- 1Department of Health Management, The Third Xiangya Hospital and Xiangya School of Nursing, Central South University, Changsha, China

- 2Xiangya School of Nursing, Central South University, Changsha, Hunan, China

- 3School of Nursing, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, United States

- 4Pediatric Department of the Third Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha, Hunan, China

- 5Hunan Polytechnic of Environment and Biology, Hengyang, Hunan, China

Introduction: Many women experience severe emotional distress (such as grief, depression, and anxiety) following a diagnosis of fetal anomaly. The ability to cope with stressful events and regulate emotions across diverse situations may play a primary role in psychological wellbeing. This study aims to present coping strategies after disclosing a fetal anomaly to pregnant women.

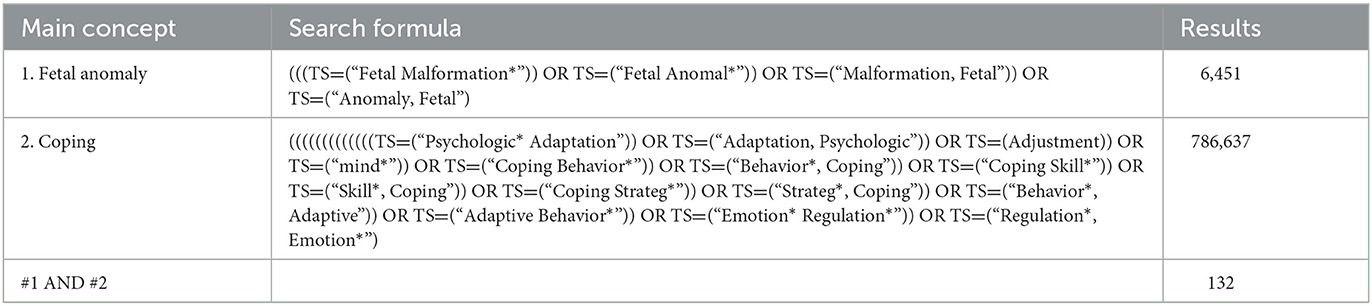

Methods: This is a scoping review based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR). Electronic databases, including Web of Science (WOS, BCI, KJD, MEDLINE, RSCI, SCIELO), CINAHL, and EBSCO PsycARTICLES, were used to search for primary studies from the inception of each database to 2021. The keywords were determined by existing literature and included: “fetal anomaly,” “fetal abnormality,” “fetal anomaly,” “fetal abnormality” AND “cope,” “coping,” “deal,” “manage,” “adapt*,” “emotion* regulate*,” with the use of Boolean operators AND/OR. A total of 16 articles were reviewed, followed by advancing scoping review methodology of Arksey and O'Malley's framework.

Results: In this review, we identified 52 coping strategies using five questionnaires in seven quantitative studies and one mixed-method study. The relationship between coping strategies and mental distress was explored. However, the results were inconsistent and incomparable. We synthesized four coping categories from qualitative studies and presented them in an intersection.

Conclusion: This scoping review identified the coping strategies of women with a diagnosis of a fetal anomaly during pregnancy. The relationship between coping strategies and mental distress was uncertain and needs more exploration. We considered an appropriate measurement should be necessary for the research of coping in women diagnosed with fetal anomaly pregnancy.

Introduction

Screening for fetal anomalies is part of prenatal care, which is recommended for all pregnant women worldwide (1). The diagnosis of fetal anomalies is occurring more frequently because of the increasing use of sophisticated obstetric technologies. The overall prevalence of fetal anomalies was 2.09% in a Cochrane review (2) and ~3.04% in China (3). This diagnosis is a major source of stress for women and their families, resulting in mental distress, such as grief, depression, and anxiety (4–11). While dealing with the grieving experience due to the abnormality, women concurrently manage other stressful events, such as decision-making on continuing or terminating the pregnancy (12–14). Research has indicated that their symptoms of grief were more serious than women with normal pregnancies, even amid the COVID-19 pandemic (15), and persisted for several years after being diagnosed with a fetal anomaly pregnancy (16, 17).

Coping is defined as constantly changing cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage (reduce, minimize, master, or tolerate) specific external and/or internal demands that are appraised as taxing or exceeding the resources of the person (18, 19). Generally, coping with stressful events plays a primary role in controlling the situation for reducing mental distress (20, 21). Coping plays an important role in the relationship between stress and mental health (22). Different coping strategies bring different mental health outcomes, such as self-distraction appearing to be associated with lower psychological distress and avoidant coping and denial associated with increased psychological distress (23). Lazarus and Folkman's stress and coping theory identified two processes, cognitive appraisal and coping, as critical mediators of stressful person–environment transactions (18, 19).

In studies of coping, researchers reported many kinds of coping strategies, and the instruments to evaluate coping strategies were inconsistent (24–26). On their path to analyzing categories and systems of coping, Skinner et al. identified approximately 400 coping techniques and approximately 100 schemes to classify coping (24). Among these categories, engagement vs. disengagement and primary control vs. secondary control were used in a multidimensional model to be higher-order coping categories (24, 27). Engagement responses are directed toward the stressor or one's reactions to the stressor and include approach responses; disengagement responses are oriented away from a stressor or one's reactions and include avoidance responses. Primary control refers to coping attempts that are directed toward influencing objective events or conditions; secondary control coping involves efforts to fit with or adapt to the environment (27, 28). Some other researchers also tried to present the structure of coping strategies more clearly using hierarchical models; for example, Trawalter et al. adapted a framework from cognitive appraisals to the coping behavior of interracial contact (29). Mara et al. used the intersection of two elements (personal empowerment vs. collective empowerment: disclosure vs. concealment), which resulted in four coping strategies (reactive, proactive, internalize, and externalize) (30). Furthermore, Ewert et al. showed the coping structure with a three-level pyramid; the first level was adaptive and maladaptive coping, the second level was problem-focused and emotion-focused coping, and the third level was individual coping strategies (31). However, articles presented a lack of gold standards for evaluating coping strategies (25, 26).

Situational factors, which refer to the objective features of the event, and the person's appraisal (primary and secondary appraisal) of the situation play as determinants of coping (18, 19, 32). The effectiveness of any coping strategy and its impact on wellbeing may vary from situation to situation (33, 34). Therefore, women will use different coping responses from other stressful events when diagnosed with fetal anomaly pregnancy. Their coping is a critical mediator between the event and their mental distress. Various methods were used to explore women's coping strategies in the situation of being diagnosed with fetal anomaly pregnancy, but relative reviews were underreported. A scoping review will be helpful for summarizing research findings, and identifying research gaps in the existing literature (35, 36), and supporting professional practices and new research on the subject.

Methods

Objectives

In this study, we are aiming to review the coping strategies when a woman is diagnosed with fetal anomaly pregnancy. This review formed two study questions based on the population, concept, and context (PCC) elements (37): (1) “What types of coping strategies have been reported when women are diagnosed with fetal anomaly pregnancy? and (2) what is the influence of coping strategies upon mental distress, including grief, depression, or anxiety, in this situation?” [SIC] We present the following article in accordance with the PRISMA-ScR reporting checklist.

Design

This is a scoping review including evidence from qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-method studies. Five steps of the advancing methodology of Arksey and O'Malley's framework (35, 36, 38) are used as follows: (1) identifying the research question, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) study selection and assessment, (4) charting the data, and (5) collating, summarizing, and reporting results.

