- 1JC School of Public Health and Primary Care, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong SAR, China

- 2Centre for Health Systems and Policy Research, JC School of Public Health and Primary Care, Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Background: Persistent inequalities in maternity care experience and outcomes exist globally for ethnic minority (EM) and migrant women. Despite the fact that this is an important research area, no prior study has been done in Hong Kong (HK) to examine maternity care experience of EM women.

Objectives: To investigate maternity care experience of Pakistani EM women (both local born and immigrants) during pregnancy, birth and after birth in hospital in HK. An evaluation of their satisfaction and factors predicting satisfaction with care during the three phases of maternity care was included in the study.

Methods: A cross sectional survey was conducted among Pakistani EM women who had given birth in HK in last 3 years, using a structured questionnaire by a bilingual interviewer, from April to May 2020. Counts and percentages were used to describe all categorical variables. Association between predictor variables and overall satisfaction was assessed by bivariate analysis and multiple logistic regression.

Results: One hundred and twenty questionnaires were completed. Almost 60 percent of the women were very satisfied with the overall care. More than half of the women described the care they received as kind, respectful and well communicated. After adjusting for age and parity, HK born Pakistani women expressed relatively less satisfaction with care, especially during pregnancy and labor and birth, as compared with Pakistan born women. Women with conversational or fluent English-speaking ability also felt comparatively less satisfied particularly from intrapartum and postnatal care in hospital. Education level had a negative association with satisfaction with care during pregnancy.

Conclusions: Maternity care providers should take into account the diversity of EM women population in HK. Our findings suggest that effective communication and care that can meet individual needs, expectations, and values is imperative to improve experience and quality of maternity care for EM women in HK.

1. Introduction

Maternity care, which is the healthcare received throughout pregnancy, during labor and childbirth and up to 6 weeks after childbirth, is of vital significance for maternal and child health. As such, policies have been implemented worldwide to ensure provision of equitable good quality maternity care to every pregnant woman and child. Such efforts incorporated the agenda of the United Nations Millennium Development Goals 4 and 5 (MDG, 2000–2015) and later the Sustainable Development Goal 3 (SDG, 2016–2030) (1, 2). In articulation with this, the World Health Organization (WHO) also formulated the new Global Strategy for Women's, Children's and Adolescents' Health (2016–2030) for the SDG era in conjunction with the global community (3).

Despite these efforts, persistent inequalities in maternity care experience and outcomes exist globally, particularly for ethnic minority and migrant women (4–6). These women tend to have higher susceptibility to anxiety and depression as compared to majority and native women (7, 8). Moreover, there is potentially increased risk of prematurity, low birth weight, increased maternal and infant morbidity and mortality (9, 10). Previous research identified several factors shaping these inequalities, including communication gap and lack of information due to language and cultural differences, structural barriers, stereotyping, discrimination and social exclusion (11, 12). Other factors included socio-economic status, poverty, gender inequalities and living in highly deprived areas (10, 12).

While branding itself as an international and inclusive city, Hong Kong holds a hegemonic Chinese culture where discrimination and marginalization of ethnic and migrant communities are widespread (13). Despite their deep-rooted presence in the city since its British colonial times, South Asians in general, and the Pakistani community in particular, is one of the most marginalized EM population in HK in terms of economic, social and educational levels (14). Such marginalization is also reflected in the health sector where they are exposed to higher health risks yet poorer access to healthcare services (15, 16); women in particular felt disengaged with the HK healthcare system (17).

Such marginality is likely to have detrimental effects on maternity care experience of Pakistani EM women in HK. Research conducted in Western countries has in fact documented adverse perinatal outcomes and poor maternity care experience of Pakistani EM women. A study from the United Kingdom (UK) for instance investigated increased perinatal mortality in Pakistani EM women and found that they had more risk factors, including low birth weight, diabetes, gestational diabetes, less BMI (<18 kg/m2), high parity and delayed bookings (>12 weeks) (18). Another UK study indicated that very few Pakistani mothers took pre-conception folic acid as they were less aware of the role of folic acid in congenital anomalies prevention (19). Low utilization of pain relief during birth was more common among Pakistani women, due to low education, less native language speaking ability and discrepancies in information availability. As a result, these women felt unsupported and dissatisfied with the maternity care they received (20–22). Conversely, Pakistani women with higher education were highly confident, well supported and informed appropriately (20).

Although HK has one of the lowest maternal mortality and infant mortality rate in the world (23), yet these indicators alone are insufficient in measuring quality care. WHO maternal and new-born quality care framework emphasized on experience of care as a key domain along with clinical care provision and availability of human and physical resources (24). Women satisfaction with care is a quality indicator to measure experience of care that should be evaluated for identifying areas for action to provide good quality maternity care (25). The objective of this study is to investigate maternity care experience of Pakistani EM women (both local born and immigrants) during pregnancy, birth and after birth in hospital in HK. An evaluation of their satisfaction and factors predicting satisfaction with care during the three phases of maternity care was also included in the study.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design, setting, and period

A cross-sectional study was conducted in HK from April to May 2020. Due to the social distancing measures during COVID-19, the survey was done on phone through WhatsApp video call. Ethics approval was obtained from the Survey and Behavioral Research Ethics Committee of the University (SBRE-19-521).

