94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Public Health, 10 October 2022

Sec. Public Health Education and Promotion

Volume 10 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.998710

This article is part of the Research TopicAging and Chronic Disease: Public Health Challenge and Education ReformView all 37 articles

Kexin Zhang1,2†

Kexin Zhang1,2† Chengxia Kan1,2†

Chengxia Kan1,2† Youhong Luo1,2

Youhong Luo1,2 Hongwei Song1,2

Hongwei Song1,2 Zhenghui Tian2

Zhenghui Tian2 Wenli Ding2,3

Wenli Ding2,3 Linfei Xu2,3

Linfei Xu2,3 Fang Han2,3*

Fang Han2,3* Ningning Hou1,2*

Ningning Hou1,2*We have entered an era of population aging, and many public health problems associated with aging are becoming more serious. Older adults have earlier onset of chronic diseases and suffer more disability. Therefore, it is extremely important to promote active aging and enhance health literacy. These involves full consideration of the need for education and the provision of solutions to problems associated with aging. The development of OAE is an important measure for implementing the strategy of active aging, and curriculum construction is a fundamental component of achieving OAE. Various subjective and objective factors have limited the development of OAE. To overcome these difficulties and ensure both active and healthy aging, the requirements for active aging should be implemented, the limitations of current OAE should be addressed, system integration should be increased, and the curriculum system should be improved. These approaches will help to achieve the goal of active aging. This paper discusses OAE from the perspective of active aging, based on the promotion of health literacy and provides suggestions to protect physical and mental health among older adults, while promoting their social participation. The provision of various social guarantees for normal life in older adults is a new educational concept.

The world's population is aging rapidly, and older adults are expected to live longer (Table 1) (1–3). Over the last few decades, population trends indicate earlier onset of many chronic diseases and an increased incidence of multimorbidity in older adults (4, 5). As these problems emerge, older adults may experience more disability and worse quality of life (6). Discussions of population aging and its effects have become an important and popular topic. In the context of population aging, the role of older adult education (OAE) has become increasingly prominent. Although there have been many studies of OAE, there is minimal available information concerning OAE with a focus on active aging. In this review, we analyze the current status of OAE in the context of active aging and propose measures for reforming OAE. We also aim to increase investment in OAE, ensure greater focus on older adults, and promote active aging.

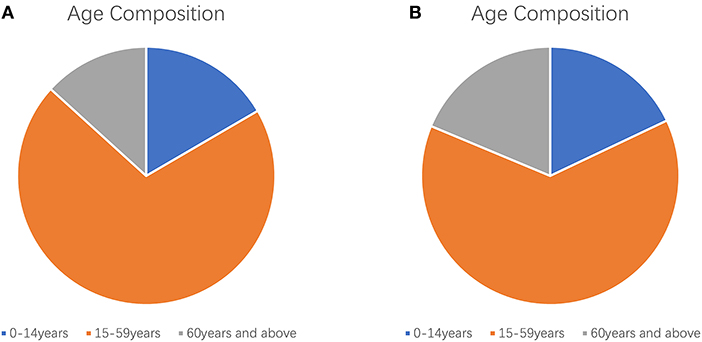

We define aging (also known as senescence) as the intrinsic physiological decline that occurs as an organism ages, leading to decreased fertility and reproduction, as well as increased risks of age-related morbidity and mortality (7). In the past 20 years, the world's older population has increased (Figures 1, 2). For example, the Seventh National Census of China had a greater proportion of people aged ≥60 years, compared with the Sixth National Census (Figure 3); the proportion of people aged ≥60 years increased by 5.44% (Data from http://www.stats.gov.cn/).

Figure 3. Age composition of the Chinese census. (A) Age composition of the sixth national census of China; (B) Age composition of the seventh national census of China.