Search methods

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Studies were included based on the following inclusion criteria: (1) Studies that reported on the coping strategies of women with a diagnosis of a fetal anomaly during pregnancy; (2) data were collected from the women with a diagnosis of a fetal anomaly during pregnancy, their partners, or their healthcare providers; and (3) primary studies published in English or Chinese from the inception of each database to 2021. Exclusion criteria included the following: (1) review articles and (2) other languages other than English and Chinese.

Search strategies and study selection

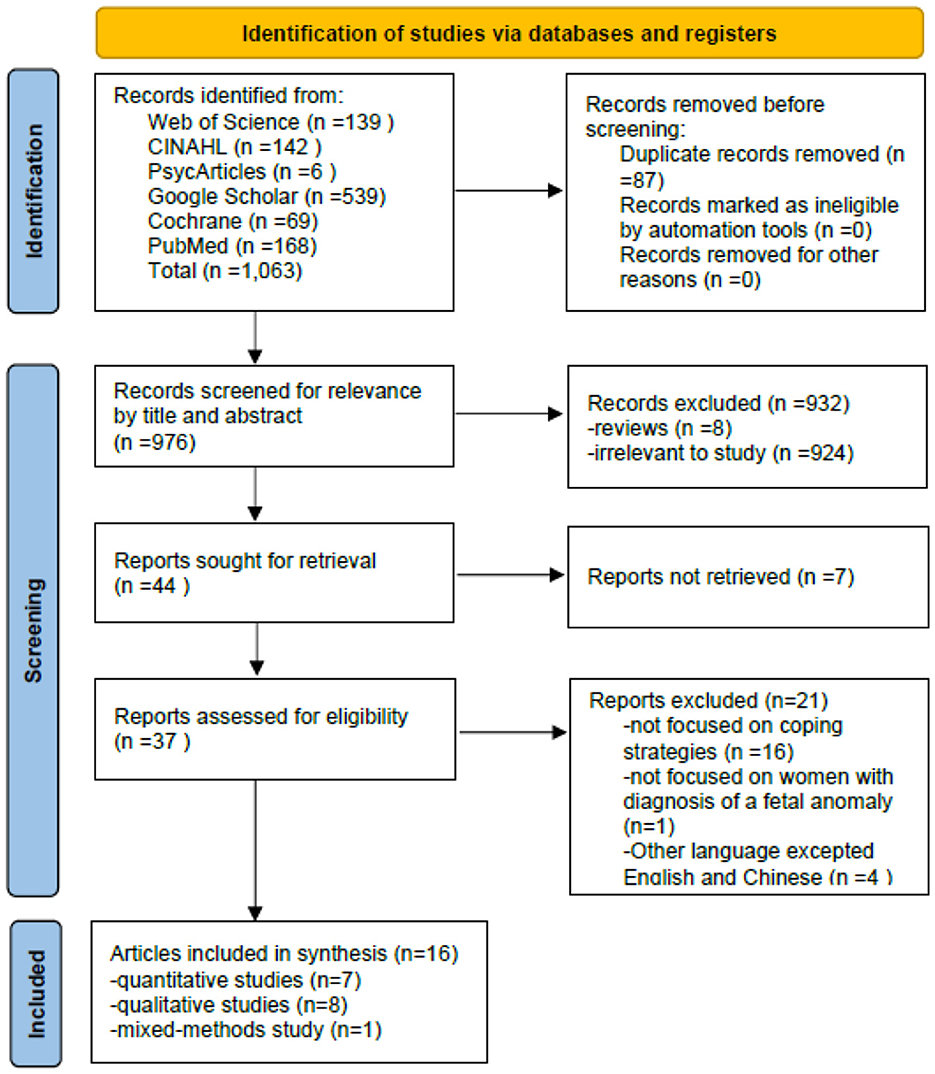

The following databases were used to search for primary studies: Web of Science (WOS, BCI, KJD, MEDLINE, RSCI, SCIELO), CINAHL and EBSCO, PsycARTICLES, PubMed, Google Scholar, and Cochrane. The initial literature search was performed in September 2020, and the search was updated in December 2020 and February 2023. The keywords were determined from existing literature and included: “fetal anomaly,” “fetal abnormality,” “fetal anomaly,” “fetal abnormality” AND “cope,” “coping,” “deal,” “manage,” “adapt*,” “emotion* regulate*,” with the use of Boolean operators AND/OR. See Table 1 for an example of search terms from one database and the yielded numbers. The screening process included four steps and is shown in Figure 1. First, all titles and abstracts retrieved were downloaded to the Endnote X9 library, and duplicate articles were removed. Second, articles were excluded based on titles and abstracts. Third, the full text of the article was reviewed to determine eligibility based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Finally, the reference lists of the included articles and related reviews were screened for potentially relevant articles. The searching and screening processes were conducted by two independent researchers, and disagreements were resolved by a third researcher.