2.2. Populations and eligibility

All women living in HK, aged 18 and above, self-identified themselves as Pakistani and had given birth to at least one child in HK in the past 3 years, were included as the target population of the study. Women whose baby had died were excluded.

2.3. Sample size determination and sampling procedures

Purposive and snowball sampling was employed to recruit the eligible participants. The participants were reached through local Pakistani WhatsApp groups, social networks, non-governmental organizations working for ethnic minorities and community workers. The purpose and procedure of the study was explained to them and those who agreed to join were contacted to set the schedule for the interview.

Sample size was estimated by assuming 50% women satisfaction with maternity care services and 95% confidence interval with 7% error of margin. It was calculated by the equation (26):

Where α (Probability of type 1 error) = 0.05, p (Prevalence proportion) = 0.5, DEFF (Effect Size) = 1, d (Absolute precision) = 0.07, N (Sample size) = 196. We planned to interview 200 Pakistani women.

2.4. Data collection tools and procedures

Data was collected through a structured, interviewer administered paper-based questionnaire, adopted from the Survey of Bangladeshi women's experience of maternity services (SBWEMS) (27). After obtaining the informed consent, the participants were interviewed to fill the questionnaire on phone through WhatsApp video call at the prescheduled date and time by a bilingual interviewer. The interview was conducted in English or Urdu depending upon participant's preference. On an average the interview lasted for 45–60 min.

2.5. Outcome variables and measurements

The primary outcome variable was women's overall satisfaction with care in each of the three phases of pregnancy. For overall satisfaction participants were asked “Thinking back now, how satisfied are you, overall, with the care you received during your pregnancy, labor and delivery and after birth (in separate questions)?” Responses were recorded on a 4 point Likert scale: very satisfied, somewhat satisfied, somewhat dissatisfied and very dissatisfied. For statistical analysis, the answers were dichotomized into “high satisfaction (Very satisfied)” and “less satisfaction (somewhat satisfied, somewhat dissatisfied, and very dissatisfied)”. This was done firstly because not many women opted for the somewhat dissatisfied or very dissatisfied categories. Secondly from previous research we found that a rating of “very satisfied” is used as indicator for optimal care with lower ratings pointing out that there was room for improvement (28, 29). Further maternity care experience was assessed in terms of access to care, information exchange and perceptions of care. These were evaluated by questions regarding choice of gender of health care professionals, continuity of care, interactions with staff, availability of interpreters, information leaflets, and satisfaction with analgesia, length of stay in the hospital and preferences for care.

2.6. Data quality control

We employed the SBWEMS questionnaire which had good validity and reliability in examining ethnic minority women's satisfaction with antenatal, intrapartum and postnatal care (27). The questionnaire was pilot tested with 10 Pakistani EM women to check any inconsistencies and objections and revised accordingly.

2.7. Data processing and analysis

All the data was checked for completeness and entered in SPSS version 24.0, which was also used for all analysis. Counts and percentages were used to describe all categorical variables including the variables related to outcome variables. Bivariate analyses, including the chi-square test, Fisher's exact test was performed to test the associations between individual predictors and the outcome variables (not shown in results). Multiple logistic regression analysis was then done with the significant independent variables forthree outcome (dependent) variables: less satisfaction with care during pregnancy, labor and birth and after birth. P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Age and parity were adjusted as confounders. The fit of the model was tested using the Hosmer-Lemeshow test.

