- 1Division of Quality of Life and Palliative Care, St. Jude Children's Research Hospital, Memphis, TN, United States

- 2Division of Pediatric Palliative Care, University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, TN, United States

- 3School for Policy Studies, University of Bristol, Bristol, United Kingdom

- 4Department of Paediatric Oncology, Southampton Children's Hospital, Southampton, United Kingdom

Introduction: SARS-CoV-2 has led to an unprecedented pandemic where vulnerable populations, such as those with childhood cancer, face increased risk of morbidity and mortality. COVID-19 vaccines are a critical intervention to control the pandemic and ensure patient safety. This study explores global caregiver's perspectives related to COVID-19 immunization in the context of pediatric cancer management.

Methods: A mixed methods survey was developed based on consensus questions with iterative feedback from global medical professional and caregiver groups and distributed globally to caregivers of childhood cancer via electronic and paper routes. We present qualitative findings through inductive content analysis of caregiver free-text responses.

Results: A total of 184 participants provided qualitative responses, 29.3% of total survey respondents, with a total of 271 codes applied. Codes focused on themes related to safety and effectiveness (n = 95, 35.1%), logistics (n = 69, 25.5%), statements supporting or opposing vaccination (n = 55, 20.3%), and statements discussing the limited availability of information (n = 31, 11.4%). Within the theme of safety and effectiveness, safety itself was the most commonly used code (n = 66, 24.4% of total segments and 69.5% of safety and effectiveness codes), followed by risks versus benefits (n = 18, 18.9% of safety and effectiveness codes) and efficacy (n = 11, 11.6%).

Discussion: This study provides insights to guide healthcare professionals and caregiver peers in supporting families during the complex decision-making process for COVID-19 vaccination. These findings highlight the multidimensionality of concerns and considerations of caregivers of children with cancer regarding COVID-19 vaccination and suggest that certain perspectives transcend borders and cultures.

Introduction

Vaccination decision-making has challenged healthcare professionals for decades, with vaccine hesitancy remaining a significant threat to global public health in the 21st century (1, 2). With the emergence of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and relatively recent approvals for vaccines for pediatric populations, global public concerns around vaccine safety and value for children have further intensified in recent months (3–6). These growing concerns not only threaten vaccine rates for community protection over time, but also more immediately place vulnerable individuals at increased risk.

The virulence of SARS-CoV-2, resulting in staggering morbidity and mortality worldwide from the disease known as COVID-19, has underscored the urgent need to explore and better understand roots and drivers behind vaccine decision-making, particularly within vulnerable pediatric subpopulations. While healthy children and adolescents infected by SARS-CoV-2 generally experience milder illness than adults (7), the Global Registry of COVID-19 in Childhood Cancer revealed that children and adolescents with cancer are more likely to develop severe or critical illness when exposed to SARS-CoV-2. Specifically, one in five patients developed severe or critical illness and ~4% died, well above the projected statistics for healthy children (8). Additional reviews with global perspectives have emphasized this increased risk amongst patients with childhood cancer (9, 10).

While numerous studies have investigated attitudes and perceptions surrounding COVID-19 vaccination in adults (11–17), fewer studies have examined parental considerations for COVID-19 vaccination of children in the setting of recent authorization of a pediatric vaccine (3, 5, 6, 18–26). To our knowledge, one prior study has explored vaccine willingness and hesitancy in the context of pediatric cancer, targeting the views of U.S.-based caregivers of childhood cancer survivors; within this cohort, 29% of caregivers expressed vaccine hesitancy, and confidence in COVID-19 vaccination and its value for childhood cancer survivors emerged as a prominent theme (27).

The 2013 World Health Organization (WHO) Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization (SAGE) Vaccine Hesitancy Working Group recognized vaccine decision-making as a complex and dynamic process where certain factors may be more important in specific contexts or during certain experiences (28). Currently, the perspectives, values, and concerns of caregivers about COVID-19 vaccination for children with cancer globally remain poorly understood. Understanding the views of pediatric cancer caregivers on COVID-19 immunization is important to enable healthcare professionals to better support families and provide anticipatory guidance on vaccine administration.

To address this gap in knowledge, a Vaccine Working Group collaboration between the International Society of Paediatric Oncology (SIOP) and St. Jude Children's Research Hospital (SJCRH) was formed with the goal of better understanding COVID-19 vaccine decision-making related to the care of children with cancer. In this paper, we present qualitative findings from a global assessment of caregiver perspectives related to COVID-19 vaccination in the context of pediatric cancer management.

Materials and methods

Survey tool development

A COVID-19 Vaccine Working Group on Pediatric Oncology was established in March 2021 to answer and investigate COVID-19 vaccine questions. Twelve members consisting of oncologists, infectious disease physicians, and nurses were selected to represent various regions around the world. Working group members nominated parent representatives to contribute to the project from their own country including the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Philippines, Indonesia, India, and Ghana. These parents established the Parent/Carer Advisory Group, comprising nine individuals representing patients with cancer and their families from various global regions (29).

A mixed methods survey was developed, guided by content from a professional statement by the COVID-19 and Childhood Cancer Vaccine Working Group collaboration between SIOP and SJCRH (30). The initial consensus questions were derived from global professional healthcare organizations and narrowed via a modified Delphi method amongst the Vaccine Working Group members, with a total of three voting sessions to reach consensus. The initial consensus questions were reviewed by the Parent/Carer Advisory Group, and members of the Advisory Group contributed or revised question items as needed to strengthen face and content validity; the survey underwent iterative stages of feedback with collaborative Advisory Group review to yield the final survey. The survey was piloted with a small group of parents with experience in childhood cancer to test face and content validity of the question items.

The final survey contained three background questions, 19 quantitative Likert scale questions, and a summative open-ended question asking participants to share their questions and perspectives about administration of the COVID-19 vaccine in children with cancer; the survey instrument is presented in Supplementary Table 1. The background or demographic questions focused on country of residence, type of childhood cancer, and timing of the child's cancer experience.