Quality appraisal

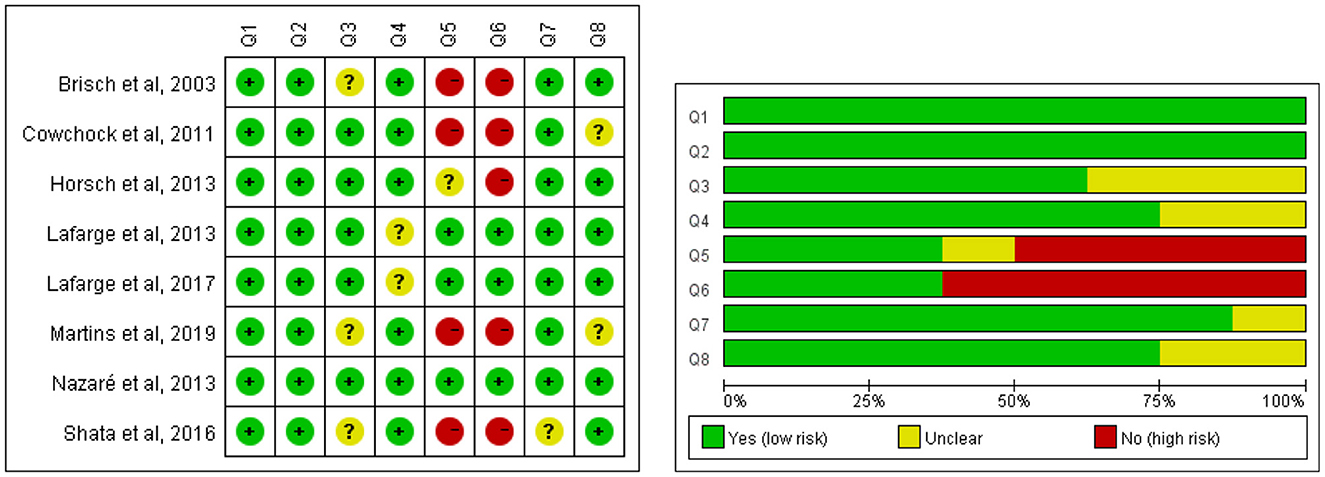

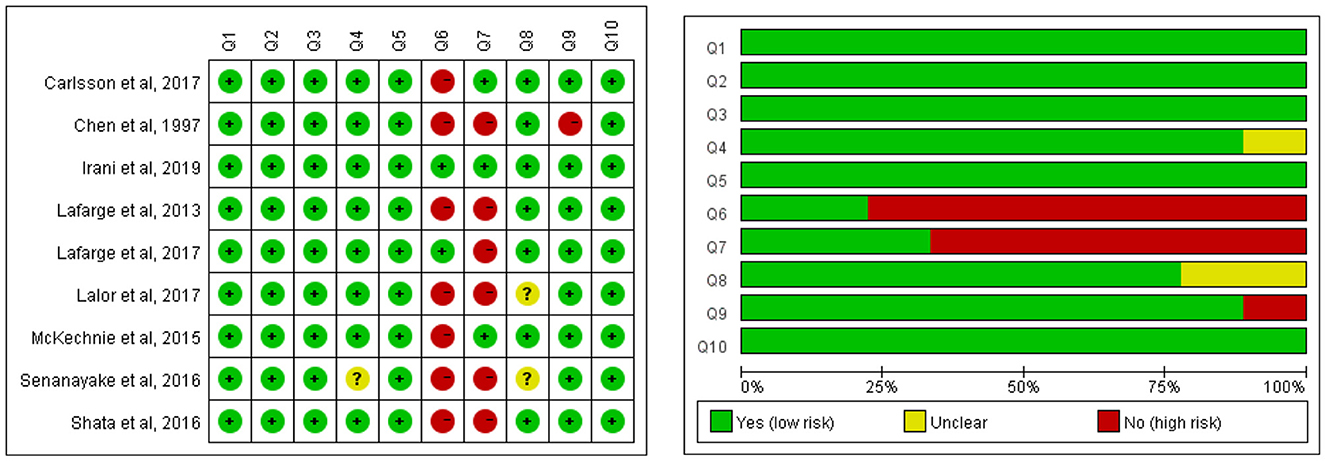

The quality of the included articles was assessed by two independent researchers using the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal checklist for analytical cross-sectional studies (Figure 2) and qualitative research (Figure 3). The mix-method study was separately appraised by both analytical cross-sectional studies and qualitative research checklists. Each entry was answered with yes, no, or unclear. As the review sought to explore the totality of evidence relating to coping strategies after being diagnosed with fetal anomaly pregnancy, no disqualifications were made on the quality evaluation process. The quality evaluating process only assisted in building a picture of the current study characteristic of the field.

Figure 2. Methodological quality of quantitative studies. Q1: Were the criteria for inclusion in the sample clearly defined? Q2: Were the study subjects and the setting described in detail? Q3: Was the exposure measured in a valid and reliable way? Q4: Were objective, standard criteria used for measurement of the condition? Q5: Were confounding factors identified? Q6: Were strategies to deal with confounding factors stated? Q7: Were the outcomes measured in a valid and reliable way? Q8: Was appropriate statistical analysis used?

Figure 3. Methodological quality of qualitative studies. Q1: Was there congruity between the stated philosophical perspective and the research methodology? Q2: Was there congruity between the research methodology and the research question or objectives? Q3: Was there congruity between the research methodology and the methods used to collect data? Q4: Was there congruity between the research methodology and the representation and analysis of data? Q5: Was there congruity between the research methodology and the interpretation of results? Q6: Was there a statement locating the researcher culturally or theoretically? Q7: Was the influence of the researcher on the research, and vice-versa, addressed? Q8: Were participants, and their voices, adequately represented? Q9: Was the research ethical according to current criteria or, for recent studies, and is there evidence of ethical approval by an appropriate body? Q10: Did the conclusions drawn in the research report flow from the analysis, or interpretation, of the data?

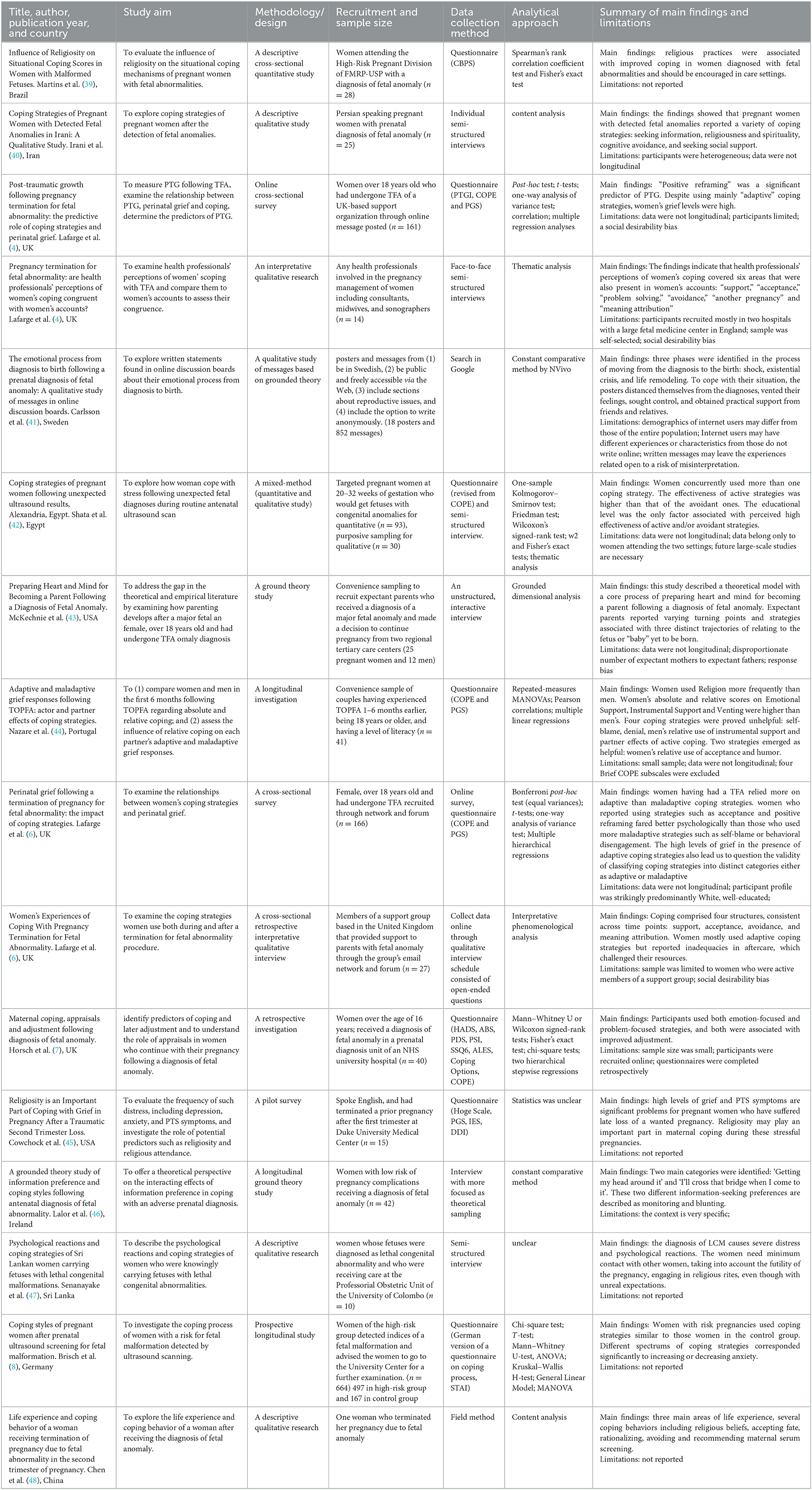

Data extraction

Data from each study were extracted using an Excel database (Table 2). Next, two reviewers read the articles carefully and then extracted the data. The extracted content included the title, author, year, country, aim, methodology/design, sample strategy and sample size, data collection method, analytical approach, and summary of main findings.