3. Results

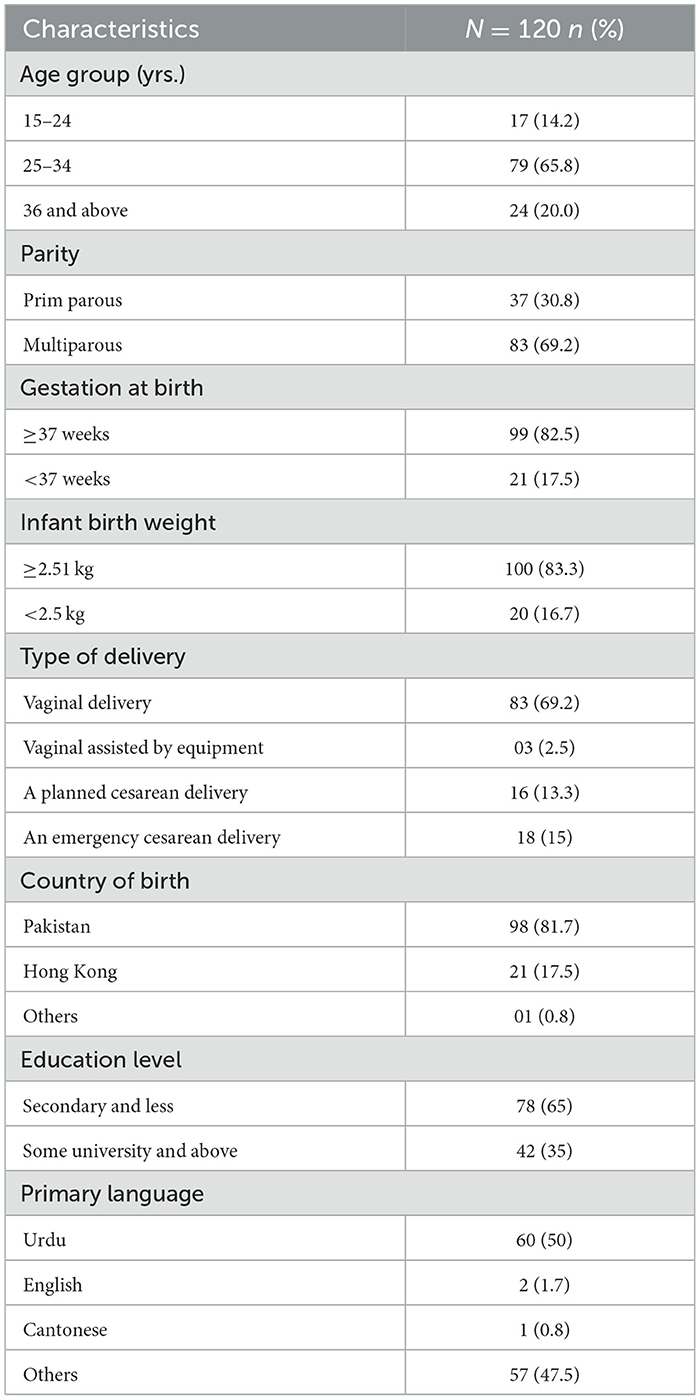

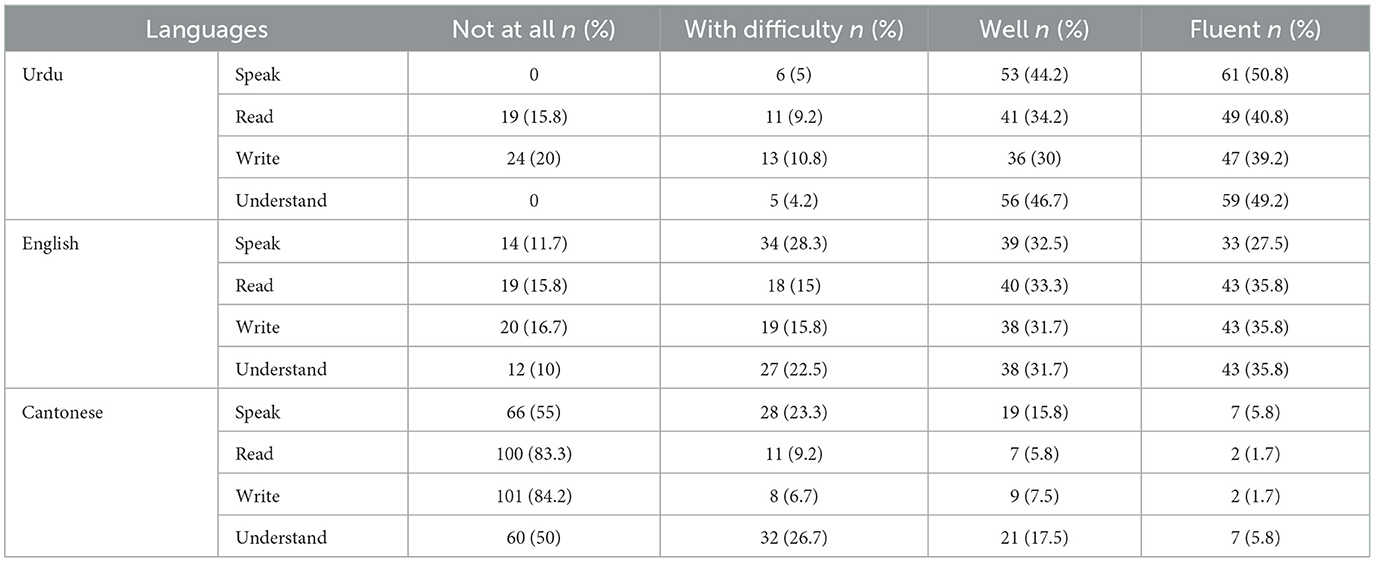

One hundred and twenty questionnaires were completed. Table 1 shows the profile of the participants. The majority of the women were Pakistan born (81.7%), aged at 34 years and below (80.0%), had delivered vaginally (71.7%), at term (82.5%) and had normal birth weight babies (83.3%). About two-thirds of them were multiparous (69.2%) and had education level of Secondary or below (65%). Half of the respondents spoke Urdu as their primary language followed by other regional languages of Pakistan, whereas English and Cantonese were less often spoken as primary languages. Table 2 shows the self-described language ability of the respondents. More than half (60%) were able to speak and two-thirds could read, write and understand English either well or fluently. Only 23.3 and 21.6% women could understand and speak Cantonese well or fluent and very few could read or write.

