94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Public Health, 30 March 2023

Sec. Public Health Policy

Volume 11 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1078980

This article is part of the Research TopicHealth Systems Recovery in the Context of COVID-19 and Protracted ConflictView all 24 articles

Seja Abudiab1*

Seja Abudiab1* Diego de Acosta2

Diego de Acosta2 Sheeba Shafaq3

Sheeba Shafaq3 Katherine Yun4

Katherine Yun4 Christine Thomas5

Christine Thomas5 Windy Fredkove6

Windy Fredkove6 Yesenia Garcia7

Yesenia Garcia7 Sarah J. Hoffman8

Sarah J. Hoffman8 Sayyeda Karim6

Sayyeda Karim6 Erin Mann6

Erin Mann6 Kimberly Yu2

Kimberly Yu2 M. Kumi Smith9

M. Kumi Smith9 Tumaini Coker1

Tumaini Coker1 Elizabeth Dawson-Hahn1

Elizabeth Dawson-Hahn1This article is part of the Research Topic ‘Health Systems Recovery in the Context of COVID-19 and Protracted Conflict’

Introduction: Refugee, immigrant and migrant (hereafter referred to as “immigrant”) communities have been inequitably affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. There is little data to help us understand the perspectives of health systems on their role, in collaboration with public health and community-based organizations, in addressing inequities for immigrant populations. This study will address that knowledge gap.

Methods: This qualitative study used semi-structured video interviews of 20 leaders and providers from health systems who cared for immigrant communities during the pandemic. Interviewees were from across the US with interviews conducted between November 2020–March 2021. Data was analyzed using thematic analysis methods.

Results: Twenty individuals representing health systems participated with 14 (70%) community health centers, three (15%) county hospitals and three (15%) academic systems represented. The majority [16 health systems (80%)] cared specifically for immigrant communities while 14 (70%) partnered with refugee communities, and two (10%) partnered with migrant farm workers. We identified six themes (with subthemes) that represent roles health systems performed with clinical and public health implications. Two foundational themes were the roles health systems had building and maintaining trust and establishing intentionality in working with communities. On the patient-facing side, health systems played a role in developing communication strategies and reducing barriers to care and support. On the organizational side, health systems collaborated with public health and community-based organizations, in optimizing pre-existing systems and adapting roles to evolving needs throughout the pandemic.

Conclusion: Health systems should focus on building trusting relationships, acting intentionally, and partnering with community-based organizations and public health to handle COVID-19 and future pandemics in effective and impactful ways that center disparately affected communities. These findings have implications to mitigate disparities in current and future infectious disease outbreaks for immigrant communities who remain an essential and growing population in the US.

The COVID-19 pandemic has disproportionately affected the health of refugee, immigrant, and migrant communities in the United States (1) (hereafter, “immigrant” communities1). Although national-level statistics are sparse, immigrant communities have lower COVID-19 testing prevalence, higher COVID-19 positivity (2), more severe COVID-19 (3, 4) infection and mortality rates twice as high as non-immigrant communities (5, 6). The reasons for these disparities fall into three main categories: community context, health system access, and community experience with government agencies (including public health).

At the community level, multigenerational and higher density housing is a source of collective strength for immigrant communities. However, being near family and social support can increase risk of COVID-19 exposure (7). Moreover, immigrants are often “essential” workers and therefore were excluded from “stay home, stay safe” early in the pandemic (8–10). At the level of health system access, systemic racism and xenophobia prevent equitable access to quality healthcare (11). Immigrants are more likely to be uninsured than their peers (8, 12), and uninsured people are more likely to be hospitalized with COVID-19 infection, adjusting for age, race, ethnicity, and comorbidities (13). At the level of experience with government agencies, fear of legal repercussions from immigration policy is associated with increased risk of COVID-19 infection and decreased healthcare utilization (14, 15). Immigrants also face barriers to inclusion in public health programs, including case investigation and contact tracing (CICT) (16, 17), prompting calls for improved language access within CICT programs and rapid dispersal of culturally and linguistically appropriate public health messaging (14, 18).