Table 2. Individual characteristics of the included studies (n = 16) on coping strategies of the women diagnosed with a fetal anomaly.

Synthesis

The meta-ethnographic approach was used for qualitative synthesis in which the themes of individual studies are contrasted and compared systematically (49, 50). Qualitative synthesis identifies congruence and convergence in concepts and themes across individual studies, leading to new insights through secondary analysis and reinterpretation. It can be broken down into the following two stages; (a) reciprocal and refutational synthesis and (b) line of argument synthesis (50). A line of argument synthesis is achieved by constant comparison of the concepts and developing a ‘grounded theory that puts the similarities and differences between the studies into interpretative order' (50). Constant comparison with previous literature and theoretical frameworks is necessary for expanding and exceeding the theoretical framework (51).

Results

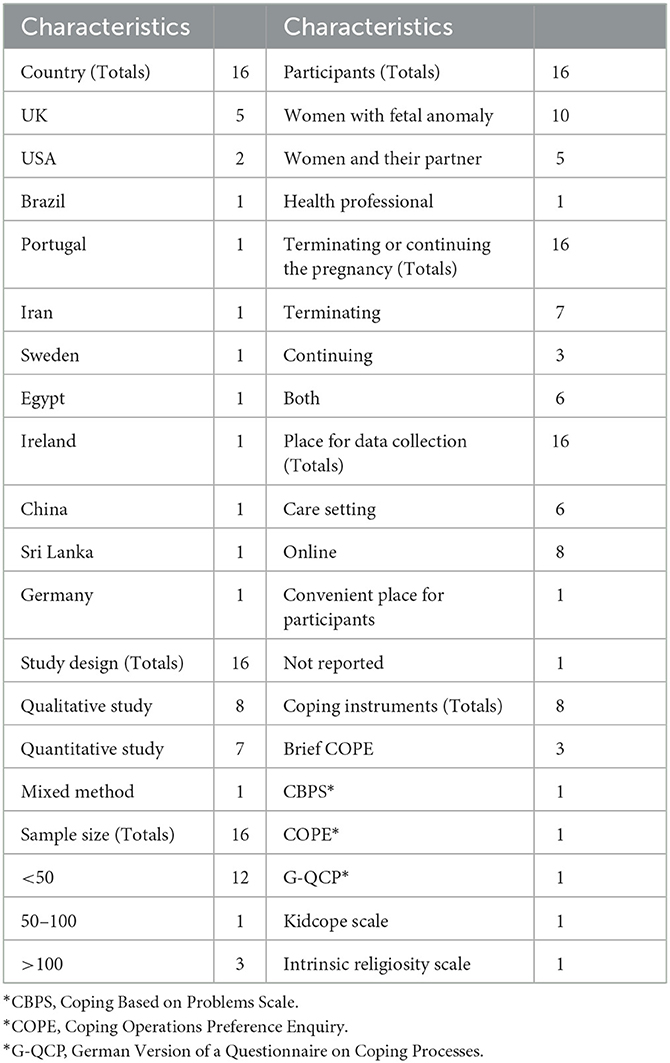

Overview of study characteristics

A flow diagram is used to present the results of the search process (Figure 1); a total of 1,063 studies were identified by searching six databases. Duplicate references were identified and removed (N = 87). After examining titles and abstracts, 932 full texts were further screened. Then, 28 studies were excluded for not being retrievable, not focused on our topic, or other languages, and 16 studies were identified as meeting our criteria and were included in this review. The characteristics of these studies are shown in Table 3. These 16 studies come from 11 countries. The participants are women, their partners, or health professionals. Six studies in all studies recruited participants who terminated and continued pregnancy, seven termination restrictions, and three restrictions continued. A place for data collection is a care setting, online, or a convenient place for participants. The content of the included studies examining the coping strategies of women diagnosed with fetal anomaly pregnancy is presented in Table 2. Qualitative studies (n = 8), quantitative studies (n = 7), and mixed-method studies (n = 1) are presented. The total number of participants in the studies was 1,215.

Quality appraisal: Quantitative studies

The quality assessment details of cross-sectional studies are presented in Figure 2. A total of five studies did not identify the confounding factors and state strategies to deal with confounding factors, which may cause confounding bias. A few studies did not present the validity and reliability of measurements clearly (participant, exposure, or outcome), potentially leading to measurement bias. Statistical methods were unclear in two studies, probably causing bias during analysis.

Quality appraisal: Qualitative studies

The quality assessment details of qualitative studies are presented in Figure 3. The main bias came for researchers because seven studies did not clarify the researcher's cultural and theoretical influence on the study, and six studies did not address the potential influence and relationship between the researcher and the study participants. The congruity between the research methodology and the representation and analysis of data was unclear in one study, and the representation of participants and their voices was unclear in two studies, which probably caused performance bias. One study did not report ethics approval.