3.1. Antenatal care

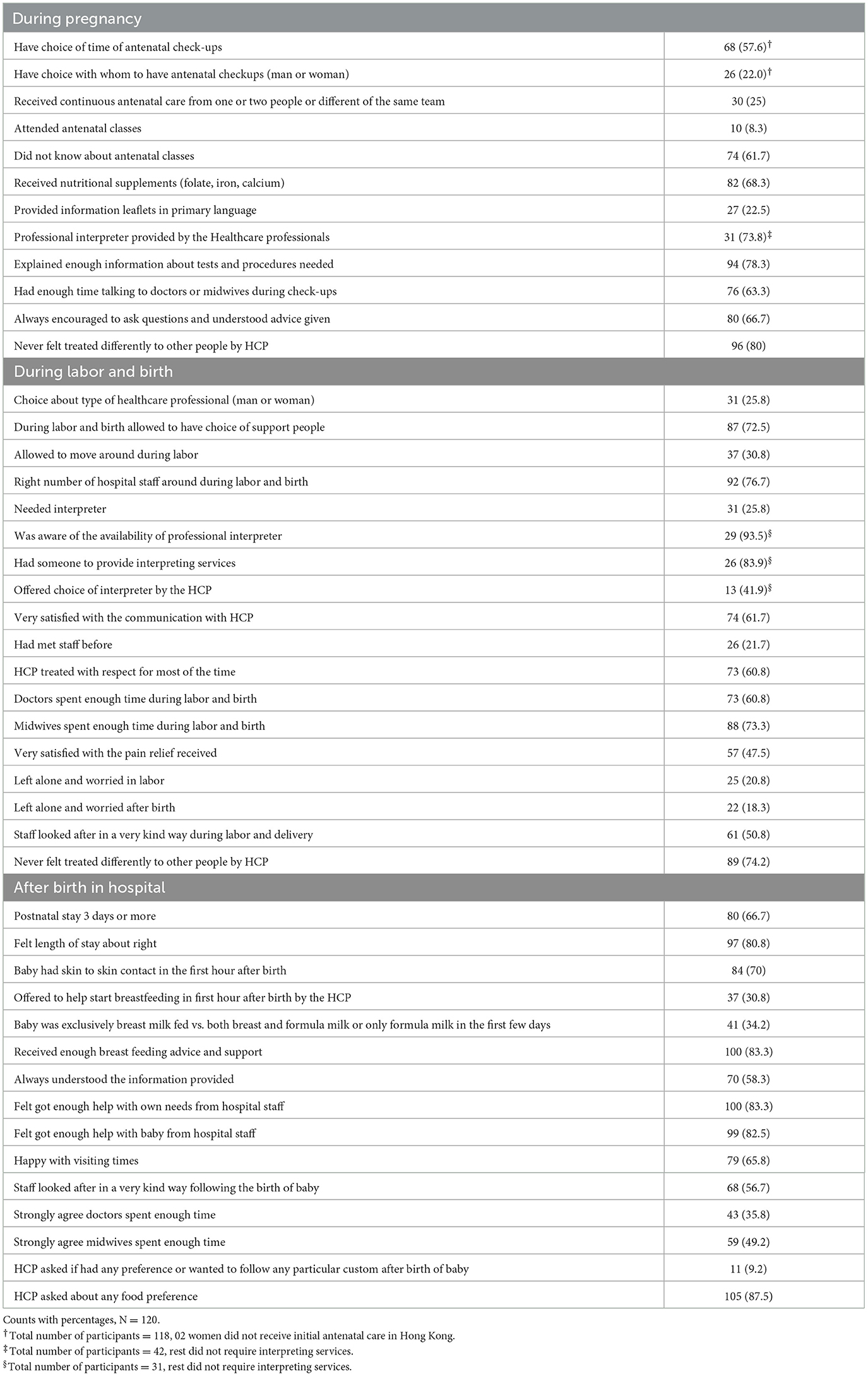

During the antenatal care (Table 3), more than half (57.6%) of the women had choice of time of antenatal checkups but only 22% of the women were given choice of whether to have a man or woman perform their antenatal checkups. Two-thirds (67%) of the women strongly agreed that they were always encouraged to ask questions and always understood the advice given during their checkups. Almost two-thirds (63.3%) had enough time talking to doctors or midwives. Twenty-two percent of the women were provided with information leaflets in their primary language and 59% of those who received them reported that they were understandable and comprehensive. Majority of the women were provided interpreters by HCPs (73.8%). Only ten women attended antenatal classes and 61.7% did not attend the classes due to their lack of knowledge of the existence of these classes.

Table 3. Access to care, information exchange and perceptions of care during the three phases of maternity.

3.2. Intrapartum care

Regarding care during labor and birth (Table 3), most women (73%) were allowed to have choice of supporting people during labor and birth. The majority (84%) had someone to provide interpreting services during labor and birth and of these 42% of the women were offered choice of interpreter by the HCPs. Less than two thirds (61.7%) were very satisfied with the communication with HCP and only half (50.8%) reported a very kind attitude of staff during labor and birth. Less than half (47.5%) of the women were very satisfied with the pain relief received during labor and only 31% were allowed to move during labor.

3.3. Postnatal care in hospital

With respect to care during postnatal period in hospital (Table 3), most of the women (70%) were given skin to skin contact with baby in the first hour after birth. However, only 31% were offered the chance to start breast feeding in the first hour after birth, only 34% of the babies were exclusively breast fed and 40% of the babies received both breast and bottle milk while in the hospital. The majority, 83%, of the women felt that they received enough breast feeding advice and support.

Two-thirds (67%) of the women had a post-natal stay of 3 days or more, and most (80%) felt right about their length of stay. More than half of the respondents (56.7 %) stated that the staff looked after them in a very kind way following the birth of the baby. Less than 10% of women were asked by the HCPs if they had any preference or wanted to follow any particular custom after the baby's birth.