Clinicians are often trusted health information messengers (19). When clinicians and health systems gain the trust of immigrant communities, access to healthcare improves (20). Therefore, health systems are critical stakeholders in the public health response to COVID-19 to ensure that programs are effective and inclusive of immigrant communities (21). There is little data, however, describing how health systems serving immigrant communities have navigated the public health response to the COVID-19 pandemic (22). We aim to address this gap in the literature.

We used a qualitative interview study design with data collected for a qualitative needs assessment at the National Resource Center for Refugees, Immigrants and Migrants (Supplementary material). The project was deemed non-human subjects research by the University of Minnesota and exempt by the University of Washington. This exemption status was granted given participants were members of health systems and considered non-vulnerable participants.

To capture the scope and variation of health system involvement in the public health response, we recruited participants through stratified purposive sampling (23) across specialities, resources, and geography [including all United States Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) regions]. We recruited participants through emails and webforms in existing networks of health care providers, including the Society of Refugee Healthcare Providers, Migrant Clinicians Network, American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Immigrant Child and Family Health, International Rescue Committee, and the Community Leadership Board of NRC-RIM. We sampled health system settings including: academic centers, small rural hospitals, and community health centers. We focused on health systems with established programs serving immigrant communities and anticipated thematic saturation at 20 interviews. Eligible interviewees were individuals from health systems who directly interacted with immigrant communities during the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., physicians, nurses, administrative staff).

We conducted Zoom interviews which lasted up to 60 minutes between 11/11/20 and 3/25/21, using a semi-structured interview guide. The interviews were audio-recorded and professionally transcribed. Interviewees received no compensation. We collected interviewee demographic information including years in practice, education and healthcare setting via REDCap electronic data capture tools to ensure we included the right organizational representatives (24, 25).

We developed a preliminary codebook deductively from the interview guide and added inductive codes based on concepts identified in the data. All interviews were coded in Dedoose (26). We held weekly meetings to discuss codebook definitions, emerging codes, and specific excerpts. Finally, we reviewed coded data to identify themes and created a conceptual map of their interrelations based on the thematic analysis methods of Braun and Clarke (27).

We completed 20 interviews across all HHS regions (Table 1) representing communities from over 30 countries (Table 2). There were interviewees from 14 community health centers (70%), three county hospitals (15%), and three academic health systems (15%). Fourteen of the health systems worked specifically with refugees (70%), two with migrant farmworkers (10%), and 16 with other immigrants (80%). Ten (50%) interviews preceded the Pfizer vaccine emergency use authorization (28). Each interviewee spoke from their own perspective, while also representing their health system and its collective efforts.

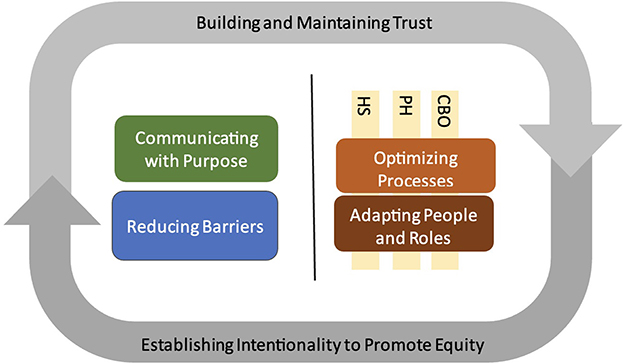

We identified six themes with subthemes: two foundational themes (Table 3) and four operational themes that straddle the inward (organizational/administrative) and outward (patient-facing) roles of health systems (Table 4). The themes are displayed in a conceptual map in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Thematic map demonstrating health system roles on the inward-facing (right of gray line) and outward-facing (left of gray line) aspects of healthcare delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic, enveloped by trust and intentionality. CBO, community-based organization; PH, public health; HS, health systems.

The foundational themes (theme 1 and 2) are identified as they represented a common thread observed in the operational themes and represented the manner in which the operational themes (themes 3–6) were conducted. The foundational themes represent “how” processes occurred while the operational themes represent “what” processes occurred. We will introduce the foundational themes first to ground the basic approach used to guide actions taken by health system.

In what follows, themes are given in numbered section headings and subthemes are given in italics.

Health systems quickly recognized health disparities specific to immigrant communities and responded by acting intentionally to provide equitable care.

