149–56. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2021.306517

13. Lei J, Luo Y, Xie Y, Wang X. Visceral adiposity index is a measure of the likelihood of developing depression among adults in the United States. Front Psychol. (2022) 13:772556. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.772556

14. Fan JX, Wen M, Li K. Associations between obesity and neighborhood socioeconomic status: variations by gender and family income status. SSM Popul Health. (2020) 10:100529. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100529

15. Park S, Lee KS. Association of heated tobacco product use and secondhand smoke exposure with suicidal ideation, suicide plans and suicide attempts among Korean adolescents: a 2019 national survey. Tob Induc Dis. (2021) 19:72. doi: 10.18332/tid/140824

16. Frerichs RR, Aneshensel CS, Clark VA, Yokopenic P. Smoking and depression: a community survey. Am J Public Health. (1981) 71:637–40. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.71.6.637

17. Mino Y, Shigemi J, Otsu T, Ohta A, Tsuda T, Yasuda N, et al. Smoking and mental health: cross-sectional and cohort studies in an occupational setting in Japan. Prev Med. (2001) 32:371–5. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0803

18. Anstey KJ, von Sanden C, Sargent-Cox K, Luszcz MA. Prevalence and risk factors for depression in a longitudinal, population-based study including individuals in the community and residential care. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2007) 15:497–505. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31802e21d8

19. Li Y, Zhang C, Ding S, Li J, Li L, Kang Y, et al. Physical activity, smoking, alcohol consumption and depressive symptoms among young, early mature and late mature people: a cross-sectional study of 76,223 in China. J Affect Disord. (2022) 299:60–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.11.054

20. Fluharty M, Taylor AE, Grabski M, Munafo MR. The association of cigarette smoking with depression and anxiety: a systematic review. Nicotine Tob Res. (2017) 19:3–13. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntw140

21. Khaled SM, Bulloch AG, Williams JV, Hill JC, Lavorato DH, Patten SB. Persistent heavy smoking as risk factor for major depression (MD) incidence–evidence from a longitudinal Canadian cohort of the National Population Health Survey. J Psychiatr Res. (2012) 46:436–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.11.011

22. Markou A, Kosten TR, Koob GF. Neurobiological similarities in depression and drug dependence: a self-medication hypothesis. Neuropsychopharmacology. (1998) 18:135–74. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(97)00113-9

23. Secades-Villa R, Weidberg S, Gonzalez-Roz A, Reed DD, Fernandez-Hermida JR. Cigarette demand among smokers with elevated depressive symptoms: an experimental comparison with low depressive symptoms. Psychopharmacology. (2018) 235:719–28. doi: 10.1007/s00213-017-4788-1

24. Haustein KO, Haffner S, Woodcock BG. A review of the pharmacological and psychopharmacological aspects of smoking and smoking cessation in psychiatric patients. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. (2002) 40:404–18. doi: 10.5414/CPP40404

25. Picciotto MR, Brunzell DH, Caldarone BJ. Effect of nicotine and nicotinic receptors on anxiety and depression. Neuroreport. (2002) 13:1097–106. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200207020-00006

26. Thrul J, Gubner NR, Tice CL, Lisha NE, Ling PM. Young adults report increased pleasure from using e-cigarettes and smoking tobacco cigarettes when drinking alcohol. Addict Behav. (2019) 93:135–40. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.01.011

27. Piirtola M, Kaprio J, Baker TB, Piasecki TM, Piper ME, Korhonen T. The associations of smoking dependence motives with depression among daily smokers. Addiction. (2021) 116:2162–74. doi: 10.1111/add.15390

28. Copeland AL, Kulesza M, Hecht GS. Pre-quit depression level and smoking expectancies for mood management predict the nature of smoking withdrawal symptoms in college women smokers. Addict Behav. (2009) 34:481–3. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.12.007

29. Shahab L, West R. Do ex-smokers report feeling happier following cessation? Evidence from a cross-sectional survey. Nicotine Tob Res. (2009) 11:553–7. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp031

30. Dos Santos VA, Migott AM, Bau CH, Chatkin JM. Tobacco smoking and depression: results of a cross-sectional study. Br J Psychiatry. (2010) 197:413–4. doi: 10.1192/bjp.197.5.413

Keywords: smoking, smoking cessation, depression, NHANES, PHQ-9

Citation: Wu Z, Yue Q, Zhao Z, Wen J, Tang L, Zhong Z, Yang J, Yuan Y and Zhang X (2023) A cross-sectional study of smoking and depression among US adults: NHANES (2005–2018). Front. Public Health 11:1081706. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1081706

Received: 27 October 2022; Accepted: 12 January 2023;

Published: 30 January 2023.

Edited by:

Md. Rabiul Islam, University of Asia Pacific, BangladeshReviewed by:

Louis Trevisan, Creighton University, United StatesCopyright © 2023 Wu, Yue, Zhao, Wen, Tang, Zhong, Yang, Yuan and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiaobo Zhang,  Mjg1MDU4MDQxQHFxLmNvbQ==

Mjg1MDU4MDQxQHFxLmNvbQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.