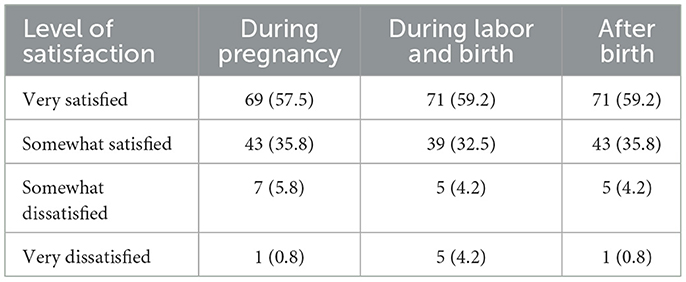

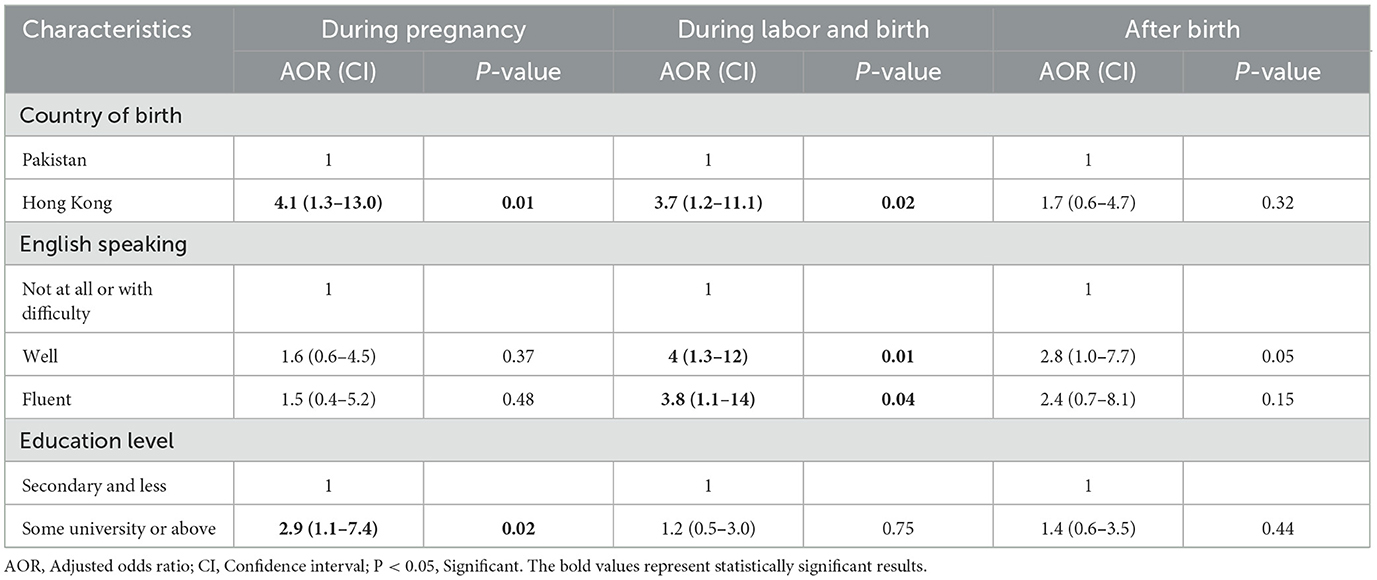

3.4. Satisfaction with care

Women's satisfaction with care during pregnancy, labor/birth and after birth in hospital are shown in the Table 4. More than half of the participants were very satisfied with antenatal care (57.5%), intrapartum care (59.2%) and postnatal care in the hospital (59.2%). Nearly one third were somewhat satisfied with the care received during antenatal (35.8%), intrapartum (32.5%) and postnatal periods (35.8%). Less than 10% were somewhat dissatisfied or very dissatisfied with the maternity care received during the three phases of pregnancy. After adjusting for age and parity, country of birth and education level were statistically significant independent predictors of satisfaction with care during pregnancy; country of birth and English speaking (collapsed into with difficulty or not at all, well, fluent) were statistically significant independent predictors of satisfaction with care during labor and birth; while English speaking had only borderline significant association with satisfaction with care after birth in the multivariable analysis. The p-values of Hosmer Lemeshow statistics for the three models with these variables were 0.305 > 0.05, 0.852 > 0.05, and 0.843 > 0.05 respectively indicating models fit well. The results of the multivariable analysis (Table 5) reflects that HK born Pakistani women were about four times more likely to be less than very satisfied with the antenatal care when compared to Pakistan born women [adjusted odds ratio (AOR) = 4.1, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.3–13.0] and those with education of some university or above were almost 3 times less satisfied with the care received (AOR = 2.9, 95% CI = 1.1–7.4) than those with lower education levels. Also HK born women (AOR = 3.7, 95% CI = 1.2–11.1) and women with English speaking ability of well (AOR = 4.0 95% CI = 1.3–12.0) and fluent (AOR = 3.8, 95% CI = 1.1–14.0) were significantly more likely to be less than very satisfied with the intrapartum care in comparison with Pakistan-born women and women with who could not speak English at all or with difficulty. For postnatal care only those who rated their English speaking as “well” had borderline significantly higher odds of being less than very satisfied (AOR = 2.4 95% CI = 1.0–7.7).

Table 5. Multivariable analysis showing AOR for less satisfaction with the overall maternity care services.