Early on, interviewees discerned that the pandemic “highlighted disparities and magnified them.” One interviewee acknowledged the “oppression from the period of being a refugee, being resettled and then [navigating] social systems... living at the poverty level for a minimum of a decade.” Interviewees noted the disproportionate impact on immigrant communities, including increased COVID-19 exposure risk and more severe disease. They also recognized the challenges communities faced with higher prevalence of comorbidities and lower access to healthcare. Finally, interviewees acknowledged the potential hardships of following public health protocols. One interviewee mentioned a patient who declined COVID testing explaining, “If I test positive, I can't go to work… I can't make money and I can't afford housing for my child.”

Interviewees worked to address health disparities, especially through health system responses centering immigrant communities. One interviewee described tailoring access and “being very intentional… really meeting people where they gather,” while another mentioned strategies to bridge the digital divide. Interviewees also reported how their health systems addressed disparities in testing prevalence. One interviewee said they “convince[d] all the clinical partners and the county that if a patient showed up at the... testing center, that they would just get tested without any questions asked.” Some interviewees described how meeting with multiple regional stakeholders allowed them to shift resources to areas of need.

Interviewees described how they addressed disparities in follow-up with COVID-positive patients. One health system took the unusual step of modifying monitoring protocols to ensure that “limited English proficiency populations… were always placed in the high-risk category, meaning they get the special attention from the outset [by the care team].”

In sum, when interviewees considered how they had interacted with both communities and health systems, they emphasized the importance of maintaining an awareness of disparities and intentionally addressing these disparities through both inward (organizational/administrative) and outward (patient-facing) actions.

Interviewees evaluated immigrant patients' attitude toward health systems and worked to enhance patient trust.

Interviewees assessed immigrant patients' attitudes toward health systems and entities perceived to be associated with health systems before taking steps to building trust. Loss of trust is not just historic, as one interviewee explained: patients today “get tons of terrible bills that don't make any sense, and they're often shafted because they don't speak English.” Interviewees understood that certain aspects of the public health response were challenging “because a lot of [immigrant patient communities] have a little bit of uncertainty around their immigration status… giving out a lot of information feels pretty uncomfortable.” Interviewees mentioned reasons for distrust, including “fear of discovery” and legal repercussions like deportation.

Interviewees worked to cultivate the conditions for patient trust using three main strategies: investment over time, harnessing trusted relationships, and transparency. Interviewees recognized that building trust takes time: “The belief that you can all of a sudden show up and say, ‘We're here to help you. Let's give you tests,' doesn't work.” One interviewee stressed that a key to trust-building is having “partnerships in place [that] can be rapidly operationalized for these sorts of crises, and that means years of building trust and sharing power.” Interviewees noted they could support refugees by working with established, trusted entities. “Harnessing relationships that people trust” was key in building trust between health systems and communities. Interviewees acknowledged the fast-changing landscape of COVID-19 misinformation and addressed the need for transparency to build trust. One interviewee discussed vaccination saying, “I took it, our CEO took it, and did a video, and [said] hey, if we turn into zombies tomorrow, we'll let you know… and I think that's what kind of generated this trust.”

As interviewees took steps to understand and ameliorate sources of distrust in health systems, they were able to center their communities in their health system's operational response.

Interviewees played a role in delivering the public messages used to communicate to communities in ways and through mediums that were linguistically, culturally, and situationally appropriate while also listening to the community.

Interviewees discussed the importance of crafting a succinct, consistent message when information about COVID-19 was rapidly changing and misinformation was widespread. Interviewees tried to match communication strategies to each community's language(s), literacy levels, cultural values, trusted leaders, preferred media, and technology use (e.g., communicating through a resettlement agency that used WhatsApp). They emphasized the messenger: “find a spokesperson… in the community that people know, and trust, and believe.”

Interviewees adopted a bidirectional approach to communication by informing immigrant communities about COVID-19 while gathering their questions and concerns. One interviewee described switching to less invasive saliva-based testing because “we heard from the community leaders that there was a lot of misinformation around … the invasiveness of the swab, as well as the concern that the swab was actually infecting people.”

Interviewees recognized their role in encouraging public health measures for communities by reducing barriers to patient care, barriers to receiving emergency assistance, and barriers at work.