Eligibility criteria, recruitment, enrollment, and data collection

Any parents or primary caregivers of those with childhood cancer were eligible for participation. Each member of the Parent/Carer Advisory Group disseminated the survey to respondents in their own country primarily via social media, online forums, and email distribution. The Working Group members also disseminated the survey to caregivers in each of their countries. The survey was primarily distributed online via SurveyMonkey. A small proportion of respondents (i.e., those from South Africa and Ghana) were approached with paper forms due to limited WiFi in the clinic space where surveys were distributed; responses were then entered manually into the electronic database. The survey was translated into Spanish for dissemination in Spanish-speaking countries; otherwise, an English version was distributed. The survey was disseminated between April and May 2021, remaining open for 4 weeks. Sampling utilized convenience and snowball techniques, with an emphasis on targeting existing pediatric cancer caregiver forums including the international Momcology email distribution listserv and other country-specific online and social media pediatric cancer caregiver communities. Following collection of data via SurveyMonkey and paper surveys, a de-identified CSV file was produced, and a targeted file comprising demographic characteristics and open ended item responses was uploaded to MAXQDA, a qualitative and mixed methods data analysis software system.

The study was classified as informational by SJCRH and exempt from Institutional Review Board approval. The involvement of patients and public advisors was also not deemed subject to ethical approval by the U.K. National Research Ethics Services. Following a brief introduction to the aim, respondents provided informed consent prior to survey completion by answering “yes” to the first question explaining inclusion criteria and that no identifiable information would be collected.

Data analysis

This article presents findings from qualitative analysis of the summative open-ended question; analysis focused on responses to a single free text qualitative question, and all those who provided free text responses were included. Any free text response was considered to be a complete unit of response. We describe study methods and findings following the COREQ (Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research) checklist (Supplementary Table 2) (31). Inductive content analysis was conducted across free-text responses by researchers representing three distinct perspectives: (1) a pediatrician with global health training and expertise (A.S.), (2) a parent of a child with cancer with population health research expertise (J.G.), and (3) a pediatric oncologist with qualitative research expertise (E.K.) (Supplementary Table 3) (32).