Coping strategies in quantitative studies

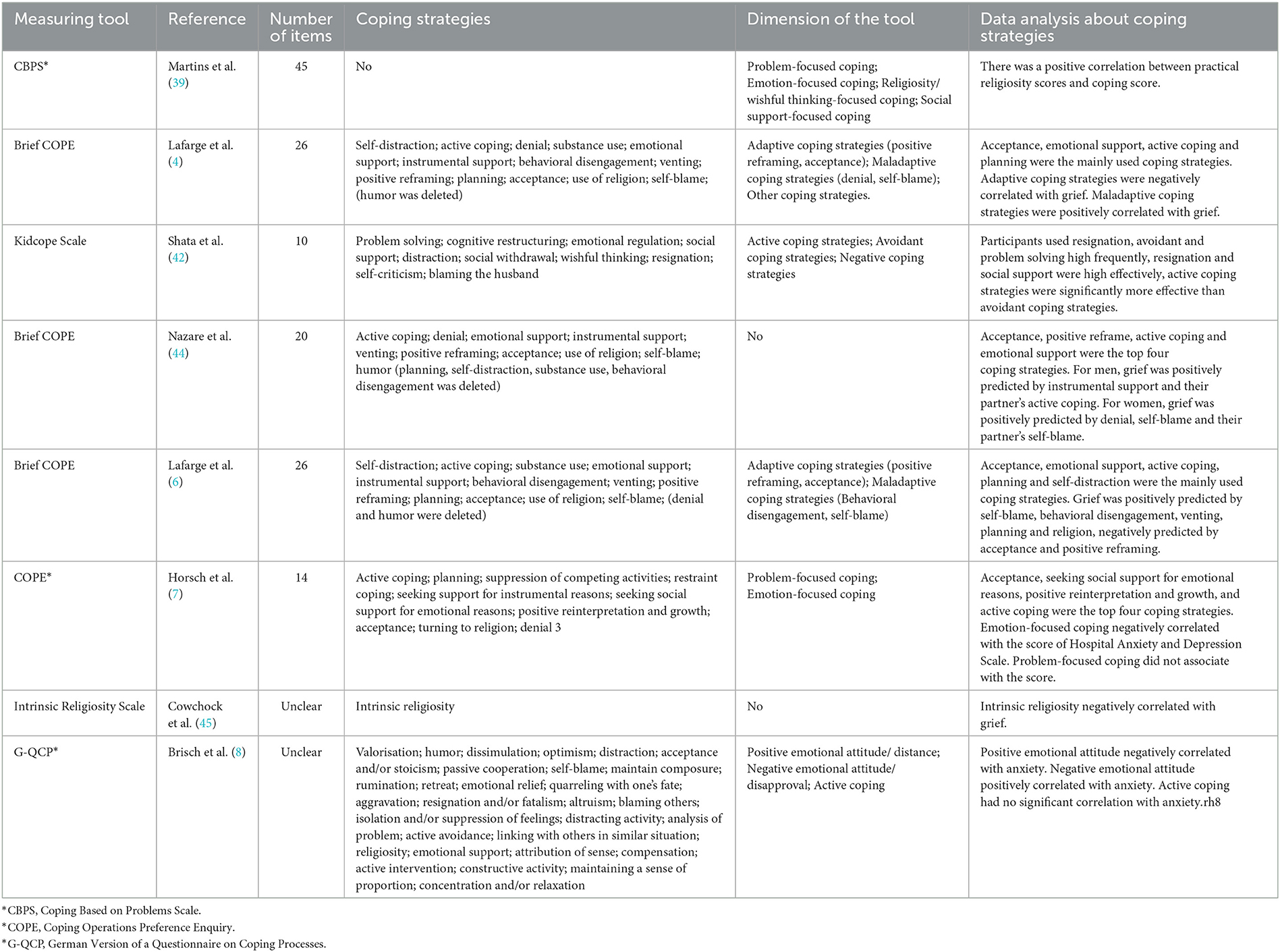

The measurement tools of the coping strategies

The details of coping strategies included in quantitative studies (n = 7) and the quantitative part of the mixed-method study (n = 1) are presented in Table 4. A total of five questionnaires (Brief COPE, CBPS, COPE, G-QCP, and the Kidcope Scale) were used to measure the coping strategies of women after being diagnosed with fetal anomaly pregnancy, and one questionnaire just measured intrinsic religiosity. There are 52 coping strategies in total after removing the duplicates. Acceptance, emotional support, active coping, planning, resignation, avoidant, problem-solving, positive reframe, self-distraction, positive reinterpretation, and growth were reported to be highly frequent coping strategies. However, two studies mainly focused on religiosity. The used dimension names include problem-focused coping, emotion-focused coping, religiosity/wishful thinking-focused coping, social support-focused coping, adaptive coping strategies, maladaptive coping strategies, active coping strategies, avoidant coping strategies, negative coping strategies, positive emotional attitude/distance, and negative emotional attitude/disapproval. Three studies used Brief COPE as their measurement tool, but different items were removed in each research. The other five questionnaires were separately used in five studies. Therefore, it is difficult to compare results with each other.

Table 4. Description of coping strategies included quantitative studies (n = 7) and the quantitative part of mixed-method study (n = 1).

The relationship between coping strategies and mental stress is explored

Notably, five out of eight quantitative studies explored the coping mechanisms of women with fetal anomalies by analyzing their relationships with mental distress, such as grief, depression, or anxiety (4–8). Three studies analyzed the relationship between the dimensions of coping and mental distress; the other two analyzed each strategy and mental distress. The variables, outcomes, or results of these studies are inconsistent with each other (see details in Table 4). In one study, acceptance was grouped into adaptive coping strategies and denial was grouped into maladaptive coping strategies, and these two dimensions had opposite effects on grief (4). Otherwise, in another study, both acceptance and denial were grouped into emotion-focused coping, which negatively correlated with the score on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (7). Although the same questionnaire was used in two studies and explored each coping strategy's effect on grief, the results were still inconsistent in addition to self-blame (5, 6).

Coping strategies in qualitative studies

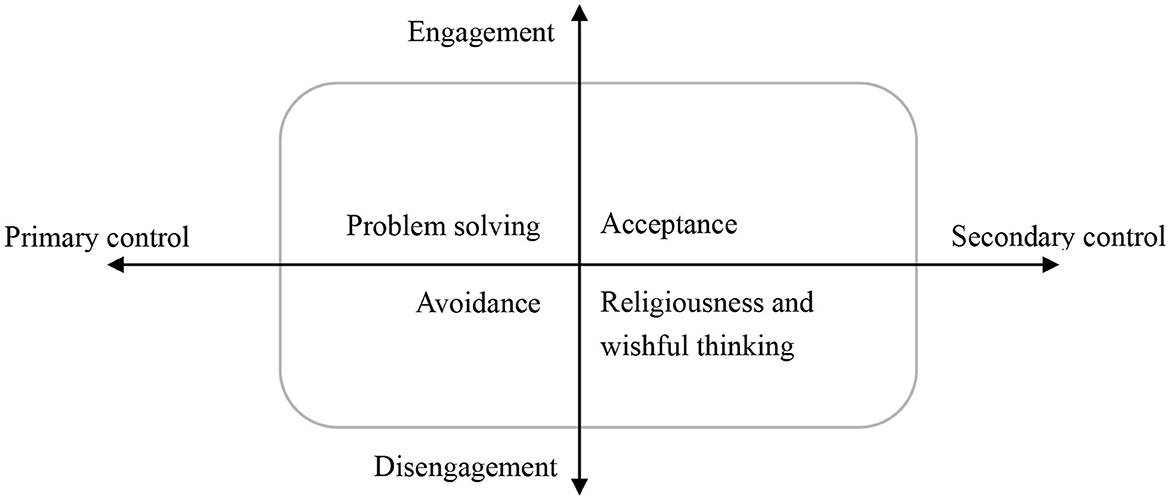

In these eight qualitative studies, women's coping strategies were the main topics of four studies (40, 46, 52, 53) and part topics of the other four studies (41, 43, 47, 48). The main topic of the mixed-method study was coping strategies, but qualitative research was part of it (42). We used a hierarchical model with two distinction elements (engagement vs. disengagement; primary control vs. secondary control) to present the coping strategies of women with a diagnosis of a fetal anomaly during pregnancy (Figure 4) (27, 28). Each of these elements formed an axis, and the two axes intersected (30); then, an intersection of these two elements resulted in four coping strategies (Figure 4): problem-solving (engagement and primary control coping), acceptance (engagement and secondary control coping), avoidance (disengagement and primary control coping), and religiousness and wishful thinking (disengagement and secondary control coping).

Engagement and primary control coping: problem-solving

This strategy was regarded as a coping strategy for women to have control over the situation (41, 52). Women tried to focus on the medical procedure for problem-solving, including asking for help from medical professionals about their baby's medical condition and development, being involved in healthcare decisions, and expressing individual requirements (41, 42, 52, 53). Seeking information and support was used frequently to control the situation. After the shock of diagnosis, many women expressed a significant need for detailed information (41). They needed the information to cope with the uncertainty, be actively involved in medical decisions, and continue the management of fetal wellbeing (46). They tried to find more information by searching on the internet, reading books, visiting different doctors, performing various diagnostic tests and sonography, and seeking peer experiences (40). Some women sought social support to decrease the high level of stress (40), including emotional support (40) and practical support (such as help with babysitting and chores) (41). Women sought not only individual-based support from partners, other family members, friends, and other women with the same experience (40) but also professional-based support (52, 53).