Interviewees reduced barriers to direct patient care related to language, technology, scheduling, transportation, and documentation. One strategy was simply keeping clinics open and communicating with patients. Another strategy was ensuring that patients could navigate services in a language they understood: “Where we really pride ourselves is, we are the communities that we serve, so we have staff who are bilingual, bicultural… the services that we provide are… very deeply rooted in the cultures that our patients are from.” Interviewees also worked to make health measures practical for patients by providing them with supplies like masks and pulse oximeters.

To improve opportunities for testing, health systems offered options that were physically accessible: drive-up, pop-up, or mobile testing near patients' homes. Interviewees reported allowing walk-up testing and scheduling by phone for patients unable to schedule online. Finally, many health systems offered testing without requiring insurance or extensive personal information.

Interviewees reduced barriers to emergency assistance and socioeconomic support by informing immigrant patients about resources, helping them navigate resources, and in some cases by providing direct assistance. Interviewees told immigrant patients about available unemployment and rental assistance and helped them apply. Many interviewees mentioned supplying families with food, striving to make it culturally appropriate whenever possible.

Interviewees recognized that immigrant workers and tenants faced inequitably harsh financial consequences in the event of illness because they often lacked employment/tenant protections. One interviewee said, “patients who are undocumented and don't have a lot of power in the workplace, they need to be supported in this way; whereas, people like you or me could potentially work from home.” Interviewees spoke with patients about work safety concerns, as well as the challenge of navigating public health measures while protecting employment and financial security. One interviewee recalled a patient diagnosed with COVID who “didn't want to get in trouble with her employer and lose her job forever.” Interviewees built relationships through direct communication with employers and landlords via letters, phone calls, and in-person visits. One interviewee shared how they provided employers with masks, sanitation support, and thermometers. When employers were unwilling to communicate, the health systems sought out third parties (e.g., boards of health, chambers of commerce, and offices of elected officials) to prompt employer compliance with public health measures.

Interviewees reported the pandemic created a need to develop new processes by collaborating and merging established systems with public health and community-based organizations and by repurposing spaces.

Interviewees provided examples of new processes, including a process to implement testing in high-density housing by sharing information with a municipal Housing Authority and Department of Health, and a process to expedite lag times between positive testing and public health CICT through data sharing. Interviewees also discussed combining established systems to provide new services. One example was supporting a community center's testing day by lending health system interpreters to facilitate communication. Collaborating with community partners was also effective: “our community partner organizations let their communities know about [testing] and helped them register, and they were present at the testing site to talk to people.”

The use of physical spaces and facilities was another area where interviewees reported adjusting to better accommodate the needs of immigrant communities. As the country went into lockdown, many public locations were empty, including schools. Schools and school-based health centers, often ideally located near immigrant communities and known as “trusted places for families,” became equipped for testing and other services.

Interviewees reported mobilizing and expanding human resources by collaborating with public health and community-based organizations to repurpose roles, capitalize on relationships, and support staff.

As the pandemic created a need for new roles, health systems were able to fill gaps by repurposing skilled staff. One interviewee praised a system's resource navigator whose role expanded to finding immigrant-specific resources during the pandemic. Another health system's interpreters conducted contact tracing with public health. In a smaller jurisdiction, one interviewee emphasized the flexibility their health system had because staff also held roles in the public health department: “a lot of double roles most of us play, it's a lot less bureaucracy to move and partner.”

A key to quickly addressing immigrant communities' needs was capitalizing on pre-existing relationships with community-based organizations and other stakeholders. One interviewee developed a relationship with members of the city government: “probably once a month, [we] talk about what's going on, whether it's jobs or neighborhood conditions or health issues.” These relationships ensured information sharing was reciprocal and included diverse perspectives to facilitate fast, effective, and equitable healthcare delivery.

Interviewees lamented the toll the pandemic took on health systems, particularly for employees from immigrant communities. One interviewee expressed concern for struggling staff who “were carrying so much.” As a result, this health system provided extra mental health support and piloted a curriculum for staff support groups. These groups were critical as the staff was “providing the support [to patients] but needing support themselves.”