In this context, the concepts of “successful aging” (8, 9), “healthy aging” (10, 11), and “active aging” (12, 13) have been introduced to reflect positive responses to aging in various countries worldwide. The concept of successful aging was introduced as early as the 1960s. Its connotations include the need for older adults to maintain mental health and normal cognitive function, be socially active, have good interpersonal relationships, and be physically healthy (8, 14, 15). Healthy aging was introduced by the World Health Organization; its core concepts include physical health, mental health, and good social adjustment. Active aging is another level of healthy aging (10). Notably, active aging was defined in 2002 by the World Health Organization as the process of gaining access to the greatest possible variety of opportunities for health, participation, and security, with the goal of improving the quality of life in older adults (16–19). The concept of active aging includes the concepts of “healthy aging” (11), “successful aging” (9), and “productive aging” (20); it also has a more systematic and comprehensive core meaning. Over the past two decades, the concept of active aging has been applied to social, scientific, psychological, and medical disciplines. Active aging is regarded by international political groups and researchers as an important component of efforts to address the challenges of population aging (21). Active aging now highlights the need for a population aging approach that involves physical, social, and mental health, while encouraging social participation and providing adequate protection, security, and care based on the needs of older adults (22). Thus, active aging is an effective response to the experience of aging. An important challenge for the current aging society comprises the optimization of active aging to enhance survival and development among older adults, promote their social participation and overall development, and improve their standard of living.

Population aging is a global phenomenon that requires action to promote well-being and prevent disease (23). OAE is an informal component of adult education and the final stage of lifelong education (24). With the increasing problem of aging, the retired older population is also increasing and has become a social group that cannot be ignored. The OAE in this article is education for retired seniors 60 years and older and those who are not working. The development of OAE is essential for developing the careers of older adults and improving their participation; it is also an important initiative for actively managing population aging, modernizing education, and promoting lifelong learning.

OAE has a long history of development; its definition and content vary according to the physical and mental characteristics, needs, and preferences of older adults. In the past, the range of courses offered in OAE was limited and focused only on the interests of older adults, such as calligraphy, painting, instrumental music and dance (24). Recently, because of the emphasis on active aging, the curriculum has focused on the physical and mental health of older adults and included some new skills knowledge (e.g., computer networks, mobile phones, and computer use) (25). These changes continue to enrich OAE. This review of OAE focused on studies of older adults entering retirement; it was written with the goal of improving their physical and mental health, promoting their social participation, and providing them with various safeguards for normal life through the delivery of OAE.

OAE emerged as a new type of education in the 1970s, and it developed as one of the positive responses to the aging of the world (26). OAE is for seniors 60 years and older who are retired or have plenty of leisure time. OAE can enrich the lives of older adults and enhance their quality of life. Moreover, OAE can fully use the older adults' strengths and create a “society of learners” by influencing the people around them with practical actions. The essential features of the “society of learners” are universal and lifelong learning. “Society of learners” is a basic form of future society. And senior education, as an essential part of the last stage of lifelong education, is of great significance in building and improving a harmonious and continuously developing “society of learners”. Finally and most importantly, OAE can help older adults improve their health literacy and achieve prevention and monitoring of diseases.

Currently, there are several problems with OAE that hinder the achievement of active aging. The lack of educational opportunities and resources partially limits the development of OAE. Additionally, low motivation to participate in education exacerbates the problems in the development of OAE; this prevents it from rapidly achieving better integration into the new contemporary environment. Finally, limitations of the educational model and a lack of professional staff also hinder the development of OAE. There is a need for efforts to address the current problems in the development of OAE and actively promote educational exploration through the optimization of existing educational strategies. The specific limitations of OAE in the context of active aging are as follows (Table 2).

There is a serious imbalance throughout the OAE developmental process (27).

Few countries have focused on developing OAE universities, but the establishment and development of OAE in China are clearer. OAE universities were established first in 1983. By the end of 2019, there were more than 62,000 OAE universities with more than 8 million students in China. The OAE universities in China refer specifically to universities, colleges, schools and institutions that conduct OAE and are organized or supported by the government, enterprises or social organizations. There were more than 250 million people over the age of 60 in China, and only 5% of them were older students, indicating that there was a big gap between the existing scale of OAE education and the participation rate of older people in education under active aging (28). First, OAE is achieved through the vehicle of the OAE universities (24). OAE universities are places for retired seniors to relax, have fun, study and make friends, mainly to promote senior health; they focus on the learning, well-being, and quality of life of older adults to ensure their healthy development. The OAE universities that currently exist are insufficient for the large population of older adults. Second, OAE in the context of active aging has been discussed at the academic level by many experts and researchers, and it has been implemented in some regions; however, it has not been sufficiently promoted in terms of publicity (29). Furthermore, older adults, as the recipients of OAE, are not fully aware of the concept of “lifelong learning” and the importance of participating in OAE; they do not realize the vital role of OAE in improving health literacy, relieving anxiety, and benefiting their own development (particularly their social development). Finally, despite the global digitalization process, older adults have a limited acceptance of information and network technologies, applications, and innovation capabilities; the existence of a “digital divide” hinders active aging (30).