4. Discussion

This study found that the majority of the surveyed Pakistani EM women in HK were either very satisfied or somewhat satisfied with their overall maternity care. More than half of the women described the care they received as kind, respectful and well communicated. Women's country of birth, English-speaking ability and level of education were significant factors associated with level of satisfaction during different phases of pregnancy. HK born Pakistani women expressed relatively less satisfaction with care, especially during pregnancy and labor and birth, as compared with Pakistan born women. Women with conversational or fluent English-speaking ability also felt comparatively less satisfied particularly from intrapartum and postnatal care in hospital. Besides, education level had a negative association with satisfaction with care during pregnancy.

Women's relatively increase satisfaction with care in the present study might be related to developments of maternal health services catering for ethnic minority women over the years. The differences in women's satisfaction in association with country of birth can be explained by women's different expectations of maternity health services and their prior experience of healthcare system (30). Pakistan born women may have previous experience with healthcare in Pakistan, which is a low-income country having less resources as compared to HK. Based on this comparison, these women's expectations of care were fulfilled and they conveyed increased satisfaction with the resources and facilities provided by maternity care services in HK. Similar findings were reported in an Australian study of maternity care experience of immigrant Afghan women in Melbourne, Australia (31). On the contrary, HK born Pakistani women were acquainted with the health services in HK or had past experience of maternity care in HK; as a result, they may have developed greater expectations of care and thus were likely to be critical of the care they received. Similar views were expressed by the UK healthcare professionals providing care to the UK-born EM women. They found UK-born EM mothers to be more self-confident and expressive, and involved in care-related decision making. They had an enhanced understanding of the healthcare system, available resources and expectations of care (32).

Similar to previous research (33, 34), women's expectations and satisfaction with healthcare services also varied with the education level achieved. Women with higher education level tended to be more vocal, information seeking and might anticipate higher level of responsiveness from the healthcare providers. This may explain why Pakistani women with higher education in Hong Kong had less satisfaction with the antenatal services provided.

Effective communication between healthcare professionals and patients is vital for quality care (35); previous research showed language barriers clearly impede good communication between the ethnic minority women and their care givers (12, 36). Yet the settings and findings of the current study are different compared to previous research, which was mainly conducted in English speaking countries (20, 21). In Hong Kong Cantonese is in fact the native language, while English is the second official language (37); in this context, Pakistani women with self-rated conversational or fluent English-speaking ability perceived more language barriers compared to those who had low or no proficiency at all, particularly during labor and birth. The results of this study indicate that most of the women who had no or low English proficiency were provided with interpreting services; as a result, they felt communication was effective and the care received satisfactory. On the other hand, women with increased English-speaking fluency faced difficulties in communication due to the non-availability of English-speaking healthcare professionals, especially midwives and lower-level staff. Therefore, these women felt less responded to and engaged by the maternity care staff and were eventually less satisfied with the care received. A systematic review of immigrant women maternity care experience also highlights the importance of shared language between the women and the service provider. One of the main barriers between immigrant women and their caregivers is the language difficulty which creates hindrance in good communication and understanding. This problem mainly arises when the women are not fluent in the language of the receiving country (29).

The relationship between women and healthcare professionals plays a key role in shaping their perceptions of care, accessing services, utilization and outcomes (12). Although women in this study had increased overall satisfaction with their care, yet their desire for support, kind behavior of staff, understanding and respectful attitude were not fulfilled to a larger extent particularly during labor and birth. Conversely, positive experiences were reported when the staff showed empathy, attended to their individual needs with patience, sensitivity and in a timely manner. These findings are consistent with other studies of ethnic minority women's experience of maternity care (12, 21, 38, 39).

4.1. Strengths and limitations

This study has some limitations. Firstly, it did not include the local population for comparison and also the results cannot be implied to other ethnic minority groups. Secondly women who had given birth within the previous 3 years were included in the study, they might have had difficulties in recalling their experiences and introduce potential recall bias. Thirdly our sample size was relatively small as we were not able to achieve our calculated sample size.

Despite of the abovementioned limitations, this study has some strengths too. It is the first to explore the maternity care experience of ethnic minority Pakistani women in HK. Estimating satisfaction is not easy. Respondents may be hesitant to acknowledge dissatisfaction. In this study the interviews conducted by an interviewer of same gender and ethnic group as the respondent, and in the language of women's choice, is probably a protection against the likelihood that dissatisfaction would not be expressed. Involvement of the bilingual researcher sharing the similar ethnicity and cultural upbringing as that of respondents ensured the participation of this hard to reach group. This improves the integrity of the study (40), and indeed the sample was heterogeneous ranging from only Urdu speaking mothers to mothers having English fluency and women who bridged educational spectrum from illiteracy to higher degrees.

4.2. Implications

The study demonstrated that effective communication and care that can meet individual expectations, needs and values are essential for providing good quality care to the Pakistani EM women. Maternity care providers should take into account the diversity of EM population in HK. In addition to the provision of interpreters and social assistance to the women with decrease language proficiency and education level, it is also necessary to provide opportunities for the educated and well-spoken women. There is a need to increase the number of Midwives and lower staff with enhanced English language fluency in HK so that language barrier can be overcome and better communication can facilitate better maternity care experience and improve maternal and health outcomes. Thus, it reiterates the importance of provision of person-centered maternity care in improving quality and reducing inequalities among ethnic minority and migrant women.