As the COVID-19 pandemic surged, health systems caring for immigrant communities found themselves responding on two fronts: controlling a new disease and addressing recurrent disparities. Our analysis found health systems addressing both fronts in their outward patient-facing roles as well as their inward-facing, administrative roles. These findings have implications for the remainder of and recovery from this pandemic, future infectious disease outbreaks (i.e., MPX or Monkeypox) and other disaster preparedness efforts as immigrant communities remain an essential and growing population in the US (see action items in Table 5). As it pertains to the COVID-19 pandemic, health systems must repair damage done to their relationships with disproportionately affected immigrant communities. Operational lessons from this pandemic can inform recovery measures that promote resilience in the relationships fostered between health systems and the communities they serve.

We found two key themes that underpinned all other themes: intentionality and trust. Health systems are better positioned to plan and execute successful interventions and recovery measures when they understand the diverse situational context and disparities specific to immigrant communities (29–32). By understanding context, health systems can manage their many roles: creating messaging that is linguistically appropriate, recognizing patients' vulnerabilities in the workplace and actively engaging with employers, and identifying areas in the community that are familiar and accessible for testing. Health systems recognized this contextual heterogeneity and adjusted their approaches to the needs and perspectives of their communities.

Just as health systems cannot plan their interventions without cultivating an awareness of burgeoning disparities for immigrant communities, they cannot successfully implement outreach strategies without trust (33–35). For some immigrant communities, concerns involving legal status and the fear of deportation (in the context of the public charge rule) sapped trust in the health system, resulting in fewer immigrants accessing healthcare benefits (10, 36, 37). Partnering with community advocates whose background and connections bring “home” to mind is a proven strategy for building trust throughout the pandemic, and trust supports resilience as partners develop stable relationships that can weather challenges through time (38–41). Our findings support that it takes time and deliberate effort to build trusting relationships with communities and to develop partnerships with community leaders and organizations, particularly before crises (33, 34). Community engagement and trust were vital to the success of the health system interviewees and are critical in preparing for future public health emergencies. While our study was US-focused, similar findings have been shared in studies with immigrant communities globally (42, 43).

We further appreciate the overarching importance of trust and intentionality when we consider healthcare delivery during a crisis. Responding adequately during the pandemic required collaboration between health systems, public health and community organizations/advocates across all processes and interventions. Collaboration fostered sharing data, resources, relationships, and expertise to address needs in critical moments. Health systems were able to use pre-existing processes and resources in combination and to a degree of efficiency that effectively transformed them into new approaches. This was evident through: sharing the benefits of pre-existing trusting relationships, data sharing on COVID-19 cases for geospatial mapping, and sharing established language resources to improve CICT. The benefits of collaboration across sectors to improve public health are well-documented (44, 45), particularly in past crises (46, 47). The cross-sector alignment theory of change developed by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation emphasizes alignment of public health, health systems and social services, and recognizes the importance of community engagement, without specifying the timing and extent of this engagement (48). Our findings suggest primary, constructive, and enduring collaborations with community-based organizations improved outreach and fostered trust.

This study has limitations worth noting. First, the recruitment method involved self-selection bias and as such, our analysis highlights positive deviance rather than dysfunction. The networks we recruited from and individuals who agreed to our interview represented health systems that identified as caring for immigrant communities; as such, these health systems are among the minority who likely had insight into, investment in, and resources for supporting the varying needs of their communities. This element of selection bias reduces the generalizability of this study. Second, our purposive sampling method limits representation. However, we recruited individuals from a range of health systems that cared for various immigrant communities to capture a diversity in responses. Third, we present the perspectives of health systems without the perspectives of public health and communities within the same jurisdiction, which limits our ability to draw definitive conclusions on the efficacy of collaboration. Nevertheless, this study's strength is the rich descriptions collected from 20 individuals within health systems who interacted with numerous immigrant communities. Future work should center voices from community members to better assess health system efficacy and represent actualized outcomes.