The most common and effective teaching model is face-to-face interaction with accessible communication and timely communication. This model is also applicable to OAE. However, the limited audiences in this model reduce its usefulness (31). The current coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic is an unprecedented situation that has affected all aspects of society, including education; the implementation of face-to-face courses has also been profoundly affected (31, 32). Complete reliance on face-to-face instruction for OAE will affect the speed of teaching and learning, as well as the participation and motivation of learners. Thus, when establishing the teaching model for OAE, there is a need to consider learning ability, physical fitness, and basic health in older adults (24). Educational efforts should focus on maintaining effectiveness while avoiding negative effects on quality of life and health among older adults. However, because of the unique nature of OAE, the knowledge base and comprehension of each older adult learner varies considerably (33); traditional teaching methods cannot be applied to OAE. Currently, most regional OAE institutions use the university education model, without considering the life and educational statuses of older adults; this reduces the effectiveness of OAE and does not support long-term implementation of OAE.

The lack of quality courses for older adult learners continues to be a major barrier to the growth of OAE (24). There is a lack of uniformity and standardization in the curriculum setting of OAE universities, and there are problems such as scarce quantity, scattered topics and uneven quality of courses. The textbooks generally lack the characteristics of OAE education, and they are presented in a single form, with little practicality and low utilization. In China, the curriculum structure is aging, textbooks do not appropriately reflect the educational characteristics of older adults, and > 56% of students believe that textbooks should be more advanced and practical (34). Other countries have similar problems. In Korea, OAE is not limited to general courses; there have been suggestions of additional courses concerning the social welfare system, health and healthcare, civics, and the economy (35). In Peru, the existing curriculum does not meet the real needs of students from a wide range of educational backgrounds (33); few universities have academic educational programs for older adults (33).

The content of the current OAE courses does not focus exclusively on recipients themselves. There is considerable scope to develop OAE courses on health literacy (24). The world's population is aging rapidly, multimorbidity is prevalent among older adults, and older adults are prone to psychological problems that can lead to depression after retirement owing to changes in social status. Therefore, OAE should focus on improving health literacy and protecting the mental health and physical well-being of older adults. In this context, health literacy comprises the ability to find, understand, use, and evaluate health-related information; such an ability is a critical determinant of health (36, 37). As an example of the need for improved health literacy, in December 2009, the Chinese Ministry of Health published the results of the first official health literacy survey involving Chinese residents; only 3.81% of adults aged 65–69 years had adequate health literacy, which was the lowest level among all surveyed age groups (38). In the context of population aging, chronic non-communicable diseases have created a heavy disease burden worldwide; there is increasing multimorbidity, which constitutes a serious threat to safety and quality of life among older adults (38). Additionally, there is a need to monitor psychological disorders; the fast-paced nature of modern life makes it difficult for younger adults to closely observe psychological changes in older adults. Some studies have shown that anxiety disorders are more common in later life; there is some evidence that anxiety disorders are associated with lower levels of education (39). Grossman's theory of health production suggests that health is influenced by healthcare, income level, lifestyle, education level, and living environment (40). There is a close link between an individual's education level and their health (41, 42). Improvements in education level are needed to promote health in older adults (43). Health-related courses should be included to create a high-quality curriculum.

Active aging represents a major strategic initiative to address aging-related problems. OAE provides reliable conditions for implementing the active aging strategy and a strong incentive to promote active aging. The attainment of a healthy aging society requires efforts to prepare for the challenges and problems associated with rapid population aging (44). In the following three sections, recommendations are provided for improvements to OAE (Table 2).