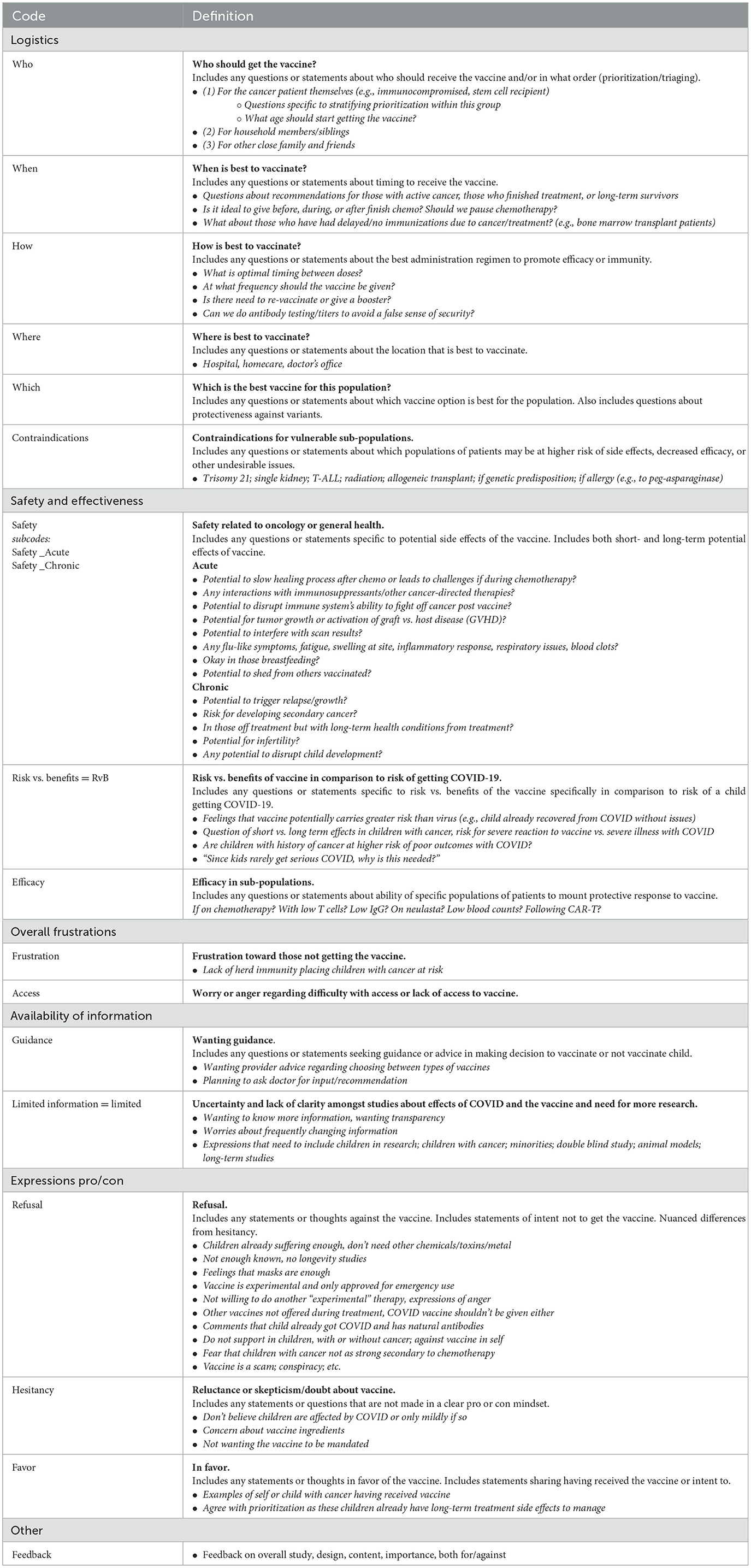

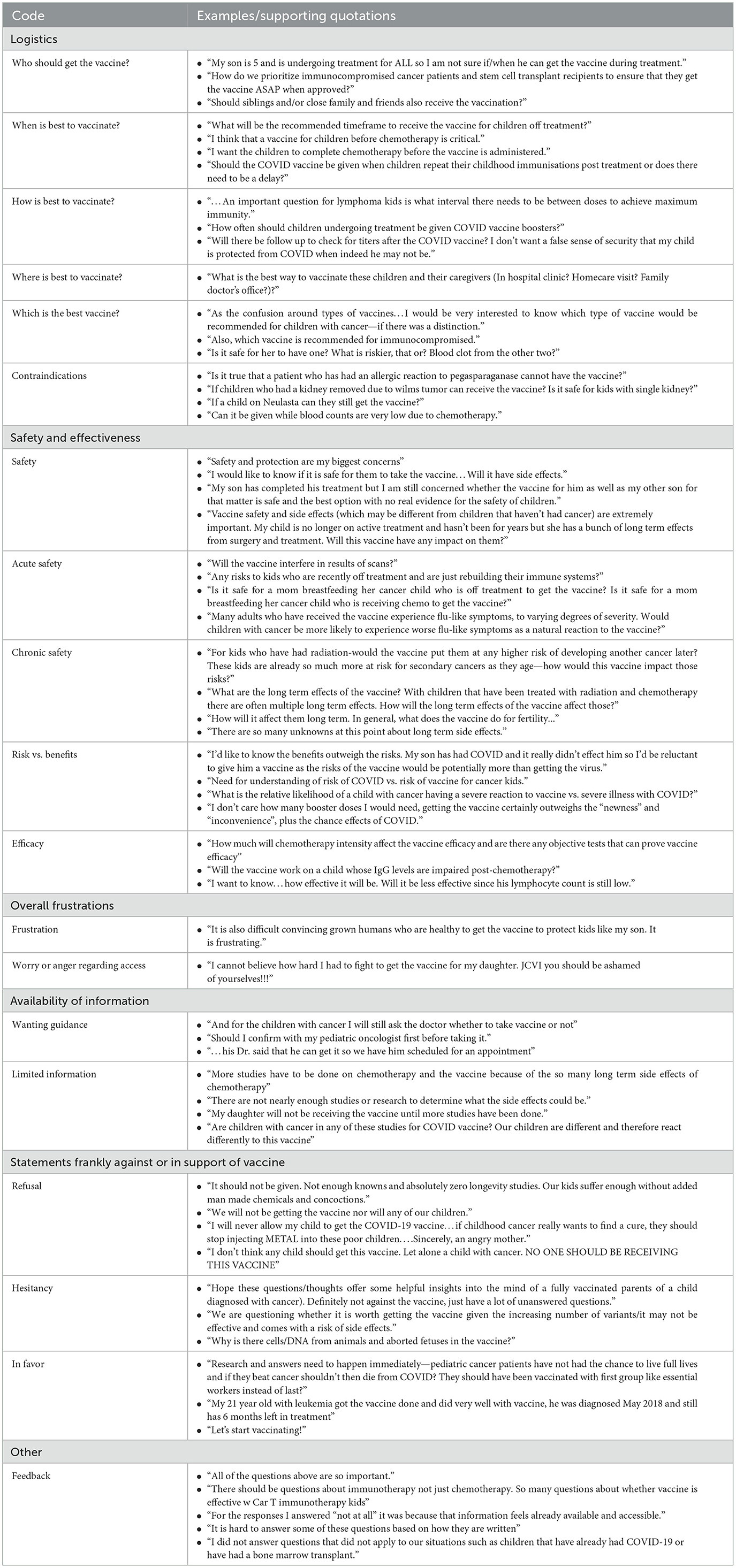

Research analysists (A.S., J.G., E.K.) reviewed transcripts in depth and conducted memo-writing to begin identifying concepts and patterns. Through this process, an inductive codebook was developed and refined iteratively until no further concepts were identified and saturation was achieved. Code definitions and examples were pilot-tested (A.S., J.G.) across complex responses to identify areas of variance, with minor modifications to language and content made as needed to ensure consistency in code application across transcripts (A.S., J.G., E.K.). The final codebook comprised six broad categories which included a total of 17 codes and two embedded subcodes (Table 1).

The codebook was applied across all responses (A.S., J.G.) with data organized in MAXQDA. The research team met at regular intervals to review findings and reconcile variances, with third-party adjudication (E.K.) to achieve consensus. For responses that met criteria for multiple codes, responses were dual-coded to capture diversity and nuance within perspectives. Following finalization of coding, the team reviewed codes to identify patterns and generate themes (33). Once patterns were established, the team conducted quantitative analyses to describe frequencies of responses. Available demographics (e.g., respondent country's World Bank Income Group and WHO Region, type of childhood cancer, and timing of child's cancer experience) were evaluated for differences between those who responded to the qualitative question compared to those who did not and the entire cohort.