Immigrant communities have been disproportionately harmed by COVID-19. Our findings show that health systems addressed the magnified disparities affecting immigrants by sustaining and reimagining roles to align with the public health response. By focusing on building trust, ensuring intentionality in processes and interventions, and optimizing avenues for collaboration with public health and community partners, health systems can save lives in future public health emergencies.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

SA and DA had full access to all of the data in the study, take responsibility for the integrity of the data, the accuracy of the data analysis, and involved in drafting the manuscript. ED-H, KYun, and EM were responsible for the study concept, design, and involved in obtaining funding for this project. ED-H, KYun, SA, SH, SK, EM, KYu, CT, DA, WF, KS, and YG were all involved in the acquisition and analysis and interpretation of data. SA, DA, TC, SS, KYun, and ED-H were involved in the critical revision of the manuscript for the important intellectual content. SK provided administrative and technical and material support. ED-H and KYun were involved in study supervision. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This study was supported in part under the National Resource Center for Refugees, Immigrants, and Migrants which is funded by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the International Organization for Migration (award number CK000495-03-00/ES1874) to support health departments and community organizations working with Refugee, Immigrant, and Migrant communities that have been disproportionately affected by COVID-19. SA receives support from the University of Washington National Research Service Award—Child Health Equity Research Program for Post-doctoral Trainees (T32 HD101397). CT receives support from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health through the University of Minnesota T32 award (T32 AI055433). This study utilized REDCap electronic data capture tools which was funded by Institute of Translational Health Science (ITHS) grant support (UL1 TR002319, KL2 TR002317, and TL1 TR002318 from NCATS/NIH).

The authors would like to thank the Community Leadership Board at the National Resource Center for Refugees, Immigrants, and Migrants for their guidance with this project. We are grateful to the generous contributions to this work made by the interviewees and the people who provided connections to the interviewees. We appreciate the insights provided on this project by Dr. Michelle Weinberg and Dr. Bill Stauffer.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1078980/full#supplementary-material

1. ^While we will use the term “immigrant” communities, we understand that these communities are each unique with different and rich histories and lived experiences and are not a monolith.

1. Greenaway C, Hargreaves S, Barkati S, Coyle CM, Gobbi F, Veizis A, et al. COVID-19: exposing and addressing health disparities among ethnic minorities and migrants. J Travel Med. (2020) 27:taaa113. doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa113

2. Kim HN, Lan KF, Nkyekyer E, Neme S, Pierre-Louis M, Chew L, et al. Assessment of disparities in COVID-19 testing and infection across language groups in Seattle, Washington. JAMA Netw Open. (2020) 3:e2021213. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.21213

3. Wilder JM. The Disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minorities in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. (2020) 72:707–9. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa959

4. Alcendor DJ. Racial disparities-associated COVID-19 mortality among minority populations in the US. J Clin Med. (2020) 9:E2442. doi: 10.3390/jcm9082442

5. Horner KM, Wrigley-Field E, Leider JP. A first look: disparities in COVID-19 mortality among US-born and foreign-born Minnesota residents. Popul Res Policy Rev. (2021) 41:465–78. doi: 10.1007/s11113-021-09668-1

6. Garcia E, Eckel SP, Chen Z, Li K, Gilliland FD. COVID-19 mortality in California based on death certificates: disproportionate impacts across racial/ethnic groups and nativity. Ann Epidemiol. (2021) 58:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2021.03.006

7. Brito MO. COVID-19 in the Americas: who's looking after refugees and migrants? Ann Glob Health. (2020) 86:69. doi: 10.5334/aogh.2915

8. Batalova J, Hanna M, Levesque C. Frequently Requested Statistics on Immigrants Immigration in the United States. migrationpolicy.org. (2021). Available online at: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/frequently-requested-statistics-immigrants-and-immigration-united-states (accessed January 28, 2022).

9. Machado S, Goldenberg S. Sharpening our public health lens: advancing im/migrant health equity during COVID-19 and beyond. Int J Equity Health. (2021) 20:57. doi: 10.1186/s12939-021-01399-1

10. Touw S, McCormack G, Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S, Zallman L. Immigrant essential workers likely avoided Medicaid and SNAP because of a change to the public charge rule. Health Aff. (2021) 40:1090–8. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2021.00059

11. Mckee MM, Paasche-Orlow M. Health literacy and the disenfranchised: the importance of collaboration between limited English proficiency and health literacy researchers. J Health Commun. (2012) 17:7–12. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2012.712627

12. Health Coverage of Immigrants. KFF. (2021). Available online at: https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/fact-sheet/health-coverage-of-immigrants/ (accessed January 28, 2022).

13. Killerby ME. Characteristics associated with hospitalization among patients with COVID-19 — Metropolitan Atlanta, Georgia, March–April 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. (2020) 69:790–794.