OAE universities are intended to maintain physical autonomy and independence in older adults by providing learning opportunities, recreation, and social activities that can enhance their quality of life (45). OAE universities serve as the main avenues for educating older adults. The development and improvement of OAE can support healthy aging (46). First, more educated older adults have higher health literacy, so there is a positive correlation between OAE and health literacy; such education is associated with better health and survival (37). Second, higher levels of education help individuals to build psychosocial resources; increased education can prevent cognitive impairment in older adults (47). Third, people with higher levels of education are more likely to adopt positive health behaviors, compared with people who have lower levels of education; in this context, positive health behaviors include regular exercise, moderate alcohol consumption, and avoidance of smoking. All three of these behaviors are associated with better health and a lower mortality rate (48).

Education can help older adults maintain their independence, preserve their dignity, and have a positive attitude toward aging. It is important to promote active aging through education (49, 50). However, the current lack of outreach capacity and insufficient supply of OAE are problems that continue to restrict the development of OAE. To increase the motivation of older adults to participate in OAE (40), countries should formulate a series of support strategies for developing OAE according to national conditions; such strategies will enable OAE to be fully valued by older adults. The promotion of OAE involves broadening channels, increase government investment in OAE at all levels, introduce social capital, and use internet resources and television news for publicity. Additionally, OAE services should be directly accessible through the community. Communities and senior activity centers can hold offline experience courses and lectures to raise awareness of OAE among older adults.

Unlike other forms of education, OAE has flexibility in terms of educational content and form, as well as diverse educational objectives and unique information; these characteristics determine the diversity of OAE models (24). First, face-to-face courses can be improved; for example, teaching sites can be established in homes or community organizations to facilitate participation by older adults who live in nearby communities and have limited mobility. In Japan, small and community-based learning opportunities have been popular; they remain active (25). Second, online teaching support can be provided for OAE. Online teaching is convenient and fast, not limited by time and space, and requires only a mobile phone or a computer. The development of online courses can offset the limitations of traditional forms of education (51). Additionally, a mixed online and offline teaching model is the focus of active exploration (52); joint instruction that involves OAE universities and local colleges can be developed to introduce quality courses of interest to older adults, while enhancing the delivery of educational content. Finally, mutual learning can be promoted, which involves a shift in learner and teacher roles (25). Members of OAE universities could invite members of other classes to discuss what they have learned in past courses (25).

High-quality curriculum is an essential component of OAE, which determines the quality of education (24). The first step in creating a high-quality curriculum involves the improvement of content for older adults. Because health maintenance is a critical consideration for older adults, most OAE courses should include concepts that help to promote health in their learners (25). First, this focus requires the public health system to provide programs that invest in the long-term prevention of chronic diseases and promote health recovery for all learners in OAE universities (53). Second, health literacy science and mental health education courses should be offered because a positive mindset and a good lifestyle are essential for active aging (54). These courses should include lectures to disseminate specific knowledge concerning the prevention of chronic diseases and cancer (i.e., basics of disease prevention), encouragement of healthy lifestyle maintenance with a sensible diet, moderate exercise, smoking cessation, alcohol restriction, and psychological balance; and promotion of healthy aging through appropriate physical activity classes (55). Online classes should be conducted to improve medication-related knowledge in older adults, which can help them to use medications more safely (56). Furthermore, health behavior assessments should regularly be conducted at OAE universities; these will enable early detection, treatment, and management of diseases. Health behavior assessments include evaluation of smoking status, alcohol consumption, and physical activity, as well as health screening and body mass index calculation; together with dietary habits, these components are regarded as basic health behaviors (38). Based on these evidences, we suggest that OAE universities should develop a systematic psychological education curriculum for older adults. They should also contact mental health education experts or authoritative psychological counselors to deliver mental health knowledge through lectures. OAE universities should arrange professional assessments of mental health in older adults. When appropriate, efforts should be made to communicate with the family members of older adults (by phone or in person) to ensure that younger adults understand the psychological changes in their older family members. Older adults should receive warm and caring support; professional counselors should be available for early intervention and treatment when serious problems are identified.