Results

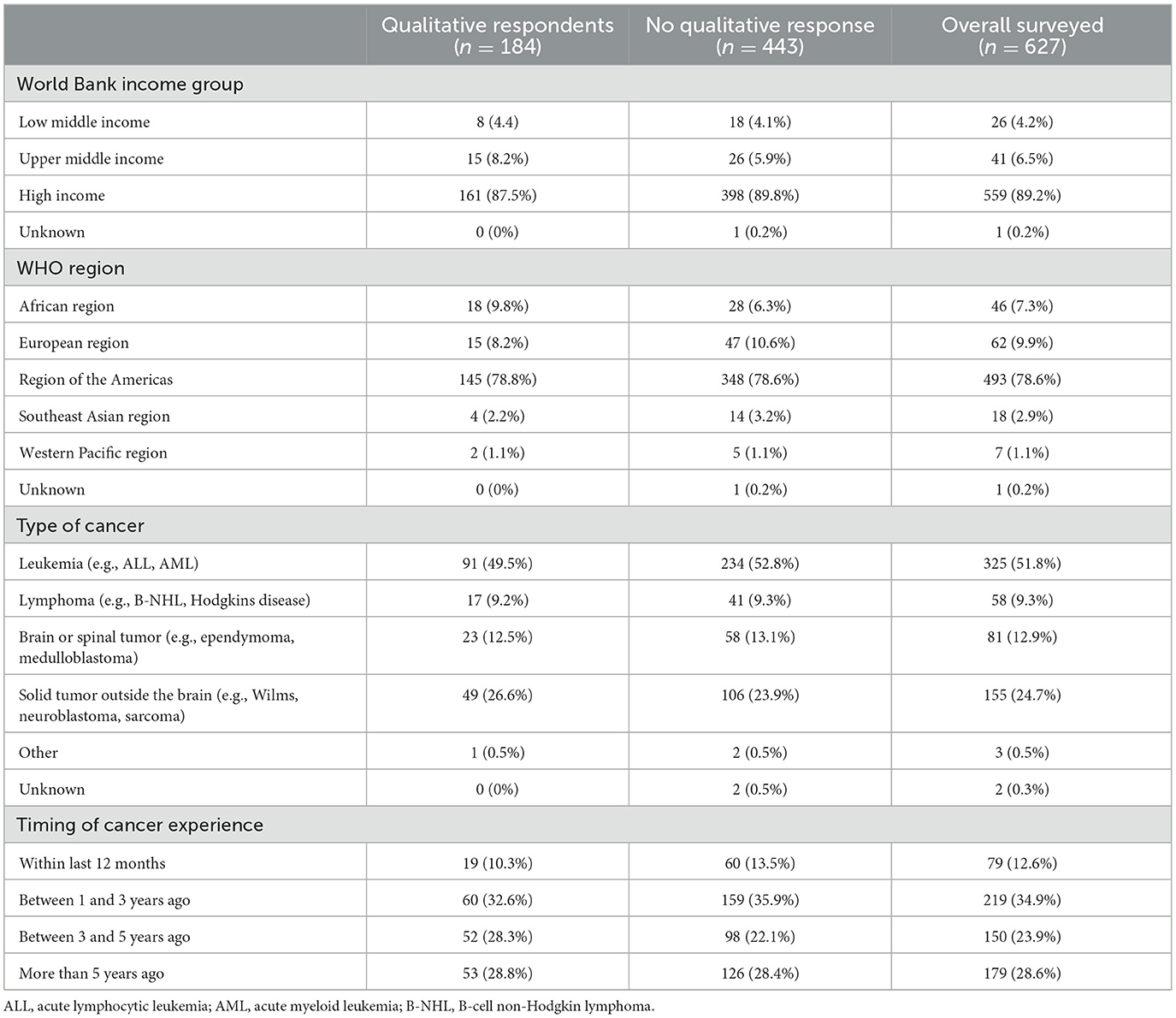

Of the 627 total survey participants from 22 countries, a total of 184 persons (29.3%) provided free-text comments. Broad patient characteristics of those who responded to the open-ended question were similar to those who opted not to respond to the question (Table 2).

Across the transcript of free-text responses from 184 respondents, a total of 271 codes were applied. Approximately one-third of codes (n = 95, 35.1%) were related to safety and effectiveness, one-quarter (n = 69, 25.5%) related to logistics, and one-fifth (n = 55, 20.3%) related to statements in support of or against vaccination. Other emerging concepts included availability of information (n = 36, 13.3%) and overall frustrations (n = 2, 0.7%). The remaining codes referenced survey feedback or “other” comments not related to identified themes (n = 14, 5.2%). Supporting quotations for each of the themes are presented in Table 3. Frequencies of codes within each thematic domain are shown in Figure 1. Results from these analyses aligned with quantitative themes identified by Principal Component Analysis (34).

Safety and effectiveness

Statements related to safety and effectiveness were most commonly coded (n = 95, 35.1%). Within this category, statements asking questions or expressing concerns about safety were the single most used code (n = 66, 24.4% of total segments and 69.5% of safety and effectiveness codes). One caregiver asked, “Vaccine safety and side effects (which may be different from children that haven't had cancer) are extremely important. My child is no longer on active treatment and hasn't been for years but she has a bunch of long term effects from surgery and treatment. Will this vaccine have any impact on them?” Seven of these 66 coded safety segments were double coded as containing both acute and chronic or acute/chronic and non-specific safety comments. Of safety-specific segments, 20.5% (n = 15) specifically addressed acute safety concerns and 37.0% (n = 27) addressed chronic safety. Acute safety concerns included comments such as, “Does the vaccine have the possibility of affecting how well my child's body will be able to fight off her cancer cells?” while chronic safety included questions such as, “How will it affect them long term. In general, what does the vaccine do for fertility….” Some safety codes addressed broad safety concerns, relevant to the general pediatric population, while others were specific to oncologic concerns. The remaining safety and effectiveness codes addressed risks vs. benefits (n = 18, 18.9% of safety and effectiveness codes): “What is the relative likelihood of a child with cancer having a severe reaction to vaccine vs. severe illness with COVID?”; and efficacy (n = 11, 11.6%): “I want to know…how effective it will be. Will it be less effective since his lymphocyte count is still low?”

Logistics

Out of the 69 coded segments related to logistics, 24 (34.8%) were specific to contraindications. One caregiver stated, “Is it true that a patient who has had an allergic reaction to pegasparaganase [PEG-asparaginase] cannot have the vaccine?” A similar number of segments (21, 30.4%) focused on who should get the vaccine (“Should siblings and/or close family and friends also receive the vaccination?”), while relatively fewer codes (13, 18.8%) centered on optimal timing for vaccination (“What will be the recommended timeframe to receive the vaccine for children off treatment?”). Other logistical concerns underscored best practices for children actively receiving cancer-directed therapy (7, 10.1%: “How often should children undergoing treatment be given COVID vaccine boosters?”); which vaccine is best (3, 4.3%: “As the confusion around types of vaccines…I would be very interested to know which type of vaccine would be recommended for children with cancer—if there was a distinction.”); and where to receive the vaccine [1, 1.4%: “What is the best way to vaccinate these children and their caregivers (In hospital clinic? Homecare visit? Family doctor's office?)?”].

Statements against or in support of vacciation

Twenty (36.4%) of the 55 broad category statements were in favor of the vaccine, 19 (34.5%) refusing the vaccine, and 16 (29.1%) reflecting hesitation about the vaccine. Statements in favor included, “Let's start vaccinating!” Conversely, refusal statements expressed, “I will never allow my child to get the COVID-19 vaccine.”

Availability of information

A total of 31 statements (11.4% of all coded segments) discussed the limited availability of information about the vaccine, with one parent commenting, “My daughter will not be receiving the vaccine until more studies have been done.” Other comments reflected wishes for guidance in their decision-making process given dearth of available information, such as, “Should I confirm with my pediatric oncologist first before taking it.”