Engagement and secondary control coping: Acceptance

Acceptance was considered a coping strategy, including actively accepting the situation and acknowledging the baby (52, 53). In McKechnie et al. (43) study, some expectant parents chose to claim their child as their own. They said “It's your kid. You're the parent of that kid that has the birth defect. And it's just such a hard thing to just do……” Some others chose to continue the routine as if this was a normal pregnancy. They came to realize what they could or could not know about the diagnosis and accepted a conclusion about the diagnosis (43). In acceptance and commitment therapy, acceptance “involves the active and aware embrace of those private events occasioned by one's diagnosis without unnecessary attempts to change their frequency or form, especially when doing so would cause psychological harm” (54). Some women tried to embrace the diagnosis of fetal anomaly by freely expressing their feelings (41, 42). They expressed their thoughts and feeling to peers, families, friends, and health professionals. They said “With all that I have, I can't keep calm to avoid getting depressed. I try to talk with all people around me” (42).

Disengagement and primary control coping: avoidance

Avoiding the situation was described as a coping strategy of women with a diagnosis of a fetal anomaly during pregnancy nearly in all qualitative studies (40, 41, 43, 46, 48, 52, 53, 55) and supported by a mixed-method study (42). Some women were reluctant to receive negative information (40, 41, 46, 52). Some women distanced themselves from pregnancy, fetuses, other pregnant women, and young babies (43, 48, 53). Some recalled drinking heavily (53). Others focused their attention elsewhere (41), such as another pregnancy (52), healthy children (47), getting back to a routine, and trying to function as normally as possible (53). They avoided social situations because people treated pregnant women like public property, assuming a healthy baby (40, 55).

Disengagement and secondary control coping: religiousness and wishful thinking

Religiousness and wishful thinking coping mean believing in God, divine providence, and reliance on God's power. It contained three subcategories: praying, acceptance of destiny, and reliance on faith (40). Women hoped for a miracle to save their expected child (41). They had wishful thinking and said, “we chose to continue the pregnancy, and we hoped that it wouldn't deteriorate.” (42) They engaged in religious rites and believed in miraculous powers, hoping religious rites would beat the anomaly or prove the diagnosis wrong (47, 48, 52). The results showed that the belief in God had roots in the mother's mind so they understood it as divine providence and an opportunity to be examined in difficulties. Some women resigned to divine providence (48), “I told my husband that God handled everything….” They believed that if God gave them a problem, he also gave them the ability to tolerate it (40). The resignation was described as accepting their situation and making peace with their fate (42).

Discussion

This scoping review presented the results of 16 studies to describe the coping strategies of women with a diagnosis of a fetal anomaly during pregnancy. A total of 52 coping strategies were collected in the quantitative studies using five questionnaires. The results of the main coping strategies of women or the correlation between coping strategy and mental distress were inconsistent and incomparable. All the coping strategies in qualitative studies were synthesized based on a meta-ethnographic approach. After constantly comparing with previous literature and theoretical frameworks, an intersection of two elements (engagement vs. disengagement and primary control vs. secondary control) was presented. This intersection classified the coping strategies into four categories: problem-solving, acceptance, avoidance, religiousness, and wishful thinking.

To our knowledge, this is the first review of the coping strategies of women with a diagnosis of a fetal anomaly during pregnancy. We identified five coping questionnaires used in seven quantitative studies in this review. Brief COPE was used in two different studies, but the items were different. Therefore, the results of coping strategies of women with a diagnosis of a fetal anomaly during pregnancy were inconsistent and incomparable. There were different measurements, dimensions, or items even when using the same questionnaire. Some studies failed to report the validity and reliability of the questionnaire (8, 39, 42). Some others categorized coping strategies into dimensions without factors analysis reporting (4, 7). No gold standard for measuring coping strategies of women with a diagnosis of a fetal anomaly during pregnancy has been established. Similar results were reported in reviews of other populations' coping, like caregivers of children with special illnesses (25, 26). The study of coping strategies attracted the wide attention of researchers because the ability to cope with stressful events played a primary role in reducing the risk for mental distress (56). More than 400 coping strategies were identified in one review across childhood, adolescence, and adulthood (24); it also reported that little consistency appeared across different measures and studies (28). Furthermore, all five questionnaires in this review were used to investigate coping strategies under general stress, and not used for women with a diagnosis of a fetal anomaly during pregnancy. Coping strategies in this special situation should be different from other situations (33). Therefore, we considered an appropriate measurement should be necessary for the research of coping in women diagnosed with fetal anomaly pregnancy.

After analyzing the results of qualitative studies, we classified the coping strategies with two distinct elements. In previous studies, authors also tried to categorize coping strategies into problem-focused and emotion-focused (39), adaptive and maladaptive (6), and positive and negative (8), but each of them cannot cover all the coping strategies that were being used. One study reported three coping categories: active, avoidant, and negative (42). However, it is confusing how avoidant and social withdrawal causes more negative outcomes in these women (57). Another study used problem-focused and emotion-focused to categorize all coping strategies (7). However, both acceptance and denial, whose effects were opposite in other studies, were in the same dimension. The results were consistent with the previous review, which recommended hierarchical systems for coping categories because all coping methods were multidimensional (24). Several hierarchical models of coping were reported in other populations (29–31). In this review, after synthesizing and constantly comparing, we used the intersection of engagement vs. disengagement and primary control vs. secondary control to distinguish coping's direction (toward or away from stressors) and action (influences objective events or adapt oneself to the events) features for women with fetal anomaly during pregnancy diagnosis. It should be helpful for researchers to understand their coping strategies more clearly.

Limitations

There are several limitations in this review. First, to comprehensively explore the current research on the coping strategies of women after being diagnosed with fetal anomaly pregnancy, we did not exclude the studies without reporting reliability and validity of the coping questionnaire, confidence intervals, and odds ratio of regression analysis. Thus, caution should be used when interpreting the results of these surveys and this review. We included all studies that recruited women continuing or terminating their fetal anomaly pregnancy and their partners or healthcare providers. Therefore, the results of this review should be affirmed in future research for pregnant women, their partners, and healthcare providers. In addition, different groups of study participants might skew the accuracy of this review. Finally, only English and Chinese articles were included; however, we did not limit the language during article searching. Therefore, the search terminology or terms should be revised to recover relative studies in future.

Implications of the findings for clinical practice

The findings of this review identified several implications for clinical practices. All the participants, including women, family caregivers, and healthcare providers, can understand the coping strategies used by women with fetal anomalies from this review. Although coping strategies and the effects are waiting to be explored and verified, this should provide information for healthcare providers to offer appropriate support (58). A better understanding of the coping strategies would be a foundation for improving the health of women with a fetal anomaly.

Implications of the findings for future research

This review pointed out several significant studies on coping strategies of women with a diagnosis of a fetal anomaly during pregnancy: (1) establishing a special measurement (questionnaire or scale) to evaluate the coping strategies and analyze the correlation with mental stress; (2) using exploring or confirming factors analysis to demonstrate the coping strategies and their factors; (3) investigating the influence factors of coping strategies; and (4) exploring effective interventions for coping strategies that would decrease the incidence of mental stress.