5. Conclusion

This study gives an insight into the evaluation of maternal healthcare system of HK from a sub-group of EM women perspective. Providing person-centered care and addressing barriers in communication can lead to relatively higher level of satisfaction and improvements in the quality of care provided to EM population. Further research is required in this under researched area with the involvement of broader and diverse ethnic minority groups.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Survey and Behavioral Research Ethics Committee, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, (SBRE-19-521). The patients/participants provided their verbal informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

Conceptualization and methodology: SA, EN, WG, and DD. Data collection and writing—original draft preparation: SA. Data analysis: SA and WG. Data curation: SA, EN, and WG. Visualization: DD. Writing—review and editing: EN, DD, WG, and E-KY. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our thanks to the Chinese University of Hong Kong, Jockey Club School of Public Health and Primary care, who granted permission for the work, and to the Pakistani women who gave up their time and shared their perspectives so generously.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). Available online at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/millennium-development-goals-(mdgs) (accessed January 27, 2023).

2. Health - United Nations Sustainable Development. Available online at: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/health/ (accessed August 1, 2022).

3. Survive Thrive Transform the Global Strategy for Women's Children's and Adolescents' Health (2016-2030) at a Glance. Available online at: www.everywomaneverychild.org (accessed August 1, 2022).

4. Fair F, Raben L, Watson H, Vivilaki V, van den Muijsenbergh M, Soltani H. Migrant women's experiences of pregnancy, childbirth and maternity care in European countries: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. (2020) 15:e0228378. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0228378

5. Grobman WA, Bailit JL, Rice MM, Wapner RJ, Reddy UM, Varner MW, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in maternal morbidity and obstetric care. Obst Gynecol. (2015) 125:1460. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000735

6. Henderson J, Gao H, Redshaw M. Experiencing maternity care: the care received and perceptions of women from different ethnic groups. BMC Preg Childbirth. (2013) 13:1–14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-13-196

7. Gennaro S, O'Connor C, McKay EA, Gibeau A, Aviles M, Hoying J, et al. Perinatal anxiety and depression in minority women. MCN Am J Mater Child Nurs. (2020) 45:138. doi: 10.1097/NMC.0000000000000611

8. Shakeel N, Eberhard-Gran M, Sletner L, Slinning K, Martinsen EW, Holme I, et al. A prospective cohort study of depression in pregnancy, prevalence and risk factors in a multi-ethnic population. BMC Preg Childbirth. (2015) 15:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12884-014-0420-0

9. Wang E, Glazer KB, Sofaer S, Balbierz A, Howell EA. Racial and ethnic disparities in severe maternal morbidity: a qualitative study of women's experiences of peripartum care. Women's Health Issues. (2021) 31:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2020.09.002

10. Puthussery S. Perinatal outcomes among migrant mothers in the United Kingdom: is it a matter of biology, behaviour, policy, social determinants or access to health care? Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. (2016) 32:39–49. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2015.09.003

11. Crowe R. Factors contributing to maternal health inequalities for women who are not white British in the UK. Br J Midwifery. (2022) 30:160–71. doi: 10.12968/bjom.2022.30.3.160

12. Higginbottom GMA, Evans C, Morgan M, Bharj KK, Eldridge J, Hussain B. Experience of and access to maternity care in the UK by immigrant women: a narrative synthesis systematic review. BMJ Open. (2019) 9:e029478. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029478

13. Crabtree S, Wong H. 'Ah Cha'! The racial discrimination of Pakistani minority communities in Hong Kong: an analysis of multiple, intersecting oppressions. Soc Work. 43:945–63. doi: 10.1093/bjsw/bcs026

14. O'Connor P. Islam in Hong Kong: Muslims and Everyday Life in China's World City. Islam in Hong Kong: Muslims and Everyday Life in China's World City. Oxford: Oxford academic (2012). p. 1–217.

15. Chen C, Chan KH. Type 2 Diabetes Management in Hong Kong Ethnic Minorities: What Primary Care Physicians Need to Know. (2014) 20:222–8. Available online at: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/ff2b/9e7316bd519d4611c7f74409d15d998b5da4.pdf (accessed August 1, 2022).

16. Vandan N, Wong JYH, Gong WJ, Yip PSF, Fong DYT. Health system responsiveness in Hong Kong: a comparison between South Asian and Chinese patients' experiences. Public Health. (2020) 182:81–7. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.01.019

17. Vandan N, Wong JYH, Fong DYT. Accessing health care: experiences of South Asian ethnic minority women in Hong Kong. Nurs Health Sci. (2019) 21:93–101. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12564

18. Garcia R, Ali N, Guppy A, Griffiths M, Randhawa G. Ethnic differences in risk factors for adverse birth outcomes between Pakistani, Bangladeshi, and White British mothers. J Adv Nurs. (2020) 76:174–82. doi: 10.1111/jan.14209

19. Garcia R, Ali N, Griffiths M, Randhawa G. Understanding the consumption of folic acid during preconception, among Pakistani, Bangladeshi and white British mothers in Luton, UK: a qualitative study. BMC Preg Childbirth. (2018) 18:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-1884-0

20. Cross-Sudworth F, Williams A, Herron-Marx S. Maternity services in multi-cultural Britain: using Q methodology to explore the views of first- and second-generation women of Pakistani origin. Midwifery. (2011) 27:458–68. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2010.03.001

21. Pakistani Muslim Women Birthing in Northern England: Exploration of Experiences and Context - ProQuest. >Available online at: https://www.proquest.com/openview/dbabab0c72b92c9e2607ac14a0f615ae/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=2026366 (accessed August 1, 2022).