Overall frustrations

One caregiver discussed frustrations toward those not getting the vaccine: “It is also difficult convincing grown humans who are healthy to get the vaccine to protect kids like my son. It is frustrating.” Another expressed frustrations around difficulty with access to the vaccine: “I cannot believe how hard I had to fight to get the vaccine for my daughter….”

Discussion

This study explores qualitative responses from a global assessment of caregiver perspectives on COVID-19 vaccination in childhood cancer, with the goal of gaining insights to guide healthcare professionals in supporting families during their complex decision-making process. As the first global study specific to childhood cancer to investigate COVID-19 vaccine views, we identified distinct themes with nearly three-quarters of caregiver comments focused on safety and effectiveness, logistics, and limited information to guide decision-making.

Although attitudes specific to COVID-19 vaccination are complex and multifactorial, thematic patterns appear to transcend borders and cultures. Studies from various countries consistently show that safety, effectiveness, and limited information are significant drivers of COVID-19 vaccination in Brazil (3), China (5, 25), Saudi Arabia (4), Turkey (22, 23), the United States (35, 36), and other countries. Our findings corroborate vaccine safety and effectiveness as a primary consideration across multiple countries, comprising over one-third of narrative content. More than one in ten caregivers commented on the availability of information, primarily related to how perceived deficits in knowledge adversely impacted their decision-making.

Among the 184 qualitative responses, a total of 271 codes were applied. This breadth of inductive coding underscores the multidimensionality of perspectives, where many caregivers considered multiple factors of vaccination and were not focused on one aspect of care. This highlights the complexity of caregivers' views and the need for healthcare providers to discuss a variety of considerations. Importantly, explored dimensions may be interrelated, and caregiver questions should be explored with awareness of how they may connect to other questions to encourage vaccine uptake.

With respect to safety, more caregivers reflected about chronic or long-term side effects compared to acute side effects. This may reflect uncertainty and fear related to limited knowledge about long-term side effects given the novelty of the COVID-19 vaccine. Caregivers already face uncertainty and fear about long-term impacts of cancer and cancer therapy on their child's future, which may exacerbate worries about any additional long-term vaccine effects. Additionally, we hypothesize that caregivers also may have concerns about long-term effects as a result of their prior or ongoing experiences with long-term effects from cancer treatment, sensitizing them toward these risks. Healthcare professionals should recognize these fears with compassion, acknowledge when data are limited, and anchor discussion and recommendations about vaccines in available information to address specific concerns. While the COVID-19 vaccine itself is relatively new, the science underpinning its development and the efficacy and safety of vaccination programs are supported by decades of extensive testing and expert guidance (37, 38). Public health strategies should focus on existing information to address myths or fears related to long-term effects.

Additionally, evidence suggests that perceived risk for COVID-19 disease in children informs parental decision-making (26, 27, 35, 39, 40). Our findings corroborate this phenomenon, with some caregivers questioning or asserting that children are unlikely to transmit or develop serious illness from COVID-19 while others believed that children with cancer face increased risk. We encourage healthcare professionals to explore upfront caregiver beliefs about COVID-19 risks to children prior to offering recommendations about vaccination. When caregivers think risk is negligible, early discussion around known risks of COVID-19 may lay a better foundation upon which to build future recommendations.

Caregivers also repeatedly expressed concerns about limited information and frustrations that data for children are often lagging. These data build upon existing research in which parents express a need for better evidence and transparency about vaccine development, efficacy, and safety (39). In pediatric cancer as a whole, consensus is lacking on general vaccination efficacy and timing to achieve immunogenicity, including holding and repeating vaccines (41–43). Cancer patients were excluded from initial trials for COVID-19 vaccinations, and data on the immunogenicity and safety of COVID-19 vaccines in cancer patients lags behind general pediatrics data. Subsequent studies have explored vaccine safety and efficacy in adult cancer patients at various disease stages of disease (active, remission, post-transplant) (44–51), yet data in pediatric cancer populations remains scarce. We encourage clinicians to acknowledge this lack of data and empathize with caregiver frustrations, affirming their feelings, prior to sharing available information.

Fortunately, healthcare providers can influence decision-making (18, 52). Specifically, caregivers of childhood cancer patients who received information from cancer care professionals were more likely to vaccinate both themselves and their children (27). Although each family is unique, there are common drivers for vaccine decision-making that can be addressed with intention and specificity (1). After asking questions, affirming emotions, and developing therapeutic alliance with caregivers, we advocate for healthcare providers to focus on explaining safety and effectiveness, providing information on logistics for administration, and filling in knowledge gaps in the setting of limited information.

While this analysis focused on the role of healthcare providers in supporting and encouraging families in their decision-making, we also emphasize the critical role that caregivers play in supporting decision-making for other families. In this study, no free-text responses focused on the role of peers or support groups in their own decision-making; however, prior studies have emphasized the value of peers as a form of emotional and informational support in the setting of shared personal experiences in oncology (53). Further research should explore the impact of peer support and guidance in vaccine decision-making.

Finally, caregiver perspectives in this study affirmed themes outlined by the WHO SAGE Vaccine Hesitancy Working Group in their characterization of vaccine hesitancy as “a behavior, influenced by a number of factors including issues of Confidence (do not trust a vaccine or a provider), Complacency (do not perceive a need for a vaccine or do not value the vaccine), and Convenience (access),” also known as the “three Cs” (28). While this study's intent was not to assess vaccine hesitancy, we nevertheless identified themes specific to vaccine decision-making that parallel those raised by individuals who historically expressed hesitancy. Issues related to confidence emerged as discussions of safety or efficacy and concerns regarding the speed in which the vaccine was created with limited information. Complacency materialized across caregiver beliefs that children will not get COVID-19 or will have less severe disease. Convenience manifested in comments specific to logistics, access, and barriers to vaccine availability and administration. Understanding how caregiver perceptions of the COVID-19 vaccine intersect the “three Cs” WHO model can help inform clinical strategies to navigate challenging conversations with families and guide public health messaging. Recent publications have emerged addressing the importance of dynamic public health communication strategies to aid vaccination uptake (54).