Population aging is a growing problem; active and effective management of this problem is urgently needed. The development of OAE is a long-term process; it is inevitable that various bottlenecks will occur during the development process, which requires systematic coordination. Governments and authorities at all levels should create conditions for participation, while actively regulating and guiding the development of OAE. They should also expand curriculum reform, strive to improve educational quality, and make full use of existing educational resources to effectively alleviate the contradiction between supply and demand in OAE. Professionals should carefully monitor the physical and mental health of older adults; families should provide as much companionship and care as possible; and older adults themselves should improve their health literacy and actively participate in the learning process. The investment of robust effort to support older adults, particularly with respect to OAE, is an important aspect of promoting balanced development of society overall.

FH and NH: conceptualization and writing—review and editing. KZ and CK: methodology, software, visualization, and writing—original draft. YL, HS, ZT, WD, and LX: methodology and writing—review. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This study was supported by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (81870593 and 82170865), Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2020MH106), Shandong Province Higher Educational Science and Technology Program for Youth Innovation (2020KJL004), and Yuandu scholars (2021).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Christensen K, Doblhammer G, Rau R, Vaupel JW. Ageing populations: the challenges ahead. Lancet. (2009) 374:1196–208. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61460-4

2. Lubitz J, Cai L, Kramarow E, Lentzner H. Health, life expectancy, and health care spending among the elderly. N Engl J Med. (2003) 349:1048–55. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa020614

3. Fernandes A, Forte T, Santinha G, Diogo S, Alves F. Active aging governance and challenges at the local level. Geriatrics (Basel). (2021) 6:64. doi: 10.3390/geriatrics6030064

4. Wister A, Cosco T, Mitchell B, Fyffe I. Health behaviors and multimorbidity resilience among older adults using the Canadian longitudinal study on aging. Int Psychogeriatr. (2020) 32:119–33. doi: 10.1017/S1041610219000486

5. Dhalwani NN, O'Donovan G, Zaccardi F, Hamer M, Yates T, Davies M, et al. Long terms trends of multimorbidity and association with physical activity in older English population. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. (2016) 13:8. doi: 10.1186/s12966-016-0330-9

6. Friedman SM. Lifestyle (Medicine) and Healthy Aging. Clin Geriatr Med. (2020) 36:645–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2020.06.007

7. McCune S, Promislow D. Healthy, active aging for people and dogs. Front Vet Sci. (2021) 8:655191. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.655191

8. Chi YC, Wu CL, Liu HT. Effect of a multi-disciplinary active aging intervention among community elders. Medicine (Baltimore). (2021) 100:e28314. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000028314

9. Estebsari F, Dastoorpoor M, Khalifehkandi ZR, Nouri A, Mostafaei D, Hosseini M, et al. The concept of successful aging: a review article. Curr Aging Sci. (2020) 13:4–10. doi: 10.2174/1874609812666191023130117

10. Cosco TD, Howse K, Brayne C. Healthy ageing, resilience and wellbeing. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. (2017) 26:579–83. doi: 10.1017/S2045796017000324

11. Rudnicka E, Napierała P, Podfigurna A, Meczekalski B, Smolarczyk R, Grymowicz M. The world health organization (WHO) approach to healthy ageing. Maturitas. (2020) 139:6–11. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2020.05.018

12. Bélanger E, Ahmed T, Filiatrault J, Yu HT, Zunzunegui MV. An empirical comparison of different models of active aging in Canada: the international mobility in aging study. Gerontologist. (2017) 57:197–205. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnv126

13. Paúl C, Teixeira L, Ribeiro O. Active aging in very old age and the relevance of psychological aspects. Front Med (Lausanne). (2017) 4:181. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2017.00181

14. Garfein AJ, Herzog AR. Robust aging among the young-old, old-old, and oldest-old. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. (1995) 50:S77–87. doi: 10.1093/geronb/50B.2.S77

15. von Faber M, Bootsma-van der Wiel A, van Exel E, Gussekloo J, Lagaay AM, van Dongen, et al. Successful aging in the oldest old: who can be characterized as successfully aged. Arch Intern Med. (2001) 161:2694–700. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.22.2694

16. Arpino B, Solé-Auró A. Education inequalities in health among older european men and women: the role of active aging. J Aging Health. (2019) 31:185–208. doi: 10.1177/0898264317726390

17. Vázquez FL, Otero P, García-Casal JA, Blanco V, Torres ÁJ, Arrojo M. Efficacy of video game-based interventions for active aging. A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. (2018) 13:e0208192. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0208192