Conclusion

This scoping review identified the coping strategies of women with a diagnosis of a fetal anomaly during pregnancy from quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-method studies. Coping strategies included acceptance, emotional support, active coping, planning, resignation, avoidance, problem-solving, positive reframe, self-distraction, positive reinterpretation, and growth, which were reported to be used highly frequently. However, the results of quantitative studies were inconsistent and incomparable. Based on the synthesis of the qualitative results, the coping strategies have been classified into four categories shown in an intersection: problem-solving (engagement and primary control coping), acceptance (engagement and secondary control coping), avoidance (disengagement and primary control coping), and religiousness and wishful thinking (disengagement and secondary control coping). Establishing a valid and reliable measurement would be necessary for future studies on the coping of women with a diagnosis of fetal anomaly pregnancy. The result of this synthesis provides a clear framework for future research.

Author contributions

HH and CQ: study design. TZ and YL: data collection. TZ, HP, and JX: data analysis. W-TC and QH: study supervision. TZ and W-TC: manuscript writing. HH, CQ, and TZ: critical revisions for important intellectual content. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (72074225), the Philosophy and Social Science Foundation of Hunan Province (19YBA351), and the Key R&D plan of Hunan Province (2020SK2089 and 2021SK2024).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Theresah Owusua for her valuable contributions to editing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1055562/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Arulkumaran S, Ledger W, Denny L, Doumouchtsis S, editors. Oxford Textbook of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. Oxford: Oxford University Press (2020). doi: 10.1093/med/9780198766360.001.0001

2. Whitworth ML. Bricker, C. Mullan. Ultrasound for fetal assessment in early pregnancy. Cochrane Database Sys Rev. (2015) 7:7058. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007058.pub3

3. Zhang X, Chen L, Wang X, Wang X, Jia M, Ni S, et al. Changes in maternal age and prevalence of congenital anomalies during the enactment of China's universal two-child policy (2013–2017) in Zhejiang Province. China: An observational study. PLoS Med. (2020) 17:3047. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003047

4. Lafarge CK, Mitchell P. Fox Posttraumatic growth following pregnancy termination for fetal abnormality: the predictive role of coping strategies and perinatal grief. Anxiety Stress Coping. (2017) 30:536–50. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2016.1278433

5. Nazaré B, Fonseca A, Canavarro MC. Adaptive and maladaptive grief responses following TOPFA: actor and partner effects of coping strategies. J. Reprod Infant Psychol. (2013) 31:257–73. doi: 10.1080/02646838.2013.806789

6. Lafarge, CK, Mitchell P. Fox. Perinatal grief following a termination of pregnancy for foetal abnormality: the impact of coping strategies. Prenatal Diag. (2013) 33:1173–82. doi: 10.1002/pd.4218

7. Horsch A, Brooks C, Fletcher H. Maternal coping, appraisals and adjustment following diagnosis of fetal anomaly. Prenatal Diagnosis. (2013) 33:1137–45. doi: 10.1002/pd.4207

8. Brisch KH, Munz D, Bemmerer-Mayer K, Terinde R, Kreienberg R, Kächele H. Coping styles of pregnant women after prenatal ultrasound screening for fetal malformation. J Psychosomat Res. (2003) 55:91–7. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00572-X

9. Qin C, Chen WT, Deng Y, Li Y, Mi C, Sun L, et al. Cognition, emotion, behaviour in women undergoing pregnancy termination for foetal anomaly: a grounded theory analysis. Midwifery. (2019) 68:84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2018.10.006

10. Kaasen A, Helbig A, Malt UF, Næs T, Skari H, Haugen G. Maternal psychological responses during pregnancy after ultrasonographic detection of structural fetal anomalies: A prospective longitudinal observational study. PLoS ONE. (2017) 12:3. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0174412

11. Carlsson T, Bergman G, Karlsson A-M, Wadensten B, Mattsson E. Experiences of termination of pregnancy for a fetal anomaly: a qualitative study of virtual community messages. Midwifery. (2016) 41:54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2016.08.001

12. Hodgson J, Pitt P, Metcalfe S, Halliday J, Menezes M, Fisher J, et al. Experiences of prenatal diagnosis and decision-making about termination of pregnancy: a qualitative study Australian & New Zealand. J Obstet Gynaecol. (2016) 56:605–13. doi: 10.1111/ajo.12501

13. Fleming V, Iljuschin I, Pehlke-Milde J, Maurer F, Parpan F. Dying at life's beginning: Experiences of parents and health professionals in Switzerland when an ‘in utero' diagnosis incompatible with life is made. Midwifery. (2016) 34:23–9. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2016.01.014

14. Maguire M, Light A, Kuppermann M, Dalton VK, Steinauer JE, Kerns JL. Grief after second-trimester termination for fetal anomaly: a qualitative study. Contraception. (2015) 91:234–9. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.11.015

15. Safi-Keykaleh M, Aliakbari F, Safarpour H, Safari M, Tahernejad A, Sheikhbardsiri H, et al. Prevalence of postpartum depression in women amid the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. (2022) 157:240–7. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.14129

16. Kersting A, Dorsch M, Kreulich C, Reutemann M, Ohrmann P, Baez E, et al. Trauma and grief 2-7 years after termination of pregnancy because of fetal anomalies—A pilot study. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. (2005) 26:9–14. doi: 10.1080/01443610400022967

17. Korenromp MJ, Christiaens GC, Van den Bout J, Mulder EJ, Hunfeld JA, Bilardo CM, et al. Long-term psychological consequences of pregnancy termination for fetal abnormality: a cross-sectional study. Prenatal Diag. (2005) 25:253–60. doi: 10.1002/pd.1127

18. Folkman S, Lazarus RS, Gruen RJ, DeLongis A. Appraisal, coping, health status, psychological symptoms. J Personal Soc Psychol. (1986) 50:571–9. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.50.3.571

19. Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress Appraisal and Coping. Springer Publishing Company, Inc. (1984) 460.

20. Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Skinner EA. The development of coping: Implications for psychopathology and resilience. In:D. Cicchetti, (, Ed.), Developmental Psychopathology. (2016): Oxford, England: Wiley. doi: 10.1002/9781119125556.devpsy410

21. Hagger MS, Koch S, Chatzisarantis NLD, Orbell S. The common sense model of self-regulation: Meta-analysis and test of a process model. Psychol Bull. (2017) 143:1117–54. doi: 10.1037/bul0000118

22. Groth N, Schnyder N, Kaess M, Markovic A, Rietschel L, Moser S, et al. Coping as a mediator between locus of control, competence beliefs, mental health: a systematic review and structural equation modelling meta-analysis. Behav Res Therapy. (2019) 121:16. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2019.103442

23. Rückholdt M, Tofler GH, Randall S, Buckley T. Coping by family members of critically ill hospitalised patients: an integrative review. Int J Nurs Stud. (2019) 97:40–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.04.016

24. Skinner EA, Edge K, Altman J, Sherwood H. Searching for the structure of coping: a review and critique of category systems for classifying ways of coping. Psychol Bull. (2003) 129:216–69. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.216

25. Craig F, Savino R, Fanizza I, Lucarelli E, Russo L, Trabacca A. A systematic review of coping strategies in parents of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Res Develop Disabil. (2020) 98:13. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2020.103571

26. Fairfax A, Brehaut J, Colman I, Sikora L, Kazakova A, Chakraborty P, et al. A systematic review of the association between coping strategies and quality of life among caregivers of children with chronic illness and/or disability. Bmc Pediatrics. (2019) 19:16. doi: 10.1186/s12887-019-1587-3