This study has several limitations. Certain demographics were not included in survey questions to ensure anonymity. As a result, details on participant gender, age, child age, and relationship to the patient with childhood cancer are unknown. These findings represent the perspectives of those who provided narrative responses, comprising 29% of survey respondents; sample bias may influence findings if participants who shared written responses represent outlier perspectives. However, content analysis of narrative responses indicated a bell curve of opinions, suggesting our findings represent a cross-section of caregivers. Notably, with respect to demographic information collected, qualitative respondents had similar demographics compared to those who opted not to provide free-text responses. The survey techniques relied heavily on internet and social media participation, which risks selection bias with respondents not necessarily representative of all caregivers in their respective countries. Further, survey data skewed toward responses from high income settings; this may reflect varying levels of literacy worldwide as well as unavailability of the survey in languages other than English or Spanish. Findings likely represent a subset of opinions, and further investigations in broader languages and low-income countries are needed. Regardless of commonalities across global responses, conversations must be individualized to the setting and situation. Despite known increased risk with SARS-CoV-2 amongst children with cancer (8), disparate global recommendations exist for childhood vaccinations. Each country has its own standards, with vaccine expansion to younger children or vulnerable populations occurring at different times since the advent of SARS-CoV-2 (55). Finally, we do not know the willingness of respondents to vaccinate themselves, which has been shown to influence perspectives on childhood vaccination (23), or their intent in vaccinating their children, all of which may influence their responses.

In summary, this global study examines the perspectives of caregivers of children with cancer on COVID-19 vaccines and provides insights to guide clinicians in counseling families and providing targeted information to support decision-making. It corroborates findings from the general pediatric population worldwide, with safety and effectiveness, logistics, and limitations in information driving questions and concerns around vaccine uptake and therefore important elements of vaccine counseling. These findings reveal the complexity and multidimensionality of perspectives on COVID-19 vaccination and highlight the interrelated nature of themes. This can help with further development of focused survey tools aimed at understanding attitudes to vaccines amongst the pediatric oncology community. We hope these data may contribute to clinical support tools and public health messaging to help healthcare professionals address vaccine hesitancy and refusal in the context of the COVID-19 vaccine and future novel immunizations for pediatric populations. Further research evaluating how caregiver perspectives influence actual vaccine uptake is needed to guide healthcare professionals in targeting efforts toward supporting medically vulnerable children and their families.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for this study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital (SJCRH) and International Society of Paediatric Oncology (SIOP) Parent and Carer Advisory Group

Members of the COVID-19 and Childhood Cancer Vaccine Global Parent and Carer Advisory Group as below contributed to the concept for this study and to the evaluation of its findings:

• Brian Regan, Dana Farber/Boston Children's Pediatric Patient/Family Advisory Committee, United States

• Meghan Shea, Dana Farber/Boston Children's Pediatric Patient/Family Advisory Committee, United States

• Julie Chessell, AC20RN, Canada

• Kim Buff, Momcology, United States

• Carmen Auste, Childhood Cancer International, Philippines

• Pinta Manullang-Panggabean, Yayasan Anyo Indonesia, Indonesia

• Poonam Bagai, Can Kids India, India

• John Ahenkorah, Ghana Parents Group, Ghana

Author contributions

JB and JG worked to conceptualize and complete data collection for the study. EK led development of the research methodology. JG and AS led the formal analysis and investigation of data. AS wrote the original draft of the paper supervised by EK. All authors revised the paper critically and approved the final version.

Funding

This study was supported by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC)/St. Jude Children's Research Hospital (SJCRH). The funder/sponsor did not participate in the work.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the caregivers who shared their insight and time by completing the survey. We would also like to thank all those who helped to disseminate the survey globally. We specifically thank Dr. Jose Luis Copado (Pediatric Infectious Diseases Specialist, Mexico) for translating the survey into Spanish. We thank Prof. Kathy Pritchard-Jones, president of SIOP, for encouragement to address this important topic at a global level, and Dr. Carlos Rodriguez-Galindo, for the support of St. Jude Global Alliance. Finally, we wish to acknowledge the contributions of Dr. Miguela Caniza and Maysam Homsi as members of the COVID-19 Vaccine Working Group collaboration between SJCRH and SIOP which has led to this work.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1004263/full#supplementary-material

References

1. McAteer J, Yildirim I, Chahroudi A. The vaccines act: deciphering vaccine hesitancy in the time of COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis. (2020) 71:703–5. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa433

2. World Health Organization. Ten Threats to Global Health in 2019. (2019). Available online at: https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019 (accessed December 12, 2021).

3. Bagateli LE, Saeki EY, Fadda M, Agostoni C, Marchisio P, Milani GP. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among parents of children and adolescents living in Brazil. Vaccines. (2021) 9:1115. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9101115

4. Temsah MH, Alhuzaimi AN, Aljamaan F, Bahkali F, Al-Eyadhy A, Alrabiaah A, et al. Parental attitudes and hesitancy about COVID-19 vs. routine childhood vaccinations: a national survey. Front Public Health. (2021) 9:752323. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.752323

5. Xu Y, Xu D, Luo L, Ma F, Wang P, Li H, et al. A cross-sectional survey on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among parents from Shandong vs. Zhejiang. Front Public Health. (2021) 9:779720. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.779720

6. Zona S, Partesotti S, Bergomi A, Rosafio C, Antodaro F, Esposito S. Anti-COVID vaccination for adolescents: a survey on determinants of vaccine parental hesitancy. Vaccines. (2021) 9:1309. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9111309

7. Dong Y, Mo X, Hu Y, Qi X, Jiang F, Jiang Z, et al. Epidemiology of COVID-19 among children in China. Pediatrics. (2020) 145:e20200702. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0702

8. Mukkada S, Bhakta N, Chantada GL, Chen Y, Vedaraju Y, Faughnan L, et al. Global characteristics and outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infection in children and adolescents with cancer (GRCCC): a cohort study. Lancet Oncol. (2021) 22:1416–26. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00454-X