18. Ko PC, Yeung WJ. An ecological framework for active aging in China. J Aging Health. (2018) 30:1642–76. doi: 10.1177/0898264318795564

19. Boudiny K. 'Active ageing': from empty rhetoric to effective policy tool. Ageing Soc. (2013) 33:1077–98. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X1200030X

20. Ko PC, Yeung WJ. Contextualizing productive aging in Asia: definitions, determinants, and health implications. Soc Sci Med. (2019) 229:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.01.016

21. Jensen PH, Skjøtt-Larsen J. Theoretical challenges and social inequalities in active ageing. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:9156. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18179156

22. Tiraphat S, Kasemsup V, Buntup D, Munisamy M, Nguyen TH, Hpone Myint A. Active aging in ASEAN countries: influences from age-friendly environments, lifestyles, and socio-demographic factors. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:8290. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18168290

23. Souza EM, Silva D, Barros AS. Popular education, health promotion and active aging: an integrative literature review. Cien Saude Colet. (2021) 26:1355–68. doi: 10.1590/1413-81232021264.09642019

24. Cai J, Michitaka K. Learner-engaged curriculum co-development in older adult education: lessons learned from the universities for older adults in China. Int J Educ Res. (2019) 159:36–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2019.08.011

25. Lúcio J. International perspectives on older adult education: Research, policies and practice. Multidis J Educat Res. (2017) 7:121–3. doi: 10.17583/remie.2017.2517

26. Peng M, Yin N, Li MO. Sestrins function as guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitors for Rag GTPases to control mTORC1 signaling. Cell. (2014) 159:122–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.08.038

27. Van Hiel A, Van Assche J, De Cremer D, Onraet E, Bostyn D, Haesevoets T, et al. Can education change the world? Education amplifies differences in liberalization values and innovation between developed and developing countries. PLoS ONE. (2018) 13:e0199560. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0199560

28. Tang X. Analysis of collaborative innovation mechanism of cooperative education for the elderly under active aging. J Tianjin Radio TV Univ. (2020) 24:59–63.

29. Choi I, Cho SR. A case study of active aging through lifelong learning: psychosocial interpretation of older adult participation in evening schools in Korea. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:9232. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18179232

30. Liu L, Wu F, Tong H, Hao C, Xie T. The digital divide and active aging in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:12675. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182312675

31. Beason-Abmayr B, Caprette DR, Gopalan C. Flipped teaching eased the transition from face-to-face teaching to online instruction during the COVID-19 pandemic. Adv Physiol Educ. (2021) 45:384–9. doi: 10.1152/advan.00248.2020

32. Yilmaz Z, Gülbagci Dede H, Sears R. Yildiz Nielsen S. Are we all in this together?: mathematics teachers' perspectives on equity in remote instruction during pandemic. Educ Stud Math. (2021) 108:307–31. doi: 10.1007/s10649-021-10060-1

33. La Vera BL. International perspectives on older adult education: research, policies and practice. Multidis J Educat Res. (2017) 7:333–43. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-24939-1

34. Yu D. The Situation and Problems of Adult Education in China on the Perspective of Lifelong Education. Atlantis Press. (2014) 193–195. doi: 10.2991/icelaic-14.2014.49

35. Kee Y, Kim Y. “Republic of Korea”, In Findsen, B. Formosa, M. (Eds.), International Perspectives on Older Adult Education. Lifelong Learning Book Series, Cham: Springer (2016) 22. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-24939-1_31

36. Eronen J, Paakkari L, Portegijs E, Saajanaho M, Rantanen T. Health literacy supports active aging. Prev Med. (2021) 143:106330. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106330

37. Ganguli M, Hughes TF, Jia Y, Lingler J, Jacobsen E, Chang CH. Aging and functional health literacy: a population-based study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2021) 29:972–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.12.007

38. Liu YB, Liu L, Li YF, Chen YL. Relationship between Health Literacy, health-related behaviors and health status: a survey of elderly Chinese. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2015) 12:9714–25. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120809714

39. Tetzner J, Schuth M. Anxiety in late adulthood: associations with gender, education, and physical and cognitive functioning. Psychol Aging. (2016) 31:532–44. doi: 10.1037/pag0000108