27. Connor-Smith JK, Compas BE, Wadsworth ME, Thomsen AH, Saltzman H. Responses to stress in adolescence: measurement of coping and involuntary stress responses. J Consult Clin Psychol. (2000) 68:976–92. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.68.6.976

28. Compas BE, Connor-Smith JK, Saltzman H, Thomsen AH, Wadsworth ME. Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: Problems, progress, potential in theory and research. Psychol Bullet. (2001) 127:87–127. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.1.87

29. Trawalter S, Richeson JA, Shelton JN. Predicting behavior during interracial interactions: a stress and coping approach. Personal SocPsychol Rev. (2009) 13:243–68. doi: 10.1177/1088868309345850

30. Mara LC, Ginieis M, Brunet-Icart I. Strategies for coping with LGBT discrimination at work: a systematic literature review. Sexual Res Soc Policy. (2021) 18:339–54. doi: 10.1007/s13178-020-00462-w

31. Ewert C, Vater A, Schröder-Abé M. Self-compassion and coping: a meta-analysis. Mindfulness. (2021) 12:1063–77. doi: 10.1007/s12671-020-01563-8

32. Terry DJ. Determinants of coping: the role of stable and situational factors. J Pers Soc Psychol. (1994) 66:895–910. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.66.5.895

33. DeLongis A, Holtzman S. Coping in context: the role of stress, social support, personality in coping. J Pers. (2005) 73:1633–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00361.x

34. Divdar Z, Foroughameri G, Farokhzadian J, Sheikhbardsiri H. Psychosocial needs of the families with hospitalized organ transplant patients in an educational hospital in Iran. Ther Apher Dial. (2020) 24:178–83. doi: 10.1111/1744-9987.13425

35. Daudt HMLC, van Mossel SJ, Scott. Enhancing the scoping study methodology: a large, inter-professional team's experience with Arksey and O'Malley's framework. Bmc Med Res Methodol. (2013) 13:48. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-48

36. Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. (2005) 8:19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616

37. Peters MD, Godfrey CM, McInerney P, Soares CB, Khalil H, Parker D. The Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers' Manual 2015: Methodology for JBI Scoping Reviews. (2016).

38. Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. (2010) 5:69. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

39. Martins PH, Duarte IPL, Leite CRVS, Cavalli RC, Marcolin AC, Duarte G. Influence of religiosity on situational coping scores in women with malformed fetuses. J Relig Health. (2019):13. doi: 10.1007/s10943-019-00934-3

40. Irani M, Khadivzadeh T, Asghari-Nekah SM, Ebrahimipour H. Coping strategies of pregnant women with detected fetal anomalies in Iran: a qualitative study. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. (2019) 24:227–33. doi: 10.4103/ijnmr.IJNMR_97_18

41. Carlsson TV, Starke E. Mattsson. The emotional process from diagnosis to birth following a prenatal diagnosis of fetal anomaly: a qualitative study of messages in online discussion boards. Midwifery. (2017) 48:53–9. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2017.02.010x

42. Shata, Z. Abdullah NHM, Nossier SA. Coping strategies of pregnant women following unexpected ultrasound results, Alexandria, Egypt. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. (2016) 91:65–72. doi: 10.1097/01.EPX.0000482538.95764.4b

43. McKechnie A, Pridham CK, Tluczek A. Preparing heart and mind for becoming a parent following a diagnosis of fetal anomaly. Qual Health Res. (2015) 25:1182–98. doi: 10.1177/1049732314553852

44. Nazaré B Fonseca A and Canavarro MC. Adaptive and maladaptive grief responses following TOPFA: actor and partner effects of coping strategies. J Reprod Infant Psychol. (2013) 31:257–73.

45. Cowchock FS Ellestad SE Meador KG Koenig HG Hooten EG and Swamy GK. Religiosity is an important part of coping with grief in pregnancy after a traumatic second trimester loss. J Relig Health. (2011) 50:901–10. doi: 10.1007/s10943-011-9528-y

46. Lalor JG, Begley CM, Galavan E. A grounded theory study of information preference and coping styles following antenatal diagnosis of foetal abnormality. J Adv Nurs. (2008) 64:185–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04778.x

47. Senanayake H, de Silva D, Premaratne S, Kulatunge M. Psychological reactions and coping strategies of Sri Lankan women carrying fetuses with lethal congenital malformations. Ceylon Med J. (2006) 51:14–7. doi: 10.4038/cmj.v51i1.1370

48. Chen SL. Life experience and coping behavior of a woman receiving termination of pregnancy due to fetal abnormality in the second trimester of pregnancy. J Nurs. (1997) 44:43–53.

49. Campbell R, Pound P, Pope C, Britten N, Pill R, Morgan M, et al. Evaluating meta-ethnography: a synthesis of qualitative research on lay experiences of diabetes and diabetes care. Soc Sci Med. (2003) 56:671–84. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00064-3

50. Sattar R, Lawton R, Panagioti M, Johnson J. Meta-ethnography in healthcare research: a guide to using a meta-ethnographic approach for literature synthesis. Bmc Health Serv Res. (2021) 21:6049. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-06049-w

51. Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. London: SAGE Publication Inc. (2006).

52. Lafarge C, Mitchell K, Breeze ACG, Fox P. Pregnancy termination for fetal abnormality: are health professionals' perceptions of women's coping congruent with women's accounts? BMC Preg Childbirth. (2017) 17:1238. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1238-3

53. Lafarge C, Mitchell K, Fox P. Women's experiences of coping with pregnancy termination for fetal abnormality. Qual Health Res. (2013) 23:924–36. doi: 10.1177/1049732313484198

54. Hayes SC, Luoma JB, Bond FW, Masuda A, Lillis J. Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes and outcomes. Behav Res Therapy. (2006) 44:1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.06.006

55. Smith Sd, Dietsch VE, Bonner A. Pregnancy as public property: the experience of couples following diagnosis of a foetal anomaly. Women Birth. (2013) 26:76–81. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2012.05.003

56. Compas BE, Jaser SS, Bettis AH, Watson KH, Gruhn MA, Dunbar JP, et al. Coping, emotion regulation, psychopathology in childhood and adolescence: a meta-analysis and narrative review. Psychol Bull. (2017) 143:939–91. doi: 10.1037/bul0000110

57. Nelson L, Jorgensen NA, Clifford BN. Shy and still struggling: Examining the relations between subtypes of social withdrawal and well-being in the 30's. Soc Develop. (2021) 30:575–91. doi: 10.1111/sode.12486

Keywords: fetal anomaly, mental distress, scoping review, coping strategies, women's health

Citation: Zhang T, Chen W-T, He Q, Li Y, Peng H, Xie J, Hu H and Qin C (2023) Coping strategies following the diagnosis of a fetal anomaly: A scoping review. Front. Public Health 11:1055562. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1055562

Received: 28 September 2022; Accepted: 07 March 2023;

Published: 06 April 2023.

Edited by:

Wulf Rössler, Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin, GermanyReviewed by:

Hojjat Farahmandnia, Kerman University of Medical Sciences, IranQiong Zheng, Zhejiang University, China

Copyright © 2023 Zhang, Chen, He, Li, Peng, Xie, Hu and Qin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chunxiang Qin, Q2h1bnhpYW5ncWluQGNzdS5lZHUuY24=

Tingting Zhang1,2

Tingting Zhang1,2 Wei-Ti Chen

Wei-Ti Chen Qingnan He

Qingnan He Chunxiang Qin

Chunxiang Qin