14. Clark E, Fredricks K, Woc-Colburn L, Bottazzi ME, Weatherhead J. Disproportionate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on immigrant communities in the United States. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. (2020) 14:e0008484. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008484

15. Wong TK, Cha J, Villarreal-Garcia E. The Impact of Changes to the Public Charge Rule on Undocumented Immigrants Living in the U.S. US Immigration Policy Center (2019), p. 14. Available online at: https://usipc.ucsd.edu/publications/usipc-public-charge-final.pdf (accessed March 25, 2022).

16. Truman BI, Tinker T, Vaughan E, Kapella BK, Brenden M, Woznica CV, et al. Pandemic influenza preparedness and response among immigrants and refugees. Am J Public Health. (2009) 99:S278–86. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.154054

17. Vaughan E, Tinker T. Effective health risk communication about pandemic influenza for vulnerable populations. Am J Public Health. (2009) 99:S324–32. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.162537

18. Maleki P, Al Mudaris M, Oo KK, Dawson-Hahn E. Training contact tracers for populations with limited English proficiency during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Public Health. (2021) 111:20–4. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.306029

19. Chung Y, Schamel J, Fisher A, Frew PM. Influences on immunization decision-making among US parents of young children. Matern Child Health J. (2017) 21:2178–87. doi: 10.1007/s10995-017-2336-6

20. Cao QK, Krok-Schoen JL, Guo M, Dong X. Trust in physicians, health insurance, and health care utilization among Chinese older immigrants. Ethn Health. (2023) 28:78–95 doi: 10.1080/13557858.2022.2027881

21. Haldane V, De Foo C, Abdalla SM, Jung AS, Tan M, Wu S, et al. Health systems resilience in managing the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons from 28 countries. Nat Med. (2021) 27:964–80. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01381-y

22. Kim CS, Lynch JB, Cohen S, Neme S, Staiger TO, Evans L, et al. One academic health system's early (and ongoing) experience responding to COVID-19: recommendations from the initial epicenter of the pandemic in the United States. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. (2020) 95:1146–8. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003410

23. Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, Wisdom JP, Duan N, Hoagwood K. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm Policy Ment Health. (2015) 42:533–44. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y

24. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. (2009) 42:377–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010

25. Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, Elliott V, Fernandez M, O'Neal L, et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. (2019) 95:103208. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208

26. Dedoose Version 9,.0.17, Web Application for Managing, Analyzing, Presenting Qualitative Mixed Method Research Data. Los Angeles, CA: SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC (2021). Available online at: www.dedoose.com (accessed March 21, 2022).

27. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. (2006) 3:77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

28. Dwyer C. FDA Authorizes COVID-19 Vaccine For Emergency Use In U.S. NPR. (2020). Available online at: https://www.npr.org/sections/coronavirus-live-updates/2020/12/11/945366548/fda-authorizes-covid-19-vaccine-for-emergency-use-in-u-s (accessed February 15, 2022).

29. Chang CD. Social determinants of health and health disparities among immigrants and their children. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. (2019) 49:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2018.11.009

30. Khullar D, Chokshi DA. Challenges for immigrant health in the USA-the road to crisis. Lancet Lond Engl. (2019) 393:2168–74. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30035-2

31. Budiman A. Key findings about U.S. Immigrants. Pew Research Center. Available online at: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/08/20/key-findings-about-u-s-immigrants/ (accessed February 2, 2022).

32. Linton JM, Green A, Council Council on Community Pediatrics. Providing care for children in immigrant families. Pediatrics. (2019) 144:e20192077. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2077

33. Udow-Phillips M, Lantz PM. Trust in public health is essential amid the COVID-19 pandemic. J Hosp Med. (2020) 15:431–3. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3474

34. D'Alonzo KT, Greene L. Strategies to establish and maintain trust when working in immigrant communities. Public Health Nurs Boston Mass. (2020) 37:764–8. doi: 10.1111/phn.12764

35. Jin K, Neubeck L, Koo F, Ding D, Gullick J. Understanding prevention and management of coronary heart disease among Chinese immigrants and their family carers: a socioecological approach. J Transcult Nurs. (2020) 31:257–66. doi: 10.1177/1043659619859059

36. McFarling UL. Fearing Deportation, Many Immigrants at Higher Risk of Covid-19 are Afraid to Seek Testing or Care. STAT. (2020). Available online at: https://www.statnews.com/2020/04/15/fearing-deportation-many-immigrants-at-higher-risk-of-covid-19-are-afraid-to-seek-testing-or-care/ (accessed February 14, 2022).