22. Vangen S, Stoltenberg C, Schei B. Ethnicity & Health Ethnicity use of obstetrical analgesia: Do Pakistani women receive inadequate pain relief in labour? (2010). Available online at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.1996.9961783 (accessed August 1, 2022).

23. Centre for Health Protection - Major Health Indicators in 2020 2021. Available online at: https://www.chp.gov.hk/en/statistics/data/10/27/110.html (accessed August 1, 2022).

24. Tunçalp, Were WM, Maclennan C, Oladapo OT, Gülmezoglu AM, Bahl R, et al. Quality of care for pregnant women and newborns - The WHO vision. BJOG. (2015) 122:1045–9. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13451

25. World Health. Standards for improving quality of maternal and newborn care in health facilities. WHO. (2016) 2021:84. Available online at: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/mca-documents/qoc/quality-of-care/standards-for-improving-quality-of-maternal-and-newborn-care-in-health-facilities.pdf

26. Lwanga SK, Lemeshow S. Sample Size determination in Health Studies. Geneva: WHO (1991). p. 1–88.

27. Duff LA, Lamping DL, Ahmed LB. Evaluating satisfaction with maternity care in women from minority ethnic communities: development and validation of a Sylheti questionnaire. Int J Qual Health Care. (2001) 13:215–30. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/13.3.215

28. Hennegan J, Redshaw M, Miller Y. Born in another country: women's experience of labour and birth in Queensland, Australia. Women Birth. (2014) 27:91–7. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2014.02.002

29. Small R, Roth C, Raval M, Shafiei T, Korfker D, Heaman M, et al. Immigrant and non-immigrant women's experiences of maternity care: a systematic and comparative review of studies in five countries. BMC Preg Childbirth. (2014) 14:1–17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-152

30. Lakin K, Kane S. Peoples' expectations of healthcare: a conceptual review and proposed analytical framework. Soc Sci Med. (2022) 292:114636. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114636

31. Shafiei T, Small R, McLachlan H. Women's views and experiences of maternity care: A study of immigrant Afghan women in Melbourne, Australia. Midwifery. (2012) 28:198–203. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2011.02.008

32. Puthussery S, Twamley K, Harding S, Mirsky J, Baron M, Macfarlane A. “They're more like ordinary stroppy British women”: attitudes and expectations of maternity care professionals to UK-born ethnic minority women. Sage J. (2008) 13:195–201. doi: 10.1258/jhsrp.2008.007153

33. Chemir F, Alemseged F, Workneh D. Satisfaction with focused antenatal care service and associated factors among pregnant women attending focused antenatal care at health centers in Jimma town, Jimma zone, South West Ethiopia; A facility based cross-sectional study triangulated with qualit. BMC Res Notes. (2014) 7:164. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-7-164

34. Quintana JM, González N, Bilbao A, Aizpuru F, Escobar A, Esteban C, et al. Predictors of patient satisfaction with hospital health care. BMC Health Ser Res. (2006) 6:102. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-6-102

35. Binder P, Borné Y, Johnsdotter S, Essén B. Shared language is essential: Communication in a multiethnic obstetric care setting. J Health Commun. (2012) 17:1171–86. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2012.665421

36. Attanasio L, Kozhimannil KB. Patient-reported communication quality and perceived discrimination in maternity care. Med Care. (2015) 53:863–71. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000411

37. Language Log ≫ Cantonese: Still the Main Spoken Language of Hong Kong. Available online at: https://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=33511 (accessed December 21, 2022).

38. Jomeen J, Redshaw M. Ethnic minority women's experience of maternity services in England. Ethn Health. (2013) 18:280–96. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2012.730608

39. Redshaw M, Heikkilä K. Ethnic differences in women's worries about labour and birth. Ethn Health. (2011) 16:213–23. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2011.561302

40. Eboh WO, Pitchforth E, Teijlingen E, van. Lost words: research via translation. Midwives Magazine. (2007). 10:374–8. Available online at: https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?p=AONE&sw=w&issn=14792915&v=2.1&it=r&id=GALE%7CA169595679&sid=googleScholar&linkaccess=fulltext (accessed December 21, 2022).

Keywords: Pakistani women, maternity care, ethnic minority, immigrant, Hong Kong

Citation: Asim S, Nichini E, Goggins WB, Dong D and Yeoh E-K (2023) Maternity care experience of Pakistani ethnic minority women in Hong Kong. Front. Public Health 11:1009214. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1009214

Received: 01 August 2022; Accepted: 07 February 2023;

Published: 01 March 2023.

Edited by:

Chi Kin Law, The University of Sydney, AustraliaReviewed by:

Adera Debella, Haramaya University, EthiopiaAna V. Pejcic, University of Kragujevac, Serbia

Copyright © 2023 Asim, Nichini, Goggins, Dong and Yeoh. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Dong Dong, ZG9uZ2RvbmdAY3Voay5lZHUuaGs=

Saba Asim

Saba Asim Elena Nichini

Elena Nichini William Bernard Goggins1

William Bernard Goggins1 Dong Dong

Dong Dong Eng-King Yeoh

Eng-King Yeoh