9. Meena JP, Kumar Gupta A, Tanwar P, Ram Jat K, Mohan Pandey R, Seth R. Clinical presentations and outcomes of children with cancer and COVID-19: a systematic review. Pediatr Blood Cancer. (2021) 68:e29005. doi: 10.1002/pbc.29005

10. Kahn AR, Schwalm CM, Wolfson JA, Levine JM, Johnston EE. COVID-19 in children with cancer. Curr Oncol Rep. (2022) 24:295–302. doi: 10.1007/s11912-022-01207-1

11. Di Pietro ML, Poscia A, Teleman AA, Maged D, Ricciardi W. Vaccine hesitancy: parental, professional and public responsibility. Ann Ist Super Sanita. (2017) 53:157–62. doi: 10.4415/ANN_17_02_13

12. Fisher KA, Bloomstone SJ, Walder J, Crawford S, Fouayzi H, Mazor KM. Attitudes toward a potential SARS-CoV-2 vaccine : a survey of U.S. adults. Ann Intern Med. (2020) 173:964–73. doi: 10.7326/M20-3569

13. Jennings W, Stoker G, Bunting H, Valgarðsson VO, Gaskell J, Devine D, et al. Lack of trust, conspiracy beliefs, and social media use predict COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Vaccines. (2021) 9:593. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9060593

14. Neumann-Böhme S, Varghese NE, Sabat I, Barros PP, Brouwer W, van Exel J, et al. Once we have it, will we use it? A European survey on willingness to be vaccinated against COVID-19. Eur J Health Econ. (2020) 21:977–82. doi: 10.1007/s10198-020-01208-6

15. Reiter PL, Pennell ML, Katz ML. Acceptability of a COVID-19 vaccine among adults in the United States: how many people would get vaccinated? Vaccine. (2020) 38:6500–7. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.08.043

16. Seale H, Heywood AE, Leask J, Sheel M, Thomas S, Durrheim DN, et al. COVID-19 is rapidly changing: examining public perceptions and behaviors in response to this evolving pandemic. PLoS ONE. (2020) 15:e0235112. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0235112

17. Wong LP, Alias H, Danaee M, Ahmed J, Lachyan A, Cai CZ, et al. COVID-19 vaccination intention and vaccine characteristics influencing vaccination acceptance: a global survey of 17 countries. Infect Dis Poverty. (2021) 10:122. doi: 10.1186/s40249-021-00900-w

18. Montalti M, Rallo F, Guaraldi F, Bartoli L, Po G, Stillo M, et al. Would parents get their children vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2? Rate and predictors of vaccine hesitancy according to a survey over 5000 families from Bologna, Italy. Vaccines. (2021) 9. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9040366

19. Skjefte M, Ngirbabul M, Akeju O, Escudero D, Hernandez-Diaz S, Wyszynski DF, et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among pregnant women and mothers of young children: results of a survey in 16 countries. Eur J Epidemiol. (2021) 36:197–211. doi: 10.1007/s10654-021-00728-6

20. Szilagyi PG, Shah MD, Delgado JR, Thomas K, Vizueta N, Cui Y, et al. Parents' intentions and perceptions about COVID-19 vaccination for their children: results from a national survey. Pediatrics. (2021) 148:e2021052335. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-052335

21. Teasdale CA, Borrell LN, Kimball S, Rinke ML, Rane M, Fleary SA, et al. Plans to vaccinate children for coronavirus disease 2019: a survey of United States parents. J Pediatr. (2021) 237:292–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.07.021

22. Yigit M, Ozkaya-Parlakay A, Senel E. Evaluation of COVID-19 vaccine refusal in parents. Pediatr Infect Dis J. (2021) 40:e134–6. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000003042

23. Yilmaz M, Sahin MK. Parents' willingness and attitudes concerning the COVID-19 vaccine: a cross-sectional study. Int J Clin Pract. (2021) 75:e14364. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.14364

24. Alfieri NL, Kusma JD, Heard-Garris N, Davis MM, Golbeck E, Barrera L, et al. Parental COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy for children: vulnerability in an urban hotspot. BMC Public Health. (2021) 21:1662. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11725-5

25. Wang Q, Xiu S, Zhao S, Wang J, Han Y, Dong S, et al. Vaccine hesitancy: COVID-19 and influenza vaccine willingness among parents in Wuxi, China-a cross-sectional study. Vaccines. (2021) 9:342. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1989914

26. Goldman RD, Yan TD, Seiler M, Parra Cotanda C, Brown JC, Klein EJ, et al. Caregiver willingness to vaccinate their children against COVID-19: cross sectional survey. Vaccine. (2020) 38:7668–73. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.09.084

27. Wimberly CE, Towry L, Davis E, Johnston EE, Walsh KM. SARS-CoV-2 vaccine acceptability among caregivers of childhood cancer survivors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. (2021) 2021:e29443. doi: 10.1002/pbc.28943

28. World Health Organization. What Influences Vaccine Acceptance: A Model of Determinants of Vaccine Hesitancy. (2013). Available online at: https://www.who.int/immunization/sage/meetings/2013/april/1_Model_analyze_driversofvaccineConfidence_22_March.pdf (accessed December 14, 2021).

29. St. Jude Global. COVID-19 and Childhood Cancer Vaccine Working Group. (2021). Available online at: https://global.stjude.org/en-us/global-covid-19-observatory-and-resource-center-for-childhood-cancer/vaccine-working-group.html (accessed December 12, 2021).

30. Caniza MA, Homsi MR, Bate J, Adrizain R, Ahmed T, Alexander S, et al. Answers to common questions about COVID-19 vaccines in children with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. (2022) 69:e29985. doi: 10.1002/pbc.29985

31. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. (2007) 19:349–57. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

32. Krippendorff K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE (2004).

33. Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res. (2007) 42:1758–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x

34. Gumy JM, Silverstein A, Kaye EC, Caniza MA, Homsi MR, Pritchard-Jones K, et al. Global caregiver concerns of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in children with cancer: a cross-sectional mixed-methods study. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. (2022) 1–11. doi: 10.1080/08880018.2022.2101724

35. Teasdale CA, Borrell LN, Shen Y, Kimball S, Rinke ML, Fleary SA, et al. Parental plans to vaccinate children for COVID-19 in New York city. Vaccine. (2021) 39:5082–6. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.07.058

36. Teherani M, Banskota S, Camacho-Gonzalez A, Smith AGC, Anderson EJ, Kao CM, et al. Intent to vaccinate SARS-CoV-2 infected children in US households: a survey. Vaccines. (2021) 9:1049. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9091049

37. Centers for Disease Control Prevention. Understanding mRNA COVID-19 Vaccines. (2022). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/different-vaccines/mrna.html (accessed January 4, 2022).