37. La Rochelle C, Montoya-Williams, D, Wallis, K,. Thawing the Chill from Public Charge Will Take Time Investment. Children's Hospital of Philadelphia PolicyLab. (2021). Available online at: https://policylab.chop.edu/blog/thawing-chill-public-charge-will-take-time-and-investment (accessed February 11, 2022).

38. Karim N, Boyle B, Lohan M, Kerr C. Immigrant parents' experiences of accessing child healthcare services in a host country: a qualitative thematic synthesis. J Adv Nurs. (2020) 76:1509–19. doi: 10.1111/jan.14358

39. Behbahani S, Smith CA, Carvalho M, Warren CJ, Gregory M, Silva NA. Vulnerable immigrant populations in the New York Metropolitan Area and COVID-19: lessons learned in the epicenter of the crisis. Acad Med. (2020) 95:1827–30. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003518

40. Alwan RM, Kaki DA, Hsia RY. Barriers and facilitators to accessing health services for people without documentation status in an anti-immigrant era: a socioecological model. Health Equity. (2021) 5:448–56. doi: 10.1089/heq.2020.0138

41. Nickell A, Stewart SL, Burke NJ, Guerra C, Cohen E, Lawlor C, et al. Engaging limited English proficient and ethnically diverse low-income women in health research: a randomized trial of a patient navigator intervention. Patient Educ Couns. (2019) 102:1313–23. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2019.02.013

42. Deal A, Hayward SE, Huda M, Knights F, Crawshaw AF, Carter J, et al. Strategies and action points to ensure equitable uptake of COVID-19 vaccinations: a national qualitative interview study to explore the views of undocumented migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees. J Migr Health. (2021) 4:100050. doi: 10.1016/j.jmh.2021.100050

43. Nichol AA, Parcharidi Z, Al-Delaimy WK, Kondilis E. Rapid review of COVID-19 vaccination access and acceptance for global refugee, asylum seeker and undocumented migrant populations. Int J Public Health. (2022) 67:1605508. doi: 10.3389/ijph.2022.1605508

44. Rosen M. Impacting quadruple aim through sustainable clinical-community partnerships: best practices from a community-based organization perspective. Am J Lifestyle Med. (2020) 14:524–31. doi: 10.1177/1559827620910980

45. Johnston LM, Finegood DT. Cross-sector partnerships and public health: challenges and opportunities for addressing obesity and noncommunicable diseases through engagement with the private sector. Annu Rev Public Health. (2015) 36:255–71. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031914-122802

46. Millet O, Cortajarena AL, Salvatella X, Jiménez-Barbero J. Scientific response to the coronavirus crisis in Spain: collaboration and multidisciplinarity. ACS Chem Biol. (2020) 15:1722–3. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.0c00496

47. Ruckart PZ, Ettinger AS, Hanna-Attisha M, Jones N, Davis SI, Breysse PN. The flint water crisis: a coordinated public health emergency response and recovery initiative. J Public Health Manag Pract. (2019) 25(Suppl 1):S84–90. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000871

Keywords: refugee, immigrant, migrant, COVID-19, public health, health system

Citation: Abudiab S, de Acosta D, Shafaq S, Yun K, Thomas C, Fredkove W, Garcia Y, Hoffman SJ, Karim S, Mann E, Yu K, Smith MK, Coker T and Dawson-Hahn E (2023) “Beyond just the four walls of the clinic”: The roles of health systems caring for refugee, immigrant and migrant communities in the United States. Front. Public Health 11:1078980. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1078980

Received: 24 October 2022; Accepted: 06 March 2023;

Published: 30 March 2023.

Edited by:

Duncan Selbie, University of Chester, United KingdomReviewed by:

Lianne Urada, San Diego State University, United StatesCopyright © 2023 Abudiab, de Acosta, Shafaq, Yun, Thomas, Fredkove, Garcia, Hoffman, Karim, Mann, Yu, Smith, Coker and Dawson-Hahn. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Seja Abudiab, c2FidWRpQHV3LmVkdQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.