40. Zhang Y, Su D, Chen Y, Tan M, Chen X. Effect of socioeconomic status on the physical and mental health of the elderly: the mediating effect of social participation. BMC Public Health. (2022) 22:605. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-13062-7

41. Lövdén M, Fratiglioni L, Glymour MM, Lindenberger U, Tucker-Drob EM. Education and cognitive functioning across the life span. Psychol Sci Public Interest. (2020) 21:6–41. doi: 10.1177/1529100620920576

42. Ding D, Zhao Q, Wu W, Xiao Z, Liang X, Luo J, et al. Prevalence and incidence of dementia in an older Chinese population over two decades: the role of education. Alzheimers Dement. (2020) 16:1650–62. doi: 10.1002/alz.12159

43. Xie H, Zhang C, Wang Y, Huang S, Cui W, Yang W, et al. Distinct patterns of cognitive aging modified by education level and gender among adults with limited or no formal education: a normative study of the mini-mental state examination. J Alzheimers Dis. (2016) 49:961–9. doi: 10.3233/JAD-143066

44. Fang EF, Xie C, Schenkel JA, Wu C, Long Q, Cui H, et al. A research agenda for ageing in China in the 21st century (2nd edition): focusing on basic and translational research, long-term care, policy and social networks. Ageing Res Rev. (2020) 64:101174. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2020.101174

45. Ponciano D, Chiacchio F, Rodrigues GA, Prado D, Arruda MA. Universities for seniority: a new perspective of aging. Asian J Educ Soc Stud. (2020): 10:50–4. doi: 10.9734/ajess/2020/v10i230267

46. Walker A, Maltby T. Active ageing: a strategic policy solution to demographic ageing in the European Union. Int J Soc Welfare. (2012) 21:S117–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2397.2012.00871.x

47. Rodriguez FS, Hofbauer LM, Röhr S. The role of education and income for cognitive functioning in old age: a cross-country comparison. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2021) 36:1908–21. doi: 10.1002/gps.5613

48. Luo Y, Zhang Z, Gu D. Education and mortality among older adults in China. Soc Sci Med. (2015) 127:134–42. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.09.039

49. Kawabori C. The aged: an opportunity for the educator. Health Educ. (1975) 6:6–7. doi: 10.1080/00970050.1975.10613575

50. Moulaert T, Biggs S. International and european policy on work and retirement: reinventing critical perspectives on active ageing and mature subjectivity. Human Relations. (2013) 66:23–43. doi: 10.1177/0018726711435180

51. Rhim HC, Han H. Teaching online: foundational concepts of online learning and practical guidelines. Korean J Med Educ. (2020) 32:175–83. doi: 10.3946/kjme.2020.171

52. Su G, Li J, Wu H, Li P, Xie X. Online and offline mixed teaching mode of medical genetics. Sheng Wu Gong Cheng Xue Bao. (2021) 37:2967–75. doi: 10.13345/j.cjb.200609

53. Fried LP. The need to invest in a public health system for older adults and longer lives, fit for the next pandemic. Front Public Health. (2021) 9:682949. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.682949

54. Evans AB, Nistrup A, Pfister G. Active ageing in Denmark; shifting institutional landscapes and the intersection of national and local priorities. J Aging Stud. (2018) 46:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2018.05.001

55. Ding D, Fu H, Bauman AE. Step it up: advancing physical activity research to promote healthy aging in China. J Sport Health Sci. (2016) 5:255–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jshs.2016.06.003

Keywords: active aging, education, older adult education, population aging, public health

Citation: Zhang K, Kan C, Luo Y, Song H, Tian Z, Ding W, Xu L, Han F and Hou N (2022) The promotion of active aging through older adult education in the context of population aging. Front. Public Health 10:998710. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.998710

Received: 20 July 2022; Accepted: 22 September 2022;

Published: 10 October 2022.

Edited by:

Qinghua Li, Guilin Medical University, ChinaReviewed by:

Yun Gao, Sichuan University, ChinaCopyright © 2022 Zhang, Kan, Luo, Song, Tian, Ding, Xu, Han and Hou. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Fang Han, ZnloYW5mYW5nQHdmbWMuZWR1LmNu; Ningning Hou, bmluZ25pbmcuaG91QHdmbWMuZWR1LmNu

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.