38. World Health Organization. Vaccine Safety Basics: Learning Manual. (2013). Available online at: https://www.who.int/vaccine_safety/initiative/tech_support/Part-1.pdf

39. Bell S, Clarke R, Mounier-Jack S, Walker JL, Paterson P. Parents' and guardians' views on the acceptability of a future COVID-19 vaccine: a multi-methods study in England. Vaccine. (2020) 38:7789–98. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.10.027

40. Aw J, Seng JJB, Seah SSY, Low LL. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy-a scoping review of literature in high-income countries. Vaccines. (2021) 9:900. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9080900

41. Cesaro S, Giacchino M, Fioredda F, Barone A, Battisti L, Bezzio S, et al. Guidelines on vaccinations in paediatric haematology and oncology patients. Biomed Res Int. (2014) 2014:707691. doi: 10.1155/2014/707691

42. Cordonnier C, Einarsdottir S, Cesaro S, Di Blasi R, Mikulska M, Rieger C, et al. Vaccination of haemopoietic stem cell transplant recipients: guidelines of the 2017 European Conference on Infections in Leukaemia (ECIL 7). Lancet Infect Dis. (2019) 19:e200–12. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30600-5

43. Top KA, Vaudry W, Morris SK, Pham-Huy A, Pernica JM, Tapiéro B, et al. Waning vaccine immunity and vaccination responses in children treated for acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a Canadian immunization research network study. Clin Infect Dis. (2020) 71:e439–48. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa163

44. Cavanna L, Citterio C, Toscani I. COVID-19 vaccines in cancer patients. Seropositivity and safety. Systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccines. (2021) 9:1048. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9091048

45. Herishanu Y, Avivi I, Aharon A, Shefer G, Levi S, Bronstein Y, et al. Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. (2021) 137:3165–73. doi: 10.1182/blood.2021011568

46. Iacono D, Cerbone L, Palombi L, Cavalieri E, Sperduti I, Cocchiara RA, et al. Serological response to COVID-19 vaccination in patients with cancer older than 80 years. J Geriatr Oncol. (2021) 12:1253–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2021.06.002

47. Massarweh A, Eliakim-Raz N, Stemmer A, Levy-Barda A, Yust-Katz S, Zer A, et al. Evaluation of seropositivity following BNT162b2 messenger RNA vaccination for SARS-CoV-2 in patients undergoing treatment for cancer. JAMA Oncol. (2021) 7:1133–40. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.2155

48. Monin L, Laing AG, Muñoz-Ruiz M, McKenzie DR, Del Molino Del Barrio I, Alaguthurai T, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of one versus two doses of the COVID-19 vaccine BNT162b2 for patients with cancer: interim analysis of a prospective observational study. Lancet Oncol. (2021) 22:765–78. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00213-8

49. Pimpinelli F, Marchesi F, Piaggio G, Giannarelli D, Papa E, Falcucci P, et al. Fifth-week immunogenicity and safety of anti-SARS-CoV-2 BNT162b2 vaccine in patients with multiple myeloma and myeloproliferative malignancies on active treatment: preliminary data from a single institution. J Hematol Oncol. (2021) 14:81. doi: 10.1186/s13045-021-01090-6

50. Thakkar A, Gonzalez-Lugo JD, Goradia N, Gali R, Shapiro LC, Pradhan K, et al. Seroconversion rates following COVID-19 vaccination among patients with cancer. Cancer Cell. (2021) 39:1081–90.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2021.06.002

51. Waissengrin B, Agbarya A, Safadi E, Padova H, Wolf I. Short-term safety of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in patients with cancer treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Lancet Oncol. (2021) 22:581–3. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00155-8

52. Marquez RR, Gosnell ES, Thikkurissy S, Schwartz SB, Cully JL. Caregiver acceptance of an anticipated COVID-19 vaccination. J Am Dent Assoc. (2021) 152:730–9. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2021.03.004

53. Dunn J, Steginga SK, Rosoman N, Millichap D. A review of peer support in the context of cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol. (2003) 21:55–67. doi: 10.1300/J077v21n02_04

54. Omer SB, Benjamin RM, Brewer NT, Buttenheim AM, Callaghan T, Caplan A, et al. Promoting COVID-19 vaccine acceptance: recommendations from the Lancet Commission on Vaccine Refusal, Acceptance, and Demand in the USA. Lancet. (2021) 398:2186–92. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02507-1

55. Fox K. CNN. The Countries That Are Vaccinating Children Against Covid-19. Available online at: https://www.cnn.com/2021/09/17/world/covid-vaccine-children-countries-intl-cmd/index.html (accessed September 17, 2021).

Keywords: pediatric oncology, SARS-CoV-2, immunization, global health, public health

Citation: Silverstein A, Gumy JM, Bate J and Kaye EC (2023) Global caregiver perspectives on COVID-19 immunization in childhood cancer: A qualitative study. Front. Public Health 11:1004263. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1004263

Received: 27 July 2022; Accepted: 06 February 2023;

Published: 07 March 2023.

Edited by:

Jagdish Chandra, ESIC Model Hospital and PGIMSR, IndiaReviewed by:

Mariana Kruger, Stellenbosch University, South AfricaG. P. Prashanth, National University of Science and Technology, Oman

Copyright © 2023 Silverstein, Gumy, Bate and Kaye. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Erica C. Kaye, ZXJpY2Eua2F5ZUBzdGp1ZGUub3Jn

†ORCID: Allison Silverstein orcid.org/0000-0003-4188-8424

Erica C. Kaye orcid.org/0000-0002-6522-3876

Allison Silverstein

Allison Silverstein Julia M. Gumy

Julia M. Gumy Jessica Bate

Jessica Bate Erica C. Kaye

Erica C. Kaye